Aidan Moher's Blog, page 21

May 30, 2014

Best of ’13 — A Dribble of Ink in the Hugo Award Packet!

The 2014 Hugo Award Voter Packet is now available to all voters!

Nominated for two 2014 Hugo Awards, A Dribble of Ink was invited to contribute a collection of essays/reviews/posts to the Voter Packet that best represent its writing and contributions during 2013. So, I went wild and created a collection that will fill even the staunchest of traditional fanzine publishers with pride! It’s 66 pages of A Dribble of Ink goodness.

“But wait! I’m not a voter,” you might be thinking. Worry not. While voters will receive this collection in their packet, I want to make it available to everyone as a thanks for supporting A Dribble of Ink in 2013. After all, without all of you readers (and my wonderful contributors) there’d be no nomination!

Download Best of ’13 — A Dribble of Ink Collection [66 Pages, PDF]

A Dribble of Ink is nominated for two Hugo Awards: ‘Best Fanzine’ and ‘Best Related Work’ (for Kameron Hurley’s essay, ‘We Have Always Fought’).

Best Fanzine

Included in the collection is writing by:

Aidan Moher,

Kameron Hurley,

Justin Landon,

Foz Meadows, and

Max Gladstone

And, of course, headlining the collection is Kameron Hurley’s tremendous essay, ‘We Have Always Fought: Challenging the “Women, Cattle and Slaves’ Narrative”‘, which itself is nominated in the “Best Related Work” category.

Download Best of ’13 — A Dribble of Ink Collection [66 Pages, PDF]

Best Related Work

Art by Jason Chan

In addition to its general nomination, A Dribble of Ink is proud to have published Kameron Hurley’s Hugo-nominated essay, ‘We Have Always Fought: Challenging the “Women, Cattle and Slaves’ Narrative”‘. ‘We Have Always Fought’ is available in the Hugo Award Voter Packet as part of A Dribble of Ink’s collection in the ‘Best Fanzine’ category (available in the download link above).

Hugo Award Voter Packet

Hugo voters can download the 2014 Hugo Award Voter Packet on the official website. The Packet will be available until July 31st, 2014.

The post Best of ’13 — A Dribble of Ink in the Hugo Award Packet! appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 29, 2014

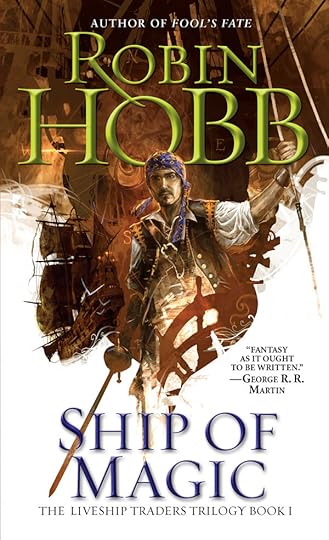

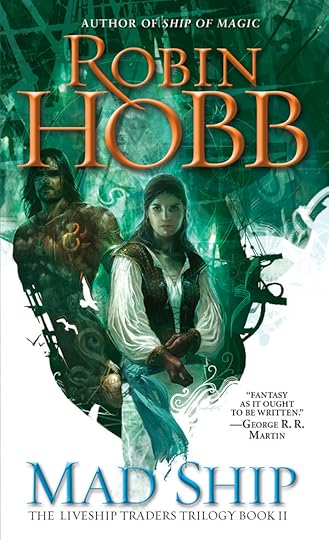

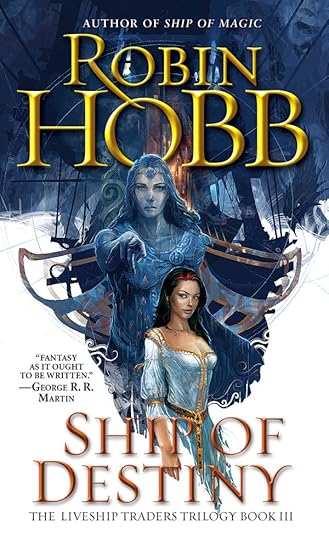

(Finally) New covers for Robin Hobb’s Liveship Traders trilogy

Robin Hobb has unveiled new covers for the Liveship Traders trilogy, with art from French artist Didier Graffet, and they’re mighty fine.

The previous North American covers for the Liveship Traders series were, umm… less than ideal (though perhaps ahead of their time for artist Stephen Youll’s illustration of a strong woman on the cover, without her boobs hanging out), and these are a big improvement. It’s too bad that that beveled text has become part of Hobb’s brand, though.

Graffet’s work might be familiar to Hobb fans for his work on the French graphic novel adaptation of the Farseer trilogy. “I was delighted when I first saw his images of the Farseers on the various covers [Graffet] did for the Soleil graphic novels of The Farseer Trilogy,” said Hobb. “So I am delighted to now have his work on the US paperback covers.”

The post (Finally) New covers for Robin Hobb’s Liveship Traders trilogy appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 28, 2014

Tor.com announces major changes, new short fiction imprint

Today, Tor.com announced the launch of a new imprint, called, appropriately, The Imprint, dedicated to publishing “novellas, shorter novels, serializations, and any other pieces of fiction that exceed the traditional novelette length (17,499 words).” This is in addition to their award-winning library of short stories, and aims to further identify Tor.com as one of the leading short fiction (and, now, mid-range fiction) venues in SFF publishing. This is exciting and encouraging for a lot of reasons. First and foremost, more short fiction from a pro-paying market. Second, a glimpse at what the future of “traditional” publishing might hold.

Fritz Foy and Irene Gallo, will continue in their positions of Publisher and Associate Publisher of Tor.com, while Carl Engle-Laird is moving into the role of editorial assistant. Tor.com is also in the hunt for a senior editor, publicity manager, marketing manager, and designer. (Worry not, faithful readers! I’m starting my campaign trail right now.)

Tom Doherty, President and Publisher of Tom Doherty Associates LLC, said, “The Tor.com imprint will allow authors to cater to ebook and mobile readers by releasing a short form that in turn promotes awareness of that author’s books on the shelf. Release windows for ebook novellas are more flexible, and the length of the story strengthens the options that authors both new and experienced have in getting their fiction to the market.”

The official blog post has early details about delivery of these new publications, which will be mostly digital:

Each DRM-free title will be available exclusively for purchase, unlike the current fiction that is offered for free on the site, and will have full publisher support behind it. It will have a heavy digital focus but all titles will be available via POD and audio formats. We will also consider traditional print publishing for a select number of titles a year. All titles will be available worldwide.

The Tor.com imprint was ostensibly created to create a new professional market for short stories that are caught in limbo between the short fiction and novel markets, which is a noble cause, but there’s certainly more to the imprint than creating a professional market for novellas. It’s also a test bed for Tor.com, and their mothership, Macmillan, to explore the brave new publishing world that is forming around the industry. As self-publishing is becoming a powerhouse, even the traditional publishers, like Tor Books/Macmillan, have to consider their own avenues for getting out from under the thumb of their gatekeepers: Amazon.com.

Art by Greg Manchess

We are looking forward to creating a program with a fresh, start-up mentality, but with the rich legacy of Tor Books and Tor.com behind us.

Where self-publishing generally sees authors taking authority and control over their property away from the traditional publishers, self-publishing, in this sense, is about the traditional publishers reacquiring control over their assets and business from Amazon.com, in the wake of the latest controversy. The mega-retailer, who has recently create their own publishing imprints that directly compete with publishers like Macmillan, is putting uncomfortable pressure on publishers to bend to the will of their heavy demands, which cost publishers and authors money, and, in the long-term, cost readers access to books that don’t go through the Amazon system.

“We have worked hard to ensure that our contracts are as streamlined and author-friendly as possible, and will only include rights that can be immediately utilized by the authors,” said the Tor.com editorial staff in the official post about the new imprint. “Authors will be offered the option of receiving a traditional advance against net earnings or higher rates with no advance. Royalties for all formats will be based on net publisher receipts with no hidden deductions and will be paid quarterly.”

Tor.com has been at the forefront of publishing author- and reader-friendly short fiction. Most notably with the launch of their DRM-free eBook store in 2012. Tor also pays above average rates ($0.25/per word, rather than $0.05/word) for short fiction. By launching this new imprint, Tor.com will have an opportunity to freely introduce their customers to new authors, new delivery and pricing methods, and experiment with the many opportunities that have opened up to publishers in the past several years.

“In short,” said the Tor.com editorial staff, “we are using this opportunity to reevaluate every step of the publishing process and are looking forward to creating a program with a fresh, start-up mentality, but with the rich legacy of Tor Books and Tor.com behind us.”

The post Tor.com announces major changes, new short fiction imprint appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 27, 2014

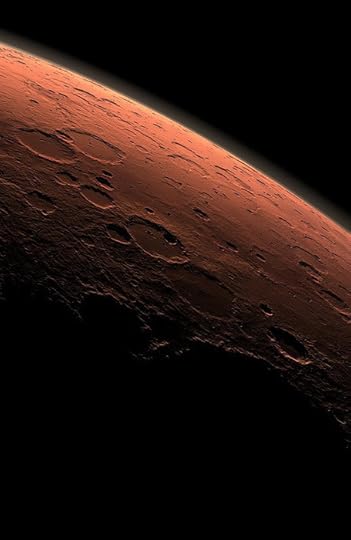

On Mars, no one can hear you break down hydrazine into its component properties

I have a confession to make.

I read Andy Weir’s The Martian because of the cover. It’s shiny and dramatic, features an astronaut, and, well… it’s really shiny.

Earlier this year, I read An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, the autobiography of Chris Hadfield, a Canadian astronaut and former commander of the International Space Station, and Packing for Mars by Mary Roach, a non-fiction examination of what it takes to survive in space. So, after two non-fiction books, The Martian seemed like the perfect cap-off to my mini-tour of our solar system.

The difference between the three books is obvious from the get-go, most notably the backgrounds and first-hand experiences of the three authors. Hadfield’s book draws on his own personal knowledge of being an astronaut, including a harrowing tale of a time when he was literally blinded while doing a spacewalk. Roach’s book is a well-researched examination of the amusing and relatable aspects of human life in space. Weir, on the other hand, is an admitted hobbyist, and his novel combines Roach’s obsessive level of research with the a mile-a-minute plotting of Michael Crichton’s best science thrillers.

“I’m the sort of geek who will stay up all night to watch the news and see a Mars probe land,” Weir told Shawn Speakman, in an interview with Suvudu. “So I started out with a pretty heavy hobbyist knowledge of the material. Then, while writing the book I did tons of research. I wanted the science to be as accurate as I could possibly make it.”

Through careful application of existing sciences, Weir manages to maintain a level of believability equal to the breakneck pace of the narrative.

Weir’s intense dedication to research and realism paid dividends. Beginning life as a self-published serial on Watney’s website, The Martian makes so many bold moves that it required razor sharp precision as it navigated the hostile situation that its narrator, Mark Watney, faces on nearly every page. Many of the books most intense moments, and hair-raising escapes, are built on the back of exact scientific methods. If suspension of belief is broken for even just a moment, the illusion is gone and you’re left with nothing more than a bad Jerry Bruckheimer movie. Through careful application of existing sciences (and more than one instance where luck proves more powerful than preparation), Weir manages to maintain a level of believability equal to the breakneck pace of the narrative.

From the first page to the last, The Martian whips the reader along with all the [insert velocity-related pun here] and demands to be read late into the night.

“Just one more log,” The Martian whispers. “What’s sort of trouble is Watney going to face when you turn the page?”

Like any thriller, The Martian relies on providing increasingly poor odds of survival. Like any good thriller, The Martian navigates Watney out of these situations by the skin of his teeth, and through believable means. Every page is filled with either the promise of Watney’s demise, or a clever solution to a situation that seemed hopeless.

Some of the tension is softened by The Martian‘s narrative structure: Watney’s hand-typed mission logs. These logs, written by Watney as he records his attempt at survival in the hopes that a future Mars mission might recover them/him, run the gamut from short vignettes, to full-blown scientific explanations of what it takes to grow potatoes in Martian soil, to Watney’s first thoughts as he watched his crew mates blast into orbit.

LOG ENTRY: SOL 6

I’m pretty much fucked.

That’s my considered opinion.

Fucked.

Six days into what should be the greatest two months of my life, and it’s turned into a nightmare.

I don’t even know who’ll read this. I guess someone will find it eventually. Maybe a hundred years from now.

For the record . . . I didn’t die on Sol 6. Certainly the rest of the crew thought I did, and I can’t blame them. Maybe there’ll be a day of national mourning for me, and my Wikipedia page will say, “Mark Watney is the only human being to have died on Mars.”

And it’ll be right, probably. ‘Cause I’ll surely die here. Just not on Sol 6 when everyone thinks I did.

Let’s see . . . where do I begin?

p. 1

Art by Brad Wright

One issue with this approach is that the logs have difficulty establishing an emotional connection with the reader. They’re interesting and engaging to read, but, by their very nature, the logs are recorded history, rather than a personal dialogue between the reader and the storyteller. As a result, the novel lacks the intense emotional bond that readers often form with first-person narrators. This may or may not be an issue for all readers, after all, many readers will be looking for the equivalent of a summer blockbuster, and The Martian delivers there, but there is some narrative distance between Watney and the reader that might impact the their ability to really sink into The Martian‘s desperate conflict.

The novel only breaks away from these logs when it’s necessary to visit those helping Watney from Earth, or to give the reader a more omniscient perspective on events that transfer poorly (i.e. lack drama and suspense) when written after-the-fact by the (obviously still living) narrator. These off-Mars scenes are the root of one of the novel’s major flaws, which I’ll discuss later, but are essential for proper framing of the narrative and become increasingly important as the novel progresses.

One of the key factors for life in space, touched on by both Hadfield and Roach, is the mental taxation that threatens astronauts through every stage of their journey. Space is incredibly hostile to human life, and every second spent there is a fight to stay alive. The Martian admits to this, and spends most of its time communicating to readers how Watney fights that fight, however, there’s little engagement with the mental hurdles that Watney must overcome as he struggles with his isolation from the rest of humanity.

Actually, I was the very lowest ranked member of the crew. I would only be ‘in command’ if I were the only remaining person.

What do you know? I’m in command

Mark Watney, The Martian

Make no mistake, this isn’t Heart of Darkness. There’s no descent into madness. Hell, it’s not even Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity, which at least dealt with its protagonist’s emotional reaction to being stranded alone in space. The Martian is more like the technical manual that a hobbyist scientist handed to Cuaron after a pass through the first draft of the film script.

I was going for realism above all else, so I ditched the idea of it being purely a one-man story and went another direction.

Gravity eschews most of its science for unbelievable-but-thrilling cinematics and drama, which Neil DeGrasse Tyson famously dissected, whereas Weir is more measured in his approach to survival in space.

“Originally I wanted the story to be just Mark on Mars the whole way through,” Weir told a Reddit user in a recent AMA. “But as it developed it became increasingly clear that NASA would notice he was alive. I was going for realism above all else, so I ditched the idea of it being purely a one-man story and went another direction.”

“I can’t wait till I have grandchildren. When I was younger, I had to walk to the rim of a crater. Uphill! In an EVA suit! On Mars, ya little shit! Ya hear me? Mars!”

It’s difficult not to compare The Martian to Cuaron’s Oscar-winning film. The broad strokes of their plots are almost identical: near-future, lone astronaut is stranded in space. The major point of divergence, however, is the level of ability, preparedness, and resources available to the two protagonists, The Martian‘s Mark Watney, and Gravity‘s Ryan Stone, buoyed by Weir’s obsession with scientific nuance. It’s made clear early on in Gravity that Stone is a medical-engineer-turned-rookie-astronaut with only six months of training before her trip into Earth’s orbit, which seems absurd if you think about it for more than the three seconds that the film gives you to digest the idea. Watney, on the other hand, has years of training and hundreds of EVA (Extra-vehicular activity) hours under his belt. Where Stone’s return to Earth is nothing short of miraculous, Watney’s tale is more methodical and, as a reward for Weir’s careful planning, more believable (on the scale of Optimus Prime riding a mechanical dinosaur -> Bruce Willis drilling an atomic bomb into an asteroid).

Photograph by NASA

“Gravity is made from start to finish as a visual experience, and they have some unbelievably beautiful scenes,” Weir told Suvudu, comparing the blockbuster film to his novel. “It has hard sci-fi elements, but there are also a lot of things glossed over to make a more exciting movie. There’s nothing wrong with that, but I think The Martian is much more focused on the realistic science and has a lot more problems for its hapless hero.”

Ultimately, the novel’s success with a reader will hinge on their ability to sink into and enjoy the sometimes pedantic science that Watney uses over his tenure on Mars. It’s generally interesting in a MacGuyver-kinda way, but also requires less knowledgable readers to approach the science as they would magic in a fantasy novel: just believe Watney when he says it works.

Art by Brad Wright

Weir does a fine job of conveying the novel’s science, much of which involves complex chemistry, to the reader in a way that makes them believe they understand the process that Watney is using to survive. Could I sustain a martian potato garden using water, martian soil, and human shit? No, but I believed that Watney’s science held up, thanks in part to Chris Hadfield’s blurb of the book, which he credits for its “fascinating technical accuracy.”

Watney’s likeable and clever, as often pointed out by other characters in the novel, the kinda guy that you’d like to have in your back pocket if you’re ever in a sticky situation, and his sense of humour is relentless and sharp. Since so much of the novel’s narrative is told in his voice, this gives The Martian a sense of levity that other authors might miss. Being stranded on Mars is tough shit, and that could potentially lead to a novel that becomes tiresome and difficult to enjoy with the wrong protagonist. Weir avoids this by casting the world’s most saccharine astronaut. It’s all partly to blame for the novel’s lack of engagement with the psychological effects of isolation, but ultimately ensures that it’s enjoyable to spend 300+ pages at his side. You want him to get off of Mars because, well… you like him.

One irritant that stems from both the novels’ scientific methodology and Watney’s personality is that things seem to come too easily for the botanist-cum-astronaut. Like Indiana Jones, Watney always seems to be on the good side of luck when things seem at their worst. Sure, he gets himself into sticky situations on nearly every page, but luck and unerring ingenuity always seem to get him through the day. When disaster waits of the starboard side, the wind nudges Watney to port. The novel’s mission log-style structure also creates a repetitive sense of Trouble appears/fade-to-black/lights-fade in/Watney explains why he’s so clever and how he’ll solve everything/fade-to-black/Oh, hey! Everything’s fine again.

Samantha Nelson of The A.V. Club explains away Watney’s clever perfection in her review, “The Martian manages to have a good excuse for having a hero who can solve almost every problem while still being hilarious: NASA had the luxury of only sending geniuses that can stay in good spirits while floating in space for months.” While this explanation isn’t likely to hold up against IRL astronauts and space missions, it’s just good enough to allow readers to accept that without Watney’s superhuman personality and evil genius-level intelligence, it’d just be a story about an astronaut’s short and tragic attempt to survive on Mars. Not much of a novel, right?

Buy The Martian by Andy Weir: Book/eBook

The Martian is bleak and intense, humorous, human, and hard to put down.

Unfortunately, the rest of the characters that surround Watney (metaphorically, he’s hundreds of thousands of kilometers away from most of them) are static and boring. The crew of the Hermes (who abandoned Watney) go about 20% of the way to being a Firefly-esque ensemble of interesting people, and the folks at NASA Mission Control are all cardboard cutouts with different titles slapped on them. They get the job done, and provide a framing narrative that helps to provide better context to Watney’s situation, but don’t expect to remember their names after closing the final page.

The Martian is bleak and intense, humorous, human, and hard to put down. I picked it up because I couldn’t resist the cover, and was lucky to find that the pages behind the cover lived up to my expectations. Where a summer blockbuster keeps you on the edge of your seat, and hides its mistakes by pumping adrenaline, The Martian leaves you white knuckled because you have time to think about why the hero’s probably not going to make it. But, The Martian will leave you with a smile on your face as Watney, through the wish fulfillment of his clever creator/author, somehow manages to avoid a grisly fate over-and-over again, just like a true action her. Like Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity, Andy Weir’s The Martian is an edge-of-your-seat thriller that’s over before its flaws can bring it down.

The post On Mars, no one can hear you break down hydrazine into its component properties appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 26, 2014

Review of Child of Light, published by Ubisoft

Publisher: Ubisoft - Genre: RPG - System: Multi-platform

Buy: PC Download

tl;dr (spoiler free)

Child of Light, a side-scrolling JPRG developed by Ubisoft, features gorgeous 2D visuals (complete with great use of parallax scrolling of multiple layers), a beautiful and very non-traditional musical score, and fun strategic combat heavily inspired by the Grandia series. I didn’t like the story or the writing, but I enjoyed the game otherwise.

Full Review

Child of Light uses a modified Grandia combat system. For those unfamiliar with the system (and who haven’t played our own Penny Arcade RPGs which use a similar system), the core is that by hitting enemies right before they make their next move, you interrupt them which knocks them back on the time bar, essentially stunning them briefly. Child of Light makes a few changes to the basic Grandia system: your party consists of only two characters at a time (Grandia had a four person party); you can swap characters in and out mid-battle with ease; there is no positioning aspect (in Grandia, allies and enemies moved around the battlefield and different attacks had different ranges and areas of effect); all attacks can interrupt enemies (in Grandia, only specifically marked interrupt abilities did this); and you have a firefly friend, Igniculus, who can slow down enemies.

Child of Light does a good job at simplifying many JRPG mechanics, but falters in others, notably, the level up system.

Igniculus solves a key problem from the Grandia system. Grandia‘s battle system is primarily a reactive one – you wait for your turn, see where everyone is on the time bar, and then decide if the current situation lets you interrupt enemies. Igniculus solves this by giving the player a finer level of control over the enemies’ position on the time bar, thus allowing the player to actively set up interrupt situations, instead of just take advantage of situations as they arise. An astute gamer will quickly recognize that it’s not always ideal to slow down your enemies, sometimes you want them moving at full speed.

Child of Light does a good job at simplifying many JRPG mechanics – low active party size, each character has a clear niche, streamlined equipment system – but falters in others, notably, the level up system. On the one hand, it’s relatively simple – get a skill point each time a character levels up, then use that skill point to progress down one of three paths for each character – but at the same time, it could have been even simpler. Once you’ve progressed through the early levels, levelling up no longer rewards players with new abilities, but only minor stat bonuses and upgrades to existing abilities. Unfortunately, this creates a halt in character progression.

You can adjust characters somewhat based on which path you focus on (Rubella, a jester that Aurora meets early in her adventure, can be a great physical warrior with decent healing abilities, or a decent physical warrior with great healing abilities), but in general, the levelling system just isn’t very exciting. For some characters, one path seems clearly superior (like with the mage, getting +30% to all spell damage is a lot more useful than boosting his crummy physical attack capabilities). Child of Light would have benefitted from going to more of an extreme: simplify things further by making levelling up a strictly linear experience (set stat bonuses and abilities at set levels), or increasing the number of interesting choices in developing individual characters.

Art by: Yoshitaka Amano | Lunacy | Calette

Each character in Child of Light has their own unique attack command. The power and speed of each attack equivalent varies from character-to-character, and several characters even have secondary characteristics attached to their attack. Besides adding an extra level of strategy to simple attacks, these variations helped to add personality to each character. Unfortunately, they missed a chance to do something similar with the defend command. It would have been easy to create various defend variants of the defend command, for example: defend with an increased chance to dodge; defend that doesn’t reduce damage as much as normal but has a higher speed bonus; or, defending that also protects allies.

Speaking of defending, Child of Light is one of the few RPGs where the defend command is very useful. There are three reasons for this: 1) the aforementioned Interrupt system; 2) frequent use of “Charge Up” abilities from a number of enemies; 3) a more powerful defend action than in similar games. Whereas a typical JRPG defend command merely cuts damage in half, Child of Light‘s defend command, at max rank, cuts damage to by 80% and provide the character with a speed bonus on the following turn.

It’s much easier to just develop a general purpose strategy for winning in combat, rather than adjusting your strategy on a fight-by-fight basis.

Ailments and debuffs are highly effective in Child of Light since no enemies are immune, but buffs are a lot weaker than they are in most RPGs due to the small party size (group buffs only affect 2 people), and the frequent rotation of characters into-and-out-of combat. The solution to this might have been as easy as allowing buffs to target your entire party, regardless of who was in combat when it’s cast.

Combat in general lacks transparency. Specifically, there’s no way to gain information on enemies – their max/current HP, strengths, weaknesses, attack patterns – short of trial and error. Because of this, it’s much easier to just develop a general purpose strategy for winning in combat, rather than adjusting your strategy on a fight-by-fight basis.

Later in the game, Child of Light has frequent encounters with enemies that are highly resistant to either physical or magical attacks, forcing the player to use the appropriate attacks against them. This is reinforced even further by often giving these enemies counter-attacks if you use the “wrong” attack type against them. Rather than feel clever for using the right attack against them, the frequent use of this sort of brute force approach to balancing makes the player feel like they’re just being led by the hand through the developer’s ‘puzzle,’ rather than being able to devise their own strategy for victory. And since there are only two characters in the game with decent magic capabilities, this design felt more restrictive than necessary.

Although I didn’t personally mind, I could see how some people could find the constant combat in Child of Light tiresome. There is some attempt to counter this with the occasional conversation between party members, the lack of non-combat situations is noticeable. I would have liked to have seen larger and/or more frequent towns, more puzzles, and platforming challenges.

Art by Shira

Characters in Child of Light can be equipped with oculi: small gemstones than can be combined in various ways to increase or change their effect. There’s elegance in the way that each oculi have a different effect depending on where they are equipped, and using them as the foundation of the crafting system, but the user interface is cumbersome and more complicated than necessary. I missed the ability to see all effects on a single screen (and when crafting), and being able to see how many total oculi were in my inventory and equipped to my characters. These two small changes would have made crafting a much smoother experience.

Despite some questionable design choices, I greatly enjoyed Child of Light

I’m choosing not to examine the story and writing too deeply, partly because I’m no expert on poetry, but I felt like the writing was presented, using four line poetic stanzas for all dialogue, in a fashion that made the game sometimes difficult to understand. Specifically, sticking multiple characters in a single dialogue box made it hard at times to remember who was talking, and displaying the dialogue one line at a time made it more difficult to figure out the appropriate rhythm to use (unlike say, a children’s book where you can easily see an entire exchange at a glance).

And there you have it. Despite some questionable design choices, I greatly enjoyed Child of Light (and in fact, it’s the first RPG that I’ve played all the way through this year), but there’s definite room for improvement if Ubisoft revisits the world of Lemuria.

This review was published in its original form on Zeboyd.com

Second Opinion

by Aidan Moher, editor

Robert’s review focused on Child of Light‘s mechanics, so I wanted to take a moment to discuss its story, an integral part of the experience, and also an aspect that is likely to make or break the experience for many players.

Child of Light features beautiful watercolour aesthetics, and tremendous art direction, which brings to life the fairy tale world of Lemuria. Built on the same graphics engine that powered the recent Rayman games, Child of Light is gorgeous from beginning to end, with rich and diverse environments that draw players through each area, excited about seeing what’s around the next corner. Child of Light is said to pay homage to the work of Hayao Miyazaki and Yoskitaka Amano, and though it diverges from those artists stylistically, the same amount love and polish that made those artists famous is found in every inch of Lemuria’s lush watercolour design.

Equal to Lemuria are the characters that populate it. Aurora herself is charming and self-determined, and it’s easy to spend the dozen-or-so hours it takes to complete Child of Light at her side. Also charming are the other characters that she meets on her journey, all of whom have their own motives and personalities. For a short RPG, Child of Light is full of memorable personalities.

Unfortunately, as Robert alluded to above, all of this is marred by Ubisoft’s decision to write all of the game’s dialogue in rhyming verse. There’s nothing wrong with decision on a base level — in fact, it fits the game’s fairy tale narrative — but Ubisoft writer Jeffrey Yohalem neglected to pair the rhyming with any sort of consistent logic or metering. An example line of dialogue from midway through the game:

“How can this be? Tucked in your bed,

Cheeks of ash, still as lead. I saw you…

It is a miracle!

Mother and her duke tears of joy will be shed.”

The result is dialogue that appears quaint at first glance, but quickly becomes cumbersome and frustrating as the player begins to wade through opaque conversations that sacrifice clarity for word choice. It’s a shame, because it’s clear that Yohalem put a tremendous amount of time and effort into the dialogue, but it was, perhaps, a risk better left alone.

Child of Light tells a good story, full of motivated characters and a wonderfully drawn world, but, there are unfortunate flaws that hold the game back from reaching its full potential.

The post Review of Child of Light, published by Ubisoft appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 23, 2014

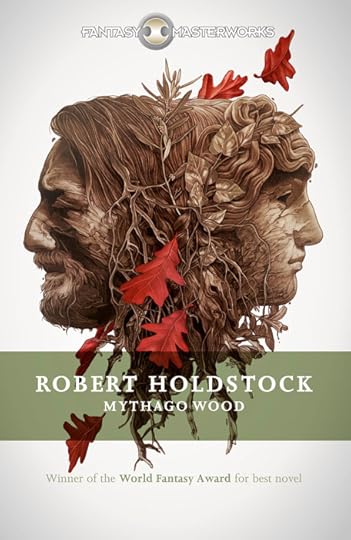

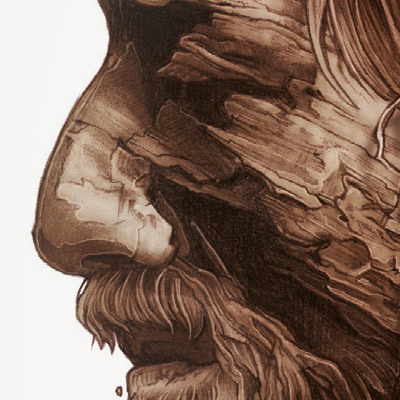

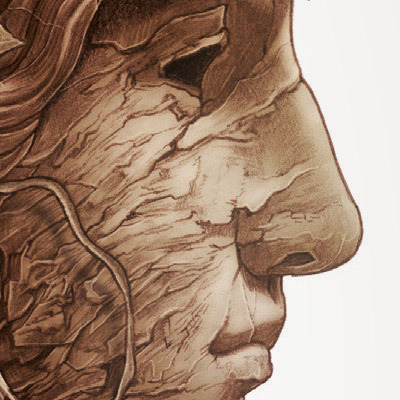

A classic cover for a classic novel: Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock

I’m still all salty from posting that Erikson cover on Monday, so, to make up for it, here’s the gorgeous cover for Gollancz’s Fantasy Masterworks 30th Anniversary edition of Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock.

“I think it treats the book as the modern classic it undoubtedly is, as well as reflecting the earthy vibrancy and primordial energy of the book.” said Darren Nash of Gollancz.

I think [Robert Holdstock] would have loved it.”

Robert Holdstock is considered one of modern fantasy’s most revered writers. He passed away in 2009 at the age of 61.

“The cover design is by Graeme Langhorne, who produced the beautiful series style for the re-launched Fantasy Masterworks, and the amazing artwork is by Grzegorz Domaradzki, who is responsible for many other lovely covers in the series.”

More of Grzegorz Domaradzki’s artwork can be found on his official website.

The post A classic cover for a classic novel: Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 22, 2014

What if Disney adapted Game of Thrones?

Brazilian artists Anderson Mahanski and Fernando Mendonça asked just that. In answer, the talented illustrators created a set of portraits imagining how six of Game of Thrones‘ most iconic characters — Jon Snow, Cersei Lannister, Tyrion Lannister, Bran Stark, Hodor Hodor, and Daenerys Targaryen — would appear in a more family-friendly (though no less inebriated, apparently) fashion.

The results are delightful.

Click thumbnails to embiggen

More art from Mahanski and Mendonça, including some stunning line-drawn portraits, can be found by visiting their DeviantArt profiles: Mendonça/Mahanski. Beware, salaciousness awaits.

The post What if Disney adapted Game of Thrones? appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 20, 2014

Your milage may vary on this Otherbound adventure

Every time Nolan Santiago closes his eyes in Arizona, he opens them in another world. There, he sees through the eyes of Amara, a mute servant tasked with protecting Cilla, a renegade princess threatened by a terrible curse. Though Amara doesn’t know it, Nolan has been bound to her his whole life, a silent passenger who nonetheless sees her thoughts and feels her pain as though they were his own. Nolan’s family think he has epilepsy, seizures and hallucinations, but no matter how many pills he takes, Amara remains real. Until, suddenly, a new medication gives Nolan the power to take over Amara’s body. For the first time, he can communicate with the Dunelands – and with Amara. But Amara has enough problems without learning about Nolan: her life is a misery of torture and servitude, she doesn’t know how to feel about Cilla, and the assassins chasing them are closing in. How can Nolan help with that? And why does Amara’s master, Jorn, seem suddenly to be in league with Cilla’s enemies?

This is going to be a review in three parts: a spoiler-free overview, some spoilery analysis, and a spoiler-free conclusion – because, as you may have guessed, Otherbound is a tricky book to discuss without giving away the ending. Or so I found it to be, though others may not – it’s very much a Your Mileage May Vary issue.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s start with the basics, shall we?

Otherbound is a tense, well-written debut with a lot to recommend it. Duyvis manages the transitions between Nolan’s POV and Amara’s with skill and care, which makes for a quick read – but not, crucially, a simple one. In very different ways, Amara and Nolan are both trapped in realities not of their choosing: Nolan literally so, as his ties to Amara make it impossible for him to live a normal life, and Amara by the horrific strictures of her life as a servant. Not only was her tongue cut out as a child, so that most of her speech is in sign language, but she is regularly subject to extreme violence on account of her healing magic. Years ago, Cilla – the princess Amara serves – was cursed by her enemies, so that every time her blood touches the air, the surrounding environment rises up to crush and kill her. Whenever this happens, Amara’s job is to thwart and confuse the curse by smearing Cilla’s blood on her skin and taking the punishment – which would otherwise prove fatal – in her place. Worse still, her master, Jorn, sometimes vents his frustrations by beating or torturing Amara: he knows she’ll heal, and so has no problem with with cutting, burning or drowning her.

Art by Kalen Chock

Duyvis writes so smoothly, and the pacing is so strong, that once I picked up the book, I was readily immersed in the world

And heal Amara does, though the psychological cost remains. But Nolan, who feels her pain in tandem, lacks that gift. Years ago, Amara’s pain caused him to fall in the road, where his leg was crushed by a passing truck. Now, he uses a prosthesis, which further restricts his mobility (the fact that every blink puts him in another world is a handicap in and of itself). Nolan is also forced to lie about his “hallucinations”, which further puts him at a distance from his family. His only reprieve from Amara’s world, the Dunelands, comes when Amara herself is asleep – and as she rarely sleeps when Nolan does, he doesn’t even dream his own dreams anymore.

All these issues are explored well, not only in terms of Nolan and Amara’s personalities, but the wider implications it has on their dealings in both worlds, and what it means when the two of them are finally able to communicate. But the tight focus on their suffering, and the extent to which it permeates the rest of the story, also makes the narrative feel close, almost claustrophobic. That’s not necessarily a bad thing: it very much depends on the reader, and whether you’re looking for light-hearted escapism or something more complicated. For me, it had a riptide effect: Duyvis writes so smoothly, and the pacing is so strong, that once I picked up the book, I was readily immersed in the world – but I also found it tiring, and had to take recuperative breaks between sessions.

Art by Benjamin Ee

The Dunelands, and the various cultures inhabiting it, are all made to feel real and distinct.

On an unequivocally positive note, Otherbound is a pleasure to read in terms of seeing diversity done well. Nolan, Amara and Cilla are all people of colour – as, indeed, are the majority of the inhabitants of the Dunelands – while the complexities of Amara and Cilla’s relationship are all rightly attributed to the power differentials between them, and not to the fact that they’re both women. Though we spend comparatively little time in Nolan’s world, his cultural heritage and disabilities are treated with depth and respect, as are his family ties – qualities that are important, not only for their own sake, but because they provide a much-needed context for Nolan’s actions, both in terms of what he’s been missing, and on what he’s ultimately battling to reclaim. Similarly, Amara’s reliance on servant-signs, her struggles to learn to read, and the enforced habit of obedience are also addressed well. The Dunelands, and the various cultures inhabiting it, are all made to feel real and distinct, and it’s always refreshing to read a secondary world fantasy inspired by more than just the usual faux-medieval mishmash.

Overwhelmingly, then, Otherbound is a strong debut, and one I’d definitely recommend. However, there were two aspects of the book that marred my enjoyment of it, and as tricky as they are to discuss without entering into spoiler territory, I don’t feel I’d be doing my job as a reviewer if I didn’t address them.

The first and most important of these is the magic itself: it underpins absolutely everything in the book, but I never felt like I understood how or why it worked – and that proved jarring on multiple counts. The problem is twofold: firstly, that the magic itself is often explained in a way that feels confusing or contradictory; and secondly, that this is only sometimes attributable to the ignorance of the characters. All the way through the book, I had questions about the magic: why could Amara repeatedly heal her entire body, but not regrow the tongue she’d lost before her magic manifested? It’s revealed (slight spoiler) that Amara can only heal because of Nolan’s presence, but we’re never told why this is – nor, for that matter, why Nolan can heal Amara but not himself, why a magic that allows him to share someone’s thoughts would naturally have a healing component in the first place, or why a new medication should suddenly impact on his ability to use what we’re told is an innate magical ability. I didn’t understand how the spell that was originally meant to kill Cilla had instead transformed into a curse, or why, when we’re repeatedly told that magical backlash is the inevitable result of two types of magic interacting, it was possible for Amara to be “attacked” by Cilla’s curse without this interfering with her own/Nolan’s magic.

Art by Maciej Kuciara

Some of this may well be the result of a failure of comprehension on my part, as well as a YMMV issue: for whatever reason, I tend to be deeply sceptical of the magical curses as narrative device, which in turn made me ask fundamental questions of Otherbound earlier than was perhaps the author’s intention. It never made sense to me that Cilla’s enemies would curse, rather than kill her – and, indeed, we eventually learn that the curse was the unintentional consequence of a botched murder attempt. But because it takes so long for Amara to question this, the fact of the curse ends up feeling less like part of a deeper, more subtle mystery to be pieced together – which it is – and more like a piece of dissonant plotting. Nor was this the only instance in which I spent most of the book thinking a particular magical law made no sense, or that a certain action was implausible, only to have to have it eventually revealed – and the finale did answer many such overhanging questions – that it was really a lie, or a half-truth, or explicable only in light of new information.

Had every such early question been so neatly resolved at the end, my feelings would be quite different: I’d likely still have felt frustrated at the time, but less comprehensively so, and the payoff would have made up for it. But instead, despite everything that’s explained, there’s still much about the magic that never makes sense (like Nolan healing Amara), or which continues to feel contradictory (like the explanations about backlash and mixing magic). Some answers beg further, unaddressed questions, which is irksome in a different way. In a novel where so much else felt careful and well-constructed, and despite the impact of the finale’s explanations – which were both clever and satisfying – overall, the magic felt anomalous: as though it were just an external conceit retrofitted to the story, rather than a fundamental part of the worldbuilding whose rules were capable of dictating events. That might seem like a pedantic distinction to make, and for some readers, it doubtless won’t matter; but for me, it did. I prefer to question a story because the characters are, because narrative cues suggest they might be unreliable narrators, or because there’s a clear mystery to be solved; not because I’m uncertain whether the story itself, or aspects of it, actually make sense.

Despite its flaws, Otherbound boasts an original premise, strong writing and a gripping pace, [and] the end result is a strong debut [that] I’d sincerely recommend.

The other problem I had was with Cilla’s character. Similar to my reaction to her curse, from early on, it never made sense to me that Cilla, despite all their apparent differences in rank, would be so comprehensively different to Amara in terms of her confidence, education and manners. We’re told that both girls were taken from the palace as very young children – Cilla was only a toddler – and have been on the run with Jorn ever since, living in close quarters, associating almost exclusively with each other, frequently changing locations, and being constantly under threat. So how would Cilla have knowledge – like being being able to read – that Amara didn’t? If Jorn were going to teach her, he’d presumably have to do so in Amara’s presence; and even if Amara were learning only by proximity, it still seemed strange that she’d know so much less than Cilla. It felt equally odd that the two girls seemed to lack solidarity when it came to Jorn’s mistreatment of Amara, especially when their knowledge of sign language meant they could easily communicate in silence. Cultural conditioning, and a specific childhood incident cited by Amara to explain why she kept her emotional distance from Cilla, only explains so much: it felt much more like they’d been raised separately, in very different circumstances, then thrown together as teenagers, rather than that they’d known each other all their lives, and been raised on the run.

Buy Otherbound by Corinne Duyvis: Book/eBook

But the novel’s ultimate revelation – which makes this entire paragraph a massive, major spoiler alert – is that Cilla was never a princess to begin with. Rather than the ruling powers wanting her dead, they’re actually trying to keep her safe from their enemies: the spell they’ve cast on her is the key to their control of the Dunelands, and if she dies, they lose everything. And while this makes for a neat plot twist, narratively speaking, it also undermines Cilla further: the idea that she’d consistently received special protection and treatment from Jorn already felt thin and strange, especially given the circumstances of their lives and his treatment of Amara, but with this revelation, even the pretext for that belief comes crashing down. If Cilla being the lost heir to the throne is all a ruse, it seems a needlessly elaborate one, and something that surely wouldn’t translate to actually raising her as royalty, or treating her well – why bother, when that would only make it harder to control her in adulthood? It’s a neat trick that explains some early inconsistencies, but as with the magic, it does so at the expense of introducing more problems than it solves.

Ultimately, however, Otherbound concludes in a highly satisfying way. Though I still had questions about the magic and Cilla, and though I felt that Nolan’s ending was a little rushed – his catharsis seems a bit simplified, given all the new questions both he and the reader are left with – the book itself is still one I’d cheerfully recommend. Despite its flaws, Otherbound boasts an original premise, strong writing and a gripping pace, and when you combine all that with a thoughtful, sincere and well-researched approach to diversity, the end result is a strong debut, and a book I’d sincerely recommend. I’m eager to see what Duyvis writes next, and hope that Otherbound marks the start of a long and successful authorial career.

The post Your milage may vary on this Otherbound adventure appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 19, 2014

Cover Art for Willful Child by Steven Erikson (#WTF)

No. No. Just… no.

What is he going to do to me with that gun? No. Oh god. no.

The post Cover Art for Willful Child by Steven Erikson (#WTF) appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

May 14, 2014

The Super Giant Artwork of Jen Zee

Artist Jen Zee is best known for her role as Art Director at Super Giant Games, where she’s “responsible for the lush hand-painted 2D artwork that defines the distinctive look of our gameworld and all its colorful denizens.” She helped to design the iconic look for Bastion, a popular 2011 action RPG. Her work will also be seen in Transistor, a spiritual follow-up to Bastion, which releases on May 20th for PC and PS4.

Zee enjoys the challenge of creating a strong, likeable protagonists in her art and when working on creating the worlds feature in Super Giant games. She’s particularly proud of her work on Transistor‘s female protagonist, who’s strong and attractive, but not in the over-sexualized way that pervades popular videogame culture. “I personally love creating female characters because I find there are many more ways to make a woman attractive to both men and women of all orientations,” Zee told Sarah the Rebel of Nerdy-but-Flirty in an interview about her work on Transistor. This is a lesson for artists of all mediums: painting, writing, film-making, etc.

“I have a love of color that I find difficult to restrain,” she told Nerdy-but-Flirty. “But [I] definitely believe muted palettes have their place and produce a mood that can work in service of [a] slightly more personal, more serious story.”

Zee herself finds motivation and inspiration for Transistor from many places, including “John William Waterhouse is an old favorite, and his use of muted palette with vibrant atmosphere was a huge inspiration, as was Gustav Klimt, an artist whose interesting shapes and flare for dramatic presentation seemed to naturally synthesize with the cyberpunk aesthetic.”

More of Jen Zee’s artwork can be found on her DeviantArt page, or on her official blog.

The post The Super Giant Artwork of Jen Zee appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.