Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 13

August 8, 2011

The S&P Brainpower Downgrade

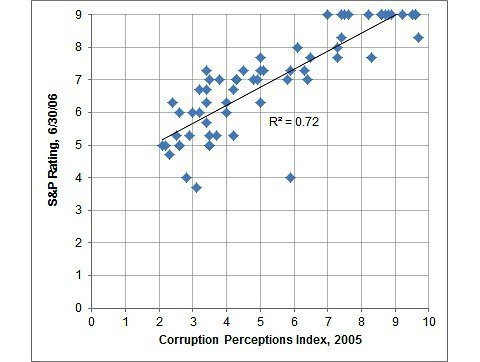

Nate Silver gently suggests the S&P analysts may not be terribly bright, brainwise:

What factors is S.&P. looking at when it rates sovereign debt? A country’s debt-to-G.D.P. ratio? Its inflation rate? The size of its annual deficits?

S.&P. does look at each of these factors. But it also places very heavy emphasis on subjective views about a country’s political environment. In fact, these political factors are at least as important as economic variables in determining their ratings.

For instance, the S.&P. ratings have an extremely strong relationship with a measure of political risk known as the Corruption Perceptions Index, which is published annually by Transparency International. These ratings have been the subject of much criticism because they are highly subjective, relying on a composite of surveys conducted among “experts” at international organizations who may have spent little time in most of the countries and who may instead base their judgments on cultural stereotypes.

I don’t know whether or not S.&P. looks at these ratings. But the fact that the two sets of ratings are so closely related is troublesome. It suggests that S.&P. is making a lot of judgment calls about countries they have no particular knowledge about. Keep in mind that even when it comes to the United States, S.&P. made a $2 trillion error that reflects their lack of understanding of the way that bills are scored by the Congressional Budget Office. Are we to expect that they add value based on their perceptions of the political climate in Kazakhstan, or Cyprus, or Uganda?

Meanwhile, the blog Economics Of Contempt, living up to its moniker, suggests the same thing, only way less gently:

S&P was flat-out wrong — no caveats. They are, to put it very bluntly, idiots, and they deserve every bit of opprobrium coming their way. They were embarrassingly wrong on the basic budget numbers, as everyone knows now, so they were forced to remove that section from their report, and change their rationale for the downgrade. (Always a sign that you’re dealing with hacks.)

S&P’s rationale for the downgrade now is based entirely on their subjective political judgement — and their political judgement is wrong. The brilliant political minds over at S&P said that “the downgrade reflects our view that the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of American policymaking and political institutions have weakened at a time of ongoing fiscal and economic challenges.” ...

Look, I know these S&P guys. Not these particular guys — I don’t know John Chambers or David Beers personally. But I know the rating agencies intimately. Back when I was an in-house lawyer for an investment bank, I had extensiveinteractions with all three rating agencies. We needed to get a lot of deals rated, and I was almost always involved in that process in the deals I worked on. To say that S&P analysts aren’t the sharpest tools in the drawer is a massiveunderstatement.

Naturally, before meeting with a rating agency, we would plan out our arguments — you want to make sure you’re making your strongest arguments, that everyone is on the same page about the deal’s positive attributes, etc. With S&P, it got to the point where we were constantly saying, “that’s a good point, but is S&P smart enough to understand that argument?” I kid you not, that was a hard-constraint in our game-plan. With Moody’s and Fitch, we at least were able to assume that the analysts on our deals would have a minimum level of financial competence.

I’ve seen S&P make far more basic mistakes than the one they made in miscalculating the US’s debt-to-GDP ratio. I’ve seen an S&P managing director who didn’t know the order of operations, and when we pointed it out to him, stopped taking our calls. Despite impressive-sounding titles, these guys personify “amateur hour.” (And my opinion of S&P isn’t just based on a few deals; it’s based on countless deals, meetings, and phone calls over 20 years. It’s also the opinion of practically everyone else who deals with the rating agencies on a semi-regular basis.)

I still think S&P's political judgment is probably correct, but perhaps in a kind of blind squirrel sense.

What Would It Look Like If Teachers Were Treated Like Professionals?

[image error]Last week I argued that part of treating teachers like professionals means breaking the rigid union-mandated tenure-track:

The old liberal slogan always demanded that we "treat teachers like professionals." That entails some measure of accountability -- we can debate the metrics -- which allows both that very bad teachers be fired and that very good ones can obtain greater pay and recognition. That's the definition of a professional career track, and the current absence of it is what drives most of the best college graduates into other professions.

Mark Palko objects:

Putting aside the compensation question for the moment, Chait is listing being easy to fire as part of the definition of being a professional. Does anyone else find that a bit odd?

Andrew Gelman is deeply impressed with this objection. I think Palko's point is pretty obviously just wordplay, but I suppose I didn't express myself as well as I could have. Being a professional, to most people, means having the opportunity to gain higher pay and recognition with greater success. Such a system also, almost inevitably, entails the possibility of having some consequences for failure. Teaching is very different than most career paths open to college graduates in that it protects its members from firing even in the case of gross incompetence, and it largely denies them the possibility to rise quickly if they demonstrate superior performance.

Obviously the realistic possibility of being fired for gross incompetence would not in and of itself do much to attract more highly qualified teachers, but the opportunity to receive performance-differentiated pay would.

The Millenialist Temptation

Ross Douthat's column today makes a sharp point about the myth of the realigning election, and how this encourages partisans to dream of total victory:

This “realignment theory” was embraced by many scholars because it fit the historical record so well. Every 30 to 40 years, it seemed, the American political order had decisively turned over: in 1800, when Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans trounced John Adams’s Federalists; in 1828, when the Democratic-Republicans split into the Democrats and the Whigs; and then on down through Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 victory, William McKinley’s 1896 consolidation of a Republican majority, and the emergence of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition....

This dream has hovered over national leaders from Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan to Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich. But it has loomed larger in the last decade, as our politics have grown more polarized and our country has suffered through a series of dislocations and disasters. Events like 9/11 and the Great Recession have persuaded partisans on both sides that a dramatic realignment is imminent; the breadth of the ideological divide has convinced them that it’s necessary.

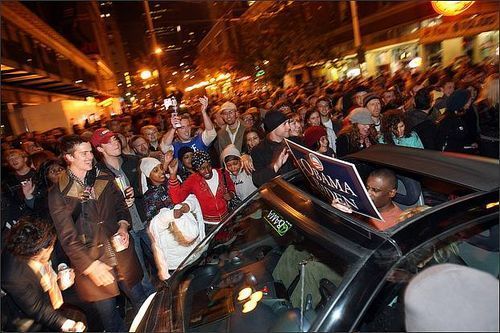

Douthat somewhat misleadingly conflates the millenial aspirations of Democrats and Republicans, when the former have shown far greater willingness to compromise, even in their moments of triumph. But I think this observation provides the right context in which to understand the appeal of Drew Westen's nonsensical argument that President Obama has broken the liberal dream. The reality is that Democrats won two huge victories in 2006 and 2008 running against a wildly unpopular incumbent presiding over a terrible economy. They then advanced their agenda in the face of powerful systemic constraints, and lost their majorities because they were holding power during an even more terrible economy.

The liberal dreams of what policy and political outcomes Obama's election would lead to were always wildly unrealistic. The correct interpretation of these events is that things change and nothing is as great as it seems in the throes of victory, or as terrible as it appears in the wake of defeat. Instead the predominant liberal reaction is that Obama betrayed their hopes, and we've entered a new period of blackness that will not lift until a new progressive champion rides in to vanquish the right once and for all.

Michelle Bachmann's Intellectual Worldview

[image error]A huge proportion of the reporting and commentary around Michele Bachmann has revolved around the general theme "she's crazy." Yet I've found most of it immensely dissatisfying. Inevitably, we are promised a great feast of crazy, and instead served a few dissatisfying morsels -- a historical misstatement here, a rhetorical flourish there, but nothing greatly out of character with how the other Republican presidential candidates behave.

Ryan Lizza's terrific profile of Bachmann finally delivers what we've been waiting for. And he does it by doing what nobody else has done -- examining her worldview seriously and with depth. It's difficult to summarize, but Ryan finds a massive trove of intellectual influences that are very, very radical. Bachmann emerges from a fairly coherent far-right Christian school of thought. Among other things, it lends some perspective to the way we use terms like "theocracy." Someone like Rick Perry may transform the country into the kind of place where non-Christians are a kind of second-class citizen, but Bachmann is truly a theocrat, who believes in the absolute supremacy of biblical law.

This is just one segment of the piece, but it traces the relation between what appear to be odd gaffes and her genuine belief structure:

Bachmann’s comment about slavery was not a gaffe. It is, as she would say, a world view. In “Christianity and the Constitution,” the book she worked on with Eidsmoe, her law-school mentor, he argues that John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams “expressed their abhorrence for the institution” and explains that “many Christians opposed slavery even though they owned slaves.” They didn’t free their slaves, he writes, because of their benevolence. “It might be very difficult for a freed slave to make a living in that economy; under such circumstances setting slaves free was both inhumane and irresponsible.”

While looking over Bachmann’s State Senate campaign Web site, I stumbled upon a list of book recommendations. The third book on the list, which appeared just before the Declaration of Independence and George Washington’s Farewell Address, is a 1997 biography of Robert E. Lee by J. Steven Wilkins.

Wilkins is the leading proponent of the theory that the South was an orthodox Christian nation unjustly attacked by the godless North. This revisionist take on the Civil War, known as the “theological war” thesis, had little resonance outside a small group of Southern historians until the mid-twentieth century, when Rushdoony and others began to popularize it in evangelical circles. In the book, Wilkins condemns “the radical abolitionists of New England” and writes that “most southerners strove to treat their slaves with respect and provide them with a sufficiency of goods for a comfortable, though—by modern standards—spare existence.”

African slaves brought to America, he argues, were essentially lucky: “Africa, like any other pagan country, was permeated by the cruelty and barbarism typical of unbelieving cultures.” Echoing Eidsmoe, Wilkins also approvingly cites Lee’s insistence that abolition could not come until “the sanctifying effects of Christianity” had time “to work in the black race and fit its people for freedom.”

In his chapter on race relations in the antebellum South, Wilkins writes:

Slavery, as it operated in the pervasively Christian society which was the old South, was not an adversarial relationship founded upon racial animosity. In fact, it bred on the whole, not contempt, but, over time, mutual respect. This produced a mutual esteem of the sort that always results when men give themselves to a common cause. The credit for this startling reality must go to the Christian faith. . . . The unity and companionship that existed between the races in the South prior to the war was the fruit of a common faith.

For several years, the book, which Bachmann’s campaign declined to discuss with me, was listed on her Web site, under the heading “Michele’s Must Read List."

What I love is that Ryan immediately proceeds to quote Bachmann describing her passion for "liberty." One consistent aspect of the Tea Party movement is a certain brand of Constitutional fetishism. Liberals have viewed the Constitution as a great but flawed document that pointed the way for America's broader principles but required updating and perfection over subsequent generations. The right has instead fetishized it as a perfect document. That principle, and the right's professed love f liberty, come into fairly dramatic contradiction over an issue like slavery. The argument of somebody like Wilkin's is ultimately the glue that holds those apparently contradictory positions together. How can the Constitution have been perfect and liberty the vital principle? Because slavery wasn't so bad.

Now, to be sure, Bachmann is obviously not pro-slavery. But she is the product of a worldview that comes from some very, very dark places.

Drew Westen's Nonsense

There are some strong criticisms to be made of the Obama administration from the left, especially concerning Obama's passive response to the debt ceiling hostage crisis, and his frightening willingness to give away the store to John Boehner. I've made many of these criticisms myself. But Drew Westen's lengthy, attention-grabbing Sunday New York Times op-ed is not a strong criticism. It's a parody of liberal fantasizing.

Westen is a figure, like George Lakoff, who arose during the darkest moments of the Bush years to sell liberals on an irresistible delusion. The delusion rests on the assumption that the timidity of their leaders is the only thing preventing their side from enjoying total victory. Conservatives, obviously, believe this as much or more than liberals. But the liberal fantasy has its own specific character. It is unusually fixated on the power of words. Before Westen and Lakoff, Aaron Sorkin has indulged the fantasy of a Democratic president who would simply advocate for unvarnished liberalism (defend the rights of flag burners, confiscate all the guns) and sweep along the public with the force of his conviction.

Westen's op-ed rests upon a model of American politics in which the president in the not only the most important figure, but his most powerful weapon is rhetoric. The argument appears calculated to infuriate anybody with a passing familiarity with the basics of political science. In Westen's telling, every known impediment to legislative progress -- special interest lobbying, the filibuster, macroeconomic conditions, not to mention certain settled beliefs of public opinion -- are but tiny stick huts trembling in the face of the atomic bomb of the presidential speech. The impediment to an era of total an uncompromising liberal success is Obama's failure to properly deploy this awesome weapon.

Westen locates Obama's inexplicable failure to properly use his storytelling power in some deep-rooted aversion to conflict. He fails to explain why every president of the postwar era has compromised, reversed, or endured the total failure of his domestic agenda. Yes, even George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan infuriated their supporters by routinely watering down their agenda or supporting legislation utterly betraying them, and making rhetorical concessions to the opposition. (Ronald Reagan boasted of increasing agriculture subsidies and called for making the rich pay "their fair share" as part of a tax reform that did in fact increase the tax burden on the rich; Bill Clinton said "the era of big government is over" and ended welfare as an entitlement; etc., etc.)

To find a case of a president successfully employing his desired combination of "storytelling" and ideological purity, Westen reaches back to the example of Franklin Roosevelt:

In similar circumstances, Franklin D. Roosevelt offered Americans a promise to use the power of his office to make their lives better and to keep trying until he got it right. Beginning in his first inaugural address, and in the fireside chats that followed, he explained how the crash had happened, and he minced no words about those who had caused it. He promised to do something no president had done before: to use the resources of the United States to put Americans directly to work, building the infrastructure we still rely on today. He swore to keep the people who had caused the crisis out of the halls of power, and he made good on that promise. In a 1936 speech at Madison Square Garden, he thundered, “Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me — and I welcome their hatred.”

Westen's use of this example is wildly, redundantly incorrect, in ways that helpfully summarize his most fundamental errors. First, Roosevelt did not take office "in similar circumstances." He took office three years into the Great Depression, after the economy had bottom out, and immediately presided over rapid economic growth (unemployment plunged from a high of 24.9% in 1933 to 14.3% in 1937.) His administration's primary contribution to this rapid recovery was to eliminate the most harmful monetary policy error by loosening the gold standard.

Did Roosevelt promise to support expansionary fiscal policy to combat the depression? Well, yes, but only after initially promising to cut the deficit. Westen strongly implies that Roosevelt persuaded Americans to understand the efficacy of government spending in order to combat mass unemployment. In fact, he utterly failed to convince Americans to support fiscal stimulus:

Gallup Poll [December, 1935]

Do you think it necessary at this time to balance the budget and start reducing the national debt?

70% Yes

30 No

Gallup Poll [May, 1936]

Are the acts of the present Administration helping or hindering recovery?

55% Helping

45 Hindering

Gallup Poll (AIPO) [November, 1936]

DO YOU THINK IT NECESSARY FOR THE NEW ADMINISTRATION TO BALANCE THE BUDGET?

65% YES

28 NO

7 NO ANSWER

As you can see, Roosevelt generally enjoyed broad public support despite having no success at persuading Americans to share his Keynesian view. (Westen subsequently writes, "if you give [Americans] the choice between cutting the deficit and putting Americans back to work," they'll favor the latter. But the problem is that Americans don't see that as a choice, which is wrong, but not a form of wrongness any president has succeeding in correcting.)

Roosevelt's fortunes are a testament to the degree to which political conditions are shaped by the state of the economy. Roosevelt was wildly popular during the recovery, which coincided with his populist 1936 reelection campaign. Yet Roosevelt's most populist governing period came after that election, when he took on the Dixiecrats. That period coincided with an economic relapse (caused by his premature abandonment of fiscal stimulus) which in turn severely damaged Roosevelt's popularity. All these facts are rather hard to square with Westen's narrative -- not a surprise, I suppose, given his professed favoring of simple narrative over complex facts.

Obama took office at the cusp of a massive worldwide financial crisis that was bound to inflict severe damage on himself and his party. That he faced such difficult circumstances does not absolve him of blame for any failures. It sets the bar lower, but the bar still exists. How should we judge Obama against it? I would argue that both the legislative record of 2009-2010 and Obama's personal popularity level exceed the expectation level -- facing worse economic conditions than the last two Democratic presidents at a similar juncture, Obama is far more popular than Jimmy Carter and nearly as popular as Bill Clinton, and vastly more accomplished than both put together.

Obviously this is the crux of the dispute, and I don't have the time and space to defend this larger judgment here. But Westen offers almost nothing but hand-waving and misstatements. He blames Obama for the insufficiently large stimulus without even mentioning the role of Senate moderate Republicans, whose votes were needed to pass it, in weakening the stimulus. An argument can be made that Obama could have secured a larger stimulus through better legislative tactics, but Westen does not make this case, or even flick at it. A foreign reader unfamiliar with our political system would come away from Westen's op-ed believing Obama writes laws by fiat.

Westen 's complaint against Obama is rooted primarily in a lack of factual understanding of what Obama has done. Westen castigates Obama for promising not to support entitlement cuts without higher revenue and then turning around and supporting a deal doing exactly that:

The president tells us he prefers a “balanced” approach to deficit reduction, one that weds “revenue enhancements” (a weak way of describing popular taxes on the rich and big corporations that are evading them) with “entitlement cuts” (an equally poor choice of words that implies that people who’ve worked their whole lives are looking for handouts). But the law he just signed includes only the cuts.

In fact, the budget agreement does not include any entitlement cuts. It consists of cuts to domestic discretionary (i.e., non-entitlement spending.)

Likewise, he implies that Obama supported the undermining of the coverage expansion in his health care reform by cutting Medicaid:

He supports a health care law that will use Medicaid to insure about 15 million more Americans and then endorses a budget plan that, through cuts to state budgets, will most likely decimate Medicaid and other essential programs for children, senior citizens and people who are vulnerable by virtue of disabilities or an economy that is getting weaker by the day.

This is also totally false. The budget agreement contains no cuts to Medicaid or to state budgets. The automatic cuts that would go in effect should Congress fail to agree on a second round of deficit reduction exempt Medicaid. Both Obama and the GOP have consistently said that Obama has refused to place the Affordable Care Act on the negotiating table. And, finally, states are legally required to maintain Medicaid benefits -- which is to say, Westen's scenario of fictional cuts to state budget resulting in the decimating of Medicaid could not happen even if it were real.

The most inexcusable factual errors in Westen's essay have been documented by Andrew Sprung, who points out some of the occasions Obama has used exactly the kind of rhetoric Westen accuses him of refusing to deploy. Westen is apparently unaware, to take one example, that Obama repeatedly and passionately argued for universal coverage. The fact of his unawareness is the most devastating rejoinder to his entire rhetoric-centered worldview. If even a professional follower of political rhetoric like Westen never realized basic, repeated themes of Obama's speeches and remarks, how could presidential rhetoric -- sorry, "storytelling" -- be anywhere near as important as he claims? The clear reality is that Americans pay hardly any attention to what presidents say, and what little they take in, they forget almost immediately. Even Drew Westen.

August 7, 2011

How S&P Got Obama to Defend The Tea Party

There is an absurd quality to the debate over the S&P downgrade that captures the perverse incentive structure of our political system. House Republicans successfully played chicken with the debt ceiling and have vowed to continue doing so. As a result S&P downgraded Treasury debt:

The "conclusion was pretty much motivated by all of the debate about the raising of the debt ceiling," John Chambers, chairman of S&P's sovereign ratings committee, said in an interview. "It involved a level of brinksmanship greater than what we had expected earlier in the year."

Meanwhile, the political effects of the downgrade will primarily harm the Obama administration. So now the Obama administration is fiercely contesting S&P. In other words, a ratings agency has sensibly concluded that the Republican Party poses a long-term threat to the stability of the U.S. financial system, and the Obama administration insists otherwise:

The day after Standard & Poor’s took the unprecedented step of stripping the United States government of its top credit rating, the ratings agency offered a full-throated defense of its decision, calling the bitter stand-off between President Obama and Congress over raising the debt ceiling a “debacle.” It warned that further downgrades may lie ahead. ...

Officials at the White House and Treasury criticized S.& P.’s move as based on faulty budget accounting that did not factor in the just-enacted deal for increasing the debt limit.

The math may be faulty. But the basic point of the downgrade seems dead-on -- the existence of a Republican Party that theologically opposes higher revenue and is pledged to risk worldwide financial cataclysm on a regular basis in order to advance is agenda poses a fairly serious risk.

I'm reminded of the the Monty Python skit in which Eric Idyl defends gangster Dimsdale Piranha for having nailed his head to the floor. (See the scene beginning at 5:17):

That's what I picture when I imagine the exchange between S&P and Tim Geithner:

S&P: We've been told that John Boehner threatened to not raise the debt ceiling unless you agreed to implement his agenda.

Geithner: No, no. Never, never. He was a smashing bloke. He used to give his mother flowers and that. He was like a brother to me.

S&P: We have video of Boehner threatening to not raise the debt ceiling unless you agreed to implement his agenda.

Geithner: Oh, well -- he did that, yeah.

S&P: Why?

Geithner: Well he had to, didn't he? I mean, be fair, there was nothing else he could do.

I understand the logic here, but it's just a little odd for the Democratic-controlled Treasury Department to be pleading that the Republicans aren't really dangerous maniacs at all.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

August 6, 2011

We're Being Downgraded For The Wrong Reasons

S&P's argument contains a crucial flaw, but its ultimate conclusion is right. The American political system is much riskier and less stable than it was before.

The basic situation is that we have a political system that, in most cases, requires both parties to agree on major policy changes. One of those parties is only willing to bring revenue in line with outlay if the ideological terms of that adjustment are 100% congenial to their demands -- and even then, it is far from clear that the Republican approach would actually succeed in stabilizing the deficit. In the short term, action on a fiscal adjustment is hopeless.

Now, what about that flaw? The flaw is that the S&P seems to believe that Republican opposition to tax increases can block any fiscal adjustment indefinitely. It writes:

Compared with previous projections, our revised base case scenario now assumes that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, due to expire by the end of 2012, remain in place. We have changed our assumption on this because the majority of Republicans in Congress continue to resist any measure that would raise revenues, a position we believe Congress reinforced by passing the act.

That is a total misread of the debt ceiling showdown. It did demonstrate Republican opposition to increasing revenue. But the crucial reality is that the Bush tax cuts expire after 2012 barring action by Congress. What's more, Republicans have signaled that they will not extend the tax cuts on income below $250,000 a year unless the tax cuts on income over that level are extended as well. As I've argued endlessly, this provides a huge opportunity to the Obama administration. It can simply refuse to extend the tax cuts for the rich, demand a clean tax cut bill for income under that level, and when Republicans refuse, blame them for hiking middle class taxes while taking quiet satisfaction as projected revenue increases by $4.6 trillion, solving the medium-term deficit problem. I can't be sure by any means that this will happen. But this is an open question, and the debt ceiling deal did not reduce the likelihood of a tax stalemate.

So the risk does not lie between now and the end of 2012, and there's a decent chance that the stalemate will actually solve the problem. However, the long-run political risk is quite severe. No other advanced country has a major political party influenced by supply-side economics and the moral teachings of Ayn Rand, and therefore, no other major political party can match the GOP's theological opposition to revenue. One result is that the Republican Party is always going to use its political power to reduce revenue, which means that the U.S. budget can never be stable for an extended period of time. If a center-left coalition succeeds in stabilizing the budget, Republicans will eventually destabilize it. It is difficult to imagine the GOP, as it's currently structured, encountering conditions in which they believe taxes are not too high.

Presidential systems of government, with the legislature and the executive often representing opposing parties, are inherently prone to crises of legitimacy. The declared Republican goal of using the debt ceiling as an instrument to extract policy concessions on a regular basis adds an explosive new element of long-term risk.

In a nutshell, when you have a political party that does not agree that revenue levels must bear a relationship to outlays, and is willing to foment a systemic crisis in order to maximize its leverage, you're in trouble.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

1933 or 2010?

[Guest post by Gabriel Debenedetti]

While working on a project that involves digging through TNR's voluminous archives, I stumbled upon a passage that struck a nerve, particularly given Thursday's momentous stock slide. In an editorial presciently titled "Curtain Call for Congress" (recent polls have our Congress at less than 20 percent approval), the editors write:

The biggest gap in the Recovery legislation of last spring was the failure to do anything final about the banks. It is frequently said that the President missed the greatest opportunity of his administration because, last March, he did not take over and reorganize the whole banking system. It still needs to be done.

So when was this apparently searing disavowal of Obama's economic policy published, 2010? Actually, it's straight from 1933, and FDR bears the brunt of the criticism. The piece goes on to set straight the magazine's early view of the New Deal, but based on that selection it might as well have expounded on the debt ceiling.

For what it's worth, only one intern was able to correctly guess the year of publication.

August 5, 2011

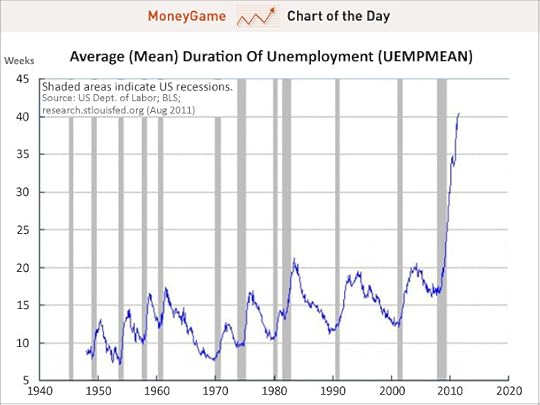

Chart Of The Day

Technically, the headline is misleading, as it implies that I post a chart every day, when in fact I post them irregularly. "Chart Of The Day" just seemed more enticing as a headline than "Chart." Would you click on a blog item entitled "Chart?" I would not.

Anyway, the chart:

The Nader-Kristol Axis Of... Well, Not "Good"

Ralph Nader advocates a left-wing primary challenge (though not by himself) to President Obama, apparently unaware that his credibility to make this case might be limited by certain electoral events. Bill Kristol catches a whiff and fans the flames, arguing that such a challenge will aid the left-wing cause:

So what of the Democrats? Surely they’ll produce a primary challenger to their Wall Street coddling, Afghan war prosecuting, drone assassination ordering, and debt ceiling deal-signing occupant of the Oval Office! That opponent might perhaps not be “serious,” but his effort could be attention getting, issue raising, and meaningful for the future. Far be it from me to give advice to the professional left. But it has been a sign of the health and vitality of the right over the last forty years that it could at least produce primary challengers to moderate and establishment Republican officeholders. For the left to roll over totally for Obama, after giving Clinton a pass in 1996, would be a sign of a massive failure of conviction and imagination and nerve.

So, Russ Feingold or Dennis Kucinich, Robert Reich or Paul Krugman: Won’t one of you be willing to raise the progressive banner high? Across the ideological chasm, THE WEEKLY STANDARD will salute you!

I think I detect an open wink here, signalling to the reader that Kristol understands full well that a primary challenger would not actually wind up pushing American policy leftward over the long run. But of course Kristol actually is an operative who uses his perch to wage political campaigns rather than honestly describe the world as he sees it. It's genuinely unclear whether this particular item is the Machiavellian Kristol, or Kristol openly satirizing his Machiavellian style.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers