Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 10

August 12, 2011

Partisanship And GOP Anti-Tax Mania

Last night at the Republican debate when every candidate declared they would oppose a deficit reduction deal consisting of over 90% spending cuts captured the party's anti-tax monomania. (It also left plenty of room for future dorm-room hypothetical scenarios: What about a 99-1 ratio? What if space aliens threatened to destroy Earth unless we raised taxes on Bill Gates by a dollar and it had to be done through a legislated tax hike rather than a voluntary donation?)

Meanwhile, there are murmuring of dissent within the conservative movement. President Obama's spurned offer to Republicans was dismayingly generous -- a budget deal consisting of 80% spending cuts, with all new revenue coming in the context of a reformed tax code with far lower rates. Doesn't anybody on the right think the GOP should have taken that deal -- if nothing else, to protect against the risk of the Bush tax cuts expiring, and far higher taxes ensuing?

It turns out that some of them do think that. They simply have to couch their argument in terms that play to the GOP's partisan animus. In today's Wall Street Journal, former Bush administration economist Glenn Hubbard advocates that kind of revenue-enhancing tax reform bargain. But he presents it as a policy option that Obama fervently opposes:

'What is tax reform?"

That's the Jeopardy-like question matching the answer: "The best step the government could take now to promote growth and employment." The Obama administration has been responding with "What are higher marginal tax rates and more stimulus?" ...

President Obama's repeated calls to raise marginal tax rates on upper-income Americans call to mind the image of a dog chasing a car, then stopping to wonder what to do with it when he catches it.

And last week Charles Krauthammer likewise advocated a tax code with a broader base, lower rates and targeted revenue levels above the status quo, but carefully avoiding any reference to the fact that Obama offered precisely this bargain and House Republicans nixed it.

It would seem to me that pointing out that Obama has offered this deal would be an important selling point. You could say, not only is this advance conservative policy goals, Obama has already offered to sign it! But instead they go out of their way not to mention that.

What's the psychology here? One possibility is that they're trying to avoid helping Obama by admitting that his tax position is more reasonable than the GOP's. Another -- not mutually exclusive -- is that they think the only way to sell this idea to conservatives is to present it as a rebuke to Obama. Neither of these possibilities reflect well on the level of intellectual discourse within the conservative movement.

President Perry And Speaker Pelosi

Tom Jensen shouts for people to pay attention to the growing chance that Democrats take back the House:

I think most national pundits continue to be missing the boat on how possible it is that Democrats will retake control of the House next year. We find Democrats with a 7 point lead on the generic Congressional ballot this week at 47-40. After getting demolished with independent voters last year, they now hold a slight 39-36 advantage with them. And in another contrast to 2010 Democratic voters are actually slightly more unified than Republicans, with 83% committed to supporting the party's Congressional candidates compared to 80% in line with theirs.

This poll is certainly not an outlier. We have looked at the generic ballot 11 times going back to the beginning of March and Democrats have been ahead every single time, by an average margin of about 4 points. This 7 point advantage is the largest Democrats have had and if there was an election today I'm think that they'd take back the House. Of course there's plenty of time between now and next November for the momentum to shift back in the other direction.

Why is this possibility receiving so little attention? Wave elections in the House usually involve a backlash against the incumbent party, so it seems hard to imagine a pro-Democratic wave occurring while President Obama sits in office during an economic crisis. But the Republican Party remains deeply discredited from the Bush years. Republicans largely avoided voter blame in 2010, in part by dint of not controlling anything, but the high-profile way in which they've exercised power has given the party more responsibility for the status quo than a Congressional party usually has.

What's more, the House Republicans seem to be pursuing a strategy that hurts Obama and themselves simultaneously. The wild behavior of the House GOP caucus has dragged down Obama, but dragged the House GOP caucus down much farther. It's almost a suicide mission to help elect a Republican president, though I doubt House Republicans actually see it in those terms.

And this collapse has occurred largely outside the context of a debate over the Ryan budget, which will probably dominate the House Democratic message in the fall. Republicans could insulate themselves from that vote by cutting a Grand Bargain, by they simply do not want to. I can hardly think of another example of high-level politicians so unable to discern their political self-interest. Would they rather help their party win the White House than keep their own majority? Or are they simply not thinking clearly about the politics?

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

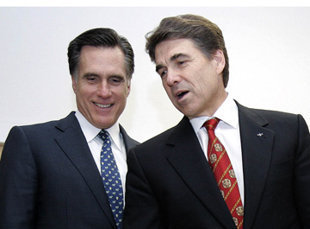

Rick Perry, The Hair Apparent

Most political reporters came away from last night's Republican debate impressed with Mitt Romney. I came away wondering what possible advantage Romney could have over Rick Perry from the perspective of a Republican voter. It is true that Romney towered over the rest of the field, both literally in in his general alpha-male ability to project a sense of command. But his weaknesses are vast and unexploited. Last night Romney did not even bother to deny that his health care plan was a replica of President Obama's, instead resting his entire defense on the fact that he only imposed it at the state level. Federalism is not a distinction anybody actually cares about, as demonstrated when Romney himself cast it aside in a subsequent exchange over gay marriage.

Tim Pawlenty, who I massively overestimated, seems unable to expose Romney's ideological heresies. Bachmann, I think could do it, but at this point she is more interested in establishing herself as a mainstream Republican figure -- leaning too heavily on anti-Romney attacks could make her appear as the voice of a dissident faction. Two strategists for rival campaigns laid out the dynamic fairly persuasively:

A senior Bachmann aide, Ed Goeas, told POLITICO that the campaign sees three spaces in the race: One for Romney, who Bachmann’s aides believe is capped at less than 40 percent of Republican support; one for the grassroots favorite Bachmann; and one for Perry, if his campaign succeeds in taking off. A Pawlenty adviser, meanwhile, argued that Bachmann has the most to lose from Perry’s entry, and that he will cut into her grassroots base.

I think we're probably looking a a three-way Romney-Perry-Bachmann race. Perry holds the dominant position here -- he can expand into either Romney or Bachmann's support, while both of the others are pinned to one flank of the party.

I think Romney, not Bachmann, has the most to lose. Perry is Romney without the weaknesses -- a tall, handsome, alpha male with extraordinary hair who fulfills the cinematic vision of a president. Perry has made his career doing exactly what his role calls out for him here -- knifing less-ideologically pure Republicans and playing to the party's id. Ask yourself: what Republican voter would prefer Romney to Perry? Perhaps Mormons, or those who worry the party has grown too extreme, or those who think it risks defeat by appearing too stridently conservative. That doesn't sound to me like a majority of the primary electorate.

August 11, 2011

&c

How Doug Holtz-Eakin’s argument against the stimulus became an argument for it.

Michael Lewis goes to Germany, writes an article. A great read ensues.

Meeting with the most important economic policymaker in the world is something Obama probably should do.

Dan Drezner is gloomy about the world.

Mitt Romney loses the Jewish vote.

Jonathan Chait: King Of Two Media

Jonathan Chait will appear on Charlie Rose tonight to discuss what he recently called “Drew Westen’s Nonsense.” Check your local listings!

Romney's Clever Evasiveness

I didn't wake up intending to let Mitt Romney take over my blog today, but after a long period of inaccessibility, he's made himself available to questions in a way that reveals a lot about him. One thing that comes across is that Romney seems like a kind of character that, in recent years, has been associated with Democratic politicians, not Republican politicians. He's very smart, and he can use his intelligence to answer questions in ways that are literally true but feel somewhat evasive. Here's Romney confronting a reporter who picks apart his claims that his campaign is not "run by lobbyists":

If you couldn't watch the exchange, Romney is not saying that he doesn't have lobbyists in his campaign, because he does. He means that he's identifying one person as the person who runs his campaign, and she does not happen to be a lobbyist.

Meanwhile, here is Romney's response to stories showing that the S&P upgrade he boasted of getting as governor depended on tax increases:

Q: In 2004, as governor of Massachusetts, you closed corporate tax loopholes on big banks to raise revenue and balance the state budget. If you were elected president, would you do the same thing and look at the revenue side of the equation to balance the federal budget?

ROMNEY: The question is, as governor of Massachusetts I closed loopholes on big banks that were abusing our tax system and would I do the same as president. Let me tell you, let’s describe what is a loophole and what’s raising taxes. In my opinion, a loophole is when someone takes advantage of a tax law in a way that wasn’t intended by the legislation. And we had in my state, for instance, we had a special provision for real estate enterprises that owned a lot of real estate. And it provided lower tax rates in certain circumstances and some banks had figured out that by calling themselves real estate companies, they could get a special tax break. And we said, ‘No more of that, you’re not gonna game with the system.’ And so if there are taxpayers who find ways to distort the tax law and take advantage of what I’ll call loopholes in a way that are not intended by Congress or intended by the people, absolutely I’d close those loopholes. But there are a lot of people who use the loophole to say, ‘Let’s just raise taxes on people.’ And that I will not do. I will not raise taxes.

Romney here is relying on a sloppily-worded question. There is a technical distinction between tax loopholes and tax breaks. If I hire a lobbyist to carve out a special tax break for bloggers names Jonathan who joined the New Republic in 1995, that is a tax break, not a loophole, because it was intended. If I hire a tax lawyer to find a way to minimize my income that doesn't take advantage of an intended tax subsidy, that's a loophole. People, though, use the two terms interchangeably.

Romney sold S&P on a Massachusetts plan to reduce corporate tax breaks:

“He, like everybody, when they’re raising corporate taxes, calls it ‘closing tax loopholes,’” said Michael Widmer, president of the business-backed Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation. “A couple of these were real loopholes but by and large they were increases in corporate taxes by changes in tax policy.”

But a reporter asked him about loopholes, so he replied in a way that squared the circle. Clever! And also something George W. Bush would never have thought of.

Romney Is Right: Corporations Are People

The controversy du jour seems to be Mitt Romney's claim, in response to hecklers, that corporations are people:

ROMNEY: We have to make sure that the promises we make — and Social Security, Medicaid, adn Medicare — are promises we can keep. And there are various ways of doing that. One is, we could raise taxes on people.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Corporations!

ROMNEY: Corporations are people, my friend. We can raise taxes on —

AUDIENCE MEMBER: No, they’re not!

ROMNEY: Of course they are. Everything corporations earn also goes to people.

AUDIENCE: [LAUGHTER]

ROMNEY: Where do you think it goes?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: It goes into their pockets!

ROMNEY: Whose pockets? Whose pockets? People’s pockets! Human beings, my friend. So number one, you can raise taxes. That’s not the approach that I would take.

There is a controversy over whether corporations are people from the standpoint of law, with implications for free speech and other policy areas. That is not the point Romney was making. Romney was saying that taxes on corporations are in fact borne by people. Romney probably wouldn't admit that these are people who partially or completely own corporations, and thus far richer in the aggregate than the general public. But the fact is that they are people. Raising taxes on corporations is simply raising taxes on a certain category of people.

Our Non-Lavish Welfare State

Brink Lindsey, via an approving , makes a seemingly obvious point that is in fact half wrong: "the looming choice between our relatively lavish welfare state and our relatively modest tax bill cannot be delayed much longer." We do have a relatively modest tax bill. But do we have a relatively lavish welfare state? Certainly not relative to other advanced countries:

Even that chart exaggerates the lavishness of the U.S. welfare state. The main distinction between American social spending and social spending elsewhere is that we pay far more for health care, and we don't generally consider it better than citizens of other countries deem their health care. If you were to pro-rate the chart to account for the fact that we're paying up to twice as much for pretty much the same thing (health care), it would be even more clear that the U.S. welfare state is relatively sparse.

The Romney Dilemma

Mitt Romney has boasted that Massachusetts received an upgrade from S&P during his governorship. Ben Smith and Jonathan Weisman report that Romney's pitch to S&P boasted of tax hikes his predecessor had just signed. Weisman:

Documents obtained by The Wall Street Journal Wednesday through the Freedom of Information Act show the Romney administration’s pitch to S&P in late 2004included the boast that “The Commonwealth acted decisively to address the fiscal crisis” that ensued after the terrorist attacks of 2001. Bulleted PowerPoint slides laid out the actions taken, including legislation in July 2002 to increase tax revenue by $1.1 billion to $1.2 billion in fiscal 2003 and $1.5 billion to $1.6 billion in fiscal 2004; tax “loophole” legislation that added $269 million in “additional recurring revenue,” and tax amnesty legislation that added $174 million. The final bullet: “FY04 budget increased fees to raise $271 million yearly.”

The efforts contradict the position that Mr. Romney took during the federal government’s crisis over raising the statutory limit on federal borrowing, in which he said the debt ceiling should only be increased if federal spending was first cut, then capped, and a balanced budget amendment was passed by Congress. The Republican presidential front-runner ruled out tax increases, as Mr. Obama pressed for “loophole closures” of his own.

The presentation also laid out other steps that restrained spending increases, although spending was projected to rise above fiscal 2004 levels by 5.8% in fiscal 2005, according to the presentation.

Most people's first reaction to this is as a political story -- it's another way in which Romney has run afoul of party orthodoxy. But the policy implications are interesting as well. Romney was a good governor. He was a good governor because he did things that the national Republican Party won't let you do -- provide universal health coverage, and conduct balanced fiscal policy. Now, frequently governors will run for national office by boasting of accomplishments that are orthogonal to the national policy debate. Here Romney has done things that are completely diametrical to party orthodoxy. It makes it pretty hard to figure out how he would like to govern if not for the political constraints he'd face, let alone how he actually would govern given his need to hold together his base. I still think Republicans won't give him the chance to win the nomination.

Don't Fear The Supercommittee

I'm seeing a lot of liberal concern that Democrats on the supercommittee are going to get rolled. And it's true that Democrats have appointed Max "If I wait another six months, will you consider a health care deal?" Baucus while Republicans are appointing people with nicknames like "The Slasher."

Still, I think the main asymmetry here lies in the nature of the demands of the two sides -- Democrats insist on both revenue and spending cuts, Republicans on just spending cuts -- rather than their willingness to compromise the demands themselves. Jonathan Bernstein writes:

It's absolutely true, as Greg says, that Harry Reid and other Democrats talk about how much they want to reach a deal and how flexible they intend to be, while Republicans have been spending the last week groveling to Grover Norquist and Rush Limbaugh. My guess is that it's easy to overstate how important that rhetoric is. Basically, at this point both sides are attempting to appeal to the constituencies they care about not in terms of substantive policy, but in terms of their attitude towards politics. But those constituencies also do have substantive concerns, and I'd expect those to trump attitudes about process down the line (although expect public statements to remain framed by those process concerns). In other words, it makes perfect sense that Democrats express eagerness to make a deal now, and then after there's no deal they will express their frustration that Republicans weren't willing to meet them halfway. But that doesn't mean that Democrats will in fact be any less vigilant in fighting for their preferences than the Republicans will be in fighting for theirs.

I think the main thing to understand here is that the supercommittee just does not need to strike a bargain. The automatic cuts that will occur if Congress doesn't cut the deficit are designed to threaten both parties. But, rather than force the parties to make a deal to cut the deficit, it could just as easily force the parties to make a deal to cancel out the cuts after they fail to make a deal. Remember, the cuts don't take effect until 2013. i don't see how that threat could force Democrats to accept cuts to entitlement programs without higher revenue.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers