Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 14

August 5, 2011

A Useful Compilation Of Republican Economic Thinking

The Jennifer Rubin post I mentioned earlier this morning also usefully reveals the paucity of Republican economic analysis. The party's agenda largely consists of maintaining current tax rates and deepening fiscal contraction. Rubin compiles quotes from various Republicans. Only Michelle Bachmann offers any prescriptive element. Let's look at her soundbites one by one:

When I asked economist Douglas Holtz-Eakin of the American Action Forum about his assessment of our economic woes, he pointed to investors moving back to Treasurys (and out of the stock market) with the U.S. debt ceiling crisis resolved, the European debt crisis growing and the realization that “Obama has no strategy for growth and jobs.” He says, “Bottom line — the absence of good news leads to a cumulative lack of confidence.”

Analysis: Obama has no strategy, but no counter-strategy offered.

The Bachmann campaign put out a statement that reads:

“Unfortunately, Americans continue to feel the effects of President Obama’s failed economic policies as they see their life savings dwindle in the falling stock market, and watch the economy and unemployment continue in a no-growth spiral. Clearly, the markets are reacting negatively to giving President Obama a $2.4 trillion blank check, as well as the President’s promise to increase taxes on the American people and job creators. He has no intention of cutting spending. What the markets wanted, and what the country needs, is a fundamental restructuring in the way Washington spends taxpayers dollars that reins in unprecedented spending, gets our debt under control, and encourages pro-growth economic policies. Politicians can say what they want to say, but you can’t fool the markets.”

Analysis: The markets wished Congress refused to raise the debt ceiling, and have plunged on the sudden realization that we're scheduled under current law to revert to Clinton-era tax rates in 2013. O-oo-kay.

Tim Miller from the Jon Huntsman camp e-mailed me, “On the most important issue facing our country — the economy and jobs — the President has failed. He’s had 2.5 years to inject more confidence into the economy, create an environment for growth, pass free trade agreements, and he’s done none of that. To get the economy going again, the country needs new leadership, someone with a track record of creating an environment that allows entrepreneurs to create needed jobs.”

It's Obama's fault, but no analysis of what he's done wrong except fail to extend free trade agreements, which he in fact favors.

Andrea Saul,the spokeswoman for Mitt Romney, who has made jobs the centerpiece of his campaign, had this take: “In the past, President Obama has cited gains in the stock market as an indicator of a recovering economy and a healthy financial system. Now that the Dow is falling, he needs to explain what that says about his failed leadership and the state of the economy.”

Another 100% blame Obama, 0% argue what he's done wrong or offer an alternative.

How To Make Republicans Care About Stimulus

Adam Serwer and Kevin Drum write today about the paradox of republicans forcing contractionary fiscal policy, and then reaping the political benefit of the resulting contraction. This is, indeed, a maddeningly unjust outcome. But it also suggests one strange corollary: The only way to get a really big new stimulus would be to elect a mainstream Republican president (Say, Mitt Romney or Tim Pawlenty) in 2012.

Here are my premises. Most Republican embrace of contractionary fiscal policy reflects conscious or unconscious partisanship rather than a sudden conversion to Austrian economics. You do have some genuine crazies in the House, but Republicans like Mitch McConnell are mainly driven by a desire to win power and please business. So, if the 2012 elections flip the House to the Democrats and put a Republican in the White House, that president will quickly grasp the policy and political imperative of stimulating the economy. The Democratic House would support it for policy reasons, and the GOP senate would support it for political reasons.

Now, personally, I'm not willing to accept the long-term policy changes that a Republican presidency would entail in order to get the short-term benefits of higher stimulus. But it is worth considering. The clear implication of the partisanship explanation of Republican behavior is that we need to flip the Republican Party's political incentive structure vis a vis stimulus.

The Morality Of Political Hostage Taking, Cont'd

[image error]

Eugene Volokh jumps into the debate over the morality of debt ceiling hostage-taking, defending the Republicans:

Yet those who opposed the conservative demands for spending cuts as a condition of raising the debt limit obviously didn’t just want to be left alone. They wanted the conservative legislators to cast their votes to authorize a debt limit increase. They wanted taxpayers to be on the hook for repaying an increased national debt. They wanted people’s cooperation, and were then complaining about the conditions that the people imposed for such cooperation.

In some respects, this is like a businessman who complains about “extortion” when union members threaten a legal strike (carried out through legal means). One can certainly understand the businessman’s feeling put upon: He may be threatened with financial ruin, much as he is threatened with financial ruin if an extortionist threatens to burn down his property (or if a corrupt politician threatens to shut down the business if a bribe isn’t paid).

But the businessman doesn’t just want the supposed “extortionists” to stay out of his life. He wants their cooperation: He wants them to keep working for him (or he may want their sympathizers to keep buying his products, for instance when he’s objecting to a union-organized consumer boycott). The union members are saying: If you want us to keep spending our time and effort on working for you, you need to give us enough to make us agree to work for you.

To be sure, the union members may be in a position where the businessman must accede, because he needs them to cooperate. But since they have no legal obligation to cooperate, he needs to get them to agree. And to label this threat of noncooperation in order to get something valuable in return “extortion” or “hostage-taking” isn’t just be normal rhetorical license — it would fundamentally miss the key moral distinctions.

Bad analogy. Union members who strike are hurting the parties to the transaction. Failing the debt ceiling creates little harm to members of Congress themselves, and enormous harm to innocent parties.

We have a mechanism for members of Congress to not cooperate in a higher national debt. It's to refuse to sign a budget in which outlays exceed revenue.

Should Obama Have Demanded A Big New Stimulus? Eh.

I completely agree with the economic case on the need for greater stimulus. I sort-of agree with the political argument that President Obama blew it by not passing a larger stimulus then the one he did. (If he proposed, say, a $2 trillion stimulus, maybe the moderates would have considered the moderate thing to do knocking it down to $1.5 trillion. On the other hand, maybe they would recoiled and have killed it altogether.)

The part of the argument that I don't agree with is the notion that Obama should be demanding new stimulus now, or should have been demanding it for the last year. Paul Krugman's column today encapsulates what I find unconvincing:

The Fed needs to stop making excuses, while the president needs to come up with real job-creation proposals. And if Republicans block those proposals, he needs to make a Harry Truman-style campaign against the do-nothing G.O.P.

This might or might not work. But we already know what isn’t working: the economic policy of the past two years — and the millions of Americans who should have jobs, but don’t.

This is kind of a throwaway at the end of the column, but it echoes a fairly common argument, which was also made in a recent TNR editorial. The problem is that it begins as a policy argument (we need more stimulus) which is true. But then it quickly acknowledges that Congress won't pass more stimulus, so it switches to a political argument (Obama should attack Congress for opposing more stimulus.)

So now we're not really arguing about what to do about the economy. We're arguing about political messaging. But it's pretty clear that the concept of economic stimulus is unpopular. People think it's a big waste of money. So what is the value of devoting a lot of presidential energy to an unpopular message? There's no real evidence that sustained presidential rhetoric can change people's minds on issues where they've formed an opinion.

Obama's approach to this problem is to try to break up "stimulus" into individual measures that command public support, like a payroll tax cut. Krugman argues that he's

proposing some minor measures that would be more symbolic than substantive. And, at this point, that kind of proposal would just make President Obama look ridiculous.

A large new stimulus is also symbolic, since it has no chance of passing. Even a small stimulus probably won't pass, but it's imaginable. Even if you assume that bite-sized measures have zero chance, that means you're just choosing between different symbolic measures. What's the point of advocating for an unpopular symbolic measure instead of a popular one?

I'm not saying the current course is good. When the only thing you can do about the economy is both unpopular and D.O.A. in Congress, there just aren't a lot of tools available.

How Obama's Policies Traveled From The Future To Cause The Recession

Yesterday, David Frum posed a question to conservatives:

My conservative friends argue that the policies of Barack Obama are responsible for the horrifying length and depth of the economic crisis.

Question: Which policies?

Obama’s only tax increases – those contained in the Affordable Care Act – do not go into effect until 2014. Personal income tax rates and corporate tax rates are no higher today than they have been for the past decade. The payroll tax has actually been cut by 2 points. Total federal tax collections have dropped by 4 points of GDP since 2007, from 18+% to 14+%, the lowest rate since the Truman administration. ...

We have not seen a major surge in federal regulation, at least by the usual rough metrics: the page count of the Federal Register has risen by less than 5% since George W. Bush’s last year in office. Trade remains as free as it was a decade ago.

While the Affordable Care Act itself will eventually have major economic consequences, most of its provisions remain only impending.

Energy prices have surged, but that’s hardly a response to administration policies.

And here we have Washington Post conservative blogger Jennifer Rubin offering a perfect sample of the thinking he describes. In short, yes, her theory is that the future expiration of the Bush tax cuts and the not-yet-implemented Affordable Care Act have caused a worldwide economic crisis:

Obama’s entirely false assessment of the economy had real policy implications. Recall that Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner a year ago told us that the economy could “withstand” tax hikes. And so he doggedly urged tax increases, rather than cuts. And as we saw in Obama’s Rose Garden speech this week, his anemic program of items like an infrastructure bank and patent reform shows no sign that he connects his uber-regulatory schemes, Obamcare and the threat of ever-higher taxes to the faltering economy.

Rubin is arguing that Obama's overly rosy view had "consequences," as reflected in Geithner's declaration that the economy could withstand tax hikes. He was arguing that the economy could withstand tax hikes on income over $250,000, but the administration gave in on that demand and extended all those tax cuts. So that's her key causal factor -- the administration arguing for a tax increase that it did not actually implement.

August 4, 2011

&c

-- Felix Salmon responds to today’s huge dip in the Dow.

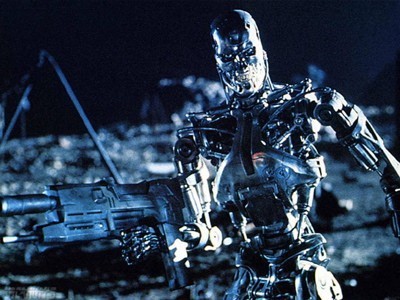

-- In which Tim Geithner stars in the sequel to The Exterminating Angel.

-- Jacob Weisberg says politics is “broken in every possible way.”

-- The GOP presidential field: neoconservatism or Sharia panic.

The Morality Of Political Hostage Taking

objects to Democrats referring to Republican debt ceiling tactics as terrorism:

The political tactics that seems to each of us most dangerous and irresponsible inevitably reflect deeper assumptions about the way economies and governments do and ought to work. Of course, not every set of assumptions about market and state are equally reasonable. But we should not be too hasty to ascribe criminal, enemy-of-the-state status to those who see things differently.

His colleague points out that Mitch McConnell himself compared the tactic to hostage-taking, and proceeds to argue:

There is some interesting thinking to be done on how a hostage that isn't worth shooting can possibly be a hostage that's worth ransoming. I think it comes down to social conventions and where they place the burden of expectation. Any hostage-taker always tries to create a system of expectations in which the party asked to pay the ransom is responsible for whatever happens. Forcing Democrats to pay the ransom once helps to institutionalise this expectation. After all, how could Republicans be expected to know that Democrats wouldn't pay the ransom a second time? But everyone should then understand why many Democrats now feel that the first order of business, before anything else can be done, is to dispel the impression that you can hold the American economy to ransom for whatever political priority you may deem most important, and Democrats will eventually cave. Democrats will not be able to achieve any of their priorities until they re-establish the understanding that when Republicans make threats, they, not Democrats, are responsible if the threats are carried out.

That's a great point. I also think that Wilkinson is missing the more fundamental distinction here. It's common for parties to vote for legislation that the other party thinks will have horrific effects. Democrats think the Paul Ryan budget would lead to mass suffering. Republicans said the same about the 1993 Clinton tax hikes. We should learn to accept the fact, as Wilkinson says, that parties will advance policies with strongly different assumptions about the market and the state.

The difference is that the Republicans this time threatened to carry out a policy that they themselves believed would have horrific effects. I can't think of any precedent for that in national politics. It's also behavior that seems to differ in degree but not in kind from actual hostage taking. A hostage taker does not want to murder an innocent person, but he is willing to risk that outcome, and seeks to leverage his willingness to risk that outcome in order to obtain concessions. Now, one distinction is that your typical hostage taker wants money, whereas the Republicans wanted policy concessions that, as Wilkinson notes, they genuinely believe will improve the world.

But what about politically motivated hostage takers? They exist, too. Is there any important moral difference between threatening to kill somebody in order to achieve a policy goal and threatening to deliberately unleash global economic chaos in order to achieve a policy goal? I can't see any.

Pawlenty's Galileo Moment

We've come to the point where obtaining the Republican presidential nomination requires one to submit a Galileoesque recantation of one's previous endorsement of climate science. Via Darren Samuelsohn, here' Tim Pawlenty in an interview with the Miami Herald:

Q: You also no longer favor a cap-and-trade global-warming solution, right?

Pawlenty: “Like most of the major candidates on the Republican side to varying degrees, everybody studied it, looked at it. We did the same. But I concluded, in the end some years ago, that it was a bad idea… We never actually implemented it. I concluded ultimately it was a bad idea. It would be harmful to the economy. The science was I think based on unreliable conclusions.”

Q: Do you think there’s man-made climate change?

Pawlenty: “Well, there’s definitely climate change. The more interesting question is how much is a result of natural causes and how much, if any, is attributable to human behavior. And that’s what the scientific dispute is about.”

Q: Were do you fall on the spectrum?

Pawlenty: “It’s something we have to look to the science on. The weight of the evidence is that most of it, maybe all of it, is because of natural causes. But to the extent there is some element of human behavior causing some of it – that’s what the scientific debate is about. That’s why we’ve seen all this back and forth between some of those prominent scientists in the world arguing about that very point.”

Q: There is a strong case for man-made climate change, according to a University of Miami climate researcher I’ve spoken to. You don’t agree with him?

Pawlenty: “There’s lots of layers to it. But at least as to any potential man-made contribution to it, it’s fair to say the science is in dispute. There’s a lot of people who say the majority of the scientists think this way. And there’s a minority that way. And you count the number of scientists versus the quality of scientists and the like. But I think it’s fair to say that, as to whether and how much – if any – is attributable to human behavior, there’s dispute and controversy over it.

He is such a soulless hack. But this is the state of the Republican Party now. No doubt Pawlenty tells himself he must pretend not to believe in climate science or else the nomination may go to somebody who genuinely disbelieves climate science.

How The Supercommittee Will Succeed By Failing

The battles lines are forming over the supercommittee, tasked with finding $1.8 trillion in deficit reduction or triggering huge cuts to defense and health care. The divide isn't exactly that Republicans won't agree to higher revenue and Democrats won't agree to cut entitlements. It's that Democrats will agree to cut entitlements only in exchange for higher revenue, and Republicans won't agree to higher revenue no matter what. Liberals are disappointed in the refusal of Democratic leaders to draw clear lines in the sand, but I don't see any scenario in which Democrats cross the line Obama refused to cross when negotiating with Republicans: either entitlements for taxes, or nothing for nothing.

So, if Republicans refuse to take the deal, what happens next? Well, the Obama administration hopes that the trigger forces them to act. Republicans can't abide the severe defense cuts that the trigger would provoke. It's possibly this threat will force Republicans to bargain. But the more likely scenario is that they let the trigger go off, and then quickly undo it. National Review's editorial, I think points the way for the GOP strategy:

Republicans should make public a serious first step toward entitlement reform without blinking on tax increases.

But the supercommittee is almost guaranteed to fail in agreeing to any large deficit reduction, for the same reasons that months of wrangling did not lead to a grand bargain: The parties’ positions are too far apart. We should assume, then, that the automatic cuts are likely to become law.

That does not mean that they will happen. Future Congresses will have their say, and it is hard to believe that they will accept a ten-year budget path set now. This bill will, however, establish the default settings for federal spending. Liberals who want more domestic discretionary spending will have to get legislation through both chambers of Congress and past the president’s desk. So too for conservatives who want to restore defense spending.

If the automatic cuts become law, restoring defense spending is exactly what we hope Republicans try to do.

That's the answer, I think. Now, you could say that this would make the supercommittee a failure. From the perspective of deficit reduction, you'd be correct. But the supercommittee wasn't really created in order to reduce the deficit. It was created in order to lift the debt ceiling.

Republicans needed a way to approve the debt ceiling without backing down from their avowed goal of reducing the deficit by a dollar for every dollar they hiked the debt ceiling. The supercommittee was supposed to lock in the lion's share of that deficit reduction. Now, suppose the parties can't agree on a fiscal adjustment -- that is, Democrats insist on a balanced deal and Republicans insist on a cuts-only deal. Then we trigger some painful cuts neither party wants, and Congress then goes ahead and cancels them out. End result: we increased the debt ceiling by $2.4 trillion, and only cut half as much from the budget. By the time this is clear, conservatives have long since turned their attention to other matters, and Boehner gets to keep his Speakership.

Meanwhile the ratings agencies think we've taken a step toward constraining the long-term deficit, and we actually impose a solution in 2013 when the Bush tax cuts face renewal, which also happens to be the sensible time to do the fiscal adjustment. That sounds like a win to me.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

Republicans: We're In Control, Blame Obama For The Results

Jim Vandehei and Mike Allen have a big story story about the political headwinds facing President Obama's reelection efforts, but I think the crux of the dilemma is really identified better by Ian Swanson:

Congressional Republicans are running economic policy these days, but President Obama owns the results.

That puts the president in a bind, as the GOP proposals he signed into law are arguably slowing economic growth.

To put this a bit more precisely, the debate over the long-term shape of the government remains wide open, but Republicans have seized control of short-term fiscal policy. They have been arguing for two years that, contrary to the beliefs of most of the economics profession and the entirety of the macroeconomic forecasting field, fiscal stimulus has harmed rather than helped the economy. Their prognosis is immediate fiscal retrenchment. Conservatives have argued that halting the momentum of Obama's domestic agenda and withdrawing stimulus will boost growth and create jobs.

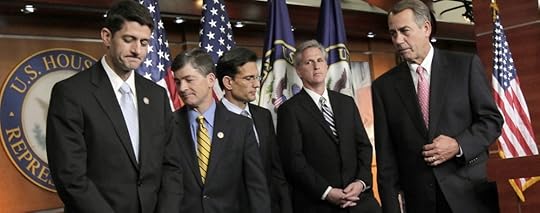

The Republican message is that they are implementing this agenda. Paul Ryan wrote the other day, "Republicans won the policy debate by securing the first of many spending restraints we need to avoid a debt-driven economic calamity." In today's Wall Street Journal, three more Republicans echo the we're-in-control-now message. Karl Rove:

House Republicans adroitly shifted the debate's focus from how much to raise the debt ceiling to how much should spending be cut. They achieved this even while the other two centers of power in any legislative struggle—the Senate and the White House—remained in Democratic hands.

In doing so, Republicans achieved roughly two-thirds of the spending cuts sought in the budget the House passed in April, cuts which would have gone nowhere in the Senate without the debt-ceiling battle.

Congress has traditionally been dominated by the impulse to spend more and more of the public's money. In 2011, and especially in the Republican-controlled House, that has been replaced by a culture of spending cuts. ...

"We're on the offensive right now," says Rep. Steve Womack of Arkansas, one of the 87 Republican freshmen. "We're winning. We've got a great message."

But will the new culture of spending cuts endure? "We've got this moment right now," says Rep. Paul Ryan, chairman of the House Budget Committee.

Now the progressives are saying their president blinked this week. What broke Barack Obama's will to win "revenue increases" out of the debt negotiations were last week's nightmare-on-Main Street GDP numbers—1.3% growth in the second quarter and the first quarter revised downward to 0.4%. Even Keynes would have blinked.

Obviously, we have not implemented the right-wing prescription for growth in full. But, as all these conservatives acknowledge, we are now playing on their side of the field. The Bush tax cuts remain fully in place. The stimulus is almost completely exhausted, and the government is beginning to withdraw its fiscal support.

How is the policy working out? Should conservatives expect growth to begin accelerating? I see no sign that they actually believe their newfound control over short-term policy has paid any dividends or will pay any dividends. Where are the conservatives declaring that the Keynesian economic models are all wrong, that the new contractionary policy will boost economic growth? To the extent that they evince any interest in short-term growth, the right's focus seems entirely concentrated on blaming Obama for the current results.

It seems pretty clear to me that Obama needs to escape this dilemma, and positioning of himself as the sole reasonable man, while necessary, is not sufficient. If Republicans want to boast about taking control of short-term fiscal policy, he needs to convince the public to hold them accountable for the results.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers