Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 11

August 11, 2011

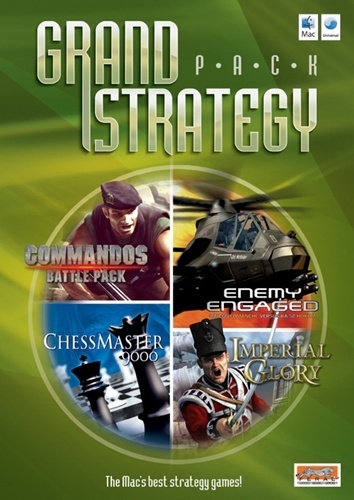

Jeb Bush's Favorite Neoconservative Yale Class

[Guest post by Alex Klein]

[Guest post by Alex Klein]

Yesterday, Jeb Bush and Kevin Warsh chose to lead their Wall Street Journal column with a college shout-out:

"As the economy continues to struggle, we are reminded of a course offered at Yale University titled "Grand Strategy." Drawing on a weighty curriculum of history and philosophy, the course seeks to train future policy makers to tackle the complex challenges of statecraft in a comprehensive, systematic way. Clearly, U.S. economic policy is sorely lacking an effective grand strategy."

As a Yalie, it was comforting to see Warsh and Bush go populist by comparing our economic ills to an undergraduate Ivy League seminar. Jon has already held forth on the sophomoric "grand strategic growth" arguments in the column. Nevertheless, a few aspects of “Studies in Grand Strategy” class itself bear mentioning.

The class is a history seminar that, despite Jeb's reference, has nothing to do with modern economic policy. At Yale, Grand Strategy delivers neoconservative boilerplate through a thinly veiled Straussian lens: for example, Thucydidean “realism” explains Cold War containment; Sun Tzu justifies the preemptive invasion of Iraq. The course has been expanded by and receives millions in funding from conservative financier Roger Hertog, and is spearheaded by two right-wing luminaries. The first is Charles Hill, a Kissinger and Giuliani advisor who left Washington after involvement in the Iran-Contra scandal. The second is John Lewis Gaddis, a brilliant Cold War scholar, but more recently famous for neoconservative cheerleading and vocal endorsements of the Bush Doctrine. Anointed Yalies selected for the program (this guest blogger was sadly wait-listed) learn from a diverse cast of characters: Bush ambassador John Negroponte, Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan, and interventionist Walter Russell Mead. Kissinger occasionally pops by for a chat.

So how do a group of influential and/or wealthy conservatives get a bunch of lefty Yalies to take their Hertog-funded course? Simple. They start a publicity campaign in the Journal. Then they make the class a secretive club, invite students to cocktail hours, give them thousands in grant money, and — perhaps most importantly — hand out special lapel pins that the select few can wear to graduation. (Even the most liberal of undergrads can’t resist a special pin.) Grand Strategy parlays social angst into Straussian indoctrination. This might explain why, of the seven current class members with whom I have spoken about the course, six said they did not enjoy or were offended by its content or instruction.

But all the partisanship and Peggy Noonan aside, are Bush and Warsh right? Could Grand Strategy’s “weighty curriculum of history and philosophy” lift us out of the great recession? Well, here’s some advice from the syllabus authors:

Queen Elizabeth I: “Prosperity provideth, but adversity proveth friends."

Thomas Hobbes: “Money is thrown amongst many, to be enjoyed by them that catch it.”

Machiavelli: “[A] man shall not be deterred from beautifying his possessions from the apprehension that they may be taken from him, or that other refrain from opening a trade through fear of taxes.”

King Philip II: "O how small a portion of earth will hold us when we are dead, who ambitiously seek after the whole world while we are living."

Sun Tzu: “If our soldiers are not overburdened with money, it is not because they have a distaste for riches.”

Thucydides: “A collision at sea will ruin your entire day."

I hope Jeb Bush can explain how this curriculum will help us weigh monetary expansion, infrastructure investment, labor market hysteresis, sovereign illiquidity, and tax incentives. Otherwise he’s definitely not getting a lapel pin.

The Exceptionalism Myth Goes Mainstream

[image error]Republicans have endlessly recirculated the completely misleading talking point that President Obama in 2009 spoke dismissively about American exceptionalism. Washington Post writer Joel Achenbach, in a story about American decline, seems to have read the talking points and repeated the myth without bothering to check the context:

There is also a rash of books from Republican politicians that include attacks on President Obama, accusing him of not believing in “American exceptionalism, ” the idea that the United States is destined, either through constitutional genius, geography, culture, divine providence or some combination thereof, to play a unique and outsized role in human civilization. ...

When asked during a trip abroad in 2009 whether he believed in American exceptionalism, Obama said, “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.” This only drew more criticism from Republicans.

Since then, Obama has been more emphatic in speaking about America’s special role in the world.

This is a smear. In the comments, Obama defended American exceptionalism. The passage quoted by Achenbach, and many Republicans, is the throat-clearing caveat at the beginning of his answer, in which he describes the perspective of his critics before proceeding to disagree with it.

The full remarks:

I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism. I'm enormously proud of my country and its role and history in the world. If you think about the site of this summit and what it means, I don't think America should be embarrassed to see evidence of the sacrifices of our troops, the enormous amount of resources that were put into Europe postwar, and our leadership in crafting an Alliance that ultimately led to the unification of Europe. We should take great pride in that.

And if you think of our current situation, the United States remains the largest economy in the world. We have unmatched military capability. And I think that we have a core set of values that are enshrined in our Constitution, in our body of law, in our democratic practices, in our belief in free speech and equality, that, though imperfect, are exceptional.

Now, the fact that I am very proud of my country and I think that we've got a whole lot to offer the world does not lessen my interest in recognizing the value and wonderful qualities of other countries, or recognizing that we're not always going to be right, or that other people may have good ideas, or that in order for us to work collectively, all parties have to compromise and that includes us.

And so I see no contradiction between believing that America has a continued extraordinary role in leading the world towards peace and prosperity and recognizing that that leadership is incumbent, depends on, our ability to create partnerships because we create partnerships because we can't solve these problems alone.

What you see here is a common Obama rhetorical technique. You could apply the Republican method to nearly any Obama statement, and simply take out of context the part where he describes the opposing view to make it sound as if he believes the opposite of what he actually does. It's a remarkable testament to the power of dogged, repetitive spin that the GOP has managed to get mainstream newspapers to start printing this utterly dishonest interpretation as fact.

Why The Debt Ceiling Crisis Will Happen Again

In a nutshell, because it worked:

Asked about the S&P assessment, 71 percent of Americans called it a fair one. On the blame front, 36 percent say the GOP is culpable for the downgrade, 31 percent blame Obama and his fellow Democrats and 22 percent say it’s both sides equally.

So first the House Republicans held the debt ceiling hostage. It's utterly clear that this which caused S&P to downgrade U.S. debt:

A top official at rating firm Standard & Poor's said Friday the company's decision to downgrade U.S. government debt for the first time in 70 years was due in part to Washington's political paralysis surrounding raising the debt ceiling.

The "conclusion was pretty much motivated by all of the debate about the raising of the debt ceiling," John Chambers, chairman of S&P's sovereign ratings committee, said in an interview. "It involved a level of brinksmanship greater than what we had expected earlier in the year."

The reasons for the downgrade may be shaky, but that's neither here nor there. S&P got freaked out by the hostage drama and decided to downgrade the debt.

But, of course, Republicans aren't going to say that they caused the downgrade. They're going to blame the Democrats, as parties do. And the news media isn't going to take sides in this. We're going to get a shouting match. Indeed, even the liberal Daily Show presented it as a childish shouting match in which neither side was right:

The Daily Show With Jon Stewart

Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c

Rise of the Planet of the AAs

www.thedailyshow.com

Daily Show Full Episodes

Political Humor & Satire Blog

The Daily Show on Facebook

End result: Republicans get concessions, and when the consequences for their decision hurt everyone, the blame is spread equally. If you can use hostage tactics and walk away with both a ransom and everybody blaming you and the ransom-payer equally, why not do it again?

August 10, 2011

&c

-- A short history of iceberg towing schemes.

-- Stimulus from Fannie and Freddy.

-- Al Franken reminds everyone about his proposal to reform the rating agencies.

-- A proposal to eliminate the debt ceiling.

-- It may not be a “grand strategy,” but Daron Acemoglu has some good ideas about how to promote growth

Leave Tim Pawlenty Alooooone!

[image error]

The campaign press seems to have decided that Tim Pawlenty has to win the Iowa straw poll:

As the only mainstream Republican candidate actively competing in the Ames straw poll — thanks to former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney’s decision to skip the event and Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s presidential race slow walk — former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty may never have a better opportunity to break through in the 2012 campaign than this Saturday. ...

With so much firepower behind Pawlenty and so few candidates who have a plausible chance at coming out ahead, Hawkeye State politicos say Ames will be a potentially campaign-changing test of the Minnesotan’s strength.

But if Pawlenty fails to deliver, it will be a grim — and possibly fatal — omen for his underfunded presidential bid.

But... but... why? The Iowa straw poll is not a "test of strength." It's not a test of anything. It's a racket to raise money for the Iowa GOP. It's not democratic. It's not predictive. It's just a sideshow.

The only logic here is the completely self-fulfilling prophesy in which reporters semi-arbitrarily define expectations, even for non-events, and then decide that if a candidate doesn't make it, they can begin hounding him out of the race. They're not thinking of themselves as hounding candidates out of the race. They just decide that the only interesting thing to ask the candidate is some version of the question "When will you quit?" At that point, the candidate's public message becomes "I am going to lose" and defeat becomes inevitable.

Now, something like this dynamic may be necessary during actual primaries and caucuses where delegates are being awarded. But the straw poll is a pure contrivance. Reporters often present it as an event that winnows the field, but the truth is that it's simply an excuse for reporters to winnow the field.

In Defense Of The Recalls

Simon van Zuylen-Wood, in a guest post below, persuasively complicates the liberal narrative about the Wisconsin recall elections by pointing out that the themes of the elections bore little resemblance to the Scott Walker agenda, which motivated the recall. But I think he takes a couple conclusions a bit too far.

Simon van Zuylen-Wood, in a guest post below, persuasively complicates the liberal narrative about the Wisconsin recall elections by pointing out that the themes of the elections bore little resemblance to the Scott Walker agenda, which motivated the recall. But I think he takes a couple conclusions a bit too far.

First, he argues that the recall election "undermined democratic values." I don't really understand what definition of democratic values was undermined. My view is that the recall elections played the role here that proponents of the Senate filibuster once claimed on its behalf -- a rarely-used tool of strong minority dissent. The governor and his majority took office and quickly enacted legal changes they did not campaign on and which were designed in large measure to create a permanent partisan advantage. The Democrats responded by targeting Republican legislators who supported Walker.

Now, it's true that they could only target a handful of them this time around, and it's also true that the campaigns devoted much of their time to other issues. That does not change the fact that the Republican legislators know full well what prompted the recall campaigns. I think the successful recall elections of two state Senators does establish the deterrent power of a recall election. If one goal was to make Wisconsin GOP legislators think twice about supporting an unpopular, highly partisan measure, I think that goal was fulfilled.

Second, Simon concludes, "as Republicans will return to office with at least a 17-16 majority and full control of the general assembly, we’re right back where we started." I don't agree with that, either. Even triggering, let alone winning, a recall election is fairly rare. Winning two is highly unusual. And the Democrats will get another shot next year, when they'll be one seat away from taking over the state Senate rather than three seats away. That's not where we started. It's also a situation where, if Republican legislators are asked to support a relatively extreme and partisan change, they have good reason to seek out a compromise.

The Problem with the Wisconsin Recall Elections

[Guest post by Simon van Zuylen-Wood]

Ta-Nehisi Coates of The Atlantic lauds the Wisconsin recall vote as an exercise in the “ruthless art of democracy.” Closer to toothless, it turns out, as the Democrats fell short of regaining the senate, taking back only two of the six seats they challenged. But regardless of the result, these recall elections haven’t affirmed, but undermined democratic values.

Yesterday’s recalls were supposed to serve as referenda on Scott Walker’s controversial union busting law. Already this year mass protests in Madison, and a coordinated state house walk-out by Democratic legislators didn’t get the job done. So this is three strikes and the Democrats are out of luck. But that doesn’t mean these elections actually had much to do with public opinion of Scott Walker or state-wide Republican policies in general.

Wisconsin—one of 19 states that allows recalls—forbids recalling a governor or state congressman until he or she has been in office for a year. That means neither Scott Walker nor any of the Republican congressmen who swept both chambers of the state house in 2010 can be challenged until 2012. Instead, the Republican senators who faced recall votes were elected in 2008, and are not mirror images of Scott Walker, and merely happen to legislate in districts vulnerable to democratic sway, where enough votes were collected to warrant a challenge.

More importantly, the elections themselves have not been entirely focused on the collective bargaining law, but largely with local squabbles and moral failings. Randy Hopper, one of the two Republicans who lost yesterday, was plagued with questions about an extra-marital affair with a younger woman and just how she got her government job. Conservative religious group Wisconsin Family Action ran an ad attacking Democrat Fred Clark—who lost narrowly—for running a red light and hitting a biker. Another ad played a recording of Clark saying he wanted to ‘smack around’ a woman who wouldn’t vote for him.

Barry Burden, professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told me “the recalls in the end were not so much about Scott Walker…but more about character issues, whether the candidates were good people.” In the biker-ad election, Burden says the attack ads “made the difference” in a 52%-48% victory.

The other big problem with the Wisconsin recall is that because it happened independently of the regular election cycle and drew a lot of national attention, it drove extraordinarily high spending from out of state groups who have no stake in Wisconsin-specific policies. Burden says advocacy groups from out of state ran ads about “veterans and giving tuition breaks to undocumented aliens—things that hadn’t even come up in the legislature this year.” Because of such a big outside spending push, the Democrats’ well-coordinated grassroots campaign ended up being less successful than it might have been in a general, less high-profile election.

There’s no problem with recalling an elected official who’s not doing his job—that was a key charge against the three Wisconsin Democrats up for recall who bolted Madison for Illinois after Walker proposed his bill. But when a recall over a specific issue turns into a battleground for general ideology and partisan bickering, the original conceit of the frustration—Scott Walker’s policies—gets lost in the shuffle. And as Republicans will return to office with at least a 17-16 majority and full control of the general assembly, we’re right back where we started.

The Two Crises And The Triumph Of Magical Thinking

This morning, listening to Diane Rehm, I heard the host ask her guest what President Obama should do to fix the ailing economy. Her guest expert tried to answer, but did not point out that any proposal to address the economy would require passage by the House and Senate. It struck me, again, that our political discourse is consumed by magical thinking.

Two large economic problems have dominated the discourse -- the Great Recession, and the long-term deficit. Now, one problem right off the bat is that much of the discussion weirdly fails to distinguish between these two problems, or treats any solution to one as mutually exclusive with the other, when in fact we can pursue policies that increase the deficit in the short run while decreasing it in the long run.

But the greater impediment is that we're roadblocked by political disagreement between different bodies that must agree in order to produce any action. On the long-run deficit, President Obama favors a fiscal adjustment based on a mix of spending cuts and higher revenue, ideally through a tax reform that produces lower rates. Republicans believe that a fiscal adjustment is only desirable if it consists entirely of spending cuts. On the Great Recession, Obama favors a variety of short-run policies to increase consumer demand, while the Republicans advocate short-term fiscal contraction. They will approve of some policies that increase short-term deficits, but only if those policies contribute permanently reduce effective tax rates for businesses or high-income individuals. Temporary payroll tax cuts no, but maybe yes if they're paired with longer-term reductions in business taxes or extensions of the upper-bracket Bush tax cuts that increase the probability of making those tax cuts permanent.

I personally have some strong opinions on the merits of those positions. But I'm not trying to argue right now about the merits. I'm merely attempting to describe the scope of the disagreement. This disagreement is the key source of gridlock on both issue. You don't have to conclude from this that any progress between now and November 2012 is impossible (though I do personally believe that progress is impossible.) It does not require magical thinking to argue for some innovative strategy to break down or evade the gridlock problem. Yet the vast reams of commentary urging action do not do this. They simply ignore the existing impediments to legislative action.

Part of the issue here is the cult of the presidency. We hold the president responsible for everything that happens. The notion that the president and both houses of Congress must agree on most actions in instinctively dissatisfying. And so we think of every problem as a question of "what should the president do." Layered on top of that is a failure to recognize the deep-seated disagreement between Obama and the Republicans over what we should do.

In the New York Times today, the lead news analysis frames a "A Test for Obama":

The Federal Reserve’s finding on Tuesday that there is little prospect for rapid economic growth over the next two years was the latest in a summer of bad economic news. One administration official called the atmosphere around the president’s economic team “angry and morose.”

There was no word on the mood of the president’s political team, but it was unlikely to be buoyed by the Fed’s assertion that the economy would still be faltering well past Mr. Obama’s second inauguration, should he win another term.

“The problem for Obama is that right now, the United States is either at a precipice or has fallen off it,” said David Rothkopf, a Commerce Department official in the Clinton administration. “If he is true to his commitment to rather be a good one-term president, then this is the character test. In some respects, this is the 3 a.m. phone call.”

Mr. Obama, Mr. Rothkopf argues, has to focus in the next 18 months on getting the economy back on track for the long haul, even if that means pushing for politically unpalatable budget cuts, including real — but hugely unpopular — reductions in Social Security, other entitlement programs and the military.

We have a couple problems here. First, an apparent blurring between the response to the Great Recession and the long-term deficit. And second, a framing of the question of the long-term deficit as an issue of presidential character. Obama has repeatedly endorsed proposals to reduce the long-term deficit via revenue-enhancing tax reform and spending cuts. Republicans oppose these plans. What else should Obama do? Should he agree to cut the deficit by $4 trillion entirely through spending reductions? Find some previously-unused method to persuade Republicans to alter their most sacred principle? Nobody says.

(Incidentally, we have former Clintonite Steve Rothkopf promoting this "3 a.m. phone call" business. The reference, in case you've forgotten, is to Hillary Clinton's claim during the primary that Obama would be unprepared to deal with a sudden foreign policy crisis that occurs at a moment when he can't lean on his advisers. The long-term deficit challenge is actually the precise opposite of this scenario -- a domestic question that unfolds over an excruciatingly long period of time. The closest actual equivalent of the 3 a.m. phone call was the tip about Osama bin Laden.)

Meanwhile, Tom Friedman writes a column today envisioning a world in which both parties come together. Republicans agree to endorse Obama's policy agenda, and Obama agrees to admit that he could have explained his agenda more clearly. I share Friedman's enthusiasm for such an outcome, but I fail to see how this relates to the current impasse.

This is one way in which conservative journalism is actually far more sophisticated than mainstream news journalism. Conservative pundits, while usually slanting their account in highly partisan and often misleading terms, do a fairly good job of grasping and explaining the fact that the two parties fundamentally disagree on the causes of and solutions to the economic crisis and the long-term deficit. In this sense, a Rush Limbaugh listener may well be better informed about the causes of the impasse than listener of NPR or other mainstream organs. The former will have in his mind a wildly slanted version of the basic political landscape, while the latter's head will be filled with magical thinking.

"Mass Resistance" To Education Reform

The Obama administration is pursuing a second round of its education reform agenda. The first round was "Race to the Top," which created a competition among states for extra federal grants that would be won by states with the most impressive reforms. This time around, instead of dollars -- there is no new money to hand out -- the Department of Education is using regulatory relief. The 2001 No Child Left Behind law imposed fairly rigid requirements and standards. Everybody agrees it needs updating, but Congress is too dysfunctional to update it, and has been for several years running. So the Department is offering to waive the standards for states that comply with a second round of reform.

The anti-reform left is, naturally, up in arms. Former conservative education guru turned hard-left reform opponent Diane Ravitch tweets, "What is NOT federal role in education: telling schools what to do, how to reform, punishing them for not agreeing with fed demands." Likewise, Monty Neil, guest posting for the Washington Post's stridently anti-reform blog "The Answer Sheet" urges states to refuse to cooperate:

If they accept the deal, states will lock in ever more counter-productive educational practices based on the misuse of test scores, including linking teacher evaluation to student scores. Those policies could be hard to dislodge should Congress decide not to endorse Duncan’s “Blueprint” when it eventually does reauthorize the federal law. States that refuse to sign on to Duncan’s reform program, however, will be denied waivers, Duncan said, and will then continue to be subject to the continue the NCLB charade of seeking “100% proficiency” of students in reading and math by 2014. Neither choice will help children or schools.

Mass resistance is likely the only course remaining. States should stop imposing additional sanctions on schools, as some states have said they will do. They should simultaneously refuse Duncan’s deal. This would be a good time to call Obama and Duncan's bluff.

This is interesting because much of the debate within liberal circles centers, explicitly or implicitly, on the question of what is the true liberal position. Opponents of reform are advocating a policy of local control, telling Washington to stay out, and urging "mass resistance" at the state level to federal activism. (At least he didn't write "massive resistance.") That doesn't sound like liberalism to me. It sounds like devolving policy to the level of government at which local interest groups (in this case, teachers unions) will exert the most sway, and foreclosing the possibility of using evidence-based methods to drive policy toward more effective practices.

Sorry S&P, America Still Beats the Isle of Man

[Guest post by Alex Klein.]

In the past week, the media and government have justifiably exhausted all possible ways of beating up on S&P. Although juicy, as I’ve argued before, these criticisms are coming a year too late. But for what it’s worth, here’s a list of other investments that S&P consider safer than American debt, and rate AAA:

Finland, The Isle of Man, The Islamic Development Bank, Johnson and Johnson, Microsoft, Exxon Mobil, ADP, and finally… The City Center Trust, a portfolio of 13 full-service hotels.

Even though S&P is getting savaged, the agency has a few unlikely defenders. Ezra Klein, Felix Salmon, and Jonathan Chait claim that, in downgrading US credit, S&P came to the right decision for the wrong reasons — that they stumbled upon an uncomfortable truth, and thus, we shouldn’t shoot the messenger. I disagree. The recent debt ceiling circus does not imply that the US could ever go into default for an extended period of time. The President is right. Warren Buffet is right. And most importantly, even after the downgrade, the market has staked hundreds of billions of dollars on the creditworthiness of the US government. Even on Monday, the Treasury was able to sell $32 billion worth of bonds at a record low interest-rate.

Amid macroeconomic turmoil, we’re seeing a flight to quality to US debt, historically and currently considered the safest and most boring place to invest. And it’s not just the three-year notes. Short-term loans are at bargain-basement interest rates of 0.03 percent, while one, five, ten, and even thirty-year treasury bonds are close to their lowest yields in seven months. If S&P’s downgrade reflected some kind of inconvenient truth about the riskiness of American debt, investors would have picked up on it a long time ago and fled for safer shores. But today, American debt is the safer shore. Even failure to raise the debt ceiling in the future doesn’t mean default. The treasury would cut back on government expenditures, but the bondholders would be fine. If S&P’s downgrade were legitimate, treasury bonds wouldn’t be seeing record high demand.

S&P, Chait/Salmon/Klein, and myself are actually all in agreement on one thing: A radical wing of the Republican party has created and exploited a hostage situation, one that has likely decreased market confidence in the ability of government to stimulate the economy. Here’s where I differ: I don’t think that this political analysis, albeit correct, implies that a hypothetical, extended American insolvency is even a remote possibility. The gridlock could result in some very ugly things, but a bond market default is not one of them.

In fact, a couple weeks ago, S&P itself was on my side. In the midst of the debt crisis, two weeks before the August 2nd deadline, I spoke to both S&P and Moody’s about the threat of default. Nikola Swann, chief S&P sovereign debt analyst, was testy. “It's basically the difficulty the US has, as a country, in making up its mind which is the driver here,” he told me. But he was still adamant that default was a remote possibility. “The likelihood of an actual of default — a nonpayment of market debt — is quite low. Remember that the rating is still AAA.” Back then, CDS spreads — insurance against American default — were implying a 6-in-10,000 chance of American default within the year. I floated Swann this number, and got this response: “That seems within the right ballpark.” S&P was telling me the chances of American default were 0.06% even during the debt crisis. After having heard this from the horse’s mouth, their post-deal downgrade struck me as even more absurd and opportunistic.

We’re all guilty here of using armchair political psychology to entertain hypotheticals: thankfully, when S&P did it, the bond market didn’t listen. But while Salmon, Klein, and Chait are right to point out the shreds of accuracy in S&P’s cobbled-together justification, the agency’s downgrade doesn’t reflect market reality, and doesn’t deserve an endorsement.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers