Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 7

August 18, 2011

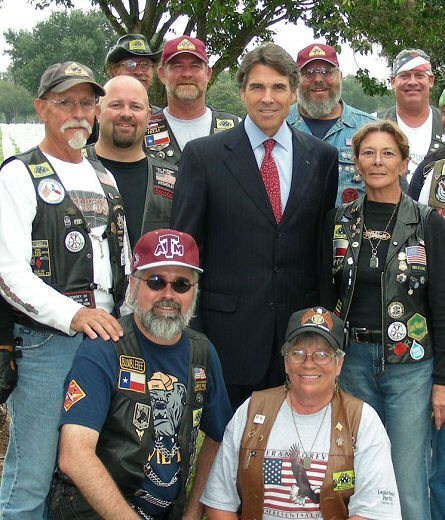

Rick Perry And The Return Of Conservative Identity Politics

If Rick Perry wins the Republican nomination, or even the presidency, one of the less significant but more annoying ramifications will be the return of conservative identity politics. The Bush years saw the full flowering of this branch of right-wingery, which is devoted to exploring and nurturing the cultural grievances endured by white people in the "Heartland" at the hands of cultural elites.

If Rick Perry wins the Republican nomination, or even the presidency, one of the less significant but more annoying ramifications will be the return of conservative identity politics. The Bush years saw the full flowering of this branch of right-wingery, which is devoted to exploring and nurturing the cultural grievances endured by white people in the "Heartland" at the hands of cultural elites.

National Review editor Rich Lowry has a column, pegged to Perry, reviving the trope. It's far from the most extreme sample of conservative identity politics, but it nicely capture the its style:

Texas governor Rick Perry is about to stride purposefully through every cultural tripwire in the country.

He may not become as despised as Sarah Palin, but that’s because he’ll never be a pro-life woman — the accelerant for the conflagration of Palin-hatred. The disdain for Perry won’t burn as hot, but it’ll burn just as true. He’ll become a byword for Red State simplemindedness in the New York Times and an object of derision for self-appointed cultural sophisticates everywhere. ...

Perry will be branded as a backward, dimwitted, heartless neo-Confederate. A walking, talking threat to the separation of church and state who doesn’t realize people like him were supposed to slink away after the Scopes trial nearly 90 years ago.

Much like left-wing identity politics, conservative identity politics has a postmodern approach to objectivity. There is no such thing as truth, only truths from the perspective of a social group. Are figures like Palin and Perry simpleminded? In the world of conservative identity politics, this question can only be answered within the context of liberal elite cultural biases.

I would argue that the perception of Perry as simpleminded stems primarily from the fact that he says a lot of crazy, stupid things, and is only loosely related to his Texas upbringing, Eagle Scout membership, and so on. Lowry's column lavishly and extensively details the cultural signifiers, presenting these as the entire body of relevant information. But, of course, I myself am a coastal liberal elitist, so the mere fact of my objection to conservative identity politics merely serves to further confirm its truth.

The Truman Show

A couple days ago, Norman Ornstein wrote a piece for TNR suggesting that Harry Truman's 1948 campaign offers a historic parallel for President Obama. Truman had seen Republicans sweep to power in the midterm elections two years before, and proceed to advocate a radical anti-government ideology that alienated large swaths of the electorate, allowing Truman to counterpose himself against them. Conservative pundit Michael Barone writes a column objecting to the parallel:

There are in fact major differences between Truman’s standing in 1947–48 and Obama’s standing today. Contrary to Truman’s “do-nothing” characterization of the Republican 80th Congress, it in fact did a lot. It repealed wartime wage and price controls, cut taxes deeply, and passed the Taft-Hartley Act, limiting the powers of labor unions.

None of those actions was reversed by the Democratic Congress elected with Truman in 1948. Many congressional Democrats in those days were anti–New Deal conservatives. Truman won many votes from Democrats still upset about the Civil War. Few such votes will be available to Obama or congressional Democrats in 2012.

In addition, Truman’s victory was brought about by two “F factors” — the farm vote and foreign policy — the first of which scarcely exists today and the second of which seems unlikely to benefit Obama in the same way.

Okay, the first part of Barone's argument consists of insisting that the 80th Congress actually accomplished a lot, unlike the current Congress. In other words, the current Congress is worse than the Congress Truman ran against. It's hard to understand why this point argues against the possibility of using the current Congress as a foil.

The rest of Barone's column represents a failure to grasp the concept of analogy. Barone details differences between Truman and Obama -- Truman had a different voting coalition than Obama, and he benefited from Republican threats to agriculture subsidies:

Today only 2 to 3 percent of Americans live on farms. Farm prices currently are running far ahead of subsidy prices. Obama is not going to be reelected by the farm vote.

True! But the point of Ornstein's analogy was not that Obama would benefit from literally the same voters and literally the same issues as Truman did. Obama will point to different popular programs threatened by the GOP Congress -- Medicare, not farm subsidies. He will have a different voting coalition than Truman -- far fewer Southern whites, far more minorities and college-educated voters.

Indeed, most of Truman's 1948 voting base is now, in fact, dead. I don't really think Ornstein was attempting to argue that Obama would literally do the exact same thing as Truman. I think he was arguing that Obama would do the modern equivalent. That's generally what a historical analogy is used for.

August 17, 2011

&c

-- A good example of why people don't like the Fed.

-- And here are several prominent conservatives who have no nice things to say about Ben Bernanke.

-- If you're looking for a left-wing way to interpret Texas's admittedly impressive job growth, here it is.

-- Rick Perry's New Hampshire debut.

-- One of Bachmann's key Iowa organizers was arrested in Uganda on terrorism charges in 2006.

Paul Ryan On The Impossibility Of A Grand Bargain

Paul Ryan explains why there won't be a Grand Bargain on the deficit:

Paul Ryan explains why there won't be a Grand Bargain on the deficit:

“I don’t think this committee is going to achieve a full fix to our problems, because Democrats have never wanted to put their health care bill on the table,” Representative Paul D. Ryan, a Wisconsin Republican who leads the House Budget Committee and studiously avoided assignment to the new panel, said in a recent interview on “Fox News Sunday.”

Of course, the Affordable Care Act reduces the deficit by a substantial amount over the long term. So why would a refusal to partially or completely repeal that law be the fundamental impediment to a deficit deal -- as opposed to, say, the GOP's theological opposition to higher revenues even in return for a much greater amount of spending cuts?

To understand what Ryan's saying, you have to grasp a couple of his premises. Ryan lives in a world in which the Affordable Care Act dramatically worsens the deficit picture, and the Congressional Budget Office's score of the bill is totally inaccurate. Ryan's beliefs about this are based on a bunch of demonstrable fallacies, but that of course is part of the problem -- the CBO is going to score any deficit-reducing bill, which means it will be scored by CBO-math instead of by Ryan-math.

Now, it's true that by CBO math you could save money by keeping the budget savings in the Affordable Care Act and simply eliminating all the coverage expansions. That's what Ryan's budget does. And this, in turn, highlights another unbridgeable gap between the two parties. Democrats and Republicans both believe that the long-term deficit needs to come down. Democrats think this needs to be done in such a way as to impose greater sacrifice on those most able to bear it, while sparing the most vulnerable. Ryan and (apparently) most Republicans believe the exact opposite. His plan entails throwing thirty million Americans off of health care insurance and concentrating two-thirds of his budget cuts on the small slice of federal spending that benefits the poor.

All this is to say that Ryan defines "our problems" in completely different terms than Democrats do. Ryan sees the problem as a government that takes too much from the rich and gives too much to the poor and/or the sick. A bipartisan deficit panel is never going to "solve" that problem.

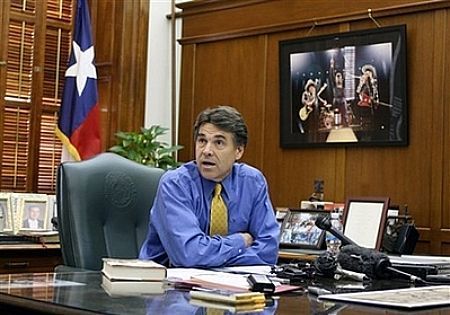

The Reality And The Myth Of The Texas Miracle

The initial liberal reaction to Rick Perry's "Texas miracle" has been to dispute that any such miracle has occurred. The instinct here was understandable -- for reasons I'll explain below, Perry's story doesn't make a lot of sense -- but it doesn't seem to be correct. Matthias Shapiro persuasively argues, in a lengthy blog post that's hard to summarize, that Texas has indeed enjoyed very impressive growth under Perry. Dean Baker, after initially reaching the opposite conclusion due to spreadsheet error, reaches the same conclusion.

So Texas has done great under Perry. What does this mean? Perry's explanation is that he fostered a pro-business environment by keeping taxes and regulation low and luring employers from other states. But that story does not really make sense even on its own terms. First, Perry's right-wing policy cocktail closely resembles conservative governance in other Republican-run states. And yet we don't see a general trend of extraordinary job growth in states with low taxes, pro-business regulation, and so on.

Second, even if it were true that Texas thrived because Perry poached business from California, this hardly provides us with a blueprint for national policy. Begger-thy-neighbor policies aren't a formula for national success. There are only so many jobs we could poach from Canada or Mexico. It's always going to be easier to get a business to move across state lines than international lines.

The best explanations for Texas's success, other than its proximity to Mexico and resulting high levels of immigration, is genuinely good housing policies. Texas had tight lending requirements that prevented the inflation of a housing bubble, and it maintains loose zoning rules that allow for lots of cheap housing. In a housing-based economic crisis, this goes a long way. It doesn't, however, especially recommend Perry's national economic agenda.

Forget Education Funding, Rick Perry Lets Texans Wrestle Catfish with their Bare Hands!

The chattering class in D.C. has gotten pretty worked up over Governor Rick Perry's presidential candidacy. And, among other things, they've been asking whether America is ready to install another Texas Governor at the helm.

If you needed evidence that Texas is unlike any other state in the union, take a look at this summary from The Star-Telegram of the bills that became law in Texas this year, many of them strange, and many of them signed by Governor Perry. The one that stood out the most to me—aside from a new law permitting hunters to shoot at "feral hogs from helicopters"—is the new law signed by Governor Perry that will allow fisherman to catch catfish with their bare hands, a practice called "noodling." The Wall Street Journal did a great story about noodling back in May before it became law and described the noodling process. First, the fisherman puts his hands under water and waits for the fish to bite him, and when it does, he shoves both of his arms in the fish's mouth or gills to grab hold of it, pulls the fish close to his body, and then wraps his legs around its tail to stop it from wriggling. Catfish are enormous, so the process is actually pretty terrifying. Here is a bit from the story, which is worth a read:

So Mr. Knowlton, a 30-year-old-private citizen, oilman and outdoor enthusiast here, is pushing a bill in the state Legislature to legalize hand fishing, also known as noodling, grabbing or hogging. Noodlers go into the water, then reach into holes, hollow tree trunks, and other underwater nooks to find the fish.

Nothing beats "the heebie-jeebies you get underwater, in the dark, with this little sea monster biting you," he says. He recalls that his arm looked like "the first stage of a chili recipe" after his first noodling experience about 15 years ago. Catfish are equipped with bands of small but very abrasive teeth.

So, why did Texas ban noodling in the first place? According to the Journal story, it's because "officials didn't consider it a "sporting way" of taking fish when they sat down to write the rules decades ago." Essentially, opponents of the practice find it inhumane and less sportsmanlike to grab a fish out of the water with one's own hands instead of trying to catch it with a rod and bait. More likely, the anti-noodlers simply don't have the courage it takes to wrestle with a catfish. In a way, the law represents the fierce libertarian streak currently running through Republican politics. The bill's author, Texas state senator Bob Deuell, captured this sentiment in The Texas Tribune when he said: "I personally don't noodle, but I would defend to the death your right to do so."

Goldbuggery And Partisanship

[image error]

Jared Bernstein argues that Rick Perry's violent tight money views reflect a class-based view of inflation:

[W]hat’s really behind conservatives view on this issue is that the wealthy get hurt a lot more by inflation than by unemployment, and visa-versa for the middle class. ...

Why just last night, I was on the Kudlow show arguing against someone who wanted us back on a the gold standard (!!), the natural conclusion of sentiments like Gov Perry’s, and a fine way to cut the Fed off at the knees and ensure deflation at a time like this.

It's clearly true that the very differing affect of inflation on rich rentiers versus wage earners plays a huge role in the historic association between tight money views and right-wing politics. But Bernstein is overrating the role of ideology and underrating the role of partisanship. In 2001, when the economy faced a far milder downturn under a Republican president, Republicans crusaded for looser money.

If you want to grasp Perry's mentality, read his full statement and focus on the parts about politics:

“If this guy prints more money between now and the election, I don’t know what y’all would do to him in Iowa, but we would treat him pretty ugly down in Texas. Printing more money to play politics at this particular time in American history is almost treacherous, or treasonous, in my opinion.”

Perry is viewing this through a political lens. Monetary stimulus reduces unemployment and boosts President Obama's reelection prospects. I doubt Perry is consciously embracing an economic doctrine that he believes will harm the economy. But the partisan impulse is clearly driving his thinking.

Few people have well-defined views on issues like monetary policy. There's always some long-term cost associated with loose money. However tiny or remote the threat of inflation may be, it theoretically exists. When faced with the obvious reality that boosting growth will harm your party, it's very easy to persuade yourself that the long-term costs of inflation are actually large.

The GOP's embrace of loose money in 2001 is one way to test this hypothesis. Another would be to observe their behavior if they win the White House. I predict that, if they do, the party's brief infatuation with goldbuggery will fade away quickly.

Impeachment Watch

What could you impeach Obama over? That's the wrong question. Herman Cain asks, What couldn't you impeach him over?

What could you impeach Obama over? That's the wrong question. Herman Cain asks, What couldn't you impeach him over?

"That’s a great question and it is a great — it would be a great thing to do but because the Senate is controlled by Democrats we would never be able to get the Senate first to take up that action, because they simply don’t care what the American public thinks. They would protect him and they wouldn’t even bring it up," Cain said, citing the administration's position on the Defense of Marriage Act as an impeachable offense.

More from his answer: "So the main stumbling block in terms of getting him impeached on a whole list of things such as trying to pass a health care mandate which is unconstitutional, ordering the Department of Justice to not enforce the Defense of Marriage Act — that’s an impeachable offense right there. The president is supposed to uphold the laws of this nation … and to tell the Department of Justice not to uphold the Defense of Marriage Act is a breach of his oath. … There are a number of things where a case could be made in order to impeach him, but because Republicans do not control the United States Senate, they would never allow it to get off the ground."

A prospective second-term impeachment would probably have to seize on a fresh outrage, not a leftover first term issue. But it's not hard to come up with something that conservative activists could be persuaded constitutes an impeachable offense. Cain cites only the practical barrier of Democrats controlling the Senate. That might not be an issue in a second Obama term.

Zinging Warren Buffett

Warren Buffet's New York Times op-ed arguing that the rich are undertaxed provoked the conservative auto-response to any argument by a rich person that the rich are undertaxed -- they should write a check to the Treasury. Michele Bachmann:

I have a suggestion. Mr. Buffett, write a big check today," said Bachmann. "There’s nothing you have to wait for. As a matter of fact the president has redefined millionaires and billionaires as any company that makes over $200,000 a year. That’s his definition of a millionaire and billionaire. So perhaps Mr. Buffett would like to give away his entire fortune above $200,000. That’s what you want to do? Have at it. Give it to the federal government. But don’t ask the rest of us to have our taxes increased because you want to have a soundbyte.

The Wall Street Journal editorial page:

If he's worried about being undertaxed, we'd suggest he simply write a big check to Uncle Sam and go back to his day job of picking investments.

Obviously this fails to grasp the fundamental collective action problem that's the entire basis for taxation. You obviously can't fund the government on the basis of voluntary donations. Buffett and other wealthy people who favor higher taxes on the rich don't just believe they should pay more taxes. They believe the government needs more revenue. It's amazing how many conservatives continue to think this just-pay-more response constitutes some kind of slam dunk rebuttal. Plus, of course, if a non-rich person proposes raising taxes on the rich, then it's "envy" and "class warfare." So, really, nobody has any business ever arguing that the rich should pay higher taxes.

Perhaps the most interesting point in the Journal's editorial refudiating Buffett was this bit of sociological analysis:

Barney Kilgore, the man who made the Wall Street Journal into a national publication, was once asked why so many rich people favored higher taxes. That's easy, he replied. They already have their money.

I think there's a lot of truth to that. But does the Journal realize that this observation dynamites the entire intellectual rationale for lower taxes on the rich? Kilgore's observation suggests that the very rich have obtained sufficient material comfort that they are motivated by things other than material gain -- the desire to build or invent or out-compete others. They are motivated, in other words, by non-financial goals. That means that raising their tax rate would not dampen their work incentive. I am waiting for the Journal to apply this insight toward its model of the effect of marginal tax rates on the rich... never.

August 16, 2011

The State Of The GOP Race

Ross Douthat asks why I've been mocking both the possibility that Mitt Romney might win the Republican nomination and the conservative attempt to draft alternative candidates into the race:

a question for writers like Chait and Larison, who have made sport of both Romney himself and of the conservative hope that someone else will emerge to take his place. As disinterested observers of the G.O.P. and as patriotic Americans who presumably want the best for their country regardless of which party holds the White House, whom do they think Republicans should want to join the race instead?

This seems like a good time to reset my view of the GOP race, but I'll start by answering Douthat. Answer: I don't think Republicans should want an alternative to Romney. They should want Romney. They should want a president who favors evidence-based technocratic solutions that promote general prosperity. But since most Republicans don't want those things, I don't think they'll nominate Romney.

If you take as a given that Republicans want to a candidate who best combines electability vis a vis President Obama with a genuine commitment to conservative movement principle, then they should have wanted Tim Pawlenty. Now that Pawlenty is out, and if we stipulate that Romney's shameful history of technocratic success renders him unacceptable, then they should draft a politician with some skill as a communicator and/or reaching out to non-base voters. I'd go with Marco Rubio -- make a dent in the Latino vote and you make Obama's reelection very tough -- or Paul Ryan.

Ryan is sort of a tricky case. He has huge positives and huge negatives. His economic plan is very, very unpopular, and likely to become all the more so if the presidential race focuses on its highly unpopular details. On the other hand, he's extremely good at presenting himself, dishonestly, as a compulsively honest, non-ideological budget fix-it man, and getting the political news media to act as his press secretary.

Ryan's potential candidacy is worth delving into as a sign of the state of the GOP field. Undecided presidential candidates answering questions about whether they will run speak in a language of their own, one that bears only a passing relationship to standard English. If you asked your friend if he wants to go see "Green Lantern" with you Friday night, and he replied, "No, my wife and I have theater tickets that night, and I hate Superhero movies anyway," you'd interpret that as a clear no. If a politicians gave the equivalent answer to the will-you-run question -- "I'm very happy serving the great people of wherever it is I'm from and I hate Washington" -- everybody would expect him to announce his candidacy within a few weeks.

By that bizarre standard -- that is, by the bizarre standards of presidential hint lingo -- Ryan has spent months jumping up and down, waving his arms and screaming that he wants to run for president.

Flat denials of interest are simply rote, signalling nothing whatsoever about their intent. I've been hyping his various unsubtle hints of interest, including his delivery of a foreign policy address, apropos of nothing. Ryan is undoubtedly considering a presidential candidacy, based on Stephen Hayes' reporting.

Now, that is not to say Ryan will run. The logistical hurdles, ably described by Chris Cilizza, are serious. Part of what Ryan is doing in his dance of the seven veils is to try to suss out whether the party establishment would rally behind him with the near-unanimity needed to overcome those hurdles.

So this is where we stand. The most seemingly formidable possible nominee is hampered with overwhelmingly exploitable weaknesses in the primary. The race is wide open, but the best position for a candidate to hold is crazy enough to appeal to the party base but also able to present a moderate face to the broader electorate. The party base has become sufficiently empowered over the last two years that I think its veto carries more weight than the establishment's; a candidate with the crazy but not the electability (i.e., Michele Bachmann) probably stands a better chance of nomination than a candidate with the latter but not the former (Romney.) That said, I've long thought the nominee would probably be somebody who could do both. That explains my bad horse race pick of Pawlenty, who turned out to be a poor campaigner, but also suffered from a terrible moment in the first GOP debate which sent his campaign into a death spiral from which it never recovered.

Rick Perry seemed like the best possible candidate to bridge the crazy-electable divide. But his initial image tilts a lot closer to "crazy" than "electable" than most predicted, and the establishment is nervous about him. Perry now leads in the most recent national poll, but this merely demonstrates the shallowness of Romney's support, which floated along on name recognition, the perception of being the front-runner, and a general lack of awareness of his many apostasies. Still, at this moment, Perry seems like the best bet.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers