Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 4

August 30, 2011

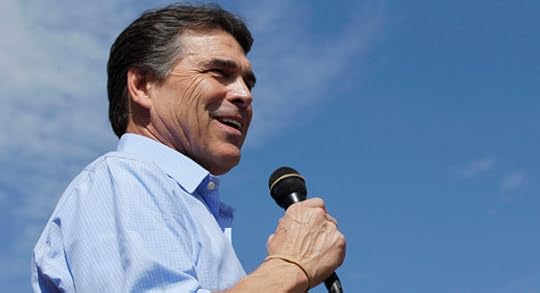

Rick Perry's Real Science Problem

Rich Lowry's defense of Rick Perry seems to badly miss the point:

In no sense that the ordinary person would understand the term is Rick Perry “anti-science.” He hasn’t criticized the scientific method, or sent the Texas Rangers to chase out from the state anyone in a white lab coat. In fact, the opposite. His website touts his Emerging Technology Fund as an effort to bring “the best scientists and researchers to Texas.” The state has a booming health-care sector composed of people who presumably have a healthy appreciation for the dictates of science....

Unless he has an interest in paleontology that has escaped everyone’s notice to this point, Perry’s somewhat doubtful take on evolution has more to do with a general impulse to preserve a role for God in creation than a careful evaluation of the work of, say, Stephen Jay Gould. ...

Similarly, Perry’s skepticism on man-made global warming surely has much to do with the uses to which the scientific consensus on warming is put.

Nobody is saying that Perry despises science per se. He rejects scientific findings when they complicate his theological or ideological worldview. And Perry is not taking the Jim Manzi-National Review position that climate scientists are correct but we shouldn't address climate change. He's accused climate scientists of running a corrupt scam -- a deranged belief that's increasingly common among movement conservatives.

What's more, the implications of Perry's willingness to discard science go well beyond scientific issues. It suggests a general unwillingness to acknowledge empirical results that run counter to one's ideological dispositions. That was an enormous problem in the Bush administration, but ultimately one, it seems, conservatives are happy to repeat.

The Democratic Jobs Debate As Mass Denial

The debate within the Democratic Party over President Obama's incipient economic relief program is being conducted between two sides that totally misunderstand its purpose. On the one side, you have administration centrists who support a sufficiently narrow plan that can pass Congress:

Mr. Obama’s senior adviser, David Plouffe, and his chief of staff, William M. Daley, want him to maintain a pragmatic strategy of appealing to independent voters by advocating ideas that can pass Congress, even if they may not have much economic impact. These include free trade agreements and improved patent protections for inventors.

And on the other side, you have liberals who demand boldness:

“Will he commit all his energy to offering bold solutions, or will he continue to work with the tea party?” AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka said at a recent breakfast hosted by the Christian Science Monitor, adding: “If he falls into nibbling around the edges, history will judge him and working people will judge him.”

Here's what everybody is missing: Nothing of significance can pass Congress. Maybe -- maaaybe -- an extended pressure campaign could force Republicans to agree to extend the payroll tax cut. But even that would have modest stimulative benefit. Anything larger has no chance of enactment. Republicans have strong ideological and partisan motives to block any further economic stimulus. Obama can try to design a strategy to exact a political toll for Republican obstruction, but he can't design a strategy to result in passing any significant new stimulus.

The moderates who think Obama can whittle his proposals down to the point where Congress will let them sail through simply haven't been paying attention to the GOP's strategic decision to deny Obama bipartisan cover. And the liberals who insist on a big plan seem to be in denial:

“Even though [Obama] knows Republicans will not allow it to pass Congress, this is a debate that will be settled only by the election, and he needs to go into the election telling the truth about what it will take to get out of this perpetual high-unemployment rut that we’re in now,” said Roger Hickey, co-director of the Campaign for America’s Future, a progressive strategy group.

Michael Ettlinger, vice president for economic policy at the liberal Center for American Progress, said the economy needs millions of new jobs — and the plan must meet that demand.

“The plan also needs to test the boundaries of what Congress is willing to do,” Ettlinger said. “The president should not start off trying to meet halfway people who only offer completely incoherent economic policy. The president should offer a plan that actually creates jobs, the jobs we need, and then take it to Congress and take it to the people. Offering a weak proposal and then complaining that Congress won’t take action isn’t the way to create jobs.”

It's true -- complaining about a weak proposal that didn't pass won't create jobs. At the same time, complaining about a strong proposal that didn't pass won't create jobs. Congress is not going to pass anything that will create jobs.

This does not mean there is nothing Obama can do. But his plan needs to be understood as a political strategy, not as a legislative strategy. The point of it is to propose something that is popular and which Obama can blame Republicans for blocking. There is no upside in blaming the opposition for blocking a bill that voters don't want to pass.

That means the plan does need to be somewhat big -- anything that's too small will transparently be seen as insufficient to the scale of the disaster. On the other hand, it needs to grapple with the reality that most Americans don't support the kinds of economic stimulus that economists think we need. Now, if Obama potentially had the votes in Congress to pass another stimulus, it would be worth taking an unpopular vote in order to rescue the economy. Since Obama does not and will not have those votes, he needs to conceive of his plan as a political message. There is no point in holding a message vote when the message is unpopular.

This seems to be a reality liberals have trouble acknowledging. There are a lot of issues where the public agrees with the left. Economic stimulus does not appear to be one of them. Now, public opinion is fairly hazy and ill-informed about this, and certain elements of economic stimulus can command majorities. But the passage of the first stimulus, at the height of Obama's popularity, shows pretty clearly that people instinctively think that, when the economy is terrible, having the government spend a lot of new money is not going to help. That they're wrong doesn't really matter for the purposes of this question.

The liberal dialogue about stimulus is almost a perfect parallel to the way conservatives talked about Social Security privatization in 2005. The idea was unpopular, and Democrats in the Senate were determined to block it. Conservatives, though, couldn't acknowledge this. They kept insisting that President Bush push harder, give more speeches, pressure Senate Democrats to give in. Conservatives kept saying this was vital -- we had to privatize Social Security or all would be lost, defeat was not an option.

This is not an argument for -- to use the popular epithet -- "fatalism." Obama has options. He can do his best to frame the debate so as to clarify that Republicans are blocking popular economic recovery measures, like the payroll tax cut and perhaps some infrastructure projects. Conceivably if he wins reelection, and the democrats make huge gains in the House, republicans will rethink their approach and open themselves up to some kind of compromise in 2013. In the meantime, I see no point in blinding oneself to reality.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

Obama And The Amnesty That Wasn't

[Guest post by Nathan Pippenger]

In my story yesterday, I tried to explain the longstanding practice of “prosecutorial discretion” in immigration enforcement, recently under attack by many of its former advocates, as well as some of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers tasked with carrying it out. Discretion, I noted, makes law enforcement agencies more effective by devoting scarce resources to addressing the most serious crimes.

Earlier this month, the Obama administration took an important step towards restoring some sanity to a disastrously dysfunctional immigration system when it announced it would examine—and apply discretion to—some 300,000 removal cases now sitting in immigration courts. (1996’s immigration reform law made “removal” the legal term for what used to be called “deportation.”) This decision has been widely misunderstood and misrepresented. It is not, as Arizona Governor Jan Brewer claimed, “a backdoor amnesty for hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of illegal aliens.” Nor does it put the president “on the verge of being lawless himself,” as Representative Steve King told Human Events (which itself wrongly claimed that the administration is “pulling out hundreds of thousands of illegal aliens already in the deportation pipeline.”)

This policy is simply an enactment of the principles laid out in ICE Director John Morton’s June 17 memo on prosecutorial discretion. That memo does not propose a blanket policy of relief for any undocumented immigrant without a criminal record. Instead, it lays out a series of specific criteria which represent compelling cases—cases in which prosecution would represent a waste of finite resources. These include victims of human trafficking, the elderly, veterans and active-duty members of the military, and pregnant women. One expert on immigration policy predicted to me that of the 300,000 cases to be reviewed, “not even half, not even tens of thousands—maybe thousands” will receive relief under the specific criteria of the Morton memo. Marshall Fitz, an immigration expert at the Center for American Progress, concurs. “The review of 300,000 cases is significant because it shows commitment to clearing the decks and tackling the current caseload,” he told me. “Whether it’s a few thousand or ten thousand cases that ultimately get administratively closed is anybody’s guess—but it’s certainly not going to be in the realm of hundreds of thousands.”

And that’s in an immigration court system currently overwhelmed by pending cases. In some instances, the waiting period for a hearing is as long as 18 months. As I noted yesterday, in exercising discretion, the administration is acting within a well-established bipartisan tradition. It is possible to disagree with the wisdom of this policy. But portraying it as an unprecedented power grab, a “backdoor amnesty” for millions of “illegals,” or a naked refusal to enforce the law is deeply ignorant at best.

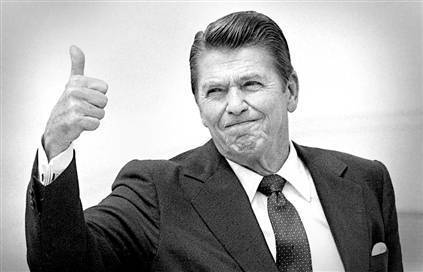

Paul Samuelson, Even While Dead, Still Way Smarter Than Steve Moore

With David Frum moving in on my dissecting Wall Street Journal editorial territory, and now Zack Beuachamp cutting in on my patented role of pointing out Pete Wehner's hackery, it becomes all the more vital that I cling to my role of ridiculing Stephen Moore, the Journal's lead economics editorial writer and my most cherished foil.

Moore's latest column argues that President Obama's economic program has failed and that President Reagan's succeeded, ergo Keynesian economics is wrong and supply-side economics is correct. Moore begins by asserting that Keynesian economists predicted that the 1980s recovery was impossible:

The Godfather of the neo-Keynesians, Paul Samuelson, was the lead critic of the supposed follies of Reaganomics. He wrote in a 1980 Newsweek column that to slay the inflation monster would take "five to ten years of austerity," with unemployment of 8% or 9% and real output of "barely 1 or 2 percent."

Moore has repeated this quote, or versions of it -- he has occasionally described it as a Samuelson interview rather than a column, or as having occurred in 1979 rather than 1980 -- on multiple occasions. He used it in a 1993 National Review article ("Clinton's Dismal Scientists,") a 2000 American Enterprise piece ("Thank You, Ronald Reagan,") his 2008 book ("The End Of Prosperity,") an October 2009 American Spectator piece ("Not-So-Gentle Ben,") and of course the recent Journal column.

The funny thing is, having obtained the column, Samuelson does not make anything like the argument Moore has attributed to him all these times. In the column, Samuelson laid out a series of possible responses to stagflation, without advocating for one over the other. Moore quotes one possible policy option Samuelson described. But Samuelson absolutely did not say this was the only way to stop inflation. He also described another possible course of action:

The Federal Reserve and Administration authorities can abandon their gradualism, and act now to tighten credit fiscal policies severely. ... That could mean prime rates that rise briefly to 20 percent, a decline in the monetary aggregates for several months, and a drastic rein on non-defense spending this year.

That is, in fact, what happened in 1982. It worked as Samuelson predicted in the column. Now, it is true that Samuelson called for fiscal tightening when the Reagan administration instead increased the deficit. But the general picture of inducing a recession in order to crush inflation followed the pattern Samuelson laid out.

Proceeding from this false, though well-worn premise, Moore argues that the failure of Obama's recovery is an indictment of his policies, though Moore does not say which ones. (Keeping the Bush tax cuts in place is presumably not the problem Moore has in mind.) Instead, Moore ridicules the favored theory of the left:

The left has now embraced a new theory to explain why the Obama spending hasn't worked. The answer is contained in the book "This Time Is Different," by economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff. Published in 2009, the book examines centuries of recessions and depressions world-wide. The authors conclude that it takes nations much longer—six years or more—to recover from financial crises and the popping of asset bubbles than from typical recessions.

In any case, what Reagan inherited was arguably a more severe financial crisis than what was dropped in Mr. Obama's lap. You don't believe it? From 1967 to 1982 stocks lost two-thirds of their value relative to inflation, according to a new report from Laffer Associates. That mass liquidation of wealth was a first-rate financial calamity. And tell me that 20% mortgage interest rates, as we saw in the 1970s, aren't indicative of a monetary-policy meltdown.

There are a couple comical details here. The notion that Reinhardt and Rogoff speak for "the left" is pretty hilarious. Anyway, their theory is that financial crises lead to much slower recoveries than other kinds of recessions. The entire premise of their argument, in other words, is that a recession caused by a financial crises is fundamentally different than other kinds of recessions.

Moore responds to this by asserting that the period leading up to 1982 was really bad. Well, yes. Recessions are bad. Moore does not explain why the Federal reserve-induced 1982 recession qualifies as a financial crisis, which is the whole definitive crux of Reinhart and Rogoff's thesis.

If you read Moore's entire column, you'll see that I'm not nibbling around the edges of his thesis. That is his entire thesis -- falsely assuming that Keynesians could not account for the 1980s recovery, and then missing the whole point of the Reinhart/Rogoff argument. This is the country's leading financial newspaper!

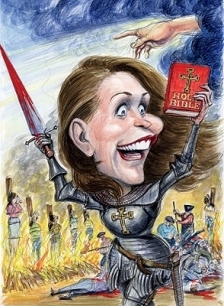

Is Michele Bachmann Jewish?

The says some Jewish Republicans seem to believe so:

The says some Jewish Republicans seem to believe so:

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney is facing a new challenge: He's having trouble raising money from some Jewish donors who mistakenly believe one of his opponents, Michele Bachmann, is Jewish.

Some Jewish donors are telling fund-raisers for Romney, a Mormon, that while they like him, they'd rather open their wallets for the "Jewish candidate," who they don't realize is actually a Lutheran, The Post has learned.

"It's a real problem," one Romney fund-raiser said. "We're working very hard in the Jewish community because of Obama's Israel problem. This was surprising."

Wait. First, I thought pretty much the one thing people knew about Bachmann is that she's from the Christian right. But forget about that for a minute. Doesn't every American Jew know that -mann names are invariably non-Jewish?

August 29, 2011

&c

-- Some more highlights from Alan Krueger's academic career.

-- Christopher Hitchens asks: "Does the Texas governor believe his idiotic religious rhetoric, or is he just pandering for votes?" I ask: why not both?

-- Alan Krueger's co-author on their most famous paper: "I've subsequently stayed away from the minimum wage literature for a number of reasons. First, it cost me a lot of friends."

-- Inside the mind of Dick Cheney.

Understanding Ron Paul

Matthew Yglesias points out that Ron Paul is much more of a Buchananite than a libertarian:

a lot of progressives seem to be slightly confused as to who Ron Paul is. They think he’s like that one rich uncle you have, shares a lot of your basic values but hatespaying taxes and seems to take a dim view of poor people. The reality is that Paul is much closer to Pat Buchanan, a socially conservative nationalist whose idea of nationalist foreign policy is to withdraw troops from South Korea and deploy them to the Mexican border. Given what a strong force nationalism is in American life, I do wish that we had more nationalist isolationism and less nationalist enthusiasm for global contrast. But Paul’s view is that the quest to ban abortion is “the most important issue of our age,” his signature economic policy idea (“End the Fed!”) is a crank slogan that has nothing to do with free market economics, etc.

I agree. Being much more of an interventionist than Yglesias is, I find Paul's domestic and foreign policies to be very closely aligned and easily understood. He is fatalistic about successful government action, and he wouldn't support it even if convinced it worked. Paul sees the notion of government as a means to carry out a collective action to help people utterly inimical to his views.

If you think of war, as Yglesias does, as primarily reflecting "nationalism," then Paul's combination of views is a little odd. But consider something like the intervention in Libya. This was a decision to use government power to try to help a bunch of people overseas who were about to be massacred by a sociopathic dictator. The surprising thing isn't that anybody on the right would oppose such an operation. The surprising thing is that anybody on the right would support it. Military intervention does carry nationalistic overtones that non-military intervention lacks. But there was no real national interest at stake here, and the question boils down to what risk and expenditure the U.S. should take to aid Libyan rebels. I don't see any part of Paul's ideology as sharing my views.

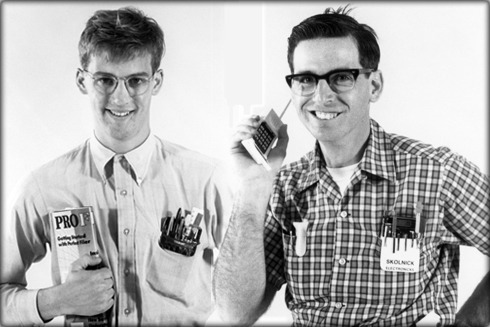

How Nerds Ceased To Exist

Ben Zimmer explores the eytomology of "nerd":

The earliest known example comes from an Oct. 8, 1951, Newsweek article rounding up teenager talk from around the country. “In Detroit,” according to the article, “someone who once would be called a drip or a square is now, regrettably, a nerd, or in a less severe case, a scurve.” Over the next few years, the Newsweek slang - nerd included - got rehashed in other magazines, like Reader’s Digest and Collier’s. By 1954, nerd had spread to Denver, according to an Associated Press article. William Morris entered the word in his “Real Gone Lexicon” that same year, defining it as “a square, one who is not up with the times.”

A few weeks ago, my 7 year old daughter told me that a counselor at her day camp was a nerd. I immediately reproached her -- this was a mean thing to say, she should never call anybody a nerd. Confused, she replied that the counselor had used the term to describe herself. A nerd, my daughter explained, meant a person with a deep interest in a particular subject -- a math nerd, a photography nerd, a Harry Potter nerd.

I suspect that the word's negative connotation is an artifact of previous generations' hostility toward technology. It wasn't long ago that possession of even fairly basic technology skills was a mark of shame. Check out this Simpsons episode from 1995, in which Bart is introduced to the nerd table at school. One of the nerds is called "Email," familiarity with which was sufficient to demonstrate a status as a freak (the relevant scene starts at 7:50, but the entire episode is great):

Ham: Won't you join us, Bart?

Bart: [looks around] Uh...I guess so.

Database: As the first student at Springfield Elementary to discover a

comet, we're very proud to make you a member of our very select group. Welcome to Super Friends.

Bart: Huh?

Kids: Welcome, Super Friend

Ham: I am called Ham, because I enjoy ham radio. This is Email...Cosine...Report Card...Database...and Lisa.Your nickname will be Cosmos.

Bart: [finishing a mouthful hurriedly] Well, I'm done eating.

Goodbye.

Today, that joke would be moot -- not only the particular gag that only geeks use email but also, I'd argue, the general premise that only geeks understand technology. Mastery of a wide array of gadgets is de rigueur among the younger generation, making it almost impossible for them to imagine that mastery of some other set of devices is uncool. "Nerd" has almost totally lost its stigma. A nerd is simply an enthusiast. One can be almost any kind of nerd -- even a professional football player describing himself as a football nerd, a term that, twenty-five years ago, would have made no sense.

This is, I think, one of the salutary trends in American culture.

Bachmann, Perry, And Theocracy

Ross Douthat's column today urging liberals not to overhype the theocratic roots of Republican presidential candidates has some well-taken points. But it suffers from a couple important flaws. First, Douthat doesn't provide any specific examples of liberals committing the various sins he describes. No doubt this is a function of small constraints, but it's a piece that badly needed to be a long, detail-rich essay rather than a 700-word column. The most prominent example of a study of a presidential candidate's theological beliefs is Ryan Lizza's masterful profile of Michelle Bachmann. In that piece, Ryan made a concerted effort to understand the whole of Bachmann's worldview, rather than cherry-pick loose connections here and there.

Does Douthat object to Lizza's portrait? If he does, I'd like to know how so. If he doesn't, it's important to note that the single largest example of liberal analysis of the religiosity of the GOP field does not display any of the flaws he identifies. Douthat mentions the piece but does not actually say that it commits (or doesn't commit) the sins he identifies.

Second, Douthat offers up a seductive but ultimately quite weak analogy to President Obama:

If you roll your eyes when conservatives trumpet Barack Obama’s links to Chicago socialists and academic radicals, you probably shouldn’t leap to the conclusion that Bachmann’s more outré law school influences prove she’s a budding Torquemada. If you didn’t spend the Jeremiah Wright controversy searching works of black liberation theology for inflammatory evidence of what Obama “really” believed, you probably shouldn’t obsess over the supposed links between Rick Perry and R. J. Rushdoony, the Christian Reconstructionist guru.

The real problem with the right-wing obsession with Obama's "real" roots is that they do not reflect in any way upon Obama's public record. Obama is a mainstream Democrat, surrounded by Clinton-era veterans, and pursuing roughly the same policies that Bill Clinton would be pursuing if he were president under current circumstances. Bachmann and (to a slightly lesser extent) Perry are at the forefront of a movement to redefine their party's ideology in far more radical hues. Their ideological and theological roots offer useful clues to figuring out this new direction. It's clearly not completely separate from their policies. Bachmann is running around saying that natural disasters are God's message to cut spending. It's not a reach to tie her program to her theology. She does it herself constantly.

August 22, 2011

&c

Joe Biden and a Mongolian wrestler.

Ryan Gosling breaks up a fight.

All the different theories for what’s wrong with the economy.

“Leading from behind” to victory.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers