Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 155

November 15, 2010

The War Over the Body Scanners

It was inevitable: The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is facing a backlash against its use of full-body scanners, or as our legal affairs editor calls them, the "dangerous naked machines," to screen airline passengers for concealed weaponry. Are they an unwarranted invasion of privacy? Are they justified in the name of security?

Click below to read TNR's arguments for and against:

"Private Security: In Defense of the 'Virtual Strip-Search,'" by Amitai Etzioni

"Nude Awakening: The Dangerous Naked Machines," by Jeffrey Rosen

BODY SCANNERS >>

Fight Or Bargain? Tax Cuts vs. The Deficit

Coming out of the midterm elections, the Obama administration faces two questions on which the choice is fight or cooperate -- the deficit commission and the Bush tax cuts. On both issues, most liberals want the administration to fight, while the conventional wisdom advocates some kind of compromise. To get a sense of how temporary extension of all the Bush tax cuts is now received in official Washington as a sensible compromise, consider the language in this recent Washington Post story:

In the days after the election, that cold reality appeared to have overtaken the harsh rhetoric of the campaign trail. A consensus was quietly emerging on taxes, with key lawmakers and senior aides saying both parties were preparing to accept a temporary extension of all the cuts to defuse a brutal, drawn-out fight.

Brutal fights and harsh rhetoric are bad. "Reality" is good.

Anyway, the liberal position is relatively coherent: Obama should fight to stop the Bush tax cuts as well as the debt commission's plan, which is quite tilted toward Republican priorities. I'm in favor of fighting on the tax cuts and exploring a potential deal on the deficit.

The one position that's totally incoherent is the belief that Obama should cooperate on both. First, the policy aims are radically in tension: extending the Bush tax cuts, which pushes the ball down the field and gives Republicans another chance to keep them alive by invoking the dread specter of a middle-class tax hike, increases the chances that they'll be made permanent and thus threatens to increase the deficit.

On top of that, it weakens the Republicans' incentive to make a deal on the deficit. After all, how they judge the tax provisions in the debt commission's proposal ultimately depends on what they have to compare it to. The Republicans' primary goal is to reduce the tax burden on the rich. Compared to a tax code where the Bush tax cuts have expired, the commission's tax proposal might not look too bad. Compared to a tax code where the Bush tax cuts remain fully in effect, it might look bad indeed. Capitulating on taxes makes the slim chances of a deficit deal virtually nil.

Believing the administration should compromise on both issues makes sense only if you're attracted to the aesthetics of bipartisanship with no interest in the substance of the policy. Sadly, this described a fair chunk of the Washington establishment.

David Frum Goes Bulworth

It's pretty remarkable to remind yourself that not long ago David Frum was writing speeches for George W. Bush, and now he is writing things like this:

It's pretty remarkable to remind yourself that not long ago David Frum was writing speeches for George W. Bush, and now he is writing things like this:

Well before the crash of 2008, the U.S. economy was sending ominous warning signals. Median incomes were stagnating. Home prices rose beyond their rental values. Consumer indebtedness was soaring. Instead, conservatives preferred to focus on positive signals — job numbers, for example — to describe the Bush economy as “the greatest story never told.”

Too often, conservatives dupe themselves. They wrap themselves in closed information systems based upon pretend information. In this closed information system, banks can collapse without injuring the rest of the economy, tax cuts always pay for themselves and Congressional earmarks cause the federal budget deficit. Even the market collapse has not shaken some conservatives out of their closed information system. It enfolded them more closely within it. This is how to understand the Glenn Beck phenomenon. Every day, Beck offers alternative knowledge — an alternative history of the United States and the world, an alternative system of economics, an alternative reality. As corporate profits soar, the closed information system insists that the free-enterprise system is under assault. As prices slump, we are warned of imminent hyperinflation. As black Americans are crushed under Depression-level unemployment, the administration’s policies are condemned by some conservatives as an outburst of Kenyan racial revenge against the white overlord.

Meanwhile, Republican officeholders who want to explain why they acted to prevent the collapse of the U.S. banking system can get no hearing from voters seized with certainty that a bank collapse would have done no harm to ordinary people. Support for TARP has become a career-ender for Republican incumbents, and we shall see what it does to Mitt Romney, the one national Republican figure who still defends TARP.

The whole piece is a dead-on attack on the central thrust of conservative thought over the last two years. I think it's desperately necessary that sane people reform the conservative movement into a non-pathological, reality-based force in American politics. But I fear Frum is slaying so many sacred cows that nobody in the movement will listen to him.

Max Baucus, Strategic Genius

If there's one clear and unequivocal thing the Democrats did wrong in the last session, it was letting the health care debate consume virtually all the Congressional term. The longer and more acrimonious the debate, the more the process itself colored perceptions of the bill, and the more it fed the perception that Democrats were ignoring the economy. They could have passed the exact same bill in early fall, sparing themselves months of process stories and Cornhusker Kickback angst, and then tried to build support for some kind of temporary tax cut or another economic measure. Instead, they consumed months on end in a completely futile question for Republican votes. There is literally no rational argument that the Democrats were better off passing a bill in the Spring rather than passing the exact same thing six months earlier.

If there's one clear and unequivocal thing the Democrats did wrong in the last session, it was letting the health care debate consume virtually all the Congressional term. The longer and more acrimonious the debate, the more the process itself colored perceptions of the bill, and the more it fed the perception that Democrats were ignoring the economy. They could have passed the exact same bill in early fall, sparing themselves months of process stories and Cornhusker Kickback angst, and then tried to build support for some kind of temporary tax cut or another economic measure. Instead, they consumed months on end in a completely futile question for Republican votes. There is literally no rational argument that the Democrats were better off passing a bill in the Spring rather than passing the exact same thing six months earlier.

Unless, of course, you're Max Baucus:

The key Senate Democrat who delayed health care reform last year while trying to get Republican buy-in is now facing the uncomfortable reality of his own prediction, leading him to weigh some bipartisan changes to his party's signature legislation.

U.S. Sen. Max Baucus' reputation as a dealmaker will be put to the test as he faces resurgent Republicans hostile to legislation that has been associated with him nearly as much as President Barack Obama.

The high-ranking Democrat, who has in the past drawn the ire of party faithful for seeking middle ground with Republicans, can't escape his prediction last summer that the health care bill needed GOP votes if it was going to last the years. At the time, liberals hammered him for trying to get Republicans on board.

"And I was right," Baucus said.

Really, that's your takeaway? You were right? Look, I don't think Republicans support was as valuable as Baucus did, but I agree it had real value. But you had to weigh that value against the considerable cost of delaying the bill. If Baucus ended up securing GOP support at the cost of delay, you could argue about whether it was worth it. Yet the calculation here is not very difficult. There was zero Republican support. The party simply made a calculation to withhold its votes and make the bill completely partisan, driving down its popularity. Olympia Snowe voted against the final product even though it was the same thing as what she voted for out of committee.

Let's tabulate this. Costs of Baucus's strategy: high. Benefits: zero.

November 13, 2010

Response To Douthat On Liberal Empiricism, Conservatism Rand-ism, And -- Yes! - The Debt Commission

Ross Douthat says that the reaction to the debt commission proposal has obviated my entire worldview:

One of Chait’s long-running themes is the idea that on size-of-government issues, conservatives are ideologues and liberals are pragmatists: That is, conservatives believe in smaller government as an end unto itself, whereas liberals only believe in bigger government when it’s accomplishing something meaningful for the common good. And one of his secondary themes is that the real “essence” of American conservatism isn’t deficit reduction, but rather “opposition to the downward redistribution of income” — whereas liberals, of course, see downward redistribution as precisely the kind of welfare-enhancing thing that government ought to do.

These are both disputable premises. But if we were to concede them, then it suddenly becomes much harder to justify Chait’s claim that the Bowles-Simpson plan is “tilted, overwhelmingly, toward Republican priorities.” Yes, it’s tilted toward spending cuts, and away from tax increases. But look at the way it cuts spending and raises taxes. It means-tests Social Security benefits for high earners and raises the cap on taxable income, while also adding a larger benefit for the poorest seniors. Its hypothetical discretionary spending reductions don’t come from anti-poverty programs, for the most part: They come from cutting the defense budget, cutting the federal workforce, cutting farm subsidies, etc. It raises tax revenue by reducing tax credits and deductions that almost all overwhelmingly benefit the affluent. (This would be especially true in the scenario I’d prefer, in which the child tax credit and the earned-income tax credit stick around.) It would cap revenue at 21 percent of G.D.P., which would be higher than any point in recent American history, and well above the average for the last thirty years. And it does all of this, as Chait himself notes, while assuming that Obamacare — the capstone of the liberal welfare state — would remain essentially unchanged.

If you accept Chait’s vision of a close-minded, Ayn Randian right and a pragmatic, non-ideological left, you would expect conservatives to be furious over the means-testing and loophole-closing, and liberals to be delighted to have a more redistributionist welfare state. Yet conservative reaction has been muted and respectful (with a notable exception, admittedly) while liberals have been flatly dismissive. Which suggests that maybe, just maybe, American liberalism has more of an ideological commitment to ever-rising government spending than Chait wants to admit.

He is describing my beliefs pretty accurately, but he's not making a persuasive case that they've been undermined. Belief #1 is that the Republican Party is driven far more by opposition to redistribution than by opposition to government per se. That has been the thrust of Republican policy-making on and off since 1980, and unremittingly since 1990. To me, the response on the right vindicates that analysis. After all, the debt commission's report entails a massive rollback of government. It does have some revenue increases, but those are accompanied by enormous cuts in income and corporate tax rates, and it's not clear if the net effect of the changes is to increase or decrease the share of taxes paid by the rich.

If the Republican Party was generally motivated by opposition to government, they would be dancing in the aisles. After all, this is a plan to both slash the size of government by about as much as it's ever been slashed, and slash tax rates. And yet the right's reaction is fairly tepid. The Tea Party movement is opposed. Grover Norquist is on the warpath. The Wall Street Journal editorial page is highly skeptical. I've seen a mostly positive editorial from National Review, but as of Friday evening, the Weekly Standard has written nothing at all. I wrote that the plan is overwhelmingly titled toward Republican priorities, and by that I meant putative priorities. The mixed response to a plan that would represent massive progress toward limited government makes my case for me.

Now, what about the liberals? Here I don't understand Douthat's point at all. My argument is that liberals favor government instrumentally, while conservatives oppose government ideologically. That is to say, conservative ideology -- small-government ideology, not the actual voting behavior of the Republican party -- sees small government as an end in and of itself. If you have a plan to reduce domestic spending by a quarter,almost any conservative would call that a good thing per se. Liberals would not be in favor of any increase in spending per se. It would depend on that spending actually having some positive real-world effect.

Douthat sees liberal dismay at the commission as evidence that liberals harbor "an ideological commitment to ever-rising government" parallel to the conservative worldview. What? Why? Liberals are not opposed to slashing farm subsidies. They're opposed to raising the Social Security retirement age and charging admission at the National Zoo. I agree with them that government ought to let a waitress retire on a modest public pension at 65, and should be able to operate a free world-class zoo in its national capitol. That's not the same thing as believing more government per se is good.

November 12, 2010

What Are Democrats Thinking On Taxes? Seriously, What?

In the face of yet another spate of signs that Democrats plan to capitulate on taxes, the full insanity of this moment cannot be processed without recalling how we got to this point. In 2001, Republicans decided to pass big top-rate marginal tax cuts. These had little public support, so in order to make them palatable, they included them in a package of middle-class tax cuts and sold the whole thing largely as a Keynesian response to the mild 2001 recession.

When Barack Obama ran for president, he had to decide how to handle the issue. The best policy, Democratic wonks understood, was to cancel out all the tax cuts. Clinton-level tax rates are really what you need to to realistically fund the government, under either party's spending plans. But that would have given Republicans a strong political issue -- Democrats want to raise your taxes! So instead they decided to phase out just the part of the Bush tax cuts on income over $250,000. It's a politically-minded compromise. It stinks, but I would have done the same thing.

Now, the tax cuts are expiring, and Republicans say you have to address the whole package together. You can make it permanent or temporary, but the line in the sand for them is that you can't decouple the tax cute for income over $250,000 from the rest.

The Democrats think this is some kind of dilemma. It's not. It's a get out of jail free card. It's the perfect excuse to let the whole Bush tax cut package expire. You can say, hey, we tried to extend those tax cuts but the Republicans blocked us. It has the virtue of being completely true.

Now, Republicans say they'll block the whole tax package if Democrats hold a vote just for tax cuts on income under $250,000. Do you think they really can really hold that line? To quote a noted statesman, hell no they can't:

U.S. House Republican Leader John Boehner said he would vote for middle-class tax cuts sought by the Democratic Obama administration even if it means eliminating reductions for wealthier Americans.

Boehner would support extending tax cuts for those making less than $250,000 a year “if that’s what we can get done, but I think that’s bad policy,” he said yesterday on CBS’s “Face the Nation” program. “If the only option I have is to vote for some of those tax reductions, I’ll vote for it.”

That quote is from September, but the logic still holds. Boehner was admitting the truth: having to vote against popular middle-class tax cuts because they don't also include unpopular upper-class tax hikes is a horrible position for Republicans. They're deathly afraid of it. That's why they insist on voting on everything together:

GOP sources in particular say keeping tax cuts for the middle class and the wealthier Americans linked may be in their best interest.

They say an idea that had been floating - to "decouple" - is untenable. Under that scenario, middle class tax cuts would be made permanent and tax cuts for wealthy Americans would be extended temporarily.

These GOP sources say that would put them at a political disadvantage in that it would make the discussion all about tax cuts for the wealthy. The sources also say tax cuts for the wealthy would be harder to extend in the future without being linked to middle class tax cuts.

In 2001, Republicans managed to pull this off because they controlled the White House and both houses of Congress. They could frame the whole agenda. They can't do that now. They might block a middle-class tax cut, and then taxes would go up, and people would get upset. Then President Obama would start making speeches demanding an up-or-down vote on middle-class tax cuts, and flaying Republicans for blocking it because they think that if Donald Trump can't get a tax cut, then nobody can get a tax cut. One of the huge benefits of having the bully pulpit is that you can prevent the opposition from hiding its unpopular positions.

How long would Republicans hold out? I don't know, but the best case scenario would be forever. You can't devise a better issue to fight for Democrats. They're the champions of middle-class tax cuts against a party that cares only about the rich. You want a cure for the perception that Democrats are just for big government? The Republicans are handing that cure to them on a platter. And they won't take it.

Think about it from the Republican point of view. The political aspect of this issue is a zero-sum competition. What do Republicans want? They want Democrats to extend all the tax cuts together. What they don't want is to have to fight for the tax cuts for income over $250,000 separately. They're terrified of it.

I understand that some Democrats are extremely responsive to the richest 2-3% of their constituents, who make more than $250,000 and feel put upon. So fine -- have a separate vote. Nobody's saying you can't vote for tax cuts for your rich friends. The whole thing is that you have to separate the two.

A while ago, I was corresponding with a conservative -- a real conservative, not a liberals' idea of a conservative -- about why the Democrats won't do the obvious thing. He was at a total loss. He attributed it to exhaustion and demoralization keeping them from thinking straight. That's the best explanation I can think of.

The Debt Commission's Gaping Flaw

Stan Collender identifies the biggest hole in the center of the debt commission's plan -- it wrenches billions of dollars out of the domestic discretionary budget without saying what functions will be sacrificed:

The plan calls for a substantial reduction in federal employees. A reduction in employees generally results in the government relying on more outside consultants to get the work done but, in addition to the recommended reductions-in-force, Bowles-Simpson also calls for a significant cuts in the use of contractors.

The combination of those two seems to indicate that the now smaller number of federal employees will have to do everything that was done before, that is, that they will have to be much more productive. But Bowles-Simpson also calls for a three-year freeze on federal employee salaries and that almost inevitably means an increasing number of federal workers will quit. That will reduce rather than increase productivity as new and less experienced workers replace the more senior folks who will have left for greener pastures.

In other words, Bowles-Simpson projects substantial savings based on the expectation that a less experienced and much smaller federal workforce will be more productive and just as effective than the more experienced and larger workforce it replaces. That makes absolutely no sense.

Bowles-Simpson seems to have been put together backwards. Instead of starting with a plan about what the federal government should no longer do and then determining the savings from the smaller number of employees that would be needed to do what's left to be done, with limited exceptions the plan focuses on the reduced workforce but makes few assumptions, suggestions, or recommendations about what services the government should no longer provide. The assumptions it does make don't appear to justify the cuts in the number of employees and contractors.

The type of proposals that are needed are: Should the government stop prosecuting and jailing as many criminals and should the sentences be shorter for those it convicts? Should it fund less or no research on cancer and similar diseases? Should the FBI no longer investigate white collar crime? Should the military not be prepared to conduct as many operations? Should veterans health care be eliminated?

Here is the deeper problem. Conservatives are convinced the federal budget is filled with waste and useless bureaucrats. Yet they have a very difficult time articulating functions that the government is fulfilling that it shouldn't be. There certainly are some -- farm subsidies is one of the biggest examples. The government should get out of that business altogether.

But for the most part, the domestic discretionary budget has been squeezed for savings for several decades on end. Virtually all of the programs remaining represent important public functions. That's why the commission is reduced to proposing charging visitors to the national zoo and implementing phony schemes to cut government staff and pay without changing any of government's mission. If you want to treat this portion of the budget reasonably, you need to either actually agree on some functions the federal government will stop performing, or else just recognize that you need to start paying for the functions it is performing. Catering to airy conservative prejudices against government without translating that into a specific re-conception of the federal role is useless.

To be clear, I think the revenue increases, defense spending cuts, cuts to assorted programs like farm subsidies, and entitlement cuts are a coherent and useful contribution to the deficit problem. The treatment of the discretionary budget is not.

Olympia Snowe Is On The Clock

Looks like Olympia Snowe is getting a right-wing primary challenger in Maine:

I have direct knowledge of a conservative in Maine who is preparing to challenge Olympia Snowe. He has told me he is running but has asked me to keep things vague so as not to step on his announcement, which he plans to make early next year. He comes out of the tea-party movement and I have every reason to believe he’s serious about this.

As for Snowe, she had better be looking over her right shoulder. Last month, Public Policy Polling found that 63 percent of Maine Republicans would support “a more conservative alternative” to Snowe, while only 29 percent were committed to her. PPP added:

Moderate Republicans love Snowe. They give her a 70% approval rating and a strong majority say they’d vote to nominate her for another term. But those folks make up only 30% of the GOP electorate in Maine. It’s now dominated by conservatives and they’re particularly negative toward her, giving her just a 26% approval rating and saying by a 78-15 margin they’d like to trade her out for someone to the right.

Things can change in two years, but the way the Republican Party is currently operating, primary challenges like this are nearly impossible to defeat. Christine O-Donnell won, and she was pretty obviously a totally underqualified borderline nutcase. Maine looks like a prime pick-up opportunity for Democrats in 2012. If I'm Snowe, I'm figuring my best chance to retain the seat is not to try to lurch to the right -- which hasn't worked for anybody; these activists have long memories -- but to make a plan to hold the seat as an independent or Democrat. The chances of surviving that way are way higher than the chances of making it through a Republican primary. Snowe could always try to run to the right between now and 2012, and then bolt from the party if she loses (or faces the certain prospect of losing) the primary. But then she looks opportunistic and probably just loses to a Democrat in the general election.

Of course, that's just fine by me. I don't especially care for Snowe. But at Jonathan Chait, our policy is to hand out free political advice to everybody regardless of party or ideology.

Do Krugman And I Disagree On The Debt Commission?

My take on the debt commission is provisionally favorable, while Paul Krugman's take is unremittingly hostile. That's kind of interesting, because I generally agree with Krugman about economic policy. What, then, is the source of our disagreement? Let me go through a couple points in his column.

First, Krugman objects to the revenue cap and the cap on health care spending:

Start with the declaration of “Our Guiding Principles and Values.” Among them is, “Cap revenue at or below 21% of G.D.P.” This is a guiding principle? And why is a commission charged with finding every possible route to a balanced budget setting an upper (but not lower) limit on revenue?...

it becomes clear, once you spend a little time trying to figure out what’s going on, that the main driver of those pretty charts is the assumption that the rate of growth in health-care costs will slow dramatically. And how is this to be achieved? By “establishing a process to regularly evaluate cost growth” and taking “additional steps as needed.” What does that mean? I have no idea.

I find these two provisions vague, bordering on meaningless. With no enforcement mechanism, what does it mean? Very little. In theory, the commission could add some kind of triggering mechanism to make the cap powerful, at which point you have to vote the thing down. That seems unlikely anyway.

Second, Krugman sees the tax provisions as a sop to the rich:

Actually, though, what the co-chairmen are proposing is a mixture of tax cuts and tax increases — tax cuts for the wealthy, tax increases for the middle class. They suggest eliminating tax breaks that, whatever you think of them, matter a lot to middle-class Americans — the deductibility of health benefits and mortgage interest — and using much of the revenue gained thereby, not to reduce the deficit, but to allow sharp reductions in both the top marginal tax rate and in the corporate tax rate.

It will take time to crunch the numbers here, but this proposal clearly represents a major transfer of income upward, from the middle class to a small minority of wealthy Americans.

I have to admit I have no idea if he's right. Nobody has crunched the numbers yet. I think most liberals have the mental model of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, which lowered rates dramatically but still (slightly) increased the effective burden on the rich by closing loopholes, including preferential treatment for income from capital gains. The commission's plan does close those loopholes, but we don't know if the rate cuts are so low that they cancel out the distributional impact. It's actually a pretty interesting black box, with some liberals assuming the tax provisions are progressive and others assuming the opposite.

I've assumed the opposite because I've assumed the commission understands that any tax plan that shifts the tax burden downward is a dead letter. But that is a crucial piece of the puzzle that we'll have to wait on.

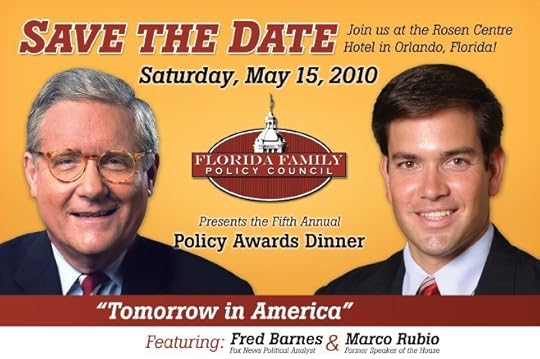

Conservative Journalists Fight For Marco Rubio's Love

Conservative talk show host Mark Levin and The Weekly Standard's Stephen Hayes are waging an utterly hysterical skirmish over which one loves, and is loved by, Marco Rubio more. Levin argues that he's the real Rubio supporter:

Steve Hayes conveniently ignores two things. First, when did the Weekly Standard endorse Rubio? Second, the first nationally syndicated talk show to endorse Rubio was ... mine.

Au contraire, replies Hayes -- the Standard has been slavishly supporting Rubio from the beginning:

THE WEEKLY STANDARD doesn’t endorse candidates. The magazine has never done so in its fifteen-year history.

But TWS has covered Rubio – quite a bit.

Rubio formally announced his candidacy on May 5, 2009. Three days later, on May 8, TWS reporter John McCormack wrote an article about the race that pointed out many reasons why conservatives ought to prefer Rubio to Crist. McCormack wrote that Rubio is "a dynamic speaker with an appealing biography and a deeply held conservative philosophy.” He noted that students who attended a Rubio event were “wowed” by his speech, with one saying: “I think we just saw the future president of the United States.” McCormack quoted a former editorial board member of the Miami Herald, saying Rubio is a “rising star” and “very impressive.”

The recounting of the Standard's sycophantic relationship with goes on at considerable length. Hayes concludes by sticking in the dagger:

In many hours of discussions with Rubio over the past five weeks, we spent a lot of time talking about how and why he won this election. Not surprisingly, he was humble about his own contributions and eager to share credit with others. I reported some of the folks he mentioned in my article: Rubio talked at some length about Jim DeMint and praised a cover story in National Review from August 2009. ...

My reason for leaving Levin out is much simpler: In our many hours of casual conversation and sit-down interviews, Marco Rubio never mentioned him.

Ooh, you hear that Levin? He didn't even mention you. In the hours and hours I got to talk to him, just the two of us. He's so not into you. He probably doesn't even know who you are. So just back off and leave me and Marco Rubio.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers