Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 15

May 15, 2013

Songs of the Vikings

"I know giants of ages past, … I know how nine roots form nine worlds / below the Earth where the Ash Tree rises..."

"I know giants of ages past, … I know how nine roots form nine worlds / below the Earth where the Ash Tree rises..."Last week I heard the "Song of the Sibyl" for the first time. I'd read this classic Old Icelandic poem, this witch's vision of the creation and destruction of the world many times in both English and the original language. I'd written about it in my book Song of the Vikings: “What troubles the gods? What troubles the elves?”

But never before had I heard someone recite it. In Old Icelandic, spontaneously, spouting off a few stanzas to make his point.

I was in Kalamazoo, Michigan, at the yearly conference of 5,000 or so of my fellow wizards, um, medieval scholars. One I'd particularly hoped to meet was Terry Gunnell of the University of Iceland. I knew him for his translations of Icelandic folklore, but Gunnell is most interested in drama--old drama, like that of the Poetic Edda, which to me was never drama before but just a bunch of poems on a page. Some, like "Song of the Sibyl," I found quite moving. Others I thought were silly.

Then I listened to Gunnell speak on "Performance and the Study of Old Norse Religions."

When we read an oral poem silently, we "necessarily" take it out of context, Gunnell said, quoting the great scholar of oral literature John Miles Foley.

Added Gunnell, "We ignore the 'happening.'" The two poems he was talking about, Eiriksmál and Hákonarmál (loosely, "the Lay of Eirik" and "the Lay of Hakon"), "were not intended as written texts. They were meant as soundscapes presented to an audience who brought knowledge to them. They demand movement in space and gesture."

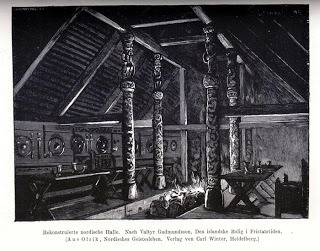

Think of a mead hall like the one in Beowulf, or our Hollywood image of Valhalla, or Beorn's hall in Tolkien's The Hobbit: a great wood-ceilinged hall with tree trunks for pillars, a long fire bisecting it, benches full of boisterous Vikings (or dwarves in Tolkien's version) brandishing their drinking horns. Someone stands up and starts reciting Hákonarmal.

Think of a mead hall like the one in Beowulf, or our Hollywood image of Valhalla, or Beorn's hall in Tolkien's The Hobbit: a great wood-ceilinged hall with tree trunks for pillars, a long fire bisecting it, benches full of boisterous Vikings (or dwarves in Tolkien's version) brandishing their drinking horns. Someone stands up and starts reciting Hákonarmal."The room is dark and smoky," said Gunnell. "The long fire is raising shadows. Impure alcohol has been imbibed. The performer is saying I. He's using the words in here. He's putting himself into the role of Odin, and the audience finds itself playing a role as well: We are the dead heroes of Valhalla and Ragnarok is about to become…

"We need to get away from seeing these poems as literature and to think of them more like music," Gunnell said in the Q&A afterwards. "Listen to the music of Völuspá"--it's here he started reciting it, the syllables crashing and clashing. It wasn't at all like the version on YouTube by Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson, which is all smooth and lilting and frankly puts me to sleep:

Gunnell's version was more like the concert I saw in Boston a few months ago by Sigur Rós: hammering, pulsing, the sound cracking open the mind.

"Listen," said Gunnell. He only gave us two stanzas. "It starts slow and open, then boom-boom-boom-boom, there's this little punk routine in the middle. Think of the smoke, the light, the booze. It's a PowerPoint in your head. The poet creates images in your head, helped by the alcohol and the next morning you say, What the hell was that?"

After the lecture I went up to Gunnell. "How much beer do I have to buy you to hear you recite the whole poem?" He laughed, but I was serious. I hope to meet him again in Iceland and be transported to the mead hall. I'll never just read the songs of the Vikings again.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on May 15, 2013 07:27

May 8, 2013

Remembering the Scientist Pope

“See those towers?” Costantino Sigismondi points to the two square Romanesque towers crowning Saint John Lateran. “We can imagine Gerbert up there looking at the stars.”

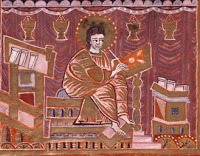

“See those towers?” Costantino Sigismondi points to the two square Romanesque towers crowning Saint John Lateran. “We can imagine Gerbert up there looking at the stars.”In 2008, while researching my biography of Gerbert of Aurillac, the French mathematician who became Pope Sylvester II, I visited Rome. I met my guide to the city, Costantino Sigismondi, through his website, where he had posted all of Gerbert’s known works. This year, on May 10, Sigismondi has organized a full day of lectures devoted to Pope Sylvester II at Rome’s Sapienza University. On May 12, a mass will celebrate the 1010th anniversary of Gerbert’s death. I wish I could join Sigismondi for the festivities. He's one of those rare people who brings light to the Dark Ages.

Sigismondi, an astrophysicist, teaches the history of astronomy at the University of Rome. In 2000, a friend reading Sky & Telescope chanced upon an article about “Y1K’s Science Guy,” Gerbert of Aurillac. She sent it to Sigismondi, who was astonished. Why hadn’t he known about The Scientist Pope? Sigismondi immediately contacted the Vatican and, with the pope’s support, began planning a series of lectures and events to commemorate the millennium of Gerbert’s pontificate (999-1003), including a grand requiem mass in the cathedral of Saint John Lateran in 2003.

Now we were in the square on the north side of the basilica; we turned to see an obelisk covered with hieroglyphics. “That wasn’t there when Gerbert was pope. We need to go to the Campo Marzio, close to the Pantheon. Ten years before Christ, Augustus put an obelisk there to make a sundial. One of the legends of Gerbert, you remember—William of Malmesbury tells it—is the story of Gerbert and a servant walking through the Campo Marzio, and Gerbert suddenly understands the Augustine obelisk. This is the story of the buried treasure.”

William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1120s, describes not an obelisk but “a statue … pointing with the forefinger of the right hand, and on its head were the words ‘Strike here.’” It was all battered with blows from men who had done the obvious. Gerbert found “quite another answer to the riddle. At midday with the sun high overhead, he observed the spot reached by the shadow of the pointing finger, and marked it with a stake.” He returned at night with a servant and, presumably a shovel. They quickly found themselves in “a vast palace, gold walls, gold ceilings, everything gold; gold knights seemed to be passing the time with golden dice, and a king and queen, all of the precious metal, sitting at dinner with their meat before them and servants in attendance; the dishes of great weight and price.” The palace was magically lit by a sparkling jewel; a golden boy stood opposite it, “holding a bow at full stretch with an arrow at the ready.” Gerbert’s servant, overcome with greed, snatched a golden knife. At once the figures came alive with a roar. The boy loosed his arrow and put out the light. And “had not the servant, at a warning word from his master, instantly thrown back the knife, they would both have paid a grievous penalty.” They covered their tracks and said no more about it.

William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1120s, describes not an obelisk but “a statue … pointing with the forefinger of the right hand, and on its head were the words ‘Strike here.’” It was all battered with blows from men who had done the obvious. Gerbert found “quite another answer to the riddle. At midday with the sun high overhead, he observed the spot reached by the shadow of the pointing finger, and marked it with a stake.” He returned at night with a servant and, presumably a shovel. They quickly found themselves in “a vast palace, gold walls, gold ceilings, everything gold; gold knights seemed to be passing the time with golden dice, and a king and queen, all of the precious metal, sitting at dinner with their meat before them and servants in attendance; the dishes of great weight and price.” The palace was magically lit by a sparkling jewel; a golden boy stood opposite it, “holding a bow at full stretch with an arrow at the ready.” Gerbert’s servant, overcome with greed, snatched a golden knife. At once the figures came alive with a roar. The boy loosed his arrow and put out the light. And “had not the servant, at a warning word from his master, instantly thrown back the knife, they would both have paid a grievous penalty.” They covered their tracks and said no more about it.If this story were set in Reims, I could pooh-pooh it as utter fantasy. But Rome? In 2005, archaeologists were using a coring drill to survey the foundations of Caesar Augustus’s palace on the Palatine Hill. Fifty feet down, the drill plunged into a void. Sending down a camera, the crew discovered a sacred grotto—a round, domed room about twenty-five feet high and twenty-five feet across, covered with mosaics of marble and seashell. In the soft light of the remote-sensing probe, they glittered like gold.

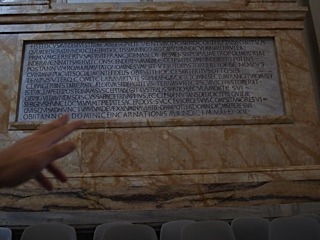

Whether or not Gerbert found buried treasure, if he understood how an obelisk worked as a sundial, he would have understood the Clementine Sundial in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. Sigismondi had demonstrated it to me that noon. The church is an architectural pastiche, the interior by Michelango, the exterior a ruined Roman bath. The meridian line of the sundial is not squared with the church—it was added later, the church being chosen for the purpose because of its stable Roman walls and suitable dimensions. The pinhole that lets in the sunlight was set into a great bronze sculpture of the arms of Pope Clement XI (1700-1721) that cuts into one of Michelangelo’s ornate arches. New marble mosaics were set into the floor to create the zodiac images that flank the line, which is made of brass.

Whether or not Gerbert found buried treasure, if he understood how an obelisk worked as a sundial, he would have understood the Clementine Sundial in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. Sigismondi had demonstrated it to me that noon. The church is an architectural pastiche, the interior by Michelango, the exterior a ruined Roman bath. The meridian line of the sundial is not squared with the church—it was added later, the church being chosen for the purpose because of its stable Roman walls and suitable dimensions. The pinhole that lets in the sunlight was set into a great bronze sculpture of the arms of Pope Clement XI (1700-1721) that cuts into one of Michelangelo’s ornate arches. New marble mosaics were set into the floor to create the zodiac images that flank the line, which is made of brass.“The meridian occurs in this line,” Sigismondi said, putting a blank sheet of white paper near the line so that the faint sun on this cloudy day was more visible. “It’s different for every day. It goes to 12:24 in February, comes back to 12:20 now in March. And back to 12 in October. This is the so-called equation of time. If you take this and put it to local noon time, noon”—when the image of the sun crosses the line—“equals halfway between dawn and sunset.

“If mass is at noon,” he added, “sometimes the transit will happen during mass. If mass is at 12:30, then the faithful can attend mass, the astronomer can do his work, and the faithful astronomer can do both. The priests here are very open. They moved the mass to 12:30 for this reason.” And every day that he works in the cathedral, Sigismondi also takes part in the 12:30 mass, volunteering to read the scripture and take the offerings.

“If mass is at noon,” he added, “sometimes the transit will happen during mass. If mass is at 12:30, then the faithful can attend mass, the astronomer can do his work, and the faithful astronomer can do both. The priests here are very open. They moved the mass to 12:30 for this reason.” And every day that he works in the cathedral, Sigismondi also takes part in the 12:30 mass, volunteering to read the scripture and take the offerings.“I am practically the resident astronomer of Santa Maria degli Angeli,” he said. He has held conferences and astronomy classes in the church; on a side table, surrounded by sacred literature for sale, is a one-euro pamphlet he wrote called “Astronomy in the Church.” The pamphlet gives his email address if anyone would like further information on this partnership between religion and science.

Sigismondi has also used the sundial for original scientific research. “I measure this meridian line with video cameras to take scientific information as accurate as possible. Looking at the sun, it is possible to measure all the parameters of the solar orbit with a precision difficult to achieve with a normal telescope. You can measure the angles of the sun with greater precision because there is no lens—there is no border effect. The border effect of a lens is remarkable. The pinhole, on the other hand, is aberrationless. The only abberation is due to the atmosphere.

“What’s the link between this meridian line and our Gerbert? There’s no real link, because this line was built seven centuries later.

“But it was built by a pope, by a successor of his, Clement XI. He became pope on November 23, 1700. By the first of January, the astronomers were already building this line for him. Only seventy years after the Galileo affair, the pope was building this scientific instrument in the church—and this instrument can distinguish between the Copernican system, with the earth going around the sun, and the Ptolemaic system, with the sun going around the earth. With this instrument of the pope’s, you can prove that the earth goes around the sun.

“But it was built by a pope, by a successor of his, Clement XI. He became pope on November 23, 1700. By the first of January, the astronomers were already building this line for him. Only seventy years after the Galileo affair, the pope was building this scientific instrument in the church—and this instrument can distinguish between the Copernican system, with the earth going around the sun, and the Ptolemaic system, with the sun going around the earth. With this instrument of the pope’s, you can prove that the earth goes around the sun.“And this was possible in Gerbert’s time. If you use only the duration of the seasons, then Ptolemy works. If you can see the image of the sun—as you can with this sundial—then Ptolemy fails.”

Sigismondi speculates that this kind of sundial was the sensational object that Gerbert made for Otto III in Magdeburg—what Thietmar of Merseburg called an horologium, a “time-keeper,” translated variously as an astrolabe, a nocturlabe, a clepsydra, a celestial sphere, or a sundial. “This kind of clock is very easily made by someone like Gerbert,” Sigismondi said, “someone brilliant who understood the idea of using a tube to observe the stars, someone who could make his spheres. A sighting tube is not so different from the type of camera obscura you have here. The function of the church is just to make a dark space so that the light coming through the pinhole can be seen.

“We can’t say that this is what Gerbert made at Magdeburg, but there is room to dream in the history of science. We can’t say he didn’t. And it’s something he could have done. It’s plausible. Gerbert was about four hundred years ahead of the contemporary people, scientists and scholars included. Many of them understood that he was really outstanding. He was very respected as pope. I would like to see him sainted, or at least blessed. Abbo was sainted, and Gerbert was better than Abbo.”

If anyone could do it, Sigismondi could. A self-proclaimed “faithful astronomer,” he is equally at home in his astrophysics laboratory and in the Vatican; his university website features a photo of him kneeling before the pope. An eager teacher, he had led me on an enthusiastic all-day tour of Rome, highlighting the priest who was carving a new sun to reconstruct a medieval armillary sphere much like the one Gerbert had made; the Jesuit who had originated the field of astrophysics; the pope who had studied the dimensions of the sun.

If anyone could do it, Sigismondi could. A self-proclaimed “faithful astronomer,” he is equally at home in his astrophysics laboratory and in the Vatican; his university website features a photo of him kneeling before the pope. An eager teacher, he had led me on an enthusiastic all-day tour of Rome, highlighting the priest who was carving a new sun to reconstruct a medieval armillary sphere much like the one Gerbert had made; the Jesuit who had originated the field of astrophysics; the pope who had studied the dimensions of the sun.The more time I spent with him, the more he seemed like Gerbert himself—Equally in leisure and in work we both teach what we know, and learn what we do not know. Or, perhaps like Gerbert’s beloved friend, the sweet solace of his labor, a man with the same first name: Costantino Sigismondi was Gerbert’s twenty-first century Constantine, who would keep the story of The Scientist Pope alive.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on May 08, 2013 03:31

May 1, 2013

Song of the Vikings Raffle Winner!

In my March 1 post I offered to raffle off an autographed copy of my book

Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths

. To enter, you had to answer the question, Who is the god of Wednesday and what does he have to do with this blog? Explain me to myself, I pleaded. I promised to print the best answers.

In my March 1 post I offered to raffle off an autographed copy of my book

Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths

. To enter, you had to answer the question, Who is the god of Wednesday and what does he have to do with this blog? Explain me to myself, I pleaded. I promised to print the best answers. Yesterday the names went into a hat and … Congratulations to Scott Isebrand! Scott is a most deserving winner, as you'll see when you read his answer below. There were some other great answers, too. Here are some of my favorites:

"I think you named it God of Wednesday because Odin was the wise, lonely wanderer."

"A storyteller with a wonderful horse... Gotten by quite different means, but I'm sure your horse is no less wonderful."

"You have found a kindred soul in Odin the Wanderer, as you have wandered far to pursue your craft, aided by Thought and Memory."

"I am fairly sure that you would also approve of the label 'the Odinic wanderer,' as you must surely have felt a tie to both Odin and Gandalf while making your treks through Iceland, walking in the here and now of today while seeing and feeling the spirit of northernness and ages long past all around you."

"I think any historian of Iceland and Norse literature is a kindred spirit to Odin, and willing to make sacrifices to gain knowledge."

"While perhaps best known as a battle god, Odin is also a god of inspiration, of poetry, of the bardic arts. It is he who inspires writers, musicians, and poets."

"Your blog is probably named God of Wednesday because you like Odin's attributes. You are a writer of stories that cause us to pause and think deeper about the true knowledge of the past and how it shouldn't be lost for the sake of our future."

"The god of Wednesday is Odin. The best publicist of the god of Wednesday is Snorri. And the best publicist of Snorri is Nancy Marie Brown."

"The god of Wednesday is Odin. The best publicist of the god of Wednesday is Snorri. And the best publicist of Snorri is Nancy Marie Brown.""Odin lives on in western consciousness thanks to Snorri. On Wednesdays, thanks to your efforts, we are all able to channel his wit and bravery."

"Without Snorri, we would know next to nothing about the god for whom Wednesday was named."

"Snorri ensured that the people of the north would inherit a rich tapestry that gives an insight into the minds of our predecessors--treasure worth much more than gold and silver."

"What I didn't know was that Snorri Sturluson was such an influence, if not the outright inventor, of the myths and stories surrounding the Norse gods. You have shown that this is some serious influence. Here is the most fantastic (and totally true) range of his influence. I traded a camera last week to a young Malaysian journalist working in Minnesota. I sent him a link to a story about me and my horse, Draugen. He knew what the name Draugen meant from playing video games. Being a bit older than you, I hadn't thought about the influence of Snorri's writing on this form of entertainment. Can you imagine what Snorri would think of that!"

"The irony that is not lost on me is that what we think we know about what the ancient Norse believed is evidently from the fervent imagination of Snorri Sturluson. Your critical analysis of the debt that western literature in general and Icelandic lore in particular owe to Snorri is well-stated in an entertaining manner. Your blog is the highlight of my Odin's Day!"

And finally, here is Scott Isebrand's tour-de-force:

And finally, here is Scott Isebrand's tour-de-force:"The god of Wednesday is Odin;

The Allfather;

Lord of the Æsir;

Foe of frost giants;

Co-killer of Ymir;

Co-maker of Midgard;

Ygg;

Son of Borr and Bestla;

Father of Thor

Bereft of Thor's brother, Baldr;

The avenged by Baldr's brother, Víðar;

First husband of Frigg;

Rider of eight-legged Sleipnir and wielder of straight-shafted Gungnir;

Lord of the golden ring and the far-seeing severed head of Mimir;

Shoulderer of Thought and Memories that fly away, pitch-plumed Hugin and Munin, his two ravens;

Feeder of Greed that flanks him, fiercely fanged Geri and Freki, his two wolves;

The willfully-one-eyed god;

Vegtam the Wanderer;

Hangtyr, god of the hanged;

God of the battle-slain and lord of the flying Valkyries who bear half of them to Valhalla;

Gamer of Gunnlöð;

Sly thief of the blood-born Skalds' Mead that makes men and women into poets;

Wōden of the Angles, Wôdan of the Saxons, Wôtan of the Germans; and, finally, Fenrir's feast.

What does the God of Wednesday have to do with the blogspot-born 'God of Wednesday'?

Everything!

For without him, there would be no Wednesdays!"

Thanks Scott. Hope you enjoy Song of the Vikings. You made my Wednesday.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on May 01, 2013 04:30

April 24, 2013

The Book of the Icelanders App

The press calls it the Incest App. It's the winner of a contest sponsored by DeCode Genetics, which oversees the Icelandic genealogy database called Íslendingabók, or "Book of the Icelanders" (also the title of the first history of Iceland, written in about 1120 by Ari the Learned).

The press calls it the Incest App. It's the winner of a contest sponsored by DeCode Genetics, which oversees the Icelandic genealogy database called Íslendingabók, or "Book of the Icelanders" (also the title of the first history of Iceland, written in about 1120 by Ari the Learned).The database was set up in the 1980s using Iceland's extraordinary genealogical records. DeCode matches it with health records and genetics data to research the causes of disease. As payback to the nation for using its heritage in this way, DeCode has made Íslendingabók freely available to anyone with an Icelandic kennitala, the equivalent of a Social Security number, to use to trace his or her ancestry back to the first settlers of Iceland in the late 800s.

Several of my Icelandic friends have shared their results with me. I have been warned (tongue-in-cheek, I hope), "Be careful what you say about Snorri Sturluson. He was my ancestor," for example.

The new app doesn't go back that far. If two Icelanders bump phones, it finds each kennitala, pulls up the records of their grandparents, and beeps if there's a match. (A future version might search back to great-grandparents.)

It's the bump and the beep that have the press excited. The app developers named it the "Incest Spoiler."

That provoked a bit of a rant from Icelandic writer Alda Sigmundsdottir on "The Iceland Weather Report" Facebook page. "I suppose it was a clever ploy to add the incest dimension--the guys who wrote it [the app] did that, and the international media gobbled it up, swallowed it whole, and are now ravenous for more," she wrote. "I probably shouldn't let it get on my nerves, but it totally does." If you don't know who your cousins are, she points out, it means you--and the record-keepers at Íslendingabók--don't know who your father is, and no app is going to help you.

What Is Incest?

What Is Incest?But there's another question to ask. Is sleeping with your cousin incest? It depends who (and when) you ask. Incest is a cultural phenomenon.

Sex with your father, mother, brother, or sister is uniformly considered incest--and wrong.

But in much of the U.S. today, you can not only sleep with your cousin, you can marry him or her: It's legal in 25 states. It's not even thought to be a bad idea for cousins to have kids. According to a 2009 article in the New York Times, "For the most part, scientists studying the phenomenon worldwide are finding evidence that the risk of birth defects and mortality is less significant than previously thought." Laws preventing cousin-marriages, says one researcher are "rooted in myth" and amount to "genetic discrimination akin to eugenics or forced sterilization."

Those myths go back to Roman times, but they took a bizarre turn in the Dark Ages when the Christian Church decided to take control of marriage and make it a sacrament, not just an economic transaction between two families.

Through the 700s, the Church followed Roman law: Marriages "within four degrees" were incestuous, and so forbidden. You counted the degrees by counting up from the bride to the common ancestor and then back down to the groom. First cousins equal four degrees.

In the early 800s, the Church changed the definition of incest from four degrees to seven. It also changed the way degrees were counted. Now you counted in only one direction: from the bride (or groom) back to the shared ancestor. Seven degrees meant that it was incest if the couple shared a great-great-great-great-great-grandparent. In the late 900s, this caused a crisis for King Robert the Pious of France: Under these rules, there was no woman of sufficient rank in Europe whom he could legally wed. So he ignored the rules, married his second cousin, and was excommunicated. He ignored that too.

Snaelaug's Story

In Iceland, the Church's rules on incest were not enforced until the late 1100s, but by then they were even stricter. I give one example in my book Song of the Vikings, a biography of the chieftain and writer Snorri Sturluson.

One of Snorri's mistresses was Gudrun, whom he called in a poem "lovely as a swan." Gudrun was the illegitimate daughter of a woman named Snaelaug, who had been happily married to Snorri's uncle Thord Bodvarsson—until Bishop Thorlak of Skalholt intervened.

Snaelaug had given birth to Gudrun quite young, saying the baby's father was a cowherd. Her own father, a priest, forgave her and sent her away to a relative's, where she met young Thord, who was the future chieftain of Gard and Snorri's uncle on his mother's side. Thord and Snaelaug fell in love. Thord sued for her hand in marriage, and with their families' approval they were wed. They were very happy and had three sons.

In 1183, when Snorri was five and Gudrun at least three, news came from Norway that a young man named Hreinn had died, and Snaelaug let it slip that Hreinn, not the cowherd, was really Gudrun's father.

Hreinn and Thord were third cousins: They shared a great-great-great-grandfather. Even in a culture as obsessed with genealogy as medieval Iceland's, this did not set off alarm bells in Snaelaug's head. Yet according to the Church's byzantine incest laws, it meant that she and Thord could not be married. Their relationship was incestuous because of her previous one-night-stand with her husband's third cousin.

Hreinn and Thord were third cousins: They shared a great-great-great-grandfather. Even in a culture as obsessed with genealogy as medieval Iceland's, this did not set off alarm bells in Snaelaug's head. Yet according to the Church's byzantine incest laws, it meant that she and Thord could not be married. Their relationship was incestuous because of her previous one-night-stand with her husband's third cousin.Snaelaug's father, a priest who should have known these laws, did nothing about it. For this he was called on the carpet by Bishop Thorlak. The soon-to-be-sainted Thorlak "was so inspired by faith in God," a saga says, that he marched up to the Law Rock during the yearly parliament at Thingvellir "with all his clergy and swore in public that this marriage contract was contrary to the Law of God. He then named witnesses, declaring the union null and void." He excommunicated "all the parties to the contract" and declared that any children Thord and Snaelaug had after that moment would be illegitimate.

They argued. They pleaded. They ignored the bishop. But finally they had to part. Thord went home to his family farm of Gard, while Snaelaug raised her children at her family farm of Baer. From Baer to Snorri’s estate of Borg was about ten miles. Since his uncle Thord had given Snorri half his chieftaincy, the two men were in close contact. Snorri had ample occasion to travel to Baer to meet with his uncle—and to be smitten with love-sickness one day when he walked in upon slender Gudrun combing her hair.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And don't forget to enter the raffle for a free, autographed copy of Song of the Vikings. I'll be announcing the winner on May 1. For details, click here.

Published on April 24, 2013 07:49

April 17, 2013

The Saga of Oddny Island-Candle

I'm thinking about riding horses today--in Iceland. With my friend Guðmar Pétursson and the company America2Iceland, I'm leading a trek this June based on my book Song of the Vikings. We'll be riding tracks known to the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain and writer Snorri Sturluson, from his estates of Reykholt and Borg.

I'm thinking about riding horses today--in Iceland. With my friend Guðmar Pétursson and the company America2Iceland, I'm leading a trek this June based on my book Song of the Vikings. We'll be riding tracks known to the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain and writer Snorri Sturluson, from his estates of Reykholt and Borg.One place we might go is the island of Hjörsey, across the tidal sands from Borg. There's a great story about Hjörsey--one of those medieval Icelandic tales that's just begging to be turned into a psychological novel. It's the story of Oddny Island-Candle, the heroine in The Saga of Bjorn the Hitardal-Champion.

In the days of King Olaf the Saint, who reigned from 1015-1030, there was a man named Thordur. He lived at Hitarnes, a little north of Borg in the west of Iceland. Thordur was a great skald, or Viking poet, the saga says, although his verses tended to be mocking and spiteful.

At Borg itself lived a young man named Bjorn. He was the great-grandson of the first settler of Borg, Skalla-Grim, whose father was reputed to be a werewolf. Skalla-Grim's famous son, the poet and berserk Egil, has a whole saga of his own (probably written by Snorri Sturluson). Bjorn was descended from Egil's sister, Saeunn.

Horses play a major role in this saga, as they do in many of the Icelandic sagas. The sagas, which take place between the settlement of Iceland in 870 and about 1050, but were written down in the 1200s and 1300s, create a quirky but believable picture of a country in which complex laws, a convoluted sense of duty to one’s family and friends, and a strong sense of personal honor let people live with a good deal of freedom and comfort in a harsh environment.

Feuds are a common occurrence, and often horses are involved in one way or another. Such is the case in The Saga of Bjorn the Hitardal-Champion.

Feuds are a common occurrence, and often horses are involved in one way or another. Such is the case in The Saga of Bjorn the Hitardal-Champion.Bjorn, the saga says, was a tall youth, freckle-faced, with curly hair, a red beard, and handsome features, a good fighter even though his eyesight was weak. He was in love with a girl named Oddny, who lived nearby on the island of Hjörsey. She was so beautiful she had the nickname Island-Candle.

Bjorn asked Oddny Island-Candle to marry him and, with the consent of her father, they were betrothed. Bjorn then went off to Norway to seek his fortune, as did many young Icelanders in the Saga Age, with the promise that Oddny would wait for him for three years.

In Norway Bjorn fell in with Thordur, the poet from Hitarnes. He was about fifteen years older than Bjorn. One night just before Thordur left to go back home to Iceland, he and Bjorn sat up late drinking, and the subject of Oddny Island-Candle came up.

Two years passed. Thordur, in Iceland, learned that Bjorn had been wounded in a duel. He paid some Norwegian merchants to spread the news that Bjorn had been killed, then he went to ask for Oddny’s hand in marriage. Her father, a wealthy man, put him off. But when Bjorn didn’t arrive at the appointed time for the wedding, Oddny and her father assumed he must truly be dead. Saddened but practical, Oddny married Thordur instead. She was content with her choice until Bjorn turned up, a year too late, having recovered from his wounds. “I thought you were a good man,” she said to her husband, “but you are full of lying and falsehoods.”

Bjorn’s joyful father gave him a stallion called Hvitingur (White One) and his two white colts—a great treasure, the saga says—to take his mind off the loss of his beloved Oddny. Bjorn pastured one colt with a herd of black mares and the other with all chestnuts to see what mix of colors might result. But horse breeding couldn’t keep him away from Oddny. Year by year, the insults and attacks escalated between the two men.

Bjorn’s joyful father gave him a stallion called Hvitingur (White One) and his two white colts—a great treasure, the saga says—to take his mind off the loss of his beloved Oddny. Bjorn pastured one colt with a herd of black mares and the other with all chestnuts to see what mix of colors might result. But horse breeding couldn’t keep him away from Oddny. Year by year, the insults and attacks escalated between the two men.At the height of the feud, Thordur invited Thorsteinn Kuggason, a rich and well-respected man from northern Iceland, to a midwinter feast. On his way, Thorsteinn was caught in a blizzard and forced to take refuge at Bjorn’s house. By the time the weather broke, he had agreed to try to make peace between Bjorn and Thordur. To seal this agreement, Bjorn gave Thorsteinn a magnificent gift of four horses: a white stallion (one of Hvitingur’s colts) and three chestnut mares. Thorsteinn asked Bjorn to keep the horses for him until he saw how the peacemaking went. Ironically, it was in the springtime, as he was trimming the white stallion’s mane to present him to Thorsteinn Kuggason, that Bjorn was set upon by Thordur and killed.

Bjorn’s is a classic saga, spun of honor and friendship, love and betrayal, all set against the harsh reality of medieval life. I am always particularly moved by Oddny’s role: When she learned of Bjorn’s death, she fell down in a faint. From then on, though she lived many years, she was out of her wits. She was only happy on horseback, the saga says, with her husband leading her about.

This story appears in my book A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse and, in 1998, I published a version of it in The Icelandic Horse Quarterly, the official magazine of the U.S. Icelandic Horse Congress. Visit the congress’s website (www.icelandics.org) to read a free copy and learn more about Icelandic horses today, or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson’s video blogs, Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses (http://www.lifewithhorses.com/). If you're really adventurous, come riding with me in Iceland this June. You can book the trip online at either America2Iceland.com or Ishestar.is.

This story appears in my book A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse and, in 1998, I published a version of it in The Icelandic Horse Quarterly, the official magazine of the U.S. Icelandic Horse Congress. Visit the congress’s website (www.icelandics.org) to read a free copy and learn more about Icelandic horses today, or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson’s video blogs, Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses (http://www.lifewithhorses.com/). If you're really adventurous, come riding with me in Iceland this June. You can book the trip online at either America2Iceland.com or Ishestar.is.Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on April 17, 2013 13:07

April 10, 2013

The Real Ragnar Lothbrok

Floki: "Ragnar Lothbrok challenges you to meet him in single combat."

Floki: "Ragnar Lothbrok challenges you to meet him in single combat."Earl Haraldson: "Ragnar Lothbrok has a very high opinion of himself."

Floki: "Well, he is descended from Odin."

--from "The Vikings," episode 6, as reviewed on medievalists.net

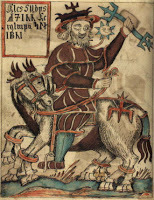

Ragnarr Loðbrók, to give his name the proper spelling, has become America's favorite badass Viking, thanks to the History Channel's exciting series, "The Vikings." But who was he really? Dr. Elizabeth Ashman Rowe has the answers. Rowe is University Lecturer in Scandinavian History of the Medieval Period at the University of Cambridge in England and author of a scholarly study published in 2012, Vikings in the West: The Legend of Ragnarr Loðbrók and His Sons.

In the preface, she writes: "The Viking king Ragnarr Loðbrók and his sons feature in a variety of medieval stories, all of them highly dramatic." In a French version, he is a noble king in Denmark, father of a fearsome Viking who ravages France. In an English story, he "wickedly inflames" his three sons with envy for the English King Edmund, provoking the Danish invasion of England and Edmund's martyrdom.

Snorri Sturluson, subject of my book Song of the Vikings, wrote one of the 32 known Icelandic tales about Ragnarr. To Snorri, Ragnarr was famous as the first Norwegian king to keep a court poet, or skald. He was "the conqueror who established the definitive boundaries of the Scandinavian kingdoms," Rowe writes, "and the symbol of the ancient heroism that would be eclipsed by the new heroism of the Icelanders."

Concludes Rowe, "In short, Ragnarr and his sons were ciphers to which almost any characterization could be attached"--as the History Channel has effectively proved.

Was there a real Ragnarr Loðbrók? Rowe says no: "I do not think that there was ever a historical figure known as 'Ragnarr Loðbrók.'" Mostly it's the nickname she's leery of, noting that "the deeds and fate" of an "extraordinarily ferocious" Danish Viking known as Reginheri, who attacked Paris in 845, hanged 111 Christians, and died of illness soon afterwards, "may have given rise to stories about someone named Ragnarr, but there is absolutely no contemporary evidence that he was nicknamed Loðbrók."

Was there a real Ragnarr Loðbrók? Rowe says no: "I do not think that there was ever a historical figure known as 'Ragnarr Loðbrók.'" Mostly it's the nickname she's leery of, noting that "the deeds and fate" of an "extraordinarily ferocious" Danish Viking known as Reginheri, who attacked Paris in 845, hanged 111 Christians, and died of illness soon afterwards, "may have given rise to stories about someone named Ragnarr, but there is absolutely no contemporary evidence that he was nicknamed Loðbrók."He didn't get his nickname until after he died--Loðbrók first appears in two sources, one Icelandic and one from France, in about 1120--and there are several explanations of what it means.

An English writer in about 1150 said it meant "loathesome brook"--just what it sounds like.

But in Old Norse, the nickname would have been understood as "hairy breeches" or "shaggy trousers." The Icelander who wrote Ragnar's Saga in the 13th century explained that Ragnarr got his nickname from the pants he put on to protect himself when fighting a poison-breathing serpent (or dragon): cowhide pants boiled in pitch and rolled in sand.

Professor Rowe has a better explanation. As I've mentioned, the real Ragnarr Loðbrók, the ferocious Reginheri, died of illness soon after attacking Paris in 845. And not just any illness. Reginheri died of dysentery. As one account in Latin explains, after Ragnarr returned to the Danish court of King Horik he suffered terribly from diarrhea: "diffusa … sunt omnia viscera ejus in terram" (which Rowe helpfully translates: "all his entrails spilled onto the ground.")

Professor Rowe has a better explanation. As I've mentioned, the real Ragnarr Loðbrók, the ferocious Reginheri, died of illness soon after attacking Paris in 845. And not just any illness. Reginheri died of dysentery. As one account in Latin explains, after Ragnarr returned to the Danish court of King Horik he suffered terribly from diarrhea: "diffusa … sunt omnia viscera ejus in terram" (which Rowe helpfully translates: "all his entrails spilled onto the ground.")Concludes Rowe: "I suggest that it was a similar report--one describing his diarrhea in terms of his feces-stained breeches--that gave rise to the posthumous nickname loðbrók. Ragnar's Saga's explanation ot the nickname loðbrók as derived from garments boiled in pitch comes startlingly close to reality, for one can imagine an onlooker at the court of King Horik telling someone later that Reginheri's breeches looked black and sticky, as though they had been boiled in pitch."

So alongside my favorite Viking name, Eystein Foul-Fart, we can now place Ragnar Shitty-Pants. And that's what their friends called them.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And don't forget to enter the raffle for a free, autographed copy of Song of the Vikings. I'll be announcing the winner on May 1. For details, click here.

Published on April 10, 2013 06:20

April 3, 2013

Wagner and Iceland

Wagner's grand opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen returns to the Metropolitan Opera in New York on Saturday in Robert LePage's excitingly technological production. We all know the story, with its stirring Wotan, evil dwarf Alberich, tragic valkyrie Brünnhilde, heroic Siegfried and the cruel dragon he slays. It's the German National Epic.

Wagner's grand opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen returns to the Metropolitan Opera in New York on Saturday in Robert LePage's excitingly technological production. We all know the story, with its stirring Wotan, evil dwarf Alberich, tragic valkyrie Brünnhilde, heroic Siegfried and the cruel dragon he slays. It's the German National Epic.Even if Wagner's main sources were not ultimately German.

They were Icelandic.

Who is Wotan? None other than the God of Wednesday, Odin. And if you've been reading this blog for any length of time, you'll know that the main source for stories of Odin is the 13th-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson.

In a well-known letter from 1856, Wagner jotted down the names of ten books that inspired him to write The Ring.

Number three was Jacob Grimm’s German Mythology of 1835, which cites Snorri Sturluson's Edda, the Poetic Edda, Snorri's Heimskringla, and other Icelandic sagas. (In fact, if you take the Icelandic sources out of German Mythology, all that's left is an empty shell.)

Number three was Jacob Grimm’s German Mythology of 1835, which cites Snorri Sturluson's Edda, the Poetic Edda, Snorri's Heimskringla, and other Icelandic sagas. (In fact, if you take the Icelandic sources out of German Mythology, all that's left is an empty shell.)Number four on Wagner's list was "Edda" (like most people at the time, he didn't discriminate between Snorri's Edda and the Poetic Edda).

Number five was the Icelandic Volsunga Saga, which Snorri did not write, but which was written in Iceland at roughly the same time Snorri was active. (Some scholars say it is earlier than Snorri's sagas, some say later.)

Number ten on Wagner's list was Heimskringla, Snorri's collection of sixteen sagas about the kings of Norway.

Wagner made this list just after completing Das Rheingold and Die Walküre; he wouldn’t finish Siegfried until 1871 and Götterdämmerung until 1874. The first full performance of the four-opera cycle was in 1876.

It was twenty-five years in the making. The idea for a cycle of operas based on Siegfried—or Sigurd—the Dragon-slayer and the accursed gold ring of the dwarves came to Wagner in 1851. A German translation of the Poetic Edda and some tales from Snorri’s Edda, he wrote, “drew me irresistibly to the Nordic sources of these myths,” the most expansive being the Icelandic Volsunga Saga.

Wagner had, three years before, written a libretto called Siegfried's Death based on the medieval German Nibelungenlied, or "Song of the Nibelungs." This libretto, according to Edward Haymes in his book Wagner's Ring in 1848, is quite similar to Götterdämmerung; "in fact," Haymes told me, "some of the scenes are taken over verbatim."

Wagner had, three years before, written a libretto called Siegfried's Death based on the medieval German Nibelungenlied, or "Song of the Nibelungs." This libretto, according to Edward Haymes in his book Wagner's Ring in 1848, is quite similar to Götterdämmerung; "in fact," Haymes told me, "some of the scenes are taken over verbatim."But Wagner wasn't satisfied. Only after he had discovered what he called "the Nordic sources," Wagner said, "did I recognise the possibility of making him [Siegfried] the hero of a drama; a possibility that had not occurred to me while I only knew him from the medieval Nibelungenlied."

The German "Song of the Nibelungs" was written at about the same time as Snorri was writing his Edda in Icelandic (c. 1220-1241). Some of the same characters appear: Sigurd the Dragon-Slayer (Wagner's Siegfried), Brynhild (Brünnhilde), Gudrun (Gutrune). But half of the "Song" takes place after their deaths; it has no counterpart in Wagner's Ring.

And much that Wagner loved about the Sigurd story exists only in the Icelandic sources: the dragon, the ring, the valkyries, the sibyl; the characters of Odin and the other gods, the giants, the dwarfs, Idunn’s apples, the rainbow bridge, the magical helmet, Valhalla, the Twilight of the Gods.

In his 2003 book, Wagner and the Volsungs: Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen (which is online here: http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Wagner.pdf), Icelandic scholar Arni Björnsson concludes that 80 percent of Wagner’s motifs are Icelandic. Five percent are German. Most of the remaining 15 percent are shared, appearing in both the Icelandic and German sources, though some—like the Rhine Maidens—are Wagner’s own invention, for he was nothing if not creative.

In his 2003 book, Wagner and the Volsungs: Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen (which is online here: http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Wagner.pdf), Icelandic scholar Arni Björnsson concludes that 80 percent of Wagner’s motifs are Icelandic. Five percent are German. Most of the remaining 15 percent are shared, appearing in both the Icelandic and German sources, though some—like the Rhine Maidens—are Wagner’s own invention, for he was nothing if not creative.Like Snorri, Wagner took bits and pieces of myth and made of them something magical.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And don't forget to enter the raffle for a free, autographed copy of Song of the Vikings. For details, click here.

Published on April 03, 2013 08:08

March 25, 2013

Valkyrie or Shield-Maiden?

Last December, a man named Morten Skovsby found a small face peering up at him from a lump of frozen dirt. He'd been working with a group of amateur archaeologists using a metal detector near the village of Hårby in Denmark. His find, cleaned up, was an intricately detailed amulet made of gilded silver, about an inch tall, in the shape of a beautiful woman with long hair twisted into a ponytail. She carried a sword and shield.

Last December, a man named Morten Skovsby found a small face peering up at him from a lump of frozen dirt. He'd been working with a group of amateur archaeologists using a metal detector near the village of Hårby in Denmark. His find, cleaned up, was an intricately detailed amulet made of gilded silver, about an inch tall, in the shape of a beautiful woman with long hair twisted into a ponytail. She carried a sword and shield.She was immediately dubbed a "valkyrie." Why?

Because Snorri Sturluson, writing between 1220 and 1241, described valkyries as semi-goddesses with shield and sword (or spear) who accompanied dead heroes to Odin's feast-hall,Valhalla, and there served them mead.

In Heimskringla, Snorri quoted a poem by Eyvind Skald-spoiler (his nickname might mean "plagiarist") about the death of King Hakon the Good in 960. Although Hakon was a Christian king, the poet pictures him, not meeting St Peter at the Pearly Gates, but being carried off by valkyries to Valhalla. In Erling Monsen's translation, it reads:

Gauta-Tyr sent the Valkyries / Gondul and Skogul / To choose amonst the kings / Which of Yngvi’s race / Should go to Odin / And be in Valhalla … Gondul said / As she took a spear shaft, / “The Aesir’s following grows, / When Hakon the High / Goes with so great an army / To the burg of the gods.” The king heard / What the battlemaids said, / Those quick horsewomen, / They were ready to strike, / As they sat helmeted, / With shields by their side…. Said the rich Skogul, / “Gondul and I shall ride / To the gods’ green home / To tell Odin / That quickly the prince / Comes himself to see him.” “Hermod and Bragi,” / Said the war father Odin, / “Go forth to meet Hakon, / For that warrior king / Is called hither to the hall.”…

Note that Eyvind doesn't call these battlemaids beautiful. Snorri doesn't either, in so many words. But by making being served mead by a valkyrie one of the perks of dying in battle, as Snorri does when describing Valhalla in his Edda, he makes it pretty easy for later readers to make that assumption.

It's not the only possibility. Eyvind, in fact, is in the minority when he makes the valkyries dignified horsewomen.

Poems and sagas written before--and after--Snorri's time describe the valkyries as monsters. They are troll women of gigantic size who ride wolves and pour troughs of blood over a battlefield. They row a boat through the sky, trailing a rain of blood. They are known by their “evil smell.”

In the part of Sturlunga Saga written by Snorri's nephew Saga-Sturla in the 1270s, and in which Snorri plays a major role, we learn of the dream of a man named Haflidi Hoskuldsson. According to Julia McGrew's translation:

"In the winter after Christmas he dreamed … he was in Fagraskogar and seemed to be looking up along Hitardal, where he saw a group of men riding down from inland. A woman rode at the head of their company, large and evil-looking, in her hand a cloth which hung down in tatters and dripped blood. Another group was coming against them from Svarfhol; they met one another west of Hraun, and fought. The woman then brandished the cloth over each man’s head, and when the ragged ends touched a man’s neck she jerked off his head. She said:

I move with bloody cloth, I strike men into fire, I laugh when I see them go To that loathly place I know."

Snorri didn’t care for that kind of monstrous valkyrie. I think it's a reflection of the popularity of his works--over those of his nephew, among others--that the image of the valkyrie we hold in our heads today so closely matches that of the little gilded silver amulet Morten Skovsky found in Hårby last December.

But there's another assumption we make when calling this amulet a valkyrie. Valkyries, all the poets and saga-writers agree, are not human. They are semi-goddesses--or trolls--but not real women. Why could this little amulet not depict a real woman? A true shield-maiden?

There are examples of women warriors in the sagas, too. The most famous is Hervor who, in an extremely spooky poem known as "The Waking of Angantyr," travels to the isle of Samsey to conjure her dead father up from his grave and get his sword, Tyrfing, which was made by the dwarfs. In Patricia Terry's translation, it says:

Now she saw the fire from the grave mounds and the living dead standing outside. She went toward then and was not frightened, passing through the fire as if it were smoke until she came to the berserks' graves. Then she said: … "May you writhe within your ribs, your barrow an anthill where you rot, unless you let me wield Dvalin's weapon--why should dead hands hold that sword?"

Replies her father, "You are not at all like other people if you go to grave-mounds at night, helmed, in ring-mail, spear in hand, to stand here, warlike, and wake us in our halls."

Says Hervor, "Men always thought me human enough before I set out to seek you here."

Before this amulet was found at Hårby, as Christopher Abram points out in his 2011 book, Myths of the Pagan North, other images have been labeled "valkyries." Writes Abram, "there has been a tendency to identify any female figure on an artefact found in a grave as a valkyrie: it is supposed that these objects were supposed to symbolize the dead person’s passage to Valhalla, or helped ensure it. Yet these so-called valkyries are most often found in women’s graves—the graves of people who would not go to Valhalla, which was reserved for the bravest and mightiest of (male) fighters. These female figures are sometimes depicted holding a cup. From the myths we know that one of the roles played by the valkyries was to serve mead or beer in Valhalla; but high-status women were also expected to honor their guests with drink here on earth. This depiction could, in other words, relate to a perfectly ordinary aspect of a woman’s life, rather than to the hyper-masculine cult of Odin."

Could it not also be true that carrying a sword and shield was "a perfectly ordinary aspect of a woman's life" in the Viking Age, and we've just been too biased against the idea of real women warriors to accept it?

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on March 25, 2013 12:45

March 20, 2013

A Thin Place in Iceland

“For me Iceland is holy earth. This memory is background for everything I do. Iceland is the sun which colours the mountains without being there and gone over the horizon.”

“For me Iceland is holy earth. This memory is background for everything I do. Iceland is the sun which colours the mountains without being there and gone over the horizon.”In 1937, the American poets W.H. Auden and Louis MacNeice went to Iceland. They wrote about it in Letters from Iceland, a collection of poems, prose, photographs, charts, graphs, you name it. Auden also took time to chat with Matthias Johannessen and provided the Icelandic poet and newspaper editor with those three sentences, sentences that have echoed in my head ever since I read them in the magazine Iceland Review in 1987, the year after my first visit to Iceland.

In a March 2012 essay in the Sunday New York Times that I clipped out and saved, writer Eric Weiner evokes “thin places”—“places that beguile and inspire, sedate and stir, places where, for a few blissful moments I loosen my death grip on life, and can breathe again…. They are locales where the distance between heaven and earth collapses and we’re able to catch glimpses of the divine, or the transcendent or, as I like to think of it, the Infinite Whatever.”

It's obviously a hard topic to put into words, but I think I know what Weiner is getting at. He traces the phrase “thin places” to Celtic Christianity. George Macleod, the founder of the Iona Community on the Scottish island of that name, is generally credited with bringing the concept into modern times—to the extent that you can now take “thin places tours” to catch glimpses of a divine that is decidedly Christian. (See the blog “Thin Places” at www.thinplace.net.)

I’m more interested in “the Infinite Whatever.” I catch glimpses of it regularly in Iceland, most often beside the hill named Helgafell, or Holy Mountain, by the first settler on the peninsula. According to the medieval Icelandic Eyrbyggja Saga, “Thorolf gave the name Thor’s Ness to the region between Vigra Fjord and Hofsvag. On this headland there is a mountain held so sacred by Thorolf that no-one was allowed even to look at it without first having washed himself, and no living creatures on this mountain, neither man or beasts, were to be harmed unless they left it of their own accord. Thorolf called that mountain Helga Fell and believed that he and his kinsmen would go into it when they died.”

I’m more interested in “the Infinite Whatever.” I catch glimpses of it regularly in Iceland, most often beside the hill named Helgafell, or Holy Mountain, by the first settler on the peninsula. According to the medieval Icelandic Eyrbyggja Saga, “Thorolf gave the name Thor’s Ness to the region between Vigra Fjord and Hofsvag. On this headland there is a mountain held so sacred by Thorolf that no-one was allowed even to look at it without first having washed himself, and no living creatures on this mountain, neither man or beasts, were to be harmed unless they left it of their own accord. Thorolf called that mountain Helga Fell and believed that he and his kinsmen would go into it when they died.”The first time I went to Iceland, in 1986, I went to see Helgafell. I was drawn to it, like many visitors, by the sagas. And I have gone back to Helgafell every time I’ve been in Iceland since. I’ve met four generations of the family who farms beneath the hill. I’ve grieved with them over deaths and rejoiced over births. I’ve written them numerous letters, never receiving a reply until Facebook was invented. Now we’re in touch nearly every day.

Helgafell is to me, as Iceland was to Auden, “holy earth.” In Weiner’s term, it is my “thin place.”

I recently stumbled upon a 2010 paper in the online academic journal Limina that helped me understand just why it is so. The author, Carol Hoggart, a saga scholar and (if I can trust Google) a Romance writer, discourses on “three ways in which the family sagas inscribed cognitive maps over Iceland.” (You can find her paper, "A Layered Landscape," at medievalists.net.) Hoggart takes as her starting point, she says, “a notion that humans cannot understand their environment until it is cast in human terms.” The sagas, she continues, “portray a gradual filling up of landscape with human meaning” and “saga and land act to magnify each other’s impact.”

I recently stumbled upon a 2010 paper in the online academic journal Limina that helped me understand just why it is so. The author, Carol Hoggart, a saga scholar and (if I can trust Google) a Romance writer, discourses on “three ways in which the family sagas inscribed cognitive maps over Iceland.” (You can find her paper, "A Layered Landscape," at medievalists.net.) Hoggart takes as her starting point, she says, “a notion that humans cannot understand their environment until it is cast in human terms.” The sagas, she continues, “portray a gradual filling up of landscape with human meaning” and “saga and land act to magnify each other’s impact.”She seems a little dismissive of the idea, pointing out that, “So convincing has this process been that people still look to find a medieval saga-landscape in modern Iceland, despite evidence in the Íslendingasögur [the medieval texts] themselves of change since the tenth century.” Some farmsteads, she notes, were given new names even in saga times.

I think she’s missed the point—though she makes it herself when she adds, again a little dismissively, “The terrain is seen positively to glow with an identity sourced from medieval texts.”

It does. I’ve seen Helgafell glow. It glows with the long, slanting, midnight sun, of course. But it also glows with meaning. Helgafell is a thin place to me not because the first settler, Thorolf, saw its immanent holiness, as Hoggart puts it. Helgafell is a thin place to me because it connects me to an otherworld of story.

Stories from the tenth century drew me there: the time the north side of Helgafell opened up like doors, and the shepherd saw the god Thor feasting inside the hill. The time when 14-year-old Snorri tricked his uncle into selling him the farm cheap. When the same Snorri traded the farm to Gudrun the Fair to make peace. When Gudrun saw the ghost of her drowned husband in front of the church, or when she dug up the sorceress’s grave.

But stories from the last thirty years keep me coming back: the time we sat around the coffee table telling stories from the sagas. The time we went to Flatey together. When we put up the hay, went horseback riding, gathered eiderdown, found the raven’s nest. The time I came back from a walk with my pockets filled with sparkling stones and my hair braided with seagull and raven feathers. The time I wrote a story about it.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And don't forget to enter the raffle for a free, autographed copy of Song of the Vikings. For the details on how to enter, click here.

Published on March 20, 2013 07:04

March 13, 2013

Choosing a Pope in the Viking Age

As ABC News reported, "The Italian media is portraying the Vatican political culture as being equally depraved, drenched in ambition, wine and pheromones [as Italian president Sylvio Berlusconi's reelection campaign]. … The Rome papers are full of reports that sound like the plot of Dan Brown novel, starting with a shadowy Vatican dossier supposedly detailing a gay sex and blackmail scandal involving the curia."

As ABC News reported, "The Italian media is portraying the Vatican political culture as being equally depraved, drenched in ambition, wine and pheromones [as Italian president Sylvio Berlusconi's reelection campaign]. … The Rome papers are full of reports that sound like the plot of Dan Brown novel, starting with a shadowy Vatican dossier supposedly detailing a gay sex and blackmail scandal involving the curia."All I can say is that it was worse a thousand years ago. Much worse. I wrote The Abacus and the Cross because I wanted to know what popes were like in the Viking Age, especially around the year 1000. What I learned surprised me. In addition to all the positive things I chronicle in the book, I found enough depravity, ambition, and pheromones circling around the representative of Saint Peter to support the Italian media's current view. I also found astonishing brutality, and violence equal to anything the Vikings are said to have done.

Tenth-century popes were not the powerful religious leaders of today. They were political pawns, not elected (there was no college of cardinals in those days) so much as backed by the biggest army. For much of the century the papacy was influenced by the mercurial Roman noblewoman Marozia. She was mistress of Pope Sergius III (904-11), murderer of John X (914-28), and mother of John XI (931-35).

Her grandson, John XII (955-63), was both pope and Prince of Rome until he double-crossed Otto I, whom he had just crowned Emperor. At a synod in Rome, John XII was accused of sacrilege, simony, perjury, murder, adultery, and incest, and deposed. He excommunicated the members of the synod, and when he caught three of them, he flogged one, cut off another’s right hand and the third’s nose and ears. Otto I's army marched on Rome, but before they arrived John was “stricken by paralysis in the act of adultery” and died.

Otto’s candidate to be the next pope, Leo, wasn’t even a priest. The Romans chose Benedict, a deacon, who was well qualified. He was “attacked by Leo, aided by the emperor,” a contemporary wrote. “Besieged, made prisoner, and deposed, he was sent in exile to Germany,” and Otto appointed John XIII, a bishop and, incidentally, Marozia’s nephew. He was captured by a rival faction, but escaped. The emperor hanged the conspirators, and John XIII went on to have a successful papacy and a natural death.

His successor, chosen by Emperor Otto II, was strangled by supporters of his rival, Boniface VII. When Otto invaded the city, Boniface fled (first robbing the Vatican treasury), and Otto oversaw the appointment of John XIV. He lasted only until Emperor Otto II died in 983. Then Boniface returned from exile and and threw John XIV into the Castel Sant’Angelo where, according to one report, he starved to death. When Boniface VII himself died a year later, his body was dragged through the streets of Rome by a mob.

His successor, chosen by Emperor Otto II, was strangled by supporters of his rival, Boniface VII. When Otto invaded the city, Boniface fled (first robbing the Vatican treasury), and Otto oversaw the appointment of John XIV. He lasted only until Emperor Otto II died in 983. Then Boniface returned from exile and and threw John XIV into the Castel Sant’Angelo where, according to one report, he starved to death. When Boniface VII himself died a year later, his body was dragged through the streets of Rome by a mob.The nobles of Rome replaced him with a Roman nobleman. This John XV reigned 11 years by carefully balancing the desires of Crescentius of the Marble Horse, Prince of Rome, with those of the empresses Theophanu and Adelaide, then regents for the child-emperor Otto III.

John XV died suddenly (though naturally) while the teenaged Otto III was on his way to Rome to be crowned Emperor. Otto quickly nominated his cousin to become Gregory V in 996. Four months after Otto III took his army back to Germany, Gregory was chased out of Rome by a mob.

The antipope who replaced him was John Philagathos, abbot of Nonantola, archbishop of Piacenza, and chancellor of Italy.

Philagathos’s fate was the one that made me wonder why the Vikings got the reputation for being bloody barbarians. They were no bloodier or brutal than their peers in Rome or throughout the Holy Roman Empire in those days.

Philagathos had joined the imperial court before Otto’s birth. Some sources say he was Otto’s godfather, others that he tutored the boy in Greek. In 994, Otto sent him to Constantinople to find him a royal Byzantine bride, and so he was not at hand in 996 when John XV died and Otto appointed his cousin as pope.

Returning less than a year later, Philagathos felt unjustly overlooked. His traveling companion, Leo of Synada, whom the Byzantine emperor had sent to continue the marriage negotiations, agreed. Meeting in Rome with Crescentius of the Marble Horse, the two ambassadors urged him to appoint a new pope. So he did. Gregory was chased out of town in September 996. Philagathos was acclaimed John XVI by the citizens and senate of Rome and anointed in February 997. He would last until Otto III arrived.

The emperor's army, led by Gregory V’s father, cowed Rome into surrender after one skirmish. Philagathos fled. Crescentius walled himself up in the Castel Sant’Angelo and held out for two months, until Otto’s siege engines broke through. Crescentius was beheaded and hanged by the feet from the castle walls alongside twelve of his companions.

Philagathos was captured by Berthold, count of Breisgau. “Fearing that if they sent him to the emperor, he might depart unpunished,” say the Annals of Quedlinburg, Gregory V’s German partisans took matters into their own hands.

Leo of Synada gleefully tells the story: “Now you are going to laugh, a big, broad laugh, my dear heart and soul,” he begins. Philagathos, whom Leo clearly never liked, has fallen:

And why shouldn’t I tell you, brother, openly how he fell? Well, first, the Church of the West dealt him anathema; then his eyes were gouged out; third, his nose, and fourth, his lip, and fifth, that tongue of his which prattled so many and such unspeakable words, one by one, were all cut from his face. Item six: He rode like a conqueror in procession, grave and solemn on a miserable little donkey, hanging on to its tail.… Finally, for his refreshment, they threw him into prison.

And why shouldn’t I tell you, brother, openly how he fell? Well, first, the Church of the West dealt him anathema; then his eyes were gouged out; third, his nose, and fourth, his lip, and fifth, that tongue of his which prattled so many and such unspeakable words, one by one, were all cut from his face. Item six: He rode like a conqueror in procession, grave and solemn on a miserable little donkey, hanging on to its tail.… Finally, for his refreshment, they threw him into prison.I think of this every time someone says the Vikings were brutal.

Pope Gregory V was reinstated, but died of malaria in 999, at the age of 28. Then Emperor Otto III nominated as pope his own tutor, the leading mathematician and astronomer of his age, Gerbert of Aurillac, subject of my book The Abacus and the Cross.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And don't forget to enter the raffle for a free, autographed copy of Song of the Vikings. Details are in last week's post or click here .

Published on March 13, 2013 08:15