Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 2

December 15, 2021

The Witch's Heart

In her novel,

The Witch's Heart

, Genevieve Gornichec picks apart the ancient tapestry of Old Norse myths, sorts and irons out the colored threads, adds some narrative silver wire and sparkling jewels, and embroiders a stunning new story of the Norse gods and giants.

Much of what we know about Norse mythology comes from one short book written in Iceland in the early 1200s by a man named Snorri Sturluson. It's called the Prose Edda, or Snorri's Edda. By the time Snorri wrote it, Iceland and the rest of Scandinavia had been Christian for 200 years. No one exclusively worshipped the old gods. Snorri himself was educated in a powerful Christian family. When Snorri was 17, his foster brother, Páll, was elected the Bishop of Skalholt.

Much of what we know about Norse mythology comes from one short book written in Iceland in the early 1200s by a man named Snorri Sturluson. It's called the Prose Edda, or Snorri's Edda. By the time Snorri wrote it, Iceland and the rest of Scandinavia had been Christian for 200 years. No one exclusively worshipped the old gods. Snorri himself was educated in a powerful Christian family. When Snorri was 17, his foster brother, Páll, was elected the Bishop of Skalholt.

As I explain in my 2013 biography of him, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths , Snorri had no intention of "collecting" or "preserving" pagan myths for us to enjoy 800 years later--though that's what he did. Snorri was not thinking about his "legacy." Like every writer, he had an immediate audience and purpose in mind when he sat down to write. His audience was the 16-year-old Norwegian king. His purpose was to teach the young king to appreciate the poetry of the ancient North--so that he himself could obtain a powerful position at court.

Snorri was an expert in the songs of the Vikings. He had memorized nearly a thousand poems and could write in the ancient skaldic style himself, with its convoluted word order, its strict rules about rhyme and meter and alliteration, and its many vague allusions to mythology. When he went to Norway in 1218, Snorri brought a new poem to recite. He expected to be named King's Skald, or court poet.

But young King Hakon thought skaldic poetry was old-fashioned. It was too hard to understand. He preferred the tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, which were just then being translated from the French.

Snorri must have been shocked. Skalds, or court poets, had been a fixture at the Norwegian court for 400 years. Skalds were a king's ambassadors, counselors, and keepers of history. They were part of the high ritual of his royal court, upholding the Viking virtues of generosity and valor. They legitimized his claim to kingship. They were time-binders: They wove the past into the present.

Snorri wrote the Edda to teach the young king his heritage.

To appease the bishops, who controlled the young king, Snorri put a Christian slant on the myths he told. He wasted few words on female characters, choosing instead stories that would excite a young man: stories of fast horses, magic swords, and trials of strength.

When goddesses and giantesses do appear in Snorri's Edda, they are reduced to objects of lust--or disgust.

Such as the one at the center of Genevieve Gornichec's The Witch's Heart .

"There was a giantess called Angrboda in Giantland," Snorri writes (in the 1987 translation by Anthony Faulkes). "With her Loki had three children. One was Fenriswolf, the second Iormungard (i.e. the Midgard serpent), the third is Hel. And when the gods realized that these three siblings were being brought up in Giantland, and when the gods traced prophecies stating that from these siblings great mischief and disaster would arise for them, then they all felt evil was to be expected from them, to begin with because of their mother's nature, but still worse because of their father's." The gods capture the three children and take them away--but Angrboda, their mother, lover of the Trickster God Loki, is never mentioned again.

In The Witch's Heart , Genevieve Gornichec fills that void, imagining the Tale of Angrboda that Snorri never told. It's a love story, an origin story, a coming-of-age tale, and a quest, with an indomitable witch at its center. The mother of Loki's monster children will win a place in your heart.

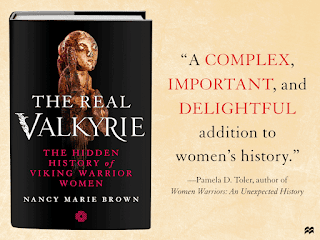

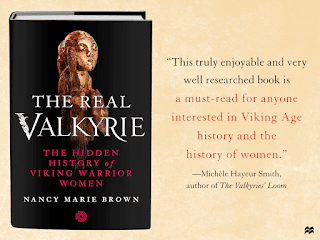

For more stories of powerful Viking women, see my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , or read the related posts on this blog (click here).

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Much of what we know about Norse mythology comes from one short book written in Iceland in the early 1200s by a man named Snorri Sturluson. It's called the Prose Edda, or Snorri's Edda. By the time Snorri wrote it, Iceland and the rest of Scandinavia had been Christian for 200 years. No one exclusively worshipped the old gods. Snorri himself was educated in a powerful Christian family. When Snorri was 17, his foster brother, Páll, was elected the Bishop of Skalholt.

Much of what we know about Norse mythology comes from one short book written in Iceland in the early 1200s by a man named Snorri Sturluson. It's called the Prose Edda, or Snorri's Edda. By the time Snorri wrote it, Iceland and the rest of Scandinavia had been Christian for 200 years. No one exclusively worshipped the old gods. Snorri himself was educated in a powerful Christian family. When Snorri was 17, his foster brother, Páll, was elected the Bishop of Skalholt. As I explain in my 2013 biography of him, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths , Snorri had no intention of "collecting" or "preserving" pagan myths for us to enjoy 800 years later--though that's what he did. Snorri was not thinking about his "legacy." Like every writer, he had an immediate audience and purpose in mind when he sat down to write. His audience was the 16-year-old Norwegian king. His purpose was to teach the young king to appreciate the poetry of the ancient North--so that he himself could obtain a powerful position at court.

Snorri was an expert in the songs of the Vikings. He had memorized nearly a thousand poems and could write in the ancient skaldic style himself, with its convoluted word order, its strict rules about rhyme and meter and alliteration, and its many vague allusions to mythology. When he went to Norway in 1218, Snorri brought a new poem to recite. He expected to be named King's Skald, or court poet.

But young King Hakon thought skaldic poetry was old-fashioned. It was too hard to understand. He preferred the tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, which were just then being translated from the French.

Snorri must have been shocked. Skalds, or court poets, had been a fixture at the Norwegian court for 400 years. Skalds were a king's ambassadors, counselors, and keepers of history. They were part of the high ritual of his royal court, upholding the Viking virtues of generosity and valor. They legitimized his claim to kingship. They were time-binders: They wove the past into the present.

Snorri wrote the Edda to teach the young king his heritage.

To appease the bishops, who controlled the young king, Snorri put a Christian slant on the myths he told. He wasted few words on female characters, choosing instead stories that would excite a young man: stories of fast horses, magic swords, and trials of strength.

When goddesses and giantesses do appear in Snorri's Edda, they are reduced to objects of lust--or disgust.

Such as the one at the center of Genevieve Gornichec's The Witch's Heart .

"There was a giantess called Angrboda in Giantland," Snorri writes (in the 1987 translation by Anthony Faulkes). "With her Loki had three children. One was Fenriswolf, the second Iormungard (i.e. the Midgard serpent), the third is Hel. And when the gods realized that these three siblings were being brought up in Giantland, and when the gods traced prophecies stating that from these siblings great mischief and disaster would arise for them, then they all felt evil was to be expected from them, to begin with because of their mother's nature, but still worse because of their father's." The gods capture the three children and take them away--but Angrboda, their mother, lover of the Trickster God Loki, is never mentioned again.

In The Witch's Heart , Genevieve Gornichec fills that void, imagining the Tale of Angrboda that Snorri never told. It's a love story, an origin story, a coming-of-age tale, and a quest, with an indomitable witch at its center. The mother of Loki's monster children will win a place in your heart.

For more stories of powerful Viking women, see my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , or read the related posts on this blog (click here).

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on December 15, 2021 08:00

December 8, 2021

Odin's Wife

In his Edda, the 13th-century Icelander Snorri Sturluson presents Norse mythology through a wisdom match between the clever King Gylfi and three gods--High, Just-as-High, and Third--who sit on thrones in Valhalla.

Asked "Who is the highest and most ancient of all gods?" High responds with a list of twelve names, beginning with All-father. Later he applies the name All-father to Odin--along with 52 more names.

"What a terrible lot of names you have given him!" objects King Gylfi in Anthony Faulkes’ 1987 translation. "One would need a great deal of learning to be able to give details and explanations of what events have given rise to each of these names."

Responds High, "You cannot claim to be a wise man if you are unable to tell of these important happenings."

Snorri Sturluson considered himself a wise man. In his Edda and in Heimskringla, his collection of sagas about Norway's kings, Snorri quotes apt lines from nearly a thousand poems, most of which had not been written down before.

But because he wrote for an audience of one--young King Hakon of Norway, brought to the throne at age 14--Snorri's tales in these two books skew toward the interests of a boy. As I pointed out in my 2013 biography of him, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths , Snorri wasted few words on women, human or divine. It's no surprise that he fails to tell us the many names of Odin's wife, or to relate the events that gave rise to them.

In

Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology

, William P. Reaves attempts to fill in the gaps in Snorri's Edda--proving himself a wise man by High's definition. Reaves is webmaster of the site germanicmythology.com, which aims to compile everything of interest to students of Norse mythology that exists in the public domain. It shouldn't surprise you that Odin's Wife is similarly comprehensive.

In

Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology

, William P. Reaves attempts to fill in the gaps in Snorri's Edda--proving himself a wise man by High's definition. Reaves is webmaster of the site germanicmythology.com, which aims to compile everything of interest to students of Norse mythology that exists in the public domain. It shouldn't surprise you that Odin's Wife is similarly comprehensive.

Snorri tells us that Frigg is Odin's wife and the mother of his son Baldur, while the Earth, or Jörd, is the mother of Odin's son Thor. According to the Edda, these are two separate goddesses. But as Reaves points out, "while evidence for Odin's wife Frigg and his wife the Earth are contemporary and congruous--occurring at the same time in the same places and genres--they are never shown together. Like Diana Prince and Wonder Woman, we apparently never see Frigg and Jörd side by side." Both goddesses are also called by several other names; one they hold in common is Hlin, which means "protector."

As Reaves lays out his "preponderance of evidence," the goddess Frigg leaps out of the shadows in which Snorri wrapped her. She convincingly becomes the powerful Earth-Mother and Mother of Gods, including not only Baldur and Thor, but also Freyr and Freyja, whom she had with her brother, Njörd. As Reaves concludes, "She is Odin’s equal in all respects, surpassing him in practical power."

That Frigg sits beside Odin on his throne, watching (and meddling in) all the Nine Worlds, "should not come as a surprise," he adds: "The sons of Borr bestowed senses, wit, and spirit on Ask and Embla alike. Women are not subordinate to men. The sources, both religious and historical, are rife with strong, independent women. Both men and women appear on the battlefield, as mythological, historical, and archaeological evidence affirms. Equality of the sexes was a Germanic reality, long before modern times."

See my complete review of Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology by William P. Reaves at The Midgardian.

For more about the powerful women of the Viking Age, see my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , or read the related posts on this blog (click here).

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Asked "Who is the highest and most ancient of all gods?" High responds with a list of twelve names, beginning with All-father. Later he applies the name All-father to Odin--along with 52 more names.

"What a terrible lot of names you have given him!" objects King Gylfi in Anthony Faulkes’ 1987 translation. "One would need a great deal of learning to be able to give details and explanations of what events have given rise to each of these names."

Responds High, "You cannot claim to be a wise man if you are unable to tell of these important happenings."

Snorri Sturluson considered himself a wise man. In his Edda and in Heimskringla, his collection of sagas about Norway's kings, Snorri quotes apt lines from nearly a thousand poems, most of which had not been written down before.

But because he wrote for an audience of one--young King Hakon of Norway, brought to the throne at age 14--Snorri's tales in these two books skew toward the interests of a boy. As I pointed out in my 2013 biography of him, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths , Snorri wasted few words on women, human or divine. It's no surprise that he fails to tell us the many names of Odin's wife, or to relate the events that gave rise to them.

In

Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology

, William P. Reaves attempts to fill in the gaps in Snorri's Edda--proving himself a wise man by High's definition. Reaves is webmaster of the site germanicmythology.com, which aims to compile everything of interest to students of Norse mythology that exists in the public domain. It shouldn't surprise you that Odin's Wife is similarly comprehensive.

In

Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology

, William P. Reaves attempts to fill in the gaps in Snorri's Edda--proving himself a wise man by High's definition. Reaves is webmaster of the site germanicmythology.com, which aims to compile everything of interest to students of Norse mythology that exists in the public domain. It shouldn't surprise you that Odin's Wife is similarly comprehensive. Snorri tells us that Frigg is Odin's wife and the mother of his son Baldur, while the Earth, or Jörd, is the mother of Odin's son Thor. According to the Edda, these are two separate goddesses. But as Reaves points out, "while evidence for Odin's wife Frigg and his wife the Earth are contemporary and congruous--occurring at the same time in the same places and genres--they are never shown together. Like Diana Prince and Wonder Woman, we apparently never see Frigg and Jörd side by side." Both goddesses are also called by several other names; one they hold in common is Hlin, which means "protector."

As Reaves lays out his "preponderance of evidence," the goddess Frigg leaps out of the shadows in which Snorri wrapped her. She convincingly becomes the powerful Earth-Mother and Mother of Gods, including not only Baldur and Thor, but also Freyr and Freyja, whom she had with her brother, Njörd. As Reaves concludes, "She is Odin’s equal in all respects, surpassing him in practical power."

That Frigg sits beside Odin on his throne, watching (and meddling in) all the Nine Worlds, "should not come as a surprise," he adds: "The sons of Borr bestowed senses, wit, and spirit on Ask and Embla alike. Women are not subordinate to men. The sources, both religious and historical, are rife with strong, independent women. Both men and women appear on the battlefield, as mythological, historical, and archaeological evidence affirms. Equality of the sexes was a Germanic reality, long before modern times."

See my complete review of Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology by William P. Reaves at The Midgardian.

For more about the powerful women of the Viking Age, see my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , or read the related posts on this blog (click here).

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on December 08, 2021 08:00

December 1, 2021

The Viking Creation Story

The Viking Age, I was taught, was an era of strict gender roles. The woman ruled the household. The man was the trader, the traveler, the warrior.

This interpretation—as I've noted previously on this blog—has been taught since the 1800s, the Victorian Age, when elite women were told to concern themselves only with church, children, and kitchen.

But it’s not the only way to read the sources.

In my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , I argue that roles in Viking society were decided—not by these Victorian ideas of men’s work vs. women’s work—but based on factors much harder to see.

I was convinced this was true by studying Norse mythology.

Our best sources on Norse mythology were written by the Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson. But Snorri is not trustworthy. In 2012, I wrote a biography of him ( Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths ) and showed that, not only did he put a Christian slant on the myths he told, he was a terrible misogynist.

In writing down the Norse myths, Snorri wasted few words on females, human or divine. They did not fit his audience or his purpose.

He began writing the Prose Edda in about 1220 for the 16-year-old Norwegian king to teach the young king to appreciate the poetry of the ancient North, with its many allusions to mythology; Snorri’s real goal was to gain an influential position at court.

Snorri wrote Heimskringla, his history of the kings of Norway, during the same king’s reign, again to impress the younger man.

Women in both books are honored mothers or objects of lust, Mary or Eve, as they were in Snorri’s own lifetime. It was the orthodox view of women in medieval Christian society, where even marriage and childbirth were considered matters for churchmen to control.

But Snorri gives us glimpses of the myths he left out—ancient stories that reflect the values of the pre-Christian Vikings. One of these is the Norse creation myth.

Here's how it goes: In the beginning two driftwood logs, one elm and one ash, are found on the seashore by three wandering gods. These gods give the wood human shape and bring it to life with blood, breath, and curious minds.

Here's how it goes: In the beginning two driftwood logs, one elm and one ash, are found on the seashore by three wandering gods. These gods give the wood human shape and bring it to life with blood, breath, and curious minds.

Unlike the Christian creation myth, where Eve is an afterthought, fashioned out of Adam’s rib, in the Norse myth Embla (the female) and Ask (the male) are equal:

They are made at the same time out of nearly the same stuff. As different as an ash tree and an elm, they make a good team.

Ash wood was used for spear shafts and oars. A good rower was sometimes called an “ash-person.”

Elm was used for wagon wheels. It was also the preferred wood for short, powerful bows: One archer is nicknamed “elm-twig.”

Both woods had roles in peace and war, for transportation and for killing. Their uses were determined by their size and strength, their resistance to rot or tensile stress, the denseness of their grain, and where they grew.

I think the same was likely true for the men and women of the Viking Age. They were equals, their roles in society being decided—not by gender—but based on ambition, ability, family ties, and wealth.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

This interpretation—as I've noted previously on this blog—has been taught since the 1800s, the Victorian Age, when elite women were told to concern themselves only with church, children, and kitchen.

But it’s not the only way to read the sources.

In my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , I argue that roles in Viking society were decided—not by these Victorian ideas of men’s work vs. women’s work—but based on factors much harder to see.

I was convinced this was true by studying Norse mythology.

Our best sources on Norse mythology were written by the Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson. But Snorri is not trustworthy. In 2012, I wrote a biography of him ( Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths ) and showed that, not only did he put a Christian slant on the myths he told, he was a terrible misogynist.

In writing down the Norse myths, Snorri wasted few words on females, human or divine. They did not fit his audience or his purpose.

He began writing the Prose Edda in about 1220 for the 16-year-old Norwegian king to teach the young king to appreciate the poetry of the ancient North, with its many allusions to mythology; Snorri’s real goal was to gain an influential position at court.

Snorri wrote Heimskringla, his history of the kings of Norway, during the same king’s reign, again to impress the younger man.

Women in both books are honored mothers or objects of lust, Mary or Eve, as they were in Snorri’s own lifetime. It was the orthodox view of women in medieval Christian society, where even marriage and childbirth were considered matters for churchmen to control.

But Snorri gives us glimpses of the myths he left out—ancient stories that reflect the values of the pre-Christian Vikings. One of these is the Norse creation myth.

Here's how it goes: In the beginning two driftwood logs, one elm and one ash, are found on the seashore by three wandering gods. These gods give the wood human shape and bring it to life with blood, breath, and curious minds.

Here's how it goes: In the beginning two driftwood logs, one elm and one ash, are found on the seashore by three wandering gods. These gods give the wood human shape and bring it to life with blood, breath, and curious minds. Unlike the Christian creation myth, where Eve is an afterthought, fashioned out of Adam’s rib, in the Norse myth Embla (the female) and Ask (the male) are equal:

They are made at the same time out of nearly the same stuff. As different as an ash tree and an elm, they make a good team.

Ash wood was used for spear shafts and oars. A good rower was sometimes called an “ash-person.”

Elm was used for wagon wheels. It was also the preferred wood for short, powerful bows: One archer is nicknamed “elm-twig.”

Both woods had roles in peace and war, for transportation and for killing. Their uses were determined by their size and strength, their resistance to rot or tensile stress, the denseness of their grain, and where they grew.

I think the same was likely true for the men and women of the Viking Age. They were equals, their roles in society being decided—not by gender—but based on ambition, ability, family ties, and wealth.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on December 01, 2021 08:00

November 24, 2021

Words of Wisdom

A year or two ago, a friend compiled a book of advice for his son's 18th birthday and asked me to contribute. Here is what I wrote:

When I was young, I was given three pieces of economic advice that gave me the freedom to live the life I wanted, as a writer.

1. Never pay interest.

1. Never pay interest.

That means paying off the credit card every month. That means buying a car with cash. That means no mortgage and no student loans. Is it possible? Not always, but it's worth striving for. If you can't afford it, you probably don't need it. There is no such thing as "shopping therapy." Buying things only makes you a slave to things.

In the Old Norse literature I study, there's a set of maxims called Havamál, or "Words of the High One," supposedly spoken by Odin himself more than a thousand years ago. It says (in the translation by Paul Taylor and W.H. Auden):

A kind word need not cost much,

The price of praise can be cheap:

With half a loaf and an empty cup

I found myself a friend.

2. Never have monthly bills that must be paid.

2. Never have monthly bills that must be paid.

Again, pay cash or don't buy it. But some things are unavoidable: the phone bill, the electric bill, the internet, and you have to live somewhere, so there will be either rent or a mortgage payment. My husband and I were lucky enough to be able to build a house out in the countryside (where the rules are more lax) and pay for it as we went. It was small and, at first, quite rustic (no electricity!). But as Havamál says,

A small hut of one's own is better,

A man is master at home:

A couple of goats and a corded roof

Still are better than begging.

We passed on the goats and got Icelandic horses—which is quite an unnecessary expense, but at least not one we need to pay monthly, and they make us happy.

3. Keep enough cash in the bank to cover one year’s necessary expenses.

3. Keep enough cash in the bank to cover one year’s necessary expenses.

That includes food, taxes, utilities, a mortgage if you have one (we didn't), insurance of various kinds and, for us, hay and shoeing and vet bills for the horses. It also means making up a yearly budget and sticking to it.

If you follow these three precepts, and have a little luck, you are free. If you have a job, you know they need you more than you need them. You can quit at any time and take a whole year to find a new job without ending up on the street.

If you don’t have a job and don’t want one (both my husband and I have been freelance writers now for over 15 years), you know how much money you need to make each year to replenish the bank account.

Once you've done that, you can relax—travel, ride the horses, write something that won't sell. It's up to you.

Too many people get caught up in the money economy. They buy things they can't afford and then are stuck working in a job they hate in order to pay for them—and they usually end up paying twice as much, in the end, counting the interest and loan fees.

Money is not nearly as valuable as your time and your freedom. Says Havamál,

Once he has won wealth enough,

A man should not crave for more…

And:

The generous and bold have the best lives.

For more on my latest book,

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my latest book,

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Illustrations by Gerhard Munthe from an 1899 edition of Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla.

When I was young, I was given three pieces of economic advice that gave me the freedom to live the life I wanted, as a writer.

1. Never pay interest.

1. Never pay interest. That means paying off the credit card every month. That means buying a car with cash. That means no mortgage and no student loans. Is it possible? Not always, but it's worth striving for. If you can't afford it, you probably don't need it. There is no such thing as "shopping therapy." Buying things only makes you a slave to things.

In the Old Norse literature I study, there's a set of maxims called Havamál, or "Words of the High One," supposedly spoken by Odin himself more than a thousand years ago. It says (in the translation by Paul Taylor and W.H. Auden):

A kind word need not cost much,

The price of praise can be cheap:

With half a loaf and an empty cup

I found myself a friend.

2. Never have monthly bills that must be paid.

2. Never have monthly bills that must be paid. Again, pay cash or don't buy it. But some things are unavoidable: the phone bill, the electric bill, the internet, and you have to live somewhere, so there will be either rent or a mortgage payment. My husband and I were lucky enough to be able to build a house out in the countryside (where the rules are more lax) and pay for it as we went. It was small and, at first, quite rustic (no electricity!). But as Havamál says,

A small hut of one's own is better,

A man is master at home:

A couple of goats and a corded roof

Still are better than begging.

We passed on the goats and got Icelandic horses—which is quite an unnecessary expense, but at least not one we need to pay monthly, and they make us happy.

3. Keep enough cash in the bank to cover one year’s necessary expenses.

3. Keep enough cash in the bank to cover one year’s necessary expenses. That includes food, taxes, utilities, a mortgage if you have one (we didn't), insurance of various kinds and, for us, hay and shoeing and vet bills for the horses. It also means making up a yearly budget and sticking to it.

If you follow these three precepts, and have a little luck, you are free. If you have a job, you know they need you more than you need them. You can quit at any time and take a whole year to find a new job without ending up on the street.

If you don’t have a job and don’t want one (both my husband and I have been freelance writers now for over 15 years), you know how much money you need to make each year to replenish the bank account.

Once you've done that, you can relax—travel, ride the horses, write something that won't sell. It's up to you.

Too many people get caught up in the money economy. They buy things they can't afford and then are stuck working in a job they hate in order to pay for them—and they usually end up paying twice as much, in the end, counting the interest and loan fees.

Money is not nearly as valuable as your time and your freedom. Says Havamál,

Once he has won wealth enough,

A man should not crave for more…

And:

The generous and bold have the best lives.

For more on my latest book,

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my latest book,

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Illustrations by Gerhard Munthe from an 1899 edition of Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla.

Published on November 24, 2021 08:00

November 17, 2021

The Dangerous Women of Oseberg

"What makes a woman dangerous 1000 years after her death?"

Archaeologist Marianne Moen asked that question in 2016 on a blog called "The Dangerous Women Project."

She wrote, "How much of a threat can a dead and decayed body of a nameless woman really pose? Judging from the academic treatment of the Viking Age female double burial found at Oseberg in Norway, the answer seems to be quite a substantial one. Enough, at least, that in the 100 years since the burial was excavated, academic debate regarding it has centred on finding explanations and interpretations that nearly all share a common purpose of removing the two women from any position of politcal power..."

Marianne's forthright and honest approach in this essay impressed me. I found and read her 2010 master's thesis from the University of Oslo,

The Gendered Landscape: A discussion on gender, status, and power expressed in the Viking Age mortuary landscape

, and was even more impressed. There, Marianne outlines the history of how archaeologists have gendered graves--based on very outdated ideas of what men and women are like. She then presents a new interpretation of Oseberg, comparing it to the other famous ship burial from Vestfold in southern Norway, at Gokstad.

Marianne's forthright and honest approach in this essay impressed me. I found and read her 2010 master's thesis from the University of Oslo,

The Gendered Landscape: A discussion on gender, status, and power expressed in the Viking Age mortuary landscape

, and was even more impressed. There, Marianne outlines the history of how archaeologists have gendered graves--based on very outdated ideas of what men and women are like. She then presents a new interpretation of Oseberg, comparing it to the other famous ship burial from Vestfold in southern Norway, at Gokstad.

When I went to Norway in 2018 to complete the research for my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , meeting Marianne was tops on my list. We managed to connect over lunch soon after I had visited the Oseberg and Gokstad mounds. What follows are some highlights of our chat which, of course, began with a discussion of the Oseberg grave.

"Every time I give a presentation," Marianne said, "I end up talking about Oseberg. It's fascinating if you look at how it's been treated academically--and then you look at Gokstad. Basically, they are identical mounds. They're placed in comparable locations. They've got very comparable grave goods. They're buried within 70 years of each other. Everything pretty much checks out: It's like tick, tick, tick, tick, tick. The only difference is that Oseberg is the burial of two women and Gokstad has one man.

Captions: The Oseberg mound today. Above, the Oseberg ship in the (old) Viking Ship Museum in Norway. Below, the Gokstad mound today.

Captions: The Oseberg mound today. Above, the Oseberg ship in the (old) Viking Ship Museum in Norway. Below, the Gokstad mound today.

"Then you read about them in academic treatments," she continued. "Here, you've got the Gokstad chieftain--it's always the Gokstad chieftain, you know--and there, you have the Oseberg women. Oh, who were they? We just don't know. They're ladies. How come? That's very strange! Were they religious spies? Or was there originally a man there in the grave and he's disappeared?"

"Then you read about them in academic treatments," she continued. "Here, you've got the Gokstad chieftain--it's always the Gokstad chieftain, you know--and there, you have the Oseberg women. Oh, who were they? We just don't know. They're ladies. How come? That's very strange! Were they religious spies? Or was there originally a man there in the grave and he's disappeared?"

Her comic portrayal of the baffled academics made me laugh--but it wasn't truly funny. Working on my history of warrior women in the Viking Age, I saw too many instances of such gender bias in Viking Studies. The "invisible man" theory came up again and again.

As Marianne explained, "A lot of researchers have problems with something that doesn't fit with what we think we know. We think we know the Viking Age so well. In Norway it's a sort of cultural ancestor to our own times. We talk about the Vikings as if we know how they lived--and we don't really.

"There is so much that we've just assumed. Two hundred years ago, a bunch of researchers read the old texts and said, 'Aha, it’s like this.' You look at the gender roles they assigned to the Viking Age--and they are the gender roles of the Victorian Age." They mimic the values of the 19th century, when elite women were confined to church, children, and kitchen. When wife, mother, and housewife were women's only proper roles.

"We don't know it was like that in the Viking Age," Marianne continued. "But somebody said so 200 years ago, and we've referred to them for years and years."

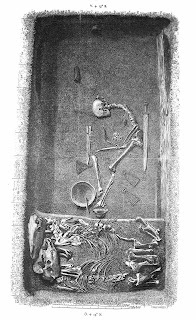

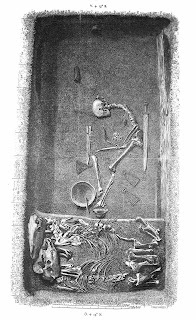

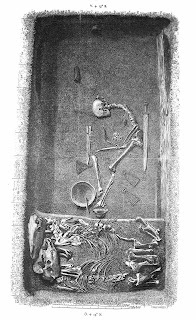

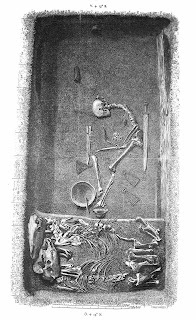

Between the time Marianne wrote about the two Oseberg queens as "dangerous women" in 2016 and we met in 2018, the ultimate Viking warrior burial--the weapon-filled grave known as Bj581 in the town of Birka--was reanalyzed. Ancient DNA was successfully extracted from the bones and--to the shock of many scholars--this ultimate Viking was proved to be a woman.

The backlash was fierce. Even scholars who had, in the past, collaborated with the DNA-testing team, accused them of having tested the wrong bones, or of polluting the DNA, or of having made some other crucial mistake. These critics were not ready to accept that their picture of gender roles in the Viking Age was wrong. They were not ready to accept that something they thought was a fact was, in reality, only an assumption.

The backlash was fierce. Even scholars who had, in the past, collaborated with the DNA-testing team, accused them of having tested the wrong bones, or of polluting the DNA, or of having made some other crucial mistake. These critics were not ready to accept that their picture of gender roles in the Viking Age was wrong. They were not ready to accept that something they thought was a fact was, in reality, only an assumption.

"What's been so interesting about the Birka Warrior," Marianne said to me, "is that it's really just made this very obvious. If you read between the lines of so many of the blogs and the statements that came out in response to the Birka Warrior, what the critics are saying is: This can't be right because it doesn't fit with what we think we know. Accepting that what we think we know is potentially not correct seems to be pretty difficult."

One approach by the naysayers is to argue that having weapons in her grave is not enough to prove that Bj581 actually fought. They point out that there are no marks of battle trauma on her bones, for instance.

I asked Marianne how she would respond to that criticism.

"There’s this big argument in archaeology today," she explained, "that, obviously, just because you're buried with weapons it doesn't make you a warrior. Fair enough. There's this famous study of Anglo-Saxon graves, where they demonstrated that a lot of the so-called warrior graves were actually young boys or the skeleton had severe physical impairments. So I’m not saying that every weapons grave is necessarily a warrior grave.

"What I am saying," she continued, "is that, just because the grave happens to contain a woman doesn’t mean we should treat it any differently. So if a weapons grave isn't a warrior grave, that means we need to go through 200 years of scholarship and reassess how we talk about all the male graves with weapons. That’s all I'm asking. You can't talk about weapons graves differently just because of the gender of the person buried in one. Because then what we think we know is not based on the actual evidence."

Even scholars who accept that Bj581 was indeed a warrior woman argue that she was very unusual for her time. Finding a single warrior woman doesn't change the conversation about women's roles in the Viking Age.

Again, Marianne disagrees.

"I'm not arguing for the number of female warriors being on the same level as men," Marianne replied, "because we know from the burial evidence that we do have that it's not that often you find women with weapons. But it's often enough."

But Viking men are not often found buried with weapons either, I pointed out. Not every man was a warrior.

"Exactly," said Marianne. "It was only really exceptional men."

When I first began talking about writing my book The Real Valkyrie , I heard that complaint from some of my scholarly friends: But you’re only talking about exceptional women, they said.

I thought about that, and I realized that if I had said I was going to write a book about a Viking king, like Olaf Tryggvason or Eirik Bloodaxe, he would be an exceptional man, and it would be perfectly acceptible to write a book about him. No one would complain about that. Why is it not equally acceptible to write about an exceptional warrior woman?

"This is the problem," said Marianne. "All of the archaeology and all of the history of the Vikings is written about the exceptions. That's the people we write about. We write about the 15-20% who were the elite. We don't know anything about the rest. They leave no trace in the archaeological record. We need to accept that. Yes, the Birka Warrior was probably an exceptional women, but all the stories we tell are about the exceptional people."

And even among these exceptional, elite Vikings, our 200-year-old assumptions about gender roles do not hold true, as Marianne's 2019 Ph.D. thesis from the University of Oslo proves. When we spoke, she was hard at work writing Challenging Gender: A reconsideration of gender in the Viking Age using the mortuary landscape .

I asked her to tell me a little about it.

"My central proposition is that we shouldn't apply our understanding of gender to the past. I'm basically going back to Carol Clover's 1993 article [“Regardless of Sex: Men, Women, and Power in Early Northern Europe.”]. I think we should stop thinking about the two-sex model, with binary men and women as complete opposites."

Instead, we should think of Viking people inhabiting a spectrum of gender roles, she argues, based on her reanalysis of several Viking Age graveyards in Norway.

"What I've done," she explained, "is to analyze grave assemblages and also the position of the grave in the landscape, in some selected cemeteries in Vestfold, to try and see if there's any grounds from the burial evidence to assume that men and women fulfilled such different categories.

"What I found in the assemblages of grave goods, is that they share more traits than they actually differentiate. Interestingly, about a third of the graves I analyzed aren't gender-specific at all. They have horses, cooking vessels, common tools, less common tools like trading equipment, things like knives and combs, etc. Nothing particularly spectacular, usually, but a few of them are very wealthy indeed.

"That's where I think it becomes particularly problematic that we talk about the Vikings as if they had this very clearcut binary gender pattern, when actually so many graves are not able to be gendered at all," Marianne concluded.

"So here's my question: If so many of these graves are not communicating gender, then should we not perhaps reconsider our thought that gender was an either/or in the Viking Age? And that there were different ways of living that were accepted?"

I look forward to learning more from Marianne Moen's research in the future, and wish her the best of luck in her scholarly career. You can read more about her work on her Academia.edu page and at Science Norway.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Archaeologist Marianne Moen asked that question in 2016 on a blog called "The Dangerous Women Project."

She wrote, "How much of a threat can a dead and decayed body of a nameless woman really pose? Judging from the academic treatment of the Viking Age female double burial found at Oseberg in Norway, the answer seems to be quite a substantial one. Enough, at least, that in the 100 years since the burial was excavated, academic debate regarding it has centred on finding explanations and interpretations that nearly all share a common purpose of removing the two women from any position of politcal power..."

Marianne's forthright and honest approach in this essay impressed me. I found and read her 2010 master's thesis from the University of Oslo,

The Gendered Landscape: A discussion on gender, status, and power expressed in the Viking Age mortuary landscape

, and was even more impressed. There, Marianne outlines the history of how archaeologists have gendered graves--based on very outdated ideas of what men and women are like. She then presents a new interpretation of Oseberg, comparing it to the other famous ship burial from Vestfold in southern Norway, at Gokstad.

Marianne's forthright and honest approach in this essay impressed me. I found and read her 2010 master's thesis from the University of Oslo,

The Gendered Landscape: A discussion on gender, status, and power expressed in the Viking Age mortuary landscape

, and was even more impressed. There, Marianne outlines the history of how archaeologists have gendered graves--based on very outdated ideas of what men and women are like. She then presents a new interpretation of Oseberg, comparing it to the other famous ship burial from Vestfold in southern Norway, at Gokstad. When I went to Norway in 2018 to complete the research for my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , meeting Marianne was tops on my list. We managed to connect over lunch soon after I had visited the Oseberg and Gokstad mounds. What follows are some highlights of our chat which, of course, began with a discussion of the Oseberg grave.

"Every time I give a presentation," Marianne said, "I end up talking about Oseberg. It's fascinating if you look at how it's been treated academically--and then you look at Gokstad. Basically, they are identical mounds. They're placed in comparable locations. They've got very comparable grave goods. They're buried within 70 years of each other. Everything pretty much checks out: It's like tick, tick, tick, tick, tick. The only difference is that Oseberg is the burial of two women and Gokstad has one man.

Captions: The Oseberg mound today. Above, the Oseberg ship in the (old) Viking Ship Museum in Norway. Below, the Gokstad mound today.

Captions: The Oseberg mound today. Above, the Oseberg ship in the (old) Viking Ship Museum in Norway. Below, the Gokstad mound today. "Then you read about them in academic treatments," she continued. "Here, you've got the Gokstad chieftain--it's always the Gokstad chieftain, you know--and there, you have the Oseberg women. Oh, who were they? We just don't know. They're ladies. How come? That's very strange! Were they religious spies? Or was there originally a man there in the grave and he's disappeared?"

"Then you read about them in academic treatments," she continued. "Here, you've got the Gokstad chieftain--it's always the Gokstad chieftain, you know--and there, you have the Oseberg women. Oh, who were they? We just don't know. They're ladies. How come? That's very strange! Were they religious spies? Or was there originally a man there in the grave and he's disappeared?" Her comic portrayal of the baffled academics made me laugh--but it wasn't truly funny. Working on my history of warrior women in the Viking Age, I saw too many instances of such gender bias in Viking Studies. The "invisible man" theory came up again and again.

As Marianne explained, "A lot of researchers have problems with something that doesn't fit with what we think we know. We think we know the Viking Age so well. In Norway it's a sort of cultural ancestor to our own times. We talk about the Vikings as if we know how they lived--and we don't really.

"There is so much that we've just assumed. Two hundred years ago, a bunch of researchers read the old texts and said, 'Aha, it’s like this.' You look at the gender roles they assigned to the Viking Age--and they are the gender roles of the Victorian Age." They mimic the values of the 19th century, when elite women were confined to church, children, and kitchen. When wife, mother, and housewife were women's only proper roles.

"We don't know it was like that in the Viking Age," Marianne continued. "But somebody said so 200 years ago, and we've referred to them for years and years."

Between the time Marianne wrote about the two Oseberg queens as "dangerous women" in 2016 and we met in 2018, the ultimate Viking warrior burial--the weapon-filled grave known as Bj581 in the town of Birka--was reanalyzed. Ancient DNA was successfully extracted from the bones and--to the shock of many scholars--this ultimate Viking was proved to be a woman.

The backlash was fierce. Even scholars who had, in the past, collaborated with the DNA-testing team, accused them of having tested the wrong bones, or of polluting the DNA, or of having made some other crucial mistake. These critics were not ready to accept that their picture of gender roles in the Viking Age was wrong. They were not ready to accept that something they thought was a fact was, in reality, only an assumption.

The backlash was fierce. Even scholars who had, in the past, collaborated with the DNA-testing team, accused them of having tested the wrong bones, or of polluting the DNA, or of having made some other crucial mistake. These critics were not ready to accept that their picture of gender roles in the Viking Age was wrong. They were not ready to accept that something they thought was a fact was, in reality, only an assumption. "What's been so interesting about the Birka Warrior," Marianne said to me, "is that it's really just made this very obvious. If you read between the lines of so many of the blogs and the statements that came out in response to the Birka Warrior, what the critics are saying is: This can't be right because it doesn't fit with what we think we know. Accepting that what we think we know is potentially not correct seems to be pretty difficult."

One approach by the naysayers is to argue that having weapons in her grave is not enough to prove that Bj581 actually fought. They point out that there are no marks of battle trauma on her bones, for instance.

I asked Marianne how she would respond to that criticism.

"There’s this big argument in archaeology today," she explained, "that, obviously, just because you're buried with weapons it doesn't make you a warrior. Fair enough. There's this famous study of Anglo-Saxon graves, where they demonstrated that a lot of the so-called warrior graves were actually young boys or the skeleton had severe physical impairments. So I’m not saying that every weapons grave is necessarily a warrior grave.

"What I am saying," she continued, "is that, just because the grave happens to contain a woman doesn’t mean we should treat it any differently. So if a weapons grave isn't a warrior grave, that means we need to go through 200 years of scholarship and reassess how we talk about all the male graves with weapons. That’s all I'm asking. You can't talk about weapons graves differently just because of the gender of the person buried in one. Because then what we think we know is not based on the actual evidence."

Even scholars who accept that Bj581 was indeed a warrior woman argue that she was very unusual for her time. Finding a single warrior woman doesn't change the conversation about women's roles in the Viking Age.

Again, Marianne disagrees.

"I'm not arguing for the number of female warriors being on the same level as men," Marianne replied, "because we know from the burial evidence that we do have that it's not that often you find women with weapons. But it's often enough."

But Viking men are not often found buried with weapons either, I pointed out. Not every man was a warrior.

"Exactly," said Marianne. "It was only really exceptional men."

When I first began talking about writing my book The Real Valkyrie , I heard that complaint from some of my scholarly friends: But you’re only talking about exceptional women, they said.

I thought about that, and I realized that if I had said I was going to write a book about a Viking king, like Olaf Tryggvason or Eirik Bloodaxe, he would be an exceptional man, and it would be perfectly acceptible to write a book about him. No one would complain about that. Why is it not equally acceptible to write about an exceptional warrior woman?

"This is the problem," said Marianne. "All of the archaeology and all of the history of the Vikings is written about the exceptions. That's the people we write about. We write about the 15-20% who were the elite. We don't know anything about the rest. They leave no trace in the archaeological record. We need to accept that. Yes, the Birka Warrior was probably an exceptional women, but all the stories we tell are about the exceptional people."

And even among these exceptional, elite Vikings, our 200-year-old assumptions about gender roles do not hold true, as Marianne's 2019 Ph.D. thesis from the University of Oslo proves. When we spoke, she was hard at work writing Challenging Gender: A reconsideration of gender in the Viking Age using the mortuary landscape .

I asked her to tell me a little about it.

"My central proposition is that we shouldn't apply our understanding of gender to the past. I'm basically going back to Carol Clover's 1993 article [“Regardless of Sex: Men, Women, and Power in Early Northern Europe.”]. I think we should stop thinking about the two-sex model, with binary men and women as complete opposites."

Instead, we should think of Viking people inhabiting a spectrum of gender roles, she argues, based on her reanalysis of several Viking Age graveyards in Norway.

"What I've done," she explained, "is to analyze grave assemblages and also the position of the grave in the landscape, in some selected cemeteries in Vestfold, to try and see if there's any grounds from the burial evidence to assume that men and women fulfilled such different categories.

"What I found in the assemblages of grave goods, is that they share more traits than they actually differentiate. Interestingly, about a third of the graves I analyzed aren't gender-specific at all. They have horses, cooking vessels, common tools, less common tools like trading equipment, things like knives and combs, etc. Nothing particularly spectacular, usually, but a few of them are very wealthy indeed.

"That's where I think it becomes particularly problematic that we talk about the Vikings as if they had this very clearcut binary gender pattern, when actually so many graves are not able to be gendered at all," Marianne concluded.

"So here's my question: If so many of these graves are not communicating gender, then should we not perhaps reconsider our thought that gender was an either/or in the Viking Age? And that there were different ways of living that were accepted?"

I look forward to learning more from Marianne Moen's research in the future, and wish her the best of luck in her scholarly career. You can read more about her work on her Academia.edu page and at Science Norway.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on November 17, 2021 08:00

November 10, 2021

The Myth of the Mighty Viking Ship

In the midst of World War II, with the Nazis extolling their Viking heritage, the Swedish writer Frans G. Bengtsson began writing "a story that people could enjoy reading, like The Three Musketeers or the Odyssey."

In the midst of World War II, with the Nazis extolling their Viking heritage, the Swedish writer Frans G. Bengtsson began writing "a story that people could enjoy reading, like The Three Musketeers or the Odyssey." Bengtsson had made his literary reputation with the biography of an 18th-century king. But for this story he tried a new genre, the historical novel, and a new period of time. His Vikings are common men, smart, witty, and open-minded. "When encountering a Jew who allies with the Vikings and leads them to treasure beyond their dreams, they are duly grateful," notes one critic. "Bengtsson in effect throws the Viking heritage back in the Nazis' face."

His effect on that Viking heritage, however, was not benign. His story, Rode Orm, is one of the most-read and most-loved books in Swedish, and has been translated into over twenty languages; in English it's The Long Ships . Part of the story takes place on the East Way, which the red-haired Orm travels in a lapstrake ship with 24 pairs of oars. Based on the Oseberg ship’s 15 pairs of oars or the Gokstad ship’s 16, such a mighty vessel would stretch nearly 100 feet long and weigh 16 to 18 tons, empty. To cross the many portages between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, Red Orm’s "cheerful crew" threw great logs in front of the prow and hauled the boat along these rollers "in exchange for swigs of 'dragging beer,'" Bengtsson wrote.

This, say experimental archaeologists, is "unproven," "improbable," and—after several tries with replica ships—"not possible."

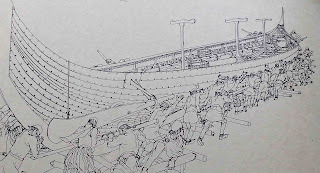

But Bengtsson's fiction burned itself into popular memory. Early scholars were convinced, too: A drawing of dozens of men attempting to roll a mighty ship on loose logs illustrates the eastern voyages in the classic compendium The Viking from 1966.

"Seldom has anything been surrounded by so much myth and fantasy" as the Viking ship, notes Gunilla Larsson; her 2007 Ph.D. thesis,

Ship and Society: Maritime Ideology in Late Iron Age Sweden

, completely changes our understanding of the Vikings' eastern voyages.

"Seldom has anything been surrounded by so much myth and fantasy" as the Viking ship, notes Gunilla Larsson; her 2007 Ph.D. thesis,

Ship and Society: Maritime Ideology in Late Iron Age Sweden

, completely changes our understanding of the Vikings' eastern voyages. Like the myth of the Viking housewife with her keys, which I wrote about last week, the myth of the mighty Viking ship is so common it's taken to be true. But the facts do not back it up.

In the 1990s, archaeologists attempted several times to take replica Viking ships between rivers or across isthmuses using the log-rolling method. They failed. They scaled down their ships. They still failed. Their ships were a half to a third the length of Red Orm's mighty ship. They weighed only one to two tons, not 16 tons. Yet they could not be cheerfully hauled by their crews, no matter how much beer was provided. The task was inefficient even when horses—or wheels or winches or wagons—were added.

We think bigger is better, but it's not.

The beautiful Oseberg ship with its spiral prow and the sleek Gokstad ship, praised as an "ideal form" and "a poem carved in wood," have been considered the classic Viking ships from the time they were first unearthed. Images of these Norwegian ships grace uncountable books on Viking Age history, uncountable museum exhibitions, uncountable souvenirs in Scandinavian gift shops.

But a third ship of equal importance for understanding the Viking Age was discovered in 1898, after Gokstad (1880) and before Oseberg (1903), by a Swedish farmer digging a ditch to dry out a boggy meadow. He axed through the wreck and laid his drain pipes. The landowner, a bit of an antiquarian, decided to rescue the boat and pulled the pieces of old wood out of the ground. His collection founded a local museum, but the boat pieces lay ignored in the attic—unmarked, unnumbered, with no drawings to say how they had lain in the earth when found—until 1980, when a radiocarbon survey of the museum's contents dated them to the 11th century. Their great age was confirmed by tree-ring data, which found the wood for the boat had been cut before 1070.

In the 1990s, archaeologist Gunilla Larsson took on the task of puzzling the pieces back into a boat. She had bits of much of the hull: of the keel, the stem and stern and five wide strakes, even some of the wooden rail attached to the gunwale. She had most of the frames, one bite, and two knees. About 2 feet in the middle of the boat was missing: where the ditch went through. The iron rivets had rusted away, but the rivet holes in the wood were easy to see and, since the distance between them varied, the parts could only go together one way. The wood itself had been flattened by time, but it was still sturdy enough to be soaked in hot water and bent into shape—the same technique the original boatbuilder had used.

When she had solved this 3D jigsaw puzzle, she engaged the National Maritime Museum in Stockholm to help her mount the pieces on an iron frame; the Viks Boat went on display in 1996.

Then she created a replica, Tälja, and tested it by sailing, rowing, and portaging around Lake Malaren. Tälja glided up shallow streams, its pliable planks bending and sliding over rocks. With only the power of its crew, it was easily portaged from one watershed to the next, from Lake Malaren to Lake Vanern in the west, itself draining into the Kattegat.

Then she created a replica, Tälja, and tested it by sailing, rowing, and portaging around Lake Malaren. Tälja glided up shallow streams, its pliable planks bending and sliding over rocks. With only the power of its crew, it was easily portaged from one watershed to the next, from Lake Malaren to Lake Vanern in the west, itself draining into the Kattegat. A second Viks Boat replica, Fornkåre, was built in 2012 and taken on the Vikings' East Way from Lake Malaren to Novgorod the first year, then south, by rivers and lakes, some 250 miles through Russia the second year. Concludes Fornkåre’s builder and captain, Lennart Widerberg, "The vessel proved itself capable of traveling this ancient route" from Birka to Byzantium.

The Viks Boat is 31 feet long—longer than two earlier replicas that failed the East Way portage test—and about 7 feet wide, comfortable for a crew of 8 to 10. Its replicas passed the portage test for two reasons. First, they were built, like the original, with strakes that were radially split, not sawn. The resulting board is easy to bend and hard to break—at less than half an inch thick. The resulting boat is equally seaworthy at almost half the weight of the same size boat built with the same lapstrake technique, but using sawn boards. Empty, the Viks Boat replicas weigh only half a ton—about as much as a horse.

The second reason the Viks Boat replicas proved adequate for the East Way was that archaeologists had set aside Frans Bengtsson’s fantastical log-rolling technique for crossing from stream to stream.

By studying the ways the Sami had portaged their dugout canoes through the waterways of Sweden and Finland throughout history, the archaeologists began to see signs of similar portage-ways around Lake Malaren. They built some themselves and had teams race replica ships through an obstacle course of portage types: smooth grassy paths, log-lined roads or ditches (with the logs aligned in the direction of travel), and bogs layered with branches. A team of two adults and seven 17-year-olds finished a winding, half-mile course with Talja in an hour. When the portage was straight over 4-inch-thick logs sunk into the mud so they didn’t shift, the boat raced at 150 feet a minute.

The beauty of the Gokstad ship, its poetic quality, comes from its curves, the hull swelling out from the gunwale then tightly back in, making a distinctive V-shape down to the deep, straight keel. These concave curves improve the ship’s sailing ability at sea. But the keel cuts too deep to float a shallow, stony stream like those that connect the Baltic to the Black Sea.

Over a portage, even the minimal keel of the Viks Boat replicas needed to be protected with an easily replaceable covering of birch, as had been found on the original. The Old Norse name for this false keel was drag. To "set a drag under someone's pride" was to encourage arrogance.

Historians and archaeologists of the Viking Age have long benefited from an ideological false keel. With the Viks Boat taking its rightful place as an exemplar of the Viking ship, it's time to knock off that damaged drag and replace it. Says Larsson, "We should get used to a completely different picture of the Scandinavian traveling eastward in the Viking Age, one that is far from the traditional image of the male Viking warrior in the prow of a big warship."

This essay was excerpted from my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women. To learn more, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Click on the title to download and read Gunilla Larsson's 2007 Ph.D. thesis, Ship and Society: Maritime Ideology in Late Iron Age Sweden. I highly recommend it.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on November 10, 2021 08:00

November 3, 2021

The Myth of the Viking Keys

The Viking Age, I was taught, was an era of strict gender roles. The woman ruled the household: Her domain was innanstokks, "inside the threshold." She held considerable power, for she controlled clothing and food. In lands where winter lasts ten months and the growing season only two, the housewife decided who froze or starved. The larger the household, the more complex her job. Managing the household of a chieftain who kept 80 retainers, as well as family and servants, was like running a small business.

But for all that, the man held the "dominant role in all walks of life," I was taught. His duties began at the threshold and expanded outwards. His was the world of public affairs, of "decisions affecting the community at large." He was the trader, the traveler, the warrior. His symbol was the sword.

The woman's role, in turn, was symbolized by the keys she carried at her belt.

Except she didn't.

There are 140 Icelandic sagas; only one, recounting a feud from 1242, refers to a housewife's keys. A Danish marriage law from 1241 says that a bride is given to her husband "for honor and as wife, sharing his bed, for lock and keys, and for right of inheritance of a third of the property." A bawdy poem, in an Icelandic manuscript dated after 1270, describes the hyper-masculine Thunder god, Thor, dressed up as a bride with a ring of keys at his belt.

There are 140 Icelandic sagas; only one, recounting a feud from 1242, refers to a housewife's keys. A Danish marriage law from 1241 says that a bride is given to her husband "for honor and as wife, sharing his bed, for lock and keys, and for right of inheritance of a third of the property." A bawdy poem, in an Icelandic manuscript dated after 1270, describes the hyper-masculine Thunder god, Thor, dressed up as a bride with a ring of keys at his belt.

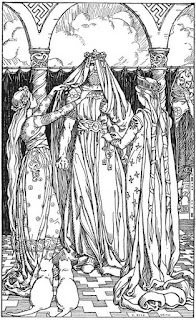

Caption: Illustration of Thor as a bride by Elmer Boyd Smith, from "In the Days of Giants: A Book of Norse Tales" (1902).

These texts might reflect a pagan Norse truth. They might equally reflect the values of medieval Christian world in which they were written. We can't tell.

What the keys do reflect are the values of 19th-century Victorian society, when upperclass women were confined to the home and told to concern themselves only with children, church, and kitchen. In Swedish history books in the 1860s, the myth of the Viking housewife replaced an earlier historical portrait of Viking women who were strikingly equal to Viking men. This Victorian version of Viking history has been presented since then as truth, but it is only one interpretation.

Surely archaeology backs up the well-known image of the Viking housewife with her keys, you insist.

It does not. Keys have been found in some women's graves. But they are not common, nowhere near as common as housewives. Against the 3,000 Viking Age swords that have been found in Norway, archaeologist Heidi Berg in 2015 sets only 143 keys, half of which were found in men's graves. In Denmark, Pernille Pantmann reported in 2011 that only nine out of 102 female graves she studied contained keys, and none of these "key graves" otherwise fit the model of "housewife."

Calling keys the symbol of a Viking woman's status, these and other researchers now say, is "an archaeological misinterpretation," "a mistake," "a myth"—and a dangerous one. Caption: For a new look at the meaning of keys, see "Women in the Viking Age" on the website of the Danish National Museum, where this image comes from.

Caption: For a new look at the meaning of keys, see "Women in the Viking Age" on the website of the Danish National Museum, where this image comes from.

By accepting the 19th-century stereotype of men with swords and women with keys, we legitimize the idea that women should stay at home.

We reduce the role models for every modern girl who visits a museum or reads a history book.

We make it easy to dismiss as unrealistic the warrior women found in every kind of medieval text that depicts Viking society—history, law, saga, poetry, and myth—and which have been attested to archaeologically since 2017, when the famous warrior grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden was DNA tested.

How would I re-interpret the role of women in Viking society? I try to answer that question in my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women . To learn more, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

But for all that, the man held the "dominant role in all walks of life," I was taught. His duties began at the threshold and expanded outwards. His was the world of public affairs, of "decisions affecting the community at large." He was the trader, the traveler, the warrior. His symbol was the sword.

The woman's role, in turn, was symbolized by the keys she carried at her belt.

Except she didn't.

There are 140 Icelandic sagas; only one, recounting a feud from 1242, refers to a housewife's keys. A Danish marriage law from 1241 says that a bride is given to her husband "for honor and as wife, sharing his bed, for lock and keys, and for right of inheritance of a third of the property." A bawdy poem, in an Icelandic manuscript dated after 1270, describes the hyper-masculine Thunder god, Thor, dressed up as a bride with a ring of keys at his belt.

There are 140 Icelandic sagas; only one, recounting a feud from 1242, refers to a housewife's keys. A Danish marriage law from 1241 says that a bride is given to her husband "for honor and as wife, sharing his bed, for lock and keys, and for right of inheritance of a third of the property." A bawdy poem, in an Icelandic manuscript dated after 1270, describes the hyper-masculine Thunder god, Thor, dressed up as a bride with a ring of keys at his belt. Caption: Illustration of Thor as a bride by Elmer Boyd Smith, from "In the Days of Giants: A Book of Norse Tales" (1902).

These texts might reflect a pagan Norse truth. They might equally reflect the values of medieval Christian world in which they were written. We can't tell.

What the keys do reflect are the values of 19th-century Victorian society, when upperclass women were confined to the home and told to concern themselves only with children, church, and kitchen. In Swedish history books in the 1860s, the myth of the Viking housewife replaced an earlier historical portrait of Viking women who were strikingly equal to Viking men. This Victorian version of Viking history has been presented since then as truth, but it is only one interpretation.

Surely archaeology backs up the well-known image of the Viking housewife with her keys, you insist.

It does not. Keys have been found in some women's graves. But they are not common, nowhere near as common as housewives. Against the 3,000 Viking Age swords that have been found in Norway, archaeologist Heidi Berg in 2015 sets only 143 keys, half of which were found in men's graves. In Denmark, Pernille Pantmann reported in 2011 that only nine out of 102 female graves she studied contained keys, and none of these "key graves" otherwise fit the model of "housewife."

Calling keys the symbol of a Viking woman's status, these and other researchers now say, is "an archaeological misinterpretation," "a mistake," "a myth"—and a dangerous one.

Caption: For a new look at the meaning of keys, see "Women in the Viking Age" on the website of the Danish National Museum, where this image comes from.

Caption: For a new look at the meaning of keys, see "Women in the Viking Age" on the website of the Danish National Museum, where this image comes from. By accepting the 19th-century stereotype of men with swords and women with keys, we legitimize the idea that women should stay at home.

We reduce the role models for every modern girl who visits a museum or reads a history book.

We make it easy to dismiss as unrealistic the warrior women found in every kind of medieval text that depicts Viking society—history, law, saga, poetry, and myth—and which have been attested to archaeologically since 2017, when the famous warrior grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden was DNA tested.

How would I re-interpret the role of women in Viking society? I try to answer that question in my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women . To learn more, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on November 03, 2021 08:00

October 27, 2021

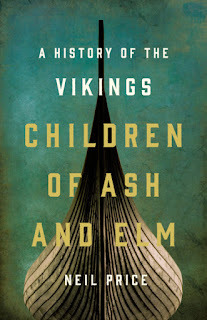

Children of Ash and Elm

If you don't lurk on Academia.edu, as I do, looking for scholarly articles on Vikings, you'll be shocked by the depiction of the Viking world in Neil Price's

Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings

(Basic Books, 2020). And even if you do think you're caught up on the latest thinking and research on who the Vikings were and how their society was organized, you still need to read this book.

If you love Norse mythology and the Icelandic sagas and the stories they tell about the Vikings, you will be as eager as I am to separate the runes and the names of our heroes from the white supremacist neo-Nazis who are trying to co-opt them. Price's Children of Ash and Elm gives you the facts you need.

It's time to put an end to the idea that the Viking world was ruled by white men.

"The Viking world this book explores," Price writes, "was a strongly multi-cultural and multi-ethnic place, with all this implies in terms of population movement, interaction (in every sense of the word, including the most intimate), and the relative tolerance required. This extended far back into Northern prehistory. There was never any such thing as a 'pure Nordic' bloodline, and the people of the time would probably have been baffled by the very notion.... They were as individually varied as every reader of this book."

"The Viking world this book explores," Price writes, "was a strongly multi-cultural and multi-ethnic place, with all this implies in terms of population movement, interaction (in every sense of the word, including the most intimate), and the relative tolerance required. This extended far back into Northern prehistory. There was never any such thing as a 'pure Nordic' bloodline, and the people of the time would probably have been baffled by the very notion.... They were as individually varied as every reader of this book."

It's also time to put an end to the idea that the Viking culture is one we want to live in today. These were people who participated in "ritual rape, wholesale slaughter and enslavement, and human sacrifice," Price says. "Anyone who regards them in a 'heroic' light needs to think again."

None of which means we shouldn't study them, tell their stories, or thieve from their ideas.