Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 9

November 19, 2014

Ayla's Dream Is to Study the Art of Riding in Iceland

When I first met Ayla Green, she was trying to dissolve into the back of a sofa. A beautiful 16-year-old with long blonde hair, she looked distinctly out of place in the guesthouse at Staðarhús in western Iceland last June: The person closest to her in age was her aunt, Laura Benson.

When I first met Ayla Green, she was trying to dissolve into the back of a sofa. A beautiful 16-year-old with long blonde hair, she looked distinctly out of place in the guesthouse at Staðarhús in western Iceland last June: The person closest to her in age was her aunt, Laura Benson.Laura had arrived that morning from California to teach a group of 60-year-old Americans (and one in her 30s) how to ride an Icelandic horse as part of the America2Iceland tour I was leading. Ayla had come along to help--and to get to know Iceland better.

She sat on the sofa, as we all chatted, and fiddled with her hair or fiddled with her phone, or maybe she was reading a book--I admit, I paid her very little mind.

Throughout the week, while our tour group took their riding lessons, she was put to work cleaning stalls or exercising young horses. Once she had to babysit. Other than "Good Morning," I don't think she and I exchanged two words.

Ayla competing at the CIA Open in Santa Ynez, California.

Ayla competing at the CIA Open in Santa Ynez, California.Then, one morning, as our excited group of beginners was heading out for their first-ever Icelandic trail ride, our hostess, Linda, flagged down Laura and Ayla. Laura waved me over. A pair of German tourists, also staying at the guesthouse, had booked a horseback ride for that morning and Linda had just realized, watching Laura about to disappear down the drive, that she had no one who could lead them. (Linda herself is a horse trainer, but had to watch the children that day.)

The Germans said they were good riders. They could not reschedule: They had to catch a plane. Could Ayla babysit? Laura had a better idea: Why not let Ayla lead the ride? She didn't know the trail--but I did. We agreed. I'd show them the way, but Ayla would be in charge of making sure the Germans had a safe and pleasant ride.

Ayla and I led our horses back to the barn, where the two Germans were waiting. Somehow, on the short way there, she was transformed from a shy teenager in the shadow of her aunt into a confident and confidence-inspiring riding instructor herself.

Ayla competing at the CIA Open in Santa Ynez, California.

Ayla competing at the CIA Open in Santa Ynez, California.She took the two horses Linda had suggested out of their stalls and helped the Germans groom them and properly tack them up. She asked polite questions to assess their riding skill (something that many tourists exaggerate). These two, we learned, were experts--they owned a riding stable in Germany and had competed on Icelandic horses. Still, Ayla left nothing to chance, but had them warm up their horses in the indoor arena while she watched to make sure horse and rider were well matched.

They were, and we headed down the trail. Ayla had not been intending on leading a tour group. She was riding a young horse with very little training--and a lot of spirit--who tended to spook at just about everything. Ayla didn't let that bother her. She kept her horse even with mine (a very solid trekking horse), every now and then drifting back to check that our guests were enjoying themselves. It soon was apparent that I was the least experienced rider of the group (though I've owned and ridden Icelandic horses since before Ayla was born).

The road beside the river at Stadarhus.

The road beside the river at Stadarhus.We rode along the stream on a narrow track, passing our beginners' group on their way back, then waded the stream to pick up a gravel road that serviced some summerhouses. We stopped briefly to rest the horses in a grassy glade surrounded by birch thickets, the snow-streaked mountains brushing the sky all around us. Then we went back by a different path, crossing the stream again just above a waterfall. Once back on the riding track, heading home, we picked up speed and had an exhilarating run to the barn, still riding two-by-two.

When I said goodbye to Ayla Green after that week at Staðarhús, I knew I'd met an exceptional young horsewoman--and one I'd be hearing more about in the small world of Icelandic horses in the U.S. So I was happy to learn recently that Ayla has decided to pursue her dream of "building a life around this wonderful breed."

Through the website GoFundMe, she is raising money so that she can afford to attend Hólar University, Iceland's premier school for equestrian science, beginning in the fall of 2015. "This university specializes in the training of the Icelandic horse," she explains. "Hólar is also one of the most respected schools where one can learn horsemanship with Icelandic horses."

Through the website GoFundMe, she is raising money so that she can afford to attend Hólar University, Iceland's premier school for equestrian science, beginning in the fall of 2015. "This university specializes in the training of the Icelandic horse," she explains. "Hólar is also one of the most respected schools where one can learn horsemanship with Icelandic horses."What she has failed to add is that her aunt, Laura Benson, was the first American to graduate from Hólar with a B.S. degree.

If you ride Icelandic horses and hope to see the breed flourish in North America, as I do, I hope you'll join me in adding a few dollars to Ayla's fundraising campaign. She's not offering T-shirts or coffee mugs (this isn't Kickstarter), but if you're lucky, you'll meet her in Iceland and she'll take you for a ride.

Share Ayla's dream at http://www.gofundme.com/aylagreen

Photos of Ayla by Heidi Benson

Photos of Ayla by Heidi Benson

Published on November 19, 2014 11:21

November 12, 2014

America2Iceland's 2015 Trekking Bootcamp

In late July, with the help of America2Iceland--and you, if you're game--I'm going to recreate my favorite scene from my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse.

In late July, with the help of America2Iceland--and you, if you're game--I'm going to recreate my favorite scene from my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse.Be prepared to ride fast and far, to get tired and probably wet, and to have an adventure you'll never forget riding on the silvery sands beneath the great glacier Snæfellsjökull, or "Snow Mountain Glacier," on Iceland's west coast.

The year before I bought my horses, I spent the summer in an abandoned house on the edge of the Longufjörur, or Long Beaches trail, a 40-mile riding trail uncovered only at low tide. The route, along the south side of Snæfellsnes, has been in use since the Saga Age. It cuts the mouths of several rivers, some of them deep-channeled salmon streams, others edged with quicksand. The safe paths shift from storm to storm, while the force of the wind and its direction, and the fullness of the moon, decide how fast a rider must cross.

"It's a dangerous path," my neighbor, Haukur of Snorrastaðir, told me, "if you don’t know the tides." But one memorable day he lent me two of his best "family" horses, Elfa and Dögun, and let me go with him and the group of riders he was leading over the sands.

At last the tide was low, I wrote in A Good Horse Has No Color:

At last the tide was low, I wrote in A Good Horse Has No Color:We opened the paddock gate and let the swirl of color resolve itself into free-running horses. First after them went Haukur on Bjartur, the cream-colored gelding he always rode. His hand horse, a black, he led at his knee, and I did my best to mimic him, riding Elfa and ponying Dögun, though I kept losing my right stirrup: with her every step Dögun banged into my heel.

We rode from the farm beside the River Kaldá on a path so deep our feet brushed the rim of the ruts and grass swished against our boot tops. The ponying got easier when the deep path emptied out onto a black-pebbled beach. I relaxed, took great drafts of the salty air, and settled in to enjoy the ride. This was living, Haukur said. This was Iceland.

We crossed over mudflats pocked with airholes and headed for several grass-topped islands abandoned by the tide like a pod of stranded whales. A sea eagle lifted off one of the islands as we approached and scolded us with a high-pitched cackle. Geese flew over, banking, startled. We rode north onto the sandbar, across some grassy flats, back out through the sucky mud to the hard wet sand, whose color ranged from black to coffee-colored to tawny to gold.

We crossed over mudflats pocked with airholes and headed for several grass-topped islands abandoned by the tide like a pod of stranded whales. A sea eagle lifted off one of the islands as we approached and scolded us with a high-pitched cackle. Geese flew over, banking, startled. We rode north onto the sandbar, across some grassy flats, back out through the sucky mud to the hard wet sand, whose color ranged from black to coffee-colored to tawny to gold. We rested the horses on a grassy hillside out of sight of a nearby farmhouse. The buzz had been growing in our ears for some time before any of the riders registered what it was (some of us were half asleep with our hats over our eyes). A plane was coming in low. It zoomed over our hillside, making us sit up and snatch at the nearest bridles. A little red and white two-seater, the craft rose and banked steeply over the sea, then turned its nose toward us and dove again. Again it turned, and now it sparked Haukur's ire. He waved his cap and hollered at it.

The other riders had mounted their horses and were circling around the spares. Again the plane passed low over us, then dipped even lower until it was skimming the mudflats. Haukur's holler suddenly turned concerned. The pilot would crash, would kill himself if he tried to land in that soft mud. Haukur thrashed his hat in the air again and began riding toward the beach. The plane lifted slightly, sailed across a wide tidal stream, and came down at last on the sandbar a quarter-mile offshore.

The other riders had mounted their horses and were circling around the spares. Again the plane passed low over us, then dipped even lower until it was skimming the mudflats. Haukur's holler suddenly turned concerned. The pilot would crash, would kill himself if he tried to land in that soft mud. Haukur thrashed his hat in the air again and began riding toward the beach. The plane lifted slightly, sailed across a wide tidal stream, and came down at last on the sandbar a quarter-mile offshore.Haukur shook his head. There must be something wrong, he said. The pilot must be out of gas. There was no way off that sandbar, and the tide was rising. He turned and looked over his riders, all quite experienced except for me. We'll have to rescue him, he said. We'll have to swim.

Down he rode toward the stream and, without hesitating, urged his two horses in. The water rose above his thighs. The horses lifted their heads and bared their teeth, all but their heads and necks underwater. The loose horses and the other riders followed, but my hand horse balked and Elfa skittered farther down the shore before I could steer her in—with the result that she missed the sloping bank and was instantly swimming.

My boots filled up. The current pressed hard against my right leg and tugged away at my left. I lost my stirrups. The spare horse I was ponying began swimming with the stream, dragging her rein around behind my back. Elfa began turning seaward as well, her swimming a strange rolling motion. I began to panic.

My boots filled up. The current pressed hard against my right leg and tugged away at my left. I lost my stirrups. The spare horse I was ponying began swimming with the stream, dragging her rein around behind my back. Elfa began turning seaward as well, her swimming a strange rolling motion. I began to panic.Rationally I knew that what we were doing was quite ordinary. Horses have long been called "the bridges of Iceland," and Icelanders still will not go out of their way to stay dry crossing a bit of a brook. The English painter Samuel Waller wrote of a day in 1874 when he crossed 40 streams. He warned, "The great thing to beware of is looking at the water. You lose your head at once if you do so, as the eddies swirl around you so rapidly." If you should become unseated, he advised, "strike out for the bank at once and leave the animals to take care of themselves. To be engulfed with a horse in the water is a very complicated piece of business."

And I had two horses. It occurred to me suddenly that I was not "used to horses" at all.

And I had two horses. It occurred to me suddenly that I was not "used to horses" at all.I quickly took inventory and concluded I was hardly a rider. Rather than standing "firm in the stirrups," as Waller suggested, I had no stirrups. My hand horse was tipping my balance awry with her rein tight behind my back. Determined at all costs to stay on, I had cocked my feet up to lessen the drag on my water-filled boots and was clenching my knees, my hands in a death-grip on the reins.

In spite of all this, Elfa was swimming steadily, her ears back, but otherwise not noticeably upset that we weren't gaining the shore. Suddenly I knew what to do. Keeping firm hold of my hand horse, I dropped Elfa's rein, grabbed onto her mane, and relaxed. Immediately, as if I'd called out in a language we both understood, Elfa's head swung toward shore. My hand horse fell behind and swam nicely along after us. Soon we had sand under our hooves. Elfa kicked up and we came splashing out onto the beach in a fine smooth tolt. We charged over to where the other horses waited and I gratefully slid off.

My first thought was to empty out my boots. Someone handed me a beer. I chugged it down, standing on one foot, holding two fidgeting wet horses and a boot full of water. Slowly I made out the tale. The pilot was the boyfriend of one of our riders and had flown out to treat her to a cold drink.

My first thought was to empty out my boots. Someone handed me a beer. I chugged it down, standing on one foot, holding two fidgeting wet horses and a boot full of water. Slowly I made out the tale. The pilot was the boyfriend of one of our riders and had flown out to treat her to a cold drink.Hardly had the absurdity of the situation sunk in when I realized the riders were remounting. The plane's engine was being revved up. Someone grabbed my empty bottle and I was up and off, Elfa stretching out behind Haukur's Bjartur in the incredible gait called the flying pace—fast enough that my hand horse had to gallop to keep up, yet still Bjartur outdistanced us. We eased back into a canter and let the loose horses catch us, while our little beer-plane scooted by overhead, waggled its wings, and disappeared….

Never would I have imagined that, 17 years later, I would be leading riding tours in Iceland myself. But in 2013 I started doing so for America2Iceland, which is owned in part by the riding instructor and horse trainer Guðmar Pétursson and based at his farm of Staðarhús in the west of Iceland.

Photo by Rebecca Bing for America2IcelandIn 2015 Guðmar and I will be recreating the beach ride I wrote about in A Good Horse Has No Color, riding on the sands beneath the great glacier Snæfellsjökull on the America2Iceland Trekking Bootcamp Tour, July 27 to August 2.

Photo by Rebecca Bing for America2IcelandIn 2015 Guðmar and I will be recreating the beach ride I wrote about in A Good Horse Has No Color, riding on the sands beneath the great glacier Snæfellsjökull on the America2Iceland Trekking Bootcamp Tour, July 27 to August 2.There’s only room for 12 riders, so sign up soon if you want to come with me. Look here for more information:

http://america2iceland.com/trips/riding-bootcamp-level-1/

Note that I cannot guarantee there will be a plane to deliver beer to us on the sands, as there was in the book. But I can guarantee a memorable ride.

(Don't ride? Then take a look at my other America2Iceland tour, "Song of the Vikings," here: http://america2iceland.com/trips/song-of-the-vikings/)

Published on November 12, 2014 07:56

November 5, 2014

Sheep-Shearing Day at Hestholl Icelandics

The hardest part of Sheep-Shearing Day seemed to be getting the halters on. A sheep halter is not like a horse halter--at least, not like any horse halter I'm used to. There were no buckles, no obvious browbands.

The hardest part of Sheep-Shearing Day seemed to be getting the halters on. A sheep halter is not like a horse halter--at least, not like any horse halter I'm used to. There were no buckles, no obvious browbands.The sheep halters were a noose of bright nylon rope that, looped and twisted correctly, gave you a secure grip on an obstreperous ewe but--twisted incorrectly--let her easily escape to scramble into the yard and glare at us with her yellow eyes while Jill enjoined the youngsters not to scream and not to chase her and a few sheep-savvy helpers made a loose ring behind her and urged her gently back toward the rest of her flock, penned in the open barn, where the professional sheep-shearer stood waiting in the middle of a bright green tarp. The escapee sauntered within his reach, was deftly snagged by one horn and up-ended to sit on her bottom between the shearer's knees--at which the ewe immediately relaxed and let him get on with the task of stripping her of her heavy fleece.

It was Sheep-Shearing Day, after all. The local 4H Club was there to help, though I only noticed one club member who was much help at all: She was an expert at toenail trimming. Most of us had come to Jill Merkel's Hestholl Icelandics in Richmond, VT, to take photos or otherwise gawk at the sheep, which gawked back at us.

It was Sheep-Shearing Day, after all. The local 4H Club was there to help, though I only noticed one club member who was much help at all: She was an expert at toenail trimming. Most of us had come to Jill Merkel's Hestholl Icelandics in Richmond, VT, to take photos or otherwise gawk at the sheep, which gawked back at us.

The sheep were Icelandic sheep: black and white and brown and spotted. Some had horns, some were hornless, and some just had little nubs. Some were cooperative: They'd hop up onto a metal grooming stand and set their heads onto the headrest; they wouldn't fuss even when you tightened the noose that kept them there and systematically picked up each foot to trim their nails. Others fought back. They despised the stand--or were frightened of it. They refused to keep still, even when tied, jerking their legs as hard as they could to make Jill or young Eva, with the nail clippers, let go--though they didn't. They just waited out the jerking and squirming and then went on with the task.

Sheer off the wool, trim the nails, check the color of the membrane around the eyes (a way to see if the animal has worms), administer wormer, if required, dribble some insecticide along each spine to defeat the fleas, then on to the next sheep.

Sheer off the wool, trim the nails, check the color of the membrane around the eyes (a way to see if the animal has worms), administer wormer, if required, dribble some insecticide along each spine to defeat the fleas, then on to the next sheep.The shearing seemed to be the quickest step. It took the shearer about five minutes per sheep, using electric clippers. He finished 32 sheep in about four hours, and half the time he seemed to be standing there with a shorn sheep at the end of its rope and saying calmly, "Somebody take this sheep. Where's the next one?"

As soon as I arrived, having never helped with a sheep-shearing before, I was handed a sheep. It did not like me. It spun and kicked and squirmed and did all it could to get off that rope. Thankfully, the sheep-shearer knew how to halter a sheep and this one did not get loose.

My friend Linda, also new to sheep-shearing, first got the task of taking before and after photos. The "before" sheep were handsome and stout; the "after" sheep were lumpy here and skinny there, altogether awkward-looking beasts.

Later Linda got the more appealing task of stuffing the wool into sacks, each neatly labeled with the ewe's name. "The wool is still warm when you pick it up," she mused, "like a sweater someone has just slipped off."

Soon it will be spun and knitted into a sweater once again, and the ewe will grow a new fleece, to be shorn off next spring.

Visit Hestholl Icelandics online here: https://www.facebook.com/hestholl?ref=br_tf

Published on November 05, 2014 08:30

October 29, 2014

The Witch's Bridle: An Icelandic Folktale

This time of year in Iceland, the nights are getting long, clouds and rain and fog keep the days generally dark, and if you find yourself walking through a lava field in the half light and hear a fox bark, it's easy to believe in ghosts and trolls and witches.

This time of year in Iceland, the nights are getting long, clouds and rain and fog keep the days generally dark, and if you find yourself walking through a lava field in the half light and hear a fox bark, it's easy to believe in ghosts and trolls and witches.Or, if not to "believe," at least to scare the wits out of yourself remembering the old stories. My favorites in this genre of Icelandic folktales are the ones about the Witch's Bridle.

In one story, a young farmhand, nearly asleep, feels his mistress place in his mouth the bit of a bridle. Immediately he is compelled to follow her outside, where she mounts him like a horse. She rides him "over hill and dale, over rocks and rubble. To him it seems as if he is wading through sea foam." They stop at the edge of a crater, "which yawns, like a great well, down into the earth," and she ties her "horse" to a stone and disappears into the pit.

As in all of these tales of travel to the Otherworld, the witch-ridden boy manages to pull off the magic bridle and follow her to spy on her doings. In some stories, like this one, her destination is a grand palace in Alfheim (Elfland), where she is greeted like an honored guest. In other tales, she is riding for the Black School in Heim-Utspell (Land of Fire), where she will receive magical training at the hands of Old Nick himself. (Alternatively, Satan's Black School is in Paris!)

The Witch's Bridle transforms not only people, but individual bones into serviceable horses. Often these are bones of horses--shoulder-bone, jawbone, legbone--but occasionally they are human bones. The famous churchman Sira Halfdan of Fell once bridled the hip-bone of a man, turning it into "a willing horse that could go as well over the sea as on land." It is also said that the Witch's Bridle is the only way to fully tame a nykur or nennir, the magical white horses that come out of the sea.

To make a Witch's Bridle, one story says, cut three narrow strips of skin off the spine of a newly dead corpse and twist each one while pulling it through a hole in a skull--usually the ear hole. (The witch would use an already prepared skull, rather than that of the fresh corpse; of course she'd have one at hand.) Braid the strips into reins. Next, flay off the dead man's scalp and fashion it into the head-piece of the bridle, with the hair left on. The bones at the root of the tongue (the hyoid bones) are used for the bit, while the hip bones make the cheek pieces--the Witch's Bridle follows the form of the classic Icelandic bridle, with its large cheek pieces.

When properly pieced together, the bridle can be fastened onto "any man or beast, stock or stone, and it will go quicker than lightning wherever one wants to go." In practice, however, the bridle must have been programmed by magic words to go to one particular destination, for in no instance in the tales does the witch-ridden bone, beast, or man deviate from course--even when the rider is not the witch, as in the tale above, in which the farmhand turns the tables on his mistress and bridles her for the ride back home from Elfland. Perhaps the spell was recited while the skin for the reins was being pulled through the ear hole, thus allowing the skin to "hear" the instructions.

Interestingly, although many magical objects have been retrieved from graves in Iceland, no artifacts resembling the collection of skin and bones of a Witch’s Bridle have been found--yet.

For more shakes and shivers (and a few love spells), read last year's Halloween post about the Icelandic Witchcraft Museum: http://www.nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2013/10/icelandic-witchcraft.html

Published on October 29, 2014 05:45

October 15, 2014

Gerri Griswold's "Iceland Affair"

Even her friends call her "peculiar." Her Facebook pages (yes, she maintains several) are littered with selfies taken in the crapper at Logan Airport or the big bathtub in her back yard (censored by soap bubbles). She drivels on and on about her juicing diet and her real job (one of them) as a radio station traffic reporter. She has a pet pig. She's passionate about bats and porcupines, which she rehabilitates for the White Memorial Conservation Center.

Even her friends call her "peculiar." Her Facebook pages (yes, she maintains several) are littered with selfies taken in the crapper at Logan Airport or the big bathtub in her back yard (censored by soap bubbles). She drivels on and on about her juicing diet and her real job (one of them) as a radio station traffic reporter. She has a pet pig. She's passionate about bats and porcupines, which she rehabilitates for the White Memorial Conservation Center.Where am I going with this? To Iceland, of course, for Gerri Griswold is passionate, too, about the land of Fire and Ice, which is how our paths crossed. Gerri's is the spirit behind Iceland Affair--and that's what makes this quirky all-day, all-Iceland festival in Connecticut so much fun.You just never know who you might meet and what you might learn.

According to a press release for Iceland Affair, which Gerri has almost single-handedly put together near her home in Connecticut each year for the last five, Gerri Griswold fell "hopelessly in love with Iceland on her first trip in May 2002 and has since traveled there 34 times."

Reading that made me seriously jealous. I fell in love with Iceland in 1986 and I've only racked up 18 return trips. How does she do it?

One answer is, she doesn't sleep. I learned that the hard way, sharing a room with her for a June night in Iceland in 2013, where she was up until at least 3 a.m. editing photos to post on Facebook. She once was a professional chef, Gerri told me. "I'm used to having five burners going at once."

To fund (or fuel) her Iceland habit, Gerri established a travel agency, which I wrote about in a previous blog post. [Read it here: http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2013/09/krummi-travel.html] I toured with her group for about 24 hours, during which time I hiked along the rim of a volcanic crater at midnight, swam in a natural hotspring, visited sulfur pots and lava formations, learned about lichens, found the ram with the biggest horns in Iceland, and listened to the stirring voices of a men's choir in the elegant surroundings of a bird museum while munching on Icelandic cheese. I think that was more than five burners going at once.

And it was fun. Gerri's company pairs an elegant logo of a raven with a name that, while it does mean "raven," is pronounced by every American as "crummy": Krummi Travel. The company logo is No crybabies, cranks, or pantywaists allowed. What's a pantywaist? I spent that whole day touring with them and didn't have the nerve to ask.

Still don't know--and don't tell me, because I'm taking part in another of Gerri's productions this weekend: the Fifth Annual Iceland Affair in Winchester Center, CT.

Inside the Winchester Center Grange on Saturday, October 18, from 10 to 5, will be a full slate of lectures and presentations. At noon, I'll be speaking on my book A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse. There will be talks on Iceland's geology and its currently active volcano, Barðarbunga. The breeder of Icelandic goats whose farm we all saved from the dragons (bankers) with the Indiegogo campaign will be there, as will experts on Icelandic gyrfalcons and Icelandic pop music. [Read more about the goats here: http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2014/08/save-icelandic-goat.html]

Downstairs at the Grange will be free food-tastings all day: Icelandic hot dogs, dried fish, chocolate, skyr, and more. Vendors will be selling Icelandic sweaters and vinaterta and books (mine, of course).

Outside on the Winchester Center Green will be a veritable Icelandic petting zoo: Icelandic horses, Icelandic sheep, Icelandic sheepdogs, Icelandic chickens--yes, there really are Icelandic chickens.

"Anything worth doing is worth overdoing," Gerri stresses.

Finally, at 8 pm, there's a concert (which is not free; Gerri's got to pay for this event somehow). The Fire and Ice Music Festival at Infinity Hall in Norfolk, CT will feature Icelandic musicians Lay Low, Svavar Knutur, Myrra Ros, Agnes Erna, Snorri Helgason, Bjorn Thorodssen, and Kristjana Stefansdottir, playing everything from pop to folk to jazz. [You can read bios of the artists (and buy tickets, if there are any left) here: http://icelandaffair.com/musicians-2/]

"Surprises are in store for every guest attending--and for the artists," Gerri concludes.

I'm not surprised.

Published on October 15, 2014 08:21

October 8, 2014

Not Leif Eiriksson Day, but Gudrid the Far-Traveler Day

Tomorrow, October 9, is Leif Eiriksson Day, when people of Scandinavian heritage and Viking enthusiasts like me celebrate the fact that the Vikings explored North America 500 years before Columbus.

Tomorrow, October 9, is Leif Eiriksson Day, when people of Scandinavian heritage and Viking enthusiasts like me celebrate the fact that the Vikings explored North America 500 years before Columbus.While I whole-heartedly support the celebrations, I wonder, Why does Leif get all the credit? As I wrote on this blog before--in 2012 and 2013--I think we should celebrate "Gudrid the Far-Traveler Day," instead. Leif spent a winter in the Viking's Vinland and never went back. His sister-in-law, Gudrid, lived there three years and bore a child in the New World.

Gudrid is mentioned in both of the medieval Icelandic sagas about the Vikings' adventures in Vinland, or Wine Land, around the year 1000. Experts believe the stories in The Saga of the Greenlanders were first collected by Gudrid's great-great-grandson, Bishop Brand, in the 1100s. The Saga of Eirik the Red was commissioned about a hundred years later by another of Gudrid's many descendants, Abbess Hallbera, who oversaw a convent in northern Iceland.

The two sagas don't agree on the particulars of Gudrid's life, and they don't tell us very much about her. She was "of striking appearance," intelligent, adventurous, and friendly. She could sing and she was Christian. She was born in Iceland, married in Greenland, explored Wine Land, returned to Iceland and raised two sons, took a pilgrimage to Rome, and became one of Iceland's first nuns. Many Icelanders today trace their ancestry from her.

Over the last 50 years, archaeologists have proved more and more of her story true. In Greenland, they uncovered Eirik the Red's Brattahlid and the church built there by his wife, Thjodhild. They uncovered the house at Sand Ness where Gudrid's husband died.

Over the last 50 years, archaeologists have proved more and more of her story true. In Greenland, they uncovered Eirik the Red's Brattahlid and the church built there by his wife, Thjodhild. They uncovered the house at Sand Ness where Gudrid's husband died.On the far northwestern tip of Newfoundland, near a fishing village called L'Anse aux Meadows, they found three Viking houses. This small settlement is now thought to be the gateway from which the Vikings explored North America. Among the Viking artifacts found there was a spindle whorl, proving a Viking woman had been on the expedition.

Three white walnuts, or butternuts, found at L'Anse aux Meadows prove the Vikings sailed well south, to where butternut trees—and the wild grapes for which Wine Land was named—then grew. The most likely spots seem to be near the mouth of the Miramichi River in New Brunswick, Canada, where there was a large Native American settlement at the time.

In 2001 a team of archaeologists began working in Skagafjord, the valley in northern Iceland where Karlsefni came from. I volunteered on the project one summer as we uncovered a Viking Age house on the farm called Glaumbaer, where the sagas say Gudrid finally made her home. The floorplan of the house looked like no other found in Iceland. It most closely resembled a house at L'Anse aux Meadows.

I told the story of my summer working on the archaeological team in The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman, which was published by Harcourt in 2007. I thought then that I had written all I could about Gudrid the Far-Traveler. Her spirit disagreed. As soon as that book came out, I began writing a new one.

I told the story of my summer working on the archaeological team in The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman, which was published by Harcourt in 2007. I thought then that I had written all I could about Gudrid the Far-Traveler. Her spirit disagreed. As soon as that book came out, I began writing a new one.My young adult novel, The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler, will be published in Spring 2015 by namelos. I look forward to sharing the process with you.

To read my earlier posts about Leif Eiriksson Day, see:

http://www.nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2012/10/who-discovered-america.html and

http://www.nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2013/10/leif-eiriksson-day.html

Published on October 08, 2014 09:00

October 1, 2014

Icelandic Toys

In the old days, when Icelanders lived in turf houses like this one, how did the children play?

In the old days, when Icelanders lived in turf houses like this one, how did the children play?The English traveler Alice Selby visited Iceland in 1931. During the week she spent on a farm in a narrow northern valley, she writes, "the weather grew steadily worse. At first it was bright but cold. Then it grew cloudy, and then the rain began. After that it grew still colder, the rain turned to snow and sleet, and the bitterest wind blew unceasingly. My first impression of the Icelandic countryside was one of complete gloom."

Then one day, out on a walk, she met a local man who shared with her a secret: "When we drew near the farm where he lived, he led me out of the way to a sheltered hollow and showed me a little village of toy houses made by children from the farm. The tiny mud houses were roofed with turf and fenced with sheep's horns. There were flowers, daisies and little pink arenaria planted in the gardens, and there was even a cemetery with crosses made from match sticks. I felt unaccountably cheered."

Selby doesn't mention the animals at the children's farm, but I came across this extensive farm-animal set one year when I visited the Skogar Folk Museum in southern Iceland. Before Legos there were bones. According to Jónas Jónasson frá Hrafnagili, in his book on Icelandic folkways, the knucklebones of sheep were sheep, the knucklebones of cows were cows, while the legbones of sheep were horses, though jawbones were sometimes horses too, like this well-laden packhorse:

In the airline magazine, on the way home from that trip, I read about a new toy set designed by Róshildur Jónsdóttir, "Something Fishy." According to the magazine, it's "a model-making kit including cleaned bones from fish heads and paint … The kit doesn't contain any instructions; it's up to the creative mind of each user what they want to create: spaceships, angels, or elves--anything is possible. A great alternative to virtual games and plastic toys." Here's an example:

Róshildur was inspired, the magazine says, by "the old days," when children's favorite toys were bones. You can read more about "Something Fishy" here: http://blog.icelanddesign.is/somethin...

Published on October 01, 2014 09:38

September 3, 2014

Snorri and the Volcanoes

There’s a volcano erupting in Iceland again. They happen quite often—I saw one in 2010, when I took these photos, just before it shut down European airspace with clouds of ash.

There’s a volcano erupting in Iceland again. They happen quite often—I saw one in 2010, when I took these photos, just before it shut down European airspace with clouds of ash.Eruptions are a fact of life for Icelanders. A big one happened in 871 (plus or minus two years): The dark layer of ash it sprinkled over much of the country now helps archaeologists date the time of the first settlement of Iceland to just about that time, using a technique called tephrachronology. Another big eruption in 1104 laid down a layer of ash in a conveniently lighter color, which helps archaeologists bracket the Viking Age.

Geologists estimate ten volcanic eruptions per century took place between Iceland’s founding in the 870s and when the Icelandic sagas began to be written in the early 1200s. Then the frequency increased to about fifteen per century.

So why are eruptions essentially missing from the sagas?

Only once, in Kristnisaga, the Saga of Christianity, is an eruption a plot point. The chieftains were meeting in the year 1000 to debate whether Iceland should become Christian, as the king of Norway insisted. A rider broke into the proceedings to shout, “Earth fire! In Olfus!” A volcano had erupted on one of the chieftains’ farms.

“It is no wonder. The gods are angry at such talk,” people muttered.

“And what were the gods angry about,” said one chieftain, gesturing to the black, ropy lava all around, “when they burned the wasteland we’re standing on now?”

The great Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, subject of my book, Song of the Vikings , grew up in the shadow of a volcano. Hekla, the cloud-hooded mountain known in the Middle Ages as the Mouth of Hell, erupted twice during Snorri’s lifetime. Possibly three times, for the church annals record “darkness across the south” the year he turned five.

The annalist knew what caused that darkness. The Saga of Bishop Gudmund, written in the mid-1200s, contains this explanation (translated here by my friend Oren Falk of Cornell University):

“There are mountains in this land, which emit awful fire with the most violent hurling of stones, so that the crack and crash are heard throughout the country.… Such great darkness can follow downwind from this terror that, on midsummer at midday, one cannot make out one’s own hand.”

To the east of Snorri’s childhood home rose the ice cap of Eyjafjallajokull--from under which erupted the volcano I visited in 2010. Snorri would have seen only tier upon tier of vast blank whiteness, a glimmering dome mingling with the clouds so that on some days the horizon disappeared.

But Snorri’s contemporaries were aware that active volcanoes lurked beneath the ice. A thirteenth-century poet told how “glaciers blaze,” “coal-black crags burst,” “fire unleashes storms,” and “a marvelous mud begins to flow from the ground.” (Again, in Oren’s translation.)

Lava also spouted from the sea in Snorri’s lifetime, forming rugged black islands that rose above the waves only long enough for a few intrepid souls to row out and give them a name, the Fire Islands.

It is not surprising, then, that volcanoes also informed Snorri’s version of the creation of the world.

In the beginning, Snorri wrote in his Edda, there was nothing. No sand, no sea, no cooling wave. No earth, no heaven above. Nothing but the yawning empty gap, Ginnungagap. All was cold and grim.

Then came the giant Surt with a crashing noise, bright and burning. He bore a flaming sword. Rivers of fire flowed till they turned hard as slag from an iron-maker’s forge, then froze to ice.

The ice-rime grew, layer upon layer, till it bridged the mighty, magical gap.

Where the ice met sparks of flame and still-flowing lava from Surt’s home in the south, it thawed and dripped. Like an icicle it formed the first frost-giant, Ymir, and his cow.

Ymir drank the cow’s abundant milk. The cow licked the ice-rime, which was salty. It licked free a handsome man and his wife. They had three sons, one of whom was Odin, the ruler of heaven and earth, the greatest and most glorious of the gods: the All-father.

Odin and his brothers killed Ymir. From his giant body they fashioned the world: His flesh was the soil, his blood the sea. His bones and teeth became stones and scree. His hair were trees, his skull was the sky, his brain, clouds.

From his eyebrows they made Middle Earth, which they peopled with men, crafting the first man and woman from an ash tree and an elm they found on the seashore.

So Snorri explains the creation of the world in the beginning of his Edda. Partly he is quoting an older poem, the “Song of the Sibyl,” whose author he does not name. Partly he seems to be making it up—especially the bit about the world forming in a kind of volcanic eruption, and then freezing to ice.

This part of the myth cannot be ancient. The Scandinavian homelands--Norway, Sweden, and Denmark--are not volcanic. But there is nothing so characteristic of Iceland as the clash between fire and ice.

Published on September 03, 2014 06:25

August 6, 2014

Save the Icelandic Goat

When the Vikings settled Iceland in the late 800s, they brought sheep, cows, horses, goats, pigs, hens, geese, dogs, cats, mice, lice, fleas, beetles … Archaeologists have found signs of all these in the detritus of a Viking Age house.

When the Vikings settled Iceland in the late 800s, they brought sheep, cows, horses, goats, pigs, hens, geese, dogs, cats, mice, lice, fleas, beetles … Archaeologists have found signs of all these in the detritus of a Viking Age house. Go to Iceland today and you can ride a Viking horse. You can buy a sweater made from Viking sheep's wool. You can eat cheese from the milk of Viking cows and--if you hurry--Viking goats.

We could also talk about Viking dogs and Viking chickens, but it's the goats I'm worried about.

There's only one farm left in Iceland that specializes in raising Icelandic goats, and it's going on the auction block next month. Háafell in Borgarfjord--aka the Icelandic Goat Conservation Center, www.geitur.is--is in foreclosure. Unless they can raise $90,000 in a month, their 400 goats will go to the slaughterhouse. That's about half the total population of Icelandic goats in the world.

If Háafell fails, we'll lose an important link to the Viking world.

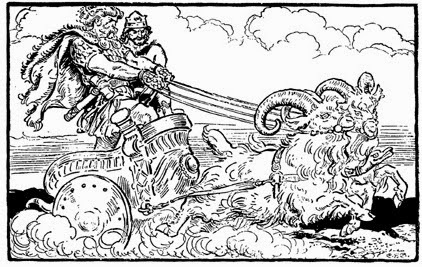

Thor the Thunder god will not be happy.

Goat is what Thor eats for dinner, according to Snorri's Edda. The two goats that pull Thor's chariot allow him to butcher and boil them every night. Provided that he saves every bone and wraps them up in the skins, unbroken, the goats will come back to life in the morning.

The heroes in Valhalla will also not be happy. There, a magic goat produces endless vats of mead instead of milk for them to drink.

And what, without goats, would make the goddess Skadi laugh?

In one of Snorri's funniest tales, Loki was caught by a giant eagle who dragged him through treetops and bounced him on stony ground. "Stop!" cried Loki, "and I'll give you the goddess Idunn and her golden apples, source of the gods’ immortal youth."

The gods began to grow old and gray. Forced to confess, Loki was ordered to retrieve Idunn. He borrowed Freyja’s falcon cloak and flew to Giantland. Learning the giant was out, Loki turned Idunn into a nut, clasped her in his talons, and took off for Asgard. When the giant came home to find his prize missing, he transformed into giant-eagle shape and went after Loki, "and he caused a storm-wind by his flying."

The gods stacked a great pile of wood in the yard of Asgard. As soon as Loki the falcon flew over the wall, they torched the stack. The giant eagle's feathers caught fire. He fell to earth, in giant form, and Thor killed him with one whack of his hammer.

It's to compensate for this killing that the giant’s daughter Skadi was allowed to marry one of the gods. She also demanded they make her laugh; she considered it quite impossible. "Then Loki did as follows: he tied a cord round the beard of a certain nanny-goat and the other end round his own testicles, and they drew each other back and forth and both squealed loudly. Then Loki let himself drop in Skadi’s lap, and she laughed."

It's to compensate for this killing that the giant’s daughter Skadi was allowed to marry one of the gods. She also demanded they make her laugh; she considered it quite impossible. "Then Loki did as follows: he tied a cord round the beard of a certain nanny-goat and the other end round his own testicles, and they drew each other back and forth and both squealed loudly. Then Loki let himself drop in Skadi’s lap, and she laughed."If that's not a reason to save the Icelandic goat from extinction, I don't know what is. Click here to go to the IndieGoGo site and get yourself a coffee mug:

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/save-the-icelandic-goat-from-extinction

Published on August 06, 2014 09:10

July 1, 2014

The Names of the Week

Why did I write a biography of a 13th-century Icelandic chieftain who was murdered cowering in his cellar? Tonight I'm giving a talk to a book club in Burlington, Vermont, and I know that's one of the questions they'll ask me. Here’s one answer:

Why did I write a biography of a 13th-century Icelandic chieftain who was murdered cowering in his cellar? Tonight I'm giving a talk to a book club in Burlington, Vermont, and I know that's one of the questions they'll ask me. Here’s one answer:Have you ever wondered why Hump Day was named “Wednesday”? Or where the names Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday come from? These days of the week were named for the ancient gods Woden (or Odin), Tyr, and Thor, and the goddess Frigg or Freyja.

If it weren’t for that 13th-century Icelandic chieftain, Snorri Sturluson, we wouldn’t know much about these old gods. In about 1220, to impress a teenage Norwegian king—the same king who, 20 years later, ordered him killed—Snorri wrote a book of Norse myths called the Edda. Along with a collection of mythological poems (also confusingly called the Edda), Snorri’s book contains almost everything we know about the gods we still honor each week with the names Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday.

Tuesday is named for Tyr, the one-handed god of war. According to Snorri, Tyr stuck his hand in the mouth of a giant wolf. He was guaranteeing the gods wouldn’t double-cross the wolf when they bound him with a leash made from six things: “the noise a cat makes when it moves, the beard of a woman, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird.” Of course, the gods were lying to the wolf. They had no intention of freeing him again. So he bit off Tyr’s hand. Tyr “is not called a peace-maker” now, says Snorri, in the translation by Jean Young.

Wednesday is named for Odin, "the highest and oldest of the gods," the one with the most names and the most stories. Odin owns the hall Valhalla. He directs the Valkyries, who chose the slain on the field of battle. He is the god of poets and storytellers, the god of beer and brewing. He has two ravens, Thought and Memory, that keep him apprised of the news. I've written about the God of Wednesday (obviously) a number of times on this blog.

See, for example, the story of Odin's eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, here: http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2012/11/seven-norse-myths-we-wouldnt-have_21.html

Or the story of the mead of poetry, here: http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2012/12/seven-norse-myths-we-wouldnt-have.html

As Snorri says, "It will be impossible for you to be called a well-informed person if you cannot relate some of these great events."

Thursday is named for Thor, strongest of the gods. Thor drives a chariot pulled by two goats. He has three magical objects: a belt of strength, a pair of iron gloves, and a hammer called Mjöllnir, or "Crusher." "The frost ogres and cliff giants know when it is raised aloft, and that is not surprising since he has cracked the skulls of many of their kith and kin."

Friday is named for Freyja (or maybe for Frigg, but Snorri doesn’t tell us much about Frigg). Freyja is "the most renowned of the goddesses." She drives a chariot drawn by two cats and enjoys love poems. She cries golden tears, wears expensive jewelry, and is not particularly faithful to her husband. "It is good to call on her for help in love affairs," Snorri says.

Why should we care about these old stories? In 1909, a translator called the two Eddas “the wellspring of Western culture.” That may be an exaggeration, but the Eddas are the source of much of our modern popular culture.

The Marvel comic character Thor—and the blockbuster movies about him—are obviously based on the Eddas.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were inspired by the Eddas—and so, of course, were Peter Jackson’s films, not to mention all the fantasy-themed movies, books, and games that feature wandering wizards, fair elves and werewolves, valkyrie-like women, magic swords and talismans, talking dragons and dwarf smiths, heroes that understand the speech of birds, or trolls that turn into stone.

The Gothic novel, too, has been traced back to the Eddas.

Their influence is even felt in “high” culture, stretching from Thomas Gray (better known for “Elegy in a Country Churchyard”) in the 1750s to our latest Nobel prizewinner, Alice Munro.

And, of course, the names of these gods are on our lips four days out of every week.

Published on July 01, 2014 14:17