Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 7

September 9, 2015

Meeting the Lewis Chessmen--In Person

"If you knew what they were valued at ..."

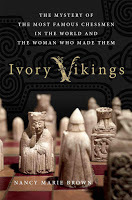

"If you knew what they were valued at ..."During a research trip to Edinburgh for my book Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them, I had hoped to meet James Robinson, who wrote an excellent guidebook on the Lewis chessmen for the British Museum. Robinson is now a curator at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS), where 11 of the chessmen reside. I received no answer to my initial query, so I planned my research trip to Edinburgh without him.

A week before I left for Scotland, I tried again. Robinson immediately responded, apologizing that my email had been buried under a deluge of others while he'd been traveling. He would be away again while I was visiting Edinburgh, so we could not meet, but "I will forward your message to request access to the pieces for you," he said.

Until that moment, it had not occurred to me that I might "request access," that is, to see and handle the chessmen outside of their display case. And yet, because of Robinson's generous reading of my letter, that is exactly what happened. My request made its way to curator George Dalgleish, who asked which ones I wanted to see. He passed that information on to curator Jackie Moran, who cheerfully wrote to tell me that "I will get the chessmen off display at 08:00, as long as I can get the gallery lights switched on."

By 08:30 I was set up in Jackie's office at the NMS, with my computer, my notes, my camera, a borrowed magnifying glass, and the four chessmen I had chosen in a padded carrying case on the table in front of me. Jackie spread tissue on the tabletop and handed me a set of bright purple latex gloves, then returned to her own work at the desk behind me, leaving me face to face with these exquisite little 800-year-old works of art: a warder-rook, biting his shield like a Viking berserk; a bishop, raising his hand in blessing; and a king and queen pair.

The most interesting to me was the queen, whom I had thought at first had been broken and repaired. Now I could tell, studying her up close, that the patch had been applied (with four tiny ivory pegs) before the artist had finished her carving, in order to cover over a weak spot in the original walrus tusk. The workmanship was so fine and the materials so poor, compared to the other pieces, that I really had to wonder what was going through the artist's mind to have even tried to make a chess piece out of this defective lump of tusk.

Seated on her richly decorated throne, she has terrible posture. Her spine is hunched, her head juts forward; she looks old and almost all done in. Her hair is braided and looped up under a veil that is clipped in back. She wears a pleated skirt, a short gown, a robe with embroidered or fur-trimmed edges, a jewel at her throat, her wrists ringed with bangles. She is brooding, her jaw clenched. She claps her right hand to her cheek, cradles her elbow with the left.

Such love went into the making of that queen, I thought, marveling over her tiny fingers. Her left thumb curves back like mine does.

I was concentrating so hard on this little queen in my hand, turning her to take photos from all angles, that at one point my camera slipped out of my grasp. Thunk. I heard Jackie gasp. "It was the camera," I mumbled, and kept on with my work.

It wasn't until the next day, as I was having tea with former NMS curator David Caldwell in the museum cafe, that I realized how shocked Jackie must have been to have heard that thunk—and how completely the beauty of these pieces had made me forget everything but the desire to understand them. Said David, “If you knew what they were valued at, you wouldn’t want to pick one up.”

Read more about Ivory Vikings on my website, http://nancymariebrown.com, or check out these reviews:

Read more about Ivory Vikings on my website, http://nancymariebrown.com, or check out these reviews:"Bones of Contention," The Economist (August 29): http://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21662487-bones-contention

"Review: Ivory Vikings," Minneapolis Star Tribune (August 29): http://www.startribune.com/review-ivory-vikings-by-nancy-marie-brown-the-mystery-of-the-lewis-chessmen/323230441/

Published on September 09, 2015 05:00

September 1, 2015

Ivory Vikings Published Today!

Today is the official publication day of Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them.

Today is the official publication day of Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them.As a writer I live for such days, when the book that's been my world and work for the past three years finally meets you, the readers.

And the first reviews have reassured me that you're going to love it:

"Absorbing ... bristles with fascinating facts," said The Economist.

"A fascinating tale of discovery and mystery," said the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

"This book is a delight," said Booklist: "endlessly fascinating."

The New York Post included it in "This Week's Must-Read Books."

And on Amazon.com it's listed in "Best Books of the Month."

That's in addition to the wonderful blurbs it received from advance readers like Pulitzer-prize winner Geraldine Brooks, who said, "Brown's book is a true cornucopia, bursting with delicious revelations. Whether your passion is chess, art, archaeology, literature, or the uncanny and beautiful landscape of Iceland, Ivory Vikings offers rich and original insights by a writer who is as erudite as she is engaging."

To whet your appetite, here is the opening passage:

To whet your appetite, here is the opening passage:In the early 1800s, on a golden Hebridean beach, the sea exposed an ancient treasure cache: ninety-two game pieces carved of ivory and the buckle of the bag that once contained them. Seventy-eight are chessmen--the Lewis chessmen--the most famous chessmen in the world. Between one and five-eighths and four inches tall, these chessmen are Norse netsuke, each face individual, each full of quirks: the kings stout and stoic, the queens grieving or aghast, the bishops moon-faced and mild. The knights are doughty, if a bit ludicrous on their cute ponies. The rooks are not castles but warriors, some going berserk, biting their shield in battle frenzy. Only the pawns are lumps--simple octagons--and few at that, only nineteen, though the fourteen plain disks could be pawns or men for a different game, like checkers. Altogether, the hoard held almost four full chess sets--only one knight, four rooks, and forty-four pawns are missing--about three pounds of ivory treasure.

Who carved them? Where? How did they arrive in that sandbank or, as another account says, that underground cist--on the Isle of Lewis in westernmost Scotland? No one knows for sure: History, too, has many pieces missing. To play the game, we fill the empty squares with pieces of our own imagination.

Instead of facts about these chessmen, we have clues. Some come from medieval sagas; others from modern archaeology, art history, forensics, and the history of board games. The story of the Lewis chessmen encompasses the whole history of the Vikings in the North Atlantic, from 793 to 1066, when the sea road connected places we think of as far apart and culturally distinct: Norway and Scotland, Ireland and Iceland, the Orkney Islands and Greenland, the Hebrides and Newfoundland. Their story questions the economics behind the Viking voyages to the West, explores the Viking impact on Scotland, and shows how the whole North Atlantic was dominated by Norway for almost five hundred years, until the Scottish king finally claimed his islands in 1266. It reveals the struggle within Viking culture to accommodate Christianity, the ways in which Rome's rules were flouted, and how orthodoxy eventually prevailed. And finally, the story of the Lewis chessmen brings from the shadows an extraordinarily talented woman artist of the twelfth century: Margret the Adroit of Iceland.

The Lewis chessmen are the best-known Scottish archaeological treasure of all time. To David Caldwell, former curator at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, where eleven of the chessmen now reside, they may also be the most valuable: "It is difficult to translate that worth into money," he and Mark Hall wrote in a museum guidebook in 2010, "and practically impossible to measure their cultural significance and the enjoyment they have given countless museum visitors over the years." Or, as Caldwell phrased it to me over tea one afternoon in the museum's cafeteria: "If you knew what they were valued at, you wouldn't want to pick one up."

Too late for that. I'd already spent an hour handling four of them. Out of their glass display case, they are impossible to resist, warm and bright, seeming not old at all, but strangely alive. They nestle in the palm, smooth and weighty, ready to play. Set on a desktop, in lieu of the thirty-two-inch-square chessboard they'd require, they make a satisfying click.

I hope you'll join me at one of these events introducing Ivory Vikings. As more dates are scheduled, I'll add them to the Events page on my website at http://nancymariebrown.com.

I hope you'll join me at one of these events introducing Ivory Vikings. As more dates are scheduled, I'll add them to the Events page on my website at http://nancymariebrown.com.September 9, 2015: Norwich Bookstore, Norwich, VT at 7:00 p.m.

September 11, 2015: Book Launch Party at 7:00 p.m. For an invitation, contact Kim at Green Mountain Books and Prints in Lyndonville, VT.

September 19, 2015: Northshire Bookstore, Manchester Center, VT at 7:00 p.m.

September 21, 2015: Scandinavia House, 58 Park Avenue, New York at 6:30 p.m.

October 15, 2015: The Fiske Icelandic Collection at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY at 4:30 p.m.

October 17, 2015: The Sixth Annual Iceland Affair, Winchester Center, CT; time to be announced.

November 1, 2015: Vermont Voices at Stone Church, Chester, VT at 2 p.m., hosted by Misty Valley Books.

Published on September 01, 2015 07:00

August 25, 2015

Did Tolkien Ever Go to Iceland?

No, Tolkien never went to Iceland. Elsewhere on this blog (see "The Tolkien Connection"), I've talked about how much Tolkien was inspired by Iceland and Icelandic literature--and how his love of Iceland inspired me.

No, Tolkien never went to Iceland. Elsewhere on this blog (see "The Tolkien Connection"), I've talked about how much Tolkien was inspired by Iceland and Icelandic literature--and how his love of Iceland inspired me.Tolkien's trolls are Icelandic trolls. His hobbit holes are like Icelandic turf houses. Bilbo's ride to Rivendell matches, more or less, a ride through the Icelandic landscape. Gandalf's character comes from Icelandic tales of Odin. Hobbits, too, may have Icelandic antecedants. But Tolkien never went to Iceland.

I've always thought that was sad. It was Tolkien who, in a roundabout way, sent me to Iceland the first time, and I've been back about 20 times since. Iceland has inspired five of my seven books.

But a recent conversation on the listserv of the Mythopoeic Society made me think of Tolkien's travel gap in a different way. Wrote David Bratman, a librarian and Tolkien scholar, "Tolkien, and the Inklings in general, tended to consider merely visiting places to be over-rated as a way of getting to know them."

Bratman refers to a letter Tolkien wrote to his son Christopher in 1943, in which he complains about what some people might call progress: "The bigger things get the smaller and duller or flatter the globe gets. It is getting to be all one blasted little provincial suburb. ... At any rate it ought to cut down on travel. There will be nowhere to go. So people will (I opine) go all the faster."

Instead of travelers, Bratman explains, Tolkien and his friends were "bookmen, who learned of places through deep immersion in the literature of a place, and not just in reports by other visitors. Tolkien's thorough knowledge of Icelandic civilization came from his intensive and lifelong reading of Old Norse literature."

For Tolkien, that approach obviously worked. For me--not so much.

For one thing, I write history and historical fiction, not fantasy. What places actually look like matters to me. When I wrote Song of the Vikings , for example, I spent several weeks tromping around in the area Snorri Sturluson ruled in the 13th century. Suddenly I understood why his father, in Sturlunga Saga, got involved in a feud over the ownership of the seemingly inconsequential farm of Deildartunga.

Nowhere in the saga does it explain that Deildartunga owned the highest-volume hotspring in the world. Because of this feud, Snorri was fostered by Jon Loftsson and educated at Oddi, where he learned to write. This hotspring, you could say, led directly to the writing of Heimskringla: The History of the Kings of Norway and The Prose Edda, containing nearly all that we know of Norse mythology, and perhaps even Egil's Saga, which influenced the writing of so many other sagas.

Such on-the-ground research in Iceland and Greenland also helped me write The Far Traveler and my young adult novel based on it, The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler . I spent months living where Gudrid lived, walking where Gudrid walked, taking a boat down the fjord Gudrid sailed or a horse into the mountains where Gudrid rode.

True, things have changed since she lived there around the year 1000. I took full advantage of electric lights, geothermal heat, jeeps, power boats, hi-tech hiking clothes, you name it. But some things hadn't changed: the wind on my face, the stinging rain, the way the sun sank behind the mountains, the cries of the birds, the smell of the seaweed or the hay, the spirited horses, how difficult it was to walk through a lumpy, bumpy, frost-heaved pasture without twisting an ankle, the way the tide surged in over the sea flats.

Armchair travel is one of my favorite pastimes. All winter I travel through books--and it's the only way I know to travel back in time. But come summer, my wanderlust isn't so easily contained and you can find me--for at least part of the time--in Iceland. After 20 visits in nearly 30 years, I'm just getting to know the place.

Published on August 25, 2015 17:00

August 5, 2015

Iceland's Deserts

"There's a difference between a natural desert and a manmade desert," Magnus said as we crossed an imaginary line in the sand on our way to the hot spring area Landmannalaugar.

"There's a difference between a natural desert and a manmade desert," Magnus said as we crossed an imaginary line in the sand on our way to the hot spring area Landmannalaugar.I've long loved Iceland for its contrasts. Not just the clash of ice and fire that everyone remarks upon, but the juxtaposition of jewel-green fields and jagged black lava, of fertile horse pastures and sand-blasted wastelands. But after a day spent with Magnús Jóhannsson, the botanist who runs Mudshark Adventure Tours [see www.mudshark.is] out of Hella, in Iceland's south, I realized my perception of Iceland's beauty was rather romantic--and more than a little bit skewed.

I've known Magnús and his wife, Anna María Ágústsdóttir, since before they earned their Ph.D.s at Penn State some years ago. I've visited them several times in Iceland and heard about their work at Landgræslan ríkisins, Iceland's soil conservation service.

Apparently, I wasn't paying attention.

Twice in the 1990s, while they were still in school, I rode on horseback from a farm near Hella around the volcano Hekla to the hotspring area at Landmannalaugar. Once we had six days of driving rain (read about that trip here: 2/29/12). The second trip I got badly sunburned and rode like Jesse James with a bandanna tied around my nose and mouth to filter out the suffocating dust.

I'd always assumed the deserts of blowing black sand I'd ridden across were inescapable--a constantly fought, constantly to-be-reckoned-with natural hazard of this volcanically active land. They're not. In many places, Magnus pointed out, as we drove a similar route to Landmannalaugar in the Mudshark Land Rover, these deserts are manmade. They are both preventable and capable of being restored to a healthy green.

True, volcanic eruptions do periodically blanket some areas in ash. But the ash doesn't necessarily kill off the vegetation, I learned from reading a scientific paper Anna María recently published in the journal Natural Hazards [get link]. Only if the area is already under stress--from overgrazing, usually--is the ashfall catastrophic. A healthy ecosystem can bounce back.

Our tour began in the town of Hella, where one of Magnús and Anna María's neighbors keeps a garden of apple trees (a curiosity in Iceland). We passed the headquarters of the soil conservation service on a road bordered by tall imported trees. Fields of barley and rapeseed rippled in the wind (quite uncommon in Iceland, where the only reliable crop for generations has been hay). A demonstration forest hugged a small hill.

When we entered the desert I had ridden through in the 1990s, I was surprised to see islands of native birch had established themselves. In other places, the soil conservation service had seeded acres of black sand with Alaskan lupine, a nitrogen-fixing legume, to enrich the soil, and with native lyme grass, to stabilize the dunes.

We passed a waterfall I knew well from my rides, Troll Woman's Leap. I had a picture on my office wall back home of our horse herd resting at that very spot: Black sand spread from the riverbanks in every direction, our many-colored herd looking bright in contrast. Now the place was transformed with grass and flowers.

Then we crossed through a gate in a fence, and the vegetation disappeared. The black sand deserts I'd ridden through reappeared. We'd left the soil conservation area, and entered a section of the highlands where sheep were allowed to graze. We saw a ewe and two lambs here and there. Nothing you could call a "flock," just the rare family of animals. Yet it was enough to suppress regrowth. These were the manmade deserts Magnús had referred to.

At some point (was there a gate? I don't recall) we transitioned smoothly into the natural desert: We had reached the highlands, where snow and cold defeat all but the alpine flowers (blooming in lush profusion in sheltered spots) and the hardy moss, which did its best to soften the jagged lumps of lava.

Like the many tourists we met at Landmannalaugar, we marveled at the vast range of color in the rocks, at the astonishing sulfur vents reeking of rotten egg, at the steam rising from the river, and at the stark beauty of the bleak, lake-filled landscape in Iceland's harsh interior.

When the first settlers came to Iceland in the ninth century, scientists have determined, birch woodlands covered 25% of the island. The settlers cut the trees to make charcoal. They burned the scrubby forests to clear land for planting. They introduced grazing animals--horses, cows, sheep, goats, and pigs--which kept the forests from regenerating. The winds ate at the edges of the overgrazed fields, and the volcanoes did their part, periodically coating the landscape with ash. Over centuries, the stresses accumulated: cutting, burning, grazing, wind erosion, ash fall...

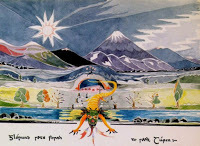

The story of Iceland's desertification is well told at the soil conservation service's new museum, Safnagardur [website], just east of Hella, where these two photos were taken. The bottom one shows a surprisingly large piece of petrified wood found in Iceland.

The museum tells, too, the new story of re-greening the land. Now Iceland's forested area is a little over 1% of the country--and growing steadily.

Anyone like me who is enthralled by Iceland's beauty, and who wonders why it looks the way it does, should spend an instructive hour at Safnagardur. Better yet, take Magnús's Mudshark Ecosystems tour [see http://www.mudshark.is/ecosystems-and-restoration.html] or, like I did, his Landmannalaugar tour [http://www.mudshark.is/Super-jeep-private-tours-Landmannalaugar.html]

Published on August 05, 2015 12:39

July 15, 2015

Iceland Rocks

As I was preparing for my 20th trip to Iceland--where I am now--this map of the country surfaced on my Facebook feed.

As I was preparing for my 20th trip to Iceland--where I am now--this map of the country surfaced on my Facebook feed."On my trips around Iceland over the last years, I ... have collected one rock at each location where I've caught a photo I've been really pleased with," wrote Snorri Þór Tryggvason of Iceland Aurora Films. "So I decided to make a map of Iceland out of those rocks, since I finally have enough." Each rock, he explained, "is placed at approximately the location where I found it."

The post was dated December 2014--apparently Snorri Þór, like I do, muses about his summer expeditions in Iceland's hinterland during the long dark winter days, and likes to pick up and play with the rocks he's pocketed on his journeys.

I admire him for having the self-discipline to pick up one rock--and only one rock--from each special place.

When my husband, son, and I spent three months at Litla Hraun, an abandoned farmhouse on the west coast of Iceland in 1996, cut off from civilization (road, neighbors, electricity, plumbing, phone) twice a day by the tides, we collected three bulky bags of beach rocks. Though transporting them home required carrying them in our backpacks the 45-minute walk across the tidal sands, they all made it to Pennsylvania--and then, some years later, to our new home in Vermont. One bag is secreted in my son's steamer trunk. The other two--and miscellaneous fellows--fill the glass bases of table lamps.

When my husband, son, and I spent three months at Litla Hraun, an abandoned farmhouse on the west coast of Iceland in 1996, cut off from civilization (road, neighbors, electricity, plumbing, phone) twice a day by the tides, we collected three bulky bags of beach rocks. Though transporting them home required carrying them in our backpacks the 45-minute walk across the tidal sands, they all made it to Pennsylvania--and then, some years later, to our new home in Vermont. One bag is secreted in my son's steamer trunk. The other two--and miscellaneous fellows--fill the glass bases of table lamps.Most of my Icelandic rocks are ordinary lava: black, perforated, shiny or dull, water-rounded or craggy. But I have a few sparkly ones, like Snorri: reds and greens and crystals. I'm especially fond of the quartz I've collected at the farm of Helgafell, a spot I've written about before as my "thin place," where the world and the otherworld meet. From one cliff-face beside the fjord, crystals like teeth and eyes and icy blue fingers spill out of the rock.

Then there was Bright Stone Beach. On that same summer of 1996, my family found a halfmoon of sand littered with little polished rocks. None was bigger than a finger nail. As the tide crept in, they disappeared--never to be seen again, though I have hiked that same stretch of beach numerous times since, searching for them. If not for the pewter saucer I filled with those gems, I wouldn't believe that beach was real.

Then there was Bright Stone Beach. On that same summer of 1996, my family found a halfmoon of sand littered with little polished rocks. None was bigger than a finger nail. As the tide crept in, they disappeared--never to be seen again, though I have hiked that same stretch of beach numerous times since, searching for them. If not for the pewter saucer I filled with those gems, I wouldn't believe that beach was real.But that was years ago. In spite of my love for my lapidary souvenirs, my rock collecting days in Iceland are done.

They came to a crash one weekend in 2001, when I hiked at Skaftafell National Park with a friend who's a geochemist. I pocketed a rock. She frowned at me. It's illegal to take rocks, she said. I laughed. It was a pebble. Who would miss a pebble? It's against the law, she repeated, and glared. Iceland has a million tourists a year. What if everyone took home a pocketful of pretty rocks?

I kept the pebble. I was stubborn in those days. (Still am.) But after that day, every time I slipped an Icelandic rock into my pocket, I saw Anna Maria's glare.

Like a shoplifter, I stole three black river-rounded stones from a glacial stream in the highlands the year I rode a horse on the Kjolur trail 125 miles north to south through the center of the island. (But Anna, I may never see that river again!)

Like a shoplifter, I stole three black river-rounded stones from a glacial stream in the highlands the year I rode a horse on the Kjolur trail 125 miles north to south through the center of the island. (But Anna, I may never see that river again!)Like a thief, I picked up three sandy lozenges (red, green, and tan) from a beach in the West Fjords that same summer.

And I could not pass up that last beautiful geode I found by the fjord at Helgafell, a tiny half-globe stuffed with glittering teeth.

But I'm making amends. Truly. The last few times I traveled to Iceland, I took with me a quart-sized bag full of Icelandic rocks, culled from my collections. My husband looked at me like I was nuts when I told him I was repatriating them. I stuffed them in my day pack when I took a hike and scattered them.

All except one. That one I kept in my coat pocket to fill my hand whenever I was tempted to pick up another rock.

Published on July 15, 2015 07:00

June 16, 2015

Iceland's Independence Day

Today, June 17, Icelanders celebrate their independence day, on the birthday of Jon Sigurdsson, the leader of the nineteenth-century Icelandic independence movement. Jon was a saga scholar, before he became a politician. He worked briefly at the library in Copenhagen established by the great collector of medieval Icelandic manuscripts, Arni Magnusson.

Today, June 17, Icelanders celebrate their independence day, on the birthday of Jon Sigurdsson, the leader of the nineteenth-century Icelandic independence movement. Jon was a saga scholar, before he became a politician. He worked briefly at the library in Copenhagen established by the great collector of medieval Icelandic manuscripts, Arni Magnusson.So it's fitting that, on this day of Icelandic independence, we remember the role of the sagas in setting Icelanders free.

Reading the Icelandic sagas, you learn of Iceland's early days as a free state, from its founding in 874.

Reading the sagas, you learn how Iceland lost its independence in 1262 and became subject to Norway, which itself was later taken over by Denmark.

And reading the sagas--simply the act of reading and rereading them--is what united the nineteenth-century Icelanders, as I learned while researching Song of the Vikings , my biography of the saga master Snorri Sturluson.

Here's how I explained the connection between Icelandic sagas and Icelandic independence in

Song of the Vikings

:

Here's how I explained the connection between Icelandic sagas and Icelandic independence in

Song of the Vikings

:In 1835 four Icelandic students founded a political magazine in Copenhagen. They printed their manifesto in the form of a poem, which "was exactly what was needed in order to unite the Icelandic people," says Karlsson in The History of Iceland (published in 2000 by the University of Minnesota Press).

The only one of their ancestors it evokes is Snorri:

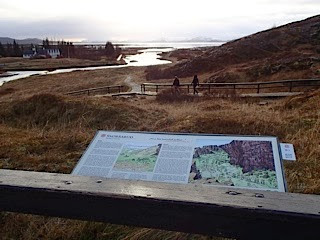

"... Ah! but up on the lava where the Axe River plummets forever

into the Almanna Gorge, Althing is vanished and gone.

Snorri's old site is a sheep-pen; the Law Rock is hidden in heather,

blue with the berries that make boys--and the ravens--a feast.

Oh you children of Iceland, old and young men together!

See how your forefathers' fame faltered--and died from the earth!"

Four lines of this poem by Jonas Hallgrimsson (translated here by Dick Ringler) are engraved on a plaque now standing on the site of Snorri's booth in Thingvellir, the great rift valley in the south of Iceland where the Althing, the yearly parliament of chieftains, met during the Saga Age.

The Althing reconvened as a national parliament, with Danish permission, in 1845. In 1874 Iceland received a new constitution and, in 1904, home rule. One of its first demands was that Denmark return the manuscripts of the sagas that had been collected--mostly by the scholar Arni Magnusson--and brought to the royal library and that of the University of Copenhagen in the early 1700s. The Danes declined.

In 1918 Iceland became a sovereign state in a "personal union" with the Danish king--much like the situation in 1262, when the chieftains swore oaths of loyalty to King Hakon the Old. For its coat-of-arms the new nation turned once again to Snorri.

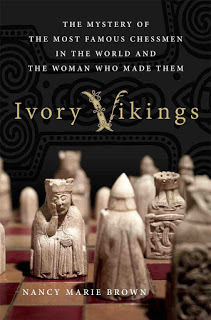

King Harald, Snorri wrote in Heimskringla, was angry at the Icelanders, who had composed lampoons about him. He ordered a "troll-wise man" to spy out the country's defenses. Disguised as a whale, the wizard swam close to Iceland’s eastern shore: "Then came a great dragon down from the dale" and "blew poison at him." He swam along the north coast, "but there came against him a bird so big that its wings neared the fells on both sides of it." The wizard-whale fled to the west: "Toward him came a great ox that waded out in the sea and began to bellow horribly." Swinging wide, he swam south, "but against him there came a great hill giant who had an iron staff in his hand and bore his head higher than the fells." King Harald was dissuaded from attacking. Iceland's coat-of-arms bears a dragon, an eagle, an ox, and a giant.

King Harald, Snorri wrote in Heimskringla, was angry at the Icelanders, who had composed lampoons about him. He ordered a "troll-wise man" to spy out the country's defenses. Disguised as a whale, the wizard swam close to Iceland’s eastern shore: "Then came a great dragon down from the dale" and "blew poison at him." He swam along the north coast, "but there came against him a bird so big that its wings neared the fells on both sides of it." The wizard-whale fled to the west: "Toward him came a great ox that waded out in the sea and began to bellow horribly." Swinging wide, he swam south, "but against him there came a great hill giant who had an iron staff in his hand and bore his head higher than the fells." King Harald was dissuaded from attacking. Iceland's coat-of-arms bears a dragon, an eagle, an ox, and a giant. The Icelanders repeated their demands to "bring the manuscripts home." The Althing passed resolutions in 1930 and 1938, then their literary quest was interupted by World War II. In April 1940 Denmark was invaded by Germany; a month later Iceland was occupied by the British, one result being Iceland’s final break with Denmark. The independent Republic of Iceland was established at Thingvellir in 1944; in 1947 the Althing resolved, once again, to "bring the manuscripts home."

The Icelanders repeated their demands to "bring the manuscripts home." The Althing passed resolutions in 1930 and 1938, then their literary quest was interupted by World War II. In April 1940 Denmark was invaded by Germany; a month later Iceland was occupied by the British, one result being Iceland’s final break with Denmark. The independent Republic of Iceland was established at Thingvellir in 1944; in 1947 the Althing resolved, once again, to "bring the manuscripts home."This time, Denmark formed a committee. In 1961 a list of manuscripts was drawn up, and Iceland agreed to give Denmark twenty-five years to deliver them. Ten years later—after being photographed and conserved—the first set steamed into Reykjavik harbor aboard a Danish coastguard cutter. Thousands of Icelanders stood by the docks. Thousands more watched via the first live outdoor broadcast of the state television station. Eventually 1,666 manuscripts and over 7,000 charters (1,350 of them originals, the rest copies) were returned from Arni Magnusson’s collection—slightly over half of it. Another 141 manuscripts were sent home from the Royal Library. The last arrived in Iceland in 1997.

"People still say: 'We want to see the manuscripts,'" wrote Gisli Sigurdsson and Vesteinn Olason in The Manuscripts of Iceland in 2004. The manuscripts "are at one and the same time the repository of medieval Icelandic culture and its visible symbol." They are Iceland's "main source of pride."

If you are in Iceland, a fitting way to celebrate June 17 would be to visit the Settlement Sagas exhibition of the Reykjavik City Museum.

Published on June 16, 2015 14:23

June 3, 2015

An Old Story, A New Saga

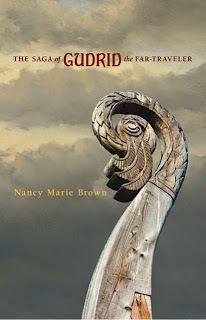

Monday was the official publication date of my young adult novel

The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler

. It's been a long time coming.

Monday was the official publication date of my young adult novel

The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler

. It's been a long time coming.I can still remember where I was when I read my first Icelandic saga. It was Njal's Saga, in translation, and I was at my aunt's house for Thanksgiving during my second year in college in 1978. I was sitting on the staircase, hiding from my family so that I could continue reading this book that had enthralled me. I went on to learn Old Norse and I started visiting Iceland at least every other year beginning in 1986.

For 20 years, however, I made my living as a science writer for a magazine published by Penn State University. I used to say I led a double life-science by day, sagas by night. One day in 2002 I was sitting at my desk at the university when a professor called. He was among a team of archaeologists who had discovered a Viking Age longhouse on a farm in northern Iceland.

I asked, "Which farm?"

"Glaumbaer," he said.

I was probably the only science writer in America who would reply, "You mean the farm of Gudrid the Far-Traveler?"

That was the genesis of my first book about Gudrid, a nonfiction book called The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman, published in 2007. (You can read the article I wrote about the Penn State professor's work here.)

I had been looking for a way to combine science and sagas for a long time, and initially I thought I was writing a book about new techniques in archaeology using the story of Gudrid as an example. A few years into the project, my editor at Harcourt suggested I turn my idea inside out and write a book about Gudrid using archaeology as one source.

I had been looking for a way to combine science and sagas for a long time, and initially I thought I was writing a book about new techniques in archaeology using the story of Gudrid as an example. A few years into the project, my editor at Harcourt suggested I turn my idea inside out and write a book about Gudrid using archaeology as one source.To do so, I had to study in depth the two sagas that mention Gudrid, The Saga of the Greenlanders and The Saga of Eirik the Red, collectively known as the Vinland Sagas. These two sagas had never been my favorites.

Once I mentored a Penn State student for an independent study project on the sagas. He compared Gudrid to the women in several other sagas, and wrote: "Gudrid has one great shortcoming-she's rather bland. ... Many of the other sagas tell us enough about the characters that you get a good feel of how people lived their lives-and they are often interesting lives. Gudrid has none of these particularly intimate displays of her dealings with others-it's just assumed that she's smart and well-behaved. Being smart and well-behaved probably spells out being boring."

The more I studied the Vinland Sagas, however, the more I realized that Gudrid wasn't bland or boring--and probably not even well-behaved. These two sagas were simply written in such a way that Gudrid's story was hidden. That intrigued me.

One of the more frustrating things about these two sagas is that they contradict each other. In one saga she has two husbands, in the other she has three. In one saga she is rich when she arrives in Greenland, in the other she is poor. It was impossible, when writing nonfiction, to create a coherent narrative about her.

Also frustrating are the hints. According to one saga, Gudrid "knew how to get along with strangers." Later, that saga shows Gudrid in the New World, failing to communicate with a native woman. The implication is clear: If she couldn't get along with these strangers, no one could. Perhaps Gudrid decided the Vikings should abandon their colony.

Perhaps the Vinland expedition itself was her idea. She packed up and set sail there twice-with two different husbands. Although the sagas disagree on the particulars, her hand in the preparations each time is clear.

Writing nonfiction, I could only say "perhaps, perhaps." When The Far Traveler came out in 2007, I was very happy with it, but I didn't think it was finished. I immediately began thinking about writing a novel so I could bring Gudrid's story to life or, as one of my writer friends put it, "make it real."

Researching and writing my nonfiction book The Far Traveler took me, off and on, five years. Writing The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler, my just-published historical novel, took me another eight years--even though all of my research was essentially done.

The biggest problem for me was genre: Who was I writing for?

In 2009 I began reading young adult novels--probably because my best friend, Linda Wooster, became the librarian at a local high school and started recommending books for me to read. One that I liked very much was Hush by Donna Jo Napoli, which told the story of the character Melkorka from the Laxdaela Saga. Reading it convinced me that the best audience for Gudrid's story were readers Gudrid's own age when she went exploring: between 14 and 21.

In 2009 I began reading young adult novels--probably because my best friend, Linda Wooster, became the librarian at a local high school and started recommending books for me to read. One that I liked very much was Hush by Donna Jo Napoli, which told the story of the character Melkorka from the Laxdaela Saga. Reading it convinced me that the best audience for Gudrid's story were readers Gudrid's own age when she went exploring: between 14 and 21.So I decided to learn how to write young adult fiction. One day I was talking to Andy Boyles, the science editor at Highlights for Children, who had bought a few of my nonfiction pieces, and he told me about a writer's conference at which Donna Jo would be a mentor. With the help of a scholarship from the Highlights Foundation and a Career Grant from the National Association of Science Writers, I signed up. I had three sessions with Donna Jo in which she helped me to structure the novel. She also gave me an invaluable gift: a deadline. If I finished a draft of the novel by a certain date, she would read it; if she liked it, she would send it to her agent.

I met Donna Jo's deadline. She liked the novel, but her agent did not. So the next year, I signed up for another workshop through the Highlights Foundation, this one with the editor who eventually published the novel, Stephen Roxburgh of Namelos. For one intense week, Stephen went over with me everything I needed to improve to make the novel publishable, and over the next year he checked in with me about once a month to see if I was making progress. He even came to my house for a visit.

Without these wonderful mentors The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler would still be in my closet where, I'm afraid, lie several other unfinished novel manuscripts. While making Gudrid's story come to life has been very satisfying, I find it is much easier to write nonfiction and simply say "perhaps."

The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler has been chosen as the 2015 INL Reads! selection of the Icelandic National League. Thanks to Rob Olason of the Icelandic National League, whose questions prompted these recollections.

Published on June 03, 2015 07:19

May 27, 2015

A Viking Fairy Tale

A reader of Song of the Vikings, my biography of the 13th-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, wrote:

A reader of Song of the Vikings, my biography of the 13th-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, wrote:"I am doing a research project for school about Norse mythology and am wondering, are their any classic fairytales ("Beauty and the Beast," "Sleeping Beauty," etc.) or fairytale characters (werewolves, etc.) that correspond to any particular Norse myths, or have a similar storyline or characteristics?"

My response:

There are, indeed, a lot of fairytale motifs in the Icelandic sagas. If you look in Snorri's Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway, especially the first saga (Ynglinga saga), you'll find dwarfs, trolls, talking birds, and Odin's shapeshifting and other wizardly skills. There are werewolves in Volsunga Saga and in Snorri's Edda, as well as a hint of one in Egil's Saga.

A wonderful fairytale that Snorri tells himself is this "sleeping beauty"-like one from "The Saga of King Harald Fair-Hair" in Heimskringla. Here it is in the 1932 translation by Erling Monsen:

King Harald went one winter a-feasting in the Uplands and had a Yule feast made ready for himself in Toftar. On the eve of Yule, Svasi came without the door whilst the king was at the table and he sent a messenger to the king to go out to him. But the king was wroth at that behest and the same man who brought in the behest bore out the king’s anger, but notwithstanding, Svasi bade him carry the same message a second time; he said he was the Finn whom the king had allowed to set his hut on the other side of the stream there. The king then went out and agreed to go home with him and crossed the stream, egged on my some of his men but discouraged by others. There Snaefrid, Svasi’s daughter, stood up, the most beautiful of women, and she offered the king a cup full of mead; he drank it all and also took her hand, and straightway it was as though fire passed through his body, and at once he would lie with her that same night. But Svasi said that it should not be so except by force, unless the king betrothed Snaefrid and wed her according to the law. The king took Snaefrid and wed her, and he loved her so witlessly that he neglected his kingdom and all that was seemly for his kingly honour. They got four sons, Sigurd the Giant, Halvdan Highleg, Gudrod Gleam, and Ragnvald Rettlebone. Afterwards Snaefrid died, but the colour of her skin never faded and she was as rosy as before when she lived. The king always sat over her and thought that she would come to life again, and thus it went on for three winters that he sorrowed over her death and all the people of his land sorrowed over his delusion. And to stop this delusion, Torleiv the Wise came to his help; he did it with prudence, in that he spoke to him first with soft words, saying, “Is it not strange, O king, that thou shouldst remember so bright and noble a woman and honour her with down and goodly web [cloth] as she bade thee. But thy honour and hers is still less than it seems, in that she has lain for a long while in the same clothes, and it is fitter that she should be raised and the clothes changed under her.” But as soon as she was raised from the bed, so there rose from the body a rotten and loathesome smell and all kinds of evil stink; speedily a funeral bale was then made and she was burned. But before that all the body waxed blue and out crawled worms and adders, frogs ,and paddocks and all manner of foul reptiles. So she sank into ashes, and the king came to his wits and cast his folly from his heart and afterwards ruled the kingdom and was strengthened and gladdened by his men, and they by him, and the kingdom by both.

I recently came across a paper that uses this fairytale to explore how Snorri Sturluson worked as a writer--a topic that I discuss at some length in Song of the Vikings. By examining his Edda, looking at the sources he used and the reasons he had for writing, I conclude there that Snorri invented much of what we think of as "Norse mythology."

I recently came across a paper that uses this fairytale to explore how Snorri Sturluson worked as a writer--a topic that I discuss at some length in Song of the Vikings. By examining his Edda, looking at the sources he used and the reasons he had for writing, I conclude there that Snorri invented much of what we think of as "Norse mythology."Now scholar Takahiro Narikawa has convinced me that Snorri also invented--or at least put his own spin on--Norwegian history when it suited him. Narikawa's paper, which I stumbled upon courtesy of the website Medievalists.net, appeared in 2011 in the journal Balto-Scandia and is available here:

http://www.medievalists.net/2013/01/27/marriage-between-king-harald-fairhair-and-snaefridr-and-their-offspring-mythological-foundation-of-the-norwegian-medieval-dynasty/

Why did Snorri include this fairytale in his history of the kings of Norway? Scholars have generally thought of it as an origin myth. It explains the founding of the kingdom of Norway by Harald Fair-Hair, in about 860, in one of two ways. Either Snaefrid is a nature goddess, whom King Harald has to symbolically possess, or she represents the reindeer-herding, fur-harvesting Sami (called the "Finns" in the sagas) of the far north. In order to unify Norway, King Harald has to bring together its two halves--human/divine, Norse/Sami, south/north--and, indeed, future kings of Norway do descend from Harald and Snaefrid's son, Sigurd.

But Narikawa's paper pokes a hole in this theory that Snorri was simply relating a colorful origin myth. It points out that Snorri is the only one to say Sigurd--called "the Giant," by Monsen, though his nickname is usually translated as "the Bastard"--is a son of Snaefrid.

But Narikawa's paper pokes a hole in this theory that Snorri was simply relating a colorful origin myth. It points out that Snorri is the only one to say Sigurd--called "the Giant," by Monsen, though his nickname is usually translated as "the Bastard"--is a son of Snaefrid.The sleeping beauty tale itself appears in Snorri's source, the anonymous Ágrip af Nóreg's konungasögum (or Synoptic History of the Kings of Norway), nearly word for word. Only three sentences differ--including the one that names Snaefrid's four sons. In Ágrip, there's only one son, Ragnvald, a notorious sorceror.

Sigurd is well known in Norwegian history. Other sources, for example, trace the genealogy of King Harald Hard-Rule (who reigned from 1047-1066) back to Sigurd, the son of Harald Fair-Hair.

Why does Snorri--and only Snorri--connect Sigurd with the mysterious and bewitching Snaefrid?

Narikawa suggests it has to do with the civil wars in Norway, nearly continuous from 1130 to 1240. Snorri presents Harald's infatuation with Snaefrid as cursed, Narikawa says. Snorri insinuates "that such foul elements as a talent for sorcery in the royal blood were caused by Harald's marriage to her" and that these foul elements explained the fighting: "The ancestor of the medieval Norwegian dynasty, Sigurd the Bastard, himself was also half-Finn and not immune to this curse. The discord and murder among members of the royal family were to be inherent in the Fairhair Dynasty," Narikawa writes.

Because of this curse, Snorri argued that a true king of Norway needed to be descended, not only from Harald Fair-Hair, but also from a second king, Harald Gilli (1130-36). During Norway's civil wars, all the pretenders who represented the "Birkibein" (Birch-Leg) party in Norway were descended from King Harald Gilli. Most of their opponents were not.

In particular, the kings and earls for whom Snorri wrote praise poems--King Sverrir, King Ingi, Jarl Hakon, Jarl Skuli, and King Hakon IV--all belonged to the Birkibein faction. "Snorri seemed to be politically attached to this faction since his adolescence," Narikawa says, and, when writing Heimskringla, he shaped his history of the kings of Norway to enhance their legitimacy.

In particular, the kings and earls for whom Snorri wrote praise poems--King Sverrir, King Ingi, Jarl Hakon, Jarl Skuli, and King Hakon IV--all belonged to the Birkibein faction. "Snorri seemed to be politically attached to this faction since his adolescence," Narikawa says, and, when writing Heimskringla, he shaped his history of the kings of Norway to enhance their legitimacy.When reading Snorri's history, Narikawa suggests, "we should also keep Heimskringla's own agenda in mind." That is, Snorri's agenda. "He needed to find a cultural as well as political supporter abroad," so that he could become the ruler of Iceland. By writing a flattering history, Snorri hoped to get a king on his side. How that worked out, well, you can read in Song of the Vikings.

Published on May 27, 2015 06:31

May 20, 2015

Saga vs Novel

Juxtaposition is one of my favorite words. So I was understandably thrilled when a 2014 essay by Ben Yagoda in Slate, complaining "Does Novel Now Mean Any Book?" crossed my (virtual) desk at the same time as a 2002 academic paper by Torfi Tulinius of the University of Iceland called "Egils Saga and the Novel."

Juxtaposition is one of my favorite words. So I was understandably thrilled when a 2014 essay by Ben Yagoda in Slate, complaining "Does Novel Now Mean Any Book?" crossed my (virtual) desk at the same time as a 2002 academic paper by Torfi Tulinius of the University of Iceland called "Egils Saga and the Novel."What is a novel? Seems no one knows. Yagoda, who writes nonfiction and only nonfiction, got his nose out of joint when someone called him a novelist. "I got on Twitter and sent out a tweet asking people if they were familiar with the 'novel = book' custom." He received numerous replies, including one from a very exasperated literary agent: "In queries: ALL THE TIME. People telling me of their 'nonfiction novel' or their 'fictional novel.'"

I admit that "fictional novel" is one phrase that makes me cringe.

That said, I'm the last person you should ask to define "novel." The more closely I look at the question, the harder it is for me to explain the difference between fiction and nonfiction, even though I've published both.

If you get your facts wrong when writing a novel--for example, if your Vikings eat potatoes or you kick your horse in the withers--your story fails.

But to write nonfiction you have to leave out a lot of what "really happened." You have to shape the truth. And you have to speculate (i.e., write fiction) to fill in the gaps between your facts.

And often what you thought was a historical fact you find, if you dig back far enough through your sources, was some prior writer's speculation.

That's especially true when you're writing, like I do, about the Middle Ages. There are an awful lot of gaps in what we know about the world a thousand years ago. And a lot of what we "know" comes from texts that, today, we might be inclined to call novels.

Like Egil's Saga.

Like Egil's Saga.Derived from the Icelandic verb "to say," the word "saga" implies neither fact nor fiction. Of the 140 known medieval Icelandic sagas, some are fantasies, some are biographies, some are chronicles--as fact-filled as any medieval text--some approach memoirs, and others may best be described as novels.

For hundreds of years, scholars have argued over whether the sagas are "history" or "fiction."

An Icelander writing in 1957 considered the sagas too good to be true: “A modern historian will for several reasons tend to brush these sagas aside as historical records," he said. "The narrative will rather give him the impression of the art of a novelist than of the scrupulous dullness of a chronicler.”

Archaeologists, too, dismiss the sagas as fiction, though there are notable exceptions. Jesse Byock of UCLA has led excavations in Iceland for twenty years; he and his colleague Davide Zori wrote in 2013, “We employ Iceland’s medieval writings as one of many datasets in our excavations, and the archaeological remains that we are excavating … appear to verify our method.” Of his team’s discovery of a Viking Age church and graveyard, he said, Egil’s Saga “led us to the site.”

Perhaps the greatest of the Icelandic Family Sagas, Egil's Saga may have been written by Snorri Sturluson, as I argued in Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myth. Much of my argument was based on Torfi Tulinius's analysis--though this particular paper, "Egils Saga and the Novel," somehow escaped me.

Egil's Saga, Torfi begins, is "a book born of other books." Among its themes are "the status of poetry in human life" and "the individual's need to define himself."

The world of the saga is "both same and different." It is not the 13th-century world of the author, but a fictional 10th-century world against which Snorri and his peers could "project their hopes and worries as well as their ideas about themselves."

The story is realistic--it is "set within a landscape everybody knows"--but it is not true. "It is probable that somebody called Egill actually lived at Borg in the 10th century," Torfi says. "Egils Saga, though, is a work of language." The characterization of this Egill and the events he takes part in may be "purely fictional."

"The originality of Egils Saga--and this is what makes it a novel--is that here it is the audience's own history and reality which are offered to interpretation," Torfi concludes. "However, no keys are given, except those which lie hidden in the text."

As Ben Yagoda documents, readers today have a hard time telling the difference between fictional-by-definition novels and nonfiction books. "An (unnamed) major metropolitan newspaper, in its obituary of Louis Zamperini, referred to Laura Hillenbrand's book about him, Unbroken, as a 'novel,'" he scoffs. An "actual class assignment from an actual (unnamed) school" referred to Barbara Ehrenreich's Nickel and Dimed and Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel as novels.

As Ben Yagoda documents, readers today have a hard time telling the difference between fictional-by-definition novels and nonfiction books. "An (unnamed) major metropolitan newspaper, in its obituary of Louis Zamperini, referred to Laura Hillenbrand's book about him, Unbroken, as a 'novel,'" he scoffs. An "actual class assignment from an actual (unnamed) school" referred to Barbara Ehrenreich's Nickel and Dimed and Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel as novels.Yagoda blames, in part, "the blurring of generic boundaries, and the fuzziness of 'truth' in the postmodern era," but, as any medievalist can tell you, that blurring and fuzziness has a long history.

In 800 years, who will know what parts of Unbroken are true and what parts were the writer's speculation? What moments of Louis Zamperini's life did she (of necessity) leave out? And what keys to interpretation lay hidden in the text? If someone else wrote a nonfiction book about Zamperini, would it be the same? Of course not.

A nonfiction book, like a novel, is "a work of language." Perhaps we should call them all sagas.

"Egils Saga and the Novel" by Torfi Tulinius was published in Snorri Sturluson and the Roots of Nordic Literature (Sofia, Bulgaria: University of Sofia, 2002). Download it at Academia.edu.

Read Yagoda's essay at http://www.slate.com/blogs/lexicon_valley/2014/08/04/novel_increasingly_used_to_mean_any_book_fiction_or_nonfiction.html

Published on May 20, 2015 08:02

May 6, 2015

Vikings in the Canadian North?

The Icelandic sagas tell of several Viking voyages to Vinland, or North America, a thousand years ago. Scholars have long agreed, though, that the sagas don't tell of every voyage--and they've long disagreed on where the Vikings went.

The Icelandic sagas tell of several Viking voyages to Vinland, or North America, a thousand years ago. Scholars have long agreed, though, that the sagas don't tell of every voyage--and they've long disagreed on where the Vikings went.When I was researching my nonfiction book The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman in 2006, the scholarly consensus was that L'Anse aux Meadows, on the northwestern tip of Newfoundland, was the only authenticated Viking settlement in the New World. Birgitta Wallace, the lead archaeologist on the project, speculated that the Vikings traveled from there at least as far as south as the Miramichi River. (For her argument, see my post "The Case of the Butternuts.")

When I wrote my young adult novel, The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler (just published by Namelos), I followed Birgitta's suggestion and placed Gudrid and Karlsefni's house on the banks of the Miramichi.

If I'd listened to a different archaeologist, though, I might have sent Gudrid north. For there is now a second authenticated Viking settlement in the New World: on Baffin Island.

Ian Robertson, a reader of this blog, has been helpfully keeping me up-to-date with the work of Canadian archaeologist Patricia Sutherland, now affiliated with the University of Aberdeen. In 2009, Sutherland published an exciting paper reanalyzing some older finds from the Arctic North. She and her colleagues have now followed that up with a paper in Geoarchaeology that--at least for me--puts all other arguments to rest: There were Viking explorers on Baffin Island a thousand years ago.

Sutherland identifies four sites at which Norse objects--or, as she more carefully says, "objects associated with a variety of European technologies"--have been found.

Yarn spun from animal hair.

Bar-shaped whetstones.

Notched wooden sticks that look like Viking tally-sticks.

And now, a crucible used for making bronze.

This small, broken stone vessel was found at a site called Nanook. It was near "a large structure with long straight walls of boulders and turf and a stone-edged drainage channel." The indigenous Dorset people, a Paleo-Eskimo culture, did not build houses like this. The Vikings did, throughout the North Atlantic, including in Greenland.

Under two inches high, the crucible was carved from a gray metamorphic rock not found near Nanook. Among the possible sources are the west coast of Greenland.

When Sutherland and her colleagues examined the crucible under a scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford Energy Dispersive Spectra (EDS) system for chemical analysis, they found "abundant traces of copper-tin alloy (bronze) as well as glass spherules similar to those associated with high-temperature processes. These results indicate that it had been used as a crucible" in which copper and tin were melted, "probably for the casting of small bronze objects."

The Dorset Eskimos, who lived in this area throughout the Viking Age and until being pushed out by the Inuit in the 13th or 14th century, did not make bronze. In fact, no one in North America north of Mexico knew how to make bronze.

But the Vikings did.

To learn more, read "Evidence of Early Metalworking in Canada" by Patricia D. Sutherland, Peter H. Thompson, and Patricia A. Hunt in Geoarchaeology 30 (2015): 74-78.

Published on May 06, 2015 06:53