Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 21

April 4, 2012

Lord of the Ring of the Nibelungs

My biography of the Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Viking: Snorri and the Making ofNorse Myth, has just gone into production at Palgrave-MacMillan. Theofficial publication date is October 30. (Loud cheers and hurrahs!) Here's an attemptI made to explain Snorri's importance. Clever readers will also see that itexplains the name of this blog, "God of Wednesday": Peter Jackson's long-awaited film of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit is in production in NewZealand.

"Das Rheingold," thefirst episode in the Metropolitan Opera's thrilling new production of RichardWagner's four-opera cycle, "The Ring of the Nibelungs," is being sung in NewYork tonight.

What do these cultural blockbusters have in common, besidesdwarves, dragons and awe-inspiring technological wizardry?

The obvious answer is a magic ring.

Tolkien categorically denied any connection. In a letter tohis publisher in 1961, he slammed the Swedish edition of The Lord of the Rings, the sequel to The Hobbit. When the translator opined, "The Ring is in a certainway 'der Nibelungen Ring,'" Tolkien scoffed: "Both rings were round, and therethe resemblance ceases."

The translator's theory was "a farrago of nonsense," Tolkienwrote. "He is welcome to the rubbish, but I do not see that he, as atranslator, has any right to unload it here."

Yet connecting the two artists is neither rubbish nornonsense. Both Tolkien and Wagner based their fantastical worlds on thewritings of a thirteenth-century Icelander, Snorri Sturluson.

In 1851 a German translation of Snorri's Edda and parts of the Poetic Edda was given to Wagner. A laterGerman poem, the "Nibelungenlied," is often thought to be Wagner's inspiration,particularly since his "Ring," first performed in 1876, became the ultimateexpression of Germanic folk culture. But a point-by-point comparison showsWagner to be more indebted to Snorri.

In the 1920s, while teaching at Oxford, J.R.R. Tolkien triedto add Snorri to the English canon.He argued that reading Old Icelandic was more important than readingShakespeare—Icelandic was more influential, more central to our language andour modern world.

Snorri, son of Sturla, was a lover of poetry, a writer ofhistory and saga, and a teller of myths. One of the richest chieftains inIceland in the early 1200s, he could call up armies of thousands. He himselfwas not a fighter, but bought favors or won them at law. He had few scruples,and could out-argue anyone. He was fat, troubled by gout, given to soaking longhours in his hot tub while drinking stout ale—not a Viking warrior by anystretch of the imagination. Shortly after finishing his classic books in 1241,he was murdered cowering in his cellar: He had betrayed Iceland's otherchieftains and made a pact with the king of Norway, selling out Iceland'sindependence so he himself could be called an earl. And then, rather foolishly,he had betrayed the king.

Yet his work lives on. He may be the most influential writeryou've never heard of. His Edda maybe the most important book you've never read.

A 1909 translation calls it "the deep and ancient wellspringof Western culture."

All the stories we know of the Vikings' pagan religion—theNorse myths of Valhalla and the Valkyries, the World Tree Yggdrasil, theRainbow Bridge, Ragnarok or the Twilight of the Gods—come from Snorri. He isour major, and often our only,source.

Without Snorri, we would know next to nothing about the godfor whom Wednesday was named (Odin, Wagner's Wotan). Ditto Tuesday (Tyr),Thursday (Thor), and Friday (Freyja or Frigg).

The history of Scandinavia in the Viking Age (roughly 793 to1066) we know almost entirely through Snorri. With his vivid portraits of kingsand sea-kings, raiders and traders, he created the archetype of the Viking: thetall, blond, independent warrior who laughs in the face of death.

And from Snorri's books springs modern fantasy. All thenovels, films, video games, board games, role-playing games, and on-linemulti-player games that seem toborrow their elves, dwarves, dragons, wizards, and warrior women from The Lord of the Rings have, in fact,derived them from Snorri and the Icelandic literature Tolkien so loved.

In 2013 The Hobbitis forecast to arrive on the big screen. If you miss tonight's "Das Rheingold," you can guarantee your seats to nextseason's complete "Ring of the Nibelungs" performances by subscribing to theMet's 2012-13 season. When the magic of the rings envelops you, give a thoughtto an Icelander from long ago. Because of Snorri Sturluson's wizardry withwords, our modern culture is enriched by Northern fantasy.

Learn more about the Met's Ring series here: http://www.metoperafamily.org/metopera/season/subscriptions/ring/index.aspx?type=next

Keep up with Peter Jackson's "The Hobbit" here: http://www.thehobbitblog.com/?cat=1

Photos: Snorri Sturluson by Gustav Vigeland. Graffiti portrait of Snorri on a Reykjavik wall (photo by Cate Wood). Snorri by Christian Krogh.

For more about Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myth, stay tuned. I'll post the cover as soon as it's available. Have a place you want me to include on my book tour? Please contact me.

Published on April 04, 2012 06:28

March 28, 2012

Lambing Time in Greenland

Our neighbors' lambs are being born here in Vermont now, and soon it will be lambing time in Iceland too. I remember one Icelandic friend of mine, sad that they were giving up sheep-farming, say, “But it won’t be spring without lambs bouncing around.”

Our neighbors' lambs are being born here in Vermont now, and soon it will be lambing time in Iceland too. I remember one Icelandic friend of mine, sad that they were giving up sheep-farming, say, “But it won’t be spring without lambs bouncing around.”I’ve never been in Iceland during lambing time, but when I went to Greenland to see Eirik the Red’s Viking settlement there in May 2006, the people who lived on Eirik’s old farm, Brattahlid, were in the middle of lambing season. They had learned their craft—and bought their sheep—in Iceland, and were trying to recreate (with government help) the Viking economy.

Jacky of Blue Ice Explorers warned me, when he rented a cottage for me on a Greenlandic farm, that I wouldn’t see much of the farmers, and I didn’t. They were hardly sleeping, two needing to be in the sheep house twenty-four hours a day. But one day I did get a tour of the barn. My hostess, Ellen, was small and patient and proud of her sheep. When she spoke—to me in English, to her kids in Greenlandic—her voice was soft and even, and she raised it only slightly in surprise when a young ram butted the housedoor with a bang. She slipped out and grabbed his horns before calling to me to follow.

The ram, nearly as big as she, was a yearling, bottlefed last May because he was born too small. “Now he won’t stay with the other sheep,” Ellen explained. “He likes to come in the house. Watch out he doesn’t hurt you.”

Holding tight to both of his impressively curled horns, she dragged him off the porch and through a muddy stream to the barn, then waved me inside before shooing him away.

The high, wide barn was divided lengthwise into five aisles, each about six feet wide and filled with sixty jostling, curious, pregnant ewes. We walked between two aisles on a raised boardwalk, which was also where the sheep’s noontime hay was piled (and the dogs were napping). It smelled very sweet. Ellen’s husband Carl and a helper were busy in the aisles, both slim, short, dark, sweaty, and tired. Carl had a wide, open face and a brightness to his expression, as if he’d like to speak to me but couldn’t, knowing no English. Instead he merely smiled, hopped nimbly up out of the pen in front of me and stretched up to the rafters to fetch down a wooden grate that he then slipped into grooves in the sides of the aisle to separate off a ewe and her two lambs. The far end of the aisle, I noticed, was already divided that way all along its length into little ewe-and-lamb-sized pens.

The high, wide barn was divided lengthwise into five aisles, each about six feet wide and filled with sixty jostling, curious, pregnant ewes. We walked between two aisles on a raised boardwalk, which was also where the sheep’s noontime hay was piled (and the dogs were napping). It smelled very sweet. Ellen’s husband Carl and a helper were busy in the aisles, both slim, short, dark, sweaty, and tired. Carl had a wide, open face and a brightness to his expression, as if he’d like to speak to me but couldn’t, knowing no English. Instead he merely smiled, hopped nimbly up out of the pen in front of me and stretched up to the rafters to fetch down a wooden grate that he then slipped into grooves in the sides of the aisle to separate off a ewe and her two lambs. The far end of the aisle, I noticed, was already divided that way all along its length into little ewe-and-lamb-sized pens. “There,” Ellen nudged me and pointed toward our feet.

A birth-slick white lamb lay sprawled on the aisle floor, glistening, two ewes competing to lick it dry. “Will the others step on it?” I asked.

“Only if they are scared,” she said, and I held very still until Carl reached it. The new lamb’s fleece by then was just starting to curl. Carl lifted it carefully by its head and carried it down the aisle to make it a pen, both ewes anxiously trotting behind him. He held the grate high for a moment until only one ewe was on the lamb’s side, then quickly slid it into place, leaving the second ewe trapped, baahing miserably, outside.

“How does he know which one is the mother?” I asked.

“Its rear end is bloody. And the other one is fatter.”

Off the back of the barn was a spacious shed carpeted with hay, to which the lambs graduated in groups of ten or so when they were strong enough. There, Ellen said, they “learned to find their mothers” before being taken up to the mountain pastures and let loose until October, when they are rounded up, sorted, and sent by boat to the slaughterhouse.

It’s a short, but sweet, life for mountain-raised lamb.

If you want to visit the Viking sites in Greenland, I recommend Blue Ice Explorer at http://www.blueice.gl/ in south Greenland. Greenland doesn’t export lamb, as far as I know, but you can often buy Icelandic mountain-raised lamb at Whole Foods; on their website, read “The Tender Story of Icelandic Lamb.” It’s the wild thyme and other herbs they graze on all summer that makes it so delicious.

Published on March 28, 2012 07:24

Lambing Time

Our neighbors' lambs arebeing born here in Vermont now, and soon it will be lambing time in Icelandtoo. I remember one Icelandic friend of mine, sad that they were giving upsheep-farming, say, "But it won't be spring without lambs bouncing around."

Our neighbors' lambs arebeing born here in Vermont now, and soon it will be lambing time in Icelandtoo. I remember one Icelandic friend of mine, sad that they were giving upsheep-farming, say, "But it won't be spring without lambs bouncing around."I've never been in Icelandduring lambing time, but when I went to Greenland to see Eirik the Red's Vikingsettlement there in May 2006, the people who lived on Eirik's old farm,Brattahlid, were in the middle of lambing season. They had learned theircraft—and bought their sheep—in Iceland, and were trying to recreate (withgovernment help) the Viking economy.

Jacky of Blue Ice Explorerswarned me, when he rented a cottage for me on a Greenlandic farm, that Iwouldn't see much of the farmers, and I didn't. They were hardly sleeping, twoneeding to be in the sheep house twenty-four hours a day. But one day I didget a tour of the barn. My hostess, Ellen, was small and patient and proud ofher sheep. When she spoke—to me in English, to her kids in Greenlandic—hervoice was soft and even, and she raised it only slightly in surprise when ayoung ram butted the housedoor with a bang. She slipped out and grabbed hishorns before calling to me to follow.

The ram, nearly as big as she,was a yearling, bottlefed last May because he was born too small. "Now he won'tstay with the other sheep," Ellen explained. "He likes to come in the house.Watch out he doesn't hurt you."

Holding tight to both of hisimpressively curled horns, she dragged him off the porch and through a muddystream to the barn, then waved me inside before shooing him away.

The high, wide barn wasdivided lengthwise into five aisles, each about six feet wide and filled withsixty jostling, curious, pregnant ewes. We walked between two aisles on araised boardwalk, which was also where the sheep's noontime hay was piled (andthe dogs were napping). It smelled very sweet. Ellen's husband Carl and ahelper were busy in the aisles, both slim, short, dark, sweaty, and tired. Carlhad a wide, open face and a brightness to his expression, as if he'd like tospeak to me but couldn't, knowing no English. Instead he merely smiled, hoppednimbly up out of the pen in front of me and stretched up to the rafters tofetch down a wooden grate that he then slipped into grooves in the sides of theaisle to separate off a ewe and her two lambs. The far end of the aisle, Inoticed, was already divided that way all along its length into little ewe-and-lamb-sizedpens.

The high, wide barn wasdivided lengthwise into five aisles, each about six feet wide and filled withsixty jostling, curious, pregnant ewes. We walked between two aisles on araised boardwalk, which was also where the sheep's noontime hay was piled (andthe dogs were napping). It smelled very sweet. Ellen's husband Carl and ahelper were busy in the aisles, both slim, short, dark, sweaty, and tired. Carlhad a wide, open face and a brightness to his expression, as if he'd like tospeak to me but couldn't, knowing no English. Instead he merely smiled, hoppednimbly up out of the pen in front of me and stretched up to the rafters tofetch down a wooden grate that he then slipped into grooves in the sides of theaisle to separate off a ewe and her two lambs. The far end of the aisle, Inoticed, was already divided that way all along its length into little ewe-and-lamb-sizedpens. "There," Ellen nudged me andpointed toward our feet.

A birth-slick white lamb laysprawled on the aisle floor, glistening, two ewes competing to lick it dry."Will the others step on it?" I asked.

"Only if they are scared,"she said, and I held very still until Carl reached it. The new lamb's fleece bythen was just starting to curl. Carl lifted it carefully by its head andcarried it down the aisle to make it a pen, both ewes anxiously trotting behindhim. He held the grate high for a moment until only one ewe was on the lamb'sside, then quickly slid it into place, leaving the second ewe trapped, baahingmiserably, outside.

"How does he know which one isthe mother?" I asked.

"Its rear end is bloody. Andthe other one is fatter."

Off the back of the barn wasa spacious shed carpeted with hay, to which the lambs graduated in groups often or so when they were strong enough. There, Ellen said, they "learned tofind their mothers" before being taken up to the mountain pastures and letloose until October, when they are rounded up, sorted, and sent by boat to theslaughterhouse.

It's a short, but sweet,life for mountain-raised lamb.

If you want to visit the Viking sites in Greenland, Irecommend Blue Ice Explorer at http://www.blueice.gl/ in southGreenland. Greenland doesn't export lamb, as far as I know, but you can often buy Icelandicmountain-raised lamb at Whole Foods; on their website, read "The Tender Story of Icelandic Lamb." It's the wild thyme and other herbs they graze on all summerthat makes it so delicious.

Published on March 28, 2012 07:24

March 21, 2012

A 19th-Century Traveler in Iceland

When I write about Iceland--or wherever I travel--I try to avoid sounding judgmental. I'm there to learn, to see something new. I hate the current fashion of snarky travel-writing and had always thought it something rather modern.

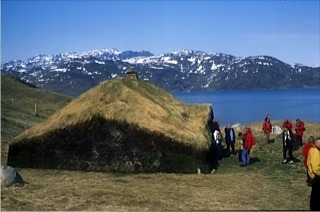

It's not. Here's a description of the inside of an Icelandic turfhouse--especially the main room or badstofa--from a report on leprosy in Iceland filed in 1895 by Dr. Edward Ehlers. (Thanks to Jack in Colorado for sending me this):

"The Badstofa has six to eight fixed bedsteads, or rather large wooden boxes, each box intended for two or three persons, who usually sleep head against feet and feet against head. "If you enter this Badstofa when 13 to 14 persons lie sleeping there, first of all you feel a temperature which certainly both summer and winter reminds you of the tepidarium of a Roman bath, but surely here the likeness ceases. A suffocating stink and an unwholesome smell meets you. It is the smell of the mouldy hay, of the sheepskin quilts that are never dried or aired; it is the smell of the dirt which is dragged into the house on the clumsy Icelandic skin shoes that want double soles, and are quite unqualified to keep out the dampness.

"The Badstofa has six to eight fixed bedsteads, or rather large wooden boxes, each box intended for two or three persons, who usually sleep head against feet and feet against head. "If you enter this Badstofa when 13 to 14 persons lie sleeping there, first of all you feel a temperature which certainly both summer and winter reminds you of the tepidarium of a Roman bath, but surely here the likeness ceases. A suffocating stink and an unwholesome smell meets you. It is the smell of the mouldy hay, of the sheepskin quilts that are never dried or aired; it is the smell of the dirt which is dragged into the house on the clumsy Icelandic skin shoes that want double soles, and are quite unqualified to keep out the dampness. "In this dirt a confused mixture of cats, dogs, and children lie reeking on the floor, exchanging caresses and echinococci; it is the smell of the wet stockings and the woollen shirts which hang to dry next to a slice of dried halibut ("Rekling") or the dried cod's head--this dreadful irrational favourite dish, for which the Icelander pays four kroner (4s. 6d.) a hundred. And if you poke your nose into the corners of the Badstofa, you will find a bucket in which the urine of the whole party is gathered; it is considered good for wool-washing.

"I shall never succeed in picturing all the details of such an interior, which, in addition, you may imagine as being heated in the winter, at the places where they have no turfs, with the sheep's dried excrements, a kind of fuel which spreads a penetrating smell of nitre and burnt wool." Dr. Ehlers was in Iceland to research the causes of leprosy. His conclusion: "It is the absolute want of cleanliness plus Armauer Hansen's bacillus, which in such an interior finds its true paradise." You can read his whole essay in Newman, Ehlers, and Impey, Prize Essays on Leprosy (London: New Sydenham Society, 1895), pp 169-70, available on Open Library.

"I shall never succeed in picturing all the details of such an interior, which, in addition, you may imagine as being heated in the winter, at the places where they have no turfs, with the sheep's dried excrements, a kind of fuel which spreads a penetrating smell of nitre and burnt wool." Dr. Ehlers was in Iceland to research the causes of leprosy. His conclusion: "It is the absolute want of cleanliness plus Armauer Hansen's bacillus, which in such an interior finds its true paradise." You can read his whole essay in Newman, Ehlers, and Impey, Prize Essays on Leprosy (London: New Sydenham Society, 1895), pp 169-70, available on Open Library.

If you want to visit a badstofa, I recommend the one pictured above, from the Skagafjord Heritage Museum at Glaumbaer in northern Iceland. It was the home of Gudrid the Far-Traveler, heroine of my nonfiction book, The Far Traveler. If you visit Glaumbaer, be sure to say hi to Sirri for me. And don't miss the opportunity to try the fish soup in the museum restaurant.

Published on March 21, 2012 06:48

March 14, 2012

A Visit to Greenland

I stayed in Greenland's tiny capital city, Nuuk, fortwo weeks in 2006, while researching my book The Far Traveler. My hosts were Kristjana,an Icelander, and her husband, Jonathan Motzfeldt, an Inuit known as the"father of his country" for having negotiated Greenland's semi-independencefrom Denmark. Jonathan was prime minister of the Home Rule government for manyyears and remained a significant voice in politics when I met him; he died in2010. Here's how I remember him:

I stayed in Greenland's tiny capital city, Nuuk, fortwo weeks in 2006, while researching my book The Far Traveler. My hosts were Kristjana,an Icelander, and her husband, Jonathan Motzfeldt, an Inuit known as the"father of his country" for having negotiated Greenland's semi-independencefrom Denmark. Jonathan was prime minister of the Home Rule government for manyyears and remained a significant voice in politics when I met him; he died in2010. Here's how I remember him:One night over tea andcookies, we watched a Greenlandic TV program about independence, on which hewas featured. I asked if he was in favor of it. "Someday," he replied, "but notin my time." Although ninety percent of Greenland's people are indigenous Inuit,Danish subsidies, he explained, built Greenland's airports and publicbuildings, including the new university complex going up next to the Instituteof Natural Sciences, where Kristjana works. Half of the Home Rule government'sexpenditures come from Denmark—and nearly half of Greenland's workers aregovernment employees. Initiatives the Danes are backing include mining forgold, extracting low-temperature enzymes from glacial lakes, bottling glacierwater, tourism and archaeology, and—harking back to the Viking era—sheepfarming.

For dinner, Jonathan hadboiled a joint from a sheep raised on Eirik the Red's farm—an old sheep, he said, his dark face litwith a cartoonish grin. He repeated it several times, with emphasis, "Eirik theRed's ooooold sheep." He seemed to betesting the extent of my American fussiness (later he would serve boiledeiderduck and noisily enjoy sucking the duck's feet). But I knew he wasteasing. I had taken to him the first time we met. Trim and neat, he turnedKristjana into a giant: he hardly came up to her ear. His smile was as sunny asa child's—and as apparently irrepressible. Appropriately solemn-faceddiscussing the eight suicides Nuuk had seen in the two weeks since I hadarrived in Greenland, he was beaming again as soon as Kristjana changed thesubject. Now, he served the sheep broth first, tiny potatoes and rice floatingin it, then put the big, dry, chewy hunkof grayish meat and bone, glistening with little white globs of fat, on aplatter. He handed me a penknife and a glass of red wine.

For dinner, Jonathan hadboiled a joint from a sheep raised on Eirik the Red's farm—an old sheep, he said, his dark face litwith a cartoonish grin. He repeated it several times, with emphasis, "Eirik theRed's ooooold sheep." He seemed to betesting the extent of my American fussiness (later he would serve boiledeiderduck and noisily enjoy sucking the duck's feet). But I knew he wasteasing. I had taken to him the first time we met. Trim and neat, he turnedKristjana into a giant: he hardly came up to her ear. His smile was as sunny asa child's—and as apparently irrepressible. Appropriately solemn-faceddiscussing the eight suicides Nuuk had seen in the two weeks since I hadarrived in Greenland, he was beaming again as soon as Kristjana changed thesubject. Now, he served the sheep broth first, tiny potatoes and rice floatingin it, then put the big, dry, chewy hunkof grayish meat and bone, glistening with little white globs of fat, on aplatter. He handed me a penknife and a glass of red wine.One perk of Jonathan'sposition was the Motzfeldt's house: high, glass-fronted, it overlooked the baylike the prow of a ship. At the breakfast table one morning, his pipe curled ina meaty fist, Jonathan shouted out, "There!" and "There!," picking out herds ofseal as they swam by. Through binoculars, I saw a flurry of little triangularflippers and smooth black backs before they dove again. Another day, reading abook on Greenland from the Motzfeldts' excellent library, I was startled to myfeet by the Hoosh-Wash of a whalebreaching. Hurrying outside, I hung over the cliffside with a neighbor and hertwo children to see four more jets and a pair of flukes.

Each morning before the fogburned off, a flotilla of small boats would etch silver lines away from theharbor. There was no other way to get out of town, I'd soon learned, unless youflew.

"Do you notice all the boatsare going into the fjords?,"Kristjana said wistfully one day. She ran a hand through her blonde, boy-cuthair and took a drag on her cigarette. "That's where spring is."

I had been introduced toKristjana by an Icelandic friend, a botanist who worked with her in southernGreenland on a project to stem erosion caused by the sheep farming. Learning ofmy plans to visit the Viking sites near Nuuk, Kristjana had immediately volunteeredto take me there, but the Motzfeldts' boat had gone in for repairs in November,just after we started planning our trip, and being "father of your country"doesn't unfortunately get your boat fixed any sooner in Nuuk. Greenland,Kristjana agreed, was mis-named. It should have been called "Maybe-Land."

I had been introduced toKristjana by an Icelandic friend, a botanist who worked with her in southernGreenland on a project to stem erosion caused by the sheep farming. Learning ofmy plans to visit the Viking sites near Nuuk, Kristjana had immediately volunteeredto take me there, but the Motzfeldts' boat had gone in for repairs in November,just after we started planning our trip, and being "father of your country"doesn't unfortunately get your boat fixed any sooner in Nuuk. Greenland,Kristjana agreed, was mis-named. It should have been called "Maybe-Land.""Maybe you can go to Sandneswith Georg on Tuesday." Georg Nyegaard, a Danish archaeologist working at theNational Museum of Greenland, was going to inspect a farmer's potato patch nearthe Viking site: Greenland has no private property; every individual use ofland is approved and monitored by a government committee, and the museumofficials suspected this potato patch was encroaching on the archaeology.

"Maybe we can go with theSwedish ambassador," Kristjana said another day. "He said he'd like to seeSandnes. His yacht is luxury, muchbetter than our boat—except that one motor is broken."

Tupilak Travel had a boatgoing to a different spot known for Viking ruins—down the fjord just north ofNuuk—but the trip was cancelled at the last moment: The wind was too strong.

By the time the Motzfeldt'sboat was finally ready, Jonathan had been called away to Copenhagen andKristjana was drowning in things to do before she herself left for Italy a fewdays later. So she turned me and the boat over to Tobias, whom she introducedas Jonathan's chauffeur.

By the time the Motzfeldt'sboat was finally ready, Jonathan had been called away to Copenhagen andKristjana was drowning in things to do before she herself left for Italy a fewdays later. So she turned me and the boat over to Tobias, whom she introducedas Jonathan's chauffeur. "You have a map, you knowwhere you want to go, good, good," she said, brushing away my doubts. "Tobiaswill get you there"—despite the fact that he spoke no English (or Icelandic)and I spoke no Greenlandic (or Danish). His wife Rusina would be going, too, Ilearned when I met them at the boat early Saturday morning. "Beautiful!" shesaid, with an expansive wave of one hand, as we passed the dramatic mountainsthat marked the harbor mouth. It was her favorite (and almost her only) Englishword.

But we did get to the Vikingruins at Sandnes—you can read about it in TheFar Traveler—and we did, in spite of the strengthening wind and thegrowling sea, get safely back.

If you want to visit the Viking sites in Greenland, I recommend Blue Ice Explorer at http://www.blueice.gl/ in south Greenland. Jacky can do everything. If you make it to Nuuk, don't miss the Greenland National Museum, http://www.natmus.gl/. I also recommend Tupilak Travel, http://tupilaktravel.gl/en/.

Published on March 14, 2012 08:48

March 7, 2012

An Eye for Horses

Did you know it's "Read an e-book week"? To celebrate, my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse, published in 2001 and long out of print, is now on sale for 50% off at Smashwords.com. That's $4.99. Can't pass it up at that price.

Did you know it's "Read an e-book week"? To celebrate, my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse, published in 2001 and long out of print, is now on sale for 50% off at Smashwords.com. That's $4.99. Can't pass it up at that price.A Good Horse Has No Color has always been popular with Icelandic horse owners. But much of what I write applies to any breed of horse. This excerpt, for example, about my first ride on my horse Birkir in Iceland, was reprinted in the coffee-table book Heartbeat for Horses by Laura Chester and Donna Demari in 2007:

...Behind me I heard a rise in the conversation, then hoofbeats. The woman rode up on the darker horse and handed me her whip. I had seen other Icelanders ride with one, longer than a riding crop but a bit short for a dressage whip. This one had an engraved silver cap on its handle. I took it like I had expected it, and gave the horse a tap. Immediately he picked up a nice slow tolt, as if he'd been merely waiting for me to ask. It was a confident gait: His back felt soft and rounded and comfortable beneath me, his head was high, and his neck arched. His forelock blew back past his ears, and his dark mane rippled over my hands. He seemed to be enjoying himself, glad to be about, though not in any great hurry. I must have been smiling too, for the woman looked at me and beamed. She said something I didn't catch, and suddenly we were cantering up the hill. The horse had a fine, rolling canter. At the crest, we resumed the tolt, turned, cantered up the near hill, and tolted back to the barnyard. The horse stopped easily next to its fellow, and we got off. The rain was picking up again. Someone took the two horses into the stable. Another suggested coffee, and we all dashed for the house.

When we came back out, the rain was still steady, but inside the barn it was warm and brightly lit and comforting. A raised center aisle separated two large pens full of horses, each haltered and clipped to a rail. They stirred and stamped when we entered, and I looked along their orderly ranks for Birkir. Amazingly, I picked him out at once, the light bay with a star, and walked down the aisle toward him feeling as if he were already mine. Sigrun approached him from the rear, and the horses parted, leaving room for me to step into the pen and join her. We stood at his flank, looking him over, and he turned his head to watch us, his neck arced high, his ears pricked with curiosity. He had a dark, liquid, inquisitive eye, soft and friendly. Unlike Elfa, he was completely at ease around us. He did not sidle away when I reached to pat him—on the contrary, he poked his nose forward, dog-like, to the limits of his rope, as if looking for attention. I scratched behind his ears and ran my hand down his neck and along his smooth wide back. His mane and tail were thick and dark, his black stockings neat, his hooves well-shaped, his coat a glowing red. He seemed larger and sturdier than most Icelandics I'd seen, and it was clear he was in excellent health.

When we came back out, the rain was still steady, but inside the barn it was warm and brightly lit and comforting. A raised center aisle separated two large pens full of horses, each haltered and clipped to a rail. They stirred and stamped when we entered, and I looked along their orderly ranks for Birkir. Amazingly, I picked him out at once, the light bay with a star, and walked down the aisle toward him feeling as if he were already mine. Sigrun approached him from the rear, and the horses parted, leaving room for me to step into the pen and join her. We stood at his flank, looking him over, and he turned his head to watch us, his neck arced high, his ears pricked with curiosity. He had a dark, liquid, inquisitive eye, soft and friendly. Unlike Elfa, he was completely at ease around us. He did not sidle away when I reached to pat him—on the contrary, he poked his nose forward, dog-like, to the limits of his rope, as if looking for attention. I scratched behind his ears and ran my hand down his neck and along his smooth wide back. His mane and tail were thick and dark, his black stockings neat, his hooves well-shaped, his coat a glowing red. He seemed larger and sturdier than most Icelandics I'd seen, and it was clear he was in excellent health."He's beautiful," I said, and meant it. I was filled with desire, suddenly, to own this beast—filled with awe that it was possible to own a creature so fine, so alive—surprised that anyone would actually let me take him away…

Birkir fra Hallkelsstadahlid has been part of our family now for fifteen years. You can visit his home farm on the web at www.hallkelsstadahlid.is. To learn about Icelandic horses in general, go to the Icelandic Horse Congress's website at www.icelandics.org or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson's video blog, Hestakaup.com. Another good way to get to know Icelandic horses is by reading my friend Pamela Nolf's blog about her horse Blessi: blessiblog.blogspot.com.

Birkir fra Hallkelsstadahlid has been part of our family now for fifteen years. You can visit his home farm on the web at www.hallkelsstadahlid.is. To learn about Icelandic horses in general, go to the Icelandic Horse Congress's website at www.icelandics.org or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson's video blog, Hestakaup.com. Another good way to get to know Icelandic horses is by reading my friend Pamela Nolf's blog about her horse Blessi: blessiblog.blogspot.com. Finally, a nice surprise in my email this week was a note from 16-year-old Asha Brogan, who created a book trailer for A Good Horse Has No Color as an assignment for her high-school journalism class. Watch at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ike2e3wugk. As she explained in her note, she was unable to borrow an Icelandic horse, and so had to make do with a Welsh pony. Not quite the same, as anyone who has ridden an Icelandic horse will tell you.

(Middle photo of Birkir fra Hallkelsstadahlid by Jennifer Anne Tucker and Gerald Lang.)

Published on March 07, 2012 04:55

February 29, 2012

William Morris's Muse

Here's an essay I wrote for a contest (didn't win) about riding horses in Iceland:

"There's no bad weather, only poor clothing." That's one of my favorite Icelandic sayings, as I was reminded, daily, for a week in the summer of 1990, when I took a horse trek in southern Iceland. It was billed as "a trip for people who have a taste for uninhabited areas far from any luxury." It was run by the company Hekla Horses, named for the nearby volcano long known as the Mouth of Hell. We rode five hours a day in drizzle or worse, with only a few spells of misty calm to tempt a lowering of our hoods. My rainpants proved leaky. Though warm enough, I grew sticky behind and uncomfortable in the saddle. My hands, wet through three layers of gloves, were claws.

We rode along a leaping river and down farmers' lanes, encountering loose sheep and cows, horses and herd-dogs. Ducks filled the river's rare calm pools. Snipe whirred and tittered overhead. From the fenceposts whimbrels sighed (Icelanders liken the sound to porridge bubbling). Redshanks flew shrieking off the sandflats. We passed a meadow yellow with buttercups. I shut my eyes often -- for cold, rain, dirt, fatigue, fun -- as we rode across an interminable black sand waste, past a booming waterfall called Troll Woman's Leap, a mesa-shaped hill now on our right, now on our left. The Mouth of Hell remained hidden in clouds. In spite of the flurry of my horse's hooves, I felt strangely motionless, strangely light, balanced between the mountains, floating between sand and sky.

We were on our way to a national park deep in the deserted highlands. The park is renowned for the fanciful colors of its geology -- a pea-green chasm, a blue hill, tawny ridges, a lemon-yellow sulfur pit, a cliff-face with candy-pink stripes. From the top of the blue hill, a far-off cluster of lakes mirrors the sky, while on every horizon glaciers lift like white turreted castles.

We were on our way to a national park deep in the deserted highlands. The park is renowned for the fanciful colors of its geology -- a pea-green chasm, a blue hill, tawny ridges, a lemon-yellow sulfur pit, a cliff-face with candy-pink stripes. From the top of the blue hill, a far-off cluster of lakes mirrors the sky, while on every horizon glaciers lift like white turreted castles.Or so the tour books say. We saw little of it. It rained for six days straight. Misty rain, wind-driven rain, chilling rain, rain that cut visibility back to the ears of my horse. Once the horses turned tail and refused to go forward into the gusts.

Our guide, Jon, taught us songs. "Ride on, ride on, ride over the sands. The elf-queen is bridling her steed." Jon had a high, strong bellow of a voice, nasal but tuneful, piercing and sad. "Lord lead my horse, this last part is hard."

In 1871, the writer and Arts-and-Crafts designer William Morris toured Iceland. He, like I, was enamored of the medieval Icelandic sagas, Iceland's claim to literary fame. He, like I, thrilled to see the farms, the dales, the mountains mentioned in those tales from a thousand years ago. Tales of sheep-farmers and sorcerors, horse fights and feuds, love and grief and strife. Tales of a hard life scratched from an unforgiving land. Tales tempered with poetry and grace. He, like I, rode a long way in the rain, over rugged terrain on a trusty horse, happy to come at last to a house and begin to feel his hands and feet again. He wrote of cresting a hill and receiving "that momentary insight into what the whole thing means that blesses us sometimes and is gone again."

In 1871, the writer and Arts-and-Crafts designer William Morris toured Iceland. He, like I, was enamored of the medieval Icelandic sagas, Iceland's claim to literary fame. He, like I, thrilled to see the farms, the dales, the mountains mentioned in those tales from a thousand years ago. Tales of sheep-farmers and sorcerors, horse fights and feuds, love and grief and strife. Tales of a hard life scratched from an unforgiving land. Tales tempered with poetry and grace. He, like I, rode a long way in the rain, over rugged terrain on a trusty horse, happy to come at last to a house and begin to feel his hands and feet again. He wrote of cresting a hill and receiving "that momentary insight into what the whole thing means that blesses us sometimes and is gone again."Once while we rested our horses at a crossroads, Jon shared out bars of chocolate. Each other rider broke off a square or two, but I refused. I didn't want to strip off my layers of soggy gloves. Jon nodded. He bared his own hand, broke off a square, and brought it to my lips.

Twenty years on, I can still smell the wet wool of his sleeve-end, see the manure grime in the heart-line of his palm, his squint of a smile as I opened my lips to this outlaw priest and his bitter wafer.

Hekla Horses is still in business. I highly recommend the six-day Landmannalaugar trip (I've taken it twice). See http://hekluhestar.is/. For a great website on Icelandic horses in general, visit The Icelandic Horse Congress at www.icelandics.org. You can also take a virtual trek on my friend Stan Hirson's video blog, Hestakaup.kom. Finally, to learn more about Iceland and Icelandic horses, don't forget my book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse!

Published on February 29, 2012 05:40

February 22, 2012

Arabic Science Comes to the West

To write my most recent book,

The Abacus and the Cross

, I traveled throughout Europe interviewing experts on medieval science around the year 1000, focusing especially on the interests of the Scientist Pope, Gerbert of Aurillac: Arabic numerals, the astrolabe, celestial spheres, the acoustics of organ pipes, and astrology. None of this material made it into the final book, but in coming weeks I'll be sharing here a few vignettes of "the writer at work":

To write my most recent book,

The Abacus and the Cross

, I traveled throughout Europe interviewing experts on medieval science around the year 1000, focusing especially on the interests of the Scientist Pope, Gerbert of Aurillac: Arabic numerals, the astrolabe, celestial spheres, the acoustics of organ pipes, and astrology. None of this material made it into the final book, but in coming weeks I'll be sharing here a few vignettes of "the writer at work":I was in the manuscript reading room of the National Library of France in Paris, a bright, hushed room, floor-to-ceiling bookcases to my left, floor-to-ceiling windows to my right, ranks of long tables studded with wooden bookrests and velvet rolls to gently prop open the fragile parchment pages. Most of the chairs were filled with hunched-over scholars.

To be admitted I had to write ahead and state my credentials, submit to an interview, show my passport, prove myself a "scholar" by handing over a letter from my publisher, be photographed (at another desk), get a plastic ID card, go down to the cashier and pay seven euros for the card to be activated for three days and to get three paper tickets. Up to the manuscript room, where I handed the ID card and one ticket to the clerk. She gave me a key to a locker, where I had to leave all my belongings except one pencil (not a pen, with which I could deface a manuscript) and a notebook. Reentering the reading room, I had to display my pencil and notebook to the clerk to get back my ID card and the ultimate prize: a plastic block with a number on it. I was then permitted to sit in a chair -- but not look at any manuscripts, yet.

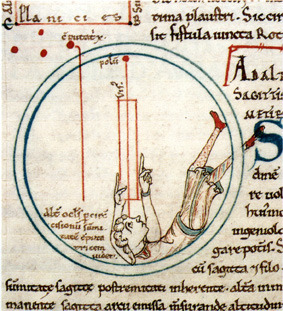

A medieval astronomer. From a

A medieval astronomer. From amanuscript in Avranches, France.

David Juste, the medievalist from the University of Sydney who had invited me to meet him there, sat down beside me. "What you will see here," he whispered, "is the earliest Latin manuscript to contain Arabic words. The earliest proof of the transmission of Arabic science to the West. Now I will order the manuscript."

He filled out a form and took it to another desk.

Ten minutes later, the manuscript arrived from the vault. "Believe it or not," Juste said, "I think I have seen two thousand manuscripts in my life, and this was the very first one I saw."

It was a rather thin little book, with a newish leather binding. The parchment was off-white with brown letters, undistinguished. Juste turned the page, did the classic French kissing of the finger tips: "This is it."

It was made in Limoges, he told me, slipping on the de riguer white gloves, a hundred miles north of Aurillac, between 978 and 1000 -- during Gerbert of Aurillac's lifetime. Parts were copied from an earlier manuscript, now lost, that Juste believes came from Catalonia; other parts came from Fleury, including a work by Abbot Abbo of Fleury (Gerbert's worst enemy) on cosmology. Most of the book, however, is about fortune-telling and astrology, not what we would call the science of the stars.

Juste looked around nervously. "Wait a minute. We have to be very careful. I expect we'll get in trouble. We are not supposed to consult the manuscripts together. Why? It's the rules. The rules are very strict. I have an idea." He got up. "I'll try something." He intercepted a different clerk, a young woman who had just come from a back room. She studied me, then curtly nodded. He hurried back and swept up the manuscript.

"This way. I asked for special permission to talk." We went into the back room, where a trio who looked like professor and students were discussing another manuscript. We sat down at the opposite end of the long table; the clerk closed the door.

Juste relaxed. He began flipping through the pages, pointing to letters, running his finger along a line, thumbing pages back and forth -- for all the hoopla, he didn't treat "the earliest proof of the transmission of Arabic science to the West" as a sacred object. It was a book.

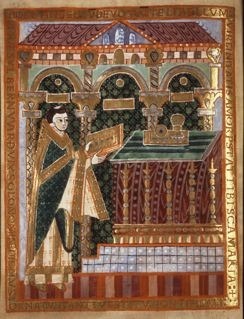

photo captions: A medieval astronomer. From a manuscript in Avranches, France. Bernward of Hildesheim presenting his book

to the Virgin (Dom Museum Hildesheim).

Published on February 22, 2012 04:08

February 15, 2012

The Volcano Show

The New York Post called it "The Volcano that Shut Down the World." The ash cloud from Iceland's Eyjafjallajokull eruption in April 2010 caused more than $1 billion in losses to the airline industry and grounded thousands of travelers for days. In Iceland, it wiped out roads and water lines and covered farms with four inches of cement-like ash.

The New York Post called it "The Volcano that Shut Down the World." The ash cloud from Iceland's Eyjafjallajokull eruption in April 2010 caused more than $1 billion in losses to the airline industry and grounded thousands of travelers for days. In Iceland, it wiped out roads and water lines and covered farms with four inches of cement-like ash.But when I was there that Easter weekend, it was just a "tourist eruption." I was one of 15,000 people who hiked, rode snowmobiles or jeeps, or flew helicopters or planes to the site.

Why did we go?

"Volcanoes are sublime," said one person I asked. "It's terrorizing and beautiful -- and beautiful because it's terrorizing."

Said another, "I was depressed because I'd lost my job, and this woke me right up. Mother Nature was playing a role in my life." He added, "You must experience this with your own eyes."

I booked a jeep tour. Three hours from Reykjavik, we let some air out of our tires and climbed onto a glacier. We drove an hour on the icecap, guided by GPS, and parked in a long line of jeeps.

A half-mile away loomed a black caldron, with gray-blue arms of lava stretching out over the snow. It sighed and breathed like a magical being, sending up mesmerizing red fountains of molten rock. Some bombs arced so high they looked like shooting stars. Others bounced on the crater rim and rolled like gold coins. At the cooling face, the lava bulged and broke, tinkling like bits of glass. As the sun set, the colors grew more vivid. A fluorescent yellow tongue oozed over the crater side. Lines of orange lights twinkled on the dark ridges of rock. The lava fountains turned hot pink.

A half-mile away loomed a black caldron, with gray-blue arms of lava stretching out over the snow. It sighed and breathed like a magical being, sending up mesmerizing red fountains of molten rock. Some bombs arced so high they looked like shooting stars. Others bounced on the crater rim and rolled like gold coins. At the cooling face, the lava bulged and broke, tinkling like bits of glass. As the sun set, the colors grew more vivid. A fluorescent yellow tongue oozed over the crater side. Lines of orange lights twinkled on the dark ridges of rock. The lava fountains turned hot pink.Ten days later, the volcano forced a new channel straight up. Hot lava hit the ice our jeep had been parked on and blasted it 35,000 feet in the air. No tourists were there that day -- it was snowing too hard.

You can read a different version of this story in the August/September 2010 issue of The Penn Stater magazine and an interview I did with an Icelandic scientist, and Penn State alum, on the Penn Stater blog. A third, very different take on it will appear in the May 2012 issue of Highlights for Children.

Published on February 15, 2012 11:15

Carried Away

My first book, A Good Horse Has No Color, has been out of print for several years. To celebrate its rebirth as an e-book, available in all formats from Smashwords.com and for Kindle at Amazon.com, I thought I'd start off my new blog with an excerpt. Here is the book's very brief prologue:

My first book, A Good Horse Has No Color, has been out of print for several years. To celebrate its rebirth as an e-book, available in all formats from Smashwords.com and for Kindle at Amazon.com, I thought I'd start off my new blog with an excerpt. Here is the book's very brief prologue:I could hear the horses before I saw them, their hoofbeats the high slap of cupped hands clapping, beating the punctuated four-beat rhythm of the tolt, the breed's distinctive running-walk gait. From our summerhouse, I watched them through binoculars. Pinpricks on the silvery wet sand, they shimmered like a vision out of the Icelandic Sagas, the medieval literature that had brought me to Iceland in the first place. Briefly the horses took shape as they cut across the tide flats: necks arced high, manes rippling, long tails floating behind. Their short legs curved and struck, curved and struck. I would watch them until they disappeared beyond the black headland and wonder who their riders were, where they went on their rapid journey. I wanted to go with them.

Icelandic folktales warn of the gray horse that comes out of the water, submits briefly to bridle and saddle, and at dusk carries its rider into the sea. For me, it was the watcher who was carried away.

Since publishing A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse in 2001, I've become very involved with the national breed organization, the Icelandic Horse Congress, and now co-edit their quarterly magazine. It's a very good place to learn more about these wonderful animals. To see them in action -- and to see riders crossing the sands near my old summerhouse -- visit my friend Stan Hirson's video-blog, www.hestakaup.com.

Published on February 15, 2012 08:26