Nancy Marie Brown's Blog

October 5, 2022

The (Not) Ok Glacier

In 2014 a small glacier in the center of Iceland was found to be dead.

It was not the glacier I write about in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk , whose looming presence inspired wild thoughts in me, and might have lured me to my death if I were more naïve about Icelandic nature. That was Hofsjökull.

It was not my favorite glacier, the beauty who appears, unpredictably, across 75 miles of bay from Iceland’s capital city, Reykjavik, the glacier Icelandic author Halldor Laxness called “a soul clad in air.” That glacier, Snæfellsjökull, occupies several chapters in Looking for the Hidden Folk .

The dead glacier, Ok, meaning “yoke” or “burden,” was their little brother. A white tooth on a medium-tall mountain, Ok was a landmark on an ancient road, but exceptional in Iceland only for his small size. At his greatest, Ok’s ice covered six square miles.

At his greatest, Ok’s ice covered six square miles.

Iceland’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull, covers more than 3,000 square miles.

A glacier is made when snow falls faster than it melts. At 65 feet deep, the snow starts turning to ice. At a hundred feet deep, the ice begins to creep. It flows at a rate of three feet a day downhill. Its melting edge is called its mouth. When ice breaks off into the meltwater lake, the glacier is said to calve.

A glacier that does not creep or calve is dead.

Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer heard of the death of Ok in 2016. “As cultural anthropologists”--the two work at Rice University in Houston--“we could see that people were implicated in the loss of glaciers in at least two ways,” they wrote. One: Humans were hurting the planet. Two: Humans were hurting themselves, “especially in a country like Iceland whose identity is so bound up with glaciers.”

So they made a film. Then they planned a funeral.

They asked Icelandic writer Andri Snær Magnason to design a memorial plaque. “How do you write a eulogy,” he asked, “for a symbol of eternity?” On August 18, 2019 a few dozen people climbed Ok. There was no path. They passed from moss to lichens to “jagged stones,” they slipped on ice and sank into icy puddles. It was a harder climb than many had expected. The wind bit. It took three hours.

On August 18, 2019 a few dozen people climbed Ok. There was no path. They passed from moss to lichens to “jagged stones,” they slipped on ice and sank into icy puddles. It was a harder climb than many had expected. The wind bit. It took three hours.

They were asked to hike in silence, not looking back, as if they were hiking up Helgafell, a small hill I frequently climb in West Iceland whose name means Holy Mountain and whose legend says surmounting it silently, without looking back, will grant you three wishes.

At the top of Ok, the hikers read out the glacier’s death certificate. Cause of death? “Excessive heat” and “humans.” They affixed the bronze plaque to a rock; addressed to the future, it says, “Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Then they began to sing.

The funeral, Howe and Boyer wrote in Anthropology News, “was a media event covered in nearly every country in the world.” The story of Ok “seems to have humanized climate change for a lot of people. It put a face and a name to an abstract problem.”

In 1992 I attended a lecture by Gillian Overing, then an English professor at Wake Forest University, during the International Medieval Congress in Kalamazoo, Michigan. In Iceland, Overing noted, the center is the margin. Geography is inside-out. People settle on the temperate edges of the island, while its interior is a glacial desert, cold, inhospitable, and not even crossable most of the year. “What kind of self,” she mused, “might these places reflect?” What kind of self has wilderness at its heart?

That question, that concept, in large part, inspired my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth . But now, with the death of Ok, a new question arises: What happens to the self when the wilderness in its heart is dead?

But now, with the death of Ok, a new question arises: What happens to the self when the wilderness in its heart is dead?

“Help us,” wrote Iceland’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, in The New York Times, “keep the ice in Iceland.”

We no longer even know how to talk about nature, writes George Monbiot in The Guardian. We use terms that are “cold and alienating,” like reserve. “Think of what we mean when we use that word about a person,” he says. The word environment “creates no pictures in the mind.” Calling plants or animals “resources” or “stocks” implies “they belong to us and their role is to serve us.” Language has power, Monbiot reminds us. “Those who name it own it,” he argues, concluding: “We need new words.”

Or, perhaps, a new look at some very old ones, like elf.

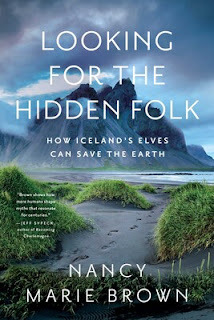

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth was published October 4 by Pegasus Books. Order it at your favorite bookshop, through Simon & Schuster distributors, or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Thanks!

For another artist's response to the funeral for Ok glacier, see this news release from Rice University.

It was not the glacier I write about in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk , whose looming presence inspired wild thoughts in me, and might have lured me to my death if I were more naïve about Icelandic nature. That was Hofsjökull.

It was not my favorite glacier, the beauty who appears, unpredictably, across 75 miles of bay from Iceland’s capital city, Reykjavik, the glacier Icelandic author Halldor Laxness called “a soul clad in air.” That glacier, Snæfellsjökull, occupies several chapters in Looking for the Hidden Folk .

The dead glacier, Ok, meaning “yoke” or “burden,” was their little brother. A white tooth on a medium-tall mountain, Ok was a landmark on an ancient road, but exceptional in Iceland only for his small size.

At his greatest, Ok’s ice covered six square miles.

At his greatest, Ok’s ice covered six square miles. Iceland’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull, covers more than 3,000 square miles.

A glacier is made when snow falls faster than it melts. At 65 feet deep, the snow starts turning to ice. At a hundred feet deep, the ice begins to creep. It flows at a rate of three feet a day downhill. Its melting edge is called its mouth. When ice breaks off into the meltwater lake, the glacier is said to calve.

A glacier that does not creep or calve is dead.

Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer heard of the death of Ok in 2016. “As cultural anthropologists”--the two work at Rice University in Houston--“we could see that people were implicated in the loss of glaciers in at least two ways,” they wrote. One: Humans were hurting the planet. Two: Humans were hurting themselves, “especially in a country like Iceland whose identity is so bound up with glaciers.”

So they made a film. Then they planned a funeral.

They asked Icelandic writer Andri Snær Magnason to design a memorial plaque. “How do you write a eulogy,” he asked, “for a symbol of eternity?”

On August 18, 2019 a few dozen people climbed Ok. There was no path. They passed from moss to lichens to “jagged stones,” they slipped on ice and sank into icy puddles. It was a harder climb than many had expected. The wind bit. It took three hours.

On August 18, 2019 a few dozen people climbed Ok. There was no path. They passed from moss to lichens to “jagged stones,” they slipped on ice and sank into icy puddles. It was a harder climb than many had expected. The wind bit. It took three hours. They were asked to hike in silence, not looking back, as if they were hiking up Helgafell, a small hill I frequently climb in West Iceland whose name means Holy Mountain and whose legend says surmounting it silently, without looking back, will grant you three wishes.

At the top of Ok, the hikers read out the glacier’s death certificate. Cause of death? “Excessive heat” and “humans.” They affixed the bronze plaque to a rock; addressed to the future, it says, “Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Then they began to sing.

The funeral, Howe and Boyer wrote in Anthropology News, “was a media event covered in nearly every country in the world.” The story of Ok “seems to have humanized climate change for a lot of people. It put a face and a name to an abstract problem.”

In 1992 I attended a lecture by Gillian Overing, then an English professor at Wake Forest University, during the International Medieval Congress in Kalamazoo, Michigan. In Iceland, Overing noted, the center is the margin. Geography is inside-out. People settle on the temperate edges of the island, while its interior is a glacial desert, cold, inhospitable, and not even crossable most of the year. “What kind of self,” she mused, “might these places reflect?” What kind of self has wilderness at its heart?

That question, that concept, in large part, inspired my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth .

But now, with the death of Ok, a new question arises: What happens to the self when the wilderness in its heart is dead?

But now, with the death of Ok, a new question arises: What happens to the self when the wilderness in its heart is dead? “Help us,” wrote Iceland’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, in The New York Times, “keep the ice in Iceland.”

We no longer even know how to talk about nature, writes George Monbiot in The Guardian. We use terms that are “cold and alienating,” like reserve. “Think of what we mean when we use that word about a person,” he says. The word environment “creates no pictures in the mind.” Calling plants or animals “resources” or “stocks” implies “they belong to us and their role is to serve us.” Language has power, Monbiot reminds us. “Those who name it own it,” he argues, concluding: “We need new words.”

Or, perhaps, a new look at some very old ones, like elf.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth was published October 4 by Pegasus Books. Order it at your favorite bookshop, through Simon & Schuster distributors, or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Thanks!

For another artist's response to the funeral for Ok glacier, see this news release from Rice University.

Published on October 05, 2022 08:19

September 21, 2022

Writing for Iceland

Interviewing me about my new book,

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

, a reporter asked, Did you write it for an Icelandic audience, or for an American one?

Um ... yes.

Of course, my main audience is the much larger American one. I fell in love with Iceland (population 365,000) on my first visit, in 1986, and much of my writing since then has been aimed at sharing my love for Iceland's landscape and culture with people who haven't (yet) visited this amazing island in the north Atlantic. (In 1986, Iceland was not on everyone's bucket list, as it seems to be today.)

But it is also very important to me that the Icelanders I am writing about like my books--or at least see them as being fair. It makes me very happy, for instance, to know that the families featured in my first book,

A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse

, are always glad to have me visit. This summer, 25 years after I bought a horse from them, I spent a week with Fjóla and Elvar of the farm Syðra-Skörðugil in north Iceland; we laughed at how naive I'd been about horses then, and reminisced over how well things had turned out.

It makes me very happy, for instance, to know that the families featured in my first book,

A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse

, are always glad to have me visit. This summer, 25 years after I bought a horse from them, I spent a week with Fjóla and Elvar of the farm Syðra-Skörðugil in north Iceland; we laughed at how naive I'd been about horses then, and reminisced over how well things had turned out.

So when my book about Iceland's elves, Looking for the Hidden Folk , was sent to a group of Icelandic writers and scholars for review, pre-publication, I was anxious that they would also think I was being fair to their ancient culture.

I needn't have worried.

Wrote Egill Bjarnason, author of How Iceland Changed the World: The Big History of a Small Island : "Nancy Marie Brown reveals to us skeptics how rocks and hills are the mansions of elves, or at least what it takes to believe so. Looking for the Hidden Folk evocatively animates the Icelandic landscape through Brown's past and present travels and busts some prevalent clichés and myths along the way--this book is my reply to the next foreign reporter asking about that Elf Lobby."

Terry Gunnell, a professor of folkloristics at the University of Iceland, whose work on elf-lore is heavily cited in the book, called it "A love song to the living landscape of Iceland and the cultural history in which it is clothed, inspired by the author's numerous encounters with the country and its people over the last decades."

Ármann Jakobsson, a professor in the department of Icelandic at the University of Iceland, and author of the fascinating book The Troll Inside You , also understood what I was trying to say. He wrote: " Looking for the Hidden Folk is an elegantly written and wonderfully individualistic exploration of Icelandic culture through the ages, combining a shrewd appraisal of traditions with an acute interest in the modern world and all its intellectual quirks." Gísli Sigurðsson, a research professor at The Árni Magnússon Institute of the University of Iceland, agreed. He wrote: "Using ideas and stories about the hidden folk in Iceland as a stepping stone into the human perception of our homes in the world where stories and memories breathe life into places, be it through the vocabulary of quantum physics or folklore, Nancy Marie Brown makes us realize that there is always more to the world than meets the eye. And that world is not there for us to conquer and exploit but to walk into and sense the dew with our bare feet on the soft moss, beside breathing horses and mighty glaciers in the drifting fog that often blocks our view."

Gísli Sigurðsson, a research professor at The Árni Magnússon Institute of the University of Iceland, agreed. He wrote: "Using ideas and stories about the hidden folk in Iceland as a stepping stone into the human perception of our homes in the world where stories and memories breathe life into places, be it through the vocabulary of quantum physics or folklore, Nancy Marie Brown makes us realize that there is always more to the world than meets the eye. And that world is not there for us to conquer and exploit but to walk into and sense the dew with our bare feet on the soft moss, beside breathing horses and mighty glaciers in the drifting fog that often blocks our view."

And finally, my friend Gísli Pálsson, professor of anthropology at the university of Iceland, seems to always know how to sum up my books just so. He wrote: "This is a sweeping and moving journey across time and space—through myth and theory, language, and literature—into the world of wonder and enchantment. Beautifully written, Looking for the Hidden Folk offers a compelling and surprising case for the recognition of forces and beings not necessarily 'seen' in everyday life but nevertheless somehow sensed, exploring their complexity and why they matter."

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Um ... yes.

Of course, my main audience is the much larger American one. I fell in love with Iceland (population 365,000) on my first visit, in 1986, and much of my writing since then has been aimed at sharing my love for Iceland's landscape and culture with people who haven't (yet) visited this amazing island in the north Atlantic. (In 1986, Iceland was not on everyone's bucket list, as it seems to be today.)

But it is also very important to me that the Icelanders I am writing about like my books--or at least see them as being fair.

It makes me very happy, for instance, to know that the families featured in my first book,

A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse

, are always glad to have me visit. This summer, 25 years after I bought a horse from them, I spent a week with Fjóla and Elvar of the farm Syðra-Skörðugil in north Iceland; we laughed at how naive I'd been about horses then, and reminisced over how well things had turned out.

It makes me very happy, for instance, to know that the families featured in my first book,

A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse

, are always glad to have me visit. This summer, 25 years after I bought a horse from them, I spent a week with Fjóla and Elvar of the farm Syðra-Skörðugil in north Iceland; we laughed at how naive I'd been about horses then, and reminisced over how well things had turned out. So when my book about Iceland's elves, Looking for the Hidden Folk , was sent to a group of Icelandic writers and scholars for review, pre-publication, I was anxious that they would also think I was being fair to their ancient culture.

I needn't have worried.

Wrote Egill Bjarnason, author of How Iceland Changed the World: The Big History of a Small Island : "Nancy Marie Brown reveals to us skeptics how rocks and hills are the mansions of elves, or at least what it takes to believe so. Looking for the Hidden Folk evocatively animates the Icelandic landscape through Brown's past and present travels and busts some prevalent clichés and myths along the way--this book is my reply to the next foreign reporter asking about that Elf Lobby."

Terry Gunnell, a professor of folkloristics at the University of Iceland, whose work on elf-lore is heavily cited in the book, called it "A love song to the living landscape of Iceland and the cultural history in which it is clothed, inspired by the author's numerous encounters with the country and its people over the last decades."

Ármann Jakobsson, a professor in the department of Icelandic at the University of Iceland, and author of the fascinating book The Troll Inside You , also understood what I was trying to say. He wrote: " Looking for the Hidden Folk is an elegantly written and wonderfully individualistic exploration of Icelandic culture through the ages, combining a shrewd appraisal of traditions with an acute interest in the modern world and all its intellectual quirks."

Gísli Sigurðsson, a research professor at The Árni Magnússon Institute of the University of Iceland, agreed. He wrote: "Using ideas and stories about the hidden folk in Iceland as a stepping stone into the human perception of our homes in the world where stories and memories breathe life into places, be it through the vocabulary of quantum physics or folklore, Nancy Marie Brown makes us realize that there is always more to the world than meets the eye. And that world is not there for us to conquer and exploit but to walk into and sense the dew with our bare feet on the soft moss, beside breathing horses and mighty glaciers in the drifting fog that often blocks our view."

Gísli Sigurðsson, a research professor at The Árni Magnússon Institute of the University of Iceland, agreed. He wrote: "Using ideas and stories about the hidden folk in Iceland as a stepping stone into the human perception of our homes in the world where stories and memories breathe life into places, be it through the vocabulary of quantum physics or folklore, Nancy Marie Brown makes us realize that there is always more to the world than meets the eye. And that world is not there for us to conquer and exploit but to walk into and sense the dew with our bare feet on the soft moss, beside breathing horses and mighty glaciers in the drifting fog that often blocks our view." And finally, my friend Gísli Pálsson, professor of anthropology at the university of Iceland, seems to always know how to sum up my books just so. He wrote: "This is a sweeping and moving journey across time and space—through myth and theory, language, and literature—into the world of wonder and enchantment. Beautifully written, Looking for the Hidden Folk offers a compelling and surprising case for the recognition of forces and beings not necessarily 'seen' in everyday life but nevertheless somehow sensed, exploring their complexity and why they matter."

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Published on September 21, 2022 08:00

September 14, 2022

What Does It Mean to Believe in Elves?

Icelanders believe in elves. There are many ways you could take issue with that sentence, but let's start with that shapeshifting verb, “to believe.”

We believe in elves, we believe in gravity, we believe in science, we believe in God. Does anyone really know what it means to believe?

As I note in my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, anthropologists like himself, Rodney Needham wrote in 1972, “appear to take it for granted that ‘belief’ is a word of as little ambiguity as ‘spear’ or ‘cow’” when they write about the beliefs of this culture or that.

Yet “belief” is kaleidoscopic. It translates a “bewildering variety” of foreign terms. Its root means to love or desire. Translators of the Bible used it to translate trust or obey. It means to follow a religion, to accept a statement as true, or to hold an opinion. You can say, “I believe I’ll have fish for dinner” as easily as “I believe in elves” or “I believe in God.”

Philosopher David Hume in 1739 defined belief as “something felt by the mind, which distinguishes the ideas of the judgment from the fictions of the imagination.”

Stuart Hampshire in 1959 defined a man’s beliefs as “the generally unchanging background to his active thought,” those things he “never had occasion to question” or to state.

Jonathan Lanman in 2008 defined belief as “the state of a cognitive system holding information (not necessarily in the propositional or explicit form) as true in the generation of further thought and behavior.” Using this definition, Lanman asserted, we can “pursue a cross-cultural science of belief,” as everyone has such beliefs. “All have cognitive systems that represent the world in some way and act according to what they believe to be true about that world.”

Your beliefs define you. As fuzzy, illogical, or unquestioned as they may be, they control how you see the world and how you act in response.

As Needham concluded, “An assertion of belief is a report about the person who makes it, and not intrinsically or primarily about objective matters of truth or fact.” Belief, said Needham, is “ultimately a reference to an inner state.” More, that inner state seems to be emotional. Yet we cannot say, in English at least, that someone is “believing” or “belief-full,” Needham mused.

Philosopher Jesse Prinz thinks the emotion involved is wonder. It’s wonder that produces both religion and science, as well as art: The three institutions “that are most central to our humanity,” said Prinz, are “united in wonder.” They are not in conflict. They are not either/or. Each of the three feeds “the appetite that wonder excites in us,” says Prinz. Each allows us “to transcend our animality by transporting us to hidden worlds.” It’s wonder, Prinz argues, that makes us human.

Adam Smith, the inventor of capitalism, wondered about wonder in 1795, Prinz found. “He wrote that wonder arises ‘when something quite new and singular is presented … [and] memory cannot, from all its stores, cast up any image that nearly resembles this strange appearance.’”

What is it like? the brain asks. Like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

Wonder is sensory: “We stare and widen our eyes,” wrote Prinz. Wonder is cognitive: “Such things are perplexing because we cannot rely on past experience to comprehend them … : We gasp and say ‘Wow!’” And then there is “a dimension that can be described as spiritual.” Wonder, concludes Prinz, awakens us. “We don’t just take the world for granted, we’re struck by it.”

Or we are not. Emotions, brain researchers have found, depend on culture. You will not sense wonder if you’re never exposed to it.

There’s much we don’t know about the brain. But we know it categorizes. We know it uses concepts and words, finds causes and crafts stories. We know it constantly simulates the world and makes multiple predictions of what we will sense and see—and what we should do in response.

We know that it’s wired for emotion, for wonder, for ecstasy, but that Western culture disdains and derides this side of the brain. We’re taught to control our emotions, to give up wonder in childhood, to stifle our mystical experiences—or at least not to talk about them. Otherwise we’ll be thought “ignorant, eccentric, or unwell,” says Jules Evans of the Centre for the History of the Emotions in London.

We’ll be laughed at as loony elf-seers.

But without words, without the concepts to describe them, you are “experientially blind,” says psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett. Wonders—elves?—may be all around you, but you will not see them.

Which brings up the next question I grapple with in Looking for the Hidden Folk, What immaterial beings are we allowed to believe in, and who is allowed to do the believing?

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

We believe in elves, we believe in gravity, we believe in science, we believe in God. Does anyone really know what it means to believe?

As I note in my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, anthropologists like himself, Rodney Needham wrote in 1972, “appear to take it for granted that ‘belief’ is a word of as little ambiguity as ‘spear’ or ‘cow’” when they write about the beliefs of this culture or that.

Yet “belief” is kaleidoscopic. It translates a “bewildering variety” of foreign terms. Its root means to love or desire. Translators of the Bible used it to translate trust or obey. It means to follow a religion, to accept a statement as true, or to hold an opinion. You can say, “I believe I’ll have fish for dinner” as easily as “I believe in elves” or “I believe in God.”

Philosopher David Hume in 1739 defined belief as “something felt by the mind, which distinguishes the ideas of the judgment from the fictions of the imagination.”

Stuart Hampshire in 1959 defined a man’s beliefs as “the generally unchanging background to his active thought,” those things he “never had occasion to question” or to state.

Jonathan Lanman in 2008 defined belief as “the state of a cognitive system holding information (not necessarily in the propositional or explicit form) as true in the generation of further thought and behavior.” Using this definition, Lanman asserted, we can “pursue a cross-cultural science of belief,” as everyone has such beliefs. “All have cognitive systems that represent the world in some way and act according to what they believe to be true about that world.”

Your beliefs define you. As fuzzy, illogical, or unquestioned as they may be, they control how you see the world and how you act in response.

As Needham concluded, “An assertion of belief is a report about the person who makes it, and not intrinsically or primarily about objective matters of truth or fact.” Belief, said Needham, is “ultimately a reference to an inner state.” More, that inner state seems to be emotional. Yet we cannot say, in English at least, that someone is “believing” or “belief-full,” Needham mused.

Philosopher Jesse Prinz thinks the emotion involved is wonder. It’s wonder that produces both religion and science, as well as art: The three institutions “that are most central to our humanity,” said Prinz, are “united in wonder.” They are not in conflict. They are not either/or. Each of the three feeds “the appetite that wonder excites in us,” says Prinz. Each allows us “to transcend our animality by transporting us to hidden worlds.” It’s wonder, Prinz argues, that makes us human.

Adam Smith, the inventor of capitalism, wondered about wonder in 1795, Prinz found. “He wrote that wonder arises ‘when something quite new and singular is presented … [and] memory cannot, from all its stores, cast up any image that nearly resembles this strange appearance.’”

What is it like? the brain asks. Like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

Wonder is sensory: “We stare and widen our eyes,” wrote Prinz. Wonder is cognitive: “Such things are perplexing because we cannot rely on past experience to comprehend them … : We gasp and say ‘Wow!’” And then there is “a dimension that can be described as spiritual.” Wonder, concludes Prinz, awakens us. “We don’t just take the world for granted, we’re struck by it.”

Or we are not. Emotions, brain researchers have found, depend on culture. You will not sense wonder if you’re never exposed to it.

There’s much we don’t know about the brain. But we know it categorizes. We know it uses concepts and words, finds causes and crafts stories. We know it constantly simulates the world and makes multiple predictions of what we will sense and see—and what we should do in response.

We know that it’s wired for emotion, for wonder, for ecstasy, but that Western culture disdains and derides this side of the brain. We’re taught to control our emotions, to give up wonder in childhood, to stifle our mystical experiences—or at least not to talk about them. Otherwise we’ll be thought “ignorant, eccentric, or unwell,” says Jules Evans of the Centre for the History of the Emotions in London.

We’ll be laughed at as loony elf-seers.

But without words, without the concepts to describe them, you are “experientially blind,” says psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett. Wonders—elves?—may be all around you, but you will not see them.

Which brings up the next question I grapple with in Looking for the Hidden Folk, What immaterial beings are we allowed to believe in, and who is allowed to do the believing?

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Published on September 14, 2022 08:00

September 7, 2022

Icelandic Bliss

In a way, my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth, is about the power of stories. We all tell stories. We always have. But we don’t always take responsibility for the effects of our storytelling. Stories shape how you see the world. They determine not only how you think of elves, but also how you think of such “real” things as mountains—or creeping thyme.

“When we look at a landscape,” writes Robert Macfarlane in Mountains of the Mind, “we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there. … We read landscapes, in other words, we interpret their forms in the light of our own experience and memory, and that of our shared cultural memory. … What we call a mountain is thus in fact a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind.”

“When we look at a landscape,” writes Robert Macfarlane in Mountains of the Mind, “we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there. … We read landscapes, in other words, we interpret their forms in the light of our own experience and memory, and that of our shared cultural memory. … What we call a mountain is thus in fact a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind.”

A story that cast a magic spell upon all mountains was Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Burke, from Ireland, published it in 1757, when he was twenty-eight. He was, writes Macfarlane, “interested in our psychic response to things—a rushing cataract, say, a dark vault or a cliff face—that seized, terrified, and yet also somehow pleased the mind by dint of being too big, too high, too fast, too obscured, too powerful, too something, to be properly comprehended.” Instead, such things inspired “a heady blend of pleasure and terror. Beauty, by contrast, was inspired by the visually regular, the proportioned, the predictable.” It’s the frisson of fear that makes a Icelandic volcano, or a cliffside swathed in fog, sublime. Burke’s book, says Macfarlane, “provided a new lens through which wilderness could be viewed and appreciated.” Macfarlane’s own books do much the same for me. In The Old Ways, he mentions an archaeologist named Anne Campbell who was “close-mapping” a moor. Why that moor? “It is the most interesting place in the world to me,” she told Macfarlane. “So I spend most of my time walking shieling tracks, paths, and the streams and the walls that used to divide up the land. Then I talk to people and try to fix their memories to those particular places.”

Burke’s book, says Macfarlane, “provided a new lens through which wilderness could be viewed and appreciated.” Macfarlane’s own books do much the same for me. In The Old Ways, he mentions an archaeologist named Anne Campbell who was “close-mapping” a moor. Why that moor? “It is the most interesting place in the world to me,” she told Macfarlane. “So I spend most of my time walking shieling tracks, paths, and the streams and the walls that used to divide up the land. Then I talk to people and try to fix their memories to those particular places.”

I once visited that part of Scotland, the western edge of the Isle of Lewis, but did not meet Campbell walking her moor. Still, a story Macfarlane told, a little aside, gave me a new perspective on Iceland (the most interesting place in the world to me). Macfarlane wrote, “When it wasn’t too cold, and not so dry that the heather was sharp, Anne liked to walk barefoot on the moor. ‘It takes about two weeks to get your feet toughened up so that it’s no discomfort. And then it’s bliss.’ You should try it when you’re out there. Take those big boots of yours off!’” On the western tip of Iceland’s Snaefellsnes peninsula sits the long-abandoned farm of Laugarbrekka, where Gudrid the Far-Traveler was born in about 982. I’ve written two books about Gudrid, sister-in-law to Leif Eiriksson, the Viking explorer credited with discovering America some five hundred years before Columbus. Yet Gudrid spent more time in the New World than Leif did. Gudrid is the real Viking explorer, and a recurring inspiration to me. In 2016, on a sunny Sunday in late July, I visited her monument at Laugarbrekka for the umpteenth time. I walked out to the laug or bathing pool, which is no longer bathwater warm, took off my boots, rolled up my pants, and waded in, but the sharp stony bottom of the lake kept me from going far.

On the western tip of Iceland’s Snaefellsnes peninsula sits the long-abandoned farm of Laugarbrekka, where Gudrid the Far-Traveler was born in about 982. I’ve written two books about Gudrid, sister-in-law to Leif Eiriksson, the Viking explorer credited with discovering America some five hundred years before Columbus. Yet Gudrid spent more time in the New World than Leif did. Gudrid is the real Viking explorer, and a recurring inspiration to me. In 2016, on a sunny Sunday in late July, I visited her monument at Laugarbrekka for the umpteenth time. I walked out to the laug or bathing pool, which is no longer bathwater warm, took off my boots, rolled up my pants, and waded in, but the sharp stony bottom of the lake kept me from going far.

Back on the bank, I dabbled my toes and gazed at the glacier-capped volcano, Snaefellsjokull, its corruscations of lava catching the light, until it was time to go, then, remembering Campbell’s bliss, decided to walk barefoot back to the car. It was lovely. The heath was springy and soft and comforting to my feet—though they were not even toughened up. Picking along, carefully placing each foot, I found ripe crowberries and almost ripe blueberries, some very blue but still tart. The grass was soft, too, but I found myself preferentially stepping on the berry bushes and fragrant creeping thyme, which tickled. Who would have thought that thyme (not time) equaled bliss? You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

“When we look at a landscape,” writes Robert Macfarlane in Mountains of the Mind, “we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there. … We read landscapes, in other words, we interpret their forms in the light of our own experience and memory, and that of our shared cultural memory. … What we call a mountain is thus in fact a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind.”

“When we look at a landscape,” writes Robert Macfarlane in Mountains of the Mind, “we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there. … We read landscapes, in other words, we interpret their forms in the light of our own experience and memory, and that of our shared cultural memory. … What we call a mountain is thus in fact a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind.” A story that cast a magic spell upon all mountains was Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Burke, from Ireland, published it in 1757, when he was twenty-eight. He was, writes Macfarlane, “interested in our psychic response to things—a rushing cataract, say, a dark vault or a cliff face—that seized, terrified, and yet also somehow pleased the mind by dint of being too big, too high, too fast, too obscured, too powerful, too something, to be properly comprehended.” Instead, such things inspired “a heady blend of pleasure and terror. Beauty, by contrast, was inspired by the visually regular, the proportioned, the predictable.” It’s the frisson of fear that makes a Icelandic volcano, or a cliffside swathed in fog, sublime.

Burke’s book, says Macfarlane, “provided a new lens through which wilderness could be viewed and appreciated.” Macfarlane’s own books do much the same for me. In The Old Ways, he mentions an archaeologist named Anne Campbell who was “close-mapping” a moor. Why that moor? “It is the most interesting place in the world to me,” she told Macfarlane. “So I spend most of my time walking shieling tracks, paths, and the streams and the walls that used to divide up the land. Then I talk to people and try to fix their memories to those particular places.”

Burke’s book, says Macfarlane, “provided a new lens through which wilderness could be viewed and appreciated.” Macfarlane’s own books do much the same for me. In The Old Ways, he mentions an archaeologist named Anne Campbell who was “close-mapping” a moor. Why that moor? “It is the most interesting place in the world to me,” she told Macfarlane. “So I spend most of my time walking shieling tracks, paths, and the streams and the walls that used to divide up the land. Then I talk to people and try to fix their memories to those particular places.” I once visited that part of Scotland, the western edge of the Isle of Lewis, but did not meet Campbell walking her moor. Still, a story Macfarlane told, a little aside, gave me a new perspective on Iceland (the most interesting place in the world to me). Macfarlane wrote, “When it wasn’t too cold, and not so dry that the heather was sharp, Anne liked to walk barefoot on the moor. ‘It takes about two weeks to get your feet toughened up so that it’s no discomfort. And then it’s bliss.’ You should try it when you’re out there. Take those big boots of yours off!’”

On the western tip of Iceland’s Snaefellsnes peninsula sits the long-abandoned farm of Laugarbrekka, where Gudrid the Far-Traveler was born in about 982. I’ve written two books about Gudrid, sister-in-law to Leif Eiriksson, the Viking explorer credited with discovering America some five hundred years before Columbus. Yet Gudrid spent more time in the New World than Leif did. Gudrid is the real Viking explorer, and a recurring inspiration to me. In 2016, on a sunny Sunday in late July, I visited her monument at Laugarbrekka for the umpteenth time. I walked out to the laug or bathing pool, which is no longer bathwater warm, took off my boots, rolled up my pants, and waded in, but the sharp stony bottom of the lake kept me from going far.

On the western tip of Iceland’s Snaefellsnes peninsula sits the long-abandoned farm of Laugarbrekka, where Gudrid the Far-Traveler was born in about 982. I’ve written two books about Gudrid, sister-in-law to Leif Eiriksson, the Viking explorer credited with discovering America some five hundred years before Columbus. Yet Gudrid spent more time in the New World than Leif did. Gudrid is the real Viking explorer, and a recurring inspiration to me. In 2016, on a sunny Sunday in late July, I visited her monument at Laugarbrekka for the umpteenth time. I walked out to the laug or bathing pool, which is no longer bathwater warm, took off my boots, rolled up my pants, and waded in, but the sharp stony bottom of the lake kept me from going far. Back on the bank, I dabbled my toes and gazed at the glacier-capped volcano, Snaefellsjokull, its corruscations of lava catching the light, until it was time to go, then, remembering Campbell’s bliss, decided to walk barefoot back to the car. It was lovely. The heath was springy and soft and comforting to my feet—though they were not even toughened up. Picking along, carefully placing each foot, I found ripe crowberries and almost ripe blueberries, some very blue but still tart. The grass was soft, too, but I found myself preferentially stepping on the berry bushes and fragrant creeping thyme, which tickled. Who would have thought that thyme (not time) equaled bliss?

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Published on September 07, 2022 08:00

August 24, 2022

The Remarkable Moníka of Merkigil

The farm of Merkigil in Skagafjörður, north Iceland, is famous for two reasons: 1) the treacherous gorge you had to cross to get there, before the glacial river beside the farm was bridged in 1961; and 2) the grand, two-story concrete house built by the widow Moníka with the help of her daughters—years before the river was bridged.

The farm of Merkigil in Skagafjörður, north Iceland, is famous for two reasons: 1) the treacherous gorge you had to cross to get there, before the glacial river beside the farm was bridged in 1961; and 2) the grand, two-story concrete house built by the widow Moníka with the help of her daughters—years before the river was bridged. This August, I rode a horse to Merkigil and stayed in Moníka’s house. The trip was organized by my friends Fjóla and Elvar from Syðra-Skörðugil (from whom I bought my first Icelandic horse 25 years ago, as you can read in A Good Horse Has No Color ). A few months before, on Fjóla’s recommendation, I bought and read Moníka’s biography, Konan í Dalnum og Dæturnar Sjö (The Woman in the Valley and her Seven Daughters) by Guðmundur G. Hagalin. There I learned these things about Moníka’s remarkable life:

In 1924, Moníka was working in a fish factory in Reykjavík when she received a letter. We would call it a love letter. She wasn’t so sure.

Moníka was then 23, the seventh child of 10 from the little farm of Ánastaðir in Skagafjörður, north Iceland. She was small, sturdy, and powerful, and known as a hard worker. At the young age of 11, she had left home to go to work, spinning, milking, making hay, and caring for animals, children, and old folks at various farms in the district, where she earned a reputation as a young woman you could count on. Then she had followed her two sisters to Reykjavík, where their uncle was foreman at a fish factory, and joined thirty-some other women cleaning and salting fish; her record was 3,000 fish in a day—she found it boring to not work as hard as she could. But she also liked having her evenings free, when the work day was over, and having money in her pocket to buy pretty clothes and enjoy the city, plus more put aside to bring home to her family when she visited them, as she was planning to do that summer.

Then she got the letter. When she was 11, her very first summer away from home, she had worked at haymaking with a boy named Johannes; he was about 14. The two of them had been sent off to a nearby farm his father had leased and told to hay it; they cut the grass with a scythe, raked it until it was dry, bagged it up into bales, and transported home 40 horse-loads of fine hay.

Never have I forgotten that summer we made hay, the letter read. It was from Johannes. He and his parents now owned half of a farm named Merkigil, deep in one of the valleys of Skagafjörður. His mother was ill, he said, and he wondered if Moníka could come to Merkigil and take charge of the household.

Moníka, too, remembered their hay-making. She had become quite fond of Johannes, who was funny and easy-going and hard-working; she recalled how quiet it was in the evenings, as they walked home side by side, satisfied with their day’s accomplishments. What is he really asking me, she wondered. She put off replying to his letter until, finally, it seemed pointless to do so: He must have found someone else by now, she thought.

Moníka, too, remembered their hay-making. She had become quite fond of Johannes, who was funny and easy-going and hard-working; she recalled how quiet it was in the evenings, as they walked home side by side, satisfied with their day’s accomplishments. What is he really asking me, she wondered. She put off replying to his letter until, finally, it seemed pointless to do so: He must have found someone else by now, she thought. She took the boat home, where she immediately ran into a neighbor who said, If you were a man, I’d have a job for you.

And what job, Moníka asked, do you have that only a man can do?

He needed someone to cut, dry, bale, and transport seventy horse-loads of hay, and he was willing to pay well.

I’ll do it, she said. And she did. She visited her parents for a few days, then took a tent, went up to the hayfield with a scythe and a rake, and started making hay. It took her five weeks.

When the haymaking was over, she packed up her things and prepared to return to Reykjavík. But the boat was late, and she had to wait several days in the harbor town. While she was there, she was accosted by a man named Gísli, who had been searching all over for her, he said. He had a job that only she could do. He needed someone who could work hard, both inside the house and on the farm, and who was also a good nurse, for there was an old, sick couple who desperately needed help. His sister was with them now, but she couldn’t stay.

When the haymaking was over, she packed up her things and prepared to return to Reykjavík. But the boat was late, and she had to wait several days in the harbor town. While she was there, she was accosted by a man named Gísli, who had been searching all over for her, he said. He had a job that only she could do. He needed someone who could work hard, both inside the house and on the farm, and who was also a good nurse, for there was an old, sick couple who desperately needed help. His sister was with them now, but she couldn’t stay. And where is this farm? Moníka asked, and was startled when he replied: Merkigil. Almost in spite of herself, she found herself saying yes. Gísli gave her no time to change her mind. He had four strong horses with him, and they set off at once to ride the 50 miles to Merkigil. Late in the evening, they reached the treacherous gorge.

You’re not afraid of heights, I hope, Gísli said.

Of course not, said Moníka, though she paused on the brink of the cliff, and looked down into the deep, dark gorge, its bottom hidden in the shadows. They got off their horses and led them down the switchbacked trail, which was snow-covered and a little icy in places, herding their two extra horses ahead of them. They crossed the rocky stream at the bottom, and climbed up the steep slope on the other side.

Caption: In 2022, I crossed the Merkigil gorge in the opposite direction, on a brilliant summer day. It was still scary. Here we are on the brink, watching our loose horses climb the opposite wall of the canyon.

Caption: The gorge stretching out below us as we climb and climb.

Caption: The gorge stretching out below us as we climb and climb.

Caption: I got an assist from the tail ahead of me.

Caption: I got an assist from the tail ahead of me.

Caption: Finally we reached the top.

Caption: Finally we reached the top.

A short ride ahead was a cluster of buildings with grass roofs: the barns and houses of Merkigil. Gísli’s sister was delighted to see him and Moníka, when they arrived that night in 1924. She introduced Moníka to 93-year-old Sigurbjörg, who was bed-ridden, and her slightly more vigorous husband, Egill. Then she took Moníka next door to the main living room, where she would sleep. There she was greeted by Johannes and his father, and by Johannes’s mother, who was also bed-ridden. So you have come, she said, thank heavens.

A short ride ahead was a cluster of buildings with grass roofs: the barns and houses of Merkigil. Gísli’s sister was delighted to see him and Moníka, when they arrived that night in 1924. She introduced Moníka to 93-year-old Sigurbjörg, who was bed-ridden, and her slightly more vigorous husband, Egill. Then she took Moníka next door to the main living room, where she would sleep. There she was greeted by Johannes and his father, and by Johannes’s mother, who was also bed-ridden. So you have come, she said, thank heavens. No one said anything about Johannes’s letter, but two years later he and Moníka married. They had eight children—seven daughters and one son—and then, in 1944, Johannes died of cancer. By then, the whole farm was theirs, and the loans were all paid off. They had three milk cows, some steers, 200 sheep, eight riding horses, three breeding horses, and some untrained foals. The fields were in good shape and well-fenced. Moníka decided to stay and run Merkigil with her children.

Her oldest daughter, Elín, was then 19; she took charge of the sheep. She and her sister Margrét, 17, also did the haymaking, when recurring stomach pains kept Moníka from doing it. They were helped by Jóhanna, 16, and Guðrún, 14. All went well, in general—except when sheep got lost in the fog and horses fell into the canyon and had to be rescued.

Moníka’s biggest aggravation was that the house, a traditional wooden frame clad with turf blocks, was falling down around their ears. Turf houses need a lot of maintenance, and the work is heavy and takes some skill. With the help of neighbors, she cut and dried new turf and repaired the walls as best they could, but by 1948 Moníka had decided it was time to build a modern, concrete house.

Moníka’s biggest aggravation was that the house, a traditional wooden frame clad with turf blocks, was falling down around their ears. Turf houses need a lot of maintenance, and the work is heavy and takes some skill. With the help of neighbors, she cut and dried new turf and repaired the walls as best they could, but by 1948 Moníka had decided it was time to build a modern, concrete house. The house she designed was two stories tall, with high ceilings and wide windows. She took out a loan, hired a team of housebuilders, and bought building materials, having them trucked as far as the road went, past the neighboring farm of Gilsbakki. Then she and her daughters loaded everything onto horseback—wood for the concrete forms, roofing panels, window glass, doors, a kitchen stove, a bathtub—and conveyed them down the switchbacked trail into Merkigil gorge and up again to the new house site.

The hardest thing to carry was the cement mixer, but Moníka’s daughters were determined to figure out a way—otherwise, they knew, they’d be the ones mixing the cement by hand—and they succeeded. Then, to save themselves a little more work, they rigged up a motor for it: They wrapped a long rope around the drum of the mixer, and secured it to a horse, which one of the younger children led away. Once the horse reached the end of the rope, the cement was mixed and ready to pour.

By 1950, the house was finished, inside and out. Three years later, Moníka was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of the Falcon by the president of Iceland, for her services to the nation. She was the first woman so honored. At first she was dumbfounded. Why was a simple housewife and farmer being given this honor? Then she thought about it. As she told her daughters, I suppose I deserve it as much as anyone does.

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Published on August 24, 2022 08:00

April 6, 2022

How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

Icelanders believe in elves. Does that make you laugh?

I used to find it funny too. I used to think Icelanders who spoke of elves were playing tricks, poking fun, talking tongue-in-cheek, telling tall tales.

Then I met Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir, a well-known elf-seer. We took a walk in a lava field she and her elf friends had protected from destruction when a new road was built nearby. We didn't talk much about elves or the Hidden Folk as we walked. Instead, we photographed lava crags and stacks and pillars, pillows of silver-green moss, caves and clefts and individual lichen-splashed rocks. It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea.

It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea.

We wandered about pointing out plants. I didn’t keep a list, but two hours later, back at my hotel when I wrote up my recollections, I remembered blueberry, crowberry, stone bramble, violet, dandelion, mountain avens, buttercup, butterwort, wood geranium, wild thyme, willow shrubs with pale fluffy catkins, and several kinds of grass, including sheep’s sorrel, which we tasted—it was sour as limes. Elves’ cup moss was the only sign of elves I saw.

We listened to the wind sighing in the knee-high willows and the incessant cries of seabirds: black-backed gulls barking now! now! now! and arctic terns, many terns, with their piercing kree-yah cries.

We talked about art and inspiration. What is inspiration? Why do some places attract artists and spark creative thought? Why are some places beautiful—and how do you define beauty?

And we shared an experience I still can't explain.

Said Ragnhildur, as we left the lava field, "Now do you believe in elves?" In my next book,

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf.

In my next book,

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf.

Illuminated by my encounters with Iceland's Otherworld over the last 35 years—in ancient lava fields, on a holy mountain, beside a glacier and an erupting volcano, crossing the cold desert at the island's heart on horseback— Looking for the Hidden Folk offers an intimate conversation about how we look at and find value in nature. It reveals how the words we use and the stories we tell shape the world we see. It argues that our beliefs about the Earth will preserve, or destroy, it.

Scientists name our time the Anthropocene, the Human Age: Climate change will lead to the mass extinction of species unless we humans change course. Iceland suggests a different way of thinking about the Earth, one that to me offers hope. Icelanders believe in elves, and you should too.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I'm currently putting together my book tour, scheduling both online talks and (let's hope) in-person appearances. Let me know at nancymariebrown@gmail.com if you'd like to organize an event to help get the word out about Looking for the Hidden Folk .

I used to find it funny too. I used to think Icelanders who spoke of elves were playing tricks, poking fun, talking tongue-in-cheek, telling tall tales.

Then I met Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir, a well-known elf-seer. We took a walk in a lava field she and her elf friends had protected from destruction when a new road was built nearby. We didn't talk much about elves or the Hidden Folk as we walked. Instead, we photographed lava crags and stacks and pillars, pillows of silver-green moss, caves and clefts and individual lichen-splashed rocks.

It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea.

It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea. We wandered about pointing out plants. I didn’t keep a list, but two hours later, back at my hotel when I wrote up my recollections, I remembered blueberry, crowberry, stone bramble, violet, dandelion, mountain avens, buttercup, butterwort, wood geranium, wild thyme, willow shrubs with pale fluffy catkins, and several kinds of grass, including sheep’s sorrel, which we tasted—it was sour as limes. Elves’ cup moss was the only sign of elves I saw.

We listened to the wind sighing in the knee-high willows and the incessant cries of seabirds: black-backed gulls barking now! now! now! and arctic terns, many terns, with their piercing kree-yah cries.

We talked about art and inspiration. What is inspiration? Why do some places attract artists and spark creative thought? Why are some places beautiful—and how do you define beauty?

And we shared an experience I still can't explain.

Said Ragnhildur, as we left the lava field, "Now do you believe in elves?"

In my next book,

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf.

In my next book,

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf. Illuminated by my encounters with Iceland's Otherworld over the last 35 years—in ancient lava fields, on a holy mountain, beside a glacier and an erupting volcano, crossing the cold desert at the island's heart on horseback— Looking for the Hidden Folk offers an intimate conversation about how we look at and find value in nature. It reveals how the words we use and the stories we tell shape the world we see. It argues that our beliefs about the Earth will preserve, or destroy, it.

Scientists name our time the Anthropocene, the Human Age: Climate change will lead to the mass extinction of species unless we humans change course. Iceland suggests a different way of thinking about the Earth, one that to me offers hope. Icelanders believe in elves, and you should too.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. I'm currently putting together my book tour, scheduling both online talks and (let's hope) in-person appearances. Let me know at nancymariebrown@gmail.com if you'd like to organize an event to help get the word out about Looking for the Hidden Folk .

Published on April 06, 2022 08:06

March 30, 2022

Sami Tales Told "By the Fire"

The Sami of northern Sweden "felt such a personal connection to the trees whose wood they burned, mostly birch and pine, that they chopped 'eyes' in the firewood, so the pieces of wood 'could see they were burning well.'"

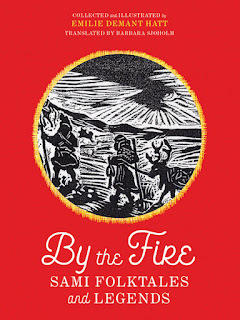

I learned this in a delightful book called By the Fire: Sami Folktales and Legends . Collected and illustrated by Emilie Demant Hatt, and translated by Barbara Sjoholm, it includes 70-some tales, along with Demant Hatt's introduction, selections from her fieldnotes, and an essay by Sjoholm.

The nomadic reindeer-herding Sami of the far north often appear in the medieval Icelandic sagas, which provide the source material for most of my own books. The Vikings traded with the Sami for skins, furs, feathers, and walrus ivory, and several Norwegian kings and chieftains forced them to pay tribute--that is, protection money. Sami men and women also appear in the Icelandic sagas as sorcerors and shamans, able to shift their shapes, foretell the future, and find lost things.

The nomadic reindeer-herding Sami of the far north often appear in the medieval Icelandic sagas, which provide the source material for most of my own books. The Vikings traded with the Sami for skins, furs, feathers, and walrus ivory, and several Norwegian kings and chieftains forced them to pay tribute--that is, protection money. Sami men and women also appear in the Icelandic sagas as sorcerors and shamans, able to shift their shapes, foretell the future, and find lost things.

As a student of comparative literature, I am intrigued by how similar some of Demant Hatt's Sami tales are with other folklore I’m familiar with. For example, Cinderella-type stories are found among the Sami, with evil stepmothers, handsome princes, too-small-slippers that require the chopping off of heels or toes, and all.

As in Icelandic folktales, the Sami speak of Hidden Folk or elves, here called the Haldes. In one story, for example, the evil stepmother tells the girl to spin yarn "at the edge of a gorge, at the bottom of which there was a deep spring. The ball of yarn rolled away from the girl, and when she tried to snatch it, she fell into the spring. But down there she met the good Haldes." The Haldes hire the girl to tend their cows, and eventually let her return home, carrying her wages in gold and silver.

But what I really enjoy reading folktales for are the differences—the things I have not heard before and would not have thought of myself.

Along with the Sami chopping "eyes" in their firewood, for example, in By the Fire I learned about the evil Stallo. A kind of people-eating troll, Stallo "goes around whistling all the time so one can hear when he is in the vicinity. All whistling is taboo among the Sami: the sound of it is absolutely connected with the Evil One and with sorcery."

In Sami language, you can be deaf as Stallo, large as Stallo, or have Stallo's skinny legs. If you had a large head--a small, round head was key to the Sami concept of beauty--you had a Stallo head. If you ate alone, you ate like Stallo. If you had a child with a man you didn't care to marry, that child was Stallo's child.

Stallo also explains the landscape: A single standing stone marks a Stallo grave. A ring of stones is a ruined Stallo tent.

And while Stallo is usually presented as evil, his belt is decorated with a silver star bearing three faces; if you find (or steal) a Stallo-star, you can cure many diseases.

Unlike most folktale collections from the north, as translator Barbara Sjoholm points out, By the Fire contains stories told to Emilie Demant Hatt "as part of other conversations, ethnographic and social, that took place 'by the fire' in tents or turf huts or out in the open air."

Demant Hatt was the first ("and for a long time the only," Sjoholm adds) Scandinavian anthropologist to take an interest in the lives of women and children. Most of the stories she recorded were those that women told among themselves as they worked--sometimes answering Demant Hatt's questions, more often giving conscious performances to entertain the group. In these stories, girls outfox their attackers, girls save their people--and murdered babies come back to haunt their parents.

By the Fire is beautifully illustrated with Demant Hatt's bold and eerie linocuts. Trained as an artist, Demant Hatt first went to northern Sweden in 1904 as a tourist. Inspired by Sami culture, she returned to live with them for many months in 1907. She studied Sami language at the University of Copenhagen, soon becoming fluent, and taught herself ethnography. From 1910 through 1916 she spent her summers with the Sami, first by herself, then bringing along her husband, a graduate student in cultural geography, who sometimes took notes for her while she conducted interviews. Her field notes fill 500 typed pages.

Demant Hatt wrote a memoir of her early adventures, With the Lapps in the High Mountains: A Woman among the Sami, 1907-1908 , which has been edited and translated by Barbara Sjoholm. Sjoholm also wrote her biography, Black Fox: A Life of Emilie Demant Hatt, Artist and Ethnographer . Two more books to add to my reading list!

For more book recommendations, see my lists at Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I learned this in a delightful book called By the Fire: Sami Folktales and Legends . Collected and illustrated by Emilie Demant Hatt, and translated by Barbara Sjoholm, it includes 70-some tales, along with Demant Hatt's introduction, selections from her fieldnotes, and an essay by Sjoholm.

The nomadic reindeer-herding Sami of the far north often appear in the medieval Icelandic sagas, which provide the source material for most of my own books. The Vikings traded with the Sami for skins, furs, feathers, and walrus ivory, and several Norwegian kings and chieftains forced them to pay tribute--that is, protection money. Sami men and women also appear in the Icelandic sagas as sorcerors and shamans, able to shift their shapes, foretell the future, and find lost things.

The nomadic reindeer-herding Sami of the far north often appear in the medieval Icelandic sagas, which provide the source material for most of my own books. The Vikings traded with the Sami for skins, furs, feathers, and walrus ivory, and several Norwegian kings and chieftains forced them to pay tribute--that is, protection money. Sami men and women also appear in the Icelandic sagas as sorcerors and shamans, able to shift their shapes, foretell the future, and find lost things. As a student of comparative literature, I am intrigued by how similar some of Demant Hatt's Sami tales are with other folklore I’m familiar with. For example, Cinderella-type stories are found among the Sami, with evil stepmothers, handsome princes, too-small-slippers that require the chopping off of heels or toes, and all.

As in Icelandic folktales, the Sami speak of Hidden Folk or elves, here called the Haldes. In one story, for example, the evil stepmother tells the girl to spin yarn "at the edge of a gorge, at the bottom of which there was a deep spring. The ball of yarn rolled away from the girl, and when she tried to snatch it, she fell into the spring. But down there she met the good Haldes." The Haldes hire the girl to tend their cows, and eventually let her return home, carrying her wages in gold and silver.

But what I really enjoy reading folktales for are the differences—the things I have not heard before and would not have thought of myself.

Along with the Sami chopping "eyes" in their firewood, for example, in By the Fire I learned about the evil Stallo. A kind of people-eating troll, Stallo "goes around whistling all the time so one can hear when he is in the vicinity. All whistling is taboo among the Sami: the sound of it is absolutely connected with the Evil One and with sorcery."

In Sami language, you can be deaf as Stallo, large as Stallo, or have Stallo's skinny legs. If you had a large head--a small, round head was key to the Sami concept of beauty--you had a Stallo head. If you ate alone, you ate like Stallo. If you had a child with a man you didn't care to marry, that child was Stallo's child.

Stallo also explains the landscape: A single standing stone marks a Stallo grave. A ring of stones is a ruined Stallo tent.

And while Stallo is usually presented as evil, his belt is decorated with a silver star bearing three faces; if you find (or steal) a Stallo-star, you can cure many diseases.

Unlike most folktale collections from the north, as translator Barbara Sjoholm points out, By the Fire contains stories told to Emilie Demant Hatt "as part of other conversations, ethnographic and social, that took place 'by the fire' in tents or turf huts or out in the open air."

Demant Hatt was the first ("and for a long time the only," Sjoholm adds) Scandinavian anthropologist to take an interest in the lives of women and children. Most of the stories she recorded were those that women told among themselves as they worked--sometimes answering Demant Hatt's questions, more often giving conscious performances to entertain the group. In these stories, girls outfox their attackers, girls save their people--and murdered babies come back to haunt their parents.

By the Fire is beautifully illustrated with Demant Hatt's bold and eerie linocuts. Trained as an artist, Demant Hatt first went to northern Sweden in 1904 as a tourist. Inspired by Sami culture, she returned to live with them for many months in 1907. She studied Sami language at the University of Copenhagen, soon becoming fluent, and taught herself ethnography. From 1910 through 1916 she spent her summers with the Sami, first by herself, then bringing along her husband, a graduate student in cultural geography, who sometimes took notes for her while she conducted interviews. Her field notes fill 500 typed pages.

Demant Hatt wrote a memoir of her early adventures, With the Lapps in the High Mountains: A Woman among the Sami, 1907-1908 , which has been edited and translated by Barbara Sjoholm. Sjoholm also wrote her biography, Black Fox: A Life of Emilie Demant Hatt, Artist and Ethnographer . Two more books to add to my reading list!

For more book recommendations, see my lists at Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Published on March 30, 2022 08:00

March 23, 2022

The Dark Queens Brunhild and Fredegund

The legend of Brynhild, the warrior woman who was betrayed by the man she loved, was one of the most popular stories in the Viking North. As I note in my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, it was told and retold for hundreds of years. Episodes were woven into tapestries. They were carved on memorial stones and doorposts and cast as metal amulets. They were alluded to in poetry and prose and worked into myths and genealogies.

But the later the version, the more romantic it becomes.

"I am a shield-maid," Brynhild cries in an early account. "I wear a helmet among the warrior-kings, and I wish to remain in their warband. I was in battle with the King of Gardariki and our weapons were red with blood. This is what I desire. I want to fight."

But she is forced to marry.

She swears to marry only a man who knew no fear. But she is tricked.

Later storytellers focus not on her ambition or the sanctity of her oath, but on passion; her crisis of honor becomes a case of jealousy. At the same time, the hero who betrayed her becomes fused with the famous Sigurd the Dragon-Slayer.