Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 4

July 28, 2021

The Year 1000

I’ve written a lot about the year 1000.

The Far Traveler

charts the voyages of a Viking woman to North America (and later, to Rome) around the year 1000.

The Abacus and the Cross

profiles the pope in the year 1000, Gerbert d'Aurillac, the leading mathematician and astronomer of his day. My latest book,

The Real Valkyrie

, tells the story of a woman warrior who died a little before 970, and whose adventurous lifestyle would have been less likely after the North was Christianized in the year 1000.

In

The Year 1000

Valerie Hansen, a professor of history at Yale, covers all that in her first 100 pages. She then proceeds to open up a medieval world I had no idea existed.

In

The Year 1000

Valerie Hansen, a professor of history at Yale, covers all that in her first 100 pages. She then proceeds to open up a medieval world I had no idea existed.

What was the "Viking Age" like in Sri Lanka? Who was the world's richest man? (Hint: He lived in Africa.) Who were the "far travelers" of the Pacific? What was the "most globalized place on earth"? (China.)

For me, Chapter Three on "The Pan-American Highways of 1000" was the most exciting. It begins, "In the year 1000, the largest city in the Americas was probably the Maya settlement of Chichen Itza, with an estimated population of some 40,000."

That's about the estimated population of the entire country of Iceland at the same time. Just think if we had as many stories about the people of Chichen Itza, in modern-day Mexico, as we have about the Icelanders.

Some 40 Sagas of Icelanders exist, written down on parchment in Old Norse in the 1200s or later. These sagas provide much of what we know about daily life in the Viking Age. They also chronicle the Vikings' travels from the Scandinavian homelands east through modern-day Russia and Ukraine to Istanbul and maybe even Baghdad, and west into the Gulf of St Lawrence and possibly much farther,

What the Maya left behind were pyramids and ball courts and temples, decorated with wall paintings depicting Maya conquests. And it's here that Hansen's history made my eyes pop. She writes:

"Across a doorway in the Temple of Warriors is a truly unusual painting. Although it's on the same wall that shows the conquest of a village, it depicts people totally unlike the warriors in other murals because they are so lifelike.

"With yellow hair, light eyes, and whitish skin, one victim has his arms tied behind his back. A second has beads woven into his blond hair, as is common for captives in other Maya paintings (both are shown in the color plates). Yet another, also with beads in his hair, floats naked in the water as a menacing fish, mouth open, hovers nearby. The artist has used Maya blue, a pigment that combines indigo with palygorskite clay, for the water. These unfortunate prisoners of war have all been thrown into the water to drown.

"Who were these light-skinned, blond-haired victims?

"Who were these light-skinned, blond-haired victims?

"Could they have been Norsemen captured by the Maya?"

Scholars have debated that identification since the paintings were discovered in the 1920s. Currently, the answer is tipping toward "yes," even though no verified Scandinavian artifacts have been found in Mexico or, indeed, anywhere else in North America south of Newfoundland.

Notes Hansen, "This isn't as serious an objection as you might think; the archaeological record is far from complete."

At L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, a Viking-style bronze pin clearly identified the site. Lacking a similar "diagnostic artifact," scholars will continue to debate how far the Vikings penetrated the Americas. But for now, Hansen says, "we have to conclude that the Vikings could have arrived in the Yucatan."

They had the means: When the replica Viking ship Gaia sailed down the American east coast in 1991, it made it all the way past the mouth of the Amazon to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil.

And there is, indeed, a story in the Icelandic sagas about a voyage to what might be Mexico, according to the 1999 research of Icelandic historian Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir, which she recently posted in English here: http://thorvald.is/. It is further discussed by Alex Harvey of the University of York here: https://theposthole.org/read/article/486.

In Eyrbyggja Saga, the famous Bjorn the Breidavik-Champion sails west from Iceland to avoid a feud and is not heard from again until, many years later, another Viking ship sailing west is blown off course, coming to land in an unknown country. There, the Vikings are captured, bound, brought before a council, and doomed to death or slavery.

They are saved by a grand old man, to whom the locals defer, who speaks to them in Norse. Before sending them back out to sea, he singles out the Icelanders in their crew and asks for news. He refuses to give his name, but sends home with them a sword and a ring for a boy and his mother in Iceland.

He tells them not to let anyone try to find him, for (in the translation of Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards), "This is a big country and the harbors are few and far between. Strangers can expect plenty of trouble here unless they happen to be as lucky as you."

Trouble, perhaps, like that experienced by the blond and blue-eyed men depicted on the wall of the Temple of Warriors in Chichen Itza: bound, decorated with beads, and drowned.

The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World--and Globalization Began by Valerie Hansen was published in 2020 by Scribner. Be sure to take a look at those color plates. (Or see http://valerie-hansen.com for some examples.)

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

In

The Year 1000

Valerie Hansen, a professor of history at Yale, covers all that in her first 100 pages. She then proceeds to open up a medieval world I had no idea existed.

In

The Year 1000

Valerie Hansen, a professor of history at Yale, covers all that in her first 100 pages. She then proceeds to open up a medieval world I had no idea existed. What was the "Viking Age" like in Sri Lanka? Who was the world's richest man? (Hint: He lived in Africa.) Who were the "far travelers" of the Pacific? What was the "most globalized place on earth"? (China.)

For me, Chapter Three on "The Pan-American Highways of 1000" was the most exciting. It begins, "In the year 1000, the largest city in the Americas was probably the Maya settlement of Chichen Itza, with an estimated population of some 40,000."

That's about the estimated population of the entire country of Iceland at the same time. Just think if we had as many stories about the people of Chichen Itza, in modern-day Mexico, as we have about the Icelanders.

Some 40 Sagas of Icelanders exist, written down on parchment in Old Norse in the 1200s or later. These sagas provide much of what we know about daily life in the Viking Age. They also chronicle the Vikings' travels from the Scandinavian homelands east through modern-day Russia and Ukraine to Istanbul and maybe even Baghdad, and west into the Gulf of St Lawrence and possibly much farther,

What the Maya left behind were pyramids and ball courts and temples, decorated with wall paintings depicting Maya conquests. And it's here that Hansen's history made my eyes pop. She writes:

"Across a doorway in the Temple of Warriors is a truly unusual painting. Although it's on the same wall that shows the conquest of a village, it depicts people totally unlike the warriors in other murals because they are so lifelike.

"With yellow hair, light eyes, and whitish skin, one victim has his arms tied behind his back. A second has beads woven into his blond hair, as is common for captives in other Maya paintings (both are shown in the color plates). Yet another, also with beads in his hair, floats naked in the water as a menacing fish, mouth open, hovers nearby. The artist has used Maya blue, a pigment that combines indigo with palygorskite clay, for the water. These unfortunate prisoners of war have all been thrown into the water to drown.

"Who were these light-skinned, blond-haired victims?

"Who were these light-skinned, blond-haired victims? "Could they have been Norsemen captured by the Maya?"

Scholars have debated that identification since the paintings were discovered in the 1920s. Currently, the answer is tipping toward "yes," even though no verified Scandinavian artifacts have been found in Mexico or, indeed, anywhere else in North America south of Newfoundland.

Notes Hansen, "This isn't as serious an objection as you might think; the archaeological record is far from complete."

At L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, a Viking-style bronze pin clearly identified the site. Lacking a similar "diagnostic artifact," scholars will continue to debate how far the Vikings penetrated the Americas. But for now, Hansen says, "we have to conclude that the Vikings could have arrived in the Yucatan."

They had the means: When the replica Viking ship Gaia sailed down the American east coast in 1991, it made it all the way past the mouth of the Amazon to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil.

And there is, indeed, a story in the Icelandic sagas about a voyage to what might be Mexico, according to the 1999 research of Icelandic historian Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir, which she recently posted in English here: http://thorvald.is/. It is further discussed by Alex Harvey of the University of York here: https://theposthole.org/read/article/486.

In Eyrbyggja Saga, the famous Bjorn the Breidavik-Champion sails west from Iceland to avoid a feud and is not heard from again until, many years later, another Viking ship sailing west is blown off course, coming to land in an unknown country. There, the Vikings are captured, bound, brought before a council, and doomed to death or slavery.

They are saved by a grand old man, to whom the locals defer, who speaks to them in Norse. Before sending them back out to sea, he singles out the Icelanders in their crew and asks for news. He refuses to give his name, but sends home with them a sword and a ring for a boy and his mother in Iceland.

He tells them not to let anyone try to find him, for (in the translation of Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards), "This is a big country and the harbors are few and far between. Strangers can expect plenty of trouble here unless they happen to be as lucky as you."

Trouble, perhaps, like that experienced by the blond and blue-eyed men depicted on the wall of the Temple of Warriors in Chichen Itza: bound, decorated with beads, and drowned.

The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World--and Globalization Began by Valerie Hansen was published in 2020 by Scribner. Be sure to take a look at those color plates. (Or see http://valerie-hansen.com for some examples.)

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on July 28, 2021 08:08

July 21, 2021

Down to Earth

Studying the Icelandic sagas, as I noted in a previous essay, is a great way to make a life. It's not, however, easy to earn a living doing so.

For many years, I worked as a science writer and editor at a university magazine to feed my Iceland habit (and myself). Leaving that job in 2003, I found myself writing less and less about science (and getting paid less and less for the magazine articles I did write), and supporting myself more and more by editing.

By accident, I established a niche editing academic papers for scholars who wrote English as a second (or third) language. No matter the topic, I found it to be satisfying work--it engaged the same part of my brain as the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzles. What was this person thinking, I asked, when she chose this word? this phrase? How could she present her point more succinctly?

Inevitably, Iceland encroached on my editing work. An anthropologist friend who wrote in both languages sent me a copy of his biography of the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson and asked what I thought. I was honest. I critiqued his voice. I told him it bothered me as a reader when he suddenly switched from academic English to colloquial speech.

He was intrigued. Do I do that? he mused.

He asked if I would help him with his then-current project, and I ended up editing and working with him to heavily revise the English edition of The Man Who Stole Himself: The Slave Odyssey of Hans Jonathan . The book was listed in the Times Literary Supplement's Books of the Year and won the Sutlive Prize for the Best Book on Historical Anthropology.

By that time I was hard at work editing Gísli Pálsson's next book,

Down to Earth

, which mixes his own memories of growing up next door to a volcano with his critical explorations, as an anthropologist, into the Anthropocene, the geological era defined by humans' growing impact on the earth. In many ways, this book was my perfect editing project: merging Iceland, science (volcanology, seismology, anthropology), and history. I'm sure there's a mention of the Icelandic sagas in there somewhere, too.

By that time I was hard at work editing Gísli Pálsson's next book,

Down to Earth

, which mixes his own memories of growing up next door to a volcano with his critical explorations, as an anthropologist, into the Anthropocene, the geological era defined by humans' growing impact on the earth. In many ways, this book was my perfect editing project: merging Iceland, science (volcanology, seismology, anthropology), and history. I'm sure there's a mention of the Icelandic sagas in there somewhere, too.

I'm grateful to Gísli for wanting his voice in English to be as strong as possible, and to his university (the University of Iceland) for providing him with research funds he could use to hire an editor.

Here is a little taste of Down to Earth :

"My first habitat was a small, wooden house on the isle of Heimaey in the Westman Islands, forty-nine square metres in size and built on bare rock that thousands of years ago had been hot lava, welling from deep below the earth's surface. The house had a name: It was called Bolstad. I have always thought Bolstad a fine name: Literally, it means 'habitat.' As my habitat, Bolstad was a microcosm of Heimaey, whose name means 'Home Island.' Bolstad was a place where the future was certain."

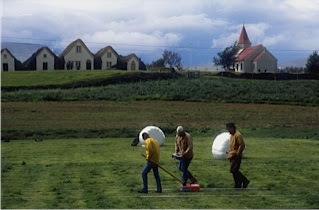

Bolstad, he tells us, "succumbed to glowing lava" when a volcano erupted on Heimaey in 1973. Gísli was not there: He was a graduate student in England, and his family had moved to Iceland's mainland.

"We were not among the five thousand refugees fleeing the eruption that night," he writes. "I did not see Bolstad destroyed. But I came across a picture, the final photo of my birthplace, around the time that I began writing this book. I was startled to see it. When I showed it to my siblings and our mother, they reacted the same way I did: shocked and silent.

"Nothing has outmatched Nature here. A light westerly breeze carries off the clouds of steam rising from the lava, giving the photographer a clear view of what once was Bolstad. The advancing lava has already buried one end wall of the house where my mother 'birthed me in the bed,' as she put it. The other end wall has been thrust forward, and the lava has set the house on fire; flames lick the roof and windows. In the heat, the sheet asbestos of the roof has exploded into white flakes, which flutter down like snow onto the black volcanic ash that has settled around the house.

"The bulky television aerial on the roof of Bolstad is still standing; it presumably still picks up a signal from the mainland, but there is no one home to receive it. I gaze at the photo for a long time, my eye drawn again and again to that aerial. Is it a metaphor for the present day?" Is it a warning?

Down to Earth by Gísli Pálsson was published in 2020 by Punctum Books. You can read the ebook for free at https://punctumbooks.com/titles/down-to-earth/. If you like it, please make a donation to this nonprofit publishing house. Their editors have to earn a living (as well as make a life), too.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

For many years, I worked as a science writer and editor at a university magazine to feed my Iceland habit (and myself). Leaving that job in 2003, I found myself writing less and less about science (and getting paid less and less for the magazine articles I did write), and supporting myself more and more by editing.

By accident, I established a niche editing academic papers for scholars who wrote English as a second (or third) language. No matter the topic, I found it to be satisfying work--it engaged the same part of my brain as the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzles. What was this person thinking, I asked, when she chose this word? this phrase? How could she present her point more succinctly?

Inevitably, Iceland encroached on my editing work. An anthropologist friend who wrote in both languages sent me a copy of his biography of the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson and asked what I thought. I was honest. I critiqued his voice. I told him it bothered me as a reader when he suddenly switched from academic English to colloquial speech.

He was intrigued. Do I do that? he mused.

He asked if I would help him with his then-current project, and I ended up editing and working with him to heavily revise the English edition of The Man Who Stole Himself: The Slave Odyssey of Hans Jonathan . The book was listed in the Times Literary Supplement's Books of the Year and won the Sutlive Prize for the Best Book on Historical Anthropology.

By that time I was hard at work editing Gísli Pálsson's next book,

Down to Earth

, which mixes his own memories of growing up next door to a volcano with his critical explorations, as an anthropologist, into the Anthropocene, the geological era defined by humans' growing impact on the earth. In many ways, this book was my perfect editing project: merging Iceland, science (volcanology, seismology, anthropology), and history. I'm sure there's a mention of the Icelandic sagas in there somewhere, too.

By that time I was hard at work editing Gísli Pálsson's next book,

Down to Earth

, which mixes his own memories of growing up next door to a volcano with his critical explorations, as an anthropologist, into the Anthropocene, the geological era defined by humans' growing impact on the earth. In many ways, this book was my perfect editing project: merging Iceland, science (volcanology, seismology, anthropology), and history. I'm sure there's a mention of the Icelandic sagas in there somewhere, too. I'm grateful to Gísli for wanting his voice in English to be as strong as possible, and to his university (the University of Iceland) for providing him with research funds he could use to hire an editor.

Here is a little taste of Down to Earth :

"My first habitat was a small, wooden house on the isle of Heimaey in the Westman Islands, forty-nine square metres in size and built on bare rock that thousands of years ago had been hot lava, welling from deep below the earth's surface. The house had a name: It was called Bolstad. I have always thought Bolstad a fine name: Literally, it means 'habitat.' As my habitat, Bolstad was a microcosm of Heimaey, whose name means 'Home Island.' Bolstad was a place where the future was certain."

Bolstad, he tells us, "succumbed to glowing lava" when a volcano erupted on Heimaey in 1973. Gísli was not there: He was a graduate student in England, and his family had moved to Iceland's mainland.

"We were not among the five thousand refugees fleeing the eruption that night," he writes. "I did not see Bolstad destroyed. But I came across a picture, the final photo of my birthplace, around the time that I began writing this book. I was startled to see it. When I showed it to my siblings and our mother, they reacted the same way I did: shocked and silent.

"Nothing has outmatched Nature here. A light westerly breeze carries off the clouds of steam rising from the lava, giving the photographer a clear view of what once was Bolstad. The advancing lava has already buried one end wall of the house where my mother 'birthed me in the bed,' as she put it. The other end wall has been thrust forward, and the lava has set the house on fire; flames lick the roof and windows. In the heat, the sheet asbestos of the roof has exploded into white flakes, which flutter down like snow onto the black volcanic ash that has settled around the house.

"The bulky television aerial on the roof of Bolstad is still standing; it presumably still picks up a signal from the mainland, but there is no one home to receive it. I gaze at the photo for a long time, my eye drawn again and again to that aerial. Is it a metaphor for the present day?" Is it a warning?

Down to Earth by Gísli Pálsson was published in 2020 by Punctum Books. You can read the ebook for free at https://punctumbooks.com/titles/down-to-earth/. If you like it, please make a donation to this nonprofit publishing house. Their editors have to earn a living (as well as make a life), too.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on July 21, 2021 07:51

July 14, 2021

The Museum You Will Never See

It's rare that I read a book about "my" Iceland, a book that captures the mix of place and people, nature and culture, history and saga that make Iceland my intellectual homeland. It's even rarer when one of these books is written by a non-Icelander.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, by A. Kendra Greene, is one of these special books, and the best I have found in a long time. Her description of stones first drew me in, when an excerpt from the book was published on LitHub; I read:

"When I say stone, perhaps I should clarify that I do not mean some plain-Jane piece of rock. I mean eye-catching. I mean white whisker-width spines radiating out in clusters like so many cowlicks. I mean a green between celery and mustard, pocked with pinprick bubbles and skimming like a rind over a vein that's crystal clear at the edges but clotting in the middle to the color of cream stirred into weak tea. I mean crystals like a jumble of molars and I mean jasper in oxblood and ocher and clover and sky, sometimes a hunk of one color but more likely a blend of two or three or five, maybe like ice creams melting together, or perhaps like cards stacked in a deck."

Here is a writer describing the indescribable, a writer reaching for words--it's like, it's like, what is it like?--and failing and trying again and, by her persistence, forcing me to see these rocks so clearly that by the end of the paragraph I am holding them in my mind's hand and setting them on the shelf of my own Icelandic rock collection. By the end of the paragraph, I had purchased the book.

I've done this before, purchased a book on the strength of a paragraph, but this time I was not disappointed one bit. The rest of The Museum of Whales is just as honest and careful and reaching and, yes, sometimes failing, and persistent in its desire to share this odd collection of museums (some imaginary) and collectors (some unimaginable) that Greene found by traveling around Iceland with her eyes--and her heart--wide open.

I've done this before, purchased a book on the strength of a paragraph, but this time I was not disappointed one bit. The rest of The Museum of Whales is just as honest and careful and reaching and, yes, sometimes failing, and persistent in its desire to share this odd collection of museums (some imaginary) and collectors (some unimaginable) that Greene found by traveling around Iceland with her eyes--and her heart--wide open.

I've been visiting Iceland since 1986. Soon after 2008, I noticed a change: little museums were sprouting up everywhere. It seemed as if the Icelanders' response to the global monetary crisis was to rummage through their closets and attics and rediscover their culture--or that their response to the "tourist eruption," after the real eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in 2010, was to corral the crowds into a museum, both to harvest their cash and to keep them from straggling all over the farm or town and getting in the way of real life.

Several of the little museums Greene explores are older than the crash. The Penis Museum dates from 1997, I learned. I've never been. I thought it was tacky; it's not. As Greene explains it, it's rather remarkable. Like many things in Iceland, it started as a joke that got out of hand and ended up being a philosophical inquiry.

The Folk Museum at Skogar, founded in 1949, is one of my favorite places in Iceland. I described it this way in an earlier blog post: "In addition to a collection of old houses, fully furnished, there's a separate building of several rooms stuffed with what can only be described as, well, stuff. There are books and embroideries and a two-stringed fiddle. There are birds' eggs, skeletons, rocks, pinned insects, pressed flowers, and a stuffed two-headed sheep. There are busts of several local dignitaries and two paintings by one of Iceland's most famous artists, Kjarval, in the basement, along with some mid-20th-century living room furniture and a famous writer's studio. There's a fishing boat. There's an excellent description of how to make spoons from cows' horns." (See "An Icelandic Horse Hair Tale.")There's a lovely array of children's bone toys.

The Folk Museum at Skogar, founded in 1949, is one of my favorite places in Iceland. I described it this way in an earlier blog post: "In addition to a collection of old houses, fully furnished, there's a separate building of several rooms stuffed with what can only be described as, well, stuff. There are books and embroideries and a two-stringed fiddle. There are birds' eggs, skeletons, rocks, pinned insects, pressed flowers, and a stuffed two-headed sheep. There are busts of several local dignitaries and two paintings by one of Iceland's most famous artists, Kjarval, in the basement, along with some mid-20th-century living room furniture and a famous writer's studio. There's a fishing boat. There's an excellent description of how to make spoons from cows' horns." (See "An Icelandic Horse Hair Tale.")There's a lovely array of children's bone toys.

According to Greene, there are some 15,000 objects at Skogar, displayed in no particular order. "This is a museum without sequence," she writes. "Even the guides say you can start anywhere. It all links, they say." And then she proceeds to prove that bold statement true. "And it's all here, the collection and the curator and the museum and the parking lot and the tour buses and maybe the garden, too, all because this someone in this someplace, a long time ago, was given a quest." Following Greene as she follows this someone on his quest is like taking a little quest of your own through Iceland's fabulous landscape and history.

According to Greene, there are some 15,000 objects at Skogar, displayed in no particular order. "This is a museum without sequence," she writes. "Even the guides say you can start anywhere. It all links, they say." And then she proceeds to prove that bold statement true. "And it's all here, the collection and the curator and the museum and the parking lot and the tour buses and maybe the garden, too, all because this someone in this someplace, a long time ago, was given a quest." Following Greene as she follows this someone on his quest is like taking a little quest of your own through Iceland's fabulous landscape and history.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is itself a museum, a collection of long articles and short essays, illustrations, lists. As a writer Greene is as observant about the Icelandic friends she makes and the historical people she researches as she is about the stones preserved in their collections. Alongside her long investigations of the penis museum, the stone museum, the bird museum, the folk museum, the witchcraft museum, the sea monster museum, and the herring museum, she includes several cabinets of curiosities, vignettes of collectors and their collections and the haphazard links between them. There's "The Museum of the Story I Heard," for instance, and "The Museum of Darkness," and "The Museum of Obligation," of which she writes: "I love this story of undaunted independence, of artistic freedom, of doubling down, of sticking it to the man. But there is a way of telling it that is all about obligation, a telling that is almost meek." And so she frames the story of this one-man museum again, and we realise the first picture she painted was merely the reflection of the place in a puddle.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, and Other Excursions to Iceland's Most Unusual Museums, by A. Kendra Greene, was published in 2020 by Penguin Books. My only complaint is that the text is printed in hard-to-read light blue ink. But I think you'll perservere.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is one of several books about Iceland and Vikings that I recommend on my Bookshop at https://bookshop.org/shop/nancymariebrown.

(Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, by A. Kendra Greene, is one of these special books, and the best I have found in a long time. Her description of stones first drew me in, when an excerpt from the book was published on LitHub; I read:

"When I say stone, perhaps I should clarify that I do not mean some plain-Jane piece of rock. I mean eye-catching. I mean white whisker-width spines radiating out in clusters like so many cowlicks. I mean a green between celery and mustard, pocked with pinprick bubbles and skimming like a rind over a vein that's crystal clear at the edges but clotting in the middle to the color of cream stirred into weak tea. I mean crystals like a jumble of molars and I mean jasper in oxblood and ocher and clover and sky, sometimes a hunk of one color but more likely a blend of two or three or five, maybe like ice creams melting together, or perhaps like cards stacked in a deck."

Here is a writer describing the indescribable, a writer reaching for words--it's like, it's like, what is it like?--and failing and trying again and, by her persistence, forcing me to see these rocks so clearly that by the end of the paragraph I am holding them in my mind's hand and setting them on the shelf of my own Icelandic rock collection. By the end of the paragraph, I had purchased the book.

I've done this before, purchased a book on the strength of a paragraph, but this time I was not disappointed one bit. The rest of The Museum of Whales is just as honest and careful and reaching and, yes, sometimes failing, and persistent in its desire to share this odd collection of museums (some imaginary) and collectors (some unimaginable) that Greene found by traveling around Iceland with her eyes--and her heart--wide open.

I've done this before, purchased a book on the strength of a paragraph, but this time I was not disappointed one bit. The rest of The Museum of Whales is just as honest and careful and reaching and, yes, sometimes failing, and persistent in its desire to share this odd collection of museums (some imaginary) and collectors (some unimaginable) that Greene found by traveling around Iceland with her eyes--and her heart--wide open. I've been visiting Iceland since 1986. Soon after 2008, I noticed a change: little museums were sprouting up everywhere. It seemed as if the Icelanders' response to the global monetary crisis was to rummage through their closets and attics and rediscover their culture--or that their response to the "tourist eruption," after the real eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in 2010, was to corral the crowds into a museum, both to harvest their cash and to keep them from straggling all over the farm or town and getting in the way of real life.

Several of the little museums Greene explores are older than the crash. The Penis Museum dates from 1997, I learned. I've never been. I thought it was tacky; it's not. As Greene explains it, it's rather remarkable. Like many things in Iceland, it started as a joke that got out of hand and ended up being a philosophical inquiry.

The Folk Museum at Skogar, founded in 1949, is one of my favorite places in Iceland. I described it this way in an earlier blog post: "In addition to a collection of old houses, fully furnished, there's a separate building of several rooms stuffed with what can only be described as, well, stuff. There are books and embroideries and a two-stringed fiddle. There are birds' eggs, skeletons, rocks, pinned insects, pressed flowers, and a stuffed two-headed sheep. There are busts of several local dignitaries and two paintings by one of Iceland's most famous artists, Kjarval, in the basement, along with some mid-20th-century living room furniture and a famous writer's studio. There's a fishing boat. There's an excellent description of how to make spoons from cows' horns." (See "An Icelandic Horse Hair Tale.")There's a lovely array of children's bone toys.

The Folk Museum at Skogar, founded in 1949, is one of my favorite places in Iceland. I described it this way in an earlier blog post: "In addition to a collection of old houses, fully furnished, there's a separate building of several rooms stuffed with what can only be described as, well, stuff. There are books and embroideries and a two-stringed fiddle. There are birds' eggs, skeletons, rocks, pinned insects, pressed flowers, and a stuffed two-headed sheep. There are busts of several local dignitaries and two paintings by one of Iceland's most famous artists, Kjarval, in the basement, along with some mid-20th-century living room furniture and a famous writer's studio. There's a fishing boat. There's an excellent description of how to make spoons from cows' horns." (See "An Icelandic Horse Hair Tale.")There's a lovely array of children's bone toys.  According to Greene, there are some 15,000 objects at Skogar, displayed in no particular order. "This is a museum without sequence," she writes. "Even the guides say you can start anywhere. It all links, they say." And then she proceeds to prove that bold statement true. "And it's all here, the collection and the curator and the museum and the parking lot and the tour buses and maybe the garden, too, all because this someone in this someplace, a long time ago, was given a quest." Following Greene as she follows this someone on his quest is like taking a little quest of your own through Iceland's fabulous landscape and history.

According to Greene, there are some 15,000 objects at Skogar, displayed in no particular order. "This is a museum without sequence," she writes. "Even the guides say you can start anywhere. It all links, they say." And then she proceeds to prove that bold statement true. "And it's all here, the collection and the curator and the museum and the parking lot and the tour buses and maybe the garden, too, all because this someone in this someplace, a long time ago, was given a quest." Following Greene as she follows this someone on his quest is like taking a little quest of your own through Iceland's fabulous landscape and history. The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is itself a museum, a collection of long articles and short essays, illustrations, lists. As a writer Greene is as observant about the Icelandic friends she makes and the historical people she researches as she is about the stones preserved in their collections. Alongside her long investigations of the penis museum, the stone museum, the bird museum, the folk museum, the witchcraft museum, the sea monster museum, and the herring museum, she includes several cabinets of curiosities, vignettes of collectors and their collections and the haphazard links between them. There's "The Museum of the Story I Heard," for instance, and "The Museum of Darkness," and "The Museum of Obligation," of which she writes: "I love this story of undaunted independence, of artistic freedom, of doubling down, of sticking it to the man. But there is a way of telling it that is all about obligation, a telling that is almost meek." And so she frames the story of this one-man museum again, and we realise the first picture she painted was merely the reflection of the place in a puddle.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, and Other Excursions to Iceland's Most Unusual Museums, by A. Kendra Greene, was published in 2020 by Penguin Books. My only complaint is that the text is printed in hard-to-read light blue ink. But I think you'll perservere.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is one of several books about Iceland and Vikings that I recommend on my Bookshop at https://bookshop.org/shop/nancymariebrown.

(Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.)

Published on July 14, 2021 08:06

July 7, 2021

The Woman Who Licked Her Paintbrush

It is the blue of blues, the ultra-blue or ultramarine. It is "a color illustrious, beautiful, and most perfect, beyond all other colors," wrote Cennino D’Andrea Cennini in Il Libro dell’Arte in the early 1400s.

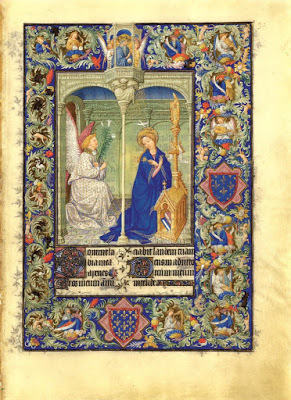

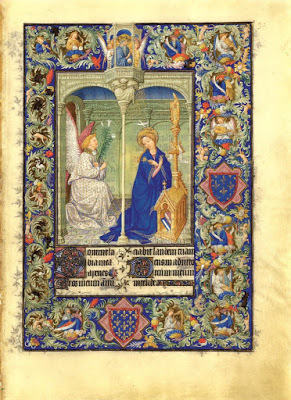

And for that reason, it is the blue of the Virgin Mary's gown in medieval manuscripts like this one, from the Cloisters Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MS54.1.1 Folio 30r).

The color was made by grinding lapis lazuli, a brilliant blue stone mined in only one place in the world--Afghanistan. The powder was mixed with pine rosin, gum mastic, and wax, kneaded by hands greased with linseed oil, dissolved into lye, then dried and packed into leather purses. If of the best quality, one ounce of ultramine blue was worth an ounce of gold.

The color was made by grinding lapis lazuli, a brilliant blue stone mined in only one place in the world--Afghanistan. The powder was mixed with pine rosin, gum mastic, and wax, kneaded by hands greased with linseed oil, dissolved into lye, then dried and packed into leather purses. If of the best quality, one ounce of ultramine blue was worth an ounce of gold.

It was so costly that only the finest luxury books contain it--and only scribes "of exceptional skill would have been entrusted with its use," writes Anita Radini and her colleagues in a 2019 paper in Science Advances.

So how did bits of ultramarine end up stuck between the teeth of a middle-aged woman buried sometime before 1162 beside a German church?

Most likely, she was an artist who licked her brush.

It's a pretty common thing for artists to do, to get a finer line. It's common especially for an artist illustrating a medieval manuscript, in which the images are often tiny. Except for one problem: "It has long been assumed that monks, rather than nuns, were the primary producers of books throughout the Middle Ages," the researchers write.

Why would a mere woman be trusted with the blue of blues?

Radini and her colleagues weren't expecting to get into the gender politics of art history when they examined the skeletons buried beside the ruins of a 9th- to 14th-century church and monastery at Dalheim, Germany. They were looking for plant particles stuck in dental calculus--the cement-like stuff your dental hygienist spends her time picking out from the backs of your teeth. They were hoping to find out what the people ate.

It took a while, and some creative scientific analyses, for them to realize the blue bits they'd found in this skeleton's teeth were particles of lapis lazuli. Even longer to figure out how a stone from Afghanistan ended up in a medieval woman's mouth.

It took a while, and some creative scientific analyses, for them to realize the blue bits they'd found in this skeleton's teeth were particles of lapis lazuli. Even longer to figure out how a stone from Afghanistan ended up in a medieval woman's mouth.

The simplest answer is that she was an artist of exceptional skill who produced luxury books using ultramarine and that she was in the habit of licking her paintbrush. Repeatedly, over many years.

And yes, the researchers DNA-tested the skeleton to make sure this artist really was female.

Why has it "long been assumed that monks, rather than nuns, were the primary producers of books throughout the Middle Ages"? Why do most medievalists assume that men could be scribes and artists, but women could not? Before the 15th century, scribes and illuminators rarely signed their work, but the names we do have skew strongly masculine.

To me, that proves only that men were more likely to sign their work--not that men were more likely to create it.

Indeed, recent research has identified work by women scribes and illuminators from as early as the 8th century. By the 12th century, several convents and nunneries were busily producing luxury books. One female scribe who lived in the monastery of Wessobrunn in Bavaria in the 1100s, for example, is known to have produced more than 40 books, including a richly illustrated gospel book. Her name was Diemut. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, when "record-keeping in Germany is more complete," Radini and her colleagues note, "more than 4,000 books attributed to over 400 women scribes have been identified."

The mention of record-keeping is key.

The 45- to 60-year-old woman who licked her paintbrush and was buried beside the church in Dalheim in the 1100s was lost to history--along with her sisters and all of the books they may have produced--when the church and the convent beside it burned down "following a series of 14th-century battles." Their cemetary was unmarked. Their graves were rediscovered by the Westphalian Museum of Archaeology, during excavations around the church ruins from 1988 to 1991, and their bones were put into storage until this research team in the 21st century had the idea of cleaning their teeth.

The bits of blue they discovered embedded there change our picture of women's status in the Middle Ages.

As Radini and her colleagues conclude, "As was the case for many early women's religious communities, Dalheim has left very few traces in the historical record. No books survive from the monastery, either from its libraries or in any other surviving works. Nearly invisible in the historical record, the women of Dalheim are known to us today nearly exclusively through the archaeological record and a handful of brief textual references. The case of Dalheim raises questions as to how many other early women's communities in Germany, including communities engaged in book production, have been similarly erased from history."

To learn about other medieval women whose lives have left few traces in the historical record, check out my new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women . The Real Valkyrie will be available from your favorite bookseller on August 31. If you want to give a little extra support to the author, buy it from my Bookshop, at https://bookshop.org/lists/books-by-nancy-marie-brown (Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.)

And for that reason, it is the blue of the Virgin Mary's gown in medieval manuscripts like this one, from the Cloisters Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MS54.1.1 Folio 30r).

The color was made by grinding lapis lazuli, a brilliant blue stone mined in only one place in the world--Afghanistan. The powder was mixed with pine rosin, gum mastic, and wax, kneaded by hands greased with linseed oil, dissolved into lye, then dried and packed into leather purses. If of the best quality, one ounce of ultramine blue was worth an ounce of gold.

The color was made by grinding lapis lazuli, a brilliant blue stone mined in only one place in the world--Afghanistan. The powder was mixed with pine rosin, gum mastic, and wax, kneaded by hands greased with linseed oil, dissolved into lye, then dried and packed into leather purses. If of the best quality, one ounce of ultramine blue was worth an ounce of gold.It was so costly that only the finest luxury books contain it--and only scribes "of exceptional skill would have been entrusted with its use," writes Anita Radini and her colleagues in a 2019 paper in Science Advances.

So how did bits of ultramarine end up stuck between the teeth of a middle-aged woman buried sometime before 1162 beside a German church?

Most likely, she was an artist who licked her brush.

It's a pretty common thing for artists to do, to get a finer line. It's common especially for an artist illustrating a medieval manuscript, in which the images are often tiny. Except for one problem: "It has long been assumed that monks, rather than nuns, were the primary producers of books throughout the Middle Ages," the researchers write.

Why would a mere woman be trusted with the blue of blues?

Radini and her colleagues weren't expecting to get into the gender politics of art history when they examined the skeletons buried beside the ruins of a 9th- to 14th-century church and monastery at Dalheim, Germany. They were looking for plant particles stuck in dental calculus--the cement-like stuff your dental hygienist spends her time picking out from the backs of your teeth. They were hoping to find out what the people ate.

It took a while, and some creative scientific analyses, for them to realize the blue bits they'd found in this skeleton's teeth were particles of lapis lazuli. Even longer to figure out how a stone from Afghanistan ended up in a medieval woman's mouth.

It took a while, and some creative scientific analyses, for them to realize the blue bits they'd found in this skeleton's teeth were particles of lapis lazuli. Even longer to figure out how a stone from Afghanistan ended up in a medieval woman's mouth. The simplest answer is that she was an artist of exceptional skill who produced luxury books using ultramarine and that she was in the habit of licking her paintbrush. Repeatedly, over many years.

And yes, the researchers DNA-tested the skeleton to make sure this artist really was female.

Why has it "long been assumed that monks, rather than nuns, were the primary producers of books throughout the Middle Ages"? Why do most medievalists assume that men could be scribes and artists, but women could not? Before the 15th century, scribes and illuminators rarely signed their work, but the names we do have skew strongly masculine.

To me, that proves only that men were more likely to sign their work--not that men were more likely to create it.

Indeed, recent research has identified work by women scribes and illuminators from as early as the 8th century. By the 12th century, several convents and nunneries were busily producing luxury books. One female scribe who lived in the monastery of Wessobrunn in Bavaria in the 1100s, for example, is known to have produced more than 40 books, including a richly illustrated gospel book. Her name was Diemut. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, when "record-keeping in Germany is more complete," Radini and her colleagues note, "more than 4,000 books attributed to over 400 women scribes have been identified."

The mention of record-keeping is key.

The 45- to 60-year-old woman who licked her paintbrush and was buried beside the church in Dalheim in the 1100s was lost to history--along with her sisters and all of the books they may have produced--when the church and the convent beside it burned down "following a series of 14th-century battles." Their cemetary was unmarked. Their graves were rediscovered by the Westphalian Museum of Archaeology, during excavations around the church ruins from 1988 to 1991, and their bones were put into storage until this research team in the 21st century had the idea of cleaning their teeth.

The bits of blue they discovered embedded there change our picture of women's status in the Middle Ages.

As Radini and her colleagues conclude, "As was the case for many early women's religious communities, Dalheim has left very few traces in the historical record. No books survive from the monastery, either from its libraries or in any other surviving works. Nearly invisible in the historical record, the women of Dalheim are known to us today nearly exclusively through the archaeological record and a handful of brief textual references. The case of Dalheim raises questions as to how many other early women's communities in Germany, including communities engaged in book production, have been similarly erased from history."

To learn about other medieval women whose lives have left few traces in the historical record, check out my new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women . The Real Valkyrie will be available from your favorite bookseller on August 31. If you want to give a little extra support to the author, buy it from my Bookshop, at https://bookshop.org/lists/books-by-nancy-marie-brown (Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.)

Published on July 07, 2021 07:29

June 30, 2021

The Real Valkyrie: The First Reviews Are In!

“Stirring,” “passionate,” “entertaining,” “well-researched,” and (I like this one best) “convincing.”

When you’ve worked on a book for four years—as I have on The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, coming to bookstores on August 31—those are really nice adjectives to see in the book's first official review. And from the notoriously hard-to-please Kirkus Reviews, no less.

You can read the full review here.

"If Nancy had told me in advance what she intended to do I would have been skeptical," an early reader told my editor, "but she has pulled it off wonderfully.

"The Real Valkyrie is magnificent," she continued. "It captured me from the very first page. Brown manages to take the limited but startling information that one of richest graves of any Viking warrior ever discovered was that of a woman and paints a stunning tapestry of what life must have been like for a bold, brave woman in medieval times. Drawing upon her deep knowledge of Viking history, she creates an unforgettable character."

Wow! This reader, Pat Shipman, a friend and fellow author, might be my perfect reader.

Like me, she writes about ancient history, anthropology, and spunky women. One of my favorite Shipman titles is To the Heart of the Nile, about a young woman who escaped slavery and set off to explore Central Africa, searching for the source of the Nile. Pat has also written about archaeopteryx, the Missing Link, Mata Hari, and most recently, in The Invaders, how humans and their dogs drove the Neanderthals to extinction.

Check out Pat's many fascinating books here.

Pat was right to be skeptical. I was skeptical too. The first draft of The Real Valkyrie was much less bold. The "valkyrie" of the title, the woman warrior buried in grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden in the mid-900s, was (as my editor rightly pointed out at the time) only a shadowy character when I turned in my manuscript, on deadline, in late 2019.

Then the pandemic hit. My publishing timetable got set back more than a year, and my editor at St. Martin's Press turned crisis into opportunity by giving me three precious gifts: time, space, and support. Take as much time as you want, and add as many more words as you need, she said. And don't be afraid to break conventions.

Like unraveling a sweater and reknitting it in a different pattern and size, I took apart Draft #1. I completely restructured the book, adding an entirely new thread to the story.

First, I gave the woman whose bones were buried in Birka grave Bj581 a name: Hervor, after the warrior woman in a classic Old Norse poem.

Then--following the style of Snorri Sturluson, writing hundreds of years after the events he described in his sagas of the kings of Norway--I wove together poems and sagas and things experts told me to imagine her life.

It was the only way. The events that shaped the warrior woman buried in Bj581 will always be hidden. All we have are her bones and the things buried with her.

So to bring Hervor’s story to life, I began each chapter as historical fiction, then stepped back and explained my sources, being particularly careful to make clear what was historical fact and what was my own speculation.

The result, I realized when I had nearly finished the draft, was like the documentary film I was interviewed for in 2018 about another exceptional Viking woman, Gudrid the Far-Traveler, who was the subject of two of my previous books. The filmmaker, Anna Dís Ólafsdóttir of Profilm in Iceland, combined interviews with experts and dramatic stagings of scenes from Gudrid's life, taking care to make the settings and costumes as historically accurate as modernly possible.

Pat Shipman's comments were not the only ones that convinced me (and my editor) that this new approach worked.

One of the scholars whose work I relied on while writing The Real Valkyrie was Marianne Moen. When I first began researching the roles of powerful women in the Viking Age, I was particularly influenced by her 2010 master's thesis from the University of Oslo, The Gendered Landscape: A discussion on gender, status, and power expressed in the Viking Age mortuary landscape.

I was lucky that Marianne's doctoral thesis, Challenging Gender: A reconsideration of gender in the Viking Age using the mortuary landscape (also from the University of Oslo), came out in 2019--in time for my second draft.

You can find Marianne's work on her academia.edu page, here.

Marianne, too, was generous enough to read The Real Valkyrie in manuscript. She summarized it this way: "In this forceful, engaging, and much needed book, Brown is telling a different story from what we're used to hearing. It rests on assumptions and educated guesses, but so do all stories of the past, and hers is no less valid than the classic ones we're so used to hearing: that's why it's such an excellent counterpoint, because it shows how a shifting of the gaze can reveal a completely different outcome. It’s a compelling read. I enjoyed it immensely."

I hope you will too. And please let me know what you think by leaving a review on Amazon, Goodreads, or wherever you like.

The Real Valkyrie will be available from your favorite bookseller on August 31. If you want to give a little extra support to the author, buy it from my Bookshop, here:(Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.)

When you’ve worked on a book for four years—as I have on The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, coming to bookstores on August 31—those are really nice adjectives to see in the book's first official review. And from the notoriously hard-to-please Kirkus Reviews, no less.

You can read the full review here.

"If Nancy had told me in advance what she intended to do I would have been skeptical," an early reader told my editor, "but she has pulled it off wonderfully.

"The Real Valkyrie is magnificent," she continued. "It captured me from the very first page. Brown manages to take the limited but startling information that one of richest graves of any Viking warrior ever discovered was that of a woman and paints a stunning tapestry of what life must have been like for a bold, brave woman in medieval times. Drawing upon her deep knowledge of Viking history, she creates an unforgettable character."

Wow! This reader, Pat Shipman, a friend and fellow author, might be my perfect reader.

Like me, she writes about ancient history, anthropology, and spunky women. One of my favorite Shipman titles is To the Heart of the Nile, about a young woman who escaped slavery and set off to explore Central Africa, searching for the source of the Nile. Pat has also written about archaeopteryx, the Missing Link, Mata Hari, and most recently, in The Invaders, how humans and their dogs drove the Neanderthals to extinction.

Check out Pat's many fascinating books here.

Pat was right to be skeptical. I was skeptical too. The first draft of The Real Valkyrie was much less bold. The "valkyrie" of the title, the woman warrior buried in grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden in the mid-900s, was (as my editor rightly pointed out at the time) only a shadowy character when I turned in my manuscript, on deadline, in late 2019.

Then the pandemic hit. My publishing timetable got set back more than a year, and my editor at St. Martin's Press turned crisis into opportunity by giving me three precious gifts: time, space, and support. Take as much time as you want, and add as many more words as you need, she said. And don't be afraid to break conventions.

Like unraveling a sweater and reknitting it in a different pattern and size, I took apart Draft #1. I completely restructured the book, adding an entirely new thread to the story.

First, I gave the woman whose bones were buried in Birka grave Bj581 a name: Hervor, after the warrior woman in a classic Old Norse poem.

Then--following the style of Snorri Sturluson, writing hundreds of years after the events he described in his sagas of the kings of Norway--I wove together poems and sagas and things experts told me to imagine her life.

It was the only way. The events that shaped the warrior woman buried in Bj581 will always be hidden. All we have are her bones and the things buried with her.

So to bring Hervor’s story to life, I began each chapter as historical fiction, then stepped back and explained my sources, being particularly careful to make clear what was historical fact and what was my own speculation.

The result, I realized when I had nearly finished the draft, was like the documentary film I was interviewed for in 2018 about another exceptional Viking woman, Gudrid the Far-Traveler, who was the subject of two of my previous books. The filmmaker, Anna Dís Ólafsdóttir of Profilm in Iceland, combined interviews with experts and dramatic stagings of scenes from Gudrid's life, taking care to make the settings and costumes as historically accurate as modernly possible.

Pat Shipman's comments were not the only ones that convinced me (and my editor) that this new approach worked.

One of the scholars whose work I relied on while writing The Real Valkyrie was Marianne Moen. When I first began researching the roles of powerful women in the Viking Age, I was particularly influenced by her 2010 master's thesis from the University of Oslo, The Gendered Landscape: A discussion on gender, status, and power expressed in the Viking Age mortuary landscape.

I was lucky that Marianne's doctoral thesis, Challenging Gender: A reconsideration of gender in the Viking Age using the mortuary landscape (also from the University of Oslo), came out in 2019--in time for my second draft.

You can find Marianne's work on her academia.edu page, here.

Marianne, too, was generous enough to read The Real Valkyrie in manuscript. She summarized it this way: "In this forceful, engaging, and much needed book, Brown is telling a different story from what we're used to hearing. It rests on assumptions and educated guesses, but so do all stories of the past, and hers is no less valid than the classic ones we're so used to hearing: that's why it's such an excellent counterpoint, because it shows how a shifting of the gaze can reveal a completely different outcome. It’s a compelling read. I enjoyed it immensely."

I hope you will too. And please let me know what you think by leaving a review on Amazon, Goodreads, or wherever you like.

The Real Valkyrie will be available from your favorite bookseller on August 31. If you want to give a little extra support to the author, buy it from my Bookshop, here:(Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.)

Published on June 30, 2021 08:31

July 4, 2019

Looking for Walrus in Iceland's Westfjords

The last time I drove through Iceland's mountainous West Fjords, I had a friend with me, an herbalist whom my Icelandic hosts gleefully referred to as my personal witch, and she'd brought a bottle of Rescue Remedy.

I needed it.

The roads were narrow and precipitous, and the view from the cliffs' edge down, down, down to the sparkling sea was mesmerizing, as if inviting me to soar and assuring me my rental car was capable of it. Swoop--the road rose and banked left, leaving a view of only sky, and I, well, I could keep going straight, couldn't I? And fly? I began to hyperventilate.

My fear of heights is not a fear of falling so much as the desire to fly.

Jenny, spying one of the rare pullouts on this route, urged me to stop and squeezed an eye-dropperful of Rescue Remedy onto my tongue. Whether the herb-and-alcohol mixture worked I can't say. But stopping, stretching, having a snack--these brought me back to sense. I handed her the keys. Jenny had not driven a stick for 20 years, but she agreed it was safer than letting me continue. We made it to our destination--the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft--and I promptly forgot my crisis on the cliff.

Six years and several trips to Iceland later, when I heard that a walrus had been spotted in the West Fjords, I didn't hesitate. I was researching the importance of walrus ivory in the Viking Age for my book about the Lewis chessmen, Ivory Vikings. I rented a Yaris and drove off to see it--or at least the bay it was sporting in, named "Bay of the Walrus Breeding Grounds."

Walruses are rare visitors to Iceland today, but these elephantine relatives of seals may have been what drew the first Viking settlers to this inhospitable island in the 9th century. Walrus ivory was the Vikings' gold. Light and long-lasting, walrus tusks made the perfect cargo for a Viking ship. Viking raids were bankrolled with walrus ivory. Viking trade routes were built on them.

The medieval Icelandic sagas, written some 300 years after the settlement of the country, say the founding fathers were fleeing tyranny, that they refused to kowtow to King Harald of Norway.

But ancient names of Icelandic headlands, islands, beaches, and bays refer to walrus. Tusks and bones—of adults and neonates—have been found at archaeological sites dating to Iceland's first settlement, in about AD 871.

After a hundred-some years, Iceland's walrus were extinct. The Viking hunters found new sources in Greenland's far north. By the Saga Age, a walrus in Iceland was an oddity. Only one saga tells of a walrus hunt, a flotilla of boats pursuing one lone beast on the south side of the peninsula for which I was heading.

On the ferry to the West Fjords I bumped into a friend. That "Bay of the Walrus Breeding Grounds" lay on the north side of a high, sheer cliff famous for its colonies of seabirds. At least one tourist has plunged to his death trying to photograph a cute puffin, Gugga reminded me. She, being afraid of heights, did not enjoy her visit.

Another tourist attraction was nearby: the Red Sands, a long golden beach that looked perfect (from the pictures I'd seen) for walruses to breed and bask on.

What kind of car are you driving? Gugga asked. A Yaris? You won’t make it. The road is very steep, and there's a hairpin turn, and, well, if you don't meet any other cars you might be okay on the way down, but your engine isn't big enough to make it back up.

I'd booked an expensive room in a secluded hotel in a broad bay just to the north. It had a red sand beach as well. I revised my itinerary.

But not, as it happened, enough.

The roads were washboard gravel. No shoulders or break-down lanes. Guard rails were rare, as were lane markings--which was just as well, since these roads would be classified as single-track anywhere else in the developed world. It was a beautiful, sunny, windless day (it could have been much worse) and I was hyperventilating as the road swooped and soared and clung to the cliff edge. I stopped at every pull-out or picnic table I saw (at one stop I saw 14 camper vans in a caravan going the other way; thank heavens I was not sharing the road with them!), but there was no one to take the keys.

And no Rescue Remedy.

I began singing. "Hear me, smith of Heaven," goes a famous Icelandic hymn, "your poet begs for mercy." Ave Maria, gracia plena. "She’ll be coming round the mountain when she comes." I ran through my entire repertoire. At least it kept me breathing. I made it to the hotel, sank onto a soft bed with a view of the blissfully empty golden sand beach, and took the next 24 hours to recuperate.

I’d drive to the "Bay of the Walrus Breeding Grounds" before I turned for home, I told myself. It was less than 10 kilometers up the road.

That morning when I pulled back the drapes I saw a bank of fog rolling at freight-train speed across the gray ocean and rushing up the bluff. As I watched it blotted out the headland. I began to panic. The first mountain pass on my way home was the worse. So narrow it had designated passing spots--the edges of which were crumbling down the cliffside.

I drove as fast as I could, but failed to beat the fog. At the pass, sky and road were a uniform gray. I inched down the road, sweating, heart pounding, singing my lungs out. And Mary or Heaven’s maker or maybe the six white horses heard, and I met no other cars. I made it down and out of the fog.

I did not see a walrus in the West Fjords. I did not see the beaches they basked or bred on. And I am not driving back.

I needed it.

The roads were narrow and precipitous, and the view from the cliffs' edge down, down, down to the sparkling sea was mesmerizing, as if inviting me to soar and assuring me my rental car was capable of it. Swoop--the road rose and banked left, leaving a view of only sky, and I, well, I could keep going straight, couldn't I? And fly? I began to hyperventilate.

My fear of heights is not a fear of falling so much as the desire to fly.

Jenny, spying one of the rare pullouts on this route, urged me to stop and squeezed an eye-dropperful of Rescue Remedy onto my tongue. Whether the herb-and-alcohol mixture worked I can't say. But stopping, stretching, having a snack--these brought me back to sense. I handed her the keys. Jenny had not driven a stick for 20 years, but she agreed it was safer than letting me continue. We made it to our destination--the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft--and I promptly forgot my crisis on the cliff.

Six years and several trips to Iceland later, when I heard that a walrus had been spotted in the West Fjords, I didn't hesitate. I was researching the importance of walrus ivory in the Viking Age for my book about the Lewis chessmen, Ivory Vikings. I rented a Yaris and drove off to see it--or at least the bay it was sporting in, named "Bay of the Walrus Breeding Grounds."

Walruses are rare visitors to Iceland today, but these elephantine relatives of seals may have been what drew the first Viking settlers to this inhospitable island in the 9th century. Walrus ivory was the Vikings' gold. Light and long-lasting, walrus tusks made the perfect cargo for a Viking ship. Viking raids were bankrolled with walrus ivory. Viking trade routes were built on them.

The medieval Icelandic sagas, written some 300 years after the settlement of the country, say the founding fathers were fleeing tyranny, that they refused to kowtow to King Harald of Norway.

But ancient names of Icelandic headlands, islands, beaches, and bays refer to walrus. Tusks and bones—of adults and neonates—have been found at archaeological sites dating to Iceland's first settlement, in about AD 871.

After a hundred-some years, Iceland's walrus were extinct. The Viking hunters found new sources in Greenland's far north. By the Saga Age, a walrus in Iceland was an oddity. Only one saga tells of a walrus hunt, a flotilla of boats pursuing one lone beast on the south side of the peninsula for which I was heading.

On the ferry to the West Fjords I bumped into a friend. That "Bay of the Walrus Breeding Grounds" lay on the north side of a high, sheer cliff famous for its colonies of seabirds. At least one tourist has plunged to his death trying to photograph a cute puffin, Gugga reminded me. She, being afraid of heights, did not enjoy her visit.

Another tourist attraction was nearby: the Red Sands, a long golden beach that looked perfect (from the pictures I'd seen) for walruses to breed and bask on.

What kind of car are you driving? Gugga asked. A Yaris? You won’t make it. The road is very steep, and there's a hairpin turn, and, well, if you don't meet any other cars you might be okay on the way down, but your engine isn't big enough to make it back up.

I'd booked an expensive room in a secluded hotel in a broad bay just to the north. It had a red sand beach as well. I revised my itinerary.

But not, as it happened, enough.

The roads were washboard gravel. No shoulders or break-down lanes. Guard rails were rare, as were lane markings--which was just as well, since these roads would be classified as single-track anywhere else in the developed world. It was a beautiful, sunny, windless day (it could have been much worse) and I was hyperventilating as the road swooped and soared and clung to the cliff edge. I stopped at every pull-out or picnic table I saw (at one stop I saw 14 camper vans in a caravan going the other way; thank heavens I was not sharing the road with them!), but there was no one to take the keys.

And no Rescue Remedy.

I began singing. "Hear me, smith of Heaven," goes a famous Icelandic hymn, "your poet begs for mercy." Ave Maria, gracia plena. "She’ll be coming round the mountain when she comes." I ran through my entire repertoire. At least it kept me breathing. I made it to the hotel, sank onto a soft bed with a view of the blissfully empty golden sand beach, and took the next 24 hours to recuperate.

I’d drive to the "Bay of the Walrus Breeding Grounds" before I turned for home, I told myself. It was less than 10 kilometers up the road.

That morning when I pulled back the drapes I saw a bank of fog rolling at freight-train speed across the gray ocean and rushing up the bluff. As I watched it blotted out the headland. I began to panic. The first mountain pass on my way home was the worse. So narrow it had designated passing spots--the edges of which were crumbling down the cliffside.

I drove as fast as I could, but failed to beat the fog. At the pass, sky and road were a uniform gray. I inched down the road, sweating, heart pounding, singing my lungs out. And Mary or Heaven’s maker or maybe the six white horses heard, and I met no other cars. I made it down and out of the fog.

I did not see a walrus in the West Fjords. I did not see the beaches they basked or bred on. And I am not driving back.

Published on July 04, 2019 11:46

February 8, 2017

Iceland and the Vikings

Each year I lead a week-long tour to West Iceland called "Sagas & Vikings." So I took it personally when an article on Iceland Monitor, the English language website of Iceland's newspaper Morgunblaðið, called it "exaggerated or distorted" to speak about Vikings in Iceland.

Each year I lead a week-long tour to West Iceland called "Sagas & Vikings." So I took it personally when an article on Iceland Monitor, the English language website of Iceland's newspaper Morgunblaðið, called it "exaggerated or distorted" to speak about Vikings in Iceland.A "Viking," declared Roberto Pagani, "was not anything other than a Norseman going on a summer plundering expedition," and he finds "few" of such "misbehaving Icelanders" in the medieval Icelandic sagas. He implied that luring people to Iceland to learn about Vikings was, in some way, dishonest.

I disagree. Iceland, to me, is the best place in the world to learn about Vikings. I've been going there for the past 30 years for that very purpose.

What does "Viking" mean? "Raider" or "plunderer" are, as Pagani says, medieval synonyms for Viking; some translators use the term "pirate," which tends to make my head spin.

But in modern scholarship, the term "Viking" is used widely to describe any Norse-speaker during the Viking Age, which is traditionally dated from 783 to 1066.

And raiding was not the sole defining characteristic of the age: Exploration was just as significant.

I feel quite justified, for instance, in calling my book about the Norse explorations of North America The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman. In fact, one of my goals in that book was to redefine the word "Viking" to include the role of women.

Few people have trouble imagining Leif Eiriksson, who discovered America in around the year 1000, as a Viking. Every representation of him that I have ever seen includes a spear or large axe--like this one in front of Hallgrimskirkja in Reykjavik. But why does Leif get all the credit? After his first sight of the New World, he never went back Gudrid, Leif's sister-in-law, was the real explorer. She tried to settle there twice, with two different husbands. If you want to learn about Viking explorers, put Gudrid the Far-Traveler at the top of your list.

Few people have trouble imagining Leif Eiriksson, who discovered America in around the year 1000, as a Viking. Every representation of him that I have ever seen includes a spear or large axe--like this one in front of Hallgrimskirkja in Reykjavik. But why does Leif get all the credit? After his first sight of the New World, he never went back Gudrid, Leif's sister-in-law, was the real explorer. She tried to settle there twice, with two different husbands. If you want to learn about Viking explorers, put Gudrid the Far-Traveler at the top of your list.Gudrid's voyages appear in two of the medieval Icelandic sagas, written a hundred or more years after her death. Pagani finds the importance of the Icelandic sagas "exaggerated or distorted" too, and again, I disagree. Pagani points out that many other cultures produced fine vernacular prose works in the 13th century. That may be true, but what makes medieval Icelandic literature unique is that, not only were the sagas and Eddas written, they were preserved. As I point out in Ivory Vikings, more medieval literature exists in Icelandic than in any other European language except Latin.

If you want to learn about Vikings and the Viking Age, medieval Icelandic literature is your best--and often your only--source. Without the works of Snorri Sturluson alone, as I wrote in Song of the Vikings, we would know next to nothing about Viking Age culture.

Because of Snorri’s Edda, tiny Iceland has had an enormous impact on our modern world. All the stories we know of the Vikings’ pagan religion, the Norse myths of Valhalla and the valkyries, of one-eyed Odin and the well of wisdom, of red-bearded Thor and his hammer of might, of two-faced Loki and the death of beautiful Baldur, of lovesick Freyr and lovely Freyja, the rainbow bridge, the great ash tree Yggdrasil, the world-wrapping Midgard Serpent, Heimdall’s horn, the eight-legged horse Sleipnir, Ragnarok or the Twilight of the Gods…

All the stories we know of the gods whom we still honor with the names Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday—for all of these stories Snorri is our main, and sometimes our only, source.

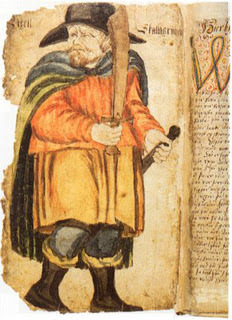

Snorri wrote his Edda originally to teach the young King Hakon (here on the left) the ins and outs of Viking poetry. For the Vikings were not only fierce warriors, they were very subtle artists. Because of the work of Snorri and his followers, we know the names of over 200 Viking skálds. We can read hundreds of their verses: In the standard edition, they fill 1,000 two-column pages. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking Age.

Snorri wrote his Edda originally to teach the young King Hakon (here on the left) the ins and outs of Viking poetry. For the Vikings were not only fierce warriors, they were very subtle artists. Because of the work of Snorri and his followers, we know the names of over 200 Viking skálds. We can read hundreds of their verses: In the standard edition, they fill 1,000 two-column pages. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking Age.We also know the history of Scandinavia in the Viking Age almost entirely through Snorri. His second book, Heimskringla, is a set of sixteen sagas about Norse kings and earls, both pagan and Christian, from the ancient days of Odin the Wizard-King through King Magnus, who was deposed in 1177, the year before Snorri’s birth. Through his vivid portraits of kings and sea-kings, raiders and traders in these sagas, Snorri created the Viking image so prevalent today.

In his third book, Egil’s Saga, Snorri expanded the archetype, creating the two competing heroic types who would give Norse culture its lasting appeal. The perfect Viking is tall, blond, and blue-eyed, a stellar athlete, a courageous fighter, an independent, honorable man who laughs in the face of danger, dying with a poem or quip on his lips. He is like Egil’s brother and uncle in this saga. Or he is like Egil, his father, and his grandfather: dark and ugly, a werewolf, a wizard, a poet, a crafty schemer who knows every promise is contingent—in fact, somewhat like Snorri himself, as he is portrayed in a saga written by his nephew.

On my "Sagas & Vikings" tour, we visit many of the places Snorri lived and wrote about, as well as the site of Gudrid's birth. We discuss the two competing stories of Iceland's settlement by Vikings--explorers and raiders both--and learn how they negotiated a society with no king. We see saga manuscripts and archaeological sites and talk about what that word "Viking" really means in the landscape that inspired our best--and often only--descriptions of Viking life. I hope you'll join me.