Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 3

October 6, 2021

Men of Terror

"Sometime near the end of the tenth century, a man named Fraði died in Sweden. His kinsmen raised a granite runestone in his memory in Denmark. Although the message carved into the stone is hard to interpret, it appears to tell us that Fraði was the first among all Vikings and that he was the terror of men. What did Fraði do in his lifetime that made him so admired…?"

So begins Men of Terror: A Comprehensive Analysis of Viking Combat by William R. Short and Reynir A. Óskarson.

Emphasis on the "comprehensive." If you have any interest in Viking Age weapons or fighting techniques, or are curious if the heroes in the Icelandic Sagas could really have performed their heroic feats, this 350-page, 2-column book is the one to reach for.

It's got everything (with one exception, which we'll get to later): the Viking mindset, shields and armor, battle tactics, raiding and dueling...

Sax, axe, sword, spear, bow and arrows: Short and Óskarson describe each weapon in great detail--enough that you can make one, if you have the skills and materials--and give copious examples from the sagas, myths, and other literary sources of how each weapon was used and thought of. Numerous illustrations and charts complement their descriptions.

But what really makes Men of Terror stand out from similar books on Viking Age weaponry are the sections on the "physics of" each weapon.

The long, single-edged knife called a sax (or, less correctly, a scramasax), for example, is "a robust, trusty weapon." Designed for hacking (not stabbing), a sax, compared to a sword, is "less likely to break or fail when abused."

But it takes more raw strength to kill with a sax.

Here's why: "Compared to other cutting weapons such as the axe and sword, the sax is generally shorter and lighter, with most of the mass distributed closer to the hand than to the tip. A computer model of the weapon shows the smaller effective mass at the contact point and the lower linear velocities at impact together result in less energy delivered to the target when cutting with a sax compared to cutting with an axe or a sword, all other things being equal. Measurements confirm the model. The energy delivered by a replica sax to a target measured about 40 percent less than the energy delivered by a replica sword, not dissimilar to what the computer model predicted."

Follow the footnotes and you can peer into Short's Viking research studio, Hurstwic, in Massachusetts. There, he and his team attached a three-axis accelerometer to a heavy boxing-type bag (fixed so it couldn't swing). Multiple fighters attacked the target on the bag multiple times, with a replica sax, sword, one-handed axe, and two-handed axe. The data was recorded, checked, averaged, and then compared to a computer model built from the physical parameters of each weapon and how the hand grasps it.

Caption: Scenes from the Hurstwic Facebook page.

Caption: Scenes from the Hurstwic Facebook page.

Did I mention Short is a research scientist with a degree from MIT and dozens of patents? His approach to reverse-engineering Viking combat techniques, he explains, is to "create a hypothesis that can be tested" and then to test it again and again. If you want data, this book has it.

The physics of the sax may explain why saxes are so rare in Viking sources. Archaeologists in Norway, for example, count 130 swords for every sax they find and, according to Short's own calculations, "only about 6 percent of the attacks in the [Icelandic Family] sagas are made with saxes." Perhaps also, he and Óskarson speculate, "it is for this reason that saxes were the prized weapon of jötnar (giants), ghosts, and men who had the strength of a giant."

Strength was also the deciding factor, Short and Óskarson argue, in wrestling or "empty-hand combat." In the sagas, this type of fighting is called glíma or fang. It is "the only combative activity alive today that holds a documented, nearly unbroken line that can be traced back to the Vikings," they say, but warn that the art has changed. "In the Viking Age, strength and power were valued in a wrestler," they argue, "but in modern glíma, finesse, agility, and beauty are what is most prized."

Viking fang "was a test of a man’s strength in a society that placed a premium on strength." It was the sport of Thor, the strongest of the gods.

As such, it "gives us clues about the mindset of the Vikings in combat," say Short and Óskarson. Wrestlers "need to be constantly on alert." They need to act "with 100 percent determination.... A warrior who has as his basis or foundation an aggressive, power-based wrestling would stand differently than a warrior who has as his basis a more technical system of wrestling or a striking art. A fighter’s lowering his center of gravity and adhering strictly to the most functional way to keep his balance gives us clues as to how he would stand in a combative situation.... The core of fang centered on raw power, swift movement, and cunning."

Some readers (like me) may have been annoyed by the sexist language in these quotations from

Men of Terror

. They are not a mistake.

Men of Terror

is a book-length argument against my thesis, in

The Real Valkyrie

, that women could be warriors in the Viking Age. Despite the fact that Thor's opponent in his famous wrestling match (as Short and Óskarson do point out) is a woman--the old giant woman Elli, a personification of old age--they believe Viking warriors were men: "men of terror."

Some readers (like me) may have been annoyed by the sexist language in these quotations from

Men of Terror

. They are not a mistake.

Men of Terror

is a book-length argument against my thesis, in

The Real Valkyrie

, that women could be warriors in the Viking Age. Despite the fact that Thor's opponent in his famous wrestling match (as Short and Óskarson do point out) is a woman--the old giant woman Elli, a personification of old age--they believe Viking warriors were men: "men of terror."

Their book's title comes from a runestone cited and translated in the Samnordisk rune-text database. It begins: "Ástráðr and Hildungr raised this stone in memory of Fraði, their kinsmen. And he was then the terror of men."

The word translated as "of men" is vera. This word can also mean "of people." It is used, for example, in veröld, which means “world,” with öld meaning “time” or “age.” Thus veröld literally means “the age of humans” or “the time of humans,” i.e. what we now call the anthropocene. Ver is also used in compounds like Oddaverjar, or “people/family of Oddi.” You wouldn’t translate ver today to mean only masculine humans. It refers to all people--which is what “men” used to mean when the first translations from Old Norse to English were made, as in “good will to all men."

So instead of "Men of Terror," I would call Short and Óskarson's book, "People of Terror"--or would I?

Let's not be ridiculous. A title is a marketing tool, and "Men of Terror" is much catchier.

In Men of Terror , Short and Óskarson are simply focusing on men like I focused on women in The Real Valkyrie . Not to exclude the other sex, but to zero in on this particular elite cohort of Viking Age people: men of terror, i.e. professional male warriors with the strength of giants.

Short and Óskarson don’t need to talk about women warriors—I did that (and Short knows it; he even gave me a nice blurb for the book cover). They also don’t talk about male craftsmen or farmers or old men or boys, etc. Their focus is on what made these particular men terrible. If writing books about exceptional Viking women is justified, so is writing books about exceptional Viking men.

Men of Terror is a rich and stimulating--and yes, comprehensive!--look at one important aspect of life in the Viking Age. It deserves to be a classic.

To leave you with one last example of the many quirky questions the book answers, do you remember the episode in Njal's Saga where Gunnar is using his bow to fend off the enemies encircling his house when his bowstring breaks? He asks his wife for two strands of her beautiful long hair to braid into a bowstring, and she refuses--dooming him to death.

Could that have worked? Can you make a bowstring out of human hair? Flip to page 120 of Men of Terror and read: "The feasibility of using human hair was tested in our research lab by gathering hair, twisting it into a string, and splicing it into a conventional bowstring that had been cut. Measurements showed no significant change in power delivered or accuracy of the shooting when using a string made of human hair. These experiments showed the possibility of using human hair to repair a bowstring."

Brilliant! I've always wanted to know that.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

So begins Men of Terror: A Comprehensive Analysis of Viking Combat by William R. Short and Reynir A. Óskarson.

Emphasis on the "comprehensive." If you have any interest in Viking Age weapons or fighting techniques, or are curious if the heroes in the Icelandic Sagas could really have performed their heroic feats, this 350-page, 2-column book is the one to reach for.

It's got everything (with one exception, which we'll get to later): the Viking mindset, shields and armor, battle tactics, raiding and dueling...

Sax, axe, sword, spear, bow and arrows: Short and Óskarson describe each weapon in great detail--enough that you can make one, if you have the skills and materials--and give copious examples from the sagas, myths, and other literary sources of how each weapon was used and thought of. Numerous illustrations and charts complement their descriptions.

But what really makes Men of Terror stand out from similar books on Viking Age weaponry are the sections on the "physics of" each weapon.

The long, single-edged knife called a sax (or, less correctly, a scramasax), for example, is "a robust, trusty weapon." Designed for hacking (not stabbing), a sax, compared to a sword, is "less likely to break or fail when abused."

But it takes more raw strength to kill with a sax.

Here's why: "Compared to other cutting weapons such as the axe and sword, the sax is generally shorter and lighter, with most of the mass distributed closer to the hand than to the tip. A computer model of the weapon shows the smaller effective mass at the contact point and the lower linear velocities at impact together result in less energy delivered to the target when cutting with a sax compared to cutting with an axe or a sword, all other things being equal. Measurements confirm the model. The energy delivered by a replica sax to a target measured about 40 percent less than the energy delivered by a replica sword, not dissimilar to what the computer model predicted."

Follow the footnotes and you can peer into Short's Viking research studio, Hurstwic, in Massachusetts. There, he and his team attached a three-axis accelerometer to a heavy boxing-type bag (fixed so it couldn't swing). Multiple fighters attacked the target on the bag multiple times, with a replica sax, sword, one-handed axe, and two-handed axe. The data was recorded, checked, averaged, and then compared to a computer model built from the physical parameters of each weapon and how the hand grasps it.

Caption: Scenes from the Hurstwic Facebook page.

Caption: Scenes from the Hurstwic Facebook page. Did I mention Short is a research scientist with a degree from MIT and dozens of patents? His approach to reverse-engineering Viking combat techniques, he explains, is to "create a hypothesis that can be tested" and then to test it again and again. If you want data, this book has it.

The physics of the sax may explain why saxes are so rare in Viking sources. Archaeologists in Norway, for example, count 130 swords for every sax they find and, according to Short's own calculations, "only about 6 percent of the attacks in the [Icelandic Family] sagas are made with saxes." Perhaps also, he and Óskarson speculate, "it is for this reason that saxes were the prized weapon of jötnar (giants), ghosts, and men who had the strength of a giant."

Strength was also the deciding factor, Short and Óskarson argue, in wrestling or "empty-hand combat." In the sagas, this type of fighting is called glíma or fang. It is "the only combative activity alive today that holds a documented, nearly unbroken line that can be traced back to the Vikings," they say, but warn that the art has changed. "In the Viking Age, strength and power were valued in a wrestler," they argue, "but in modern glíma, finesse, agility, and beauty are what is most prized."

Viking fang "was a test of a man’s strength in a society that placed a premium on strength." It was the sport of Thor, the strongest of the gods.

As such, it "gives us clues about the mindset of the Vikings in combat," say Short and Óskarson. Wrestlers "need to be constantly on alert." They need to act "with 100 percent determination.... A warrior who has as his basis or foundation an aggressive, power-based wrestling would stand differently than a warrior who has as his basis a more technical system of wrestling or a striking art. A fighter’s lowering his center of gravity and adhering strictly to the most functional way to keep his balance gives us clues as to how he would stand in a combative situation.... The core of fang centered on raw power, swift movement, and cunning."

Some readers (like me) may have been annoyed by the sexist language in these quotations from

Men of Terror

. They are not a mistake.

Men of Terror

is a book-length argument against my thesis, in

The Real Valkyrie

, that women could be warriors in the Viking Age. Despite the fact that Thor's opponent in his famous wrestling match (as Short and Óskarson do point out) is a woman--the old giant woman Elli, a personification of old age--they believe Viking warriors were men: "men of terror."

Some readers (like me) may have been annoyed by the sexist language in these quotations from

Men of Terror

. They are not a mistake.

Men of Terror

is a book-length argument against my thesis, in

The Real Valkyrie

, that women could be warriors in the Viking Age. Despite the fact that Thor's opponent in his famous wrestling match (as Short and Óskarson do point out) is a woman--the old giant woman Elli, a personification of old age--they believe Viking warriors were men: "men of terror." Their book's title comes from a runestone cited and translated in the Samnordisk rune-text database. It begins: "Ástráðr and Hildungr raised this stone in memory of Fraði, their kinsmen. And he was then the terror of men."

The word translated as "of men" is vera. This word can also mean "of people." It is used, for example, in veröld, which means “world,” with öld meaning “time” or “age.” Thus veröld literally means “the age of humans” or “the time of humans,” i.e. what we now call the anthropocene. Ver is also used in compounds like Oddaverjar, or “people/family of Oddi.” You wouldn’t translate ver today to mean only masculine humans. It refers to all people--which is what “men” used to mean when the first translations from Old Norse to English were made, as in “good will to all men."

So instead of "Men of Terror," I would call Short and Óskarson's book, "People of Terror"--or would I?

Let's not be ridiculous. A title is a marketing tool, and "Men of Terror" is much catchier.

In Men of Terror , Short and Óskarson are simply focusing on men like I focused on women in The Real Valkyrie . Not to exclude the other sex, but to zero in on this particular elite cohort of Viking Age people: men of terror, i.e. professional male warriors with the strength of giants.

Short and Óskarson don’t need to talk about women warriors—I did that (and Short knows it; he even gave me a nice blurb for the book cover). They also don’t talk about male craftsmen or farmers or old men or boys, etc. Their focus is on what made these particular men terrible. If writing books about exceptional Viking women is justified, so is writing books about exceptional Viking men.

Men of Terror is a rich and stimulating--and yes, comprehensive!--look at one important aspect of life in the Viking Age. It deserves to be a classic.

To leave you with one last example of the many quirky questions the book answers, do you remember the episode in Njal's Saga where Gunnar is using his bow to fend off the enemies encircling his house when his bowstring breaks? He asks his wife for two strands of her beautiful long hair to braid into a bowstring, and she refuses--dooming him to death.

Could that have worked? Can you make a bowstring out of human hair? Flip to page 120 of Men of Terror and read: "The feasibility of using human hair was tested in our research lab by gathering hair, twisting it into a string, and splicing it into a conventional bowstring that had been cut. Measurements showed no significant change in power delivered or accuracy of the shooting when using a string made of human hair. These experiments showed the possibility of using human hair to repair a bowstring."

Brilliant! I've always wanted to know that.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on October 06, 2021 08:07

September 29, 2021

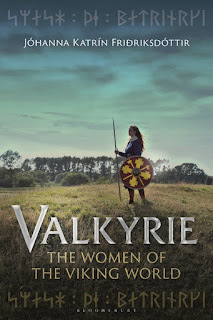

Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World

In the classic "raiders vs. traders" approach to Viking history, women hardly got a mention. They stayed home and looked after the farm (with all that entails) while the men went off on adventures. In the 1990s, three books by Judith Jesch and Jenny Jochens brought the lives of these women out of the shadows, showing how vital their role was, both economically (as weavers of cloth) and socially (as keepers of traditions).

In Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World , published in 2020, Jóhanna Kristín Friðriksdóttir brings these early studies up to date, incorporating the recent archaeological studies that have shifted, or reinforced, our understanding of Viking women’s lives.

Jóhanna is an excellent storyteller, and she knows her material. She wants to introduce us, she says, “to the diverse and fascinating texts recorded in medieval Iceland, a culture able to imagine women in all kinds of roles carrying power, not just in this world but … as pulling the strings in the otherworld, too.”

Jóhanna is an excellent storyteller, and she knows her material. She wants to introduce us, she says, “to the diverse and fascinating texts recorded in medieval Iceland, a culture able to imagine women in all kinds of roles carrying power, not just in this world but … as pulling the strings in the otherworld, too.”

With her mastery of details from the Icelandic sagas, Friðriksdóttir follows ordinary Viking women through the life cycle, from birth to death. She tells stories of women who are bold and successful, but also of those who are battered and victimized.

She tells stories of some of my favorite saga women, such as Gudríðr Þorbjarnardóttir, whom Jóhanna describes as "wife, leader, traveller, mother, Christian ... the Viking woman embodied." Gudríðr, who explored North America 500 years before Columbus, is the subject of my books The Far Traveler and The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler .

She tells about Hallgerðr, who "was beautiful and tall, with hair as fine as silk" and "the eyes of a thief." Her "strong sense of self-worth" and turbulent marriage result in one of the most memorable scenes in the sagas, when her husband breaks his bowstring and she refuses him a lock of hair to fashion into a new one. His enemies kill him while she stands by, and "the episode leaves us wondering whether things could have been different," Jóhanna writes. "The saga offers no answers, but it does tell us that the Icelanders kept alive the debate ... about how to balance the conflicting demands created by marriage and close male friendship."

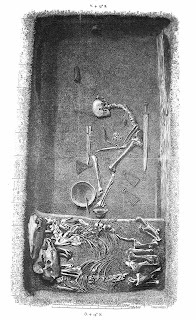

Jóhanna also grapples with the woman at the heart of my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Woman , and supplies a contradictory--and balancing--approach to mine. Discussing the DNA analysis that found the skeleton buried in grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden--long considered to be the ultimate Viking warrior burial--to be female, Jóhanna asks, "Now that the person who once lay in the Birka grave has been proven to have been biologically female, what do we do with this information?"

She answers that question one way, I choose another, but both deserve to be heard. It's time for Viking scholars and enthusiasts to accept that there would be no Vikings (or any other people) without women and to begin to investigate women’s lives as thoroughly as those of men.

To understand the lives of women in the Viking Age, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World by Jóhanna Kristín Friðriksdóttir (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020) is an excellent place to start.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

In Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World , published in 2020, Jóhanna Kristín Friðriksdóttir brings these early studies up to date, incorporating the recent archaeological studies that have shifted, or reinforced, our understanding of Viking women’s lives.

Jóhanna is an excellent storyteller, and she knows her material. She wants to introduce us, she says, “to the diverse and fascinating texts recorded in medieval Iceland, a culture able to imagine women in all kinds of roles carrying power, not just in this world but … as pulling the strings in the otherworld, too.”

Jóhanna is an excellent storyteller, and she knows her material. She wants to introduce us, she says, “to the diverse and fascinating texts recorded in medieval Iceland, a culture able to imagine women in all kinds of roles carrying power, not just in this world but … as pulling the strings in the otherworld, too.” With her mastery of details from the Icelandic sagas, Friðriksdóttir follows ordinary Viking women through the life cycle, from birth to death. She tells stories of women who are bold and successful, but also of those who are battered and victimized.

She tells stories of some of my favorite saga women, such as Gudríðr Þorbjarnardóttir, whom Jóhanna describes as "wife, leader, traveller, mother, Christian ... the Viking woman embodied." Gudríðr, who explored North America 500 years before Columbus, is the subject of my books The Far Traveler and The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler .

She tells about Hallgerðr, who "was beautiful and tall, with hair as fine as silk" and "the eyes of a thief." Her "strong sense of self-worth" and turbulent marriage result in one of the most memorable scenes in the sagas, when her husband breaks his bowstring and she refuses him a lock of hair to fashion into a new one. His enemies kill him while she stands by, and "the episode leaves us wondering whether things could have been different," Jóhanna writes. "The saga offers no answers, but it does tell us that the Icelanders kept alive the debate ... about how to balance the conflicting demands created by marriage and close male friendship."

Jóhanna also grapples with the woman at the heart of my book The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Woman , and supplies a contradictory--and balancing--approach to mine. Discussing the DNA analysis that found the skeleton buried in grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden--long considered to be the ultimate Viking warrior burial--to be female, Jóhanna asks, "Now that the person who once lay in the Birka grave has been proven to have been biologically female, what do we do with this information?"

She answers that question one way, I choose another, but both deserve to be heard. It's time for Viking scholars and enthusiasts to accept that there would be no Vikings (or any other people) without women and to begin to investigate women’s lives as thoroughly as those of men.

To understand the lives of women in the Viking Age, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World by Jóhanna Kristín Friðriksdóttir (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020) is an excellent place to start.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on September 29, 2021 08:00

September 22, 2021

Did Vikings Get Seasick?

I get seasick. Really seasick. So to write about sailing a Viking ship, as I've done extensively in my new book,

The Real Valkyrie

, as well as in my earlier books about Gudrid the Far-Traveler's exploration of North America around the year 1000, I didn't try to recreate a Viking voyage.

I get seasick. Really seasick. So to write about sailing a Viking ship, as I've done extensively in my new book,

The Real Valkyrie

, as well as in my earlier books about Gudrid the Far-Traveler's exploration of North America around the year 1000, I didn't try to recreate a Viking voyage. Sure, I got on Viking ships. I rowed the Viking fishing boat Kraka Fyr in Roskilde harbor. (You can read about that adventure here.)

And I tooled around the harbor of Newport, Rhode Island in Gaia, a replica of the Gokstad ship. (See "A Viking Ship at Midnight," here.)

But mostly, I visited Viking ships in museums and read books by and about other people who had tried to recreate voyages in replica Viking ships.

One of my favorite passages is from Hodding Carter's A Viking Voyage: In which an unlikely crew of adventurers attempts an epic journey to the New World. (Really, the subtitle tells you all you need to know.) This scene (greatly abbreviated here) takes place just before their replica knarr, called Snorri, had to be towed back to Greenland by the Coast Guard Canada.

Writes Carter: "Each swell that rocked Snorri, each wave that slapped her across the sheer plank and sprayed over the foredeck--I cherished them all. We were finally attempting something ancient. We had left the safety net of land and civilization. For the Vikings, this had been THE moment ... I felt unbound. 'This is THE MOMENT,' I kept telling myself. I suddenly fell in love not only with sailing but also with the ocean. I liked being at its mercy. ... The water shifted colors again and again. ... Sounds competed for attention. ... I could not sleep that night. ... I knew then why Leif and the others sailed west--not for wood or new land, but merely to feel so much at once. ... By seven the next evening we were more than 130 miles from Greenland, adrift. All that bashing and groaning I had so cherished had taken its toll. Some of the crew were falling apart. Rob was retching wherever he stood. Others were nearly as sick. Snorri was faring even worse. Our huge rudder had loosened a supporting crossbeam, a thigh-thick piece of wooden framing, by constantly pulling forward on it, instantly creating four holes in the bottom of the boat. Water gushed in..."

No need to read farther, I thought. I'm not going to cross an ocean on a Viking ship. Not me.

Several years later, between the publication of The Far Traveler (2007) and that of my YA novel based on that research, The Saga of Gudrid the Far-Traveler (2015), I had the good fortune to meet the retching Rob of Carter's story. When I asked him about his seasickness, he laughed it off. “Great way to lose 40 or 50 pounds.” (You can read more about Rob Stevens, the boatbuilder who built the knarr replica for Carter, .)

As I said then, I would rather fall off a horse (and I have, repeatedly; read about that here) than be seasick.

But from what archaeologists reexamining the Gokstad ship discovered recently, it seems the bigger hazard for a sailor on a Viking ship was getting bored.

Photo caption: Hanne Lovise Aannestad of the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo points at the footprint on a board of the Gokstad ship. The footprint is enhanced by Science Nordic (photo by Hanne Jakobsen/Per Byhring)

Photo caption: Hanne Lovise Aannestad of the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo points at the footprint on a board of the Gokstad ship. The footprint is enhanced by Science Nordic (photo by Hanne Jakobsen/Per Byhring)According to a 2013 story in Science Nordic, carved into the original floorboards of this Viking ship buried in about 900 in the blue clay of southern Norway are two footprints. They were discovered in 2009, when museum workers were preparing to transfer the floorboards into a new exhibit space.

"My guess is that some time or another a person was bored and simply traced his foot with his knife. It's a kind of an 'I was here' message," researcher Hanne Lovise Aannestad of the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo told Science Nordic.

The footprints are quite small--smaller than Aannestad's--perhaps a girl's? The more distinct of the two prints is a right foot, bare. It even includes toenails. A weaker outline of a left foot appears on another plank. Was it the same girl's? Since the loose floorboards were scattered when the ship was excavated, it's impossible to say. So there might have been two bored young people on the Gokstad ship.

Or maybe they were trying to take their minds off being seasick.

To learn how I used those footprints to tell the story of a warrior woman sailing to Birka in the 10th century, see Chapter 13 of my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

. To learn more about the book, see the previous posts on this blog (here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

To learn how I used those footprints to tell the story of a warrior woman sailing to Birka in the 10th century, see Chapter 13 of my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

. To learn more about the book, see the previous posts on this blog (here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on September 22, 2021 08:00

September 15, 2021

The Science Behind the Real Valkyrie

What does the Viking world look like if we abandon our ideas of gender? What does it look like if roles are assigned, not according to concepts of male versus female, but based on ambition, ability, family ties, and wealth?

In my new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , I reread medieval texts and reexamine archaeological finds with these questions in mind. I use what my research uncovers to re-create the world of one warrior woman in the Viking Age.

As I've written earlier on this blog (click here to read "The Story Behind the Real Valkyrie"), The Real Valkyrie is inspired by "A Female Viking Warrior Confirmed by Genomics," published in 2017 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, Neil Price, and their colleagues, and by their follow-up paper in Antiquity in 2019.

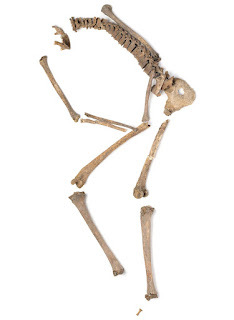

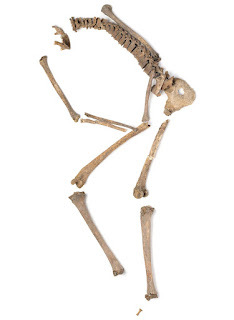

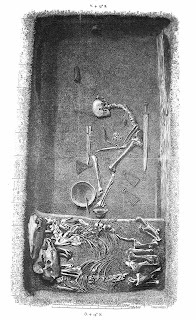

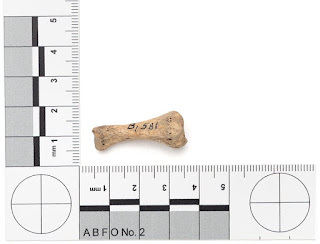

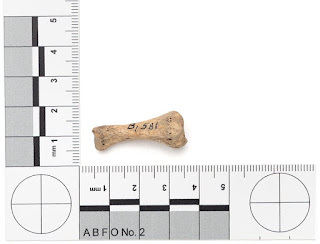

The warrior whose bones they analyze was taken in 1878 from grave Bj581 in the town of Birka, Sweden, a rich weapons-grave long thought to be the ultimate Viking warrior burial.

We don’t know the name of this valkyrie, so I’ve given her one: I call her Hervor, after the warrior woman in a classic Old Norse poem. Her means “battle.” Vör means “aware.” Hervor, then, means Aware of Battle, or Warrior Woman.

What can modern science reveal about her? Her bones and teeth tell us Hervor was 30 to 40 when she died. She ate well all her life, which means she came from a rich family, if not a royal one. At over 5 foot 7, she was taller than most people around her: 5 foot 5 was the average height of a man in 10th century Scandinavia.

What can modern science reveal about her? Her bones and teeth tell us Hervor was 30 to 40 when she died. She ate well all her life, which means she came from a rich family, if not a royal one. At over 5 foot 7, she was taller than most people around her: 5 foot 5 was the average height of a man in 10th century Scandinavia.

The chemistry of her teeth tell us that she was not a native of Birka, where she was buried, but came from somewhere in southern Sweden or Norway. She sailed from there, before she was eight, but did not arrive in Birka until she was over 16.

What was she like? Where did she travel? If all I had were her bones, I could only wonder. But I can also study what was buried with her.

She was seated in her grave surrounded by weapons. None of them are fancy. None are simply for show.

She was seated in her grave surrounded by weapons. None of them are fancy. None are simply for show.

Her two-edged sword is a type rare in Norway and Sweden, but more often found along the Vikings' East Way, the trade route through what is now Russia and Ukraine to Byzantium and beyond.

Her long, thin-bladed scramasax, in its elaborate bronze-and-silver ornamented sheath, is also eastern, inspired by the equipment of the Magyar horse archers who harassed the Vikings along the East Way.

Hervor was an archer too, and may have shot from horseback. Only 18 graves at Birka contain a horse—and she has two, both with bridles. Her iron stirrups are all that remain of her saddle.

By her side were 25 armor-piercing arrows. Between the arrows and her scramasax was a bare spot the right shape for a bow, which had disintegrated. It may have been a Magyar bow—the distinctive metal rings and fittings of Magyar bow cases and quivers were recovered from other Birka graves. Magyar bows were composites of wood, sinew, and horn, bent into a reflex shape. Small and handy on horseback, they shot twice as far as an ordinary wooden bow.

But Hervor was not solely a mounted archer. She was buried with almost every Viking weapon known: sword, scramasax, arrows and bow, axe, two spears, and two shields.

She was buried with more weapons than any other warrior in Birka—more than almost every Viking in the world. Of those Vikings found buried with any weapons at all, 61% have one weapon; only 15% have three or more.

A final touch elevates her rank from warrior to war leader: the full set of pieces for the board game hnefatafl, or Viking chess, that was placed in her lap. From the Roman Iron Age through the high medieval era, from Iceland to Africa to Japan, the combination of game pieces, weapons, and horses in a grave has indicated a war leader. Game pieces symbolize authority and a "flair for strategic thinking," experts say. They express the idea that success in warfare does not depend on strength alone, but also on tactical skill and good luck.

What did Hervor wear? Based on what little remains of her clothing, Hervor dressed like the other Birka warriors in the 10th century. They affected an urban style, distinctive to the fortress towns along the East Way. It was a mixture of Viking, Slavic, steppe-nomadic, and Byzantine fashion, as can be seen in this drawing commissioned by Neil Price and his colleagues.

What did Hervor wear? Based on what little remains of her clothing, Hervor dressed like the other Birka warriors in the 10th century. They affected an urban style, distinctive to the fortress towns along the East Way. It was a mixture of Viking, Slavic, steppe-nomadic, and Byzantine fashion, as can be seen in this drawing commissioned by Neil Price and his colleagues.

Under a classic Viking cloak, clasped with a ring-shaped iron pin at one shoulder, Hervor wore a nomad's kaftan. It might have been made of Byzantine silk: In her grave was a scrap of fabric woven from silk and silver threads. It might have been decorated with mirrored sequins, a scattering of which were also found in her grave.

On her head she wore a silk cap, topped by a filigreed silver cone. Only the cone and a scrap of silk remain of Hervor's cap, but an exact match for her cap's cone was buried with another Birka warrior. A third matching cone was buried with a warrior near Kyiv.

Who was this valkyrie buried in grave Bj581? To tell Hervor's story, I had to make assumptions. I had to connect the dots.

Her bones say she lived to be 30 or 40. Archaeologists can rarely date their finds within a span of 30 years. The items in her grave suggest she died when Birka was at its height and its connections to the East Way were strongest.

The location of her grave implies she was buried after the Warrior's Hall was built for Birka's garrison, between 930 and 950, but before it burned down, between 965 and 985. To tell the best story, I've guessed Hervor was buried a little after 960 and born around 930.

Where was she born? Science tells me only that she came from southern Sweden or Norway. Looking at the Viking world from a warrior woman's point of view, I've opted for Vestfold. Here, a hundred years before Hervor's birth, two powerful women were buried in the most lavish Viking grave ever uncovered, the Oseberg ship mound.

Here, when Hervor was a child, the great hall guarding the cosmopolitan town of Kaupang was destroyed—perhaps by Eirik Bloodaxe and Gunnhild Mother-of-Kings, who conquered Vestfold around that time.

Where would a small girl, born in Kaupang to a rich family, if not royal, end up? Science suggests she went west, possibly to the British Isles—as did Eirik and Gunnhild sometime between 935 and 946, having lost Norway's throne. From their base in the Orkney islands, the royal pair meddled in the politics of Dublin and York.

I don't know how or when Hervor arrived in Birka. But she did arrive sometime in the mid-900s and was buried there as a war leader. Before her death, I imagine she traveled on the East Way from Birka to Kyiv and back, assuming Kyiv is where she got the silver cone for her silk cap.

Besides my conjectural outline of Hervor's life, what links Dublin and York to Kaupang, Birka, and Kyiv? The Viking slave trade, through which young men and women were exchanged for Byzantine silk and Arab silver.

Besides my conjectural outline of Hervor's life, what links Dublin and York to Kaupang, Birka, and Kyiv? The Viking slave trade, through which young men and women were exchanged for Byzantine silk and Arab silver.

In Kyiv, Hervor may have met Queen Olga, who ruled the Vikings, or Rus, from 945 until 957. Her story, once labeled “picturesque” and “legendary,” has been proved by archaeologists to “contain a core of historical truth.”

What I learned researching The Real Valkyrie leads me to believe there is also a core of truth in the account of a battle between the Rus and the Byzantine (or Roman) army in 971. As the victors were "robbing the corpses," wrote John Skylitzes in his Synopsis of Byzantine History a hundred years later, “they found women lying among the fallen, equipped like men; women who had fought against the Romans together with the men.”

Our Hervor was not among them. She had already been buried, surrounded by weapons, in Birka grave Bj581. But as Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson and her colleagues write, Bj581 “suggests to us that at least one Viking Age woman adopted a professional warrior lifestyle. We would be very surprised if she was alone in the Viking world.” So would I.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

In my new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women , I reread medieval texts and reexamine archaeological finds with these questions in mind. I use what my research uncovers to re-create the world of one warrior woman in the Viking Age.

As I've written earlier on this blog (click here to read "The Story Behind the Real Valkyrie"), The Real Valkyrie is inspired by "A Female Viking Warrior Confirmed by Genomics," published in 2017 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, Neil Price, and their colleagues, and by their follow-up paper in Antiquity in 2019.

The warrior whose bones they analyze was taken in 1878 from grave Bj581 in the town of Birka, Sweden, a rich weapons-grave long thought to be the ultimate Viking warrior burial.

We don’t know the name of this valkyrie, so I’ve given her one: I call her Hervor, after the warrior woman in a classic Old Norse poem. Her means “battle.” Vör means “aware.” Hervor, then, means Aware of Battle, or Warrior Woman.

What can modern science reveal about her? Her bones and teeth tell us Hervor was 30 to 40 when she died. She ate well all her life, which means she came from a rich family, if not a royal one. At over 5 foot 7, she was taller than most people around her: 5 foot 5 was the average height of a man in 10th century Scandinavia.

What can modern science reveal about her? Her bones and teeth tell us Hervor was 30 to 40 when she died. She ate well all her life, which means she came from a rich family, if not a royal one. At over 5 foot 7, she was taller than most people around her: 5 foot 5 was the average height of a man in 10th century Scandinavia. The chemistry of her teeth tell us that she was not a native of Birka, where she was buried, but came from somewhere in southern Sweden or Norway. She sailed from there, before she was eight, but did not arrive in Birka until she was over 16.

What was she like? Where did she travel? If all I had were her bones, I could only wonder. But I can also study what was buried with her.

She was seated in her grave surrounded by weapons. None of them are fancy. None are simply for show.

She was seated in her grave surrounded by weapons. None of them are fancy. None are simply for show. Her two-edged sword is a type rare in Norway and Sweden, but more often found along the Vikings' East Way, the trade route through what is now Russia and Ukraine to Byzantium and beyond.

Her long, thin-bladed scramasax, in its elaborate bronze-and-silver ornamented sheath, is also eastern, inspired by the equipment of the Magyar horse archers who harassed the Vikings along the East Way.

Hervor was an archer too, and may have shot from horseback. Only 18 graves at Birka contain a horse—and she has two, both with bridles. Her iron stirrups are all that remain of her saddle.

By her side were 25 armor-piercing arrows. Between the arrows and her scramasax was a bare spot the right shape for a bow, which had disintegrated. It may have been a Magyar bow—the distinctive metal rings and fittings of Magyar bow cases and quivers were recovered from other Birka graves. Magyar bows were composites of wood, sinew, and horn, bent into a reflex shape. Small and handy on horseback, they shot twice as far as an ordinary wooden bow.

But Hervor was not solely a mounted archer. She was buried with almost every Viking weapon known: sword, scramasax, arrows and bow, axe, two spears, and two shields.

She was buried with more weapons than any other warrior in Birka—more than almost every Viking in the world. Of those Vikings found buried with any weapons at all, 61% have one weapon; only 15% have three or more.

A final touch elevates her rank from warrior to war leader: the full set of pieces for the board game hnefatafl, or Viking chess, that was placed in her lap. From the Roman Iron Age through the high medieval era, from Iceland to Africa to Japan, the combination of game pieces, weapons, and horses in a grave has indicated a war leader. Game pieces symbolize authority and a "flair for strategic thinking," experts say. They express the idea that success in warfare does not depend on strength alone, but also on tactical skill and good luck.

What did Hervor wear? Based on what little remains of her clothing, Hervor dressed like the other Birka warriors in the 10th century. They affected an urban style, distinctive to the fortress towns along the East Way. It was a mixture of Viking, Slavic, steppe-nomadic, and Byzantine fashion, as can be seen in this drawing commissioned by Neil Price and his colleagues.

What did Hervor wear? Based on what little remains of her clothing, Hervor dressed like the other Birka warriors in the 10th century. They affected an urban style, distinctive to the fortress towns along the East Way. It was a mixture of Viking, Slavic, steppe-nomadic, and Byzantine fashion, as can be seen in this drawing commissioned by Neil Price and his colleagues. Under a classic Viking cloak, clasped with a ring-shaped iron pin at one shoulder, Hervor wore a nomad's kaftan. It might have been made of Byzantine silk: In her grave was a scrap of fabric woven from silk and silver threads. It might have been decorated with mirrored sequins, a scattering of which were also found in her grave.

On her head she wore a silk cap, topped by a filigreed silver cone. Only the cone and a scrap of silk remain of Hervor's cap, but an exact match for her cap's cone was buried with another Birka warrior. A third matching cone was buried with a warrior near Kyiv.

Who was this valkyrie buried in grave Bj581? To tell Hervor's story, I had to make assumptions. I had to connect the dots.

Her bones say she lived to be 30 or 40. Archaeologists can rarely date their finds within a span of 30 years. The items in her grave suggest she died when Birka was at its height and its connections to the East Way were strongest.

The location of her grave implies she was buried after the Warrior's Hall was built for Birka's garrison, between 930 and 950, but before it burned down, between 965 and 985. To tell the best story, I've guessed Hervor was buried a little after 960 and born around 930.

Where was she born? Science tells me only that she came from southern Sweden or Norway. Looking at the Viking world from a warrior woman's point of view, I've opted for Vestfold. Here, a hundred years before Hervor's birth, two powerful women were buried in the most lavish Viking grave ever uncovered, the Oseberg ship mound.

Here, when Hervor was a child, the great hall guarding the cosmopolitan town of Kaupang was destroyed—perhaps by Eirik Bloodaxe and Gunnhild Mother-of-Kings, who conquered Vestfold around that time.

Where would a small girl, born in Kaupang to a rich family, if not royal, end up? Science suggests she went west, possibly to the British Isles—as did Eirik and Gunnhild sometime between 935 and 946, having lost Norway's throne. From their base in the Orkney islands, the royal pair meddled in the politics of Dublin and York.

I don't know how or when Hervor arrived in Birka. But she did arrive sometime in the mid-900s and was buried there as a war leader. Before her death, I imagine she traveled on the East Way from Birka to Kyiv and back, assuming Kyiv is where she got the silver cone for her silk cap.

Besides my conjectural outline of Hervor's life, what links Dublin and York to Kaupang, Birka, and Kyiv? The Viking slave trade, through which young men and women were exchanged for Byzantine silk and Arab silver.

Besides my conjectural outline of Hervor's life, what links Dublin and York to Kaupang, Birka, and Kyiv? The Viking slave trade, through which young men and women were exchanged for Byzantine silk and Arab silver. In Kyiv, Hervor may have met Queen Olga, who ruled the Vikings, or Rus, from 945 until 957. Her story, once labeled “picturesque” and “legendary,” has been proved by archaeologists to “contain a core of historical truth.”

What I learned researching The Real Valkyrie leads me to believe there is also a core of truth in the account of a battle between the Rus and the Byzantine (or Roman) army in 971. As the victors were "robbing the corpses," wrote John Skylitzes in his Synopsis of Byzantine History a hundred years later, “they found women lying among the fallen, equipped like men; women who had fought against the Romans together with the men.”

Our Hervor was not among them. She had already been buried, surrounded by weapons, in Birka grave Bj581. But as Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson and her colleagues write, Bj581 “suggests to us that at least one Viking Age woman adopted a professional warrior lifestyle. We would be very surprised if she was alone in the Viking world.” So would I.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on September 15, 2021 08:00

September 8, 2021

The Truth About Women Warriors

Anyone who shares my interest in the "female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics" buried in grave Bj581 in Birka, Sweden (the topic of my new book,

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

) needs to read

Warrior Women: An Unexpected History

by Pamela Toler.

Bj581 gets a couple of pages. The thousands of other historical warrior women Toler finds hiding in plain sight will blow your mind.

Did I like this book? After I read it, I ordered two more copies for friends.

Women Warriors: An Unexpected History

is bold, brash, witty, and cutting--and deservedly so. "After you read enough variations of historians arguing why a particular woman warrior didn't exist or fight," Toler explains, "you grow a bit cynical." Of the notion that "women are natural pacifists" because they give birth, she notes, "At its simplest, this argument is based on a series of assumptions about the relative natures of men and women that is unflattering to both. It is also counterhistorical."

Women Warriors: An Unexpected History

is bold, brash, witty, and cutting--and deservedly so. "After you read enough variations of historians arguing why a particular woman warrior didn't exist or fight," Toler explains, "you grow a bit cynical." Of the notion that "women are natural pacifists" because they give birth, she notes, "At its simplest, this argument is based on a series of assumptions about the relative natures of men and women that is unflattering to both. It is also counterhistorical."

Toler as a writer must have massive, well-organized filing cabinets (whether mental, digital, or actual, I don't know). Since girlhood, she has squirreled away stories about women who are "tough/mouthy/opinionated/different" like Joan of Arc and the women who fought in the Civil War dressed as men. Eventually her "women warrior" file got so fat she felt she had to write a book. She then went looking for women who fought "to avenge their families, defend their homes (or cities or nations), win independence from a foreign power, expand their kingdom's boundaries, or satisfy their ambition" and found that she could, in fact, have written several books.

She settled on a survey. The first woman warriors in her book date from the second millennium BCE: three well-armed women buried in the Caucasus mountains, two with battle scars. The most recent warrior women she mentions are two who completed Ranger School, the US army's elite infantry training program, in 2015; one who completed the Marine Corps infantry officer training program in 2017; and six who earned the Expert Infantryman Badge in 2018--her book came out in 2019.

In between she reports on thousands of other historical warrior women, from vastly different cultures and time periods, organizing their stories into themes. Are these women freaks and social outcasts? No. They are mothers, daughters, widows, queens. Some are socially expected to fight; others break norms and fight in disguise. Repeatedly, Toler skewers the tropes about women being kind, nurturing, peaceful, weak, squeamish, or somehow "other" than men.

"Many people who cheer for the highly sexualized women warriors of popular culture," such as Wonder Woman, she writes, "are less comfortable when confronted with real-life images of camouflage-wearing women with shaved heads at boot camp or Ranger School. In fact, that contrast gets at the heart of much of the long-standing, cross-cultural social discomfort with women warriors—the fear that women who chose to fight will lose their femininity or, conversely, that their presence will 'feminize' the army; thereby rendering it less effective, less aggressive, less serious, or just less. It is an old discussion: when Plato argued that women should be given the same training as men and [be] used in all the same tasks, including training in war, he warned 'we must not be afraid of all the jokes of the kind that the wits will make about such a change in physical and artistic culture, and not least about the women carrying arms and riding horses.'"

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

Why don't we know more about the heroic women in Toler's book? "At some level," she explains, "the disappearance of women warriors is part of our larger tendency to write history as 'his story.'" The problem is particularly acute in the field of military history.

"Both the current appeal of pop cultural heroines and ongoing battles over the role of female soldiers in the modern military assume women who go to war are historical anomalies: Joan of Arc, not G.I. Joan. This position is summed up in military historian John Keegan's magnificently inaccurate claim that "warfare is … the one human activity from which women, with the most insignificant exceptions, have always and everywhere stood apart. … Women have followed the drum, nursed the wounded, tended the field and herded the flocks when the man of the family has followed his leader, have even dug the trenches for men to defend and laboured in the workshops to send them their weapons. Women, however, do not fight … and they never, in any military sense, fight men."

Magnificently inaccurate indeed--and Toler has the facts to prove it. Not only do the women warriors in her book "fight men," they often beat them.

"As long as you focus on one historical figure, or one cluster of women, or on one historical period," Toler concludes, "it is easy to believe any individual woman warrior was indeed an exception who stood outside the norm of her time—created by a national crisis or an anomaly of inheritance—and who consequently stands outside the norm of history as a whole."

But when you look at the sweep of history, as Toler does, you find these "exceptions" become significant indeed. They change our ideas of what it means to be a "man" or a "woman." They enlarge the role models for every little girl who despises frilly pink dresses and chooses horses and toy soldiers over baby dolls.

Writes Toler, "The main thing that struck me when I looked at women warriors across cultures rather than in isolation is how many examples there are and how lightly they sit on our collective awareness. I began with hundreds of examples. I ended with thousands."

Warrior Women: An Unexpected History by Pamela Toler was published by Beacon Press in 2019. I'm pleased to add that Pamela likes my book, recreating the life and times of Bj581, as much as I like hers.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Bj581 gets a couple of pages. The thousands of other historical warrior women Toler finds hiding in plain sight will blow your mind.

Did I like this book? After I read it, I ordered two more copies for friends.

Women Warriors: An Unexpected History

is bold, brash, witty, and cutting--and deservedly so. "After you read enough variations of historians arguing why a particular woman warrior didn't exist or fight," Toler explains, "you grow a bit cynical." Of the notion that "women are natural pacifists" because they give birth, she notes, "At its simplest, this argument is based on a series of assumptions about the relative natures of men and women that is unflattering to both. It is also counterhistorical."

Women Warriors: An Unexpected History

is bold, brash, witty, and cutting--and deservedly so. "After you read enough variations of historians arguing why a particular woman warrior didn't exist or fight," Toler explains, "you grow a bit cynical." Of the notion that "women are natural pacifists" because they give birth, she notes, "At its simplest, this argument is based on a series of assumptions about the relative natures of men and women that is unflattering to both. It is also counterhistorical." Toler as a writer must have massive, well-organized filing cabinets (whether mental, digital, or actual, I don't know). Since girlhood, she has squirreled away stories about women who are "tough/mouthy/opinionated/different" like Joan of Arc and the women who fought in the Civil War dressed as men. Eventually her "women warrior" file got so fat she felt she had to write a book. She then went looking for women who fought "to avenge their families, defend their homes (or cities or nations), win independence from a foreign power, expand their kingdom's boundaries, or satisfy their ambition" and found that she could, in fact, have written several books.

She settled on a survey. The first woman warriors in her book date from the second millennium BCE: three well-armed women buried in the Caucasus mountains, two with battle scars. The most recent warrior women she mentions are two who completed Ranger School, the US army's elite infantry training program, in 2015; one who completed the Marine Corps infantry officer training program in 2017; and six who earned the Expert Infantryman Badge in 2018--her book came out in 2019.

In between she reports on thousands of other historical warrior women, from vastly different cultures and time periods, organizing their stories into themes. Are these women freaks and social outcasts? No. They are mothers, daughters, widows, queens. Some are socially expected to fight; others break norms and fight in disguise. Repeatedly, Toler skewers the tropes about women being kind, nurturing, peaceful, weak, squeamish, or somehow "other" than men.

"Many people who cheer for the highly sexualized women warriors of popular culture," such as Wonder Woman, she writes, "are less comfortable when confronted with real-life images of camouflage-wearing women with shaved heads at boot camp or Ranger School. In fact, that contrast gets at the heart of much of the long-standing, cross-cultural social discomfort with women warriors—the fear that women who chose to fight will lose their femininity or, conversely, that their presence will 'feminize' the army; thereby rendering it less effective, less aggressive, less serious, or just less. It is an old discussion: when Plato argued that women should be given the same training as men and [be] used in all the same tasks, including training in war, he warned 'we must not be afraid of all the jokes of the kind that the wits will make about such a change in physical and artistic culture, and not least about the women carrying arms and riding horses.'"

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

Why don't we know more about the heroic women in Toler's book? "At some level," she explains, "the disappearance of women warriors is part of our larger tendency to write history as 'his story.'" The problem is particularly acute in the field of military history.

"Both the current appeal of pop cultural heroines and ongoing battles over the role of female soldiers in the modern military assume women who go to war are historical anomalies: Joan of Arc, not G.I. Joan. This position is summed up in military historian John Keegan's magnificently inaccurate claim that "warfare is … the one human activity from which women, with the most insignificant exceptions, have always and everywhere stood apart. … Women have followed the drum, nursed the wounded, tended the field and herded the flocks when the man of the family has followed his leader, have even dug the trenches for men to defend and laboured in the workshops to send them their weapons. Women, however, do not fight … and they never, in any military sense, fight men."

Magnificently inaccurate indeed--and Toler has the facts to prove it. Not only do the women warriors in her book "fight men," they often beat them.

"As long as you focus on one historical figure, or one cluster of women, or on one historical period," Toler concludes, "it is easy to believe any individual woman warrior was indeed an exception who stood outside the norm of her time—created by a national crisis or an anomaly of inheritance—and who consequently stands outside the norm of history as a whole."

But when you look at the sweep of history, as Toler does, you find these "exceptions" become significant indeed. They change our ideas of what it means to be a "man" or a "woman." They enlarge the role models for every little girl who despises frilly pink dresses and chooses horses and toy soldiers over baby dolls.

Writes Toler, "The main thing that struck me when I looked at women warriors across cultures rather than in isolation is how many examples there are and how lightly they sit on our collective awareness. I began with hundreds of examples. I ended with thousands."

Warrior Women: An Unexpected History by Pamela Toler was published by Beacon Press in 2019. I'm pleased to add that Pamela likes my book, recreating the life and times of Bj581, as much as I like hers.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on September 08, 2021 08:03

September 1, 2021

Of Bones and Bias

I begin

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

with this sentence: "All I have are her bones."

And I thought, when I began writing it, that this was going to be a book about bones. I was surprised when it turned out to be a book about bias.

In the summer of 2015, I spent a day watching my friend Guðný Zöega excavate a Viking Age graveyard in Iceland. Bones, Guðný told me, were eloquent. They speak of battle wounds and disease. They tell how tall a person was, what she ate, where she came from. Listening to Guðný, I was inspired to write a book about bones and what archaeologists can learn from them.

But, in retrospect, I noticed that a lot of what Guðný did that day was sit and think. She took photos, and made notes. Because once she took the bones from a grave and placed them in a box, no one else would ever see exactly how the skeleton had sat in the soil. Unlike the work of other scientists, hers is not reproducible. That's the problem with archaeology as a science.

But, in retrospect, I noticed that a lot of what Guðný did that day was sit and think. She took photos, and made notes. Because once she took the bones from a grave and placed them in a box, no one else would ever see exactly how the skeleton had sat in the soil. Unlike the work of other scientists, hers is not reproducible. That's the problem with archaeology as a science.

Nobody can repeat the experiment. What's left after an archaeologist finishes digging up a Viking burial are boxes of bones and artifact--and interpretations.

The gender of a burial is one of those interpretations. Archaeologists are taught that a woman's skull is smoother and more rounded. Her long bones are more slender. Her pelvis is shaped differently than a man's. But there’s no absolute scientific scale for "smoother, rounder, and more slender"--or even for pelvic structure, I learned.

Plus, few Viking skeletons are in good shape. After 1000 years in the soil, the bones are degraded, or missing. In cremation burials, the bones were first burned and then crushed before being buried in a pot. Yet archaeologists still sex these graves. How?

DNA sexing is now available. But it's difficult and expensive and, so, still rare.

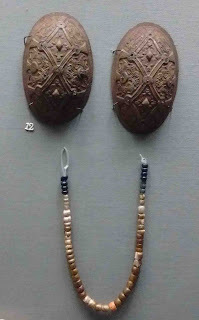

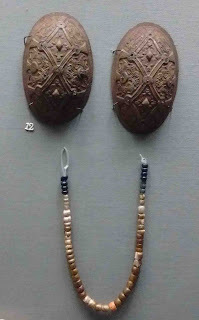

The standard method, I learned, is "sexing by metal": Jewelry for women (especially the oval brooches that hold up the straps of an apron dress). And weapons for men.

It sounds logical. Surely it's based on statistics, right?

It's not. The practice began in 1837, before archaeology as a science even existed. It reflects the values of Victorian society, when women were confined to the home and told to concern themselves only with their children, the church, and the kitchen.

When our image of the Viking world took shape, a warrior woman was as fabulous as a dragon. All weapons-graves were classified as male--and most of them still are.

By accepting the Victorian stereotypes, we legitimize the idea that women should stay at home. We reduce the role models for every modern girl who visits a museum or reads a history book. We make it hard to even imagine a warrior woman like the one buried in grave Bj581 in the Viking town of Birka, Sweden.

Bj581 is the burial at the heart of my book The Real Valkyrie . It was excavated in 1878. Other than one faded drawing and a few notes, all we have are boxes of bones and artifacts with the number "581" inked on them. Most of those artifacts are weapons.

Because of the plethora of weapons in the grave, Bj581 has long been held up as the classic Viking warrior's grave.

In September 2017, a DNA study by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Price and her colleagues confirmed what some specialists had always thought: The bones were female. Interpreting Bj581 as a warrior woman, the researchers list a dozen scholars since 1966 who have labeled Bj581 a warrior's grave. "As far as we are aware, this warrior interpretation has never been challenged," they state, adding, "We strongly followed the same military reading as has been proposed for Bj581 by a long series of archaeological authorities, and for the same sensible reasons that are far from arbitrary. In doing so, we find no problem in adjusting for the new sex determination."

Their critics, however, did have a problem adjusting. They suggest that originally there must have been two people in the grave, a male warrior and his female wife or slave—and that the man has disappeared without a trace, leaving behind only his weapons. Or that the woman was sacrificed and buried in place of a man who died elsewhere. Or that, because she wielded weapons, Bj581 wasn't socially female.

What does the Viking world look like if we abandon the stereotypes? What does it look like if roles are assigned, not according to Victorian concepts of male versus female, but based on ambition, ability, family ties, and wealth? In The Real Valkyrie , I reread texts and reexamine archaeological finds with these questions in mind. I use what my research uncovers to re-create the world of one warrior woman in the Viking Age: the woman buried in Bj581.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

And I thought, when I began writing it, that this was going to be a book about bones. I was surprised when it turned out to be a book about bias.

In the summer of 2015, I spent a day watching my friend Guðný Zöega excavate a Viking Age graveyard in Iceland. Bones, Guðný told me, were eloquent. They speak of battle wounds and disease. They tell how tall a person was, what she ate, where she came from. Listening to Guðný, I was inspired to write a book about bones and what archaeologists can learn from them.

But, in retrospect, I noticed that a lot of what Guðný did that day was sit and think. She took photos, and made notes. Because once she took the bones from a grave and placed them in a box, no one else would ever see exactly how the skeleton had sat in the soil. Unlike the work of other scientists, hers is not reproducible. That's the problem with archaeology as a science.

But, in retrospect, I noticed that a lot of what Guðný did that day was sit and think. She took photos, and made notes. Because once she took the bones from a grave and placed them in a box, no one else would ever see exactly how the skeleton had sat in the soil. Unlike the work of other scientists, hers is not reproducible. That's the problem with archaeology as a science. Nobody can repeat the experiment. What's left after an archaeologist finishes digging up a Viking burial are boxes of bones and artifact--and interpretations.

The gender of a burial is one of those interpretations. Archaeologists are taught that a woman's skull is smoother and more rounded. Her long bones are more slender. Her pelvis is shaped differently than a man's. But there’s no absolute scientific scale for "smoother, rounder, and more slender"--or even for pelvic structure, I learned.

Plus, few Viking skeletons are in good shape. After 1000 years in the soil, the bones are degraded, or missing. In cremation burials, the bones were first burned and then crushed before being buried in a pot. Yet archaeologists still sex these graves. How?

DNA sexing is now available. But it's difficult and expensive and, so, still rare.

The standard method, I learned, is "sexing by metal": Jewelry for women (especially the oval brooches that hold up the straps of an apron dress). And weapons for men.

It sounds logical. Surely it's based on statistics, right?

It's not. The practice began in 1837, before archaeology as a science even existed. It reflects the values of Victorian society, when women were confined to the home and told to concern themselves only with their children, the church, and the kitchen.

When our image of the Viking world took shape, a warrior woman was as fabulous as a dragon. All weapons-graves were classified as male--and most of them still are.

By accepting the Victorian stereotypes, we legitimize the idea that women should stay at home. We reduce the role models for every modern girl who visits a museum or reads a history book. We make it hard to even imagine a warrior woman like the one buried in grave Bj581 in the Viking town of Birka, Sweden.

Bj581 is the burial at the heart of my book The Real Valkyrie . It was excavated in 1878. Other than one faded drawing and a few notes, all we have are boxes of bones and artifacts with the number "581" inked on them. Most of those artifacts are weapons.

Because of the plethora of weapons in the grave, Bj581 has long been held up as the classic Viking warrior's grave.

In September 2017, a DNA study by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Price and her colleagues confirmed what some specialists had always thought: The bones were female. Interpreting Bj581 as a warrior woman, the researchers list a dozen scholars since 1966 who have labeled Bj581 a warrior's grave. "As far as we are aware, this warrior interpretation has never been challenged," they state, adding, "We strongly followed the same military reading as has been proposed for Bj581 by a long series of archaeological authorities, and for the same sensible reasons that are far from arbitrary. In doing so, we find no problem in adjusting for the new sex determination."

Their critics, however, did have a problem adjusting. They suggest that originally there must have been two people in the grave, a male warrior and his female wife or slave—and that the man has disappeared without a trace, leaving behind only his weapons. Or that the woman was sacrificed and buried in place of a man who died elsewhere. Or that, because she wielded weapons, Bj581 wasn't socially female.

What does the Viking world look like if we abandon the stereotypes? What does it look like if roles are assigned, not according to Victorian concepts of male versus female, but based on ambition, ability, family ties, and wealth? In The Real Valkyrie , I reread texts and reexamine archaeological finds with these questions in mind. I use what my research uncovers to re-create the world of one warrior woman in the Viking Age: the woman buried in Bj581.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

For more on my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

, see the previous posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com. Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Published on September 01, 2021 08:00

August 25, 2021

The Magic of Einar Selvik

In August 2018, I went to the Midgardsblot in Borre, Norway. Midgardsblot is a Viking metal music festival. I am not a Viking metal enthusiast, but I needed to visit Norway's ancient kingdoms of Vestfold and Agdir to do research for my book

The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women

.

Borre, in Vestfold, has several grave mounds in their original, unexcavated condition. It has a small museum of Viking archaeology. It has a reconstructed Viking feast hall. And, along with the music festival, its Midgardsblot featured a Viking encampment, with reenactors of many kinds, and a series of lectures on Viking history and lore.

Borre, in Vestfold, has several grave mounds in their original, unexcavated condition. It has a small museum of Viking archaeology. It has a reconstructed Viking feast hall. And, along with the music festival, its Midgardsblot featured a Viking encampment, with reenactors of many kinds, and a series of lectures on Viking history and lore.

I was interested in the music reenactors. Music is associated with rituals in the Icelandic sagas, and those rituals are often associated with women, making them pertinent for my study of the power of women in the Viking Age. So I made sure to get a seat in the tiny lecture hall for the two lectures by musician Einar Selvik of Wardruna.

I knew Einar's music was featured on the History Channel's "Vikings" TV show. But I didn't know what an immersive artist he was.

As he explained, "I try not to climb into trees that don't have roots. I'm a very nerdy person. I read as much as the academics, or maybe more. I try out the theories the scholars put out. I sing in longhouses in front of audiences hungry for this experience. I cultivate and feed on what works in front of an audience." First he researched Viking Age instruments. "Instruments carry within them a lot of limitations," he said. "Whatever you do with them is authentic. The idea is to sow seeds, to make something grow again--not to put it into a museum. I went to museums and archives. I read books. I made a lot of shitty instruments. I didn't want to hear instruments played by other people, I wanted to approach it as a child. This was an initiation for me, a journey."

First he researched Viking Age instruments. "Instruments carry within them a lot of limitations," he said. "Whatever you do with them is authentic. The idea is to sow seeds, to make something grow again--not to put it into a museum. I went to museums and archives. I read books. I made a lot of shitty instruments. I didn't want to hear instruments played by other people, I wanted to approach it as a child. This was an initiation for me, a journey."

He made drums: "I didn't shoot the animal, but I did skin it. I put it in the river until the hair sacs let loose. Then I had the smelly work of cleaning it, but it's beautiful work too, because you're bringing the animal back to life. Every time I beat on that drum, with its own leg, she is there, singing."

He made horns from goat horns, with fingerholes and sometimes with reeds (like an oboe's) out of juniper. He made long birchbark lurs, played like trumpets (the harder you blow, the higher the tone). He made a bowed tail-harp with two horsehair strings, one for the melody and one for the drone. ("This is an instrument that does not always behave," he noted. Like a horse, I might add.)