Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 20

May 30, 2012

Snorri Sturluson, the Homer of the North

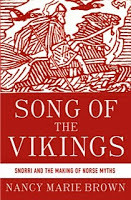

Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths has reached that delightful stage called “advance reader copies,” or ARCs—delightful for the writer because I get to see the final cover design, read my publisher’s description of the book, and (best of all) relish the first readers’ comments, or blurbs.

Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths has reached that delightful stage called “advance reader copies,” or ARCs—delightful for the writer because I get to see the final cover design, read my publisher’s description of the book, and (best of all) relish the first readers’ comments, or blurbs.How Palgrave Macmillan describes Song of the Vikings:“Snorri Sturluson, the thirteenth-century Icelandic chieftain who gave us Odin, Loki, and Thor, was as unruly as the Norse gods he created.

“Much like Greek and Roman mythology, Norse myths are still with us. Famous storytellers from JRR Tolkien to Neil Gaiman have drawn their inspiration from tales of the long-haired, mead-drinking, marauding and pillaging Vikings. Their creator is a thirteenth-century Icelandic chieftain by the name of Snorri Sturluson. Like Homer, Snorri was a bard, collecting and embellishing the folklore and pagan legends of medieval Scandinavia. Unlike Homer, Snorri was a man of the world—a wily political power player. One of the richest men in Iceland, he came close to ruling it and even closer to betraying it… In Song of the Vikings, author Nancy Marie Brown brings Snorri Sturluson’s story to life.”

Graffiti portrait of Snorri in Reykjavik. Photo by Cate Wood.

Graffiti portrait of Snorri in Reykjavik. Photo by Cate Wood.The first blurbs:Jeff Sypeck, author of Becoming Charlemagne, wrote:“For readers who’ve long sensed that older winds blow through the works of their beloved Tolkien, Song of the Vikings is a fitting refresher on Norse mythology. Without stripping these dark tales of their magic, Nancy Marie Brown shows how mere humans shape myths that resonate for centuries—and how one brilliant scoundrel became, for all time, the Homer of the North.”

Scott Weidensaul, author of The First Frontier, said:“In medieval Iceland, one of the most remote corners of the known Earth, a very un-Viking Norseman named Snorri Sturluson crafted the heroic mythology on which rests everything from Wagner’s Ring cycle and the Brothers Grimm to Tolkien (who considered Snorri’s work more central to English literature than Shakespeare’s) and even the evils of Nazism. In Song of the Vikings, Nancy Marie Brown brings to vivid life this age of poetic Viking skalds, of blood feuds and vengeance raids, of royal intrigue and fierce independence, when the barren, beautiful landscape of the North was haunted by trolls, giants, and dragons—all of which Snorri, the most important writer the world ever forgot, captured for eternity.”

Snorri by Gustav Vigeland. At Reykholt.Why are ARCs delightful?Because they got it. “Unruly” is the perfect word to describe Snorri Sturluson and his creations—and I didn’t think of it. “How mere humans shape myths” is an excellent summary of my theme—again, I wish I’d written it. A medieval Icelander influenced Wagner, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, Tolkien, the Nazis—yes, that’s the point I was making, that and the importance of not forgetting a great and influential (if unruly) writer.

Snorri by Gustav Vigeland. At Reykholt.Why are ARCs delightful?Because they got it. “Unruly” is the perfect word to describe Snorri Sturluson and his creations—and I didn’t think of it. “How mere humans shape myths” is an excellent summary of my theme—again, I wish I’d written it. A medieval Icelander influenced Wagner, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, Tolkien, the Nazis—yes, that’s the point I was making, that and the importance of not forgetting a great and influential (if unruly) writer.Song of the Vikings won’t be in bookstores until October, but I’ll be sharing more about it in posts throughout the summer and early fall. Meanwhile, I’m planning my book tour. If you’d like me to visit your library, local bookstore, bookclub, or school, please let me know.

And if you’re lucky enough to attend Book Expo America in New York next week, stop by the Palgrave Macmillan booth and pick up an ARC of Song of the Vikings.

Published on May 30, 2012 07:07

May 23, 2012

The Case of the Butternuts

Where Was the Viking’s Vinland?

The climax of my book The Far Traveler is the story of the Viking expedition to North America led by 19-year-old Gudrid the Far-Traveler and her husband Thorfinn Karlsefni.

Leif Eiriksson discovered the land he named Vinland, or “Wine Land,” in about 999, when he was blown off course on his way home to Greenland after visiting the king of Norway. But Leif never returned to explore this fabulous new land.

His sister-in-law did. Gudrid the Far-Traveler and her first husband, Leif’s younger brother Thorstein, tried to sail to Vinland soon after Leif came home. They ran into storms and were forced back to Greenland. Thorsteinn died, and Gudrid gave up her dream for a while.

Then Thorfinn Karlsefni came to Greenland. Karlsefni was a merchant from Iceland. He wanted to trade for walrus tusks, white falcons, and polar bear skins. Instead, he met Gudrid and fell in love. Gudrid convinced him to go to Vinland. She owned one ship; she hired a crew of Greenlanders. The other two ships were manned by Icelanders, led by Karlsefni.

A Viking ColonyThey crossed the North Atlantic. They sailed south along shore, past mountains and marvelous beaches. They spent the first winter beside a fjord with fierce currents.

Next summer, they sailed south to a wide tidal lagoon. They named it Hóp (pronounced “Hope”), which means “Lagoon.” There Gudrun gave birth to her son Snorri. Hóp had tall trees and a river full of fish. Wild grapes grew abundantly there. It was a richer land than Greenland or Iceland—a good place for a Viking colony.

But soon strangers came to the Vikings’ camp. They were delighted by the taste of milk. They traded furs for strips of red wool cloth. They had never seen an axe—and they wanted one. A fight broke out. The strangers fought with stone-tipped arrows. The Vikings had axes and swords, but they were vastly outnumbered. They abandoned Hóp.

Only one of their ships made it back to Greenland. Gudrid, Karlsefni, and little Snorri sailed on to Iceland, where they built a new home.

Where Was Vinland?Their story was written down about 200 years later in the Icelandic sagas. One version was written by Gudrid’s great-great grandson. Another is linked to her seven-greats granddaughter.

Where Was Vinland?Their story was written down about 200 years later in the Icelandic sagas. One version was written by Gudrid’s great-great grandson. Another is linked to her seven-greats granddaughter. Two hundred years is a long time. Some of the story was exaggerated. Some was forgotten. But some of it is true.

In the 1960s, archaeologists found three Viking longhouses on the tip of Newfoundland, at a place called L’Anse aux Meadows. Each house is big enough for one ship’s crew. Fire-starters made of jasper rock show the Vikings came from both Iceland and Greenland. A spindle whorl proves a Viking woman was with them. Spinning wool into yarn was women’s work in Viking times.

But grapes have never grown in Newfoundland. Why would Leif name this place Wine Land? And where was Hóp, the lagoon with tall trees, fish, grapes, and fierce natives?

The Clue of the ButternutsThree butternuts gave archaeologist Birgitta Wallace the answer.

The Clue of the ButternutsThree butternuts gave archaeologist Birgitta Wallace the answer.Wallace was in charge of the dig at L’Anse aux Meadows from 1975 to 2000. Her workers dug a five-foot-deep trench 200 feet into the bog beside the Viking houses. She sent all the wood and seeds they found to a botanist. She said, “Look for what doesn’t belong here, what’s not here now.”

The botanist told her, “It’s all what you’d imagine. Except what are those butternuts doing there?”

The botanist told her, “It’s all what you’d imagine. Except what are those butternuts doing there?”In three different spots the workers had turned up butternuts. The nuts were in the same layer of soil as rusty nails and chips of wood from a repaired Viking ship.

Butternuts have never grown in Newfoundland. The closest trees are 800 miles south. The nuts couldn’t have floated north. The shore currents in the Gulf of St. Lawrence run the other direction. The only way they could have reached the bog when they did is by Viking ship. The Vikings could have collected butternuts in New Brunswick, New England, or near Quebec. Wallace thinks the Miramichi River valley in New Brunswick has the best claim to being the place Gudrid and Karlsefni named Hóp.

The river’s mouth forms a great tidal lagoon. Its banks are lush with tall butternut trees. Where butternuts grow, grapes are also found. A thousand years ago, the Miramichi River had the richest salmon run in eastern North America. And, because of the fish, the valley was home to the largest population of Native Americans in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The river’s mouth forms a great tidal lagoon. Its banks are lush with tall butternut trees. Where butternuts grow, grapes are also found. A thousand years ago, the Miramichi River had the richest salmon run in eastern North America. And, because of the fish, the valley was home to the largest population of Native Americans in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Could the Vikings have explored farther south? Yes. A replica Viking ship sailed all the way to the Amazon in the summer of 1991. But until we find another longhouse or lost spindle whorl—or clue like the butternuts—we can’t say exactly where Gudrid the Far-Traveler and her husband went when they came to America a thousand years ago.

Links & Photos:The picture of the butternut and of archaeologists excavating the bog at L'Anse aux Meadows come from the website, Canadian Mysteries, http://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/vinland/home/indexen.html

The other photos were taken by Charles Fergus in 2006 while I was researching The Far Traveler.

You can also learn more about the Viking archaeological site on the official Parks Canada L'Anse aux Meadows website, http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows/index.aspx

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in the medieval world.

Published on May 23, 2012 07:09

May 16, 2012

An Icelandic Horse Named “Doubt”

To write The Far Traveler, I volunteered on an archaeological dig in Skagafjörður in northern Iceland. The site was very close to the farm of Syðra-Skörðugil, where in 1997 I bought my first Icelandic horse, Gæska (“Kindness”), one of the stars of my book A Good Horse Has No Color. I’d remained friends with Elvar and Fjóla, Gæska’s breeders, and so one evening, after eight hours on my knees with a trowel, I accepted their invitation for a horseback ride.

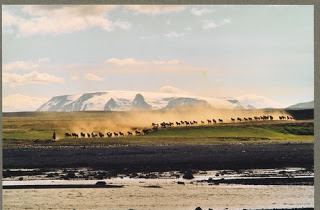

To write The Far Traveler, I volunteered on an archaeological dig in Skagafjörður in northern Iceland. The site was very close to the farm of Syðra-Skörðugil, where in 1997 I bought my first Icelandic horse, Gæska (“Kindness”), one of the stars of my book A Good Horse Has No Color. I’d remained friends with Elvar and Fjóla, Gæska’s breeders, and so one evening, after eight hours on my knees with a trowel, I accepted their invitation for a horseback ride.Our task was to herd a hundred horses up to their summer pastures, where the sheep had been taken two weeks before. Eighteen people gathered at the farm of Syðra-Skörðugil, most of them, like me, just along for the ride. Fjóla had two horses ready for me. The white one, she said, was “a really fine mountain horse.” His name was Vafi, or “Doubt.” The bay was her eight-year-old daughter’s favorite horse. She suggested I start out riding little Ásdís’s horse and leading the white, then switch when we came to the hills.

Riding With the HerdTo gather up the herd and funnel it through the fences, we rode over fields frost-heaved into knee-high grassy hummocks, up steep moss-covered slopes, through thickets of birch and blueberries, over rushing creeks with stony beds. Our pace seemed terrifically fast on such grueling terrain, but no one else seemed to notice.

Our leader, Eyþór, Elvar’s younger brother, rode point to keep the loose horses from going the wrong way. He sat with his legs stretched long, his back straight but soft, as if out for a pleasant amble. His rust-colored jacket and riding cap complemented both his reddish-blond hair and his two bright bay horses, a high-stepping, athletic pair, relaxed on a loose rein, alert to his every thought.

I rode with the herd, horses of all colors around me: some young and gangly, still growing into their legs, others sleek and fit, a few with ugly heads and big Roman noses, others with pretty little dished faces. All were the short, stocky Icelandic breed, the only horse in Iceland since the Viking Age. I could not fix on any one for long, they blurred and flowed and mixed together. Their hooves kicked up dust as they strung out in a line. Their long manes and tails rippled in the wind.

Loose Horse!We changed horses once we entered the mountains, and I was just settling down to enjoy the white horse’s smooth, rolling gait, full of energy—when my mount fell into a mudhole beside a little brook. As he leaped and struggled to get out of the bog (with me hanging on for dear life), my handhorse, little Asdis’s horse, decided to jump the brook. He broke free of my grip, eluded the rider ahead of me, and tore off with the loose herd, his reins dangling. Of course we were beyond the last fence. Ahead stretched only acres of grassland.

At the point where we should have had a rest and returned home, leaving the loose horses to wander further if they wished, Eyþór picked out three people to help me catch little Asdis’s horse. We took off like cowboys, and I realized our earlier pace had not, in fact, been fast.

We jumped across, into, and out of the stream, leaping up steep banks and sliding down off them. We flew across the frost-heaved hummocks at a hand gallop. We followed a narrow sheep track along the side of a hill of scree tumbling toward a cliff at the angle of repose—at a fast trot. We got off to lead the horses through a bog, the red-tinted water glistening between the grass tufts, and though I tried to step on the firmest tussocks I sank well above my ankle boots. We scrambled up one very steep hill to where a group of ten or so horses had stopped to graze, but little Asdis’s horse, unfortunately, was not with them.

We needed to ride faster, Eyþór decided, to get in front of the herd. He could see that the white horse (and I) had had enough by then. The fifth rider had taken a tumble, and his horse had scraped its nose on a rock—a flap of bloody skin was hanging loose, looking awful. Eyþór sent us back, and he and his posse continued on.

Midnight SunsetIt was an hour before we reached our friends, sitting on the grass by the bend of the river, drinking cognac from hipflasks and trying to ignore the biting flies. As we headed home, the midnight sunset painted the tops of the hills blush pink, turning to blood orange, then crimson, like the colors of the peat-ash dumped on the Viking Age house I’d spent the day helping to uncover. A full, pale rainbow arced over the sunlit mountains behind us.

At the first fence we could see all the way down the valley to the fjord, the island of Drangey like a blue block floating between an orange sea and a pink sky, the green fields gone gray in the dusk. One of the riders pulled a cellphone from his pocket and called Eyþór —his posse was just behind us, having snagged little Asdis’s horse easily once they circled ahead of the herd. Except for the cellphone, I could imagine Gudrid the Far-Traveler, the adventurous Viking woman I was writing about, taking part in just this sort of excursion one long summer night a thousand years ago.

A Good HorseWhen we reached the barn at about 2 a.m., Elvar was there, waiting to take care of the horse with the injured nose. “I guess we know the name of your next book.” He grinned: “A Good Horse Lost in the Mountains.”

The next morning John Steinberg, the leader of the archaeological project, kindly gave me a zombie’s job, helping to re-survey the excavation on the farm of Glaumbær, to the centimeter, in five-meter squares. I was to stand still and hold steady the stadia rod, a six-foot pole with a mirror at the top, the target for the Total Station, a glorified surveyor’s transit that measured the distance with laser-beam accuracy and keyed our grid to GPS coordinates.

At noon, Sirri Sigurðardóttir, the curator of the museum on the grounds of Glaumbær, invited us all to celebrate her birthday with a lunch of chowder, rye bread, and cheesecake.

“Did you enjoy your ride last night?” she asked, with a teasing inflection. Apparently the story that I had almost lost “little Ásdís’s favorite horse” was all over Skagafjörður already.

Photos and Links:On the Syðra-Skörðugil website (www.horse.is/index.php?pid=7) you can read all about the amazing horsewoman little Ásdís has grown up to be (if you read Icelandic, that is). All of the photos in this post come from that website.

To learn about Icelandic horses in general, go to The Icelandic Horse Congress at www.icelandics.org or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson's video blog, Hestakaup.com.

The Archaeological Settlement Survey project led by John Steinberg at the University of Massachusetts-Boston has its own blog (http://blogs.umb.edu/sass/) where you can learn about what they’ve been up to since I volunteered in 2006.

For updates on Glaumbær, the last home of Gudrid the Far-Traveler, see the website of the Skagafjörður Heritage Museum (http://www.skagafjordur.is/displayer.asp?cat_id=1065).

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in the medieval world.

Published on May 16, 2012 08:10

May 9, 2012

The Pope’s Abacus

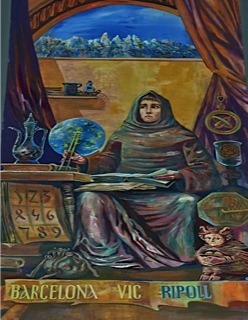

When were Arabic numerals introduced into Western Europe? We used to think it was in the 1100s. But scholars studying the life of Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II in 999, have pushed that date back nearly two centuries.

When were Arabic numerals introduced into Western Europe? We used to think it was in the 1100s. But scholars studying the life of Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II in 999, have pushed that date back nearly two centuries.People usually think of a Chinese abacus when they hear the title of my biography of Gerbert, The Abacus and the Cross: colored beads strung on wires set in a frame. Gerbert’s abacus was nothing like that.

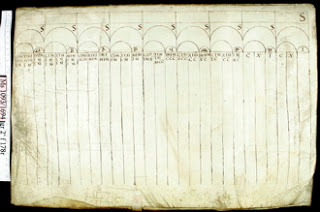

It was a counting board: a grid of 27 columns, painted on a flat surface. Later, merchants found having a counting board like this so useful that they drew them on tabletops, which they called “counters.” That is why we now do business “over the counter.”

Arabic RootsTo learn about Gerbert’s abacus, I visited Charles Burnett, Professor of the History of Islamic Influences in Europe at the Warburg Institute in London. In 2001, Burnett discovered a copy of Gerbert’s abacus. It was a stiff poster-sized sheet of parchment that had been trimmed down and reused in the binding of the Giant Bible made for the abbot of Echternach between 1051 and 1081.

The Bible is owned by the National Library of Luxembourg, which had unbound it in 1940 in order to photograph the pages. The abacus was taken out of the binding and, Burnett told me, “It got put in a box. It got lost in the library for several years. My friend, the librarian of rare books, was tidying up and found the original of the abacus sheet.” Noticing the Arabic numerals along the top, the librarian immediately thought of Burnett, who has been writing about the Arabic roots of mathematics since the 1970s.

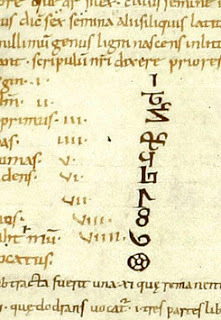

Shortly after Burnett announced his find, a librarian at the State Archives of Trier called with word of a matching copy “written in the same bold capital letters,” Burnett says. It was also made at Echternach. This second abacus was bound into a manuscript along with notes on multiplication and division, the use of fractions, the etymology of the word digit, and a poem on the names of the nine Arabic numerals and zero. These notes can be dated to 993. Burnett writes, “They appear to be written by a single scholar, at different times, who has made frequent erasures and corrections.” Burnett thinks he was one of Gerbert’s students.

How to CalculateTo use his abacus, Gerbert had 1000 apices or markers made out of cow’s horn. They looked something like modern checkers. Each one was marked with an Arabic numeral. To calculate, Gerbert placed the markers on the counting board and shuffled them around. He could get the answer, one of his contemporaries wrote, quicker than you could say it in words.

Using these new Arabic numerals, Gerbert’s abacus introduced the “place-value” method of calculating: The place, or column, where the marker sat determined the value of the number written on it, whether it meant 5 or 50 or 500.

In 2003, Burnett was a visiting professor at the University of California. “When I was teaching in Berkeley, I actually reconstructed Gerbert’s abacus,” he told me. “I found a shop that specialized in games for children. I bought one of these big rolls of paper and these lovely large numbers—they could substitute very well for the apices, I thought. I drew the columns on this paper—not 27 of them. I didn’t get as complicated as all that. It’s perfectly possible to work out how the procedure worked.”

Did Gerbert Use Zero?A zero marker was not strictly necessary—to make 50, you put a 5 in the tens column and leave the ones column blank. But the poem in the Trier manuscript does include a zero, looking like a spoked wheel, so Gerbert may have used it as a placeholder. The idea that zero was an actual number would not arrive until much later.

Did Gerbert Use Zero?A zero marker was not strictly necessary—to make 50, you put a 5 in the tens column and leave the ones column blank. But the poem in the Trier manuscript does include a zero, looking like a spoked wheel, so Gerbert may have used it as a placeholder. The idea that zero was an actual number would not arrive until much later. “In the 1120s,” Burnett explained, “there was a change-over from the abacus to the algorithm. The big change is using pen and paper. Also the sign for zero. So the main difference between the look of Gerbert’s abacus and look of the algorithm is, with the algorithm you don’t actually draw the lines for the columns and you have a zero instead of an empty column.”

For a thousand years, we have added, subtracted, multiplied, and divided essentially the same way Gerbert taught his students at the cathedral of Reims.

Photos & Links:Arabic numerals appear on two pages from the notebook of one of Gerbert’s students, which Burnett dates to c. 993. The second page shown here is a copy of Gerbert's abacus board. (From MS Trier, Stadtbibliothek 1093/1694 fol.)

One of the frescoes by Gabor Szinte in the Church of St Simon near Aurillac shows a young Gerbert learning about Arabic numerals in Islamic Spain. You can learn about the frescoes on the Aurillac tourism website, here.

Read more about Professor Charles Burnett and his work at the website of the Warburg Institute, London, here.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in the medieval world.

Published on May 09, 2012 07:57

May 2, 2012

A Troll’s Tale from Iceland

A few years ago, I rode a marvelous blue-dun horse across Iceland. Nearing the end of our six-day trek, we stopped for lunch at the church of Haukadalur, near the famous geysers. To entertain us while we ate, our trekking guide, Svandis, told the story of the church and its resident troll.

A few years ago, I rode a marvelous blue-dun horse across Iceland. Nearing the end of our six-day trek, we stopped for lunch at the church of Haukadalur, near the famous geysers. To entertain us while we ate, our trekking guide, Svandis, told the story of the church and its resident troll.Bergthor of Blafell was unlike other trolls: He liked the sound of church bells. He was further unusual, in Icelandic folklore, for having a human best friend. One day Bergthor (whose name means Mountain Thor, or God of the Mountain), asked his friend to do him a favor. “When I die, will you bury me beside the church?”

His friend agreed. “But how will I know you are dead?”

“I will prop my walking stick outside my cave the night I die, and I will leave a chest of gold beside my bed to pay for the funeral.”

All happened as the troll said. The friend saw the walking stick propped against the cave door. He got a party together to fetch the huge corpse. He found a little chest—but it was full of dry, yellow leaves.

Heaving a sigh (What do you expect from a troll?), he fulfilled his side of the bargain and brought the corpse to church. They dug a grave just outside the churchyard and buried Bergthor beneath a red stone. It’s still there—“You can go see it,” Svandis said.

We dutifully traipsed through the churchyard, peeking into the windows of the little wooden church with its four pews and blue-painted ceiling. There was the stone, “Bergthor” carved in a suspiciously modern font.

“But that’s not the end of the story,” Svandis said.

One of the gravediggers suddenly felt his pants slipping down. He had filled his pockets with dead leaves from the chest, and the leaves had turned to solid gold.

The troll’s friend hurried back to the cave to fetch the forgotten chest of gold—but it was too late. It was gone.

“He should have trusted Bergthor’s word,” Svandis said, “even if he was a troll.” He should have trusted the God of the Mountain.

You can read another version of this story in the book A Traveller's Guide to Icelandic Folk Tales by Jón R. Hjálmarsson. For a review of the book from the newspaper, The Reykjavík Grapevine, click here.

If you're inspired to ride across Iceland like I did, I recommend Íshestar's Highland tour named Kjölur. The photo above comes from their website, which has many other inspiring shots of Iceland's interior highlands, the haunt of trolls.

Join me again next Wednesday for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world at http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com.

Published on May 02, 2012 11:18

April 25, 2012

Saving Face in Iceland

We celebrated our tenth wedding anniversary in 1992 with a camping trip to the Hornstrandir on the northwestern tip of Iceland. Once the home of the great Viking warrior-king Geirmund Hell-Skin, whom you can read about in the medieval Icelandic Book of Settlements (Landnámabók), the Hornstrandir is now a nature preserve reachable only by boat. Preparing for our expedition, we had a lot of advice from our Icelandic friends—some of which we thought, for years afterward, had been a practical joke.

Waiting for the ferry to take us to the Hornstrandir, we set up house in the campground behind Isafjord’s summer hotel. With Bill and Susie, two fellow campers from Tasmania, tagging along, we went shopping to round out our boiled eggs with other nesti, a convenient Icelandic term for camping supplies.

Bill was a voluble storyteller. He went into great detail about the bear that ripped up their tent in Yellowstone, about how impossible it was to get alcohol for their Trangia stove in the U.S., about not being served in Northern Ireland, about how the Irish slaves brought to Iceland during the Viking Age were responsible for the storytelling genes that led to the medieval Icelandic sagas, treasures of world literature that I had been studying for twelve years. Bill was immune to cold shoulders. He ignored our hints that we wanted to be alone.

The town of Isafjord (population 3,500) edged the foot of a bluff, then straggled along a curving sandspit into the true Isafjord—the Ice Fjord—a harbor on one side, a bulkhead on the other. It smelled of fish and sea and diesel fuel. Founded in 1787, it had three stunning old 18th-century warehouses along its main street, a dozen ugly high-rises, and a jumble of cottages, among which we found a bakery, a market, and (unfortunately) a fish shop.

DRIED FISH & TRADITION

The best backpacking food, we had been told by a friend in Reykjavik, was dried fish. And the very best dried fish, steinbítur, could only be found in Isafjord. Dutifully, I asked the woman at the counter for steinbítur. They did not have any. I picked up a package of dried haddock instead—neatly bite-sized and vacuum-packed—from a bin by the register.

“Nú já!” the woman said, snatching the package from me and tossing it back into the bin. She spoke rapid-fire Icelandic to the old man beside her, whose eyebrows rose in admiration. I understood the gist of it, not every word: Tourists, apparently, did not often come asking for dried steinbítur. He called to a boy, who soon returned from the adjacent warehouse with a large, clear plastic trashbag stuffed with long, thin, dark strips of desiccated fish, mostly skin. It looked like leather straps. It was a kilo of steinbítur. My husband said we’d take the haddock.

“That’s trash,” said the woman at the counter, waving it away. “Taste this.” She broke off a bit of steinbítur for each of us. It was strong and tough and dry and fishy, like chewing sea-drenched wood chips. I’d had dried haddock before. Slathered with butter, it tasted like fish-flavored crackers. Steinbítur tasted like its name: Stone Biter. Like wind and sea and a long tradition of living off whatever you could catch. The Aussies said, No way, and left.

The old man watched me while I chewed. He was a thin, wizened sailor with sharp blue eyes under a blue watchcap. His face was wind-rough and sun-wrinkled. The woman was twice his size, sturdy and wide-faced, her motherly look cooling the more we dithered over how much of the stuff we’d have to buy to save face. For me to save face, that is. I’d done the asking. My husband, like the Aussies, didn’t want any at all.

We ended up with a quarter-kilo, a long stiff hose that would soon perfume all the rest of our camping gear. It was not enough. The three Icelanders shook their heads. We were idiots. Luckily, they could not know we would toss most of it onto a rock by the sea on the Hornstrandir, leaving it to delight the gulls. There was only so much of its penetrating fishiness I could take, even for tradition’s sake.

The West Tours website (http://www.vesturferdir.is/index.php?...) has all kinds of information on visiting the Hornstrandir Nature Preserve in Iceland. Getting to Isafjord is easy by bus or plane from Iceland’s capital city, Reykjavik. I haven’t checked, but I’m sure the fish shop is still there, down by the harbor.

Photos: Me, musing, on the edge of a cliff (photo by Charles Fergus). The steep cliffs of Hornvik, from the West Tours website. Sunset in Hornvik-Hornstrandir by eir@si, found on Flickr.

Join me next Wednesday for another adventure at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com

Published on April 25, 2012 05:13

April 18, 2012

How to Make a Medieval Book, Part II

As I said last week, for me the hardest part of writing a book is deciding what to say. But in the Middle Ages, as I learned when researching the technology of book-making for The Abacus and the Cross, a lot more work was involved. Last week, we learned how to make the parchment for your book’s pages. Here’s how to make your ink and bind your book.

As I said last week, for me the hardest part of writing a book is deciding what to say. But in the Middle Ages, as I learned when researching the technology of book-making for The Abacus and the Cross, a lot more work was involved. Last week, we learned how to make the parchment for your book’s pages. Here’s how to make your ink and bind your book.Ink At the monastery of Saint Columban in Bobbio, Italy—which once held the greatest Christian library of the tenth century, with 690 books—Jessica Lavelli runs a project for schoolchildren called CoolTour. After they understand how to make parchment (see How to Make a Book: Part I), Lavelli’s pupils get to make their own manuscript. They copy a page from a tenth-century life of the founder of Bobbio, the Irish Saint Colomban. The page begins, Beatus ergo Columbanus, and the initial “B,” taking up a third of the page, is a maze of Celtic knotwork in red, blue, green, and black. For Beatus, the pupils substitute their own names; they fill out the rest of the line any way they like.

Lavelli does not supply authentic medieval inks. “The kids write their names using goose quills and common black ink. Then we give them paintbrushes, and vinegar and egg white to mix the colors, which we buy at an artists’ shop. The colors are not easy to find,” she added, “and it can get very expensive if you want to make your own.”

In the Middle Ages, black ink was made from oak galls—the black bubbles you find on an oak twig where the gall wasp has stung it to lay its eggs. The galls were ground, cooked in wine, and mixed with iron sulfate and gum arabic. Oak galls contain gallic acid, which causes collagen to contract; instead of sitting on the surface, the ink etches the words into the parchment. Crushed iron sulfate (often found together with pyrite) makes the ink black; gum arabic, the sap of the acacia tree, makes it thick. Another recipe called for vinegar and rind of pomegranate. Egg white (preserved by a sprig of cloves) and fish glue were used, in addition to gum arabic, to thicken colors; other common ingredients were ear wax, pine rosin, lye, stale urine, and horse dung.

To make the red ink commonly used for titles, you have to grind and cook “flake-white,” a white crust that forms on lead sheets hung above a pot of simmering wine. To make green, you need copper filings, ground egg yolks, quicklime, tartar sediment, common salt, strong vinegar, and boy’s urine. An expensive blue was made by grinding up lapis lazuli; a cheaper variety could be made from the woad plant, which contains the same chemical as indigo. Yellows were made from the plants weld or saffron, or from unripe buckthorn berries. Purple came from the herb turnsole, brick red from madder root, and pink from brazilwood, while earth colors came from filtered and roasted dirt.

The parchment made, the ink mixed, an expert scribe could write at the rate of forty strokes (five to six words) a minute, which over a six-hour day adds up to two hundred lines per day. Michael Gullick, in Making the Medieval Book, came up with these numbers by counting the lines in a manuscript that a scribe claimed to have written entirely by his own hand in a month. Doubting that anyone could maintain that speed, Gullick asked the calligrapher Donald Jackson for a second opinion. Jackson had worked with quill and parchment for thirty years. He copied lines from the manuscript, taking into account the height of the strokes, the line length, and “the finesse and skill of the scribe.” Jackson estimated the maximum possible speed at twenty-five lines an hour. If the scribe really finished the book in a month, he concluded, he had worked eight hours a day every single day.

And that was just for the text. Illustrations and the fancy initial capitals, like the B for Beatus, were usually done by a different monk, who specialized in drawing. A scholar who examined one luxurious book of psalms found it to be the work of three scribes, a rubricator (who did just the red titles), and nine artists.

BookbindingFinally the finished pages were sewn into quires (often gathered together with the text of several other books on the same or different topics) and bound between boards of oak or beech. The inside of each board was covered with a fly leaf or pastedown, a piece of fresh parchment or (more often) one recycled from an unwanted manuscript. Sometimes these old sheets were cleaned first, by soaking them in whey or orange juice and scraping off the inks and colors; fortunately, this was not always done—more than one precious leaf has been saved because it was recycled.

The outsides of the boards were covered in leather (alum-tawed pig’s leather was preferred, because it was white) and fitted with metal clasps to keep the book from popping open. Then it would be locked away in a wooden bookchest to protect it—not from thieves, who could open the chest with an axe, so much as from borrowers who might “forget” to return it. For a book was a very valuable thing. A historian who tried to calculate exactly how valuable, found a law book that was bought for eight denaris: the price of ninety-six two-pound loaves of bread.

The bread I buy from a local bakery is about $5.00 a loaf, making the cost of that law book today about $480. My book The Abacus and the Cross, on the other hand, costs $28—in hardback. The paperback, due out in October, will be only $17, just a little more than three loaves of bread.

If you visit Bobbio, check out CoolTour and say hello to Jessica for me: http://www.cooltour.it/

For an overnight stay, I recommend the farm guesthouse San Martino. It is (of course!) a horse farm within walking distance of the town: http://www.agriturismo-sanmartino.com/

Bobbio has also been recently identified as the town painted in the background of the Mona Lisa. As one newspaper said, “brace for tourists”! http://www.newser.com/story/109501/art-historian-identifies-mona-lisas-home-town.html

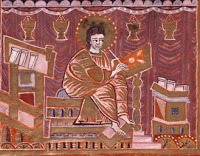

Photos: Detail of a Bobbio manuscript and portrait of a scribe, both from the CoolTour Bobbio website.

Join me again next Wednesday for an excursion into the medieval world at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com

Published on April 18, 2012 07:25

How to Make a Book, Part II

As I said last week, for me the hardest part of writing a book is deciding what to say. But in the Middle Ages, as I learned when researching the technology of book-making for The Abacus and the Cross, a lot more work was involved. Last week, we learned how to make the parchment for your book’s pages. Here’s how to make your ink and bind your book.

As I said last week, for me the hardest part of writing a book is deciding what to say. But in the Middle Ages, as I learned when researching the technology of book-making for The Abacus and the Cross, a lot more work was involved. Last week, we learned how to make the parchment for your book’s pages. Here’s how to make your ink and bind your book.Ink At the monastery of Saint Columban in Bobbio, Italy—which once held the greatest Christian library of the tenth century, with 690 books—Jessica Lavelli runs a project for schoolchildren called CoolTour. After they understand how to make parchment (see How to Make a Book: Part I), Lavelli’s pupils get to make their own manuscript. They copy a page from a tenth-century life of the founder of Bobbio, the Irish Saint Colomban. The page begins, Beatus ergo Columbanus, and the initial “B,” taking up a third of the page, is a maze of Celtic knotwork in red, blue, green, and black. For Beatus, the pupils substitute their own names; they fill out the rest of the line any way they like.

Lavelli does not supply authentic medieval inks. “The kids write their names using goose quills and common black ink. Then we give them paintbrushes, and vinegar and egg white to mix the colors, which we buy at an artists’ shop. The colors are not easy to find,” she added, “and it can get very expensive if you want to make your own.”

In the Middle Ages, black ink was made from oak galls—the black bubbles you find on an oak twig where the gall wasp has stung it to lay its eggs. The galls were ground, cooked in wine, and mixed with iron sulfate and gum arabic. Oak galls contain gallic acid, which causes collagen to contract; instead of sitting on the surface, the ink etches the words into the parchment. Crushed iron sulfate (often found together with pyrite) makes the ink black; gum arabic, the sap of the acacia tree, makes it thick. Another recipe called for vinegar and rind of pomegranate. Egg white (preserved by a sprig of cloves) and fish glue were used, in addition to gum arabic, to thicken colors; other common ingredients were ear wax, pine rosin, lye, stale urine, and horse dung.

To make the red ink commonly used for titles, you have to grind and cook “flake-white,” a white crust that forms on lead sheets hung above a pot of simmering wine. To make green, you need copper filings, ground egg yolks, quicklime, tartar sediment, common salt, strong vinegar, and boy’s urine. An expensive blue was made by grinding up lapis lazuli; a cheaper variety could be made from the woad plant, which contains the same chemical as indigo. Yellows were made from the plants weld or saffron, or from unripe buckthorn berries. Purple came from the herb turnsole, brick red from madder root, and pink from brazilwood, while earth colors came from filtered and roasted dirt.

The parchment made, the ink mixed, an expert scribe could write at the rate of forty strokes (five to six words) a minute, which over a six-hour day adds up to two hundred lines per day. Michael Gullick, in Making the Medieval Book, came up with these numbers by counting the lines in a manuscript that a scribe claimed to have written entirely by his own hand in a month. Doubting that anyone could maintain that speed, Gullick asked the calligrapher Donald Jackson for a second opinion. Jackson had worked with quill and parchment for thirty years. He copied lines from the manuscript, taking into account the height of the strokes, the line length, and “the finesse and skill of the scribe.” Jackson estimated the maximum possible speed at twenty-five lines an hour. If the scribe really finished the book in a month, he concluded, he had worked eight hours a day every single day.

And that was just for the text. Illustrations and the fancy initial capitals, like the B for Beatus, were usually done by a different monk, who specialized in drawing. A scholar who examined one luxurious book of psalms found it to be the work of three scribes, a rubricator (who did just the red titles), and nine artists.

BookbindingFinally the finished pages were sewn into quires (often gathered together with the text of several other books on the same or different topics) and bound between boards of oak or beech. The inside of each board was covered with a fly leaf or pastedown, a piece of fresh parchment or (more often) one recycled from an unwanted manuscript. Sometimes these old sheets were cleaned first, by soaking them in whey or orange juice and scraping off the inks and colors; fortunately, this was not always done—more than one precious leaf has been saved because it was recycled.

The outsides of the boards were covered in leather (alum-tawed pig’s leather was preferred, because it was white) and fitted with metal clasps to keep the book from popping open. Then it would be locked away in a wooden bookchest to protect it—not from thieves, who could open the chest with an axe, so much as from borrowers who might “forget” to return it. For a book was a very valuable thing. A historian who tried to calculate exactly how valuable, found a law book that was bought for eight denaris: the price of ninety-six two-pound loaves of bread.

The bread I buy from a local bakery is about $5.00 a loaf, making the cost of that law book today about $480. My book The Abacus and the Cross, on the other hand, costs $28—in hardback. The paperback, due out in October, will be only $17, just a little more than three loaves of bread.

If you visit Bobbio, check out CoolTour and say hello to Jessica for me: http://www.cooltour.it/

For an overnight stay, I recommend the farm guesthouse San Martino. It is (of course!) a horse farm within walking distance of the town: http://www.agriturismo-sanmartino.com/

Bobbio has also been recently identified as the town painted in the background of the Mona Lisa. As one newspaper said, “brace for tourists”! http://www.newser.com/story/109501/art-historian-identifies-mona-lisas-home-town.html

Photos: Detail of a Bobbio manuscript and portrait of a scribe, both from the CoolTour Bobbio website.

Join me again next Wednesday for an excursion into the medieval world at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com

Published on April 18, 2012 07:25

April 11, 2012

How to Make a Medieval Book

For me, the hardest part of making a book is deciding what to say. In the Middle Ages, there was more to it than that, as I learned when researching the technology of book-making for The Abacus and the Cross. This week and next, I’ll share what I found out.

CoolTour Bobbio: Today the greatest Christian library of the early Middle Ages—at the Italian monastery of Bobbio—is empty. Half of its 690 books went to Milan in the 1400s; from there, in the 1600s, some were sent to the Vatican. In 1803, after Napoleon shut down the monastery, the remaining manuscripts were auctioned off. Many were bought by the National Library of Turin, which burned down in 1904. “We don’t have even one to show the kids,” Jessica Lavelli told me. “The library in Milan will not even lend us one.”

An energetic young woman committed to Bobbio’s reputation as the library that “saved civilization” (Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization, visited Bobbio, which was founded by an Irish monk), Lavelli makes up with imagination what she lacks in resources. She calls her project CoolTour. From October to March, she invites one school group a week into the monastery and teaches them how to make a manuscript; in April and May, it’s thirty kids a day. “They come from all over northern Italy: Milan, Genova, Brescia, Parma, Cremona. Anywhere that’s less than two hours by bus.”

After a tour of the ancient walled town, with its castle on the hill and its hump-backed Roman bridge over the rushing river Trebbia, the children march through the arched gate behind the basilica and into the high-walled monastery complex. They pass through the cloister, its shady, columned arcades opening onto a sunny square where the monks would have had their herb garden, into a pair of bright classrooms; there they are issued goose quills, ink, and parchment. They learn the history of script from hieroglyphics to computer typesetting and how to make a book starting with the sheep.

Parchment: In one corner stands a sample of parchment stretched on a drying frame. “I got a sheepskin from a brasserie, a butcher, last spring,” Lavelli told me. “In Italy, it’s common to eat sheep for Easter, so they had many skins. A lamb would be half this size. From one sheep you can get two pages—four sides when it’s folded. From a lamb you only get one.”

How did she learn to make parchment? “From a book. We found a book and tried to do it. It’s a very long process. It takes four days to prepare and one week to dry, so after about ten days we can cut out our page. You dry it not in the sun or in the dark, but in the penumbra. We put it here”—she motioned toward a shady niche in the cloister where high walls block the sun from three directions. “The smell of the skin is not good,” she added, wrinkling her nose. “When it stops smelling, it’s dry.”

According to Pliny’s Natural History, written in the first century A.D., parchment—in Latin, pergamenum—was invented for the king of Pergamos (modern Bergama, Turkey) to break the Egyptian monopoly on papyrus. The sedge used for papyrus was common only on the banks of the Nile. Sheepskins were everywhere.

The oldest known recipe for turning sheepskin into parchment was written in the Italian city of Lucca at the end of the eighth century. “Place it in limewater,” it says, “and leave it there for three days and extend it on a frame and scrape it on both sides with a razor and leave it to dry, then do any kind of smoothing that you want.” A twelfth-century manuscript offers more precise—but still somewhat mysterious—instructions on how “to make parchment from goatskins as it is done in Bologna”; this process takes twenty-four days plus drying. Book conservator Leandro Gottscher compared the two methods during a series of experiments one hot summer in Rome in the 1990s. Both made acceptable parchment, though the shorter soaking time made for harder work scraping off the hair.

The oldest known recipe for turning sheepskin into parchment was written in the Italian city of Lucca at the end of the eighth century. “Place it in limewater,” it says, “and leave it there for three days and extend it on a frame and scrape it on both sides with a razor and leave it to dry, then do any kind of smoothing that you want.” A twelfth-century manuscript offers more precise—but still somewhat mysterious—instructions on how “to make parchment from goatskins as it is done in Bologna”; this process takes twenty-four days plus drying. Book conservator Leandro Gottscher compared the two methods during a series of experiments one hot summer in Rome in the 1990s. Both made acceptable parchment, though the shorter soaking time made for harder work scraping off the hair.The limewater is the key to the process. It was made by burning crushed limestone (or marble, chalk, or shells) in a kiln to make quicklime, placing that in a vat or barrel, and adding a little water. The limewater would seethe and bubble and be ready in about ten minutes. Gottscher spread a pulp of limewater onto the skin, folded it, and set it aside for a few days. Other experimenters prefer to dilute the limewater until it is milky and soak the skin. The lime eats into the epidermis, the outer layers of the skin, loosening the hair on one side and the fat on the other.

To remove the hair, rinse off the lime and pull or pluck out whatever hair you can. (Gloves are a good idea—any remaining lime will eat into your skin too.) Next lay the skin over a log or trestle and rub it with a wooden hone, a bone spatula, or a dull knife, a procedure called scudding.

To remove the fat, the hairless skin can be dunked in fresh limewater or rubbed with lime powder, then spread on the trestle, hair-side down, and scudded again. Lean sheep make better parchment than fat ones; excess fat makes the parchment slippery and the ink doesn’t stick. On the other hand, parchment that is scraped too thin can become wrinkly and transparent.

The dehaired and defatted skin is soaked again and stretched onto a wooden frame to dry. To avoid tearing holes, first wrap a corner of skin around a pebble (called a pippin), tie one end of a cord around the pippin and another to a wooden peg in the frame. As the skin dries, tighten the pegs.

While leather-making is a chemical process, parchment-making is a physical process. What’s left after all the soaking and scudding is mostly collagen, long spiraling proteins that form tough, elastic fibers. As the skin dries, these fibers try to shrink. Stopped by the frame, instead the fibers’ structure begins to change.

When it’s dry, the parchment is scraped again, still on the frame, with a crescent-shaped blade called a lunellum (“little moon”), powdered again with lime or chalk to bleach it, and rubbed thoroughly on both sides with a pumice stone to raise a nap. Then it is taken down and cut into sheets of a standard size. The first sheet is easy: a rectangle that, folded, could become four pages of a large book (or eight pages of a small one). Then the cutter has to become creative: A sheepskin is not square. Where the head, legs, and tail were cut off, the skin curves. Scholars often come across manuscript pages with a corner missing—where a page runs into a neck hole. Other blemishes are insect bites (little holes), wounds on the animal (bigger holes), and gashes (where the knife slipped during the flaying); some of these are sewn up, but usually the scribe just wrote around them.

When it’s dry, the parchment is scraped again, still on the frame, with a crescent-shaped blade called a lunellum (“little moon”), powdered again with lime or chalk to bleach it, and rubbed thoroughly on both sides with a pumice stone to raise a nap. Then it is taken down and cut into sheets of a standard size. The first sheet is easy: a rectangle that, folded, could become four pages of a large book (or eight pages of a small one). Then the cutter has to become creative: A sheepskin is not square. Where the head, legs, and tail were cut off, the skin curves. Scholars often come across manuscript pages with a corner missing—where a page runs into a neck hole. Other blemishes are insect bites (little holes), wounds on the animal (bigger holes), and gashes (where the knife slipped during the flaying); some of these are sewn up, but usually the scribe just wrote around them.The color of parchment depends partly on the process and partly on the animal it came from. Low-grade parchment could be dark pinkish-brown with a chalky surface, peppered with hair follicles, streaked with scrape marks, or so thin that the ink bled through. Sheepskin, well cured, was “butter-white” or yellowish, but still sometimes greasy or shiny. Goatskin was greyish. Calfskin was the whitest, though the veins could be prominent. The parchment Jessica Lavelli made to show her pupils at Bobbio had a large brown spot. She shrugged. “It was a spotted sheep! I didn’t think it would matter.”

If you visit Bobbio, check out CoolTour and say hello to Jessica for me: http://www.cooltour.it/

For an overnight stay, I recommend the farm guesthouse San Martino. It is (of course!) a horse farm within walking distance of the town: http://www.agriturismo-sanmartino.com/

Bobbio has also been recently identified as the town painted in the background of the Mona Lisa. As one newspaper said, “brace for tourists”! http://www.newser.com/story/109501/art-historian-identifies-mona-lisas-home-town.html

Photos: Saint Luke at his writing desk, from Bernward's Evangelary (Dom Museum Hildesheim). The town of Bobbio, Italy. Portrait of a scribe from the CoolTour Bobbio website. Detail of a Bobbio manuscript, also from CoolTour Bobbio.

Published on April 11, 2012 08:10

How to Make a Book

For me, the hardestpart of making a book is deciding what to say. In the Middle Ages, there wasmore to it than that, as I learned when researching the technology ofbook-making for The Abacus and the Cross. This week and next, I'll share what I found out.

CoolTour Bobbio: Today the greatest Christian library of the early MiddleAges—at the Italian monastery of Bobbio—is empty. Half of its 690 books went toMilan in the 1400s; from there, in the 1600s, some were sent to the Vatican. In1803, after Napoleon shut down the monastery, the remaining manuscripts wereauctioned off. Many were bought by the National Library of Turin, which burneddown in 1904. "We don't have even one to show the kids," Jessica Lavelli told me."The library in Milan will not even lend us one."

An energetic young woman committed to Bobbio's reputation asthe library that "saved civilization" (Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization,visited Bobbio, which was founded by an Irish monk), Lavelli makes up withimagination what she lacks in resources. She calls her project CoolTour. FromOctober to March, she invites one school group a week into the monastery andteaches them how to make a manuscript; in April and May, it's thirty kids aday. "They come from all over northern Italy: Milan, Genova, Brescia, Parma,Cremona. Anywhere that's less than two hours by bus."

After a tour of the ancient walled town, with its castle onthe hill and its hump-backed Roman bridge over the rushing river Trebbia, thechildren march through the arched gate behind the basilica and into thehigh-walled monastery complex. They pass through the cloister, its shady,columned arcades opening onto a sunny square where the monks would have hadtheir herb garden, into a pair of bright classrooms; there they are issuedgoose quills, ink, and parchment. They learn the history of script fromhieroglyphics to computer typesetting and how to make a book starting with thesheep.

Parchment: In one corner stands a sample of parchment stretched on adrying frame. "I got a sheepskin from a brasserie, a butcher, last spring,"Lavelli told me. "In Italy, it's common to eat sheep for Easter, so they hadmany skins. A lamb would be half this size. From one sheep you can get twopages—four sides when it's folded. From a lamb you only get one."

How did she learn to make parchment? "From a book. We founda book and tried to do it. It's a very long process. It takes four days toprepare and one week to dry, so after about ten days we can cut out our page.You dry it not in the sun or in the dark, but in the penumbra. We put it here"—she motioned toward a shady niche in thecloister where high walls block the sun from three directions. "The smell ofthe skin is not good," she added, wrinkling her nose. "When it stops smelling,it's dry."

According to Pliny's NaturalHistory, written in the first century A.D., parchment—in Latin, pergamenum—was invented for the king ofPergamos (modern Bergama, Turkey) to break the Egyptian monopoly on papyrus. Thesedge used for papyrus was common only on the banks of the Nile. Sheepskinswere everywhere.

The oldest known recipe for turning sheepskin into parchmentwas written in the Italian city of Lucca at the end of the eighth century."Place it in limewater," it says, "and leave it there for three days and extendit on a frame and scrape it on both sides with a razor and leave it to dry,then do any kind of smoothing that you want." A twelfth-century manuscript offers more precise—but still somewhatmysterious—instructions on how "to make parchment from goatskins as it is donein Bologna"; this process takes twenty-four days plus drying. Book conservatorLeandro Gottscher compared the two methods during a series of experiments onehot summer in Rome in the 1990s. Both made acceptable parchment, though theshorter soaking time made for harder work scraping off the hair.

The oldest known recipe for turning sheepskin into parchmentwas written in the Italian city of Lucca at the end of the eighth century."Place it in limewater," it says, "and leave it there for three days and extendit on a frame and scrape it on both sides with a razor and leave it to dry,then do any kind of smoothing that you want." A twelfth-century manuscript offers more precise—but still somewhatmysterious—instructions on how "to make parchment from goatskins as it is donein Bologna"; this process takes twenty-four days plus drying. Book conservatorLeandro Gottscher compared the two methods during a series of experiments onehot summer in Rome in the 1990s. Both made acceptable parchment, though theshorter soaking time made for harder work scraping off the hair.The limewater is the key to the process. It was made byburning crushed limestone (or marble, chalk, or shells) in a kiln to makequicklime, placing that in a vat or barrel, and adding a little water. Thelimewater would seethe and bubble and be ready in about ten minutes. Gottscherspread a pulp of limewater onto the skin, folded it, and set it aside for a fewdays. Other experimenters prefer to dilute the limewater until it is milky andsoak the skin. The lime eats into the epidermis, the outer layers of the skin,loosening the hair on one side and the fat on the other.

To remove the hair, rinse off the lime and pull or pluck outwhatever hair you can. (Gloves are a good idea—any remaining lime will eat intoyour skin too.) Next lay the skin over a log or trestle and rub it with awooden hone, a bone spatula, or a dull knife, a procedure called scudding.

To remove the fat, the hairless skin can be dunked in freshlimewater or rubbed with lime powder, then spread on the trestle, hair-sidedown, and scudded again. Lean sheep make better parchment than fat ones; excessfat makes the parchment slippery and the ink doesn't stick. On the other hand,parchment that is scraped too thin can become wrinkly and transparent.

The dehaired and defatted skin is soaked again and stretchedonto a wooden frame to dry. To avoid tearing holes, first wrap a corner of skinaround a pebble (called a pippin),tie one end of a cord around the pippin and another to a wooden peg in theframe. As the skin dries, tighten the pegs.

While leather-making is a chemical process, parchment-makingis a physical process. What's left after all the soaking and scudding is mostlycollagen, long spiraling proteins that form tough, elastic fibers. As the skindries, these fibers try to shrink. Stopped by the frame, instead the fibers'structure begins to change.

When it's dry, the parchment is scraped again, still on theframe, with a crescent-shaped blade called a lunellum ("little moon"), powdered again with lime or chalk tobleach it, and rubbed thoroughly on both sides with a pumice stone to raise anap. Then it is taken down and cut into sheets of a standard size. The firstsheet is easy: a rectangle that, folded, could become four pages of a largebook (or eight pages of a small one). Then the cutter has to become creative: Asheepskin is not square. Where the head, legs, and tail were cut off, the skincurves. Scholars often come across manuscript pages with a corner missing—wherea page runs into a neck hole. Other blemishes are insect bites (little holes),wounds on the animal (bigger holes), and gashes (where the knife slipped duringthe flaying); some of these are sewn up, but usually the scribe just wrotearound them.

When it's dry, the parchment is scraped again, still on theframe, with a crescent-shaped blade called a lunellum ("little moon"), powdered again with lime or chalk tobleach it, and rubbed thoroughly on both sides with a pumice stone to raise anap. Then it is taken down and cut into sheets of a standard size. The firstsheet is easy: a rectangle that, folded, could become four pages of a largebook (or eight pages of a small one). Then the cutter has to become creative: Asheepskin is not square. Where the head, legs, and tail were cut off, the skincurves. Scholars often come across manuscript pages with a corner missing—wherea page runs into a neck hole. Other blemishes are insect bites (little holes),wounds on the animal (bigger holes), and gashes (where the knife slipped duringthe flaying); some of these are sewn up, but usually the scribe just wrotearound them.The color of parchment depends partly on the process andpartly on the animal it came from. Low-grade parchment could be darkpinkish-brown with a chalky surface, peppered with hair follicles, streakedwith scrape marks, or so thin that the ink bled through. Sheepskin, well cured,was "butter-white" or yellowish, but still sometimes greasy or shiny. Goatskinwas greyish. Calfskin was the whitest, though the veins could be prominent. Theparchment Jessica Lavelli made to show her pupils at Bobbio had a large brownspot. She shrugged. "It was a spotted sheep! I didn't think it would matter."

If you visit Bobbio, check out CoolTour and say hello toJessica for me: http://www.cooltour.it/

For an overnight stay, I recommend the farm guesthouse SanMartino. It is (of course!) a horse farm within walking distance of the town: http://www.agriturismo-sanmartino.com/

Bobbio has also been recently identified as the town paintedin the background of the Mona Lisa. As one newspaper said, "brace fortourists"! http://www.newser.com/story/109501/art-historian-identifies-mona-lisas-home-town.html

Photos: Saint Luke at his writing desk, from Bernward's Evangelary (Dom Museum Hildesheim). The town of Bobbio, Italy. Portrait of a scribe from the CoolTour Bobbio website. Detail of a Bobbio manuscript, also from CoolTour Bobbio.

Published on April 11, 2012 08:10