Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 13

October 2, 2013

Bewilderment Is Power: S. Leonard Rubinstein (1922-2013)

"Bewilderment is power."

"Bewilderment is power."These are the words of S. Leonard Rubinstein, my writing teacher at Penn State University in the late 1970s, my mentor and friend until his peaceful death a few days ago at the ripe old age of 91, and one of a trio of teachers to whom I dedicated my last book, Song of the Vikings.

Bewilderment is power: These are the words that chime in my head every time, like now, I am embarking on the writing of a new book--or any major piece of writing.

Bewilderment is power: Only when you realize you do not understand will you make the effort to understand.

Paired with this powerful aphorism in my mind is another: "Writing is infinitely perfectable." To revise successfully, collaboration is essential. Without criticism from sources, editors, and readers, revision can be endless, and ultimately pointless.

All of Leonard's writing students learned this. They learned that good nonfiction writing was "the painless delivery of information" and that "anything looked at closely enough is interesting." They learned that "we earn belief," that "honesty is a skill," and that writing is "a habit of mind."

I was privileged, however, as a graduate student and employee of Penn State, to produce a half-hour radio series, "Odyssey Through Literature," with Leonard as the host. (Our logo, above, was created by artist Jeffery Mathison.)

Leonard and I recorded 260 "Odyssey Through Literature" radio shows between 1980 and 1998, interviewing writers, translators, and scholars of literature from around the world. A hallmark of the show was to read the works in their original languages (as well as in translation). I became accustomed to hearing what Leonard called "the music of the language" before I knew what the words meant.

The real impact of the show on my education as a writer came after the actual interview. As the producer, I had to listen to each tape over and over again to edit it down from the recorded 50 minutes or more to our 28-minute airtime. Doing so lodged snatches of poems and prose permanently in my brain, along with the voice of the person who read it on the air. For instance:

--The apparition of these faces in the crowd: petals on a wet black bough.

(Ezra Pound, read by Peter Schneeman)

--Who were these people? And who finished them to the last? If dust had an alphabet, I would learn.

(Agha Shahid Ali, a Kashmiri poet)

--We rode the low moon out of the sky, our hooves drummed up the door.

(Rudyard Kipling, read by Jorge Luis Borges)

--I am the exile, the wanderer, the troubadour (whatever they say)

(Dennis Brutus, an exiled South African poet)

--The bud is the emblem of all things, even of those things that don’t flower. For everything flowers, from within: of self-blessing.

(Galway Kinnell)

--My ancestor, a man of Himalayan snow, came to Kashmir from Samarkand, carrying a bag of whalebones, heirlooms of sea funerals.

(Shahid, again)

--“Haere mai, mokopuna,” she would say. And I would always go with her, for I was both her keeper and her companion. I was a small boy; she was a child too, in an old woman’s body.

“Where are we going today, Nanny?” I would ask. But I always knew.

“We go down to the sea, mokopuna, to the sea…”

(Maori writer Witi Ihimaera, read by Murray Martin)

Working with Leonard on "Odyssey Through Literature" convinced me that all literature, all good writing, is meant to be read aloud: that the sound of the words is as important as their dictionary meaning and cannot be divorced from that meaning. It made me conscious in my own writing of rhythm and rhyme, alliteration and assonance. It made me punctuate musically. It made me take care that the words I chose fit both the sound and the sense of what I wanted to say.

Working with Leonard on "Odyssey Through Literature" convinced me that all literature, all good writing, is meant to be read aloud: that the sound of the words is as important as their dictionary meaning and cannot be divorced from that meaning. It made me conscious in my own writing of rhythm and rhyme, alliteration and assonance. It made me punctuate musically. It made me take care that the words I chose fit both the sound and the sense of what I wanted to say.In 2007, many years after our radio program ended and I had moved away, I received a thank-you letter from Leonard: "Slowly, in the course of transforming 'Odyssey Through Literature' cassettes into CDs, I realize how much I owe you for bringing so many accomplished people to sit across the table from me. In short, I thank you for my education."

I hope Leonard knew, when I dedicated Song of the Vikings to him in 2012 (for which he also, gracious as ever, sent me a thank-you letter), that I thanked him for my education.

Some people say writing can't be taught. I think the many students of S. Leonard Rubinstein who are now professional writers would agree with me that it can.

Click here to read Leonard's obituary.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on October 02, 2013 06:42

September 25, 2013

The Death of Snorri Sturluson

In 2010, on the night of Snorri Sturluson’s murder, September 23, I sat on the stones surrounding his hot tub at Reykholt in western Iceland and dabbled my feet in the warm pool. The weather had turned: A cold mist replaced the sunshine of Thingvellir, where I’d walked, picking blueberries, that afternoon, memorizing the verse on the bronze plaque beside Snorri’s Althing booth, the place he called Valhalla. In English the lines run:

In 2010, on the night of Snorri Sturluson’s murder, September 23, I sat on the stones surrounding his hot tub at Reykholt in western Iceland and dabbled my feet in the warm pool. The weather had turned: A cold mist replaced the sunshine of Thingvellir, where I’d walked, picking blueberries, that afternoon, memorizing the verse on the bronze plaque beside Snorri’s Althing booth, the place he called Valhalla. In English the lines run:Snorri’s old site is a sheep-pen; the Law Rock is hidden in heather,

blue with the berries that make boys—and the ravens—a feast.

I knew the next two lines of this poem by Jónas Hallgrimsson (in the translation by Dick Ringler):

Oh you children of Iceland, old and young men together!

See how your forefathers’ fame faltered—and died from the earth!

And knew its fears were unsubstantiated: Researching Snorri Sturluson’s life for my book Song of the Vikings , I had concluded that Snorri, who lived from 1178 to 1241, was the single most influential writer of the Middle Ages.

For that we must thank the king of Norway, Hakon IV. Only fourteen when Snorri met him in 1218, King Hakon preferred the fashionably new French legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table to traditional Viking skaldic poetry and tales of the gods Odin, Loki, and Thor. Snorri must have been shocked. It also hit him in the pocketbook. Poetry was Iceland’s cultural capital, to use a term popularized by sociologists. It was all Snorri had to sell on the international market. Iceland’s other exports were wool and dried fish. The bright-colored alum-dyed cloth from England and Flanders was more highly prized, and Norway had ample fish.

Perhaps, Snorri thought, King Hakon was just ill-educated. He simply needed a good introduction to the lore of the North. Snorri began writing his books to teach the young king to appreciate his own heritage.

Perhaps, Snorri thought, King Hakon was just ill-educated. He simply needed a good introduction to the lore of the North. Snorri began writing his books to teach the young king to appreciate his own heritage.His motives were not pure. Snorri was not only a poet and lover of books. He was one of the richest men in Iceland, holder of seven chieftaincies, owner of five profitable estates and a harbor, husband of an heiress, lover of several mistresses, a fat man soon to go gouty, a hard drinker, a seeker of ease prone to soaking long hours in his hot-tub while sipping stout ale, not a Viking warrior by any stretch of the imagination, but clever. Crafty, cunning, and ambitious. A good businessman. So well-versed in the law that few other Icelanders could out-argue him. At age forty-two, he was at the height of his power.

His secret ambition was to rule Iceland—and he almost succeeded. On the quay at Bergen in 1220, departing for home, he tossed off a praise poem about the king’s regent, Earl Skuli, said to be the handsomest man in Norway for his long red-blond locks. In response, the earl gave him the ship he was to sail in and many other fine gifts. Young King Hakon honored Snorri with the title of landed man, or baron, one of only fifteen so-named. The king charged Snorri, too, with a mission: He was to bring Iceland—then an independent republic of some 50,000 souls—under Norwegian rule.

Or so says one version of the story. The other says nothing about a threat to Iceland’s independence. Snorri was not asked to sell out his country, simply to sort out a misunderstanding between some Icelandic farmers and a party of Norwegian traders. A small thing. A few killings to even out. A matter of law.

This trip to Norway was the turning point of Snorri’s life. One quick, persuasive speech to the king, along with one colorful poem pronounced on the quay at Bergen, would mar his reputation—and seal his doom. When he sailed to Norway in 1218 he was, by most calculations, the uncrowned king of Iceland. When he returned in 1220, he was a suspected traitor.

The voyage did not go well. It was late in the year to sail, and the weather in the North Atlantic was fierce. His new ship lost its mast within sight of Iceland; it wrecked on the Westman Islands off the southern coast. Snorri had himself and his bodyguard of a dozen men ferried over to the mainland with their Norwegian treasures. They borrowed horses and rode, bedecked in bright-colored cloth like courtiers, wearing gold and jewels and carrying shiny new weapons and sturdy shields, to the nearby estate of the bishop of Skalholt. There Baron Snorri’s new title was ridiculed. Some Icelanders even accused him of treason, of having sold out to the Norwegian king.

From then until his death in 1241, he would fight one battle after another (in the courts, or by proxy) to see who, if anyone, would be Earl of Iceland, deputy to Norway’s king. He would die in his nightshirt, cringing in his cellar, begging for his life before his enemies’ thugs. He did not live up to his Viking ideals, to the heroes portrayed in his books. He did not die with a laugh—or a poem—on his lips. His last words were “Don’t strike!” As the poet Jorge Luis Borges sums him up in a beautiful poem, the writer who “bequeathed a mythology / Of ice and fire” and “violent glory” to us was a coward: “On / Your head, your sickly face, falls the sword, / As it fell so often in your book.”

From then until his death in 1241, he would fight one battle after another (in the courts, or by proxy) to see who, if anyone, would be Earl of Iceland, deputy to Norway’s king. He would die in his nightshirt, cringing in his cellar, begging for his life before his enemies’ thugs. He did not live up to his Viking ideals, to the heroes portrayed in his books. He did not die with a laugh—or a poem—on his lips. His last words were “Don’t strike!” As the poet Jorge Luis Borges sums him up in a beautiful poem, the writer who “bequeathed a mythology / Of ice and fire” and “violent glory” to us was a coward: “On / Your head, your sickly face, falls the sword, / As it fell so often in your book.”Yet his work remains. In the twenty turbulent years between his Norwegian triumph and his ignominious death, while scheming and plotting, blustering and fleeing, Snorri Sturluson did write his books: the Edda, Heimskringla, and Egil’s Saga. He covered hundreds of parchment pages with world-shaping words, encouraging his friends and kinsmen to cover hundreds of pages more.

I had come to Reykholt to keep vigil on the night of his death. The clouds crept up on me as I drove north from Thingvellir, slowly, on the torturous, washboard roads of Uxahryggir and Kaldidalur, alone for hours, no other cars, not even a bird, only the gleaming presence of Skjaldbreidur over my shoulder, the inverted smile of Ok, a chunk of rainbow here and there, a hidden stream, patches of dirty snow, a cairn. Now, at Reykholt, I sought darkness—some place I could see if the northern lights were shining in celebration of Snorri’s life and art.

Snorri’s Reykholt is much the same as it was in 1241, though nothing medieval but his hot-tub remains: Beside an imposing church is a school, hotel, and library. Up a spiral stair is a writer’s studio. But the modern designers were in love with light. Streetlamps and spotlights washed the night sky everywhere but here, at Snorri’s pool, tucked beneath the hill beside the school. I leaned back and looked up—no northern lights; the stars were faint, veiled in cloud. I imagined Snorri’s last moments.

His enemy (and former son-in-law) Gissur of Haukadal had spies watching Reykholt. Late at night on September 23, 1241, he rode up with seventy men. They broke into the building where Snorri slept. He leaped out of bed in his nightshirt and ran next door into the fine Norwegian-style loft-house he had built at the height of his power twenty years before. He was heading, perhaps, for his writing studio and the secret spiral stair that led from it down into a tunnel to his hot-tub and escape…

It is cold in Iceland in late September. The birch leaves are bright gold, the berry shrubs crimson, the songbirds have all flown. Swans flock in the marshlands, sounding their haunting note. Night falls quickly and lingers long, the wind has the bite of ice. An old fat man in his nightshirt, barefoot, would not get far in the cold and dark of a late-September night.

It is cold in Iceland in late September. The birch leaves are bright gold, the berry shrubs crimson, the songbirds have all flown. Swans flock in the marshlands, sounding their haunting note. Night falls quickly and lingers long, the wind has the bite of ice. An old fat man in his nightshirt, barefoot, would not get far in the cold and dark of a late-September night.Snorri hid in a cellar. A priest gave him away. Gissur sent five men down.

I dried off my feet and headed back toward the Snorrastofa writer’s studio, which I had booked for five days. On the way I heard people oohing and aahing. They were halfway down the drive, looking up at the northern lights, they said. I saw nothing. “They’re breaking up now,” said a man standing in the road.

Turns out that I, like Snorri that fateful night 772 years ago, had been looking the wrong way.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 25, 2013 06:18

September 18, 2013

Krummi Travel

One day last summer, under the midnight sun, I drove through the surreal landscape surrounding Iceland's Myvatn in a tour bus decorated with streamers and balloons. The driver, Thorstein, carried a big bag of candy. The company logo was No crybabies, cranks, or pantywaists allowed. What's a pantywaist? I didn't have the nerve to ask.

One day last summer, under the midnight sun, I drove through the surreal landscape surrounding Iceland's Myvatn in a tour bus decorated with streamers and balloons. The driver, Thorstein, carried a big bag of candy. The company logo was No crybabies, cranks, or pantywaists allowed. What's a pantywaist? I didn't have the nerve to ask.Paired with this hoopla was the elegant image of a raven, painted by the Icelandic artist Jón Baldur Hlíðberg (see more of his work here: http://www.fauna.is/defaulte.asp) and used as the company's logo by permission (okay, after the fact, but she did get permission) by the founder of Krummi Travel, Gerri Griswold of Connecticut.

Yes, Krummi Travel. Krummi is a fond nickname for ravens in Icelandic, but it was pronounced by pretty much everyone in Gerri's group as "crummy."

Being able to hold those two competing thoughts in your mind--elegant artwork, sounds like "crummy"--explains Gerri's brilliant approach to travel in Iceland. Yes, ravens are beautiful. They're also crummy: They eat the eyes out of newborn sheep. And Icelanders love them enough to give them a nickname on the order of "Tommy." (I know Icelandic men with the nicknames Gummi and Mummi.)

With Krummi Travel you get the nature and the culture of Iceland: the beautiful bird (mountain, fjord, etc.) and the layers and layers of cultural meanings. And you get it by meeting Icelanders.

Our tour guide around Myvatn, for example, Illugi (pronounced something like It-Louie), was a real raconteur. He jabbered on and on about how he lost his dog in the lava field. He made himself cry, remembering it. He made all of us cry. We were all out there in the lava field with him, in the snow, looking for the dog, who had fallen through a hole in the lava into a cave and burned her toes in the hotspring that nearly filled the cave floor. She was gone overnight. Illugi had to call in the Icelandic Rescue Squad to lift her out.

But there she was, in the bus with us, missing a few toes. She happily climbed up an enormous tuff-ring volcano and hiked all the way around the crater rim as if we were taking a walk in a park watching the sunset--which we were, Icelandic style.

Along the way, Illugi stopped to dismantle a cairn of stones some previous tourists had piled on the rim. He was quite annoyed by it. Cairns are used in Iceland to mark a path. They're not to be taken lightly or set up willy-nilly. To put one here was like spray-painting a statue. It was rock graffiti, which reminded Illugi to tell me about the real graffiti.

Can you imagine? Someone had clambered down into the bowl of this crater and spray-painted "CRATER" on the rocks. The letters were 17 meters tall, I later learned from a report on IcelandReview.com.

The same someone had written "CAVE" in a nearby cave and "MOOS" on a mossy lava field (couldn't spell). Interviewed on local TV, the local police inspector said, "I mainly find it strange. A very peculiar motive must be behind it.”

Peculiar indeed. Somebody thought it was "art."

A few days after my visit with Krummi Travel, I read about an Icelandic artist who was gallery hopping in Berlin. Reported IcelandReview.com, "He noticed an exhibition at the Alexander Levy gallery by an artist by the name of Julius von Bismarck, a student at the Studio Olafur Eliasson," run by the famous Icelandic-Danish artist. The visiting Icelander, Hlynur Hallsson, took photos of what he found on the gallery walls:

[For more photos, see http://www.icelandreview.com/icelandreview/search/news/Default.asp?ew_0_a_id=400624]

He then contacted the Icelandic media--and the police.

Bismarck, the German art student, quickly released a statement denying that he was the "nature terrorist." He said, in part: "Different anonymous artists collaborated on each location to produce the inscriptions." He said he wasn't even in Iceland at the time.

The gallery's website, on the other hand, gave him credit: "… In a series of nature inscriptions, Bismarck and Julian Charriere directly bring together nature and its conceptual (humanised) form …" [See http://www.icelandreview.com/icelandreview/search/news/Default.asp?ew_0_a_id=400643]

Hlynur, who outed Bismarck, is also known for "spray-paint artwork." As he told the website Akureyri Vikublad, "I don't approve of works that damage nature, regardless [of] whether they're made in the name of visual art or commercialism. To mark moss, lava, or rock faces with paint which doesn't wash off in the rain is unnecessary…. To write in the sand or snow can be more effective even though it only lasts a short time. … Then nature would have been given the respect it deserves."

Reading this, I was reminded of an essay by Justin Erik Halldór Smith called "The Moral Status of Rocks." [Read it here: http://www.jehsmith.com/1/2013/05/moral-status.html] He writes of meeting a "student in rural Iceland, of sheep-farming stock" who said, "in the hope of conveying to me the whole ethical-spiritual outlook of her country in a single concrete example: In Iceland we are taught not to smash rocks."

Smith goes on to talk about "environmental ethics" and why it usually refers to animals, sometimes to plants, but rarely to rocks. Except in Iceland. Where building a meaningless cairn, spray-painting a title on a crater, or smashing a rock are things no thinking human should do. Not even crybabies, cranks, or pantywaists--I mean, tourists. Or artists. Or those of us who aspire to being both.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 18, 2013 07:34

September 11, 2013

Surtshellir: The Outlaw's Cave

To explore the Outlaw's Cave, my friend told me, you need "a headlamp and serious shoes." I had a headlamp, though it malfunctioned and would only point straight down. On my feet I had rubber Wellington books--not up to clambering over hummocks of toaster-sized lava-rubble without twisting an ankle. I didn't make it far into the cave.

To explore the Outlaw's Cave, my friend told me, you need "a headlamp and serious shoes." I had a headlamp, though it malfunctioned and would only point straight down. On my feet I had rubber Wellington books--not up to clambering over hummocks of toaster-sized lava-rubble without twisting an ankle. I didn't make it far into the cave.I never saw the statues a local artist had placed there--eerie faces carved of rock, I'd heard.

I missed the ice formations that apparently linger year round.

I gave up well before I reached the outlaws' hideout, thoroughly freaked out by being alone in the unimaginable dark, some 30 feet under a lava field on the fringe of Iceland's uninhabitable interior. If I cried for help, no one would hear.

Usually cavers don't come to Surtshellir alone. And most are more courageous than I. In fact, so many tourists have reached the outlaws' hideout, some 600 feet along this lava tube, that Icelandic archaeologists have launched a rescue excavation to learn what they can about the outlaws' house before the evidence disappears. As archaeologist Guðmundur Ólafsson and his colleagues noted in 2004, tourists "were removing bones from it as souvenirs."

Surtshellir means "the cave of Surtr," the Norse fire-giant who will destroy the world. The lava in which the cave is found flowed shortly after Iceland was settled in the 870s. A mile-long tube, or tunnel, the cave was formed by thicker lava congealing around a faster flowing central stream that eventually ran out. At its broadest, the tube is about 45 feet wide and 30 feet high, though it shrinks down to about 6 feet high. In some places it branches out into side tunnels. In other places, the roof has fallen in, leaving large holes to the sky.

Surtshellir means "the cave of Surtr," the Norse fire-giant who will destroy the world. The lava in which the cave is found flowed shortly after Iceland was settled in the 870s. A mile-long tube, or tunnel, the cave was formed by thicker lava congealing around a faster flowing central stream that eventually ran out. At its broadest, the tube is about 45 feet wide and 30 feet high, though it shrinks down to about 6 feet high. In some places it branches out into side tunnels. In other places, the roof has fallen in, leaving large holes to the sky.Beneath one of these sky holes, about 300 feet from the cave's mouth, the outlaws built a wall about 8 feet high and 43 feet long. Another 300 feet along a side passage stands "a unique drystone structure with an associated midden," or garbage dump, according to the archaeologists.

One of the first books written in Iceland, the Landnámabók or Book of Settlements (from about 1130) notes that outlaws lived in in the lava field near Surtshellir in the late 900s. Two of the Icelandic sagas (written in the 1200s and 1300s) describe the outlaws' downfall, when a posse of chieftains decided to wipe them out.

In the 1700s century, two Icelanders explored the cave and found what they thought was the outlaws' hut. Two centuries later, the Icelandic novelist Halldor Laxness visited the cave and had his souvenir cow-bone dated by radiocarbon (carbon-14) testing in 1971. The dates he got spanned Iceland's Golden Age, from its founding in 870 to when it became a colony of Norway in 1264.

Since 1971, radiocarbon dating has improved. In 2004, Guðmundur Ólafsson and his colleagues dated some cow-bones from the midden to between 690 and 960.

The science of tephrochronology is also new since Halldor Laxness's effort; it uses the Greenland ice cores and other sources of information to date the layers of volcanic ash, or tephra, found like stripes in Iceland's soil. The lava field around Surtshellir rests on top of a tephra layer from an eruption dated to 871 (plus or minus 2 years).

The science of tephrochronology is also new since Halldor Laxness's effort; it uses the Greenland ice cores and other sources of information to date the layers of volcanic ash, or tephra, found like stripes in Iceland's soil. The lava field around Surtshellir rests on top of a tephra layer from an eruption dated to 871 (plus or minus 2 years).That means the earliest date for outlaws to have lived in the cave (and left cow-bones in their garbage) is about 880. A range of 880 to 960, Guðmundur Ólafsson notes, is roughly consistent with the stories in the Icelandic sagas.

Which is why Guðmundur is a little puzzled by what he and his colleagues found in the cave in 2013, according to a recent report from Iceland Review.

With Kevin Smith from Brown University and Agnes Stefánsdóttir of Iceland's Cultural Heritage Agency, Guðmundur had made a 3D scan of the Outlaw's Cave in 2012. This year, the team returned--with huge lights--to excavate the cave floor. "Because there's an increased flow of tourists to the cave, we considered it necessary to save these remains before they're completely destroyed," Guðmundur told Iceland Review.

They didn't find much besides animal bones. The outlaws weren't wealthy and they didn't live there long. But along with a few beads and scales made of lead, the archaeologists found "a small metal cross, probably made of lead but maybe of silver," Guðmundur said.

A cross? Although Iceland officially converted to Christianity in the year 1000, some of its first settlers were Christian. But the outlaws of Surtshellir? "The general view," said Guðmundur, "is that outlaws resided there around the year 1000, or in the 11th century, maybe. But they must have been Christian and that is a little strange."

The piles of bones they left, however, prove that they were a serious nuisance to the surrounding farms. There was no sign, in the form of fishbones or birdbones, that the outlaws even tried to support themselves by foraging. All the bones came from adult cows, horses, pigs, and sheep that could be rustled--or extorted--from the nearby farms.

The piles of bones they left, however, prove that they were a serious nuisance to the surrounding farms. There was no sign, in the form of fishbones or birdbones, that the outlaws even tried to support themselves by foraging. All the bones came from adult cows, horses, pigs, and sheep that could be rustled--or extorted--from the nearby farms.But neither were the outlaws living rich. They worked over those bones, getting every bit of meat off them, breaking them for the marrow. It must have been a hard life, deep underground, cold and damp, with a long, treacherous way to lug your firewood or face the unimaginable dark.

They had no headlamps. No serious shoes. And did I mention the constant annoying drip-drip-drip of water from the roof? Christian or pagan, there must have been a lot of praying going on in the Outlaws' Cave.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 11, 2013 08:49

September 4, 2013

The Viking Age: A Reader

The History Channel's The Vikings series, and especially the sexy Ragnar Lothbrok, inspired a number of my friends to ask, What one book should they (or their children) read to learn about Viking history? I was at a loss. How to choose among the dozens of Viking books on my shelves?

The History Channel's The Vikings series, and especially the sexy Ragnar Lothbrok, inspired a number of my friends to ask, What one book should they (or their children) read to learn about Viking history? I was at a loss. How to choose among the dozens of Viking books on my shelves?Then I bought The Viking Age: A Reader, published in 2010. If you read only one book about the Viking Age, this is the one.

It's not a book about the Viking Age. It's a book from the Viking Age. It contains excerpts from 35 texts that were written between 787 and the late 1200s in Arabic, Latin, Old Irish, Old English, and Old Norse.

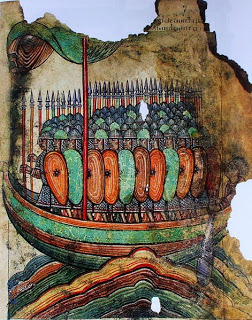

The Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, subject of my biography Song of the Vikings, is amply represented, as is his nephew, Sturla Thordarson (whom I called Saga-Sturla). For example, here are two passages from Sturla's Saga of Hakon the Old that give a nice picture of the dangers of travel in Viking ships:

King Hakon sailed along the coast of Jadar. As they approached Hvin, the steering oar on the king's ship broke, and almost the whole blade snapped off, but by using the gangplanks and the oars, they steered the ship south around the headland. When they had cleared the headland, they laid aside the gangplanks and steered into Skerdadarsound using the remains of the steering oar as well as the regular oars. The damaged steering oar was brought ashore when they came into port, and it seemed astonishing that such a large ship had been steered by such a small fragment of rudder.

And the second passage, from a voyage by Hakon's son, Magnus:

When they entered the harbor and dropped anchor, the momentum of the ship was so great that fire broke out in the windlass around which the cable was wound. The fear was that the rope would burn, so they soaked an awning, intending to stifle the fire with it, but Prince Magnus was much quicker and more resourceful. He lifted up a tub full of drink, poured it over the windlass, and cooled down the cable.

Ah, the uses of beer.

Another of Snorri's nephews, Olaf White-Poet, who lived many years at the Danish court, may have written Knytlinga Saga (The Story of the Family of Knut) about Canute the Great, king of England and Denmark. In it, we have the picture of the perfect Viking:

Knut was extremely tall and strong. He was an outstandingly handsome man, except for his nose, which was thin, high-set, and slightly crooked. He had a fair complexion and thick blond hair. His eyes were more beautiful than other people’s and his eyesight was keener. He was a generous man and a great soldier; he was gallant, victorious, and exceptionally fortunate in everything concerning power and wealth. But he was not a very reflective man, and the same is true of Svein, Harald, and Gorm before him. None of them were great thinkers.

True of the History Channel's Ragnar Lothbrok as well, I'd say.

Knytlinga Saga has not been fully translated into English. Neither has the Saga of King Hakon, one of our only sources for the life of Snorri Sturluson. For these little snippets alone I am grateful to Angus A. Somerville, one of the editors of The Viking Age: A Reader and translator of all the Old Norse excerpts. I hope he is inspired to translate the rest of these important sagas so that more people can read them.

I do read Old Norse, so the texts in The Viking Age: A Reader that are most important to me are those translated from Latin, Arabic, Old Irish, and Old English. For example, historians writing about the Viking attack on the English monastery of Lindisfarne in 793--often considered the beginning of the Viking Age--usually quote this phrase from a letter written that same year by the scholar Alcuin to King Athelred:

I do read Old Norse, so the texts in The Viking Age: A Reader that are most important to me are those translated from Latin, Arabic, Old Irish, and Old English. For example, historians writing about the Viking attack on the English monastery of Lindisfarne in 793--often considered the beginning of the Viking Age--usually quote this phrase from a letter written that same year by the scholar Alcuin to King Athelred:Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made.

But I've rarely seen quoted the middle of Alcuin's letter. Here it becomes clear that the Northumbrians were well acquainted with that "pagan race" who came by sea. The attack was terrible and surprising not because the English had never seen a Viking ship, but because God had allowed this holy place, this "place more venerable than all in Britain," to be "given as prey to pagan peoples."

Why would God allow this? Alcuin has an answer: Because the English had forgotten Christian charity. They had become like pagans themselves.

Wrote Alcuin to King Athelred:

Look at your trimming of the beard and hair, in which you have wished to resemble the pagans. Are you not menaced by terror of them whose fashion you wished to follow? What also of the immoderate use of clothing beyond the needs of human nature, beyond the custom of our predecessors? The princes' superfluity is poverty for the people. Such customs once injured the people of God, and made it a reproach to the pagan races, as the prophet says: 'Woe to you, who have sold the poor for a pair of shoes,' that is, the souls of men and women for ornaments for the feet. Some labor under an enormity of clothes, others perish with cold; some are inundated with delicacies and feastings like Dives clothed in purple, and Lazarus dies of hunger at the gate. Where is brotherly love?

The Viking Age doesn't seem so long ago after all. Just replace "the princes" with "the one percent" and we could still say that "The princes' superfluity is poverty for the people."

The Viking Age: A Reader was edited by Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald and published by the University of Toronto Press in 2010. For teachers there's a new companion volume, The Vikings and Their Age (University of Toronto Press, 2013), that essentially provides a syllabus by placing the excerpts in The Viking Age: A Reader into a broader context.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 04, 2013 07:21

August 28, 2013

The Viking Art of Poetry

One thing I love about Iceland is how alive the medieval world remains. City streets, candy bars, and beers are named for Norse gods and saga heroes. Ordinary Icelanders--in this case a civil engineer--can teach an expert in Old Norse literature (me) something about Viking poetry.

One thing I love about Iceland is how alive the medieval world remains. City streets, candy bars, and beers are named for Norse gods and saga heroes. Ordinary Icelanders--in this case a civil engineer--can teach an expert in Old Norse literature (me) something about Viking poetry.What are the "songs" in Song of the Vikings? When I talk about the book, I try to explain that Vikings were not only fierce warriors, they were very subtle poets. Because of the work of Snorri Sturluson and his followers, we know the names of over 200 Viking skálds. We can read hundreds of their verses: In the standard edition, they fill 1,000 two-column pages. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking Age.

The big surprise is how much they adored poetry--and how hard they worked at it.

I burned seaweed on the beach. I flung kelp to the red flame. Strong, thick smoke began to reek. That was a short time ago. --an anonymous 11th-century verse translated freely by Roberta Frank.

Skaldic poetry is a sophisticated art. The rules are more convoluted than those for a sonnet or haiku. In the most common form, a stanza had eight lines. Each line had six syllables and three stresses. The rhythm was fixed, as were the patterns of rhyme and alliteration.

The music of a line was of utmost importance--these poems really were "songs," even though we don't know if they were "sung" or chanted or just recited. A skaldic poem was designed to please the ear. It was first a sound-picture, though in a great poem sound and meaning were inseparable.

The steed runs in the gloaming,

famished, over long paths.

The hoof can wear out the ground

that leads to houses--we have little daylight.

Now the black horse carries me over streams,

distant from Danes.

My swift one caught his leg

in a ditch--day and night converge.

--by Sighvatr Þórðarson, c. 1035, translated by Peter Foote and David M. Wilson.

The steed runs in the gloaming,

famished, over long paths.

The hoof can wear out the ground

that leads to houses--we have little daylight.

Now the black horse carries me over streams,

distant from Danes.

My swift one caught his leg

in a ditch--day and night converge.

--by Sighvatr Þórðarson, c. 1035, translated by Peter Foote and David M. Wilson.A skaldic poem was a cross between a riddle and a trivia quiz. Each half-stanza of a poem contained at least two thoughts. These could be braided together so that the listener had to pay close attention to the grammar (not the word order) to disentangle subject, object, and verb. The riddle entailed disentangling the interlaced phrases so that they formed two grammatical sentences.

The quiz part was the kennings. Nothing was stated plainly. Why call a ship a ship when it could be “the otter of the ocean"? Snorri Sturluson defined kennings in his Edda, which he wrote as a handbook on Viking poetry. “Otter of the ocean” is a very easy one. As Snorri explained, there are three kinds of kennings: “It is a simple kenning to call battle ‘spear clash’ and it is a double kenning to call a sword ‘fire of the spear-clash,’ and it is extended if there are more elements.”

The king gives currents of yeast --that is what I judge ale to be--to men Men’s silence is dispelled by surf --that is old beer--of horns. The prince knows how speech’s salvation --that is what mead is called--is to be given. In the choicest of cups comes --this is what I call wine--dignity’s destruction.--Snorri Sturluson, c. 1220-41, translated by Anthony Faulkes.

Kennings are rarely so easy to decipher as these. Most kennings refer—quite obscurely—to pagan myths, which is why Snorri filled his Edda with stories of gods and giants. He knew that once these stories were forgotten, Viking poetry would die.

When I lecture on Song of the Vikings, I like to use an example from the book Snorri Sturluson and the "Edda" by Kevin Wanner, a professor at Western Michigan University. Wanner gives this literal prose translation of one of Snorri’s own verses:

The noble hater of the fire of the sea defends the woman-friend of the enemy of the wolf; prows are set before the steep brow of the confidante of the friend of Mimir. The noble, all-powerful one knows how to protect the mother of the attacker of the worm; enjoy, enemy of neck-rings, the mother of the troll-wife’s enemy until old age.

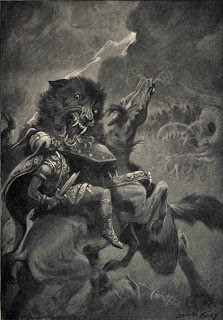

Who is the hater of the fire of the sea? Who is the enemy of the wolf? Who is the friend of Mimir? What does it all mean? As Wanner notes, you need to know five myths and the family trees of two gods or the poem is nonsense. Take away all the kennings, and the poem means simply, “A good king defends and keeps his land.” But then you lose all the poetry.

Kennings were the soul of skaldic poetry. Roberta Frank, in her book Old Norse Court Poetry, speaks of the “sudden unaccountable surge of power” that comes when she finally perceives in the stream of images the story they represent.

For example, here is "the enemy of the wolf": Odin, fighting the giant wolf Fenrir at Ragnarok, in an illustration by Deborah Hardy from 1909.

Kennings also make the music--the song--of skaldic poetry. With infinite ways of saying the same thing--"A good king defends and keeps his land."--the rules for rhyme, rhythm, and alliteration become, not restrictions, but spurs or challenges. They are the medium of the poet's art.

They are also what's first lost when a skaldic poem is translated. There are no songs, no music in Song of the Vikings because I wrote only in English, not in Old Norse. And there is no music (or at least a very different, modern music) in the translations of skaldic poems I've included here. Unless you hear the poem read in Old Norse, you're not hearing a Viking song.

Last May, I learned in the usual serendipitous way how to explain what was missing. I had gone to a symposium at Oddi, site of the school where Snorri Sturluson studied skaldic poetry and began collecting it. On the way home I shared a two-hour car ride with the civil engineer and former member of parliament Guðmundur Geir Þórarinsson, his son, and two friends, one of whom was a retired economist. To pass the time, the civil engineer and the economist engaged in a verse-capping contest: One recited the first lines of a poem, the other had to finish, or cap, it by reciting the next lines. (Icelanders from all walks of life still enjoy poetry.)

Last May, I learned in the usual serendipitous way how to explain what was missing. I had gone to a symposium at Oddi, site of the school where Snorri Sturluson studied skaldic poetry and began collecting it. On the way home I shared a two-hour car ride with the civil engineer and former member of parliament Guðmundur Geir Þórarinsson, his son, and two friends, one of whom was a retired economist. To pass the time, the civil engineer and the economist engaged in a verse-capping contest: One recited the first lines of a poem, the other had to finish, or cap, it by reciting the next lines. (Icelanders from all walks of life still enjoy poetry.) So that I would not feel left out, Guðmundur attempted the same game with me, using lines from Shakespeare. He knew a lot more Shakespeare by heart than I did.

Seeing that this attempt to entertain me had failed, and knowing that I had written about Snorri Sturluson, Guðmundur turned the conversation to skaldic verse. He wrote out on the back of an envelope some English poems composed by an Icelander, Sigurður Norlund, to explain the complicated verse structure. Here is one of them:

Free your heart where fountains boil from the dart of sorrow Long apart from loathful toil Live for art tomorrow.

Guðmundur read it aloud, accentuating the stresses: FREE your HEART … He circled every "f" in the first two lines and every "l" in the second two to explain the pattern of alliteration. He underlined the end rhymes (boil, toil) and internal rhymes (heart, dart, apart, art).

As poetry, it was insipid--all sound, no sense, no kennings (unless you can count "dart of sorrow"). But as a lesson in poesy it was sublime. I took the envelope home as a souvenir.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 28, 2013 07:16

August 21, 2013

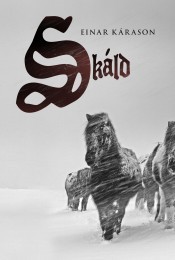

Einar Kárason's Skáld

In May I had lunch with the Icelandic novelist Einar Kárason. His uncle introduced us, knowing we both had published books about the 13th-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, mine nonfiction (Song of the Vikings) and Einar's fiction (Skáld).

In May I had lunch with the Icelandic novelist Einar Kárason. His uncle introduced us, knowing we both had published books about the 13th-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, mine nonfiction (Song of the Vikings) and Einar's fiction (Skáld).I'd heard about Einar's book. You won't like it, my Icelandic friends had warned. His Snorri is not your Snorri. Snorri Sturluson is not the main character in Skáld, but much in the shadow of his nephew, Sturla Thordarson. If you've read Song of the Vikings, you'll know I never much cared for that nephew.

Sturla wrote part of Sturlunga Saga and The Saga of King Hakon, our only direct sources of information about Snorri's life. As I wrote in Song of the Vikings, "In neither book does Snorri come off well; no one knows what grudge the nephew held to portray his uncle so poorly. Unhelpfully, Sturla’s two sagas also contradict each other."

It's the mark of a great novelist that he or she can change your mind. Having now read Einar's Skáld, I feel quite differently about Sturla. Think of what Hilary Mantel did for Thomas Cromwell's reputation in Wolf Hall. Einar Kárason's Skáld does the same for Sturla Thordarson.

I'm not ready to call Sturla a better writer than Snorri Sturluson. And I still feel Sturla (and Einar) portrayed Snorri poorly. But now I understand why Sturla wrote the way he did. I understand the conflicts he was dealing with, the encroachments of the world, the desires and threats, the yearning for peace and quiet and an unending supply of parchment, the loves and hates and little acts of friendship that motivated him, his ambition, his ego, his inadequacies, his grudge. In Skáld, Snorri's nephew becomes real.

It's fiction. Don't forget that. Einar, as a novelist, has a license I did not when writing Song of the Vikings. Einar can--and does--stretch the facts, make leaps of interpretation, draw conclusions that don't hold up to scholarly investigation. It's fiction.

And yet…

The Saturday after our lunch date, I heard Einar give a lecture. I could not follow all of it--I understand written Icelandic much better than spoken. But Einar also gave me a copy of an article he had written in Skirnir, the journal of the Icelandic Literary Society.

He was arguing that Sturla Thordarson also wrote Njal's Saga, the best of the Icelandic sagas, widely acknowledged a masterpiece of world literature, the first saga I had read and the one that (along with Snorri's Edda) had inspired me to devote my life to Icelandic literature.

He was arguing that Sturla Thordarson also wrote Njal's Saga, the best of the Icelandic sagas, widely acknowledged a masterpiece of world literature, the first saga I had read and the one that (along with Snorri's Edda) had inspired me to devote my life to Icelandic literature.In Skirnir, Einar goes to great pains to point out that other people have had this idea before him. Other scholars have pointed out the many similarities between Njal's Saga and those in Sturlunga Saga: similarities in names, in the way characters are introduced, in whole scenes (the burning of Njal, the burning of Flugumyri). To these Einar added similarities in style, in pacing and structure, and most of all, in voice.

Lecturing, Einar is very dramatic. His expressions are exaggerated, his gestures wide. He stamps back and forth before the podium in his motorcycle boots. He runs his fingers through his long, graying hair. He's a big man. His voice booms. Writing in the journal Skirnir, he borrows some of that bombast.

In Skáld, he is very subtle. The story builds slowly, told through many different voices. It's not a long book. But no one knows better than a novelist that by making it real, by bringing Sturla Thordarson to life as the author of all these works, Einar has made his case.

Once you have fully imagined Sturla engaged in composing Njal's Saga--by reading Einar Kárason's Skáld--it's hard to go back to thinking it's only a theory.

Skáld, I'm sorry to say, is currently available only in Icelandic. You can order it from the publisher, Forlagid, here: http://www.forlagid.is/?tag=einar-karason

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 21, 2013 08:35

August 14, 2013

Purple Parchment and the Cave of Smoo

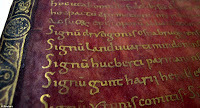

In the year 997, the excommunicated archbishop of Reims sent the Holy Roman Emperor a kingly gift: a copy of Boethius's On Arithmetic written in gold and silver inks on purple parchment. It had the desired effect. As I wrote in The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages, my biography of that archbishop, the 17-year-old emperor summoned Gerbert of Aurillac to court with the plea, "Pray explain to us the book on arithmetic." Archbishop Gerbert became the emperor's tutor, friend, counselor--and ultimately, through the emperor's influence, Pope Sylvester II, the pope of the Year 1000.

In the year 997, the excommunicated archbishop of Reims sent the Holy Roman Emperor a kingly gift: a copy of Boethius's On Arithmetic written in gold and silver inks on purple parchment. It had the desired effect. As I wrote in The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages, my biography of that archbishop, the 17-year-old emperor summoned Gerbert of Aurillac to court with the plea, "Pray explain to us the book on arithmetic." Archbishop Gerbert became the emperor's tutor, friend, counselor--and ultimately, through the emperor's influence, Pope Sylvester II, the pope of the Year 1000.Earlier in this blog, I described how parchment and ink were made in the Middle Ages. (See "How to Make a Medieval Book, Part I" and "How to Make a Medieval Book, Part II.")

But purple parchment? How did they color the parchment purple? I hadn't given that much thought.

Then the other day, researching something quite unrelated--the Viking settlements in northern Scotland--I stumbled upon the answer.

In 1992, a team of archaeologists led by Tony Pollard excavated four neighboring caves in a narrow inlet in Sutherland, one being the famous Smoo Cave. (See the great website, from which these photos of the cave were taken, at www.smoocave.org) In 2005, Pollard posted their report online at www.sair.org.uk/sair18.

"Smoo" comes from the Old Norse word smuga, which Cleasby-Vigfusson, the classic Old Icelandic dictionary, defines as "a narrow cleft to creep through, a hole." The related verb is smjúga, "to creep through a hole" of which the past tense is smaug. Bells are now going off in the heads of all Tolkien readers--but I won't be following that digression any farther.

Back to Smoo Cave. Surprisingly, I had visited the cave in 1995. Two balding Scotsmen with rat tails and earrings took me on a river raft under a low stone arch, across a pool into which a sun-sparkled waterfall fell. In the dark cave, it was a real surprise. We disembarked in the dry inner reaches of the cave and had a geology lesson. The outer, larger cavern was made by the sea: the hole, wider at the bottom than the top, is a blowhole. The inner caverns were made by an underground river that feeds from a large lake. The waterfall only runs when there’s been rain—today’s fall is last night’s rain.

Back to Smoo Cave. Surprisingly, I had visited the cave in 1995. Two balding Scotsmen with rat tails and earrings took me on a river raft under a low stone arch, across a pool into which a sun-sparkled waterfall fell. In the dark cave, it was a real surprise. We disembarked in the dry inner reaches of the cave and had a geology lesson. The outer, larger cavern was made by the sea: the hole, wider at the bottom than the top, is a blowhole. The inner caverns were made by an underground river that feeds from a large lake. The waterfall only runs when there’s been rain—today’s fall is last night’s rain. As Pollard points out, Smoo Cave has been a tourist attraction since at least the early 1700s. One practical-minded traveler described it as "stretching pretty far underground with a natural vault above." Inside, "there is room enough for 500 men to exercise their arms." (I'm imagining jumping jacks here--but maybe he means to practice their shooting?) There's "a harbor for big boats" at the cave's mouth, a pool full of trout, and "a spring of excellent water."

Earlier visitors also valued the cave for its usefulness--not its surprising bright waterfall. Pollard and his crew of archeologists found signs that Vikings had used Smoo Cave as a fishing camp, as well as a place to sit out a storm and repair a boat. They may have stopped here on their way from the Orkney Islands to Dublin. They butchered animals and cooked them. They ate dried fish they'd brought with them. They ground grain. They carved pins and knife handles and other useful objects out of antler and bone.

But the most interesting thing the Vikings did at Smoo and its neighboring caves was collect and crack open whelks. These were not just any whelks, but Nucella lapillus, also known as Purpura lapillus, the source since antiquity of a purple dye. These whelks are not edible, and they were not used as fish bait, Pollard says. "It is clear that purple dye was being extracted from the shells recovered from the cave."

The whelks, Pollard writes, "had been split from the second and third whorl and also split from the shoulder to the base.... This would have facilitated the removal of the animal from its shell to extract the ink."

The whelks, Pollard writes, "had been split from the second and third whorl and also split from the shoulder to the base.... This would have facilitated the removal of the animal from its shell to extract the ink."In 1895, archaeologists found "Purpura-mounds" in Connemara, Ireland. The shells in the mounds had been broken exactly like those in Smoo Cave, though in Ireland there were many more of them. One heap measured 165 by 45 feet. In one square foot, the researchers counted two hundred whelks. Purpura-mounds have also been found in Cornwall, England, but Smoo Cave is the first record from Scotland, although the whelk is common there.

To learn how to make the dye known as Tyrean purple, Pollard refers the reader to the 1919 book, Shells as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture by J.W. Jackson. Like Pollard's own report, Jackson's book is available online. (Historical research is so easy these days!)

Jackson, in turn, cites the first-century Roman writer Pliny to explain that "the precious liquid was obtained from a transparent branching vessel behind the neck of the animal and that at first the material was of the colour and consistency of thick cream."

Several kinds of whelks produced purple dye. Small ones were smashed together in a mortar; if large, "the animal was taken out entire, usually by breaking a hole in the side of the shell, and the sac containing the colouring matter was taken out, either while the animal was still alive, or as soon as possible after death, as otherwise the quality of the dye was impaired." The sacs were salted, allowed to sit for three days, then boiled and frequently skimmed. Exposed to the sun, the fluid (smelling like garlic) slowly changed color, from creamy to yellow, green, blue, and finally a purplish red. After ten days, the dye was ready to use.

To dye wool, a clean fleece was dunked into the boiling dye pot and left to soak for five hours. It was taken out, cooled, and the wool plucked off and carded, only to be "thrown in again, until it had fully imbibed the colour" (still smelling like garlic--one reason the wearers of royal purple robes wore so much perfume, suggests Jackson). It took between one and two pounds of liquid dye to color a half-pound of yarn.

To turn parchment purple, Jackson says, the dye was used as a paint, applied with a brush. The "magnificent and expensive style of writing" on purple parchment with gold and silver inks was mostly confined to sacred texts. Jackson cites an English Bible and a Gospel book, another book of the Gospels commissioned by Louis the Pious, king of France from 814 to 840, and a Book of Prayers, "bound in ivory and studded with gems" owned by his son, King Charles the Bald.

To turn parchment purple, Jackson says, the dye was used as a paint, applied with a brush. The "magnificent and expensive style of writing" on purple parchment with gold and silver inks was mostly confined to sacred texts. Jackson cites an English Bible and a Gospel book, another book of the Gospels commissioned by Louis the Pious, king of France from 814 to 840, and a Book of Prayers, "bound in ivory and studded with gems" owned by his son, King Charles the Bald.It's significant that Gerbert of Aurillac, who would become "The Scientist Pope," owned a mathematical treatise made in this "magnificent" style. The book still exists in the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg in Germany, where it is catalogued as MS Bamberg Class. 5 (HJ.IV.12), but we don't know how it came into Gerbert's possession. Like the gem-studded prayer book, On Arithmetic was commissioned by King Charles the Bald in about 832. But the dedicatory verses apply equally to the young emperor Otto III as to King Charles, and scholars long thought Gerbert (known as a poet) had written them. Otto III may have thought so too, for he answered the gift with a verse.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 14, 2013 11:50

August 7, 2013

The Gift of Kindness

Kindness is the name of my mare, Gaeska in Icelandic. In my book A Good Horse Has No Color, I wrote about going to Iceland and buying her and my gelding, Birkir, in 1997, but I didn't write about the surprise Gaeska brought home: a foal.

Kindness is the name of my mare, Gaeska in Icelandic. In my book A Good Horse Has No Color, I wrote about going to Iceland and buying her and my gelding, Birkir, in 1997, but I didn't write about the surprise Gaeska brought home: a foal.The day my two horses were to be released from quarantine, I got a phone call from Gaeska's breeder. It was early in the morning, and we spoke Icelandic, as she and I mostly had with each other. But now I was out of practice and found it a lot harder to understand. She was asking something about Gaeska. "Yes," I said, "she made it to New York. She gets out of quarantine today."

"You must have her checked. You should have them sprauta her at the quarantine center if you can."

"Oh yes, I'm sure they check her for everything." I didn't know what sprauta meant, so I ignored it.

"Well she can be fine and have a foal in her at the same time! We're very sorry about it. We'll pay what it costs to have it done, but you have to do it soon or it's bad for Gaeska. We were so surprised when the vet called and asked if we still needed that appointment. We'd completely forgotten Gaeska was one of those mares."

She rattled on and on. I was taking deep breaths and trying to calm down. I'd never owned a horse before and was still working out the details of barn design and hay delivery and vets and shoeing. Now I had to learn to raise a foal?

Photo by Gerald Lang and Jennifer Anne Tucker

Photo by Gerald Lang and Jennifer Anne TuckerA week before I came to Skagafjord, the breeder said, there'd been a big horse show a few miles away from the farm. The family had ridden to the show, one of them taking Gaeska. She'd been pastured with the other mares. One night, a stallion broke loose and jumped the fence. He spent the night with the mares. "It was all a terrible accident," the breeder said. The vet was checking all 20 mares that had been in the pasture and would sprauta any that were pregnant in order to abort the foals.

"Who was the stallion?" I asked. "Why do you need to abort the foals?" This was Skagafjord, after all. I began thinking about the famous stallions that could have been at that horse show.

"It was not a good stallion," she said, "not an evaluated stallion, just some farmer's riding horse." There was nothing wrong with the stallion. He was pretty, a chestnut, five-gaited, five years old. But horse breeding in Iceland is highly scientific. Breeding horses are evaluated on 10 points of conformation and 10 tests of ability under saddle. A stallion who scores less than a total of 8 out of 10 is gelded--he has no future as a stud in a land with hundreds of "first prize" stallions.

Not to mention that raising a foal is expensive. Icelandic horses aren't trained to ride until they are four or five years old--which means you pay to feed them for four years before you even know if you have a good riding horse. Gaeska's breeder sounded astonished that I would even consider raising what she called "a worthless foal" by an unrated stallion.

The vet where I boarded the mare when she came out of quarantine made the decision for me. "I don't do that," she said, with extreme distaste. She refused to even do a pregnancy test when she knew I was considering aborting the foal.

I conferred with Anne Elwell, a longtime breeder of Icelandic horses in New York, who assured me it was "not a problem." She doubted the pregnancy would take, the mare was under such stress--taken from her farm, put on an airplane, hustled through quarantine--all within three weeks of being bred. It's hard to bring foals over in utero when you want to, she said. And, in any case, Icelandics don't generally need any help foaling, so if she was pregnant I needn't worry. "Feed the mare well, she'll take care of the foal. You can ride her until she waddles."

Two months later, when I brought Gaeska closer to my home, I had my own vet check her. "She's about three months," she said. She looked surprised at the expression on my face. "You were expecting me to say that, weren't you?" She laughed as I told her the story. "Had a little fling, eh girl?" she said, petting the mare. "You were mad they were going to sell you, weren't you? You said, 'I'll show them. I'll take a little bit of Iceland with me!' "

Sometimes, even in horsebreeding, you get lucky. Gaeska foaled with no problem. Her colt, Elvar, was as we say "a pistol." The first thing he did was stick his head in the water bucket and shake all the water onto the floor. At a week old, he began to snort and whinny back to his mother. He also discovered the canter, and began rocketing around the paddock. When I scrubbed algae out of the water tub, he came over and stuck his nose in the bucket of soap suds. He did the same when I held a halter under his nose, and let me slip it on him with no effort.

I knew I couldn't keep him. Icelandics need to grow up in a herd. So when he was weaned, I found Elvar a foster-home in Canada. Soon after that, the herd was broken up; Elvar (with my approval) and several other horses were sold to someone who wanted to start an Icelandic horse farm of their own, and I lost touch with Gaeska's foal for several years. I often wondered how he was doing--if he was "worthless" after all.

Enter Facebook. Early in 2012, browsing among Icelandic horse friends and friends-of-friends, I saw a photo of a very shaggy, dark-bay Icelandic horse being ridden in the snow. It looked amazingly like Gaeska. The caption read, "Another beautiful day to ride! Me and Elvar, better known as 'the big comfy couch.'" The rider was Wendy Sheppard-Horas. I checked the transfer papers--yes, I had sold Elvar to Wendy Horas, now the proud owner of OnIce Horse Farm (Ontario Icelandic Horse Farm). I contacted her and was delighted to learn that Elvar was "the best horse in the world. You can ask him to do anything and he will! He is the most respectful horse I know. I wish I had a dozen of him… He is a very big part of our farm."

More photos of Elvar appear on the OnIce Horse Farm Facebook page: One shows Elvar lying down in the snow with a young girl sitting on him--no saddle, no bridle, she's not riding him, just sitting on him like he was a couch. A big comfy couch, indeed! The caption: "Sydney on Elvar. It really doesn't matter to him … he is so easy going."

It gets better. This week Sydney Horas is representing Canada as a youth rider in the Icelandic Horse World Championships in Berlin, Germany. I like to think that having a horse like Elvar to grow up riding had something to do with Sydney's success as an equestrienne. Please pardon me if I root for Canada when she is on the track.

You can follow the Icelandic Horse World Championships on Facebook at Islandpferde-WM 2013 or on the web at www.berlin2013.de or find results on the FEIF website.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 07, 2013 08:39

July 31, 2013

A Viking Ship Named Snorri

The Icelandic name Snorri, which I admit I cannot properly pronounce, seems to follow me about. I first went to Iceland in 1986 thinking of writing a novel about Snorri, the chieftain of Helgafell in Eyrbyggja Saga. Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir, heroine of my 2007 nonfiction book The Far Traveler, had a son named Snorri, born while Gudrid and her husband Thorfinn Karlsefni explored North America just after the year 1000. My latest book, Song of the Vikings, is the biography of a third Snorri, the 13th-century poet and politician Snorri Sturluson, who gave us Norse mythology as we know it.

The Icelandic name Snorri, which I admit I cannot properly pronounce, seems to follow me about. I first went to Iceland in 1986 thinking of writing a novel about Snorri, the chieftain of Helgafell in Eyrbyggja Saga. Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir, heroine of my 2007 nonfiction book The Far Traveler, had a son named Snorri, born while Gudrid and her husband Thorfinn Karlsefni explored North America just after the year 1000. My latest book, Song of the Vikings, is the biography of a third Snorri, the 13th-century poet and politician Snorri Sturluson, who gave us Norse mythology as we know it.Now a fourth Snorri comes into my life. While on tour for Song of the Vikings last November, I gave a lecture at the University of Southern Maine in Portland. There to meet me was Rob Stevens, famous for building a Viking ship replica named, yes, Snorri. Granted the ship was named after Gudrid the Far-Traveler’s son, but still, another Snorri.

Rob was a bit of a Santa: big white beard, big round belly, round blue eyes with the requisite sparkle. He had two silver rings in his left ear, one in the right. A curly ponytail. His hands were strong and notably banged up, the hands of a woodworker.

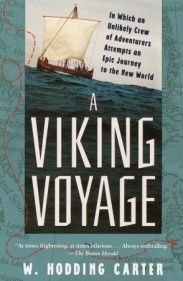

I knew all about him from Hodding Carter’s 2000 book, A Viking Voyage, which has one of those subtitles that need no further explanation: In which an unlikely crew of adventurers attempts an epic journey to the New World. In spite of reading like a farce, Carter’s book supplied me with wonderful background material for Gudrid the Far-Traveler’s experiences sailing in a Viking ship across the North Atlantic eight times.

I knew all about him from Hodding Carter’s 2000 book, A Viking Voyage, which has one of those subtitles that need no further explanation: In which an unlikely crew of adventurers attempts an epic journey to the New World. In spite of reading like a farce, Carter’s book supplied me with wonderful background material for Gudrid the Far-Traveler’s experiences sailing in a Viking ship across the North Atlantic eight times.Rob, in the book, did not come across as a hero. Carter wrote of “Rob’s moodiness and tendency toward being a loose cannon,” while acknowledging that “even if half of what he spewed was bullshit, he still probably knew more about traditional boatbuilding than anyone alive.”

“What’s it like to be written about—especially in a funny book?” I asked him.

He shrugged. At first he had been annoyed. Then he’d compared notes with the others on the crew, and none of them had liked what Carter had written about themselves either. So it was probably all true.

Now Rob shared with me a new book: Paul T. Cunningham’s Building a Viking Ship in Maine (Just Write Books 2012), a photo essay that chronicles the building of Snorri out of oak, pine, locust, tamarack, willow, and iron. The ship was a copy of a knarr, or Viking merchant ship, found in the harbor at Roskilde, Denmark some years ago. It is 54 feet long, 16 feet wide, and 6 feet deep. Rather tubby compared to the long, sleek dragonships we’re used to thinking of as Viking ships.

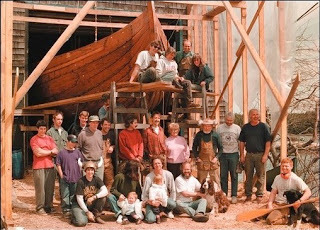

It also seems a little small for an ocean-crossing knarr. On pages 110-111 of Cunningham’s book, Snorri is in the water, surrounded by rowboats and canoes; a phalanx of motorboats waits further offshore. The blacksmith who made the rivets, a husky guy in a plastic horned helmet, poses at an oar, two other fake “oarsmen” (is one a woman? hard to tell) pose behind him, while the rest of the crew and their families look like the tourists they are, sitting on the gunwales, lounging hands-in-pockets amidships. It’s quite a crowd: Packed in, with little room to move are at least 41 people (a couple more children might be tucked in, invisible). In Eirik the Red’s Saga, Thorfinn Karlsefni is said to come to Greenland on a knarr, or merchant ship, with 40 men aboard; his partner, another Snorri, had a second ship with 40 men. Traveling to Vinland, Karlsefni is said to have taken three ships and a total of 160 people. Looking at this photo of Snorri, the saga account doesn’t seem possible, unless Snorri is an unusually small knarr.

It also seems a little small for an ocean-crossing knarr. On pages 110-111 of Cunningham’s book, Snorri is in the water, surrounded by rowboats and canoes; a phalanx of motorboats waits further offshore. The blacksmith who made the rivets, a husky guy in a plastic horned helmet, poses at an oar, two other fake “oarsmen” (is one a woman? hard to tell) pose behind him, while the rest of the crew and their families look like the tourists they are, sitting on the gunwales, lounging hands-in-pockets amidships. It’s quite a crowd: Packed in, with little room to move are at least 41 people (a couple more children might be tucked in, invisible). In Eirik the Red’s Saga, Thorfinn Karlsefni is said to come to Greenland on a knarr, or merchant ship, with 40 men aboard; his partner, another Snorri, had a second ship with 40 men. Traveling to Vinland, Karlsefni is said to have taken three ships and a total of 160 people. Looking at this photo of Snorri, the saga account doesn’t seem possible, unless Snorri is an unusually small knarr.But other than its carrying capacity, Snorri proved it was fully up to the task of discovering America in about the year 1000—with a little remodeling. Unlike other replica ships like Gaia, on which I took a pleasure cruise in Newport Harbor in 1991, Snorri had no back-up diesel engine, no enclosed cabin, no chase boat. The crew were totally exposed to the elements—the way the Vikings were—and totally reliant on the ship’s sail and oars. Not being totally insane, however, Carter did allow modern communications technology aboard. Otherwise, there might have been no story to tell.

On their first attempt to cross the Davis Strait, Carter wrote, “Our huge rudder had loosened a supporting crossbeam, a thigh-thick piece of wooden framing, by constantly pulling forward on it, instantly creating four holes in the bottom of the boat. Water gushed in…” They radioed for help. The coast guard towed Snorri back to Greenland and Rob flew to Denmark to consult with the experts at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde on rudder design.

The Danes weren’t a lot of help. Recalling his trip to me last November, Rob shrugged. “There’s a series of books called Culture Shock. I wish I’d read the one about the Danes before I went there. I’m just a boatbuilder. I thought they’d say, ‘Boy, oh, boy, another Viking ship!’” They didn’t. In fact, Rob thought they were giving him the shove-off. “After I read the book, I realized that they were being really helpful. They’d say, ‘This is all we will do for you’ and I now I realize they meant, ‘This is all we can do for you.’ It’s a huge difference in English.”

From Building a Viking Ship in MaineEssentially, no one really knows how to build a Viking ship—or how to fit one with the correct rudder. All the Viking ship replicas built are examples of experimental archaeology, a fancy term for trial and error.

From Building a Viking Ship in MaineEssentially, no one really knows how to build a Viking ship—or how to fit one with the correct rudder. All the Viking ship replicas built are examples of experimental archaeology, a fancy term for trial and error.“The hardest thing about building Snorri,” Rob told me, “was organizing people. The vast majority of it was done the same way we built boats a hundred years ago. The only difference is if you’re using electricity or not. And electricity makes us lousy woodworkers.” The Vikings, he believes, could build a ship much more quickly than we can now. “Take the laziest person in the world,” said Rob, meaning in the Viking world: “Their tools were sharp. They knew how to measure and then cut to the line. Now you cut and grind it down to the line and it takes forever.”

In one of Cunningham’s photos, Rob uses an adze to shape the stern. Reads the caption, "Sometimes in wooden boat building, the older tools are the right ones to use." Elsewhere, another craftsman uses a modern router to shape a floor timber. If the Viking’s had one, they would have used it. It was a common refrain, Cunningham noted. The builders of Snorri weren’t purists.

But they were brave. Reading about Rob’s experiences sailing Snorri from Greenland to Newfoundland convinced me I would never (as I had once threatened) talk my way onto a replica Viking voyage. Remembering that time the “water gushed in,” Carter wrote: “We were more than 130 miles from Greenland, adrift. All that bashing and groaning I had so cherished had taken its toll. Some of the crew were falling apart. Rob was retching wherever he stood. Others were nearly as sick.”

But they were brave. Reading about Rob’s experiences sailing Snorri from Greenland to Newfoundland convinced me I would never (as I had once threatened) talk my way onto a replica Viking voyage. Remembering that time the “water gushed in,” Carter wrote: “We were more than 130 miles from Greenland, adrift. All that bashing and groaning I had so cherished had taken its toll. Some of the crew were falling apart. Rob was retching wherever he stood. Others were nearly as sick.”And again: “Walls of crashing water would tumble over you and then the wind finished you off. I stayed just warm enough in my wool clothes—just shy of hypothermia, really—but I was soaked to the bone. Dean took a hit that even Mike Tyson could not equal. He reeled around gasping for air. Rob became incapacitated and puked mightily…”

I would rather fall off a horse (and I have, repeatedly) than be seasick. When I asked about it last November, Rob laughed it off. “Great way to lose 40 or 50 pounds.” Then he added, “I want to convince the guys at Cape Cod to build another one and sail it back to Greenland.” Spoken like a true Viking. Let a little bit of discomfort get in the way of an adventure? Never.

The adventures of the ship Snorri are chronicled in three books. I recommend them all:

Hodding Carter’s A Viking Voyage (Ballantine 2000)

Carter’s An Illustrated Viking Voyage: Retracing Leif Eriksson’s Journey in an Authentic Viking Knarr, with photos by Russell Kaye (Simon & Schuster, 2000)

Paul Cunningham’s Building a Viking Ship in Maine (Just Write Books 2012).

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on July 31, 2013 07:34