Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 16

March 6, 2013

The History Channel "Vikings"

Did you see episode 1 of "The Vikings" on the History Channel last Sunday? If I had a TV I would have watched it--I've been besotted with Vikings since at least 1984, when I stood in awe of the Gokstad ship (at left). But what I read in the February 24 New York Times about the TV program made me wonder, How much of the History Channel's "Vikings" will be true to history?

Did you see episode 1 of "The Vikings" on the History Channel last Sunday? If I had a TV I would have watched it--I've been besotted with Vikings since at least 1984, when I stood in awe of the Gokstad ship (at left). But what I read in the February 24 New York Times about the TV program made me wonder, How much of the History Channel's "Vikings" will be true to history?"For the elaborate History project," wrote the Times reporter, script-writer Michael Hirst "immersed himself in what had been written about Viking culture--basically documentation by outside observers since theirs was an illiterate society. He found the material limited and biased. 'They're always the guys who break in through the door, slash up your house and rape and pillage for no good reason, except that they enjoy the violence,' he said. 'I wanted to tell the story from the Vikings' point of view, because their history was written by Christian monks, basically, whose job it was to exaggerate their violence.'"

Continued the Times reporter, "Despite History's mantle of preserving and purveying an accurate picture of the past, hewing to the letter of historical accuracy wasn't possible in the case of a dramatic series based on fragmented documentation, hence a large degree of dramatic license was employed. 'I especially had to take liberties with "Vikings" because no one knows for sure what happened in the Dark Ages,' Mr. Hirst said. 'Very little was written then.'"

Sigh. What Hirst said is literally true: "Very little was written then," and all of it by the Vikings' enemies. Nothing that I know of was written down in Scandinavia during the Viking Age, roughly 793 to 1066. As I argue in Song of the Vikings, the sagas that have done the most to establish our current image of the Vikings were written in the early 1200s by the Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson: Egil's Saga and the kings' sagas in Heimskringla.

I argue, as well, that Snorri was a creative artist, not what we'd think of as a historian. He made things up. Most modern readers recognize that when the great Viking warrior Egil Skallagrimsson says, "I'll give it a try, if you like, but I never expected to make a praise-song for King Eirik," the quote was made up. Egil died nearly 200 years before Snorri was born. No one in York, England in 948 had a voice recorder. There was no one taking dictation. Egil didn't write any letters home.

And yet, Egil (at left) did make that praise-song. It was memorized and passed down through the generations, only becoming "written" when it appeared in a manuscript of Egil's Saga. The same is true of Egil's response, when the king accepted the poem as a suitable apology for Egil's crimes and rewarded him with the gift of his own ugly head:

And yet, Egil (at left) did make that praise-song. It was memorized and passed down through the generations, only becoming "written" when it appeared in a manuscript of Egil's Saga. The same is true of Egil's response, when the king accepted the poem as a suitable apology for Egil's crimes and rewarded him with the gift of his own ugly head:Ugly as I, Egil, amI'm not in the wayOf refusing from a rulerMy rock-helm of a head:Was there ever an enemyWon such an elegantGift from a great-heartedGallant like Eirik?

"Very little was written then" in the Viking Age, but much was composed. As I've mentioned here before [link], we know the names of dozens of Viking poets, or skalds. We can read (or, at least, experts can) hundreds of their verses. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking age, what they loved, what they despised.

Snorri Sturluson depended on the words of the skalds to write his sagas. Few poems had been written down before his lifetime, so Snorri learned them the way skalds had for hundreds of years, by ear. He loved poetry and memorized a great deal of it. Egil's Saga contains three major poems, like "Head Ransom," and many minor ones. Heimskringla, Snorri's history of the kings of Norway, includes nearly 600 poems. In his Edda, which is about the art of poetry, Snorri quotes 373 verses by more than 60 poets--nor is that all the poetry Snorri knew: in the Edda, he quotes only single lines or half-stanzas, not whole poems.

Snorri himself discussed the relationship between poetry and history in the beginning of Heimskringla. Poems are more trustworthy than prose, he argued, if “correctly composed and judiciously interpreted.” The intricate rules of skaldic poems make them easy to memorize--change a word and the poem simply won’t work. (The rules also make skaldic poems impossible to translate well.) As Snorri wrote, “The words which stand in verse are the same as they were originally, if the verse is composed correctly, even though they have passed from man to man.” For this reason they were considered trustworthy historical sources even if hundreds of years old.

Often the poets were eyewitnesses to events. King Harald Fairhair, who united Norway and prompted the settlement of Iceland in the late 800s, for example, kept several poets at court. More than 300 years later, Snorri noted, “Men still remember their poems and the poems about all the kings who have since his time ruled in Norway.”

Often the poets were eyewitnesses to events. King Harald Fairhair, who united Norway and prompted the settlement of Iceland in the late 800s, for example, kept several poets at court. More than 300 years later, Snorri noted, “Men still remember their poems and the poems about all the kings who have since his time ruled in Norway.” King Olaf the Saint (in the illumination at left) made sure the three poets in his retinue were safe behind the shield wall at his last battle in 1030, so they could record his courageous death-scene for posterity. (In spite of his efforts, all three died; the poet who composed Olaf's elegy was in Rome when the battle was fought.)

To write his kings’ sagas, Snorri said, he sought out poems that were recited before the kings themselves or their sons, even though he was well aware that court poetry was propaganda. Poets always “give highest praise to those princes in whose presence they are,” Snorri admitted. “But no one would have dared to tell them to their faces,” he argued, “about deeds which all who listened, as well as the prince himself, knew were only falsehoods and fabrications.” That, he said, would be mockery, not praise.

With a budget "reported at $40 million" for the History Channel series, you'd think Michael Hirst might have stumbled upon the works of Snorri Sturluson and, through him, the poetry of the Viking skalds. It's not "documentation." But through skaldic poems, we can still hear the voice of the Vikings. We can get inside their heads and shed a little light on those Dark Ages. We don't have to make it all up.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And don't forget to enter the raffle for a free, autographed copy of Song of the Vikings. Details are in last week's post or click here.

Published on March 06, 2013 09:23

February 27, 2013

"Song of the Vikings" Giveaway

When I started this blog, I promised to explain why I named it "God of Wednesday." If you've followed me over the past year, you can probably guess. Now comes the quiz: Who is the god of Wednesday and what does he have to do with this blog?

When I started this blog, I promised to explain why I named it "God of Wednesday." If you've followed me over the past year, you can probably guess. Now comes the quiz: Who is the god of Wednesday and what does he have to do with this blog?Answer me by email (nancymariebrown@gmail.com) or Facebook or in the comment section below, and I'll print the best answers in a future blog.

When I get 50 responses, I'll put the names in a hat, and the winner will receive a free, autographed copy of "Song of the Vikings"--or, if you already have it, one of my other books (as available).

To make it a fair test, here are some blog posts from 2012 that might help you out:

April 4: "The Lord of the Ring of the the Nibelungs"

May 30: "The Homer of the North"

June 6: "The Most Influential Writer of the Middle Ages"

November 14: "Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn't Have Without Snorri: Part I"

November 21: "Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn't Have Without Snorri: Part II"

December 5: "Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn't Have Without Snorri: Part III"

December 12: "The Tolkien Connection"

Remember, all answers to the quiz are entered into the giveaway. Good luck, and be creative--maybe you can explain me to myself.

Join me again next Wednesday for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com

Published on February 27, 2013 11:45

February 20, 2013

The Spirit of the North

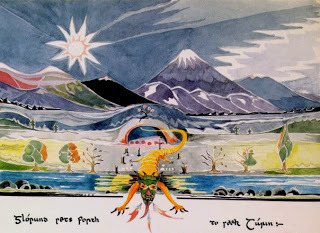

At the end of Song of the Vikings, I traced the effect of Snorri’s Edda and other medieval Icelandic literature on fantasy writers William Morris, J.R.R. Tolkien, and C.S. Lewis. They were smitten, writes Lewis, by “pure ‘Northernness.’”

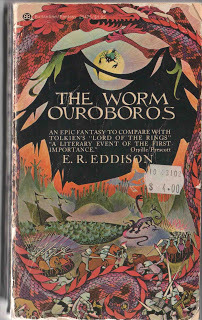

At the end of Song of the Vikings, I traced the effect of Snorri’s Edda and other medieval Icelandic literature on fantasy writers William Morris, J.R.R. Tolkien, and C.S. Lewis. They were smitten, writes Lewis, by “pure ‘Northernness.’”One writer I did not include, but should have, was E.R. Eddison.

I read Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, published in 1922, just after reading The Lord of the Ringsfor the first time. I clearly remember talking to my English teacher about Tolkien—I think I was in seventh or eighth grade—and asking, Are there any more books out there like his? She suggested The Worm Ouroboros.

Tolkien once called Eddison “The greatest and most convincing writer of invented worlds that I have read.” I wouldn’t go that far. But, looking back, Eddison and Tolkien may be the writers most responsible for my love, not of fantasy novels, but of “Northernness.” Rereading The Worm Ouroboros, my favorite part would have to be the introductory scene on page 2 of my tattered paperback:

…He had her hand in his. This was their House. “Should we finish that chapter of Njal?” she said. She took the heavy volume with its faded green cover and read: “He went out on the night of the Lord’s day, when nine weeks were still to winter; he heard a great crash, so that he thought both heaven and earth shook. Then he looked into the west airt and he thought he saw thereabouts a ring of fiery hue, and within the ring a man on a gray horse. He passed quickly by him, and rode hard. He had a flaming firebrand in his hand, and he rode so close to him that he could see him plainly. He was black as pitch, and he sung this song with a mighty voice— Here I ride swift steed, His flank flecked with rim, Rain from his mane drips, Horse mighty for harm; Flames flare at each end, Gall glows in the midst, So fares it with Flosi’s redes As this flaming brand flies; And so fares it with Flosi’s redes As this flaming brand flies.“Then he thought he hurled the firebrand east towards the fells before him, and such a blaze of fire leapt up to meet it that he could not see the fells for the blaze. It seemed as though that man rode east among the flames and vanished there… So he went and told Hjallti, but he said he had seen ‘the Wolf’s Ride, and that comes ever before great tidings.’” They were silent awhile…

Njal’s Sagawas the first saga I ever read—over Thanksgiving break in my second year of college, I believe. I don’t now recall if I recognized that passage from The Worm Ouroboros when I saw it in the original, but I do know that the fire-rider or volcano-spirit has long been one of my favorite images from medieval Iceland.

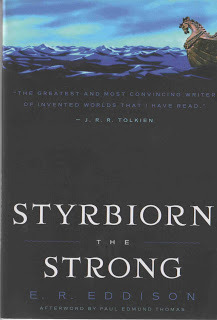

The Tolkien quote appears on the cover of a new edition of Styrbiorn the Strong, published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2011 with an afterword by Paul Edmund Thomas.

The Tolkien quote appears on the cover of a new edition of Styrbiorn the Strong, published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2011 with an afterword by Paul Edmund Thomas.“Styrbiorn’s name has sounded in my memory like a drum ever since, twenty years ago, I first read the passing reference to him in the Eyrbyggja Saga,” Eddison wrote in a letter to his younger brother in 1922. According to Thomas, Eddison bought the William Morris and Eirikr Magnusson translation of the saga in 1900.

Writing to his typist just after The Worm Ouroboros came out, Eddison said, “I am starting on a new book: a historical story this time about people who really lived in this world, in the Viking age in Sweden a thousand years ago, the age of the great classic saga literature of the north, which I have studied these twenty years and which I love more than any other.”

What about the sagas inspired him? In the “Closing Note” to Styrbiorn the Strong, Eddison explained: “The spirit of the North, to the inheritance of which I believe (pace Mr. Hilaire Belloc) our own country largely owes her greatness, is embodied in its purest form in its prose epic, the Icelandic Sagas of the classical age, such as (to name a few) Njal’s Saga, the Laxdale Saga, the Saga of Egil Skallagrimsson, Gisli’s Saga, and the Saga of Hrafnkel the Priest of Frey.”

He continued: “There is no ‘Keltic Twilight’ here, no barbaric exaggerations, no embroidery, no weaving of words or fancies, no boggling at truth: there is much shrewd insight into character and the springs of action, a power of direct and vivid narrative rarely matched in any other literature, much deep-seated humour and philosophy of hard and manly life.”

And finally: “But this is not the place to do more than hint at some obvious qualities of that genius which has shed about the lives of a few great families, dwelling in lonely homesteads in distant Iceland, an atmosphere of tragic and epic grandeur like the grandeur that is about windy Ilios; bringing us, in the end, as Homer brings us, not to take sides with Greeks or Trojans, with Njal’s sons or the Burners, but to ponder (somewhat perhaps as the Gods may ponder) on the greatness and the pitifulness of human things.”

It’s interesting to read Styrbiorn the Strong and see how close Eddison came to his models. And then, of course, to reread a saga. Perhaps Eyrbyggja Saga.

For as Eddison said in his letter to his brother, “There is no saga of the Swedish prince after whom this story is named. If there were, I do not think my story would have been written. For it is not my study to emulate a writer for whose other work I have a respect, in treating the sagas as Tate & Cibber treated Shakespeare, tricking out these imperishable prose epics of the north with modern fripperies of sentimental love interest and psychological disquisition. … I am so simple as to believe that those grand stories are so elemental, so beautiful, so firm set in the soil of life, that they are quite able to look after themselves.”

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on February 20, 2013 09:14

February 13, 2013

Snorri the Hobbit?

A year after completing my biography of Snorri Sturluson,

Song of the Vikings

, I am rethinking his character. Snorri, I now see, was a hobbit.

A year after completing my biography of Snorri Sturluson,

Song of the Vikings

, I am rethinking his character. Snorri, I now see, was a hobbit.Writing about Tolkien’s debt to Snorri at the end of my book, I discussed the Icelandic antecedants of the wizard Gandalf, the dwarves, elves and orcs, the dragon, the shapeshifter Beorn, warrior women, the riders of Rohan, the giant eagles, the trolls, the wargs, barrow-wights, magic swords, Mount Doom, and the cursed ring of power.

I may not have gone far enough.

I should have included hobbits on my list, argues Gloriana St. Clair in a paper I recently rediscovered: “Tolkien’s Cauldron: Northern Literature and The Lord of the Rings,” published online by University Libraries Research in 2000 (See http://repository.cmu.edu/lib_science/67). (The rediscovery was thanks to the marvelous website http://www.medievalists.net.)

In her chapter four, “Creatures,” St. Clair counts “over 35 types of mortals, immortals, and monsters” in Tolkien’s Middle-earth. “Those that show some affinity with the Northern myths and folk traditions are 1) Hobbits, 2) Elves and Orcs, 3) Dwarves, 4) Wizards, 5) Tree-kin, 6) Birds, 7) Dragons, 8) Wargs, 9) The Eye, and 10) Ancients.”

None of the others surprised me, but hobbits? I think of them more as the quintessential English country folk. St. Clair has anticipated my objections.

She writes: “Perhaps one of the most unlikely comparisons possible is between the short, fat, meek hobbits and the tall, strong, daring Vikings”—a term she applies to characters from the Icelandic sagas. “Yet the two peoples do share some traits.”

Her list of traits is convincing—and strangely matches my description of the writer of the Edda, Heimskringla, and (most likely) Egil’s Saga, Tolkien’s muse Snorri Sturluson.

Her list of traits is convincing—and strangely matches my description of the writer of the Edda, Heimskringla, and (most likely) Egil’s Saga, Tolkien’s muse Snorri Sturluson.“One of the first things that Tolkien mentions about the hobbits is their fondness for visitors,” writes St. Clair. Snorri also loved visitors—he practically kept open house at his grand estate of Reykholt for poets and writers.

Among hobbits, says St. Clair, “Storytelling was held in particular demand. … Bilbo recollects stories told about Gandalf. … Sam refers sentimentally to the great stories without ends … [and] mentions Frodo’s probable fame in the storytelling of the Shire.” Storytelling was one of Snorri’s great loves too. He collected stories, he memorized stories, he made up stories, and, fortunately for us, he filled page after page of parchment with stories. Otherwise, as I have argued here earlier, we would know little or nothing about Norse mythology.

Hobbits liked to eat six meals a day, if they could get them, and they loved parties. So did Snorri. According to his nephew, who wrote part of Sturlunga Saga, Snorri gave elaborate feasts and was a cheerful host. Snorri himself writes often and at length about eating and drinking: In Heimskringla it seems that a nobleman’s major duty was to organize feasts.

“Hobbits and Vikings were vain about their dress,” says St. Clair. As was Snorri. In his history of the kings of Norway, Heimskringla, Snorri allows King Sigurd the Jerusalem-farer to declare that “a king must be tall, so as to be conspicuous in a crowd.” Scholars believe Snorri was writing about himself when he has King Eystein answer his brother, “It is no less important that a man is well-dressed, so as to be easily known on that account.”

Hobbits and Icelanders “both loved to reckon their ancestors,” St. Clair points out. Snorri’s interest in genealogy is clear in everything he wrote.

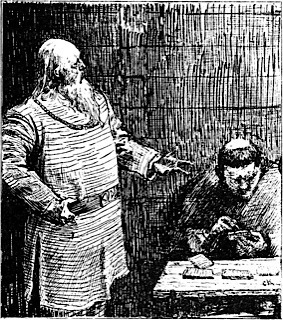

Concludes St. Clair, “Even the fear Bilbo shows when he begins to sense the nature of his unrequested journey is not unknown in the sagas. The coward who must be converted to bravery is almost a conventional character.” In the only portrayal we have of Snorri himself, the one written by his nephew, the saga-writer comes off as a very Bilbo-esque coward. Unfortunately, he never “converted to bravery,” though he wrote eloquently about it. He did not live up to his Viking ideals, to the heroes portrayed in his books. He did not die with a laugh—or a poem—on his lips. His last words were “Don’t strike!” As the poet Jorge Luis Borges sums him up in a beautiful poem, the writer who “bequeathed a mythology / Of ice and fire” and “violent glory” to us was a coward: “On / Your head, your sickly face, falls the sword, / As it fell so often in your book.”

Concludes St. Clair, “Even the fear Bilbo shows when he begins to sense the nature of his unrequested journey is not unknown in the sagas. The coward who must be converted to bravery is almost a conventional character.” In the only portrayal we have of Snorri himself, the one written by his nephew, the saga-writer comes off as a very Bilbo-esque coward. Unfortunately, he never “converted to bravery,” though he wrote eloquently about it. He did not live up to his Viking ideals, to the heroes portrayed in his books. He did not die with a laugh—or a poem—on his lips. His last words were “Don’t strike!” As the poet Jorge Luis Borges sums him up in a beautiful poem, the writer who “bequeathed a mythology / Of ice and fire” and “violent glory” to us was a coward: “On / Your head, your sickly face, falls the sword, / As it fell so often in your book.” As I describe him in Song of the Vikings, Snorri was “one of the richest men in Iceland, holder of seven chieftaincies, owner of five profitable estates and a harbor, husband of an heiress, lover of several mistresses, a fat man soon to go gouty, a hard drinker, a seeker of ease prone to soaking long hours in his hot-tub while sipping stout ale, not a Viking warrior by any stretch of the imagination, but clever. Crafty, cunning, and ambitious. A good businessman. So well-versed in the law that few other Icelanders could out-argue him. A respectable poet and a lover of books.”

Think of Bilbo Baggins with a sex life, a lot of lawyerly cunning, and a lack of moral fiber. Perhaps a Sackville-Baggins?

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on February 13, 2013 06:57

February 6, 2013

Making Middle Earth

When I wrote earlier about the Norse creation story, as told by Snorri Sturluson in his Edda, I described how the god Odin and his brothers fashioned the world out of the body of the frost giant Ymir:

When I wrote earlier about the Norse creation story, as told by Snorri Sturluson in his Edda, I described how the god Odin and his brothers fashioned the world out of the body of the frost giant Ymir:His flesh was the soil, his blood the sea. His bones and teeth became stones and scree. His hair were trees, his skull was the sky, his brain, clouds. From his eyebrows they made Middle Earth, which they peopled with men, crafting the first man and woman from driftwood they found on the seashore.

From his eyebrows? Notice how quickly I skipped over that. Middle Earth is clearly the place where men and women live. Elsewhere Snorri says the earth (or the world, depending on the translator) is round. Now whether you think of it as “round” as a disc (as some scholars still do, in spite of the overwhelming evidence that medieval people knew the world was a sphere [link to Flat Earth blog]) or “round” as an apple (as the Norse did in Snorri’s day, according to the 13th-century encyclopedia called The King’s Mirror), it’s still hard to imagine the world we live in as being made from eyebrows.

So what is Snorri’s “Middle Earth”?

Kevin Wanner of the University of Western Michigan has a brilliant answer. Wanner was one of the scholars who most influenced my understanding of Snorri Sturluson as a writer. Somehow I missed his 2009 article, “Off-Center: Considering Directional Valances in Norse Cosmography,” when I was working on my biography of Snorri, Song of the Vikings.

Admittedly, the part that’s snagged my interest now is not Wanner’s main argument. It’s the definition of the Old Norse word Miðgarðr, which I’ve always seen translated into the Tolkienish Middle Earth.

As Wanner notes, forms of this word appear in many northern languages. In Old English, for example, middangeard is clearly the Latin mundus, the world as a whole. But Old Norse writers (Snorri included) usually use the word heimr to refer to the world as a whole. So what really is Miðgarðr?

As Wanner notes, forms of this word appear in many northern languages. In Old English, for example, middangeard is clearly the Latin mundus, the world as a whole. But Old Norse writers (Snorri included) usually use the word heimr to refer to the world as a whole. So what really is Miðgarðr?The first part, mið, isn’t contested. It means “middle.”

But garðr, Wanner points out, has two meanings. One is the cognate “yard,” in the sense of an enclosure. The second is “fence” or “fortification.”

Writes Wanner, “As incredible as it may seem in light of the typical understanding and use of the term among scholars, there is not one occurrence of ‘Miðgarðr’ in Snorri’s Edda or eddic poetry in which the second element of the name unambiguously carries the sense of yard or enclosure.” There are many cases, on the other hand, of garðr meaning a fortification.

Instead of “Middle Earth,” Wanner concludes, Miðgarðr might just mean “fence down the middle.”

Go back to those giant eyebrows—which Wanner explains could instead be eyelashes. In either case, think of two arcs of hair. Bushy eyebrows. Spiky eyelashes. A fence of giant hair.

It makes perfect sense if you add another part that I skipped over when retelling Snorri’s creation story: the reason why Odin and his brothers made Miðgarðr. The gods had already given lands on the shore of the sea to the giants, Snorri writes. Then, because of the “hostility of the giants,” they made Miðgarðr—the fence down the middle—to protect the people they were about to fashion from driftwood.

Now whether this fence was an arc, a circle, or a wiggly line I’ll leave it to Wanner to convince you. His paper was published in Speculum (2009): 36-72.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on February 06, 2013 10:59

January 30, 2013

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri: Part VII

The last myth in this series is the Death of Baldur. It is Snorri’s “greatest achievement as a storyteller,” according to some scholars. They compare it to Shakespeare’s plays, with its balance of comic and tragic. Of course, others fault it for the same thing. A 19th-century scholar slammed it as a “burlesque.” One in the early 20th century chastized Snorri for his “irresponsible treatment” of tradition. Snorri, he sniffed, made myths into “novellas.”

The last myth in this series is the Death of Baldur. It is Snorri’s “greatest achievement as a storyteller,” according to some scholars. They compare it to Shakespeare’s plays, with its balance of comic and tragic. Of course, others fault it for the same thing. A 19th-century scholar slammed it as a “burlesque.” One in the early 20th century chastized Snorri for his “irresponsible treatment” of tradition. Snorri, he sniffed, made myths into “novellas.”That’s why we remember them, it seems to me.

There’s a version of Baldur’s death in Saxo Grammaticus’s Latin History of the Danes, but since Jacob Grimm (of the famous fairy tale brothers) wrote his German Mythology in 1835, no one has consider it the “real” myth. In his book Grimm cites Snorri’s Edda, but he gives Snorri no credit as an author. He quotes him. He allows that Snorri makes “conjectures.” But when comparing Snorri’s Edda to Saxo’s History of the Danes, Grimm finds the Icelandic text “a purer authority for the Norse religion”—no matter that Snorri and Saxo were writing at roughly the same time. “As for demanding proofs of the genuineness of Norse mythology, we have really got past that now,” Grimm asserts. He finds the myth of Baldur “one of the most ingenious and beautiful in the Edda,” noting it has been “handed down in a later form with variations: and there is no better example of fluctuations in a god-myth.” By the “later form” he means Saxo’s, written between 1185 and 1223. The pure version is Snorri’s, written between 1220 and 1241. Grimm does not find his conclusion illogical; he sees no teller behind Snorri’s tale.

The god Baldur, Odin’s second son, is fair and white as a daisy, Snorri writes, “and so bright that light shines from him.” His palace is called Breidablik, “Broad Gleaming”: “This is in heaven,” Snorri says. Baldur is like the sun in the sky. He is the wisest of the gods, the most eloquent, and the most merciful—but “none of his decisions can be fulfilled,” Snorri writes. He’s beautiful, but totally useless.

In Norse mythology as we know it, Baldur the Beautiful does nothing but die.

Here’s the story as I tell it in my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths:

One night, Baldur began to have bad dreams. Hearing of this, his mother Frigg exacted a promise from everything on earth not to hurt him. Fire and water, iron and stone, soil, trees, animals, birds, snakes, illnesses, and even poisons agreed to leave Baldur alone.

After that, the gods entertained themselves with Baldur-target practice. They shot arrows at him, hit him with spears, pelted him with stones. Nothing hurt him. The gods thought this was glorious, Snorri writes. Except Loki the Trickster. He was jealous. He put on a disguise and wormed up to Frigg. “Have all things sworn oaths not to harm Baldur?”

“There grows a shoot of a tree to the west of Valhalla,” Frigg replied. “It is called mistletoe. It seemed young to me to demand the oath from.”

Loki made a dart of mistletoe and sought out the blind god Hod. “Why are you not shooting at Baldur?”

“Because I cannot see where Baldur is,” Hod replied testily.

“I will direct you,” Loki offered. He gave Hod the dart. Hod tossed it, and Baldur died. Says Snorri, “This was the unluckiest deed ever done among gods and men.”

Reading this story you probably wondered how a dart made of mistletoe could kill anyone.

Reading this story you probably wondered how a dart made of mistletoe could kill anyone. It couldn’t.

Snorri had no idea what mistletoe was. It doesn’t grow in Iceland, and is rare in Norway. It is not a tree, but a parasitic vine found in the tops of oaks. The “golden bough” of folklore, it was gathered in some cultures at the summer solstice; picking it caused the days to shorten. Originally, it seems, the death of Baldur was a drama of the agricultural year.

Snorri did not see it that way. In his mythology, time is not cyclical. Baldur does not die off and come back each year like summer. Instead, Baldur’s death causes Ragnarok, in which the old gods are killed and the old earth destroyed in a fiery cataclysm.

Baldur’s death at his brother Hod’s hand is mentioned in the “Song of the Sibyl,” an older poem that Snorri knew and often quotes, though he doesn’t say who wrote it, as he does for most of the poems he quotes in the Edda. In the “Song of the Sibyl,” mistletoe is also Baldur’s bane. Snorri didn’t make that part up. But the plant’s attraction for him (and the “Sibyl” poet) was not any special mythic meaning. What Snorri liked was its name: mistilsteinn. Other Icelandic words ending in “-teinn” referred to swords. And Mist? It’s the name of a valkyrie. A plant named “valkyrie’s sword” must be deadly.

The “Song of the Sibyl” doesn’t say Frigg forced an oath out of everything else on earth to keep Baldur safe. The poem doesn’t say Loki wheedled the secret from her or guided blind Hod’s hand—it doesn’t mention Loki in this context at all.

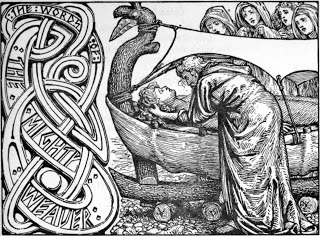

No one but Snorri says what happened next: Weeping, Frigg begged someone to ride to Hel and offer the goddess of death a ransom to give Baldur back. Hermod—a god in no other story—volunteered. He took Odin’s horse, eight-legged Sleipnir, and set off.

Meanwhile, the gods held Baldur’s funeral. It’s strangely comic—with many details exclusive to Snorri. They carried his body in procession to the sea, Freyr in his chariot drawn by the golden boar; Freyja in hers, drawn by giant cats.

They built Baldur’s pyre on his warship, but when they tried to launch it, they could not: Their grief had sapped their strength, and they had to send to Giantland for help. “A great company of frost-giants and mountain-giants” arrived, including a giantess “riding a wolf and using vipers as reins.” Odin called four of his berserks to see to her mount, but “they were unable to hold it without knocking it down,” Snorri says. The giantess launched the ship “with the first touch, so that flame flew from the rollers and all lands quaked,” performing with a fingertip what all the gods were powerless to accomplish.

They built Baldur’s pyre on his warship, but when they tried to launch it, they could not: Their grief had sapped their strength, and they had to send to Giantland for help. “A great company of frost-giants and mountain-giants” arrived, including a giantess “riding a wolf and using vipers as reins.” Odin called four of his berserks to see to her mount, but “they were unable to hold it without knocking it down,” Snorri says. The giantess launched the ship “with the first touch, so that flame flew from the rollers and all lands quaked,” performing with a fingertip what all the gods were powerless to accomplish. That made Thor angry. He never liked a giant to one-up him. “He grasped his hammer and was about to smash her head until all the gods begged for grace for her.”

Nanna, Baldur’s loving wife, then collapsed and died of grief; she was placed on the funeral pyre on the ship beside her husband. (No other source mentions Nanna’s death.) The gods led Baldur’s horse to the pyre and slaughtered it. Odin placed his magic ring, Draupnir, on Baldur’s breast.

Then Thor consecrated the pyre with his hammer and it was set alight. Returning to his place, he stumbled on a dwarf: “Thor kicked at him with his foot,” Snorri writes, “and thrust him into the fire and he was burned.”

The scene shifts back to Hermod’s Hel-ride. Snorri was inspired here by the apocryphal story of Christ’s Harrowing of Hell, as told in the Gospel of Nicodemus, which was popular in 13th-century Iceland. Christ, in the Icelandic translation, rode a great white horse into Hell. Hermod rode the eight-legged Sleipnir, also white. He rode for nine nights, through valleys dark and deep, until he reached the river dividing the world from the underworld. He rode onto a bridge covered with glowing gold. The maiden guarding the bridge stopped him. Five battalions of dead warriors had just crossed, she said, but Hermod made more noise. “Why are you riding here on the road to Hel?” she asked. (For Snorri, Hel is both a person and the place she inhabits.)

He was chasing Baldur, Hermod replied. “Have you seen him?”

“Yes, he crossed the bridge. Downwards and northwards lies the road to Hel.”

Hermod rode on until he reached Hel’s gates. “Then he dismounted from the horse and tightened its girth”—a nice detail showing Snorri really did know horses—“mounted and spurred it on.” Sleipnir leaped the gate. Hermod rode up to Hel’s great hall, where he found Baldur sitting in the seat of honor. Hermod stayed the night.

Hermod rode on until he reached Hel’s gates. “Then he dismounted from the horse and tightened its girth”—a nice detail showing Snorri really did know horses—“mounted and spurred it on.” Sleipnir leaped the gate. Hermod rode up to Hel’s great hall, where he found Baldur sitting in the seat of honor. Hermod stayed the night. In the morning, he described the great weeping in Asgard and asked Hel if Baldur could ride home with him. (Baldur’s horse, burned on the pyre, was safe in Hel’s stables.)

Hel is not a monster, in Snorri’s tale, but a queen. She gave it some thought. Was Baldur really so beloved? she wondered. She would put it to the test. “If all things in the world, alive or dead, weep for him,” she decreed, “then he shall go back.” If anything refuses to weep, he stays in Hel.

The gods “sent all over the world messengers to request that Baldur be wept out of Hel. And all did this, the people and animals and the earth and the stones and trees and every metal, just as you will have seen that these things weep when they come out of frost and into heat,” Snorri writes. (He liked to include these little just-so stories.)

Everything wept, that is, except a certain ugly giantess. “It is presumed,” Snorri added, “that this was Loki” in disguise.

No other source makes Loki the Trickster so clearly responsible for taking Baldur the Beautiful from the world. With Baldur’s death, chaos is unleashed. The gods have lost their luck, the end of the world is nigh: Ragnarok, when Loki and his horrible children, the wolf Fenrir and the Midgard Serpent, will join forces with the giants to destroy the gods.

This is the last of the seven Norse myths we wouldn’t have without Snorri. Now that you know how much of Norse mythology he made up, I hope you agree with me that Snorri Sturluson is not only an amazingly creative writer, but the most influential writer of the Middle Ages.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com.

You can read the complete series here: http://www.tor.com/Nancy%20Marie%20Brown#filter

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on January 30, 2013 10:23

January 23, 2013

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri: Part VI

As I’ve stressed in this series, Snorri Sturluson’s Edda is our main source for what we know of as Norse mythology. And it was written to impress a 14-year-old king. That explains why Norse mythology is so full of adolescent humor—especially when it comes to sex.

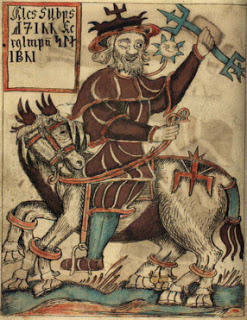

As I’ve stressed in this series, Snorri Sturluson’s Edda is our main source for what we know of as Norse mythology. And it was written to impress a 14-year-old king. That explains why Norse mythology is so full of adolescent humor—especially when it comes to sex.The Norse gods certainly had odd love lives. According to Snorri, Odin traded a lonely giantess three nights of blissful sex for three drafts of the mead of poetry. Another lucky giantess bore him valiant Vidar, one of the few gods who survived Ragnarok, the terrible last battle between gods and giants. Odin coupled with his daughter Earth to beget the mighty Thor, the Thunder God. Of course, Odin was married all this time. His long-suffering wife, wise Frigg, was the mother of Baldur the Beautiful, at whose death the whole world wept (we’ll get to that story next week).

Njord, god of the sea, married the giantess Skadi as part of a peace treaty. She wanted to marry beautiful Baldur and was told she could have him—if she could pick him out from a line-up looking only at his feet. Njord, it turned out, had prettier feet. But he and Skadi didn’t get along. He hated the mountains, she hated the sea: He hated the nighttime howling of the wolves, she hated the early morning ruckus of the gulls. So they divorced. Afterwards, Skadi was honored as the goddess of skiing. She and Odin took up together and had several sons, including Skjold, the founder of the Danish dynasty (known to the writer of Beowulf as Scyld Shefing). Njord married his sister and had two children, the twin love gods Freyr and Freyja.

Then there’s Loki, Odin’s two-faced blood-brother, whose love affairs led to so much trouble. Loki, of course, was the reason why the giantess Skadi was owed a husband in the first place: His mischief had caused Skadi’s father to be killed. In addition to getting a husband, Skadi had another price for peace. The gods had to make her laugh. She considered this impossible. “Then Loki did as follows,” Snorri writes. “He tied a cord round the beard of a certain nanny-goat and the other end round his testicles, and they drew each other back and forth and both squealed loudly. Then Loki let himself drop in Skadi’s lap, and she laughed.”

Loki, writes Snorri, was “pleasing and handsome in appearance, evil in character, very capricious in behavior. He possessed to a greater degree than others the kind of learning that is called cunning…. He was always getting the Aesir into a complete fix and often got them out of it by trickery.”

With his loyal wife, Loki had a godly son. In the shape of a mare, he was the mother of Odin’s wonderful eight-legged horse Sleipnir, which I wrote about in part two of this series.

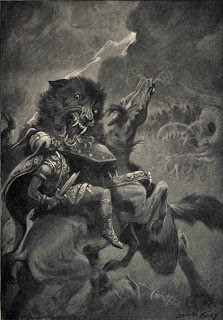

With his loyal wife, Loki had a godly son. In the shape of a mare, he was the mother of Odin’s wonderful eight-legged horse Sleipnir, which I wrote about in part two of this series. But on an evil giantess Loki begot three monsters: the Midgard Serpent; Hel, the half-black goddess of death; and the giant wolf, Fenrir.

Odin sent for Loki’s monstrous children. He threw the serpent into the sea, where it grew so huge it wrapped itself around the whole world. It lurked in the deeps, biting its own tail, until taking revenge at Ragnarok and slaying Thor with a blast of its poisonous breath.

Odin sent Hel to Niflheim, where she became the harsh and heartless queen over all who died of sickness or old age. In her hall, “damp with sleet,” they ate off plates of hunger and slept in sickbeds.

The giant wolf, Fenrir, the gods raised as a pet until it grew frighteningly large. Then they got from the dwarves a leash bound from the sound of a cat’s footstep, a woman’s beard, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird.

Fenrir would not let them tie him up until Tyr, the brave god of war for whom Tuesday was named, put his hand in the wolf’s mouth as a pledge of the gods’ good faith. The wolf could not break free of this leash no matter how hard he struggled, and the gods refused to let him loose. It had been a trick all along.

“Then they all laughed except for Tyr,” Snorri writes. “He lost his hand.”

It’s a classic Snorri line. Like the story of Skadi picking her bridegroom by his beautiful feet, and how Loki made her laugh, the story of the binding of Fenrir—and how Tyr lost his hand—is known only to Snorri. As I’ve said before, no one in Iceland or Norway had worshipped the old gods for 200 years when Snorri was writing his Edda.People still knew some of the old stories, in various versions. And there were hints in the kennings, the circumlocutions for which skaldic poetry was reknowned. Snorri memorized many poems and collected many tales. From these he took what he liked and retold the myths, making things up when need be. Then he added his master touch, what one scholar has labeled a “peculiar grim humor.” The modern writer Michael Chabon describes it as a “bright thread of silliness, of mockery and self-mockery” running through the tales. And it is Snorri’s comic versions that have come down to us as Norse mythology.

It’s a classic Snorri line. Like the story of Skadi picking her bridegroom by his beautiful feet, and how Loki made her laugh, the story of the binding of Fenrir—and how Tyr lost his hand—is known only to Snorri. As I’ve said before, no one in Iceland or Norway had worshipped the old gods for 200 years when Snorri was writing his Edda.People still knew some of the old stories, in various versions. And there were hints in the kennings, the circumlocutions for which skaldic poetry was reknowned. Snorri memorized many poems and collected many tales. From these he took what he liked and retold the myths, making things up when need be. Then he added his master touch, what one scholar has labeled a “peculiar grim humor.” The modern writer Michael Chabon describes it as a “bright thread of silliness, of mockery and self-mockery” running through the tales. And it is Snorri’s comic versions that have come down to us as Norse mythology.Next week, in the last post in this series, I’ll examine Snorri’s masterpiece as a creative writer, the story of the death of Baldur.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on January 23, 2013 07:22

January 16, 2013

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri: Part V

Norse myths have been very popular with fantasy and science fiction writers. Why? I think it’s because of Snorri’s special touch—the wry and sarcastic humor that infuse his tales.

Norse myths have been very popular with fantasy and science fiction writers. Why? I think it’s because of Snorri’s special touch—the wry and sarcastic humor that infuse his tales.In 2005, for example, Shadow Writer interviewed Neil Gaiman while he was touring for The Anansi Boys (read it here: http://www.shadow-writer.co.uk/neilinterview.htm). They asked Gaiman if he had a favorite myth. He answered, “I keep going back to the Norse ones because most myths are about people who are in some way cooler and more magical and more wonderful than us, and while the Norse gods probably sort of qualify, they’re all sort of small-minded evil, conniving bastards, except for Thor and he’s thick as two planks.”

Then Gaiman referred a tale Snorri wrote: “I still remember the sheer thrill of reading about Thor,” Gaiman said, “and going into this weird cave that they couldn’t make sense of with five branches—a short one and four longer ones—and coming out in the morning from this place on their way to fight the giants … and realizing they’d actually spent the night in this giant’s glove, and going, Okay, we’re off to fight these guys. Right.”

It’s the beginning of the story of the god Thor’s encounter with the giant Utgard-Loki. No other source tells this tale. I think Snorri made it up. I imagine him regaling his friends with it, as they sat around his feast hall at his grand estate of Reyholt in Iceland, sipping horns of mead or ale. Snorri was known for holding extravagant feasts, to which he invited other poets and storytellers. He might have read aloud from his work-in-progress, the Edda. Or he might have told the tale from memory, like an ancient skald.

Here’s how I relate the story in my biography of Snorri, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths:

Here’s how I relate the story in my biography of Snorri, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths:One day Thor the Thunder-god and Loki the Trickster sailed east across the sea to Giantland. With them was Thor’s servant, a human boy named Thjalfi, who carried Thor’s food bag. They trudged through a dark forest. That night they found no lodgings except one large, empty house. It had a wide front door, a vast central hall, and five side chambers. Thor and his companions made themselves comfortable in the hall. At midnight came a great earthquake. The ground shuddered. The house shook. They heard scary grumblings and groans. Loki and the boy fled into one of the little side chambers, and Thor guarded the doorway, brandishing his hammer against whatever monster was making that noise.

Nothing more happened that night. At dawn Thor saw a man lying asleep at the edge of the forest. Thor clasped on his magic belt and his strength grew. He lifted his hammer—but then the man awoke and stood up. He was so huge that “Thor for once was afraid to strike him.” Instead, he politely asked the giant’s name.

The giant gave a fake one. “I do not need to ask your name,” he said in return. “You are the mighty Thor. But what were you doing in my glove?”

(Here I imagine Snorri pausing, while laughter fills the room. Maybe he gets up and refills his ale horn.)

The giant, Snorri continues, suggested they travel together and offered to carry their food bag in his giant knapsack. After a long day keeping up with giant strides they camped for the night under an oak tree. The giant settled in for a nap. “You take the knapsack and get on with your supper.”

Thor could not untie the knot. He struggled. He fumed. And—giantlike?—he flew into a rage. He grasped his hammer in both hands and smashed the giant on the head.

The giant awoke. “Did a leaf fall on me?”

(Another pause for laughter.)

He went back to sleep.

Thor hit him a second time. “Did an acorn fall on me?” (Pause for laughter.)

He went back to sleep.

Thor took a running start, swung the hammer with all his might—

The giant sat up. “Are you awake, Thor? There must be some birds sitting in the tree. All sorts of rubbish has been falling on my head.”

(Pause for laughter.)

The giant showed Thor the road to the castle of Utgard then went on his way.

Thor and Loki and little Thjalfi walked all morning. They reached a castle so huge they “had to bend their heads back to touch their spines” to see the top. Thor tried to open the gate, but couldn’t budge it. They squeezed in through the bars. The door to the great hall stood open. They walked in.

Thor and Loki and little Thjalfi walked all morning. They reached a castle so huge they “had to bend their heads back to touch their spines” to see the top. Thor tried to open the gate, but couldn’t budge it. They squeezed in through the bars. The door to the great hall stood open. They walked in.King Utgard-Loki (no relation to the god Loki) greeted them. “Am I wrong in thinking that this little fellow is Thor? You must be bigger than you look.”

It was the rule of the giant’s castle that no one could stay who was not better than everyone else at some art or skill. Hearing this, Loki piped up. He could eat faster than anyone.

The king called for a man named Logi. A trencher of meat was set before the two of them. Each started at one end and ate so fast they met in the middle. Loki had eaten all the meat off the bones, but his opponent, Logi, had eaten meat, bones, and wooden trencher too. Loki lost.

The boy Thjalfi was next. He could run faster than anyone. The king had a course laid out and called up a boy named Hugi. Thjalfi lost.

Thor could drink more than anyone, he claimed. The king got out his drinking horn. It was not terribly big, though it was rather long. Thor took great gulps, guzzling until he ran out of breath, but the level of liquid hardly changed. He tried twice more. The third time, he saw a little difference.

He called for more contests.

“Well,” said the king, “you could try to pick up my cat.”

Thor seized it around the belly and heaved—but only one paw came off the ground. “Just let someone come out and fight me!” he raged, “Now I am angry!”

The king’s warriors thought it demeaning to fight such a little guy, so he called out his old nurse, Elli.

“There is not a great deal to be told about it,” Snorri writes. “The harder Thor strained in the wrestling, the firmer she stood. Then the old woman started to try some tricks, and then Thor began to lose his footing, and there was some very hard pulling, and it was not long before Thor fell on one knee.”

Utgard-Loki stopped the contest, but allowed them to stay the night anyway.

The next day the king treated Thor and his companions to a feast. When they were ready to go home, he accompanied them out of the castle and said he would now reveal the truth. He himself had been the giant they met along their way; he had prepared these illusions for them.

When Thor swung his hammer—the leaf, the acorn, the rubbish—Utgard-Loki had placed a mountain in the way: It now had three deep valleys. At the castle, they had competed against fire (the name Logi literally means “fire”), thought (Hugi), and old age (Elli). The end of the drinking horn had been sunk in the sea—Thor’s three great drafts had created the tides. The cat? That was the Midgard Serpent which circles the entire earth.

Outraged at being tricked, Thor raised his mighty hammer once more. But he blinked and Utgard-loki and his castle disappeared.

“Thick as two planks,” indeed.

Why do I think Snorri made up this story of Thor’s visit to Utgard-Loki? A poet does refer to Thor hiding in a giant’s glove—but it’s a different giant. Another mentions his struggle with the knot of a giant’s food-sack. A kenning for old age refers to Thor wrestling with Elli—but it appears in Egil’s Saga, which Snorri probably wrote, so he may be quoting himself. Otherwise, the journey and the contests are unknown.

Why do I think Snorri made up this story of Thor’s visit to Utgard-Loki? A poet does refer to Thor hiding in a giant’s glove—but it’s a different giant. Another mentions his struggle with the knot of a giant’s food-sack. A kenning for old age refers to Thor wrestling with Elli—but it appears in Egil’s Saga, which Snorri probably wrote, so he may be quoting himself. Otherwise, the journey and the contests are unknown.I think the brilliant character of the giant Utgard-Loki, with his wry attitude toward that little fellow Thor who “must be bigger than he looks,” is a stand-in for Snorri himself. They share the same humorous tolerance of the gods. There is very little sense throughout the Edda that these were gods to be feared or worshipped, especially not the childish, naïve, blustering, weak-witted, and fallible Thor who is so easily deluded by Utgard-Loki’s wizardry of words. What god in his right mind would wrestle with a crone named “Old Age”? Or expect his servant-boy to outrun “Thought”?

It also fits with why Snorri wrote the Edda: to teach the 14-year-old king of Norway about Viking poetry. This story has a moral: See how foolish you would look, Snorri is saying to young King Hakon, if you didn’t understand that words can have more than one meaning, or that names can be taken literally? The story of Utgard-loki is, at heart, a story about why poetry matters.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on January 16, 2013 05:26

January 9, 2013

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri: Part IV

Imagine you are a 40-year-old poet who wants to impress a 14-year-old king. You want to get him excited about Viking poetry—which happens to be your specialty—and land yourself the job of King’s Skald, or court poet. A cross between chief counselor and court jester, King’s Skald was a well-paid and highly honored post in medieval Norway. For over 400 years, the king of Norway had had a King’s Skald. Usually the skald was an Icelander—everyone knew Icelanders made the best poets.

Imagine you are a 40-year-old poet who wants to impress a 14-year-old king. You want to get him excited about Viking poetry—which happens to be your specialty—and land yourself the job of King’s Skald, or court poet. A cross between chief counselor and court jester, King’s Skald was a well-paid and highly honored post in medieval Norway. For over 400 years, the king of Norway had had a King’s Skald. Usually the skald was an Icelander—everyone knew Icelanders made the best poets.Except, it seems, 14-year-old King Hakon. He thought Viking poetry was old-fashioned and too hard to understand.

To change young Hakon’s mind, Snorri Sturluson began writing his Edda, the book that is our main, and sometimes our only, source for much of what we think of as Norse mythology.

Snorri started off, in about 1220, by writing an elaborate poem in praise of King Hakon and his regent, Earl Skuli. It was 102 stanzas long, in 100 different styles. No poet had ever written such a complicated skaldic poem. With it, Snorri was handing the young king his resume: There was no better candidate for King’s Skald.

It’s a really dull poem.

If you’re not in love with skaldic poems—if you don’t like riddles and trivia quizzes—it’s no fun to read.

Snorri realized this. He did not send his poem to the young king. Instead, he began a new section of the Edda, explaining how skaldic poems worked.

Snorri realized this. He did not send his poem to the young king. Instead, he began a new section of the Edda, explaining how skaldic poems worked.One thing he had to explain were “kennings,” the riddles Viking poets loved. No poet writing in Old Norse before about 1300 would say “mead” when he or she could say “waves of honey,” or “ship” instead of “otter of the ocean,” or “sword” instead of “fire of the spear clash.”

And those are easy kennings to figure out. The harder ones refer to Norse myths.

For example, what did a Viking poet mean by saying “Aegir’s fire,” or “Freya’s tears,” or “Sif’s hair”?

The Norse gods Aegir and Freya and Sif hadn’t been worshipped for over 200 years in Norway or Iceland. Few people remembered the old stories of gods and dwarfs and giants, and so the old poems hardly made sense. For this reason, Snorri included in his Edda many stories about the gods: stories he had heard, stories he pieced together from old poems—and stories he simply made up.

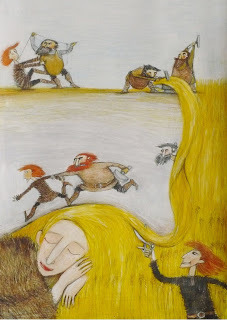

Many of his stories feature Loki the Trickster. One of the most important for our understanding of the Norse gods is the time that Loki, out of mischief, cut off the goddess Sif’s long, golden hair.

Her husband, the mighty Thor, was not amused. “He caught Loki and was going to break every one of his bones until he swore that he would get black-elves to make Sif a head of hair out of gold that would grow like any other hair.”

Her husband, the mighty Thor, was not amused. “He caught Loki and was going to break every one of his bones until he swore that he would get black-elves to make Sif a head of hair out of gold that would grow like any other hair.” Loki went to the land of the dwarfs. (Here, Snorri says dwarfs and black-elves are the same. Elsewhere he says they are different. It’s a problem in the Edda that bothered Tolkien greatly.)

Shortly, Loki and one of the dwarf smiths returned to Asgard with Sif’s new head of hair. They also brought five other treasures. Turns out, the dwarfs were happy to make Sif’s hair. They liked to show off their skills.

They made Freyr’s magic ship Skidbladnir, “which had a fair wind as soon as its sail was hoisted” and “could be folded up like a cloth and put in one’s pocket.”

And they made Odin’s spear, Gungnir, which “never stopped in its thrust.”

But greedy Loki wanted more treasures. So he wagered his head that the two dwarf smiths, Brokk and Eitri, could not make three more treasures as good as these three were.

The dwarfs took the bet.

Eitri put a pig skin in his forge. He told Brokk to work the bellows without stop. A fly landed on Brokk’s arm and bit him—but he ignored it. After a long while, Eitri took out of the forge a boar with bristles of gold. It could run across sea and sky faster than a horse, and its bristles blazed with light like the sun. This magic boar, Gullinbursti, became the god Freyr’s steed.

Next Eitri put a bar of gold in his forge. Again he told Brokk to work the bellows without stop. That pesky fly came back and bit Brokk on the neck—but Brokk ignored it. Out of the magic forge came Odin’s gold ring, Draupnir. Every ninth night it dripped eight rings just like itself.

Then Eitri put iron in the forge. He told Brokk to work the bellows, “and said it would turn out no good if there were any pause in the blowing.” The fly—which, of course, was Loki in fly form—landed this time on Brokk’s eyelid. It bit so hard the blood trickled into the dwarf’s eyes. Brokk swept a hand across his face— “You’ve almost ruined it!” his brother yelled. This treasure was Thor’s hammer, Mjollnir. It would strike any target and never miss. If thrown, it would return to Thor’s hand like a boomerang. It was so small, Thor could hide it in a pocket. But it had one fault: The handle was a little too short.

When Brokk brought all six dwarf-made treasures to Asgard, the gods agreed Loki had lost the bet. The boar, the gold ring, and the hammer were every bit as good as Sif’s hair, Freyr’s ship, and Odin’s spear.

When Brokk brought all six dwarf-made treasures to Asgard, the gods agreed Loki had lost the bet. The boar, the gold ring, and the hammer were every bit as good as Sif’s hair, Freyr’s ship, and Odin’s spear.Thor grabbed hold of Loki and held him still so the dwarf could cut off his head. But Loki was a bit of a lawyer. Presaging Shakespeare’s Shylock by several hundred years, he told Brokk “that the head was his but not the neck.”

Loki didn’t get away scatheless. Since “the head was his,” Brokk decided to make an improvement to it: He stitched Loki’s lips together.

And if that story didn’t hold 14-year-old King Hakon’s attention, Snorri could make up others just as good. No other source tells of the dwarf smiths Brokk and Eitri or how the gods’ treasures came to be. Nor did there need to be a story about why gold is called “Sif’s hair.” Sif was blonde, after all.

In my next post in this series, I’ll look at one of Snorri’s funniest creations, the tale of Thor and Loki’s visit to the giant Utgard-Loki.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com.

The illustration of Sif’s hair is by the Czech artist Hellanim, who has a wonderful series of drawings on Norse myths at http://hellanim.deviantart.com/gallery/

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on January 09, 2013 06:51

January 2, 2013

Saga-Steads of Iceland

If you’re in New York on Saturday, January 5, go to Scandinavia House at 2:30 in the afternoon to hear Emily Lethbridge speak about “The Saga-Steads of Iceland: A 21st-CenturyPilgrimage.” You’ll be inspired—or jealous. I was.

If you’re in New York on Saturday, January 5, go to Scandinavia House at 2:30 in the afternoon to hear Emily Lethbridge speak about “The Saga-Steads of Iceland: A 21st-CenturyPilgrimage.” You’ll be inspired—or jealous. I was.Let me explain.

One of the loveliest moments on my book tour for Song of the Vikingswas when three University of Massachusetts at Amherst students waylaid me after my guest lecture in their Norse mythology class. They were the classic teenage trio: a burly young man who had not yet grown into himself; a mouse-shy young woman with long hair, who shrank behind him; and a second young woman, sharp-spoken and quick to act. The ringleader grabbed my arm. “She,” she pointed at her shy friend, transfixing her with a glare, “wants to be you.”

The mouse-girl could have been me in college, and I told her so. “Be stubborn,” I said. “Be persistent. Don’t let them talk you out of it.” If you want to organize your life around the Icelandic sagas, do it. Don’t let anyone tell you studying medieval Iceland is not relevant to a life in modern America. (If they try, point them toward Song of the Vikings, in which I argue that medieval Iceland inspired modern epic fantasy.)

I wish someone had given me such advice at 18. If so, I might not be so jealous of Emily Lethbridge and her Saga-Steads project. In 2010, Emily was a 33-year-old Ph.D. student at Cambridge University in England. She raised money to retrofit a Land Rover ambulance into a camper van and toured Iceland in it for a year, visiting all the places mentioned in the major Icelandic sagas. She read (or re-read) each saga on site, met the people who now live on the farms, and blogged about it at sagasteads.blogspot.com.

I read every post, waxing greener as the months went on. I wanted to grab her arm: “I want to be you!” I emailed her to that effect. No answer.

In September 2011, I stayed five days in the guest apartment at Reykholt, with its writer’s studio up a spiral stair, researching the life of Snorri Sturluson for Song of the Vikings. The writing was not going well. In my journal, I blame it first on the architecture. Reykholt is a beautiful spot, with mountains all around. I was there on a rare string of sunny fall days—and the studio had no windows. When I can’t look out a window and project my thoughts on a mountain, I can’t write. A blank white wall just will not do.

I struggled to finish an outline for chapter five. “Not sure what this chapter is about except Ragnarok, the end of all good things,” I wrote. I wandered through the library of Snorrastofa, the institute which, with the writer’s apartment, two churches, a school, a hotel, and a row of geothermally heated greenhouses now marks Snorri Sturluson’s chief estate. I went back to my computer and, instead of writing, checked Facebook. There, I learned that Emily Lethbridge had been nearby at Gilsbakki the day before. I had driven past there. I hadn’t seen her Land Rover (though I hadn’t really looked).

I read her blog post about the saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-Tongue, happy to be distracted from Snorri. I didn’t want to write about him, I finally realized, because in chapter five I had to kill him. (Astute readers will notice that in the final draft of the book, I put off his death until chapter six.) I took a walk just before midnight to Snorri’s hot tub. I saw a little touch of northern lights, a few turquoise wisps, in the sky. Got a good whiff of sulfur from the pool. Listened to the gurgling of the 800-year-old pipes. Wondered where Emily would be going next.

Early next morning, a woman entered the library. She was bundled in a down vest and layers of sweaters over heavy insulated trousers. Her short-cropped hair stuck out at all angles, as if she had just pulled off a stocking cap. She wore fingerless gloves and spoke rapid Icelandic to the librarian helping her. I knew it must be Emily.

I was too shy, at first, to interrupt. What would I say? I want to be you. Too late for that. I waited until she sat down at one of the public computers and began working. I sidled near. “Emily?” I said. “I’m Nancy Brown.”

“Oh!” she said, with a blazing smile. “I meant to email you!”

So began the kind of conversation you can only have with a soulmate. She told me about walking up to Icelanders in gas stations and on farms to ask about the sagas. We talked about saga-tourism—how not to turn Iceland into a theme park. About A.S. Byatt’s recent retelling of the Norse myth of Ragnarok, and the influence of Snorri Sturluson on the books of Neil Gaiman.

We talked about Icelandic horses. Emily had worked on a farm in the north of Iceland (something else I’d wanted to do, but hadn’t), and rode every chance she got. I, as you know, own four Icelandic horses in the U.S. (Finally something to make Emily jealous of me!)

We talked about her plans: She would be staying in a turfhouse in the south of Iceland in December, where she planned to start writing a book based on her adventure. Actually, she planned to finish the book in that month. I smiled.

We talked about my plans: to visit Surt’s Cave, where the mutilation of Snorri’s son Oraekja took place. I’d need “a headlamp and serious shoes,” she warned me. The cave floor was just rubble. “You’ll hear the drip-drip of water inside.” Deep within the cave, an Icelandic artist has placed an exhibition of his statues: faces carved of rock.

The next morning I headed for Surt’s Cave. She was right about the rubble. I had only a flashlight and rubber Wellington boots, so didn’t make it far into the cave. I never saw the statues. Still, I managed to freak myself out entirely by turning off my light and listening to the drip-drip in the unimaginable dark. I wished Emily were with me. She is much braver than I am. Or maybe I just needed her shoes.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on January 02, 2013 05:41