Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 18

October 17, 2012

How to Make a Medieval Book: Part III

On the tenth Thor’s Day of summer in the year 1000, Iceland became Christian by parliamentary decree at the Althing. Lovers of JRR Tolkien’s or Neil Gaiman’s books—or of any fantasy novel, movie, or game—should celebrate that date, because the fantasy genre would hardly exist if the medieval chieftain Snorri Sturluson had not learned to write.

On the tenth Thor’s Day of summer in the year 1000, Iceland became Christian by parliamentary decree at the Althing. Lovers of JRR Tolkien’s or Neil Gaiman’s books—or of any fantasy novel, movie, or game—should celebrate that date, because the fantasy genre would hardly exist if the medieval chieftain Snorri Sturluson had not learned to write.Writing and religion go hand-in-hand for Christians are “people of the book”: Christianity’s most powerful symbol is not the cross, but the Bible. Foreign priests, finding no books in Iceland, introduced the necessary ink-quill-and-parchment technology in about 1030—thus allowing Snorri Sturluson, some 200 years later, to write the books of Norse mythology, history, and lore that inspired Tolkien and much of modern fantasy, including Gaiman’s brilliant American Gods.

A missionary bishop named Rudolf, from Normandy or perhaps England, ran a school in the west of Iceland until 1050. He and his fellows showed their Icelandic students how to make parchment.

First they scraped the hair off a calfskin with a sharp blade. This was a harder task in Iceland, where limestone was unavailable, than in continental Europe; a bath in slaked lime made the hair simply fall off the skin. (See my previous post, “How to Make a Medieval Book: Part I.”) In Iceland, the skins were washed in a hotspring, where the mineral-rich water loosened the hair, and scraped again and again.

Another technique was to soak the skins in urine and leave them to rot until the hair came off. A third method involved tying a newly flayed skin to a heifer, with the hair side against the cow’s skin. In a day or two, the hair would be loose enough to pluck off.

When suitably hairless, the skins were stretched on a frame and set in the shade to dry. After rubbing them smooth with pumice (plenty of that in volcanic Iceland), the parchment was made soft and pliable by twisting it and pulling it back and forth through a ring made from a cow’s horn. Quill pens were cut from swan, goose, or raven feathers (also easily come by in Iceland); left-wing feathers were best for right-handed writers because they bent away from the eye.

Ink was made from the bearberry plant, mixed with a clay commonly used to dye wool black and a few shavings of green willow twigs. The mixture was softened in water, then simmered until it became sticky. “Let a drop fall onto your fingernail,” says one recipe. “If it remains there like a little ball, then the ink is ready.” A little bit of gum from the first milk of a young ewe or heifer was added to the ink to make it shiny. (To compare this to ink-making elsewhere in Europe, see my “How to Make a Medieval Book: Part II.”)

The result was ink that was black, glossy, and impermeable to water, which was a very good thing for people who often traveled by ship. Books are rarely mentioned in medieval Icelandic texts, but in one famous shipwreck, a priest is desolate when his book chest is swept overboard. Learning a few nights later that it had washed ashore, he hurried to the spot to dry out his books; it took him six weeks. Mold is the one thing a parchment book cannot survive.

Luckily for us, three parchment copies of Snorri Sturluson’s Edda survived until the 1600s, when they were published. The Edda has been in print ever since, available to be read by Tolkien, Gaiman, and countless other fantasy writers whose work is imbued with the spirit of Norse mythology.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan.

Learn more at nancymariebrown.com

Published on October 17, 2012 09:24

October 9, 2012

Who Discovered America?

Happy Leif Eiriksson Day! If you know the name you know this Viking explorer discovered America 500 years before Columbus—which is why the official U.S. holiday, Leif Eiriksson Day (October 9), comes before the official Columbus Day (October 12).

Happy Leif Eiriksson Day! If you know the name you know this Viking explorer discovered America 500 years before Columbus—which is why the official U.S. holiday, Leif Eiriksson Day (October 9), comes before the official Columbus Day (October 12).But what happened next? Leif never went back. It was his sister-in-law who tried to settle the Vikings’ Vinland, or “Wine Land,” so today I’ll be celebrating Gudrid the Far-Traveler Day.

Gudrid knew the killing force of the sea, of weeks at the mercy of the winds, of fog that froze on the rigging, when “hands blue with cold” was not a metaphor. She knew how fragile a Viking ship was. Sailing from Iceland to Greenland as a girl, she was shipwrecked, plucked off a rock by Leif, who thereby earned his nickname “the Lucky.”

Knowing the risks, Gudrid and her husband, Leif’s brother Thorstein, sailed west off the edge of the known world. They were “tossed about at sea all summer and couldn’t tell where they were,” says one of the medieval Icelandic Sagas. Just before winter, they reached a Viking farm near Greenland’s modern capital, Nuuk, a distance they could have rowed in six days.

That winter, Gudrid’s husband and crew died. Come spring, Gudrid ferried their bones south to Leif’s farm and buried them by the church. She remarried, to a rich Icelandic merchant called Karlsefni, and here’s the kicker: She set sail again. “Making a voyage to Vinland was all anyone talked about that winter,” says the saga. “They all kept urging Karlselfni to go, Gudrid as much as the others.”

Leif Eiriksson in Reykjavik.When I tell people I’ve written a book about Vikings, they expect a pageant of bloody berserks, like the Sega Viking game “Battle for Asgard” or the Viking movie, “Last Battle Dreamer.” Viking, you’d think, meant man with a big axe.

Leif Eiriksson in Reykjavik.When I tell people I’ve written a book about Vikings, they expect a pageant of bloody berserks, like the Sega Viking game “Battle for Asgard” or the Viking movie, “Last Battle Dreamer.” Viking, you’d think, meant man with a big axe. But for me, the classic Viking is Gudrid the Far-Traveler. Viking women could divorce if their husbands didn’t “satisfy” them. They could own farms, as Gudrid did, or ships. No Viking ship sailed without a woman’s help—for the women wove the sailcloth.

Gudrid and Karlsefni set off in three ships—one of which was hers. They landed, apparently, in Newfoundland; archaeologists have studied the Viking ruins at L’Anse aux Meadows for 40 years. The three longhouses can each sleep a ship’s crew. Jasper strike-a-lights found inside came from Greenland and Iceland. A spindle whorl, used for spinning yarn, proves a woman was there.

The most remarkable finds, however, are three butternuts and a piece of butternut wood worked with a metal tool.

Where was “Wine Land”? The sagas mention salmon and tall trees. They tell of strangers who had never seen an axe, were delighted to taste milk and traded furs for strips of red wool cloth; who fought with stone-tipped arrows and whose numbers were overwhelming.

Butternuts never grew in Newfoundland. But the pattern of Indian settlements and the ancient ranges of trees and fish suggest that Vinland stretched from Newfoundland south to the Miramichi River in New Brunswick. There the Vikings met the ancestors of the Beothuck Indians.

Gudrid the Far-Traveler.The Icelandic sagas say little about Gudrid directly. She was beautiful, intelligent and had a lovely singing voice. Most important, she “knew how to get along with strangers.” One saga shows Gudrid in the New World, failing to communicate with a native woman. The implication is clear: If she couldn’t get along with these strangers, no one could. Perhaps Gudrid decided the Vikings should abandon their colony.

Gudrid the Far-Traveler.The Icelandic sagas say little about Gudrid directly. She was beautiful, intelligent and had a lovely singing voice. Most important, she “knew how to get along with strangers.” One saga shows Gudrid in the New World, failing to communicate with a native woman. The implication is clear: If she couldn’t get along with these strangers, no one could. Perhaps Gudrid decided the Vikings should abandon their colony.Perhaps the Vinland expedition itself was her idea. She packed up and set sail there twice—with two different husbands. Although the sagas disagree on the particulars, her hand in the preparations each time is clear.

Realizing this—that Gudrid was the explorer, not just her men—I knew that if I were to pick a Viking to name today after, it would be Gudrid the Far-Traveler.

Learn more at nancymariebrown.com

Published on October 09, 2012 06:43

October 3, 2012

A Tale of Two Wizards

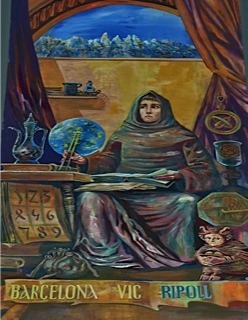

Gerbert of Aurillac as a young monk.

Gerbert of Aurillac as a young monk.Fresco in the church of St. Simon.One book leads to another. That’s how I usually answer the question, Where do you get your ideas?

The Far Travelercertainly led to The Abacus and the Cross. Writing about the adventurous Viking woman Gudrid the Far-Traveler, I found myself making an imaginary pilgrimage to Rome just after the year 1000. Wondering which pope (if any) Gudrid had met, I discovered Gerbert of Aurillac, Pope Sylvester II. I was astonished. Nothing in my many years of reading about the Middle Ages had led me to suspect that the pope in the year 1000 was the leading mathematician and astronomer of his day. That sense of surprise inspired the book.

But sometimes the connections between books reveal themselves long after the inspiration phase is past. Writing my latest, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, I thought I was solving another puzzle in The Far Traveler: Where did the Icelandic sagas come from?

As I’ve said here before, I believe Snorri Sturluson deserves the credit for writing the first true saga, and so Song of the Vikings presents his biography.

Snorri grew up at Oddi, a large estate in the south of Iceland where there was a famous school. This school was set up in about 1100 by the priest Saemund the Wise, about whom a fantastic set of legends remains, but little real information.

My favorite collection of tales about

My favorite collection of tales aboutSaemund the Wise. In his youth, Saemund studied in “Frakkland,” perhaps in Paris at the university that would become the Sorbonne—though the later folktales say Saemund studied at the Black School run by Satan himself, where the students lived in the dark and studied books written in letters of flame. Satan claimed the last student out the door each year as his payment, but Saemund outfoxed him. He wore a great cloak; when Satan grabbed him, Saemund shrugged off his cloak and slipped away safe. Or, says another tale, when Satan cried, “Halt, you are the last!” as Saemund was about to step into the sunshine, Saemund pointed to his shadow on the wall and replied, “No, there’s one behind me.” He had no shadow for the rest of his days.

Saemund tricked the devil into ferrying him dryshod from Norway to Iceland. He tricked the devil into building a bridge over the river Ranga. He tricked him into fetching the hay into his barn ahead of a rainstorm. He tricked him into changing into a gnat and crawling into a bunghole, which Saemund promptly plugged. To get out, the devil had to promise to come when Saemund whistled.

These tales were first written down in the 1800s, but one survives from Snorri’s days, in the Saga of Bishop Jon written by the Icelandic monk Gunnlaug Leifsson, who died in 1219. (Gunnlaug rather liked magicians; he also translated into Icelandic the fabulous “Prophecies of Merlin” from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain.)

Bishop Jon OgmundarsonSaemund had studied abroad so long, Gunnlaug wrote, that he forgot everything from his youth—even his name. But his friend Jon Ogmundarson finally found him. He described Iceland to Saemund, then Oddi, before finally sparking a glimmer of memory.

Bishop Jon OgmundarsonSaemund had studied abroad so long, Gunnlaug wrote, that he forgot everything from his youth—even his name. But his friend Jon Ogmundarson finally found him. He described Iceland to Saemund, then Oddi, before finally sparking a glimmer of memory. Said Saemund, “Now I seem to remember that there was a hillock in the home field of Oddi where I always played.”

His friend convinced him to come home, but Saemund said his master would never give him leave. They made a plan and on a cloudy night slipped away. The master searched, but could not find them until the next night, when the skies cleared and he could read the stars.

Saemund read the stars too. He saw his master coming. “Quick,” he said, “fill my shoe with water and put it on my head.”

“Bad news!” said the master. “The Icelander has drowned my student.” He turned back. The next night he looked again. He located Saemund and rode after him. “Quick,” said Saemund, “fill my shoe with blood and put it on my head.”

“Bad news!” said the master. “The Icelander has murdered my student.”

The third night he searched the skies once more. “Aha!” he cried. “You are still alive, which is good, but I have taught you more than enough, for now you get the better of me. So fare you well and much may you accomplish.”

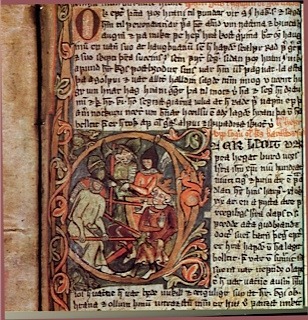

Gerbert the Wizard, in a 15th-century

Gerbert the Wizard, in a 15th-centuryLives of the Popes.When I read this tale in the Saga of Bishop Jon, I had a strange jolt of recognition. I knew the story. It had been written down in Latin in the 1120s by the English cleric William of Malmesbury—but his hero was not the Icelander, Saemund the Wise. It was the Scientist Pope, Sylvester II, born Gerbert of Aurillac and known in his lifetime as the leading mathematician and astronomer of his age. After his death in 1003, Gerbert acquired a reputation as a wizard, as I explain in the last chapter of The Abacus and the Cross.

Chances are that Saemund heard the tale of Gerbert the Wizard in Paris and brought it home to Iceland, where it became attached to him—and eventually created the magical linkage between two of my books that I would have said had very little in common.

Parts of this essay were adapted from my forthcoming biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, available in October from Palgrave Macmillan.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on October 03, 2012 07:53

September 26, 2012

The Essential Iceland

“You cannot take the tunnel today,” proclaimed my friend Þórður.

“You cannot take the tunnel today,” proclaimed my friend Þórður.It was too sunny. A brilliant sunny day in September of last year, and I was off on a roadtrip from Reykjavik to Reykholt, home of the greatest writer of the Middle Ages, the Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson.

The fall colors were bright—as bright in Iceland as they are now, here in Vermont, something that surprised me.

So instead of taking the coast road north (and the time-saving tunnel under Hvalfjordur), I took Þórður's advice and drove inland from Iceland’s capital city to Thingvellir, where the ancient open-air parliament or Althing was held, and followed an old road north from there.

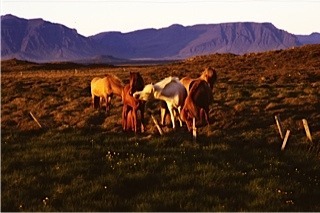

I was in the middle of writing Song of the Vikings, my biography of Snorri Sturluson, and I wanted to see the Iceland he saw. How better than in a jeep, driving the old road north from the Assembly Plains.

Snorri went this way on horseback. He was probably more comfortable on his smooth-gaited Icelandic horse than I was in my rented jeep. The road is washboarded—torturous—more than you can ask a set of shock-absorbers to handle.

The vast brown plain looks smooth from a distance, but it is full of broken ground, boulders, hidden streams, and crevices.

It’s desolate. One bus passed in two hours—a group of medieval studies students from the University of Iceland also taking advantage of this sunny day to tour from Thingvellir to Reykholt.

I pulled over to pee, and, of course, a second car came by, a regular car (not a jeep), and going rather fast, I thought, kicking up dust driving right into the sun. The old woman in the passenger’s seat looked horrified. She had a long, bumpy road to go.

A bit of silvery glacier, like an inverted smile. A raven kronking. A flock of little brown birds with wings of white. Patches of dirty old snow, of lichen burned a brilliant red. Long stretches of nothing but gold-brown rocks.

After three hours of slow driving and many stops for photos, I was very tired (too much of a good thing) and happy to come down into the valley and drive a paved road. There was grass beside the Geita, golden yellow with heavy seedheads, and red-leaved brush on the hillsides.

Along Hvitarsida, the White River snaked through golden birches tall as hedges. I came back a day or two later to picnic and watch the light play over the woodlands.

After a sprinkle of rain, Iceland’s autumn colors can be almost gaudy. As brilliant as the fall foliage in Vermont—though Iceland’s trees are too short to form that golden leafy canopy Vermont provides.

No waterfalls like this one in Vermont, though, with jets bursting out through the porous lava rock.

A rainbow welcomed me home to Reykholt, home of the 13th-century chieftain and writer, Snorri Sturluson. Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths will be published October 30 by Palgrave Macmillan.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 26, 2012 09:30

September 19, 2012

The Flat Earth Error

How many times have you heard it said that people in the Middle Ages thought the world was flat?

How many times have you heard it said that people in the Middle Ages thought the world was flat?When I was working on The Abacus and the Cross, my biography of the Scientist Pope, I was thrilled to find a map of the world drawn shortly before the year 1000. This map appears in a standard medieval geometry textbook. It is drawn as a circle, and a caption at the top explains that the circle depicts one hemisphere of the globe. Around the edge of the circle, another caption refers to the method devised by Eratosthenes in 240 B.C. for calculating the circumference of the earth. That method was well-known to medieval scholars, who routinely referred to the earth as “round as an apple” or an egg.

This map of the spherical world from before the year 1000 is in the Staatsbibliothek Berlin (Preussicher Kulturbesitz, Phill. 1833 (Rose 138), fol. 39v). It was published in 1996 in Autour de Gerbert d’Aurillac, le Pape de l’an Mil, edited by O. Guyotjeannin and E. Poulle.

This map of the spherical world from before the year 1000 is in the Staatsbibliothek Berlin (Preussicher Kulturbesitz, Phill. 1833 (Rose 138), fol. 39v). It was published in 1996 in Autour de Gerbert d’Aurillac, le Pape de l’an Mil, edited by O. Guyotjeannin and E. Poulle.Yet in the late 1980s, historian of science Jeffrey Burton Russell, author of Inventing the Flat Earth, found the “fact” that medieval people thought the earth was flat in a 1983 textbook for fifth-graders, a 1982 text for eighth-graders, and in the 1960, 1971, and 1976 editions of the college textbook, A History of Civilization. He even found it in the bestselling 1983 book,The Discoverers, by the former Librarian of Congress, Daniel Boorstin.

Two writers share most of the blame for this: Petrarch and Washington Irving.

The Italian writer Petrarch (1304-1374) is known for two things: developing the sonnet, and coining the term “the Dark Ages.” Sometimes called the first humanist, Petrarch divided history into Ancient (before Rome became Christian in the fourth century) and Modern (his own time). Everything in between was dark. Writes Russell, “The Humanists perceived themselves as restoring ancient letters, arts, and philosophy. The more they presented themselves as heroic restorers of a glorious past, the more they had to argue that what had preceded them was a time of darkness.” (Stephen Greenblatt, in his popular book, The Swerve, is still making this argument; I’ll discuss that in a future blog post.)

The humanists also had a political motive. The Italian cities wanted to break free of the Holy Roman Empire. That meant denying all the contributions to civilization promoted by forward-thinking emperors such as Charlemagne or Ottos I, II, and III (patrons of the Scientist Pope), as well as those of the Church itself. Petrarch and his fellow humanists saw no contradiction in the fact that all of the ancient “letters, arts, and philosophy” they “discovered” had been copied, and so preserved, in the scriptoria of monasteries and cathedrals through the thousand years of the so-called darkness.

A clearly spherical earth, in the mid-14th century Bible Historiale of John the Good (BL MS Royal 19 DII).

A clearly spherical earth, in the mid-14th century Bible Historiale of John the Good (BL MS Royal 19 DII).Skip to the American writer Washington Irving (1783-1859). In his time, studying the Middle Ages was considered “a ridiculous affectation in any man who means to be useful to the present age,” according to Henry St. John Bolingbroke, whose political writings influenced Thomas Jefferson, among others.

This attitude made it easy for Washington Irving, in The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, to rewrite the discovery of the New World in 1492. In the 1820s, having just published the stories “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” to popular acclaim, Irving went to Spain, where he was given access to original documents about Columbus. Finding the truth a little “dry,” in his words, he decided his hero’s story required more dramatic tension. Writes Russell: “It was he who invented the indelible picture of the young Columbus, a ‘simple mariner,’ appearing before a dark crowd of benighted inquisitors and hooded theologians at a council of Salamanca, all of whom believed, according to Irving, that the earth was flat like a plate.”

What in fact they believed—and the original records of the council still exist—was that Columbus was fudging his numbers. Using the standard method given in medieval geometry textbooks—and on the map from before the year 1000—the Council of Salamanca calculated the circumference of the earth to be about 20,000 miles (it is actually about 25,000 miles) and the distance between one degree of latitude or longitude at the equator to be 56 2/3 miles (it is actually 68 miles). Columbus thought the earth was much smaller. He said a degree was 45 miles and the span of ocean between the Canary Islands and Japan only 2,765 miles—twenty percent of the actual figure. If he had not providentially bumped into America, Columbus would—as the experts in Salamanca believed—have run out of food and fresh water long before he reached Japan. Columbus, says Russell, had “political ability, stubborn determination, and courage” on his side. His opponents had “science and reason” on theirs.

Washington Irving took science and reason and gave them to Columbus—and it was Irving’s version of history that became common knowledge. Why? Americans, says Russell, “wanted to believe that before the dawn of America broke, the world had been in darkness.”

You can see more medieval images of a round world on Donna Seger’s blog, Streets of Salem: http://streetsofsalem.com/2011/06/13/the-medieval-world/She writes (sadly): “every year I poll the incoming freshmen in my World History class about what they were taught in primary and secondary school and every year more than half of them raise their hands in support of the medieval flat earth.”

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 19, 2012 09:12

September 12, 2012

The Pace Gene

Icelandic horses are famously either four-gaited or five-gaited. They can walk, trot, and canter (or gallop), like all horses can. But Icelandics can also tolt (a kind of running walk) and pace, which is a racing gait. No other breed of horse can coordinate the movement of its legs in so many different ways, I discovered when researching my book A Good Horse Has No Color in the late 1990s. Recently I learned exactly why:

Icelandic horses are famously either four-gaited or five-gaited. They can walk, trot, and canter (or gallop), like all horses can. But Icelandics can also tolt (a kind of running walk) and pace, which is a racing gait. No other breed of horse can coordinate the movement of its legs in so many different ways, I discovered when researching my book A Good Horse Has No Color in the late 1990s. Recently I learned exactly why:In August, a group of Swedish, Icelandic, and American scientists published an important scientific paper in the journal Natureidentifying the genetic mutation that causes Icelandic horses to tolt and pace. See http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v488/n7413/full/nature11399.html

Led by geneticist Leif Andersson of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Uppsala University, the group first compared the genes of 30 four-gaited Icelandic horses to 40 five-gaited Icelandic horses. They found “a highly significant association between the ability to pace and a single nucleotide polymorphism” or SNP (pronounced “snip”) mutation on one chromosome in the horse genome.

They confirmed that association by testing an additional 352 Icelandic horses (both four-gaited and five-gaited), along with 808 horses of other breeds.

The SNP mutation occurred in a gene named DMRT3. Investigating this region in mice, the researchers discovered that it controls leg movement. The gene is expressed in the spinal cord, producing neurons that affect length of stride, swing time or flexion, and both front-back and left-right coordination.

To pace, an Icelandic horse must possess two copies of the mutant DMRT3gene. To tolt, a horse needs one copy.

You can watch an Icelandic horse tolt on YouTube, courtesy of my friend Stan Hirson: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7rWeW...

BASIC GENETICSTo understand what the Nature paper meant, I needed to review some terminology. Fortunately, I had learned a lot of that when coauthoring the book Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientist’s View of Genetically Modified Foods with Penn State geneticist Nina Fedoroff in 2004.

The genome, I recalled, was the horse’s complete set of genes, packed into the chromosomes inside each of its cells. Genes are made of DNA, a long molecule that forms a double helix, looking like a twisted ladder. DNA itself is made up of four small molecules, the nucleotides adenine (known as A), cytosine (C), thymine (T), and guanine (G).

In the 1960s, scientists learned how to read the DNA code. Each sequence of three letters, each codon, such as GAG or GAA or AAA, stands for an amino acid (except for three codons, which instead mean “stop”). When the code is read, the cell’s machinery links the specified amino acids together into a chain, which is then folded up to become a functioning protein. Each protein made by the body has its corresponding DNA code—a gene.

There’s more than genes in a genome, if by gene we mean the DNA sequence that codes for a protein. Many DNA sequences don’t code for proteins. Instead, they control when and where in the body certain proteins are made. Still other sequences are thought to be useless junk, though scientists keep finding uses for more and more of this junk, as the recent ENCODE study shows. See: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v489/n7414/full/nature11247.html

An Icelandic horse showing trot.

An Icelandic horse showing trot.But the mutation that allows Icelandic horses to tolt and pace is a relatively easy one to understand. A SNP mutation, or single nucleotide polymorphism, means that one nucleotide (one A, C, T, or G) in the DNA sequence of the DMRT3gene was wrong. The three-letter codon that this one nucleotide was part of should have coded for an amino acid. Instead, it said “stop.” The mutant form of the gene found in Icelandic horses is significantly shorter than the wild type found in three-gaited horses.

In fact, all gaited horse breeds tested, including the Icelandic horse, the Kentucky Mountain Saddle horse, the Missouri Fox Trotter, the Paso Fino, the Peruvian Paso, the Rocky Mountain horse, the Standardbred, and the Tennessee Walking horse, had the short, mutant type. All three-gaited breeds—Arabians, Gotland ponies, North-Swedish draft horses, Przewalski’s horses, Shetland ponies, Swedish Ardennes, Swedish Warmbloods, and Thoroughbreds—had the long, wild type.

HISTORY OF TOLTNow the terms “wild type” and “mutant” are value-laden. Geneticists used to use “wild type” to refer to the typical form found in nature. But it’s now accepted that genes can come in many different forms in a single species without any one of them being more typical than another.

In this study, the researchers seem to have assumed that, since all horses can walk, trot, and canter/gallop, these gaits are more typical. The fact that the Przewalski’s horse—the closest wild relative of the domesticated horse—has only three gaits supports this conclusion. The researchers therefore assigned the label “wild type” to the long version of the gene, the one that produces three-gaitedness.

But the reverse could be true. And even if the Icelandic horse’s shorter DMRT3 gene is not the wild type, the mutation must have happened very early in the history of horse evolution: When anthropologist Mary Leakey uncovered the tracks of three 3.5-million-year-old equids in East Africa, she found their footfalls to match those of a tolting Icelandic horse traveling at ten miles an hour.

The same horse showing canter.

The same horse showing canter.Horse historians, especially those (like me) within the Icelandic horse community, have long argued that gaitedness was bred out of horses since medieval times, not bred in.

As I wrote in A Good Horse Has No Color, the first Icelandic horses were bred for strength, speed, color, and a smooth, untiring traveling gait. Few of Iceland’s bridle paths, though ancient and well-worn, are smooth and even. Interrupted by birch brush and roots, they cross farm fields heaved and hummocked by frost, pocked and pitted with bogs. They angle up and around precipitous slopes, wind along rocky rivers, or pick their way through lava wastes. Yet even today, when riding fast and far is only a pleasure, not a necessity, Icelandic horses routinely cover thirty miles a day. On one trek organized in 1994, one thousand kilometers—six hundred miles—were ridden in two weeks, an average of over forty miles each day.

When Iceland closed its borders to the importation of horses sometime in the Middle Ages (no medieval source gives us an exact date), today’s fine distinctions between fast tolt, slow tolt, trot-tolt, pacey-tolt, traveling pace, and piggy pace were unknown. A good horse was comfortable to ride all day, which meant it possessed some mid-speed gait other than a jarring, jouncing trot.

In the rest of medieval Europe, such a horse was known as an ambler, palfrey, or jennet, and would be ridden by ladies or noblemen or knights not in armor. The word “ambler” comes from the early Roman ambulator, or walker, while a trotting horse in these same documents is called a cussator or cruciator, a “tormentor” or “crucifier.” “Palfrey” derives from the Greek parippi or the Celtic paraveredus, both meaning a horse used for long journeys. The jennet was originally a particular breed out of Spain, known for its easygoing slow pace.

When roads became widespread during the Renaissance and carriages were the noble way to travel, selective breeding for smooth-gaited riding horses declined. People bred for trotters, faster and with more stamina when under harness. Only in the roadless outposts of European culture were the smooth, lateral gaits like the tolt retained, producing, in the New World, such breeds as the Tennessee Walking Horse and the Peruvian Paso.

The same horse showing tolt.

The same horse showing tolt.NATURAL GAITSThe Icelandic horse experts I consulted in the 1990s, while writing A Good Horse Has No Color, assured me that the ability to tolt was genetic and that it depended on the pace. According to one, “It is part of the quality of the trait, how easy it is to breed it. Well-bred Icelandic horses should therefore be almost self-trained to tolt.” Said another, “Not all horses have pace worth showing, but it is considered good for the tolt if the horse has some pace. It is thought that without breeding for pace, the tolt would be lost.”

The Nature study proves they were right. If you breed a mare and a stallion who each have only one copy of the short DMRT3 gene, you can get a foal that has no copies of it: This foal will be three-gaited. That’s why this study is so important to Icelandic horse lovers. It tells us exactly how to preserve what we love best about our breed: the gaits.

For breeders who want to know in advance of training and evaluation if a foal is five-gaited, a simple DNA test is already available from Capilet Genetics: http://www.capiletgenetics.com/en/icelandic-horses-2. The company notes, however, that “the quality of the pace is a quantitative trait that is determined by many genes working together and the environment (training).”

In other words, the short DMRT3 gene is necessary, but not enough for true flying pace. The Swedish study found that 31 percent of the horses considered four-gaited were genetically five-gaited: They had two copies of the short DMRT3gene. The classification was done by Thorvaldur Arnason of the Agricultural University of Iceland in Borgarnes, based on WorldFengur records. Their pace was simply not good enough for them to show it in competition.

The same caveat holds for the tolt. Without one copy of the gene, your horse cannot tolt. But genetics alone cannot explain how wellyour horse tolts.

The horse in the gait photos above is Parker fra Solheimum, a first-prize Icelandic stallion owned and ridden by Sigrun Brynjarsdottir. Visit them at http://usicelandics.com. On the US Icelandic Horse Congress’s website ( www.icelandics.org ), you learn more about Icelandic horses. Or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson’s video blogs, Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses ( http://www.lifewithhorses.com/ ). Stan's beautiful video of an Icelandic horse tolting is also available there.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on September 12, 2012 13:34

September 5, 2012

In Search of the Scientist Pope

The Abacus and the Cross, my biography of the Scientist Pope, Gerbert of Aurillac (Pope Sylvester II), will be out in paperback this fall. To celebrate, here’s a little essay about my quest to discover the pope of the year 1000:

The Abacus and the Cross, my biography of the Scientist Pope, Gerbert of Aurillac (Pope Sylvester II), will be out in paperback this fall. To celebrate, here’s a little essay about my quest to discover the pope of the year 1000:I thought I spoke French, but the young man’s bright sentences blurred and vanished. My redheaded friend, still flirtatious at fifty, was getting through to him a lot faster in smiles and shrugs and a little Spanish, draping her lime-green scarf across his papers, leaning in.

He was not a monk, though this was a monastery.

We had driven the scalloped edge of Catalonia north: mile upon mile of terraced vineyards, white cliffs sheer to the sea. We had not stopped at the castle with its feet in the tide, or at the winery. I was on a quest.

A forgotten French monk had passed this way a thousand years ago, when most of Spain was Islamic al-Andalus, and Arabic was the language of science. His name was Gerbert of Aurillac. He was the first person in the Christian West to teach math using the nine Arabic numerals and zero. In the year 999, he became pope.

We tracked him through Barcelona, Girona, and Vic. We climbed steep stone stairs to hilltop church-fortresses, surrounded by the tinkling of goat bells—at least we climbed halfway up. We both suffer a fear of heights. We were en route to a clutch of churches high in the Pyrenees when I checked my email. I’d asked a Swiss historian for an interview and told him where I was.

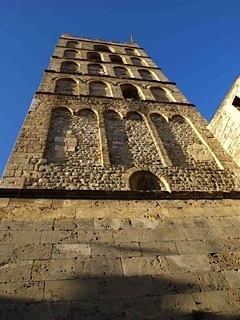

Go to Elne cathedral, he said, où il y a une inscription dans la pierre ... Elle est de Gerbert, distribuée sur une croix… An inscription on a stone. About Gerbert. On a cross.

We found the cathedral, a golden-stone pile on its dusty hill. All the streets in town converged on it, staunch and square, its broad doors barred, its windows higher than a stone could be thrown. A gate in the wall opened into a cemetery—a good place for carved crosses, I thought, but found nothing. My friend tried a door. I followed her giggle and found her, tête-à-têtewith handsome Romain.

Elne’s cloister was famous for stone carvings—devils and dragons and laughing sprites. Romain unfolded a brochure to pony us through his French. Peut-être this stone? She is très fameux.

C’est une croix, I said.

He shook his head. There were no famous crosses.

Show him your notebook, Ginger hissed.

Indeed! I had copied out the email.

O! C’est votre professeur? Romain pointed to the name, amazed. He had just mailed the Swiss historian photos of names carved in a stone—O!

In the 1960s they had moved the main altar. Lifting the marble top, they spied names carved on the platform beneath. One was cut in the shape of a cross.

Can I see it?

Désolé. Mass is in session. Then we close. Come back tomorrow? Non? I will send you the photos.

But a photo of this stone was not enough.

In 2005, I volunteered on an archaeological dig in Iceland. We excavated a house built just after the year 1000. Medieval books say a woman named Gudrid explored the New World around the year 1000; she sailed back to Iceland and built a house here, on the very farm where we worked. So I called the dig “Gudrid’s house.” The scientists were annoyed. You cannotsay that. That’s a story. You have no proof. Not unless you find a stone by the doorstep that reads Gudrid was here.

Of course, we found no such stone.

The story of the Scientist Pope seems equally improbable. Wasn’t the Church anti-science in the Dark Ages? Yet medieval books say Gerbert was sent by his monastery to the border of Islamic Spain in 967 to learn math. That he started a famous science school at Reims cathedral. That he tutored the Holy Roman Emperor and the king of France.

We understand the Dark Ages about as well as I speak French.

Two months later, I returned to Elne. Thanks to my redheaded friend, Romain remembered me. He dug out a flashlight and led me deep into the darkness of the church. Hung flat on a wall was a large gray stone—like a radiator, exactly—a row of wooden chairs brushing up against it. I stood on a chair to get a better view; he aimed the light. Carved on the uptilted edge of the stone, in the shape of a cross, was the name “Gerbertus.”

I traced the letters with my thumb: Gerbert was here.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in the medieval world.

Published on September 05, 2012 08:14

August 29, 2012

Song of the Vikings: What’s in a Title?

Authors don’t have total say over their books’ titles. Publishing houses have people who specialize in such things as the marketability of a phrase—something I’m apparently not so talented at, since only two of the titles I’ve picked for my five books have made it through the process.

Authors don’t have total say over their books’ titles. Publishing houses have people who specialize in such things as the marketability of a phrase—something I’m apparently not so talented at, since only two of the titles I’ve picked for my five books have made it through the process.“Song of the Vikings,” for instance, wasn’t my choice for my upcoming biography of Snorri Sturluson, the story of how a scheming Icelandic chieftain gave Norse mythology to the world.

But it has a pleasing tension to it. Singing is not the first action that comes to mind when thinking about Vikings. Yet it was through their songs—using “song” the way Walt Whitman did in “Song of Myself”—that Snorri Sturluson, writing in the early 1200s, was able to reconstruct the Viking world of centuries before. Viking songs are the source of almost everything we know about the gods, kings, and warriors who ruled the North between 793 and 1066 (the Viking Age) and for two centuries after, until the Icelandic Sagas were written—some of the best by Snorri himself—in the 1200s.

Poets, or skalds, were a fixture at the Norwegian court for over four hundred years. They were swordsmen, occasionally. But more often in his collection of sagas about the kings of Norway, Heimskringla, Snorri depicts skalds as a king’s ambassadors, counselors, and keepers of history. They were part of the high ritual of his royal court, upholding the Viking virtues of generosity and valor. They legitimized his claim to kingship. Sometimes skalds were scolds (the two words are cognates), able to say in verse what no one dared tell a king straight. They were also entertainers: A skald was a bard, a troubador, a singer of tales—a time-binder, weaving the past into the present.

Illustration by Gerhard Munthe.Who would remember a king’s name if there were no poems composed about him? In a world without written record—as the Viking world was—memorable verse provided a king’s immortality. As the skald Sigvhat Thordarson said to King Olaf the Saint (1015-1030), in Lee Hollander’s 1964 translation of Heimskringla:

Illustration by Gerhard Munthe.Who would remember a king’s name if there were no poems composed about him? In a world without written record—as the Viking world was—memorable verse provided a king’s immortality. As the skald Sigvhat Thordarson said to King Olaf the Saint (1015-1030), in Lee Hollander’s 1964 translation of Heimskringla:List to my song, sea-steed’s- sinker thou, for greatly skilled at the skein am I— a skald you must have—of verses; and even if thou, king of all Norway, hast ever scorned and scoffed at other skalds, yet I shall praise thee.

We know the names of over two hundred skalds from before 1300, including Snorri, one of his nieces, and three of his nephews. We can read (or, at least, experts can) hundreds of their verses: In the standard edition, they fill a thousand two-column pages. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking age, what they loved, what they despised. The big surprise is how much they adored poetry. Vikings were ruthless killers. They were also consummate artists.

“These old Norse songs have a truth in them, an inward perennial truth and greatness,” said the Victorian critic Thomas Carlyle. “It is a greatness not of mere body and gigantic bulk, but a rude greatness of soul.”

Illustration by Gerhard Munthe.Whether Viking songs were sung, chanted to the strumming of a harp, or simply recited, we don’t know. Recently, Benjamin Bagby and the group Sequentiahas tried to reconstruct the music of some Viking songs (with mixed results, in my opinion) on their 1999 album “Edda.”

Illustration by Gerhard Munthe.Whether Viking songs were sung, chanted to the strumming of a harp, or simply recited, we don’t know. Recently, Benjamin Bagby and the group Sequentiahas tried to reconstruct the music of some Viking songs (with mixed results, in my opinion) on their 1999 album “Edda.” You can sample it at Amazon here: http://www.amazon.com/Edda-Icelandic-Medieval-Iceland-Sequentia/dp/B00000IFOM

Or on Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ghq4nrvldkY And: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QaUwG762FfU&feature=related

For a completely different approach to the concept of a “Song of the Vikings,” listen to this delightful recording made in 1915 by the Victor Male Quartet, available through the National Jukebox project of the Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/4021/

And finally, there’s Todd Rundgren’s “Song of the Vikings” here:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bO95rnkoKY4

Let me know if you find any more.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 29, 2012 07:30

August 22, 2012

Horse of the Gods

Horses were sacred in many of the old religions of northern Europe. When Iceland was discovered in about 870, the gods most Scandinavians worshipped, according to Snorri Sturluson’s Edda, rode Shining One, Fast Galloper, Silver Forelock, Strong-of-Sinew, Shaggy Fetlock, Golden Forelock, and Lightfoot. Only the mighty Thor the Thunderer went on foot across the rainbow bridge to the Well of Weird, where the gods held court each morning beside the great ash tree, Yggdrasil (translated by some scholars as “Odin’s Horse”).

Horses were sacred in many of the old religions of northern Europe. When Iceland was discovered in about 870, the gods most Scandinavians worshipped, according to Snorri Sturluson’s Edda, rode Shining One, Fast Galloper, Silver Forelock, Strong-of-Sinew, Shaggy Fetlock, Golden Forelock, and Lightfoot. Only the mighty Thor the Thunderer went on foot across the rainbow bridge to the Well of Weird, where the gods held court each morning beside the great ash tree, Yggdrasil (translated by some scholars as “Odin’s Horse”).The gods of Day and Night drove chariots drawn by Skinfaxi (“Shining Mane”) and Hrimfaxi (“Frosty Mane”): The brightness of the sun was the glow of the day-horse’s mane, while dew was the saliva dripping from Hrimfaxi’s bit. The goddess Gna had a horse that could run “through the air and over the sea.” Called Hoof-Flourisher, it was sired by Skinny-sides on Breaker-of-Fences.

The most famous horse was Odin’s eight-legged steed, Sleipnir, who was born of the god Loki. Only Snorri Sturluson tells the story of Sleipnir’s birth—and who knows how much of it he made up?

One day a giant came knocking at the gates of the gods’ Asgard, Snorri writes, and offered to build them a wall guaranteed to keep out Fire Ogres and Frost Giants. All he wanted in return, he said, were the sun and the moon and the goddess Freyja for his wife. The gods debated. Loki the Trickster suggested they set the giant a time limit—one winter, impossibly unrealistic for the task. That way, Loki winked, they’d get most of a wall and would risk nothing. The giant agreed to the time limit, provided his horse could help him.

Days passed and the wall grew. The giant laid up by day the stones his horse hauled by night. When summer was but three days off, the gods saw for certain the giant would keep his end of the bargain. They wanted out of theirs. Whose idea was it, they argued, to ruin the sky by sending the sun and moon to Giantland? Who promised beautiful Freyja as a giant’s bride? It was Loki, everyone agreed, and he’d better come up with a trick to fix it.

That night as the giant’s horse set off to haul stone, he scented a mare in season. He raced off after her, with the giant in pursuit. All night they galloped about, and work on the wall came to a halt. The giant flew into a rage and began throwing things—at which point Thor stepped in and, swinging his mighty hammer, sent the giant to the realm of the dead before he could do any more damage. Some time later, Loki the Trickster bore a gray foal (Snorri doesn’t tell us if Loki had been able to change out of mare’s shape in the meantime). That foal was Sleipnir, the eight-legged steed, called the best horse among gods and men.

Because of their association with the gods, horses were a worthy sacrifice in ancient Scandinavia. A horse, usually white or gray or with unusual markings, would be ritually slaughtered, its blood sprinkled on the altar, the meat stewed and shared out among the celebrants.

Earlier pagan cults had saved the head and hide and set them up on poles to guard a grave or other holy place, but by the Saga Age, these poles had devolved into a type of natural magic. Egil’s Saga tells of a time when the viking hero Egil, having killed the king of Norway’s son, “picked up a branch of hazel and went to a certain cliff that faced the mainland. Then he took a horse head, set it up on the pole and spoke these formal words: Here I set up a pole of insult against King Eirik and Queen Gunnhild—then, turning the horse head toward the mainland—and I direct this insult against the guardian spirits of this land, so that every one of them shall go astray, neither to figure nor find their dwelling places until they have driven King Eirik and Queen Gunnhild from this country.” Egil set sail for Iceland; a year later, King Eirik was deposed by his brother and had to flee to England.

Photo by Matthew Driscoll from Lehre, Denmark.

Photo by Matthew Driscoll from Lehre, Denmark. When Iceland became Christian in the year 1000, three things were banned: worshipping the old gods in public, exposing children (a form of infanticide), and eating horsemeat, which Pope Gregory III had banned in the year 732 because of its use in pagan rituals.

Sagas covering the conversion period ridicule the old horse sacrifices. The Saga of Saint Olaf tells of the Norwegian king responsible for Christianizing much of the North. In one version, Olaf visited a poor family so benighted that they worshiped the penis of an old cart horse, wrapped in linen and kept in a chest with garlic and herbs so it wouldn’t rot. King Olaf witnessed a ceremony in which the penis was passed from hand to hand around the circle, each person saying a verse over it. When the “idol” came to him, he threw it to the dog. “The king then cast off his disguise and … talked to them of the true faith.”

The story blames an old woman for making the idol. When the cart horse was butchered, she had snatched the penis from the farmer’s son, who was giggling and shaking it at his sister. “She said they shouldn’t waste this or anything else.” It’s not a bad attitude to have.

Illustration by Gerhard Munthe for Snorri's Heimskringla.

Illustration by Gerhard Munthe for Snorri's Heimskringla.Snorri Sturluson and his Edda are the focus of my forthcoming book, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, due out in October from Palgrave Macmillan. I first looked into the myths about Icelandic horses to write A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse, which is out of print but available as an e-book from Amazon.com and Smashwords.com.

In 1999, I published a version of this story in The Icelandic Horse Quarterly, the official magazine of the U.S. Icelandic Horse Congress; shortly afterwards I joined the magazine’s editorial committee. Visit the congress’s website ( www.icelandics.org ) to read a free copy and learn more about Icelandic horses today, or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson’s video blogs, Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses ( http://www.lifewithhorses.com/ )

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 22, 2012 07:43

August 15, 2012

Homosexuality in the Icelandic Sagas

A story I read the other day in The Reykjavík Grapevine, “Iceland’s First Gay Lovers,” surprised me by explaining something I had written about many years ago.

A story I read the other day in The Reykjavík Grapevine, “Iceland’s First Gay Lovers,” surprised me by explaining something I had written about many years ago.In 1997, while researching my book A Good Horse Has No Color , I stayed for some weeks at Snorrastadir in the west of Iceland. One afternoon I listened in as the farmer, Haukur, and another guest, a horsewoman named Hallgerdur, discussed Njal’s Saga,the medieval masterpiece that contains a famous “feminist” character also named Hallgerdur.

Here’s how I described the scene in my book:

…Known for her hip-length hair and her “thief’s eyes,” this storied Hallgerdur had been wooed and wed by the handsome Gunnar of Hlidarendi, that paragon of Icelandic manhood who, according to the saga, could “jump more than his own height in full armor, and just as far backwards as forwards.”

“He could swim like a seal,” the book said.

“There was no sport at which anyone could even attempt to compete with him.”

“There has never been his equal.”

The marriage was a disaster. It ended in Gunnar’s death when, his house surrounded by enemies his wife had made for him, his bowstring broke and he asked for some strands of her long hair to plait into a new one; she refused.

Snorrastadir at midnight.

Snorrastadir at midnight.It was this that Haukur and Hallgerdur were discussing: why the Saga-Age Hallgerdur—an historical woman who lived and died about a thousand years ago—had refused the gift of her hair.

They chattered on too fast for me to more than snatch at the argument. I marveled again that these sagas, of esoteric, antiquarian interest at home, were so alive here, centuries after they were written. I was heading again for that hot cup of tea when Haukur gave out a great guffaw.

“Er Gunnar á Hlidarendi, nú, hommi?!” he asked. “Is Gunnar of Hlidarendi, now, a homosexual?”

I stopped. I looked at Hallgerdur. The answer she was arguing was yes.You could write a dissertation on that one, I thought—Homosexuality in Njal’s Saga. Gunnar did have an unusually close friendship with Njal, whose manhood was in question because he couldn’t grow a beard. I wished I could comprehend the details of Hallgerdur’s thesis and join in the conversation, but though I’d read the saga several times and knew it inside out, my spoken Icelandic wasn’t up to the task. I retreated to the kitchen, where Ingibjorg gracefully drew my attention to the fact that the dishwasher could be unstacked and the table set for dinner. With the clatter drowning out Haukur’s increasing outrage, I replayed the point in English in my head and awarded the set and match to Hallgerdur…

Snorrastadir and the crater Eldborg.

Snorrastadir and the crater Eldborg.That’s what I witnessed in 1997.

I had gone to Iceland first in 1986, after studying Old Norse for several years—and having been taught that the language was “dead,” like Latin. As I wrote earlier in this blog (“Practical Education”), I was delighted to learn to the contrary on that first visit that Old Norse wasn’t “dead” after all. It had just shifted into Icelandic, changing about as much as English has since Shakespeare’s day.

By 1997 (my seventh trip to Iceland), I knew that the sagas themselves were still very much alive, some 800 years after they had been written. Everywhere I went in Iceland, someone shared an allusion from a saga. The medieval past was remembered in the name of every hill and farmstead (not to mention every beer and candybar). There was a saga everywhere I turned.

What I didn’t know, when I witnessed Haukur and Hallgerdur arguing over homosexuality in Njal’s Saga, was the news peg.

Horses at Snorrastadir.

Horses at Snorrastadir.It’s true that Icelandic farmers are surprisingly keen readers compared to the farmers I know in America. Another day I came upon Haukur and a guest comparing the novel Independent People, by Iceland’s Nobel prize-winner Halldor Laxness, to Growth of the Soil, by the Norwegian Nobelist, Knut Hamsun.

But Homosexuality in Njal’s Saga was not Hallgerdur’s idea. The dissertation didn’t need to be written—a book was already in print, as I learned last week from The Reykjavík Grapevine .

In “Íslenska Kynlífsbókin” (The Icelandic Sex Reader), published in 1990, Óttar Guðmundsson, a psychiatrist at the Landspítali hospital in Reykjavík, “famously argued that Njáll and Gunnar, heroes of ‘Njáls Saga,’ were gay and in love with each other,” the Grapevinesays. The newspaper also mentions Óttar’s new book, “Hetjur og hugarvíl” (Anxious Heroes), “devoted to psychoanalysing the main characters of some of the more prominent Icelandic Sagas.”

Looks like I have some further reading to do. And a thank-you letter to send to psychiatrist Óttar Guðmundsson for his help in keeping the Icelandic sagas alive.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 15, 2012 06:06