Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 19

August 8, 2012

The Sorceror’s Horse: An Icelandic Folktale

If I had to choose one favorite horse from all of those mentioned in medieval Icelandic literature, it would be Fluga. She was an exceptionally fast horse—as she should be to earn a name that derives from the verb “to fly.” And for some unknown reason, she has been exceptionally inspiring.

If I had to choose one favorite horse from all of those mentioned in medieval Icelandic literature, it would be Fluga. She was an exceptionally fast horse—as she should be to earn a name that derives from the verb “to fly.” And for some unknown reason, she has been exceptionally inspiring.Horse races were common entertainments in Saga Age Iceland, and horses known for speed were often challenged. The Book of Settlements, or Landnámabók, tells of one such challenge to Fluga, a mare that came over on “a ship with a cargo of livestock” in the early 900s. She probably came from Norway, although horses were brought to Iceland from the British Isles and one, the famous Kinnskaer, an extremely tall horse that had to be fed on grain both summer and winter, according to The Saga of the Men of Thorskafjord, came from Eastern Europe or even Asia.

When the ship bearing Fluga was being unloaded at the harbor of Kolkuos in Skagafjord, she escaped. Thorir Dove-Nose, a freed slave, “bought the chance of finding the mare, and find her he did.”

Apparently he bragged about her speed. One day, the story goes, Thorir was riding along Kjolur, one of the two main routes that cross through the interior wasteland of Iceland. Suddenly he was waylaid by a mysterious character named Orn, “a sorceror who used to wander from one part of the country to another.” Orn “made a bet with him as to which had the faster horse. Orn himself had a particularly fine one. Each of them staked a hundred marks of silver.”

They rode south on Kjolur until they came to a level stretch of land still known as “Dove-Nose’s Racetrack.” They laid out a course and raced off. But “Orn was only half way up the course by the time Thorir met him on his way back, so great was the difference between the two horses.”

Orn took his loss so badly that he went up into the mountains and was never seen again. Fluga was exhausted, so Thorir left the mare behind (Icelanders usually travel with several riding horses, switching the saddle to the next as each one tires) and continued on his way.

Yet when he came back to fetch her several weeks later, he was surprised to find “there was a gray, black-maned stallion with the mare.” Given that the Kjolur route is in the middle of Iceland, set between two of the largest glaciers, it’s unlikely this stallion had wandered away from a nearby farm. Gray horses, particularly, are often magic; the suspicion hinted at is that the stallion is the sorceror Orn himself.

Fluga had a foal the next spring, the story goes, “and from their line sprang the horse Eidfaxi, the one that was taken abroad and killed seven men at Mjors in a single day before he was killed himself.”

There’s no story told about the Battle of Mjors. Eidfaxi remains famous a thousand or more years after his death because he was “the one that was taken abroad.” Eidfaxi is now the name of a magazine about Icelandic horses: The name combines eidur,“oath,” and fax, “mane.”

I learned the legend of Fluga and the sorceror’s horse while writing A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse: I even visited the farm named for her, Flugumyri. In 1998, I published a version of Fluga’s story in The Icelandic Horse Quarterly, the official magazine of the U.S. Icelandic Horse Congress; shortly afterwards I joined the magazine’s editorial committee. (Visit the congress’s website to read a free copy and learn more about Icelandic horses today.) Some years later, I wrote a children’s book based on the Fluga tale (still unpublished).

But Fluga’s great race remained stuck in my brain. So in 2009, I rode Kjolur, the trail Thorir Dove-Nose took from the north of Iceland to the south, with the trekking company Íshestar. On Day Four of our six-day trek, we passed right by the spot known as “Dove-Nose’s Racetrack”—and it was nothing like I had imagined. I’m in the process of writing that story. Let’s just say it’s a little long for a blog post. It may be some time before I come to terms with all I learned--about Iceland, Icelandic horses, and myself--on that long ride.

In the meantime, you can visit the website of my friend Stan Hirson, who shares my fascination with the story of Fluga. His video blogs about Kolkuos and Flugumyri can be found at Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses (http://www.lifewithhorses.com/).

The original story of Fluga (and the quotations above) can be found in The Book of Settlements, or Landnámabók, as translated by Herman Palsson and Paul Edwards (University of Manitoba, 1972). Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on August 08, 2012 08:52

August 1, 2012

Tolkien’s Icelandic Trolls

My recent post on Bilbo Baggins’s ride and the influence of Iceland on JRR Tolkien brought a wonderful response from Þóra Magnúsdóttir in Iceland, who sent me a link to the February 28, 1999 issue of the Icelandic newspaper Morgunblaðið. There, reporter Linda Ásdísardóttir interviewed 89-year-old Arndís Þorbjarnardóttir who had been an au-pair in the Tolkien household while JRR Tolkien was writing The Hobbit.

My recent post on Bilbo Baggins’s ride and the influence of Iceland on JRR Tolkien brought a wonderful response from Þóra Magnúsdóttir in Iceland, who sent me a link to the February 28, 1999 issue of the Icelandic newspaper Morgunblaðið. There, reporter Linda Ásdísardóttir interviewed 89-year-old Arndís Þorbjarnardóttir who had been an au-pair in the Tolkien household while JRR Tolkien was writing The Hobbit.Describing her time in Oxford, Arndís noted that the Tolkien boys often asked her to tell them about Iceland, especially “about trolls and monsters.” After reading The Hobbit, she said, she realized “the professor” had been listening in to her Icelandic tales. He must have, “to create those little folk who have hairy toes just like ptarmigans!”

I must admit I never before saw any similarity between hobbits and ptarmigans.

But I have long thought Tolkien’s trolls were Icelandic.

The troll scene in The Hobbit is one of my favorites. Bert, Bill, and Tom are so blusteringly barbaric, comparing the taste of mutton to manflesh, and Bill’s squeaking purse is such a fine surprise for both Bilbo and the reader. But mostly I liked Tolkien’s scene for its ending:

“Dawn take you all, and be stone to you!” Gandalf pronounced, after having kept the trolls arguing among themselves all night until the sun came up. “And there they stand to this day, all alone, unless the birds perch on them,” Tolkien writes, “for trolls, as you probably know, must be underground before dawn, or they go back to the stuff of the mountains they are made of, and never move again.”

John Rateliff, in his fascinating two-part study, The History of the Hobbit (HarperCollins, 2007), finds Tolkien’s “as you probably know” to be rather coy. Tolkien “seems to have introduced the motif” of trolls turning to stone if struck by the sun’s rays “to English fiction,” Rateliff writes, so his readers could not possibly have known.

Yet I knew. Perhaps not the first time I heard The Hobbit read to me, at the age of four, but at least by the time I read it to my own son when he was four in 1993. For by then I had been to Iceland several times.

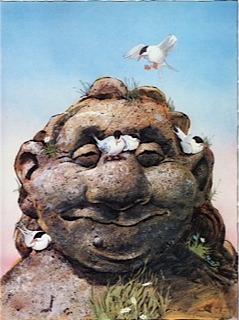

And in Iceland you can hardly take a hike without meeting a troll—often with birds perched on them, as in the beautiful picture book by Guðrun Helgadóttir and Brian Pilkington, Flumbra: An Icelandic Folktale (Iðunn 1981; though they call Flumbra a giant, not a troll). Here is one of Pilkington’s illustrations:

The summer my family lived at the abandoned farm of Litla Hraun on the west coast of Iceland—a summer described in my book A Good Horse Has No Color, as well as in my husband’s Summer at Little Lava (FSG 1998)—we looked out our window every day at the story of a troll.

One night, an amorous trollwoman decided to visit her lover on the western end of the Snaefellsnes peninsula. She took her horse, and a bucket of skýr (a kind of Icelandic yogurt) as a gift. She and her lover sported all night and she got a late start going home. About the middle of the peninsula, she dropped the empty bucket to ride faster. A little further on, her horse foundered and she abandoned him, running as hard as she could for home. The sun caught her at the mountain pass now named for her, Kerlingarskarð, and turned her to stone. Or at least that’s how our neighbor, the farmer at Snorrastaðir, told us the story.

Out my window, I could easily pick out the mountain peaks called Skýr Bucket and Horse. (You can see the back of the Horse just above the crater of Eldborg in this photo.) Crossing (on the old road) north to the town of Stykkishólmur, I would crane my head out the car window to say hello to the old trollwoman, the Kerling.

On a later visit to Skagafjörður, I learned the story of the blocky island Drangey that dominates the fjord. A troll and his wife had a cow in heat, but their cowherd was away so they decided themselves to lead her across the fjord to a neighbor’s bull. They misjudged the distance. The rising sun caught them only halfway across the water, and there they remained: the cow as the island itself, Karl as a tall rock stack on the seaward side, and Kerling as a matching stack on the landward side (though one or the other of the trolls, I forget which, has since tumbled down).

Every Icelandic farmer I’ve met knows stories like these of the mountains and islands and rocks near his or her farm. One of my friends jokes that you can’t take a step in Iceland without standing on a story. I agree. And while we know that Tolkien himself never visited Iceland, it seems that Iceland—and its stories—visited him. In the interview in Morgunblaðið, Arndís notes that she was not the first Icelandic au-pairto work for the Tolkiens in Oxford. Aslaug, an Icelandic woman who had gone to school with Arndís, had been there for the previous year and a half and had gotten Arndís the job. Who knows what stories Aslaug might have told. Perhaps the stories of Iceland’s Hidden Folk, who are so much like Tolkien’s elves?

Published on August 01, 2012 11:00

July 25, 2012

A Viking Woman in America

A lot of the fun of being a writer doesn’t make it into the final book. When I was researching The Far Traveler, for example, I visited L’Anse-aux-Meadows, the village in northwestern Newfoundland where in the 1960s Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad discovered the only uncontested archaeological proof that Vikings visited America around the year 1000.

A lot of the fun of being a writer doesn’t make it into the final book. When I was researching The Far Traveler, for example, I visited L’Anse-aux-Meadows, the village in northwestern Newfoundland where in the 1960s Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad discovered the only uncontested archaeological proof that Vikings visited America around the year 1000.As Clayton Colbourne, a Parks Canada guide with a ginger beard and a happy tongue told me, a local farmer named George Decker took the Ingstads around to see what he called the Indian mounds.

“We used to play on those mounds as kids,” Colbourne said. “There were eleven kids in my family. We had cows, horses, about ten sheep. My grandmother used to spin her own wool. My mother sent it out for spinning, but she knitted all night. Mittens for eleven kids, you know. There was no TV.” Colbourne digressed a little further to describe the thrill of skating on black ice—sea ice just one night thick—and how he still, at middle-age, will feed his “lust for risk” by running his snowmobile out onto the ice (in the local accent, the word comes out “hice”) before it’s safe. Sank it in the bog last year, as a matter of fact.

There are no cows or horses or sheep in this remote corner of Newfoundland now, Colbourne confirmed. No farms at all; only one place that sells a few turnips. Since the road went through to bring tourists to the Viking site, he and the rest of the forty or fifty year-round residents have relied on trucked-in food paid for by their Parks Canada jobs and the summertime profits from restaurants and guest houses. After it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978, they even learned to pronounce their birthplace more properly: “Lance-O-Meadows” instead of “Lancy Meadows.”

“George Decker,” Colbourne said, resuming the subject at hand, “used to make hay on those mounds. He staked it out—that means, he used it but he didn’t own it. He picked that place because the grass was so tall.”

The Spindle WhorlThe artifact found at L’Anse-aux-Meadows that speaks most eloquently to me is a spindle whorl—proof that a Viking woman was on the expedition, for yarn-spinning was women’s work in Viking culture. Birgitta Wallace, who began working with the Ingstads in the late 1960s and took charge of the dig in 1975, told me how it was found.

“There was this young American boy, Tony Birdsley—he’s now a lawyer. His father was in charge of a big factory in Corner Brook and was very active in the Early Sites organization. He got the Newfoundland premier interested in L’Anse aux Meadows. So anyway, Tony was working for us and he was finding one stone after another.

“‘Birgitta,’ he would say, ‘is this anything?’“‘No, Tony, it’s nothing.’“‘Is this anything?’“‘No, it’s nothing.’ “We did this over and over. Then he showed me the spindle whorl. I said, ‘Anne Stine! Come and look!’ And we hopped and danced all around, Anne Stine in her yellow rubber pants and me in my white rubber pants, and Tony called over to Junius Bird”—a distinguished anthropologist from the American Museum of Natural History—“and said, ‘What did I find? They’re all going crazy.’

“It had been a horrible, miserable day,” Birgitta said, “cold and wet, one of those days when you work from teacup to teacup. I had brought a bottle of champagne in my backpack, and you can bet it was cracked open that night!”

A Pile of RubbleI had arranged a month before to meet Birgitta at L’Anse-aux-Meadows during one of her periodic trips to consult with the staff and Viking reenactors there. We were to rendezvous at the visitors’ center, but as I toured the largest of the reconstructed houses—aspacious and sensible structure, with four rooms in a line—I came upon her in a far corner, deep in a discussion with Loretta Decker, the park supervisor, about changing the smoke holes in the roof to make them more historically accurate.

As we walked outside to see the actual ruins, Birgitta explained that she has spent many years reanalyzing Anne Stine’s work. “I’ve looked at all the photos, plans, and drawings—and I took notes at the time. I have gone back to the find bags and the earliest reports. They tend to be the most correct.”

The walls the Ingstads mapped are now outlined by low grassy ridges interrupted by door openings, so that tourists can walk into and through the original houses without destroying the last traces of them. Birgitta darted from one wall to another, pointing with a sneakered foot at the mistakes: “This room had a very clear door out to the west, toward the bog.” No such entrance is cut in the ridge. “That pit is not supposed to be here. And this is a wing—there’s a wall over there.” I see no sign of it. The house outlines had been made before Birgitta’s reanalysis.

She stopped beside the lower doorway of the largest house. “That’s where the spindle whorl was found,” she pointed outside, adding that the Viking woman had probably dropped her spindle somewhere inside the room, for the whorl had been found in a pile of recent rubble. “Loretta’s father and his father, George Decker, thought there was treasure in this mound,” Birgitta said. “When they were digging, they took the soil from inside the house, and threw it out there.”

Clayton Colbourne at the park office had told me a more politically correct version of the same story: rather than treasure hunting, George and his son were digging a post hole for a fence. The Viking spindle whorl—true treasure, if only they had known it—was turned up, unnoticed, by their shovels and promptly reburied.

You can read more about the L’Anse Aux Meadows historical site at the website Canadian Mysteries,http://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/vinland/home/indexen.html

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on July 25, 2012 08:19

July 18, 2012

Bilbo’s Ride through Iceland

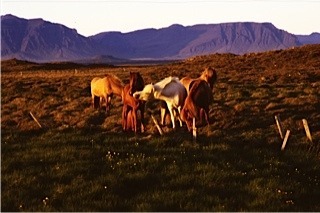

The first time I flew to Iceland, in 1986, I felt immediately at home. It was a strange feeling. I’d grown up in deep oak woods—Iceland had few trees taller than my head. There was no ocean near my home in Pennsylvania, no black beach, no wailing wind or horizontal rain, no tumbling waterfalls, no lava fields, no gleaming glaciers, no jewel-green fields alive with herds of horses. But in Iceland that first time, I felt I’d been there before. The landscape seemed insistently familiar.

The first time I flew to Iceland, in 1986, I felt immediately at home. It was a strange feeling. I’d grown up in deep oak woods—Iceland had few trees taller than my head. There was no ocean near my home in Pennsylvania, no black beach, no wailing wind or horizontal rain, no tumbling waterfalls, no lava fields, no gleaming glaciers, no jewel-green fields alive with herds of horses. But in Iceland that first time, I felt I’d been there before. The landscape seemed insistently familiar.Friends told me of having had the same feeling. Had we lived there in a previous life, I wondered? Did we have Viking blood?

It puzzled me for years, until I read a brilliant scholarly book by Marjorie Burns called Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien’s Middle-earth, published by the University of Toronto Press in 2005. In it Burns argues that the landscape of JRR Tolkien’s Middle-earth (except for the very-English Shire) was essentially Icelandic.

I had “traveled” to Iceland numerous times before 1986, unknowingly, while reading and rereading Tolkien’s books. Through college Tolkien had been my favorite author (in spite of the scorn such a confession brought down on an English major at an American university in the late 1970s, where fantasy was derided as “escapist” and unworthy of study). From his biography, I knew Tolkien had begun reading Old Icelandic in his teens. He loved the cold, crisp, unsentimental language of the Icelandic sagas, their bare, straightforward tone like wind keening over ice. He was drawn to the “Northernness” of the Eddas: To their depictions of dragons and dwarves, fair elves and werewolves, wandering wizards, and trolls that turned into stone. To their portrayal of men with a bitter courage who stood fast on the side of right and good even when there was no hope at all.

I had “traveled” to Iceland numerous times before 1986, unknowingly, while reading and rereading Tolkien’s books. Through college Tolkien had been my favorite author (in spite of the scorn such a confession brought down on an English major at an American university in the late 1970s, where fantasy was derided as “escapist” and unworthy of study). From his biography, I knew Tolkien had begun reading Old Icelandic in his teens. He loved the cold, crisp, unsentimental language of the Icelandic sagas, their bare, straightforward tone like wind keening over ice. He was drawn to the “Northernness” of the Eddas: To their depictions of dragons and dwarves, fair elves and werewolves, wandering wizards, and trolls that turned into stone. To their portrayal of men with a bitter courage who stood fast on the side of right and good even when there was no hope at all.Reading the sagas and Eddas was more important than reading Shakespeare, Tolkien argued, because the Icelandic books were more central to our language and our modern world. Egg, ugly, ill, smile, knife, fluke, fellow, husband, birth, death, take, mistake, lost, skulk, ransack, brag, and law, among many other common English words, all derived from Old Norse. In Tolkien’s lifetime (though not by him), Snorri Sturluson’s Edda was described as “the deep and ancient wellspring of Western culture.”

But I also knew that Tolkien had never visited Iceland.

Marjorie Burns solved the riddle by showing how deeply Tolkien had been influenced by his reading of William Morris’s Journals of Travel in Iceland, 1871-73.

Marjorie Burns solved the riddle by showing how deeply Tolkien had been influenced by his reading of William Morris’s Journals of Travel in Iceland, 1871-73.The hobbit Bilbo Baggins’s ride to “the last homely house” of Rivendell, for example, matches one of William Morris’s excursions from the 1870s point-for-point. Both riders are fat, timid, tired, and missing the small comforts of home. Each sets out on a charming pony ride that turns dreary, wet, and miserable. The wind is cold and biting. The landscape is “doleful,” black, rocky, with “slashes of grass-green and moss-green,” Tolkien writes. Chasms open beneath their feet. Bogs and waterfalls abound. The pony stumbles, the baggage (mostly food) is lost, the fire refuses to light. The rider nods off on the last leg and is astonished: There was “no indication of this terrible gorge till one was quite on the edge of it,” Morris writes. Narrow, it lay between steep cliffs cut by a deep green river. “We rode down at right angles into the main gorge, with a stream thundering down it; we rode round the very verge of it amidst a cloud of spray from the waterfall.” Finally the gorge debouched into a green valley with—not the elves’ Rivendell—but a handsome Icelandic farmstead. “A sweet sight it was to us: we rode swiftly down,” Morris writes, and soon were happily “out of the wind and rain in the clean parlor, drinking coffee and brandy, and began to feel that we had feet and hands again.”

I’ve ridden that ride (though not the exact route: that’s a plan for the future). But the rain, the cold, the biting wind, the peckishness, the fatigue, the astonishment at the landscape, the deep gratitude for the Icelanders’ warm hospitality, the thrill of feeling at the end of the ride “that we had feet and hands again”—all these are very familiar. All these make Iceland feel like home.

I’ve ridden that ride (though not the exact route: that’s a plan for the future). But the rain, the cold, the biting wind, the peckishness, the fatigue, the astonishment at the landscape, the deep gratitude for the Icelanders’ warm hospitality, the thrill of feeling at the end of the ride “that we had feet and hands again”—all these are very familiar. All these make Iceland feel like home.This essay was adapted from my book-in-progress, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, due out in October from Palgrave Macmillan.

Published on July 18, 2012 07:23

July 11, 2012

Saga House

Where do writers get their ideas? Out of the blue. Here’s an example. From 1981 to 2002 I worked as a science writer at Penn State University. At the same time, I indulged my interest in medieval Iceland and its sagas by visiting the country every other year. Imagine my delight when a Penn State anthropology professor called one day to tell me about his research project in Iceland. It was the seed of my book The Far Traveler. Here, reprinted by permission, is my original report from January 2003 in the magazine Research/Penn State:

Where do writers get their ideas? Out of the blue. Here’s an example. From 1981 to 2002 I worked as a science writer at Penn State University. At the same time, I indulged my interest in medieval Iceland and its sagas by visiting the country every other year. Imagine my delight when a Penn State anthropology professor called one day to tell me about his research project in Iceland. It was the seed of my book The Far Traveler. Here, reprinted by permission, is my original report from January 2003 in the magazine Research/Penn State:Around the year 1000, a woman named Gudrid sailed west from Greenland. She spent three winters in a land called Vinland, then sailed east to Iceland. Since the 1960s, archeologists have linked Gudrid’s home in the New World with the Viking ruins at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland.Now [in 2002] a team working in Iceland believe they’ve found the longhouse Gudrid lived in when she returned from America.“That’s not what archeology is about,” says Paul Durrenberger, a Penn State anthropologist who was part of the team. “It’s not about finding somebody’s house.“But,” he concedes, “we probably can name the people at some of these farms some of the time.”The point of the project was to determine the power of an Icelandic chieftain. John Steinberg of UCLA [now at the University of Massachusetts-Boston] had studied bronze and iron-age chieftains in Denmark, trying to expand upon Timothy Earle’s findings with the Inca in Peru. Earle, who teaches at Northwestern, wrote the 1997 book, How Chiefs Come to Power: The Political Economy in Prehistory. In Iceland, Steinberg thought he might find out how chiefs lose power, how they are replaced by the centralized state, a process that Iceland’s sagas record as happening in 1262. Durrenberger was invited to join the project due to his 1992 book, The Dynamics of Medieval Iceland: Political Economy and Literature.Using archeology to study a political system requires large-scale surveys of an area, not detailed excavation of one house. Yet these surveying techniques were developed in hot, dry climates where much of a culture’s record is visible on the land’s surface. “In Iceland, you can’t see anything on the surface,” Durrenberger notes.

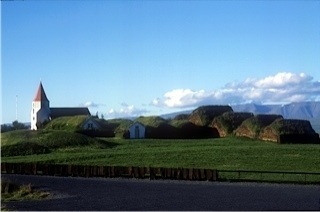

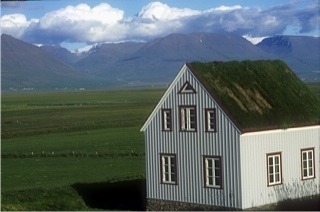

The museum complex at Glaumbaer.The Icelandic landscape is stark: black heaps of lava, high mountains streaked with snow, rivers blue with glacial till, hayfields green as jewels. The wind is never still. With no wood or building stone, the first settlers built houses of turf, like the sod homes of prairie pioneers. Some were lived in, patched and expanded, until the present age: The site of Gudrid’s farm is now a historical park, with a turf house open to tourists.To see beneath the soil, Steinberg’s team used a remote sensing tool that measures electrical resistance. “It’s a tube 6 inches around and longer than 6 feet, quite heavy, that you carry on a strap on your shoulder,” Durrenberger explains. “The front end sends a signal down into the earth, and the back end picks it up. What you get, if you’re walking across the valley, is a series of squiggles. Brian Damiata, the geophysicist, puzzles over it, like somebody reading auguries in bird guts. If you stare at it long enough, you begin to see what he’s talking about. Turf walls do not convey electricity the way soil does.”Combining this remote sensing tool with GPS (Global Positioning System) data, the team could map all the old houses in the valley, measure their sizes, and determine when they were occupied.Iceland is good for dating such finds because of its history of volcanic eruptions. “You can date things by the tephra layers,” Durrenberger explains. “Coming down from the top, there’s a 1300 layer — black, gritty ash from an eruption in the year 1300. Then there’s soil, then the 1104 layer — very distinctive, shiny white. Then more soil, then the 1000 layer, a sort of grayish black tephra. Below that is the Landnam — the Settlement — a greenish black, gritty tephra.A house dated before the Landnam layer had not been occupied long; Iceland had no native inhabitants before the Vikings arrived in 870. “So you should be able to see the shift from chieftain to state. It starts with longhouses, chieftain’s houses — they brought that idea on the boats with them. Then it moves to a dispersed pattern: a big house with a bunch of smaller houses around it, what Steinberg calls the Manor.” The Manor plan marks when the idea of property rights took hold in Iceland.Once the walls were found and dated, the archeologists screened the dirt to find bones and plant remains, by which they could reconstruct the inhabitants’ diets and the climate. But it was the depth of the soil that told of a chieftain’s power: the mainstay of the economy was grass for raising sheep. “If you control that, you have a strong household.”They were calculating the depth of soil in a hayfield when they found what might be Gudrid’s house.

The museum complex at Glaumbaer.The Icelandic landscape is stark: black heaps of lava, high mountains streaked with snow, rivers blue with glacial till, hayfields green as jewels. The wind is never still. With no wood or building stone, the first settlers built houses of turf, like the sod homes of prairie pioneers. Some were lived in, patched and expanded, until the present age: The site of Gudrid’s farm is now a historical park, with a turf house open to tourists.To see beneath the soil, Steinberg’s team used a remote sensing tool that measures electrical resistance. “It’s a tube 6 inches around and longer than 6 feet, quite heavy, that you carry on a strap on your shoulder,” Durrenberger explains. “The front end sends a signal down into the earth, and the back end picks it up. What you get, if you’re walking across the valley, is a series of squiggles. Brian Damiata, the geophysicist, puzzles over it, like somebody reading auguries in bird guts. If you stare at it long enough, you begin to see what he’s talking about. Turf walls do not convey electricity the way soil does.”Combining this remote sensing tool with GPS (Global Positioning System) data, the team could map all the old houses in the valley, measure their sizes, and determine when they were occupied.Iceland is good for dating such finds because of its history of volcanic eruptions. “You can date things by the tephra layers,” Durrenberger explains. “Coming down from the top, there’s a 1300 layer — black, gritty ash from an eruption in the year 1300. Then there’s soil, then the 1104 layer — very distinctive, shiny white. Then more soil, then the 1000 layer, a sort of grayish black tephra. Below that is the Landnam — the Settlement — a greenish black, gritty tephra.A house dated before the Landnam layer had not been occupied long; Iceland had no native inhabitants before the Vikings arrived in 870. “So you should be able to see the shift from chieftain to state. It starts with longhouses, chieftain’s houses — they brought that idea on the boats with them. Then it moves to a dispersed pattern: a big house with a bunch of smaller houses around it, what Steinberg calls the Manor.” The Manor plan marks when the idea of property rights took hold in Iceland.Once the walls were found and dated, the archeologists screened the dirt to find bones and plant remains, by which they could reconstruct the inhabitants’ diets and the climate. But it was the depth of the soil that told of a chieftain’s power: the mainstay of the economy was grass for raising sheep. “If you control that, you have a strong household.”They were calculating the depth of soil in a hayfield when they found what might be Gudrid’s house.

The saga-age house was found in the flat hayfield

The saga-age house was found in the flat hayfield in front of the museum office.They had dug holes to gauge the extent of the house when Gudmundur Olafsson, head of archeology at Iceland’s National Museum, visited and convinced the team to extend the excavation, uncovering a long wall with two smaller turf walls at right angles to it. Soon “it became quite clear,” Durrenberger says, what they had found.“Here we have a longhouse with internal turf walls. Longhouses like this one are never found in Iceland, but they are at L’Anse aux Meadows. And we know this house was built later than that one. So how does this house connect to L’Anse aux Meadows?” He laughs. “The only thing to do now is to excavate further.”Paul Durrenberger, Ph.D., is professor of anthropology in the College of the Liberal Arts, 318 Carpenter Bldg., University Park, PA 16802; 814-863-2694; epd2@psu.edu . This work was funded by the National Science Foundation.John Steinberg’s Skagafjordur Archaeological Settlement Survey is still in progress. See their blog at http://blogs.umb.edu/sass .

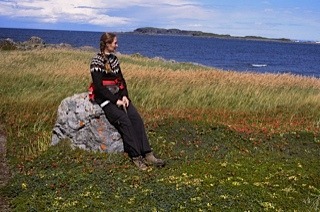

Steinberg (center) and crew (I'm the one in the Icelandic sweater).In 2005 I joined Steinberg and Durrenberger as a volunteer, helping to uncover the tops of the walls of Gudrid’s house; you can read about that experience in The Far Traveler and in the series of posts I did for the Research/Penn State blog, "Secrets of Ancient Iceland." I've borrowed Rita Shepherd's photo (above) from that site.Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Steinberg (center) and crew (I'm the one in the Icelandic sweater).In 2005 I joined Steinberg and Durrenberger as a volunteer, helping to uncover the tops of the walls of Gudrid’s house; you can read about that experience in The Far Traveler and in the series of posts I did for the Research/Penn State blog, "Secrets of Ancient Iceland." I've borrowed Rita Shepherd's photo (above) from that site.Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on July 11, 2012 08:49

July 4, 2012

Iceland's Passion for Liberty

Thingvellir, where Iceland's medieval parliament met.

Thingvellir, where Iceland's medieval parliament met.Where does our concept of liberty come from? Scholars in the 1700s traced it to medieval Iceland.

Iceland was an anomaly in the Middle Ages. It bowed to no king.

The first settlers, coming to this cold and windy island outpost in the late 800s, had disliked the very idea of a king. Many had fled Norway, having lost their lands in the bloody civil war by which Harald Fair-Hair unified the country, becoming the first king of all Norway in about 885. As king, Harald claimed every farm and forest for himself, reapportioning the land to those who would pay taxes. He gave the Norwegians three choices: swear oaths of loyalty, leave, or face the consequences, which included torture, maiming, and death. Some who left went first to the British Isles, only to be pestered by kings and their oaths and their taxes there too. They sailed to Iceland to be free of such nonsense.

Iceland was settled by Vikings in the 800s.

Iceland was settled by Vikings in the 800s.But after fifty years of anarchy the Icelanders deemed some form of government to be, in fact, necessary, and in 930 a cabal of wealthy men worked out a way to share power. They divided the island into four quarters: North, South, East, and West. In each quarter, three spring assemblies were to be held (four in the larger North Quarter) to discuss local matters and to solve disputes. Each spring assembly would be governed by three chieftains, for a total of thirty-nine. To these posts, they appointed themselves.

The thirty-nine chieftains of Iceland were, in theory, equals, but some grew more powerful than others, for this new system of government was organized, not geographically, but by alliances. Uninhabited when it was discovered in 870, Iceland was home to at least 10,000 people by 930. (By 1262, when Iceland lost its independence, there would be 50,000.) There were no towns on the island, and would not be until the eighteenth century. Instead, Icelanders lived on scattered farms around the periphery of the island, which has at its center a vast, uninhabitable wasteland of volcanoes and glaciers. Some farms were immense, supporting up to a hundred people; others were as small as one nuclear family. Every farmer who owned at least one cow or boat or fishing net for each one of his dependents had to ally himself with a chieftain, paying him taxes, and, if requested, accompanying him to assemblies or fighting in his battles. The farmer could choose which of the thirty-nine chieftains he wanted to support, and he could change his allegiance once a year. But generally only the richer farmers dared annoy the local chieftain by choosing a more distant one.

Usually it paid to support a chieftain who lived close by. He was nearer to hand if the farmer was robbed, or his hay-store ran out in a harsh winter, and travel wasn’t so onerous when the farmer was invited to a Yule feast or summoned for a raid. Yet two chieftains often lived within a day’s ride of each other. In that case, it paid to choose the one who was less easily bullied, for the support of a chieftain was the only protection a family had from a rival clan. Only a chieftain could bring a lawsuit to one of the assemblies, and only a chieftain could answer it.

Thingvellir on a summer day.

Thingvellir on a summer day.In addition to the spring assemblies held in each quarter of the country, once a year, on the tenth Thor’s Day of summer, in the great rift valley of Thingvellir beside its deep blue lake, Iceland’s thirty-nine chieftains and their wives and children and followers gathered for the Althing, the General Assembly of all Iceland. The Althing was a grand party. Thousands of people stayed for two weeks in tents and turf-walled booths on the banks of the Axe River, drinking ale, telling tales, taking part in horse fights and wrestling matches, races and dice games, making wedding plans or finalizing divorces, witnessing court cases, and wrangling over the law.

Disputes between Icelanders of any rank could be settled at the Althing, by appeal to Iceland’s laws. There were five law courts: one for each quarter plus an appeals court, each with thirty-six judges. The judges were chosen by the chieftains, each chieftain being allowed to nominate or to veto a certain number. Presiding was Iceland’s only elected official, the Lawspeaker; he recited one third of the law code at each Althing. The place where he stood, called the Law Rock, was a height of land that formed a natural amphitheatre. The chieftains gathered around the Law Rock and, after the recitation, the laws were debated, adjusted, and agreed upon for, as the sagas say, “With laws shall our land be built up, but with lawlessness laid waste.”

Iceland’s medieval parliament was brought to the attention of the English-speaking world in the mid-1700s by Thomas Percy, bishop of Dromore and friend of Samuel Johnson and James Boswell. Percy translated a long work on the history and lore of the Norse written by Paul-Henri Mallet, the Swiss tutor to the Crown Prince of Denmark and later professor in Copenhagen. Mallet drew heavily from Snorri Sturluson’s Edda and the Poetic Edda, and from Snorri’s history of the Norwegian kings, Heimskringla. He amplified Snorri’s works with other Icelandic sagas and sources such as Tacitus, Saxo Grammaticus, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Adam of Bremen, and Saxon law codes. He writes, “It will appear pretty extraordinary to hear a historian of Denmark cite, for his authorities, the writers of Iceland, a country cut off, as it were, from the rest of the world, and lying almost under the northern pole.” But Iceland’s medieval skalds, he declares, were “famous throughout the north for their songs.”

The white flagpole marks the Law Rock.

The white flagpole marks the Law Rock.In Percy’s translation of Mallet, called Northern Antiquities, English readers found a world not only savage and sublime, but imbued with a passion for liberty. The religion of the Vikings was as “simple and martial as themselves,” Percy wrote. Their form of government was “dictated by good sense and liberty,” while their “restless unconquered spirit,” was “apt to take fire at the very mention of subjection and constraint.”

Or as Joseph Sterling wrote, prefacing his 1782 Icelandic Odes: “To them we are indebted for laying the foundation of that liberty which we now enjoy.”

This essay is excerpted from my book-in-progress, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, due out from Palgrave Macmillan in October 2012. If you'd like me to visit your area on my book tour, please let me know.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on July 04, 2012 07:05

June 27, 2012

The First Icelandic Horse

Icelandic horses are special. (We all say that about our pets.) But few other horse breeds have a thousand-year history.

Skalm is the first Icelandic horse known by name. The Book of Settlements, or Landnámabók, in which she appears, was written in the mid-1100s. It tells the stories of more than 400 people who came to Iceland between 870 and 930 from Scandinavia and the British Isles. Along with Skalm, the book also names the racehorse Fluga and the stallion Eidfaxi, who came from Fluga’s line, and tells of a magic horse that lived in Lake Hjardarvatn. Dozens more horses appear in the Icelandic sagas, written in the 13th century. (In future blog posts, I’ll tell about some of these saga horses.)

Horses play key roles in many of these stories. Like Skalm they were first beasts of burden, carrying everything from coffins to charcoal to haybales to roof beams. Iceland’s landscape, with its high mountains, wide bogs and mires, impassable lava fields, and torrential glacier-fed rivers, made wagons impractical, and roads were not built in many parts of the country until the mid-1900s. A sturdy strong horse, pleasant to ride but able to carry heavy loads over long distances, was the one tool that could open Iceland’s vast empty lands and stitch its scattered settlements into a society.

Newborn foals at Hallkelsstadahlid.

Newborn foals at Hallkelsstadahlid.Skalm’s story begins when an Icelander named Grim went fishing one day around the year 900, taking along his little son, Thorir, tucked into a sealskinn bag tied up under his chin. The boy must have looked like one of the seal people who, like their kinfolk in the fairytales of Ireland and Scotland, can cast off their sealskins and dance on the shore in human form on certain days of the year, for a merman came up to see what what going on. Grim caught him and hauled him into the boat.

Mermen are magic and know the future. According to the Book of Settlements, as translated by Herman Palsson and Paul Edwards, Grimur asked the merman to tell him if he’d be better off in another part of the country.

“ ‘There’s no point in my making prophecies about you,’ said the merman, ‘but that boy in the sealskin bag, he’ll settle and claim land where your mare Skalm lies down under her load.’”

When Grimur drowned on his next fishing trip, his widow Bergdis took the merman’s words to heart, loaded up Skalm (whose name comes from the verb skálma, “to stride with a long pace”) and with her son, now called Seal-Thorir, followed the mare’s path. They traveled “from Grims Isle west across the moor over to Breidafjord,” a distance of some 75 miles, and “Skalm went ahead of them but never lay down.”

Descending Seal-Thorir's red "sand dune."

Descending Seal-Thorir's red "sand dune."When they next set out, after a winter’s rest, they turned south, going around the entire fjord and over a high mountain range until “just as they reached two red-colored sand dunes, Skalm lay down under her load,” having covered about 100 miles. Bergdis and Seal-Thorir claimed the land from one river south to the next, and from the mountains down to the sea. They lived at Western Raudamelur, and Seal-Thorir became a great chieftain.

I learned about the history of Icelandic horses to write A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse, out of print but available as an e-book from Amazon.com and Smashwords.com. In 1998, I published a version of this story in The Icelandic Horse Quarterly, the official magazine of the U.S. Icelandic Horse Congress; shortly afterwards I joined the magazine’s editorial committee. Visit the congress’s website ( www.icelandics.org ) to read a free copy and learn more about Icelandic horses today, or take a virtual ride on my friend Stan Hirson’s video blogs, Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses ( http://www.lifewithhorses.com/ ).

The Book of Settlements, or Landnámabók, was translated by Herman Palsson and Paul Edwards (University of Manitoba, 1972).

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on June 27, 2012 07:44

June 20, 2012

Practical Education

What is college for? I pondered the question a few years back in an essay published by Penn State University in the magazine I then worked for, Research/Penn State:

What is college for? I pondered the question a few years back in an essay published by Penn State University in the magazine I then worked for, Research/Penn State:I studied the Icelandic sagas in graduate school at Penn State because they were compelling. A mix of The Lord of the Rings (Tolkien had been a saga scholar) and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” magical realism a millennium before Garcia Marquez, they were unlike anything I’d ever read.

I had been introduced to them by a professor of folklore, who, though retired, still taught one course. Sam Bayard was an impish man, small, bald, rotund, and hunched like a wise turtle walking upright. He had an impressive nose, which he periodically aroused with snuff taken from one of the half-dozen boxes secreted in his pockets. He would courteously offer me some, smile when I declined, then, snuffling up a liberal pinch, harrumph into a large handkerchief which he subsequently used to brush the dust off his breast. His snuff boxes were antiques, portable works of art carved of horn, cast in silver or brass with ancient scenes of hunts or warfare, shaped of handsome woods. Another pocket held a tin whistle, which he’d occasionally demonstrate. A fiddle hid in his filing cabinet. A narrow bookshelf along one wall was crammed with Icelandic sagas, which he loaned me, one after the next.

I indulged. I read them in English first, then in the original Old Norse. The professor who taught me the language, Ernst Ebbinghaus, was an icon of his occupation -- high forehead, aquiline nose, a halo of silky white hair. I translated bits of sagas into my notebooks, puzzling over the three genders and four cases, singular and plural, into which the grammar slotted the words, memorizing the twenty-four different forms of such essentials as “the” or “this” or “who.” Ebbinghaus stood at the lectern and explicated such words as ójafnaðrmaðr: the unjust, overbearing man, the man who upsets the balance of the world.

I gave up the sagas to be practical. Deciding whether to go on from a master’s degree in 1985, I, like any sensible graduate student, looked at the job market. Opportunities for a medievalist with a speciality in Icelandic sagas were zilch. A friend with a stellar resume -- Ivy League Ph.D., Fulbright fellowship, National Endowment for the Humanities grant, papers published, book in progress, experience teaching abroad -- got no job offers. Others with theses in Old Norse were teaching Old English (a related language) or history or English composition instead.

I already had a job as a science writer, working at Research/Penn State, a magazine published by Penn State University. I decided to forget an academic career.

But before I packed my books in boxes, my husband and I took a trip to Iceland. We rode the bus to a small fishing village on the west coast. We shouldered our backpacks and hiked four miles out to Helgafell, an egg-shaped hill that marked the ancestral holdings of the saga chieftain Snorri Godi, who died in 1031. His farm at Helgafell was still a working farm: sheep, cows, horses, a barking dog. I knocked on one door of the low modern duplex. The old man who answered, dressed formally in coat and tie, could not make out my attempts at Icelandic. He called his son out of the milk house.

“Snorri Goði -- Búa hér?” I asked. “Living here?”

The son, a lanky man in his early forties, in orange coveralls and a stocking cap, beamed. “Já, já, já, já, já,” he exclaimed, in the Icelander’s long-repeated yes. Snorri Godi had indeed lived here -- a thousand years ago, he said. He took off his cap and shook our hands.

He led us around to his half of the house and, as his wife and five children and her old crippled mother all gathered around the too-small table, and the coffee and cakes and cheeses and cucumbers appeared and then disappeared, he began to tell stories from the sagas.

One night a shepherd saw the whole north face of Helgafell swing open like doors. The god Thor was holding a feast inside the hill.

He would look at me and nod, and I would nod back as if to say, “Yes, that’s how I learned it.” My Icelandic was so poor I understood only a tenth of what he was saying, yet it was enough to recognize the tale.

It was queer to be sharing tales a thousand years old, an American tourist and an Icelandic farmer, as if I and a neighbor in central Pennsylvania had discussed over coffee the mere-hall scene in Beowulfor the Old English riddles of the Exeter Book. Queer and delightful -- and why I’ve gone back to Iceland again and again since that first time in 1986.

I’ve shared sagas with many Icelanders. My Icelandic has improved to the extent that in 1997 I spent a month among Icelandic horsebreeders, and bought two horses, all the while speaking only a few words of English. The experience became my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse. The horses themselves, Icelandic horses, have been my entree into a whole new world.

I am still a science writer. But my life has been enriched by that compelling, impractical graduate education in a medieval literature still current in one small corner of the world. As British writer W. H. Auden (another Icelandophile) once told a newspaper, “This memory is background for everything I do. Iceland is the sun which colours the mountains without being there.” For me, my graduate education is the sun, the background for everything I do.

I had thought about it once as a way to earn a living. It turned out to be a way to make a life.

Since writing this essay, I have written two more books about Iceland: The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman came out in 2007 and Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths will appear in October 2012. I took the photos shown here at Helgafell in 1986, 2009, and 2011. Many thanks to Hjörtur Hinriksson and his children and grandchildren for being my dear friends. If you visit Stykkisholmur, Iceland, be sure to buy a hotdog from the hotdog cart run by Óskar, Hjörtur's son.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on June 20, 2012 06:08

June 13, 2012

The Greening of Iceland

This week at an American Geophysical Union conference in Iceland, my friend Anna Maria Agustsdottir gave a talk on the importance of planting trees in Iceland to repair the damage caused by volcanic eruptions. (See news coverage here.) It’s a project she and her husband, Magnus Johannsson, have been working on for a long time at Iceland’s Landgræðslan ríkisins, or Soil Conservation Service. In 2000, I went out in the field with Anna and Magnus, in the shadow of the volcano Hekla, to report on their work for the alumni magazine of Penn State University.

This week at an American Geophysical Union conference in Iceland, my friend Anna Maria Agustsdottir gave a talk on the importance of planting trees in Iceland to repair the damage caused by volcanic eruptions. (See news coverage here.) It’s a project she and her husband, Magnus Johannsson, have been working on for a long time at Iceland’s Landgræðslan ríkisins, or Soil Conservation Service. In 2000, I went out in the field with Anna and Magnus, in the shadow of the volcano Hekla, to report on their work for the alumni magazine of Penn State University.

Here’s an excerpt from that story: Comparing it to the AGU report, you can see that Anna and Magnus and their colleagues have accomplished a lot in ten years.

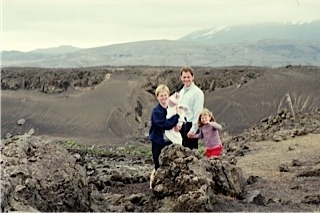

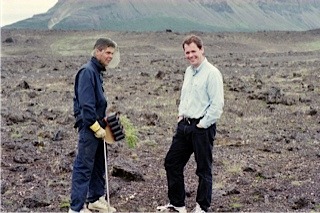

After an hour of bouncing us down a dusty road in his high-powered SUV, Magnus swerves over the berm and inches across the lava plain, over black sand and large rocks blasted there by the volcano Hekla, that snow-capped eminence over our left shoulders that people in the Middle Ages knew as the Mouth of Hell. I’m taking the grand tour of the research plots of Iceland’s Soil Conservation Service with Magnus, his wife Anna, and their children, five-year-old Sara and infant Snorri. The same tour, Magnus says, that he gave to Deng Xiao-Ping’s granddaughter the week before. For his Ph.D. at Penn State, Magnus spent his summers growing zucchini and testing the viability of its seeds. Anna’s dissertation was on volcanoes. Back home in Iceland, they have a much harder row to hoe: growing grass—or anything—to stop the blowing sand.

There’s nothing for miles here, it seems, but black sand and snowy peaks. Volcanoes erupt frequently. An earthquake registering 6.5 on the Richter scale struck the week before I came. According to Kristin Vogfjord, another Penn State alumna and the earthquake specialist at Iceland’s National Weather Service, the epicenter of the quake was just where Magnus is trying to grow grass. His fields lie atop a major fault, where two tectonic plates beneath the continents are pulling apart. On an average day, the area is shaken by 20 to 30 tiny quakes; today there are 3,000. One of Kristin’s colleagues, monitoring the fault, registers the movements each night. Said Kristin, “It’s almost as if you can see the tectonic plates moving in her data.” The earthquakes are often precursors to eruptions. In the last 20 years, Mount Hekla has erupted three times, coating the ground each time with six inches or more of rubbly, sandy black pumice.

Yet Magnus is undeterred. “We’re fixing the land,” he exclaims, waving a hand out the car window.

Far in the distance I see specks of color against the vast expanse of gray. It’s a small cadre of workers, among them Magnus’s 16-year-old brother. As we park and walk toward them, I begin to laugh. Each of the teens has a flat of lupine seedlings, spindly plants about four inches tall. Each also has a potato planter: like a coffee can on a stick. They’re spending the summer trudging back and forth across the black sand plain, six steps, plant a lupine, six steps, plant a lupine. Today the midges are thick. The teens wear face nets, but Magnus and I are fanning our hands like crazy. The kids and Anna have stayed in the car. Six steps, plant a lupine. It’s like the summer job from hell.

Magnus sees the humor, but he’s still miffed that I’m laughing. “In a reclamation project you want your lupine,” he insists. A spire of blue or purple or rose-colored flowers, lupine is a legume; it takes nitrogen out of the air and fixes it in the soil, making its own fertilizer. “We’re creating dunes by planting melgresi—Icelandic lyme grass—perpendicular to the direction of the drifting sand,” Magnus continues, “but we need to use fertilizer year after year for three years to get it to grow. Legumes are the answer to this. We’ve tried native Icelandic species such as white clover or sea pea, but they’re not as vigorous as lupine.”

We drive a little closer to the volcano, and now, indeed, I see that the peculiar Icelandic persistence is paying off: The sands have taken on a tinge of green. They were sown and fertilized four months before Hekla erupted last February [2000], and now the grass shoots are poking up through the new lava and ash. “Ashfall is not a problem in heavily vegetated areas,” Magnus says, “but here we get pumice blowing and drifting like snow. That’s quite a different matter.” Only the native lyme grass and a new Alaskan import, Bering hair grass, can stand having sand blown over them. “They just push up through it.”

When the first Viking settlers arrived in Iceland in 874, the medieval Icelandic sagas say, the land was green “from the mountains to the sea.” Birch woodlands blanketed at least 25 percent of the country; they now cover only 1 percent. Sites of old farmsteads, once grassy and full of sheep, are now black sand deserts. Nearly 40 percent of the country is threatened by desertification. The cause of the problem, Magnus says, is a mix of volcanic action, wind, weather, and human activity.

Icelanders can’t control the first three, so they’re working on the fourth: reducing the grazing herds and planting trees. As one Soil Conservation Service brochure puts it, “The Icelanders still owe their country more than half of the original vegetation cover.”

I like the way they put that: Icelanders owe their country. It’s a lesson other nations need to learn as well. From South Africa to northern China, desertification directly affects some 250 million people, almost four percent of the world population, according to a news release from the United Nations Environment Program last June [2000]. The Icelanders’ experiment could set an example around the world.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on June 13, 2012 08:13

June 1, 2012

The Most Influential Writer of the Middle Ages

Who influenced your favorite writers?

Who influenced your favorite writers?As Laura Miller reported in Salon recently, a group of mathematicians led by Daniel Rockmore of Dartmouth College analyzed the works of 537 authors who wrote in English from 1550 to the present. The mathematicans concluded that “today’s literary writers have little use for the classics,” in Miller’s wording. She continues, “They are, the study asserts, much more influenced by their peers than they are by the most revered authors of earlier centuries.”

The Dartmouth study focused on style--word usage--and I won’t disagree that no one these days writes quite like Shakespeare, Donne, or Milton. But look back farther than 1550 and you'll start to see more similarities.

Take Snorri Sturluson. A few years ago, when I began writing my biography of Snorri, Song of the Vikings (due out in October), I read Neil Gaiman’s best-selling genre-bender American Gods (published in 2001). I was delighted to see how heavily Gaiman was influenced by Snorri Sturluson, in both style and content.

American Gods won the Hugo and Nebula awards, was the first “One Book One Twitter” title in 2010, and is being made into an HBO television series. But put aside the fact that it’s a great story. What intrigued me is that American Gods essentially updates Snorri’s masterwork, the Edda, for both Gaiman and Snorri ask, What do we lose when the old gods are forgotten?

American Gods won the Hugo and Nebula awards, was the first “One Book One Twitter” title in 2010, and is being made into an HBO television series. But put aside the fact that it’s a great story. What intrigued me is that American Gods essentially updates Snorri’s masterwork, the Edda, for both Gaiman and Snorri ask, What do we lose when the old gods are forgotten? Gaiman’s Mr. Wednesday is closely patterned on Snorri’s Odin One-Eye, the god of Wednesday. In this passage from American Gods, Mr. Wednesday reveals himself—by paraphrasing Snorri: “His right eye glittered and flashed, his left eye was dull. He wore a cloak with a deep monklike cowl, and his face stared out from the shadows. ‘I told you I would tell you my names. This is what they call me. I am Glad-of-War, Grim, Raider, and Third. I am One-Eyed. I am called Highest, and True-Guesser. I am Grimnir, and I am the Hooded One. I am All-Father, and I am Gondir Wand-Bearer. I have as many names as there are winds, as many titles as there are ways to die.’”

Mourned Snorri in his Edda, “But these things have now to be told to young poets.” They have forgotten the names of Odin. The old lore is dwindling and will soon vanish into neverwhere: “But these stories are not to be consigned to oblivion,” he insisted.

And because of the books he wrote, they were not.

More than eight hundred years after his death, Snorri’s books are the basis of a best-selling American novel and a TV series. And Neil Gaiman is not the only author Snorri influenced.

Wellspring of Western CultureSnorri Sturluson died, accused of treason by the king of Norway and murdered by thugs, in 1241. His books over time were forgotten, though manuscripts of them were preserved in Iceland and Norway.

Wellspring of Western CultureSnorri Sturluson died, accused of treason by the king of Norway and murdered by thugs, in 1241. His books over time were forgotten, though manuscripts of them were preserved in Iceland and Norway. Then in the early 1600s Snorri was resurrected. Translations from Old Norse began to appear throughout Europe. The craze led to the Gothic novel and ultimately to modern heroic fantasy.

Snorri has influenced writers as various as Thomas Gray, William Blake, Sir Walter Scott, the Brothers Grimm, Thomas Carlyle, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, Richard Wagner, Matthew Arnold, Henrik Ibsen, William Morris, Thomas Hardy, Hugh MacDiarmid, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jorge Luis Borges, W.H. Auden, Gunther Grass, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, A.S. Byatt, Seamus Heaney, Jane Smiley, Michael Chabon, and Neil Gaiman.

Through Tolkien, Snorri has inspired dozens of writers of fantasy. Fantasy and science fiction now account for ten percent of books published, and few books on the fantasy shelves of modern libraries or bookstores are free of wandering wizards, fair elves and werewolves, valkyrie-like women, magic swords and talismans, talking dragons and dwarf smiths, heroes that understand the speech of birds, or trolls that turn into stone—all drawn from Snorri’s Edda and Heimskringla.

Through Tolkien, Snorri has inspired dozens of writers of fantasy. Fantasy and science fiction now account for ten percent of books published, and few books on the fantasy shelves of modern libraries or bookstores are free of wandering wizards, fair elves and werewolves, valkyrie-like women, magic swords and talismans, talking dragons and dwarf smiths, heroes that understand the speech of birds, or trolls that turn into stone—all drawn from Snorri’s Edda and Heimskringla. An incomplete list of fantasy writers indebted to Snorri includes: Douglas Adams, Lloyd Alexander, Poul Anderson, Terry Brooks, David Eddings, Lester del Rey, J.V. Jones, Robert Jordan, Guy Gavriel Kay, Stephen King, Ursula K. LeGuin, George R.R. Martin, Anne McCaffrey, and J.K. Rowling.

Snorri has inspired countless comic books—from Marvel’s Thor to the Japanese anime Matantei Loki Ragnarok—and games, including the wildly popular Dungeons and Dragons, World of Warcraft, and Eve Online. The hit movie The Avengers would not exist without Snorri.

Snorri Sturluson is the most influential writer of the Middle Ages. His Edda, according to one translator, is “the deep and ancient wellspring of Western culture.” That comment was published in 1909—how much more true it is today.

Published on June 01, 2012 08:14