Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 17

December 26, 2012

Songs of Iceland

The title of my book, Song of the Vikings, doesn’t refer to music, as I’ve noted previously. It’s more like George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, his overall title for the series that starts with Game of Thrones.

The title of my book, Song of the Vikings, doesn’t refer to music, as I’ve noted previously. It’s more like George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, his overall title for the series that starts with Game of Thrones.But I was fascinated to find, second on this list of “typical Icelandic songs,” one written by a contemporary of Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century Icelandic writer and chieftain whose story Song of the Vikings tells.

“This is what Icelanders listen to when they want to hear the very best Icelandic songs,” writes the listmaker, Benedikt Jóhannesson, on the Iceland Reviewwebsite. “We may sing, dance, or cry, depending on the mood. Listen to the songs and then you will understand Icelandic culture a bit better.”

About his second choice, Benedikt writes: “The next song is a psalm, and the text comes from the 13th century by Kolbeinn Tumason, who is said to have written the psalm the day before he was killed in battle with the bishop of Iceland! The composer, Thorkell Sigurbjörnsson, is best known for his very modernistic compositions. Here the psalm is performed by Eivör, the great Faroe Isles singer, who has resided in Iceland on and off for the last few years. Hördur Áskelsson, organist and conductor, has called this an almost perfect psalm. It is called Heyr himna smiður or ‘Hear me, Maker of Heaven.’”

I found Eivör’s version especially moving (though one of my Icelandic friends pointed out that she sings with a Faroese accent). This is not the kind of song I would have associated with Kolbein Tumason, who makes a brief appearance in Song of the Vikings. Like Snorri, Kolbeinn was quite greedy for wealth and power, yet here he is opening his soul.

Here is another version (in proper Icelandic), with English translation, sung by the Icelandic singer Ellen Kristjánsdóttir:

You can also find the full text and translation here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolbeinn_Tumason

Listen, smith of the heavens,what the poet asks.May softly come unto meyour mercy.…

Drive out, O king of suns,generous and great,every human sorrowfrom the city of the heart….

Here is the story behind the psalm: In 1206, in the north of Iceland, Bishop Gudmund the Good came to court in full episcopal regalia and broke up a lawsuit between the chieftain Kolbein Tumason and a priest who owed him money. It was a little, everyday lawsuit. No one could have predicted the cataclysm it unleashed.

Here is the story behind the psalm: In 1206, in the north of Iceland, Bishop Gudmund the Good came to court in full episcopal regalia and broke up a lawsuit between the chieftain Kolbein Tumason and a priest who owed him money. It was a little, everyday lawsuit. No one could have predicted the cataclysm it unleashed.The bishop “forbade them to pass sentence on the priest,” the saga says. “But they passed sentence on him just the same.”

The priest was outlawed—exiled from Iceland.

The bishop took the outlawed priest into his own household at Holar (which made the bishop an outlaw too), and banned Kolbein from church. When Kolbein protested, Bishop Gudmund formally excommunicated him.

Kolbein was taken aback. He considered himself a pious Christian. He had long been the bishop’s firm supporter. Gudmund was a cousin of Kolbein’s wife and had been chaplain of the family’s church before the chieftain pushed for his election as bishop in 1201. True, his support may not have been entirely selfless. Notes Sturlunga Saga, “Many men commented that Kolbein had wanted Gudmund chosen bishop because he thought he himself would thus control both laymen and clergy in the north.” The writer of a later Life of Gudmund the Good, adds, “As soon as they got to Holar, Kolbein assumed full control both of household affairs and of finances.”

Historians blame Gudmund the Good for much of the strife that enveloped Iceland during the Sturlung Age—strife that would climax with the murder of Snorri Sturluson at the request of the king of Norway in 1241 and result in Iceland becoming a colony of Norway in 1262. When Bishop Gudmund denied the universality of Iceland’s laws, “the fate of Iceland’s independence was ultimately sealed.”

But Gudmund was not thinking about Iceland’s independence. If he thought about anything other than the rights of the Church it was the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket, murdered in Canterbury Cathedral when Gudmund was a stubborn boy of ten. Saint Thomas’s dispute with King Henry II hinged on the punishment of “criminous clerks,” churchmen who committed crimes, just as Gudmund’s dispute with the Icelandic chieftains did. In the Saga of Gudmund the Good, written by one of his pupils, a woman dreams that Gudmund will “rank as high in Iceland as Thomas in England.” A verse by Kolbein himself is quoted: Gudmund, he says, “keeps firm his wish / to wield such power / as Thomas Becket. / This bodes danger.”

But Gudmund was not thinking about Iceland’s independence. If he thought about anything other than the rights of the Church it was the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket, murdered in Canterbury Cathedral when Gudmund was a stubborn boy of ten. Saint Thomas’s dispute with King Henry II hinged on the punishment of “criminous clerks,” churchmen who committed crimes, just as Gudmund’s dispute with the Icelandic chieftains did. In the Saga of Gudmund the Good, written by one of his pupils, a woman dreams that Gudmund will “rank as high in Iceland as Thomas in England.” A verse by Kolbein himself is quoted: Gudmund, he says, “keeps firm his wish / to wield such power / as Thomas Becket. / This bodes danger.” The first time Gudmund insisted that churchmen were above the law—when Kolbein sued the priest who owed him money—Kolbein backed down. The chieftain offered the bishop self-judgment and settled for a fine of twelve cows. He got six. The next time Kolbein sued some clerics (for theft), he said there was no use making an agreement, since the bishop wouldn’t keep it.

A scuffle broke out. Someone threw a stone. It hit Kolbein in the forehead and killed him. God’s will be done.

Listen, smith of the heavens,what the poet asks.May softly come unto meyour mercy.

Parts of this essay were adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on December 26, 2012 09:22

December 19, 2012

Snorri Sturluson’s Reykholt

The Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241) may have written the most influential book of the Middle Ages: His Edda inspired such writers as the Brothers Grimm, Longfellow, Ibsen, William Morris, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jorge Luis Borges, Günter Grass, A.S. Byatt, Jane Smiley, and Neil Gaiman.

The Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241) may have written the most influential book of the Middle Ages: His Edda inspired such writers as the Brothers Grimm, Longfellow, Ibsen, William Morris, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jorge Luis Borges, Günter Grass, A.S. Byatt, Jane Smiley, and Neil Gaiman.But only in the last few years have we begun to get a picture of Snorri’s own life, as I discovered when I began researching his biography for Song of the Vikings.

Since 1987, archaeologists led by Guðrún Sveinbjarnardóttir have been studying the farm of Reykholt in western Iceland, which Snorri took control of when he was 28 and where he was killed at age 63. Their work is summarized in a new book, Reykholt: Archaeological Investigations at a High Status Farm in Western Iceland, published by the National Museum of Iceland.

Snorri’s Reykholt was one of the largest church estates in Iceland, with an enormous income from the tithe. It encompassed extensive lands, including 30 tenant farms, along with grazing rights in the mountains and rights to collect driftwood and beached whales by the sea. Two salmon rivers cut through the estate. In the vast marshlands—nearly 50 percent of the estate was wetlands—ample grass could be cut for the livestock’s winter hay. Nor was there any shortage of turf for building house-walls or peat for firing the smithy. Some barley (for beer) was grown, but Snorri made little effort to manure his fields. He could afford to buy barley if he needed more.

Snorri’s Reykholt was one of the largest church estates in Iceland, with an enormous income from the tithe. It encompassed extensive lands, including 30 tenant farms, along with grazing rights in the mountains and rights to collect driftwood and beached whales by the sea. Two salmon rivers cut through the estate. In the vast marshlands—nearly 50 percent of the estate was wetlands—ample grass could be cut for the livestock’s winter hay. Nor was there any shortage of turf for building house-walls or peat for firing the smithy. Some barley (for beer) was grown, but Snorri made little effort to manure his fields. He could afford to buy barley if he needed more.To the east of Reykholt the soil became thin until it petered out altogether in wasteland under the eye of the glaciers. A main route from the north of Iceland to the assembly plains at Thingvellir ran along the edge of this wasteland, meeting a route to the sea near Reykholt. Trade was thick along both routes—one saga tells of a man who became rich peddling such things as chickens. The archaeologists found that Reykholt imported fish, seal meat, and seaweed, as well as driftwood, from the coast, and lumber, glass, ceramics, and grain from farther away. Artifacts were found from Germany, England, and France, including a gold finger-ring engraved with a Romanesque design.

The estate’s name, “Smoky Wood,” derives from two important natural resources. The hillsides to north and south of the valley were thickly wooded with scrubby birch and willow, useful for making charcoal, though the forests were in decline and wood would become scarcer by the end of the 13th century. As elsewhere in Iceland, the trees never grew tall or straight enough to use in ship-building—the wind saw to that.

The estate’s name, “Smoky Wood,” derives from two important natural resources. The hillsides to north and south of the valley were thickly wooded with scrubby birch and willow, useful for making charcoal, though the forests were in decline and wood would become scarcer by the end of the 13th century. As elsewhere in Iceland, the trees never grew tall or straight enough to use in ship-building—the wind saw to that.“Smoky” referred to the steam from the hotspring on the property, which had long ago been plumbed. Conduits ran downhill to supply warm water for a hot-tub. Mornings, the women would use the hot water for laundry and cooking. Evenings, the men would gather and soak, sorting out the day’s troubles, telling stories, and talking politics.

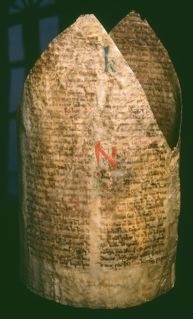

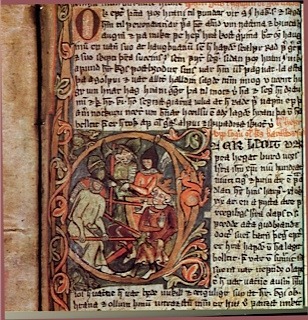

Snorri’s predecessor at Reykholt, the priest Magnus, had taken over this fine estate upon his father’s death in 1185 and “gradually used up all the wealth as he began to grow older.” His agreement to turn the management over to Snorri in 1206 is recorded in the church’s inventory, a single sheet of calfskin which, though tattered and nearly unreadable, still exists; it is the oldest surviving document written in Icelandic. According to Sturlunga Saga, which was written by Snorri’s nephew, “Snorri was a very good businessman.” He restored Reykholt to prosperity and “became a great chieftain, for he was not short of money.”

Snorri’s predecessor at Reykholt, the priest Magnus, had taken over this fine estate upon his father’s death in 1185 and “gradually used up all the wealth as he began to grow older.” His agreement to turn the management over to Snorri in 1206 is recorded in the church’s inventory, a single sheet of calfskin which, though tattered and nearly unreadable, still exists; it is the oldest surviving document written in Icelandic. According to Sturlunga Saga, which was written by Snorri’s nephew, “Snorri was a very good businessman.” He restored Reykholt to prosperity and “became a great chieftain, for he was not short of money.”Twelve years passed. Then Snorri went to Norway, where he received the title of Landed Man (equivalent to Baron) from the king. On his return to Reykholt in 1220, Snorri began a vast building project. Snorri had apparently taken notes in Norway, not just on history and mythology, but on the latest fashions in architecture.

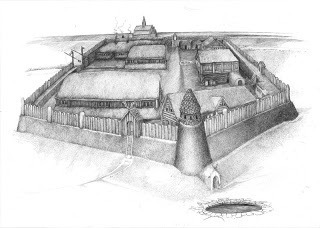

As the archaeologists discovered, Snorri built huge timber houses with stone foundations and wooden floors and paneling. There was a great hall with a turf roof for his henchmen to sleep in, another hall for feasting and entertaining, and a little parlor for a private chat or to use as a writing studio. These rooms were connected to each other by a maze of hallways, but Snorri’s bedroom was a freestanding wooden cottage. Next to it was a two-story house with a small ground floor and an overhanging loft like the townhouses Snorri saw in Bergen. One door opened into the feast hall, another into the parlor, and a third—perhaps a trapdoor—into the fateful cellar where Snorri would be murdered by the king of Norway’s men in 1241.

But that dark night was still some years off. Now Snorri, the richest and most powerful man in Iceland, was busy building a sauna with stone walls and floor. Steam was piped to it from the nearby hotspring via stone-and-clay conduits. Steam pipes may also have run under the floor of the parlor and feasthall, like a Roman hypocaust; the archbishop’s palace in Trondheim had a similar heating system.

But that dark night was still some years off. Now Snorri, the richest and most powerful man in Iceland, was busy building a sauna with stone walls and floor. Steam was piped to it from the nearby hotspring via stone-and-clay conduits. Steam pipes may also have run under the floor of the parlor and feasthall, like a Roman hypocaust; the archbishop’s palace in Trondheim had a similar heating system.Snorri enlarged the hotspring-fed bathing pool to the south of the houses. His circular, stone-lined pool was 12 feet in diameter and had a ledge to sit on. The hot water was piped 350 from the spring in a buried, stone-lined channel. A hidden door in the hillside opened onto a convenient tunnel that led from the pool to the basement below Snorri’s parlor or writing studio. A curved stone stairway, perhaps concealed in a wall, led up to his room.

Finally, the archaeologists found that around the whole complex Snorri built a wall of enormous stones and turf blocks topped by wooden stakes. It had drawbridges facing north and south, making Reykholt a seemingly impregnable fortress. Later events would prove its defenses were showy, but easily breached. Snorri had paid more attention to comfort and prestige than safety. As Sturlunga Saga describes him, Snorri Sturluson was “a man of many pleasures.”

Finally, the archaeologists found that around the whole complex Snorri built a wall of enormous stones and turf blocks topped by wooden stakes. It had drawbridges facing north and south, making Reykholt a seemingly impregnable fortress. Later events would prove its defenses were showy, but easily breached. Snorri had paid more attention to comfort and prestige than safety. As Sturlunga Saga describes him, Snorri Sturluson was “a man of many pleasures.”This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. Thanks to Guðrún Sveinbjarnardóttir for permission to reproduce her photograph of Snorri's stairs and to Guðmundur Oddur Magnússon (GOddur) for the use of his drawing of Reykholt. An earlier version of this essay appeared in the August 15 edition of Logberg-Heimskringla, the Icelandic Community Newspaper. See http://www.lh-inc.ca/Article2.asp. Order Reykholt: Archaeological Investigations at a High Status Farm in Western Iceland from the National Museum of Iceland: http://www.thjodminjasafn.is/utgafa/baekur/nr/3436

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure.

Published on December 19, 2012 07:58

December 12, 2012

The Tolkien Connection

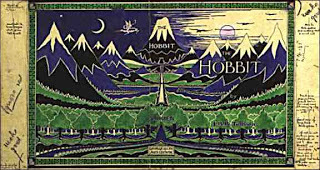

People often ask me how I became interested in Iceland. I have no Icelandic ancestors (that I know of). I’d never heard of Iceland until I went to college. Reading Snorri Sturluson’s Edda for a class on mythology, I began recognizing names: Bifur, Bafur, Bombor, Nori, Ori, Oin, and … Gandalf! These were all names from The Hobbit. What were J.R.R. Tolkien’s wizard and his dwarves doing in medieval Iceland?

People often ask me how I became interested in Iceland. I have no Icelandic ancestors (that I know of). I’d never heard of Iceland until I went to college. Reading Snorri Sturluson’s Edda for a class on mythology, I began recognizing names: Bifur, Bafur, Bombor, Nori, Ori, Oin, and … Gandalf! These were all names from The Hobbit. What were J.R.R. Tolkien’s wizard and his dwarves doing in medieval Iceland?Tolkien, I learned, was deeply influenced by Icelandic literature. The tale of Sigurd the Dragon-Slayer appeared in Andrew Lang’s Red Fairy Book, published in 1890, two years before Tolkien was born. Reading it as a boy, Tolkien said, “I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fafnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever cost of peril.”

At 16, having already learned Latin, Greek, French, German, Anglo-Saxon, and a little Welsh, Tolkien picked up the Volsunga Saga in Icelandic and began puzzling it out. He soon was relaying the gory parts to his friends.

As a student at Oxford University, Tolkien read Snorri’s Edda, the Poetic Edda, and the major sagas. During World War I he fought on the Somme, returning to England with trench fever in November 1916. In the hospital he began writing his fantastical tales of Middle-earth.

As a student at Oxford University, Tolkien read Snorri’s Edda, the Poetic Edda, and the major sagas. During World War I he fought on the Somme, returning to England with trench fever in November 1916. In the hospital he began writing his fantastical tales of Middle-earth.In 1920, he took a post at Leeds University and taught a linguistics course that featured Icelandic. He also formed a student Viking Club, mixing beer bashes with saga-reading and the composing of silly songs in Old Icelandic.

In 1925, as a new professor in the English Department at Oxford, Tolkien suggested substituting Icelandic literature for a few of the many hours devoted to Shakespeare. Reading the sagas and Eddas was more important than reading Shakespeare, Tolkien argued, because the Icelandic books were more central to the English language and to our modern world.

Tolkien won over his Oxford colleagues with a version of the Viking Club, inviting his fellow dons to read Icelandic literature aloud with him. One of these was C.S. Lewis, who would later write the classic fantasy series The Chronicles of Narnia.

It was Lewis who urged Tolkien to publish The Hobbit, which he did in 1937. Lewis wrote to a childhood friend, “It is so exactly like what we would both have longed to write (or read) in 1916: so that one feels he is not making it up but merely describing the same world into which all three of us have the entry.”

That world was largely Icelandic. Many of the characters and motifs readers assume Tolkien had invented were based on Snorri’s Edda and Heimskringla, the Poetic Edda, and the Icelandic sagas.

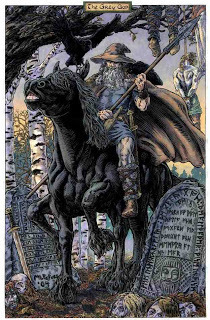

The wizard Gandalf, for example, is an “Odinic wanderer” (in Tolkien’s words)—like the old man with a broad-brimmed hat and a staff who wanders the nine worlds in Snorri’s tales and sits by King Olaf’s bedside keeping him up late with his wondrous stories.

The wizard Gandalf, for example, is an “Odinic wanderer” (in Tolkien’s words)—like the old man with a broad-brimmed hat and a staff who wanders the nine worlds in Snorri’s tales and sits by King Olaf’s bedside keeping him up late with his wondrous stories. Besides the wizard, Icelandic literature inspired Tolkien’s dwarves and elves, dragon, shapeshifter, warrior women, riders, giant eagles, and trolls, not to mention his wargs, barrow-wights, magic swords, and the cursed ring of power.

Even the landscape of Tolkien’s Middle-earth (except for the very-English Shire) is Icelandic. Although Tolkien never visited Iceland, he read author and arts-and-crafts designer William Morris’s journals of his travels there in the 1870s. The hobbit Bilbo Baggins’s ride to “the last homely house” of Rivendell, for example, matches one of William Morris’s horseback excursions in Iceland point-for-point.

Finally, Tolkien was enchanted by saga style. Like Snorri Sturluson, Tolkien knew the worth of glamour—in its first meaning of enchantment or deceit. By “fantasy” Tolkien meant “a quality of strangeness and wonder” that frees things and people from “the drab blur or triteness of familiarity.” The Hobbit does all that—thanks to its Icelandic roots.

When Peter Jackson’s movie adaptation of The Hobbit is released this December 14, Icelanders and people of Icelandic descent can take pride in the fact that their literature is still central to our modern world. New Zealand may be the movie’s setting, but Iceland is its soul.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, just published by Palgrave Macmillan. The final chapter details Snorri’s effect on Tolkien and fantasy literature.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, just published by Palgrave Macmillan. The final chapter details Snorri’s effect on Tolkien and fantasy literature.The black-and-white image above is not Gandalf, but Odin, as drawn by Georg von Rosen in 1886, before Tolkien was born. The photo of Gandalf is from “The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey,” downloaded from the official movie site: http://thorinoakenshield.net/the-hobbit-photo-gallery/#scenes

Published on December 12, 2012 13:13

December 5, 2012

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri: Part III

Where did poetry come from? According to Snorri, it is the gift of Odin—but Snorri’s tale of the honey-mead that turns all drinkers into poets is dismissed by modern critics as “one of his more imaginative efforts.”

Where did poetry come from? According to Snorri, it is the gift of Odin—but Snorri’s tale of the honey-mead that turns all drinkers into poets is dismissed by modern critics as “one of his more imaginative efforts.”The tale tells us more about this 13th-century Icelandic chieftain—poetry and mead being two of Snorri Sturluson’s favorite things—than it tells us what people really believed in pagan Scandinavia. Like most of what we think of as Norse mythology, it was written to impress the 14-year-old king of Norway.

As I learned while researching his life for my biography, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, Snorri traveled to Norway in 1218 expecting to be named to the post of King’s Skald.

Skalds, or court poets, had been a fixture at the Norwegian court for 400 years. They were swordsmen, occasionally. But more often, skalds were a king’s ambassadors, counselors, and keepers of history. They were part of the high ritual of his royal court, upholding the Viking virtues of generosity and valor. They legitimized his claim to kingship. Sometimes skalds were scolds (the two words are cognates), able to say in verse what no one dared tell a king straight. They were also entertainers: A skald was a bard, a troubador, a singer of tales—a time-binder, weaving the past into the present.

We know the names of over 200 skalds from before 1300, including Snorri, one of his nieces, and three of his nephews. We can read (or, at least, experts can) hundreds of their verses: In the standard edition, they fill a thousand two-column pages. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking age, what they loved, what they despised. The big surprise is how much they adored poetry.

We know the names of over 200 skalds from before 1300, including Snorri, one of his nieces, and three of his nephews. We can read (or, at least, experts can) hundreds of their verses: In the standard edition, they fill a thousand two-column pages. What skalds thought important enough to put into words provides most of what we know today about the inner lives of people in the Viking age, what they loved, what they despised. The big surprise is how much they adored poetry. But when Snorri came to Norway for the first time in 1218, he found that the 14-year-old king despised Viking poetry. King Hakon would rather read the romances of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table than hear poems recited about the splendid deeds of his own ancestors. He thought skaldic poetry was too hard to understand.

He was right about that.

I think of skaldic poetry as a cross between a riddle and a trivia quiz. The riddle part involves disentangling the interlaced phrases so that they form grammatical sentences. The quiz part is the kennings. As I wrote earlier in this series, Snorri defined kennings and may even have coined the term. “Otter of the ocean,” for a ship, is an easy one, as is “spear clash” for battle. It’s a double kenning if you call a sword “fire of the spear clash,” and you can extend it even further by calling a warrior “wielder of the fire of the spear clash.”

It can take a while to solve these puzzles. But once you have, the meaning of a skaldic poem was often a letdown. As one expert in Viking poetry sighs, “When one has unravelled the meaning behind the kennings, one finds that almost a whole stanza contains only the equivalent of the statement ‘I am uttering poetry.’”

Young king Hakon was not the only king of Norway to acknowledge he had no taste for the stuff.

Young king Hakon was not the only king of Norway to acknowledge he had no taste for the stuff. But Snorri thought skaldic poetry was wonderful. He also saw it as his ticket to power at the Norwegian court. Everyone knew the best skalds were Icelanders. Being a skald had for generations been a way for an Icelander to get a foot in the door at the court of Norway. It was a mark of distinction, and Snorri had fully expected it to work in his case.

It didn’t. Snorri went home to Iceland in 1220 disappointed. He began writing his Edda to introduce the young king to his heritage. To convince King Hakon of the importance of poets, Snorri made up the tale of how Odin gave men the gift of poetry. According to one scholar, his tale perverts an ancient ceremony known from Celtic sources. To consecrate a king a sacred maiden sleeps with the chosen man, then serves him a ritual drink. Snorri turns it into a comic seduction scene: one night of blissful sex for a lonely giant girl in exchange for one sip of the mead of poetry.

Here is how I tell it in Song of the Vikings:

Here is how I tell it in Song of the Vikings:The story begins with the feud between the Aesir gods (Odin and Thor among them) and the Vanir gods (who included the love gods Freyr and Freyja). They declared a truce and each spat into a crock to mark it.

Odin took the spittle and made it into a man. Truce-man traveled far and wide, teaching men wisdom, until he was killed by the dwarves. (They told Odin that Truce-man had choked on his own learning.)

The dwarves poured his blood into a kettle and two crocks, mixed it with honey and made the mead of poetry. To pay off a killing, the dwarves gave the mead to the giant Suttung, who hid it in the depths of a mountain with his daughter as its guard.

Odin set out to fetch it. He tricked Suttung’s brother into helping him, and they bored a hole through the mountain. Odin changed into a snake and slithered in, returning to his glorious god-form to seduce Suttung’s lonely daughter. He lay with her for three nights; for each night she paid him a sip of mead. On the first sip, he drank dry the kettle. With the next two sips, he emptied the crocks.

Then he transformed himself into an eagle and took off. Suttung spied the fleeing bird. Suspicious, he changed into his giant eagle form and made chase. It was a near thing. To clear the wall of Asgard, Odin had to squirt some of the mead out backwards—the men who licked it up can write only doggerel. The rest of the mead he spat into the vessels the gods had set out. He shared it with certain exceptional men; they are called poets.

So whenever you hear a really bad poem, imagine the poet on his hands and knees outside the wall of Valhalla, licking up bird droppings.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure, or meet me on tour: 12/6: Phoenix Books, Burlington, VT @ 7:00 12/13: Cobleigh Library, Lyndonville, VT @ 7:00

Published on December 05, 2012 11:35

November 28, 2012

Saga Sites

On Monday I give a lecture at Scandinavia House in New York in conjunction with the exhibition “Saga Sites,” in which the 19th-century paintings of W.G. Collingwood are paired with the 20th-century photographs of Einar Falur Ingólfsson—both artists responding to the fact that the places made famous by the medieval Icelandic sagas still carry the same names from a thousand years ago and look much like they did then.

On Monday I give a lecture at Scandinavia House in New York in conjunction with the exhibition “Saga Sites,” in which the 19th-century paintings of W.G. Collingwood are paired with the 20th-century photographs of Einar Falur Ingólfsson—both artists responding to the fact that the places made famous by the medieval Icelandic sagas still carry the same names from a thousand years ago and look much like they did then.It was this, the immediacy of story, that drew me to Iceland first in 1986 and brought me back again and again to see the saga sites. The sagas are alive in the landscape. There is a story everywhere you turn.

Sometimes, several stories.

“You must go to Reykholt and see Snorri’s pool.” It was 1994 when I was given this order by an Icelandic farmwife. I remember it vividly for two reasons.

First, it was the wrong Snorri. I was then researching the life of Snorri Goði, the 11th-century hero of Eyrbyggja Saga, for a historical novel (never published). The Snorri with the famous geothermally heated hot-tub on his estate at Reykholt was Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century author of the Edda.

Second, I had been invited into the farm kitchen for coffee—a usual occurrence on my trips to Iceland—and, like many Icelandic kitchens, there were too few chairs for the company. An old man got up to give me a seat. I gratefully accepted—and sat in something wet. I did not want to know what. Surely, he had just been out in the rain bringing in the cows? I don’t recall if it was raining, but it often rains in Iceland.

I didn’t go to Reykholt until 2001, when my family joined me in Iceland and we took in all the standard tourist sites. I wasn’t much impressed. I had seen—and soaked in—other geothermal pools by then. Iceland has more than 250 hotsprings. Their water heats the entire city of Reykjavik, including the city swimming pools.

On a riding tour into the southern highlands, I had enjoyed a swim in the pools at Landmannalaugar, where a hotspring overflows into a cold river, providing a gradient of temperatures sure to please any stiff or sore horse-woman.

I recalled a pool barely cool enough to dip in, deep in the lava field that surrounded the abandoned farmhouse we rented in 1996 for my husband to write his book Summer at Little Lava.

I had twice visited the pool in Skagafjord where Grettir the Outlaw warmed himself after his four-mile swim through the cold north Atlantic from his hideout on the island of Drangey.

But it wasn’t until I began researching Snorri Sturluson’s life to write Song of the Vikings that I learned what this flowing hot water meant for the people of medieval Iceland.

The first story we know about Snorri Sturluson is the story of how he came to be the fosterson of the rich and learned chieftain Jon Loftsson of Oddi, known as the uncrowned king of Iceland. Jon offered to educate Sturla of Hvamm’s three-year-old son, Snorri, to end a feud over hot water.

The story begins beside the river Hvita in the west of Iceland, where lay the rich farm of Deildartunga. It was not a large farm, but was rich in its ability to make hay, for it owned extensive water meadows along the river bottom. Even better, these were warm water meadows.

The Hvita is an ice-cold glacial river. Its name, “White River,” denotes not whitewater rapids but milky glacial till. Yet not far from the river, beneath a bluff painted pink with mineral deposits, bubbled a hotspring: the highest volume hotspring in all of Iceland.

The hotspring at Tunga provided warm water for cooking and bathing and washing clothes, but these were minor benefits compared to its effect on the hayfields. The hot water that spilled into the river and spread over the floodplain made the grass sprout sooner after winter and stay green longer in the fall.

Grass was the foundation of Iceland’s medieval economy, hay being the only crop that grew well. Thanks to his hotspring, the farmer at Tunga could make more hay than his neighbors and so keep more cows, sheep, and horses. Cows were highly valued because the Viking diet was based on milk and cheese. Sheep were milked as well (sheep’s milk is richer in vitamin C; important in a land where no vegetables grow), but sheep were prized mostly for their wool: Cloth was Iceland’s major export. Horses were necessary for transportation, since Iceland has few navigable rivers.

The farmer at Tunga’s wealth—reckoned, the usual way, in cows or “cow equivalents” (six ewes equaling one cow)—was eight hundred head of cattle. Eighty head was considered a decent farm. No wonder the two biggest men in the district took notice in 1180, between the Winter of Sickness and the Summer of No Grass, when Tunga fell vacant.

One of these men was the chieftain Pall Solvason, who lived up the river at Reykholt.

The other was the chieftain Bodvar Thordarson, whose estate was a few miles down the river. Bodvar’s daughter was married to Sturla of Hvamm, which is how Snorri’s father got involved in the feud.

Jon Loftsson, the uncrowned king of Iceland, was brought in only after Pall Solvason’s wife lost her temper during a meeting at Reykholt to decide ownership of the farm. She ran into the circle of men with a kitchen knife in her hand and thrust it at Sturla’s eye, saying, “Why should I not make you look like Odin, whom you so wish to resemble?”

Someone grabbed her from behind and the blade missed Sturla’s eye, but it caused quite a gash.

It was in payment for this attack that Snorri Sturluson went to Oddi, where he received the best education to be found in Iceland at the time. The benefit to us—to all of Western culture—is immeasurable, for it was at Oddi that Snorri became a writer.

And all due to a fight over hot water. Some say the reason Snorri took over Reykholt many years later was also to avenge the attack on his father’s eye—but that’s another story.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. On December 3 at 6:30, I will be giving a lecture at Scandinavia House in conjunction with the “Saga Sites” exhibition. See http://www.scandinaviahouse.org/events_exhibitions_current.html

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure, or meet me on tour: 11/29: Sterling College, Craftsbury Common, VT @ 6:30 11/30: Northshire Bookstore, Manchester Center, VT @ 7:00 12/3: Scandinavia House, New York City @ 6:30 12/6: Phoenix Books, Burlington, VT @ 7:00

Published on November 28, 2012 07:39

November 21, 2012

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri: Part II

It was Neil Gaiman who convinced me. Reading American Gods, I was delighted to see the character Mr. Wednesday echoing Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century Icelandic writer whose biography forms the core of my book Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths.

It was Neil Gaiman who convinced me. Reading American Gods, I was delighted to see the character Mr. Wednesday echoing Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century Icelandic writer whose biography forms the core of my book Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths.Mr. Wednesday, I knew, was the Norse god Odin (from the Old English spelling, Woden’s Day). In American Godshe is a tricky figure to pin down, attractive, untrustworthy, all-powerful, but also afraid—for the old gods have been nearly forgotten. And that, Gaiman implies, would be a disaster for all of us.

Which is exactly what Snorri Sturluson was trying to say in his Edda.

Seeing Snorri through Gaiman’s lens convinced me he was more than an antiquarian, more than an academic collector of old lore. Like Gaiman himself, Snorri was a wonderfully imaginative writer.

And both of them—all writers, in fact—are devotees of the god of Wednesday who, according to Snorri, is the god of poetry and storytelling.

And both of them—all writers, in fact—are devotees of the god of Wednesday who, according to Snorri, is the god of poetry and storytelling.We know very little about Odin, except for what Snorri wrote. We have poems containing cryptic hints. We have rune stones whose blunt images and few words tantalize. Only Snorri gives us stories, with beginnings and ends and explanations—but also with contradictions and puzzles.

Almost everything we know about Norse mythology comes from Snorri’s Edda and Heimskringla, two books he wrote between 1220 and 1240 to gain influence at the Norwegian court.

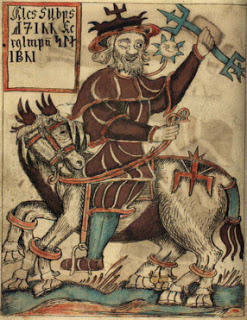

The Edda is a handbook on how to write Viking court poetry, much of which refers obscurely to Norse myths. The god Odin in Snorri’s Edda is the ruler of heaven and earth, the greatest and most glorious of the gods. Odin and his brothers fashioned the world from the body of the giant Ymir. But Snorri also describes Odin in very Christian terms as the All-father.

This Odin overlaps with, but is not entirely the same as, the King Odin in Snorri’s Heimskringla. Heimskringla means “The Round World” or “The Orb of the Earth” (from the first two words of the introduction). It is a collection of 16 sagas in which Snorri traces the history of Norway from its founding in the shadows of time by Odin the Wizard-King (a human king who later was mistakenly revered as a god, Snorri explains) to 1177 A.D., the year before Snorri’s birth.

It is this Odin the Wizard-King who inspired Mr. Wednesday—as well as Tolkien’s Gandalf, which is a subject for another time.

King Odin “could change himself and appear in any form he would,” Snorri writes, including bird, beast, fish, or dragon. He raised the dead and questioned them. He owned two talking ravens who flew far and wide, gathering news. He worked magic with runes, and spoke only in verse or song. With a word he “slaked fire, stilled the sea, or turned winds in what way he would.” He knew “such songs that the earth and hills and rocks and howes opened themselves for him,” and he entered and stole their treasures. “His foes feared him, but his friends took pride in him and trusted in his craft.”

Long after King Odin’s death, when he had become a god, Snorri says, the missionary King Olaf Tryggvason, who forced Norway to become Christian around the year 1000, held a feast to celebrate Easter. An unknown guest arrived, “an old man of wise words, who had a broad-brimmed hat and was one-eyed.” The old man told tales of many lands, and the king “found much fun in his talk.” Only the bishop recognized this dangerous guest. He convinced the king that it was time to retire, but Odin followed them into the royal chamber and sat on the king’s bed, continuing his wondrous stories. The bishop tried again. “It is time for sleep, your majesty.” The king dutifully closed his eyes. But a little later King Olaf awoke. He asked that the storyteller be called to him, but the one-eyed old man was nowhere to be found.

Nowhere but in Snorri’s books. And, perhaps, in his soul.

Odin One-eye was Snorri’s favorite of all the Norse gods and goddesses. Following tradition, he placed Odin in his Edda at the head of the Viking pantheon of 12 gods and 12 goddesses. Then he increased his power so that, like the Christian God the Father, Snorri’s Odin All-Father governed all things great and small.

Odin One-eye was Snorri’s favorite of all the Norse gods and goddesses. Following tradition, he placed Odin in his Edda at the head of the Viking pantheon of 12 gods and 12 goddesses. Then he increased his power so that, like the Christian God the Father, Snorri’s Odin All-Father governed all things great and small.Icelanders had, in fact, long favored Thor, the god of Thursday. They named their children after the mighty Thunder God: In a twelfth-century record of Iceland’s first settlers, a thousand people bear names beginning with Thor; none are named for Odin. Nor did the first Christian missionaries to Iceland find cults of Odin. Odin is rarely mentioned in the sagas. For a good sailing wind Icelanders called on Thor. But Snorri wasn’t fond of Thor—except for comic relief. Thor was the god of farmers and fishermen.

Odin was a god for aristocrats—not just the king of gods, but the god of kings.

He had a gold helmet and a fine coat of mail, a spear, and a gold ring that magically dripped eight matching rings every ninth night. No problem for him to be a generous lord, a gold-giver.

He had a grand feast hall named Valhalla, where dead heroes feasted on unlimited boiled pork and mead. Snorri is our only source for many of the details of what Valhalla looked like: its roof tiled with gold shields, the juggler tossing seven knives, the fire whose flames were swords—even the beautiful Valkyries, the warrior women who serve mead to the heroes. Old poems and sagas that Snorri does not quote describe the Valkyries as monsters. These Valkyries are troll women of gigantic size who ride wolves and pour troughs of blood over a battlefield. They row a boat through the sky, trailing a rain of blood. They are known by their “evil smell.” One rode at the head of an army carrying a cloth “which hung down in tatters and dripped blood.” She whipped the cloth about, “and when the ragged ends touched a man’s neck she jerked off his head.” Snorri didn’t care for that kind of Valkyrie.

Finally, Odin had the best horse, the eight-legged Sleipnir. Snorri is our only source for the memorable comic tale of how Odin’s wonderful horse came to be.

Finally, Odin had the best horse, the eight-legged Sleipnir. Snorri is our only source for the memorable comic tale of how Odin’s wonderful horse came to be. Here’s how I tell it in Song of the Vikings:

One day while Thor was off fighting trolls in the east, a giant entered the gods’ city of Asgard. He was a stonemason, he said, and offered to build the gods a wall so strong it would keep out any ogre or giant or troll. All he wanted in return was the sun and the moon and goddess Freya for his wife.

The gods talked it over, wondering how they could get the wall for free.

“If you build it in one winter, with no one’s help,” the gods said, thinking that impossible, “we have a deal.”

“Can I use my stallion?” the giant asked.

Loki replied, “I see no harm in that.” The other gods agreed. They swore mighty oaths.

The giant got to work. By night the stallion hauled enormous loads of stone, by day the giant laid them up. The wall rose, course upon course. With three days left of winter, it was nearly done.

“Whose idea was it to spoil the sky by giving away the sun and the moon—not to mention marrying Freyja into Giantland?” the gods shouted. They wanted out of their bargain. “It’s all Loki’s fault,” they agreed. “He’d better fix it.”

Loki transformed himself into a mare in heat. That evening, when the mason drove his stallion to the quarry, his horse was uncontrollable. It broke the traces and ran after the mare. The giant chased after them all night and, needless to say, he got no work done.

Nor could he finish the wall the next day with no stone. His always-edgy temper snapped. He flew into a giant rage.

The gods’ oaths were forgotten. Thor raised his terrible hammer and smashed the giant’s skull.

Eleven months later, Loki had a foal. It was grey and had eight legs. It grew up to be the best horse among gods and men.

In my next post, I’ll look at how Odin gave men poetry.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com."The Grey God" is by Michael L. Peters; see more of his art at http://mlpeters.com.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It originally appeared on the science fiction and fantasy lovers website Tor.com."The Grey God" is by Michael L. Peters; see more of his art at http://mlpeters.com. Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure, or meet me on tour: 11/29: Sterling College, Craftsbury Common, VT @ 6:30 11/30: Northshire Bookstore, Manchester Center, VT @ 7:00 12/3: Scandinavia House, New York City @ 6:30 12/6: Phoenix Books, Burlington, VT @ 7:00

Published on November 21, 2012 04:53

November 14, 2012

Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri

We think of Norse mythology as ancient and anonymous. But in fact, most of the stories we know about Odin, Thor, Loki, and the other gods of Scandinavia were written by the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson.

We think of Norse mythology as ancient and anonymous. But in fact, most of the stories we know about Odin, Thor, Loki, and the other gods of Scandinavia were written by the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson.Notice I said “written” and not “written down.” Snorri was a greedy and unscrupulous lawyer, a power-monger whose ambition led to the end of Iceland’s independence and to its becoming a colony of Norway.

But Snorri was also a masterful poet and storyteller who used his creative gifts to charm his way to power. Studying Snorri’s life to write my book Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, I learned how he came to write his Edda, a book that’s been called “the deep and ancient wellspring of Western culture,” and his Heimskringla, a history of Norway from its founding in the far past by Odin the Wizard-King.

These two books are our main, and sometimes our only, source for much of what we think of as Norse mythology—and it’s clear, to me at least, that Snorri simply made a lot of it up. For example, Snorri is our only source for these seven classic Norse myths:

1. The Creation of the World in Fire and Ice2. Odin and his Eight-legged Horse 3. Odin and the Mead of Poetry4. How Thor Got His Hammer of Might 5. Thor’s Visit to Utgard-Loki6. How Tyr Lost His Hand7. The Death of Beautiful Baldur

Over the next few weeks, I’ll go through these seven Norse myths one by one and try to explain why I think Snorri made them up. But first, you may be wondering why Snorri wrote these myths of the old gods and giants in the first place. Iceland in the 13th century was a Christian country. It had been Christian for over 200 years.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll go through these seven Norse myths one by one and try to explain why I think Snorri made them up. But first, you may be wondering why Snorri wrote these myths of the old gods and giants in the first place. Iceland in the 13th century was a Christian country. It had been Christian for over 200 years. He did so to gain influence at the Norwegian court. When Snorri came to Norway for the first time in 1218, he was horrified to learn that chivalry was all the rage. The 14-year-old King Hakon would rather read the romances of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table than hear poems recited about the splendid deeds of his own ancestors, the Viking kings. The Viking poetry Snorri loved was dismissed as old-fashioned and too hard to understand. So, to reintroduce the young king to his heritage Snorri Sturluson began writing his books.

The Edda is essentially a handbook on Viking poetry. For the Vikings were not only fierce warriors, they were very subtle artists. Their poetry had an enormous number of rules for rhyme and meter and alliteration. It also had kennings. Snorri defined kennings in his Edda (he may also have coined the term). As Snorri explained, there are three kinds: “It is a simple kenning to call battle ‘spear clash’ and it is a double kenning to call a sword ‘fire of the spear-clash,’ and it is extended if there are more elements.”

Kennings are rarely so easy to decipher as these. Most kennings refer—quite obscurely—to pagan myths.

Kennings were the soul of Viking poetry. One modern reader speaks of the “sudden unaccountable surge of power” that comes when you finally perceive in the stream of images the story they represent. But as Snorri well knew, when those stories were forgotten, the poetry would die. That’s why, when he wrote his Edda to teach the young king of Norway about Viking poetry, he filled it with Norse myths.

But it had been 200 years since anyone had believed in the old gods. Many of the references in the old poems were unclear. The old myths had been forgotten. So Snorri simply made things up to fill in the gaps.

Let me give you an example. Here’s Snorri’s Creation story:

Let me give you an example. Here’s Snorri’s Creation story:In the beginning, Snorri wrote, there was nothing. No sand, no sea, no cooling wave. No earth, no heaven above. Nothing but the yawning empty gap, Ginnungagap. All was cold and grim.

Then came Surt with a crashing noise, bright and burning. He bore a flaming sword. Rivers of fire flowed till they turned hard as slag from an iron-maker’s forge, then froze to ice.

The ice-rime grew, layer upon layer, till it bridged the mighty, magical gap. Where the ice met sparks of flame and still-flowing lava from Surt’s home in the south, it thawed and dripped. Like an icicle it formed the first frost-giant, Ymir, and his cow.

Ymir drank the cow’s abundant milk. The cow licked the ice, which was salty. It licked free a handsome man and his wife.

They had three sons, one of whom was Odin, the ruler of heaven and earth, the greatest and most glorious of the gods: the All-father, who “lives throughout all ages and … governs all things great and small…,” Snorri wrote, adding that “all men who are righteous shall live and dwell with him” after they die.

Odin and his brothers killed the frost-giant Ymir. From his body they fashioned the world: His flesh was the soil, his blood the sea. His bones and teeth became stones and scree. His hair were trees, his skull was the sky, his brain, clouds.

From his eyebrows they made Middle Earth, which they peopled with men, crafting the first man and woman from driftwood they found on the seashore.

So Snorri explains the creation of the world in the beginning of his Edda. Partly he is quoting an older poem, the “Song of the Sibyl,” whose author he does not name. Partly he seems to be making it up—especially the bit about the world forming in a kind of volcanic eruption, and then freezing to ice.

If this myth were truly ancient, there could be no volcano. Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, the Scandinavian homelands, are not volcanic. Only Iceland—discovered in 870, when Norse paganism was already on the wane—is geologically active. In medieval times, Iceland’s volcanoes erupted ten or a dozen times a century, often burning through thick glaciers. There is nothing so characteristic of Iceland’s landscape as the clash between fire and ice.

If this myth were truly ancient, there could be no volcano. Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, the Scandinavian homelands, are not volcanic. Only Iceland—discovered in 870, when Norse paganism was already on the wane—is geologically active. In medieval times, Iceland’s volcanoes erupted ten or a dozen times a century, often burning through thick glaciers. There is nothing so characteristic of Iceland’s landscape as the clash between fire and ice.That the world was built out of Ymir’s dismembered body is Snorri’s invention. The idea is suspiciously like the cosmology in popular philosophical treatises of the 12th and 13th centuries. These were based on Plato, who conceived of the world as a gigantic human body.

Ymir’s cow may have been Snorri’s invention too. No other source mentions a giant cow, nor what the giant Ymir lived on. A cow, to Snorri, would have been the obvious source of monstrous sustenance. Like all wealthy Icelanders, Snorri was a dairyman. He was also, as I’ve said, a Christian. It fits with his wry sense of humor for the first pagan god to be born from a salt lick.

Finally, the idea that Odin was the All-father, who gave men “a soul that shall live and never perish” and who welcomes the righteous to Valhalla after death is Snorri’s very-Christian idea. He was trying to make the old stories acceptable to a young Christian king who had been brought up by bishops.

In my next post, I’ll look at how Snorri created the character of the god Odin.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, published by Palgrave Macmillan. Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure, or meet me on tour: 11/17: Eagle Eye Books, Decatur, GA @ 1:30 11/29: Sterling College, Craftsbury Common, VT @ 6:30 11/30: Northshire Bookstore, Manchester Center, VT @ 7:00 12/3: Scandinavia House, New York City @ 6:30 12/6: Phoenix Books, Burlington, VT @ 7:00

Published on November 14, 2012 05:17

November 7, 2012

What is a Saga?

From “The Forsyte Saga” in 1906 to “The Twilight Saga” a hundred years later, we’ve grown used to our books (or their movie adaptations) being called “sagas.” But “saga” is an Icelandic word: How did it come to be so popular?

From “The Forsyte Saga” in 1906 to “The Twilight Saga” a hundred years later, we’ve grown used to our books (or their movie adaptations) being called “sagas.” But “saga” is an Icelandic word: How did it come to be so popular?The first sagas were written in Iceland in the Middle Ages. They are bloody and thrilling and filled with a realism we don’t expect from medieval literature. Photographer Einar Falur Ingólfsson, whose exhibition “Saga Sites” is currently showing at Scandinavia House in New York, calls them “the first Scandinavian crime novels.”

Tipped on the southern edge of the Arctic Circle, Iceland earns its name: It holds the largest glacier in Europe. The first sight sailors see, approaching Iceland, is the silvery gleaming arc of the sun reflecting off the ice cap. Closer in, the eye is struck by the blackness of the shore, the lava sand, the cliffs reaching into the sea in crumpled stacks and arches, the rocks and crags all shaped by fire. For Iceland is a volcanic land. Even when an eruption is not in progress, smoke from its hotsprings and steam vents rises high in the air. Fire and ice have shaped this island. Its central highlands—half its total area—are desert: ash, ice, moonscapes of rock. Grass grows well along Iceland’s coasts, but little else thrives. There are no tall trees—and so no shipbuilding: a dangerous lack for island-dwellers. Other natural resources are equally scarce. Iceland has no gold, no silver, no copper, no tin. The iron is impure bog-iron, difficult to smelt. The first settlers, Vikings emigrating from Norway and the British Isles between 870 and 930, chose Iceland because they had nowhere else to go. Nowhere they could live free of a king. At least, that’s how the story goes.

Iceland has many such stories. The arctic winter nights are long. To while away the dark hours, Icelanders since the time of the settlement told stories, recited poems, and—once the Christian missionaries taught them the necessary ink-quill-and-parchment technology in the early eleventh century—wrote and read books aloud to each other.

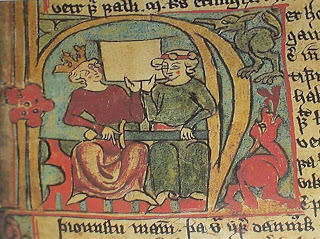

Iceland has many such stories. The arctic winter nights are long. To while away the dark hours, Icelanders since the time of the settlement told stories, recited poems, and—once the Christian missionaries taught them the necessary ink-quill-and-parchment technology in the early eleventh century—wrote and read books aloud to each other.Three of those books, including the most influential, are linked to Snorri Sturluson. Writers of prose in his day did not sign their works, so we can’t be one-hundred-percent certain of his authorship. He was named as author of the Edda in the early 1300s, of Heimskringla by the 1600s (supposedly based on a lost medieval manuscript), and of Egil’s Saga not until the 1800s.

Egil’s Saga may be the first true Icelandic saga, establishing the genre and granting the word “saga” the meaning we still use today: a long and detailed novel about several generations of a family.

In Egil’s Saga, Snorri created the two competing Viking types who would give Norse culture its lasting appeal. Egil’s Saga begins with a Viking named “Evening Wolf” (reputed to be a werewolf), and his two sons; his surviving son also had two sons, one of whom is Egil. In each generation, one son is tall, blond, and blue-eyed, a stellar athlete, a courageous fighter, an independent, honorable man who laughs in the face of danger, dying with a poem or quip on his lips. The other son is dark and ugly, a werewolf, a wizard, a poet, a berserk, a crafty schemer who knows every promise is contingent. Both sons, bright and dark, are Vikings.

In one famous scene, Egil’s grandfather Kveld-Ulf decides to leave Norway after the murder of his son Thorolf by the king. Out at sea, he took his revenge. Recognizing a dragonship that Thorolf had owned, he attacked. Kveld-Ulf leaped into the stern, his remaining son, Skalla-Grim, leaped into the bow, and both went berserk. They cut down every man in their way, until the deck was cleared. Kveld-Ulf fought with a halberd, a kind of long-handled axe with a spike on it. He hewed at the ship’s captain, we’re told, “slicing through both helmet and head and burying the weapon right up to the shaft. Then he gave it a hard tug towards himself, lifted [the captain] into the air and tossed him overboard.”

In one famous scene, Egil’s grandfather Kveld-Ulf decides to leave Norway after the murder of his son Thorolf by the king. Out at sea, he took his revenge. Recognizing a dragonship that Thorolf had owned, he attacked. Kveld-Ulf leaped into the stern, his remaining son, Skalla-Grim, leaped into the bow, and both went berserk. They cut down every man in their way, until the deck was cleared. Kveld-Ulf fought with a halberd, a kind of long-handled axe with a spike on it. He hewed at the ship’s captain, we’re told, “slicing through both helmet and head and burying the weapon right up to the shaft. Then he gave it a hard tug towards himself, lifted [the captain] into the air and tossed him overboard.” With this passage the Viking Hero was born. Kveld-Ulf’s deck-clearing, axe-hewing, bloodthirsty berserk rage has been reenacted countless times in novels and films and comic strips. He and Skalla-Grim didn’t even know whose men they were butchering. Only after more than fifty men died did they catch two and ask who was on the ship, learning that among the dead were the king’s young cousins, boys of ten and twelve. Thorolf’s death was fully avenged.

Skalla-Grim composed a poem about it (true Vikings were also good poets). He told the two lucky captives to go to the king and recite it, telling him “precisely what happened and who was responsible.” Then he and his father sailed to Iceland, where 300 years later, their descendant, Snorri Sturluson would turn their lives into a saga.

This essay was adapted from my biography of Snorri Sturluson, Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, just published by Palgrave Macmillan. On December 3 at 6:30, I will be giving a lecture at Scandinavia House in conjunction with the “Saga Sites” exhibition. See http://www.scandinaviahouse.org/events_exhibitions_current.html

Other upcoming events in my book tour are:

Other upcoming events in my book tour are:11/7: Mount Holly Town Library, Belmont, VT @ 7 p.m. See http://www.thebooknookvt.com

11/8: Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY @ 4:30 p.m. See http://events.cornell.edu/event/book_reading_song_of_the_vikings

11/9: Bucknell University Bookstore, Lewisburg, PA @ 5:30 p.m. See http://bucknell.bncollege.com

11/10: The Icelandic Jólabasar Christmas Fair, American Legion Post 177, 3939 Oak Street, Fairfax, VA @ 11-3. See http://www.icelanddc.com

11/11: Webster’s Books and Cafe, State College, PA @ 6:30 p.m. See http://www.webstersbooksandcafe.com

11/12: Penn State Comparative Literature Luncheon, 102 Kern Bldg, University Park, PA @ 12:15 p.m. See http://complit.la.psu.edu/news-luncheon.shtml

11/13: Malaprop’s Bookstore Cafe, Asheville, NC @ 7 p.m. See http://www.malaprops.com

Watch the book trailer here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H0JSO2...

Or listen to me discuss the book with Tom Ashford on "On Point" from NPR station WBUR in Boston: http://onpoint.wbur.org/2012/11/06/song-of-the-vikings

Learn more at nancymariebrown.com

Published on November 07, 2012 06:48

October 31, 2012

Song of the Vikings Published Today

Today is the official publication date of Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths and the start of my Maine-to-Georgia (believe it or not!) book tour.

Today is the official publication date of Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths and the start of my Maine-to-Georgia (believe it or not!) book tour.Actually, the official date was yesterday, but the hurricane intervened—my publisher’s offices in New York were closed.

I did make it to my first event, a lecture at the Samuel Reed Hall Library at Lyndon State College in Vermont, about 3 miles from my home. LSC had electricity; we didn’t. While there, I was interviewed by Channel 7 news for local TV.

Tomorrow, I go to Portland, Maine, where I’ll be speaking at the University of Southern Maine in the Glickman Library, Room 423, at 5:00. Portland-area friends, please join me!

Here’s the rest of the tour: 11/2: Maine: Portland Free Library @ noon 11/5: New Hampshire: Dartmouth Bookstore, Hanover @ 6:00 11/7: Vermont: Mount Holly Town Library, Belmont @ 7:00 11/8: New York: Cornell University Library @ 4:30 11/9: Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Bookstore @ 5:30 11/10: Virginia: Icelandic Jólabasar, American Legion Post 177, Fairfax @ 11-3 11/11: Pennsylvania: Webster’s Bookstore, State College @ 6:30 11/12: Pennsylvania: Penn State Comparative Literature Luncheon, 112 Kern, University Park @ 12:15 11/13: North Carolina: Malaprop’s Bookstore, Asheville @ 7:00 11/17: Georgia: Eagle Eye Book Shop, Decatur @ 1:30 11/20: Massachusetts: UMass-Amherst @ 2:30 11/29: Vermont: Sterling College @ 6:30 11/30: Vermont: Northshire Bookstore, Manchester Center @ 7:00 12/3: New York: Scandinavia House, New York City @ 6:30 12/6: Vermont: Phoenix Books, Burlington, VT@ 7:00

Not near any of these events? Check out my book trailer:

Or take a peek at the jacket flap:

Snorri Sturluson, the thirteenth-century Icelandic chieftain who gave us Odin, Loki, and Thor, was as unruly as the Norse gods he created

Norse mythology has seeped into our imagination. Tales of one-eyed Odin, Thor and his mighty hammer, the trickster Loki, and the beautiful Valkyries have inspired countless writers, poets, and dreamers through the centuries, including Richard Wagner, JRR Tolkien, and Neil Gaiman. Few modern fantasy novels, films, or games are free of wandering wizards, fair elves and werewolves, dragons and dwarf smiths, magic rings and weapons, heroes that speak to birds, or trolls that turn to stone. But while Homer and Ovid are widely celebrated for their stories of Greek and Roman gods, the medieval Icelander who gave us Viking mythology is nearly forgotten.

In Song of the Vikings, author Nancy Marie Brown brings to life Snorri Sturluson, wealthy chieftain, wily politician, witty storyteller, and lover of Viking lore. She paints a vivid picture of the Icelandic landscape, with its colossal glaciers and volcanoes, steaming hot springs, and moonscapes of ash, ice, and rock. This was the world that inspired Snorri’s words, and led him to create unforgettable characters and tales, including nearly every story we know of the gods we still honor in the names Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. It was Snorri who created the archetype of the bold, blond, laugh-in-the-face-of-death Viking, and Snorri who gave the word saga the meaning it holds today.

In Song of the Vikings, author Nancy Marie Brown brings to life Snorri Sturluson, wealthy chieftain, wily politician, witty storyteller, and lover of Viking lore. She paints a vivid picture of the Icelandic landscape, with its colossal glaciers and volcanoes, steaming hot springs, and moonscapes of ash, ice, and rock. This was the world that inspired Snorri’s words, and led him to create unforgettable characters and tales, including nearly every story we know of the gods we still honor in the names Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. It was Snorri who created the archetype of the bold, blond, laugh-in-the-face-of-death Viking, and Snorri who gave the word saga the meaning it holds today. Brown takes the reader on a tour of medieval Icelandic society as well, with its web of laws and blood feuds fueled by the Icelanders’ fierce sense of independence. There Snorri’s extravagant personality and unscrupulous tactics brought him close to ruling his country—and even closer to betraying it—before he was betrayed himself. He died a coward, cringing in his cellar, his Viking ideals abandoned. But his books lived on.

Drawing on her deep knowledge of Iceland and its history and first-hand reading of the original medieval sources, Brown gives us a richly textured narrative, revealing a spellbinding world that continues to fascinate.

Learn more at nancymariebrown.com

Published on October 31, 2012 06:29

October 24, 2012

How to Make a Book Trailer

Song of the Vikings now has a book trailer, thanks to Mrs. Tasha Squires, head of the Learning Resource Center (I want to call it the library) at O’Neill Middle School in Downers Grove, IL.

I’ve never met Mrs. Squires, but I’d like to nominate her for Middle School Teacher of the Year, if there is such a thing, because in about 30 minutes last week she not only taught me how to make a book trailer, but convinced me I could do it.

Here’s the tale: On Tuesday of last week, Elisabeth, my very energetic marketing assistant at Palgrave Macmillan, sent me a message that set fireworks off in my head. The official publication date of Song of the Vikingsis October 30, and we had been working hard to get the word out.

“One opportunity that we can take advantage of,” Elisabeth wrote (due to a situation that will soon be revealed but which I can’t mention yet), “is uploading an author video or book tie-in video”—a book trailer—to the Indiebound independent bookstore site. Elisabeth continued, “I don’t know if you have the means to or are even interested in creating such a video in the next couple of weeks, but I wanted to bring the opportunity to your attention in case you think it’s something you would like to do.”

Now, if you’ve seen a book trailer (and there are lots on YouTube), you probably wondered, as I had, who made them. Back in May, when the final editing was being done on Song of the Vikings, I thought how fun it would be to go to Iceland in the summer and make a video for a book trailer. I wanted to ask my friend Stan Hirson along—he’s a fabulous videographer; you can see samples of his work from Iceland on his websites Hestakaup.com and Life with Horses—and I was sure we could put together something memorable like his video “Longufjörur, the Long Beach,” which is one of my favorites.

But summer sped past, Stan and I never even discussed the idea, and suddenly I have a “couple of weeks” to make a book trailer.

Me, myself, alone. I’m a writer, not a videographer. True, I once worked in radio and used to produce a radio interview program called “Odyssey Through Literature.” (As you can see from the poster image by my friend Jeff Mathison, I was already in love with Vikings.)

Me, myself, alone. I’m a writer, not a videographer. True, I once worked in radio and used to produce a radio interview program called “Odyssey Through Literature.” (As you can see from the poster image by my friend Jeff Mathison, I was already in love with Vikings.) But that was in the 1970s and ‘80s. We used magnetic tape on big 10-inch reels, razor blades, and splicing tape. There was a cool little tray attached to the reel-to-reel deck that flipped down. You listened to the tape, rocking it back and forth until you found exactly the words you wanted to edit out. You made two marks on the tape with a grease pencil, slid the tape into the tray, slit it twice with your razor blade, picked out the “out-take,” let those cast-off words fall to the cutting room floor, and joined the ends together with splicing tape. Then you listened to those few inches of recording several times at different speeds to make sure you couldn’t hear your own edit. I learned a lot about people’s speaking patterns—and what you could make someone say with a deft hand and a razor blade—working on that program.

But I’d never worked in film or video. I’d never done anything like it on a computer. I told Elisabeth a book trailer was a great idea, but it wasn’t going to happen in a “couple of weeks.”

Then I couldn’t sleep. A script popped out of my head the next morning. Much too long, of course, but it was something. I thought maybe Stan had some video in the can that would work. But how would he send it to me? How would I edit it or do the voice-over? A friend of mine who works at Apple had already informed me I could shoot a video using Photo Booth, an application I had on my MacBook and hadn’t ever opened. He insisted I could figure it out. I opened it. I closed it. I dithered.

I couldn’t sleep that night either. I kept seeing my photos of Iceland playing like a film in my head.

The next morning, I googled “How to Make a Book Trailer.” Up came Mrs. Squires’ video, “iMovie Instructions for Book Trailer Video.” I had iMovie on my computer, I discovered. I watched Mrs. Squires’ video. It was 12 minutes and 35 seconds long—and taught me everything I needed to know, including that I needed to watch her earlier video, “Garage Band Instructions for Book Trailer Video,” to learn how to record the voice-over. Yes, I had Garage Band on my computer too.

Step by simple step, Mrs. Squires taught me how to start a project in iMovie and how to drop in my still photos and make them look like video. She taught me how to record my voice-over in Garage Band and how to import it into iMovie. She taught me how to add titles, even background music (and where to find free jingles).

Step by simple step, Mrs. Squires taught me how to start a project in iMovie and how to drop in my still photos and make them look like video. She taught me how to record my voice-over in Garage Band and how to import it into iMovie. She taught me how to add titles, even background music (and where to find free jingles). She did not tell me how to add the video I eventually did shoot in Photo Booth (I will not reveal the number of takes it took). But she gave me the confidence to try to do it, because she told me exactly what I needed to know, in the order in which I needed to know it, and she didn’t tell me anything else. That is the mark of a true teacher. Her videos were clear, simple, and fun.

She didn’t elaborate on all the fancy things iMovie and Garage Band can do. She didn’t try to wow me. She just walked me through the steps to make a book trailer. She even showed me how to fix a mistake—by making one herself. Her “Oops, I made a mistake!” sequence is the part of her video that clinched it: I really could make a book trailer. The fact that Mrs. Squires was explaining a classroom assignment to Middle School students helped. It is so comforting to be allowed to go back to Middle School when we need to.

I’m not sure Mrs. Squires will give my book trailer an “A+.” I can hear my edits. But I hope she’ll give me points for trying.

Learn more at nancymariebrown.com

Published on October 24, 2012 08:31