Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 12

December 11, 2013

The Roskilde Viking Ship Museum

News of the terrible stormsurge that almost washed away the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, earlier this month, brought up memories of my visit there in 2006, when I was researching my book The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman.

News of the terrible stormsurge that almost washed away the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, earlier this month, brought up memories of my visit there in 2006, when I was researching my book The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman.Before then, when I imagined a Viking ship, I thought of the Gokstad ship, which I'm gazing at here in a photo from 1984. Found in the late 1800s in a burial mound in southern Norway, the Gokstad ship has the spareness and elegance of line that seem to me the epitome of a Viking ship. I’m not alone: closeups of its hull, head on, are reproduced on everything from magazine covers to Christmas ornaments as the emblem of the Vikings.

So I was disappointed at first to learn that the ship Gudrid the Far-Traveler sailed on to Vinland in North America did not look like this. Hers was a knarr, a cargo ship, like the replica Saga Siglar that sailed with copies of the Gokstad and Oseberg ships down the coast of North America in 1991. From the Ellis Island ferry, I had watched the three Viking ships sail into New York Harbor, side by side. In my notebook I wrote: "Saga Siglar is so squat and tubby compared to the others. It’s as if someone cut her too short."

Saga Siglar (the name means "Saga Sailor") was based on a ship recovered from the seabottom near Skuldelev, Denmark, by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen, whom I met in 2006 at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde. Tall, fair, white-haired, and smartly dressed in sailor's white, Crumlin-Pedersen had recently retired from the museum that housed his accomplishments: scraps of five Viking ships in five different styles, from a fishing boat to a dragonship, and a dock full of replicas made to their patterns. Nine more ships—found sunk in the museum's own harbor when they were expanding their exhibit space—were then in various stages of processing. One, the largest by far, a slim dragonship that carried up to 40 pairs of oars, is now the centerpiece of the Viking exhibition that just closed in Copenhagen and will be opening in London in the spring.

Photo by Katrin DriscollWith a childlike smile and a courtly bashfulness, Crumlin-Pedersen explained to me how he knew that the tubby model was what the sagas meant by a knarr. "It’s because of the nickname for women in the Icelandic sagas: Knarrarbringu. 'Knarr breast.' Look at it from the front. It comes right up like this—" He pantomimed a woman's tight waist and heavy breasts.

Photo by Katrin DriscollWith a childlike smile and a courtly bashfulness, Crumlin-Pedersen explained to me how he knew that the tubby model was what the sagas meant by a knarr. "It’s because of the nickname for women in the Icelandic sagas: Knarrarbringu. 'Knarr breast.' Look at it from the front. It comes right up like this—" He pantomimed a woman's tight waist and heavy breasts."The replica ships going to Vinland should not be based on Gokstad," he continued, more seriously, "they should be based on this knarr, on Skuldelev 1. Gokstad is a combined sailing and rowing vessel, for a large crew. Skuldelev 1 is definitely a cargo ship. There's only a few oars for turning the ship in the wind or in harbor—it's a pure sailing vessel. Six men, working day and night, could handle it. On the other hand, you could have any number of people on board. You could move a farm with livestock and goods—but you wouldn't take more than one farm. Maybe to go to Vinland you would have wanted a vessel slightly larger than Skuldelev 1, but it would have been this same type of vessel."

The five Skuldelev ships had been scuttled at the head of the fjord to keep raiders from the Danish royal residence at Roskilde. Legend had it that they dated from Queen Margarethe's reign in the 1400s. But when parts of the barricade were removed by fishermen in the 1950s, to clear a deeper passage for their motorboats, Crumlin-Pedersen thought the bits he saw were Viking work. Trained as a maritime engineer, he signed on as a deep-sea diver to map out the wrecks, then, after a stint in the Navy, was hired by the Danish National Museum as a ship archaeologist. The Skuldelev site would be his training ground.

"Underwater archaeology was only just starting then," he told me as we toured the docks and warehouses and hands-on exhibits outside of the museum proper. "I went to the first conferences in Italy and London, and my colleagues tried to convince me that I should come to the warm, clear water of the Mediterranean, not stay in the cold, muddy water here. I insisted in exploring the potential here. It turned out to be very rich.

Photo by Katrin Driscoll

Photo by Katrin Driscoll"We had thought the site was so damaged we could do no harm," he continued. "We had no experience. We could start there and continue on to more important sites. The first year we cleared the passage and found not one, but two ships. The next year, it was not two but four. The next year it was not four but six." (Later they would learn that ships number 4 and 6 were parts of a single widely-scattered vessel.)

"So we built a coffer dam. Sometimes it's a good thing to come from another education. As an engineer, I could come up with ideas and principles for the retrieving of ships that have become standards all over the world."

The coffer dam drained the fjord around the site. Then the problem was to lift the shattered wood out of the mud, while keeping it from drying out and disintegrating. "You keep the wood in water all the time until it can be treated with polyethylene glycol," Crumlin-Pedersen explained. A type of plastic, polyethelene glycol crystallizes within the wood cells. This plasticized wood can then be heated and gently pressed back into shape. "That brings out the lines of the boat."

Those lines are so various, just among the replica ships afloat in Roskilde harbor, that it's hard to say they’re all "Viking ships." The tubby knarr, 52 feet long and a buxom 16 feet wide, is docked beside the dragonship Havhingsten ("The Sea Stallion"), 98 feet long but a slender 12 feet wide. A smaller cargo ship, a byrding of more "elegant" proportions, carried only four-and-a-half tons of cargo to the bigger knarr's 24 tons, while a smaller warship, called a snekke or "snake," could only handle 30 warriors to Sea Stallion's 80.

Photo by Katrin Driscoll

Photo by Katrin DriscollAnd then there's the toy-sized fishing boat, 37 feet long by 8 feet wide, on which Crumlin-Pedersen signed me up as an oarsman when a German TV personality wanted to take a Sunday-morning ride. Nicely maneuverable in the narrow harbor (even with a raw crew brand-new to the oars), it seemed precariously low to the waves once the sail was up. Yet when they compared the pattern of the tree-rings in the original ship's pine timbers to wood samples from throughout the Viking world, they found a perfect match with the wood of the Urnes Stave Church in Sognefjord, Norway; the ship had been built there and had sailed the 500 miles to Roskilde at least once. By the time it was sunk to blockade the fjord, it had been patched in several places and refitted to be a small cargo ship, the rowlocks taken off and an extra strake added to give it a little more height.

All five Skuldelev ship types, Crumlin-Pedersen believes, developed after 900 out of the basic Gokstad style. "The development of cargo vessels seems to be a very late one in Scandinavia," he explained over a lunch of pickled herring and brown bread in the museum’s dockside restaurant (right under which, he pointed out, another longship had been found, 20 feet longer than Sea Stallion). "They didn’t have proper cargo vessels until the 10th century. I think that's because it was too dangerous to go out with a load of valuable cargo without a sufficient number of people to protect your goods. The Gokstad ship was capable of carrying eight to 10 tons of cargo, but also a sufficient crew to defend it. Then in the 10th to 11th centuries, we have the development of cargo ships and the transformation of warships into ships that couldn't carry cargo. I see that as a sign of royal control of the sea. It was one of the main jobs of the king, to keep trade safe."

The cargo ships got tubbier (and more practical), the warships got longer and sleeker and swifter; the principal of their design, according to Crumlin-Pedersen, being the "sporting element": fierce competition among royal Viking crews. One of these late longships is 11 times longer than it is wide and made from enormous oak trees, each thin plank over 32 feet long. "For the really royal ships, the shipbuilder had access to trees no one else could touch," Crumlin-Pedersen told me. "Such a ship as this is an amazing machine!" Racing such a royal ship, he said, must have been the sporting experience of a lifetime.

To read about the Viking Ship Museum's battle with the stormsurge, and see some spectacular photos, go to the museum's website, here: http://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/about-us/news-room/photo-series/billedserie-vikingeskibene-stod-stormen-igennem/#c15886

To read about the Viking Ship Museum's battle with the stormsurge, and see some spectacular photos, go to the museum's website, here: http://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/about-us/news-room/photo-series/billedserie-vikingeskibene-stod-stormen-igennem/#c15886There's also a film about the storm, here: http://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/about-us/news-room/photo-series/billedserie-stormen-time-for-time/film-om-stormen/#c15878

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on December 11, 2013 06:29

December 4, 2013

A Good Horse

This morning, first thing, I went out to feed my horses, as I have done nearly every day for the past 16 years. And as he has done every day for the same period, Birkir from Hallkelsstadahlid was waiting at the tackroom door to greet me, rather impatiently, tugging on the string I use instead of a doorknob so that, as soon as I unlocked the door, it flew open.

This morning, first thing, I went out to feed my horses, as I have done nearly every day for the past 16 years. And as he has done every day for the same period, Birkir from Hallkelsstadahlid was waiting at the tackroom door to greet me, rather impatiently, tugging on the string I use instead of a doorknob so that, as soon as I unlocked the door, it flew open.He grudgingly let me hug him and press my cheek against his warm face. Grudgingly stepped aside to let me unchain the gate to the hay storage. Tentatively followed me in to snatch a bite of hay and, shamefacedly, backed up to let me carry a few flakes out into the paddock to spread for him and the other horses.

He is always the same, Birkir: his great, brown, kind eye, his carefulness in keeping as close to me as possible without jostling me or stepping on my toes.

I remembered the day I bought him, in the summer of 1997, my first horse. I wrote about it in my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color , published in 2001 and just out this year in paperback.

I had ridden Birkir for 15 minutes, in the rain. I bought him from Sigrun of Hallkellstadahlid in western Iceland on the advice of a farmer friend known to have "an eye for horses." I have never regretted it. An Icelandic horse trainer once told me, "If I had a stable of horses like Birkir, I would be a rich woman."

I have only one, and I am a rich woman.

Here is what I wrote, so many years ago:

The rain was still steady, but inside the barn it was warm and brightly lit and comforting. A raised center aisle separated two large pens full of horses, each haltered and clipped to a rail. They stirred and stamped when we entered, and I looked along their orderly ranks for Birkir. Amazingly, I picked him out at once, the light bay with a star, and walked down the aisle toward him feeling as if he were already mine. Sigrun approached him from the rear, and the horses parted, leaving room for me to step into the pen and join her. We stood at his flank, looking him over, and he turned his head to watch us, his neck arced high, his ears pricked with curiosity. He had a dark, liquid, inquisitive eye, soft and friendly. Unlike Elfa, he was completely at ease around us. He did not sidle away when I reached to pat him--on the contrary, he poked his nose forward, doglike, to the limits of his rope, as if looking for attention. I scratched behind his ears and ran my hand down his neck and along his smooth wide back. His mane and tail were thick and dark, his black stockings neat, his hooves well-shaped, his coat a glowing red. He seemed larger and sturdier than most Icelandics I'd seen, and it was clear he was in excellent health.

The rain was still steady, but inside the barn it was warm and brightly lit and comforting. A raised center aisle separated two large pens full of horses, each haltered and clipped to a rail. They stirred and stamped when we entered, and I looked along their orderly ranks for Birkir. Amazingly, I picked him out at once, the light bay with a star, and walked down the aisle toward him feeling as if he were already mine. Sigrun approached him from the rear, and the horses parted, leaving room for me to step into the pen and join her. We stood at his flank, looking him over, and he turned his head to watch us, his neck arced high, his ears pricked with curiosity. He had a dark, liquid, inquisitive eye, soft and friendly. Unlike Elfa, he was completely at ease around us. He did not sidle away when I reached to pat him--on the contrary, he poked his nose forward, doglike, to the limits of his rope, as if looking for attention. I scratched behind his ears and ran my hand down his neck and along his smooth wide back. His mane and tail were thick and dark, his black stockings neat, his hooves well-shaped, his coat a glowing red. He seemed larger and sturdier than most Icelandics I'd seen, and it was clear he was in excellent health."He's beautiful," I said, and meant it. I was filled with desire, suddenly, to own this beast--filled with awe that it was possible to own a creature so fine, so alive--surprised that anyone would actually let me take him away...

Photo of Birkir by Jennifer Anne Tucker and Gerald Lang

Photo of Birkir by Jennifer Anne Tucker and Gerald LangIn May 2014, the trekking company America2Iceland is organizing a riding tour in Iceland for people who want to buy--or just learn how to buy--an Icelandic horse. They're calling it the "Good Horse Has No Color" tour and have invited me along to share how I chose Birkir and Gaeska, the two stars of the book, in 1997. I'm not entirely sure what they want me to do--we have the winter to work it out. Or how to explain what it was that I saw in Birkir, at five years old, and see now that he is 21, every morning when I come down to the barn and he's tugging on that string to let me in.

A wise Icelandic friend told me once that it's best when the horse chooses you. I'm grateful that Birkir did.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on December 04, 2013 11:57

November 27, 2013

Turf Houses and Hobbit Holes

Whenever I see an Icelandic turf house, especially from the back, I think of the opening of Tolkien's The Hobbit:

Whenever I see an Icelandic turf house, especially from the back, I think of the opening of Tolkien's The Hobbit:"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort."

When I first went to Iceland, I wondered why it seemed so familiar. Then I learned that Tolkien had read William Morris's journal of his travels to Iceland in 1873 and used them as the basis for much of the hobbit Bilbo Baggins's quest.

Morris's view of an Icelandic turf house, though, was that of a guest. "We are soon all housed in a little room about twelve feet by eight," he writes, "two beds in an alcove on one side of the room and three chests on the other, and a little table under the window: the walls are panelled and the floor boarded; the window looks through four little panes of glass, and a turf wall five feet thick (by measurement) on to a wild enough landscape of the black valley, with the green slopes we have come down, and beyond the snow-striped black cliffs and white dome of Geitland's Jokul."

Quaint and pretty, it seems--with a little imagination, it could be a hobbit hole.

But what was it really like to live in a turf house?

When I was in Iceland earlier this month, I picked up a book by the writer Thórbergur Thórdarson that has just come out in English translation as The Stones Speak. Thórbergur was born in 1888 in a remote part of the country. He moved to Reykjavik in 1906, became a schoolteacher, and in 1924 published a novel, Bréf til Láru (or, Letter to Lára) that "became an overnight sensation," says translator Julian Meldon D'Arcy. (The book also got him fired from his teaching job.) Thórbergur is now considered "as important an author in the Icelandic canon as his friend, the contemporary novelist and Nobel Prize winner Halldór Laxness," D'Arcy says.

When I was in Iceland earlier this month, I picked up a book by the writer Thórbergur Thórdarson that has just come out in English translation as The Stones Speak. Thórbergur was born in 1888 in a remote part of the country. He moved to Reykjavik in 1906, became a schoolteacher, and in 1924 published a novel, Bréf til Láru (or, Letter to Lára) that "became an overnight sensation," says translator Julian Meldon D'Arcy. (The book also got him fired from his teaching job.) Thórbergur is now considered "as important an author in the Icelandic canon as his friend, the contemporary novelist and Nobel Prize winner Halldór Laxness," D'Arcy says.The Stones Speak tells of his childhood living in a turf house in Suðursveit, about 400 kilometers east of Reykjavik near the beautiful national park of Skaftafell. If you want to get an idea of what it was like to live in Iceland in the early 1900s, this is the book to read.

Here is how he describes his home:

"Its three houses stood next to each other in a row with their peaked front gables facing south and their sterns toward the mountain. It was a pleasure to see them from the home field below standing side by side like that, as if they were taking care of each other, and it was easy to see that they all got on well together. When it started to grow dark it was as if they slept all huddled up as one."

It's characteristic of Thórbergur's writing style to infuse the houses with feeling, as if they were alive--as if they, like the stones of the title, the paving stones outside his front door, could speak. What stories they could tell if only we would listen!

Yet for all the warmth with which he looks back on his childhood home, Thórbergur's eye is sharp. One of my favorite passages in The Stones Speak describes the kitchen, warmed by its fire of sheep dung:

Yet for all the warmth with which he looks back on his childhood home, Thórbergur's eye is sharp. One of my favorite passages in The Stones Speak describes the kitchen, warmed by its fire of sheep dung:"The first thing you saw when you came in through the kitchen passageway, after you'd just carried in the dung, was the dung screen. This was a high wall made from stacked sheep droppings at the front of the dung heap to prevent the heap from tumbling all over the floor. The screen reached right across the kitchen, from wall to wall, a short distance from the fireplace. I thought it was beautiful. It made quite an artistic impression on me seeing the droppings regularly stacked up like cards on top of each other and side by side in a high and broad wall. And when the fire blazed brightly in the fireplace, a living glow flickered on this screen in different shades and tones. It was a poem in living colours. What a pleasure it was to look at, it was as if something delightful was aroused deep inside me as I stood and gazed at it."

A pile of sheep shit--is a "poem in living colours"! Thórbergur's description made me laugh. He is writing as the older and wiser man looking back on his naive childish self and, of course, he means to make me laugh. But he also means to make me think. Here in Vermont we heat with wood, not sheep dung, and those who stack the wood also take pride in their work. I could probably even find one or two who would describe their woodstacks as poems.

Another key feature of Thórbergur's kitchen was its rather temperamental smoke vent: When the wind changed, someone had to climb up onto the kitchen roof to reposition the vent.

Writes Thórbergur:

Writes Thórbergur:"In good weather it was always nice to get up onto the front wall of the kitchen. From there the whole of existence was a little different from down on the paved forecourt. The home field became broader and so did the Lagoon. Breiðabólsstaður and Gerði and the sheepcotes and stables on the home field seemed lower. You could see further out over the sea and west to the Breiðamerkursandur gravel plain. Hrollaugseyjar isles were a little further from land, and the folk and the dog on the forecourt became smaller while you yourself became bigger. That's life for you. When you yourself become big, others become small."

The Stones Speak by Thórbergur Thórdarson was published in 2012 by Mál og Menning, an imprint of the publisher Forlagið. You can buy it from the publisher's website, here: http://www.forlagid.is/?p=601952

The first two turf-house photos accompanying this blog are of the farmhouse in the Skagafjordur Heritage Museum at Glaumbær--about as far from Thórbergur's Suðursveit as you can get and still be in Iceland--but one of the best-preserved turf houses in the country. Learn more about it at: http://www2.skagafjordur.is/default.asp?cat_id=1123

The last one is from the Skogar Folk Museum in south Iceland: http://www.skogasafn.is. I wrote about visiting both Skogar and Glaumbær in June in "An Icelandic Horse(hair) Tale": http://www.nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2013/06/an-icelandic-horse-hair-tale.html

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on November 27, 2013 03:54

November 19, 2013

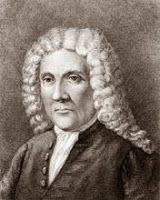

The Saga Man: Arni Magnusson

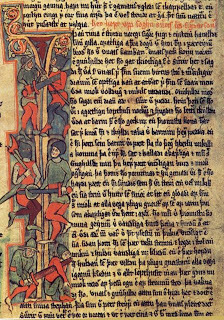

Lovers of Icelandic sagas are celebrating these days: It's the 350th birthday of Arni Magnusson, the man who, more than anyone else, saved Iceland's medieval manuscripts.

Lovers of Icelandic sagas are celebrating these days: It's the 350th birthday of Arni Magnusson, the man who, more than anyone else, saved Iceland's medieval manuscripts.Brought up at Snorri Sturluson’s ancestral estate of Hvamm in the west of Iceland, Arni went to Copenhagen in 1683, when he was 20 years old, and found work as a copyist and translator for Thomas Bartholin, Jr. With Arni's help, Bartholin published a 700-page history of the Danes in 1689. Drawing examples from Snorri’s Heimskringla, Egil’s Saga, and other sagas, Bartholin’s Danish Antiquities Concerning the Reasons for the Pagan Danes’ Disdain for Death made popular the Viking stereotype of the bold, blond, laugh-in-the-face-of-death hero.

Arni became a professor at the University of Copenhagen in 1701, and the next year the king sent him back to Iceland to gather statistics on his country’s land and people. His massive Land Register, compiled over ten years, describes every farm in Iceland, its size and shape, buildings, people, cows, sheep, horses, the bulk of butter and cloth it owed in tithes, the quality of its turf, peat, hay, and woodlots, its fishing and driftwood rights, and the extent of the property ruined by volcanic ash or sand or rendered useless by quagmires, bogs, erosion, or flooding.

Off the record, Arni asked every farmer about manuscripts—and poked about in every farmhouse. In his novel Iceland's Bell, Halldor Laxness imagines Arni searching every nook and cranny, even the stuffing of the mattress:

Off the record, Arni asked every farmer about manuscripts—and poked about in every farmhouse. In his novel Iceland's Bell, Halldor Laxness imagines Arni searching every nook and cranny, even the stuffing of the mattress:Dust and poison gushed up from the old and moldy hay within the woman’s bed as they began their search. Mixed up in the hay was all kinds of garbage, such as bottomless shoe-tatters, shoe-patches, old stocking legs, rotten rags of wadmal, pieces of cord, fibers, fragments of horseshoes, horns, bones, gills, fishtails hard as glass, broken wooden bolts and other scraps of wood, loom-weights, shells both flat and whorled, and starfish.

There were often also scraps of parchment in hiding places like this: Arni collected every one. He found two leaves from a 13th-century manuscript with holes punched in them to make a flour sifter. He found sheets used as dress patterns, shoe soles, knee patches, and even the stiffening in a bishop’s mitre. He pieced them back into books: One 60-page manuscript came from eight different farms.

When Arni's collection was packed for shipping to Copenhagen in 1720, it filled 55 wooden chests and required 30 packhorses to carry it.

Then in 1728 Copenhagen caught fire. Half of the city was incinerated, including the university library. Arni, disbelieving that fate could be so cruel, refused to evacuate his private library until the fire reached the end of his street. He and two other Icelanders had time to rescue only the oldest books. The rest were lost, including, Arni cried, “books that will never and nowhere be found until doomsday.”

Then in 1728 Copenhagen caught fire. Half of the city was incinerated, including the university library. Arni, disbelieving that fate could be so cruel, refused to evacuate his private library until the fire reached the end of his street. He and two other Icelanders had time to rescue only the oldest books. The rest were lost, including, Arni cried, “books that will never and nowhere be found until doomsday.”We can only guess what wonderful sagas they held.

But the rest of Arni's collection now fills two libraries named for him, the Arni Magnusson Institute in Iceland and the Arnamagnaean Institute in Copenhagen. The Icelandic one held its birthday celebration last week; Copenhagen's is coming up on Friday. (For details see http://nfi.ku.dk/kalender/arne350-seminar/) I'm looking forward to tipping a glass to Arni's memory.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on November 19, 2013 23:25

November 12, 2013

A Visit to Thingvellir

On a sunny day in Iceland, when I'm traveling east out of Rekjavik, it's almost impossible not to detour to Thingvellir, as I did last week.

On a sunny day in Iceland, when I'm traveling east out of Rekjavik, it's almost impossible not to detour to Thingvellir, as I did last week.Approaching these Assembly Plains in 1871, William Morris wrote, "My heart beats, so please you, as we near the brow of the pass, and all the infinite wonder, which came upon me when I came up on the deck of the [ship] to see Iceland for the first time, comes on me again now, for this is the heart of Iceland…"

In spite of his flowery Victorian prose style, Morris speaks for me too: My heart does beat faster when I see the great rift valley of Thingvellir beside its deep blue lake.

Here is where the tectonic plates are pulling apart, America getting infinitesimally farther from Europe with each passing year.

And here, on the tenth Thor's Day of summer each year from 930 to 1262, Icelands chieftains and their wives and children and followers gathered for the Althing, the General Assembly of all Iceland.

In the medieval Icelandic sagas--what Morris familiarly calls "those old stories"--the Althing is a grand party. Thousands of people stayed for two weeks in tents and turf-walled booths on the banks of the Axe River, drinking ale, telling tales, taking part in horse fights and wrestling matches, races and dice games, making wedding plans or finalizing divorces, witnessing court cases, and wrangling over the law.

Disputes between Icelanders of any rank could be settled at the Althing, by appeal to Iceland's laws. There was no king to enforce the laws. Instead, there were five law courts: one for each quarter of the country plus an appeals court, each with 36 judges. The judges were chosen by the chieftains, each chieftain being allowed to nominate or to veto a certain number.

Presiding over the courts was Iceland's only elected official, the Lawspeaker. The first Lawspeaker brought the laws of western Norway to Iceland in 930. For nearly two hundred years, until 1118, the Lawspeaker recited from memory one third of the law code at each Althing. After that, the laws were read aloud from a lawbook.

The place where he stood to recite, the Law Rock, is marked now by a flagpole. (Notice that the flag is hanging limp. It's almost never this calm in Iceland.) This height of land, with its backdrop of columnar basalt, formed a natural amphitheatre. The chieftains gathered below the Law Rock and, after the recitation, the laws were debated, adjusted, and agreed upon for, as it says in Njal's Saga, "With laws shall our land be built up, but with lawlessness laid waste."

There were laws concerning stolen horses, rented cows, dogs that bit, or bulls that ran amok in the neighbor's haystacks. There were laws about betrothals and divorces, buying sheep or claiming debts. There were laws concerning the welfare of orphans, widows, the sick, the handicapped, and the poor. There were laws about renting land or investing in a trading ship. There were numerous laws defining murder and homicide, setting the compensation a killer should pay the victim's family if he hoped to avoid being exiled from the island.

Of course, not everyone followed the laws and not every feud was peacefully settled. One of the great themes of the Icelandic sagas is what happens when someone defies the law.

Of Iceland in general, William Morris wrote, “It is an awful place: set aside the hope that the unseen sea gives you here, and the strange threatening change of the blue spiky mountains beyond the firth, and the rest seems emptiness and nothing else: a piece of turf under your feet, and the sky overhead, that's all; whatever solace your life is to have here must come out of yourself or these old stories, not over hopeful themselves."

Iceland is indeed an awful place: a place that fills me with awe. "Whatever solace your life is to have here must come out of yourself or these old stories." Is it different anywhere else?

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland of the medieval world.

Published on November 12, 2013 22:26

November 6, 2013

Touring Saga Land

I'm in Iceland, for the 18th time, to learn more about the sagas. And although today is a library day (gray skies, spitting rain, fierce wind), I'm hoping to visit some saga sites over the weekend. I might rent a car, or even take a bus tour.

I'm in Iceland, for the 18th time, to learn more about the sagas. And although today is a library day (gray skies, spitting rain, fierce wind), I'm hoping to visit some saga sites over the weekend. I might rent a car, or even take a bus tour.When I first went to Iceland in 1986, saga tourism was minimal. I, like many writers before and since, wanted to see the places made vivid and unforgettable by the medieval authors:

Where Njal and his wife, their house afire, their enemies surrounding it, refused to come out. Said Njal, "I am an old man now and ill-equipped to avenge my sons; and I do not want to live in shame." Said Bergthora, "I was given to Njal in marriage when young, and I have promised him that we would share the same fate."

Where Gunnar's horse stumbled and he spoke the famous lines, "How lovely the slopes are, more lovely than they have ever seemed to me before, golden cornfields and new-mown hay. I am going back home, and I will not go away."

But these places were on working farms and the farmers, understandably, treasured their privacy. I passed by on the main road, looked from afar, was never quite sure I'd found the right spot.

Now, I'm happy to say, there's a museum devoted to Njal's Saga at Hvolsvöllur [www.njala.is] in southern Iceland, offering exhibits and guided tours to the saga sites. There's even a community-wide activity, embroidering the Story of Burnt Njal in the style of the Bayeux tapestry.

In fact, according to an Icelandic publication called The Museum Guide 2013, there are currently 134 museums in Iceland--for a population of 320,000. Can you imagine 134 museums in Pittsburgh, PA or St. Louis, MO? Of these 134, by my count 11 focus on the sagas or the Viking Age.

In addition to the Saga Centre in Hvolsvöllur, one of my favorites is the Settlement Centre in Borgarnes in western Iceland. [www.settlementcentre.is] One of its exhibits explores the settlement of Iceland between 870 and 930, as told in the sagas; the other tells the story of Egil's Saga through renderings by modern artists. An audio guide for your smartphone allows you to drive around the vicinity and find the places mentioned in the saga.

In addition to the Saga Centre in Hvolsvöllur, one of my favorites is the Settlement Centre in Borgarnes in western Iceland. [www.settlementcentre.is] One of its exhibits explores the settlement of Iceland between 870 and 930, as told in the sagas; the other tells the story of Egil's Saga through renderings by modern artists. An audio guide for your smartphone allows you to drive around the vicinity and find the places mentioned in the saga.Such as the farm of Borg, where Egil, depressed, lay down to die after the drowning of a beloved son. One of his daughters craftily revived his will to live by getting him to make a poem about it, the beautiful “Lament for My Sons”: My mouth strains To move the tongue, To weigh and wing The choice word: Not easy to breathe Odin’s inspiration In my heart’s hinterland, Little hope there…

The poem is as much about poetry, the “purest of possessions,” the “word-mead,” as it is about the dead boy. “Now I feel it surge, swell / Like a sea, old giant’s blood.” As he created the poem, the saga says, “Egil began to get back his spirits.” When it was finished, he took his seat in the hall and declaimed the lament before all the family.

A little further inland is Snorrastofa [www.snorrastofa.is], a museum, library, and research centre named for the 13th-century writer Snorri Sturluson on the site of his estate, Reykholt. Snorri may have written Egil's Saga. He is better known as the author of Heimskringla, a set of 16 sagas that contain almost everything we know about the history of Norway from its foundation to 1177. His masterpiece, though, is the Edda, which is our major (and sometimes our only) source for the stories of Norse mythology.

A little further inland is Snorrastofa [www.snorrastofa.is], a museum, library, and research centre named for the 13th-century writer Snorri Sturluson on the site of his estate, Reykholt. Snorri may have written Egil's Saga. He is better known as the author of Heimskringla, a set of 16 sagas that contain almost everything we know about the history of Norway from its foundation to 1177. His masterpiece, though, is the Edda, which is our major (and sometimes our only) source for the stories of Norse mythology. In my biography of Snorri, Song of the Vikings, I imagine him in the hot-tub at Reykholt, regaling his friends with the story of Odin's eight-legged horse, Sleipnir:

One day while Thor was off fighting trolls in the east, a giant entered the gods’ city of Asgard. He was a stonemason, he said, and offered to build the gods a wall so strong it would keep out any ogre or giant or troll. All he wanted in return was the sun and the moon and goddess Freya for his wife. The gods talked it over, wondering how they could get the wall for free. “If you build it in one winter, with no one’s help,” the gods said, thinking that impossible, “we have a deal.” “Can I use my stallion?” the giant asked. Loki replied, “I see no harm in that.” The other gods agreed. They swore mighty oaths. The giant got to work. By night the stallion hauled enormous loads of stone, by day the giant laid them up. The wall rose, course upon course. With three days left of winter, it was nearly done. “Whose idea was it to spoil the sky by giving away the sun and the moon—not to mention marrying Freyja into Giantland?” the gods shouted. They wanted out of their bargain. “It’s all Loki’s fault,” they agreed. “He’d better fix it.” Loki transformed himself into a mare in heat. That evening, when the mason drove his stallion to the quarry, his horse was uncontrollable. It broke the traces and ran after the mare. The giant chased after them all night and, needless to say, he got no work done. Nor could he finish the wall the next day with no stone. His always-edgy temper snapped. He flew into a giant rage. The gods’ oaths were forgotten. Thor raised his terrible hammer and smashed the giant’s skull. Eleven months later, Loki had a foal. It was grey and had eight legs. It grew up to be the best horse among gods and men.

There's a wonderful exhibition about Snorri Sturluson's life and art at Reykholt now. Last June I spent a good hour or two going through it with a group of tourists from the horse-trekking company America2Iceland. I had very few quibbles with the text--not surprising, since it was written by Óskar Guðmundsson, whose masterful 2009 biography, Snorri: Ævisaga Snorra Sturlusonar 1179-1241, inspired me to write Song of the Vikings.

There's a wonderful exhibition about Snorri Sturluson's life and art at Reykholt now. Last June I spent a good hour or two going through it with a group of tourists from the horse-trekking company America2Iceland. I had very few quibbles with the text--not surprising, since it was written by Óskar Guðmundsson, whose masterful 2009 biography, Snorri: Ævisaga Snorra Sturlusonar 1179-1241, inspired me to write Song of the Vikings. We dipped our fingers in Snorri's hot-tub, before mounting our horses to continue our week-long trek through the countryside of Borgarfjord. Yes, you guessed it, I am now leading saga tours myself. They're not precisely the kind of tours I was looking for in 1986--but I hadn't discovered the joys of riding Icelandic horses back then. If you'd like to join me in 2014, visit America2Iceland.com and put your name on the list.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on November 06, 2013 03:11

October 30, 2013

Icelandic Witchcraft

On the way to Strandagaldur, the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft, I had a panic attack. Getting to our B&B at Kirkjubóll was grueling: in and out of deep fjords, sometimes a paved road, sometimes gravel, sometimes two lanes, sometimes one, wind buffeting our tiny rental car, sun glare, traffic passing, pushing, campers and cars, and a sheer, sheer drop off to the sea far below, without even a white line to mark the edge of the road. It was tiring and took concentration to keep an eye on the road and not be distracted by the striking landscape or be pulled off into the void by that sheer, unmarked edge.

On the way to Strandagaldur, the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft, I had a panic attack. Getting to our B&B at Kirkjubóll was grueling: in and out of deep fjords, sometimes a paved road, sometimes gravel, sometimes two lanes, sometimes one, wind buffeting our tiny rental car, sun glare, traffic passing, pushing, campers and cars, and a sheer, sheer drop off to the sea far below, without even a white line to mark the edge of the road. It was tiring and took concentration to keep an eye on the road and not be distracted by the striking landscape or be pulled off into the void by that sheer, unmarked edge.Did I mention I'm afraid of heights?

At a headland I pulled over between two campers (whose drivers were peeing over the edge) and my traveling companion, Jenny, pulled out her handy bottle of Rescue Remedy, a mix of herbs and vodka. Two drops on my tongue did the trick. My hands came uncramped from the wheel. I began to breath again.

Jenny is an herbalist. In Iceland when I introduced her, my friends would nod and whisper among themselves. Suddenly their faces lit up in a smile. "Oh, she's a witch!" And she did cure a little girl of the night terrors by giving her a potion and a posey to put under her pillow. Truly.

Jenny's also a photographer, trained to see things differently. A perfect person to take to the Westfjords to see the witchcraft museum, someone's brilliant idea to lure tourists to an incredibly bleak part of Iceland with hair-raising roads.

When we reached our night's lodging, Jenny made herb tea from some leaves she picked behind the house. We took a stroll on an arc of black beach into the teeth of the wind, the late evening sun behind a mountain--this was June--bundled up in sweaters and scarves and ear-warmers (we could have used long underwear), singing, and picking up mussel shells, orange scallops, broken conchs, driftwood, feathers, sea urchins, while the arctic terns and oystercatchers and razorbills strafed us, shrieking. Suddenly, I was ecstatic: waves and mountains with snow on them, bird cries, cold. It was magic.

When we reached our night's lodging, Jenny made herb tea from some leaves she picked behind the house. We took a stroll on an arc of black beach into the teeth of the wind, the late evening sun behind a mountain--this was June--bundled up in sweaters and scarves and ear-warmers (we could have used long underwear), singing, and picking up mussel shells, orange scallops, broken conchs, driftwood, feathers, sea urchins, while the arctic terns and oystercatchers and razorbills strafed us, shrieking. Suddenly, I was ecstatic: waves and mountains with snow on them, bird cries, cold. It was magic.The next morning we drove to the town of Hólmavík in misty low cloud, over a gravel road between banks of old snow--it really was June--and a few brave tussocks of flowering lamb's-grass and bilberry. We passed more black-sand bays littered with driftwood logs. Someone had pulled them from the tide and sorted them by size. Also ropes, nets, pallets, and flat building panels. We passed a road sign that said "I." Jenny decided it meant, not "Information," but "Isolation."

Hólmavík is a very small town, even for Iceland. There's a gas station, a bank, a health clinic, and Strandagaldur, the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft, which itself is very small but beautifully designed by Árni Páll Johannsson, who also designs movie sets. The exhibits are evocative, the descriptions informative, with a good mix of "wow" displays and deep scholarly stuff (reproductions of manuscript pages, maps, timelines, genealogies).

The English audio-guide took about an hour and focused mostly on who the witches were and why they were singled out. Their stories were well-told: You could draw your own conclusions about their magic powers and were sympathetic to these 20 men and 1 woman who were burned at the stake in the late 1600s for being different. Many were the victims of one rich woman, the sheriff's wife, who accused someone of witchcraft every time she got sick. In another case, the priest was awarded "compensation" for any acts of witchcraft in his parish--meaning he got to confiscate all the witch's property. Quite an incentive to accuse a neighbor of working black magic. I bought the book Angurgapi: The Witch-hunts in Iceland by Magnús Rafnsson to learn more.

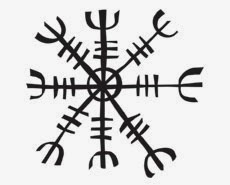

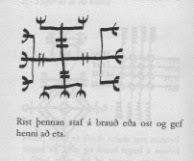

Then there's the magic itself, with lots of spells written in runes. I bought a booklet of Love Spells. Here's one:

It says you are supposed to carve this design on a piece of bread and cheese and give it to your beloved to eat. A sure way to his or her heart.

Other spells will make your sheep docile or give them twin lambs, protect them from being drowned in floods or keep foxes away, make fish jump onto your hooks, keep a scythe sharp, and strengthen your rowing or wrestling or grass-mowing skill.

Still other spells will prevent theft, kill an enemy's horse, or just break its leg. To keep visitors away, according to another booklet published by the museum, carve this rune stave

on a piece of rowan wood when the sun is at its zenith. Walk three times around the house the way the sun turns and three times widdershins (the opposite way) holding the carved rowan stick in one hand and "sharp thorn grass" in the other. Then lay both of them on the gable above your house door.

The rune stave at the head of this blog post, the Helm of Awe or Ægishjálmur, used as the museum's logo, induces fear and protects you against abuses of power--if you carve it in lead and press it on your forehead.

The grisliest (and most popular) magic item on view at the museum was the pair of corpse-skin trousers or "necropants" that promise to make you rich. You can see a video about them here on their website [click here].

Here's how to make them, according to the website--be sure to get permission first!

If you want to make your own necropants (literally, nábrók), you have to get permission from a living man to use his skin after his death. After he has been buried, you must dig up his body and flay the skin of the corpse in one piece from the waist down. As soon as you step into the pants, they will stick to your own skin. A coin must be stolen from a poor widow and placed in the scrotum along with this magical sign

written on a piece of paper. Consequently the coin will draw money into the scrotum so it will never be empty, as long as the original coin is not removed.

If you want to go to heaven after you die, however, you have to be sure to pass your necropants on to someone else while you're alive (and still rather flexible): That person has to step into each leg of the skin as soon as you step out of it. The necropants can thus keep a family in riches for generations.

Note that, despite what you might have read elsewhere on the internet (such as at the International Business Times, here), the necropants in the museum are plastic fakes, not "dead human skin on display," as that headline claims. The article itself is clear: "just a replica, according to The Huffington Post." (The headline at HuffPo also screams: "Necropants, Made from Dead Man's Skin…" Told you this was the most popular exhibit.)

The Sorceror's Cottage was a good second act. "Let there be mist and mischief," said a witch from these parts in the most famous of the medieval Icelandic sagas, Njal's Saga. We drove about an hour farther to see the cottage, through mist, on rocky, bumpy, scary roads, and encountered more than enough mischief in the form of a strange knocking sound from beneath our car that sounded like we were dragging a body--but when we stopped to look nothing was there. Might have been a stone in the wheel-well. We hoped so, at least.

The Sorceror's Cottage is a very rough turf-house of the poorest sort, a low-ceilinged, dirty hovel with a pen for the sheep next to two beds for the people. Again, it was very realistically recreated, stocked with 17th-century tools and rough, hooded robes. The curator wisely told us to go through the house twice: look, read the text, then look again.

The Sorceror's Cottage is a very rough turf-house of the poorest sort, a low-ceilinged, dirty hovel with a pen for the sheep next to two beds for the people. Again, it was very realistically recreated, stocked with 17th-century tools and rough, hooded robes. The curator wisely told us to go through the house twice: look, read the text, then look again. When there are more than two tourists, the curator puts on her witch's robe and acts the part. With us she simply shared the story of the three trolls who tried to separate the Westfjords from the rest of Iceland so they could escape the awful ringing of the church bells. She gave us directions to the rock stacks the trolls turned into when the sun rose and caught them at their work.

We went to find them and had a picnic beside one troll, a tall, black slab of columnar basalt laid up sideways like a stack of firewood, the size of a house but only about 6 feet thick. It stood on a grassy lawn between the swimming pool and some guest cottages at the hamlet of Drangsnes. On the way there we had passed the other two trolls, standing at the tip of a rocky headland with their feet in the sea.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on October 30, 2013 06:43

October 23, 2013

A 10th-century Monk in the Caliph's Court

Researching my book The Abacus and the Cross, I discovered several facets of the Viking Age that I hadn't been aware of. One was the intersection of faith and science in Islamic Spain: as I mentioned in

Researching my book The Abacus and the Cross, I discovered several facets of the Viking Age that I hadn't been aware of. One was the intersection of faith and science in Islamic Spain: as I mentioned in The story of John of Gorze shows just how tolerant it could be.

The story begins with an embassy sent north by the Caliph Abd al-Rahmann III. The Holy Roman Emperor was pleased with the caliph's exotic gifts, but the caliph's letter confounded Otto the Great. Like his peers, the Holy Roman Emperor found Islam incomprehensible. Muslims worshipped the One God. They revered the patriarchs, the Virgin Mary—even Jesus, though they denied he was the Son of God. They “read the Hebrew prophets (or rather, those of the Christians),” noted the 11th-century chronicler Ralph the Bald, “claiming that what they foretold concerning Jesus Christ, Lord of all, is now fulfilled in the person of Muhammad, one of their people.” What could it be, the emperor and his rather narrow-minded counselors asked, but a Christian heresy?

Complicating the emperor’s response even further was the fact that Abd al-Rahman’s ambassador had died. Otto needed a messenger who was tough and expendable. John of Gorze volunteered.

The Life of John, Abbot of Gorze was written between 974 and 984 by a monk to whom he had told his stories. John’s toughness is amply illustrated, as is his narrow-mindedness. John's rich father, nearing ninety, married a young noblewoman; he begat three sons before he died. John was raised to be his father's heir and, as an adolescent, found himself in charge of vast estates.

He managed them well until one day, visiting a nunnery from which he rented a manor, he saw a beautiful girl. Her rosy skin was revealed by the fine garment she wore, but just at her bosom was an ugly tangle of something. Curious (and used to getting his own way), John slipped his hand down her dress. Touching that awful roughness, he began trembling with horror. It was a hair shirt. The girl, blushing, said, “Do you not know that we do not live for this world?”

From then on, John wanted to be a monk, the more ascetic the better. Finding a sufficiently rigorous monastery at Gorze, he donated all his wealth—beggaring his two brothers, who had to become monks as well. He outdid the other monks in depriving himself of food, clothing, baths, soft beds, or comfort of any sort. Finding he enjoyed the study of logic, he vowed to read nothing thenceforth but scripture.

As the emperor’s ambassador, John traveled to Barcelona in 953 with French slave-traders who were ferrying Slavic captives to Cordoba to be sold as eunuchs. He stayed two weeks with Count Borrell, a Christian ally of the caliph’s, who sent a warning south.

As the emperor’s ambassador, John traveled to Barcelona in 953 with French slave-traders who were ferrying Slavic captives to Cordoba to be sold as eunuchs. He stayed two weeks with Count Borrell, a Christian ally of the caliph’s, who sent a warning south.Reaching Cordoba, John was stopped two miles from the palace and escorted to a house. There he stayed as a pampered guest for three years—for the contents of Emperor Otto’s letter were known to the caliph, thanks to the count of Barcelona. Though we can only guess at what the emperor said about Islam, it was clearly offensive: According to the laws of al-Andalus, anyone repeating such things about the Prophet Muhammad must be put to death.

Rather than bring things to that extreme, the caliph sent his Jewish vizier, Hasdai ibn Shaprut, to explain the problem to John of Gorze. “Our people attest that they have never met nor heard of a wiser man,” says The Life of John. Why not destroy the letter, Hasdai suggested, and just present the emperor's gifts? John refused to disobey the emperor, but suggested that perhaps he should send to Otto asking for new instructions.

The caliph’s Christian vizier, Bishop Racemundo, volunteered to go north. He was “a good catholic,” says The Life of John, with “an important function at court.” He was “perfectly instructed in our culture as well as in that of the Arab language.” He arrived at Gorze in six weeks and rested there until after Christmas, when he was presented to Emperor Otto at Frankfurt.

In Frankfurt, Racemundo met the nun Hrosvit of Gandersheim, then only 15 or 20 years old. She would become well known for her comedies, written in the style of Terence, in which self-confident little Christian girls make fun of the pagan fools who martyr them.

Hrosvit recorded her conversation with Racemundo in a poem about a young Christian killed for blaspheming against the Prophet Muhammad. Though her understanding of Islam was warped and her depiction of Abd al-Rahman not complimentary, she does accurately convey Cordoba’s religious tolerance. The caliph issued a pronouncement, she writes, that said: “Whoever so desired to serve the Eternal King,” meaning Christ, “and desired to honor the customs of his sires, might do so without fear of any retribution. Only a single condition he set to be observed, namely that no dweller of the aforesaid city should presume to blaspheme” the prophet Mohammed's name. This was the problem Racemundo had come to Otto’s court to solve.

Racemundo returned to Cordoba in June, bringing a “less severe” letter and instructions from Emperor Otto the Great for John of Gorze to negotiate peace. After three years of waiting, John was brought to the caliph’s palace. The Life of John describes the armed guards along the route: the knights on their fine horses, the scary-looking black soldiers. It notes the precious rugs and tapestries in the palace and, in the throne room, the “extraordinary curtains, which made the walls look sunlit.” As an Arabic writer explains, the walls were paneled with gold and in the middle of the room was a pool of quicksilver—mercury—off which the sunlight bounced. At a sign from the caliph, his slaves would vigorously stir it, setting off lightning flashes that induced vertigo in his terrified petitioners.

Abd al-Rahman, lounging on a divan, offered John a chair and apologized for not seeing him sooner. John praised the caliph for his “constant heart” and “measured wisdom.” They discussed kingship. The caliph said he thought Emperor Otto was imprudent: He gave his underlings too much power—and at that point The Life of John, Abbot of Gorze breaks off.

John returned to Gorze and conveyed these carefully reasoned descriptions of the Jewish vizier Hasdai, the Christian vizier Racemundo, and the Muslim caliph Abd al-Rahman to his biographer. John became abbot in 967 and died in 973.

To learn more about medieval al-Andalus, I recommend The Ornament of the World by Maria Menocal. The title of her book comes from Hrosvit of Gandersheim’s poem about Cordoba.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on October 23, 2013 11:10

October 16, 2013

The Ornament of the World

Spain doesn't figure much in tales of the Vikings. In The Viking Age: A Reader, which I wrote about in an earlier post (here), you can see why. As one medieval chronicler explains, the Vikings, whom the Moors called "Madjus," "arrived in about 80 ships. One might say they had, as it were, filled the ocean with dark red birds, in the same way as they had filled the hearts of men with fear and trembling. After landing at Lisbon, they sailed to Cadiz, then to Sidona, then to Seville. They besieged this city, and took it by storm…" But their success didn't last.

Spain doesn't figure much in tales of the Vikings. In The Viking Age: A Reader, which I wrote about in an earlier post (here), you can see why. As one medieval chronicler explains, the Vikings, whom the Moors called "Madjus," "arrived in about 80 ships. One might say they had, as it were, filled the ocean with dark red birds, in the same way as they had filled the hearts of men with fear and trembling. After landing at Lisbon, they sailed to Cadiz, then to Sidona, then to Seville. They besieged this city, and took it by storm…" But their success didn't last."When war engines were used against them, and reinforcements had arrived from Cordoba, Madjus [the Vikings] were put to flight. They [the Moors] killed about 500 of their men, and took four of their ships with all their cargoes. Ibn-Wazim had these burnt, after selling all that was found in them. Then they [Madjus] were defeated at Talyata on the 25 Safar of this year [11 Nov 844]. Many were killed, others hanged at Seville, others hanged in the palm trees of Talyata, and 30 of their ships were burnt. Those who escaped from the bloodshed embarked. … and were no more heard of."

It's not surprising the Moors repulsed the Vikings so efficiently, for the Muslim caliphate of al-Andalus was the most technologically advanced civilization in Europe at the time. Arabic numerals, the efficient 1-2-3 that replaced the clumsy i-ii-iii, came to the West from Baghdad through al-Andalus during the Viking Age, along with many other advances in mathematics, astronomy, agriculture--even paper-making.

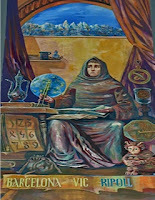

I learned this when writing

The Abacus and the Cross

, my biography of the pope who reigned when Iceland was converted to Christianity in the year 1000. Pope Sylvester II may even have corresponded with King Olaf Tryggvason, who is credited with christianizing Norway; early historians write of a letter (now lost) in which the pope told the king to quit using runes.

I learned this when writing

The Abacus and the Cross

, my biography of the pope who reigned when Iceland was converted to Christianity in the year 1000. Pope Sylvester II may even have corresponded with King Olaf Tryggvason, who is credited with christianizing Norway; early historians write of a letter (now lost) in which the pope told the king to quit using runes.Born Gerbert of Aurillac in about 950, Pope Sylvester II studied mathematics and astronomy near Christian Barcelona from 967-970. (I think of them as his college years.) He learned about Arabic numerals and used them to create a new kind of abacus, or counting board, with which he later taught arithmetic in the cathedral school at Reims, France.

Curious to know more about what Spain was like when young Gerbert arrived, I turned to a book by Maria Menocal of Yale University: The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain (Little, Brown 2002). Inspired by what I read, I contacted Menocal and requested an interview. She was then in Spain—I wish I had joined her! Instead, I waited until she returned to Yale University and met her there in January of 2008. I attended a lecture she presented and accompanied her and her graduate students to dinner; the next morning I interviewed her about her work.

A year ago, Maria Menocal died of melanoma [http://news.yale.edu/2012/10/15/memoriam-mar-rosa-menocal]. Remembering her insight and her generosity, I want to share a bit of what she taught me about al-Andalus.

“Cordoba, by the beginning of the tenth century, was an astonishing place, and descriptions by both contemporaries and later historians suffer from the burden of cataloguing the wonders,” she wrote in The Ornament of the World. It was nearly half as big as Baghdad, the largest city of its day. It held hundreds—maybe thousands—of mosques. Running water from aqueducts supplied nine hundred public baths. The goldfish in the palace ponds ate 12,000 loaves of bread. The paved streets were lit all night. The postal service used carrier pigeons. The munitions factory made 20,000 arrows a month. The market held tens of thousands of shops, including bookshops: Seventy scribes worked exclusively on producing Qurans. The Royal Library in Cordoba, just west of the Great Mosque, was said to contain 400,000 books in 976. (By comparison the greatest Christian library of the time, at Bobbio, Italy, held 690 books.)

Menocal took the title of her book from a poem by the nun Hrosvit of Gandersheim, who met an ambassador from Cordoba in 955 at the German court of Otto the Great. “The brilliant ornament of the world shone in the west,” Hrosvit wrote. “Cordoba was its name and it was wealthy and famous and known for its pleasures and resplendent in all things, and especially for its seven streams of wisdom.”

Significantly, only about 50 percent of Cordoba’s 100,000 residents were Muslim. Among the caliph’s viziers, or advisors, was Hasdai ibn Shaprut, who was Jewish, and Bishop Racemundo (the ambassador Hrosvit met), who was Christian. The Quran teaches that, since Moses and Jesus had both been given books by God, Jews and Christians were fellow “Peoples of the Book,” and thus to be tolerated. In al-Andalus, Menocal explained, they “were dealt with under the special terms of a dhimma, a ‘pact’ or ‘covenant’ between the ruling Muslims and the other book communities living in their territories.” They were not forced to convert, but could practice their religions—as long as they did so quietly and didn’t proselytize. Other than having to pay taxes—which Muslims did not—they were not excluded from the city’s social or economic life. They could, and did, fight in the army. Depending on the ruler’s interpretation of the law, they could advance to the highest political posts, as Hasdai and Racemundo did.

Lecturing on her work in the faux-Gothic humanities center at Yale University, Menocal marveled at the fact that medieval Spain has suddenly become relevant. “We now inhabit a previously inconceivable universe, a universe in which the study of the history of medieval Spain can shed light on modern political problems. What does al-Andalus mean? It’s either about 'conviviencia' or 'reconquista,' either about how the three Abrahamic religions could coexist or how they could not.”

Lecturing on her work in the faux-Gothic humanities center at Yale University, Menocal marveled at the fact that medieval Spain has suddenly become relevant. “We now inhabit a previously inconceivable universe, a universe in which the study of the history of medieval Spain can shed light on modern political problems. What does al-Andalus mean? It’s either about 'conviviencia' or 'reconquista,' either about how the three Abrahamic religions could coexist or how they could not.”“The issue that’s interesting in this period,” Menocal told me the next morning, as she bustled about her office grabbing up papers to take to a departmental meeting, “is how one carves out the wherewithal to have the coexistence of three monotheistic religions that are by definition intolerant.

“Islam arises under conditions where they’re a priori already dealing with these two other monotheistic religions,” she continued. “Medina had a huge population of Jews. For whatever reasons—and they are real political reasons—Islam created the dhimma. I think it does translate into something we could call tolerance. It’s discriminatory, but pretty good, especially in comparison with the other possibilities.

“In Spain it was applied generously, and it provided the basis for much more complex forms of cultural interaction.” Arabic was the lingua franca, not just the language of religion. “To Christians, it was fascinating and very attractive to have this language that was flexible enough to write erotic poetry with and to speak to God with. There’s this whole unimaginable universe that being Arabophone gave you access to: poetry, all the scientific translations coming from Baghdad…”

“In Spain it was applied generously, and it provided the basis for much more complex forms of cultural interaction.” Arabic was the lingua franca, not just the language of religion. “To Christians, it was fascinating and very attractive to have this language that was flexible enough to write erotic poetry with and to speak to God with. There’s this whole unimaginable universe that being Arabophone gave you access to: poetry, all the scientific translations coming from Baghdad…”Or, as she wrote in The Ornament of the World, “This was the chapter of Europe’s culture when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived side by side and, despite their intractable differences and enduring hostilities, nourished a complex culture of tolerance.” In al-Andalus, “men of unshakable faith saw no contradiction in pursuing the truth, whether philosophical or scientific or religious, across confessional lines.”

It was a powerful combination and produced a civilization to whom an attack of the Vikings was like the descent of a flock of red birds--a flock easily chased away.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on October 16, 2013 07:09

October 9, 2013

Leif Eiriksson Day

Today, October 9, is officially Leif Eiriksson Day, named for the Viking explorer who discovered North America 500 years before Columbus (whose day we celebrate a symbolic three days later).

Today, October 9, is officially Leif Eiriksson Day, named for the Viking explorer who discovered North America 500 years before Columbus (whose day we celebrate a symbolic three days later). Last year, I suggested that today should better be named "Gudrid the Far-Traveler Day." Leif happened upon the land he named Vinland by chance in about 999, when he was blown off course traveling between Norway and Greenland. He never went back.

Gudrid, Leif's sister-in-law, packed up and set sail for Vinland twice--with two different husbands. Though the Vinland Sagas, the two medieval Icelandic sagas that tell her story, disagree on the particulars, Gudrid's hand in the preparations each time is clear. As is the fact that she stayed longer than Leif. With her husband Thorfinn Karlsefni, Gudrid explored the New World for three winters, giving birth there to her son Snorri.

But where in North America did Leif--or Gudrid--go?

Georgia. Or between Pennsylvania and the Carolinas. Or New York harbor. Boston, on the Charles River near Harvard University. Rhode Island or Martha’s Vineyard. Cape Cod or the coast of Maine. New Hampshire, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Labrador, the St. Lawrence Valley, or back in Greenland.

All of these places have been suggested in a serious manner between 1757 and today. As the irrepressible BBC television host Magnus Magnusson said at a conference in Newfoundland in 2000, “Enthusiasts have twiddled the texts, selected from the texts, conflated the texts, and compromised the texts in endless attempts to create a coherent story that will ‘prove’ their particular hypothesis. But frankly, the sailing directions which dozens of eager researchers have tried to follow are not much more explicit than the old Icelandic adage for getting to North America: Sail south until the butter melts, and then turn right.”

Though folklorist Gisli Sigurdsson believes the Vinland sagas hold a coherent “mental map” of Viking explorations along the coast of North America, he concedes that “perhaps the most striking feature of the attempts to locate Vinland is that each and every person to have made one has disagreed with everyone else.”

The sagas say that Vinland is southwest of Greenland. There's a prominent island thick with birds’ nests, a wide shallow bay, a sandy cape, an amazingly long beach somewhere to the north, a river with tidal flats, and a couple of lakes.

The sagas sometimes tell how long it took to sail from one spot to another, but scholars argue viciously over how to translate “a day’s sail” into a distance. Is a “day” 24 hours? Twelve hours? The time when the sun is up? The Icelandic word (like the English one) is inexact.

A Viking ship can sail as fast as 11 to 13 knots per hour, we know from the voyages of replica ships. It can also lie becalmed and be storm-driven backward. Some scholars take the wind into account. Others note that a cautious captain in an unknown sea with no hope of rescue might care to take his time, while an explorer, by definition, should poke into every interesting cove and bay.

A Viking ship can sail as fast as 11 to 13 knots per hour, we know from the voyages of replica ships. It can also lie becalmed and be storm-driven backward. Some scholars take the wind into account. Others note that a cautious captain in an unknown sea with no hope of rescue might care to take his time, while an explorer, by definition, should poke into every interesting cove and bay.A note on the length of a winter day in The Saga of the Greenlanders has been similarly dissected. It has “proved” that Vinland lay at a latitude of 31 degrees North (as does Jekyll Island, Georgia)—and at 50 degrees North (nearer to L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, where Viking artifacts have been found). The saga says simply: “The length of day and night was more equal than in Greenland or Iceland,” adding that the sun could be seen “during the short days” at eyktarstaður and at dagmalastaður. No one knows if those two terms apply to the places on the horizon where the sun rises and sets, or to times of day.

With the sailing directions and the day length both inscrutable, we are left with the Vikings’ list of Vinland’s riches. The land is called “Wine Land” so often, not only in the sagas but in other sources, that there must have been some berry from which wine could be made; the question of whether wine requires grapes has bedeviled generations of scholars. Although the words usually translated as “wine wood” and “wine berries” refer to grapevines and grapes in modern Icelandic, we can’t be sure they did so in Gudrid’s day.

A related question is whether the Vin of Vinland has a long or short “i”: vín (long “i”) means wine; vin (short “i”) means meadow. Although most scholars are convinced by linguistic arguments that Vinland is Wine Land not Meadow Land, and that the “Meadow” in the name L’Anse aux Meadows is a corruption of a French word for jellyfish, the other side of the debate still arises.

The sagas do mention pastures “so rich that it seemed to them the sheep would need no hay all winter. There was no frost in the winter, and the grass hardly withered.” There was also some kind of wild grain that resembled wheat. Eider ducks nested on the offshore islands, whales washed up on the beaches, and fish, including large salmon, could be easily caught. There were bears and foxes and plentiful game. Finally there were mosurr trees “big enough for house timbers.” (Twenty feet would have been tall enough).

The Viking ruins at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the northwestern tip of Newfoundland, were discovered in the 1960s. Now, after 40 years of argument and analysis, the experts agree it was a base camp where the Vikings spent the winter after exploring further south. [I wrote about visiting L'Anse aux Meadows on this blog on July 25, 2012.]

Research published in 2013 by archaeologist Kevin Smith proves that the Vikings went from there at least as far as Notre Dame Bay, 143 miles south, where they picked up a piece of jaspar--and may have encountered the Beothuck Indians. As archaeological research has shown, Newfoundland's Notre Dame Bay was home to a dense settlement of Beothuck Indians a thousand years ago. [See my blog post of July 24, 2013.]

In my book The Far Traveler [and on this blog on May 23, 2012], I presented archaeologist Birgitta Wallace's theory--based on her discovery of butternuts in the Viking Age layers of the L'Anse aux Meadows did--that one of the places described in the Vinland Sagas was the mouth of the Miramichi River in New Brunswick.

Recently I've heard from two new explorers trying to trace the Vikings' route through North America.

First is the Fara Heim expedition [http://faraheim.com] organized by Icelandic-Canadians Johann Straumfjord Sigurdson and David Collette; their expedition's name comes from the Icelandic að fara heim, meaning "to go home." According to their website, Fara Heim will sail from Manitoba, Canada, across Hudson Bay, and through Arctic waters to Greenland and Iceland. Drawing from "historical data, verbal history, community knowledge, and analysis of modern data," they will visit "likely sites" and look for "signs of Norse presence." It's a bit like Helge Ingstad's protocol when he searched for--and found--the Viking ruins at L'Anse aux Meadows. I wish them well.

I've also heard from Donald Wiedman, who blogs at http://lavalhallalujah.wordpress.com. As he writes, "Though interested and intrigued by Denmark and Scandinavia, Donald was/is not on any particular mission to locate the lost Viking settlements in North America--but he’s positive he’s found them." Using Google Satellite and various old maps, he places Vinland in Laval, Quebec, which is in line with the speculations of many Old Norse scholars that any Vikings cruising the Gulf of St Lawrence would have sailed up the St Lawrence River toward what's now Quebec City.

I've also heard from Donald Wiedman, who blogs at http://lavalhallalujah.wordpress.com. As he writes, "Though interested and intrigued by Denmark and Scandinavia, Donald was/is not on any particular mission to locate the lost Viking settlements in North America--but he’s positive he’s found them." Using Google Satellite and various old maps, he places Vinland in Laval, Quebec, which is in line with the speculations of many Old Norse scholars that any Vikings cruising the Gulf of St Lawrence would have sailed up the St Lawrence River toward what's now Quebec City. But, like the Fara Heim sailors, unless Wiedman finds an archeological site with demonstrably Viking artifacts (as at L'Anse aux Meadows), the debate about where the Vikings sailed will go on and on.

Which is why it excites me. Icelandic storytellers kept the knowledge of Vinland alive for 200 years before it was written down in the two Vinland Sagas, The Saga of the Greenlanders and The Saga of Eirik the Red. These sagas were copied and recopied and come down to us in three manuscripts. The Saga of the Greenlanders takes up two pages in Flateyjarbók, the Book of Flatey, a beautiful manuscript written between 1387 and 1394. The Saga of Eirik the Red appears in two very different versions in Hauksbók, the Book of Haukur (1299-1334), and Skálholtsbók, the Book of Skalholt (written around 1420).

Six hundred years later, these Icelandic stories are still inspiring explorers and archaeologists. Their authors and editors and copyists should be proud. Today is their day too.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on October 09, 2013 07:28