Nancy Marie Brown's Blog, page 11

February 19, 2014

The History Channel's Viking Earl

To get ready for Season Two of the History Channel's TV series, "The Vikings" (premiering February 27), I've been watching Season One on DVD, as I mentioned in last week's post [here]. And I've been reminded of some of the things that bothered me.

To get ready for Season Two of the History Channel's TV series, "The Vikings" (premiering February 27), I've been watching Season One on DVD, as I mentioned in last week's post [here]. And I've been reminded of some of the things that bothered me.I'm glad that Earl Haraldsson died--much as I like the actor Gabriel Byrne--because that name drove me nuts. Haraldsson? If you know anything about Old Norse, the Viking language, you know that "Haraldsson" literally means "Harald's son," and no self-respecting Viking chieftain is going to live his life in his father's shadow. For a while, I thought his first name was "Earl." Odd, but not impossible. (I know a horse named "Earl.") But no, "Earl" is a title, as we learned when Ragnar Lothbrok became earl.

Some people in the Icelandic sagas are referred to by their patronymics (or matronymics). There are the Hildaridarsons, for example, in Egil's Saga, named for their mother Hildirid.

In the far north of Norway, we read in Chapter 7 of the Herman Pálsson and Paul Edwards translation, "there was a man called Bjorgolf, farming on Torg Island. He was a land-holder, rich and powerful, though he was a hill-giant on one side of his family, as you could tell from his size and strength. He had a son called Brynjolf, very much like his father."

One autumn, when Bjorgolf was getting on in years, he was invited to a feast. "As was the custom, lots were cast every evening to decide which pairs were to sit at the same drinking horn." A beautiful young girl named Hildirid was paired with the old half-troll. "They had plenty to talk about all evening and he thought her a fine-looking girl."

One autumn, when Bjorgolf was getting on in years, he was invited to a feast. "As was the custom, lots were cast every evening to decide which pairs were to sit at the same drinking horn." A beautiful young girl named Hildirid was paired with the old half-troll. "They had plenty to talk about all evening and he thought her a fine-looking girl."A few weeks later, Bjorgolf sets off in his Viking ship with a crew of 30. He walks up to Hildirid's house and announces to her father that "I'm taking your daughter back home with me and mean to tie a loose marriage-knot here and now." He pays the father an ounce of gold (a good bride-price: an ounce of gold is worth eight ounces of silver, and you could buy a slave girl for one ounce of silver) "and off they went to bed."

Hildirid soon has two sons--and then old Bjorgolf dies. "No sooner had he been carried to the grave, than Brynjolf"--Bjorgolf's older son--"told Hildirid to take her sons and clear out, so she wet back to her father on Leka Island, where her sons grew up." The boys got none of their father's inheritance (though their mother's father left them pretty well-off), and turned into spiteful, sly, manipulative sneakers generally referred to as that "pair of bastards" or "the Hildaridarsons." They didn't deserve names.

Soon the Hildaridarsons had wheedled their way into King Harald's confidence. They began slandering the great warrior Thorolf, son of Kveld-Ulf ("Evening-Wolf"--not only do we have hill-trolls in this saga, we have werewolves). The king had asked Thorolf to collect the tribute of furs that the Finns owed each year. It was a lucrative position, even if the tax-collector didn't skim off the best for himself, as the Hildaridarsons claimed Thorolf did.

"The King would never believe such a pack of lies," said Thorolf, when his friends told him of the slander. "There's not a scrap of evidence here that I'd betray him."

Yet King Harald did believe it. In Chapter 22, he sails north with 300 men in six ships. They catch Thorolf unaware in the middle of a feast, surround his great hall and set fire to it. The women and children, old people, slaves, and servants are allowed out. Thorolf and his warriors break down a wall and burst from the burning hall.

"Fighting broke out at once and for a time Thorolf and his men used the house to shield their backs, but as it blazed up the fire started threatening them and soon many had been killed. Thorolf ran forward towards the King's banner striking out to left and right.… Thorolf came right up to the thick wall of shields and ran the standard-bearer through with his sword.

"'I'm just three paces short,' Thorolf said.

"He had been pierced with spears and swords, but it was the King who gave him his death-wound and Thorolf dropped down at his feet."

When Kveld-Ulf heard the news he had only one question: Did his son die on his face or on his back? "Old men used to say that anyone who fell face down would be avenged, and that the retribution would come as close to the killer as the victim's fall was close to him."

And so the saga begins.

Back to the History Channel's TV series, "The Vikings." Are we, as viewers, supposed to know all this? Are we supposed to know that someone referred to only by his mother's or father's name is a coward and a conniver? Does Earl Haraldsson--or his wife--ever refer to him by his real name? Or are we supposed to accept the idea that he thinks of himself as too poor an example of manhood to deserve a name? What were the writers thinking?

The Icelandic poem called Hávamál, or "Words of the High One," presents the closest thing we have to a Viking code. The most famous verse runs like this:

Cattle die, kinsmen die,

Every man must die.

But one thing only never dies:

A name with honor earned.

From what I saw of Gabriel Byrne's Earl Haraldsson, in Season One of the History Channel's TV series, "The Vikings," I think he earned a name. Shall we give him one?

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And if you want to learn what happened next in Egil's Saga, join me on the Song of the Vikings tour from America2Iceland.com, where we'll ride through the landscape of Part Two of the saga.

Published on February 19, 2014 05:30

February 12, 2014

The History Channel's Viking Funeral

Looking forward to Season Two of the History Channel's series, "Vikings" (premiering February 27), I've been watching Season One on DVD. One of the things I've enjoyed about this series is seeing how they've brought to life some of the most famous historical documents about the Vikings.

Looking forward to Season Two of the History Channel's series, "Vikings" (premiering February 27), I've been watching Season One on DVD. One of the things I've enjoyed about this series is seeing how they've brought to life some of the most famous historical documents about the Vikings.The funeral of Earl Haraldsson in Episode 6, "Burial of the Dead," with the Angel of Death strangling a slave girl to accompany her master on the burning ship to Valhalla, is a good example. It is closely based on the report of a 10th-century Arab traveler, Ahmad Ibn Fadlan.

On June 21, 921, Ibn Fadlan left Baghdad with a large caravan of camels. He was part of a delegation from the Caliph Al-Muqtadir to the Volga Bulghars, who lived thousands of miles north at the meeting of the Volga and Kama rivers in what is now Russia. The Bulghar king had asked the caliph to send him people to "acquaint him with the religious codes of Islam" and to construct a mosque. Ibn Fadlan went along in some official role--exactly what, we don't know.

The embassy was a failure--"the 'correction' of the Bulghar practice of Islam did not go over smoothly," writes Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, who wrote his 2013 Ph.D dissertation for the University of Bergen on "The Rus in Arabic Sources." (You can find it online here: https://hi.academia.edu/ThorirJonssonHraundal)

But that didn't stop Ibn Fadlan from writing wonderful traveler's tales, which you can read in the book Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness in translations by Paul Lund and Caroline Stone: "We saw a land which made us think a gate to the cold of hell had opened before us," Ibn Fadlan writes. His beard, after a bath, became a block of ice. His cheek at night froze to his pillow. "In this country, when a man wishes to make a nice gesture to a friend and show his generosity, he says: 'Come to my house where we can talk, for there is a good fire there.'"

For the history of the Vikings, the most important of Ibn Fadlan's tales are the ones about the "Rus," a people scholars have connected with Vikings from Scandinavia who traded and raided from what is now Russia (named for the "Rus") south to Baghdad.

For the history of the Vikings, the most important of Ibn Fadlan's tales are the ones about the "Rus," a people scholars have connected with Vikings from Scandinavia who traded and raided from what is now Russia (named for the "Rus") south to Baghdad.In the 10th century, the Volga Bulghars, whom Ibn Fadlan visited, were one of four powers that controlled the area between the Black Sea and the Caspian. South of the Caucasus Mountains was the Islamic Empire. To the west was the Christian Byzantine Empire, based in Constantinople. North of the mountains were the Khazars, whose king was Jewish, but whose people were of all faiths: Jews, Christians, Muslims, and pagans of several varieties lived side-by-side, though some had to pay higher taxes than others. The Volga Bulghars were farther north--technically Muslim, but apparently not firm in the faith--and again, their culture accommodated many religions.

Ibn Fadlan's tale is the longest of 30 Arabic sources that mention the Rus--some just a sentence, others several pages long. The other main source on the Rus is the Russian Primary Chronicle, which describes the trade route from Russia to Constantinople and the founding of the Russian state and the Russian Orthodox Church. The Arab writers, says Hraundal, "provide us with a significantly different version of Rus, reporting them not only in a different geography to that of the Primary Chronicle, but also as having different social structures and roles in relationship with their neighbors. Importantly, too, these Rus seem to have no ambition either to found a state or to become Christian, two subjects that have especially occupied scholars of early Rus history."

The Rus the Arabs met were traders and raiders and mercenaries--and by the 10th century, they were well on their way to being integrated into the local cultures, which were Turkish and Altaic. Analyzing Ibn Fadlan's funeral scene, for example, Hraundal finds several similarities to the pagan rituals of the western Eurasian steppes, including the strangling of the slave girl. He concludes, "At the very least it seems that comparing various Turkic or Altaic elements cannot reasonably be deemed more implausible than doing so with the Scandinavian elements. On the whole, it is perhaps more prudent to assume that the ritual is attributable to the traditions and customs of not one culture, but two or several."

Judith Jesch in her classic book, Women in the Viking Age, Hraundal notes, "warns of generalising from Ibn Fadlan's account about practices elsewhere in the Viking world. Everywhere the Scandinavians went, she maintains, 'they developed new ways of living which owed something both to the culture of the immigrant Vikings and to that of the country in which they found themselves, so that no two areas colonised by Scandinavians were alike.'" The people Ibn Fadlan meant "are likely to have been a select band of merchant-warriors," Jesch adds, "who, like other touring professionals, may not have behaved the same way when abroad as they did at home."

Which brings us back to the History Channel's "Vikings." The funeral in "The Burial of the Dead" is closely based on a historical document, but it's not exactly a "Viking" funeral from around 800, the era in which the TV series is set. It's a "Rus" funeral from 921--and no one knows how a chieftain's funeral in Scandinavia a hundred and some years earlier might have been different.

Snorri Sturluson, writing in about 1220, does say that the god Baldur was burned in his ship. Snorri also tells us that Baldur's wife, Nanna, was burned along with her husband--though she wasn't strangled. Instead, her death was an accident: She died of grief when she saw his dead body. What does this tell us about Viking funerals? Alas, nothing. Snorri was writing 400 years later than the era in which the History Channel series is set, and his Edda cannot in any way be considered "history." (I discuss Snorri's myth of Baldur's Death in my book, Song of the Vikings, as well as on this blog, in the series "Seven Myths We Wouldn't Have Without Snorri.")

Snorri Sturluson, writing in about 1220, does say that the god Baldur was burned in his ship. Snorri also tells us that Baldur's wife, Nanna, was burned along with her husband--though she wasn't strangled. Instead, her death was an accident: She died of grief when she saw his dead body. What does this tell us about Viking funerals? Alas, nothing. Snorri was writing 400 years later than the era in which the History Channel series is set, and his Edda cannot in any way be considered "history." (I discuss Snorri's myth of Baldur's Death in my book, Song of the Vikings, as well as on this blog, in the series "Seven Myths We Wouldn't Have Without Snorri.")Archaeological research tells us a little more. We've found Viking graves with the remains of burned ships--a famous one is at Île de Groix in France. But we've also found Viking graves from around 800 in which chieftains were buried inside their ships, not burned with them--most famously, the Gokstad burial.

Recent studies of rich Viking graves containing two bodies have confirmed that one of the dead ate less well than the other, meaning that one body could have been a chieftain and the other a slave. But these slaves who accompanied their masters in death were not strangled: They were beheaded. [For more on this research, see http://www.medievalists.net/2013/12/15/viking-slaves-were-beheaded-and-buried-as-grave-gifts-archaeological-find-suggests/]

To create a dramatic TV series about the Vikings, the writers for the History Channel have to walk a fine line between making use of the historical sources we have and filling in the gaps with their own imaginations. In this case, I think they've done an excellent job bringing Ibn Fadlan's account to life. But viewers need to keep in mind that Ibn Fadlan's account was just one report from one place (Russia) in one time (921) and not really applicable to the lives of people a hundred years earlier and many thousands of miles away. Not to mention that Ibn Fadlan, like all travelers, was prone to exaggerating. Did his cheek really freeze to the pillow?

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And if you would like to go to Iceland with me next summer (and acquire a few travelers' tales of your own), check out the tours at America2Iceland.com.

Published on February 12, 2014 04:53

February 5, 2014

Still Carried Away

Today marks two years of weekly "God of Wednesday" posts, and to celebrate I'm going to revisit my very first entry--not coincidentally the beginning of my very first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse:

Today marks two years of weekly "God of Wednesday" posts, and to celebrate I'm going to revisit my very first entry--not coincidentally the beginning of my very first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse:CARRIED AWAY

I could hear the horses before I saw them, their hoofbeats the high slap of cupped hands clapping, beating the punctuated four-beat rhythm of the tolt, the breed's distinctive running-walk gait. From our summerhouse, I watched them through binoculars. Pinpricks on the silvery wet sand, they shimmered like a vision out of the Icelandic Sagas, the medieval literature that had brought me to Iceland in the first place. Briefly the horses took shape as they cut across the tide flats: necks arced high, manes rippling, long tails floating behind. Their short legs curved and struck, curved and struck. I would watch them until they disappeared beyond the black headland and wonder who their riders were, where they went on their rapid journey. I wanted to go with them.

Icelandic folktales warn of the gray horse that comes out of the water, submits briefly to bridle and saddle, and at dusk carries its rider into the sea. For me, it was the watcher who was carried away.

I'm happy to say I'm still carried away: by Iceland, its folklore, its sagas, its people, its language, and its horses. A Good Horse Has No Color is back in print, in paperback, and has been joined on my shelf by two more books about Iceland, The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman and Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths. A young adult novel based on The Far Traveler will be coming out this year, and my new nonfiction book, The Ivory Vikings, scheduled for spring of 2015, has a strong Icelandic focus.

Birkir and Gaeska, the two Icelandic horses at the center of A Good Horse Has No Color are still frolicking in my pastures, now ages 23 and 24, and have two younger stablemates, Mukka and Naskur, both from the American farm Alfasaga. In addition to riding them most days (when there's no snow on the ground), I'm now collaborating with the horse-trekking firm America2Iceland to organize historical riding tours to Iceland. There's still room on our Song of the Vikings tour this June 5-11: See America2Iceland.com if you're interested. I'd love to show you the Iceland that inspires me. One of their trips even takes you along that same silvery wet sand, across the tide flats, past the black headland into … another world.

For me, being carried away by Iceland has been a wild and wonderful trip. I hope you'll continue to come along for the ride.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on February 05, 2014 10:35

January 29, 2014

Charlemagne's Elephant

Twelve hundred years ago yesterday--January 28, 814--to quote my friend Jeff Sypeck, "the Franks lamented the death of a tall, paunchy, mustachioed king whom they already knew was one of the most important people in European history: Karl or Charles the Great, Karolus Magnus, Charlemagne."

Twelve hundred years ago yesterday--January 28, 814--to quote my friend Jeff Sypeck, "the Franks lamented the death of a tall, paunchy, mustachioed king whom they already knew was one of the most important people in European history: Karl or Charles the Great, Karolus Magnus, Charlemagne."Europe will be celebrating this anniversary all year, Jeff points out on his blog, Quid Plura, with scholarly symposia, pilgrimages to Charlemagne's cathedral at Aachen, an art installation of 500 Charlemagne statues in a public square, a new Aachen Bank card, an opera, and a comedy performance, "Karl and the White Elephant," among many other events.

I celebrated in a quieter way--by rereading some chapters from Sypeck's own fabulous biography, Becoming Charlemagne: Europe, Baghdad, and the Empires of A.D. 800, published by HarperCollins in 2006. This was one of the books that made me think I might want to write popular history myself.

If you read only one book about Charlemagne this year, read Becoming Charlemagne by Jeff Sypeck.

Charlemagne's reign (768-814) overlaps with the beginning of the Viking Age (793), which is the reason I'm especially interested. Some scholars say his wars with the Saxons provoked the first Viking raids on the Continent; others that the power vacuum after his death gave the Vikings their opportunity.

Charlemagne's reign (768-814) overlaps with the beginning of the Viking Age (793), which is the reason I'm especially interested. Some scholars say his wars with the Saxons provoked the first Viking raids on the Continent; others that the power vacuum after his death gave the Vikings their opportunity.Sypeck doesn't look north in Becoming Charlemagne, his interests are east and south, in Byzantium and Baghdad. Here you will learn, for example, about the great Islamic empire that stretched from Baghdad to Cordoba. You'll visit the City of Peace at daybreak, in one beautiful chapter: the monasteries where secret wine parties were held, the markets which sold every luxury, the circular walls and four grand gates, the green-domed mosque in the center.

You'll learn how the Franks looked to their neighbors. In 10th-century Baghdad al-Masudi wrote:

"The warm humor is lacking among them; their bodies are large, their natures gross, their manners harsh, their understanding dull, and their tongues heavy. Their color is so excessively white that it passes from white to blue… Those of them who are furthest to the north are the most subject to stupidity, grossness, and brutishness."

And you'll read about Charlemagne's elephant, Abul Abaz, a gift from the caliph Harun al-Rashid (the caliph of The Arabian Nights).

"The first thousand miles were probably the worst," Sypeck writes. "Coming from Baghdad, the man known to Frankish annalists as Isaac the Jew passed through Jerusalem, crossed the Sinai, and journeyed along the Egyptian coast. …

"All caravans moved slowly, of course, but in this case the pace was even slower, because of one of Isaac's traveling companions, a lumbering ambassador from Baghdad who was vast in size, ravenous, and prone to wander… He needed around twenty gallons of water each day. He needed shade, and he rarely slept. Keeping Abul Abaz happy, and keeping him moving, was a job without end.

"The sun was harsh, the earth was cracked, and Isaac was in a dead zone between the culture of Baghdad and the comforts of home. Whatever reward awaited him for leading an elephant across 3,500 miles, it could not have been enough."

Sypeck laments, as do I, that everyone remembers Charlemagne's elephant--but no one thinks about poor Isaac, Charlemagne's ambassador. Is this what he'd agreed to when he signed on? Should he not, at least, have won undying fame for bringing Europe the first elephant it had seen since Hannibal's in 218 B.C.?

Sypeck laments, as do I, that everyone remembers Charlemagne's elephant--but no one thinks about poor Isaac, Charlemagne's ambassador. Is this what he'd agreed to when he signed on? Should he not, at least, have won undying fame for bringing Europe the first elephant it had seen since Hannibal's in 218 B.C.?Modern writers have even replaced him with a hero more like themselves: A 19th-century Egyptian novel describes "the adventures of a Persian noble, not a Frankish Jew, who delivered a white elephant to Karl on behalf of Harun. Two modern children's books about Abul Abaz also eliminate Isaac"--these are C. Walter Hodges's The Emperor's Elephant (1975) and Judith Tarr's His Majesty's Elephant (1993). One makes the elephant's keeper a boy named Selim.

"Perhaps," Sypeck says, charitably, "modern storytellers have too little to work with, but it is sad that the world has no memory of Isaac and the details of his amazing five-year journey."

At a time when Viking ships were bearing down on British monasteries, when Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor, when Baghdad was at its peak and Byzantium was teetering, a Frankish ambassador named Isaac the Jew was struggling to bring a white elephant from Baghdad to Aachen. He arrived in 802.

In 810, when Charlemagne marched north to face a fleet of 200 Viking ships then ravaging the coast of Frisia, he took his white elephant with him to terrify the enemy. Unfortunately, Abul Abaz died on the way.

Read more about Charlemagne--and order Jeff Sypeck's book--at http://www.quidplura.com. The carving of the elephant is from the "Charlemagne chess set," once thought to have been another gift of Harun al-Rashid, but now dated to the 11th century.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on January 29, 2014 08:00

January 22, 2014

Poet-Maidens and Shield-Maidens

Songs of the Vikings--Viking poetry--has been the topic of this blog a number of times. Poetry was the gift of Odin, according to the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson (you can read that story from an earlier blog post here), and Vikings loved their poems as much as they loved drinking mead.

Songs of the Vikings--Viking poetry--has been the topic of this blog a number of times. Poetry was the gift of Odin, according to the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain Snorri Sturluson (you can read that story from an earlier blog post here), and Vikings loved their poems as much as they loved drinking mead.Poets, or skalds, as I've written in my book Song of the Vikings (just out in paperback!), were a fixture at the Norwegian court for over 400 years. They were swordsmen, occasionally. But more often they were a king’s ambassadors, counselors, and keepers of history. They were time-binders, weaving the past into the present.

In a world without written record—as the Viking world was—memorable verse made a man immortal. Or a woman.

I recently discovered a book by Sandra Ballif Straubhaar called Old Norse Women's Poetry: The Voices of Female Skalds, published by D.S. Brewer in 2011. It contains nearly 50 poems, some long, some short, by women, real or imagined, from Viking Age Norway through the time of Snorri Sturluson's Iceland (and a little beyond). In Straubhaar's translations, these medieval women are valkyries of verse, with tongues as sharp as swords.

I recently discovered a book by Sandra Ballif Straubhaar called Old Norse Women's Poetry: The Voices of Female Skalds, published by D.S. Brewer in 2011. It contains nearly 50 poems, some long, some short, by women, real or imagined, from Viking Age Norway through the time of Snorri Sturluson's Iceland (and a little beyond). In Straubhaar's translations, these medieval women are valkyries of verse, with tongues as sharp as swords.One of them was a king's skald--and possibly a shield-maiden. Jorunn skáldmær ("Poet-maiden") composed a poem congratulating her fellow king's skald for negotiating peace between two princes, both sons of Harald Fairhair, the ninth-century king who unified Norway. Snorri quotes her poem in his Saga of King Olaf the Saint. Notes Straubhaar: "The Flateyjarbok manuscript of Olafs saga helga uniquely calls Jorunn not skáldmær ('poet-maiden') but skjáldmær (‘shield-maiden’). Given that Olafr … was known to station his male warrior-poets around him in the shield-wall for the better subsequent recording of great battle-deeds, it is tempting to think of Jorunn playing such a role for Haraldr."

Another women poet Straubhaar introduces us to was well able to handle a sword. When the 10th-century Icelander Breeches-Aud is divorced by her husband--ostensibly because she dresses like a man, in breeches--she not only spits out a poem, she gets on her horse (yes, wearing breeches) and rides off to avenge herself. Finding her husband asleep, Straubhaar writes, Aud "draws her sword on him, striking not to kill, but only to cripple. She gashes him across the nipples, successfully puts his sword-arm out of commission, and leaves him pinned in the bed with the blade. Then she rides away, presumably feeling the score to be now even."

In two of my favorite poems in Straubhaar's collection, the woman poet has a tongue every bit as sharp and precise as Aud's sword.

In Iceland in 999 a woman named Steinunn makes fun of a Christian missionary in a poem that is "metrically near-flawless," Straubhaar says. "It has a fine, aggressive rhythm, echoing its sea-going topic, and lively kennings."

I explained the complexity of skaldic verse in an earlier post on the mechanics of Viking poetry (read it here). Straubhaar handles that complexity by translating each poem twice: once in verse (to capture the form) and once in prose (to give the literal meaning). "In the poetry translations," she explains, "I have tried to maintain at least some of the following features of the originals, in this order of precedence:

--Meaning

--Tone (e.g., heroic, comic, serious, frightening)

--Alliteration (at least sets of two, ideally sets of three…)

--Syllable count (six per line, in dróttkvætt) and/or stress count

--Internal rhyme (perfect and slant); also occasional end-rhyme

--Circumlocutions for nouns, both complex and simple: kenningar (e.g., ‘goddess of gold’ for ‘woman’) and heiti (e.g., ‘ski’ for ‘ship’).

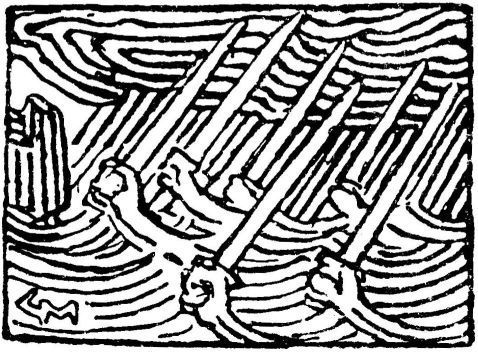

The mocking tone, especially, of Steinunn's poem comes through brilliantly: Thorr snatched Thangbrandr’s longboat,

The mocking tone, especially, of Steinunn's poem comes through brilliantly: Thorr snatched Thangbrandr’s longboat,thwacked it, smashed it, wrecked it,

shook the prow-steed, plowed it

precisely, nicely under.

So sad! No more sliding

of ski upon the sea-foam:

god-gales grabbed the sail-horse,

god-winds chewed its splinters.

The tone, again, is perfect in Straubhaar's translation of another mocking poem. Here, the daughter of Earl Arnfinn, somewhere in 10th-century Denmark, rebuffs the advances of an untried warrior:

Who said this seat was yours, boy?

Seldom have you drawn sword.

From you the wolf gets no flesh.

My flesh likes sitting solo.

You’ve never seen the crow caw

on corpses slain at harvest;

when shell-sharp swords came slashing

you shied away, and stayed home.

Many of the verses Straubhaar translates are said, in the sagas that contain them, to be spoken by witches, trolls, wise-women, and valkyries. Who would not shiver at this witch's curse?

May wights wander free,

and wonders be seen;

may cliffs crash,

and plains quake;

may the weather worsen…

I curse your ears

so they cannot hear.

I curse your eyes

to turn inside out…

When you set sail,

the riggings will slit,

the rudder will rip

free from its frame,

the sails will rot

and fall free from the mast,

the sheets will split

and fly free in the wind…

In your bed,

burning straw;

in your privy

queasy unease;

and after that

worse things…

And then there is the poignant set of verses by a 16-year-old in the south of Iceland in 1255, eight stanzas that constitute "the largest body of poetry by a single historically attestable woman that survives in Old Norse literature," Straubhaar says. Knowing her kinsmen are caught up in a great battle in the north, Jorunn speaks a poem she heard in a dream:

And then there is the poignant set of verses by a 16-year-old in the south of Iceland in 1255, eight stanzas that constitute "the largest body of poetry by a single historically attestable woman that survives in Old Norse literature," Straubhaar says. Knowing her kinsmen are caught up in a great battle in the north, Jorunn speaks a poem she heard in a dream:By his house-door he bides,

byrnied for battle.

Fiends wait with fire,

false dogs that they are.

False dogs that they are!

...

The snare is snapped;

fate has them trapped.

These men I would tell

to go straight to Hel,

to go straight to Hel.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And if you would like to go to Iceland with me next summer, check out the tours at America2Iceland.com.

Published on January 22, 2014 08:26

January 15, 2014

Burial Rites

A friend who is going to Iceland with me next summer, on her first trip there, gave me Hannah Kent's novel, Burial Rites, last October. We had both been thrilled with the early reviews, thrilled to see a book set in Iceland in 1828 getting so much attention.

A friend who is going to Iceland with me next summer, on her first trip there, gave me Hannah Kent's novel, Burial Rites, last October. We had both been thrilled with the early reviews, thrilled to see a book set in Iceland in 1828 getting so much attention.But my friend had read Burial Rites before she gave it to me and, though she tried to hide it, I could tell she didn't like it. I had a lot to read already. I put it on my shelf and didn't open it until right before Christmas.

Once I started, I read it in a rush. It's a beautiful book, though a very sad one, about a young woman condemned to be beheaded for murders she may or may not have committed. Kent's lyrical writing drew me in and, though I intended to be critical and frowned at her mention of thorn bushes and brambles plucking at a woman's skirts (I've never seen thorn bushes and brambles in Iceland), there were very few mistakes of this kind. Kent had, indeed, visited the Iceland I knew, had read the same 18th- and 19th-century travelers' tales as I had, had read the Icelandic sagas.

I asked my friend why she didn't like the book. It was "claustrophobic," she said.

True. But to me that's proof of Kent's skill as a writer: She was able to make the reader feel the claustrophobic atmosphere of life inside a turf house on a farm a bare step above abject poverty in a country that has, in addition to its gloriously long summer days (when I visit), an equally long, dark winter.

In Iceland in 1828 there were no jails. So until her execution the convicted murderess, Agnes, is kept on a farm where the housewife, Margrét, chooses to treat her as a servant (she's sane and a good worker) instead of locking her up. But there's no real difference, when winter comes, between being a servant and being a prisoner on a poor Icelandic farm.

Here's a passage from Burial Rites:

Here's a passage from Burial Rites:Autumn fell upon the valley like a gasp. Margrét, lying awake in the extended gloom of the October morning, her lungs mossy with mucus, wondered at how the light had grown slow in coming; how it seemed to stagger through the window, as though weary from traveling such a long way. Already it seemed a struggle to rise. She'd wake in the chill night with Jón pressing his toes against her legs to warm them, and the farmhands were coming in from feeding the cow and horses with their noses and cheeks pink with the ice in the air. Her daughters had said that there was a frost every morning of their berrying trip, and snow had fallen during the round-up. Margrét had not gone, not trusting her lungs to last the long walk up over the mountain to find and herd the sheep from their summer pasture, but she'd sent everyone else. Except Agnes. She could not let her walk over the mountain. Not that she would flee. Agnes wasn't stupid. She knew this valley, and she knew what little escape it offered. She'd be seen. Everyone knew who she was.

As the story progresses, it's clear that Agnes is not the only person under a sentence of death. Everyone Agnes has ever cared about in the past has died--in childbirth, through illness or accident--and those the reader comes to care about, like Margrét with her bad lungs, are equally fragile.

I do have one complaint with Kent's approach. There's a bit of the medieval Laxdaela Saga plunked into the last quarter of Burial Rites. A line of the saga--"I was worst to the one I loved best"--is used as the epigraph. To someone, like me, who has studied Laxdaela Saga it's a puzzling inclusion. I can't imagine what someone who's never read Laxdaela Saga would make of it, but to me the comparison between Gudrún of Laxdaela Saga and Agnes is belittling to both stories. The motives of both women are reduced to mere jealousy, whereas there's no comparison between Kjartan (whose death Gudrún masterminded) and Natan (whom Agnes is convicted of killing). The Kjartan-Gudrún love story is tragically complex. Natan is just a womanizer, in Kent's rendition. I felt no loss at his death, rather that something foul had been cleaned from the beautiful, if desolate, farm where he and Agnes had lived. To make Agnes echo Gudrún, Kent needed to make Natan more rounded, more sensitive, more appealing, more like the prized and powerful member of society that Kjartan is--at whose death every reader weeps.

I do have one complaint with Kent's approach. There's a bit of the medieval Laxdaela Saga plunked into the last quarter of Burial Rites. A line of the saga--"I was worst to the one I loved best"--is used as the epigraph. To someone, like me, who has studied Laxdaela Saga it's a puzzling inclusion. I can't imagine what someone who's never read Laxdaela Saga would make of it, but to me the comparison between Gudrún of Laxdaela Saga and Agnes is belittling to both stories. The motives of both women are reduced to mere jealousy, whereas there's no comparison between Kjartan (whose death Gudrún masterminded) and Natan (whom Agnes is convicted of killing). The Kjartan-Gudrún love story is tragically complex. Natan is just a womanizer, in Kent's rendition. I felt no loss at his death, rather that something foul had been cleaned from the beautiful, if desolate, farm where he and Agnes had lived. To make Agnes echo Gudrún, Kent needed to make Natan more rounded, more sensitive, more appealing, more like the prized and powerful member of society that Kjartan is--at whose death every reader weeps.But then Burial Rites would have been a different book. And not, I don't think, a better one. As it is, I just skimmed the pages from Laxdaela Saga and continued on. If I ever meet Hannah Kent (and I hope I do, in Iceland), perhaps we can have a cup of tea and discuss her reading of Laxdaela Saga. It's the kind of thing people do all the time in Iceland: examine each other's understanding of the past.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And if you would like to go to Iceland with me next summer, check out the tours at America2Iceland.com.

Published on January 15, 2014 06:12

January 8, 2014

The Faraway Nearby

Last June, on my way to Iceland for the 17th time, I read a luminous essay, "Summer in the Far North," in the magazine Mother Jones. It began, "One summer some years ago, on a peninsula jutting off another peninsula off the west coast of Iceland, I lived among strangers and birds."

Last June, on my way to Iceland for the 17th time, I read a luminous essay, "Summer in the Far North," in the magazine Mother Jones. It began, "One summer some years ago, on a peninsula jutting off another peninsula off the west coast of Iceland, I lived among strangers and birds."The writer, Rebecca Solnit, loved the birds, especially the arctic terns: "The impeccable whiteness of their feathers, the sharpness of their scimitar wings, the fierceness of their cries, and the steepness of their dives were all enchanting." She wove a story out of these birds, who migrate from the Arctic to the Antarctic each year, living their entire lives in light.

She contrasted them to herself, finding she could not live without darkness--of which there is none, naturally, in Iceland in the summertime. Fleeing the midnight sun, Solnit found darkness in an art museum, in an installation by a young Icelandic artist, "a zigzag route of Sheetrock" that allowed in only slivers of light. Inside "Path" by Elín Hansdóttir--essentially a box inside the box of the building--Solnit could riff on "empathy." Her essay ends: "Few if any of us will travel like arctic terns in endless light, but in the dark we find ourselves and each other, if we reach out, if we keep going, if we listen, if we go deeper."

I was intrigued. Solnit was so evocative writing about Iceland's birds, I wondered what she'd say about the "strangers." I clicked on the link, "Buy this Book," The Faraway Nearby, from which the essay was excerpted. It arrived while I was in Iceland and sat on my "to read" shelf for several months, as I began writing a new book myself, one inspired by that light-filled trip to Iceland (#17) last June, a book that brought me back to Iceland for trip #18 in dark and gray November.

I was intrigued. Solnit was so evocative writing about Iceland's birds, I wondered what she'd say about the "strangers." I clicked on the link, "Buy this Book," The Faraway Nearby, from which the essay was excerpted. It arrived while I was in Iceland and sat on my "to read" shelf for several months, as I began writing a new book myself, one inspired by that light-filled trip to Iceland (#17) last June, a book that brought me back to Iceland for trip #18 in dark and gray November.In early December, missing Iceland, I opened Solnit's book. I wanted a book about light and darkness and arctic terns and Icelanders. What I got was a book about a mother with Alzheimer's, a failed romance, a breast cancer diagnosis, fairy tales and Frankenstein, tale-telling in general, a heap of rotting apricots, Che Guevara, the Marquis de Sade, Peter Freuchen, Buddhism...

A reviewer for the New York Times (see http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/18/books/review/the-faraway-nearby-by-rebecca-solnit.html), whom I did not consult until after I'd finished The Faraway Nearby and was still wondering what it was "about," explains that "Creating links between seemingly disparate ideas is Solnit's gift, her stock in trade. It's what gives her writing its eccentricity, its spirit and frenetic energy. This worked well in her popular 2005 book, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, which explored all that the unknown had to offer." The reviewer implies that it does not work so well in The Faraway Nearby. I'm not so sure. That heap of rotting apricots was quite thought-provoking. I liked the "wild mash-ups," as the reviewer named them, of, for example, Narnia and the Chinese artist Wu Daozi and Easter Island and the Road Runner cartoons.

What disappointed me was that Rebecca Solnit never really went to Iceland. Sure, she resided on the island for a time. But her "Iceland" is not my Iceland. She didn't meet any Icelanders.

What disappointed me was that Rebecca Solnit never really went to Iceland. Sure, she resided on the island for a time. But her "Iceland" is not my Iceland. She didn't meet any Icelanders.Solnit was the first international writer-in-residence at an art museum in Stykkishólmur called the Library of Water. She writes:

I wandered around my temporary home on this island shaped like a heart, the volatile ice-covered heart that occasionally beat, with lava, boiling water, and steam in its veins. The farthest point I could reach on foot was Helgafell, the sugarloaf hill around which stories were wrapped like clouds, and where Gudrun Osvifursdottir was buried a thousand years before, the proud woman at the center of the Laxdaela Saga and all its slaughter and loss.

Once a farmer who spoke only Icelandic gave me a ride back from Helgafell in a rain; and cashiers spoke brusquely to me about money in the low-ceilinged, fluorescent-lit den that was the chain supermarket; and there was a librarian with some responsibility for the Library of Water who provided practical aid every now and again. Otherwise no one spoke to me because Iceland was not good at strangers ...

Helgafell, as I've written before on this blog, is my "thin place." See http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2013/03/a-thin-place-in-iceland.html

Helgafell, as I've written before on this blog, is my "thin place." See http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2013/03/a-thin-place-in-iceland.htmlIn my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color, I described how a visit to Helgafell had inspired me to write; an excerpt is here: http://nancymariebrown.blogspot.com/2012/06/practical-education.html

I can guess who the "farmer who spoke only Icelandic" might be who gave Solnit a ride, since I have been friends with the farmer at Helgafell (who speaks only Icelandic) for 27 years. It's something he would do. If she had tried a few words of Icelandic on him--even the few words she includes here in her book, "Gudrun Osvifursdottir" and "Laxdaela Saga"--he would have tried to speak with her. I know, because I did that and he spoke with me.

I walked up to the door at Helgafell in 1986, knocked and said, "Snorri Godi, here?" I was greeted with a warm handshake and invited in for coffee. My husband waved his binoculars and said, "Hrafn" (Raven). Through some combination of English, Icelandic, and hand-waving, he conveyed to the family that had clustered around us that he had found a raven's nest on the side of the hill. Turns out the mother had been looking for that nest. After coffee and cakes, we took a field trip to see it. We were invited to stay for dinner (fresh trout from their lake) and to set up our tent in the yard. The family called up the local English teacher to come translate.

I decided right then to learn Icelandic so that I could speak to this remarkable family. But they are not the only Icelanders I've met who are "good at strangers."

A few days later, I got off a ferry in the driving rain and was struggling into my rainsuit when a car stopped and a stranger approached me. She knew a little English. "You look cold," she said. "Would you like coffee?" She motioned for us to follow the full car to a yellow house and, instead of birdwatching in the rain, we spent the afternoon warm and snug and well-fed, "talking" about birds with another large, extended family who spoke little or no English.

A few days later, I got off a ferry in the driving rain and was struggling into my rainsuit when a car stopped and a stranger approached me. She knew a little English. "You look cold," she said. "Would you like coffee?" She motioned for us to follow the full car to a yellow house and, instead of birdwatching in the rain, we spent the afternoon warm and snug and well-fed, "talking" about birds with another large, extended family who spoke little or no English.In 1992, I took the same ferry to the same island and knocked on the door of the yellow house. Our hostess was not there--turns out she shared this summerhouse with 13 siblings--but we were welcomed in and fed, regardless. That afternoon being sunny, a young nephew (who did speak English) offered to take us out in his small boat to see a colony of guillemots that nested on a nearby islet.

I have been to Iceland, as I said, 18 times--the 19th trip is already scheduled. I have never met a cold Icelander, an Icelander "not good at strangers." What I have met are the warmest and most hospitable people I can imagine. People who will not accept a gift without giving one in return. People who have piled gifts upon me--of food, of comfort, of stories, of adventures--that I can never repay except, I hope, by writing about them and the larger gifts Icelanders over the centuries have given to the world.

According to the New York Times, Rebecca Solnit's book is "loosely about storytelling." It's too bad she didn't discover the best and most influential storytellers in the world, the medieval Icelanders like Snorri Sturluson who gave us Norse mythology and the Icelandic sagas.

In Song of the Vikings, my biography of Snorri, I list some writers Iceland has inspired:

In Song of the Vikings, my biography of Snorri, I list some writers Iceland has inspired:Thomas Gray, William Blake, Sir Walter Scott, the Brothers Grimm, Thomas Carlyle, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, Richard Wagner, Matthew Arnold, Henrik Ibsen, William Morris, Thomas Hardy, Hugh MacDiarmid, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jorge Luis Borges, W.H. Auden, Gunther Grass, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, A.S. Byatt, Seamus Heaney, Jane Smiley, Alice Munro, Ivan Doig, Michael Chabon, and Neil Gaiman.

Through Tolkien, Snorri has inspired dozens of writers of fantasy, including Douglas Adams, Lloyd Alexander, Poul Anderson, Terry Brooks, David Eddings, Lester del Rey, J.V. Jones, Robert Jordan, Guy Gavriel Kay, Stephen King, Ursula K. LeGuin, George R.R. Martin, Anne McCaffrey, and J.K. Rowling.

These writers are just a beginning. There are many, many more--every day, I find more--Rebecca Solnit among them.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world. And if you would like to go to Iceland with me next summer (on my 19th trip), check out the tours at America2Iceland.com.

Published on January 08, 2014 07:49

January 1, 2014

New Book: The Ivory Vikings

What am I working on in 2014? A new book about Iceland, Vikings, and medieval history. Here's the official "pitch":

What am I working on in 2014? A new book about Iceland, Vikings, and medieval history. Here's the official "pitch":In the early 1800s, on a golden Hebridean beach, the sea exposed an ancient treasure cache: ninety-three game pieces carved from walrus ivory and the buckle of the bag that once contained them. Seventy-eight are chessmen—the Lewis chessmen—the most famous chessmen in the world. Between one and five-eighths and four inches tall, these chessmen are Norse netsuke, each face individual, each full of quirks: The kings stout and stoic, the queens grieving or aghast, the bishops moon-faced and mild. The knights are doughty, if a bit ludicrous on their cute ponies. The rooks are not castles but mail-shirted Vikings, some going berserk, biting their shields in battle frenzy. Only the pawns are lumps—and few at that, only nineteen, though the fourteen plain disks could be pawns or men for a different game, perhaps something like backgammon. Altogether, the hoard held almost four full chess sets—only one knight, four rooks, and most of the pawns are missing—about three pounds of ivory treasure.

Who carved them? Where? Why were they buried in a sandbank or a secret chamber on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides? These mysteries The Ivory Vikings will explore by connecting medieval sagas to modern archaeology, art history, forensics, and the history of board games. In the process, The Ivory Vikings will present a history of the Vikings in the North Atlantic, when the sea-road connected countries and islands we think of as far apart and culturally distinct: Norway and Scotland, Ireland and Iceland, the islands of the Hebrides and Orkneys, and even Greenland and Norse North America. The story of the Lewis chessmen explains the economics behind the Viking voyages to the west. It illuminates the Viking impact on Scotland and shows how the whole North Atlantic was dominated by Norway for over 400 years, from the early 800s until the mid-1200s, when the Scottish king finally reclaimed his islands. The story of the Lewis chessmen reveals the struggle within Viking culture to accommodate Christianity, the ways in which Rome’s rules were flouted, and how orthodoxy eventually prevailed. And finally, the story of the Lewis chessmen brings from the shadows an extraordinarily talented woman artist of the twelfth century: Margret the Adroit of Iceland.

The Ivory Vikings will be published in New York and London by Palgrave Macmillan in Spring 2015. Time for me to get to work.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland and the medieval world.

Published on January 01, 2014 09:00

December 25, 2013

Now in Paperback!

Thanks to my publisher, Palgrave Macmillan, for my best Christmas present: the paperback edition of Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths.No gift wrap necessary.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on December 25, 2013 09:06

December 18, 2013

Music for Saint Thorlak's Day

Last November, I spent a few days at Skalholt, the medieval capital of Iceland and site of its first cathedral. While there, I began understanding the Icelanders' fondness for their patron saint, Thorlak Thorhallsson, who was bishop of Skalholt from 1178 to 1193 and declared a saint in 1198.

Last November, I spent a few days at Skalholt, the medieval capital of Iceland and site of its first cathedral. While there, I began understanding the Icelanders' fondness for their patron saint, Thorlak Thorhallsson, who was bishop of Skalholt from 1178 to 1193 and declared a saint in 1198.November days are very short in Iceland. Through a fluke of scheduling, I was completely alone in the cathedral guesthouse. It was eerie, walking around the grounds at night--even before the storm came--and I soon imagined I heard voices in the babbling of the brook and the whinny of a distance horse. There could, indeed, be a lot of ghosts at Skalholt: I knew its history. Though not a "believer" I found I had Saint Thorlak's name on my lips and rushed back inside, where a gift from the current bishop of Skalholt awaited me.

Since December 23rd is Saint Thorlak's Day, I thought I'd share that gift. But first, a bit about Thorlak, whom I met while researching Song of the Vikings, my biography of Snorri Sturluson.

Thorlak was a well-educated man: He studied at Paris, France and Lincoln, England. After that he returned to Iceland and "was ever at writing," his saga says. He dressed plainly, ate and drank like an ascetic (no meat, only water), and was rather dull company, the saga implies, noting that it "was a great misfortune that his speech was hard and slow." On the other hand, "he was so lucky in his brewing that the ale never burst that he had blessed."

Soon after Thorlak died, people began reporting miracles that occurred when they called on him for aid. These miracles provide a digest of the common Icelander's woes in the 12th century: Saint Thorlak cured stiff hands, sore throats, burning eyes, and gassy stomachs. He found lost hobbles, lost sheep, a sledgehammer, and a ring. He healed a horse ridden "unwarily where there was volcanic heat"; its legs "got so burned that people thought it would die." He healed a woman who "fell into a hot spring in Reykholt and got so severely burned that her flesh and skin came off with her clothes." He stemmed the flow of blood when a chieftain, soaking in his hot-tub, cut himself with a razor. He calmed storms and floods, resuscitated a drowned boy, quenched a house fire, and mesmerized a seal so a starving mother could kill it.

In Song of the Vikings I describe these miracles, along with the glorious translation of Bishop Thorlak—the ceremony by which he was officially recognized as Iceland's first saint in 1198.

In Song of the Vikings I describe these miracles, along with the glorious translation of Bishop Thorlak—the ceremony by which he was officially recognized as Iceland's first saint in 1198.The bishop's coffin, buried for five years, was dug up, dusted off, and carried into Skalholt Cathedral. Saint Thorlak's holy relics (his bones) were taken from the coffin, washed, and encased in a golden shrine. The priest Gudmund the Good, then 38, was a coffin-bearer; he chanted the Te Deum in his unforgettable voice. Twenty-year-old Snorri probably accompanied his foster-brothers Saemund and Orm, whom the saga says attended the ceremony. During the Mass which followed, Snorri would have marveled at the 230 expensive beeswax candles twinkling on the altar (all imported, since honeybees did not live in Iceland).

But what I didn't know when I wrote Song of the Vikings was that the music written for the ceremony still survives. On my recent trip to Skalholt, Bishop Kristjan Valur Ingolfsson lent me a recording of it by the early-music ensemble Voces Thules.

You can listen to part of it here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=emmG7Pl3mCU

As explained in the CD's liner notes, "Liturgical chants are a kind of soothing incantation, in which flow has an all-important role to play, like sailing effortlessly on the crest of the wave toward a nevertheless clear destination. The singing of music of this kind is the most intimate form of worship and meditation still to be preserved within the sanctuary of the Christian Church."

As explained in the CD's liner notes, "Liturgical chants are a kind of soothing incantation, in which flow has an all-important role to play, like sailing effortlessly on the crest of the wave toward a nevertheless clear destination. The singing of music of this kind is the most intimate form of worship and meditation still to be preserved within the sanctuary of the Christian Church."The six members of Voces Thules depended on the doctoral thesis of Robert Ottosson (1912-74) to understand how to reconstruct this chant from the 24 pages of manuscript in the archives. These manuscript pages are also online; you can see them at the Icelandic music website www.ismus.is. Click on "Handrit og prent," then on manuscript number "AM 241a fol. Þorlákstíðir," then on "Síður (24)" and the pages of manuscript will appear and you can scroll down through them.

The "Office of Saint Thorlak" was performed in 1998, for the first time in centuries, to mark the 800th anniversary of Bishop Thorlak's death. It was part of the Reykjavik Arts Festival that year, stretching over a day and a half and culminating in a High Mass, at which Kristjan Valur and another priest also sang.

I listened to Saint Thorlak's music at Skalholt on that dark November night, while the wind howled and the rain lashed against the windows and I was the only person in the entire guesthouse.

"The darkness flees, the light illuminates the mind, a devoted nation dances," the Office begins. "Let us prepare for the festival of jubilation and offer praise, cast out the darkness at the world's extreme."

Join me again next week at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on December 18, 2013 08:28