Nate Silver's Blog, page 158

January 16, 2015

NFL Week 20 Elo Ratings And Playoff Odds: Conference Championships

This has not been an enormously surprising NFL season. The four teams remaining in the playoffs — the Seattle Seahawks, New England Patriots, Green Bay Packers and Indianapolis Colts — were well liked by Vegas bettors before the season began. There are a couple of compelling story lines surrounding Peyton Manning and the Denver Broncos. (Is Manning finished? Not necessarily. Is he a playoff choker? Not really.) But betting favorites have won six of eight playoff games so far, and the two upsets (Indianapolis over Denver last week; the Baltimore Ravens over the Pittsburgh Steelers two weeks ago) were fairly ordinary.

One of the great things about being a sports fan is that you can take some pleasure either way. Upsets are fun when they happen. But when they don’t, you get to see higher-quality opponents remain in contention. The joy football fans might take from the remainder of this NFL season is tilted toward the latter: We should have two compelling conference championship games this weekend, and they ought to produce a compelling Super Bowl.

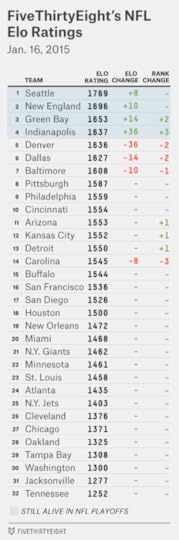

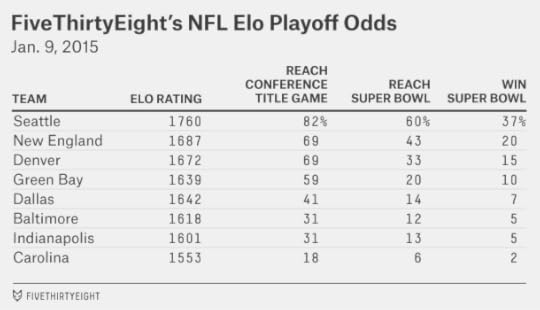

In fact, the four remaining teams rank Nos. 1 through 4 in FiveThirtyEight’s NFL Elo Ratings. The Colts were ranked No. 7 last week, but their big win over the Broncos was enough to vault them into the fourth position.

None of the remaining teams is a slouch. And one has a chance to finish among the best NFL teams of all-time.

The Elo ratings have a bird crush on the Seahawks. Only four previous teams (the 2004 and 2007 Patriots, the 1997 Packers and the 1983 Washington Redskins) have entered the conference championship game with a higher Elo rating.

So, is this the best conference championship field of all time? No, that’s getting a little carried away. But it’s well above average. Based on the average Elo rating of the four conference championship teams, it ranks seventh among the 45 seasons since the AFL-NFL merger in 1970. We’ve seen a shift away from the parity of the late 1980s and 1990s toward more dominant franchises.

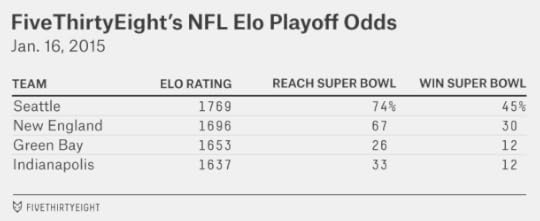

Seattle remains the Elo favorite to win the Super Bowl — as it was at the start of the season. Its chances of a repeat are up to 45 percent — not quite even money, but close — followed by the Patriots at 30 percent and the Packers and Colts at 12 percent each.

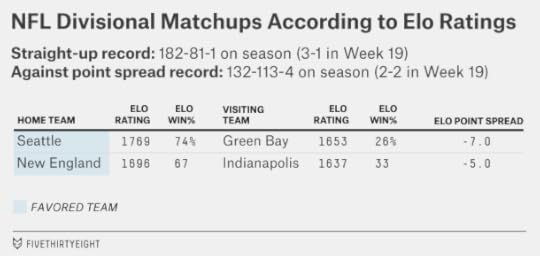

These probabilities are almost identical to those established by betting markets. Accordingly, the point spreads that Elo sets for the conference championship games — Elo has had a pretty good year against Vegas, but we don’t recommend that you bet on these — are largely in line with the gambling consensus:

Elo has Seattle favored by a touchdown over Green Bay, just as prevailing betting lines do. This is a bit surprising given how much Elo likes the Seahawks and how it’s been comparatively down on Green Bay. But Elo does not consider that the Seahawks may have an especially large home-field advantage.

In the AFC Championship game, Elo favors the Patriots by five points — consensus betting lines have New England as 6.5-point favorites instead. That’s a marginal difference. And as I’ve said, we wouldn’t recommend placing bets based on Elo ratings, especially given that it’s been unwise historically to wager against Bill Belichick and the Pats.

January 15, 2015

Expand The College Football Playoff

Ohio State’s national college football championship might seem to vindicate the playoff selection committee, which chose the No. 4 Buckeyes over two teams with similar resumes, No. 5 Baylor and No. 6 TCU. But there probably weren’t a lot of people in Waco or Fort Worth, Texas, celebrating the Buckeyes’ Monday night win. Instead, Baylor and TCU fans have every right to think their teams deserved the same opportunity.1

It has sometimes been stated — I’ve said it myself — that a four-team playoff is inherently flawed when there are five major conferences. The truth is a little more complicated than that. Sometimes a “Power 5” conference champion won’t have much of a beef with having been excluded from the playoff. In 2012, for instance, Wisconsin was the BCS representative as the Big Ten champion despite just a 4-4 conference record (and an 8-5 record overall). It was a wacky case — Ohio State and Penn State finished ahead of the Badgers but were ineligible for postseason play — but it’s not so uncommon to have an “ugly duckling” major conference champion.

But pretty much every other contingency complicates the committee’s job and adds to the list of teams it might consider:

Sometimes there will be an undefeated team from a “minor” conference, like Boise State.Sometimes independent Notre Dame or BYU will be undefeated or will have one loss against a strong schedule.Sometimes a second team from a power conference will have a powerful argument for being among the top four nationally. In 2011, for example, Alabama ranked No. 2 and was chosen for the BCS title game; its only loss had come against No. 1 LSU.In other words, this year wasn’t an outlier: A four-team playoff is liable to produce similar controversies more often than not. It may not be the particular controversy we had this year. But there’s liable to be some type of controversy.

This is usually the point at which someone asserts the problem is infinitely regressive. With four teams in the playoff, there will always be an argument over Nos. 4 and 5. With six teams, there might be the a debate over Nos. 6 and 7. Or with 68 teams, you’ll have a fight over Nos. 68 and 69.

I don’t find this case entirely convincing; you’re going to hit the point of diminishing returns eventually. In 2012, I participated in a

As you can see, these tiers do a reasonable job of reflecting how poll voters think about the teams. Sometimes the tiers get mixed up around the margins, but these are usually relatively obvious cases involving teams with especially strong or weak schedules.

But you can also see the problem. In an average year, there are one or two first-tier teams and four or five second-tier teams. A four-team playoff will wind up splitting the second-tier teams right down the middle.

What if you’re willing to omit one-loss teams that didn’t win their conference championships? In the chart, I’ve also indicated whether a team won its conference title. (I’ve listed just one champion per major conference — the team deemed as the conference champion by the BCS in the event of ties.4 There’s special handling for teams from the former Big East conference, which no longer exists for football.5) This gets you closer, but you’ll still run out of space fairly often unless you’re also willing to kick out undefeated teams from minor conferences.

Besides, it’s not clear that a conference championship ought to trump everything else. It’s great when, for example, the No. 3 and No. 5 teams in the country square off in their conference championship, making it serve as a de facto play-in game. But this rarely happens. Often, the two best teams in the conference are in the same division and won’t play for the conference title. Or there are cases like 2003, when Kansas State, which had two conference losses, beat undefeated Oklahoma in the Big 12 championship game. Would Kansas State really deserve to make the playoff ahead of Oklahoma? AP voters didn’t think so. (They ranked Oklahoma No. 3 and Kansas State No. 8 the next week.)

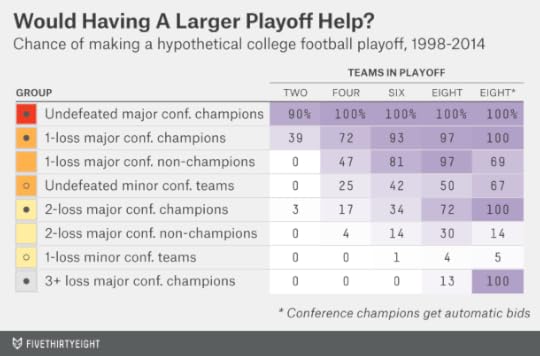

What if we expand the playoff to six teams instead?

Now we’re able to accommodate the clear majority of the second tier. One-loss major conference champions will just about always make it. One-loss non-champions from major conferences will make it about 80 percent of the time. Undefeated teams from minor conferences still struggle a bit, but overall this seems to strike a good balance. As a major conference team with just one loss, you’ll make the playoff unless there’s a lot working against you. With two losses, you’ll won’t make it unless you have a lot working for you. There are still some tough decisions to be made, but the committee won’t have to cleave the second tier in half, as it often will under a four-team playoff.

If you expand the playoff to eight teams, you’re able to accommodate almost all of the second tier. However, about 75 percent of the additional teams you’d add with the seventh and eighth slots are from the third tier instead. This may be too tolerant, placing too little pressure on teams to perform and schedule well in the regular season.

An alternative would be to include eight teams, but with automatic bids for major conference champions. (Technically you could do this under a six-team playoff, too, but it might not be advisable.6) Presumably, teams from outside of the power conferences would object to this, but you could accommodate them by guaranteeing a sixth slot to the best independent or minor conference team. That would leave two at-large positions.

I’ve run the numbers on how this would work out — and it seems like another good option. By definition, we’re now including every major conference champion. While you’d have the occasional fluke conference champ like the 2012 Wisconsin team, that might be an acceptable price for reducing the subjectivity in the process. Non-champion teams from major conferences would sometimes make the playoff but would have a lot of pressure to schedule well and perform well. The majority of one-loss teams from major conferences would make it, but they’d be at risk if they fail to win their conferences. And taking a second loss would knock a team out the vast majority of the time.

No system is going to end the debates; people still argue about which teams ought to be No. 12 seeds in the NCAA hoops tourney so they can lose to Kentucky in the Sweet 16. But expanding the football playoff to six teams — or to eight teams with some automatic bids — would do a better job of rewarding the most deserving teams while preserving the importance of the regular season. It would help to ensure the most important decisions of the college football season happen on the field and not in a conference room.

January 14, 2015

We’re Hiring A Managing Editor

FiveThirtyEight’s managing editor, Mike Wilson, is leaving at the end of the month to become editor of The Dallas Morning News. We’re thrilled for Mike, but we’re looking for his replacement.

This is a big job for someone with extensive experience — ideally, having run a newsroom or large news desk at a major media outlet — and an ambitious vision for data journalism. Our managing editor will set FiveThirtyEight’s editorial direction, manage our growing staff of 20-plus journalists and recruit new hires, and run the site day to day from FiveThirtyEight’s New York newsroom.

What should FiveThirtyEight look like in two years? What big projects should we tackle? What have we gotten wrong so far? How can we push our boundaries and expand our audience while retaining our editorial values?

If you want to help us answer those questions, please send me an e-mail at nathaniel.silver@fivethirtyeight.com. You can apply for the job at the ESPN careers website. We hope to hear from some of you soon.

January 12, 2015

Romney And The GOP’s Five-Ring Circus

There have been rumors for months that Mitt Romney might run for president again in 2016. On Monday afternoon, though, The Washington Post’s Robert Costa, Philip Rucker and Karen Tumulty — three top-notch journalists — reported that Romney was reassembling his campaign apparatus and had told a senior Republican he “almost certainly will” run. The news came on the same day that Paul Ryan, Romney’s running mate in 2012, said in an interview that he wouldn’t run for president.

What is Romney thinking? Candidates who lose general election campaigns don’t have a good track record when they’ve tried to run again. But as my colleague Harry Enten pointed out last week, Romney isn’t nuts to think he has a shot. The GOP field is historically divided, and Romney has more experience than anyone else in the party uniting (or at least placating) its constituencies. And Romney is vetted, skilled at raising money and starts out with near-universal name recognition.

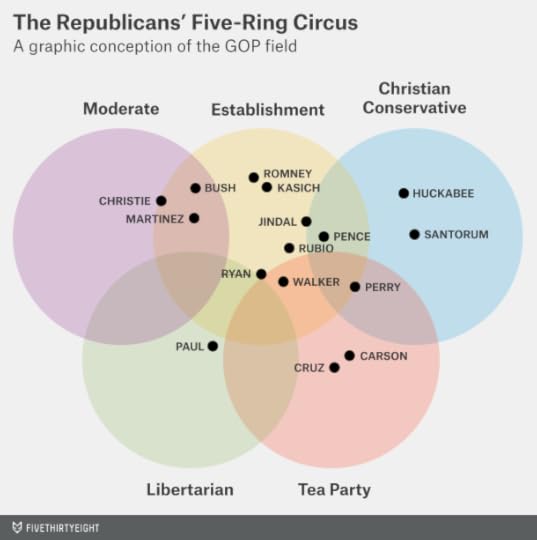

But Romney also enters a crowded field. In the past, we’ve sometimes conceived of the GOP field with a Venn diagram that we call the “five-ring circus.” It portrays the major constituencies within the party — the establishment wing, the moderate wing, the tea party, libertarians and Christian conservatives — and how they overlap. Here’s how we think of things as shaping up so far for 2016:

The chart is an oversimplification, but it recognizes the GOP’s dynamics are more complex than a simple left-right spectrum would imply. Some wings overlap more with others. For instance, a candidate could easily have a lot of appeal to both tea party and libertarian voters. But it’s unlikely that one candidate would simultaneously be the choice of both Christian conservatives and moderate voters.

The establishment constituency plays an especially important role because it overlaps with all other groups and seeks to unify the party. And it’s a good place to be — usually the eventual nominee comes from its ranks. The downside is that, because it’s a desirable space, the establishment field is usually crowded.

That’s especially true this year. Apart from Romney, other candidates that I’d classify as belonging within the establishment ring include Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Bobby Jindal and Scott Walker. Some of these candidates overlap with one or more of the other groups; Bush, for instance, is somewhere between being an establishment and a moderate candidate. (Chris Christie, I’d argue, is closer to being a true moderate.) Walker is somewhere between an establishment and tea party candidate. Paul Ryan, if he had run, might have been somewhere near the three-way border between establishment, libertarian and tea party.

Romney, having calibrated his positions in 2008 and 2012 in seeking to become the GOP’s consensus choice, sits squarely within the middle of the establishment. However, he could potentially be boxed in. While The Washington Post report suggests that Romney could run somewhat to his right to distinguish himself from candidates such as Bush and Christie, Christian conservatives could find more appealing choices in the form of Mike Huckabee and Rick Santorum. Walker could be more attractive to voters who dabble in the tea party, while Ted Cruz and Ben Carson will appeal to those who fully embrace the label. Rand Paul, although he’s seeking to make inroads with establishment and tea party voters, should have the libertarian wing of the party locked up.

Not all of these candidates will run. Part of Romney’s goal will be to pare down the field during the “invisible primary,” convincing influential Republicans that Bush is too moderate, that Rubio isn’t ready, that Paul is too far afield and so forth. Romney’s experience and resources should help him, although the field looks to be more crowded than it was in 2012.

Establishment candidates also seek to portray themselves as being highly electable, or at least the most viable sufficiently conservative candidates. So perhaps the most important determinant of how far Romney gets will be how he’s able to make the electability argument — despite having just lost the election in 2012.

What narrative will Republicans tell themselves about why they lost with Romney at the top of the ticket? A case can be made that 2012 was a pretty tough election to win: Incumbents aren’t easy to beat, the economy had improved just enough to slightly favor President Obama, and Obama had a terrific turnout operation that the next Democratic nominee might not be able to match.

But this wasn’t the story that Republicans were telling themselves during and immediately after the 2012 campaign. Instead, many Republican thinkers saw the 2012 election as theirs for the taking and refused to believe polls that showed Obama with the edge. There were furious recriminations after Romney lost, blaming his polling, his vote-tracking software and his overall messaging. Other Republicans blamed what they said was the Democrats’ rising demographic tide — something that isn’t necessarily Romney’s fault, but which presumably wouldn’t be helped by nominating an aging white man (Romney will be 69 at the time of the 2016 general election) with conventionally conservative positions.

While Romney could perhaps beat out Bush, whose candidacy

The Most Clutch Postseason Quarterback Of All Time Is Eli Manning

Saturday’s AFC divisional playoff game featured a matchup between two quarterbacks with clutch reputations: the Baltimore Ravens’ Joe Flacco, who entered the game with a 10-4 lifetime postseason record, and the New England Patriots’ Tom Brady, whose first three playoff seasons all yielded Super Bowl championships. The Patriots got the better of the Ravens after a terrific game, but both quarterbacks played well, with Flacco tossing four touchdowns in a losing effort.

A day later, the Denver Broncos’ Peyton Manning would produce just 4.6 yards per passing attempt against the Indianapolis Colts, lower than in any of his 16 regular-season starts. While Manning avoided an interception, he threw just one touchdown and Denver lost 24-13. The effort rekindled doubts about Manning’s postseason performance — as you’ll recall, Manning’s most recent postseason appearance did not exactly go well — along with questions about whether he’s past his prime (he’s 38).

How you evaluate the postseason records of Manning, Brady and Flacco depends on how you define clutch performance. Is it performance relative to expectations that matters? Or is it performance in an absolute sense?

Manning’s postseason record is pretty decent by one standard and pretty terrible by the other. His lifetime postseason record is now 11-13. It’s not easy to win playoff games, and Manning has had the misfortune to play in a fairly deep era for the AFC (one that has included Brady). Nonetheless, Manning’s record is a bit worse than you’d expect based on the performance of his teams during the regular season.

In the chart below, I’ve tracked Manning’s postseason record as compared with expectation based on Elo ratings for his teams and his postseason opponents at the time the games were played. As an alternative measure — more about how this is calculated in a moment — I’ve charted how Manning’s teams would expect to do in those games if he had fallen into the Springfield Mystery Spot and a replacement-level quarterback had substituted for him.

Manning’s teams have been favored, according to our Elo ratings, in 17 of his 24 postseason games. It’s often been a narrow advantage; viewed probabilistically, you’d set the over line at 13 or 14 wins. Manning has won 11. It’s not a totally disastrous record — Manning has won a Super Bowl, after all, and led his team to two others — but it’s on the lower end for great quarterbacks relative to the lofty expectations they establish.

But what if those starts had instead been taken by backups like Jim Sorgi or Curtis Painter or Brock Osweiler (all of whom serve as functional examples of replacement-level quarterbacks)? We have the Broncos and the Colts as underdogs in all 24 of those hypothetical games. No doubt they’d have backed into a few wins despite their underdog status, but Manning’s teams project to an 8-16 record on a probabilistic basis without him. Peyton’s 11-13 record looks pretty good compared to that.

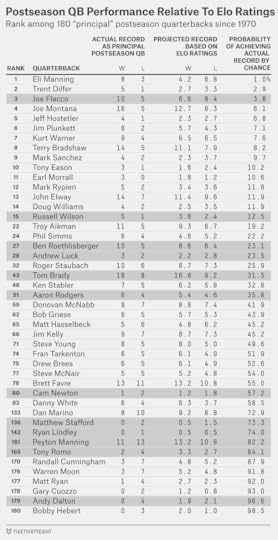

We can run the same numbers for all quarterbacks who played in the postseason since the AFL-NFL merger in 1970. Specifically, I’ll look at the records for what I’ll call the principal quarterback, who is the one with the most passing attempts during the game (not necessarily the one who started it). A total of 180 players have served as principal postseason QBs by this definition.

Below, I’ve listed the records for the top and bottom quarterbacks, along with those who have been active in this year’s playoffs or who have been a principal quarterback at least 10 times in the postseason. I’ve also listed each quarterback’s projected record based on Elo. Finally, I’ve listed the result of a set of 25,000 simulations of each quarterback’s postseason career where QBs were randomly assigned wins and losses based on the probabilities established by Elo. I counted up how often the simulated quarterback bettered the actual quarterback’s win total, giving half-credit to cases where they finished with the same record.

By this measure, the most clutch postseason QB of all time is Manning — Eli Manning. His New York Giants have often been underdogs in the postseason and projected to a record of 4-7 or perhaps 5-6 in his 11 games. Instead, Eli Manning’s teams have gone 8-3. According to the simulations, there’s just a 1 percent chance of achieving such a strong record based on chance alone.

This does not, incidentally, serve as evidence that Eli Manning or any other quarterback has some extra gear that kicks in during the postseason. Eli’s been awesome during the postseason, but with 180 QBs in the sample you’d expect to find a few fluky cases based on chance alone. This is also not to say that clutch quarterbacking doesn’t exist. As my colleague Benjamin Morris has repeatedly documented, some quarterbacks — including Peyton Manning — consistently manage the game better in clutch situations, such as during a fourth-quarter comeback drive. Indeed, clutchness is so intrinsic to quarterbacking that it’s hard to distinguish a clutch QB from a good QB. But that clutchness ought to show up in a QB’s regular-season stats and his team’s regular-season win-loss record and Elo rating. It’s not clear that some quarterbacks are clutch in the regular season but unclutch in the postseason.

Peyton Manning, of course, is the closest thing to an exception. As compared with the record projected by Elo, his postseason record ranks 161st out of the 180 QBs in our sample. Among quarterbacks with at least 10 games in the database, only Warren Moon and Randall Cunningham rank lower.

But this is a somewhat ridiculous list. The top five consists of one great quarterback, Joe Montana, along with two pretty good ones (Eli Manning and Flacco). It also has Trent Dilfer and Jeff Hostetler. Meanwhile, Brady ranks just 43rd by this measure. His postseason record is excellent — 18-8, not counting one game where he was hurt and replaced by Drew Bledsoe. But because the Patriots were favored in most of those games, he doesn’t get much credit for it. You’d have expected them to go about 17-9 based on Elo ratings.

Here’s the problem: This way of thinking about quarterbacks forces them to compete against themselves. Sure, the Patriots have often been favored to win their postseason games. But a lot of that is because Brady is their quarterback. How might the Pats have expected to do with a replacement-level QB instead?

They might not have been totally hopeless. Brady has usually had a little bit more talent surrounding him than Peyton Manning has. (Matt Cassel, who rates as somewhere between average and replacement-level, led New England to an 11-5 record when Brady was hurt in 2008.) Bill Belichick would probably have snuck them into the playoffs a few times. But they’d also have been playing good opponents. Our method projects them to a 12-14 or 13-13 postseason record rather than Brady’s 18-8.

I calculate these estimates based on a quarterback’s adjusted net yards per attempt (ANY/A), a metric that accounts for yardage, attempts, touchdowns, interceptions and sacks — basically it’s a better version of the NFL’s passer rating. A replacement-level quarterback typically posts an ANY/A at about 80 percent of the league average, so a QB gets credit for any performance above and beyond that.1 I then translate this into points added or subtracted in the regular season2 and translate points into a team’s Elo rating to evaluate the impact the QB had on his team overall.3

It’s notoriously difficult, of course, to distinguish the performance of a quarterback from that of his teammates, but this method produces some reasonable-seeming results. This year’s Green Bay Packers project as a slightly below-average team with a replacement-level guy subbed in for Aaron Rodgers , for instance. Instead of having been 59 percent favorites in their Sunday game against the Cowboys, as they were based on Elo ratings, they’d have been roughly 2-to-1 underdogs.

The principle is simply that the better the quarterback, the more his team would be harmed by removing him. In the case of Peyton Manning’s teams, I estimate that pulling Manning would hurt them by about a touchdown (7 points) per game. That’s enough to demote them to a projected 8-16 record in the 24 postseason games Manning has played.

We can rerun the numbers for all 180 playoff quarterbacks, comparing each QB’s actual record against the simulated one achieved by replacement-level QBs against the same schedule. By this measure, Peyton Manning moves up to 28th on the postseason list; there’s only about a 10 percent chance that a replacement-level QB could have equalled or bettered his 11-13 record.

Eli Manning remains No. 1 overall, but this time in a photo finish over Joe Montana and Kurt Warner. Flacco still rates highly, in fourth place. Brady moves up to No. 6, right behind John Elway. Brett Favre advances to 19th from 78th. While there’s still a Dilfer and a Hostetler here and there, it’s a much better list of quarterbacks.

This shouldn’t be surprising: Before, we’d essentially been punishing great QBs for having been great during the regular season. Some have been even greater during the playoffs. Others have reverted to being a little closer to average. Peyton Manning falls into the latter group. His career postseason passer rating entering Sunday’s game was 89.2, less than his 97.5 rating during the regular season but still pretty good. But if the Colts and Broncos haven’t quite had the postseason records you’d hope for with Manning at the helm, they’ve been a heck of a lot better off than they would’ve been with Jim Sorgi.

January 9, 2015

Week 19 NFL Elo Ratings And Playoff Odds: Divisional Round Edition

One blind spot of the analytics movement has been its underappreciation of postseason play. I don’t necessarily mean that “COUNT THE RINGZ” is a better paradigm. But there are all sorts of interesting empirical questions raised by the playoffs that analysts have sometimes ignored. Are the factors that yield postseason success different than those that bring it in the regular season? How much should postseason play be weighted when predicting future performance? Too often, postseason play is written off as a crapshoot — Billy Beane’s shit doesn’t work in the playoffs — and then not much more is written about it.

That characterization may be largely accurate in baseball, where even the best teams have no more than a small edge in a playoff series. In the NBA, by contrast, a team’s advantage can be more definitive, and a team almost never wins the NBA title as a fluke.

The NFL playoffs are somewhere in between. The sample sizes are tiny: With a one-and-done playoff structure, the league plays only 11 playoff games each year. But those playoff contests have a lot of empirical significance. Postseason games usually involve two strong teams, and games between closely matched opponents usually reveal more about team quality than lopsided ones. Nor will teams rest key players in the NFL playoffs, as they sometimes do in the regular season, or sacrifice the opportunity to win that day for the sake of developing young players.

In any event, one nice aspect about FiveThirtyEight’s NFL Elo ratings is that they integrate regular-season performance and playoff performance seamlessly. Here’s how the ratings changed after the wild card games the league played last week.

There was almost no movement at the top of the table, in large part because the four teams that Elo had rated highest going into the week all had byes. But there will be more movement in the standings as we run deeper into the playoffs. Elo doesn’t explicitly place a larger weight on playoff games, but in practice they can have a lot of impact — because they’re the most recent games in a team’s portfolio (Elo weights recent games more heavily), and they involve top teams matching up against each other. Ordinarily, it would be hard for the Indianapolis Colts (ranked No. 7) to make up its 71-point Elo deficit with the Denver Broncos in a single week, for instance. But because the teams will play each other Sunday, any Elo gains for Indy will come directly at Denver’s expense.

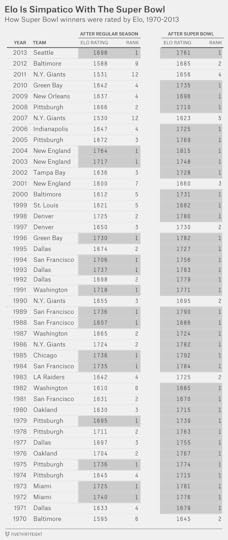

As a result, Elo usually winds up agreeing that the Super Bowl winner was the best team in the league. We’ve run historical Elo ratings back to 1970, or for 44 seasons not counting the current one. In 36 of those 44 cases (82 percent), Elo ranked the Super Bowl winner highest at the end of the season.

Of course, Elo matches the Super Bowl winner 82 percent of the time only with the benefit of hindsight. As we described last week, the team ranked No. 1 in Elo before the playoffs start wins the Super Bowl only 34 percent of the time. Still, it’s rare to find a Super Bowl winner that we can say was truly lucky or “undeserving”; it may have been instead that we overlooked the team during the regular season. There are often cases like the 2000 Baltimore Ravens, who jumped from No. 5 in the Elo standings at the end of the regular season to No. 1 after winning the Super Bowl, defeating the teams that had previously ranked Nos. 1 and 2 (the Oakland Raiders and Tennessee Titans) along the way. The one real exception is the 2007 New York Giants, who upset the undefeated New England Patriots in Super Bowl XLII; even knowing that result, Elo would still have favored the Patriots by more than a touchdown if the teams had played a rematch the following week.

The Seattle Seahawks remain the best bet to win this year’s Super Bowl, according to Elo. In fact, their chance of doing so improved slightly, to 37 percent from 35 percent last week despite their being idle. That’s because Seattle will face the Carolina Panthers, the weakest team to make the playoffs. By contrast, the odds for the Patriots, the No. 1 team in the AFC, have fallen slightly because they’ll have to face Baltimore after the Ravens gained more Elo points than any other team in beating the Pittsburgh Steelers last week.

Elo most differs from the conventional wisdom in its assessment of the Dallas Cowboys-Green Bay Packers matchup. While Vegas odds had the Packers as six-point favorites as of Friday afternoon, Elo has the Pack as 2.5-point favorites instead, essentially giving the team credit for its home-field advantage and nothing else. There are all sorts of additional factors you’d want to evaluate before betting on this game — in particular, Aaron Rodgers’s health and the weather at Lambeau Field — but it looks like the best matchup of the week.

January 7, 2015

Chris Christie’s Chances Are Overrated

The Washington Post’s Chris Cillizza has New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie as the second most likely Republican presidential nominee after Rand Paul. University of Virginia political scientist Larry Sabato lists Christie as one of the top four candidates, along with Paul, Jeb Bush and Scott Walker. And the betting market BetFair had Christie as the fourth most likely as of midmorning Tuesday.

These assessments seem much too bullish; Christie has three fundamental problems that are likely to prevent him from becoming the GOP’s candidate. It might be possible to overcome any one of these, but two is very difficult and three is almost impossible.

He’s probably too moderate. Last month, I addressed Bush’s candidacy and sought to evaluate whether Bush is too moderate to become the nominee. It’s a close call. Bush is not that much more moderate than Mitt Romney or John McCain, the past two Republican nominees. But the party has become more conservative since 2008, and it has a deep field of potential 2016 candidates. Republicans can afford to be picky. So far, Bush’s candidacy has

Indeed, Christie takes moderate positions on the very issues where Bush notoriously deviates from the party base — such as immigration and education — along with others where Bush lands in the GOP mainstream, like on gun control. (Christie has a C grade from the National Rifle Association.) Any voter who opposes Bush for ideological reasons probably won’t find a lot to like in Christie either.

He probably lacks the discipline to win the “invisible primary.” The candidates who survive the early stage of the invisible primary tend to be those who avoid making news when they don’t need to. Donors and other influential Republicans won’t want to nominate a candidate who will risk blowing a general election because of a gaffe or scandal that hits at the wrong time.

So, what to make of something like Christie having been spotted in a luxury box in Arlington, Texas, on Sunday, where he joined Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones to watch the Cowboys’ 24-20 comeback win over the Detroit Lions? (Unlike certain politicians, Christie doesn’t seem to have mastered the art of rooting for a team from a swing state.) It seemed like a silly controversy until it was revealed that a company co-owned by the Cowboys was recently awarded a contract by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Whether there’s actual impropriety or just the appearance of it, it was a dumb place for Christie to be seen if he’s contemplating a presidential bid. A presidential campaign is a long and mostly dull thing, and reporters chase down the serious and silly stories alike.

Christie’s transgressions against Republican orthodoxy and tendency to make the wrong kind of news can amplify one another. If Christie were seen as a staunch conservative, Republicans might be more inclined to rally around him and critique the “liberal media” for persecuting him. But Christie has not always been a team player for the GOP. His speech at the 2012 Republican National Convention seemed to go out of its way to avoid praising Romney. And Christie’s embrace of President Obama as the two toured seaside communities hit hard by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 also rankled many in the GOP.

Republicans voters just aren’t that keen on Christie anymore (and they’re plenty familiar with him; he’s one of the most well-known Republicans). A Gallup survey in July found Christie with the lowest net favorability rating with GOP voters among the 11 Republicans that it tested.

He no longer has a good “electability” case. The decline in Christie’s favorability has also translated into his overall numbers. In late 2012, his favorability rating was 45 percent nationally against just a 20 percent unfavorable rating, according to Huffington Post Pollster. But Christie’s popularity has waned considerably in the wake of “Bridgegate” and other controversies. Now his ratings have turned negative; he has a 33 percent favorable rating and a 43 percent unfavorable rating, according to HuffPost Pollster. His head-to-head numbers against Hillary Clinton are no longer any better than those of fellow Republicans Bush and Mike Huckabee.

This isn’t catastrophic unto itself. There are lots of unpopular politicians in both parties. The head-to-head numbers don’t mean much yet, and many Republican voters would come around to Christie were he to win the nomination. But Christie’s case to Republicans is especially dependent on his perceived ability to win the general election. That’s the reward the GOP would get for putting up with the baggage Christie carries. Without it, it’s hard to see the Republicans’ rationale for choosing him.

January 1, 2015

Assessing Andrew Wiggins, 30 Games In

Last week, my colleague Neil Paine wrote about the Minnesota Timberwolves’ Andrew Wiggins, who is probably the favorite to win the NBA’s Rookie of the Year but who has so far been among the least efficient players in the league according to a variety of advanced statistics. The article triggered a lot of objections on Twitter and in the comments section. Many readers thought it was ridiculous to assess any player, especially a 19-year-old rookie, after just a couple dozen NBA games. Others were skeptical of the array of advanced statistics that Neil cited.

So let’s look at Wiggins’s case through the lens of traditional statistics instead. And let’s measure him directly against his peers. Wiggins played in his 30th NBA game on Tuesday night; we can compare his performance so far against other 19-year-old rookies through their first 30 games. I ran a search on Basketball-Reference.com for players who:

Were age 19 or younger in their rookie season (based on their age as of Feb. 1 of their rookie year);And who averaged at least 24 minutes per game (i.e. played at least half their teams’ minutes) during their first 30 NBA games.Since 1985-86 there have been only 15 such players (counting Wiggins). The list puts Wiggins in pretty good company. It includes a number of superstars and All-Stars, among them LeBron James, Kevin Durant, Carmelo Anthony, Anthony Davis, Dwight Howard, Tony Parker and Chris Bosh. There are only one or two total busts, most notably Dajuan Wagner. The rest of the list includes players, such as Luol Deng, who turned into good NBA regulars, and others like Michael Kidd-Gilchrist about whom it’s too early to make an assessment.

But in other respects the data is less favorable for Wiggins. When comparing his first 30 games against the first 30 games of those other players, he’s been among the least effective. In the chart below, I’ve listed each player’s statistics per 36 minutes played in the 10 categories that are most commonly used in rotisserie basketball leagues: points, rebounds, assists, blocks, steals, turnovers, personal fouls, 3-pointers made, field goal percentage and free-throw percentage. (For personal fouls and turnovers, fewer is better.) Then, again in the fashion of a rotisserie basketball league, I’ve ranked the players from No. 1 to 15 in each category and added up the rankings to produce an overall score.

As a reminder, these stats reflect each player’s performance through the first 30 games of his rookie season only. On this basis, Wiggins ranks about average in points scored, steals, 3-pointers made, turnovers and fouls committed. He’s been somewhat below average in rebounds and blocks — two categories where his athleticism has not yet translated into good numbers. He’s also been a below-average shooter, and his assist rate — 1.6 assists per 36 minutes — has been poor.

By the fantasy basketball scoring method, Wiggins ranks 13th out of the 15 players. It’s tough to be a rookie in the NBA, but some of the rookies who came before Wiggins showed more early on. James ranks ahead of him in nine of 10 categories; Durant and Davis rank ahead of him in eight. Even Luol Deng, a player with whom Wiggins is sometimes compared, ranks ahead of him in eight of 10.

On the other hand, some rookies who weren’t much better than Wiggins in their first 30 games turned out to have nice NBA careers. Parker and Bosh, in particular, weren’t very productive early on. Overall, a player’s performance through his first 30 games does seem to tell us something — you’d rather take the players from the top half of the rotisserie-style rankings than those from the bottom. But it’s a fairly noisy list.

So Wiggins might have lost some value based on his performance so far this year, but he hasn’t crashed. (This conclusion is pretty similar to Neil’s.)

What about those advanced stats showing Wiggins to be awful (instead of just mediocre)? They’re probably not the thing for him to worry about right now. Most of those stats will punish players who shoot relatively often but relatively poorly, as Wiggins has so far. But the 5-25 Timberwolves don’t have a lot of better options, and Wiggins has shown some development this year, like shooting well from 3-point range. (And keep in mind that James shot just .417 through his first 30 games.) The bigger concerns are Wiggins’s low rates of rebounds, assists and blocks, deficits that show up in advanced and traditional statistics alike.

December 24, 2014

Week 17 NFL Elo Ratings And Playoff Odds: Special Seahawks Edition

The Seattle Seahawks began the season ranked No. 1 in FiveThirtyEight’s NFL Elo ratings. After flirting with the top position for the past two weeks, they reclaimed it on Sunday after crushing the Arizona Cardinals 35-6. The previous No. 1, the New England Patriots, also won on Sunday, but in much less impressive fashion, defeating the New York Jets 17-16. So Seattle’s Elo rating is now 1755, ahead of New England’s 1730.

These numbers may seem arbitrary. But we’ve back-tested the Elo ratings to 1970, when the NFL and AFL merged. Any rating above 1750 is very impressive. Since 1970, only 21 teams finished a season with a rating that high.

If the Seahawks win the Super Bowl again this year, they should be in the conversation about the greatest team ever — at least according to Elo. In the 32 percent of simulations we ran this week where Seattle won the Super Bowl, it finished with an average Elo rating of 1799. That would rank as the third-best end-of-season Elo rating since 1970, behind only the 2007 Patriots (who hold the top spot despite having been upset by the New York Giants in Super Bowl XLII) and the 2004 Patriots — and just ahead of the 1985 Chicago Bears and the 1989 San Francisco 49ers.

Yes, we’re getting ahead of ourselves (as we have before with Seattle). The 2014 Seahawks haven’t won anything yet. But it’s worth explaining why the system likes them so much.

Strong performance over a multi-year period. Elo ratings partially carry over from season to season, so a team can build momentum if it posts two or more good seasons in a row. This is part of why, for instance, the 1973 Miami Dolphins finished with a higher Elo rating than the undefeated 1972 Dolphins. (The 1973 edition of the team also had other things to recommend it, like having played a much tougher schedule.)

When Russell Wilson took over as Seattle’s quarterback at the start of the 2012 season, the Seahawks rated as a roughly league-average team with an Elo rating of 1491. (The average Elo rating is 1500.) Wilson went 4-4 in his first eight NFL starts. But since then, his trajectory — and the Seahawks’ — has been almost entirely upward. The Seahawks went 7-1 in the second half of 2012, then traveled to Washington to beat the Redskins in the wild-card round of the playoffs. Then, Seattle nearly defeated the Atlanta Falcons in the divisional round, coming back from a 27-7 deficit to pull ahead 28-27 before Atlanta kicker Matt Bryant notched the winning field goal with just 13 seconds to go.

Finishing strongly has been a hallmark of Wilson’s teams: Consider the Seahawks’ second-half run in 2012, their dominance in the playoffs in 2013, and what’s now been a five-game winning streak and counting in 2014.

A tough schedule with plenty of “clutch” wins against excellent opponents. All five of the Seahawks’ recent wins have come against tough opponents: two against Arizona, which Seattle has just overtaken for the top spot in the NFC West; another on the road in Philadelphia; and two others against San Francisco, the Seahawks’ longtime rivals. The Seahawks’ Elo rating has improved by 75 points during the winning streak.

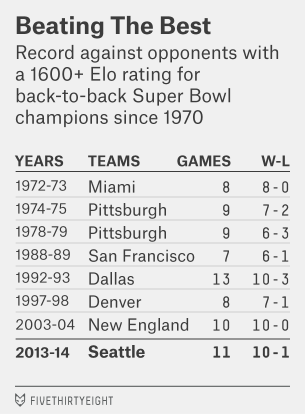

This has been typical of Wilson’s tenure in Seattle: The Seahawks have regularly risen to the occasion against tough opposition. Over the past two seasons, the Seahawks are 10-1 when facing opponents with an Elo rating of 1600 or higher.

Elo places a lot of emphasis on these “big” games; they’re the real test of a team’s strength. Even by the standards of the NFL’s all-time great teams, this is both a lot of big games to have played and a very impressive record in them. Compare the Seahawks against the seven teams to have won back-to-back Super Bowls since the NFL-AFL merger. Only the 1992-93 Dallas Cowboys played in more big games — 13 — and they lost three of them. And the Seahawks still have a chance to add to their list; they’ll probably need to defeat two or three more 1600+ Elo teams to win the Super Bowl again.

Consistency, even in defeat. While the Seahawks have won a lot of huge games, they’ve also occasionally been beaten by mediocre opposition. But they still rate as very consistent because these losses have come by narrow margins.

Wilson, in a career that spans 52 regular-season and playoff games, has never lost a game by double digits. And in each of the 13 losses he’s taken, the game has come down to the final quarter:

In nine of the Seahawks’ 13 losses under Wilson, Seattle led at some point in the fourth quarter.In three of the other four losses, Wilson had potential game-winning or game-tying drives in the fourth quarter.The only exception is Seattle’s 28-26 loss in St. Louis earlier this year. The Seahawks were mathematical favorites to win the game with 2:59 to play in the fourth quarter before the Rams’ Johnny Hekker converted a fake punt from his own 18-yard line.So Wilson has basically never been out of a game in 208 quarters of NFL football. Elo does not consider this degree of detail — it only looks at the final scorelines — but this is impressive. The Seahawks have been competitive in every game and outstanding in their biggest games for two or three years now. If they win another Super Bowl, their accomplishments will stack up pretty well against other back-to-back champions.

The rest of the NFL playoff hunt around the Seahawks has become anticlimactic. Ten teams, including Seattle, have now clinched the playoffs. The only remaining slots are for the champion of the NFC South — whichever of the 6-9 Atlanta Falcons and 6-8-1 Carolina Panthers wins on Sunday (after playing against each other) will advance from the division despite a losing record — and one remaining position in the AFC, which is being contested among the San Diego Chargers, the Baltimore Ravens, the Houston Texans and the Kansas City Chiefs. Here’s how Elo has the odds:

Although the Chargers have the most straightforward path to the playoffs — if they beat Kansas City, they’re in — Elo gives them a slightly lower chance of making the postseason (43 percent) than the Ravens (46 percent). That’s because the Chiefs are slight favorites in the game, which will be played in Kansas City. The Ravens, by contrast, are 81 percent favorites to win at home against the Cleveland Browns. Even needing San Diego to lose, Baltimore is a (slightly) better bet.

The Texans and Chiefs are long shots. Houston needs to win — which won’t be hard since its opponent is Jacksonville — but it will also need both San Diego and Baltimore to lose. There’s only a 9 percent chance of this happening. And while the Chiefs can take out the Chargers themselves, San Diego will need both Baltimore and Houston to lose. Since both Baltimore and Houston are heavy favorites in their games, that leaves Kansas City with just a 2 percent playoff probability.

Although all NFC teams but Atlanta and Carolina have either clinched or been eliminated from the playoffs, a few of them still have some business to take care of, including Seattle. The Seahawks could be demoted into a wild-card slot, essentially erasing the impact of their win over the Cardinals last week, if they lose to St. Louis and Arizona beats San Francisco to claim the NFC West title. Missing out on the division crown would deny Seattle a first-round bye and home-field advantage and cut its Super Bowl chances from 32 percent to 14 percent. It would also resurrect Arizona’s chances, which are down to just 3 percent after its loss last week; the Cardinals’ chances of a championship would rebound to 13 percent if they back into the division title. Unfortunately for the Cardinals, the combination of a Seahawks loss and an Arizona win has only about a 6 percent chance of happening.

Seattle will also clinch home-field advantage throughout the NFC playoffs if it wins — except under the bizarre scenario where the Green Bay Packers and Detroit Lions tie in Green Bay while Dallas beats Washington, which would give the Cowboys the No. 1 seed on the basis of their head-to-head win in Seattle earlier this season. But there’s only about a 1-in-700 chance of that happening.

Green Bay is about a 2-to-1 favorite against Detroit, according to Elo. But the system gives the Packers only a 7 percent chance to win the Super Bowl — much lower than offshore betting markets, which put their chances at about 13 percent. Elo has disagreed with bettors about the Packers all season, although less so as the year has worn on. In this case, the disagreement may have more to do with the Seahawks. The Packers will clinch a first-round bye with a win, but they’d still probably have to beat the Seahawks in Seattle to win the NFC Championship — a game in which the Seahawks would be roughly 75 percent favorites according to Elo but more like 65 percent favorites according to Vegas.

Elo point spreads

After a middling week for the Elo point spreads, we’ll issue the usual reminder that we don’t expect them to beat Vegas over the long term, even though they’ve fared pretty well so far this season. That’s especially the case in the final week or two of the NFL regular season, when teams may be resting their starters or otherwise have varying degrees of motivation to win their games — information that Vegas can account for but Elo does not.

December 18, 2014

Week 16 NFL Elo Ratings And Playoff Odds

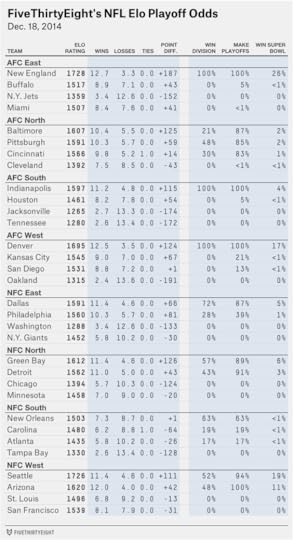

There are just two weeks remaining in the NFL regular season — and, as expected, we’re getting much more clarity about which teams are most likely to make a run to the Super Bowl.

Twelve teams will make the NFL playoffs. Four of them — New England, Denver, Indianapolis and Arizona — have clinched a position. Another seven — Seattle, Detroit, Green Bay, Dallas, Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati — have at least an 80 percent chance of reaching the postseason. It’s more likely than not that one of these teams will be knocked out, but the playoffs aren’t as wide-open as they appeared a few weeks ago. The 12th spot will go to the winner of the NFC South.

The real drama, however, will ensue once the playoffs begin. More than at earlier points in the season, there’s a clear top level of teams. It consists of the Patriots, Seahawks and Broncos.

You could debate the order of these teams. FiveThirtyEight’s Elo ratings have the Patriots first, the Seahawks second and the Broncos third. Football Outsiders’ DVOA also has New England first, but the Broncos ahead of the Seahawks. Jeff Sagarin, of USAToday, has the teams in the same order as DVOA. Vegas point spreads imply that Seattle is the best team, followed by New England and Denver.

But there’s reasonably clear separation between the top three and everyone else in the league. According to Elo, in fact, the gap between No. 3 Denver and No. 4 Arizona is wider than the gap between Arizona and No. 12 Philadelphia. Collectively, the Patriots, Seahawks and Broncos have a 62 percent chance of winning the Super Bowl.

None of these teams is exactly a surprise. In fact, each one ranked in the top four in our preseason Elo ratings, which were based on the teams’ Elo ratings at the end of last year.

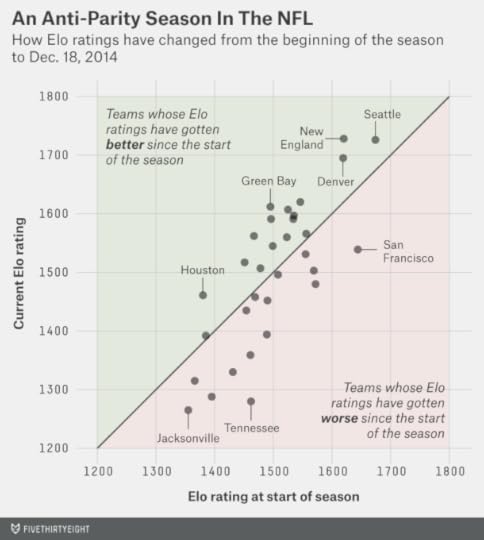

More generally, this has been a year where the richer teams got richer and the poorer ones got poorer. If you take the preseason ratings and divide the teams into halves, 11 of the 16 teams in the top half of the ratings have seen their Elo ratings improve since the start of the year. But 10 of the 16 teams in the bottom half have seen their ratings decline.

The Elo ratings generally haven’t behaved like this in past seasons. The way the system is designed, a team is about equally likely to see its rating improve or decline, whatever rating it starts with.

It’s probably premature to decipher any long-term trends from this season’s results. But perhaps there are some factors nudging the NFL away from the parity we’ve grown used to in recent seasons. Rules changes have allowed great quarterbacks to be more dominant. Access to information, technology and analytics may be enabling teams with great coaching, scouting and management to maintain more of an edge even as player personnel turns over.

As for the rest of the teams in the playoff hunt, we’ve reached the point where playoff outcomes are more deterministic and less probabilistic, with several opportunities for teams to clinch or eliminate themselves from playoff position with wins or losses this week. Mike Beouy and Reuben Fischer-Baum’s column on playoff implications has all the detail you’ll want on these, but here’s how Elo has the numbers:

There are some subtle differences between the playoff odds that Elo assigns and the ones that Beouy and Fischer-Baum do. This is partly because they use different measures of team strength and partly because the Beouy/Fischer-Baum system has a more complete handling of the NFL’s complex tiebreaker rules. But the overall message is largely the same; each system has the 11 teams I mentioned before with an 80 percent chance or greater of making the postseason.

However, it matters significantly how the teams are seeded. This is most acute in the case of the Arizona Cardinals. The Cardinals are currently one game ahead of the Seahawks in the NFC West, but Arizona lost to Seattle earlier this season, so Seattle would move ahead on the tiebreaker if they beat Arizona this weekend at University of Phoenix Stadium. Elo has Seattle as only narrow favorites in that game, but Vegas odds have the Seahawks favored by 8 points.

If Arizona wins, it will clinch home-field advantage throughout the playoffs. Arizona holds the tiebreaker advantage over the rest of the conference, partly by virtue of having beaten Dallas and Detroit earlier this season. Uniquely, this advantage would also extend to the Super Bowl, which is being held in Glendale, Arizona, this year. The Cardinals would become the first team ever to play a Super Bowl in its home stadium (although the San Francisco 49ers came close when Super Bowl XIX was held in Stanford, California.)

So even though they’ve clinched a playoff spot, this weekend’s game couldn’t be more important for Arizona. The Elo simulations give them a 37 percent chance of winning the Super Bowl if they win the NFC West, but just a 7 percent chance if they enter as a wild card team instead.

Elo point spreadsRecord against point spread: 113-93-3 on season (8-7 in Week 15)

Straight-up record: 156-67-1 on season (12-4 in Week 15)

The dominance of teams like New England, Seattle and Denver has made it easier for Elo to “call” winners correctly this year; the team favored by the system has won about 70 percent of the time this season.

Elo also has about a 55 percent winning percentage against closing Vegas point spreads. But as we’ve said every week, we still don’t think you should place bets using Elo, at least not without considering a lot of other information. Although we didn’t publish Elo ratings before this season, historically they would have picked only about 51 percent of games against the point spread.

A 55 percent winning percentage sounds impressive, but there’s still a lot of noise in the sample of 206 games. (This total excludes games that ended in pushes and cases where the Elo and Vegas lines exactly matched one another.) If a system’s long-run winning percentage was 51 percent, there’s still a 12 percent chance it would finish with a 55 percent winning percentage or better in a sample of that size, according to a binomial distribution.

Elo has mostly been right about the Cardinals, however — and it’s the Arizona-Seattle game that will tell us the most this weekend about who’s going to the Super Bowl.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 729 followers