Clifford Browder's Blog, page 48

February 2, 2014

111. The Slave Trade: How they got away with it, and how it was stopped.

In a previous post we saw how the illegal slave trade, furnishing African slaves to the Spanish colony of Cuba, was flourishing right up to the outbreak of the Civil War, with New York at the very center of it. The U.S. and Britain had both declared the trade illegal in 1807, and the U.S. had made it a capital offense by including it in the piracy law of 1820, though as of 1860 no slave trader had ever been executed. Now we shall see how the traders got away with it, and how that trade was finally stopped.

How they got away with it

The slave traders devised any number of practices and stratagems to avoid detection. As for instance:

· The ship owner chartered his vessel to someone else, who might even charter it to a third party. If the ship was caught carrying slaves, the real owner and the first charterer could plead ignorance: they had no idea the ship was being used for so nefarious a purpose.

· A ship might be a slaver one year, and engaged in legitimate trade the next, thus confusing the authorities. Or take a legal cargo to Havana, change its name and flag there, be refitted as a slaver under a Spanish skipper, and later on the way back, having delivered the slaves to Cuba, resume its legal status and name, change skippers again, and take on a cargo for New York.

· In New York the judges, customs officials, and U.S. marshals, being notoriously amenable to bribes, could be induced to look the other way, while a ship was preparing for a slave voyage.

· A ship would carry two sets of papers: one for the port authorities and any U.S. or British warship challenging it, presenting it as engaged in legitimate trade; and another for their confederates in Africa and Cuba. And lots of flags to fly, depending on what vessel they encountered.

· Nearing the African coast, the slaver would land an agent at the trading post and then stand out to sea, returning only when the slaves were assembled and an agreed-upon signal said it was safe to approach. Thus the loading of slaves could begin immediately and proceed quickly, and the ship could then weigh anchor and make for the safety of the open sea.

· Swift schooners and brigs were preferred for the trade, because they could usually outrun a patrolling warship, if they spotted the warship in time. If necessary, fleeing slavers would litter the sea with jettisoned casks, spars, hatches, whatever. The schooner Wanderer, built in 1857 by a wealthy New Yorker as a yacht for racing, had a long, sharp bow and a cutaway stern that let it do 20 knots and win cups in races. Sold to a Southerner, it then had a second career as a slaver and as such did very well, since warships could do only 8½.

· Often as not, the New York courts could be “fixed.” Even if caught and tried, a slave captain was rarely convicted, and if he was, the conviction might be overturned on technical grounds. Or he might be allowed to plead guilty to a lesser charge and serve a short sentence, and even hope for a pardon from on high.

The fast schooner Wanderer, which had three careers: a racing yacht, a slave ship, and finally,

The fast schooner Wanderer, which had three careers: a racing yacht, a slave ship, and finally,with the outbreak of the Civil War and its confiscation by federal authorities, a U.S. naval

vessel participating in the blockade of Southern ports.

Everything, then, seemed to favor the trade, and yet it did finally come to an end. In fact, it was stopped. What happened?

How it was finally stopped

In the November 1860 elections the Republicans triumphed and Abraham Lincoln became President. In New York this meant the end of Democratic control over federal appointments, and a new emphasis on stamping out the slave trade. Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith summoned all the U.S. marshals in states along the eastern seaboard to a meeting in New York on August 15, 1861, where measures were agreed upon to suppress the trade, following which the marshals visited captured slave brigs and schooners at the Atlantic Dock in Brooklyn. That hostilities with the South had broken out by then only heightened the resolve to end the trade.

Nathaniel Gordon

Nathaniel GordonAttention soon focused on the case of Nathaniel Gordon, a young skipper out of Portland, Maine, who in the summer of 1860 had taken his ship Erie to Havana, where it completed preparations for a slave voyage, not Gordon’s first but his fourth. Proceeding to Africa, it sailed up the Congo River to deliver a cargo of liquor, then returned to the river’s mouth and on August 7 took on a load of 897 slaves, stowed them on deck and below, and set sail for Havana. The following morning Gordon’s luck gave out; he was spotted by the U.S. sloop of war Mohican, which captured his vessel, landed the freed slaves in Liberia, and brought Gordon and the Erie to New York. The Erie was promptly condemned and sold, and Gordon was indicted under the 1820 piracy law. That he should be tried in New York, the very center of the Atlantic slave trade, no doubt seemed fitting.

The capture of the Erie, as reported in the

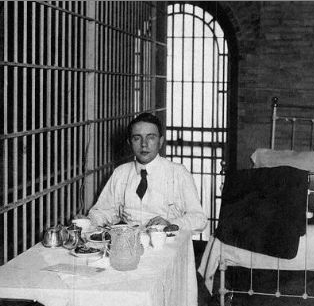

The capture of the Erie, as reported in theNew York Herald. Gordon was lodged in the Eldridge Street Jail, notorious for its lax conditions and the carousing of prisoners. He roamed freely there, received friends and family, wined and dined in comfort. For a $50 “fee” paid to the jailor, he was even allowed to go into town “on parole,” as long as he returned the next morning. If he seemed to harbor little fear for the outcome of his trial, there was ample precedent. Captain James Smith of the brig Julia Moulton had been tied for slavery in 1854. He was convicted, but the conviction was overturned on a technicality, and he was allowed to plead guilty to a lesser charge, got a short sentence and a fine, and was later pardoned by President Buchanan. This, then, seemed the very worst that Gordon could expect. And sure enough, when he was tried in June 1861 the jury could not agree.

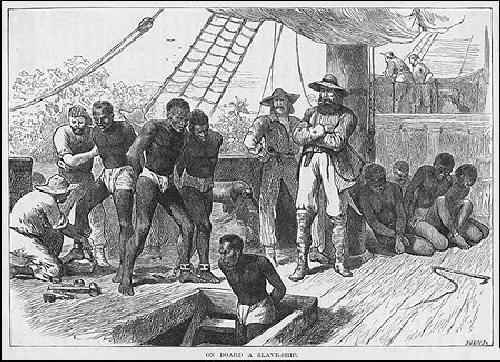

But the Lincoln administration was now in charge, and Edward Delafield Smith, the new district attorney, was determined to get a conviction. Gordon was put on trial again in the circuit court of New York on November 6, 1861, with two attorneys experienced in such cases defending him. The naval lieutenant who boarded the Erie and took command of it told how crowded the slaves were on deck, how fearful was the stench from the hold, and how offensive the filth and dirt on the slaves. In addition, several of the crew testified that Gordon was indeed in charge of the vessel. There was no denying that the defendant had been apprehended with a full load of slaves, but the defense argued that he was not in charge, having turned the command over to a foreigner. The case went to the jury on the afternoon of November 8, and they returned twenty minutes later with their verdict: guilty. Gordon heard it without showing emotion.

Up until this point the public, being preoccupied with fighting a war, had shown little interest in the case, but when the verdict was reported in the press, the public suddenly realized the full implications of the case. On November 30, when motions for a new trial had been denied, and the prisoner was instructed to rise and hear the sentence, the courtroom was packed. The presiding judge stressed the enormity of his crime, the agony and terror of his fellow beings confined below deck, and sentenced him to death by hanging on February 7, 1862: the first such sentence ever in the U.S. for the crime of trading slaves.

Gordon’s wife and little son had come from Portland to give him support, and their presence aroused much sympathy in the city, whose merchants had always been more concerned about retaining their trade with the South than with ending slavery. Petitions for clemency containing thousands of names were sent to Lincoln in the White House, condemning the crime but begging him to commute the sentence to life imprisonment. Claiming to be loyal supporters of the government, the petitioners expressed indignation at the death penalty imposed for an act involving Africa and Cuba, when it was lawful to take a Negro child born in Virginia to Louisiana and sell it there into perpetual slavery. Prison doors had been opened to convicted pirates and acknowledged traitors, while a gallows was being erected for Gordon. In addition, Gordon’s leading defense attorney and the prosecutor both went to Washington to plead in person with the President, who already had a reputation as a "softie" when it came to pardons, and Gordon’s wife obtained an interview with the First Lady.

Under pressure from all sides, Lincoln, who abhorred slavery and was determined to end it once and for all, only granted a two-week stay of execution, setting a new date of February 21, so Gordon could prepare himself. Realizing at last the certainty of his doom, Gordon, who had always protested his innocence, on the night before his execution attempted suicide by strychnine poison. Alarmed at the prisoner’s convulsions, the keepers called the prison physician, and Gordon was resuscitated by means of a stomach pump and brandy. How he had obtained the poison was unclear; presumably, it was in the cigars he had smoked the night before. Summoning a U.S. marshal, Gordon requested him to give a lock of his hair and a ring to his wife.

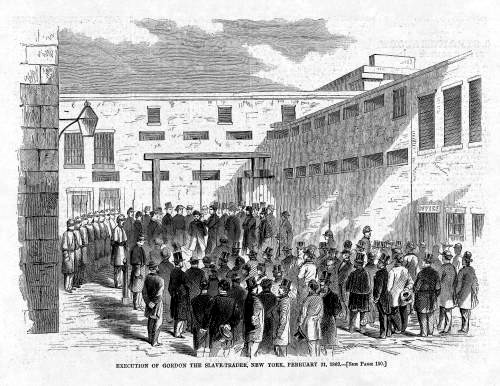

On the morning of the execution Gordon was given a heavy dose of whisky to overcome the effects of poison, his arms were tied behind him, and he was carried from his cell to a chair in the corridor, where the marshal read the death warrant to him. Upheld by the marshals present, at noon he walked across the courtyard of the Tombs, where eighty Marines were on hand, bayonets fixed, to quell a rumored attempt by a mob to interfere. Also present was a throng of invited spectators admitted by ticket – reporters, politicians, and officials – as well as uninvited witnesses watching from every window, balcony, and rooftop affording a view of the scene. Mounting the scaffold, Gordon announced, “Well, a man can die but once; I’m not afraid.” A black cap was then put over his head, the noose was put round his neck, an ax stroke severed a rope suspending a system of weights, and his body was hoisted into the air, where it swayed for a few moments and was still. For the first time ever, a slave trader had been executed in the United States.

In a letter addressed “To all my friends,” written on the eve of his execution, Nathaniel Gordon declared, “I have no trouble of conscience. I have never harmed a human being in my life.” He called the district attorney a murderer and insisted, “I meet a death that is undeserved.” Unrepentant to the end, he simply could not conceive of his African victims as humans deserving of compassion and respect.

Gordon’s young wife, who on the eve of his execution, sobbing, had fainted in his cell, returned to Portland, where he was buried. It is quite possible that his infant son never knew the fate of his father.

It is sometimes said that Gordon’s execution, taking place not in some distant federal facility but in a city prison in the heart of the city before a host of witnesses, ended U.S. participation in the slave trade, but this is not quite the case. After his death those involved in the trade left New York City for New London, New Bedford, and Portland, and for a short while, even in wartime, persisted in the trade. Perhaps they thought that the federal government, being embroiled in a war it showed no sign of winning, could not further enforce its laws against the trade; certainly its navy had more pressing tasks to perform. But Her Britannic Majesty was not so distracted; between March and October 1862 the British African Squadron captured no less than sixteen American slavers. A U.S. naval officer who then visited the Congo River – the very site of Gordon’s last trade – found the trading centers depressed and slave prices greatly reduced. The slave dealers on the west coast of Africa were soon in despair at the lack of vessels looking for slaves. The Cuba trade declined in 1863 and was eliminated by 1864. So ended a trade that had flourished for centuries and in its last years brought wealth to many a brownstone in New York City.

Doing what he loved best.

Doing what he loved best.Dan Tappan A note on Pete Seeger: Pete Seeger, folk singer and activist, died on January 27 in a hospital in Manhattan, at age 94. He was an inspiration to all who knew him or heard him sing. A champion of civil rights, labor unions, and the environment, he reached multitudes with his music and campaigned for what he thought right to the very end, marching with two canes in an Occupy Wall Street demonstration in 2011. His songs include "Good Night, Irene," "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?", "We Shall Overcome," and countless others. I shan't begin to celebrate him here, for I hope to include him and his campaign to clean up the Hudson in a future post on the sacredness of water. The Times gave him two full pages -- almost unheard of, but fitting. I can be stingy with my praise of public figures, but for Pete Seeger, both the singer and the activist, I pull out all the stops.

Coming soon: New York and the Vision Thing. Can a city as secular and materialistic as New York experience vision, and if so, what kind of vision? And can a materialistic vision have a spiritual component? In the works: The Sacredness of Water. Can it -- should it -- be privatized and sold as a commodity? Primal peoples the world over see it as a sacred; why don't we?

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on February 02, 2014 04:32

January 26, 2014

110. New York and the Slave Trade

By the mid-nineteenth century the port of New York was the busiest in the hemisphere, doing trade with all the major ports in the world. That New York City was also the center of the illegal slave trade in the 1850s may surprise many today, but such was the case. Respectable citizens were hardly aware of the trade, but those on the waterfront, even if uninvolved, could see signs of it. Any vessel bound for Africa was suspect. During eighteen months of the years 1859-60, eighty-five slavers were reported to have been fitted out in New York harbor, transporting from 30,000 to 60,000 slaves annually. This post will have a look at that trade, drawing mostly on primary sources.

Ships used in the slave trade: schooner (left), brig (center), and bark (right). Small, fast ships that

Ships used in the slave trade: schooner (left), brig (center), and bark (right). Small, fast ships that could outrun British cruisers were preferred.

BPL

In June of 1860 – on the very eve of the Civil War – a young New Englander named Edward Manning, being short of coin, went to a New York City shipping office and signed up for three years on the Thomas Watson, a whaler being fitted out in New London, Connecticut. Going to New London, he found a smart-looking vessel of 400 tons, remarkably clean for a whaler, many of whose crew were, like himself, “greenies.” A fine-looking woman came aboard and conferred with the captain in his cabin; she was said to be one of the owners. Had he not been a greenhorn, young Manning might have wondered why the ship was taking on so much rice, hard tack, beef, pork, casks of fresh water, and other supplies – far more than was needed for the crew of a whaler – as well as quantities of pine flooring that would be laid over the stores in the hold so as to create a new deck. He might also have wondered why the ship couldn’t get clearance and sail from New London, but instead went down to New York, accompanied all the way by a U.S. revenue cutter, all of which suggested that the ship was somehow suspect, might have a history. In New York the Thomas Watson anchored briefly off the Battery, then caught a favorable breeze and sailed from there, presumably bound for waters rich in whales.

As the vessel crossed the North Atlantic, it proved to be a smart sailer, hard to overtake. Nearing the presumed whaling grounds, the captain posted a lookout aloft to look out for “blows,” and even sent out boats in quest of whales, sustaining the image of a whaler all the way to the coast of Africa. Approaching that coast, it sighted a British man-of-war, at which point the “old man,” as the crew referred to the skipper, ordered the men to remove the pine flooring and store it aft. As the warship approached, it fired a shot across the whaler’s bow, raising a splash. “What ship is that?” came the query. “The Thomas Watson.” “I’ll board you!” So spoke the greatest navy in the world, displaying the arrogance typical of a world power. By now the greenies had long since grasped the fact – not particularly dismaying to most of them – that the Thomas Watson was no whaler but a slaver in disguise, hoping now to outwit the British Navy, which was intent on suppressing the slave trade, illegal in most parts of the world. A gig came alongside, and the English commander boarded the vessel, conferred with the captain in his cabin, and then inspected the deck and hold. Though he found no overt signs of a slaver, he was frankly skeptical and promised to have a look at the vessel again in the future. Once the departing visitors were out of earshot, the captain, an irascible man, exclaimed, “You English sucker! You’ll see me again, will you? I’ll show you!” In point of fact, they never encountered the warship again.

HMS Black Joke firing on the Spanish slaver El Almirante. The British ship freed 466 slaves.

HMS Black Joke firing on the Spanish slaver El Almirante. The British ship freed 466 slaves.If the greenies had any reservations about serving on a slaver, they had little choice, being far from home and near the coast of Africa. Enhancing their resignation may have been the realization that no trade on the seas was more lucrative than this one, which might mean more pay at the end of the run, if the British Navy -- and the American, though it was typically less in evidence – could be eluded. In 1860 the trade still flourished, taking slaves from West Africa to Cuba, then a Spanish colony, where the authorities looked the other way while the planters acquired more labor for their sugar plantations and paid well for it. Of the whole crew, only Manning voiced objections to serving on a slaver, for which he earned the captain’s undying enmity.

As the Thomas Watson neared the African shore, a small boat with naked black rowers approached, waving a bright red rag. A Spaniard came on board, embraced the captain, and kissed him. They conferred, then the Spaniard departed, leaving the crew mystified as to what this was all about. The Spaniard was allegedly a palm oil merchant, but the mystery remained.

For two weeks the Thomas Watson cruised about, not too far from the African coast, maintaining the feeble pretense of whaling. Then they approached an uninhabited stretch of shoreline, where only a long, low shed was visible – a barracoon (slave barracks) -- as he later learned. The captain, showing signs of nervousness, posted the mate aloft with a spyglass, ordering him to report any ship in sight. “Sail ho!” the mate finally cried out. “Where away?” asked the captain. “Right ahead, and close to the beach.”

They now made contact with a schooner, and the palm oil merchant reappeared, boarded the ship, and gave the captain another affectionate kiss. The pine flooring was now quickly laid, creating a deck to receive the oncoming cargo. Naked blacks – men, women, and children – now issued from the shed and walked in single file to the beach, where their black guards began tossing them into a surf boat that then negotiated the surf safely and transferred its human cargo to a small boat from the ship. The slaves were then taken to the ship and piled into the hold, the women separately in steerage. The ship was rolling all this while, so the slaves were seasick, and the foul air and great heat made the hold unbearable. Five or six were dead by morning, and their bodies were tossed overboard.

Model of a slave ship. The slaves are packed in on a deck laid over the stores in the hold,

Model of a slave ship. The slaves are packed in on a deck laid over the stores in the hold, which include ivory tusks. This vessel is armed, but most slavers relied on speed to escape

pursuing warships.

Kenneth Lu

Having secured its cargo, the Thomas Watson immediately weighed anchor and got under way, carrying some eight hundred blacks of all sizes and ages, with the Spanish captain and a crew of eighteen whites. The Spaniard, a veteran of the trade, was now in charge, whip in hand, and his ferocious manner kept the slaves in check. Guarded by overbearing guards of their own race, whom Manning identified as Kroomen (an African people living in Liberia and the Ivory Coast), the slaves were brought up on deck and fed rice and sea biscuits, but the stench below was suffocating, until means were found to let air in for ventilation. The Spaniard was a man of moods and contradictions. He delighted to let the little girls come up and play on deck, but when a man was caught stealing water, he had him flogged unmercifully. And yet, having some knowledge of medicine, he improvised a hospital on deck and treated those who were ill, probably saving the lives of several. Dysentery was the commonest ailment, but there were two fatal cases of smallpox, one of scurvy and one of palsy. Also, one woman gave birth to twins, but both infants died.

Slaves on deck, being shackled.

Slaves on deck, being shackled.The long transatlantic trip was not pleasant even for the whites on board. Scared out of the hold, the ship’s rats invaded the forecastle, where the crew slept. Manning tells how one night he felt sharp claws on his face, and a rat gnawing at his big toe, whose toenail was almost gone; after that he slept on the deck. When a crewman died of a fever in the dark, dingy hole of the forecastle, he was sewed up in canvas and laid out on a plank on deck; then, with no attempt at a service, the plank was raised at one end, and the body slid into the sea. Meanwhile the American captain was getting drunk daily on rum and then 1retiring to a spare boat on the poop deck to sleep it off. The Spanish captain remonstrated with him, protesting that he was setting a bad example for the crew, but to no avail.

The condition of the slaves was now of some consequence, as the vessel was approaching Cuba. They were brought up on deck in batches, and bathed in the spray from a hose. To fumigate the hold, the crew stuck red-hot irons into tin pots filled with tar, sealed the hold with hatches, and waited two hours; by then the hold was considered cleansed.

Having been at sea for six months, the crew were now eager to make land. The likable second mate expressed the hope that he would make enough money on this voyage to buy a little place ashore and settle down; for him, it was just a job. They now scraped the ship’s name off the stern, thus making them all outlaws, and the vessel fair game for anyone. Special precautions had to be taken, for British men-of-war patrolled the Cuban coast as well, and the appearance there of a whaler would arouse suspicion, especially if large numbers of blacks were seen on deck. In time they rendezvoused successfully with two schooners, one of which came alongside; brought up to the deck, the blacks were made to jump down to the schooner’s deck, the Kroomen going last. The Spanish captain too left the ship, and the second schooner took on half the blacks from the first one, after which the two schooners made for land. Their cargo delivered, the crew of the Thomas Watson then removed the telltale pine flooring and threw it overboard.

The ship now sailed to Campeche, Yucatan. Chloride of lime was sprinkled in the hold to eliminate the smell of slaves in confinement, but some hint of the odor remained. The crew were now paid, and paid well, in Spanish doubloons, and Edward Manning took passage on a Mexican schooner to New Orleans, where he arrived in January 1861. There, finding Secession in the air and the people feverish, the New Englander got out fast, returning to New York by rail. When war broke out, he joined the U.S. Navy and served for the duration. The Thomas Watson became a Confederate blockade runner but while pursued by Northern warships ran aground on a reef off Charleston, South Carolina, and was burned by the Northern ships to the water’s edge.

Such was the account of Edward Manning, which he published with the title Six Months on a Slaver in 1879. Though opposed to slavery, he tells his story in a sober, matter-of-fact way, expressing sympathy for the slaves, but never inveighing against the evils of slavery. In short, he lets the story tell itself. The book is a rare example of a firsthand account of the trade, since those involved usually shunned publicity. The voyage was routine, with no drama: no pursuit by British cruisers, no slave revolt, no storm, no high death rate among the slaves. The vessel’s prompt departure from the port of New York, which Manning doesn’t explain, was probably facilitated by prior negotiations with the authorities there and smoothed with a bribe. Manning doesn’t identify the coast where the slaves were taken on, but it was certainly that part of West Africa where the Atlantic trade flourished: the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), and the Slave Coast, this last being the coastal area of modern-day Togo, Benin, and western Nigeria.

The first meeting with the palm oil merchant, later identified as the Spanish captain, was to arrange a rendezvous for loading the slaves; this was to make sure that the loading would go quickly, so the vessel could get away fast from the coast without being caught by a British warship. The Spaniard was evidently a loose packer, meaning that he allowed the slaves ample room and thus kept mortalities to a minimum; tight packers usually had corpses to dispose of, and the corpses, once in the sea, drew sharks that might follow the ship for days: the sure sign of a slaver to the captain of a British cruiser. But in the vast expanse of the North Atlantic, there was little risk of detection, until the slaver approached the Cuban coast. The Kroomen guards were probably not destined for slavery, but further employment by the Spaniard on future voyages, it being a sad fact that blacks too participated in the trade and facilitated it.

“The Slave Trade in New York,” a January 1862 article in The Continental Monthly,a new periodical of the time published in New York and Boston, gives useful background for Manning’s story. Since by then reform was under way, the conditions described are those prevailing before the 1860 election: exactly the time when Manning was recruited for the Thomas Watson. According to the article, New York City was the world’s leading port for the slave trade, with Portland and Boston next. (The author might have added New Orleans.) Slave dealers, some of them seemingly respectable Knickerbockers, contributed liberally to political organizations and thus influenced elections not only in New York but also in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. The captains involved in the trade lived in residences and boardinghouses in the eastern wards of the city and formed a secret fraternity with signs, grips, and passwords. A slave captain planning a voyage would initiate preparations in a first-class hotel like the Astor House, where the risk of detection was less than in a private office. Runners, provided with the names of men of every nationality who had served on slavers before, would be sent to boardinghouses to recruit a crew; their appraisal of prospective crewmen was reliable, their blunders few. Rather than equipment for a whaling voyage, as in the case of the Thomas Watson, apparatus for refining pine oil, a common and legitimate import from Africa, was often used as a blind, for a U.S. marshal would inspect in port any vessel suspected of being a slaver. One yacht owner was quoted as saying that he had paid $10,000 to get clearance. But getting clearance at the custom house was easy, a transparent disguise being enough. And should a slaver be captured by a British warship, the New York owners were rarely troubled, having a corps of attorneys on retainer to defend them.

As an example of the laxity of the law, the article tells the story of the brig Cora, a slaver captured at sea and brought to New York. Her skipper, Captain Latham, was lodged in the Eldridge Street Jail, where inmates caroused freely with liquor and champagne. Securing funds from a Wall Street connection, Latham bribed one of the U.S. marshal’s assistants with $3,000 and so was allowed to leave the premises, buy a suit at Brooks Brothers, and proceed to the dock just in time to catch a steamer to Havana. Since then Latham was said to have returned to the city in disguise.

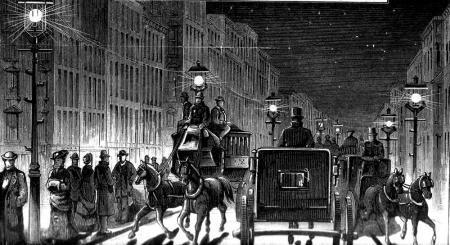

The jail where a slaver awaiting trial could live comfortably, even riotously. Bars are visible

The jail where a slaver awaiting trial could live comfortably, even riotously. Bars are visible on one window, though they didn't prevent an inmate with money from leaving on excursions.

Not all slave voyages were as routine and uneventful as that of the Thomas Watson. Edward Manning never got ashore to see a caravan of slaves arrive from the interior. One such caravan of twelve hundred naked slaves, captured and guarded by other blacks, has been described as arriving at the coast to the sound of rifle fire, tom-toms, and drums. The trading that ensued might involve an exchange of slaves, ivory, gold dust, rice, cattle, skins, beeswax, wood, and honey for cotton cloth, gunpowder, rum, tobacco, cheap muskets, and assorted trinkets. A strong, healthy male of twenty might fetch three Spanish dollars; women and boys went for less.

A slave caravan.

A slave caravan.As a slaver weighed anchor laden with “black ivory,” heart-rending scenes might occur. On one occasion blacks in two canoes and on a raft came alongside a departing brig, begging to be taken also, so they could rejoin relatives now chained under the hatches. Seeing that they were old, the captain took only three. The others persisted, till a six-pound shot destroyed the raft. Some of the crew were troubled by this, but the captain remarked coolly, “Your uncle knows his business.”

And what became of the elderly and sick slaves that no trader wanted? On one occasion eight hundred of them were taken out in canoes by other blacks and sunk with stones about their necks. Here again, the cruelty of blacks on blacks matched that of whites on blacks. The slave trade corrupted all who were involved in it.

The worst that could happen at sea was not so much a slave revolt but a fire. One repentant skipper told of such a horror at night, when all their cargo was locked under hatches. The crew tried to put out the fire below with buckets of water, but the flames spread amidships and the vessel was doomed. “Bear away, lads!” ordered the skipper. “Lashings and spars for a raft, my hearties!” The crew improvised a raft from the masts and bowsprit, and hoisted out the two boats, while the fire smoldered between decks and the slaves screamed. As the crew abandoned ship, a merciful mate lifted the hatch gratings and flung down the shackle keys, so the slaves could escape from the hold. As the ship’s two boats towed the raft clear of the burning vessel, the slaves gained the deck, only to become enveloped in flames. Some jumped into the sea and tried to climb aboard the boats and raft; a few succeeded, but the crewmen, fearing that they would be swamped, fought most of them off with handspikes. As the white survivors distanced themselves from the vessel and the drowning slaves, the sea was illumined for miles by the flaming brig. Out of 640 slaves, 115 were saved on the raft. Saved, of course, for slavery. For the traders, not a very satisfactory voyage.

Did those who participated in the trade ever repent of it? Yes, but usually on their deathbed. Said one: “There is no way to stop the slave trade but by breaking up slaveholding. Whilst there is a market, there will always be traders. Men like me do its roughest work, but we are no worse than the Christian merchants whose money finds ships and freight, or the Christian planters who keep up the demand for negroes. May God forgive me for my crimes, and may my story serve some good purpose in the world I am leaving.”

And as Edward Manning’s account makes clear, slave trading was an equal opportunity operation. Even in those Victorian times, when ladies were confined to the parlor, with forays into the nursery and outings for good works, some seemingly respectable women were up to their ears in the trade. The woman Manning observed was a New London resident, but there were more such women in New York. They kept a low profile, but occasionally their name crept into print. A Law Intelligence report in the New York Tribune of September 22, 1862, told how a Mrs. Mary Jane Watson of 38 St. Mark’s Place had operated as a blind for John A. Machado, who skippered the bark Mary Francis on a run from Africa to Cuba. Machado was arrested in New York, but to my knowledge no woman was ever prosecuted for participation in the trade.

Why did good Christian men and women – ship owners, ship fitters, insurers, and provisioners, aided by banks extending loans to planters, and by iron merchants providing shackles and manacles – choose to get involved in this shameful web of complicity? Two reasons: money and immunity. A healthy young slave costing $50 in Africa could easily bring $350 or even $500 in Havana, and a healthy but inferior slave at least $250. And the chances of getting caught and prosecuted were minimal. For some, the temptation was simply too great, especially when you could remain at a safe remove and leave the dirty work to others.

In the next post we will see the many subterfuges these investors used to escape detection, and how this vile business, widespread but centered in New York, finally, and appropriately in New York, came to an end.

Bank note: Virtue is rewarded after all in this cold, callous world, and there is still such a thing as loyalty. Jamie Dimon, the embattled CEO of my beloved bank, J.P. Morgan Chase, has been given $20 million in compensation for 2013, a year in which the bank paid $13 billion (yes, billion, not million) in a settlement with the Justice Department over some mortgage securities, and endured other undeserved woes. That's a 74% raise over 2012, which shows the board's loyalty to Mr. Dimon and its confidence in his managerial skills. And, incidentally, there is still plenty of free candy available at my branch.

Coming soon: The Slave Trade: How they got away with it, and how it was finally stopped. And then: New York and the Vision Thing. Can a greed-ridden commercial town even have a vision? We'll see.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on January 26, 2014 04:54

January 19, 2014

109. Two Forgotten New York Murders

New York City has seen its share of murders over the years; this post will describe two of them that have some aspect that makes them of interest.

Helen Jewett, 1836

Called the Girl in Green because of the clothes she wore, in the 1830s Helen Jewett was the city’s most famous prostitute. Born in Maine to a working-class family, at the age of about twelve she went to work as a servant girl in the home of a judge, but at the age of eighteen, perhaps because of a seduction, she left there and moved to Portland, where she became a prostitute under an assumed name. After that, still using fake names, she moved to Boston and finally to that magnet of hustlers and achievers, New York. There she flourished in a fashionable brothel at 41 Thomas Street, where her beauty attracted numerous clients, including lawyers, merchants, and politicians.

Called the Girl in Green because of the clothes she wore, in the 1830s Helen Jewett was the city’s most famous prostitute. Born in Maine to a working-class family, at the age of about twelve she went to work as a servant girl in the home of a judge, but at the age of eighteen, perhaps because of a seduction, she left there and moved to Portland, where she became a prostitute under an assumed name. After that, still using fake names, she moved to Boston and finally to that magnet of hustlers and achievers, New York. There she flourished in a fashionable brothel at 41 Thomas Street, where her beauty attracted numerous clients, including lawyers, merchants, and politicians.About 1:00 a.m. on Sunday, April 10, 1836, one of the girls in the house heard a loud noise from Helen’s room, then a moan, and saw a tall figure hurrying away down the hall. Two hours later Rosina Townsend, the madam, noticed that the door to Helen’s room was partly open. Entering, she encountered billowing black smoke from a fire near the bed. Immediately she roused the other girls, opened a window, and cried “Fire!” Several night watchmen came quickly to put out the fire, though not before several male clients had managed to slip out, some of them half clothed at best. Only then, as the smoke cleared, did they find Helen Jewett’s body in the bed, her nightclothes burned, her body on one side charred, and her bloodied head caved in from wounds by an ax.

The murderer had fled through a back door, left his cloak and a bloodied ax outside, and climbed over a whitewashed fence to escape. Based on the testimony of the other inmates of the house, the police went to the home of 19-year-old Richard Robinson, a clerk in a dry goods store, and arrested him on suspicion of murder. From a respectable family in Connecticut, Robinson was a “fast” young man and one of Helen’s regular customers; he had visited her that night. He protested his innocence, insisting that he had been asleep in his bed at the time of the murder, but on his pants were stains of whitewash. When shown the still-warm corpse, he displayed no trace of emotion. A hastily assembled coroner’s jury heard the testimony of various witnesses and concluded that he had killed her with a hatchet and should be held for trial.

How the press imagined the scene of the murder. The real scene was bloodier.

How the press imagined the scene of the murder. The real scene was bloodier.Helen Jewett’s murder became big news in the press. Up till then American newspapers were devoted mostly to the dry statistics of business and the speeches of politicians. Doing historical research, I have consulted them and found only masses of fine print devoid of bold headlines, interviews, gossip, cartoons, charts, maps, or other illustrations – nothing, in fact, to entice the eye or entertain the mind. James Gordon Bennett, founder and editor of the New York Herald, was determined to change this and attract a wider readership.

When news of Helen Jewett’s murder first broke, Bennett assumed that Robinson was guilty and managed to be admitted to Helen’s room, where he viewed the body -- “the most remarkable sight I ever beheld” – whose sensual contours, now stiffened by rigor mortis, he described at length in his paper, likening them to sculpted marble. Bennett then surmised that Robinson had been in love with Helen; jealous of her association with other men, he had decided to break with her, went to her room to extract from her some letters of his and other items that she refused to give up, whereupon he produced a hatchet from beneath his cloak and murdered her, set a fire to cover traces of the crime, and fled. When Bennett printed all this in lurid detail, the public gobbled it up, the Herald’s circulation soared, its overworked presses broke down several times, and the newspaper had to move to larger quarters. So began the reign of yellow journalism in this country, a reign that continues to this day.

Bennett interviewed Rosina Townsend as well and began to suspect the madam herself and the other girls in the house, while reversing his opinion of Robinson’s guilt. He was soon entangled in a spirited controversy with the Sun and other papers convinced of the young man’s guilt. (The Times and Tribune were not involved, as they had yet to be launched.) Meanwhile business fell off sharply at the brothel, the girls started leaving, and Mrs. Townsend was forced to sell some of her furnishings, including the murder bed, which, once sold, was smashed into pieces that were carried off by many as souvenirs. Before the trial began, young men were rallying to support Robinson, viewing prostitutes as social leeches who, while necessary to satisfy male needs, were themselves of little worth. But some women came forth in sympathy with the victim; while not defending her life style, they insisted that her killer should be held to account. The case now was front page news in other cities, and the citizens of New York could talk of nothing else.

The trial began on June 2, 1836, less than two months after the murder. (Things moved faster in those days.) The courtroom was packed, and – unusual for the time -- representatives of out-of-town newspapers were present. Defending Robinson was no less a legal luminary than Ogden Hoffman, the son of a New York State attorney general and himself a former district attorney. Many witnesses testified, including Rosina Townsend and a number of prostitutes. Powerful circumstantial evidence was skillfully countered by Hoffman: yes, Robinson was known to have a cloak similar to the one found outside the brothel, but so did many other citizens; etc. When the judge gave the jury its instructions, he ordered them to ignore the testimony of prostitutes, thus demolishing much of the prosecution's case. In less than half an hour the jury returned with its verdict: not guilty. Robinson wept, his supporters cheered, and Helen Jewett’s supporters were stunned. The Herald was satisfied; the Sun insisted that Robinson had used the money and influence of wealthy relatives and his employer to buy an acquittal.

After the trial some pages from Robinson’s diary were made public, showing him to be callous in his treatment of women. Public opinion, including even some of his supporters, turned against him, being convinced now of his guilt. In time he decided to transfer his talents to the Republic of Texas, where he is said to have become a respected citizen of the frontier. Whether this meant fighting Comanches and Mexicans or just behaving himself, isn’t clear, though he seems to have opened a dry-goods store and other businesses.

No one else was ever tried for the murder of Helen Jewett, who continued to be viewed as either a victim of society or a scheming seductress who, like all of her profession, took advantage of male vulnerability and its proneness to sexual error. Nor was Helen’s memory left in peace. Rumors circulated that resurrectionists exhumed her, stripped her bones, and used her skeleton as a medical exhibit. What happened for certain was that her wax likeness became part of an East Coast traveling show warning young men and women of the fatal consequences of depraved behavior.

What is one to make of all this today? First, the hypocrisy of the double standard: a man who frequents prostitutes is simply yielding to base instincts aroused by female wiles; the prostitutes are far more guilty than he. This attitude was even pushed so far by some as to declare, “No man should hang for the murder of a whore.”

Second, the newfound role of sensationalist journalism in publicizing crime, sex, and scandal, even to the point of tainting the proceedings of justice, since potential jurors could not but be aware of the conflicting opinions about a case that would soon be tried. It’s worth noting, too, that the burgeoning yellow press of the day – Bennett’s Herald and other publications that followed his lead – addressed a primarily male audience, since no respectable lady should read such stuff. What, then, were respectable nineteenth-century ladies supposed to read? Godey’s Ladies Book, with its tinted plates showing current female fashions, and The Ladies’ Repository, a Methodist-sponsored monthly whose articles, poetry, fiction, and expositions of sound Methodist doctrine could be safely read by the gentler sex. Foxy Lady lay a long time in the future.

Today, opinion inclines strongly to a belief in Robinson’s guilt. Which makes me wonder why some of us, when provoked, commit crimes of violence, while most of us do not. Criminologists will have the final say on the matter, but I’ll toss my modest two cents in, for whatever it is worth. My inmate pen pal in North Carolina – who will soon be released, by the way – once wrote a vignette of prison life entitled “Murderers I Have Known.” In it he explains that one never asks another prisoner what he is in for, since to do so is to court trouble. But some inmates, upon getting to know you, will volunteer their stories, and he relates several. The common denominator, I concluded, was an inability to control anger, and a tendency to yield to impulse without considering the consequences.

The most striking account told how a young man, when he failed to get the promised Christmas gift of a motorcycle from his parents, was so angry that he got a gun and killed them both. Then, panicking, he rushed to the garage to escape -- to where he didn’t know -- in the family car. And there in the garage he discovered a shiny new motorcycle that his parents intended as a surprise. Try as I may, I can’t understand the young man’s deed. I can imagine him raging and ranting against his parents, threatening to run away or doing it, or breaking some object cherished by them. But I can’t conceive of getting a gun and murdering them. Are some of us wired differently so that, if provocation arises, we do unlooked-for acts of violence? I’ll let criminologists explain the matter. But the very thought of it is scary.

Finally, I can’t help but wonder who Helen Jewett was. She was portrayed by contemporaries either as an unfortunate young woman seduced and led astray, or as a wanton seductress taking advantage of her male clientele, but both these views are stereotypes. Who was she really? There are those today who see her as a bold sexual adventurer and independent woman – a feminist before her time – but this strikes me as a projection of current attitudes unsupported by the facts of the case. Who she really was we don’t know and never will.

The Helen Jewett murder has taken up so much space, and led in so many directions, that I’ll add only one more murder here. So now we’ll zip forward into the early twentieth century, when the vigorous muscular frame of Teddy Roosevelt, the hero of San Juan Hill, bustled its weight in the White House, and America, the victor in the Spanish American War, was becoming a recognized world power. But we’ll linger far from the centers of national power, settling down for a moment in Chinatown, New York, where different powers held forth and a different war was raging.

Ah Hoon, 1909

Ah Hoon was a Chinese American comedian performing in the Chinese Theater on Doyers Street, where Chinese spectators mixed with English-speaking visitors whose interest in exotic Chinatown was not diminished by the occasional whiz of a bullet or the aroma of gunpowder often in the air. The bullets and gunpowder were the result of a tong war between the dominant On Leongs on the one hand, and the rival Hip Sings, led by a young upstart named Mock Duck, and their ally, the Four Brothers association; at stake was control of the illegal but very lucrative gambling and drug activities in Chinatown. (The tongs of the time were mutual aid societies that had evolved into murderous gangs.) Mock Duck was a formidable figure, strutting around Pell Street covered with diamonds, his sinister image enhanced by long, lethal fingernails indicating that he left the dirty work to his lowly associates. Knowing his life in danger, he wore a chain-mail vest and, if attacked, was said to squat down in the street, shut both eyes, and fire two handguns at his assailants. Rough on passers-by, but it must have worked since he survived.

Mock Duck, with neither vest nor diamonds

Mock Duck, with neither vest nor diamondsnor weapons visible.

This sinister figure was not one to trifle with, but Ah Hoon did just that. Being associated with the On Leongs, during his performances in April 1909 he began making fun of Mock Duck and the Hip Sings and Four Brothers, and in the months that followed, his gibes got fiercer. Mock Duck and the Hip Sings were not amused; in fact, their appreciation of Ah Hoon’s humor was in such scant supply that they finally sent an emissary to the comedian to inform him he would die on December 30, 1909.

This notice must have caused Ah Hoon some anxiety, but the On Leongs rallied to his support. On December 29 a police sergeant and two patrolmen were assigned to guard Ah Hoon during his performance in a sold-out theater jammed with spectators eager to see a public execution. After the performance the three policemen escorted Ah Hoon through a tunnel back to his Chatham Square boardinghouse. There the comedian went upstairs and retired to his room, whose only window faced the wall of the building next door, while a squad of heavily armed On Leongs stood guard outside his locked door, and dozens more kept watch in the street below. Feeling safe, Ah Hoon went to bed. The next morning he was found dead with a bullet in his heart.

In celebration of their victory, the Hip Sings paraded through the streets of Chinatown with the requisite fireworks, music, and dancing dragons. The police were baffled; how had the Hip Sings managed it? In time, another police investigation figured it out. The Hip Sings had entered a nearby tenement and mounted to the roof, then jumped across three roofs to the roof of the building next door to Ah Hoon’s, and before midnight lowered a hit man in a chair by rope; the hit man had then stealthily entered the room through the window, approached the bed, and shot the sleeping comedian with a silencer-equipped gun, after which he regained the chair and was hoisted back up to the roof. Ah Hoon probably never knew what happened, nor was a suspect ever arrested. Meanwhile the tong war continued.

Mock Duck, who must have ordered the murder, won the war against the On Leongs, but was arrested several times in the following years; finally convicted for operating a policy game (an illegal lottery), he served two years in Sing Sing. In 1932 he helped arrange peace among the Chinatown tongs and retired to Brooklyn, where he died in 1941.

Ah Hoon’s murder does not prompt me to the many reflections that Helen Jewett’s does, for it was simply a gangland murder, Chinatown style. Who was Ah Hoon? Did he have a family? Why did he risk his life by making fun of a rival tong? It was like a comedian in Chicago in the 1920s making fun of Al Capone. The sources say nothing of all this; they simply record the basic facts of an ingenious murder.

Me and Teddy Roosevelt: Ah Hoon's murder, like that of Stanford White (post #107), occurred when Teddy Roosevelt was President, which prompts a personal reflection. Teddy Roosevelt is the only President from before my time whom I have related to personally. Back in my tender years my father, a great sportsman and lover of the outdoors, often told his younger son, a bookworm with no aptitude for sports, how Teddy Roosevelt had been a puny little pantywaist, easily bullied by other boys, until he went out West, toughened up, and became a muscular, two-fisted specimen whom no bully would mess with: he became a man. As a result, all through my grade school and junior high school years I nourished an intense desire to mount a picture of T.R. on my bedroom wall, so I could use it as a dartboard and implant a barrage of sharp objects in his beefy, toothy grin. Intensifying this urge was the fact that T.R.’s favorite exclamation was “Bully!” – which can be interpreted variously.

Alas, I never obtained the picture or the dartboard, and in time myself and my views ripened. Today I have to acknowledge the following:

· T.R., albeit a racist and imperialist, was also that rarity of today, a progressive Republican.· He established the National Park system.· He busted trusts. (Ah Teddy, in this era of too-big-to-fail banks, where are you when we need you?)· I myself have been known to say, ”Bully!” Albeit a bit facetiously.· I once took an obligatory boxing class in college and survived. Once, I even merited praise from the instructor, a professional boxer with an impressive build. But I saw boxing as a game, almost a dance, nothing more.· Still, I am not a hunter, and think it both ridiculous and repellent that those who are have traditionally mounted on their walls the heads of creatures they have slain. I have often fantasized seeing the head of the hunter himself mounted there beside them: a delicious thought.

Big man kills big elephant: big deal.

Big man kills big elephant: big deal.Me and hunting: To talk about Teddy Roosevelt is to talk about hunting. Yes, in this regard I've just tried to have a laugh at his expense, but as a child of the Midwest and son of a hunter I know that it's not that simple. As my father explained to me long ago, hunting is an instinct, stronger in some than in others. In him it was strong; in me, practically nonexistent. I came in time to inherit his love of the outdoors, but had no interest in his fishing poles and shotguns, his most cherished possessions. But urban liberals usually fail to grasp how important hunting is to many people in other parts of the country, how it's in their blood. My own feelings are mixed. Hunting to obtain a truly necessary supply of food I have no quarrel with, nor hunting to thin out an overabundance of wildlife, since that will actually benefit the wildlife. As for hunting as a sport -- the kind of hunting most Americans do -- I have no personal interest in it, but wouldn't want to interfere with those who do. It needs to be regulated, obviously, for the sake of all concerned. If, as Tennessee Williams's character in The Glass Menagerie insists, man was meant to be a lover, a warrior, and a hunter, maybe being a hunter is the easiest to achieve. The trouble is, too often there are far more hunters than game; the hunting instinct persists, but the wilderness that accommodates it is much diminished. Do I believe in gun control? You bet! But in control of handguns and automatic weapons, which have nothing to do with hunting. Leave it to the NRA to try to muddle the issue, so as to enlist hunters against even moderate gun control -- a fight that continues, and that so far the NRA is winning.

My father loved them, I did not.

My father loved them, I did not.Gurpreetsihota

Coming soon: New York and the Slave Trade. And a sequel: The Slave Trade: How Did They Get Away with It, and How Did It End? Also: New York and the China Trade. (Titles tentative.)

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on January 19, 2014 04:58

January 12, 2014

108. Andy Warhol: Genius or Fraud?

In an auction last November 13 at Sotheby’s here in New York, a grisly Andy Warhol painting, “Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster),” showing a body amid the wreckage of a car crash, was sold for $104.5 million, the highest price paid to date for one of the artist’s works. The sale provoked much comment, some of it harshly negative, and rekindled the perennial debate as to the importance of Warhol as an artist, some seeing him as a genius and some as a fraud.

Recently I queried several friends, all knowledgeable New Yorkers, and got a consistently mixed reaction. “So-so,” said one, adding that he could do without the repetitions, meaning the reduplications of celebrity portraits and other subjects. My friend John felt that certain works, but not all, merited serious attention, citing in particular a silkscreen painting – just one, not fifty – of Marilyn Monroe, that the artist painted in 1962, soon after her suicide, and then reproduced many times; John found her expression and the vivid background coloring captivating.

A third friend, an artist who does landscapes and city views, saw early Warhol as defining a moment in art history but viewed the later work, always witty and entertaining, as lacking the depth of the earlier work. When I questioned him about the “moment in art history,” he said that early Warhol in a small way recognized and visualized a decade in which American decadence had a defining influence on the course of civilization; by “decadence” he meant a materialistic view of the world, with instant gratification and idol worship (Marilyn, Elvis, Liz Taylor) thrown in. My partner Bob, who loves abstract expressionism, is frankly scornful of Warhol, whose work he deems simplistic, commercial, and lacking in depth; “I’ve never seen a work of his that I liked,” he explains. As for me, less knowledgeable about modern American art than any of them, I am inclined to share Bob’s reaction, opining that Warhol was indeed a genius … of self-promotion. But maybe I’ll be moved to – just a little – change my mind.

Andy with a friend.

Andy with a friend.Jack Mitchell

No one would deny that Warhol, the Prince of Pop, probably alone of twentieth-century American artists, made his name a household word for his generation and beyond; people who know little or nothing about art have heard of him and sometimes have opinions. He surfaced in New York in the 1950s as a successful and very well paid commercial artist and an innovator in silkscreen painting. In the 1960s his Pop art was widely displayed in exhibitions featuring such attention-getting creations as Campbell’s Soup Cans, 100 Coke Bottles, and 100 Dollar Bills, plus renderings of vacuum cleaners and hamburgers, and garish portraits of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Marlon Brando, and Mohammad Ali. He himself became a celebrity, his youthful features, with long blond hair and glasses, becoming known to the public through photos and self-portraits.

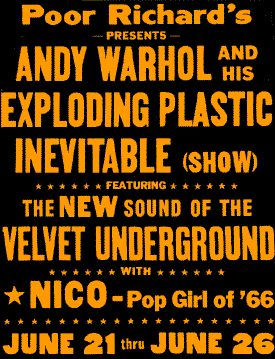

No one would deny that Warhol, the Prince of Pop, probably alone of twentieth-century American artists, made his name a household word for his generation and beyond; people who know little or nothing about art have heard of him and sometimes have opinions. He surfaced in New York in the 1950s as a successful and very well paid commercial artist and an innovator in silkscreen painting. In the 1960s his Pop art was widely displayed in exhibitions featuring such attention-getting creations as Campbell’s Soup Cans, 100 Coke Bottles, and 100 Dollar Bills, plus renderings of vacuum cleaners and hamburgers, and garish portraits of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Marlon Brando, and Mohammad Ali. He himself became a celebrity, his youthful features, with long blond hair and glasses, becoming known to the public through photos and self-portraits.  Poster for Exploding Plastic

Poster for Exploding PlasticInevitable, a 1966 multimedia

spectacle by Warhol that featured

The Velvet Undergound. Warhol’s studio at 231 East 47thStreet, dubbed the Factory (it was in fact an abandoned hat factory), proved a magnet for avant-garde artists, writers, musicians, and assorted drug addicts, weirdos, and crazies, all of them Warhol devotees over whom, even with his gentle demeanor, he is said to have reigned tyrannically. Out of the Factory came quantities of Pop art, avant-garde films, multimedia happenings, and the music of The Velvet Underground, a rock band managed by him, which enjoyed phenomenal success. At Factory parties celebrities and socialites rubbed shins with drag queens and hustlers in a unique setting where everything, from the floor to toilet handles, was painted silver, and there were drugs galore.

Then, in June of the pivotal year 1968, just after Warhol moved to a new studio on the sixth floor of 33 Union Square West, the radical feminist Valerie Solanas, author of a tract advocating the elimination of men, shot him, inflicting a wound that was almost fatal. I remember how this was big news, until Robert Kennedy’s assassination three days later relegated the Warhol story to the back pages. Solanas later pleaded guilty to reckless assault, was sentenced to three years in prison and released in 1971, phoned Warhol and threatened him again, then was rearrested and subsequently institutionalized several times before fading into obscurity. That Solanas, hating men, should pick Warhol as her victim is curious, since he never claimed to be, or wanted to be, a sterling specimen of manhood. My take on the two of them is simple: she’s a bore; he’s interesting. In her photos she looks like she's been force-fed on hate. But she has been hailed – by a few – as a “girl Nietzsche,” Medusa, an anti-patriarchal avant-garde militant, and a feminist/lesbian revolutionary ahead of her time. For that fifteen minutes of fame that Warhol says we all get, it seems that all you have to do is shoot someone.

Following the shooting Warhol was out of commission for weeks. He was released from the hospital in July, and on his first sortie out of his house he went to 42nd Street to see a porno movie and bought, according to a friend who went with him, the dirtiest magazines he could find. But the Factory, now much more tightly controlled, was never the same again. It is said that Warhol was so afraid of further attacks by Solanas that he would jump if even a good friend touched him. He was less scandal-prone and likewise less successful in the 1970s, when critics began criticizing his celebrity portraits as superficial and overtly commercial, but reaped more critical and financial success in the 1980s. By then his long graying hair, over a gaunt face, looked at times like a fright wig; aging was not kind. In 1987 he died following gallbladder surgery at 58.

I probably first heard of Andy Warhol when his Campbell’s soup cans caused a splash in 1962, but I never met him. We were exact contemporaries but moved in different worlds; toiling then in the glades of Academe, I would have found his entourage too bizarre, and the drug scene of the Factory repellent. Besides, the idea of 32 Campbell’s soup cans as art, especially when exhibited in a single line like products on a shelf, turned me off, old fogey that I am, so that right from the start I was suspicious of his antics and his art. The same goes for 100 Coke bottles, or 100 dollar bills, or however many images of captivating Marilyn Monroe he produced.

But my friend John has a different take on both the artist and his art. John knew him in his early years in the 1950s and has shared his impressions with me. An editor at Interiors magazine (see post #47), he got to know Andy Warhol when Warhol did cover art for the publication. John remembers commissioning him for cover art and some drawings to be used inside the magazine for the princely sum of $25.00. John’s personal impression: the artist was a gentle soul, otherworldly and precious; he describes him as “featherly.” Easygoing and friendly, Warhol was accessible; one could readily address him as “Andy.” Though he was beginning to show his serious art, he was not impressed with himself, not at all the ego-driven artist; above all, he was accommodating. For a feature article by John on music, Warhol did a semiabstract cover showing a speaker with sound waves. When the publisher saw it, he asked John to have Warhol add a small picture of an interior. John was fearful that the artist would resent this interference with his creation, but Andy replied, in his soft fey voice, “Oh that’s okay, John. That’s okay.” Yes, accommodating in the extreme.

His sexuality was enigmatic. Certainly he was gay and on the femme side; blond and “featherly,” he may have had a rough time in high school, though to my knowledge this has not been commented on. When he first hit the New York art scene, he says that the other gay artists kept him at a distance, deeming him too “swish.” Homoeroticism permeates much of his work, yet when interviewed in 1980 he claimed he was still a virgin, which confirms the impression that I always had of him. His doctor has stated that on his scrotum Warhol had prominent blood vessels like a cluster of little rubies, a condition that made him self-conscious and ashamed. That may well explain why he seems to have preferred voyeurism to full participation. His interest in porn, and the male nudity exhibited in some of his films, would seem to confirm this. “Fantasy love,” he once said, “is much better than reality love. Never doing it is very exciting.” Furthermore, John has told me how a friend of his attended a gay party where Andy Warhol was present. During some sort of sadomasochistic exhibition Warhol, standing next to him, kept uttering an emphatic “Wow!”

Whitman’s sexuality, like Warhol’s, was enigmatic; some gay lib advocates of today have assumed that every young man he befriended was a lover, but there is no hard evidence of this. Certainly his Calamus poems are suffused with eroticism. But a biographer once said of him, “Perhaps for his work to be complete, his life had to be incomplete.” The same could well have been true of Warhol.

Well reported on as Andy Warhol is, there are facts about him that many people probably don’t know. Here are some, culled from the Internet:

· He was born Andrej Varhola, Jr., in Pittsburgh in 1928, the son of working-class immigrants from Slovakia. His father worked in a coal mine or did construction work, depending on the source.· In third grade he had St. Vitus’ Dance (Sydenham’s chorea), a nervous system disease causing involuntary movements of the limbs, and became a hypochondriac, fearing doctors and hospitals. As a result, he probably delayed having his gallbladder problems treated, leading to his death in 1987.· A self-proclaimed mama’s boy, he lived with his mother in New York from 1952 to 1971; she died in 1972.· He praised Coca-Cola as a distinctly American and democratic phenomenon: all Cokes are the same, and everyone drinks them -- the President, Liz Taylor, and the bum on the street.· He is said to have phoned his press agent every morning.· He said that, contrary to popular opinion, movies make things look real, whereas real life is like watching television. When he was shot, he knew that he was watching television; it was unreal.· He once said: “I love Los Angeles. I love Hollywood. They’re so beautiful. Everything’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic.”· Another quote: “I am a deeply superficial person.”· Boys who came to lunch and drank too much wine were amused or even flattered, when he asked them to help him “paint” by emptying their bladder on canvases primed with copper-based paint.· He was a practicing Ruthenian Catholic and regularly attended Mass at the Roman Catholic church of St. Vincent Ferrer, at Lexington and East 66th Street in Manhattan.· The IRS audited him every year from 1972 until his death in 1987.· One critic called him "the Nothingness Himself." Warhol’s comment: “I’m still obsessed with the idea of looking into the mirror and seeing no one, nothing.”· He and his friends are said to have bought 2,000 bottles of Dom Pérignon to be consumed at the millennium. After his death, and long before the millennium, the bottles disappeared. · When he was buried in a suburb of Pittsburg in 1987, a copy of Interview, a gossip magazine founded by him, was dropped into the grave, along with an Interview T-shirt and a bottle of Estee Lauder perfume.· When Sotheby’s auctioned his estate, it took nine days and grossed more than twenty million dollars. · The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, with seven floors and 17 galleries harboring his art, films, and archives, is the biggest museum in the country devoted to a single artist. There remains my original question: Andy Warhol, genius or fraud? So where do I come out? Certainly, as I said earlier, he was a genius at self-promotion. I find him, perhaps not a great artist, but a fascinating phenomenon. Indeed, I’m much less drawn to Andy Warhol the artist than to Andy Warhol the person, whose contradictions intrigue me: a virginal voyeur who needed people around him yet seems never to have revealed himself fully to others. And the very things so many of us deplore in American culture – crass commercialism, the cult of celebrities, the commodification of art, Hollywood, money, Coca-Cola, plastic – he embraced and glorified. But to label him either genius or fraud is too simplistic; he may have had a bit of both in him but can’t be described so easily. Somehow he evolved from the gentle, accommodating person my friend John knew in the 1950s into the reigning monarch of the Factory in the 1960s, ruling his court like an autocrat and reveling in the fawning admiration of his courtiers. Obviously, they needed him, but he needed them as well. And from the beginning to the end of his career, I think he can be fairly described in his own words: “I am a deeply superficial person.”

Curiously, the Sizzling Sixties, that era of liberation – gay lib, women’s lib, and campus rebellions nationwide – was also characterized by autocrats: Rudolph Bing at the Met (post #84), Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio (post #41), Robert Moses at the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (post #78, though by then he was on his way out), and Andy Warhol at the Factory. But all these figures, autocrats or not, were immensely creative and produced results.

When all is said and done, I still am amazed that some anonymous buyer forked over $104.5 million for a Warhol painting. After all, he was buying the work not of an Old Master but a Young Phenomenon. But who knows how Andy Warhol’s reputation as an artist will fare in the future? These things are unpredictable. As an example I cite the French painter Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898). What, you never heard of him? Or his name only rings a faint tinkle in the cave of memory? Well, his murals and oil paintings were hot stuff back in the Third Republic, when the Impressionists were first getting known. And today, he rates close to zero or, as my friend John has remarked, as “nineteenth-century kitsch.” So it goes in the art world, as one taste yields to another, and that one to still another. Will this be Andy Warhol’s fate? I wouldn’t presume to say. But there will be more reminiscences and biographies of him – scores, hundreds – for he is an enigmatic and fascinating subject.

Puvis de Chavannes, L'Espérance (Hope).

Puvis de Chavannes, L'Espérance (Hope).If Andy Warhol still exists in some higher mode of being and is aware that a work of his sold for $104.5 million, I’m sure he’s smiling. Unless, of course, he’s too busy silkscreening God.

Allie Caulfield A sobering thought: Bourgeois that I am, I can’t help but ask who, at the Factory in its heyday, did the floors and the bathroom. A maid? Volunteers? His mother? Andy himself?? And who cleaned up after those legendary parties? Maybe his archives have the answer.

Allie Caulfield A sobering thought: Bourgeois that I am, I can’t help but ask who, at the Factory in its heyday, did the floors and the bathroom. A maid? Volunteers? His mother? Andy himself?? And who cleaned up after those legendary parties? Maybe his archives have the answer.A note on Judith Malina: In post #94 I discussed the Living Theater, its propensity for nudity, and why I kept my clothes on. From a recent article in the New York Times I have now learned that its cofounder and artistic director, Judith Malina, afflicted with emphysema and confined to a wheelchair, is still going strong at age 87. A year ago she lost the Lower East Side home of the Living, and the commercial space above it where she had lived for six years, because she couldn’t pay the rent. She has had vast experience in losing leases, but this was different. “I was crying, screaming,” she says. “They had to carry me to the car.” She now lives in an assisted-living residence for theater people in Englewood, New Jersey, where she is writing and making plans to direct new works. She likes her neighbors and the serenity of the grounds there, but yearns for the creativity of the Lower East Side, her home of many years. “If there’s going to be a beautiful, nonviolent revolution,” she insists, “it’s going to start there.” Living Theater actors visit her almost daily, and she gets into Manhattan once a week. “I feel very exiled, abandoned,” she admits, but she continues to write in her diary, some of which has been published, and next spring hopes to direct a new play of hers in Manhattan. Though she seems to keep her clothes on now, this woman is unchanged, unreconstructed. Bravo, Judith! Keep at it as long as you can.

Congressional millionaires: According to the nonprofit Center for Responsive Politics, at least 268 of the 534 members of Congress had a net worth of over $1 million in 2012. At the top of the list is Representative Darrell Issa, Republican of California, with $330 million or more. At the bottom, poor David Valadao, another Republican of California, with debts of about $12.1 million from loans on a family dairy farm. I confess that I'm surprised, since I thought that all our Congress folk, without exception, were millionaires. How else to explain their letting unemployment benefits expire for over a million Americans? Well, if they aren't all millionaires yet, they will be, if they play their cards right.

Coming soon: Four Forgotten New York Murders (the Girl in Green, a society dentist, Old Shakespeare, and Ah Hoon); Maritime New York: the Slave Trade and the China Trade (horrors, then hong merchants, white devils, and the Son of Heaven).

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on January 12, 2014 05:00

January 5, 2014

107. Two Famous New York Murders

New York City is not the murder capital of the nation or the world, an honor that other municipalities here and abroad can contend for; currently its homicide rate is in fact declining and has reached a 45-year low. But given its large population and abundance of newspapers, it has witnessed and recorded a fair number of murders over the years, famous and well reported in their time, if often forgotten today. This post will recount two of them, starting with a spectacular one involving many witnesses and therefore recorded in detail, unlike so many murders that occur clandestinely, obliging us to only conjecture about what happened. So let’s go back to the early 1900s and the Gilded Age, when crusty old J.P. Morgan ruled financially, the scandal-hungry tabloid press was rampant, and Teddy Roosevelt, who had reaped glory by charging up San Juan Hill, was president.

Stanford White, 1906

On the evening of June 25, 1906, a fashionable audience was assembled on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden, a vast Beaux-Arts structure with a soaring minaret-like tower at 26thStreet and Madison Avenue, for the premiere of the frothy musical comedy Mamzelle Champagne. At 10:55 p.m., while the performance was nearing its conclusion, a burly redheaded gentleman of fifty with an abundant red mustache entered alone and sat at the table customarily reserved for him, five rows from the stage. Resting his chin in his right hand, he seemed lost in thought, perhaps eyeing the young female performers onstage, as was his custom, since he was a practiced connoisseur of teen-age girls.

Stanford White. The cleanshaven look

Stanford White. The cleanshaven lookwas coming in with the new century,

but the older set remained hirsute. The redheaded gentleman was none other than Stanford White, the most renowned architect in the nation, whose firm had designed the very structure he was then in, as well as countless others, including the Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square and the Washington Square Arch, located in that square at the foot of Fifth Avenue. Unknown to his wife and family, his separate apartment on 24th Street, supposedly a place where he could work uninterrupted, provided a sumptuous setting for his numerous teen-age conquests, including one room with a red-velvet swing suspended from the ceiling with ivy-twined ropes, where his young mistresses often disported. White’s presence at the rooftop garden theater resulted from a last-minute decision when he postponed a planned trip to Philadelphia because his nineteen-year-old son had arrived unexpectedly in the city for a visit; they had dined together, and White had come on to the Garden alone.

Some ten minutes after White’s arrival a handsome younger man left his own table, walked about nervously while muttering to himself, then approached White’s table. As a performer onstage began the song “I Could Love a Million Girls,” the younger man took out a revolver from beneath his coat and fired three shots at point-blank range into White, one bullet hitting his left eye and killing him, while the other two grazed his shoulder. White’s lifeless body fell to the floor, and the table overturned with a clatter.

A stunned silence gripped performers and audience alike. Spectators thought at first that this was part of the performance or another of the party tricks common in fashionable circles at the time. But then, grasping what had happened, people screamed, leaped to their feet, and began a panicky flight toward the exits. At the theater manager’s insistence, the orchestra made a feeble attempt to go on playing, but the performers were frozen in horror and the panic continued. Someone put a tablecloth over the body and, when blood soaked through it, added a second one as well.

Harry Thaw. Baby-faced?

Harry Thaw. Baby-faced?Yes, just a bit. The murderer had left holding his weapon aloft to indicate that he was done shooting. When he reached the elevators, a bystander took the revolver away from him, and a policeman arrested him. “That man ruined my wife,” said the murderer. Just before the policeman took his prisoner down in an elevator, a woman rushed up and embraced him; witnesses said they believed it was the murderer’s wife. The policeman then escorted the man out of the building on the way to a police station in the Tenderloin; the man did not resist, seemed dazed. Garden employees recognized him as Harry Thaw, a Pittsburgh millionaire and man about town whose wife was Evelyn Nesbit, a beauty with a bit of a past.

The story that came out in Thaw’s subsequent trial for murder has different versions, depending on who told it and why. It is clear that Evelyn Nesbit came to Stanford White’s attention when, at age sixteen and already a successful model, she performed in the musical Floradora, an import from London that had opened on Broadway in 1900 and proved an astonishing success. Prominent in the show was a luscious sextet of young women, dubbed the Floradora girls, who attracted scores of admirers; all of the original six, it is said, ended up marrying millionaires.

The luscious sextet. With male escorts, but who noticed them?