Clifford Browder's Blog, page 53

May 19, 2013

61. Jim Fisk, part 1: Prince Erie

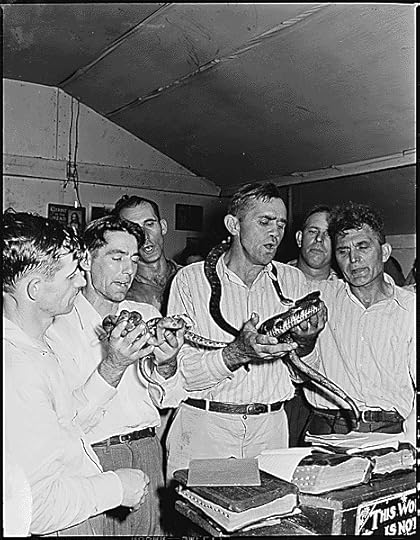

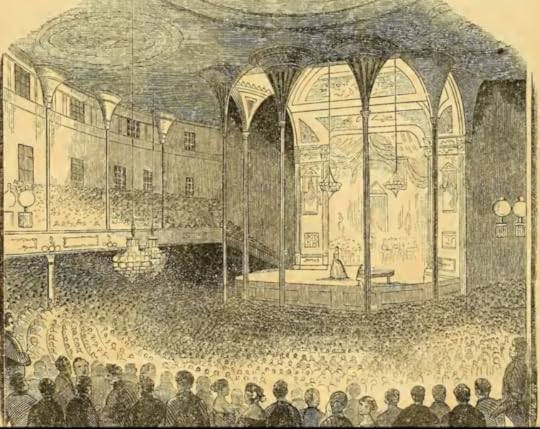

Here begins the Saga of Jim Fisk, a series of posts relating the later adventures and misadventures of the nineteenth century's most colorful robber baron. We last saw him in post #46, where, at the end of the Great Erie War, he and his pal Jay Gould inherited the Erie Railway, its coffers empty, its track two streaks of rust. He immediately moved the Erie offices into an opera house that he had just bought and renamed for himself: another Erie first -- a railroad in an opera house. What follows is slightly fictionalized, being drawn from my unpublished fiction, but it adheres closely to historical fact, and most of the dialogue is drawn from contemporary sources.

* * * * * * *

It was a marriage of opposites: Jim Fisk all grin and girth, a ruddy-faced glad-hander in check trousers and an orange or red vest, fingers studded with rings, punning and chortling to chorus girls, clerks, and reporters, the observed of all observers about whom gossip gushed; and Jay Gould, a feather of a man, puny-chested, skinny-limbed, with big dark silent eyes under a soft felt hat, and the pallor of a back-shop clerk: a thin talker, a dainty eater, gray-suited, his thoughts like quiet mice. Together, they ran the Erie Railway. Both stole; they called it “financiering.”

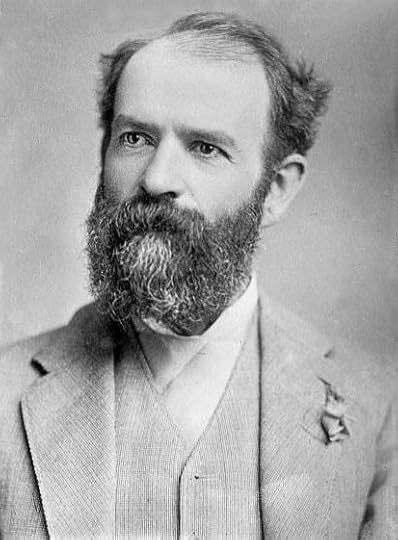

Fisk in full regalia, hair pomaded, mustache

Fisk in full regalia, hair pomaded, mustache waxed to a rapier tip.

Jim Fisk was a joyous thief, loose as change, his mind all flash and froth. To seize a little upstate railroad, he bought stock, fired off a volley of injunctions, and sent a trainload of Erie employees armed with shovels and wrenches against a trainload of workers loyal to the management. They met head on, engine to engine, whistles screeching, with a jolt, a hubbub of oaths. Fists flew, clubs thumped, skulls were cracked and gashed; outnumbered, the Erie men fled. Quipped Fisk, when informed by wire at a safe remove, “Nothing is lost save honor!”

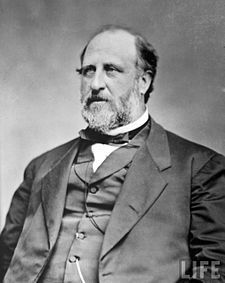

Some thought he looked a bit sinister,

Some thought he looked a bit sinister, even devilish. Jay Gould was a whispery thief immune to the bite of conscience, passionless as dawn. To meet him was to walk in river mist or a soft frost. He sat at his desk for hours, his brain tensile as a gymnast, felted as a stalking cat. Nothing so pleased him as submarine flowers of intellect, faceted crystals of thought. His mind hatched schemes so daring that even Jim Fisk gasped. When Jay Gould’s schemes fired up Jim Fisk’s bounce, Wall Street popped and sizzled.

When they locked up all the greenbacks in sight, markets splintered into panic; from all sides, insults and oaths glanced off their iron-plated egos. When they cornered Dan Drew in Erie and he came to them owing them millions, pleaded through the night (into the Sabbath – for a churchgoing Methodist, a sacrilege), huffed up, and puckered down, waxing hot, cold, hot in a web of pleas and wiles, they were adamant; and when, shoring up his pride, he said good night in a choked voice and scuffed out into the dawn, they guffawed.

Those seeking access to Jim Fisk in his Opera House office – money men, journalists, humble suppliants – entered a marble-paved lobby through portals guarded discreetly by a squad of bruisers whose job it was to keep out process servers: Fisk’s minions, the very sight of whom made Jay Gould wince. From there visitors mounted a grandiose staircase to traverse a huge hall frescoed with flowers and vines, among which nestled naked cupids and nymphs, then passed through carved oak doors into an anteroom staffed with ushers where, if approved, they were waved through a bronze gate into another great hall with frescoed walls and ceiling.

There, on a leather-cushioned throne behind a mammoth black walnut desk, sat Prince Erie, surrounded by mirrors and silk hangings, with sixteen buzzers close at hand to summon any employee in the sixteen departments of the Erie offices. While male secretaries scribbled letters that he dictated three at a time, clerks and messengers scurried to do his bidding, their laughter at his constant jokes bubbling upward under a cerulean ceiling splashed with ERIE in gold. Amid this splendor and bustle, visitors were received, schemes conceived, interviews granted, acts of random charity performed.

Such magnificence masked the frantic vibrations and rumble of a steam-operated printing press buried deep in the bowels of the basement, whereby, through what director Fisk termed “freedom of the press,” blank sheets of paper were converted into certificates of Erie stock. Thrown in abundance on the market, this watered stock had brought instant profits to Messrs. Fisk and Gould, while depressing the stock’s price to the nethermost depths. “When Erie declares a dividend,” went a Wall Street saying, “icicles will form in hell.” Though headquartered in a marble palace, the railroad was pinched for funds.

He didn't look quite so stern and imposing,

He didn't look quite so stern and imposing,when Fisk barged into his bedroom. Jim Fisk decided that Erie’s finances required his personal attention. Lugging a carpetbag and with a lawyer in tow, he barged into Commodore Vanderbilt’s red-brick residence on Washington Square to confront the richest man in the nation. Brushing past a servant, he and the lawyer bounded up the stairs and burst into the Commodore’s bedroom. The titan was sitting on the edge of his bed in a dressing gown, one slipper on, one off.

“Commodore,” said Fisk, “I’m here on behalf of the shareholders of the Erie Railway, to collect the money you swindled us out of in that settlement last July. Now here” (he opened the carpetbag) “are fifty thousand shares that you made us take off your hands at 70, which comes to three and a half million. And we want another million back that was paid you to cover your losses. So please make out a check for four and a half million dollars, with interest from July 11.”

Astonished, Old Eighty Millions reddened with rage, all the more so in that the stock was now selling for 40. “I hain’t sold no stock to Erie,” he lied, “nor received no million bonus! I hain’t payin’ you one cent!”

Hot words followed, with Fisk’s demands splintering against the iron of the old man’s will.

“Well then,” said Fisk, scooping the stock certificates back into the carpetbag, “We’ll sue.” With his lawyer he headed for the door.

Thundered Vanderbilt, “Sue and be damned!”

In the lawsuit that followed, Jim Fisk testified before the august wisdom of Justice George G. Barnard about his first meeting with the Commodore during the recent Erie war. Questioned by his attorney, he assumed a whimsical expression that had the courtroom smiling from the start.

“Sometime after our little vacation in New Jersey” (laughter), “I had an interview with the Commodore. It was pretty warm – not the interview but the weather.” (Laughter.) “I remember, because the Commodore was a bit profane about it.” (Great laughter.) “It shocked me to hear him talk that way.” (Continued laughter.)

“Did you call on Mr. Vanderbilt?”

“I think I did.”

“Do you know that you did?”

“Most undoubtedly.” (Laughter.) “The recollection is vivid and the memory green.” (Laughter.)

“What happened?”

“The Commodore received me with the most distinguished courtesy and overwhelmed me with a perfect ambulance of good wishes for my health.” (Laughter.) “Then we came plump up to the matter at hand, and we had it out. He said he couldn’t make sense of us – our outfit had no head nor tail, and old Drew was no better than a batter pudding.” (Great laughter.) “It distressed me to hear him say that, but upon reflection I said that I agreed.” (Continued laughter.) “While we were talking, I was looking at his shoes. They had four buckles. I thought to myself, if men like this have shoes like them, I must get me a pair.” (Hilarious laughter.)

During his whole testimony laughter rippled through the courtroom, cresting at times in great waves, until the judge himself was wiping tears from his eyes.

Months later, when Vanderbilt testified, he provoked no ripples of mirth. He denied heroically, lied with grandeur, or announced defiantly, “Them’s are things as I keeps to myself.” Called in turn as a witness, Uncle Daniel, sweet-tempered throughout and brimming with injured innocence, evinced pits of ignorance and bottomless chasms of oblivion. The case promised to drag on for years.

Yes, his name rhymes "greed," but

Yes, his name rhymes "greed," butlet's not push it. Jim Fisk decided that Erie’s lack of political connections required his personal attention. He went to see Boss Tweed in the Boss’s Duane Street office.

“What can I do for you, Mr. Fisk?” asked the massive Tweed.

“Boss, I’d like to talk to you about a railroad.”

The Boss grinned broadly. “Always glad to talk about a railroad.”

What exactly the two men said in the Boss’s inner office no one ever knew, but when they emerged a half hour later, they were basking in a warmth of newfound friendship that soon extended to dinners at Delmonico’s. Fisk savored the aroma of power that wafted off the Boss, while the Boss appreciated Fisk’s bonhomie, his zest for keen living and astute financiering unvexed by petty qualms. When their camaraderie expanded to include intimate suppers at Josie Mansfield’s brownstone, Tweed found Fisk’s ladylove to be a charming and most attentive hostess, while Josie, entertaining the city’s grand mogul and his cronies, was thrilled to the cockles of her heart. At the next annual election, William Marcy Tweed and City Chamberlain Peter “Brains” Sweeny joined the board of the Erie Railway.

When Judge George G. Barnard, once the wrathful nemesis of Erie, learned of Boss Tweed’s growing partiality for Jim Fisk and Jay Gould, his hard feelings toward the duo softened like a warmed lump of wax. Meeting them socially through Tweed, he found them both to be perfectly delightful fellows, and discovered that he shared specifically with Fisk (Gould being a hearth-clinging family man) the delights of good liquor, fine cigars, and the teasingly shapely legs of a cancan. Thereafter his glistening black locks, ruffled shirtfront, and diamond sleeve buttons were seen increasingly at Josie’s, where he dropped in for poker and champagne. Fisk and Barnard relished in each other a heroic risk taker immune to the buzz of fools.

This new friendship showered benefits on all. When Erie stockholders, outraged by the company’s dubious financing and perennial lack of a dividend, leagued together to enjoin Fisk and Gould and oust them from control, the duo obtained from their favorite magistrate (now a recipient of Erie stock) an injunction enjoining the enjoiners that left the two directors with their railroad snug as rats in cheese. Thereafter Fisk sent Barnard two stuffed owls symbolic of his double wisdom, and the judge’s name was blazoned on an Erie locomotive in gold.

Jim Fisk decided that the state of theater in Gotham required his personal attention. No sooner installed in the Opera House, he leased two other theaters as well, hired directors and performers, and overnight became the biggest theatrical producer in the city. Having a go at Shakespeare one month and at farce or opera the next, he piled failure upon failure until he found a winning formula at last: The Twelve Temptations, a splashy musical with a real waterfall, Spanish dancers, an Egyptian ballet, and one hundred tantalizing females kicking high in a cancan that at once became the talk of the town. He advertised like crazy; multitudes flocked.

THE DEMON CAN-CANReceived Nightly with Wild EnthusiasmTERPSICHOREAN AEROSTATICS-- The Mystery Still UnsolvedTHE EGYPTIAN BALLET-- The Most Novel of NoveltiesTHE GRANDTRANSFORMATION SCENEThe Wonder of Wonders100 BEAUTIFUL YOUNG LADIESContains Nothing Objectionable

Flaunting his shirtfront diamond, producer Fisk posted himself in the lobby before curtain time to fling a jovial greeting at Boss Tweed, Judge Barnard, dapper Mayor Oakey Hall, and lesser luminaries and friends. During intermissions he hopped from box to box or mixed with tipplers at the bar, giving of his abundant good cheer to all. At the Opera House Miss Mansfield had a box of her own just above his, though as a sop to propriety he forbore to visit it, being well aware that select members of the audience were craning their necks to glimpse the lady in question and whoever cared to be seen in her company. At the final curtain he took a bow with the cast.

So taken was impresario Fisk with Offenbach, that he sent the respected Austrian-born director Max Maretzek to Paris to lure the master of light opera to New York. Maretzek returned not with Offenbach, who declined, but with a bevy of renowned female performers to spice up the Opera House offerings. From then on manager Fisk was often seen driving in the Park with such stunning beauties as Mlle Irma and Céline Montaland, if not a whole troop of dancers. Rumors soon circulated of naughty doings in the wings of the Opera House, then tales of nightly orgies in his frescoed office, with Fisk cavorting among half-naked dancers amid a catered spread of caviar and champagne. How Prince Erie could find time for such escapades and still manage or mismanage a railroad, and keep Miss Mansfield reasonably content, no one quite explained.

So taken was impresario Fisk with Offenbach, that he sent the respected Austrian-born director Max Maretzek to Paris to lure the master of light opera to New York. Maretzek returned not with Offenbach, who declined, but with a bevy of renowned female performers to spice up the Opera House offerings. From then on manager Fisk was often seen driving in the Park with such stunning beauties as Mlle Irma and Céline Montaland, if not a whole troop of dancers. Rumors soon circulated of naughty doings in the wings of the Opera House, then tales of nightly orgies in his frescoed office, with Fisk cavorting among half-naked dancers amid a catered spread of caviar and champagne. How Prince Erie could find time for such escapades and still manage or mismanage a railroad, and keep Miss Mansfield reasonably content, no one quite explained.A scourge of old-fogey ideas, impresario Fisk barged into rehearsals to critique the scenery, calm a prima donna’s tantrum, joke with stagehands, wink at a soubrette, and offer the director some pointers based on his own vast theatrical experience (one season as a circus roustabout handling hyenas and kangaroos in his teens). Directors resented these intrusions; stagehands and performers relished them. Once, hearing that Max Maretzek, against his expressed wishes, had agreed to conduct a concert at a rival theater, Fisk burst into a rehearsal in a rage, assailing the director with a barrage of insults. Maretzek was known for his violent personality, dictatorial and intransigent. Incensed, he strode down from the podium and aimed a punch at Fisk’s nose. Fisk parried, and the two grappled and fell to the floor in a tussle, Fisk’s bulky torso ending up on top, while divas and dancers screamed. Stagehands broke it up; the two combatants retired in high dither, Fisk with a torn shirtfront, and Maretzek with a darkened eye. The director, threatening a lawsuit, quit.

Soon after this a shareholder brought suit against Prince Erie, demanding his ouster for bringing females of bad repute into the corporation’s offices, alleging “that the frequenting of the building by impressionable young clerks and by opera and theater women at the same time, with the tread of ballet girls and echoes of operas and songs, and all sorts of string and wind instruments, resounding in said building, is demoralizing to said young clerks, destructive of the company’s interests, and without parallel in railroad history.” Informed of the suit, Fisk grinned.

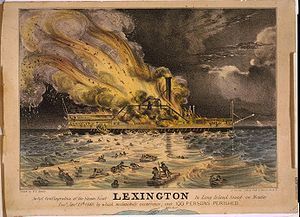

Admiral Fisk Jim Fisk decided that navigation on Long Island Sound required his personal attention. Having acquired the Narragansett Steamboat Company, running boats to Fall River, Massachusetts, he refurbished his boats with new carpets, plush upholstery, bronze statues, brass spittoons, splashes of gilt, and a band to serenade the passengers en route. Also a canary in every cabin, since he loved canaries and shunned silence and solitude. His boats, he deemed, were now more than a match for Dan Drew’s floating palaces on the Hudson, which boasted neither bands nor canaries.

Admiral Fisk Jim Fisk decided that navigation on Long Island Sound required his personal attention. Having acquired the Narragansett Steamboat Company, running boats to Fall River, Massachusetts, he refurbished his boats with new carpets, plush upholstery, bronze statues, brass spittoons, splashes of gilt, and a band to serenade the passengers en route. Also a canary in every cabin, since he loved canaries and shunned silence and solitude. His boats, he deemed, were now more than a match for Dan Drew’s floating palaces on the Hudson, which boasted neither bands nor canaries.A half hour before departure Fisk would appear on the dock in a blue naval uniform specially designed by his tailor with gold buttons and braid, and three gold stars on the sleeves – an outfit identical with the dress uniform of a United States admiral, except for lavender kid gloves and a shirtfront sparkler. Thus attired, he stood by the gangplank uttering nonsensical commands to the crew that impressed boarding passengers but by agreement were otherwise ignored, his nautical knowledge being nil. Soon afterward he hurried ashore to watch the boat depart, flags fluttering and band blaring, and receive the captain’s salute.

Known to his readers as Uncle Horace. One afternoon an older man in spectacles and with a fringe of whiskers, wearing floppy trousers and a wide-brimmed, low-crowned hat, shuffled up the gangplank. In this rumpled seeming rustic Fisk recognized Horace Greeley, the most influential editor in the nation, whose New York Tribune had spiked the Erie management on many an editorial prong.

Known to his readers as Uncle Horace. One afternoon an older man in spectacles and with a fringe of whiskers, wearing floppy trousers and a wide-brimmed, low-crowned hat, shuffled up the gangplank. In this rumpled seeming rustic Fisk recognized Horace Greeley, the most influential editor in the nation, whose New York Tribune had spiked the Erie management on many an editorial prong.“Welcome, Mr. Greeley,” he said warmly, reaching to take the editor’s carpetbag. “Come right on board. We’ll be off directly.”

Greeley’s pink moon face registered surprise; he grabbed his carpetbag back.

“My name is Fisk,” the admiral announced with a grin. “You’ve probably heard of me.”

Greeley looked puzzled, then nodded. “Oh yes,” came the high-pitched, squeaky voice. “You were an ensign in the North Atlantic blockading squadron in 1864. I wrote about you once.”

Fisk laughed merrily. “No, Mr. Greeley, I’m James Fisk, Jr., of the Erie Railway. I’m indebted to you for several editorial compliments.”

Owl-faced, Greeley eyed him through his spectacles, then announced in resonant tones, “Long ago I invested five thousand dollars in the construction of that line and to date have an eighty-percent loss. That railroad is grossly mismanaged. It should pay a handsome dividend. It runs through a rich agricultural region and – ”

Bystanders had cocked an ear, but the rest of Greeley’s tirade was lost, for at a signal from Fisk the nearby band saluted Greeley with strident blasts of “Hail to the Chief.”

Not all criticism could be muffled with a blast from a band. Erie’s workers were underpaid or sometimes not paid at all. At a machine shop in Jersey a reporter interviewed one of them, who exclaimed bitterly: “This road’s close to bust! How could it not be, when so much money goes for wine, women, and opera houses full of actresses and dancing girls? They tell me Fisk went driving in the Park the other day with a woman whose hair was full of diamonds. Diamonds, by God! We work twelve hours a day for a lousy dollar and sixty-two cents. No wonder there’s talk of a strike.”

Word of this reached the Erie offices. As both well knew, Jay Gould couldn’t talk to a gang of workers if his life depended on it, so Prince Erie decided to give the matter his personal attention. Visiting the machine shop where discontent was said to be keen, he went wearing a jaunty velvet cap and a sparkler, greeted the men heartily, ignored their sullen silence, mounted a crate to address them. He was plain Jim Fisk, he told them, an angel or a devil, since the papers had called him both. But he and Mr. Gould were spending millions on Erie's cars, engines, roadbed, and rails, so as to improve its service. As for the workers, their homes might be humble, but when their daily toil was over and they straddled the legs of their supper table, they could enjoy the evening with their family, whereas he'd spent many a night in his office studying how to whistle up a hundred million dollars by noon the next day. And he was doing it for them, because their interests were the same. And if any of them should ever come to New York, and he could help them, they should come see him in his office. With their help, he and Mr. Gould were going to make Erie the greatest corporation on the continent. "So good-bye and God bless you!"

Growing shouts of approval had seasoned his address; now, loud cheers accompanied his departure. The men returned to their jobs convinced that plain Jim Fisk was the best friend a workingman could have.

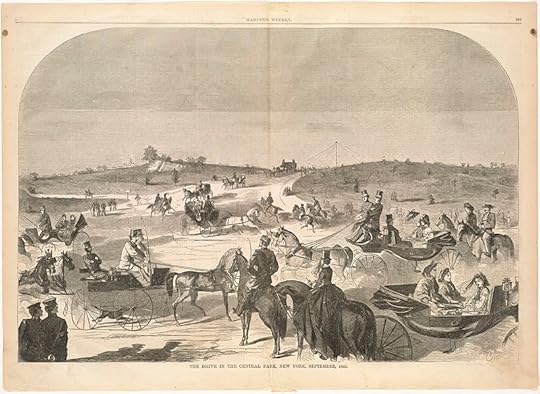

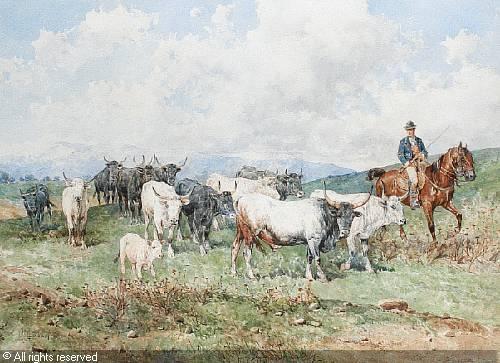

The next day he was driving six-in-hand in the Park in a turnout lined with gold cloth, three white horses paired with three black, entertaining Mlle Irma and Céline Montaland, their bright scarves plucked by the breeze; every eye in the Park was on him.

The Drive in the Central Park. Here Prince Erie loved to cavort, driving six-in-hand

The Drive in the Central Park. Here Prince Erie loved to cavort, driving six-in-handwith a bevy of dancers.

Follow-up to last week's post on fascism: From the New York Times of last Thursday, May 16:

BIG BANKS GETBREAK IN RULESLIMITING RISKS

"Under pressure from Wall Street lobbyists, federal regulators have agreed to soften a rule intended to rein in the banking industry's domination of a risky market.

"The changes to the rule ... could effectively empower a few banks to continue controlling the derivatives market, a main culprit in the financial crisis."

Neither the banks nor the regulators have learned anything. No further comment is necessary.

A solution for WBAI? As always, but now more desperately than ever, WBAI needs money. So imagine my surprise when, tuning in the other day during the current fund-raising marathon, I heard them offering as a premium two CDs entitled "Six Steps to Wealth." At first I thought it was health that they were offering, but closer listening confirmed that it was wealth. WBAI, that bastion of anticapitalism, was offering "Six Steps to Wealth" for a mere $120! The program host praised to the firmament the author of said CDs, one Dr. John Demartini, who has toiled nobly for 38 years, so he himself declares, in the cause of human betterment. Samples of the material were played, in which Dr. Demartini explained that the only obstacle between yourself and the wealth you aspire to is ... yourself! To redeem us from this predicament, he offers his six-step program. But he also has the key to countless other problems, and to those willing to pledge a mere $360 a "superpac" of his wisdom will be sent, wisdom that will change your life. That I am leery of martinis in any form has already been made clear in post #47, Discovering New York (February 2013), so I of course declined to accept these generous offers. But I had an epiphany: Dr. Demartini offers a six-step program to wealth, and WBAI desperately needs exactly that. The obvious solution: all those running the station should themselves invest $120 (or $360!) to overcome whatever it is that keeps WBAI from realizing its financial potential. What could be more clear? I truly hope that the station will embrace my suggestion. No more fund-raising marathons -- O joy! O bliss! O ecstasy!

Coming attractions: Next week, Abnormal and Paranormal Adventures (saving the world through a cosmic jack-off, floating in space and monoxide, coming back from immensities of light). Also: more Jim Fisk (the great gold corner of 1869), Who is a hero? (Obama? the Dalai Lama? Bradley Manning?), Farewells (both tearful and nasty), the Magnificence and Insolence of Trees (I love those guys). And in the works: Go Ahead: The Mania of Progress (America's favorite obsession, what it has done both for and to us). The favorite post to date: Man/Boy Love (#43, January 2013), though last week's post on fascism got a record 118 one-day views on Sunday, and another 85 on Tuesday.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on May 19, 2013 04:38

May 12, 2013

60. Is America Becoming a Fascist State?

The words fascism and fascist get used very freely, and often irresponsibly; we all do it. George Orwell once remarked that he had heard them applied to shopkeepers, farmers, fox hunting, bull fighting, Kipling, Gandhi, homosexuality, astrology, women, and dogs. But on station WBAI they are used very seriously, when any number of voices insist that this country either is already a fascist state or is fast becoming one. (Veteran viewers of this blog know that WBAI is the station I love to love and hate to hate. See post #16, July 2012, and #50, March 2013). Most Americans would probably dismiss these assertions as irresponsible, but the examples cited and the people interviewed are impressive. So here is my take on the subject, the reaction of someone with no expertise on the topic, just the random reflections of an ordinary -- a very ordinary -- citizen.

When I hear mention of fascism, these thoughts come to mind:

A charismatic right-wing leader who requires unquestioning obedience from the populace.Intense nationalism, patriotic fervor, mass rallies.The state is supreme; the individual is subordinate.Great emphasis on the police and the military.Contempt for democracy; suppression of dissent.Alliance with corporate elites.Aggressive wars. Now let's have a look at these notions, one by one.

1. For examples of a charismatic right-wing leader, we know where to look.

German Federal Archives

German Federal Archives

German Federal Archives

German Federal Archives But do we have such a leader here? No, since whatever you think of him, Obama is no Hitler or Mussolini. He's a gifted speaker, but he doesn't mesmerize the way they did, he doesn't command the blind, feverish loyalty of multitudes. (Not that charismatic leaders have to be evil. On the contrary, think of FDR and Teddy Roosevelt; both had their faults, but both accomplished a lot, and neither should be called evil.)

2. Intense nationalism? In the past yes. At the outset of the Civil War, no young man in the North who was not in uniform could hope to impress a young lady. And my parents have told me how, in Indianapolis during World War I, a young man whom they knew took to the alleys and avoided the streets, because he had not been accepted for military service. But as I recall, we were less blindly patriotic during World War II, and in the undeclared wars since then -- all of them controversial -- the flame of patriotism has often sputtered and come close to flickering out. But it is good to remember words of (or attributed to) Sinclair Lewis in the 1930s: "When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in a flag and carrying a cross." But consider this ...

Nuremberg rally, 1938.

Nuremberg rally, 1938.German Federal Archives

No, nothing like it here. Mass rallies for civil rights, for the environment, for all kinds of good and noble causes, but nothing so organized, so military.

Note on mass rallies: Back in the 1930s -- yes, I was alive back then -- I heard an American, probably a journalist and certainly no Nazi, describe one of the Nuremberg rallies. Inside the great hall all was quiet, but with great anticipation. Then, in the distance, came a sound of marching feet. Slowly, as it got nearer and nearer, louder and louder, the anticipation became intense. Then, suddenly, the doors flew open and in came masses of troops, banners, swastikas, and at the head of it all, Adolf Hitler. The spectators leaped to their feet and shouted "Heil Hitler!" And what was the American, a detached outsider, doing? Like everyone else, he was on his feet shouting, "Heil Hitler!"

3. The state is supreme; the individual is subordinate. Here, the plot thickens. Yes, we have the Bill of Rights (how many of us really know its content?), which are meant to protect each of us from tyranny, and they are supposed to be absolute, not subject to change, and in this regard, since democracy means putting everything to a vote and letting the majority prevail, they are undemocratic. But, being stated in general terms, they are subject to interpretation, and thereby hangs a tale. In fact, lots of tales.

You think your home is your castle? Are you aware that, in the recent brouhaha in Watertown, SWAT teams ordered people out of their homes at gunpoint, the residents' hands on their heads, and sent them down the street to be frisked by police? This was not a case of "hot pursuit," where a fugitive is tracked to a private home, but a suspension of the Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures. Mainstream media affirmed that the house-to-house searches were done with the consent of the residents, but this wasn't necessarily the case. In all but name, Watertown was under martial law.

Of course these searches didn't last long, and the residents were allowed to return. Owning your own home is a good part of the American dream, is it not? And one's ownership is surely secure. No, it is not. Something called the power of eminent domain allows the state to seize private property and make public use of it. Presumably, the owner will receive fair compensation, but the confiscation cannot be refused. The property seized is usually used for public utilities, highways and railroads, and public parks. But in 2005 the Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469, ruled that the city of New London, Connecticut, could seize private property and transfer it to a private developer solely for the purpose of increasing municipal revenues. This was highly controversial, and several states have since ruled to disallow such confiscations under their state constitutions. Ironically, the redevelopment project proved a failure, and nothing to date has been built on the appropriated land. But an ominous precedent has been set: private property can be seized, even if no public use of it is anticipated.

A doctor injecting a patient with a placebo

A doctor injecting a patient with a placeboduring the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Just as ominous is the readiness of government agencies, the military, and the scientific community to use the public as guinea pigs -- not occasionally but repeatedly, as can now be documented and proven. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment of 1932-72 is perhaps the most notorious case, where the U.S. Public Health Service treated 400 impoverished black men in the South over time, but didn't tell them they had syphilis and didn't treat them for it, even when penicillin became available, since the point of the study was to observe the effects of syphilis on the human body. By the end of the study 28 had died of syphilis, 100 more were dead of related complications, 40 wives had been infected, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis. The study was shut down only when it became known to the press in 1972, and the public protested vehemently.

But there have been many other cases as well. In 1950 the U.S. Navy used airplanes to simulate a biological warfare attack by spraying a presumably harmless bacteria over San Francisco, causing many citizens to contract pneumonia-like illnesses and one victim to die of it. In 1956-57 the U.S. Army conducted biological warfare experiments, releasing millions of infected mosquitoes over Savannah, Georgia, and Avon Park, Florida, causing hundreds of residents to contract fevers, respiratory problems, stillbirths, encephalitis, and typhoid; researchers, pretending to be public health workers, photographed the victims and performed medical tests on them. And so on and so on.

Of course all that occurred at a far remove from New York City and its vicinity. But from the 1950s to 1972 mentally handicapped children at the Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, in research to develop a vaccine, were intentionally infected with viral hepatitis when they were fed an extract made from the feces of patients already infected with the disease. In 1966 the U.S. Army released a harmless bacillus in the tunnels of the New York City subway system, so as to study the vulnerability of subway passengers to a covert attack with biological agents. And in 1962 Dr. Chester M. Southam injected 22 elderly patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn with live cancer cells, so as to study how healthy human bodies fight the invasion of malignant cells. When this came to light, the New York State medical licensing board placed Southam on probation for a year; two years later he was elected vice president of the American Cancer Society.

In none of these experiments had the subjects given their voluntary and informed consent. The subjects of these and other experiments were poor blacks, mentally disabled children, inmates, military personnel, newborn babies, and the terminally ill -- in other words, the most vulnerable of the population, those least able to withhold consent or register a complaint afterward. In every instance one is struck by how easily those in authority, whether civilian or military, become desensitized, dehumanized. We have condemned such human experimentation by our enemies -- the Nazis and the Japanese in particular -- yet we ourselves have repeatedly done the same. The state -- the military, the public health authorities, the scientific community -- are indeed supreme, and the individual, as exemplified by the victims of these studies, is simply material to be experimented on. Nascent fascism indeed! What put a stop to these experiments? Exposure by the press, provoking a public outcry. Are more such experiments being carried out on someone now? Who knows? But to date, I know of no one being indicted or convicted for participating in such experiments.

Source note: You may well ask, what documentation is there for these instances of unethical experimentation on humans? The answer: plenty! In the Wikipedia article on the subject there are 168 footnotes citing sources, followed by an extensive bibliography on the subject. For verification, feel free to check out that article and numerous blogs on the subject. You'll find out more than you want to know.

4. The police and military are emphasized. The account of the Watertown searches should give one pause for thought. SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) teams are teams that use military weapons and specialized tactics in high-risk operations beyond the capacity of the regular police. They carry submachine guns, assault rifles, riot control agents, stun grenades, and the like, and are used for hostage rescue, riot control, and counterterrorist operations. Clearly, they represent the growing militarization of the police.

Our friend or enemy? Surely they wouldn't be used for anything else, now would they? Unfortunately, precedent suggests otherwise. In 1987 some 25 armed FDA agents and U.S. marshals burst through the glass doors of the Life Extension Foundation in Fort Lauderdale with guns drawn. Employees were lined up against the wall and searched. Products, files, newsletters, and documents were confiscated, and computers and telephones ripped from the wall. Furthermore, the FDA filed 56 criminal charges against the Foundation's two top officers -- charges that the accused fought vigorously until, years later, they were dismissed by a federal judge.

Our friend or enemy? Surely they wouldn't be used for anything else, now would they? Unfortunately, precedent suggests otherwise. In 1987 some 25 armed FDA agents and U.S. marshals burst through the glass doors of the Life Extension Foundation in Fort Lauderdale with guns drawn. Employees were lined up against the wall and searched. Products, files, newsletters, and documents were confiscated, and computers and telephones ripped from the wall. Furthermore, the FDA filed 56 criminal charges against the Foundation's two top officers -- charges that the accused fought vigorously until, years later, they were dismissed by a federal judge.What can explain the FDA's virulent hostility toward the Life Extension Foundation? Life Extension is a nonprofit organization that publishes information about the healing power of nutritional supplements. I have seen its magazine; the writers are well credentialed, and the articles well documented. In addition to advocating a healthy vegan diet and a natural approach to healing that uses supplements and herbs, rather than pharmaceutical drugs, the Foundation has not hesitated to criticize the FDA, which many see as having ties to Big Pharma. In 2005 the journal Nature reported that 70% of FDA panels writing clinical guidelines on prescription drug usage had at least one member with financial links to drug companies whose products were covered by those guidelines; in one case, every member of a panel recommending use of a drug for HIV patients had received money from the drug's manufacturer. The FDA has since announced new guidelines prohibiting such abuses, but suspicion remains that the FDA is much too influenced by the pharmaceutical industry. No wonder the FDA hated Life Extension and didn't hesitate to send armed agents to terrorize its employees and shut it down. But Life Extension still flourishes today, advocating a healthy diet and selling vitamins and supplements, while asserting that 100,000 Americans die yearly from Big Pharma's fraudulently approved drugs. Will it be visited someday by a SWAT team? Will you? Will I? Time will tell.

Oregon Department of Transportation

Oregon Department of TransportationPersonal note: Mention of Mussolini earlier reminds me of the one and only avowed fascist I ever knew. This was in the early 1950s, when I was enrolled in a program for foreign students in Lyons, France. Also enrolled was a short, attractive Italian girl named Ritarella, who when spring came began telling other students, "Oh, les yeux bleus de l'Américain!" (Oh, the blue eyes of the American). I and my baby blues had been on the scene since the previous October, so why this belated discovery? It's simple: her Swiss boyfriend had just gone back to Switzerland. So Ritarella and I kept company for a while, albeit innocently, since she was hard to reject or avoid. On one occasion we and some other students attended a lecture by Jean-Paul Sartre, the leading French leftist intellectual of the time. When he made a disparaging remark about fascism, Rita said to me in much too loud a voice (in French, our common language), "He shouldn't have said that about fascism. I'm a fascist!" This was news to me, but I immediately and repeatedly shushed her, given the leftist nature of the gathering. Later she explained: "Democracy doesn't work in Italy. When our politicians get together, all they do is babble and scream at one another. Mussolini shouldn't have ended the way he did." I well remembered photos of il Duce and his mistress, shot by partisans and strung up by their ankles. A disgusting sight, I'll admit, and a sorry end for him, lacking the Wagnerian grandeur -- or at least grandiosity -- of Hitler's suicide in the bunker. When I mentioned Italy's getting into the war, Rita admitted that that was a mistake, but she held to it that Mussolini deserved credit for governing the ungovernable Italians, an opinion that she would no doubt reaffirm today, given the current political instability in Rome. A charming fascist, and in no way menacing. If only they were all like that!

5. Contempt for democracy; suppression of dissent. Not openly; we claim to be one of the world's leading and most successful democracies, a showcase for others. But do the people really rule, and is dissent really tolerated? The recent defeat in the Senate of a gun-control bill favored by a majority of Americans shows that once again our elected representatives are more in bed with special interest donors than with their constituents. (A bad image, given recent scandals. Or maybe a good one.) This is a familiar story and will persist until there is major campaign finance reform.

As for the freedom to dissent, yes, we can spout our opinions, but this freedom is not without threats, as seen in the FDA's attempt to eliminate the Life Extension Foundation. And what about Bradley Manning, the presumed leaker of classified documents, and Julian Assange, head of WikiLeaks, who made those documents available worldwide? While both are hailed as heroes abroad, our government is determined to make an example of them. But isn't Manning entitled to the status of whistleblower, and Assange -- now hunkered down in the Ecuadorean embassy in London -- to that of journalist? Threats to our right to dissent have to be resisted every year, every month, every day, and this can wear some people out. In an earlier post I remarked, quoting others, that 5% of the population want power, 5% want justice, and the rest simply want to get on with their lives. The greatest threat of all to democracy is the citizens' apathy. As Grandpa Al Lewis (post #19) used to say, we've got to get the asses of the masses in the streets. It's that blessed 5% concerned with justice who may, in time, make a difference. Will we listen to them?

Hero or traitor?

Hero or traitor?in the name of Freedom

Demonstration in Australia in support of Julian Assange.

Demonstration in Australia in support of Julian Assange.Elekhh

6. Alliance with corporate elites. Yes, our government is closely tied to Big Business, as noted in the FDA's hostility to Life Extension already noted. And then, there's the Washington revolving door, where those regulating an industry leave government service to work for the very industry they used to regulate, and executives of an industry enter government service to regulate that same industry. But even more egregious is the case of ALEC. Never heard of it? It's time you did, though that's the last thing ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, has wanted. Founded in 1973, ALEC is an organization of legislators, businesses, and foundations that produces model legislation for state legislatures and claims to promote free-market and conservative ideas. In many instances ALEC has written legislation that legislators then took back to their legislatures and introduced as if it had been written solely by them, without corporate collaboration. In other words, ALEC lets industry-backed legislation appear to be the grass-roots efforts of the various states. So if you wonder how legislation so favorable to corporate America, but not to ordinary citizens, gets passed, here's the answer.

No party goes on forever, though this one lasted for years. In July 2011 the Center for Media and Democracy and The Nation magazine blew the whistle, revealing ALEC's existence and modus operandi (oops! there's my Latin again). The legislators attending the annual conventions were treated to travel expenses, rooms in swank hotels, pool parties, even strip clubs. This revelation -- not the strip clubs, but the whole shebang -- provoked an exodus of members scurrying for cover like creepy-crawlies caught in a beam of light. Among those who have opted out of ALEC: Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, Johnson & Johnson, Kraft Foods, UPS, McDonald's, Blue Cross Blue Shield, Procter & Gamble, Amazon.com, Wal-Mart, Dell Computers, CVS Caremark, Hewlett-Packard, Best Buy, Express Scripts/Medco, GM, Walgreens, GE, Western Union, Sprint Nextel, Wells Fargo, Merck, Bank of America, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and others. Quite a roster of corporate biggies! Among those still listed as members: AT&T, ExxonMobil, Koch Companies Public Sector (a subsidiary of the arch-conservative Koch brothers of great or ill fame), and Pfizer. To judge by its website, ALEC itself, with its motto "Limited Government -- Free Markets -- Federalism," still functions and flourishes.

In Afghanistan today.

In Afghanistan today.Youngottoman

7. Aggressive Wars. Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, and other smaller wars, some of which we are barely aware of. Here, there's little to debate. In the federal budget for the fiscal year 2013, some estimate that as much as 47% in fact goes to the military.

So what do we conclude? Is this country becoming a fascist state? If you use the word fascist in its narrow historical sense -- meaning a state like Hitler's Germany or Mussolini's Italy -- then the answer is no. But are there alarming trends toward a state that acts arbitrarily, subordinates the individual, and ignores the popular will? With ALEC, the FDA, unethical experiments on humans, Bradley Manning, and SWAT teams in mind, I think you have to say yes. Will fascism come wrapped in the flag and carrying the cross? Wrapped in the flag, certainly, though I'm not sure about the cross. What might prevent it? Our diversity; our federal system that reserves certain powers to the states; our system of checks and balances; our free press; our very American dislike of discipline. But all that is not enough. If citizens remain apathetic, fascism -- our style of it -- will come in the name of national security with the full support of the military-industrial complex and significant elements of the scientific community. And if we let that happen, God help us!

Coming next: Jim Fisk, part 1: Prince Erie (our most colorful robber baron and his highjinks). And in the offing: The Magnificence and Insolence of Trees; Who is a hero? (Bradley Manning? Ralph Nader? Obama? John Brown?); Farewells (kiss-offs, coffins, and other partings); Abnormal and Paranormal Adventures (saving the world and turning clouds green, floating in space, coming back from immensities of light). And, at intervals, Jim Fisk.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on May 12, 2013 04:51

May 5, 2013

59. Earth Goddesses: Big Mama

Long, long ago -- back when it was legal -- I tried peyote, munching the little gray-green cacti with handfuls of raisins to counter the fiercely bitter taste. In time, when I shut my eyes, vivid fantasies resulted. One of the first was an African village with huts, then a field of high pale-yellow grass and, in the foreground, where there was only stubble, two couples making love. My attention focused on one of the women, bent over and sitting astride her lover, as she slowly sat upright and leaned back a little, as if in supreme joy. She was a mature black woman with rich, glossy chocolate brown skin, shiny black hair, white teeth, and very red lips, naked to the waist with full, firm breasts. All this in Technicolor, the heightened colors of all my peyote fantasies.

So there she was, right at the start of my peyote adventures: Earth Mom, Mother Africa, Big Mama. She has always haunted me, sneaking into my poetry and fiction, where I have celebrated her as Muck Lady, Madonna, Our Lady of Worms, Hecate of the Crossways, Deep Throat, Greasy Eve, Oomph Girl, Aphrodite, and First of the Red Hot Mamas. Which, you'll have to admit, covers a lot of ground. Where I got most of these terms I'm not even sure; they just popped up when needed and relate to goddesses of many cultures.

PHGCOM

PHGCOMIs this just a literary fiction? No, for I have experienced her every summer in parks in and around New York. For me, spring is an adolescent male, violent and aggressive, who bursts upon the scene to blast the status quo, but summer is always a woman: in fact, the Woman. I think of her as sprawling, messy, vast, and enticing, summoning me to her cavities and depths. Plunging into them, I possess her with all my senses. I plunder her berries, trample her grasses, stroke her smooth or grooved, downy-haired or prickly stems, chew her acid or pepper-hot leaves, breathe in her lemony and garlic and hot mint aromas and the smell of earth, revel in the rasp of her late-summer cicadas high in the trees, and so know intimately -- at the cost of rashes and scratches and insect bites -- the dark, tangled viscera of being.

Note: That Big Mama is of the earth, earthy, is clearer in Latin, where mater (mother) is close to materia (matter). (Forgive this bit of pedantry. To feed my ego, I have to make it known that I once studied Latin in school.)

But who's possessing whom? (Please note my use of the objective case: whom. It's wonderful to know this stuff.) By late summer her weeds overtop me. Towering above me are sweet clover, mugwort, bull thistle, wild lettuce, and the infernal giant ragweed I'm allergic to, all of them so tall and dense that I feel threatened: if autumn doesn't come soon, with winter close behind, we'll be smothered in the groin of summer, strangled by this thick, sweaty excess of growth. Summer is always excess; she wants to eat me, swallow me, suck me into the black hole of her muck. Summer, this surfeit of growth, this hungry vagina, is death.

Sweet clover. Could this stuff overwhelm you? If it grows to nine or ten feet, yes.

Sweet clover. Could this stuff overwhelm you? If it grows to nine or ten feet, yes.I don't claim originality here; I'm simply putting my personal stamp on our experience of the Mother Goddess, known to all cultures and celebrated by them throughout time. And now, a disclaimer: I'm not an art critic or art historian, nor an anthropologist or historian of religions. These are simply personal ramblings, my take on a subject that has been studied exhaustively by scholars.

One of my unpublished stories is the monolog of an Irish immigrant in nineteenth-century New York, a woman with a modest ability to heal that she got from her mother, a great healer in Ireland who got it in turn from her mother, who got it from her mother, and so on back to Eve or, better still, back to when God was a woman. When God was a woman: the notion has always intrigued me. In this story the Wise Ones -- women healers -- know that their healing powers come from a Mother Goddess with many faces whom they revere silently, never mentioning her to the men. The woman's mother in Ireland is suspect in the eyes of both M.D.'s and priests, but often, though not always, she effects remarkable healings among the common people, who believe. In this story the Mother Goddess is secret but all-powerful, benign, a source of healing. Those who believe are healed; skeptics and doubters are not.

Snake goddess from the palace at Knossos, Crete.

Snake goddess from the palace at Knossos, Crete. Chris 73 Note on "when God was a woman": Long ago I heard excerpts on station WBAI (where else?) from a book by this name, sculptor and art historian Merlin Stone's account of a peaceful prehistoric matriarchal society destroyed by the warlike patriarchal Indo-Europeans. This feminist work received a lot of attention, but was also criticized by many historians. Certainly the Minoan civilization on Crete, which flourished from the 27th to the 15th century BCE, would seem to bear her out, being largely peaceful and mostly worshiping goddesses. But whatever its historical validity, the idea holds me fast. I plan to read Stone's book.

Note on the "Wise Ones": In French, a femme sage ("wise woman") is a midwife. But throughout the ages midwives were often healers as well, with special knowledge, herbal and otherwise, that might indeed give them a name like the Wise Ones. And when I googled "Wise Ones" recently, I was amazed at the websites of New Agey cults and sects that use this term. In the eyes of male authorities, however, midwives and female healers have often been labeled witches and suffered accordingly.

Of course this is only fiction. Or is it? The earliest known prehistoric art works are crude bits of sculpture representing a mother goddess or earth goddess with outsized breasts. Presumably these were the work of early agricultural societies depending mostly on the crops they grew, and therefore eager to revere and placate the higher power presiding over those crops. But why not a male deity as well? Perhaps because the man's role in procreation was not yet clear to them, whereas the woman's role was. So in those early days the guys were left out.

Nevit Dilme

Nevit Dilme Rubens liked her fleshy. Here,

Rubens liked her fleshy. Here,he throws in her boyfriend Mars

and a Cupid. Those early sculptures were simply the beginning of a long history of celebrating Big Mama. She is there in the nude Venuses of Renaissance painters like Titian and Rubens, fleshy, ample, inviting. Today we may find them a bit too ample; our feminine ideal has scaled down. I confess that I myself find them vastly too ample; they remind me of the late summer vegetation and its threat to smother us, extinguish us. One of my fictional male characters tells of encountering a fleshy whore in his younger days; repelled, he fled from her to take refuge in a tight, well-structured world of male order and dominance where everything has its customary place, neatness prevails, and he rules over all -- his family, his employees -- as a much respected and much feared stickler. For him, the whore was chaos, a threat to the cosmos he needed and constructed. I myself am not such a stickler, but there is just one Venus that I admire wholeheartedly: Botticelli's slender adolescent who, being just born of the sea, is virginal, without amplitude of flesh and experience. She haunts me as none of those hefty other girls do. Admittedly, she's much more Maiden than Mother, and that's another, and very different, face of Woman.

Botticelli's Birth of Venus. She is born of the sea under circumstances too gross for ears polite.

Botticelli's Birth of Venus. She is born of the sea under circumstances too gross for ears polite.Yes, Venus, so sensual, so available, can easily slip into the Whore. The prophets of the Old Testament inveighed against the vegetation gods that the Hebrews were constantly tempted to worship, prominent among them the Phoenician goddess Astarte; Yahweh saw this Big Mama as a threat and a foe. The early Christian Church viewed Woman as the temptress Eve, who caused Adam's fall. Priests and monks, once they took the vow of chastity, of course identified Woman with Eve and feared that they too, being tempted, might fall. (And plenty of them did; the early Church was by no means wholly chaste.)

Johann Carl Loth (1632-1698), Eve Tempting Adam. No

Johann Carl Loth (1632-1698), Eve Tempting Adam. No apple in sight. So what was she offering him? Whatever

it was, the poor sap didn't have a chance.

But with time the Church's hostility softened, for Big Mama is too basic, too necessary, to be dismissed as a temptress and sinner. The common people revered Mary as the Virgin, the warm and compassionate Goddess who would intercede for them on the Day of Judgment. She was the Mother, the Pure One, untainted by sin. God was remote and awesome, and the Son could be severe in his judgments, but the Virgin was approachable: she knows, she feels, she understands. (But as Henry Adams mentions in Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres, she has little interest in bankers, which is well worth pondering today.) So powerful was her cult, the male-dominated Church came to embrace the time-honored rule If you can't lick 'em, join 'em, and therefore welcomed her and encouraged her worship. The Romanesque churches of Europe honor this or that saint, but the great Gothic cathedrals, coming later, are invariably dedicated to the Virgin. Once again, the Goddess triumphed, and this time in her most benign persona.

A new twist comes in the New Testament's visionary Book of Revelations, chapters 17 and 18, which describe a woman arrayed in purple and scarlet sitting astride a seven-headed scarlet-colored beast, and decked with gold and precious stones and pearls, and holding a golden cup "full of abominations and filthiness of her fornication." Written on the woman's forehead are the words "Babylon the Great, the mother of harlots and abominations of the Earth." The meaning of this Whore of Babylon has been interpreted variously, but the standard interpretation sees her as representing the pagan Roman Empire when it was persecuting Christians. Here, obviously, the Mother assumes a mask of harlotry and evil.

A colored woodcut from Luther's translation of Revelations 17.

A colored woodcut from Luther's translation of Revelations 17. Luther identified the Whore of Babylon with the Catholic Church.

Obviously, the interpretation varied according to the interpreter.

Do we have Goddesses today? Of course, albeit secular ones, all over the place. Movie goddesses and theater goddesses and TV goddesses, but you'll notice that I deny them the upper case. Most often these are of glamour gals of no great accomplishment, hardly worthy to be ranked with the time-honored Earth Goddesses and Big Mamas of yore. But there are some remarkable exceptions:

Sophie Tucker, the "Last of the Red

Sophie Tucker, the "Last of the Red Hot Mamas," in furs. She famously

observed, "I've been rich and I've been

poor. Believe me, honey, rich is better."

Bessie Smith, "Empress of the Blues."

Bessie Smith, "Empress of the Blues."Carl Van Vechten

The incomparable Mae West. "It's not

The incomparable Mae West. "It's not the men in your life that counts, but the

life in your men."

Allan warren

The gay contingent have always worshiped Woman, even though (or because?) they don't sleep with her. But not just any woman; they flock to older women of great accomplishment, usually in the performing arts. (They have little interest in the Maiden, whom the Hero of legend wins by performing acts of great courage.) I have never been a part of this scene, not having the stuff of a courtier, but many of my friends have participated. These goddesses are too familiar to name. Nothing new here; Sarah Bernhardt drew to her salon in Paris a circle of gay writers, forgotten today but well known in their time. What motivates these worshipers? Recognition of true talent? The need of yet another mother? Identification? A little of all these? I've consulted several friends, but they have no explanation beyond the obvious recognition of talent. In the case of one performer, it probably involves identification with her vulnerability. But the others always seemed marvelously on top of things. So what explains it? I'm open to suggestions.

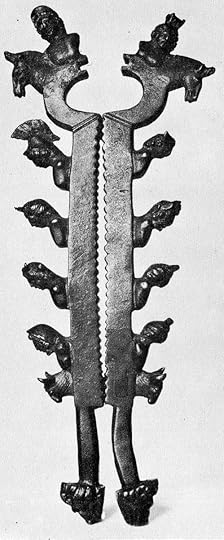

A bronze castration clamp,

A bronze castration clamp,used in the cult of Cybele. Worship of the Goddess could be risky. One of many religions flourishing in ancient Rome before the triumph of Christianity was the Phrygian cult of the Magna Mater or Great Mother, also called Cybele, the mother of gods and men and the source of all life, who was especially identified with wild nature. She had loved the shepherd Attis who, to punish himself for infidelity, castrated himself and died. Mourned, resuscitated, and then deified by her, Attis was worshiped along with the Goddess. Their annual spring festival lasted several days; on March 24, the Day of Blood, neophytes danced wildly to the sound of flutes, drums, pipes, cymbals, and tambourines, then cut themselves with knives, and at the height of their frenzy, when insensitive to pain, castrated themselves and flung their severed members onto the lap of the Goddess's statue, thus achieving union with both her and Attis. It is even possible that some men, mere bystanders witnessing the dance, became so caught up in it that they too emasculated themselves, which must have made for sobering reflection afterward. Contemporary writers mention the "mincing" walk of the Galli, or eunuchs, and even after the coming of Christianity Saint Augustine tells of Galli "parading through the squares and streets of Carthage, with oiled hair and powdered faces, languid limbs and feminine gait, demanding from the tradespeople the means of continuing to live in disgrace." There is little doubt as to who these devotees were, which invites further reflection on the gay worship of Big Mama. How much of a sacrifice does she demand, and why? Books could be written ... and maybe have been.

The Archigallus, or head priest of the Galli,

The Archigallus, or head priest of the Galli, sacrificing to Cybele. But the offering isn't

what you think. As a Roman citizen, he

himself was barred from emasculation.

Lalupa

Note on "mincing": This is obviously a code word for "gay" and "femme," but I have yet to see anyone, gay or otherwise, walk with a "mincing" step. Am I missing something or is this fiction pure and simple?

So we have come at last to the dark side of the Goddess. Kali is the Hindu goddess of time and change, often presented as dark and violent and associated with death and destruction, though she is also worshiped as a benevolent mother goddess. She is described as having four arms and being black in color (black symbolizing the infinite), her hair sometimes disheveled, her eyes red with rage, her tongue protruding from her mouth. In the middle of her forehead is a third eye that represents wisdom. Her two right hands make gestures of fearlessness and blessing, but her two left hands hold a sword and a severed human head. Often she is shown naked, or wearing a skirt made of human arms and a garland of human heads. Not someone you would care to encounter, or even imagine, on a dark night, though that is exactly when she is worshiped in Bengal. The Thugs, professional assassins who once roamed the highways of India, killing travelers and stealing their valuables, belonged to a cult that worshiped her and asked for her blessing before setting out on a murderous expedition. A rather complex lady, as you can see, having many aspects, some of them quite contradictory and some of them just plain nasty.

The Kali idol at Dakshineshwar.

The Kali idol at Dakshineshwar. Jagadhatri

Luidger

LuidgerRivaling Kali in the dark and sinister is Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess who gave birth to the moon and stars, and to the god of the sun and war. She was also known as a goddess of the earth, a goddess of fire and fertility, and of life, death, and rebirth. "Coatlicue" in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, means "the one with the skirt of serpents," and she was represented as a woman wearing a skirt of writhing serpents and a necklace of human hands, hearts, and skulls, her face formed by two serpents meeting head to head. She was the devouring mother, the insatiable monster containing both womb and grave, the force consuming everything that lives. I have seen this famous statue of her in the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City, and believe me, it's a sight you won't easily forget.

Kali and Coatlicue, life and death inseparable in each of them, the goddess turned monster, wise but ruthless, a terrifying force to be placated, to be worshiped. Ignore her at your peril.

India and pre-Columbian Mexico? Again, you may ask, what's the connection with New York? Except for the Virgin in Catholic churches, the cult of the Mother Goddess isn't exactly widespread in the city. Admittedly it's a bit of a stretch, but representations of Big Mama are here all over the place. In the Met, for instance:

[image error] InSapphoWeTrust

Yair Haklai

Yair Haklai Random Variables

Random VariablesAnd at the Museum of Modern Art:

You will never get clear of her, nor should you.

Women too worship the Goddess. How could they not when, being one with them, she bestows fertility and imparts secrets of healing? But most societies are male-dominated, and that does much to shape her image and role. What, then, is this all about? It's about how men regard women. Ever since male-dominated societies replaced that much earlier society of the time when God was a woman, men have admired, glorified, and revered Woman, possessed her, been baffled by her, loathed her, dreaded her. What they cannot do is ignore her. She is the mysterious Other, a vital force, the source of human life. So it has been and always will be, as long as there are humans on this earth. Today's feminism simply adds spice to the drama.

As for the Goddess's contradictions, consider the Coptic manuscript of a Gnostic poem from the 2nd or 3rd century CE, discovered with other Gnostic texts in a sealed earthenware jar in Upper Egypt in 1945. Probably these texts were a library hidden by Christian monks from a nearby monastery, when such works were banned as heretical. The poem is a long monolog by a female divinity addressing her worshipers or potential converts; an excerpt follows.

For I am the first and the last.

I am the honored one and the scorned one.

I am the whore and the holy one.

I am the wife and the virgin.

I am the mother and the daughter.

I am the barren one and many are her sons....

For I am knowledge and ignorance.

I am shame and boldness.

I am shameless; I am ashamed.

I am strength and I am fear.

I am war and peace.

Give heed to me....

But I, I am compassionate and I am cruel

Be on your guard!

There speaks Kali/Madonna/Cybele/the Whore of Babylon/Aphrodite/Eve. Forbidden knowledge. No wonder the monks had to hide her in a sealed jar buried deep.

Note on Union Square: On the morning of May 1 I happened to find myself in Union Square again, chiefly to visit the greenmarket, which I reported on in an earlier post (#17, July 2012). The first thing I saw: police barricades along the curb -- a reminder that this was indeed May 1 and demonstrations were anticipated. The second thing: a pianist sitting at an upright piano and pounding away on the keys. The third thing: an anarchist stand with loads of free pamphlets; I helped myself to three: "Anarchist Basics," "Profiles of Provocateurs," and Noam Chomsky's "Notes on Anarchism." The fourth thing: a black woman in a turbanlike headdress and bright red jacket, sitting cross-legged on a purple cloth, evidently selling fabrics and small packets, perhaps of exotic scents; she was straight out of The Arabian Nights or a Hindu legend. Then, finally, I got to the greenmarket and its stands selling honey, hard cider, wheatgrass, horseradish jelly and fig jam, apples, potted herbs, and acres of flowers. Also on hand were the Garden of Spices poultry farm, and Roaming Acres Farm with pure Berkshire pork and ostrich jerky (no nitrates). Later, as I was leaving the market, a seven-man band came marching, blasting away a kind of music that wasn't quite ragtime and wasn't quite jazz: a rousing finale to my visit. And quite a visit it was, though what I saw was only the appetizer anticipating the feast to follow, the afternoon May Day demonstrations. Where but in New York?

Banknote: JPMorgan Caught in Swirl of Regulatory Woes: such was a boldface caption on page 1 of the New York Times of Friday, May 3. Which strikes me as a rather cheap shot by both the Times and the federal government. Talk about hitting a man when he's down! The authorities are just piling one charge on top of another, as if to lay low once and for all a noble institution that dates back to the age of old J.P. himself, that most august of bankers and a real American. Jamie Dimon, the CEO, says he's sorry. Isn't that enough? Has the government no compassion? Shame on it and on the Times. When I go to my branch of that fine institution, I'm greeted with the most cordial hellos. The Easter Bunny and the balloons are gone, but there is candy everywhere; when I made my modest deposit, the teller thrust a chocolate goodie at me with the warmest smile. Clearly, this is not an evil institution. The government should leave it alone -- it and all the other fine banks that strive so tirelessly to serve us all. Libertarians, unite! If our meddling government must investigate someone, let it investigate Occupy Wall Street and the May Day demonstrators, or street food vendors, or sidewalk artists, or other suspect individuals. But leave our banks alone! In the words of Alexander Pope, "To err is human; to forgive, divine." Why can't our government be a little bit divine?

Next week: Is America Becoming a Fascist State? (WBAI-inspired, with arguments for and against). Then, in whatever order: The Saga of Jim Fisk (in several posts), Farewells (coffins, kiss-offs, a mother's rage), and the Magnificence and Insolence of Trees. And maybe: Who is a hero?

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on May 05, 2013 05:16

April 28, 2013

58. Steamboat Wars on the Hudson

Capitalism loves competition. America loves competition. Think of Apple vs. Samsung today, or AT&T vs. Verizon, or Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi-Cola, or years ago, Macy's vs. Gimbels (as seen in the old holiday-season movie Miracle on Thirty-fourth Street), or any number of other corporations. Competition is in our blood and bone. And for sure, it's in the blood and bone of New York. But competition today is tame and genteel, compared to the nineteenth-century steamboat competition on the Hudson.

June 13, 1840: As the steamboat Napoleon, 179 tons, a small, ill-furnished vessel skippered by Joseph D. Hancox, a feisty captain who had challenged the prevailing Hudson River Steamboat Association, pulled away from its North River dock with a load of passengers and headed up the river toward Albany, the much larger De Witt Clinton, 500 tons, broke away from its berth and, with full steam up, headed straight for the other boat. As a crowd, dawn there by rumors of a confrontation, watched from the waterfront, Hancox signaled the De Witt Clinton frantically and, when it still bore down, whipped out a revolver and fired three shots at the other boat's pilothouse, hitting no one but forcing the pilot to duck. Moments later the larger boat rammed the Napoleon just aft of the pilothouse, causing it to careen violently amid the screams of its terrified passengers. Miraculously, the boat then righted itself and continued on its way. Had the De Witt Clinton struck its rival square amidships, as it had evidently intended, the Napoleon would surely have sunk. Yet when the Napoleon reached Albany and word of the incident spread, it was not the attacking vessel's captain who was arrested, but Hancox, charged with felonious assault with his revolver. Pleading self-defense in the shooting, and backed up by dozens of his passengers as witnesses, Hancox was readily acquitted, after which he slashed his fare to fifty cents and continued to challenge the Association.

Standing on the forward deck of the De Witt Clinton during this incident was veteran steamboat operator Isaac Newton, a member of the Association, who was presumably on hand to oversee the operation. This was a time of cutthroat competition on the river, when the approved methods of eliminating a rival were to buy it off or, failing that, to steal its berth and passengers, to race it, to crowd it, or to smash it. Since Hancox was that rare phenomenon, a rival captain who couldn't be bought off, Newton had decided to ram his boat and disable it. Fortunately for his legacy, he was also a gifted ship designer who soon teamed up with Daniel Drew, the cattle drover turned tavernkeep turned steamboat operator (see post #54), to found the People's Line and operate boats on the lucrative New York-Albany run, Newton designing their ships while Drew handled the finances.

If Newton's reputation didn't suffer much from this incident, it's because keen rivalry and all that resulted from it were the rule on the Hudson. All up and down the river runners selling tickets solicited travelers boisterously on the piers, praising their line's boats while decrying those of any rival line, whose boilers, they liked to tell nervous ladies, were anything but safe. Yet when a steamboat approached any intermediate landing, no passenger dared assume there would be even momentary contact between the vessel and the landing, or even between the boat and himself. If the boat was racing it would probably shoot right past the landing, or failing that, it would execute a "landing on the fly," lowering a small boat that, joined to it by a rope, was propelled by the vessel's momentum to the dock, where it hastily discharged passengers and their baggage and took on more of the same, and then was drawn back to the vessel by a windlass on the vessel's deck, the vessel having lost little time in the process. Such landings were even performed at night, with considerable risk to the passengers.

Vanderbilt again, but not yet

Vanderbilt again, but not yet "Commodore."

Steamboat skippers and owners relished the prevailing competition, each being determined to prove that his boat was the best and fastest on the river. Memorable was the contest of June 1, 1847, when Cornelius Vanderbilt pitted his luxurious new C. Vanderbilt, named modestly for himself, against the speedy Oregon of his pugnacious rival George Law, a coarse-featured canal construction contractor turned banker and railroad man who was branching out into steamboats as well. During the race on the Hudson, Vanderbilt in his excitement seized the wheel from the pilot and mismaneuvered his vessel, while Law, out of fuel, hurled furniture and costly fittings into the furnaces and so sailed on to win.

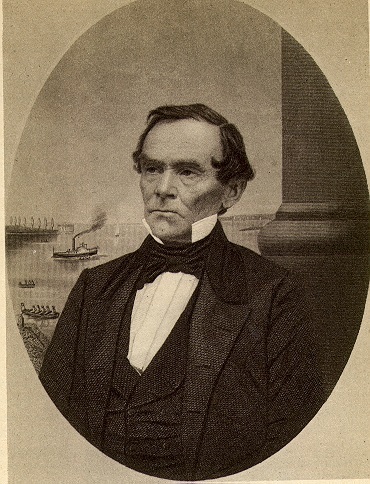

Daniel Drew in his steamboating days.

Daniel Drew in his steamboating days.No whiskers yet, and not yet "Uncle Daniel."

Such passion was beyond Daniel Drew, an astute money manager who lacked the gut feeling of a river man, the skipper's fervent identification with his boat, his confidence that it was the best damn boat on the river and he'd race anyone fool enough to doubt it. One can't imagine Drew planting himself on the forward deck of a boat just prior to a planned collision. As for hurling sofas into a furnace during a race, why good heavens, those things cost money!

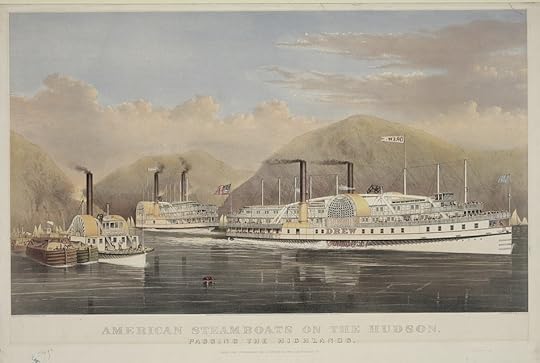

Drew and Newton knew there were defter ways to compete. Country boys who had evolved by way of the freight barge and the cattle yards, they grasped early that the key to success on the Hudson was luxury. Rivaling their countrymen's lust for speed was their longing for regal elegance: the craving of egalitarian, homespun America for palatial opulence such as few citizens could afford in their private lives, but they could enjoy briefly for the price of a steamboat ticket. The result was a trio of floating palaces such as the world had never seen, to construct which they marshaled the skills and resources of the East River and Brooklyn shipyards for the hulls, the great ironworks of the city for the engines, and the massed talents of the carpenters, plumbers, painters, gas fitters, upholsterers, furniture and glass makers, and privisioners -- not to mention the journalists -- of New York.

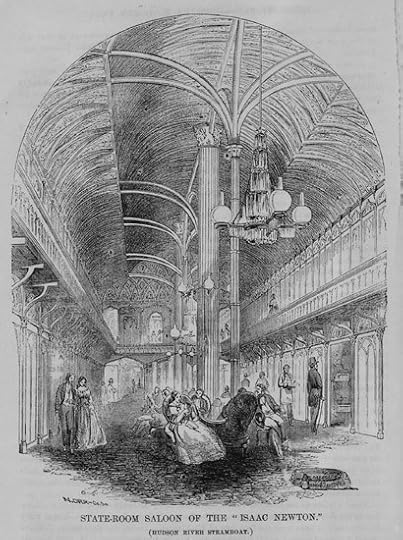

The first of these marvels was the mammoth Hendrik Hudson, which went into service in October 1845: a night boat with berths for 620 people and other accommodations for, it was claimed, two thousand -- admittedly a rather fanciful number. A reporter, surveying its illuminated interior with spacious saloons flanked by cabins, likened it to Cleopatra's royal yacht at night. But exactly one year later the second marvel appeared: the Isaac Newton, with the biggest engine ever built in America, a main saloon with a stained-glass dome overhead, and luxurious staterooms, the fanciest being the Bridal Room, with carpeting said to be from the drawing room of King Louis-Philippe of France, and over the bed a painted altarpiece featuring a cupid holding two doves over an altar, which a spellbound journalist hailed as "one of the most splendid achievements of taste."

The stateroom saloon of the Isaac Newton.

The stateroom saloon of the Isaac Newton.Unsurpassed luxury, until the next boat

surpassed it. Could such marvels be surpassed? In the age of Go Ahead, if one had eclipsed all others, what remained but to eclipse oneself? In June 1849 the day boat New World appeared, the longest and largest river steamboat ever built, with furnishings that included satin damask chairs, marble tables from Italy, Corinthian pillars, and real oil paintings on the walls. On its first trip up the river it was saluted on land and water the full length of its run, and greeted in Albany by twenty thousand people thronging boats and wharves, who waved handkerchiefs and cheered while bells tolled and cannon boomed. Thereafter the paying public flocked aboard the New World and the other People's Line vessels hundreds at a time, until on September 4, 1850, when a state fair was luring unprecedented multitudes to Albany, the New World on a single trip broke all records by carrying an astonishing twelve hundred passengers. Thanks to the managers' grandiose vision, the profits of the People's Line soared.