Clifford Browder's Blog, page 51

August 21, 2013

81. Colorful New Yorkers: Battling Bella and the Queen of Mean

This post is about two assertive women, born in the same year only twenty days apart, who became celebrities, one of whom it's hard not to like, and one of whom it's hard not to hate.

Battling Bella

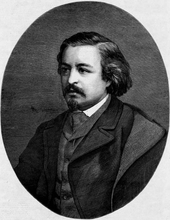

Bella in 1971. Bella Abzug (1920-1998) was New York born and bred; she looked it, sounded it, and acted it. She was born Bella Savitsky in the Bronx, both of her parents Russian Jewish immigrants, her father a kosher butcher. When her father died, Bella, age 13, went against tradition by saying the Mourner's Kaddish for her father, who had no son, perhaps the first of many feminist gestures to come. President of her high school class, she went on to Hunter College and then to Columbia, where she got her degree in law. Practicing labor law in the 1940s, she took to wearing wide-brimmed hats so as not to be taken for a secretary -- not stylish hats, to judge from photographs, but rather plain ones with the wide brim that would become her trademark. Soon she was taking on civil rights cases in the segregated South and advocating liberal and feminist causes. "This woman's place is in the House -- the House of Representatives," she announced in 1970, and in the following decade got herself elected to the House from Manhattan's West Side for three terms.

Bella in 1971. Bella Abzug (1920-1998) was New York born and bred; she looked it, sounded it, and acted it. She was born Bella Savitsky in the Bronx, both of her parents Russian Jewish immigrants, her father a kosher butcher. When her father died, Bella, age 13, went against tradition by saying the Mourner's Kaddish for her father, who had no son, perhaps the first of many feminist gestures to come. President of her high school class, she went on to Hunter College and then to Columbia, where she got her degree in law. Practicing labor law in the 1940s, she took to wearing wide-brimmed hats so as not to be taken for a secretary -- not stylish hats, to judge from photographs, but rather plain ones with the wide brim that would become her trademark. Soon she was taking on civil rights cases in the segregated South and advocating liberal and feminist causes. "This woman's place is in the House -- the House of Representatives," she announced in 1970, and in the following decade got herself elected to the House from Manhattan's West Side for three terms.

When Bella hit Washington, the Old Boys' Club was jolted by a rampaging tiger. She was soon known for her hats, her intelligence, her flamboyance, her New York chutzpah. Not to mention her voice, which Norman Mailer said "could boil the fat off a taxicab driver's neck." Assertive, aggressive, not given to compromise, she stepped on many toes. "I spend all day figuring out how to beat the machine," she wrote in a journal, "and knock the crap out of the political power structure." Always an advocate of change, she spoke scathingly of the Congressional club, the seniority system, the log-rolling and back-scratching typical of Congress. She delighted in being one of the first, if not the first, in embracing what seemed to be radical causes: Nixon's impeachment (she was on his enemies list), getting out of Vietnam, women's rights (she was a friend of Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan), gay rights, national health insurance, laws against employment discrimination. Ralph Nader said that her sponsorship of a measure often cost it 20 to 30 votes. And Jimmy Breslin told how during a quarrel over scheduling she punched one of her campaign workers, then phoned him the next day to apologize; "How's your kidney?" she asked. Even so, in a survey her colleagues named her the third most influential member of the House. And if she made enemies, she also made friends. Said her lifelong friend Gloria Steinem, "She's fierce and intense and funny. She takes everyone seriously.... And she's willing to change her mind."

Bella with Mayor Ed Koch (left) and President Jimmy Carter, 1978. I never encountered Bella face to face, but my partner Bob once, quite by chance, heard her giving a campaign speech to a crowd of several hundred in Sheridan Square from a platform mounted on the back of a pickup truck. Far from flamboyant, she was level-headed and talked sense, but with warmth; the spectators applauded with enthusiasm. So impressed was Bob that he registered for the first time ever, so he could vote for her in the mayoral election. Alas, she lost in the primary to Ed Koch.

Bella with Mayor Ed Koch (left) and President Jimmy Carter, 1978. I never encountered Bella face to face, but my partner Bob once, quite by chance, heard her giving a campaign speech to a crowd of several hundred in Sheridan Square from a platform mounted on the back of a pickup truck. Far from flamboyant, she was level-headed and talked sense, but with warmth; the spectators applauded with enthusiasm. So impressed was Bob that he registered for the first time ever, so he could vote for her in the mayoral election. Alas, she lost in the primary to Ed Koch.

On weekends Bella returned to her residence on Bank Street in Greenwich Village to spend time with her husband, Martin Abzug, whom she had married in 1944. A stockbroker and author, he had little interest in politics but stuck by her through thick and thin; she called him her best friend and supporter. They had two daughters.

In the long run her abrasive manner hurt her career. She ran for the Senate in 1976 and lost narrowly in the primary, then ran for mayor in 1977 and lost in the primary to Ed Koch. Other defeats followed, but she continued to practice law and worked tirelessly for women's causes. It's not surprising that she failed to accomplish many of her goals in Congress; she was too blunt, too unsubtle, too fierce.

"I've been described as a tough and noisy woman, a prizefighter, a man hater, you name it," she wrote in a journal that was published in 1972 as Bella. "But whatever I am -- and this ought to be made very clear at the outset -- I am a very serious woman." That she was. If one is out of the reach of her abrasiveness, one can't help but like her. Certainly I can't.

In her later years Bella kept up her busy schedule of work, even though she traveled in a wheelchair. She died in 1998 from complications following open heart surgery. She has been inducted into the Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York, the site of the first Women's Rights Convention in 1848.

The Queen of Mean

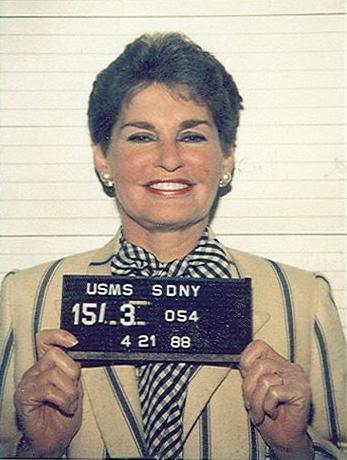

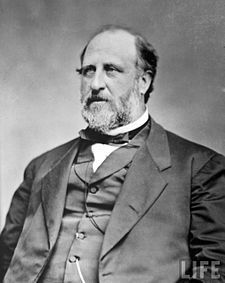

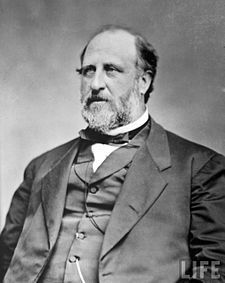

This photo has been cropped; see below.

This photo has been cropped; see below.

Leona Helmsley (1920-2007) was born Leona Mindy Rosenthal in Marbletown, New York, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Poland, her father a hatmaker. She grew up in Brooklyn and dropped out of college allegedly to become a model, though her modeling career remains unsubstantiated. Certainly she had business skills and an outsized ambition. In time she joined a New York real estate firm and became a condominium broker, finally working for real estate mogul Harry Helmsley. She was already a millionaire and twice divorced when, in 1972, she married Helmsley, who divorced his wife of many years to marry her. From then on she worked with him to build a real estate empire that included the Tudor City apartment complex on the East Side of Manhattan, the Empire State Building, the Helmsley Palace Hotel on Madison Avenue, and many other hotels in New York City, Florida, and elsewhere.

The Helmsley Palace Hotel, now the New York Palace Hotel, on Madison

The Helmsley Palace Hotel, now the New York Palace Hotel, on Madison

Avenue. In the foreground is the Villard Mansion, built by railroad magnate

Henry Villard in 1884. Behind it is the 55-story tower built by Harry

Helmsley. The hotel combines the two.Americasroof

A lackluster millionaire before the marriage, Helmsley's life was sparked up afterward. He and Leona moved into a ten-room duplex with an indoor swimming pool atop their luxurious Park Lane Hotel on Central Park South, but soon also acquired an estate in Connecticut, a condo in Palm Beach, and a mountaintop hideaway near Phoenix, not to mention a private hundred-seat jet with a bedroom suite so they could gad about in comfort. Leona is said to have had a minimum of twelve pictures of herself in every room of her residences. She gave lavish birthday parties for her husband ("my pussy cat, my snooky, wooky, dooky"), and on her own birthday her snooky floodlit the Empire State Building with her favorite colors at a cost of $100,000 ("Less than a necklace," said the pussy cat). As F. Scott Fitzgerald famously remarked, "The rich are different from you and me."

I recall lavish ads for the Palace Hotel showing her, dressed in the height of fashion and crowned with a tiara, inspecting her troops, the hotel's uniformed employees, with the caption "The Queen stands guard." Indeed she did, being a demanding and tyrannical monarch. A friend of mine was once interviewed for a job with her as chef, and was warned by the interviewer that he would have to be available 24/7, in case Mrs. Helmsley planned a dinner for seventeen at 2 a.m.; he didn't get the job because "your personality would not meld well with Mrs. Helmsley's." When she took her early morning sessions in her swimming pool, a more compatible liveried servant was on hand with a platter of fresh-cooked shrimps; at the end of each lap she would command, "Feed Mama," and he would hand her a shrimp. But her anger was fierce. Discovering a wrinkled bedspread, she shouted, "The maid's a slob! Get her out of here. Out! Out!" And a lawyer friend who once breakfasted with her has told how, when a hotel waiter brought him a cup of tea with a tiny bit of water spilled in the saucer, she grabbed the cup from him, smashed it on the floor, and made him get down on his hands and knees to beg for his job. No wonder she came to be known as the Queen of Mean.

The uncropped photo, her mug shot upon

The uncropped photo, her mug shot upon

her arrest in 1988. The most radiant mug

shot I've ever seen. After her conviction

she looked less radiant. All this changed in 1988, when U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani (the future mayor) brought charges against the Helmsleys for evading federal taxes by illegally billing the expenses of remodeling their new mansion in Connecticut to their hotels as business expenses. Harry Helmsley's deteriorating health led to a court ruling that he was mentally and physically unfit to stand trial, so Leona faced the charges alone. At the trial her arrogance and greed were amply demonstrated, and a former housekeeper testified that she had once told her, "We don't pay taxes. Only the little people pay taxes." She denied having said it, but it was consistent with her character. When I heard that statement, I knew that the IRS would nail her, and sure enough, in August 1989 she was convicted on numerous charges that included conspiracy, mail fraud, and tax evasion. While she sobbed quietly in the courtroom, her lawyer pleaded with the judge not to make her serve time in prison, which might endanger her health. The judge was adamant, but her attorney was able to get a reduced sentence, and she was ordered to report to prison on the day federal taxes are due, April 15, 1992. She was released on January 26, 1994, with 750 hours of community service to perform.

Was she sobered by her time in prison? Had she changed? She had always insisted that she had done no wrong, that she was targeted because she was a woman. Assigned to a hospital in Arizona to do community service, she was required to stuff envelopes and wrap presents for volunteers to give to the patients. There she complained that the staff "gawked at her" and were "less than charitable," so the court permitted her to do the service at home. But the judge soon learned that she had assigned much of it to her servants and so added another 150 hours of service.

As a convicted felon Leona Helmsley couldn't run enterprises with liquor licenses, so she had to give up managing the hotels. When her husband died in 1997, she said, "My fairy tale life is over. I lived a magical life with Harry." Estranged from her grandchildren and with few friends, she lived alone in her lavish apartment atop the Park Lane Hotel with her Maltese dog, Trouble. Her face was now frozen into a scowl by multiple face lifts. When she died of heart failure in 2007, she left the bulk of her fortune to a charitable trust, and $12 million to Trouble, this last being ranked third in Fortune's "101 Dumbest Moments in Business"; the bequest was later reduced by a court to $2 million. She and Harry are buried in a luxurious Greek-style mausoleum with stained-glass windows in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Westchester County. Trouble, the richest dog in the world, died in December 2010, her every need seen to around the clock, and watched over by a full-time security guard because of death and kidnapping threats. Her keeper had spent $100,000 a year on her care.

The Helmsley Mausoleum in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

The Helmsley Mausoleum in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

Did Bella and Leona ever meet? Not to my knowledge. If they had, it would have been epic. I can't imagine them hitting it off. The Queen of Chutzpah vs. the Queen of Mean -- how the fur would have flown!

Coming soon: Next Sunday, Who makes money when America goes to war? New York, 1861-1865 (with glances at today). Next Wednesday, Colorful New Yorkers: Diamond Jim and Texas Guinan, but with Jim's pal Lillian ("Luscious Lillian") Russell and her famous hour-glass figure thrown in. In the works: the Titan of the Met, who claimed to have a heart of stone, and an aristocrat of the people who, like Dolly Levi in The Matchmaker, believed that money should be spread around like manure in order to make things grow.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Battling Bella

Bella in 1971. Bella Abzug (1920-1998) was New York born and bred; she looked it, sounded it, and acted it. She was born Bella Savitsky in the Bronx, both of her parents Russian Jewish immigrants, her father a kosher butcher. When her father died, Bella, age 13, went against tradition by saying the Mourner's Kaddish for her father, who had no son, perhaps the first of many feminist gestures to come. President of her high school class, she went on to Hunter College and then to Columbia, where she got her degree in law. Practicing labor law in the 1940s, she took to wearing wide-brimmed hats so as not to be taken for a secretary -- not stylish hats, to judge from photographs, but rather plain ones with the wide brim that would become her trademark. Soon she was taking on civil rights cases in the segregated South and advocating liberal and feminist causes. "This woman's place is in the House -- the House of Representatives," she announced in 1970, and in the following decade got herself elected to the House from Manhattan's West Side for three terms.

Bella in 1971. Bella Abzug (1920-1998) was New York born and bred; she looked it, sounded it, and acted it. She was born Bella Savitsky in the Bronx, both of her parents Russian Jewish immigrants, her father a kosher butcher. When her father died, Bella, age 13, went against tradition by saying the Mourner's Kaddish for her father, who had no son, perhaps the first of many feminist gestures to come. President of her high school class, she went on to Hunter College and then to Columbia, where she got her degree in law. Practicing labor law in the 1940s, she took to wearing wide-brimmed hats so as not to be taken for a secretary -- not stylish hats, to judge from photographs, but rather plain ones with the wide brim that would become her trademark. Soon she was taking on civil rights cases in the segregated South and advocating liberal and feminist causes. "This woman's place is in the House -- the House of Representatives," she announced in 1970, and in the following decade got herself elected to the House from Manhattan's West Side for three terms.When Bella hit Washington, the Old Boys' Club was jolted by a rampaging tiger. She was soon known for her hats, her intelligence, her flamboyance, her New York chutzpah. Not to mention her voice, which Norman Mailer said "could boil the fat off a taxicab driver's neck." Assertive, aggressive, not given to compromise, she stepped on many toes. "I spend all day figuring out how to beat the machine," she wrote in a journal, "and knock the crap out of the political power structure." Always an advocate of change, she spoke scathingly of the Congressional club, the seniority system, the log-rolling and back-scratching typical of Congress. She delighted in being one of the first, if not the first, in embracing what seemed to be radical causes: Nixon's impeachment (she was on his enemies list), getting out of Vietnam, women's rights (she was a friend of Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan), gay rights, national health insurance, laws against employment discrimination. Ralph Nader said that her sponsorship of a measure often cost it 20 to 30 votes. And Jimmy Breslin told how during a quarrel over scheduling she punched one of her campaign workers, then phoned him the next day to apologize; "How's your kidney?" she asked. Even so, in a survey her colleagues named her the third most influential member of the House. And if she made enemies, she also made friends. Said her lifelong friend Gloria Steinem, "She's fierce and intense and funny. She takes everyone seriously.... And she's willing to change her mind."

Bella with Mayor Ed Koch (left) and President Jimmy Carter, 1978. I never encountered Bella face to face, but my partner Bob once, quite by chance, heard her giving a campaign speech to a crowd of several hundred in Sheridan Square from a platform mounted on the back of a pickup truck. Far from flamboyant, she was level-headed and talked sense, but with warmth; the spectators applauded with enthusiasm. So impressed was Bob that he registered for the first time ever, so he could vote for her in the mayoral election. Alas, she lost in the primary to Ed Koch.

Bella with Mayor Ed Koch (left) and President Jimmy Carter, 1978. I never encountered Bella face to face, but my partner Bob once, quite by chance, heard her giving a campaign speech to a crowd of several hundred in Sheridan Square from a platform mounted on the back of a pickup truck. Far from flamboyant, she was level-headed and talked sense, but with warmth; the spectators applauded with enthusiasm. So impressed was Bob that he registered for the first time ever, so he could vote for her in the mayoral election. Alas, she lost in the primary to Ed Koch.On weekends Bella returned to her residence on Bank Street in Greenwich Village to spend time with her husband, Martin Abzug, whom she had married in 1944. A stockbroker and author, he had little interest in politics but stuck by her through thick and thin; she called him her best friend and supporter. They had two daughters.

In the long run her abrasive manner hurt her career. She ran for the Senate in 1976 and lost narrowly in the primary, then ran for mayor in 1977 and lost in the primary to Ed Koch. Other defeats followed, but she continued to practice law and worked tirelessly for women's causes. It's not surprising that she failed to accomplish many of her goals in Congress; she was too blunt, too unsubtle, too fierce.

"I've been described as a tough and noisy woman, a prizefighter, a man hater, you name it," she wrote in a journal that was published in 1972 as Bella. "But whatever I am -- and this ought to be made very clear at the outset -- I am a very serious woman." That she was. If one is out of the reach of her abrasiveness, one can't help but like her. Certainly I can't.

In her later years Bella kept up her busy schedule of work, even though she traveled in a wheelchair. She died in 1998 from complications following open heart surgery. She has been inducted into the Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York, the site of the first Women's Rights Convention in 1848.

The Queen of Mean

This photo has been cropped; see below.

This photo has been cropped; see below.

Leona Helmsley (1920-2007) was born Leona Mindy Rosenthal in Marbletown, New York, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Poland, her father a hatmaker. She grew up in Brooklyn and dropped out of college allegedly to become a model, though her modeling career remains unsubstantiated. Certainly she had business skills and an outsized ambition. In time she joined a New York real estate firm and became a condominium broker, finally working for real estate mogul Harry Helmsley. She was already a millionaire and twice divorced when, in 1972, she married Helmsley, who divorced his wife of many years to marry her. From then on she worked with him to build a real estate empire that included the Tudor City apartment complex on the East Side of Manhattan, the Empire State Building, the Helmsley Palace Hotel on Madison Avenue, and many other hotels in New York City, Florida, and elsewhere.

The Helmsley Palace Hotel, now the New York Palace Hotel, on Madison

The Helmsley Palace Hotel, now the New York Palace Hotel, on Madison Avenue. In the foreground is the Villard Mansion, built by railroad magnate

Henry Villard in 1884. Behind it is the 55-story tower built by Harry

Helmsley. The hotel combines the two.Americasroof

A lackluster millionaire before the marriage, Helmsley's life was sparked up afterward. He and Leona moved into a ten-room duplex with an indoor swimming pool atop their luxurious Park Lane Hotel on Central Park South, but soon also acquired an estate in Connecticut, a condo in Palm Beach, and a mountaintop hideaway near Phoenix, not to mention a private hundred-seat jet with a bedroom suite so they could gad about in comfort. Leona is said to have had a minimum of twelve pictures of herself in every room of her residences. She gave lavish birthday parties for her husband ("my pussy cat, my snooky, wooky, dooky"), and on her own birthday her snooky floodlit the Empire State Building with her favorite colors at a cost of $100,000 ("Less than a necklace," said the pussy cat). As F. Scott Fitzgerald famously remarked, "The rich are different from you and me."

I recall lavish ads for the Palace Hotel showing her, dressed in the height of fashion and crowned with a tiara, inspecting her troops, the hotel's uniformed employees, with the caption "The Queen stands guard." Indeed she did, being a demanding and tyrannical monarch. A friend of mine was once interviewed for a job with her as chef, and was warned by the interviewer that he would have to be available 24/7, in case Mrs. Helmsley planned a dinner for seventeen at 2 a.m.; he didn't get the job because "your personality would not meld well with Mrs. Helmsley's." When she took her early morning sessions in her swimming pool, a more compatible liveried servant was on hand with a platter of fresh-cooked shrimps; at the end of each lap she would command, "Feed Mama," and he would hand her a shrimp. But her anger was fierce. Discovering a wrinkled bedspread, she shouted, "The maid's a slob! Get her out of here. Out! Out!" And a lawyer friend who once breakfasted with her has told how, when a hotel waiter brought him a cup of tea with a tiny bit of water spilled in the saucer, she grabbed the cup from him, smashed it on the floor, and made him get down on his hands and knees to beg for his job. No wonder she came to be known as the Queen of Mean.

The uncropped photo, her mug shot upon

The uncropped photo, her mug shot uponher arrest in 1988. The most radiant mug

shot I've ever seen. After her conviction

she looked less radiant. All this changed in 1988, when U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani (the future mayor) brought charges against the Helmsleys for evading federal taxes by illegally billing the expenses of remodeling their new mansion in Connecticut to their hotels as business expenses. Harry Helmsley's deteriorating health led to a court ruling that he was mentally and physically unfit to stand trial, so Leona faced the charges alone. At the trial her arrogance and greed were amply demonstrated, and a former housekeeper testified that she had once told her, "We don't pay taxes. Only the little people pay taxes." She denied having said it, but it was consistent with her character. When I heard that statement, I knew that the IRS would nail her, and sure enough, in August 1989 she was convicted on numerous charges that included conspiracy, mail fraud, and tax evasion. While she sobbed quietly in the courtroom, her lawyer pleaded with the judge not to make her serve time in prison, which might endanger her health. The judge was adamant, but her attorney was able to get a reduced sentence, and she was ordered to report to prison on the day federal taxes are due, April 15, 1992. She was released on January 26, 1994, with 750 hours of community service to perform.

Was she sobered by her time in prison? Had she changed? She had always insisted that she had done no wrong, that she was targeted because she was a woman. Assigned to a hospital in Arizona to do community service, she was required to stuff envelopes and wrap presents for volunteers to give to the patients. There she complained that the staff "gawked at her" and were "less than charitable," so the court permitted her to do the service at home. But the judge soon learned that she had assigned much of it to her servants and so added another 150 hours of service.

As a convicted felon Leona Helmsley couldn't run enterprises with liquor licenses, so she had to give up managing the hotels. When her husband died in 1997, she said, "My fairy tale life is over. I lived a magical life with Harry." Estranged from her grandchildren and with few friends, she lived alone in her lavish apartment atop the Park Lane Hotel with her Maltese dog, Trouble. Her face was now frozen into a scowl by multiple face lifts. When she died of heart failure in 2007, she left the bulk of her fortune to a charitable trust, and $12 million to Trouble, this last being ranked third in Fortune's "101 Dumbest Moments in Business"; the bequest was later reduced by a court to $2 million. She and Harry are buried in a luxurious Greek-style mausoleum with stained-glass windows in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Westchester County. Trouble, the richest dog in the world, died in December 2010, her every need seen to around the clock, and watched over by a full-time security guard because of death and kidnapping threats. Her keeper had spent $100,000 a year on her care.

The Helmsley Mausoleum in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

The Helmsley Mausoleum in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.Did Bella and Leona ever meet? Not to my knowledge. If they had, it would have been epic. I can't imagine them hitting it off. The Queen of Chutzpah vs. the Queen of Mean -- how the fur would have flown!

Coming soon: Next Sunday, Who makes money when America goes to war? New York, 1861-1865 (with glances at today). Next Wednesday, Colorful New Yorkers: Diamond Jim and Texas Guinan, but with Jim's pal Lillian ("Luscious Lillian") Russell and her famous hour-glass figure thrown in. In the works: the Titan of the Met, who claimed to have a heart of stone, and an aristocrat of the people who, like Dolly Levi in The Matchmaker, believed that money should be spread around like manure in order to make things grow.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on August 21, 2013 05:07

August 18, 2013

80. Famous New York Streets: Broadway

Broadway, the most famous street in New York City, running fifteen miles through Manhattan and the Bronx, was once an Indian trail and then, with the coming of the Dutch, the main thoroughfare in the settlement of New Amsterdam. The Dutch named it the Heere Straat (the Gentlemen's Street or High Street) or Breede Weg, and when the English took over, they translated the latter as "Broadway." It still runs the length of Manhattan crazily at an angle, defying the gridlock pattern of the city's streets decreed by the city fathers in 1811.

In New Amsterdam the Heere Straat went from the fort that gives the Battery its name up to a gate in the wall that gives Wall Street its name. Right from the first, it teemed with a mix of peoples: Dutch, English (including refugees from the rigors of Puritan New England), Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Frenchmen, Bavarians, Poles, Italians, Walloons, Bohemians, Jews, Africans both slave and free, and Munsees, Montauks, and Mohawks, most of them coming in hopes of a freer, fuller life. One visitor reported eighteen different languages in the settlement, and they would all have been heard on Broadway.

New Amsterdam in 1660. The Heere Straat is clearly shown, as is the fort at the Battery.

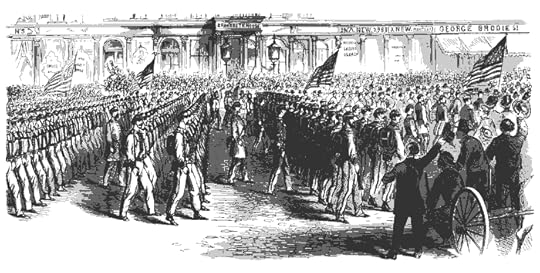

New Amsterdam in 1660. The Heere Straat is clearly shown, as is the fort at the Battery.In the eighteenth century Broadway witnessed one of the most significant events in our history: Washington's triumphal entry into the city on November 25, 1783, following the evacuation of the last British troops and, with them, some 28,000 Loyalist refugees and many former slaves whom the British had liberated. The city was the scene of Washington's worst defeat in 1776, following which it had been occupied by the British. Washington and his officers entered from the north and proceeded down Broadway to the Battery, to the cheers and applause and waving hats and handkerchiefs of onlookers. Though ticker tape was absent, it could be considered the first of many parades of heroes on Broadway. For years afterward, November 25 was celebrated as Evacuation Day.

An 1879 lithograph of Washington's entry.

An 1879 lithograph of Washington's entry.Now we'll fast-forward to the nineteenth century, the period I know best. The city of circa 1830 was still small enough that the gentry knew, or knew of, almost everyone who mattered; for all its ongoing changes, their world was ordered and safe. Few people kept carriages, and those who did were known to everyone. One of these was Dandy Marx, a dashing young blade whose clothing defied the somber colors of the day as he drove four handsome chestnuts down Broadway, bearing with perfect nonchalance the sneers and jealousies of others. Another familiar sight was Dandy Cox, a mulatto driving a spirited horse to a light wagon where he sat perched high on his seat, his well-brushed beaver cocked at an angle, his green jockey coat displaying polished brass buttons, his leather gloves spotless, imitating -- if not mocking -- the fashionables of the day.

But in those days almost all the men worked, so that the fashionable promenade of Broadway, which went from the Battery to Canal Street, was mostly given over to belles and their mamas for shopping. One of the few male interlopers was Gentleman George, a neat, trim, tastefully dressed young man who drove a stately gray with aplomb. Where does his money come from? the men of the town wondered, while mothers eyed him with suspicion, well aware that their daughters were casting furtive glances his way, intrigued by this timid but respectful young man whom they so often met on their morning strolls. Gossip about him saved many a tea party from dullness. George was seen and puzzled over for years, until at last he disappeared into the city's rapid growth and expansion, a mystery to the end.

Broadway and Canal Street, 1834. Busy, but not jammed.

Broadway and Canal Street, 1834. Busy, but not jammed.The sidewalks of Broadway also offered a few eccentrics who stood out and occasioned comment. The mad poet McDonald Clarke was seen there in a tattered cloak, his unbuttoned "Byronic" shirt collar a sharp contrast to the primly buttoned shirts of most males, his melancholy gaze always fixed on the pavement, another mystery figure whom women found strangely appealing. Also familiar was the Gingerbread Man, a harmless lunatic in a swallowtail coat who jog-trotted up and down the avenue as if on a pressing errand, his only sustenance a seemingly endless supply of gingerbread stuffed in his pockets that he was constantly consuming. One day he failed to appear, was never seen again. Another regular on Broadway was the Lime-Kiln Man, a tall, gaunt figure, his unkempt hair and thin face smeared with lime, who took no notice of the looks of pity he garnered, another mystery man about whom nothing was known. In time he was found dead in a lime kiln where he had slept at night for years.

The society of those days, though quite conformist, tolerated a number of oddballs because they were familiar and posed no threat. What people were leery of was the blatant display of wealth, which was deemed vulgar. Elegance was allowed, and the women of New York were famous for dressing in the height of fashion, and even the black underclass could be surprisingly chic, but the elegance had to be quiet and discreet. All this was visible on Broadway.

Broadway, 1860. Now we'll fast-forward again to the 1860s, by which time everything had changed. Irish and German immigrants had flooded in since the 1840s, the city had become a metropolis, Wall Street was now the money center of the nation, the Civil War had permitted gold speculators and war contractors to amass a fortune, and New Money was blatantly in evidence everywhere. Ever since Central Park had opened in 1859, its Drive had become the preferred promenade of the affluent, who drove there in elegant equipages, so that Broadway was now essentially commercial.

Broadway, 1860. Now we'll fast-forward again to the 1860s, by which time everything had changed. Irish and German immigrants had flooded in since the 1840s, the city had become a metropolis, Wall Street was now the money center of the nation, the Civil War had permitted gold speculators and war contractors to amass a fortune, and New Money was blatantly in evidence everywhere. Ever since Central Park had opened in 1859, its Drive had become the preferred promenade of the affluent, who drove there in elegant equipages, so that Broadway was now essentially commercial.And what did one see on Broadway? Red and yellow and blue-painted stages, open and closed carriages with liveried footmen, drays, wheelbarrows, hacks, milk carts with clattering cans, horsemen, lager beer wagons, express trucks stacked high with boxes labeled ASTOR HOUSE or ST. NICHOLAS HOTEL, and a wagon hauled by six straining horses conveying the towering bulk of a safe as big as a house. And all this traffic emitted a deafening roar, as it sliced through the mud of the street, until it jammed up amid shouts, curses, and whinnyings, and maybe the shriek of a coachman being beaten by a truckman for not giving way. With no stoplights or stop signs, how was a pedestrian to get from one side of Broadway to the other? Without the help of a policeman, you were risking your life. Furthermore, in wet weather the thoroughfare was ankle-deep in mire, while in dry weather it was caked with teeth-gritting, breath-choking dust. And always, in whatever weather, being embellished with garbage and manure, it stank.

What enterprises did this tumultuous thoroughfare offer? Barbershops, liquor stores, lottery offices, daguerreotype galleries, artificial teeth manufacturers, sewing machine and piano forte showrooms, plain and fancy jewelers, oyster cellars, clam chowder shops, bookstores, boots and shoes, billiard table stores, ice cream parlors, gambling dens. But there were also princely hair-dressing establishments for gentlemen, emitting whiffs of menthol, musk, and cologne; fancy dry-goods stores with uniformed doormen; palatial marble-fronted hotels; and, guaranteed to astonish visitors from the provinces, sidewalk displays of patent sarcophagi in rosewood, mahogany, and iron, satin-lined with silver mountings, featuring glass-paneled lids to display the face of the deceased. Then as now, in New York one could obtain anything and everything.

Pigs rooting in garbage on the side streets sometimes joined the throngs along Broadway where, in the morning rush to work, purposeful top-hatted merchants in starched collars rubbed elbows with dusty sideburned laborers, pallid clerks, and ginghamed working girls, while ragged newsboys hawked their papers, and workmen loaded or unloaded carts and toted boxes. Later, hordes of elegant lady shoppers would appear, as well as gangs of barefoot boys and girls mouthing obscenities, and sandwich men flaunting fore and aft in bold lettering RADICAL CURE TRUSSES, POCAHONTAS BITTERS, or PHILIPOT'S INFALLIBLE EXTRACT. For everyone went to Broadway, rich and poor, respectable and otherwise; it was the principle thoroughfare, the main artery, the commercial hub of New York.

On Broadway the kings of the road were the whip-cracking stage drivers who, mounted high on the box of their stages, drove as fast as traffic permitted, shaving lampposts and shrieking oaths at anyone or anything in the way. Their patrons grumbled about the ill-ventilated interiors with twin unpadded benches, where up to a dozen passengers sat facing one another amid smells of onion, sweat, and tobacco, as the stages lurched ungently ahead over cobblestones. Passengers were expected to drop the exact fare in a box with a slit in the top, which the driver, glancing down from his seat, could verify, and God help anyone who failed to pay, since the resulting comments from the driver would be, to put it mildly, scathing. A champion of the drivers was Walt Whitman, who, seated beside them, often rode the whole length of Broadway listening to their yarns. He described them as "largely animal -- eating, drinking, women," but esteemed their comradeship, good will, and honor, and credited Broadway Jack, Balky Bill, Pop Rice, Patsy Dee, and a host of others with influencing the gestation of Leaves of Grass.

But what did the old timers think of all this? Remembering the tranquil days of their childhood, they were dazed. The jam of people and vehicles on Broadway overwhelmed them, and if they stood at an entrance to Central Park and watched the showy equipages heading for the Drive, they had no idea who these promenaders were or where their money came from. Gone was the discretion of an earlier time; New Money paraded its wealth brazenly. Engulfed by this mass of strangers, these relics of a simpler age felt small, mere atoms lost in the city's never-ending flux.

Change, often radical, was the rule in the Never-Finished City. By the mid-1870s buildings were rising to eight, ten, and eleven stories high, provoking mixed reviews: a new dimension to space, said some; top-heavy horrors and "Towers of Babel," said others. Broadway had been the first New York City thoroughfare to get gaslight in the mid-1820s, and now it was the first to be lit with electricity. On December 20, 1880, the whole stretch of it from 14th Street to 26th Street was suddenly bathed in brilliant light; observers gaped and raved. And in 1879 the first telephone exchange opened, with the first phone directory listing all of 252 names. Businesses rushed to adopt the new gadget, but at first it was much too costly for use in private homes.

Broadway in 1885, looking north from Cortlandt and Maiden Lane,

Broadway in 1885, looking north from Cortlandt and Maiden Lane, with wires crisscrossing overhead.

Telephone and telegraph wires now crossed and recrossed each other from the tops of buildings, darkening the sky over Broadway with what seemed like meshes of a net. Worse still, overburdened wires had a way of snapping and falling to the street, with potential peril to anyone in the vicinity. Then in 1889 a lineman working overhead was electrocuted on a wire gridiron in the heart of the business district; thousands watched as the body dangled for nearly an hour, its mouth spitting blue flame. The enraged public now demanded that the wires be put underground, and the corporations involved finally, after long delays, complied.

The advent of the automobile in the 1890s marked another major change for Broadway. The first recorded motor vehicle fatality in the United States, and indeed in all the Americas, occurred in New York, though not on Broadway. On September 13, 1899, Henry H. Bliss, a New York real estate salesman, was getting off a streetcar at West 74th Street and Central Park West, when an electric-powered taxi struck him and inflicted fatal injuries; he died the next day. A plaque commemorating the incident was placed at the site on the centennial of his death, a mortality that can be seen as ushering in the twentieth century. The first traffic light was not installed in New York but in London in 1868, but in 1916 New York installed the first three-color stoplight at its busiest intersection, Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. That the location chosen was not Broadway shows that by now Broadway was not the single most significant thoroughfare in the city.

By the early twentieth century it was electricity that gave the midtown section of Broadway, the section from 42nd to 53rd Street also known as the Theater District, the name "The Great White Way." The streetlights alone justified it, but the advent of neon signs in Times Square confirmed it. This is still the Theater District, though most of the theaters are on side streets nearby, and Times Square today, especially at night, is more astonishing than ever. (Forty-second Street, by the way, merits its own history; once a tawdry porn center frequented by drag queens and hustlers, it has been scrubbed up and Disneyfied, a change that is praised by some and lamented by others.)

Jorge Láscar

Jorge LáscarBroadway today on the Upper West Side is a wide avenue with a thin strip of park down the middle. Back in my student days I loved walking down from Columbia to some restaurant or movie theater on Broadway, and traipsing it at night always lifted my spirits. This stretch of Broadway was not constricted by tall buildings as it was downtown; it was big, open, and free -- New York at its best.

I have omitted many sections of Broadway -- Madison and Herald Square, Columbus Circle, Lincoln Center -- but if I include them, this post will become a history of the city. So I'll sign off now, acknowledging that Broadway, no longer the single jammed artery of the city, is still a vital part of it, a symbol of it, busy, colorful, exciting.

Coming soon: Next Wednesday, the first of a series on colorful New Yorkers: Battling Bella and the Queen of Mean. Older New Yorkers may pick up on these designations; younger ones and out-of-towners may not. But they are very New York, very colorful, and well worth a look. Next Sunday, Who makes money when America goes to war? (1861-65, with a glance at today, including a delicious photo of Dick Cheney). Also: the Mad Poet of Broadway and the Mephistopheles of Wall Street; Diamond Jim (who owned a mere 12,000 diamonds), and his pal Lillian ("Luscious Lillian") Russell. Why "luscious? Wait till you see her posing on her bicycle! Also: Texas ("Hiya, suckers!") Guinan, who after a night in the slammer remarked, "I like your cute little jail, and I don't know when my jewels have seemed so safe." Also the Broadway gossip columnist who imposed a reign of terror (can you guess?). And maybe I'll set foot -- just a little way -- into the hallowed precincts of the Stork Club. New York is inexhaustible.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on August 18, 2013 04:49

August 14, 2013

79. Tweed at the End: "I have tried to do some good."

At the elections of November 1871 the enraged reformers triumphed over Tammany, with one exception: William Marcy Tweed was reelected state senator.

At the elections of November 1871 the enraged reformers triumphed over Tammany, with one exception: William Marcy Tweed was reelected state senator.The Boss had already been arrested in a civil suit to recover stolen money, but had provided bail at once, with one million coming from Jay Gould, and so avoided jail. The Committee of Seventy, strengthened by its victory at the polls, then sought indictments of all those implicated in the courthouse and other graft, prompting an impromptu flight of Tammany stalwarts and cronies in all directions out of the city of New York. James Ingersoll, the millionaire furniture maker, and James Sweeny, the brother of the Squire, were reported to be refugees in Paris. Andrew Garvey, Grand Marshal of Tammany Hall now also known as the prince of plasterers, was spotted on a ship bound for Germany, where the prince mistook a pilot coming on board for a policeman and, like a true son of Tammany, tried to bribe him, whereupon the indignant pilot threw the money overboard to the laughter and applause of onlookers.

Other targets of investigation announced a sudden and intense need of vacation and vanished. State Senator Henry Genet, known to many as Prince Hal, was so indiscreet as to remain within reach of the law, and was tried and convicted of fraud. But old friendships survive the vicissitudes of politics. Sheriff Matt Brennan delayed turning him over to the Tombs, and one Sunday Prince Hal and his custodian, a deputy sheriff, observed the Sabbath by roaming the city's bars and getting drunk. Ordered to appear in court the next day with his prisoner, Brennan came alone, explaining that he had allowed Genet time to go home and arrange his affairs, which evidently required extensive traveling. The result: Brennan got thirty days in jail and Genet a protracted vacation in Europe. Peter Barr Sweeny, the Squire, left for the wintry clime of Canada to seek his health, later joining his brother in Paris, and the well-named Slippery Dick Connolly was tried and convicted, albeit in absentia, since he had fled abroad with six million dollars to finance his international wanderings.

Two prime targets of the reformers remained. Mayor A. Oakey Hall ("O. K. Haul" in the Nast cartoons) stayed to face charges, and in the three ensuing trials the supposed popinjay, rendered ridiculous in the Nast cartoons with his beribboned pince-nez perched on his nose, proved to be an effective defense attorney for himself, gay, witty, and charming, then caustic or tearfully melancholy, and always the soul of innocence. Yes, he had signed some 39,257 vouchers as mayor, but, having "an ineradicable aversion to details," had had neither time nor inclination to read them all and was unaware of any impropriety. One trial ended with the death of a juror, another with a hung jury, and the third and last with an acquittal. But the Elegant Oakey was not done yet; triumphant, he wrote a play about a man accused of stealing that was done on Broadway with none other than the ex-mayor himself in the lead.

Also on hand, standing his ground "like a Roman," as his lawyer asserted, was William Marcy Tweed, who had aged considerably. At his first trial in January 1873 he was defended by a brilliant team of lawyers, and the jury disagreed. Friends advised him to decamp, but he refused to, confident that he would be acquitted. At his second trial in November 1873 the jury did indeed find him guilty of no less than 204 counts in the indictment. Sentenced to twelve years in prison and a fine of $12,750, he was sent to the county penitentiary on Blackwell's Island, but the court of appeals reduced the sentence to a year and a fine of $250. Released in January 1875, he was immediately arrested on a civil action brought by the state to recover $6 million of the Ring's alleged theft, with bail at the unheard-of amount of $3 million, and when he failed to provide this amount, he was sent again to prison. The reformers, led by the ambitious Samuel J. Tilden, the state's newly elected governor, were determined to make an example of him.

But Tweed still had friends in high places. Confined to Ludlow Street Jail, most of whose inmates were debtors imprisoned by their creditors, he took frequent afternoon rides in a carriage accompanied by two turnkeys, and on the way back stopped off at his home for dinner. On December 4, 1875, while the two turnkeys sat in the parlor, he snuck out the back door of his home and disappeared. Immediately a reward of $10,000 was offered for his capture, and over the next few weeks he was reported to be in Savannah, Dallas, Havana, London, and elsewhere. Just who helped him escape and where he lay in hiding he never disclosed; he was probably hiding nearby in New Jersey. Soon, shorn of his beard and wearing a wig, he made his way by boat to Santiago, Cuba, and from there to Vigo, Spain, where the former state senator and Grand Sachem of Tammany arrived disguised as a common sailor busy scrubbing a deck. Alerted to be on the watch for him, the Spanish authorities identified him with the aid of a Nast cartoon and, unable to read English and thinking him a kidnapper, arrested him and with great pomp handed him over to the crew of an American frigate dispatched specially to take him into custody.

A broken man in failing health, the ex-boss wanted only to die peacefully at home, and hoping to obtain this offered the authorities the only thing still his to give: an elaborate confession, backed up by canceled checks. But Governor Tilden had no interest in prosecuting the many others involved in Tammany fraud, some of them judges, legislators, and upstate mayors; he wanted only to scapegoat Tweed. Attorney General Charles S. Fairchild interviewed Tweed in his Ludlow Street Jail quarters and promised him his freedom in exchange for testimony against Peter Sweeny, who had returned from France in hopes of avoiding prison by arranging a settlement with the authorities.

Months passed with no further word from the authorities; in time it became clear that Fairchild would not approve his release. Tweed suffered several heart attacks, and Luke Grant, his black servant, never left his side at night, sleeping on the floor by his bed. Sometimes, unaware that the Boss was reading his Bible, Luke would burst into song and provoke from Tweed an outburst of profanity. But then Tweed quickly made amends. Learning that Luke was in love, he dictated Luke's letters to the girl, using the fanciest words he could think of; the girl was mightily impressed.

Visitors came daily, found Tweed comfortably lodged in a two-room suite with blooming plants on the window sills, and a table with several books, including an open Bible, but the windows had steel bars. Tweed's memory for faces was unimpaired; staring out a window at people passing in the street, he could name almost all of them, state their occupation, and say something about their family.

Slowly he declined, complaining of more pain in his heart; obviously the end was near. When his heart pained him, Luke pillowed his master on his own breast and massaged his heart to relieve the pain. A married daughter and her husband, the deputy warden, and a few loyal friends came; other family members were abroad. Luke was in tears. "I have tried to do some good," said the dying man, "if I have not had good luck. I am not afraid to die." When his breathing became labored, with great effort he gasped, "Tilden and Fairchild -- they will be satisfied now." He closed his eyes, the room was oppressively silent. Suddenly the great bell in the nearby Essex Market tower pealed high noon like a thunderclap, and he was gone. Luke was on his knees, clasping his master's lifeless hands and sobbing.

The funeral was held at his daughter's house; only one politician of note attended. But a throng of poor people gathered outside in the street, remembering his generosity, a job of some sort, a fiver when they were in desperate need, a load of coal to see them through the winter. After the service they were invited in to view the coffin: men in rough clothing, women in calico with market baskets, several blacks, several men with dogs; they were quiet, respectful, orderly, as they took a last look at the Boss, his hair and whiskers snow-white, his face like chiseled marble. Many accompanied the cortege all the way to Greenwood in Brooklyn, where he was buried beside his mother. Though he looked much older, he was only fifty-five.

For a fair appraisal of Tweed and Hall, one has to shake off the image of the Nast cartoons, which is easier said than done. Some of the reformers in later years decided that Hall may well have been guilty only of negligence, nothing more. As for Tweed, whatever his faults were, his ending can only inspire sympathy. He was being used by the powers that be for their own purposes, and in so doing they failed to honor their promise to him. (He himself had always kept his word.) Whether his confession was reliable, or perhaps exaggerated so as to curry favor with them, can be debated. Whether there even was a tight-knit "Ring" of four -- Tweed, Hall, Sweeny, and Connolly -- has been questioned, though the fact of colossal graft seems undeniable. Tweed had been a superb politician; it is a shame that he didn't use his talents more constructively. But Samuel Tilden played his hand well, becoming first governor and then, in 1876, the Democratic candidate for the presidency, winning the majority of the popular vote but finally losing to Rutherford B. Hayes in the electoral college (a mysterious institution that most citizens don't understand, and that some are even sublimely unaware of).

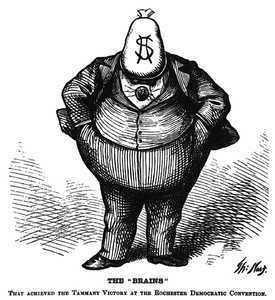

A self-caricature of Nast, sharpening his pencil to

A self-caricature of Nast, sharpening his pencil todraw a cartoon.

Thomas Nast has been hailed as the most successful political cartoonist in our history. Besides helping the Times bring down Tweed and his cronies, he is credited with popularizing the Democratic donkey and Republican elephant, and Santa Claus as the jolly, plump, red-faced figure that we conceive of today. A German-born immigrant, he had all the virtues and vices of the WASP, portrayed the Irish as monkey-faced animals or drunken thugs, and Roman Catholicism as a dangerous subversive force trying to gain control of our youth. But contrary to some accounts, the word "nasty" does not derive from his name; "nasty" was around long before he was.

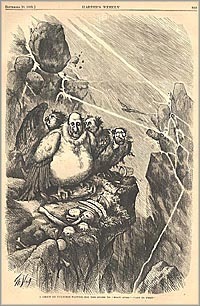

"The usual Irish way of doing things," a Harper's

"The usual Irish way of doing things," a Harper's Weekly cartoon of 1871 by Nast.

"The American River Ganges," a Harper's Weekly cartoon of 1875 by Nast, showing Catholic

"The American River Ganges," a Harper's Weekly cartoon of 1875 by Nast, showing Catholicbishops as crocodiles. In the distant background, Saint Peter's basilica topped by a cross, and

closer, in the center, a public school with the U.S. flag flying upside down, a signal of distress. One Tammany figure who did succumb to the reformers was Justice George G. Barnard, whose propensity for diamonds, cards, brandy, frilled shirts, and profanity was proverbial, and who presided over his courtroom with his boots propped up on the desk before him, while whittling away at pine sticks that the attendants kept him supplied with. In 1872 he was impeached by the New York State Assembly on charges of unjudicial conduct, including fraud and corruption, and was removed from the bench and barred from holding any public office in the state. After that he was rarely seen in public, but to friends in private he expressed his bitter grief. He died in 1879 at the age of forty-nine.

It would be encouraging to say that the reformers, having destroyed Tweed and his alleged "Ring," put an end to corruption in New York, but such was not the case. In the words of George Washington Plunkitt, a Tammany stalwart of a later date, reformers were "mornin' glories -- looked lovely in the mornin' and withered up in a short time, while the regular machines went on flourishin' forever, like fine old oaks." Tammany Hall withstood many onslaughts by reformers, always survived, and dominated New York City politics well into the twentieth century.

Plunkitt, in a shiny top hat, seated at his preferred rostrum,

Plunkitt, in a shiny top hat, seated at his preferred rostrum,the bootblack stand outside the County Courthouse. (Yes,

that courthouse, known today as the Tweed Courthouse.)

And who was George Washington Plunkitt (1842-1924)? you may well ask. He was a veteran Tammany politician who served at various times in both houses of the state legislature, but who today is best remembered for his impromptu talks on politics delivered from the bootblack stand of the New York County Courthouse, expressing candidly the views of a machine politician who thought the civil service system heralded the downfall of the U.S. government. Needless to say, he believed in patronage and spoils, saw no need for reform.

Some of his sayings are memorable:

Everybody is talkin' these days about Tammany men growin' rich on graft, but nobody thinks of drawin' the distinction between honest graft and dishonest graft. There's all the difference in the world between the two.There's an honest graft, and I'm an example of how it works. I might sum up the whole thing by sayin', "I seen my opportunities and I took 'em."This city is ruled entirely by the hayseed legislators at Albany.There's only one way to hold a district; you must study human nature and act accordin'.The Irish was born to rule, and they're the honestest people in the world.You hear a lot of talk about the Tammany district leaders bein' illiterate men. If illiterate means havin' common sense, we plead guilty.Make the poorest man in your district feel that he is your equal, or even a bit superior to you. Above all, avoid a dress-suit.Tammany's the most patriotic organization on earth, not withstandin' the fact that the civil service law is sappin' the foundations of patriotism all over the country. Nobody pays any attention to the Fourth any longer except Tammany and the small boy.

As an "honest" grafter, he made a fortune by buying up land that he knew would be needed for public projects. His world was small -- even Brooklyn was terra incognita for him -- but he did know the world of Manhattan politics and is a must-read for anyone interested in Tammany and its ways. His talks were recorded in William L. Riordon's Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, first published in 1905 but available in more recent editions.

Today the Tweed courthouse, the focus of so much graft, serves as the headquarters of the Department of Education. Once disparaged as a colossal boondoggle costing more than the purchase of Alaska, it has been carefully restored and is now recognized as a landmark of note. A striking example of Victorian neoclassical style, to my eye it is downright handsome.

The Tweed Courthouse on Chambers Street today. The rotunda is not visible in this photo. The huge building in the left background is the Municipal Building.

The Tweed Courthouse on Chambers Street today. The rotunda is not visible in this photo. The huge building in the left background is the Municipal Building. Interior of the octagonal rotunda.

Interior of the octagonal rotunda. Staircase, west wing.

Staircase, west wing.Note on WBAI: It's not quite as bad as I thought. The national and international news, coming from a different source, continues, and they have brought back the English-language news of Al Jazeera. But the city-based local news is gone, and that's serious enough.

Coming soon: Next Sunday, Famous New York Streets: Broadway. The first of a series of posts on streets; other possibilities being Wall Street, Fifth Avenue (and its poor cousin, Sixth), and the Bowery. And more posts on colorful New Yorkers: Texas Guinan, the Queen of Mean, the Mad Poet of Broadway, the King of Gossip (can you guess?), and others. And war profiteering, then and now.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on August 14, 2013 04:18

August 11, 2013

78. The Hercules of Parks

The Verrazano Bridge, its graceful span linking Brooklyn and Staten Island ...

Roger Wollstadt

Roger Wollstadt... Lincoln Center, that amazing complex of cultural institutions, its structures and fountain coming magically alive at night ...

Nils Olander

Nils Olander... the United Nations Headquarters, looming dramatically close by the East River ...

Ad Meskens

Ad Meskens R.Sullivan

R.Sullivan... Jones Beach on the south shore of Long Island, with its broad expanse of sand and elegant bathhouses, accessed by a landscaped six-lane parkway with the Jones Beach water tower soaring in the distance ...

... the massive looming structures of Co-op City, the vast housing complex beside the Hutchinson River in the Bronx ...

Sacme

Sacme... and countless other parks, beaches, throughways, housing projects, and playgrounds in and about the city -- all this and more, much more, is the work of one man, said to be the world's greatest builder since the pyramid-building pharaohs of ancient Egypt. And many of his works bear his name.

Moses with a model of his proposed

Moses with a model of his proposed Brooklyn-Battery Bridge. Robert Moses was just a name to me, until I read his biography (see below). Then I realized that his works are all around us, that New York City's character and history are inseparable from the story of Robert Moses, a man whom I have never had any contact with and whom I wouldn't have wanted to know, but a giant in the history of this city.

I have said that all these achievements were the work of one man. This reminds me how Bertolt Brecht, when he encountered a statement like "Caesar conquered Gaul," would comment, "Really? All alone?" Of course Moses had assistants -- a whole army of them -- and allies. But he was the initiator, the innovator, the guiding spirit of these projects, and without him, few of them would ever have been realized.

Robert Moses (1888-1981) pursued his public works projects under six New York State governors and five New York City mayors, all of whom found in him an invaluable ally and a formidable opponent, but one that they could not do without. He more than anyone shaped the city of New York; his achievements are everywhere in the city today, as well as throughout Long Island and in upstate New York. Ambitious, impatient, and arrogant, he gave his life to public works projects, was always burning up with new ideas that he was determined to realize. And early on he learned that dreams, no matter how vast and dazzling, were not enough; one must have power to make them happen. So he learned to acquire power and use it.

Consider a few of his achievements:

In the 1920s, when state parks were unknown throughout most of the country, with Governor Al Smith solidly behind him he created 40,000 acres of state parks on Long Island, linking them by landscaped parkways to the city, thus setting an example for other states to follow.In a mere two years he transformed a desolate sandbar on the south shore of Long Island into the vast sandy expanse of Jones Beach, with elegant bathhouses, a boardwalk, a restaurant, and parking lots accommodating tens of thousands of cars.As Park Commissioner under Mayor La Guardia, using thousands of laborers in one year he refurbished every park in the city, removing litter, painting structures, planting trees -- an accomplishment that astonished the press and the public.In Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx he used landfill to join Hunters Island and Twin Islands to the mainland and transformed skimpy little Orchard Beach into a mile-long crescent with gleaming white ocean sand dredged up off the Rockaway beaches and brought in by barge.He completed the Triborough Bridge, a huge project comprising four separate bridges linking three boroughs and two islands, thus creating the first direct link between the Bronx and Queens, and making Long Island and its parks accessible from the city.As part of his West Side Improvement plan he transformed Riverside Park in Manhattan from a mass of mud and dirt into a lush green park free at last of the New York Central tracks and their smoke-belching engines, which he covered over and so made disappear.As part of that same grandiose plan, he created the West Side Highway, built the Henry Hudson Bridge to carried it over the Harlem River into the Bronx, and continued it north to the city line, linking it up with the Saw Mill River Parkway and so at last giving the city a convenient outlet to the north.He was also responsible for the creation of Lincoln Center, the United Nations Headquarters, Co-op City, Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, and the New York Coliseum, as well as 416 miles of parkways radiating out from the city into the suburbs, and a massive power dam across the Saint Lawrence River.

Is it any wonder that for forty years the press and public idolized him as the Hercules of Parks, a zealous and fearless achiever who sought only the public good, free from any political considerations? And that he himself, immune to modesty, was sure that he would be blessed by future generations, that his works would make him immortal.

How did he do it? How did he cope with governors and mayors and bosses, and even at times with presidents? How could he do anything in a city whose bureaucracy, second in size only to the federal government's, has been described as a huge spongy mass into which good intentions and noble projects sink, never to be seen again?

The answer is: through power, sometimes blunt and naked, sometimes veiled and discreet, but always and unmistakably power. He functioned for years as Park Commissioner, Construction Coordinator, and member of the City Planning Commission. But his greatest power lay in the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, whose board he dominated. An authority is a strange creature not fully understood by the public (myself included). It has powers akin to those of a large private corporation and even, to some extent, the powers of a sovereign state. Unlike a public agency, it needn't show its books to the public, and Moses never did, so no one knew what the authority's revenues were (and they were vast), or how Moses used them.

Essential to Moses' power was the praise of press and public, a mighty weapon to wield against critics and reformers who challenged him; throughout his career he cozied up to newspaper owners, editors, and reporters. But if press and public adored him, it was because he delivered. He drove his architects and engineers hard, pounded his fist on his desk, demanded quick results. Those who couldn't take it quit, but those who remained were fiercely loyal, convinced that this was more than a job, that their work really mattered and would greatly benefit the public. The result: fourteen-hour work days, and when plans for a project were urgently needed, all-night sessions with short naps at intervals on cots that Moses thoughtfully provided. The only one who could drag him home was his wife; if she showed up, he surrendered instantly and ended the day's work. But politicians were soon telling one another, "That Moses fellow, he gets things done!" And nothing so pleases politicians at election time as some new park or highway or bridge that voters can make use of and enjoy.

Discretion was not his thing; in dealing with public officials he was ruthless. Unknown to the public, to get his way he used not only charm, bribes, and legal loopholes and technicalities, but also threats, insults, lies, even character assassination. He once shouted over the phone at Governor Thomas E. Dewey that he was a stupid son of a bitch and hung up. But his greatest weapon of all was the threat to resign; so necessary was he to mayors and governors, they surrendered instantly.

But this was not enough. When the law empowering the Triborough Authority was amended in 1938, Moses snuck into the text hidden clauses that gave him still more power and made it practically impossible for him to be removed. He could now issue bonds, acquire land, retain tolls, and hire and fire unrestricted by civil service regulations. No one realized at first how the amendment had made him practically invincible, but when challenged, he could refer critics to such-and-such a clause, rendering them powerless. Moses was henceforth independent of mayor and governor, city council and legislature alike.

The Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority was now his fiefdom and private empire with its own flag and great seal; its own laws and regulations; a self-contained communications network; a fleet of yachts, cars, and trucks; a uniformed army of bridge and tunnel officers responsible only to him; a steady source of revenue from bridge and tunnel toll booths -- as high as $213 million a year, far more than what was needed to maintain its operations; and hundreds of skilled architects, engineers, contractors, and developers -- "Moses men" -- whom he often made millionaires. Favored secretaries had bigger cars and higher salaries than city commissioners, and round-the-clock chauffeurs so they could be on call twenty-four hours a day.

The monarch presiding over this private empire had no less than four offices, one on Randall's Island in the East River, one in the old August Belmont mansion on Long Island, and two in downtown office buildings. Adjacent to each office was a luxurious dining room where Moses could wine and dine visiting dignitaries lavishly. At Randall's Island invited guests would be ushered into an anteroom whose walls featured photographs of Moses with various presidents; at the Belmont mansion the anteroom's walls were covered with plaques and trophies honoring the host. White-coated waiters served drinks, and a Moses aide would appear to regale the guests with stories of his boss's triumphs. Finally Moses himself would appear, followed by a suite of eight or ten aides. The doors to the dining room would then be thrown open and Moses would lead the guests inside, where the aides would be seated on his right in seats prearranged in order of rank and favor in his eyes. (From week to week, observers could tell who was up, who was down.) As for the quality of the food served, guests spoke of it afterward in tones of awe.

In the Moses empire these lunches were almost routine. But whenever a new dam or park was opened upstate, chartered planes flew hundreds of guests to a whole weekend of lavish celebrations well covered by the press. Such affairs won Moses more praise and respect, but he was taking no chances. He also hired investigators ("bloodhounds") to create files on local officials so as to keep them in line; if lavish entertaining didn't do the trick, blackmail would, and he didn't hesitate to use it. All of which reminds one of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI; Hoover too presided over a private empire through many administrations, kept files on public officials, and used blackmail to get his way. Hoover's operation was more far-reaching, involving national affairs as it did, but in the domain of public works Moses had just as much power and used it just as ruthlessly. But even the Hoover comparison falls short. How about Louis XIV at Versailles?

Al Smith greeting crowds during his ill-fated

Al Smith greeting crowds during his ill-fated1928 campaign for the presidency. The face --

hearty, coarse, open -- shows him to be Moses'

opposite. Al Smith was too wet, too Irish, too

Tammany -- in short, too New York -- to win

a national election. The governor he most admired and felt closest to was Al Smith, his polar opposite. Born in New Haven, Moses grew up in comfortable circumstances, a secular Jew who later converted to Christianity. He was well bred and well educated, a graduate of Yale who did postgraduate work at Oxford. Al Smith was a Tammany man from the streets of New York, an Irish Catholic with little education, harsh-voiced, blunt, uncouth. But both were fighters, and both wanted to accomplish things that would benefit the citizens of New York. So Smith backed Moses completely in his battles with local municipalities and robber baron landowners as he created a vast system of parks and parkways on Long Island in the 1920s. To settle one ongoing dispute about a proposed appropriation by Moses on the south shore, Smith summoned Moses and several landowners to a conference, so he could hear both sides. When one of the landowners explained that they didn't want to be "overrun by rabble from the city," Smith looked at him coldly and replied, "Rabble? That's me you're talking about," and signed the appropriation form on the spot.

The next governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, differed vastly from Smith. A patrician and upstate landowner with an old and honored name, he was smooth, educated, urbane, WASP to the core, subtle, devious, and vindictive. He and Moses disliked each other intensely, but he couldn't remove Moses from his park posts and soon realized that he needed Moses, a man who got things done. So they developed a working relationship that continued when Roosevelt became president.

La Guardia addresses the citizens on the radio.

La Guardia addresses the citizens on the radio.Another prima donna that Moses had to deal with was Fiorello La Guardia, mayor of New York (1934-45) through the bleak Depression years and beyond. Cocky, truculent, impulsive, and ambitious as well, the mayor was not the easiest man to get along with, but he was a champion of the have-nots and of public works, and like Smith and Roosevelt could see that Moses got things done. In private Moses referred to the Little Flower as "Rigoletto," and La Guardia called him "His Grace." Strong-willed and hot-tempered, they tangled often, but they also admired each other and shared the dream of making New York City beautiful. But in time the mayor came to realize -- too late -- that the man he had made Park Commissioner had acquired too much power by far.

Slowly, over time, Moses' accomplishments began to be appraised more critically. He built new parkways on Long Island to relieve congestion on the old ones, but the result was congestion on the new and old parkways alike. The Triborough Bridge was soon clogged with traffic, but the old East River bridges remained congested as well; Moses' proposed solution: build another bridge. But the city planners gradually came to realize that the more facilities you provided for vehicular traffic, the more traffic there would be.

Increasingly, Moses ran rough-shod over the mounting protests of reformers and preservationists. In building the West Side Highway he put it right through Inwood Hill Park, destroying much of the last virgin forest in Manhattan, instead of putting the highway along the edge of it, as the park's defenders urged. In the Bronx his highway destroyed as well a once tranquil residential neighborhood in Riverdale, and cut right through Van Cortlandt Park. I have hiked in both those parks and can testify that it is hard to find a spot in their leafy expanses free of traffic sounds, where one can experience silence with only the faint sounds of nature.

Moses' projects were in fact not meant to benefit all the citizens, but only the affluent middle class with cars. (Which is why many of his achievements are beyond my carless reach.) All the Long Island parks had huge parking lots, but could not be accessed by people without cars, because Moses vetoed a proposed Long Island Railroad spur to Jones Beach, and made sure that the parkway overpasses were just low enough to block passage of city buses. He had no interest in small parks for the slums, and of all the hundreds of playgrounds he built, only one was in Harlem, where playgrounds were most needed. Clearly, he didn't share Al Smith's affection for the "rabble," whom he saw as dirty and unruly. In the name of "slum clearance" he was quite willing to drive thousands out of their homes into overcrowded slums elsewhere or into areas that would soon become slums. He destroyed neighborhoods and flooded the city with cars by building highway after highway, while starving the city's subways and suburban commuter railroads. For every improvement he made, there was a high price to be paid, though that price was often hidden from the public.

Rarely, Hercules was stymied. In 1941 he proposed a Brooklyn-Battery Bridge that would have ravaged Battery Park, one of the few spots in Manhattan affording a fine glimpse of the harbor. Many forces combined to resist the plan, preferring a tunnel, but he would not compromise. Finally his opponents appealed to the Roosevelts, and the President got the War Department to declared a bridge vulnerable to air attack in wartime, which settled the matter; the tunnel was built, and not with him in charge.

This rare defeat enraged him. The Roosevelts were beyond his reach, but he could and did attack the preservationists by suddenly announcing that old Fort Clinton (formerly Castle Garden), a circular sandstone fort at the Battery completed in 1811, and the city Aquarium it housed, were structurally unsound (a dubious assertion) and therefore slated for demolition. Generations of New Yorkers had been taken to the Aquarium as children, and had in turn taken their children there, so the place was enshrined in their memory. The fort was preserved by transferring it to the federal government, but the Aquarium was indeed demolished: an act of pure spite. Only in 1957 would the city get another Aquarium, a fine installation that my partner Bob and I have visited many times, but located in distant Coney Island, so that those without cars could only reach it by a long subway ride through Brooklyn. I mean no disparagement of Brooklyn, but it's quite a journey -- the main sight I recall being the stellar beauty of the Gowanus Canal -- in order to witness walruses and seals.

Fort Clinton and, within its walls, the old Aquarium.

Fort Clinton and, within its walls, the old Aquarium.On the right, a fire boat.

Another fight developed in April of 1956, when a mother sitting on a bench in a tranquil glen just inside Central Park between West 67th and 68th Streets noticed some men nearby with surveying equipment and blueprints. Leaving for lunch, the men left their blueprints spread out on the ground, and the mother, stooping to look at them, saw their title: "Detail Map of Parking Lot." So it was discovered that Park Commissioner Moses was planning secretly to destroy the glen -- a quiet, shady spot where little children loved to play -- so as to build another parking lot for the Tavern on the Green, the pricey nearby restaurant he had created in 1934 as a part of his Central Park renovation. Local opposition immediately materialized, with a petition signed by 23 mothers sent to Moses, with a copy to Mayor Robert Wagner. Having just completed the Coliseum, Moses, then at the height of his power, saw this fuss over a small parking lot as trivial. He determined to proceed as usual in such situations by starting the work of demolition at once, thus rendering any opposition futile.