Clifford Browder's Blog, page 52

July 10, 2013

71. The Magnificence and Insolence of Trees

Twigs of the tree of heaven.

Twigs of the tree of heaven. There are wonders all around us, but we don't look.

I have always loved trees. It began in my childhood in Evanston, where the streets were lined with arched elms that provided welcome shade in the summer. The most unathletic of boys, I still loved to climb in the willow trees on a nearby riverbank. (I say "riverbank," but it wasn't really a river, just a sewage canal. Unpoetic, but at least it didn't smell.) Right on our street, and on many other streets, was the tree of heaven, or ailanthus, which gave off no heavenly scent but a stink. And if you stripped a twig of its leaves, you had a pliant switch. I know because an older friend of mine, having provided himself with just such a weapon, challenged me to a duel, and when I declined, lashed my bare legs with his switch, which sent me rushing home with tears of rage.

This is the stuff my brother loved to set on fire.

This is the stuff my brother loved to set on fire.EnLorax But the great tree of my childhood was a giant cottonwood that towered in a neighbor's yard just across an alley from our own back yard, a tree so huge that it robbed our neighbor of sunlight, but so costly to remove that he simply had a few branches severed and left the rest. In June it gave its cottony seeds to the breeze, and everyone's lawn was whitened for many days, and I went about sneezing, since I was allergic to the stuff. My older brother took delight in setting fire to those seeds, ostensibly to spare his kid brother some sneezes, but really just to create a little havoc. Fortunately, he never set the neighborhood on fire. In summer I would lie on a flat roof next to our sleeping porch, hoping for a tan while watching a breeze ripple through that vibrant mass of silver-flecked green: a pulsing continent of life.

Eucalyptus leaves and fruit. I loved to crush the

Eucalyptus leaves and fruit. I loved to crush theleaves and breathe in the intoxicating scent.

Emöke Dénes Yes, this blog is supposed to be about New York, and I'll get there soon enough, but allow me one more digression, a side trip to Southern California, where I went to college. There, one Easter vacation when everyone else flocked to the beaches for sun by day and erotic and boozy revels by night, I myself, stuck carless in tranquil Claremont, trekked its tidy streets studying the trees of that strange clime, most of them imports from distant places. There were palm trees both native and from the Canary Islands, acacias from Asia, eucalyptus from Australia, and the Mexican pepper tree. One huge pepper tree loomed in an undeveloped lot that I often crossed on my way to classes, breathing in a subtle aroma of pepper. But the most memorable fragrance came from the crushed leaves of the eucalyptus, the headiest, most intoxicating scent that I have ever experienced from a tree. As for majesty and sublimity, I encountered them later when I went to Muir Woods, an old-growth redwood forest near San Francisco, and had my first glimpse of redwoods, some of them 1200 years old, towering giants that made us humans seem like puny little creatures indeed.

Redwoods in Muir Woods.

Redwoods in Muir Woods.So at last we come to New York. Within two blocks of my apartment there are magnolias, cherry trees, gingkos, redbuds, and a mystery tree I was for years unable to identify. The mystery tree is 30 to 60 feet high with white flowers of the rose family (5 petals and a cluster of protruding stamens); it's all over on the streets, blooming every April. None of my friends could identify it, but my online query to the Parks Department finally received a response. It is the callery pear, a name I had never heard of before, and the second most common tree on the city's streets. (And the most common one? They didn't tell me. My candidates: gingko biloba, Norway maple, American basswood.)

My mystery tree in bloom.

My mystery tree in bloom. The fan-shaped leaves of the gingko. The gingko biloba is a strange thing with fan-shaped leaves often divided into two lobes. A native of China, it has no close living relatives but resembles fossils from 270 million years ago. A common cultivated tree here and elsewhere in North America, it was long thought to be extinct in the wild, but now may still grow in two small areas in eastern China. A rarity, then, but here it is on West 11th Street, turning yellow every fall and bearing soft fruitlike yellow-brown seeds that smell like rancid butter or vomit, as I discovered one autumn when, an amateur forager (see post #23, September 2012), I investigated it. Suburbanites complain of the smell and mess of the fallen fruit, which can render sidewalks slippery as well as stinky. Yet at the North End of Central Park I have seen Chinese women busily gathering the fallen fruit, which is believed to have both culinary and medicinal values, and value also -- though I haven't checked it out -- as an aphrodisiac. In any case, the smell put me off, so I gave up on foraging it. Yes, I know it's prized by herbalists and used by Western medicine to enhance memory and treat dementia, and for other stuff as well, but my God, that smell of vomit! But it's a tough baby, so tough that six gingko trees survived the atom bomb in Hiroshima charred but intact, and in time became healthy again. One of the strangest trees I've ever known, growing almost on my doorstep. It will probably survive us all.

The fan-shaped leaves of the gingko. The gingko biloba is a strange thing with fan-shaped leaves often divided into two lobes. A native of China, it has no close living relatives but resembles fossils from 270 million years ago. A common cultivated tree here and elsewhere in North America, it was long thought to be extinct in the wild, but now may still grow in two small areas in eastern China. A rarity, then, but here it is on West 11th Street, turning yellow every fall and bearing soft fruitlike yellow-brown seeds that smell like rancid butter or vomit, as I discovered one autumn when, an amateur forager (see post #23, September 2012), I investigated it. Suburbanites complain of the smell and mess of the fallen fruit, which can render sidewalks slippery as well as stinky. Yet at the North End of Central Park I have seen Chinese women busily gathering the fallen fruit, which is believed to have both culinary and medicinal values, and value also -- though I haven't checked it out -- as an aphrodisiac. In any case, the smell put me off, so I gave up on foraging it. Yes, I know it's prized by herbalists and used by Western medicine to enhance memory and treat dementia, and for other stuff as well, but my God, that smell of vomit! But it's a tough baby, so tough that six gingko trees survived the atom bomb in Hiroshima charred but intact, and in time became healthy again. One of the strangest trees I've ever known, growing almost on my doorstep. It will probably survive us all. The fruit of the gingko, beneficial but smelly.

The fruit of the gingko, beneficial but smelly.W

A redbud in full glory.

A redbud in full glory.Dcrjsr Less mysterious and exotic is the redbud, a small tree of the pea family that bears pink flowers in the spring before the leaves appear. My mother once came back from a spring visit to rural Brown County, Indiana, raving about the beauty of the flowering dogwoods and redbuds in the woods. Dogwoods I have seen in every forest I have visited in the spring, but redbuds never. So redbuds became an elusive but sought-after prey, once prompting a special expedition to Inwood Hill Park that proved fruitless. Then, a year ago, I found one, labeled and blooming, in the little park just across the street, and this year I have seen them in that park and elsewhere in the neighborhood. A lovely little tree bearing pea family flowers clustered on its branches, well worth my quest through the years.

There is no way I can mention all the trees in city parks that I relate to, so I'll just mention a few. In my post on foraging (#23 again) I told how I have harvested wild apples in Van Cortland and Pelham Bay Parks and the Staten Island Greenbelt. If I finally gave that up it was because the yellow apples were small and afflicted with dark spots that had to be cut out, leaving not much apple, while at the same time the greenmarkets were full of large, ripe, often flawless apples with a superb taste that you get only from freshly picked apples for a month or two in the fall.

No, these aren't apples, but black walnuts still on the tree.

No, these aren't apples, but black walnuts still on the tree.Sue Sweeney

The dried nut.

The dried nut.Jamain Another attempt at foraging likewise proved a fiasco. Black walnuts grow wild in the city parks, and I had heard that they, like their cousin the English walnut, are edible, which sounded good to me. The nut is contained within a green, fleshy husk, rather like a shrunken tennis ball, that falls to the ground in autumn, so you might think harvesting the nuts is easy. Well it ain't. First of all, the husk clings to the nut, so to remove it you're advised to stamp on the fruit with old shoes to get the husk off. What you then have is a corrugated brown nut that stains your fingers if you touch it, so rubber gloves are advised. (If you get the stain on your fingers, don't worry, it will come off -- in a few days.) So now you have to let the nuts dry on newspapers for a week, so as to eliminate the stain. Even then you don't have the edible kernel, which is locked inside the nut. But you can get at the kernel; all you need is a heavy-duty nutcracker, a vise, a heavy hammer, or a large rock. (At this point I'm tempted to say a boulder.) So finally you crack the nut open and there, inside, is the long-sought meat, which you remove with a pick. I'd been told that black walnut has a strong, rich, smoky flavor with a hint of wine, and that it can be used in any recipe that calls for nuts, but it must be used sparingly, or it will overpower the other ingredients. After all this to-do -- the gathering, the stamping, the stain, and then the long week of drying, climaxed by the bashing and cracking -- I expected something wondrous, a taste that would vault me to pinnacles of bliss. No go: the taste impressed me as unimpressive and certainly not worth all that effort. Since then I've been quite content to consume the commercial English walnuts readily available in stores and requiring no such lengthy preparation. But good luck, if you want to try.

Most mature trees have dark, ridged bark that doesn't help laymen much in identifying the tree, but three exceptions come to mind: the mottled bark of the sycamore, the papery bark of the paper birch, and the smooth bark of the beech -- all three of them to be found in city parks. My favorite sycamore is a huge tree in Van Cortlandt Park, its trunk some four or five feet in diameter, with the typical sycamore bark showing green, gray, brown, and white patches that resemble U.S. Army camouflage, the kind you see very unmilitary-looking young men wearing on city streets. A giant of giants, yet few park visitors stop to admire it. (Fewer still notice the stand of poison hemlock growing nearby -- the stuff that did Socrates in -- but that's another story.) The bark of the paper birch peels off in horizontal stripes, leaving black marks on the trunk. As its other name "canoe birch" implies, the Native Americans of the Northeast used it to make canoes. And the smooth gray bark of the beech invites graffiti, often the initials of lovers cut into it -- avowals that may be embarrassing in a year or two, since fervor fades, whereas beech bark endures.

Sycamore bark.

Sycamore bark.Jim Thomas

Paper birch bark.

Paper birch bark.Sue Sweeney

Beech bark with graffiti.HorsePunchKid

Beech bark with graffiti.HorsePunchKidI won't go into the colors of foliage in autumn, since it's not the season. Instead, I'll mention what about trees grabs me most in any season: their architecture. Their roots plunge deep in the soil, their trunks rise nobly, and their twigs reach for the sky. This is seen best in those that tower, when they stand singly and assume their full proportions: beech, cottonwood, sycamore, and above all oak.

David Lally

David LallyTrees figure prominently in myth and legend, where the roots are identified with the underworld, the trunk with the middle world or earth, and the soaring branches with the upper world or heaven. Connecting all aspects of creation, they become the World Tree or Cosmic Tree, whose fruit has healing powers or confers immortality. In my post on gardens (#57, April 2013) I mentioned the Tree of Life in Eden and the tree bearing golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides. Both conferred immortality, both were forbidden to mortals; to prevent Adam and Eve from eating of the fruit and becoming immortal, Yahweh drove them from Eden and placed cherubim with a flaming sword to guard the Tree of Life. So obviously, those trees have got a lot going for them.

The Tree of Life appears in the myths and religions of ancient Persia and Egypt, Assyria, China, the Baha'i faith, the Kabbalah, Mesoamerica, and elsewhere, and has inspired many artists. In Egypt it was sometimes portrayed as a nurturing mother, another manifestation of the Goddess (aka Big Mama) discussed in another post (#59, May 2013). Christianity has identified it with the Cross; the tree of death of the Crucifixion becomes the tree of life of the Resurrection. It also appears in a vision in the Book of Mormon, where a path leads to a tree symbolizing salvation.

The Tree of Life from the Book of Mormon.

The Tree of Life from the Book of Mormon.

A modern Tree of Life in a Swedish church.

A modern Tree of Life in a Swedish church.Hakan Svensson

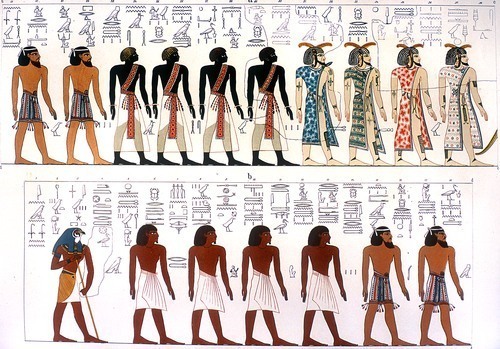

From the tomb of Thutmose III (1500-1450 BCE).

From the tomb of Thutmose III (1500-1450 BCE).The Pharaoh is fed from the holy tree.

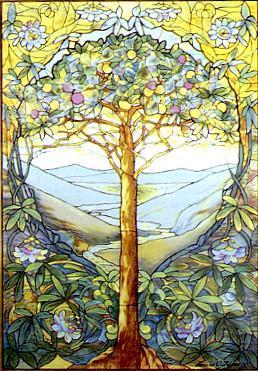

The Tree of Life: stained glass by Tiffany.

The Tree of Life: stained glass by Tiffany.In Norse mythology the world tree Yygdrasil is a holy tree where the gods assemble daily tohold court. Various creatures reside in it, including an eagle, a squirrel, and four stags. The three Norns, who rule the destiny of gods and men, bring water from a holy well and pour it over the tree, so its branches won't rot away or decay.

Yygdrasil and the creatures that inhabit it.

Yygdrasil and the creatures that inhabit it.From a 17th-century Icelandic manuscript.

By now, I hope that the magnificence of trees is apparent, and you can understand why, in passing a park, I always stop to admire the grand, leafy fullness of trees. But why do I also mention their insolence? Here we go into fantasy. In a poem I have imagined a dialog between the trees and myself. In it the trees put me down as a fruitless, rootless creature who dithers about, lacking their calm, earthed fixity. When I protest that my daily motions and varied feelings are meaningful, they laugh contemptuously and dismiss every other claim of mine to a significant existence. Finally, when I mention my vitamin-rich, fiber-crammed diet, pesticide-free and locally grown, they answer scornfully, "Runt, what do you eat? We eat the sun!" Finding no answer to this, I retreat to a more comforting communion with weedy fields and tufts of small grasses, which, despite my memories of towering sun-flecked continents of green, are reassuringly squat and sensible. So trees in their magnificence can be seen as dwarfing us and reminding us of our puny dimensions, our insignificance. Not a bad note to end on, but for a final touch I'll quote the ending of a poem by Joyce Kilmer (not my favorite poet, but relevant here):

Poems are made by fools like me, But only God can make a tree.

To which I'll simply add: Yes, but with the help of Big Mama, who sticks her nose (and other apparatus) in everywhere. (Again, see post #59, May 2013: Earth Goddesses: Big Mama.)

Note: One year ago, on July 11, 2012, this blog began. The first post: 16. My Love/Hate Affair with WBAI. That affair continues to this day. Prior to that I was sending e-mails to friends; those e-mails appear as 15 vignettes in this blog.

Coming soon: Next Sunday, Liars, Cheats, and Manipulators. Also, fittingly, a note on two New York politicians disgraced and ousted from office by sex scandals but now rising like the phoenix from its ashes to run for office again: Eliot Spitzer and Anthony Weiner. Their resurgence confirms yet again the name of this blog: No Place for Normal: New York.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on July 10, 2013 05:37

July 7, 2013

70. Me and the Seven Deadly Sins

In Christian and especially Catholic tradition there are seven deadly sins, indulgence in which destroys the life of grace and charity and therefore creates the risk of eternal damnation. These sins are the source and origin of all other sins. The seven, in the order in which I shall treat them, are sloth, gluttony, envy, lust, greed, pride, and wrath. In a rare moment of introspection I have decided to examine myself for signs of each of the seven, and at the same time to see which may characterize the city of New York and the nation. A noble and weighty undertaking, not to mention a courageous one. So here goes.

Sloth

Shrewdly, I begin with the sin that I honestly think myself least guilty of. I feel the need to always keep myself busy and above all to occupy my mind. Yes, I can take a break when necessary, but I always go back to whatever project I have in hand. Since I'm a writer, this usually means a writing project, as for instance a post on sins for my blog. Similarly, I think New Yorkers are immune to sloth. This city is, and always has been, a mecca for hustlers, a magnet for the eager and ambitious. And the nation too is rarely subject to sloth; our capacity for action over the years has at times had unfortunate consequences for our neighbors. We are doers, go-getters, achievers. We have other sins but, I at first concluded, not the sin of sloth.

In 1556-1558 the Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder did a series of seven engravings illustrating the Seven Deadlies that I find so engaging I shall offer them here. They follow the same pattern: in the center foreground is a human, more often a woman than a man (feminists, take note!), who represents one of the sins, with an appropriate symbolic animal close by. All around is a fantastical landscape reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch, with weird constructions and all manner of humans, including giants, and bestial-looking demons engaged in actions exemplifying the sin. Shocking, puzzling, or amusing, the details are well worth examining, though I can't begin to explain them all. Some express Flemish proverbs we are not familiar with. These landscapes have been called surreal, but in fact they are quite logical and ordered, each detail illustrating the sin in question. For traditional Christianity sin was a serious matter; it lowered us to the level of animals and was ugly to behold.

Sloth (Desidia), by Bruegel. For him, sloth seems to be a kind

Sloth (Desidia), by Bruegel. For him, sloth seems to be a kind of sleeping sickness. The associated animal is a snail. Did I say Americans aren't guilty of sloth? Well, I have changed my mind. Yes, when I go out on errands I see runners whizzing by, and cyclists pumping furiously in the bike lanes (or conspicuously not in them), which suggests an energetic city and nation. But why, then, this epidemic of obesity that we hear so much about? Some Americans are certainly active and agile, but thanks to the automobile, television, and the Internet, many others are strangers to exertion; they would rather drive than cycle or walk, and prefer to sit passively in front of their TV sets or computer screens than to do even a gentle bit of yoga, much less anything so strenuous as tennis or swimming. As for golf, most golfers now rent little put-puts to drive them about the links, and so avoid anything so challenging as walking. Yes, many of us are sunken in sloth, a fact that my account of gluttony will extend even further.

Gluttony

Another sin from which I seem to be exempt. I eat my three squares a day, but between meals I'm not even tempted to snack. I enjoy food, but it isn't the center of my life; there's so much else to do.

Bruegel on gluttony (Gula). She is sitting on a pig and guzzling from a pitcher. On the left, a

Bruegel on gluttony (Gula). She is sitting on a pig and guzzling from a pitcher. On the left, a man vomits into a river. In the right background a man's head in the shape of a windmill

is being force-fed.

Thomas Aquinas took a broader view of gluttony, which for him included an obsessive anticipation of meals, and the constant eating of delicacies and excessively costly foods; it is sinful, he opined, to eat too soon, too expensively, too much, too eagerly, too daintily, or to eat wildly. Of all these variations of the sin I'm still exempt. Maybe my aversion dates from the day when, in the college dining hall, I happened to get a hot dog still encased in its wrapping, on which were printed all the ingredients, a hodgepodge of meat scraps that was both appalling and disgusting. Ever since I've had an aversion to wienies. Which is especially relevant now, in the wake of the annual Fourth of July hotdog-eating contest sponsored by Nathan's at Coney Island, which was won again this year -- for the seventh time -- by Joey "Jaws" Chestnut, who gorged his way into history by consuming 69 hotdogs and buns in 10 minutes.

Honestly, can you blame me? But please, no jokes.

Honestly, can you blame me? But please, no jokes. Finger-lickin' good.

Finger-lickin' good.Brent Moore

New Yorkers are no more guilty of gluttony than the nation as a whole. Ah, but that nation as a whole is constantly guzzling Cokes and Pepsis, gulping down pizzas and french fries and Tootsie Rolls, devouring Snickers and Fritos and potato chips, and the exquisite sugary concoctions -- admittedly delicious -- dispensed by the celebrated Magnolia Bakery on the ground floor of my building. Of course we have an epidemic of obesity, hence an epidemic of diabetes. Is there gluttony in America? Are we eating too soon, too much, and too eagerly, and eating wildly? Just have a look at the nearest fast-food restaurant. Guilty, guilty, guilty as charged!

Envy

Envy, from an 1894 pulpit in Saint

Envy, from an 1894 pulpit in SaintBartholomew's Church, Reichenthal,

Austria.

Hermetiker

Envy involves coveting something that someone else possesses; in the words of Aquinas, it is "sorrow for another's good." This too I seem to be free of, though I've often had the opportunity to resent someone else's success and wish it for myself. But somehow I've never ventured down that sinister pathway. Nor do I think New Yorkers, or Americans generally, particularly prone to envy. We find our worst sins elsewhere.

Bruegel's envy (Invidia). Near her is a turkey, a bird newly discovered in North America, and two dogs (or pigs?) fighting over a bone. I find many of the details baffling, as for instance the shoes

Bruegel's envy (Invidia). Near her is a turkey, a bird newly discovered in North America, and two dogs (or pigs?) fighting over a bone. I find many of the details baffling, as for instance the shoesin the left and right foreground.

Lechery

I've always been at heart monogamous and not inclined to stray. Bob and I have been in a stable relationship for forty-five years, which to some may sound dull, but for us has been reassuring and rewarding. But for anyone to be monogamous in this permissive society is amazing, since we are assaulted daily by sexually explicit ads. At the checkout counter of my supermarket recently I beheld, at eye level, a glossy women's magazine with the enticing suggestion, "Have a great butt." Of course an illustration accompanied it, with the relevant anatomy conspicuously displayed.

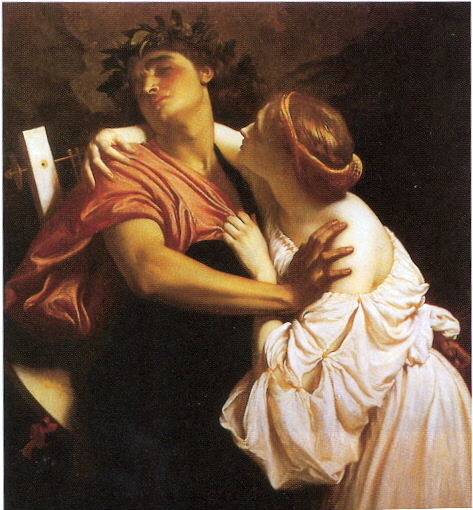

Bruegel's lechery (Luxuria). Fornication everywhere; even the dogs are at it.

Bruegel's lechery (Luxuria). Fornication everywhere; even the dogs are at it.Balzac's novel La Cousine Bette gives a marvelous portrait of lechery in the person of Baron Hulot, whose passion for his neighbor's complaisant wife, Mme Marneffe, leads to the disintegration of his moral and physical being. But one doesn't have to go to literature to encounter lechery; I have known two friends who were hopelessly enslaved by it. One in a candid moment told me that he was addicted to sex, that every so often the feeling came over him that he would be totally unworthy as a person, unless he went out and had sex with a man every night that week. I had never thought of sex as a possible addiction, but he convinced me. Another friend whom I had known years before was constantly, as he phrased it, "tom-catting about," having casual sex with strangers on a regular basis. He had married a Japanese woman because, as he explained to me, if a Japanese husband chooses to go out alone at night, giving no explanation, the Japanese wife acquiesces and asks no questions. Of this he took full advantage. He often regaled me with his adventures, sent me postcards from the Caribbean featuring clusters of phallic bananas, and offered tantalizing tidbits of information, as for instance the latest fashion in French male underwear, and how casual French lovers switched to the intimate tu in moments of passion, then reverted to the formal vous afterward. The first friend is now in a stable longtime relationship and free of his addiction. The other one I haven't seen in years; I wonder what has become of him. Perhaps, as he got older, the tom-catting subsided, and the wife could claim him fully at last. Perhaps.

Greed

So far, viewers will note that, by my own accounting, I've gotten off scot-free. But now the plot thickens. I confess to being, to some extent, guilty of greed, the desire to acquire or possess more material wealth than one needs; I am, in a small way, a greed creep. But how could I or anyone not be, when we live in a capitalist society that sees everything in terms of money and encourages its acquisition by all means fair or foul? Especially in this country, where wealth, not social rank or merit, brings respect and security, and there is no national health-care system to rely on as one gets older. SAVE, SAVE, SAVE! urge financial advisers, and how is one to do it without becoming just a bit greedy?

Bruegel's greed (Avaritia); near her, a toad. The victims seem to be stripped to their underwear. In the left background a mob is assaulting a fantastical structure that probably contains a treasure. On the right, archers shoot at a bag containing coins that rain down on the ground.

Bruegel's greed (Avaritia); near her, a toad. The victims seem to be stripped to their underwear. In the left background a mob is assaulting a fantastical structure that probably contains a treasure. On the right, archers shoot at a bag containing coins that rain down on the ground.Christ drove the money changers out of the temple, an action that many artists have illustrated. And the medieval Church looked askance at money and its accumulation, deeming the charging of interest for loans to be sinful. Jews, not being Christian, could practice money lending, but in early Renaissance Italy banks developed to answer the needs of a mercantile society and even conduct business for the Church. So if the Church, in spite of its misgivings, found banks and banking to be a necessity and had good uses for money, I guess my modest stabs at greed can be forgiven.

Christ Driving the Money Changers out of the Temple.

Christ Driving the Money Changers out of the Temple.Valentin de Bourgogne, ca. 1610

Ah, but how about Wall Street and corporations generally? Think of the banks and cigarette companies, or Big Pharma, which is constantly being fined for misrepresenting its products and committing other peccadilloes? Too often government lets corporations write its laws, or crafts laws with cunning loopholes to accommodate their interests. I cite again my favorite Occupy Wall Street sign: TODAY ONLY: BUY ONE SENATOR, GET ONE FREE. The Sunday Business Section of a recent Sunday's Times (June 30) listed the pay of 200 top U.S. executives. The total compensation of Oracle's CEO was a whopping $96 million, that of CBS's CEO $60 million, and so on down the scale to a paltry $11 million for GM's top honcho. In America the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. Is greed inherent in capitalism? Is there such a thing as compassionate or principled capitalism? Well, one can always dream.

Pride

In Christian tradition this is the worst of the seven, the one that got Satan thrown out of heaven and cast down into the sulfurous precincts of hell. It is defined as the desire to be more important or attractive than others, and as excessive love of self. Dante described it as "love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one's neighbor."

Bruegel's pride (Superbia). She eyes herself in a hand mirror, next to a peacock flaunting its tail.

Bruegel's pride (Superbia). She eyes herself in a hand mirror, next to a peacock flaunting its tail.So am I guilty of pride? We all have moments of high self-esteem and I am no exception, but this in itself hardly constitutes the sin of pride. And like most people, my moments of high self-esteem alternate with moments of low self-esteem, which doesn't sound like Satan or any exemplar of pride. Also, I have a mischievous sense of humor that prompts me daily, or hourly, to laugh at myself for a fool. Pride, I think, is more likely to afflict the high and mighty than the low and trivial. One endearing comment of Lincoln, when President, was that sometimes he thought all the world were fools, and he himself the biggest fool of all. A useful bit of self-deflation, but not one that undermined his ability to govern. The sin of pride leaves little room for humor, least of all at one's own expense.

Bruegel shows pride at its worst; it is bestial, grotesque, degrading. But the Satan of Milton's Paradise Lost has a certain grandeur, and this is conveyed in the illustrations of Gustave Doré.

Doré's Satan. Defeated, but not grotesque or ugly.

Doré's Satan. Defeated, but not grotesque or ugly.So is New York guilty of pride? As the premier city of the Empire State, seat of the United Nations and a must for tourists, a center of fashion, publishing, and finance, and a preferred target of terrorists, how could it not be? In fact, it wouldn't be New York if it wasn't. Grudgingly, I allow it this sin of sins without too much condemnation.

And is America guilty of the sin of pride? You bet! The doctrine of Manifest Destiny, enthusiastically embraced in the mid-nineteenth century, meant that God or Providence or the Powers That Be wanted us to expand across the continent, albeit at the expense of our neighbors. In peace and war alike, God is always on our side. We will bring peace to the frontier, civilization to the benighted Filipinos, freedom to those who want it (or don't want it), and democracy to the world. We are a shining example of all things good, and can vastly improve the world, if the world will only heed us and follow. Today, perhaps, chastened by a few futile foreign wars, we are a little less confident, a little less imperialistic, but deep down inside I suspect that we harbor remnants, huge remnants, of these grandiose assumptions. Like all great powers, all empires, America reeks of the sin of pride.

The War to End Wars

Make the World Safe for Democracy

Manifest Destiny

Fifty-four Forty or Fight

In the Name of Jehovah and the Continental Congress

Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord

The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave

God Shed His Grace on Thee

Operation Just Cause

The Patriot Act

Wrath

I've saved the best till last, for of this sin I am admittedly, flagrantly, incorrigibly guilty. Not at the expense of others, for I'm really very patient with people, wouldn't dream of flaring up at them or in their presence. What provokes my anger is the universe, things, and myself. Wrath has been described as inordinate and uncontrolled feelings of hatred and anger. It is violent and self-destructive and can manifest itself as impatience, revenge, and vigilantism. In my case, no vigilantism, little revenge, but a vast deal of impatience.

Bruegel's wrath (Ira). This one time the figure is decidedly male: a sword- and whip-wielding soldier who with his followers massacres all before him. The associated animal is a bear. In the left

Bruegel's wrath (Ira). This one time the figure is decidedly male: a sword- and whip-wielding soldier who with his followers massacres all before him. The associated animal is a bear. In the leftbackground another soldier has a victim on a spit and pours some liquid onto or into his belly

or groin. These scenes may have been less fantastic than real in the wars of Bruegel's time.

So what provokes these rages of mine? For one thing, the laws of the universe, and above all the law of gravity, which I would like to repeal. I drop things, resent having to stoop and pick them up. Sometimes I just kick them out of sight, but then I have to retrieve them later. As for things, there seems to be no end. For instance:

pens that won't writestubby pencilschild-proof bottles that I can't openjunk mailjunk phone callsmisfiled fileslittle rugs that kick up easilyeasy-to-open packages that aren'tumbrellas whose ribs become ungluedrotating fans that won't rotatebank statements that won't balanceair-conditioners that drip on mecrumbling plastertangled hangarscrooked lampshadesa perverse and perfidious computer

Worst of all is the computer, which harasses me daily. If I'm trying to compose a text, the text jumps around on the screen; it simply won't sit still. Or the print suddenly enlarges. Or the computer informs me that I'm not connected to the Internet, when I really am. Or its officious memory proposes websites which aren't at all what I had in mind. Or suddenly a lot of gibberish appears on the screen, blotting out whatever I'm reading or working on. And so on. Whatever its limitations, my typewriter never harassed me in this way, never presumed to be smarter than me, never imposed on me things I didn't want. My computer is presumptuous, arrogant, malicious. I have never wholly trusted machines, and it knows this and wreaks vengeance. We have truces when it behaves, but they never last. It is war, war, war.

Needless to say, I disclaim responsibility for any of these provocations, computer-inspired or otherwise. I am a victim of things generally. They conspire against me, trick me, frustrate me, baffle me, even though I have done them no injury, bear them no ill will whatsoever. Although by nature inferior to humans, they don't know their place, they offend my sense of order, my tranquility. And what do I do, when provoked? Mostly I utter imprecations, blasphemies, uninspired profanities, shrieks of rage and vengeance. These are meant for my ears alone, but anyone in close proximity can't help but hear and bear witness. Not long ago I heard of a young man who, when his rented boat overturned on a lake in a park, uttered shrieks and blasphemies, scorching the ears of all around, including mothers with impressionable young children. For this outburst he was hauled into court and made to pay a fine. My heart goes out to him; there but for the grace of God (or someone) go I.

In point of fact, I rarely rage in public and my rages, though sometimes violent, end quickly, often with a bit of laughter at my own folly. But for the sake of public peace and gentility, lately I have embarked upon a campaign of gentility. Before, I muttered or uttered

##***++##*!##?***!!!

Now, in the softest voice, I remonstrate

Why, you recalcitrant little thing, you!

Or

You mischievous little devil!

Or

How can you do this to me, you naughty inanimate blob of an object?

All of which, frankly, sounds wimpish. Which raises an interesting question: Is polite, civilized behavior inherently wimpish? It may well be. Whatever Satan was or is, he certainly isn't a wimp.

Speaking of Satan, by comparison with his revolt against the Almighty, I have to confess that my rages are puny; nothing epic here, or grandiose. So puny, so quickly terminated, I have to question whether they really qualify as one of the Seven Deadlies. I hate to end on such a down note, when viewers probably hoped for shocking revelations, but can wrath over a stubby pencil or a malfunctioning umbrella or even a malicious computer merit such classification? I seriously doubt it. Bruegel wouldn't have deigned to include such trivia.

Donation fatigue: Or maybe I should say generosity fatigue, or heart failure. WBAI failed to achieve the goal of its spring fund-raising drive, so now it continues, not full-time but at intervals, to beg for donations. One fund-raiser asks for an "angel" to come forward and donate five or ten thousand dollars -- sums I have never heard mentioned before. In this game I'm not even a cherub. Having given three times already -- modestly, but still: three times -- I confess that my generosity is worn thin. When these appeals begin, I flee to WNYC, which may be doing something relevant or something silly. I know all the arguments for giving, but I can't help it; I can only take so much. And if I'm experiencing donation fatigue, so must many others. There's something very wrong. WBAI estimates that out of all its listeners only 10 percent donate. Why? I wish I knew the answer. (For me and WBAI, see posts 16, 50, and 60.)

Coming soon: Next Wednesday, July 10, The Magnificence and Insolence of Trees. Next Sunday, July 14 (Bastille Day!): Liars, Cheats, and Manipulators. And others in the offing.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on July 07, 2013 04:42

July 3, 2013

69. Jim Fisk, part 5: Such a Good Boy

This post completes the Saga of Jim Fisk. The earlier installments comprise posts 61, 63, 66, and 67. Fisk appears earlier in posts 44, 45, and 46, dealing with the Great Erie War of 1868, when Fisk, Gould, and Daniel Drew fought Cornelius Vanderbilt for control of the Erie Railway, a struggle that combined drama with farce.

* * * * * * *

Editor Horace Greeley disliked Jay Gould, loathed Jim Fisk. How could he not loathe the high-living fat man who was his opposite, Greeley being a perennial critic and crusader, an advocate of a milk and Graham cracker diet, shuffling in a country hat and floppy trousers, inveighing against drink, tobacco, dancing, and divorce? The same fervor that kindled his rebukes of Erie management sparked his tirades against Fisk’s imports of light opera, which he saw as an extension of French theater, that shameless expounder of the fine art of adultery. He was determined to make his Tribune the nemesis of Erie.

Editor Greeley in his office. Fisk’s influence was pernicious and inescapable, he told the Tribunestaff. If people were so misguided as to want to see the latest Offenbach opera, they had to go to Fisk's Opera House, and even if he wasn't in his box, all those frescoed nudes and chandeliers and thingamabobs proclaimed his grandiose offensive bad taste. If you wanted to go to Boston via Fall River, or in season to Long Branch, you had to take one of his steamboats, with egregious plush furnishings and an outsized portrait of the rogue himself. Strolling on the Fifth Avenue, you risked meeting him strutting in front of his band. And if you took refuge in the Park, there he was chortling and hallooing in a fancy rig, running wild with loose women. Half the town loved him and half hated him; the man didn’t care which, as long as he was the center of attention. In all but name, he had made this city Fiskville.

Editor Greeley in his office. Fisk’s influence was pernicious and inescapable, he told the Tribunestaff. If people were so misguided as to want to see the latest Offenbach opera, they had to go to Fisk's Opera House, and even if he wasn't in his box, all those frescoed nudes and chandeliers and thingamabobs proclaimed his grandiose offensive bad taste. If you wanted to go to Boston via Fall River, or in season to Long Branch, you had to take one of his steamboats, with egregious plush furnishings and an outsized portrait of the rogue himself. Strolling on the Fifth Avenue, you risked meeting him strutting in front of his band. And if you took refuge in the Park, there he was chortling and hallooing in a fancy rig, running wild with loose women. Half the town loved him and half hated him; the man didn’t care which, as long as he was the center of attention. In all but name, he had made this city Fiskville.On November 25, 1871, the long-heralded case of Mansfield vs. Fisk – the libel suit, not the action to snag fifty thousand dollars – came up before Judge Bixby at the Yorkville Police Court on East Fifty-seventh Street. The packed audience had scratched and shoved to get in, one woman fainting and an elderly gentleman having his pince-nez shattered in the process; the police intervened to keep order. Pencils poised, the press were out in force, the Herald chronicler eager to recount, now in Roman mode, the exploits of Caesar Fisk, Mark Anthony Stokes, and Cleopatra Mansfield, while the Tribune scribe prepared to pillory Antichrist.

Necks craned as the principals assembled. The Herald man was scribbling images already: Fisk’s stickpin “shone out of his fat chest like the danger light at Sandy Hook bar,” while Stokes’s diamond pinkie ring “glowed like a glowworm in a swamp.” Prince Erie was wearing his admiral's uniform, but his face was grim, his mustache waxed to a point, while Stokes, attired in an Alexis coat of dull cream color (the latest latest style) and polished black boots, sat stiffly, swinging his cane nervously between his knees as he waited for the proceedings to begin.

Watched by all, Miss Helen Josephine Mansfield took the stand in a black silk dress with flounces, veiled, her bosom snowy with lace, and wearing a jaunty Alpine hat with a feather. Showing poise that almost masked the hurt in her voice, she testified how Mr. James Fisk, Jr., had libeled her and Mr. Edward S. Stokes by accusing them of trying to blackmail him by means of his letters; her good name had been sullied. Then Fisk’s attorney, armed with information newly acquired by his client, closed in.

“Years ago in San Francisco, wasn’t a gentleman by the name of D.W. Perley found in your company clad only in a shirt, and allowed by your stepfather to leave only after signing a check for a substantial amount at pistol point?”

Miss Mansfield winced, paled. Her attorney protested vigorously: “The witness’s veracity is not to be confused with her chastity!” Amid snickers from the audience, the judge allowed Fisk’s attorney to proceed. He repeated the question.

Miss Mansfield’s voice trembled. “Yes, there was a circumstance of that kind happened, but he was fully clothed, and the check was in payment of a debt. My virtue was not in question.” (More snickers.)

“When you were acquainted with Mr. Fisk, didn’t he supply you with a steady flow of funds?”

“He was only a friend. I am a lady of independent means. My money comes from speculations in stocks.”

“When the Erie Railway board of directors were in exile in Jersey City, were you there as well?”

“As a friend. I had a suite at Taylor’s Hotel.”

“Did anybody occupy it with you?”

“All the time, you mean?”

“You know what I mean.” (Snickers.)

"Mr. Fisk did, sometimes."

"Anybody else?"

"During the day it was used as a sort of rendezvous by the officers."

"During the night only by yourself and Colonel Fisk?"

"Yes, that is all, I think."

On the stand for three hours, she maintained her poise, but when she left the stand, it was clear to all that she and Stokes had indeed been conspiring against Fisk.

At Christmas Jim Fisk went to see his wife Lucy in Boston. (Yes, he had a wife. If followers of this blog have forgotten her, so at times did Fisk himself.) Lucy was back from Europe now; had the scandal reached her ears? Though he dreaded it, he had to confess. He did, portraying Josie as a venal wanton, himself as a pliant fool. His jenny wren was shocked. How could her boy have done this? Jim Fisk wallowed in contrition, declaring himself unworthy of her forgiveness. Though a stranger to motherhood, Lucy Fisk brimmed with maternity. Of course she forgave her little boy. He'd done a bad thing, but he hadn't been happy, had he? She soothed him, reassured him. Jim Fisk left Boston forgiven, but troubled. He had destroyed Lucy's calm of innocence with the hurt of knowledge. Would she ever be the same?

DOWN WITH THE ERIE ROBBERS! screamed the Tribune, insisting that Fisk’s letters contained sufficient evidence to send all the Erie rogues to prison. With shareholders up in arms, tracks broken, trains derailed, and his partner’s private life destined for further exposure in the courts, Jay Gould went to Fisk again, determined to set the Erie house in order: Fisk had to resign as vice president of the railroad. Choking back tears, on the last day of the year he did so; Prince Erie no longer. That same day an Erie engine jumped the track near Hackensack, crushing the fireman’s foot, and another gold speculator brought suit against Fisk and Gould for fifty thousand dollars.

On January 6, 1872, the case of Mansfield vs. Fisk came up for its second hearing. Fisk himself was not present, since his testimony was scheduled for a later session, but the plaintiff was very much there, in a velvet jacket over a dress of black silk. Stokes was also on hand in an elegant coat, his boots polished, but looking worried, as Josie took the stand again and was subjected to ruthless questioning by Fisk's attorney. As the examination continued, her poise crumbled, her voice faltered: she had no recollection of this, denied that, never tried to blackmail Mr. Fisk. Her own testimony revealed her as a scheming doxy older, crasser, and greedier than Fisk had ever dreamed. She left the stand in tears.

Her cousin Marietta Williams took the stand briefly to defend the respectability of the Mansfield household, where she also resided, then was questioned by Fisk’s lawyer about Miss Mansfield’s character.

“Her general habits – ” she began.

“I don’t mean her general habits,” said the lawyer. “That would involve an extensive range of inquiry.”

The spectators roared, Stokes glared, and Josie buried her teary face in a handkerchief.

When Stokes took the stand in turn, he insisted that his friendship with Miss Mansfield was platonic. When he called on Miss Mansfield, her cousin always sat between them.

“Did you stay at Miss Mansfield’s overnight?”

“Only when the weather was stormy.”

“It must have been an inclement year!”

The spectators roared again.

Further questioning completed the portrait of Stokes as little more than a fancy man sharing with Josie the bounty she had wheedled out of Fisk. When the court adjourned for lunch, Stokes stepped down from the stand, nerves shaken, his delicate being spiked on barbs of scorn. One of his lawyers pulled him aside and informed him that the case was hopeless and had to be dropped. Fighting off the sting of despair, Stokes let his lawyers whisk him off to Delmonico’s for oysters and ale. There they were greeted by Judge Barnard, who informed them that a grand jury had just indicted Stokes and Josie for attempting to blackmail Fisk. The young man's rage seethed, his features tightened.

Getting word at his Opera House office of the morning's court proceedings, James Fisk, Jr., washed at his nymph-adorned marble-and-porcelain washstand, stopped at the Opera House bar for a lemonade, and went forth by carriage in a silk hat and scarlet-lined cloak, diamonds ablaze, savoring a taste of triumph. Having decided to visit the widow of an old friend whose family he was helping financially, he shouted the address to his coachman in a voice that anyone in the vicinity could hear. Stokes was in the vicinity.

Alighting from his carriage at the Grand Central Hotel on Broadway, Fisk whistled, bounced up the stairs. Stokes loomed at the top, revolver in hand: “I’ve got you now.”

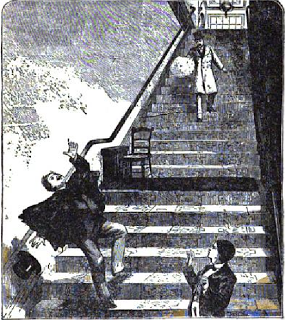

The witness is a young hotel porter. From

The witness is a young hotel porter. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

Astonished, Fisk froze: a perfect target. A bullet burned his arm, another ripped his stomach; he wailed, staggered, grasped the handrail, didn’t fall. As Stokes fled into the hotel, people flocked to the downstairs entrance, helped the wounded man up the stairs through a lingering smell of gunpowder, and deposited him in an empty room with a bed; a doctor was summoned.

Outside, the news raced through the streets, rippled the length of horsecars, splashed into restaurants and shops. Barbers paused, razors held in midair above their lathered customers; bellboys blurted it to managers; at the Opera House, clerks gasped, dancers wept. While newspapers stopped their presses and began writing the biggest story in years (“He can’t even die quietly,” muttered Greeley), armies of lawyers wondered how this would affect the reams of red-taped documents wedged in cubbyholes in roll-top desks.

In room 213 of the Grand Central Hotel, while police and reporters flocked outside, the house physician dressed the arm wound, probed the stomach wound, couldn’t find the bullet, gave him a brandy and water.

“Doctor,” said Fisk, his stomach aflame, “if I’m going to die, I want to know it beforehand.”

“Colonel, you’re not going to die tonight, and not tomorrow either, I hope.” His voice held scant assurance.

More doctors came, gave him chloroform, probed deep for the bullet, couldn’t find it in the mass of his flesh. “For God’s sake, send for Lucy,” he gasped; they did. Arrested on the hotel premises by bystanders, Stokes was brought in, mute, rigid, glaring. Fisk looked: “Yes, that’s the man who shot me.” They took him away.

Tweed came. “Colonel, how do you feel?”

“Like a little boy who’s run away from school and eaten green apples. I’ve got a bellyache.” They gave him morphine.

Jay Gould, his features rarely warped by sentiment, arrived, looked at his only friend, sat tensely in an adjoining room with others, bowed his head, burst into sobs.

Informed by a Herald reporter at home, Josie Mansfield paled. “Stokes must have been insane!” Then, collecting herself: “I am in no way connected. I have my reputation to maintain.”

Locked in a cell at the Tombs, Stokes lit a cigar, flung it away, lit another, flung it away, lit another.

The press kept watch all night while he rallied, sank. “I’m not afraid to die,” he whispered, as doctors, friends, brass bands, and champagne and pickled oysters at Delmonico’s fuzzed into a haze, and the haunting silence that he had always dreaded loomed. A little boy groping through a cold mist, alone; terror, then a warming presence.

Toward dawn Lucy Fisk had arrived from Boston, found him in a coma. She sat with him for hours, soothed him, held his hand. Gently, he died. She kissed him, wept.

“He was such a good boy.”

Gotham and the nation were shocked: Colonel-Admiral James Fisk, Jr., impresario and Prince of Flash, had bounced into the void.

“Whoremaster! Profligate! Antichrist!” thundered pulpits throughout the nation. Intoned the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher in Brooklyn, “I say to every young man who has looked upon this glaring meteor, ‘Mark the end of this wicked man, and turn back again into the ways of integrity!’ ” Noted Greeley’s Tribune, “Mr. Gould will be glad to be rid of this encumbrance and hide all Erie’s crimes in his grave.” The Stock Exchange refused to fly its flag at half mast; Erie stock surged on the market. But Erie clerks and workers, chorus girls, and bellboys mourned: “Damn it, he was fun!”

At the Tombs Ned Stokes, in a velvet dressing jacket and silk socks, fought off bedbugs, dined on catered veal. Lynch talk surfaced among Erie employees and the men of the Ninth Regiment; two hundred and fifty policemen guarded him, with a squad at Josie Mansfield’s.

In the vast marble lobby of the Opera House the colonel, a pudgy veteran of Wall Street and boudoir battlefields, lay in state in his blue uniform, gold-laced with red epaulets, his regimental sword at his side, as hundreds filed by to pay their respects.

“Once more, dear friend, for the last time,” said his barber, who, touching the waxed ends of the colonel’s mustache, gave them an expert twirl. The rosewood coffin was closed.

With muffled drums the teary-eyed Ninth Regiment – hoarding memories of beer-spouting Opera House parties with high-kicking dancers, hosted by the braidiest, craziest, rip-roarin’est colonel in the world – bore forth the coffin followed by a riderless horse, stirrups reversed, plus six colonels and a general in black-draped, solemn pomp. It would have made him proud.

Multitudes watched, the crush so great that five ladies fainted.

“A friend of the poor,” sobbed a waiter girl.

“A bully boss,” said a tough.

“Nothing like it,” a blueblood muttered, “since Lincoln died; obscene.”

At the New Haven depot they saw him off on a Brattleboro train furled with smoke and crepe. Was his funeral the last caper of a master of surfaces and fun? Had he learned from his hurt? Had he left on the witnessing world any more meaningful impression than the glint and flickerings of Flash? The city didn’t know, but having lately called him rogue, lecher, thief, it missed his whistle and shine.

A week after his death, Fisk's letters to Josie were finally published by the Herald; they revealed nothing about Erie corruption. Bogus biographies of both Fisk and Josie also soon appeared. Two hundred and fifty of Fisk's canaries were sold at auction. His fortune turned out to total a mere million, much of it having been gobbled up by legal expenses. In Brattleboro the citizens put up an impressive cemetery monument adorned with -- appropriately -- four scantly clad young women representing railroads, shipping, trade, and the stage.

Edward S. Stokes was tried for murder, but claimed that he had shot Fisk in self-defense, since Fisk had whipped out a pistol and meant to shoot him; Josie Mansfield appeared for the defense. Though witnesses for the prosecution testified that Fisk owned no guns at all, the jury could not agree. At his second trial Stokes was convicted and sentenced to be hanged, but he won an appeal and was tried a third time, convicted of manslaughter, and sentenced to six years in prison. He served four years at Sing Sing, where influence got him lenient treatment, before being released early for good behavior. He was an outcast at first, but the proprietor of the Hoffman House, a loyal friend, gave him a room there and took him in as a partner. He was often seen there at the bar, where a famous painting by the French artist Bouguereau, Satyr and Nymphs, was a must-see for visiting gentlemen. He later quarreled with the proprietor, was involved over the years in various shady enterprises, and died in New York in 1901. He evidently had a wife who divorced him. At the time of his death he was living with another woman who claimed that they had been secretly married a year before.

Edward S. Stokes was tried for murder, but claimed that he had shot Fisk in self-defense, since Fisk had whipped out a pistol and meant to shoot him; Josie Mansfield appeared for the defense. Though witnesses for the prosecution testified that Fisk owned no guns at all, the jury could not agree. At his second trial Stokes was convicted and sentenced to be hanged, but he won an appeal and was tried a third time, convicted of manslaughter, and sentenced to six years in prison. He served four years at Sing Sing, where influence got him lenient treatment, before being released early for good behavior. He was an outcast at first, but the proprietor of the Hoffman House, a loyal friend, gave him a room there and took him in as a partner. He was often seen there at the bar, where a famous painting by the French artist Bouguereau, Satyr and Nymphs, was a must-see for visiting gentlemen. He later quarreled with the proprietor, was involved over the years in various shady enterprises, and died in New York in 1901. He evidently had a wife who divorced him. At the time of his death he was living with another woman who claimed that they had been secretly married a year before.Vilified in New York, Josie Mansfield left the city and, like many an American exile, took up residence in Paris. In 1891 she married an expatriate American lawyer in London, but later divorced him and returned to America. In time she went back to Paris, where she died in 1931, having survived Fisk by almost sixty years, and was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery. The funeral was attended by two servant women and an unidentified third mourner.

Returning to Boston, Lucy Fisk frittered away in bad investments and unwise loans what she had inherited from her husband, and lived from then on in modest circumstances. She died in Boston in 1912 and is buried with her husband in Brattleboro.

So all these people once closely associated with Colonel/Admiral Prince Erie Fisk ended their days shabbily and died obscurely. None of them seems to have had the knack of living meaningfully and well.

Jim Fisk's story cries out to be told -- and retold. It's throughout the blogosphere, there have been biographies and a song, and even an unmemorable 1937 Hollywood movie, The Toast of New York, with Edward Arnold as Fisk, Frances Farmer as Josie, and Carey Grant as a character who, in an unlikely combination, seems to combine Stokes and Gould. Playing fast and loose with historical fact, the film was a commercial flop and lost $530,000. Daniel Meek played Dan Drew.

Jim Fisk's story cries out to be told -- and retold. It's throughout the blogosphere, there have been biographies and a song, and even an unmemorable 1937 Hollywood movie, The Toast of New York, with Edward Arnold as Fisk, Frances Farmer as Josie, and Carey Grant as a character who, in an unlikely combination, seems to combine Stokes and Gould. Playing fast and loose with historical fact, the film was a commercial flop and lost $530,000. Daniel Meek played Dan Drew.Writers have conceived of Fisk's saga as a musical, though none has been produced to date. I know, having once entertained such a folly myself. My only comment, in retrospect: Yuck! (I have another idea for theater -- not a musical -- as well, but more about that another time ... or maybe never.) With Fisk, one major problem is casting. Lots of actors and actresses could do Josie, Stokes, and Gould, but who could do Fisk? I remember Edward Arnold as a splendid character actor in films, but I can't imagine him -- or anyone -- as Fisk. A pity. Jubilee Jim would so relish the thought of getting still more attention!

Source note: For information on Jim Fisk I am especially indebted to W.A. Swanberg, Jim Fisk: The Career of an Improbable Rascal. Anyone wanting to know more about Fisk should read this very readable biography.

Note on the Gay Pride Parade: Last Sunday, a warm, humid day with a threat of rain, was, of course, the annual day of craziness. As usual, our friend John came to share some wine and cheese with Bob and me, after which John and I went out to lunch. We went to our favorite Chinese restaurant, the Empire, on Seventh Avenue just below Greenwich Avenue, avoiding the nearer restaurants because they would probably be jammed. The streets were crowded and the police were out in force directing traffic, but we got our usual ground-floor table by a big window that let us watch those going to and coming from the parade, a spectacle almost as colorful as the parade itself. When we left the Empire it was jammed, with people waiting near the entrance for a table, and outside were two gay guys with outsized fuzzy-wuzzy hairdos, one bright yellow and one bright pink. It was beginning to rain lightly, but we went down Seventh Avenue toward Christopher Street and the parade, whose floats we could seeing passing in the distance to clamorous acclaim, and whose sounds drummed in our ears. On all sides, rainbow flags (small ones stuck in hairdos) and rainbow shirts and T-shirts, blatant colors, and memorable messages on T-shirts: two lesbians walking hand-in-hand with identical T-shirts: I'M HERS and I'M HERS; a gay guy: IT GETS BETTER (the message of older gays to young ones still in school, where peer-group pressure weighs heavily and bullies harass them); and another lesbian: BAM/WOW. As we got near Christopher Street the crowd on the sidewalk was jam-packed, so we decided we didn't need to see more, having watched the parade often in years past. The mood generally was upbeat and celebratory, innocently wild, nothing nasty or confrontational. Back in our apartment, Bob and I anticipated whoops and shrieks into the night, since celebrations don't die fast; it is, after all, only once a year.

New York? No, Tel Aviv, June 2013.

New York? No, Tel Aviv, June 2013.U.S. Embassy, Tel Aviv

Coming soon: Next Sunday, Me and the Seven Deadly Sins, with a glance at this sinful city and the nation, too. After that, Trees on the following Wednesday and something else on the following Sunday. Meanwhile, Happy Fourth to all!

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on July 03, 2013 05:13

June 30, 2013

68. Farewells

p.servus This post is about farewells, both those implying mortality and those that don’t. But let's face it: most farewells imply lasting loss and often death. I’ll start close to home with a relatively conventional farewell. My mother died quietly in her sleep at age 94 – the death that most of us would probably prefer. I didn’t have a chance to say good-bye, but I had phoned her at intervals during the previous year, so I wasn’t haunted by the thought that I’d neglected her. But saying farewell also involves burial and all that goes with it. I flew back to Illinois and my older brother, who lived with her, met me at the airport. “I already feel had by this character,” he said, referring to the funeral director, “so you can be the skinflint from New York.” At the funeral home we were served coffee in the sumptuous parlor, where we were to wait until the director could see us. But the an assistant appeared almost immediately and invited us into the director’s office. “Better take that coffee with you,” said my brother loudly. “It’s the only free thing you’ll ever get in this place!” My brother was not known for subtlety.

p.servus This post is about farewells, both those implying mortality and those that don’t. But let's face it: most farewells imply lasting loss and often death. I’ll start close to home with a relatively conventional farewell. My mother died quietly in her sleep at age 94 – the death that most of us would probably prefer. I didn’t have a chance to say good-bye, but I had phoned her at intervals during the previous year, so I wasn’t haunted by the thought that I’d neglected her. But saying farewell also involves burial and all that goes with it. I flew back to Illinois and my older brother, who lived with her, met me at the airport. “I already feel had by this character,” he said, referring to the funeral director, “so you can be the skinflint from New York.” At the funeral home we were served coffee in the sumptuous parlor, where we were to wait until the director could see us. But the an assistant appeared almost immediately and invited us into the director’s office. “Better take that coffee with you,” said my brother loudly. “It’s the only free thing you’ll ever get in this place!” My brother was not known for subtlety.When the director showed us a bunch of pricey coffins, I assumed – uncomfortably – my role as the skinflint from New York. “Have you any others?” I asked, meaning of course any cheaper ones, though the word “cheap” was not to be uttered. There is in principle a wide range of possibilities, from the most ornate to – if you can find one – a simple pinewood coffin.

This ...? G. Dall'Orto

This ...? G. Dall'Orto

... or this? Nature's Casket Footnote: All right, I cheated just a little, since the ornate casket is a seventeenth-century German one exhibited at the Castello Sforza in Milan, and therefore not readily available. But it shows how fancy a casket can be. As for the simple pinewood coffin, it's the bargain item available from Nature's Casket in Longmont, Colorado. You assemble it yourself. What an adventure -- assembling your own coffin! But it wouldn't cost much, and it's eco-friendly, made with nontoxic materials that are 100% biodegradable. Nature's Casket is part of a growing green burial movement that I have just learned about and heartily approve of.

... or this? Nature's Casket Footnote: All right, I cheated just a little, since the ornate casket is a seventeenth-century German one exhibited at the Castello Sforza in Milan, and therefore not readily available. But it shows how fancy a casket can be. As for the simple pinewood coffin, it's the bargain item available from Nature's Casket in Longmont, Colorado. You assemble it yourself. What an adventure -- assembling your own coffin! But it wouldn't cost much, and it's eco-friendly, made with nontoxic materials that are 100% biodegradable. Nature's Casket is part of a growing green burial movement that I have just learned about and heartily approve of.Now to get back to our story: the director went to another room and came back wheeling a somewhat simpler coffin, but a far cry from basic pinewood. We took it.

The funeral itself was simple enough, attended by just my brother and me, and a cousin and his wife who drove up from Indianapolis. Having on occasion seen funeral processions pass by in the street, I now found myself in my brother’s car at the head of one, right behind the hearse. Yes, I felt strangely conspicuous, but the drive was short. At the cemetery we had planned no final rites, but I suggested that we all scatter on the grave some flowers sent by an old friend in Indiana. Then my cousin gave a brief impromptu speech, thanking my mother for being such a good friend to her younger sister, his mother, long deceased. It was true: the two sisters had been close all their lives, with never a moment of friction that any of us knew of. And so, with the least fuss possible, we said farewell to my mother.

Now for a different kind of farewell. When I was studying in France long ago I got to know a precocious young lycée student named Claude, with whom I shared a passion for literature and learning and a keen sense of humor. (No, it wasn't one of those friendships; we were just buddies.) He had already written a novel, long sections of which he showed me; from them I learned the word pourriture (rot), since that was what his young protagonist (obviously autobiographical) was rebelling against. That summer I visited him in Vichy where, like a good Frenchman, he was taking the waters, and a year later I introduced him to the wonders of hitchhiking in England, where we visited castles and country houses and churches, endured the intermittent rain, and stayed in youth hostels. After I returned to America we kept up our correspondence, and when I retuned to France ten years later there he was, visibly older and now a journalist, ready to travel with me again; on a weekend when he was free, we went to Rouen and visited its churches, then visited various sites of interest in the surrounding area, ending with a sip of cider (not wine, this being Normandy and apple country) in the countryside. After I returned again to the States we sustained our friendship with letters, but gradually, over time, we began to drift apart. Years later, when my partner Bob went to Paris, I asked him to check the Paris annuaire and see if he could find Claude's phone number. He did, and also found his address in the rue des Bernardins, where he had lived for years. But now, when I wrote him to renew the friendship, I got no answer. I sensed frustrations on his part -- he had hoped to be a writer, not a journalist, and had family hangups as well -- and he apparently had little desire to revive our friendship. I felt no such disinclination but had to accept his decision. So at last I sent him a final note: "Je regrette ton silence. Adieu, camarade. Pour ce qui reste, bon courage!" (I regret your silence. Farewell, old friend. As for what remains, have courage!) I expected no answer and got none. With Claude I had shared things I couldn't share with anyone else. So a big chunk of my youth, and of my connection to France, was gone forever. A sad farewell.

Now for a different kind of farewell. When I was studying in France long ago I got to know a precocious young lycée student named Claude, with whom I shared a passion for literature and learning and a keen sense of humor. (No, it wasn't one of those friendships; we were just buddies.) He had already written a novel, long sections of which he showed me; from them I learned the word pourriture (rot), since that was what his young protagonist (obviously autobiographical) was rebelling against. That summer I visited him in Vichy where, like a good Frenchman, he was taking the waters, and a year later I introduced him to the wonders of hitchhiking in England, where we visited castles and country houses and churches, endured the intermittent rain, and stayed in youth hostels. After I returned to America we kept up our correspondence, and when I retuned to France ten years later there he was, visibly older and now a journalist, ready to travel with me again; on a weekend when he was free, we went to Rouen and visited its churches, then visited various sites of interest in the surrounding area, ending with a sip of cider (not wine, this being Normandy and apple country) in the countryside. After I returned again to the States we sustained our friendship with letters, but gradually, over time, we began to drift apart. Years later, when my partner Bob went to Paris, I asked him to check the Paris annuaire and see if he could find Claude's phone number. He did, and also found his address in the rue des Bernardins, where he had lived for years. But now, when I wrote him to renew the friendship, I got no answer. I sensed frustrations on his part -- he had hoped to be a writer, not a journalist, and had family hangups as well -- and he apparently had little desire to revive our friendship. I felt no such disinclination but had to accept his decision. So at last I sent him a final note: "Je regrette ton silence. Adieu, camarade. Pour ce qui reste, bon courage!" (I regret your silence. Farewell, old friend. As for what remains, have courage!) I expected no answer and got none. With Claude I had shared things I couldn't share with anyone else. So a big chunk of my youth, and of my connection to France, was gone forever. A sad farewell.When my friend Ed got cancer of the esophagus -- a very aggressive cancer -- I asked him for a half hour of his time so I could present an alternative perspective on healing, and assured him that, if it didn't interest him, I would never mention it again. I'm not one to proselytize, but knowing how quickly fatal his cancer could be, I decided -- just this once -- to give it a try. Ed listened patiently as I put the case for an alternative treatment, and after a half hour I left, so he could think it over. He never brought it up again, so neither did I. A month later he asked me to escort him on foot to his bank, and a month after that he had me fetch a taxi so he could go to Saint Vincent's (it still existed) for radiation. When I wheeled him into the waiting room and saw all the other patients waiting for treatment, my heart sank, for I knew radiation had many nasty side effects and offered no definitive cure. Several months after that I saw him again into Saint Vincent's, where he told one of his doctors that just taking one short step drained him of energy. "They don't understand," he kept saying, but then, once, to me: "Maybe you understand." "I think I do," I replied, aware that Ed was too tired to want to go on living. A doctors' conference resulted, and they promised Ed that, by rehydrating him overnight, they could replenish his energy. So Ed agreed to stay over. When I and other friends went to see him two days later, one of his doctors told us that a biopsy had found the cancer all through his body; he had only a short while to live. But Ed had indeed recovered his energy and was focused on the practical, giving each of us an assignment; mine was to go to his apartment, get some envelopes and stationery, and put stamps saying LOVE on the envelopes, placing them -- he stressed the importance of this -- upside down. When I delivered the envelopes as requested, it was the last time I saw him. Other friends saw him into a hospice, where he died within a week. So my getting him the envelopes with LOVE stamps placed

upside down -- typical of his sense of humor -- was my farewell. A small gesture, but somehow fitting.

әʌoႨ

Part of a Manhattan farewell is the cleaning out of an apartment. Ed had left his records to my friend John, and his books to another friend of his, and named the two as his executors. To dispose of the records and books they each contacted a dealer who was willing to come and appraise the spoils; as a result, the books brought a thousand dollars, and the records three hundred. That left the furniture and various odds and ends, and to dispose of these they called in what is known as a liquidator to offer a lump sum and take the lot. I had never heard of liquidators until John told me about the transaction; back then one found them in the yellow pages, whereas now one googles them and finds numerous listings, usually promising prospective buyers bargain prices for all kinds of wares. Some obviously prefer to buy up the estates of the affluent, but others deign to take the possessions of those more modestly circumstanced, since these too will find their market.

Lucky are those who die peacefully in the presence of those they loved the most: Sarah Bernhardt in the presence of her son, André Gide with the young man -- by then grown, married, and a father -- who as a boy had become his lover. But not all farewells are peaceful, nor need they come with death. On the radio recently I heard a man tell how, as a freshman in college, he told his family he was gay, and what resulted. They seemed to take it in stride; he went back to college happy. But later he would learn from his sister what had then happened. His mother, the reigning matriarch of the clan, had the family bring together in the back yard all the son's possessions: letters, clothes, photographs, old report cards, everything in his desk, the desk itself and all the other furniture in his room -- in other words, everything relating to the son. This done, she set fire to the pile and watched the blaze that followed, until every last vestige of her son was destroyed. From then on, none of the son's letters was answered, and he slowly came to realize that, because of the mother's action, his bond with his family was severed forever. He tried to see the mother at work, but when she came down the hall and saw him there, she turned on her heel and avoided him. After that a package was delivered to him: a funeral wreath mourning the loss of her son. He never saw her again and years later heard she had died. Perhaps the saddest farewell I have ever heard of.

Our friend Hugh, the cunning waif of vignette #16 (6/17/12), was a gentle soul and a mostly recovered alcoholic, but he still had his quirks and obsessions. Afraid of people yet relating to them well on the phone, for years he had worked as a telephone receptionist, his last job being with a prominent Manhattan law firm that sent him home by limousine to his apartment in the distant nether reaches of Brooklyn. Certainly he was paranoid, so fearful of identity theft that he didn't throw out any correspondence with his name on it, keeping it in his increasingly cluttered apartment for what ultimate disposal I can't imagine. And when a close friend died suddenly, he suspected foul play, though there was absolutely no evidence of it. Furthermore, a hearty meal was an experience almost unknown to him; once retired, he preferred to snack all day on junk food while watching television. Yet for all these eccentricities, he was kind, gentle, sensitive, considerate, never failing to send an amusing birthday card or heartfelt holiday greeting. One of Bob's best and oldest friends, and a good friend to me as well.

Euphoria, maybe. But this stuff can do you in.

Euphoria, maybe. But this stuff can do you in.Alas, time caught up with Hugh. A longtime alcoholic, junk food addict, and user of amyl nitrite and numerous other pills, he had not been kind to his body. His health problems multiplied, yet he had no doctor to oversee his condition and offer treatment. Bob kept me informed, as Hugh deteriorated steadily. Finally one day he phoned us and in Bob's absence I talked to him. "Hugh," I told him, "for God's sake get to a hospital. If you have to, go to an emergency room! Don't wait. Go!" He took the advice and ended up in a hospital in Manhattan, where Bob visited him three times, noting further deterioration at each visit. Hugh's problem was now pneumonia and some other complication, Bob never quite grasped what. The first time he saw him, he had some device inserted into his mouth that prevented him from talking. But he obviously wasn't happy being there, wanted to go home; when he was served a tray of food, with a quick gesture he swept it to the floor. On Bob's third visit he found Hugh heavily sedated and completely out of it. A nurse told him that they had given him two powerful antibiotics, but to no avail; since he had lived on junk food for years, he had no immune system and therefore no defense against opportunistic infections. Soon after that we learned from a visiting cousin that Hugh had died. No funeral; he had arranged to have his remains cremated by the Neptune Society of Medford, New York, the warm ashes to be deposited in the cold Atlantic -- so fitting a conclusion, in Bob's opinion and mine, that we decided to arrange the same with the Society for ourselves.