Clifford Browder's Blog, page 50

October 6, 2013

91. Taylor Mead, Icon and Almost Innocent

Way back in 1959, when I left my spacious Morningside Heights apartment and moved into a shabby little room on West 14th Street, so I could be near the Beatnik scene on McDougal Street, I first encountered him, a thirtyish poet name Taylor Mead who could be seen roaming about the streets clutching a shaggy manuscript to his chest. He was skinny, cleanshaven, and dark-haired, with a long, narrow face and a high forehead, but what most caught my eye was the depraved look he had about him. What do I mean by “depraved”? Over the hill, past the point of no return, lost, lost, lost. When I heard him read at the Gaslight Café, his stuff was mostly unmemorable, but he was not. If he was heckled or interrupted or otherwise annoyed, he screamed at the offender, which settled the matter, since Taylor Mead could outscream anyone. Which encouraged me to keep my distance.

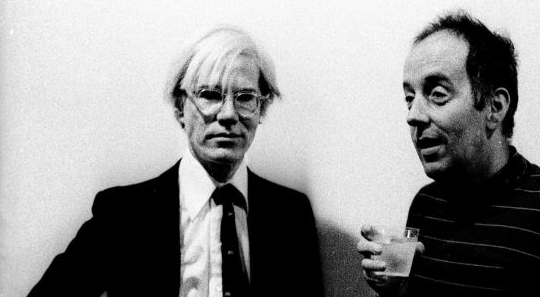

Taylor Mead (right) with Andy Warhol.

Taylor Mead (right) with Andy Warhol. Fast forward a few months to 1960, when I had followed the Beatnik scene and my own restlessness out to San Francisco and settled into a small room in an SRO on Broadway, conveniently near to Chinatown for cheap meals, and to North Beach and the Beatniks. Attending a poetry reading with my newfound friend Floyd at the Mission, a welcoming place on Grant Street run by a young minister who served a free meal once a week and otherwise catered to the Beats, I saw Taylor Mead again, the same lost look, the same shaggy manuscript pressed tight to his chest.

“I know that guy,” I told Floyd, meaning of course that I knew ofhim. “I heard him read in New York.”

When Taylor Mead plunked himself down on a chair right behind us, Floyd, with a sly grin, turned to him and said, “Hi there! My friend here heard you read in New York. He loves your stuff.”

Taylor Mead flashed instantly the warmest smile. “Why, thank you. My poetry isn’t just surface. It has real meaning, it has depth.”

To date, I hadn’t sensed much depth in his poems, just a lot of ragged surface. But this was a different Taylor Mead: relaxed, not defensive, even charming.

I don’t recall if Taylor Mead read at that reading, but soon afterward I heard him read at the Co-existence Bagel Shop, the chief Beatnik hangout of the time, where Beats and tourists mingled cheerily, or not so cheerily. Taylor’s first line was memorable: “I was a cocksucker in Arcady…” What followed I barely recall; that first line was hard to top. Mostly I remember a passing reference to his wealthy father, against whom he was obviously in vehement revolt. But I also recall the comments of those around me.

Two well-dressed men of middle years, obviously out of their element. “He’s not that good,” one said, softly. “I’ve heard homosexuals of real talent read.” His friend concurred.

“Give him a chance,” said a black man. “He’s doing his best.”

Overhearing them, a woman remarked, “In this place I keep my opinions to myself.”

The next I knew of Taylor Mead was once again at the Mission, where a fragment of a film in progress was shown, with pleas for contributions so the fund-strapped project could be finished. It was an amateurish effort in black and white, though not without charm, featuring Taylor wandering haphazardly through the city. The high point came when, at one point, his pants dropped, exposing his bare bottom; the audience roared. I don’t recall if I was inspired to donate; I rather doubt it.

That summer I went to Mexico and, returning to San Francisco, I found that most of the Beats had decamped. By then I had tasted of their scene sufficiently to know that it wasn’t for me; I’m too neat, too practical, too work-oriented. But from them I had learned both positive and negative lessons, one being, in the words of a knowledgeable friend who had also tasted of bohemia, “Get to know these people a little, learn from them, but don’t let them into your life. They can destroy you!”

The unexpected offer of a teaching job brought me back to New York and I saw Taylor Mead no more. So what was my final impression of him at that time? An aging adolescent given to temper tantrums but also capable of charm. He needed attention, craved it, was irate if he didn’t get it. A lost soul, almost an innocent, but a calculating innocent, if such a thing can be. And certainly a free spirit, but paying a price for it. I assumed he was on some kind of drug, didn’t think he’d last to enjoy a ripe old age.

Fast forward fifty-three years to today. Imagine my surprise when, researching my recent post on the Bowery, I went to the website of the Bowery Poetry Club and encountered the name of Taylor Mead, who had often read his poetry there. Clicking on a link, I learned that, a longtime resident of the Lower East Side, at age 88 he had died in May of this year during a visit to a niece in Denver and had received obits in the New York Times and Los Angeles Times and numerous blogs that hailed him as a poet, actor, exuberant bohemian, and star of underground films. “An elfin figure with kewpie-doll eyes,” said the L.A. Times. (Elfin perhaps, but I never noticed the kewpie-doll eyes.) Imagine too my shock on seeing recent photos of him: the skinny young poet with a depraved look had turned into a little old man, wrinkled and bent, who walked with a cane, an old man capable of smiles but who, far from exposing his anatomy, was well bundled up even in mild weather. So he had survived into old age and was even older than me! I then went on to learn more about him so as to update and correct my earlier impression; what I learned follows here.

Taylor Mead was born in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, a Detroit suburb that, as a Midwesterner, I know to be an enclave of the rich and privileged. His father was a wealthy businessman and influential figure in the Democratic Party in Michigan, and his mother a socialite; they divorced before he was born. He endured a private high school (“brainwashing for the bourgeoisie,” he later termed it), and, through his father’s influence, got a job with Merrill Lynch in Detroit, but soon found that he had no inclination for finance. Taylor Mead at Merrill Lynch -- the very idea boggles the mind! He soon left, and left Detroit as well, needing to put space – a lot of it – between himself and his family. Knowing from the age of 12 that he was gay probably had a lot to do with it.

I won’t recount every phase and detail of his life; that can be left to a future biographer. Having read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and, inspired by it, hitchhiked across the country more than once, he came to New York to be anonymous, to have a private life. By this, I think he meant to live freely, as he could not do back in Michigan. Which reminds me how Quentin Crisp, author of The Naked Civil Servant, came here decades later to live more freely than he felt he could in his native England. (A future post will “do” Quentin Crisp.) But Taylor Mead wanted only a degree of anonymity. His whole life and career were fueled by a desperate desire for attention; he took to notoriety as a wasp takes to jam.

When I first encountered him in New York in 1959, he was reading his poetry in bars and coffee houses, but he had yet to achieve real fame. When I encountered him again in North Beach, San Francisco, in 1960, his career as an underground film performer was beginning. The fragment of film I saw him in was obviously the first segment of The Flower Thief, an experimental low-budget black-and-white film using war surplus film stock and a hand-held camera, and directed by Ron Rice. Taylor says of Rice that he was stealing his girlfriends’ support checks, running off with theater receipts, and chasing people down the street trying to film them, but that everybody loved him. In the film Taylor, a bedraggled Chaplinesque innocent, wanders around the city with three precious possessions: a stolen gardenia, an American flag, and a teddy bear. Hardly acting, he is playing himself. Film historian P. Adams Sitney called the film “the purest expression of the Beat sensibility in cinema.” According to Taylor, he and Rice were to split the proceeds of the film 50/50, but Rice eloped with all the money.

After that Andy Warhol “discovered” him and, back in New York, he began starring in Warhol’s underground films. In the first one, Tarzan and Jane Regained … Sort Of (1964), Taylor played – unbelievably – the heroic Tarzan, whose sarong kept falling off as Tarzan was climbing trees, prompting one critic to state that he did not care to see any more two-hour films of Taylor Mead’s behind. The star and Warhol then searched the Warhol archives and, finding no such film, decided to rectify the matter. The result was Taylor Mead’s Ass (1964), an hour-long silent epic of the star performing just with that part of his anatomy. I haven’t seen it, but it should now be obvious why underground films stay underground. (Taylor himself later remarked, “Only a sicko would watch the whole thing.”) During the 1960s he made eleven films with Warhol, their collaboration ending in 1968, when a radical feminist writer who had grievances against Warhol shot and seriously wounded him.

Taylor on the Tarzan set with Dennis Hopper. Taylor was a very winsome Tarzan.

Taylor on the Tarzan set with Dennis Hopper. Taylor was a very winsome Tarzan.In 1966, while living in Europe (how financed? one wonders), Taylor heckled a Living Theatre performance in Southern France that he found “communal to the point of sameness.” Irritated by actor and cofounder Julian Beck’s repetition of “End the war in Vietnam,” Taylor began shouting “A bas les intellectuels!” and “Vive la guerre de Vietnam!” (A future post will “do” the Living Theatre as well.)

Subsequently Taylor made numerous other underground films, some of them so spontaneous that they involved only one take. Always he was playing himself, since his art was his life, and his life was his art.

Note on me and Andy: I saw several Warhol films back in the 1960s, though none with Taylor Mead. They were unstructured, haphazard, a series of improvisations. There were some charming and humorous moments, but in general they violated the Supreme Commandment of Performing Arts: Thou shalt not bore.

The obits and online sources are curiously silent about the next thirty years, so that a big middle chunk is missing from the arc of Taylor’s life. In addition, one wonders about how he supported himself (even a legend has to pay rent), and about his sex life. Fame was what Warhol offered him, not cash. He evidently got a little income from his father’s estate – just enough to survive on -- and as for sex, he probably reaped it haphazardly, being too much in love with himself to sustain a long-term relationship. In the 1970s Gary Weiss made some short films of him talking to his cat in the kitchen of his Ludlow Street apartment; one of the films, in which he expatiated on the virtues of constant television watching, was later aired on Saturday Night Live.

Certainly Taylor Mead became a beloved icon of the Lower East Side, where he lived for years in a rent-stabilized fifth-floor apartment at 163 Ludlow Street. He read his poetry in various venues, took up painting and got his work shown in various galleries, and fed stray cats in a Second Avenue cemetery and elsewhere during his nocturnal prowls. The snippets of his poetry that I’ve seen online are prosy and rambling, and rich in non sequiturs and four-letter words – in other words, just what you’d expect. As for his paintings, they seem to have been bold and splotchy.

Though a nonsmoker and vegetarian, he did drugs like the opiate Vicodin, but seems to have kept free of the heavy stuff so prevalent in the Warhol entourage. Having a great propensity for booze, he hung out in bars where he sometimes got free drinks. His block was full of drug dealers, but the dealers in and around his building looked out for him when he came home drunk at 4 a.m., or when he went out in the early morning hours to feed the cats. Some minor strokes finally limited his walking, so he had to give up feeding felines, turning the task over to an elderly lady. But he loved his neighborhood, drugs and all; when he went out, people always recognized him and said hello, and young people helped him out of cabs and up the stairs. When the Bowery Poetry Club opened in 2002, he read there regularly, amusing audiences with his vivid comments on sex, death, genius, and himself. He was also, it would seem, a clutterbug. William Kirkley’s 2005 documentary Excavating Taylor Mead shows him trying to clean up his apartment, crammed with the ephemera of his colorful life, including thousands of loose manuscript pages and his vivid paintings, so as to avoid eviction by the city authorities, who had probably condemned it as a firetrap. In the same year his volume of poetry A Simple Country Girl was published, with the memorable line, “I am a national treasure / If there were such a thing.” Not everyone who encountered him hailed him as a beloved icon or a treasure. When someone pointed him out to a friend of mine at a gathering circa 1970, my friend’s reaction was, What is that? And novelist and poet Eamon Loingsigh has told of entering a dark Lower East Side bar one afternoon a few years ago and finding “an old, creepy looking man leaning on the bar, crouching like a frail spider among a few smarmy-dressed women.” The spider screeched at times, sipped his beer, flirted with the newcomer, and called for champagne, but the bartender merely smiled. The spider was obviously the center of attention, his wit and spontaneity eliciting cackles from the fiftyish ladies. The visitor thought the old man’s face looked familiar, but he couldn’t quite place him. Loingsigh left the bar after an hour and only later, seeing some Warhol films, did he recognize the screeching spider as a young man and realize that he was Taylor Mead.

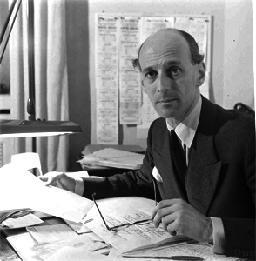

Taylor in his Ludlow Street apartment, March 2013, minus heat.

Taylor in his Ludlow Street apartment, March 2013, minus heat.Clayton Patterson

Taylor’s last months in New York were consumed by a battle with his new landlord, who was converting all the other apartments in the building to market-rate rentals. Taylor clung to his home of thirty-four years, where he paid only $380 a month, while workers hammered outside his door from 7 a.m. until evening, and plaster fell from the walls, roaches crawled up his legs, and the kitchen sink didn’t work. Finally, no longer able to navigate the stairs, he agreed to move out in return for a financial settlement. He then went to stay with a niece in Denver, but was planning a trip to New Orleans and ultimately a return to New York when he succumbed to a stroke.

So where do I end up? I don’t think my initial take on Taylor was wrong, except for doubt that he would make it to a ripe old age. He was an exhibitionist and narcissist for sure, a free spirit and perhaps a lost soul, but in the losing he found himself, he became Taylor Mead. An almost innocent of considerable charm who both took himself very seriously and chuckled at his own quirks and pretensions. Said Susan Sontag in Partisan Review, “The source of his art is the deepest and purest of all: he just gives himself, wholly and without reserve, to some bizarre autistic fantasy. Nothing is more attractive in a person, but it is extremely rare after the age of 4.” Yes, Taylor Mead gave himself and in so doing became the one and only thing that mattered to him, his chief object in life and supreme accomplishment: Taylor Mead. I too mourn his loss.

Unless, of course, a biographer comes along, peels away the legend, and reveals some raw, hard truths.

Coming soon: Rediscovering New York: West 12th Street and Columbus Circle; and Brooke Astor, Aristocrat of the People. In the works: Quentin Crisp, the Living Theatre; personal anecdotes or impressions concerning either are welcome.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on October 06, 2013 05:18

October 2, 2013

90. The Bowery: From B'hoys to Bums to Condos

The street known as the Bowery runs north from Chatham Square at Park Row in Lower Manhattan to Cooper Square at East 4th Street, though it once was considered to end at Union Square, where it met Broadway. It has a long history with many phases, more really than Broadway or Wall Street.

Peter Stuyvesant, a statue by

Peter Stuyvesant, a statue byGertrude Vanderbilt Whitney,

1941, in Stuyvesant Square. Originally it was a Native American path spanning the entire length of the island of Manhattan. When the Dutch came and founded New Amsterdam, they named it the Bouwerij, an old Dutch word for “farm,” because it connected farms and estates outside the city wall to the settlement at the southern tip of Manhattan. In 1651 Peter Stuyvesant, the last governor of the Dutch colony, bought a large farm that, supplemented by additional purchases, came to 300 acres bounded by what is now 17th Street on the north, the East River on the east, 5th Street on the south, and Fourth Avenue on the west. When, over his objections, the colony surrendered to the British in 1664, he retired to this estate, died there in 1672, and was buried in the floor of his private chapel.

Momos But that’s not the end of Old Silver Leg, as he was sometimes called because he wrapped his wooden leg in silver bands to strengthen it. His descendants lived on in the area, and in 1778 his great-grandson sold the crumbling chapel and graveyard to the Episcopal Church. On this site, in 1799, the church of St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery was built, with the family vault holding the governor’s remains under its east wall. From then on there were reports of a one-legged ghost stalking about, its peg leg going clop clop clop on the floor, and of the church bell being rung by unseen hands. The old governor was evidently still angry about the colony’s surrender and resented as well the disturbance of his remains. These reports continued into the twentieth century and beyond; in 2002 the clop clop clop of his wooden leg was once again allegedly heard in the church.

Momos But that’s not the end of Old Silver Leg, as he was sometimes called because he wrapped his wooden leg in silver bands to strengthen it. His descendants lived on in the area, and in 1778 his great-grandson sold the crumbling chapel and graveyard to the Episcopal Church. On this site, in 1799, the church of St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery was built, with the family vault holding the governor’s remains under its east wall. From then on there were reports of a one-legged ghost stalking about, its peg leg going clop clop clop on the floor, and of the church bell being rung by unseen hands. The old governor was evidently still angry about the colony’s surrender and resented as well the disturbance of his remains. These reports continued into the twentieth century and beyond; in 2002 the clop clop clop of his wooden leg was once again allegedly heard in the church. In the eighteenth century the dusty road known as Bowery Lane ran past farms, several owned by Stuyvesants, and past gentlemen’s estates. A small community named Bowery Village sprang up with a few houses, a blacksmith, a wagon shop, a general store, and a tavern. By the early 1800s, as the city expanded steadily northward, the village attracted more wagon stands, shops, groggeries, an oyster house where post riders could leave mail, and a brothel, in spite of which respectable residences were also built. Clearly, change was coming, as evidenced in 1812, when Third Avenue was cut through Stuyvesant property, and old roads were closed and the houses on them removed or demolished. The Stuyvesants resisted bitterly and managed to save a few homes, but the neighborhood, no longer rural, was subjected to the Commissioners’ rigid grid plan designed for all of the island of Manhattan.

The junction of Broadway and the Bowery at 14th Street, 1831. What is now Union Square.

The junction of Broadway and the Bowery at 14th Street, 1831. What is now Union Square.As the years passed, the Bowery, sometimes paved with cobblestones and sometimes with gravel, became a broad avenue paralleling and rivaling Broadway. But in spite of a few fine residences, the street soon became a commercial and entertainment center for the working classes, in effect a poor man’s Broadway. In 1836 the Bowery Savings Bank was established at 130 Bowery to serve the workers in the area, where there was no other bank. Lining the avenue by the 1840s were saddleries, stove shops, druggists, jewelers, candy and peanut vendors, pawnshops, junk shops, oyster stands, taverns, livery stables, and clothiers who spread their wares out on the sidewalk. Thronging that sidewalk were pleasure-seeking sailors, sleek-haired young butchers, flashy girls, bullies from the slums, and, peddling to the lot of them, black women offering baked pears, or hot yams cooked over charcoal fires, or hot corn ladled out of cedar pails filled with steaming water. Already the street was being hailed by some as the most democratic scene in the city, and even the most Christian. If a fellow who had seen better days showed up there in a torn coat and battered hat, no one thought the worse of him, since they or their friends had all been there as well, and might be there again.

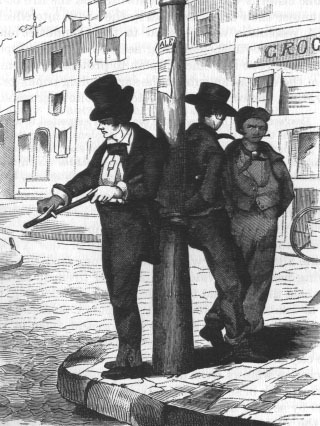

Prominent among the Bowery denizens was the Bowery B’hoy, known at a glance by his loud clothes, often the red flannel of his volunteer fire company, and by his soap-greased sidelocks topped by a stovepipe hat set at a rakish angle, with a cigar or chaw in his mouth, a black silk tie, and high-heeled calfskin boots. A butcher or mechanic by day, or a shipbuilder or carpenter or unskilled laborer, at night and on holidays he swaggered down the Bowery as if he owned it, which in a sense he did, or leaned against a lamppost with the same unmistakable air of possession. Everything about him proclaimed his rowdy independence, his hate of pretense, his disdain for bourgeois sobriety. Good-humored, loyal to his friends, and fiercely protective of his girl, he believed in fair play and a boisterous brand of chivalry, wasn’t a thug or a bully, but was always ready for a fire, a fight, or a frolic. For entertainment he was partial to prize fights and dog and cock fighting, but nothing delighted him more than a fire alarm. Hearing one, he rushed to join his volunteer fire company and help haul their engine to the scene of the fire, clashing with any rival company that got in the way, but often performing rescues of great courage and daring.

Matching him in independence was the Bowery Gal, a working girl who in her off hours sashayed along the Bowery with a swinging gait. Her gaudy bonnet trimmed with an exuberance of flowers, feathers, outsized bows, and ribbons, plus the clashing colors of her clothing, and her short skit revealing a well-turned ankle, proclaimed her the very opposite of the well-mannered young middle-class lady, who was schooled to be proper, modest, tasteful, and demure. One journalist of the time discerned in the Bowery Gal and her male counterpart the most original and interesting phase of human nature yet developed by American society.

Catering to the rowdy working-class denizens of the Bowery was the Bowery Theatre, which opened at the corner of Canal Street and the Bowery in 1826 and survived numerous fires, being rebuilt each time and lasting well into the twentieth century. Women and children and the less hardy patrons took refuge in the gallery, leaving the pit to the boisterous males who, when the doors opened, rushed in like a horde of unchained demons. If any stranger was so misguided as to claim the seat of a regular, the B’hoys lifted the offender bodily over the heads of the crowd and passed him to the rear of the theater.

The Bowery Theatre in 1846.

The Bowery Theatre in 1846.The fare offered at the Bowery was primarily melodrama, with heroes rescuing damsels in distress from the clutches of villains who died wretchedly and deservedly, with jerks, spasms, and groans, to the appropriate cheers and hisses of the audience. If the curtain failed to go up on time, whistles and stomps erupted, and shouts of “H’ist dat rag!” But if the play ended satisfactorily, no audience ever produced such thunderous applause. That applause reached a new level of enthusiasm in 1848, when the actor Frank Chanfrau introduced the character of Mose, the Bowery Boy incarnate, whom the audience at once recognized and cheered obstreperously. Mose soon became a legendary theatrical figure, assuming the prowess and proportions of a Paul Bunyan in his ever greater and more fantastic exploits.

A performance at the Bowery Theatre, 1856.

A performance at the Bowery Theatre, 1856.By the 1850s a great influx of Irish and German immigrants added new colors to the Bowery scene, with half the signs in German, since Germans settled in large numbers on the Lower East Side. On Sundays whole German families flocked into the beer gardens for a day of entertainments, singing, dancing, and feasting: a total contrast with the Irish saloons and their strictly male clientele who met there for conviviality before trudging homeward to the realities of spousedom.

Saturday night on the Bowery, 1871. But to really know the Bowery one had to see it on Saturday night, when it was ablaze with gaslight from red and blue and green glass globes, while horsecars passed with colored lights and jingling bells, and working-class men surged along the sidewalks looking for fun and entertainment. Music and laughter issued from the dance halls, and the crackle of rifle fire from shooting galleries, while on the sidewalk small German bands played waltzes, organ grinders presented their gaudily clad monkeys, and black quartets sang spirituals. Vendors hawked hot corn and oysters, theaters offered melodramas and musical extravaganzas and French opera bouffé, and dime museums enticed passers-by with mechanical contrivances, flea circuses, and wax figures representing famous events and lurid crimes. Whatever distractions a young working man might desire on his night off were available there, and cheap. Yes, there were abundant drunks and whores, and gang fights on occasion, and even a riot now and then, but the Bowery had a life all its own, unmatched by any other scene in the city. It was raw, undisciplined, and free, it was rambunctiously alive.

Saturday night on the Bowery, 1871. But to really know the Bowery one had to see it on Saturday night, when it was ablaze with gaslight from red and blue and green glass globes, while horsecars passed with colored lights and jingling bells, and working-class men surged along the sidewalks looking for fun and entertainment. Music and laughter issued from the dance halls, and the crackle of rifle fire from shooting galleries, while on the sidewalk small German bands played waltzes, organ grinders presented their gaudily clad monkeys, and black quartets sang spirituals. Vendors hawked hot corn and oysters, theaters offered melodramas and musical extravaganzas and French opera bouffé, and dime museums enticed passers-by with mechanical contrivances, flea circuses, and wax figures representing famous events and lurid crimes. Whatever distractions a young working man might desire on his night off were available there, and cheap. Yes, there were abundant drunks and whores, and gang fights on occasion, and even a riot now and then, but the Bowery had a life all its own, unmatched by any other scene in the city. It was raw, undisciplined, and free, it was rambunctiously alive.Nineteenth-century New York was perennially in flux, and the Bowery was no exception. In 1878 the Third Avenue El began operation, running from Chatham Square north over the Bowery and then over Third Avenue all the way to 129th Street. Nighttime riders could glance into second- and third-floor interiors, where they might see a family at a late meal, a woman sewing by a lamp, or a girl and her boyfriend leaning over a windowsill, but anyone on the street below had a less magical experience. Not only did the El line darken the street, but it also made a screeching noise and showered pedestrians with oil drippings, soot, and hot cinders.

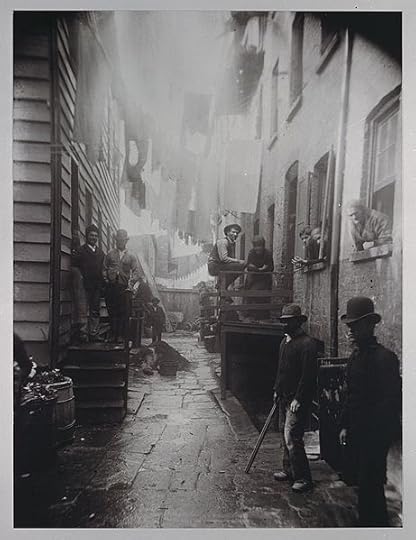

The Bowery, 1896.

The Bowery, 1896.Equally significant was the founding in 1879 of the Bowery Mission at 14 Bowery, seeking to provide food and shelter to the homeless men of the neighborhood. The Mission, still in operation today, continued at various addresses on the Bowery, which was becoming more and more the haunt of down-and-outers, with flophouses and cheap restaurants and clothing stores catering to them, as well as cheap saloons. By the 1890s prostitutes abounded, as well as bars and dance halls for “degenerates” and “fairies,” who found a working-class neighborhood more tolerant than middle-class neighborhoods elsewhere. But if they fled middle-class gentility, that gentility began pursuing them as respectable citizens went “slumming,” making daring forays into this realm of outcasts and the damned.

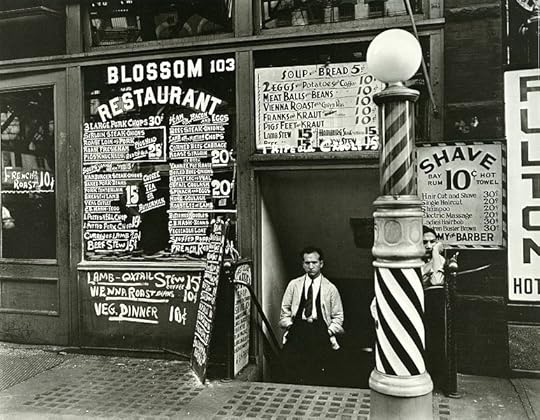

Blossom Restaurant at 103 Bowery, 1935. Notice the Depression prices: 3 pork chops, 30¢;

Blossom Restaurant at 103 Bowery, 1935. Notice the Depression prices: 3 pork chops, 30¢;beefsteak onions, 20¢; veg. dinner, 10¢; shave, 10¢. Ah, the good old days!

In the early twentieth century the Bowery became notorious as the Skid Row of New York, and the most famous one in the nation; in 1907 the population of its flop houses, missions, and cheap hotels was estimated at twenty-five thousand. The Depression of the 1930s only made matters worse. And yet, by way of contrast, the Bowery from Houston to Delancey Street became the city’s chief market for lighting fixtures and lamps, and from Delancey to Grand Street its chief market for bar and restaurant equipment, markets that are still there today.

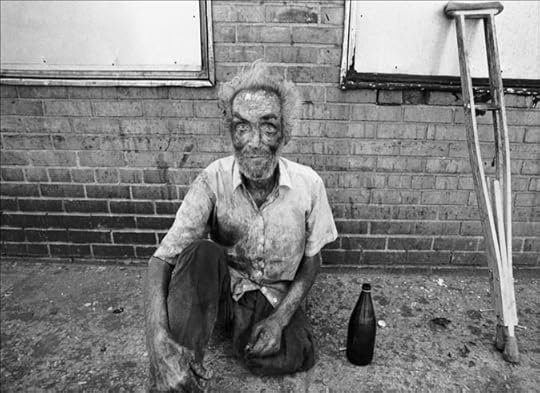

On the Bowery, 1977.

On the Bowery, 1977. Gerhard Vormwald When I came to New York in the 1950s, mention of the Bowery meant only one thing: hopeless drunks and down-and-outers, bums. But even then there was more to the street than that. In the late 1960s my newfound partner Bob took me to Sammy’s Bowery Follies, a unique joint at 267 Bowery that was part dive, part tourist trap. What I chiefly remember is feisty women in garish outfits singing feisty songs; it was fun.

Sammy’s was past its prime by then, having been founded in 1934 by Sammy Fuchs first as a run-of-the-mill saloon, but then, in a spurt of inspiration, as a cabaret that he proclaimed “the Stork Club of the Bowery.” In its heyday Sammy’s, with its packed sawdust floor and Gay Nineties pictures and photos of prize fighters on the walls, drew drunks and celebrities alike, skylarking sailors and local down-and-outs, the rich and the forgotten, all of them rubbing elbows in a Gay Nineties-style bar while reborn vaudeville has-beens belted out songs. It got so famous that tour buses rolled up and sent their occupants thronging in for a brief taste of how the other half lives. But in time its glory faded, and in 1970, a year after Sammy Fuchs died, it closed its doors. Sitting at the bar on that last night were Prune Juice Jenny, Box Car Gussie, Juke Box Katie, and Tug Boat Ethel, all mourning the loss of a beloved hangout.

Ethel, the Bowery Queen, at Sammy's.

Ethel, the Bowery Queen, at Sammy's.Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

Another sign of change was the demise of the Third Avenue El. The Depression had brought decreased ridership for all the elevated lines, and Mayor La Guardia decided to eliminate them so as to raise property values. The Third Avenue El ceased service on May 12, 1955. My partner Bob was a longtime fan of the line, which he rode sometimes to get somewhere and sometimes for the sheer fun of it. With many likeminded veterans of the El, most of them casting mournful looks and some of them swigging champagne, he rode on the very last train from Chatham Square to 34th Street, where he got off because of the crowds now jamming the train. Property values may well have soared, but a bit of old New York was gone, never to return.

But the Bowery never quite dies and always resuscitates. In 1964 Anthony Amato established his Amato Opera at 319 Bowery, near 4thStreet, where it flourished for thirty-five years, presenting mostly French and Italian operas on a postage-stamp stage; in recent years Bob and I attended many. And in 1973 the music club CBGB moved into 315 Bowery, just a few doors away, to offer hard core punk, then rock, folk, and jazz to enthusiastic audiences. Meanwhile the Bowery’s vagrant population was declining, partly because of the city’s effort to disperse it. Decidedly, the Bowery was on an upswing, leaving its Skid Row image behind.

Adam Di Carlo

Adam Di Carlo The Bowery Hotel

The Bowery HotelBeyond My Ken

Today the Bowery is definitely undergoing gentrification, as high-rise condominiums appear, plus an upscale food market and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, as well as curio shops, art galleries, a poetry club, celebrity lounges, and the luxurious Bowery Hotel, offering 24-hour room service, valet parking, a fitness room, spa services, and many other amenities. (But does Manhattan really need another luxury hotel?) So the elite no longer come on quickie slumming tours; they come to visit and to stay. What would the Bowery B’hoy of yore think of spa services and a fitness room? His comment would be unprintable. There are still some flophouses and the Bowery Mission, so the street’s reputation for a mixed population endures. But gentrification winning out with a vengeance.

Bank note: The founding of the Bowery Savings Bank to service the workers of the Lower East Side, recounted earlier, is a reminder that banks once served the public and not just themselves. Many nineteenth-century New York banks had names indicating the specific clientele they meant to serve: the Butchers’ and Drovers’ Bank, the Importers’ and Traders’ Bank, the Merchants’ and Clerks’ Bank, the Seaman’s Bank for Savings. Quite a contrast with the big banks of today, as for instance my beloved J.P. Morgan Chase, now under siege from regulators for various peccadillos, among them a whale of a trading loss in London. So far the CEO, Mr. Jamie Dimon – a handsome and distinguished gentleman, to judge by photos in the papers – has survived, his bonuses intact. But for the sins of the higher echelons I do not blame the employees at my branch, cordial and friendly minions dispensing the warmest greetings and an abundance of candy. The candy I eschew (there’s that word again, resounding like a sneeze), but I could use a few more pens; alas, they are nowhere in sight.

Coming soon: Next Sunday, Taylor Mead, Icon and Almost Innocent (a free spirit whom I experienced long ago and rediscovered recently). In the works: Brooke Astor, an aristocrat of the people ("Money is like manure; it's not worth a thing unless it's spread around"); Quentin Crisp (another free spirit who realized himself most fully here in New York); and the Living Theatre (I endured and survived their freewheeling productions and indecent exposure).

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on October 02, 2013 05:52

September 29, 2013

89. Who Really Runs America? David Rockefeller?

On WBAI recently (where else?) I heard nutritionist Gary Null, who also comments on current affairs, expound seriously on a vast conspiracy of corporate and military powers who constitute a shadowy permanent government of this country and really rule it, our elected officials being their pawns or dupes. Prominent among these sinister figures he named David Rockefeller, the aging patriarch of that clan, whom I and many know only as the banker brother of the late Nelson Rockefeller, the forty-ninth governor of New York State (1959-1973) and the forty-first vice president of the U.S. (1974-1977) under President Gerald Ford.

Having heard vaguely of such theories before, I decided to look into David Rockefeller and his possible implication in such a conspiracy. I am no friend of conspiracy theories but cannot deny that important things happen that we ordinary citizens only learn about later, if even then. So who is David Rockefeller and what has he been up to? I launch my little investigation with no expertise whatsoever and with access only to information available to the public.

He was of course a banker, and this makes him suspect at once. We Americans profess to dislike bankers, since we think of them as fat cats with too much money who are not inclined to share it with the rest of us who have too little. This prejudice – and it is a prejudice – has seeped deep into our popular entertainments. Long ago, when the soaps were making their last stand on radio, I recall how, when the writers of Ma Perkins needed a villain in the little town of Rushville Center, they trotted out the local banker, who was referred to not as Mr. So-and-So, but Banker So-and-So. And our recent financial convulsion and its ongoing aftermath, brought on in large part by misbehaving banks, haven’t exactly enhanced the profession’s reputation. Still, with noble intent I shall push this bias to one side and proceed as objectively as possible. So what kind of a guy is David Rockefeller, and what are his connections to this alleged conspiracy?

A sitting room at 10 West 54th Street.

A sitting room at 10 West 54th Street.Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

He is a son of John D., Jr., who, as I mentioned in a recent post, built Rockefeller Center at his own expense, and a grandson of old John D., the Standard Oil mogul and founder of the family fortune. David was born in New York City in 1915 in his father’s sumptuous residence at 10 West 54thStreet, then the largest private residence in the city, and one full of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance art collected by his father, not to mention a whole floor devoted to his mother’s private modern art gallery. In his bedroom at one time were the famous Unicorn Tapestries now at the Cloisters museum in Fort Tryon Park, near the northern tip of Manhattan.

Much of David Rockefeller’s childhood was spent at Kykuit, a 40-room neoclassical mansion on a 250-acre family estate near Sleepy Hollow in Westchester County, N.Y., where he recalls visits by General George C. Marshall, Admiral Byrd, and Charles Lindbergh. And for summer vacations there was the family’s 100-room house on Mount Desert Island, Maine. Yes, a privileged childhood with wealth and connections right from the start, though he and his siblings were raised strictly, as his father had been before him.

Kykuit, seen from the south.

Kykuit, seen from the south.Gryffindor

The Rockefellers and art: David Rockefeller’s father, John D., Jr., was a passionate collector of traditional art of the past, while his wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (David’s mother), was just as passionate a collector of modern art, which her husband professed to despise. She was one of the founders of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in 1929, and persuaded her husband to donate land on 53rdand 54th Street for the present MOMA, which opened in 1939. To make room for the new museum, John D., Jr., demolished both his sumptuous residence at 10 West 54th Street, and his deceased father’s palatial mansion at 4 West 54th Street; in their place today is the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The Rockefellers have been affiliated with MOMA ever since. But if Abby’s modern art collection found a home at MOMA, her husband’s medieval collection went to the Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

His education: He graduated cum laude from Harvard, did postgraduate work in economics there and at the London School of Economics, and got a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, his dissertation entitled “Unused Resources and Economic Waste.” My take so far: this was no playboy, and no slouch either. He had a mind and put it to good use.

For eighteen months he served as secretary to Mayor Fiorello La Guardia at a dollar a year, and then worked for the U.S. Office of Defense, Health, and Welfare Services. When we entered the war he attended Officer Candidate School and became an officer in the Army, working in North Africa and France (he spoke fluent French) for military intelligence. Serving as well for seven months as an assistant military attaché at the U.S. embassy in Paris, he made use of family and Standard Oil contacts and established contacts of his own that proved useful thereafter. Even so, an exemplary career and nothing that I find objectionable. In the military as in business, there’s nothing inherently wrong with developing a network of contacts.

In 1946 he went to work for the Chase National Bank, with which his family had long been associated. Beginning as a lowly assistant manager, he worked his way up through the ranks, developing relationships with correspondent banks throughout the world, and finally became president and CEO. In 1955 he persuaded the bank to erect its new headquarters in the Wall Street area, thus helping revitalize the downtown financial district, which other companies had deserted for locations farther uptown. In 1960 the new sixty-story building opened at One Chase Manhattan Plaza on Liberty Street, then the biggest bank building in the world.

Under David Rockefeller’s leadership Chase spread internationally and became a major force in the world’s financial system, with some fifty thousand correspondent banks, more than any other bank in the world. He even opened a branch at One Karl Marx Square near the Kremlin and established relations with the National Bank of China. Trouble came in 1979 when, along with his friend Henry Kissinger and others, he persuaded President Jimmy Carter to admit the deposed Shah of Iran for hospital treatment in the U.S., an action that precipitated the Iran hostage crisis and brought him under media scrutiny for the first time in his life.

Now a major political and financial figure and a moderate Republican, he had relations with every U.S. President from Eisenhower on, and at times served as an unofficial emissary on high-level diplomatic missions. In 1968, when Robert Kennedy was assassinated, his brother Nelson, then Governor of New York, wanted to appoint David Rockefeller to the vacant senate seat, but he turned the offer down. Subsequently President Carter offered to make him Secretary of the Treasury and Federal Reserve Chairman, but he turned those offers down as well. Clearly, with all his worldwide contacts he preferred a private role, well removed from the publicity and brouhaha of politics. Which of course has made him a natural target for conspiracy theorists of every stripe and hue.

A young David Rockefeller with Eleanor Roosevelt,

A young David Rockefeller with Eleanor Roosevelt,Trygvie Lie, the first Secretary General of the U.N.,

and IBM CEO Thomas J. Watson, 1953.

His contacts over the years included Henry Kissinger, a personal friend; Allen Dulles and his brother John Foster Dulles; former CIA director Richard Helms; Archibald Roosevelt, Jr., and his cousin Kermit Roosevelt, both involved with the CIA; and countless others. Who, indeed, didn’t he know among the rich and powerful? All of which, again, has made him a natural and inevitable target for conspiracy theorists.

Throughout his life he was involved with numerous policy groups that were concerned with domestic and international problems: the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; the International Executive Service Corps, promoting prosperity and stability through private enterprise in underdeveloped regions of the world; the Partnership for New York City, a group of CEOs seeking to promote the city as a global center of commerce, culture, and innovation; the Council on Foreign Relations, an influential foreign-policy think tank with some 4700 members; the Trilateral Commission, an organization of leaders in the private sector founded by him and committed to discussion of issues of global concern; and the Bilderberg Group, an annual conference of political leaders and experts from various fields to discuss major issues facing the world. All this, while becoming the family patriarch and looking after a fortune that came to him mostly through trusts set up by his father, and that is estimated at $2.8 billion, which makes him #193 in the current Forbes 400 List of the richest people in America.

On a visit to Abu Dhabi in 1980, shaking hands with Jawad

On a visit to Abu Dhabi in 1980, shaking hands with Jawad Hashim, President of the Arab Monetary Fund.

Hashmoder

If one goes online, where conspiracy theories run wild, one can easily find websites warning that so-called Globalists are working secretly to establish a one-world government that will suppress national sovereignty and individual liberties and rule the world. Who are these nefarious individuals? International bankers, the super rich, the elite, members of the Council on Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, the Bilderberg Group, and other mysterious, secretive, suspect organizations, including the Illuminati, an 18th-century secret society in Bavaria that opposed superstition, prejudice, and the influence of religion in public life, and that supposedly survives to this day. Among today’s suspect elite, obviously, David Rockefeller looms large, albeit at the age of 98. These power mongers, these “banksters” are everywhere, theorists assert; they manipulate everything, they will destroy the world as we know it.

And what does David Rockefeller say to these charges? In his autobiography Memoirs, published in 2002, he observes: “For more than a century ideological extremists at either end of the political spectrum have seized upon well-publicized incidents such as my encounter with [Fidel] Castro to attack the Rockefeller family for the inordinate influence they claim we wield over American political and economic institutions. Some even believe we are part of a secret cabal working against the best interests of the United States, characterizing me and my family as ‘internationalists’ and of conspiring with others around the world to build a more integrated global political and economic structure – one world, if you will. If that’s the charge, I stand guilty, and I am proud of it” (Memoirs, p. 405).

“Aha!” cry many conspiracy theorists, seeing this statement as a brazen confirmation of their charges. But Rockefeller has in no way confessed to participation in a conspiracy, only to advocating a “more integrated global political and economic structure.” He then goes on to see his critics as influenced by Populism, and observes that Populists believe in conspiracies and consider him the “conspirator in chief.” He insists that the Rockefellers’ international role during the past half century has produced tangible benefits like the defeat of Soviet Communism, and improvements in societies around the world as a result of global trade, improved communications, and greater interaction of people from different countries.

So far, I think the defense of this “proud internationalist” sounds valid. David Rockefeller one of the Illuminati? Why not throw in the Hitlerjungen and the Ku Klux Klan as well? Except that, so far as I know, those groups lacked international connections and therefore might be allies of the conspiracy crowd. Rockefeller was certainly a lord of think tanks, but that doesn’t make him and them a clutch of conspirators. The conspiracy gang whom I have encountered online – and they are legion – strike me as paranoid; frankly, they are just plain nuts.

So let’s escape from cloud cuckoo land and enter the realm of possibility. Not all Rockefeller’s critics allege a worldwide conspiracy; rather, they see a shadowy permanent government that really runs this country, with whom our elected Presidents have to come to terms. Gary Null seems to be one of this tribe, though I’d need to know more about his views to be certain. But there are other voices of the Progressive Left whom I have to take seriously. Noam Chomsky has argued that the Trilateral Commission’s report The Crisis of Democracy, proposing solutions for the “excess of democracy” characteristic of the 1960s, embodies “the ideology of the liberal wing of the state capitalist ruling elite.” He sees the Commission as advocating “more moderation in democracy,” a more passive and obedient citizenry less inclined to put undue restraints on government. He also asserts that the Commission had an undue influence on the administration of President Jimmy Carter.

President Carter hosting the Trilateral Commission, 1978.

President Carter hosting the Trilateral Commission, 1978.Rockefeller must have been there, probably in the first row.

Whether I fully agree with Chomsky I’m not sure, but I listen to him. The Trilateral Commission is a creation of David Rockefeller, so any criticism of it implies criticism of its founder. Chomsky’s assertions aren’t all over the place, sniffing out conspirators everywhere; he is focused in his attack and raises questions well worth pondering.

So where do I end up? David Rockefeller has had a vast network of connections and has no doubt wielded tons of influence, perhaps at times too much. He has shunned the public arena, prefers quiet private conferences, is never flamboyant, eschews attention-getting gestures, is really quite quiet, even colorless. (Eschew: I love this word, even if it sounds like a sneeze.) But that doesn’t make him a conspirator or a nefarious person. He’s only one of many of the elite exerting influence on our government and society. Confirming my impression of him as an individual are reminiscences of him by my partner Bob’s doctor, who long ago met Rockefeller and conversed with him on several occasions. He found him very knowledgeable, very personable, unassuming, and easy to relate to, which is remarkable, given his privileged childhood.

Yet if Rockefeller or his associates are promoting the free-trade agreement known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is being secretly negotiated now, then I have to agree that they are potentially eroding our national sovereignty. According to certain leaked documents, the TPP would exempt foreign corporations from our laws and regulations, and let them challenge those laws and regulations as being unfair practices in restraint of trade. Our hard-won regulations on clean air and clean water, for instance, could be imperiled, not to mention countless other measures, and this worries me a lot. And if Rockefeller isn’t personally involved in promotion of the TPP (he is, after all, 98), like-minded people of great influence certainly are. And the general public is barely aware, if at all, of what is going on. Whether it involves a conspiracy or not, the TPP merits scrutiny and should be fought tooth and nail, unless its proposed provisions are radically revised. So score one – and a big one – for David Rockefeller’s more responsible critics, among them Gary Null.

Leaders of the Trans-Pacific Partnership member states, 2010. Guess who's beaming, right smack

Leaders of the Trans-Pacific Partnership member states, 2010. Guess who's beaming, right smackin the middle? No, it's not David Rockefeller.

Gobierno de Chile

Even so, my impression of the Rockefeller clan is favorable. They have long since risen above their robber baron origins, which were tainted with labor strife, to become philanthropists and patrons of the arts on a grand scale. John D., Sr., gave millions to worthy causes and created the Rockefeller and other foundations; John D., Jr., created Rockefeller Center at his own expense, and with his wife helped launch the Museum of Modern Art; and David’s brother Nelson, as Governor, built the magnificent Empire State Plaza in Albany, and in his will left his interest in Kykuit, the Rockefeller estate, to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, so that it is now open to the public. (For Rockefeller Center, see post #87, From Ghosts to Grandeur: Fifth Avenue; for the Empire State Plaza, see post #18, Upstate vs. Downstate: The Great Dichotomy.) All in all, this city, state, and nation owe them a lot.

Coming soon: The Bowery: From B'hoys to Bums to Condos. In the works: Taylor Mead, a free spirit and bedraggled innocent whose bare posterior has been seen in many an underground film. Other possibilities: Quentin Crisp ("Be yourself no matter what they say") and the Living Theater ("God bless them and God help them").

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on September 29, 2013 05:18

September 22, 2013

88. The House of death, the Mystic Rose, and Avenoodles

The story of Fifth Avenue in the second half of the nineteenth century is fraught with social wars waged with engraved calling cards dropped in silver card receivers just inside the entrance of palatial free-standing mansions. It was a war waged above all by the ladies, while their spouses competed on Wall Street or at the race track or in fancy gambling dens, or in regattas where they raced their yachts. These wars were fought with fervor and conviction, and for those involved, if not for society at large, the stakes were high. The battlefield was an avenue well built up to the south, but stretching on northward as a rutted lane into a semirural wasteland that a visionary few – mostly real estate developers, one suspects -- had christened the city’s future Axis of Elegance. Confirming their vision in 1853 was the decision by Archbishop John Hughes to build a majestic Catholic cathedral on Fifth Avenue between 50th and 51st Street, a decision followed by excavations and a sprouting of walls but nothing more, owing to a lack of funds. Still, the promise of a cathedral, albeit Romanist, did seem to foretoken a thoroughfare of taste and distinction.

One citizen who shared this opinion was Charles Lohman, a free-thinking self-appointed physician who in 1857 must have driven north over the rutted course of the avenue through an area given over to stockyards, truck gardens, scattered institutions, a few dispersed houses and shanties, and finally a rocky wasteland of scrub pines and bushes fit only for grazing cattle and goats. Quite possibly he took his wife with him, so he could show her some land that he was tempted to buy. The pending construction of the cathedral, and the city’s plans to begin work on the magnificent new Central Park, seemed certain to enhance the value of the Avenue. What Lohman had in mind were ten lots at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street that the archbishop was said to want for his official residence. Since His Grace had seen fit to denounce Madame Restell, the abortionist, from the pulpit, and since Madame Restell was the nom de guerre of Lohman’s wife, the couple deemed it deliciously appropriate to snatch the property out from under the archiepiscopal nose. On May 1, 1857, Lohman did exactly that, outbidding the archbishop handily. Informed of this, respectable citizens offered Lohman a substantial sum for the property, but he refused to sell. Later that year a panic erupted on Wall Street, sending real estate prices plummeting, and halting construction along Lower Fifth Avenue. Had the Lohmans made a mistake? After a year of “pinching times” the stock market recovered, trade picked up again, and construction along the Avenue resumed. No, the Lohmans had not made a mistake.

The Lohman residence, a palatial brownstone.

The Lohman residence, a palatial brownstone.Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York. Respectable society was now venturing farther uptown, building brownstones along the Avenue in the 50s. Then, in 1862, ground was broken on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street, where the walls of a handsome new mansion began to rise: the Lohmans were building at last! Horrified by the thought of the town’s most notorious abortionist residing grandly in their midst, adjacent property owners offered Lohman a reputed $100,000 for the property, but he spurned it. The construction took two years but in the end produced a four-story brownstone with a monumental entrance, its recessed doors flanked by pilasters and topped by a protruding ornamental hood, with gardens and stables adjoining: a monument worthy of the Avenue and destined to catch every passing eye.

So Madame had installed herself just two blocks from the rising walls of the unfinished cathedral, and just across 52nd Street from, ironically (given her profession), the spacious grounds of the Catholic Orphan Asylum. “She’ll have no society!” opined the neighbors were certain that she would have no society, but sometime later the windows were ablaze with gaslight to receive a jam of carriages with arriving guests: wealthy merchants, brokers, railroad moguls, physicians, lawyers, and even a few magistrates and legislators, all lured there by the hostess’s charm and notoriety, and the thrill of witnessing her ill-gotten wealth; some of them – unthinkable! – even brought their wives. All four floors were on display: three ground-floor parlors in bronze and gold with frescoes by Italian artists; the second floor with the Lohmans’ sumptuous bedroom; the third floor with servants’ rooms showing Brussels carpets and mahogany; and the fourth with a billiard room, and ballroom whose windows gave a fine view of the Avenue and the Park. Guests danced, played cards, smoked expensive cigars provided by the hosts, feasted at a table laden with delicacies, and gaped at the luxurious furnishings.

No gold speculator or thriving war contractor could match Madame’s dazzling debut on the Avenue. But if she and her husband gave receptions regularly thereafter, and they were well attended, it was mostly by gentlemen who didn’t bring their wives. Ann Lohman had all the trappings of wealth – costly millinery, a palatial residence, and five carriages and seven horses – but she waited in vain for calling cards to be dropped in her card receiver, cards that would acknowledge her acceptance by Society, cards that never came. So despite a promising beginning, Madame had lost the war.

Chagrin at her defeat may at in part explain why, in May 1867, a large silver plate bearing the engraved word OFFICE appeared on a gate in the low iron railing at 1 East 52nd Street, informing sharp-eyed neighbors that the mistress of the mansion would henceforth carry on her profitable business in the basement. Soon, closed carriages began arriving and depositing heavily veiled women who descended to the basement and, sometime later, came back up, still heavily veiled, to depart discreetly; the neighbors watched, shocked. Complaints to the authorities proved useless; Madame had arrangements with them. Only she knew which husbands mounted the steep stoop to her receptions, and which of their wives descended to the basement, and her lips were sealed. But this was revenge of a kind. For moralists, the persistence of this shadowy business on the Avenue proclaimed the impotence of justice and the rewards of crime and vice; as for the house itself, they labeled it the House of Death.

Not even an abortionist’s presence on the Avenue could slow down the relentless push uptown of the wealthy. In 1869 Mrs. Mary Mason Jones, a dowager of impeccable pedigree and, incidentally, an aunt of Edith Wharton, shocked everyone by moving to the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, an area still afflicted with slaughterhouses and shantytowns, and charitable institutions that, however noble their purpose, were not deemed fit neighbors for the mansions of the affluent. And once again the pioneer proved right: others followed and the area was soon filled with brownstones topped with a mansard roof.

Mrs. Astor, as painted by

Mrs. Astor, as painted by Carolus-Duran. Inhabiting these residences, often as not, were fresh waves of parvenus who relied on their vast fortunes to worm their way into Society, and whom others labeled Avenoodles. Determined to be a bulwark against the inroads of these moneyed barbarians was Caroline Astor, the wife of William B. Astor, a wealthy grandson of old John Jacob, whose older brother John Jacob III ran the family business, leaving him to a life of idleness given over to race track attendance, pursuing women other than his wife, and yachting. Unburdened by a usually absent spouse, Caroline, a Schermerhorn who could lay claim to even more illustrious ancestry than the Astors, acquired a court chamberlain in Ward McCallister, a Society-obsessed Southerner who had long since come North, traveled abroad, studied the manners, genealogy, and heraldry of European aristocrats, and married an heiress.

Together, in 1872, this like-minded twosome created the Patriarchs, a group of social eminences including both Old and New Money, who inaugurated the Patriarchs’ Balls, exclusive affairs reserved only for those deemed socially acceptable. Well covered in the press, these affairs made it very clear who was in and who was out, thus imposing a rigorous order on what might otherwise have been a chaotic social flux. Supplementing the balls were private weekly dinner parties at Mrs. Astor’s Fifth Avenue and 34th Street mansion, where conversation was limited to food, wine, horse flesh, yachts, country estates, cotillions, and marriages. Lacking both beauty and charm, Caroline Astor through force of will and cunning quickly established herself as the reigning queen of New York Society – “Society,” be it noted, with a capital S. McCallister christened her “the Mystic Rose,” a reference to the celestial figure in Dante’s Paradise around whom all other figures revolve; she didn’t object.

The Vanderbilt mansion, flanked by brownstones. Suddenly, palatial brownstones like the Lohman

The Vanderbilt mansion, flanked by brownstones. Suddenly, palatial brownstones like the Lohman residence began to look drab and dated. French chateau style was definitely in.

Into this rarefied world, or at least butting up against its barriers, came the Vanderbilts. Not just one but a whole bunch of them who, between 1878 and 1882, built residences between 51st and 58thStreet, a neighborhood redeemed at last from scandal by Madame Restell’s arrest and suicide in 1878. Mrs. Astor was not inclined to let these upstarts into her charmed social circle, even though the Vanderbilts had more money, and the grandchildren, well educated and well traveled, had put a distance between themselves and the founder of their fortune, old Cornelius, a gritty character who never quite shook off the rich profanity and rough ways of a wharf rat. But Alva Vanderbilt, the wife of William K., was determined to make her way socially, and got her husband to commission a new Fifth Avenue residence at 52nd Street, a palatial edifice modeled on Francis I’s sixteenth-century chateau of Blois. The result was an imposing three-story chateau in gray limestone (emphatically notbrownstone) with a steep slate roof, like nothing the Avenue had ever seen before; it launched a vogue in French chateau-style residences that changed radically that thoroughfare’s look. In no time the east side of Fifth Avenue above 59th Street would be crowded with such residences facing the Park, earning the Upper Avenue the name Millionaires Row.

Alva Vanderbilt, costumed for her ball. Alva filled her new residence with Renaissance and medieval furniture, tapestries, and armor, and announced a costume ball for March 1883 that the city’s elite, seeing it as the most spectacular event of the season, decided they simply must attend. Dressmakers toiled day and night for weeks, and groups of young ladies of the appropriate status practiced complex quadrilles to be performed on the magical night. Among them was Caroline Astor’s daughter Carrie, a school acquaintance and friend of one of Mrs. Vanderbilt’s daughters. But no invitation for Carrie came.

Alva Vanderbilt, costumed for her ball. Alva filled her new residence with Renaissance and medieval furniture, tapestries, and armor, and announced a costume ball for March 1883 that the city’s elite, seeing it as the most spectacular event of the season, decided they simply must attend. Dressmakers toiled day and night for weeks, and groups of young ladies of the appropriate status practiced complex quadrilles to be performed on the magical night. Among them was Caroline Astor’s daughter Carrie, a school acquaintance and friend of one of Mrs. Vanderbilt’s daughters. But no invitation for Carrie came.Puzzled as others received invitations, and well aware that her daughter had her heart set on performing in the quadrille, Caroline Astor put out cautious feelers: why no invitation? Through third parties, the word came back: Mrs. Vanderbilt would love to invite dear Carrie, but how could she, when she didn’t know Mrs. Astor? So there it was: the Vanderbilts might be upstarts, but her daughter’s happiness was at stake. “It’s time for Vanderbilts!” declared Mrs. Astor. Going up the Avenue in her carriage, she sent a footman in Astor-blue livery to deliver an engraved calling card to a servant in Vanderbilt-maroon livery at 660 Fifth Avenue, who dropped it in his mistress’s card receiver. Mrs. Astor hadn’t even entered the Vanderbilt chateau, but the calling card sufficed; the invitation came. With this simple act, the Vanderbilts were “in.”

The ball itself was the grandest event to date in the city’s history. Outside, police held back a dense crowd of onlookers as guests, their costumes masked, stepped down from their carriages and entered the brilliantly lit mansion, while other carriages drove slowly past so their uncostumed occupants could peer though the windows. Inside, palms and ferns, and orchids of every hue, had transformed the mansion into a tropical forest. In the oak-paneled ballroom the young ladies performed their quadrilles to the satisfaction of the other guests, who were costumed splendidly as knights, brigands, monks, bullfighters, Music, Fire, Summer, Louis the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth, Bo Peep, and the Electric Light. What Mrs. Astor wore I haven’t been able to ascertain.

Mr. Roland Redmond, whose costume

Mr. Roland Redmond, whose costume I haven't been able to decipher.

Mrs. John C. Mallory, well garbed,

Mrs. John C. Mallory, well garbed,well veiled.

The affair was amply recorded in the newspapers, and guests were encouraged to visit a designated photographer, lest their magnificence be lost to posterity. Many did, and the photographs have been preserved, showing the elite of the day posing very seriously in white satin with gold embroidery, black velvet with puffed sleeves, gauze wings when appropriate, gold-trimmed velvet and gray tights, flowered chintz, and a hundred other materials, all taking themselves very seriously, sublimely unaware that viewers of a later age might find them just a mite pretentious, if not downright silly. Among the guests were ex-President Grant and his wife, who hopefully were not required to wear costumes.

Despite the advent of the Vanderbilts, Caroline Astor extended her sway for years. To show her distinction, she announced that she would simply be known as “Mrs. Astor,” and had her calling cards printed accordingly. In 1888 Ward McCallister explained to a Tribune reporter that there were only 400 people in New York society, a group small enough to fit comfortably into Mrs. Astor’s ballroom; outside that group were people who wouldn’t be at ease in a ballroom or would make others ill at ease. So appeared the term “the Four Hundred,” which occasioned much comment and criticism. And his Mystic Rose had thorns; for the socially ambitious, not to be invited to the annual Astor Ball was calamitous. But in 1887 the Social Register appeared, a list of two thousand socially prominent names with ample information about each: a challenge to Mrs. Astor’s Four Hundred.

Not all the Astor clan acquiesced in her assumption of the title “Mrs. Astor.” Her nephew Waldorf Astor particularly resented it, thinking his wife just as deserving of the title, and moved to England to insinuate himself into the British aristocracy. By way of revenge on his aunt, he tore down his residence adjoining hers and in 1893 opened on the site the luxurious thirteen-story Waldorf Hotel. Caroline Astor was, to put it mildly, chagrinned, remarking sourly, “There’s a glorified tavern next door.” Her son John Jacob Astor IV now finally persuaded her to join the exodus northward, and in 1893, having leapfrogged the Vanderbilts just as they had leapfrogged her, she settled into a magnificent French chateau-style residence at Fifth Avenue and 65th Street, really a double residence housing her on one side and her son and his family on the other. In 1897 the son then built the seventeen-story Astoria Hotel next to the Waldorf Hotel, and later the two were joined to become the first Waldorf Astoria, whose successor is now on Park Avenue.

Mrs. Astor's new residence at 65th Street.

Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

In her palatial new residence the Mystic Rose, now a widow, continued to stage the Astor Ball, exclusion from which banished one to the depths of social degradation. The art gallery featured a massive marble fireplace at one end, and satin-paneled walls with a vast array of gilt-framed paintings under a ceiling of elaborate molding with huge crystal chandeliers. This was the scene of the annual event, and many other receptions as well, where the hostess greeted her guests under a painting of her by the French artist Carolus-Duran, her very real fleshly presence rivaling the likeness above her in formal dignity and chilling authority. Yet this social dominatrix now spent five months of the year in France, three in her palatial summer home at Newport, and only four in New York. Even in her absence, her authority was felt.

Mrs. Astor's new art gallery/ballroom. It could hold twelve hundred guests.

Mrs. Astor's new art gallery/ballroom. It could hold twelve hundred guests.But it was not to last. The Mystic Rose was fading, and McCallister departed this earth in 1895, his funeral well attended by the socially elite. By now many were questioning the relevance of the Four Hundred, or even the Social Register’s Two Thousand, including some who might reasonably aspire to inclusion. Such feelings were intensified by the publication of Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives in 1890, a pioneering work of photojournalism that documented the squalid living conditions of the city’s poor, which he blamed on the greed and neglect of the wealthy. As the new social awareness grew, Mrs. Astor’s balls came to an end, and her last years were ravaged by periodic dementia. But she didn’t give up easily: at times she was seen standing pathetically at the entrance to her empty ballroom, greeting throngs of imagined guests. She died in 1906, spared the news of her son’s death in the Titanic disaster of 1912, and her expatriate nephew Waldorf’s becoming the 1st Viscount Astor in Britain in 1917.

Me and junk mail: I hate it. It comes every day in huge batches, appeals from worthy causes who got my name and address from the other worthy causes to whom, in weak moments, I give modest but reliable donations. They try every conceivable ploy to get me to open the envelope: fake or real handwritten addresses; URGENT; RUSH RUSH RUSH; 2 FOR 1 GIFT OFFER; FREE GIFT INSIDE; PETITION ENCLOSED; no return address; CHECK ENCLOSED. If there is no return address, I discard the envelope unopened along with all the others. CHECK ENCLOSED / DO NOT MUTILATE OR TEAR ENVELOPE is a new gimmick perpetrated recently by the National Cancer Research Center. God knows I’m in favor of the war against cancer, being a cancer survivor, but how much can you do? Still, I opened it and there, sure enough, was a genuine check for the princely sum of $2.50. They invited me to accept the check, but suggested that I donate that amount or a larger one to the fight against cancer instead. Any decent, right-minded person would have at once made a substantial donation. So what did I do? I cashed the check. Gleefully, without a smidgen of embarrassment or shame. In the war against junk mail, I give no quarter. And if they phone me, you can imagine my response: “I don’t take solicitations by phone!” and then I immediately hang up. In the war against junk mail and junk phone calls – made even in the name of compassion, health, and a better world – I am ruthless. “Scrooge!” some may cry. “Skinflint!” “A grinch who’d steal Christmas!” Guilty, guilty, guilty as charged. But it’s me or them, my sanity and serenity versus their relentless attacks. And I intend to win.

Coming soon: Who really runs America? A look at conspiracy theories and the alleged existence of a permanent unelected government, with emphasis on the prime suspect, a multimillionaire and lord of think tanks who grew up with the Unicorn Tapestries in his bedroom, and who knew everyone in the world who counted.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on September 22, 2013 05:15

September 15, 2013

87. From Goats to Grandeur: Fifth Avenue

Early in the nineteenth century Fifth Avenue was a muddy rutted road leading north from Washington Square, where the city’s most distinguished bankers and merchants had just built handsome Greek Revival houses fronting three sides of the square. Optimistically, the city opened the avenue to 13th Street in 1824, then to 21st Street by 1830, and to distant 42nd Street by 1837. But the “avenue” was at first inhabited by only by those few who, having little need of company, preferred a landscape with rock outcroppings grazed by goats, and clusters here and there of squatters’ ramshackle shanties.

This changed in 1834, when Henry J. Brevoort, Jr., was so adventurous as to build a Greek Revival mansion on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Ninth Street. Indeed, from about 1830 on the city’s prosperous merchants grew increasingly discontented with their Federal style row houses on Lower Broadway, and were motivated to move north partly by the influx of commerce and the lower orders, and partly by a desire for the greater space and splendor of a freestanding house. With Washington Square at its base to shield it from commercial inroads, the new Fifth Avenue drew these migrants like a magnet, and in time the wide thoroughfare, now tree-lined and paved with cobblestones, was built up well to the north with long rows of handsome Greek Revival houses, their stoops rising grandly from the sidewalk, and here and there a Gothic mansion with pointed entrances and windows, and crenellated towers more suggestive of a castle than an urban residence. By the 1840s the avenue was lined with elegant residences all the way to Union Square and beyond, the square itself now nicely landscaped with a high-spuming fountain.

Then, in 1858, the six-story white marble Fifth Avenue Hotel opened on Fifth Avenue between 23rdand 24th Streets, offering accommodations for 800 guests and such unheard-of luxuries as sumptuously decorated public rooms, a fireplace in every bedroom, many private bathrooms, and that startling new invention, the vertical railroad, later known as an elevator. “Too far uptown!” proclaimed skeptics, but once again they were proven wrong; the hotel prospered from the start, inaugurating an era when Madison Square, at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, became the center of the city’s fashionable world.

Already, by the 1850s, a new style had come into fashion along Fifth Avenue and its parallel, Madison, and the cross streets between them: Italianate brownstone, which would characterize these and other thoroughfares for many years. Brownstone, obtained from quarries in New Jersey and Connecticut, was now viewed as more dignified than wood or brick, though in fact it was used simply to cover over brick façades and give them a dark “romantic” look. This soft stone also allowed for richly carved façades and lavish ornamentation, in contrast with the elegant restraint of the Greek Revival style, now seen as plain and dowdy. So from now on, for exteriors and interiors alike, classical simplicity was out; Victorian clutter was in.

Brooklyn brownstones today. The rage for brownstones spread

Brooklyn brownstones today. The rage for brownstones spread all over the city. The high stoops are typical.

Who were the inhabitants of these brownstones? First of all, Knickerbockers, old Dutch families that could trace their lineage back to the days of New Amsterdam, but also old English families that came to the city in colonial times. They lived tastefully and quietly in homes where the somber gilt-framed portraits of their forebears, governors and mayors and their wives, stared down austerely from the walls. Some had made fortunes in whale oil and tobacco and sugar, but by now often had transitioned into landholding, which seemed a bit more genteel. It was a world where everyone knew everyone, who their forebears were, and how they made their money. They socialized and married among themselves and were leery of the “new” people. It was a tight little world, conformist, predictable, and dull, but its residents found the dullness reassuring, a bit of stability in a world of endless change.

A mansard roof For change was all about them, gnawing at the edges of their world. In 1858 William B. Astor, Jr., and his brother John Jacob Astor III, built adjoining townhouses on the northeast corner of 33rd Street and Fifth Avenue, John Jacob’s house featuring a mansard roof, a style fresh from imperial Paris that at once became all the rage. And who were these Astors? Grandsons of John Jacob Astor, the German immigrant who came to America and made a fortune in the fur trade before branching out into other profitable fields of endeavor, a man remembered for sharp dealings and the ruthless accumulation of wealth, a philanthropist in his later years, but one who had no time for appeals from the needy or the outstretched palm of a beggar in the street. As was usually the way in America, the grandchildren and great grandchildren were glad enough to put space between themselves and the founder of the family fortune, who was often more skilled in the ruthless amassing of money than in the social graces. Whatever the Knickerbockers might think of them, the Astors were now on the scene as exemplars of Old New Money, as opposed to upstarts like the Vanderbilts, foremost in the mounting tide of New New Money.