Clifford Browder's Blog, page 49

November 24, 2013

101. Our Mayors: The Best and the Worst

A. Oakey Hall

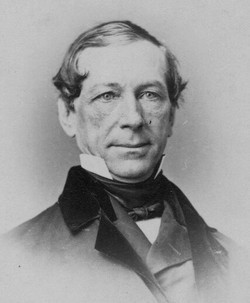

Probably the most versatile of New York mayors, and certainly the most elegant, was the 79th (1869-72), Abraham Oakey Hall, known to his contemporaries as the Elegant Oakey. Lawyer, journalist, politician, playwright, poet, and lecturer, he was a slim but active man, slight of build, with wavy black hair and a black beard and mustache, who sported a pince-nez with a black ribbon that dropped through an ample necktie into the depths of a snow-white shirt.

Probably the most versatile of New York mayors, and certainly the most elegant, was the 79th (1869-72), Abraham Oakey Hall, known to his contemporaries as the Elegant Oakey. Lawyer, journalist, politician, playwright, poet, and lecturer, he was a slim but active man, slight of build, with wavy black hair and a black beard and mustache, who sported a pince-nez with a black ribbon that dropped through an ample necktie into the depths of a snow-white shirt. He came by his nickname rightly, for he dressed in the height of fashion and rarely wore the same outfit twice. His wardrobe included velvet-collared coats made to order by the city’s most fashionable tailors; shirts of the finest linen; fancy vests, some of them embroidered by his wife; jewelry of his own design from Tiffany’s; and elaborate cuff links also designed by himself.

For special occasions he took care to dress appropriately. At the annual Americus Club ball in 1869 he wore a bottle-green coat with half sovereigns of pure gold for buttons and a green velvet collar and lapels; an ample satin necktie; a shirtfront embroidered with shamrocks in green floss silk; outsized emeralds glinting in his buttonholes; and eyeglasses with a green silk cord. Certainly he must have outshone all other attendees, but why, one might ask, all the green? Because the club was Boss Tweed’s creature, and its members his Tammany cronies, many of whom were Irish immigrants; himself a WASP of the old order, the Elegant Oakey was well aware of this. Needless to say, green dominated his St. Patrick’s Day apparel as well.

A Whig turned Republican, he is said to have left that party in turn to become a Democrat, because he found Abraham Lincoln, the party’s 1860 presidential candidate, too backwoodsy, too uncouth. Yet he himself, though WASP to the core, was no child of privilege; his widowed mother had had to run a boardinghouse to make ends meet, and her brilliant son had worked hard to get ahead. Now, with Boss Tweed’s help, he became district attorney and prosecuted hundreds of cases successfully. Yet he felt no deep need for change, was not inclined to make waves, and so was seen by Tweed as just the mayor he needed. He was elected in 1869.

The new mayor lived well, dined well. A lavish spender, he was seen daily at Delmonico’s, and received dozens of dinner invitations from the gentry, in whose brownstones he was always welcome as a genial guest who enlivened the conversation with his quips and puns. He was, in fact, useful to Tweed as a bridge to the brownstones, in whose tasteful parlors Tweed and his Tammany cohorts were never allowed to set foot.

If less than diligent in overseeing the city’s accounts, Mayor Hall was a whiz at the mayor’s ornamental duties, entertaining distinguished foreign visitors, presenting toasts at public banquets, and performing marriages. And no mayor had ever laid cornerstones of public buildings as deftly as he, brandishing one of a set of silver trowels he had accumulated for precisely this purpose.

Many of the Tammany braves looked askance at the mayor, baffled or annoyed by his high society connections, his glittering wardrobe, his writing of – of all things! – plays. But Tweed, aware of the Elegant One’s perceived lightness of being, reassured them: “Oakey’s all right. All he needs is ballast.” By “all right” perhaps he meant slack, compliant, signing vouchers without asking questions..

Suddenly, in July 1871, Mayor Hall’s snug tenure received a shock, when a disgruntled Tammany man leaked a series of accounts transcribed from the books of the city comptroller, showing huge payouts to contractors for work on the still unfinished county courthouse. (Yes, in those days too there were whistleblowers.) Published with fanfare in the New York Times, these accounts – thermometers $7,000, brooms $41,000, plastering close to three million, carpentry well over four – shocked and infuriated the public, provoking a mass movement of reformers to overthrow Tweed and his Ring, which presumably included Mayor Hall. Tammany was in deep trouble, and the mayor as well.

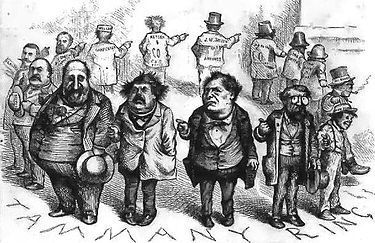

Spearheading the attack on the alleged Ring (“true as steal”) were the cartoons of Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly, which even the most illiterate of voters could grasp. Nast turned Tweed into a bloated plundering monster, and Hall into a prancing little popinjay with drooping beribboned pince-nez, a figure as ridiculously lightweight as his Tweed was ponderous and menacing. But lightweight or not, A. Okay Haul, as Nast labeled the mayor, was lumped with Tweed, his cronies, and the contractors in a vast conspiracy to defraud the public. His defenders insisted that the mayor was honest, that his only fault was not inspecting the accounts more closely, but the reformers were not convinced.

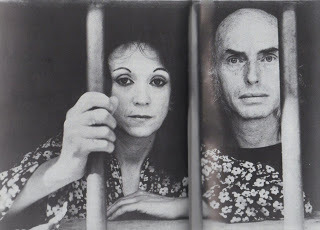

A Nast cartoon: Who stole the people's money? 'Twas him.

A Nast cartoon: Who stole the people's money? 'Twas him.Hall is on the right, with the outsized pince-nez.

As the reform movement gathered momentum, many suspects developed a sudden yearning for the cultural delights of Paris (which had just undergone a lengthy siege by the Germans and, following that, a bloody insurrection) and decamped forthwith, but the mayor, protesting his innocence, stood his ground. No less than three trials resulted, and the Elegant One, an experienced attorney, defended himself with skill, witty and charming one moment, caustic or tearful the next, but always the soul of innocence. If he had signed some 39,257 vouchers as mayor, he had had neither time nor inclination to read them, having “an ineradicable aversion to details.” The first trial ended with the death of a juror, the second with a hung jury, and the third with an acquittal. Following this, the now ex-mayor wrote a play, The Crucible, about a man accused of stealing that was produced with himself in the lead. As always, he was amazingly versatile.

The play, alas, was a flop. After that he seems to have suffered a nervous breakdown and moved to London, where he resided for several years. He returned to public life as a journalist and lawyer, and in 1894 defended the anarchist Emma Goldman against charges of inciting to riot; though sentenced to a year in prison, she hailed him as a champion of free speech. He died in 1898.

Years after the Tweed scandals erupted, when the rage for reform had subsided, some of the reformers revised their opinion of Hall, whom they now believed to be innocent of knowingly defrauding the public. Today historians tend to agree. He was a skillful lawyer, a delightful punster, a dazzling dandy, and a deft wielder of silver trowels at the laying of cornerstones, but not a criminal. Lightweight though he was, had it not been for his fatal connection with Tweed, he might have hoped to be governor.

Fernando Wood and Jimmy Walker

Striking a Napoleonic pose.

Striking a Napoleonic pose. Or just scratching. Previous posts have discussed this duo, who compete with other candidates for the distinction of most corrupt mayor. (See vignettes #9 and #14, and posts #85 and #100.) We have seen how “Fernandy,” the 73rd and 75th mayor of New York (he was elected to two nonconsecutive terms, 1855-58 and 1860-62), a veteran tippler, maneuvered skillfully in the 1850s to avoid implementing the prohibitory Maine Law in all but name. During his second term, faced with the South’s secession and the city merchants’ opposition to war, he made the novel proposal that New York likewise secede from the Union and, as an independent state, continue its profitable trade with the South. His proposal went nowhere and, despite its misgivings, the city contributed mightily to the government’s war effort. After this second term he probably reached a secret understanding with Boss Tweed, a rising power, whereby he abandoned municipal politics to Tammany and with the Boss’s blessing ran instead for the House of Representatives, where he served several terms until his death in 1881. A survivor, then, in politics, and as slick a customer as ever graced the mayor's office, but was he corrupt? Though he was never convicted of anything, the consensus then and now says yes. As the first professional politician to hold that office, and above all as a Tammany mayor, everything points to his guilt.

Slim, dapper, and charming, Jimmy Walker, our 97th mayor (1926-32), was adept at surfaces, thus following in the nimble footsteps of the Elegant Oakey. Notice that smile in the photograph; admittedly with the benefit of hindsight, I find in it a hint of the supercilious and sly. Would you trust your money or the city’s to such a smile? Certainly not. But New Yorkers of the Jazz Age didn’t care; they were having too much fun. So Gentleman Jimmy kept on doing what he did best: leading parades down Fifth Avenue sporting a silk topper and a smile, and a cutaway coat, striped trousers, and a walking stick; reveling at night in speakeasies with his chorus girl girlfriend, and rarely showing up at City Hall before noon; tossing off wisecracks and smiling. For New Yorkers, having a fun-loving mayor was fun … for a while. But when rumors of corruption led to Judge Samuel Seabury’s extensive investigation of his administration, under pressure Gentleman Jimmy resigned and promptly decamped for Europe and an extended vacation, returning only when the investigation had uncovered no hard evidence against him. Greeting him at the dock were a multitude of well-wishers, a serenade of ferry whistles and horns, and an eager throng of reporters. Beau James was, after all, charming. Had he taken bribes (“beneficences,” he called them)? Almost certainly. But he never went to prison.

Slim, dapper, and charming, Jimmy Walker, our 97th mayor (1926-32), was adept at surfaces, thus following in the nimble footsteps of the Elegant Oakey. Notice that smile in the photograph; admittedly with the benefit of hindsight, I find in it a hint of the supercilious and sly. Would you trust your money or the city’s to such a smile? Certainly not. But New Yorkers of the Jazz Age didn’t care; they were having too much fun. So Gentleman Jimmy kept on doing what he did best: leading parades down Fifth Avenue sporting a silk topper and a smile, and a cutaway coat, striped trousers, and a walking stick; reveling at night in speakeasies with his chorus girl girlfriend, and rarely showing up at City Hall before noon; tossing off wisecracks and smiling. For New Yorkers, having a fun-loving mayor was fun … for a while. But when rumors of corruption led to Judge Samuel Seabury’s extensive investigation of his administration, under pressure Gentleman Jimmy resigned and promptly decamped for Europe and an extended vacation, returning only when the investigation had uncovered no hard evidence against him. Greeting him at the dock were a multitude of well-wishers, a serenade of ferry whistles and horns, and an eager throng of reporters. Beau James was, after all, charming. Had he taken bribes (“beneficences,” he called them)? Almost certainly. But he never went to prison.John Lindsay

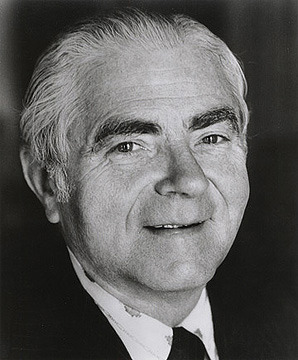

John Lindsay, our 103rd mayor (1966-73), was probably the handsomest mayor, but it did him little good in office; he came in riding high, experienced one crisis after another, and left office wounded and depressed. It was his misfortune to preside over a city in deep crisis that allowed for no quick fix.

Carrying his budget. And a heavy load it was. A liberal Republican, for seven years he had represented Manhattan’s 17th District, the East Side’s so-called Silk Stocking District, in Congress. In 1965 he ran for mayor, an office no Republican had held since Fiorello La Guardia’s time. Winning support from key Republicans, he presented himself as a candidate that Democrats and Liberals could vote for (I know; I voted for him); campaigning ably, he won in a tight race. The new mayor aroused great hopes and had an aura of glamor about him, but on January 1, 1966, his first day of office, the Transport Workers Union went on strike, shutting down all the subway and bus lines that the city depended on.

Carrying his budget. And a heavy load it was. A liberal Republican, for seven years he had represented Manhattan’s 17th District, the East Side’s so-called Silk Stocking District, in Congress. In 1965 he ran for mayor, an office no Republican had held since Fiorello La Guardia’s time. Winning support from key Republicans, he presented himself as a candidate that Democrats and Liberals could vote for (I know; I voted for him); campaigning ably, he won in a tight race. The new mayor aroused great hopes and had an aura of glamor about him, but on January 1, 1966, his first day of office, the Transport Workers Union went on strike, shutting down all the subway and bus lines that the city depended on.Lindsay’s three-term predecessor, Robert Wagner, had known that Mike Quill, head of the TWU, liked to threaten a strike and bluster, but would settle at the last minute on terms that both he and the city could call a victory. But Lindsay knew little of such tactics and made the mistake of lecturing Quill on civic responsibility instead. Quill, a gutsy Irish immigrant, resented this. In fact, he resented everything about the incoming mayor: his boyish prep school looks (he was only 43), his naïve idealism, his aura of Mr. Clean. “Coward! Pipsqueak! Ass!” he bellowed in a brogue at the mayor, whom he referred to contemptuously as “Lindsley.” He was determined to teach this well-scrubbed kid, this WASP in shining armor, a lesson, even at the cost of time in jail, his strike being technically illegal.

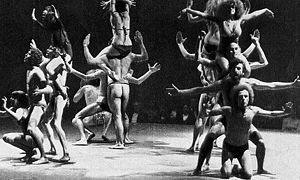

Quill indeed went to jail, and the strike lasted an unprecedented thirteen days and cost the city $1.5 billion in lost productivity and wages. “I still think it’s a fun city,” said Lindsay, who walked four miles from his hotel to city hall daily, but the “fun city” remark would be repeatedly thrown in his face by critics. Meanwhile officials advised citizens to rediscover “the lower appendages,” and I did, walking up from the Village to Midtown to get a ticket to the previously sold-out play Marat/Sade, now available because of cancellations; then, to see it, I walked up again. (Full title: The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade. See why it’s referred to as Marat/Sade?) As for commuting to my teaching job in distant Queens, with the subway system out I enjoyed a surprise vacation, but not everyone was happy. A settlement was finally reached, giving the TWU a huge pay raise that committed the city to burdensome labor costs for years. It was a great victory for Quill, but three days after the settlement he died of a sudden heart attack.

More crises followed. An attempt to decentralize the school system, where black students had mostly white (and usually Jewish) teachers and administrators, led to a strike by the United Federation of Teachers that closed 85% of the schools for 55 days, putting a million children out of classrooms and disrupting their families. It was a nasty affair, with charges of racism and anti-Semitism flying thick and fast. Tensions between blacks and Jews persisted for years, thus splitting the liberal base that the mayor depended on. Meanwhile the sanitation workers went on strike, leaving the sidewalks heaped with stinking garbage that winds hurled hither and yon, and the police staged a slowdown, and firefighters threatened job actions. One bright spot: when the assassination of Martin Luther King provoked riots in black ghettos across the nation, Lindsay walked the streets of Harlem to reassure residents that he mourned King and was working against poverty; no riot occurred. But the chaotic last six months of 1968 were, in Lindsay’s own words, “the worst of my public life.”

Not that 1969 was much better. In February a blizzard buried the city in 15 inches of snow, leaving side streets in Queens unplowed for days. When the mayor came to inspect, he was greeted by homeowners with boos and jeers and oaths. “You should be ashamed of yourself!” screamed one woman. “Get away, you bum,” said another. Never had an honest mayor with the best intentions been received with such antipathy. The whole affair reinforced a growing impression that the mayor, biased in favor of minorities, was indifferent to the problems of the white middle class in the outer boroughs.

The accusation that Lindsay favored minorities over whites smacked of racism, yet it was not without substance. I recall hearing reports of a riot by angry welfare mothers in a welfare office. Sensing that they could get away with it, they began trashing the office. The police, though present, had strict orders not to interfere, so the office was demolished, its renovation another cost for taxpayers to bear.

With the mayor’s popularity plummeting, in the 1969 election he lost the Republican nomination to a conservative, so he ran on a Liberal/Fusion ticket and won, his support coming from minorities and certain segments of the white middle class. But the second term was no better than the first, being plagued by growing racial tensions, a rise in crime, revelations of police corruption, soaring labor and welfare costs, and a deteriorating fiscal situation; was Armageddon fast approaching? When Lindsay, becoming a Democrat, embarked on a quixotic campaign to grab the party’s presidential nomination in 1971, he only made matters worse, since Democrats viewed him as an intruder, and New Yorkers resented this distraction from the problems at home. When the next mayoral election loomed in 1973, the embattled mayor, abandoned by both Republicans and Democrats, gave up any thought of running as a Liberal and left office in a state of exhaustion. It is said that he broke down in tears, frustrated because he had not accomplished more as mayor.

What does an ex-mayor do with the rest of his life? Unlike the governorship of New York, which has hatched many a presidential candidate and sometimes even a President, the office of New York City mayor is not a springboard to higher office, only a political dead end. John Lindsay went back to the law and became a radio commentator and journalist. In 1980 he lost a primary bid to become the Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate; tipping the scales against him in the Florida primary was a flood of letters from Jewish citizens in New York to their Florida relatives and friends, inveighing against the former mayor. Becoming chairman of the Lincoln Center Theater, he helped in its rejuvenation, but with failing health gradually faded from the scene. Because he had no health insurance, medical expenses depleted his savings. Learning of this, his friend Mayor Giuliani obtained a city position for him that included health insurance. In 2000, at age 79, John Lindsay succumbed to pneumonia and Parkinson’s.

Subsequent mayors would blame Lindsay for the city’s ongoing woes, which assumed gigantic proportions while he was in office. He made grievous mistakes, especially in resorting to fiscal legerdemain, but those woes had been long in coming. Yet if ever there was a failed mayoralty – indeed a tragic one – it was that of John Lindsay. Just recounting it briefly depresses me.

Abraham Beame

Dullsville incarnate, but sometimes that's just

Dullsville incarnate, but sometimes that's justwhat's needed. Abe Beame, a clubhouse Democrat who succeeded John Lindsay as our 104thmayor (1974-77), may well have been the blandest, dullest, most self-effacing mayor of New York, lacking La Guardia’s fire, Lindsay’s initial glamor, and the showmanship of Ed Koch. I confess that I recall absolutely nothing about him personally, only the events of his time. In TV debates he faded almost to the point of vanishing. His jokes were lame, and his speeches so dull that those unlucky enough to hear them could hardly recall a word minutes later. Nor did it help that he was short in stature (only 5 feet 2), not one to dominate a gathering. Because of his passion for detail, some thought of him as a glorified bookkeeper, which, along with his dullness, actually appealed to many voters eager for a change. He was quietly energetic, patient, dignified, and self-confident: qualities he would have vast and desperate need of during his one tumultuous term in office.

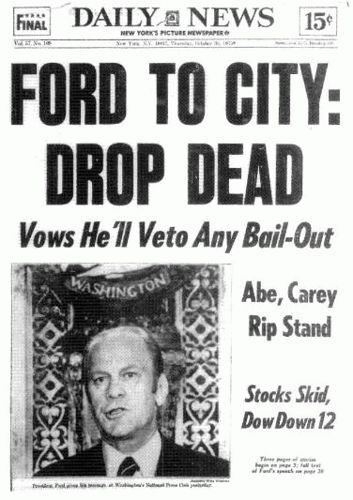

Why anyone would have wanted to be mayor of New York in the 1970s, inheriting all the woes that had so bedeviled John Lindsay, is a mystery that only ambitious politicians can explain. But mayor he was, and saddled at once with the worst fiscal crisis in the city’s history as banks denied credit and – to the astonishment and bafflement of most citizens – bankruptcy loomed. It seemed impossible, inconceivable, but there it was: bankruptcy! Schools were half-built, public works spending was halted, streets were dangerous and dirty, libraries had shorter hours, firehouses and police stations had to be closed; the city, in short, was in a state of collapse. Desperate, Mayor Beame coped as best he could, cutting the city work force drastically, freezing wages, limiting services, and raising taxes – hardly a formula to endear him to a mystified public not used to such painful retrenchment. With the city still short of funds, Beame begged state and federal officials for help. President Gerald Ford was at first indifferent, provoking the Daily News’s memorable headline: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. In time both Washington and Albany came through, while taking great chunks out of the mayor’s autonomy.

I remember those dark days, when the specter of bankruptcy loomed large. Some said that bankruptcy would be fatal to the city and the nation; others scoffed, insisting that this was New York City’s problem only, and to think otherwise was another example of the city’s megalomania. My own ill-informed reaction was: let’s let it happen, and see. But wiser noodles prevailed. An employee at my bank who oozed financial acumen later told me how he had urged his clients to buy city bonds, which were so reduced in price that they paid a fantastic rate of interest. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” he insisted. “There is no way that New York will be allowed to fall into bankruptcy. No way, I tell you, no way!” Those who took his advice fared well. I was not among them, having no funds available to invest. And when I went on a visit to Washington, an acquaintance there harangued me gently, beginning, “You New Yorkers …!” This I quietly resented, recalling how the Brits so often initiate their assaults on us with “You Americans …!” – a formula I have vowed at all costs to eschew. (That word again, like a sneeze; I love it.)

In the 1977 Democratic primary Abe Beame, accused of misleading investors by at first concealing the city’s perilous fiscal condition, lost to an ebullient rival named Ed Koch, as colorful and assertive a character as Beame was bland and self-effacing, and who went on to become the next mayor. Beame then retired from politics but continued to insist that he had saved the city, while the governor, the city’s labor leaders, and Washington all generously claimed that glory for themselves. The fact remains that Abe Beame, having inherited a $1.5 billion deficit, left office with a $200 million surplus.

Edward Koch

Recently I asked two friends if they had a favorite mayor. Without hesitation they both said, “Koch!” Asked why, they said, “He was outspoken, he told it like it was.” I had heard him once, as a councilman, talking to people on the street, but until he succeeded Beame in 1978 as our 105th mayor (1978-89), I didn’t get the full blast of his personality.

And what a blast it was! Loud, feisty, combative, this Bronx-born son of Jewish immigrants from Poland was the quintessential New Yorker. He could rub you the right way or the wrong, depending on his mood and your own, but you would not easily forget him, nor did he want you to. Balding with a broad, hearty grin that was often described as devilish, he was more rumpled than dapper and stood in vivid contrast to his immediate predecessors, the elegant Ivy Leaguer John Lindsay, and the self-effacing statistician Abe Beame. “I’m the sort of person who will never get ulcers,” he told reporters on Inauguration Day. “Why? Because I say exactly what I think. I’m the sort of person who might give other people ulcers.” And he probably did.

And what a blast it was! Loud, feisty, combative, this Bronx-born son of Jewish immigrants from Poland was the quintessential New Yorker. He could rub you the right way or the wrong, depending on his mood and your own, but you would not easily forget him, nor did he want you to. Balding with a broad, hearty grin that was often described as devilish, he was more rumpled than dapper and stood in vivid contrast to his immediate predecessors, the elegant Ivy Leaguer John Lindsay, and the self-effacing statistician Abe Beame. “I’m the sort of person who will never get ulcers,” he told reporters on Inauguration Day. “Why? Because I say exactly what I think. I’m the sort of person who might give other people ulcers.” And he probably did.A city councilman, and then a congressman representing the 17th Congressional District (the Silk Stocking District, the very one that Lindsay had represented), he had opposed the Vietnam War and supported civil rights in the South, before shifting to the right and proclaiming himself a “liberal with sanity,” though some might have preferred “pragmatic conservative.” In politics, timing is all; he had the good fortune – or the shrewdness – to become mayor when the worst about the city was known, and policies were in place to lead it out of the fiscal wilderness into the promised land of solvency and prosperity, for which he could of course take credit. Ed Koch was never shy about taking credit, when credit – the good kind -- was to be had.

In his first term he held down spending, kept the municipal unions in check, restored the city’s credit, and began the long-delayed work on bridges and streets. During a 1980 subway strike he stood on the Brooklyn Bridge and encouraged commuters hoofing it to work. “We’re not going to let these bastards bring us to our knees!” he shouted, and was applauded. Re-elected in 1981 on both the Democratic and Republican tickets, he oversaw further improvement in the city’s finances, rehired workers, restored services, and planned major housing programs. For a city long beleaguered by debt and mocked and censured by its critics, things were decidedly looking up. Thanks to these improvements and a resurging local economy, New Yorkers could at last take pride again in their city. And presiding over the recovery was a mayor who rode the subways like everyone else and stood on street corners asking passersby, “How’m I doin’?”

In New York City politics, third terms for a mayor – very rare – have proved to be a wasteland and a mire, and so it was for Ed Koch. Corruption in several city agencies was exposed, landing various high-placed Koch supporters in prison; while the mayor himself was not involved, he was accused of complacency and cronyism. He was also assailed for an inadequate response to the AIDS epidemic that was ravaging the gay community, many of whom alleged that the mayor, a perennial bachelor who seemed to have no private life, was secretly gay and reluctant to deal with the crisis for fear of being exposed – an allegation that he ignored and later stoutly denied. At the same time, various remarks of his helped further estrange him from a black community beset with homelessness and crack cocaine, just as racial tensions rose. In the 1989 Democratic primary the mayor, hoping for an unprecedented fourth term, lost to David Dinkins, the only black candidate, who then won the general election. As Koch himself came to realize, New Yorkers were tired of their bigger-then-life mayor and his in-your-face chutzpah; the mild-mannered Dinkins looked good to them. The retiring mayor, too, was tired and even – was it conceivable? – less self-confident, less sure that Ed Koch had all the answers.

Not one to fade into the shadows, in his post-mayoral years he resumed his law practice; made appearances on TV and radio, sometimes playing himself; wrote columns for newspapers; endorsed commercial products; gave lectures throughout the country for hefty fees (“Koch on the City,” “Koch and the State,” “Koch on Everything”); issued political statements and endorsements that were often controversial; and wrote numerous books and taught. As late as 2010, at 86, he campaigned against a dysfunctional legislature in Albany, shouting, “Throw the bums out!” His first memoir, Mayor (1984), became a best-seller and inspired an Off Broadway musical by the same name. Entering a hospital shortly before his death, he told a reporter one of the things he was most proud of: “I gave a spirit back to New York.” In 2013 he died of heart failure at age 88.

He was famous for his quips, calling his Tammany enemies “moral lepers,” black and Hispanic leaders “poverty pimps,” neighborhood protesters “crazies,” Donald Trump “piggy,” and the outspoken Bella Abzug “wacko.” (For more on Bella, see post #81.) Just as famous were his one-liners: “If you agree with me on nine out of twelve issues, vote for me; if you agree with me on twelve out of twelve issues, see a psychiatrist.”

If Ed Koch lacked vision and intellect, he achieved the near impossible by remaining popular through his first two terms while reducing city services and alienating certain groups. He did it thanks to shrewd political instincts, blatant showmanship, and the ability to say bluntly what many citizens secretly thought. Brains and vision are fine, but in politics it’s instinct that counts.

Conclusion

What can one conclude from glancing at these six mayors? Several things, I think:

If you've enjoyed two successful terms as mayor, don't run again; quit while you're ahead. People will get tired of you.Watch out for the slim, elegant ones, especially if they smile (Fernando Wood, Jimmy Walker); they aren't to be trusted.There's a law of opposites. Tired of the incumbent, voters go for his polar opposite. Dinkins was the opposite of Koch, who was the opposite of Beame, who was the opposite of Lindsay.

Toronto’s mayor: I thought New York’s galaxy of mayors couldn’t be outshone, but for sheer lurid glitter it’s hard to match Toronto’s current mayor, who has confessed to the use of crack cocaine and drunkenness, and is furthermore accused of making sexual advances to women. Citizens are clamoring for his resignation, but the mayor, after mouthing a few apologies, absolutely refuses to comply. And this in our tranquil neighbor to the north, whom I have always thought of as sober and sane.

Bank note: Followers of this blog know the love I bear my bank, J.P. Morgan Chase. It is now reported that this noble institution, out of the goodness of its heart, is settling civil claims with the Justice Department about the sale of mortgages to the tune of thirteen billion (yes, billion, not million) smackeroonies – an unprecedented sum. Hopefully the government will now leave that noble institution alone. To be sure, critics note that some seven billion of the settlement may qualify as a tax deduction, but let’s not quibble. They also complain that no one is going to jail, but such sadistic insistence is unwarranted. Go in peace, J.P. Morgan Chase. Let no one who has ever sinned cast the first stone.

Coming soon: The greatest mayor of them all, Fiorello. Other prospects include Andy Warhol (a friend of ours knew him), transportation in the city, lighting in the city, and the ladder of thieves ca. 1870 (from hog thieves and coat snatchers up to safe blowers).

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on November 24, 2013 04:41

November 17, 2013

100. New Yorkers and Booze, and Why Prohibition Won't Work

New Yorkers have always had a love affair with liquor. Not that this makes them any different from the rest of the nation. Consider, for instance, all the names Americans have given to the stuff: booze, the ardent, the stimulating, juice, giggle juice, tangle-legs, fire water, hooch, diddle, tiger’s milk, rotgut, coffin varnish, crazy water, and the oil of joy. And there are plenty more.

Steven Alexander And the terms we have used for “drunk”: drenched, pickled, plastered, soused, snookered, crocked, squiffy, oiled, lubricated, loaded, primed, sloshed, stinko, blotto, flushed, cockeyed, and (a good nautical phrase) three sheets in the wind. And that’s just a beginning. To which I’ll add my late friend Vernon’s charming way of indicating a lush: “a bit too fond of the grape.”

Steven Alexander And the terms we have used for “drunk”: drenched, pickled, plastered, soused, snookered, crocked, squiffy, oiled, lubricated, loaded, primed, sloshed, stinko, blotto, flushed, cockeyed, and (a good nautical phrase) three sheets in the wind. And that’s just a beginning. To which I’ll add my late friend Vernon’s charming way of indicating a lush: “a bit too fond of the grape.” All of which suggests a widespread social phenomenon, with attendant joys and woes. Earlier texts have already touched on the matter: Alcoholics I have known (vignette #12); Texas Guinan and her speakeasies (post #83); and Mayor Fernando Wood (“Fernandy”) and an earlier attempt at Prohibition (post #85). So now we’ll take the bull by the horns, or maybe the mug by the handle.

There were always saloons in the city, but they weren’t called that at first. A “saloon” in the mid-nineteenth century was a large public room or hall. Thus the ladies’ saloon on a steamboat was for respectable ladies and their male escorts; it was a refuge from noise and intemperance, and very, very dry. So what were the terms for what we today call a saloon? Grog shop, groggery, pothouse, gin mill, gin shop, dram shop, rum shop. But whatever it was called, it did a good business.

On every corner in the slums was a liquor grocery. Inside a typical one you could find piles of cabbage, potatoes, squash, eggplant, turnips, beans, and chestnuts; boxes containing anthracite, charcoal, nails, and plug tobacco, to be sold in any quantity from a penny’s worth to a dollar; upright casks of lamp oil, molasses, rum, whisky, brandy, as well as various cordials manufactured in the back room; hanging from the crossbeams overhead, hams, tongues, sausages, and strings of onions; and here and there on the floor, a butter cask or a meal bin. At one end of the room there was usually a plank stretched across some barrels, and on it some species of grog doled out at three cents a glass, and behind it on the wall, shelves with a jumble of candles, crackers, sugar, tea, pickles, mustard, and ginger. Finally, in one corner there might be another short counter with three-cent pies kept smoking hot, where patrons could get coffee also at three cents a cup and, for a penny, a hatful of cigars. Offering all that a tenement household might need, these places were well patronized by the locals, both men and women, and their mix of products show how drinking and grocery shopping and socializing were all jumbled together in a rich and complex tangle. Not fertile grounds for prohibitionists, one might think.

But prohibitionists there were, if not in Babylon on the Hudson, as some ministers were wont to call the Empire City, but in upstate rural counties and elsewhere, as for instance Maine, where the legislature in 1851 passed what would become known as the Maine Law, prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages except for medicinal and industrial purposes. Many states followed suit, and seemingly for good reason, since alcoholism was rampant. When two American males met, their greetings were often followed by, “Let’s liquor.” Mindful of this, many a patriarch enjoined his son departing for college, “Beware the flowing bowl!” Which was about as effective, I suspect, as similar admonishments today.

Regarding youthful follies of the time, I can only cite the charming memoir of the cartman I.S. Lyon, who tells of being hired to take two medical students and their baggage to a Philadelphia-bound boat. Entering their attic room in a four-story boarding house on Broadway, he found some twenty medical students gathered for a parting “blow-out.” The air was cloudy with tobacco smoke, and on a red-hot stove was a huge tin pot of badly concocted whiskey punch whose escaping vapors filled the room with noxious odors. The furniture was begrimed, the ragged carpet soiled with spilled liquor and tobacco juice, and the whole place littered with empty whiskey bottles, greasy French novels, defaced song books, and torn and detached sheets of music. Also strewn about were revolvers, daggers, sword canes, broken umbrellas, and pipes both long and short. As the two departing students prepared to leave, the whole group rose, glass in hand, and sang “We won’t go home until morning” as if the day of doom had arrived.

So would prohibition come to that den of inebriation, New York? Yes indeed, or so it seemed, for if the city was notoriously “wet,” the upstate rural counties were adamantly “dry.” (For the perennial conflict between upstate and downstate New York, see post #18.) In 1854 the legislature passed an Act for the Prevention of Pauperism, Crime, and Intemperance whereby, as of July Fourth next (a date the city hailed with whiskey- and rum-soaked revels), liquor would be banned throughout the state and public drunkenness forbidden. The law was vetoed by the governor, but his successor was a “dry,” and in 1855 the law was passed again by the legislature.

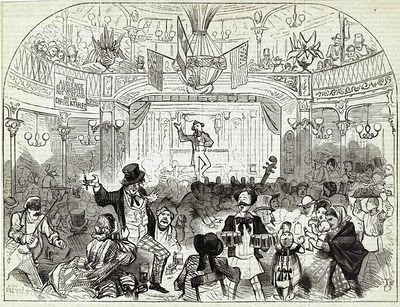

A New York beer garden on Sunday evening. Prohibition in booze-ridden Gotham? Was it even conceivable? The city was now full of newly arrived immigrants who were just as opposed to the law as many citizens. At the thought of prohibition the Irish in their grog shops, downing tumblers of cheap whiskey, muttered dark oaths. At the mere hint of it the Germans in their beer gardens, clinking steins, scowled under frothy noses, while behind the elegant façades of brownstones (certain brownstones) genteel profanity glanced off the rims of stemware over delicate wines. All eyes turned to the city’s newly elected mayor, Fernando Wood, himself once the proprietor of a groggery, and a known “wet” who over the years had frequented the city’s finest barrooms, his elegant form reflected in the huge gilt mirrors backing bars adorned with nippled Venuses and cupid-crowned clocks. So what was he to do?

A New York beer garden on Sunday evening. Prohibition in booze-ridden Gotham? Was it even conceivable? The city was now full of newly arrived immigrants who were just as opposed to the law as many citizens. At the thought of prohibition the Irish in their grog shops, downing tumblers of cheap whiskey, muttered dark oaths. At the mere hint of it the Germans in their beer gardens, clinking steins, scowled under frothy noses, while behind the elegant façades of brownstones (certain brownstones) genteel profanity glanced off the rims of stemware over delicate wines. All eyes turned to the city’s newly elected mayor, Fernando Wood, himself once the proprietor of a groggery, and a known “wet” who over the years had frequented the city’s finest barrooms, his elegant form reflected in the huge gilt mirrors backing bars adorned with nippled Venuses and cupid-crowned clocks. So what was he to do? Tall and dapper, “Fernandy” (as he was known to cronies) was as slick a character as had ever ruled the city (if anyone could rule it). Having consulted legal experts, he announced that he would of course enforce the law, however needless and impolitic, while giving full attention to exceptions, technicalities, and the rights of citizens, violating which, officers would be held to strict account. The law, in fact, had many flaws, and he had every intention of exploiting them to the full.

Tall and dapper, “Fernandy” (as he was known to cronies) was as slick a character as had ever ruled the city (if anyone could rule it). Having consulted legal experts, he announced that he would of course enforce the law, however needless and impolitic, while giving full attention to exceptions, technicalities, and the rights of citizens, violating which, officers would be held to strict account. The law, in fact, had many flaws, and he had every intention of exploiting them to the full.Needless to say, the city understood the mayor only too well, and its tippling did not notably decrease. Mercifully, within a year the law was voided in the courts, and the Sabbath quiet continued to be tainted by the din of unlicensed grog shops spilling out reeling drunks on the street.

Scripture in one hand, a hatchet in the other.

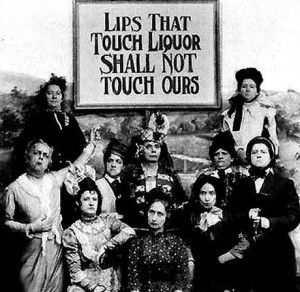

Scripture in one hand, a hatchet in the other.Many a bar was tomahawked. So ended the city’s first brush with legislated temperance. But the campaign for prohibition had only begun, aided and abetted – indeed, championed and promoted – by a host of female reformers determined to see the matter through. The movement was sidelined by the Civil War, but afterward it regained strength, especially following the founding of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1873. Successes followed: in 1881 Kansas became the first state to outlaw alcohol in its constitution, and subsequently Carrie Nation achieved notoriety there for entering saloons to smash liquor bottles by the dozen with a fiercely wielded hatchet. Described as sporting “the biceps of a stevedore, the face of a prison warden, and the persistence of a toothache,” Carrie was a formidable activist, but hardly typical of the crusading women, who preferred hymns, prayers, and arguments to hatchets. What explains their dedication? For most of them, painful personal experience with a drunkard father, brother, spouse, or son at whose hands they had suffered humiliation and abuse.

Prominent among the drys were Methodists, Baptists, Quakers, and other Protestant groups, as opposed to Roman Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans. Not that everyone involved was motivated by lofty ideals: tea merchants and soda manufacturers sided with the drys in hopes of increased sales following a ban on alcoholic drinks. The conflict between rural upstate citizens and downstate urban residents in New York State was replicated throughout the country, with rural populations viewing the cities as not only rum-soaked but also crime-ridden and corrupt. And when the WCTU expanded its campaign to include women’s suffrage, the leading group focused solely on Prohibition became the male-dominated Anti-Saloon League, founded in 1893 in Ohio but soon active throughout the nation and especially influential in the South and the rural North.

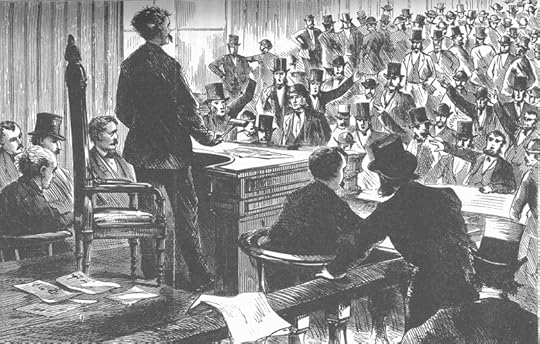

An all-male bastion.

An all-male bastion.New York City was not without some ardent prohibitionists, but the city generally remained passionately and determinedly wet. Women reformers were especially resented by working-class males, who saw the reformers’ activities as an assault on a whole way of life centered in what was now called the saloon. The saloon was their refuge and social center, a place to get free – for a while – of family obligations, a place to down a few with their pals after work, before trudging homeward with diminished funds to face the scolding tongues of their wives. (“Women,” went a saying, “you can’t live with ’em and you can’t live without ’em.”) And in Tammany-dominated New York the saloon was also the political base of the proprietor, often an alderman, who dispensed liquor and salty eats freely toward election time and so corralled the necessary votes for his own or his cronies’ reelection. All this was threatened by these misguided and depraved reformers, these well-scrubbed preachers and goody-goodies, who had no understanding of the city’s raw needs. To put it bluntly:

meddling females + preachers + hicks = Prohibition

whereas

no Prohibition = freedom = sanity = bliss

Singing hymns outside a saloon.

Singing hymns outside a saloon.

And there is little doubt that the reformers had their sights on New York City. Out-of-town ministers had long made a habit of visiting it on a whirlwind tour to see first-hand its sins, so they could go home and inform their congregations about this sink of depravity and cesspool of greed. It was Babylon on the Hudson, it was Sodom and Gomorrah, it was Satan’s Seat. So Prohibition was deemed especially appropriate for Gotham, where it was most needed; it would breed virtue and sobriety.

One year later, Prohibition went into effect.

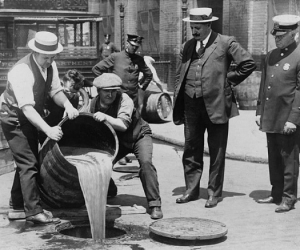

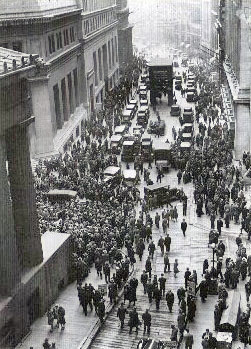

One year later, Prohibition went into effect. Dumping beer into the New York City sewers. By January 1919 enough states had ratified the Eighteenth Amendment to make nationwide prohibition a certainty, and on January 16, 1920 – a day that for New Yorkers would live in infamy -- the ban went into effect. Police confiscated quantities of barrels containing wine and beer, smashed them, and dumped their contents into gutters or the harbor, while stunned Gothamites watched in shock and horror. Huge vats of alcohol were discovered in outlying areas, and the Coast Guard began intercepting liquor-laden boats bringing thirsty Americans the hooch they longed for.

Dumping beer into the New York City sewers. By January 1919 enough states had ratified the Eighteenth Amendment to make nationwide prohibition a certainty, and on January 16, 1920 – a day that for New Yorkers would live in infamy -- the ban went into effect. Police confiscated quantities of barrels containing wine and beer, smashed them, and dumped their contents into gutters or the harbor, while stunned Gothamites watched in shock and horror. Huge vats of alcohol were discovered in outlying areas, and the Coast Guard began intercepting liquor-laden boats bringing thirsty Americans the hooch they longed for.The lower classes were at once deprived, but their betters had already stockpiled vast quantities of their preferred labels. Significantly, President Woodrow Wilson had promptly moved his personal supply to his Washington residence when his term of office ended, while immediately after inauguration Warren G. Harding, his successor, moved his own stash into the White House.

Such maneuvers were fine for the moneyed elite, but New York City had an answer of its own: the speakeasy, of which within a year or two there were between 20,000 and 100,000 in the city, and all of them thriving, since to tell New Yorkers they can’t do something at once kindles in them a passionate desire to do it. At first the speakeasies operated clandestinely and required patrons, viewed suspiciously through a peephole, to give a password to enter, but soon enough there was little need for pretense, since the police were amply rewarded for looking the other way.

The speakeasies ranged from the lowest dives offering cheap rotgut of dubious provenance requiring gastric fortitude, to well-appointed establishments catering to the wealthy and elite. And if the now-banished saloons had enjoyed a strictly male clientele, these new night spots went defiantly coed. Patrons included Charleston-dancing flappers and their callow escorts, cavorting businessmen from Cleveland and their intrepid spouses, assorted judges and aldermen, visiting dignitaries, silent film stars, and from 1926 on, His Honor the Mayor.

And where did all this liquor come from? Some was homemade, with all the perils that entailed: foul-tasting brews, explosions, after effects ranging from atrocious hangovers to departures for the beyond. But much of the booze came from elsewhere. In a fit of neighborliness the distilleries of Canada labored diligently to supply the needs of a deprived population to the south, across a long and porous border. And visible off the Rockaways was Rum Row, a fleet of ships at permanent anchor just outside the three-mile limit, where U.S. jurisdiction ended: floating warehouses for smugglers who, dodging the Coast Guard under cover of darkness, brought the precious stuff to land in speedboats.

A rum runner seized by the Coast Guard, with confiscated liquor stacked on the deck.

A rum runner seized by the Coast Guard, with confiscated liquor stacked on the deck.The queen of speakeasies was Texas Guinan, who quipped her way through multiple arrests, always surviving a raid to open another night spot that brought patrons flocking to receive her signature greeting, “Hiya, suckers!” (For more of Texas, see post #83.) But if her series of clubs were the most popular, there were plenty of others in all the boroughs. The most celebrated and frequented were clustered in midtown Manhattan, with 38 on 52ndStreet alone. Prominent among them was the 21 Club, whose final address was 21 West 52nd Street, made famous by its ingenious engineering: in the event of a raid, a system of levers tipped the shelves of the bar, sending liquor bottles through a chute into the city’s sewers. There was also a secret wine cellar accessed through a hidden door in a brick wall, opening into the basement of the building next door. In the 1950s workers expanding the 53rd Street branch of the New York Public Library are said to have encountered the soil there still reeking of alcohol.

Jimmy Walker Other joints of the day included the Hi Hat, the Kit-Kat, and the Ha-Ha Club. Noel Coward liked the elegant Marlborough House at 16 East 61stStreet, where black-jacketed waiters served partying socialites. Fred and Adele Astaire danced at the Trocadero at 35 East 53rd Street, while pilots flocked to the Wing Club at 8 West 52nd Street, and artists to the Artists and Writers Club at 213 West 40th Street. The Central Park Casino, in the Park near the 72nd Street entrance, was the favorite hangout of fun-loving Mayor Jimmy Walker, who spent more time there than at City Hall.

Jimmy Walker Other joints of the day included the Hi Hat, the Kit-Kat, and the Ha-Ha Club. Noel Coward liked the elegant Marlborough House at 16 East 61stStreet, where black-jacketed waiters served partying socialites. Fred and Adele Astaire danced at the Trocadero at 35 East 53rd Street, while pilots flocked to the Wing Club at 8 West 52nd Street, and artists to the Artists and Writers Club at 213 West 40th Street. The Central Park Casino, in the Park near the 72nd Street entrance, was the favorite hangout of fun-loving Mayor Jimmy Walker, who spent more time there than at City Hall.But New Yorkers had other ways as well of coping with Prohibition. Nathan Musher’s Menorah Wine Company imported 750,000 gallons of fortified Malaga wine that, certified as kosher, he sold to “rabbis” with sacramental wine permits, some of whom sported such names as Houlihan and Maguire. In a more sinister mode, Meyer Lansky’s car and truck rental business in a garage underneath the Williamsburg Bridge became a warehouse for stolen goods and rented out vehicles to bootleggers. Lansky went on to become a major gangland figure, associating with such stellar operators as Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano; as a Jewish gangster, he figures in my eyes as a supreme example of successful assimilation.

As time passed, enthusiasm for Prohibition waned. Far from reducing crime, as had been hoped, it promoted it by creating a bootlegging industry dominated by ruthless warring gangs. Far from eliminating alcoholic consumption, it made it fashionable and prompted the fair sex to join their lusty males in imbibing. Flouting the law was “in,” it was fun. Nor was Prohibition an inducement to better health, since drinking bad booze from a bottle with a counterfeit label could on occasion be lethal.

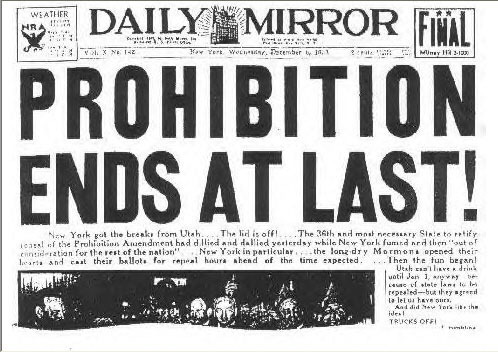

The coup de grâce for Prohibition came in October 1930, just two weeks before congressional midterm elections, when the bootlegger George Cassiday contributed five articles to the Washington Post telling how for the last ten years he had supplied booze to the honorable members of Congress, of whom he estimated that 80 percent drank. As a result, in the following election Congress shifted from a dry Republican majority to a wet Democratic majority eager for the Eighteenth Amendment’s repeal. To bring that about, states began ratifying the Twenty-first Amendment. In New York City anticipation mounted, and bystanders were astonished or amused to see phalanxes of sturdy matrons, who incidentally now had the vote, marching together under bold-lettered signs: WE WANT BEER! Yes, the times had changed. On December 5, 1933, the Twenty-first Amendment was ratified, thus repealing at last the now despised Eighteenth; New Yorkers cheered … and drank.

There are many morals to this story, chief among them the folly of imposing morality from above by law, when vast numbers of those below have only scorn for the law enacted. For better and for worse, New Yorkers have always guzzled, and surely always will.

And so … Cheers! Salute! Prosit! A la tienne! Salud!

demi

demiA note on WBAI: The listener-supported, commercial-free radio station that I love and hate (see post #16) continues to stagger on, celebrating its successful fund drives while pleading desperately for more contributions. There is even talk of some kind of leasing arrangement that, to my mind, would change the station completely. Likewise indicative of its dire straits is the proliferation of imported talent, presumably at little or no cost, replacing familiar programs in hopes of reaching a wider audience. One such is the Thom Hartmann program, its host an ego-driven, self-promoting talk-show host whose heart, if not his head, is in the right place. Nothing so grates on me as the periodic announcement in a resonant voice, “This is the Thom Hartmann program!” And his grandiose statements, always in a worthy cause, that seem just a bit inflated and flimsy.

An example of the latter: recently he proclaimed that the 1929 Crash and the Depression that followed “destroyed the middle class.” Really? I was there; he wasn’t. In the 1930s, as a kid growing up in a middle-class suburb of Chicago, I was aware of modest living but no destruction. My father was a lawyer with a big corporation in Chicago; we watched our pennies but certainly survived the Depression. Our neighbors on the block included the successful owner of a small company that made paper boxes, a dentist, a night editor with the Chicago Tribune, an insurance man, and other businessmen, all of whom, except the dentist, commuted to jobs in Chicago. To the south lay the city of Chicago, with its share of Depression misery, and to the north a series of lakefront suburbs with higher incomes and more imposing residences. In between, we were very middle middle class and by no means ruined.

Mr. Hartmann’s dramatic assertion to the contrary is typical of WBAI, where grandiose negative statements and predictions of dire imminent catastrophes abound. Frequent among the latter: a coming financial collapse far exceeding the recent one, and the dollar’s ceasing to be the dominant world currency. All of which may be true – I certainly anticipate a serious correction in the market, if not a full-fledged bear market -- but then, there’s the story of the boy who cried “Wolf!” But my measured skepticism includes no trace of gloating. The commitment of WBAI’s dwindling staff is remarkable, and the station continues to broadcast many news stories neglected by mainstream media, as for instance poverty in America and the threat of the Transpacific Partnership, now being secretly negotiated, which would seriously undercut our national sovereignty. I criticize the station, but I need it; it is unique.

Coming soon (though in no particular oreder): The mayors of New York (a colorful bunch); Andy Warhol (genius or fraud?); lighting the city (from candles to neon signs); transportation in the city (the kinds of carriages and what they signified, the first gas buggies, the subway); foreign influences on nineteenth-century New York (the mansard roof, hoopskirts, the ascot tie, the derby, lager beer, the polonaise, even a Chinese junk).

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on November 17, 2013 05:26

November 10, 2013

99. Along the Docks, circa 1870

This post will take us on a tour of the North River (Hudson River) and East River docks on a summer day circa 1870. Our waterfront today has been prettified with parks and bike paths and dog runs and tennis courts. Now we’ll see what it looked like circa 1870. We’ll start on the North River at 34th Street and stroll south along West Street to the Battery.

34th Street, North River. Moored beside a pier is the offal boat, a small sloop piled high with the smelly carcasses of horses, cows, pigs, dogs, and cats that died in the city’s streets. Scattered on the pier, barrels and tubs and hogsheads of blood and entrails from the slaughterhouses. The offal boat will take this smelly cargo upriver to a bone-boiling plant that will turn it into leather, manure, soap, fat, and bone for soup and buttons. So 1870 New York was recycling already. Nothing for us to worry about today, since the internal combustion engine has supplanted horsepower in all but name. Or is there? What becomes of all those derelict cars and trucks? Have you ever seen an automobile graveyard with its acres of rusting vehicles? Those graveyards are always expanding, taking ever more space. Will there always be enough space? How will it ever end? Hmm… But let’s get back to the 1870 waterfront. It’s rather smelly here on this pier, so let’s move along.

Below 34th Street. Brigs unloading bushels of potatoes. Workers taking loads of cabbages from canal boats and tossing them into wagons. Unloaded heaps of fruit. Hungry street kids snatch a peach or two and flee.

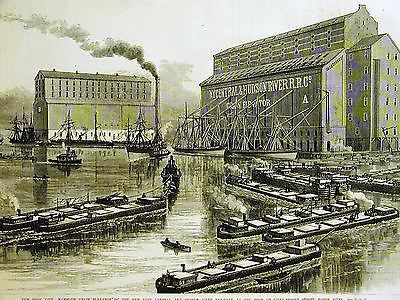

A mammoth grain elevator, a huge hulking wooden structure that dwarfs every other building in sight, where a steam-driven belt with buckets scoops up loose grain from the hold of a canal boat and hoists it up into its cavernous interior, where it will be stored temporarily in bins, then delivered through spouts into the hold of an ocean-going steamer for delivery to the England and Holland and Germany. So grain from distant Ohio and Indiana, tens of thousands of bushels of it, finds its way to New York by barge via the Erie Canal and is hauled down the Hudson River by tugs to New York, where it is transshipped and sent to Europe to feed hungry populations no longer able to feed themselves. New York City is essential to global trade.

A mammoth grain elevator, a huge hulking wooden structure that dwarfs every other building in sight, where a steam-driven belt with buckets scoops up loose grain from the hold of a canal boat and hoists it up into its cavernous interior, where it will be stored temporarily in bins, then delivered through spouts into the hold of an ocean-going steamer for delivery to the England and Holland and Germany. So grain from distant Ohio and Indiana, tens of thousands of bushels of it, finds its way to New York by barge via the Erie Canal and is hauled down the Hudson River by tugs to New York, where it is transshipped and sent to Europe to feed hungry populations no longer able to feed themselves. New York City is essential to global trade.Farther along, everyone looks black, like a team of grimy demons: men in undershirts, smirched with coal dust, in the hold of a canal boat, shoveling coal into buckets that are raised mechanically to the dock. That coal from the mountains of Pennsylvania, brought to the city via the Delaware and Hudson Canal, will be carted off and dumped in cellars, then fetched up in buckets and pails to burn in fireplaces with an orange glow, giving heat. Or shoveled into furnaces to heat the boilers that make steam to drive the pistons of steamboats and locomotives, becoming power and speed. Like all Americans, New Yorkers are awed by power, while speed makes them giddy and drunk.

Next, an iron works. From the outside we see flames leaping in a dark interior, and hear giant machines screech and groan and pound. Iron from western Pennsylvania, to be shaped into shafts to reinforce buildings that can now be taller and feature large glass display windows to tempt hordes of shoppers along Broadway. Or made into boilers and propellers and sugar mills and lathes, or steel rails for railroads sprinting across prairies and deserts and mountains all the way to the blue Pacific. Or melted and poured from vats into molds for marine engines with a white-hot hiss and glare that parches the face of onlookers and inspires in them visions of hell.

Inside an iron works: the forges.

Inside an iron works: the forges.And now a lumberyard with whining steam-powered saws. And a monster of a cotton press, its giant jaws clamping on a bale of cotton, compressing it to one foot thick. Seventy bales an hour of Southern cotton to be shipped to the mills of Manchester and Leeds to be turned into muslins and calicoes that will be shipped back to New York and sent by rail to the rest of the nation. Likewise shipped to New York will be silks and ribbons and laces from Lyons for the adornment of ladies of fashion, of whom New York has an inordinate number, all inordinately eager for the latest French fashions and frilled bonnets whose cost puts a grievous dent in their husbands’ budget but proclaims to the world that they are in the vanguard of fashion, they are chic, they are “in.”

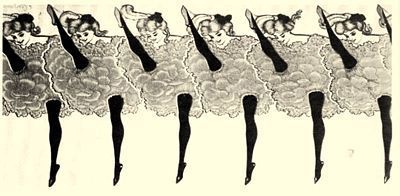

Fashions of the 1880s, or, why the textile mills of Europe kept busy.

Fashions of the 1880s, or, why the textile mills of Europe kept busy.Sugar refineries towering twelve stories high refining raw sugar brought to the city by brig and schooner from the slave plantations of Cuba; piles of brownstone and brick hauled in by sloop from the nearby counties, to be used in the elegant houses of the affluent; and distilleries producing tiger’s milk, diddle, or the oil of joy (we had countless names for it) to sate the lusty gullets of Americans.

Inside a sugar mill: cooling and barreling the sugar.

Inside a sugar mill: cooling and barreling the sugar.The “Hotel de Flaherty,” a tin-roofed shed patched together with wood, stone, mud, and plaster, offering overripe apples, dusty candy, and smoked sausages at 2 cents each, while hogs grovel outside by the door. Mr. Flaherty’s establishment doesn’t tempt us, we move on.

Ice wagons loading ice from barges at a dock. The ice, harvested the previous winter from the upper Hudson by ruddy-faced men with hand saws who cut it into chunks 12 inches thick, has been stored in sawdust-insulated huge dark riverside barns and now, tugged downriver on hundreds of barges, it will be hooked into wagons and hustled off by whip-cracking drivers through the steaming summer streets, to be tonged into homes or slid down ramps into cellars of fancy restaurants and hotels. Even without refrigeration New Yorkers will have their frothy cold schooners of beer in beer gardens, their fine white wines at Delmonico’s, the prince of restaurants, and the chilled lemonades and tinted sherbets that they sip and nibble genteelly in ice cream parlors on Broadway.

The New York City ice trade, all phases.

The New York City ice trade, all phases.18th Street. The looming retorts and gas holders of the Manhattan Gas Company. Ugly, sprawling, and smelly, gas works are located on the waterfront, far from the city’s fine residences. Here, coal is scooped into red-hot retorts and burned there and

Inside the retorts of a gas works. Not something you would

Inside the retorts of a gas works. Not something you would want near your residence.its vapors carried off to be stored in gas holders, giant bulbed bellies of iron, then conveyed through underground pipes to hotels and restaurants and the bibelot-crammed homes of the rich. There it becomes light, glowing from globed chandeliers, or from polished glass boxes of streetlamps along the Fifth Avenue and Broadway and other thoroughfares where lamplighters light them at twilight and snuff them at dawn. Thanks to gaslight, pickpockets work in the evening, hotel lobbies glow, and Fisk’s Opera House presents in a stellar glare imported Spanish dancers, music by Offenbach, and cataracts with real water, climaxed by 100 Beauties 100 hiking their ruffled skirts, as 200 shapely legs kick high in that talked-about scandal from Paris, the TERPSICHOREAN AEROSTATICS OF THE DEMON CANCAN.

Yes, gaslight helped.

Yes, gaslight helped.Just offshore, a towering floating derrick with cables and pulleys that with only 1 horsepower and five men has lifted a sunken boat laden with 300 tons of coal. Once again, the machine has triumphed.

11th Street. You think you’ve experienced noise and bustle so far? Hardly. Here we leave the quieter docks – yes, quieter -- dealing with grain, lumber, sugar, iron, and ice, and come to the docks of the shipping lines linking New York to Boston and New Orleans and San Francisco and Liverpool and Le Havre and Hamburg and Canton and Jakarta and Bombay. Surging across West Street come arriving and departing travelers, porters carrying baggage, and clerks with letter bundles scurrying after captains toting mailbags, all of them fighting past wagons blocking horsecars blocking stages amid shouts and curses of drivers, lumber spilling from a cart, mountains of barrels and bales, a black-garbed minister distributing tracts and Bibles to whoever will take them, and smells of fish, brine, tar, and molasses.

The oyster market. Rows of anchored oyster boats where men pry open oyster shells with knives, toss the oysters in pails of water. Wagons take on loads of baskets of oysters that will be consumed by New Yorkers everywhere, in fine and not-so-fine restaurants, in oyster cellars, and even at stands in the street, as they relish glistening blue points on crushed ice with a wedge of lemon, or plump saddle rocks plucked from the groin of the sea.

Slips where Coney Island sand is stored, so housewives can scour their pans and kettles and keep them bright. Sand too for the floors of saloons, where untutored males of the lower classes, and even some tutored males of the upper classes, still have a habit of spitting.

10th Street. Winches rattle, tackles run, officers whistle and gesticulate and halloo, as a gang of men in a hold strain to hoist a huge mahogany log out with tackle. Mahogany from the steaming jungles of Honduras will be used in the fine furnishings of the palace steamboats of the People’s Line, where ordinary Americans can revel in luxuries reserved for the wealthy and titled in Europe.

Under the piers of these docks are dense forests of pilings that only the smallest skiff can negotiate, a hidden world shadowy even by daytime where harbor thieves hide stolen goods that they hope to sell to licensed junkmen in boats who ask no questions. From time to time policemen search under the piers and clean out the stashes of stolen goods, but more goods will be stashed, and the game goes on.

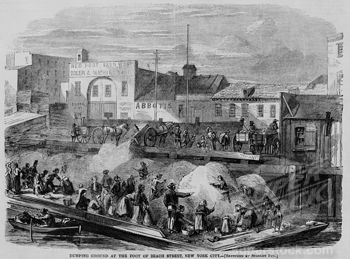

Below Canal Street, a garbage dump where a long line of carts on a high pier dump refuse onto a lighter moored below. Crawling over the huge mound of trash like a horde of maggots are men, women, and children scavenging bones, coal, rags, and old metal to sell to peddlers, and even scraps of food that they devour greedily. Smells of burnt wood, ashes, shit.

The Albany boat landing, where fashionables leaving for Saratoga scramble aboard amid the hubbub of cart drivers, cabs, baggage men, vendors, and the roar of escaping steam from the boats. By August, everyone who is anyone flees the heat of the city, leaving behind the budget-strapped unfortunates who can only pull their front curtains shut and avoid being seen on the street, so the neighbors will think that they too are enjoying the amenities of Long Branch or Saratoga. So it is in this distant time before air-conditioning.

The Washington Market, between Vesey and Fulton Streets. A sprawling old structure topped by a belfry. In the early morning, a jam of wagons heaped high with meat from the Jersey slaughterhouses, produce from the garden patches of uptown shanty dwellers, and butter and cheese from Westchester farmers, all of them clattering down the narrow muddy lanes between the stalls where their crates, baskets, and barrels are unloaded while geese honk and chickens cluck.

Gray-smocked vendors hawk their wares: dangling from hooks, carcasses of beef, deer, ducks, turkeys, rabbits, even the huge shaggy bulk of a bear; glistening heaps of silver-gray fish; huge yellow mountains of cheese; and baskets of peaches, plums, onions, and potatoes attended by ruddy-faced market women in broad-brimmed hats. The first buyers flock: caterers from the best restaurants and hotels, among them Lorenzo Delmonico in a dark coat and top hat, scrutinizing the soft velvet plumage of a heap of fowl, pinching and sniffing, then tossing one bird, then another, into a wicker basket, his spoils destined for the tables of the city’s fanciest restaurant, the fabled Delmonico’s on 14th Street. There, railroad men and politicians and foreign visitors and the city’s elite dine genteelly in the evening in a high-ceilinged room lit by crystal chandeliers, at tables with gleaming crystal and silverware, served by waiters who glide noiselessly over deep-pile carpet. Yet even as Lorenzo Delmonico makes his careful selection, barefoot boys and old women pick at garbage sweepings nearby that even dogs reject.

At last, an island of silence, a plenitude of calm: the Battery, with its fine view of the river and harbor, where smoke-belching steamboats mingle with three-masted sailing vessels and smaller schooners and sloops, and ferries plying to and from Brooklyn and Jersey and Staten Island, and even rowboats here and there. But did I say peace and quiet? An old woman tending a peanut and pineapple stand suddenly erupts at some visitors: “Get out wid ye, spittin’ all over me pineapples! Do yees think I’ve got nothin’ to do but be washin’ me slices all day after yees?” We move on.

The Battery, 1872. A Currier & Ives print.

The Battery, 1872. A Currier & Ives print. From here we’ll continue our imagined walk up South Street along the East River circa 1870 and see what today’s South Street Seaport, a historic district with renovated commercial buildings and sailing ships, can only give a hint of.

North of Market Street, bowsprits of anchored sailing vessels jut high in the air overhead, while stevedores hustle huge bales and barrels and crates onto wagons and off of them, and iron-wheeled drays clatter on cobblestones amid smells of whale oil and sawn wood and brine. Facing the docks are rows of old brick buildings housing sparmakers and riggers, and sailmakers’ lofts over the offices of shipping lines, and ship chandleries with everything needed for a ship: barometers and sextants and quadrants; cordage, paint, canvas, and oils; buoys and bells, windlasses and bilge pumps; and even cutlasses and axes that conjure up visions of seamen in old sailing vessels fighting off boarders from a British man-o’-war, or hordes of pirates armed with poisoned darts in the Sunda Straits. Forges glow in ship smith shops where hammers clang on anvils, saws whine in spar yards, as shipwrights shape long timbers into spars, and a crowd of ragged boys watch, wide-eyed, as an aproned figurehead carver with a hammer and chisel hews out the shape of a bare-breasted sea nymph to adorn the bow of a ship. Here, even in this age of steam, the age of sail still holds.

South Street, 1827. The heyday of sail, before steamships began crossing the Atlantic.

South Street, 1827. The heyday of sail, before steamships began crossing the Atlantic.Above Wall Street, a brig from the Guinea Coast of Africa, having survived the deaths of a mate and two crewmen from yellow fever, unloads palm oil to be used in soaps and as a lubricant, and ivory needed for billiard balls, fancy buttons, jewelry, and the keys of pianofortes, fingering which young ladies in hushed parlors demonstrate their genteel accomplishments to guests. (Which brings to mind an old joke: “What do you think of her execution?” “I’m in favor of it.”)

At the foot of Pike Street, huge dry docks side by side. Using a steam engine, four men jerk a ship up out of the water for repairs. In the next dock over, two hundred workers peg away at a steamer’s bottom, scraping off barnacles, cleaning and repairing it.

Pier 54, at the foot of Grand Street. Huge blocks of Italian marble are hoisted from the holds of vessels by creaking windlasses, to be taken by cart to the marble cutters, who will saw and hew them into smaller blocks and slabs that will become ornamental fronts of houses, baptismal fonts for churches, and monuments to the dear departed. But some blocks are destined for studios where home-grown Michelangelos will labor to transform the frumpy consorts of Chicago hog butchers and Pennsylvania oil barons into sculpted magnificence, into music of stone.

Near 12th Street, a sudden hush: the coffin of a skipper dead of a fever at sea is being borne down the gangplank of a ship. Stevedores stand silent, hats off, until a hearse bears the coffin off. Then, just as suddenly, the noise and bustle resume.

We could go on a bit along South Street and see more shipyards and iron foundries and gas works, but this would simply repeat, and it’s late in the day and we’re tired, so we’ll end our tour here.

Day’s end: sunset on the North River and East River docks. In the fading ruddy glow, piers grow dim and anchored ships loom with darkened hulls and rigging, and water shines with the blackness of night. Straggling teams pass with the last loads of the day, then silence. Watchmen make their rounds, yawning; suspicious shadows skulk; gruff sounds from a groggery; ragged street kids fall deep asleep on cotton bales; harbor thieves in small boats glide noiselessly, on the lookout for unguarded spoils. A brief repose for the docks until, in the wee morning hours, the first market wagons lurch and grate and creak.

Such were the docks circa 1870, when city and nation were in the throes of the Industrial Revolution, with machines taking on more and more tasks once performed by men and horses and mules. At the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, multitudes flocked to Machinery Hall to see machines press bricks, pump water into thundering Niagaras, spin cotton, print newspapers, drill metal, grind bone into dust. And some giant Krupp cannon as well. “What will you do with all these things?” wondered Thomas Huxley, the English champion of Darwinism. Today we might ask the same of cell phones and laptops and tablets.

Krupp artillery at the Exposition. What will you do with all these things?

Krupp artillery at the Exposition. What will you do with all these things?In this case, the answer came in 1914.

But the New York of 1870 knew what to do with machines and ships and docks. It was not neat or subtle or just, but it did things. It transshipped huge quantities of goods and turned iron into boilers and sugar mills, marble into memorials, ivory into piano keys, offal into leather and glue, and smirchy coal into the miracle of light. Then as now there were thieves and cheats and manipulators, but the city did things, and did them big.

Today the waterfront has dog walkers, joggers, cyclists, and sunbathers, but no grain elevators, sugar refineries, iron works, or dry docks. What happened? First, competing ports offered services at lower cost; New York always was – and still is – an expensive place to do business. Next, railroads, and later trucks and airlines, took on traffic that once went by water. In the twentieth century racketeers got control of the unions, with little concern for maintenance of the waterfront, or for damage to the port’s reputation. And from the 1950s on, containerization came in, requiring more space than the port of New York could offer, so that a lot of business went to the vast facilities of the port of Newark. After that, much of the waterfront fell into decay, until the current movement to restore it and use it for recreation. Once dirty and cluttered and busy, now it is clean and green.

Containers at the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal. New York could offer no

Containers at the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal. New York could offer nosuch space as this.

Source note: Much of this post is drawn from my unpublished historical fiction, which draws on primary sources that include old prints of the time and two articles by journalists who described a day’s walk along the docks.

Election results: As expected, New York City has a new mayor – a Democrat, after all these years! Bill de Blasio, who stands 6 foot 5, promises many longed-for changes, and multitudes cheer. This is the honeymoon; it won’t last long. Being mayor of this city is not the pleasantest job. New Yorkers love to croak and complain, and the mayor spends half his time in Albany, begging the governor and legislature to let him raise a tax or two or otherwise attempt to govern. And it’s a dead-end job: to my knowledge, no mayor has ever become a presidential candidate, whereas many a New York State governor has aspired to the White House, and a few have even succeeded. So we’ll see how our 109th mayor fares.

Coming soon: Guzzling New York, and why Prohibition has never succeeded here; the city’s long-term romance with the oil of joy. After that: mayors of New York, including the most honest, the most corrupt, the most elegant, the most good-looking, the most fun-loving. In the offing: Lighting in the city; from candles to neon signs. And transportation: how New Yorkers did – and didn’t – get around; gigs and landaus and broughams, horsecars and stages, races and jams (not the kind you eat), the first gas buggies, the horrors and delights of the subway.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on November 10, 2013 05:23

November 3, 2013

98. My Suicides and Further Thoughts on the Subject