Clifford Browder's Blog, page 47

April 6, 2014

121. Famous Deaths, part 1

New York is a place people come to in order to have fun, to find themselves, to make their way in the world, to live. But, as chance or fate would have it, it is also a place where people – often famous people – die. This post is about the last years and death here of four people famous in their time. Three died in the West Village, where I reside. To a considerable extent they were all responsible for their demise.

Alexander Hamilton

A Founding Father and influential supporter and interpreter of the Constitution, Secretary of the Treasury in George Washington’s cabinet, and founder of the Federalist Party, Hamilton had had to leave the cabinet following the revelation of his involvement in an adulterous affair. (Yes, it happened back then, too.) Living in a villa in Manhattan just north of New York City, he was still involved in the vituperative politics of the day, and had incurred the enmity of Aaron Burr, whom he viewed as an unscrupulous opportunist.

A Founding Father and influential supporter and interpreter of the Constitution, Secretary of the Treasury in George Washington’s cabinet, and founder of the Federalist Party, Hamilton had had to leave the cabinet following the revelation of his involvement in an adulterous affair. (Yes, it happened back then, too.) Living in a villa in Manhattan just north of New York City, he was still involved in the vituperative politics of the day, and had incurred the enmity of Aaron Burr, whom he viewed as an unscrupulous opportunist.

Burr is a fascinating character about whom opinion differs to this day. A brave soldier and shrewd lawyer, he had polished manners and magnetic charm, and was immensely attractive to women, but he was also ambitious and scheming in politics, and not one to endure a slight. He and Hamilton had long been political rivals, and Hamilton had often thwarted his ambition. Now, alleging insults in print, Burr, who was Vice President under Thomas Jefferson, challenged Hamilton to a duel. Dueling was outlawed in both New York and New Jersey, but with milder consequences in New Jersey. Hamilton, who was illegitimate, was touchy on the subject of honor and so declined to defuse the situation.

At dawn on July 11, 1804, the most famous duel in American history took place on a deserted rocky ledge in Weehawken, just across the Hudson in New Jersey. Both fired, and almost simultaneously, but who fired first is unclear. Hamilton seems to have intentionally missed Burr with his shot, but Burr was a crack marksman and his shot tore through Hamilton’s liver and shattered his spine. Hamilton, who knew he was mortally wounded, was ferried back to New York and taken to the home of a friend at what is now 80-82 Jane Street (but a few doors down from where I lived in the 1960s). After great suffering, on the following afternoon he died there, age 49, surrounded by weeping family and friends.

An old print with some inaccuracies. Only the two seconds were present. The clothing is typical of the 18th century, not of the early 19th.

An old print with some inaccuracies. Only the two seconds were present. The clothing is typical of the 18th century, not of the early 19th.Hamilton’s funeral two days later was a municipal event, for he had long practiced law in the city and was well known to the citizens. Business was suspended, and muffled bells tolled from dawn to dusk. At noon the long funeral procession, which included military officers, students, merchants, lawyers, politicians, tradesmen, and ordinary citizens, wound through the streets toward Trinity Church, where he was to be buried, while warships in the harbor fired guns, and merchant vessels flew their flags at half mast.

Fearing a mob attack on his house, and charged with various crimes, including murder, in both New York and New Jersey, Burr decamped for fairer pastures; the charges were eventually dropped. But the duel ended his political career, since he never ran for office again after his term as Vice President ended in 1805. In 1807 he would be tried for treason on questionable charges regarding an alleged conspiracy on the Western frontier, but he was acquitted. For a while he tried without success to regain his fortunes in Europe, after which he returned to the U.S. and resumed his law career in New York. In 1833, at age 77, he married the wealthy widow Eliza Jumel, no doubt with an eye to her fortune; that fortune was greatly diminished through a speculation he undertook, and she soon filed for divorce. Burr then suffered a stroke and died in a boarding house on Staten Island in 1836, on the very day the divorce was granted.

Gore Vidal’s historical novel Burr (1973) is an interesting interpretation of the man, whom he depicts as an honorable eighteenth-century gentleman while disparaging Hamilton and others. Burr has his defenders, who suggest that Hamilton fired first, and when Burr heard the bullet whiz by his ear, he thought Hamilton had meant to hit him and so fired in self-defense. But the majority opinion is that he meant to kill Hamilton. Late in life, though, he said, “Had I read [Laurence] Sterne more and Voltaire less, I should have known the world was wide enough for Hamilton and me.”

As for Madame Jumel, whose mansion in upper Manhattan survives and is open to the public, she rates a post, or at least a good part of one, all her own.

Decades after Hamilton’s death his aged, white-haired widow, garbed in widow’s black and living quietly in Washington, worked hard to rescue her husband’s reputation from slanders by his political enemies. Showing visitors about the house, which was crammed with faded memorabilia, she would pause reverentially before a marble bust of Hamilton, the work of an Italian sculptor who presented him as a Roman senator with a toga draped over one shoulder.

In 2004, the bicentennial anniversary of the duel, descendants of the two opponents staged a re-enactment of the duel near the Hudson River before more than a thousand spectators.

Stephen Foster

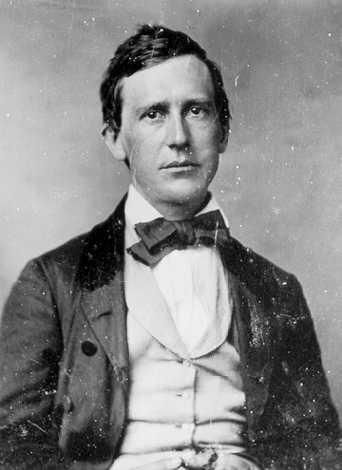

Though he has been hailed as the “father of American music,” Stephen Foster derived little income from his music, since publishers often printed editions of his songs without paying him a cent. Struggling with alcoholism, depression, and debt, in 1860 he moved to New York, the center of musical publishing, but his wife and daughter soon left him – as they often had before -- and returned to Pittsburgh. He published many songs here, but they were mediocre and sold poorly. Living at the North American Hotel at 30 Bowery on the Lower East Side – some have called it a flophouse -- he became impoverished. Still composing, he would pick out tunes on an old piano in the back room of a German grocery on the Bowery. In January 1864 he was stricken for days by ague and fever, then fell while washing and dashed his head against the wash basin; the chambermaid found him lying in a pool of blood. Taken to Bellevue Hospital, he died there in the charity ward on January 13, age 37. His wallet contained a scrap of paper that only said, “Dear friends and gentle hearts,” plus 38 cents in Civil War scrip and three pennies. He was buried in his native Pittsburgh. Ironically, one of his most acclaimed songs, “Beautiful Dreamer,” was published soon after his death.

Though he has been hailed as the “father of American music,” Stephen Foster derived little income from his music, since publishers often printed editions of his songs without paying him a cent. Struggling with alcoholism, depression, and debt, in 1860 he moved to New York, the center of musical publishing, but his wife and daughter soon left him – as they often had before -- and returned to Pittsburgh. He published many songs here, but they were mediocre and sold poorly. Living at the North American Hotel at 30 Bowery on the Lower East Side – some have called it a flophouse -- he became impoverished. Still composing, he would pick out tunes on an old piano in the back room of a German grocery on the Bowery. In January 1864 he was stricken for days by ague and fever, then fell while washing and dashed his head against the wash basin; the chambermaid found him lying in a pool of blood. Taken to Bellevue Hospital, he died there in the charity ward on January 13, age 37. His wallet contained a scrap of paper that only said, “Dear friends and gentle hearts,” plus 38 cents in Civil War scrip and three pennies. He was buried in his native Pittsburgh. Ironically, one of his most acclaimed songs, “Beautiful Dreamer,” was published soon after his death.Dylan Thomas

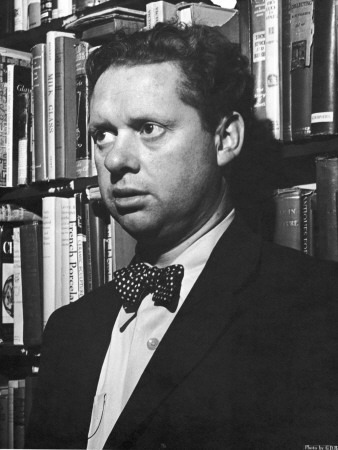

Another victim of alcoholism who died in New York was the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, but unlike Stephen Foster he went out with a bang. His demise was well observed and well recorded.

Another victim of alcoholism who died in New York was the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, but unlike Stephen Foster he went out with a bang. His demise was well observed and well recorded.I first heard of Thomas when, in my senior year at college, he came to our campus to do a reading. This was his first American tour and, like so many Europeans before him (Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde), he came here to make money. He was lauded to us by our English teachers as a great poet who had renewed English poetry with his rich lyricism and imagery, and we flocked to the campus’s concert hall to hear him. Thomas was alcoholic by now, and the faculty had been warned that he was marvelous on the stage, but impossible off. We would learn later that, following a dinner with the English faculty before the reading, he had roundly cursed the Dr. Strathman, the head of the English Department, when, eyeing his watch, Strathman had dragged the poet away from his last beer.

The reading was indeed marvelous. His rich, resonant voice projected clearly as he read poems by Yeats and others, and then his own. I couldn’t begin to untangle the lush Celtic tapestry of words, so I just let it flow over me. Then, at the end of the reading, Dr. Strathman announced that Thomas would be glad to talk with students and answer questions. We all gathered diligently around him, and he got things off to a vibrant start by turning around to confront the pipes of a large organ behind him.

“Good God!” he exclaimed. “I didn’t know there was an organ bigger than mine in here!”

Questions followed, with answers more arch than frank. I was too inhibited to venture any, but a girl said, “Mr. Thomas, I didn’t hear what you said that one poem was about.”

“That’s the first time anyone has said they couldn’t hear me,” he resonated. “I said it was about masturbation.”

Dead silence. Hip, with-it college students that we were, we weren’t prepared for this.

“Oh,” said the girl, flustered. “Well, uh, masculine or feminine?”

“Masculine or feminine?” he boomed. “Does a woman go off like a rocket?”

There then followed a sonorous explication as to why it had to be masculine. We listened in stark silence, stupefied.

So ended my first and only encounter with Thomas, though the campus crackled with accounts of the reading for days afterward. And when I went into the English Department the next day for a bit more enlightenment, Dr. Strathman, a serious scholar, announced that, if Thomas continued drinking, he would cease to develop as a poet. Which subsequent events bore out. “And I noticed that when he got the check for the reading,” he added, “it went into an inside pocket. At that moment, at least, he knew what he was doing.”

After that I went to France and for two years immersed myself in the writings of the Gauls, which enticed me away from Thomas and other English-language writers. And when I came to New York in the fall of 1953 to pursue graduate work in French at Columbia, I was so preoccupied with my studies far uptown, and with discovery of the fascinating, distracting, and baffling city of New York, that I barely noticed the sad last chapter of the Welsh poet’s life, which played out right here in the West Village, where I would reside from the 1960s on.

This was the fourth time Thomas had come over here to make money, and to drink. When he arrived by air on October 20, those welcoming him were shocked by how pale and shaky he looked; he was obviously in poor health. He checked in at the Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street, where many writers, artists, musicians, and actors have lived. He then attended a rehearsal of his radio play Under Milk Wood at the Unterberg Poetry Center of the 92ndStreet Y, following which he made a beeline for his favorite bar, the White Horse Tavern, at the corner of Hudson and West 11th, just one block from where I now live, a bar long popular with writers and artists. During subsequent rehearsals he was obviously sick and on one occasion collapsed.

The White Horse in 1961. A hangout for writers and intellectuals,

The White Horse in 1961. A hangout for writers and intellectuals,real and pseudo. One short block from my building, but I never

took to it. On November 3 he spent most of the day in bed, drinking. Late that night he went again to the White Horse, drank heavily, then returned to the Chelsea, where he announced, "I've had eighteen straight whiskies. I think that's the record." (The White Horse's barman and owner later observed that he couldn't have had more than half that amount, which for most of us would still be a record.) After more drinking on November 4, his breathing became labored and his face turned blue. Alarmed, at midnight November 5 his friends summoned an ambulance.

He arrived at Saint Vincent's Hospital in a coma. Informed, his wife Caitlin flew at once to New York and was taken to the hospital. "Is the bloody man dead yet?" she asked upon arriving there. Returning later that day, drunk, she threatened to kill John Brinnin, who had organized Thomas's tour; when she became uncontrollable, she was put in a straitjacket and committed to a psychiatric detox clinic on Long Island. It is said that the young Beat poet Gregory Corso, who had been born at Saint Vincent's, tried to get into Thomas's room so he could see how a poet dies, but was chased away by the nurses. Still in a coma, Thomas died at noon on November 9. Surprisingly, a post-mortem gave as causes of death pneumonia, brain swelling, and a fatty liver, with no mention of alcoholism. Caitlin's autobiography states, "Our only true love was drink. The bar was our altar.”

Thomas had long been buried in the churchyard of Laugharne, the fishing village in Wales where he resided, when, stealing time from my French studies, I read the slender volume of his poetry, and reread and reread it, until I at last got a take on it, separating out the mediocre stuff from the good stuff, and the good stuff from that handful of truly great poems on which his reputation, I was convinced, would rest. He wasn’t easy – in fact, he was obsessively and needlessly obscure, a thick tangle of words and images – but I fought through until I found something solid, something that would last. Alone of all my friends I became, always with reservations, a devotee, and still am to this day. As for Under Milk Wood, the radio play he wrote for the BBC, I have seen it done here in a stage version and found it richly rewarding. It takes place in the fictional Welsh town of Llareggub, a name that sounds convincingly Welsh, until you spell it backwards and discover, once again, a trace of the poet’s whimsical humor.

Sid Vicious

Another resident of the Chelsea Hotel was the English guitarist and vocalist Sid Vicious (needless to say, an assumed name), who in 1978 was touring the U.S. with the punk group Sex Pistols (a name that, when I first heard it, struck me as the ultimate in protracted adolescence). He had been with the group since 1977 and was described as having the “iconic punk look,” his nails painted with purple nail polish, his hair wild. What he lacked in musicianship – and he evidently lacked a lot -- he is said to have made up in “unmatched punk charisma,” which evidently involved spitting and hurling insults at the audience; he had already been arrested in Britain for assault. Vicious’s mother, an addict herself, had been supplying him with drugs and paraphernalia for years, which goes to show that mother love hath no limits.

A new chapter in his life opened on the morning of October 12, 1978, when he awoke from a drugged stupor to find his American girlfriend, Nancy Spungen, herself an addict and onetime prostitute, dead on the bathroom floor of their room in the Chelsea. She had received a single stab wound to the abdomen, causing her to bleed to death. The knife used had been bought by Vicious on 42ndStreet. Arrested and charged with her murder, Vicious admitted that they had fought that night, but gave conflicting versions of what then happened. “I stabbed her, but I never meant to kill her,” he confessed, but then said he couldn’t remember, and also said that during the argument she had fallen on the knife.

His mug shot, when arrested for Spungen's murder in 1978.

His mug shot, when arrested for Spungen's murder in 1978.NYPD

Released on bail, ten days after her death Vicious attempted suicide by slitting his forearm, following which he was hospitalized at Bellevue. In December he was arrested again for smashing a beer mug into a friend’s face during an argument and was sent to Rikers Island jail, where he was detoxified but otherwise languished for 55 days before being released on bail on February 1, 1979. That evening his release was celebrated by a party at the apartment of his new girlfriend Michele at 63 Bank Street. His obliging mother was present and arranged to have some heroin delivered. Vicious overdosed on Mom’s heroin, but the others present got him up and walking about so as to revive him. At 3:00 a.m. he and Michele went to bed. There have been different accounts about the events of that evening, but what’s certain is that he was found dead late the next morning.

Vicious was only 22 when he died. In a 1977 interview he said, “I’ll probably die by the time I reach twenty-five. But I’ll have lived the way I wanted to.” His mother claimed to have found a suicide note in the pocket of his jacket a few days later: “We had a death pact, and I have to keep my half of the bargain. Please bury me next to my baby. Bury me in my leather jacket, jeans and motorcycle boots Goodbye.” Since Spungen was Jewish and buried in a Jewish cemetery, and Vicious wasn’t Jewish, his wish could not be realized. So he was cremated and his mother says she scaled the wall of the Philadelphia cemetery where Spungen was buried and, against the wishes of her family, scattered his ashes over her grave. But another account has Mom tipping over the urn in Heathrow Airport, sending most of the ashes into the airport’s ventilation system. Either way, requiescat in pace. Vicious’s friends blamed his death on Spungen, who, herself suicidal, lured him into a morbidly codependent relationship that became a dance of death. On her deathbed in 1996, Mom confessed that she had deliberately injected him with a lethal dose of heroin, to spare him from going to prison for Spungen’s death. If so, the silver chord again. So ended the family saga.

Vicious died only a few blocks from where I was living (and still am) in the West Village, but the punk scene had so little purchase on my psyche, I was sublimely unaware of the whole to-do. Of course I come off as an old fogy in commenting on the antics of these young fogies. I once saw some kids in the subway with green or pink hair and a sign IF YOU THINK PUNK IS DEAD YOU’RE CRAZY. It wasn’t dead for me. How could it be, since it had never been born?

The Chelsea Hotel: One might think that Thomas’s drunken stay and Nancy Spungen’s murder would have tainted the Chelsea’s reputation as a residence for creative types of all persuasions, but they probably enhanced it. A massive twelve-story, 250-room red-brick building with ornamental cast-iron balconies overlooking West 23rdStreet between 7th and 8th avenues, it opened in 1884 as an apartment coop, later became a luxury hotel, declined after that, but is now a New York City landmark. By the 1950s much of the original lavish décor had been torn out, and the large suites divided into tiny rooms, as the hotel became something close to a flophouse, with low rents sure to entice needy writers and artists, and junkies, pimps, and prostitutes as well.

The Chelsea in 2010.

The Chelsea in 2010.Beyond My Ken

From the early 1970s on the manager was Stanley Bard, who tried hard to keep the rents for writers low, and let impoverished artists pay with art works and a promise to settle the balance in cash when their circumstances improved. In Bard’s time the Chelsea was a very special place, like no other hotel in the city. There might be prostitutes and pimps on one floor, and the black-sheep kids from wealthy families on another, mixed in with budding writers clattering their typewriters, and residents talking poetry or theater. The elevator was notoriously slow, and a naked girl might run into it and out again, no explanation given. Occasionally someone committed suicide by jumping down the grandiose stairwell, or an angry lover would set fire to a partner’s mattress or fancy shirts, sending black smoke swirling up the stairwell, and everyone would have to get out of the building. Some residents were downright crazy, and one tenant kept a small alligator, two monkeys, and a snake. Short of murder and mayhem (both of which at times occurred), no one was too far out, too weird, as long as – sooner or later – they paid their rent.

Among the writers who resided there at one time or another were Mark Twain, O. Henry (each time with a different false name, since he was dodging the police), William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Jack Kerouac, Arthur Miller (before and after Marilyn), Quentin Crisp, Gore Vidal (who reputedly had a one-night stand there with Kerouac), Tennessee Williams, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Thomas Wolfe, Charles Bukowski, Brendan Behan – but why go on? Who, for that matter, didn’t live there? And these are only the writers. One could do a similar list for actors and film directors, and another for musicians, and still another for artists. Andy Warhol’s 1966 film Chelsea Girls provides a glance at the life of some of his stars at the hotel, which has been featured in other films as well and in novels.

In the 1990s Bard refurbished the common areas and many of the rooms, so as to restore some of the Chelsea’s old grandeur, and junkies and prostitutes were expelled. With the beginning of the 21stcentury gentrification overtook the neighborhood, rents went up, and well-heeled tenants moved in. To the dismay of residents, in 2007 the new owners replaced Bard as manager, and things began to change. In 2011 the owners announced that the hotel would take in no more guests, pending desperately needed renovations. The paintings and collages that had always adorned the lobby, hallways, and wrought-iron staircase have now been put in storage, doors to empty rooms stand open, and the noise of construction reverberates. Long-time residents remain in the building, some of them protected by rent regulations, but they fear that the new management may want to drive them out. Yet even with the closure looming, on a given Saturday night in 2011 hip-hop blared from one of the rooms, the police rushed in to forestall a reported suicide attempt, and the arrival of a punk girl guitarist with her head shaved on both sides and her Mohawk dyed blond and blue didn’t raise an eyebrow at the front desk, while a longtime resident photographer gave an end-of-an-era party to cheer his neighbors up. “Never a dull moment,” the front-desk clerk observed.

Yes, the Chelsea in its heyday was unique. It could only have happened in New York.

This is New York

Joe Mazzola

Joe MazzolaComing soon: Exiles in New York, part 3: a begetter of floating lovers and upside-down houses, a pianist with five Steinways, an anarchist with a compact, a future emperor, and a renegade priest with a talent for seduction and debt. After that, one more batch of exiles, and at least one more batch of famous deaths in New York, some of whom may surprise you.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on April 06, 2014 04:37

March 30, 2014

120. Exiles in New York, part 2

This post is the second about exiles in New York. It will deal with the Scarlet Sisters and a dragon lady.

The Everleigh Sisters

Exiles of a rather special kind were two sisters who came to New York and in 1913, using the name Lester, bought a brownstone at 20 West 71st Street and resided there for many years. Neighbors had no idea who Minna and Ada Lester really were: the Everleigh sisters who from 1900 to 1911 had run the fanciest brothel in the country on the near South Side of Chicago. As they told it, their father was a prosperous lawyer in Kentucky who had sent them to private schools and given them lessons in elocution and dancing, following which they married two brothers named Lester and left them after a year, Minna complaining that her husband was a brute who tried to strangle her. They then joined a traveling theatrical troupe, performing in melodramas as they toured the country, until, in Omaha in 1898, they came into an inheritance that let them quit acting and launch a new venture: a bordello to accommodate visitors to the Trans-Mississippi Exposition opening there that year. According to the sisters, they were strictly madams and had never offered their charms to the patrons. When the exposition closed and business fell off, they took their earnings and moved to Chicago to establish the fanciest bagnio on the continent, which they were sure would lure customers from far and wide. There, from 1900 to 1911, the Everleigh Club on South Dearborn Street flourished as the most luxurious and profitable house in the country, patronized by men of great wealth and pliant morals, of whom there seemed to be an inexhaustible supply.

Ada in 1895. She achieved the wasp waist. Such was their story, prior to coming to New York as the Lester sisters. But in many respects they had stretched the truth, even mangled it. The 1870 census reveals that they were the daughters of a farmer named James Montgomery Simms of Greene County, Virginia. That they attended private schools and had lessons in elocution and dancing I find doubtful. Feminists have hailed them as liberated women of their time, which they certainly were, but recent scholarship suggests that they were never married. Stranded by a theater company in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1895, they opened a brothel there, then opened a second one for the 1898 exposition. Portraits commissioned by them in 1895 are suggestive, and publicity for the 1898 exposition includes a print showing Minna posing in a corset on an ornate brass bed and looking much less like a hard-nosed madam than a seductive courtesan offering her charms to whoever could afford them. Just how two respectably raised young Southern ladies transitioned to this profession remains a mystery that even their nephew, with whom I once corresponded, could not explain.

Ada in 1895. She achieved the wasp waist. Such was their story, prior to coming to New York as the Lester sisters. But in many respects they had stretched the truth, even mangled it. The 1870 census reveals that they were the daughters of a farmer named James Montgomery Simms of Greene County, Virginia. That they attended private schools and had lessons in elocution and dancing I find doubtful. Feminists have hailed them as liberated women of their time, which they certainly were, but recent scholarship suggests that they were never married. Stranded by a theater company in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1895, they opened a brothel there, then opened a second one for the 1898 exposition. Portraits commissioned by them in 1895 are suggestive, and publicity for the 1898 exposition includes a print showing Minna posing in a corset on an ornate brass bed and looking much less like a hard-nosed madam than a seductive courtesan offering her charms to whoever could afford them. Just how two respectably raised young Southern ladies transitioned to this profession remains a mystery that even their nephew, with whom I once corresponded, could not explain. Minna in 1895. Just a madam???

Minna in 1895. Just a madam???

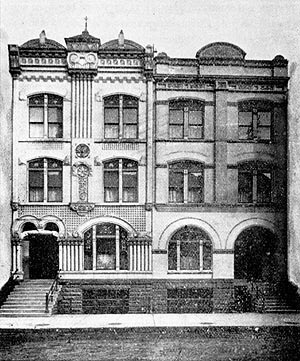

The Everleigh Club, 2131 and 2133 South

The Everleigh Club, 2131 and 2133 SouthDearborn Street. What is not in doubt is their having operated the luxurious Everleigh Club in Chicago and its immediate success. The club had twelve soundproof parlors (the Gold Room, Moorish Room, Red Room, etc.), an art gallery featuring nudes in gold frames, a dining room, a ballroom, a music room where a “professor” fingered the keys of a $15,000 gold-leaf piano, and even a well-furnished library where, to the sisters’ surprise, some of their patrons settled down comfortably with a book, probably glad to be away from their wife and kids. There were silk curtains, damask easy chairs, oriental rugs, mahogany tables, gold cuspidors, and perfumed fountains, and in the girls’ rooms upstairs, luxurious divans, gilt bathtubs, and warbling canaries.

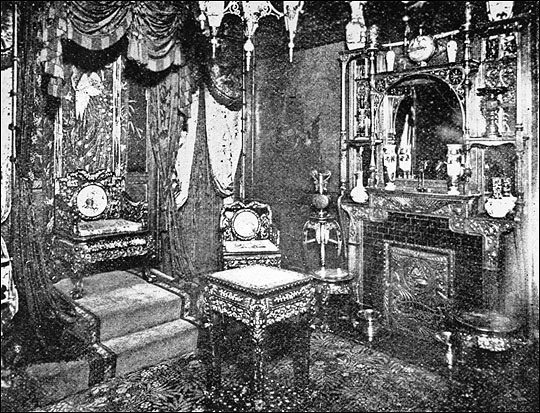

The Japanese Throne Room, as shown in the brochure.

The Japanese Throne Room, as shown in the brochure. The Blue Bedroom, as shown in the brochure.

The Blue Bedroom, as shown in the brochure.The Everleigh “butterflies” had to be attractive and healthy, free from drugs and drink, adept at small talk, and experienced but ladylike. The patrons had to dress and act like gentlemen; rowdy behavior was not tolerated. To get in, they needed a letter of recommendation from an existing client or an engraved card, and once in they had to spend freely, sometimes as much as $200 or even $1,000 a night; the club was no place for the budget-minded. The sisters were said to gross $15,000 a week, a generous amount of which went to corrupt aldermen and state legislators to guarantee their continued operation. Among their reputed guests were J. Edgar Lee Masters, Theodore Dreiser, Ring Lardner, and Prince Henry of Prussia, the Kaiser’s brother. In 1905, when Marshall Field II, heir to his father’s vast department store fortune, died of a gunshot wound, allegedly while cleaning a gun at home, rumor had it that he had been shot by a girl at the Everleigh Club, following which the sisters had the body smuggled out to his residence, or he himself, unaware of the seriousness of his wound, managed to get home by himself. This story some have dismissed, while others even today deem it credible. Yet another theory is that his death was a suicide.

What happens when the census taker comes to a whorehouse, especially the plushest one in the nation? Because I once did considerable research on the sisters, in preparation for a biography that I later gave up on, I can answer precisely, having combed the census records of 1900 until I found the entry for 2131 South Dearborn. When the enumerator called on June 6, 1900, Minna gave her age as 29 and Ada as 26, thus shaving 5 and 10 years off their ages respectively. As for the twelve “boarders” counted, not one confessed to being over 29. And their occupations? Artist, bookkeeper, cashier, seamstress, dressmaker, dry-goods clerk, milliner, saleslady, actress, cashier, and cook, plus one blank, probably the most honest answer of the bunch. Did the census taker know he was being lied to? Almost certainly , this being the city’s red-light district, with numerous “boarding houses” with only female boarders.

The Everleigh Club achieved national, even international, fame, but in time all good things come to an end. Anti-vice crusaders had long campaigned to close not just the Everleigh Club but the entire Chicago red-light district, but the Club’s reputation, and the sisters’ generous pay-offs to local politicians, had protected it. Then, in 1911, the sisters published a brochure entitled The Everleigh Club Illustrated, describing the club and illustrating it with photographs of its sumptuous interior. The brochure came to the attention of Mayor Carter H. Harrison, who took offense at it and ordered the police chief to close the Club once and for all. Having amassed a fortune, the sisters accepted his decision and threw a wild closing-night party to end things with a bang. They then sold the place, traveled a bit, and in 1913 moved to New York, taking some of the furnishings with them.

Many people come to New York in search of opportunity and excitement, but the Everleigh/Lester/Simms sisters came to it for a quiet retirement and theater. And so, having left their glory days behind in Chicago, they lived quietly on West 71st Street for years, attending theater, joining some women’s organizations, presiding over a poetry reading group, and visiting relatives in Virginia once a year. Perhaps the only one who knew of their past was Charles Washburn, a Chicago Tribune reporter whom they had known back in Chicago, and who would visit them once a year to share a bottle of champagne and reminisce. Drawing on information gleaned from these sessions, in 1934 he published Come into My Parlor: A Biography of the Aristocratic Everleigh Sisters of Chicago, a readable but undocumented biography that presents uncritically whatever they told him and is therefore not too reliable a source. When Minna died in 1948 at age 82, Ada sold the brownstone and went to live with her nephew, James W. Simms, in Charlottesville, Virginia, taking with her some of the furniture from the Everleigh Club – “beautiful furniture,” the nephew assured me later in a letter. She died there in 1960 at age 96. When we corresponded in 1981, Mr. Simms assured me that his aunts, whom he had visited in New York, were “two of the kindest, most caring people I have ever known.”

And how did I first hear of the “Scarlet Sisters” and their posh establishment? The way any son of the Midwest would have heard of them: discreetly, from his father, in the absence of any women. Long after their Club had been closed, its legend was passed on from father to son for decades.

Dragon Lady

The next exile to be mentioned here was a woman who cast an exotic spell not easily resisted. According to those who had dealings with her – diplomats, generals, statesmen – she was the brainiest, sexiest, most charming, and most ruthless woman they had ever encountered: Madame Chiang Kai-shek.

Puncsos The daughter of Charlie Soong, a wealthy Chinese businessman and former Methodist missionary, she had been raised a Methodist and educated in this country, graduating from Wesleyan College, and so spoke fluent English and had a good grasp of American society. As the wife of Chiang Kai-shek, head of the Chinese Nationalist Party or Kuomintang, with whom she had a long but stormy relationship, she was viewed and celebrated here as the First Lady of China, especially when Japan invaded China in 1937, and even more so after we went to war with Japan in 1941. Indeed, she and her husband, the Generalissimo, were embraced by us as the heroic leaders of China in the war against Japan, with little awareness of their opponents, the Chinese Communists. If the Generalissimo, standing stiffly in official portraits with his chest bemedaled, struck us as a Great Stone Face, distant and reserved, his wife exuded charm and used it skillfully in enlisting support for her husband. From first to last, svelte, well-tailored, and possessed of a seductive smile, she was into politics up to her lovely ears.

Puncsos The daughter of Charlie Soong, a wealthy Chinese businessman and former Methodist missionary, she had been raised a Methodist and educated in this country, graduating from Wesleyan College, and so spoke fluent English and had a good grasp of American society. As the wife of Chiang Kai-shek, head of the Chinese Nationalist Party or Kuomintang, with whom she had a long but stormy relationship, she was viewed and celebrated here as the First Lady of China, especially when Japan invaded China in 1937, and even more so after we went to war with Japan in 1941. Indeed, she and her husband, the Generalissimo, were embraced by us as the heroic leaders of China in the war against Japan, with little awareness of their opponents, the Chinese Communists. If the Generalissimo, standing stiffly in official portraits with his chest bemedaled, struck us as a Great Stone Face, distant and reserved, his wife exuded charm and used it skillfully in enlisting support for her husband. From first to last, svelte, well-tailored, and possessed of a seductive smile, she was into politics up to her lovely ears.Her fame in the U.S. peaked in 1943, when she came to this country to get more support for the Chinese Nationalist cause. She drew crowds of thousands, appeared for the third time on the cover of Time magazine, and became the first Chinese national and second woman to address a joint session of both houses of Congress. There was then great sympathy for China, our wartime ally long ravaged by the Japanese invaders, and she personified that ally, masking her husband’s authoritarian ways with her charm and her talk of democracy. The Methodist church in Evanston that I then attended was especially supportive of her, a fellow Methodist, there being many Methodist missionaries in China, and the daughter of our local Congressman told a group of us of meeting and talking with her personally. What I chiefly remember of her account was how, when Madame Chiang dropped something, she quickly picked it up herself, not wanting others to do it for her. Needless to say, the girl was absolutely charmed by Madame Chiang.

With the Generalissimo, Roosevelt, and Churchill in Cairo, 1943.

With the Generalissimo, Roosevelt, and Churchill in Cairo, 1943.The Generalissimo rarely left China, but this conference was important.

After the war things changed. The Nationalists, locked in a losing civil war with the Communists, were compromised by corruption; some of the money meant for the war against Japan had gone into the pockets of the Chiangs. When, in desperation, Madame Chiang came again to our shores to plead her husband’s cause, she was not as well received; her presence, in fact, was an embarrassment. When the Nationalists lost the mainland in 1949, she and her husband went with them to Taiwan, where they continued their struggle against the Communists. When the Cold War developed, they regained favor in this country as allies against the Soviets and Communist China, inaugurating a relationship that would have many ups and downs.

My own attitude toward the Nationalists and Madame Chiang changed when, in Evanston in 1950, I met a longtime friend of my mother’s, the YWCA’s official observer at the U.N. in New York, who viewed the Chiangs as despotic and corrupt. She told of a conversation with Madame Pandit, Nehru’s sister and India’s ambassador to the U.S., who recounted a meeting with Madame Chiang. Madame Chiang had stressed the importance of appearance; every morning, when she was dressing, Madame Chiang said she thought about what she would be doing that day, whom she would meet, and what impression she wanted to make. For her, clothing and appearance were an integral part of politics. Madame Pandit felt a bit overwhelmed by this unsolicited advice, and one suspects that Madame Chiang considered Madame Pandit just a bit dowdy. (How any woman in a sari could be dowdy I can’t imagine; personally, I find saris superbly elegant and attractive.)

As the Grande Dame of Taiwan, Madame Chiang made several trips to the U.S.in the 1950s to lobby the U.S. government against admitting Communist China to the U.N. As the Generalissimo’s health deteriorated, control of the Nationalist government passed to Chiang Ching-kuo, his son by a previous marriage. Madame Chiang and her husband had no children of their own, and she was not on good terms with his successor. When the Generalissimo died in 1975, Madame Chiang left Taiwan and established herself in New York in an Upper East Side apartment overlooking Gracie Square, and on an estate on Long Island. Though she lived here in semi-seclusion, when Chiang Ching-kuo died in 1988, she returned to Taiwan to support her old allies, but her influence had waned and she soon returned to New York. Here she was guarded by a team of black-suited bodyguards who cleared the lobby of her apartment building whenever she entered or left. She received few visitors, grew flowers, did calligraphy and drawings, read. Though hard of hearing as she aged, she was still quick-witted and read the Bible and the New York Times every day. She died in her apartment in 2003, age 105, having lived in three centuries, and is buried in New York State.

The Everleigh sisters lived quietly here, seemingly without regrets. How Madame Chiang felt while residing here, now wielding a pen and brush, when she had once manipulated statesmen and generals, I do not know. Surely she nursed some bitterness toward this country, once her staunch friend and ally, whom she blamed for the loss of China. She was a fascinating woman, a nest of contradictions, an enigma. We won’t see her like again. Regrettably, she never wrote her memoir.

A note on Chester Kallman: A viewer of this blog informs me that he briefly knew Kallman (post #119) in Athens in the 1960s or early 1970s. Invited for dinner, he and two friends arrived at Kallman’s apartment to find Kallman unprepared for guests … at least, dinner guests. After a delay Kallman emerged from the bedroom, disheveled and “quite messed up,” with two burly and surly young men. Embarrassed, Kallman explained that he had forgotten about the dinner date and asked his guests to come back the following evening. Kallman, it seems, had a liking for “rough stuff” from the junior ranks of the military junta then in power. The guests returned the following evening and a good time was had by all. But I hold to my personal conclusion that Kallman’s life was not, on the deepest level, a happy one.

This is New York

Kris from Seattle

Kris from SeattleComing soon: Two more posts on Exiles in New York: a pianist with five Steinways; an anarchist with a compact; a future emperor; a renegade priest with a talent for seduction and debt; a would-be proletarian who loathed the capitalist U.S.; and a keeper of the flame with orange hair.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on March 30, 2014 04:46

March 23, 2014

119. Exiles in New York, part 1

This post and the next are about exiles in New York City. Some of them chose to live here, others couldn’t wait until conditions – usually political – changed, permitting them to return to their homeland. Some learned English, others did not. Some loved New York, some tolerated it, and some were never comfortable here and got away as soon as they could. Admittedly, for most foreigners, New York requires an adjustment, being fiercely modern, fast-paced, noisy, and congested. On the other hand, it has been the preferred destination of many who were separated from the land of their birth.

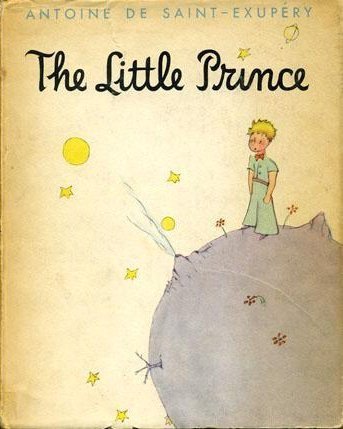

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Saint-Exupéry in Toulouse in 1933. A renowned author and pioneer commercial aviator, Saint-Exupéry came to New York on the last day of 1940, not wishing to live under the Nazi-allied Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain, which had come to power following the disastrous French military defeat and collapse. He spoke no English, but French-speaking American friends fed and feted him and found him and his wife Consuelo, who had followed him here, twin penthouse apartments on Central Park South. (A very posh address. It pays to have friends with connections.) When one of those friends saw a figure in his doodles, she suggested that he turn it into the protagonist of a children’s book. This would be a radical departure for Saint-Exupéry, the author of serious and sensitive works about aviation and travel, but the idea took hold and he started writing what would become his best-known work, Le Petit Prince, an illustrated children’s book to be read as well by adults.

Saint-Exupéry in Toulouse in 1933. A renowned author and pioneer commercial aviator, Saint-Exupéry came to New York on the last day of 1940, not wishing to live under the Nazi-allied Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain, which had come to power following the disastrous French military defeat and collapse. He spoke no English, but French-speaking American friends fed and feted him and found him and his wife Consuelo, who had followed him here, twin penthouse apartments on Central Park South. (A very posh address. It pays to have friends with connections.) When one of those friends saw a figure in his doodles, she suggested that he turn it into the protagonist of a children’s book. This would be a radical departure for Saint-Exupéry, the author of serious and sensitive works about aviation and travel, but the idea took hold and he started writing what would become his best-known work, Le Petit Prince, an illustrated children’s book to be read as well by adults. Another American friend, Silvia Hamilton, saw him regularly for a year and encouraged him in his writing until at last, in April 1943, the manuscript was finished. Rushing off to rejoin the Free French Air Force in North Africa, the author tossed a rumpled paper bag onto Hamilton’s entry table, containing the 140-page draft manuscript and drawings, the pages replete with corrections as well as coffee stains and cigarette burns. The finished work has been called fabulistic, abstract, ethereal; it is anything but realistic and makes no direct reference at all to the war in progress. In it a pilot stranded in a desert meets a yellow-scarfed young prince fallen to earth from a tiny asteroid. The prince tells of visiting various asteroids and describes the inhabitants of each: a king who thinks he rules the entire universe; a businessman counting the stars he thinks he owns; a drunk who drinks out of shame at his drinking; and so on. “Grown-ups are so strange,” says the prince.

Another American friend, Silvia Hamilton, saw him regularly for a year and encouraged him in his writing until at last, in April 1943, the manuscript was finished. Rushing off to rejoin the Free French Air Force in North Africa, the author tossed a rumpled paper bag onto Hamilton’s entry table, containing the 140-page draft manuscript and drawings, the pages replete with corrections as well as coffee stains and cigarette burns. The finished work has been called fabulistic, abstract, ethereal; it is anything but realistic and makes no direct reference at all to the war in progress. In it a pilot stranded in a desert meets a yellow-scarfed young prince fallen to earth from a tiny asteroid. The prince tells of visiting various asteroids and describes the inhabitants of each: a king who thinks he rules the entire universe; a businessman counting the stars he thinks he owns; a drunk who drinks out of shame at his drinking; and so on. “Grown-ups are so strange,” says the prince.Published in New York in French and English in 1943, Le Petit Prince was Saint-Exupéry’s last work. Though he was really too old, the Free French let him fly. While on a reconnaissance flight on July 31, 1944, his plane disappeared in the Mediterranean, presumably shot down by a German plane. The plane’s wreckage was found only sixty years later, though his silver identity bracelet was discovered snagged in a fishing net off Marseilles in 1998. Meanwhile Le Petit Prince, not published in France until 1946, has been translated into 250 languages and sells over 1.8 million copies a year. The author’s self-imposed exile in New York was fruitful in the extreme. I urge anyone who hasn’t read the work to do so; it is charming, provocative, unique. In fact, I recommend all his works, especially Terre des hommes (in English, Wind, Sand, and Stars, though I prefer the French title by far).

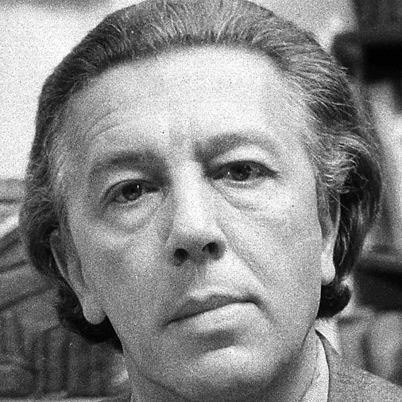

André Breton

The rise of fascism in Europe and the outbreak of World War II brought many European artists and intellectuals to these shores, many of them to New York. “Tête léonine,” said a fellow graduate student at Columbia, when I mentioned the poet André Breton as a possible dissertation subject, and it’s true that Breton usually wore his hair fairly long, giving him a somewhat lionlike appearance. The founder and arbiter of Surrealism, Breton was drafted into the army in 1939 and demobilized following the French defeat in 1940. No friend of Vichy, he left his beloved Paris for Marseilles, and from there by boat in 1941 managed to reach Martinique, where the Vichy authorities informed him that there was no need for Surrealism in Martinique, and interned him for a while. Released, he then managed to reach New York, where he found many of his Surrealist comrades, founded the Surrealist review VVV, and with Marcel Duchamp organized a Surrealist exhibition. He evidently supported himself by taking a broadcasting job, probably one related to the war effort, even though, like Saint-Exupéry, he never bothered to learn English or, so far as I know, any foreign language. An intellectual for whom ideas were vital entities to espouse and fight for, he exuded as always an undeniable charisma that drew others to him, and a quarrelsome streak that drove some away. No opinion of his was tepid or wishy-washy; a celebrant of heterosexual love and the surreal, he was determinedly anticlerical and fiercely homophobic.

Though he had long since broken with the Communist Party, where he never felt at home, in New York he had yet to renounce the tenets of dialectical materialism. Knowing this, the art critic Meyer Schapiro invited two intellectuals of his acquaintance, one a dedicated Marxist and the other a critic of Marxism, to a debate for Breton’s benefit. During the debate Breton listened intently but said not a word, as the critic of Marxism gained the upper hand. After that, Schapiro told me long ago, André Breton never again mentioned dialectical materialism. His distancing from Communism and its tenets was complete and final.

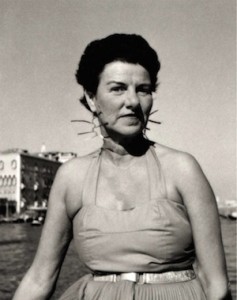

Wearing Alexander Calder earrings. Hosting Breton and other exiles in New York was the wealthy art patron Peggy Guggenheim, a niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, founder of the museum that bears his name. She had taken an active interest in Surrealism in the 1930s and in a very short time amassed a significant collection. Now, on West 57thStreet in wartime New York, she opened a museum/gallery called The Art of This Century Gallery, of which only the front room was a commercial gallery. She was married at the time to the Surrealist artist Max Ernst, who found the marriage a convenient way to gain entry to the U.S., but by her own admission she had a sexual appetite for men that matched her appetite for art. Photographs reveal a woman neither plain nor memorably beautiful, but she had money and influence and chutzpah (she was, after all, Jewish), and many an artist enhanced his career by obliging her in this regard. A 1942 photograph taken in her New York apartment shows herself posing with no less than fourteen renowned artists of the time – not all of them necessarily her lovers – including Breton, Ernst, Leonora Carrington, Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian. It is a curious photograph, with some of the subjects facing right, some left, and only a few looking squarely at the camera. Only Peggy Guggenheim could have assembled in one spot such a clutch of avant-garde talent, most of them in wartime exile.

Wearing Alexander Calder earrings. Hosting Breton and other exiles in New York was the wealthy art patron Peggy Guggenheim, a niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, founder of the museum that bears his name. She had taken an active interest in Surrealism in the 1930s and in a very short time amassed a significant collection. Now, on West 57thStreet in wartime New York, she opened a museum/gallery called The Art of This Century Gallery, of which only the front room was a commercial gallery. She was married at the time to the Surrealist artist Max Ernst, who found the marriage a convenient way to gain entry to the U.S., but by her own admission she had a sexual appetite for men that matched her appetite for art. Photographs reveal a woman neither plain nor memorably beautiful, but she had money and influence and chutzpah (she was, after all, Jewish), and many an artist enhanced his career by obliging her in this regard. A 1942 photograph taken in her New York apartment shows herself posing with no less than fourteen renowned artists of the time – not all of them necessarily her lovers – including Breton, Ernst, Leonora Carrington, Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian. It is a curious photograph, with some of the subjects facing right, some left, and only a few looking squarely at the camera. Only Peggy Guggenheim could have assembled in one spot such a clutch of avant-garde talent, most of them in wartime exile. Front row: Leonora Carrington, 2nd from left. Middle row: Max Ernst, far left; Breton in

Front row: Leonora Carrington, 2nd from left. Middle row: Max Ernst, far left; Breton inmiddle; Fernand Léger, 2nd from right. Back row: Peggy Guggenheim, 2nd from left;

Marcel Duchamp, 2nd from right; Piet Mondrian, far right. It was not Peggy Guggenheim who enlisted Breton’s affections in New York, but Elisa Claro (née Bindorff), whom he met in a French restaurant on 56thStreet in 1943 and married in (of all places!) Reno, Nevada, in 1945, she becoming his third and final wife. He traveled with her to Canada in 1944, and the following year they visited the Hopi reservation in Arizona, where they observed Hopi rituals and Breton added kachina dolls to his art collection. Accompanied by Elisa, in the spring of 1946 Breton returned to Paris to resume his Surrealist activities and rambunctious ways, as inclined as ever to provocation and controversy. His former Surrealist comrades Paul Eluard and Louis Aragon, now ardent Communists, dismissed him as irrelevant, since he had not participated, as they had, in the Resistance. Which didn’t prevent him from advancing as always the Surrealist cause and exploring what he would term Magical Art.

W. H. Auden

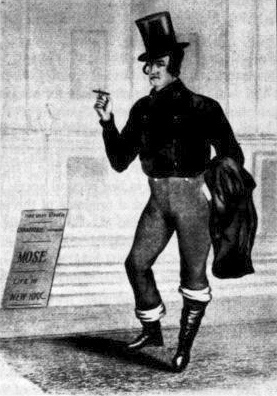

Auden in 1939. The English poet and man of letters W. H. Auden, already well known in England as a leftist writer and intellectual, came to New York in January 1939 with his friend the writer Christopher Isherwood, the two of them entering the U.S. with temporary visas but intending to stay. Auden and Isherwood, age 32 and 35 respectively, had known each other since boarding school, and in the 1920s had left strait-laced, homophobic England for the freedom of Weimar Berlin. There Auden had remained for nine months and Isherwood for years, the chief attraction being a seemingly inexhaustible supply of boys available and eager for sex. In the 1930s Auden worked in England as a schoolteacher, essayist, reviewer, and lecturer, but in 1937, when he did volunteer work for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, he became disillusioned with politics and disgusted with war. It was this experience, above all, that prompted him to quit England for America, where he hoped to resolve the doubts, both political and personal, now plaguing him.

Auden in 1939. The English poet and man of letters W. H. Auden, already well known in England as a leftist writer and intellectual, came to New York in January 1939 with his friend the writer Christopher Isherwood, the two of them entering the U.S. with temporary visas but intending to stay. Auden and Isherwood, age 32 and 35 respectively, had known each other since boarding school, and in the 1920s had left strait-laced, homophobic England for the freedom of Weimar Berlin. There Auden had remained for nine months and Isherwood for years, the chief attraction being a seemingly inexhaustible supply of boys available and eager for sex. In the 1930s Auden worked in England as a schoolteacher, essayist, reviewer, and lecturer, but in 1937, when he did volunteer work for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, he became disillusioned with politics and disgusted with war. It was this experience, above all, that prompted him to quit England for America, where he hoped to resolve the doubts, both political and personal, now plaguing him. Chester Kallman

Chester KallmanWhen the two newly arrived English writers gave a reading here, two college students from Brooklyn College sat in the front row and winked and smiled provocatively. One of them, Chester Kallman, showed up at their lodgings the next day to interview them for the college newspaper, causing Auden to remark sourly, “It’s the wrong blond!” But Kallman, with an ample supply of Brooklyn chutzpah, persisted with the interview, and by the end of it Auden’s interest had kindled. In fact, he was smitten; they soon became lovers.

The New York literary scene was to Auden’s liking and he remained here, but in April 1939 Isherwood, sensing that the East Coast would be Auden’s turf, went to California, where he would settle down and cultivate the West Coast as his own. When war broke out in September, Auden informed the British Embassy in Washington that he would return to Britain, if needed, but was told that for his age group only qualified personnel were wanted. In spite of this, there would develop considerable resentment in Britain that Auden and Isherwood had absented themselves when Britain, following the fall of France, stood alone against Germany and endured the horrors of the Blitz. Auden, on the other hand, viewed the wartime sloganeering, speechifying, and committee-joining fervor of British intellectuals as irrelevant to the war effort, and as potentially damaging as fascism at its worst.

In 1940-41 Auden lived in a ramshackle brownstone at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights in an experiment in communal living launched by his friend George Davis, a brilliant fiction editor recently fired from his job at Harper’s Bazaar because of his total lack of self-discipline. Experiments in communal living were nothing new in America, but nineteenth-century endeavors had proven impractical, since the free spirits involved were better at talk and philosophizing than at managing money, doing the dishes, and taking out the trash. Nothing daunted, Davis assembled in the brownstone on Middagh Street a number of his authors and acquaintances, including Auden, Carson McCullers, Benjamin Britten and his partner Peter Pears, Jane and Paul Bowles, Gypsy Rose Lee, and others – such a concentration of creative talent, seasoned by the presence of an acclaimed stripper recently turned author, that it spices the mind.

Carson McCullers Auden was not noted for neatness – wherever he lived, he left papers and cigarette ashes strewn about – but in this crowd he was by contrast the perfect bourgeois, imposing regular meals and regular working hours for all. He wrote out cooking and cleaning schedules, lectured his housemates when they used too much toilet paper, and announced at dinnertime, “There will be no political discussion.” He and Carson McCullers, who had just achieved literary fame with the publication of her first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, developed a warm teacher-student friendship beneficial to both – a remarkable achievement, given Cullers’s neurotic hang-ups and hard drinking. At Davis’s invitation Gypsy Rose Lee joined the party so he could help her work on a novel, The G-String Murders, which in time became a best-selling mystery. She alone of the residents had both money and common sense. Her maid came with her but was unable to cope with the accumulated dirty clothes and dishes, empty bottles, and cigarette ashes and stubs.

Carson McCullers Auden was not noted for neatness – wherever he lived, he left papers and cigarette ashes strewn about – but in this crowd he was by contrast the perfect bourgeois, imposing regular meals and regular working hours for all. He wrote out cooking and cleaning schedules, lectured his housemates when they used too much toilet paper, and announced at dinnertime, “There will be no political discussion.” He and Carson McCullers, who had just achieved literary fame with the publication of her first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, developed a warm teacher-student friendship beneficial to both – a remarkable achievement, given Cullers’s neurotic hang-ups and hard drinking. At Davis’s invitation Gypsy Rose Lee joined the party so he could help her work on a novel, The G-String Murders, which in time became a best-selling mystery. She alone of the residents had both money and common sense. Her maid came with her but was unable to cope with the accumulated dirty clothes and dishes, empty bottles, and cigarette ashes and stubs. Visiting this curious artists colony were Anais Nin, who christened the brownstone the February House because several of the occupants had birthdays in February, and Thomas Mann’s daughter Erika and son Klaus. (Auden had married Erika to give her a British passport, but by mutual consent the marriage was never consummated and they lived apart.) The novelist Richard Wright and others also dropped in.

Amazingly, the residents of the February House all managed to get some significant work done, but their love life was often less than satisfactory. George Davis happily cruised the Brooklyn piers, but Carson McCullers pined futilely for the Swiss journalist and world traveler Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach, a friend of the Manns, while Auden yearned stubbornly for Chester Kallman, who after two years, being young and adventurous, informed Auden that from now on he would range freely in search of sex. Deeply wounded, Auden, who wanted a stable relationship, managed to maintain his friendship, albeit sexless, with Chester. Auden’s friends never could grasp why Auden clung to a younger partner whom they considered in every way his inferior, but they apparently failed to grasp that desire is not wise or prudent or practical; it simply is. Auden and Chester Kallman each offered the other something that he needed, something beyond sex; the relationship ended only with Auden’s death. How Auden squared his sex life with the Anglican faith he had returned to in 1940 I do not know. He seems to have been troubled by his sexuality, as Kallman was not.

Inevitably, communal living in the February House began to fray on the nerves of the participants. Fed up with her housemates’ drinking and slovenliness, Gypsy bowed out first, soon followed by McCullers, whose boozing and late hours had impaired her fragile health. Irked by Paul Bowles’s noisy sex games with his wife and loud partying, Auden and Britten expelled the offender, but Britten and Pears then also left the house and America, returning to wartime Britain. Soon afterward Auden too moved out, convinced of the need for a balance between bohemian chaos and bourgeois convention that the February House obviously could not provide. George Davis stayed stubbornly on until the house was demolished in 1945; in time he would marry Kurt Weill’s widow, Lotte Lenya, and work hard promoting Weill’s work. The story of 7 Middagh Street, Brooklyn Heights, brief but stellar, has justifiably been called a true mingling of the sublime and the ridiculous; it is well told in Sherill Tippins’s February House (Houghton Mifflin, 2005).

When Auden was called up for the draft in 1942, the U.S. Army rejected him because of his avowed homosexuality. For several years he taught at Swarthmore College and in 1945, unknown to Auden at the time, he was considered for the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on the basis of his volume For the Time Being, but lost out to Karl Schapiro because of his alleged Communism (he had never joined he Party) and his aloofness from the war. Then, in March 1945, he applied to join U.S. Army as part of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey in Germany, and became a major as a “bombing research analyst in the Morale Division,” interviewing civilians in the devastated cities of Germany. Significantly, neither his wartime disgust with war nor his homosexuality seems to have been a problem, and the prospect of a steady and substantial salary was surely an enticement. The thought of Auden in uniform is, to put it mildly, arresting. (The Strategic Bombing Survey, by the way, studied the effects of bombing on both Germany and Japan and concluded that 10% of the bombs hit their target. One wonders, then, where the other 90% ended up.)

The later Auden. Auden became a U.S. citizen in 1946 and continued to live in New York, making a living as a writer, teacher, lecturer, and librettist. Reading his poetry, he practiced a low-keyed delivery, despising the sonorous and inflated tones that often plague poets when they read. In 1948 his long poem The Age of Anxiety won the Pulitzer Prize. From 1953 on he shared houses and apartments with Kallman, though later he would summer in Europe. Time took its toll on both of them. Auden’s aging face grew fissured from his steady smoking, and svelte, young Chester became a middle-aged man who drank far more than was good for him. When Stravinsky asked Auden to do the libretto for The Rake’s Progress, Auden, hoping to reclaim Chester through the steadiness of work, enlisted his support and sold him to the composer as a collaborator. Occasionally Kallman would show some poetry of his own to a friend, who was invariably struck by its intensity. One suspects that Kallman secretly resented being in the shadow of an acclaimed man of letters, but he published three volumes of his own poetry and in collaboration with Auden became known as a librettist.

The later Auden. Auden became a U.S. citizen in 1946 and continued to live in New York, making a living as a writer, teacher, lecturer, and librettist. Reading his poetry, he practiced a low-keyed delivery, despising the sonorous and inflated tones that often plague poets when they read. In 1948 his long poem The Age of Anxiety won the Pulitzer Prize. From 1953 on he shared houses and apartments with Kallman, though later he would summer in Europe. Time took its toll on both of them. Auden’s aging face grew fissured from his steady smoking, and svelte, young Chester became a middle-aged man who drank far more than was good for him. When Stravinsky asked Auden to do the libretto for The Rake’s Progress, Auden, hoping to reclaim Chester through the steadiness of work, enlisted his support and sold him to the composer as a collaborator. Occasionally Kallman would show some poetry of his own to a friend, who was invariably struck by its intensity. One suspects that Kallman secretly resented being in the shadow of an acclaimed man of letters, but he published three volumes of his own poetry and in collaboration with Auden became known as a librettist. Auden’s literary reputation has had its ups and downs. While a poet friend of mine praised him to the skies, I found him a bit too ironic, detached, intellectual, preferring the Celtic word jungle of the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, impenetrable as that jungle can be. By the time of his death in 1973, Auden was recognized as a literary elder statesman. He died in Vienna of heart failure and is buried in Kirchstettin, a town in Austria where he had owned a farmhouse.

Just as Auden once went to Berlin for boys, so Kallman went to Athens for the same, moving his winter home there in 1963. He is said to have been generous to his young male lovers. He died suddenly in Athens in 1975, age 54, and is buried there in the Jewish Cemetery, far apart from Auden. Some sources say that, mourning Auden, he died of a broken heart, but I find this fanciful. On a deep level his life was not a happy one, but perhaps I'm being judgmental.

A note on WBAI: The loyal staff, whose devotion is commendable, profess optimism about saving the station, but the desperate appeals for donations go on and on and on. I never thought the award-winning news program would vanish, but it did. The substitute news program likewise vanished, replaced by fund-raising specials, then came back, and now has vanished again. Inconsistency in programming is sure to drive listeners away -- listeners like me, a longtime supporter of the station. I hear Gary Null’s one-hour program at noon on weekdays, though he warns that he may be eliminated, because of his criticism of the current management. I hear Richard Wolff’s weekly economics program at noon on Saturday, though I’ve got his message fully by now (capitalism is bad, socialism is the answer). And I hear Thom Hartmann’s 5 p.m. program weekdays, though his self-promotion annoys me, as does his constant replaying of segments, often up to three or four times within two days. But that’s it. I find it very easy to turn from WBAI to WNYC, and that is the crux of the problem. (Apologies to those unfamiliar with WBAI and its travails, but I feel a need to chronicle its endless downward spiral; unique, it is in danger of disappearing forever.)

This is New York

Bob Jagendorf

Bob JagendorfComing soon: Exiles in New York, part 2. The Scarlet Sisters, a Dragon Lady, an anarchist with a compact, diverse others.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on March 23, 2014 05:17

March 16, 2014

118. How New Yorkers Have Fun

New York has always been fun city, a place where people came to have a good time, to live it up, maybe to get just a bit wild. And the locals have always liked to have fun, too, and in the Big Apple the possibilities were – and are -- endless. But what exactly is “fun”? The dictionary says “what provides amusement or enjoyment,” and in distinguishing it from words like “game” and “play” says that fun “implies laughter or gaiety, but may imply merely a lack of serious or ulterior purpose.” Okay, I’ll go along with that, though I may stretch the definition just a bit.

lldar Sagdejev

lldar Sagdejev David Shankbone

David Shankbone

Bureau of Land Management

Bureau of Land Management

Having fun today

I asked several of my friends what they do, or what they have done in the past, to have fun. The answers varied quite a bit. For instance:

· Cook a dinner for friends you’ve invited over.· Museums and concerts.· Hiking.· A good book.· A congenial bar with a good piano player.· A dinner out.· A disco with loud music and dancing.

No, not a single orgy; sorry to disappoint. My friends don’t go for orgies, or if they do, they won’t admit to it. But don’t worry, we’ll get around to some wild stuff later. If some of these are on the quiet side, without laughter or overt gaiety, I still include them as fun, quiet fun, but bars and discos offer noisy fun, too. One friend, by the way, reported that he didn’t have fun anymore, though he’s never struck me as glum. Here now are some notes on the examples of fun listed above.

As regards bars, one gay friend mentioned The Monster, a gay bar in the West Village on Grove Street at Sheridan Square with a bar/piano lounge at ground level. He described it as having three personalities. The pianist often plays show tunes from shows from the storied past, to the delight of the older gays present (personality #1). But he also plays tunes from recent shows, to the delight of the younger gay set (personality #2). And #3? For that you go downstairs to the dance floor, where Hispanic males dance up a storm. The bar has been going since 1970 and is definitely a fun scene. One of the online reviews by a man from Brooklyn tells how his girlfriend wanted to take him out to a fun gay bar for his birthday and chose The Monster on a recent Sunday night. “We happened to be thrown into a sea of fun bartenders and staff that were hosting an underwear party that night. What a blast we had.” And if his girlfriend was one of only three women there, everyone seemed to love her. His conclusion: “Will definitely be back!” Which sounds like a real New York scene.

Though it’s in my neck of the woods, I’ve never been to The Monster, so I’ll mention instead a gay disco that Bob and I went to in the late 1960s and 1970s, when discos were all the rage. It was a mafia-run joint in the West Village, with the inevitable thug at the door to keep the non-gay element out. Inside you were obliged to have a drink first at the bar, before proceeding to the dance floor in back. And what a dance floor it was! Male and female couples (rarely mixed) bouncing and jiggling to ear-splitting piped-in music while strobe lights flashed splashes of color that made you think you were on an LSD trip, while a male go-go dancer in a bikini exposed his pulsating charms. It was wild, it was crazy, it was fun. At first some of the lesbians fooled me; they really looked like men. But Bob and I decided that two things gave them away: the voice (if they spoke), and the line of the jaw, always slightly more delicate, less rough-hewn than a man’s. Otherwise, you’d never have known the difference. But all that was long ago.

I also mentioned a good dinner out. Quiet fun, but fun nevertheless, and very New York. New Yorkers like to dine out and have the choice of cheap, moderate, or very expensive and exclusive restaurants, and every ethnic variety conceivable. Over the years Bob and I have patronized Italian, French, Spanish, German, Irish, Chinese, and Thai restaurants, with special emphasis on Italian and Chinese. For a really good meal Bob and I used to go to Gargiulo’s, an old family-run Italian restaurant on West 15th Street in Coney Island, but a few blocks from the boardwalk. Founded by the Gargiulo family in 1907, when the great amusement parks were flourishing, in 1965 it was bought by the Russo family, who have run it for several generations. Under the Russos the restaurant has greatly expanded, adding extra dining rooms to accommodate weddings and celebrations, and a huge parking lot across the street offering valet parking to patrons coming from all over the city. (Bob and I were probably the only ones who came and went by subway.) The expansion was no doubt all to the good, though it did eliminate a brothel discreetly situated next door, passing which, as we approached the portals of culinary Elysium, somehow added spice to the adventure. Gargiulo’s is famous for classic Neapolitan fare, but to sample it you have to observe their dress code: no shorts and, God knows, no bare feet. This may be Coney Island, but it’s a very special Coney Island, catering to middle-class families of taste.

The main dining room, circa 1970. Dining often in the high-ceilinged main dining room, Bob and I acquired a favorite waiter, Giancarlo, who looked after us with care. My preferred dishes: as an appetizer, mozzarella in carrozza (mozzarella cheese on toast), then fettuccine alfredo, and for dessert, cannoli (fingerlike shells of fried pastry dough with a sweet, creamy filling). I couldn’t begin to describe these dishes; I can only say each was delicious, exquisite, unique. Though meat dishes and seafood were available, we learned to settle for pasta, which Gargiulo’s does superbly. As veteran New Yorkers, such a meal was the evening’s entertainment; there was no thought of doing anything else, except the long subway ride home the length of Brooklyn, most of it above ground, looking at the dark borough’s lights, and savoring in memory the dishes we had just enjoyed. When we saw other guests – a few – rush through their meal and dash off to some other engagement, we were amazed; what could possibly top a dinner at Gargiulo’s?

The main dining room, circa 1970. Dining often in the high-ceilinged main dining room, Bob and I acquired a favorite waiter, Giancarlo, who looked after us with care. My preferred dishes: as an appetizer, mozzarella in carrozza (mozzarella cheese on toast), then fettuccine alfredo, and for dessert, cannoli (fingerlike shells of fried pastry dough with a sweet, creamy filling). I couldn’t begin to describe these dishes; I can only say each was delicious, exquisite, unique. Though meat dishes and seafood were available, we learned to settle for pasta, which Gargiulo’s does superbly. As veteran New Yorkers, such a meal was the evening’s entertainment; there was no thought of doing anything else, except the long subway ride home the length of Brooklyn, most of it above ground, looking at the dark borough’s lights, and savoring in memory the dishes we had just enjoyed. When we saw other guests – a few – rush through their meal and dash off to some other engagement, we were amazed; what could possibly top a dinner at Gargiulo’s?When you have a favorite restaurant, you experience more than just food. It becomes, in fact, a ritual. Bob and I would go to the New York Aquarium at Coney Island on the afternoon of Christmas Eve, when there were very few visitors, to renew our acquaintance with penguins, walruses, and sharks. Then we would walk along the boardwalk and, on a clear day, see the sun set over the ocean, en route to Gargiulo’s, where we would arrive shortly after 5 p.m., among the first of the diners to appear. Always we asked for Giancarlo, who would greet us warmly and guide us to our reserved table. Then, as the dining room filled up, we had the fun – yes, fun – of watching middle-class Brooklyn on a very special family night. Three, even four, generations of an Italian American family would arrive, some of the elderly in wheel chairs, the grown unmarried kids dining of necessity with the family, the young women, sometimes blond, in stylish black dresses or pants suits, and the little kids invariably more elegant than their parents. Only a restricted menu was available, so as to lighten the work of the staff, since they would be going to midnight Mass. But if we asked Giancarlo if canoli, not on the menu, were possible, he would reply with a sly smile, “For you, yes,” and canoli would appear.

Giancarlo wasn’t the only staff member we bonded with. One of the Russos, Anthony, whom Bob remembers as long ago behind the coat check counter, now helps run the restaurant and welcomes patrons table by table with a hearty greeting. And once we saw Lula, one of the staff in her late forties, come out of the kitchen to greet some longtime patrons and friends, and she seemed so open and friendly that we flashed a smile in her direction. That was all she needed to come over and greet us, total strangers, and exchange a few warm words. After that, with management’s approval and blessing, I would always go into the huge kitchen, hunt her up among the sinks and cutting boards and pans, and say hello and thank her – and through her all the staff – for the superb dinner we were having. She always responded with the warmest smile and thanks.

The Gargiulo's staff. Lula on the far right, with

The Gargiulo's staff. Lula on the far right, withAnthony standing next to her.