Clifford Browder's Blog, page 45

August 17, 2014

140. Norman Mailer: Wife-Stabber, Brawler, and Man of Many Wives

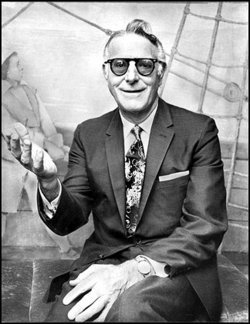

Norman Mailer in 1988.

Norman Mailer in 1988.MDCarchives Who was the reporter who was doing such brilliant reporting of the 1967 Pentagon march and the 1968 conventions? Photos show a man with a massive frame and an impressive head with tousled hair and memorable features – an overgrown teddy bear, you might say, or a lionlike head, albeit with wrinkles and bags under his eyes: the head of an aging lion. One thinks of Norman Mailer as a man in his middle years with a somewhat worn look, never young, and one who surely took himself very seriously. There are pictures of him as a boxer, and in those he is taking himself very seriously indeed. No spoofing in these photos, never a wink of complicity at the rest of us. He admired boxers, liked their courage, discipline, and aggressive self-assertion, and when drunk – and Mailer was often drunk – he was quite ready himself to take a swing at someone, even a friend. But if he had a boxer’s aggressiveness and courage (or at least a drunken bravado), he totally lacked the discipline.

His antics were notorious. In November 1960, while drunk at a party in New York, he stabbed his second wife, Adele, with a penknife, just missing her heart, and then stabbed her again in the back. As she told it later (his women had a way of publishing tell-all memoirs), when someone tried to help her as she lay on the floor bleeding, Mailer blurted out, “Get away from her. Let the bitch die.” Adele’s wounds required emergency surgery, but she did not press charges. After seventeen days in Bellevue Hospital under psychiatric observation, Mailer was released, only to be indicted by a grand jury for felonious assault; later he pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of third-degree assault and received a suspended sentence. It has been suggested that this event kept him from later receiving a Nobel Prize. Adele divorced him in 1962.

Gore Vidal in 1948. But the favorite target of Mailer’s drunken ire was author Gore Vidal, whose critical review of one of Mailer’s books incensed him to the point that, just before they were to appear on Dick Cavett’s TV show in December 1971, Mailer head-butted Vidal backstage, then during the show traded insults with him and the host. But this was just the prelude. At a New York dinner party in 1977 attended by the cultural elite, Mailer evidently threw a gin and tonic in Vidal’s face and bounced the glass off his head. The distraught hostess exclaimed, “God, this is awful! Someone do something!” But another guest told her, “Shut up! This fight is making your party.” Vidal’s reaction to these assaults: “Once again, words fail Norman Mailer.” An elegant WASP known for his wit and urbanity, Vidal was a natural target for the rough-hewn Mailer, the son of immigrants, whose physical attacks failed to dent Vidal’s patrician aplomb.

Gore Vidal in 1948. But the favorite target of Mailer’s drunken ire was author Gore Vidal, whose critical review of one of Mailer’s books incensed him to the point that, just before they were to appear on Dick Cavett’s TV show in December 1971, Mailer head-butted Vidal backstage, then during the show traded insults with him and the host. But this was just the prelude. At a New York dinner party in 1977 attended by the cultural elite, Mailer evidently threw a gin and tonic in Vidal’s face and bounced the glass off his head. The distraught hostess exclaimed, “God, this is awful! Someone do something!” But another guest told her, “Shut up! This fight is making your party.” Vidal’s reaction to these assaults: “Once again, words fail Norman Mailer.” An elegant WASP known for his wit and urbanity, Vidal was a natural target for the rough-hewn Mailer, the son of immigrants, whose physical attacks failed to dent Vidal’s patrician aplomb.Mailer had been born to a family of Jewish immigrants in New Jersey and grew up in Brooklyn. After graduating from Harvard he served in the Army during World War II, then came back to write The Naked and the Dead. His next two novels garnered negative reviews, and after a frustrating period as a screenwriter in Hollywood he returned to New York in 1951 and lived at various addresses on the Lower East Side. Several acquaintances got him to invest in and help launch the iconoclastic Village Voice, an alternative weekly that first appeared in October 1955. Steeped in liquor and drugs, he began a short-lived column that was meant to be outrageous, and reaped volumes of hostile fan mail as a token of his success.

In 1969 he launched another venture that was not just outrageous but quixotic, entering the Democratic mayoral primary and calling for a “hip coalition of the right and the left” to rescue the crime-ridden and debt-burdened city. Columnist Jimmy Breslin ran with him for City Council President, and feminist Gloria Steinem ran for Comptroller. “No More Bullshit” and “Vote the Rascals In” were their slogans, as they proposed to make New York City the 51st state. Their other proposals: reduce pollution by banning all private cars from Manhattan; expand rent control; return power to the neighborhoods; legalize heroin; and offer draft exemptions to those enlisting for short-term service in the police. Though Mailer and his colleagues wanted to be taken seriously, the newspapers found the idea of a Mailer-Breslin ticket preposterous, and Mailer seemingly confirmed their opinion when, during a fund-raiser, he railed drunkenly at his own supporters, calling them “a bunch of spoiled pigs.” It was no surprise to observers – and perhaps a great relief -- when embattled Mayor John Lindsay easily triumphed in the primary and then went on to get himself reelected.

Mailer’s fourth novel, An American Dream, was published in 1965. A friend once told me that, after reading it, he gave up on Mailer as a novelist. When I read it years later, I understood why. In a drunken rage the book’s supremely successful protagonist strangles his estranged wife, then has sex with her maid, who has no knowledge of the murder; after that, to make the wife’s death look like suicide, he throws her body out a window. Later that same night, after being questioned by police detectives, he initiates an affair with a night-club singer who, he learns later, once had an affair with the wife’s father. All this, and much more, including two more murders, within 24 hours. Even if the writing is impressive – the account of his questioning by detectives is quite convincing -- the overburdened plot doesn’t just strain credibility, it shreds it. From then on I viewed Mailer as a brilliant journalist but a failed novelist.

The wife-stabbing incident, and its fictional reprise in the strangling in An American Dream, hardly endeared Mailer to the feminists; there was in fact an ongoing war between them. He was the very image of the brawling, boozing, womanizing super macho male, and as such an inevitable target for feminists. This was fine by him, for he relished the fight. Women’s writing, he opined, was “fey, old-hat, Quaintsy Goysy, tiny, too dykily psychotic, crippled, creepish, fashionable, frigid, outer-Baroque” – and so on, to which he added, “a good novelist can do without everything but the remnant of his balls.” Was he dead serious or just being deliberately provocative? When he suggested that women “should be kept in cages,” his last wife Norris insisted that there was a twinkle in his eye. If there is a trait in him that I esteem, it is his refusal to be politically correct no matter what the cost.

In 1977 Mailer received a letter from convicted murderer Jack Abbott, offering to give an accurate account of prison life. Mailer agreed, and in 1981 In the Belly of the Beast, comprising Abbott’s letters to Mailer, was published with an introduction by Mailer and became a bestseller. In Abbott Mailer probably saw an example of the hipster outlaw eulogized in his essay “The White Negro.” Mailer and others had been supporting Abbott’s appeals for parole, and in June 1981 he was released, despite the misgivings of prison officials who were worried about his mental state and considered him dangerous. Coming to New York City, Abbott was hailed by the literary community. Six weeks after his release, Abbott got into an argument with a young actor working as a waiter in a restaurant and stabbed him to death. I remember the shock of this news, and the widespread condemnation of Mailer that followed. Abbott fled the city but was later arrested in Louisiana, tried for murder and convicted of manslaughter, and given a sentence of 15 years to life. Mailer, who attended the trial, later admitted that his advocacy of Abbott was “another episode in my life in which I can find nothing to cheer about or nothing to take pride in.” When the parole board rejected another of his appeals, Abbott committed suicide in a New York State prison in 2002.

I shan’t linger here over Mailer’s other works, some of them unworthy of him, being written in haste to make money (as he accumulated ex-wives, he also accumulated alimony claims), and some of them significant. The year 1980 was eventful for him: he finally got a divorce from his fourth wife; married his fifth wife, a jazz singer, thus legitimizing their daughter, then flew to Haiti one day later and got a quickie divorce; and three days after his return married his sixth and last wife, Norris Church, who in spite of his many affairs stayed with him to the end. All of which was, for Mailer, no small accomplishment, for how many men could boast of having been married more or less legally to three different women within the space of one week?

As for Norris, who was from Arkansas, in her memoir she claimed to have had a brief earlier fling with Governor Bill Clinton. When an acquaintance later said to her, “I guess he slept with every woman in Arkansas except you, Norris,” she replied, “Sorry, I’m afraid he got us all.” A 1983 photograph of her with Mailer shows a mature but attractive woman in a frilly pink hat and pink scarf, but I suspect that she was a lot tougher than frilly pink might suggest. To live with Mailer she would have to be.

Mailer and Norris lived together in a brownstone at 142 Columbia Heights in Brooklyn Heights, just across the East River from Manhattan. Their fourth-floor co-op apartment overlooked the Brooklyn Heights Promenade with a sweeping view of the harbor and the Statue of Liberty. Mailer had bought the building in 1960 and moved into the top-floor apartment in 1962. His extensive renovation raised the roof and remodeled the apartment as a light-filled multilevel nautical curiosity; to access the “crow’s nest” where he wrote, you had to climb ladders, traverse catwalks high above the living room, and walk a narrow gangplank. All this because he had a fear of heights and was determined to conquer it. The apartment witnessed many

celebrity-studded parties, as well as meetings to plan his 1969 mayoral campaign, and his and Norris Church’s wedding. In 1980 a costly divorce from his fifth wife forced him to rent out the lower floors of the building. But Mailer, who fancied himself a sailor, wanted to be closer to the sea. So in 1986 he and Norris bought a spacious beachfront house in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and spent part of the year there.

What do I finally make of Norman Mailer, a much published author, provocative, outrageous, perennially drunk, who married six wives in turn (thus matching Henry VIII) and by them had eight children and adopted a ninth, his last wife’s son by another marriage? Though a gifted writer, he was a child who never grew up. He totally lacked the very thing that my grade school teachers preached to callow minds endlessly: self-control. He yielded to impulses, with dire results for both himself and others. Brilliant at times, but a child.

Mailer’s health failed in his later years, when he suffered from arthritis and deafness and had to walk with two canes. He underwent lung surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and a month later, on November 10, 2007, at age 84, died of acute renal failure. That he lasted that long, given his heavy intake of drugs and alcohol, is remarkable. He is buried in Provincetown.

The noble sport goes back to the Minoans.

The noble sport goes back to the Minoans.Marsyas Personal aside #1: Me and Boxing. Since Mailer idolized boxing and boxers, and I present myself as his opposite, it may be surprising that I once also found myself boxing. It was the second semester of my first year in college, and all male students were required to take a semester of either boxing or wrestling, and I, with great misgivings, chose boxing. (My father had always lamented the failure of American youth to engage in bodily contact sports, even as he overprotected me.) The head coach presided, but he immediately introduced a bruiser named Kelly, tall and massive with a steel-like chin, who had boxed professionally and would therefore be our instructor. At the mere sight of him I was nervous, and so were plenty of others.

With a resonant voice Kelly told us that knowing we could hold our own in a boxing match would build self-confidence, but added with emphasis, “It takes a gentleman to walk away from a fight.” Daily lessons followed. “Bloody Monday!” was Kelly’s hearty greeting at the start of the week, though in truth not much blood was spilled. Unaggressive by nature, I wasn’t out to land a forceful punch. Instead, I saw boxing as a kind of dance, since footwork was involved, and a game where you tried to touch your opponent’s face or shoulder. Once a friend walked right into one of my gentle punches and, dazed, had to leave class at once. I hadn’t punched hard, but all my friends kidded me about knocking out a partner. Then one day Kelly picked me to show how he could get past my defenses to touch my shoulder, which meant he could have punched me in the face; finally I started to dodge. Again, my friends kidded me afterward for “taking on” Kelly. On another occasion one of the guys did get hit hard in the midriff and was moaning in pain; Kelly had him lean his head against his massive shoulder, while he assured the rest of us that in a short while the kid would be all right – not too convincing at first, with the kid moaning and groaning, but in time he was.

In spite of this memorable incident, the dreaded class turned out to be bearable. On the last day the head coach had all of us box for him, so he could award the grade. My partner confessed that he wasn’t keen on boxing, so I told him I wasn’t either, but added, “Let’s give them a good show and get out of here.” We did. After several sluggish matches by others, we came on like fury, trading gentle punches vigorously, and the whole class gathered round and cheered us heartily on. “I want to box with you!” several friends told me afterward, but I just smiled: it was the last day of the class, no chance. So ended my career in boxing – not the total fiasco I had anticipated. As for Kelly the bruiser, we saw him play a Christian convert in Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion and play the role very well, demonstrating that he wasn’t just a bruiser; he was an actor, too. So “Bloody Monday!” wasn’t the whole story; there was more to him -- a lot more – than that.

Personal aside #2: What famous writers would I want to avoid, and which would I want to hang out with? I know I wouldn’t have wanted to know Norman Mailer. Which prompted a piquant thought: who else would I want to seek out or avoid? Let’s start with those I’d want to avoid (which has nothing to do with their value as writers):

· All the drunks. (There goes half of American literature.)· All the egomaniacs. (There goes the other half.)· Milton. (Too sure of himself, little sense of humor.)· Dante. (He might put me in hell.)· Sartre. (Too fiercely intellectual.)· André Breton, head of the Surrealists. (Too severely judgmental. I should know, having done my thesis on him.)· Alexander Pope. (He might skewer me in a satire. A nasty little man, keen and vicious, though in print amusing.)· Rimbaud. (Another nasty one; look how he savaged Verlaine, who had his reasons for shooting the kid.)· Jonathan Swift. (Too fiercely satiric.)· Allen Ginsberg. (He’d want me to take my clothes off. And I wouldn’t want to see him naked either. NOT INVITED

John Milton. For small talk he'd probably talk

John Milton. For small talk he'd probably talktheology.

Alexander Pope. A deft and savage satirist.

Alexander Pope. A deft and savage satirist.No thanks, why take a chance?

Jean-Paul Sartre. Brilliant, but too intellectual.

Jean-Paul Sartre. Brilliant, but too intellectual.

Allen Ginsberg. I remember him

Allen Ginsberg. I remember him with a beard and too much hair,

but no matter. At least he

has his clothes on here.

Ludwig Urning

That’s a lot of avoidances. No women, interestingly enough. So how about those writers I’d like to know, maybe find myself sitting next to at a dinner party?

· The Roman poet Horace. (At the top of the list. Gifted but modest, all for simple living, likable, a sense of humor, a supremely good conversationalist.)· Chaucer. (Great sense of humor – sometimes a bit ribald, but that’s okay. Loved people, very observant.)· Benjamin Franklin. (Charming in society, could relate to almost anyone. Witty, informed, good sense of humor.)· The early Whitman. (The fervent lover of the Calamus poems, not the later “good gray poet” who seemingly repudiated his gay self for the sake of his patriarchal image.)· Victor Hugo. (As healthy and upbeat as they come, a perennial optimist.)· Voltaire. (Witty, irreverent, humane, sociable.)· Rabelais. (If I’m in a mood for the boisterous and bawdy.)· Shakespeare. (Seems to have been modest and gentle, but let’s face it, we hardly know anything about him.)· Byron. (Could be charming, though at times a poseur.)· Colette. (Sensitive, observant, deeply human.)· Dickens. (Sociable, knowledgeable, congenial.)· Jane Austen. (Sociable, to judge from the novels, and full of good sense, though I don’t know much about her personally.)· Madame de Sévigné. (Warm, sociable, and witty, to judge by the famous letters.)

IINVITED

Ben Franklin. Bright and witty, a charmer.

Ben Franklin. Bright and witty, a charmer.

Voltaire. Ah, that sly smile, hinting at

Voltaire. Ah, that sly smile, hinting ata wicked wit.

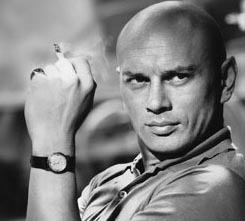

Lord Byron. To add spice to the party;

Lord Byron. To add spice to the party;bisexual, with appeal to both sexes.

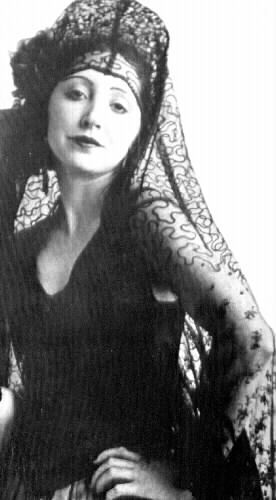

Colette. Worldly, observant, shrewd.

Colette. Worldly, observant, shrewd. She'd write a canny account

of the gathering. Lots of great names fall between the two camps – Goethe, Chekhov, Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Baudelaire, Proust -- not to be avoided but not among my top choices for dinner table companions. I’m looking for those who would be friendly and open, easygoing, unpretentious, with no need to shock, and as willing to listen as to talk. In other words, well balanced and not broody moody. Among great writers I’m lucky to find any at all.

Coming soon: Hell House, the Latest Form of Christian Terrorism. “Christian terrorism?” you may ask. Yes, it’s an old tradition in this religion of love and compassion; I’ll trace it back via the Middle Ages to the Gospels. And a Hell House here in secular New York? Yes, once, back in 2006 in Brooklyn. After that: Is bigger better? MOMA and the Frick: museums and their lust to expand. And after that: What do Elmo, Mickey Mouse, squeegee men, fake nuns, and Revolutionary War veterans have in common?

© 2014 Clifford browder

Published on August 17, 2014 04:58

August 10, 2014

139. Norman Mailer and the Chaos in Chicago

Mailer in 1948

Mailer in 1948I never knew the man, never even glimpsed him, know him only from his works, only some of which I have read. Nor was he someone I would have cared to know. Why then this post? Because he’s huge and inescapable, and because sometimes we feel a morbid attraction to our opposite. And he was certainly my opposite. Consider:

· He was macho, I am not, nor have I ever felt the need to be so.· He was straight, I am gay.· He loved attention, craved it, wallowed in it, regardless of whether it was favorable or not, whereas I don’t need it, would prefer to fade away like a flounder into sand.· He liked to box and made a big thing of it, whereas I don’t. (See the personal aside below.)· He was drug- and booze-ridden, out of control; I am not.· He was capable of physical violence, whereas I, to the best of my knowledge, am not.· He was a successful writer, I am not. (Published, yes, but hardly successful in the usual sense of the word.)· He was a womanizer and went through six wives and any number of mistresses, whereas I am by nature monogamous, have been in one gay relationship for 46 years.

And so on and so on. But by defining this renowned egomaniac in contrast with myself, I risk making this post as much about myself as about Mailer. And this from someone who claims not to be an egomaniac himself! Well, we’ll see.

I first heard of Mailer – as did most people – when his war novel The Naked and the Dead was published to great acclaim in 1948, though I didn’t read it until years later. It’s a good novel, though I’d hardly call it his best work, as some critics do; but it launched him, at age 25, into fame and notoriety, which he reveled in and would enjoy for the rest of his life.

It was in the 1960s, and as a journalist, that Mailer really came to my attention, gripped me, impressed me. I read his essay “The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster,” first published in 1957, though I read it a little later, when I was flirting with Beatnik culture and in a mood to break away – for a while – from the safe middle-class life I was living and experiment with peyote. But I was hardly a hipster, wasn’t into jazz, which Mailer associated with apocalyptic orgasm (he was always big on orgasm) and with living for instant gratification. (For instant gratification and mindless escape I’ve always preferred dancing – wild, crazy dancing, and I don’t mean the waltz.) Especially controversial in the essay was Mailer’s citing the murder of a white candy-store owner by two 18-year-old blacks as an example of “daring the unknown.”

The march on the Pentagon Then came the Vietnam War, which Mailer vigorously opposed, and his award-winning book The Armies of the Night (1968), recounting his participation in the march on the Pentagon by tens of thousands of war protesters on October 21, 1967. He is of course the center of the account, but hardly glamorized. He sees the stars of the demonstration as the novelist, the poet, and the critic: himself, Robert Lowell, and Dwight Macdonald (though there were plenty of others, too). What does Lowell really think of him as a novelist? he wonders, then reflects that Lowell may be wondering what he, Mailer, thinks of Lowell as a poet. Does Mailer perhaps prefer Allen Ginsberg? The goals of the march are gradually whittled down by what the authorities will allow, but the march does take place, with Mailer, Lowell, and Macdonald conspicuously in the lead.

The march on the Pentagon Then came the Vietnam War, which Mailer vigorously opposed, and his award-winning book The Armies of the Night (1968), recounting his participation in the march on the Pentagon by tens of thousands of war protesters on October 21, 1967. He is of course the center of the account, but hardly glamorized. He sees the stars of the demonstration as the novelist, the poet, and the critic: himself, Robert Lowell, and Dwight Macdonald (though there were plenty of others, too). What does Lowell really think of him as a novelist? he wonders, then reflects that Lowell may be wondering what he, Mailer, thinks of Lowell as a poet. Does Mailer perhaps prefer Allen Ginsberg? The goals of the march are gradually whittled down by what the authorities will allow, but the march does take place, with Mailer, Lowell, and Macdonald conspicuously in the lead. Mailer knows he risks arrest, and thinks longingly of the party that awaits him afterward, if he is free to attend, a party that promises to be tasty (perhaps not quite the word he used, but close). When they get to the Pentagon, they are met by ranks of National Guardsmen. Mailer is confronted by a young Guardsman who is obviously nervous but tells him to go back. Mailer presses on and gets arrested. Reporters ask him about the arrest, and he replies that it was done quite correctly; there was violence elsewhere, but he did not experience or witness it. He spends a night in jail with hundreds of other protesters. Some of them approach him, but he spurns them as mindless; finally he is released.

What I esteem in Mailer’s account of the march is his honesty: the compromises, the self-doubt, the need to create a public image of the protest and the calculations that went into it. He is totally convincing.

Again, I find him at his best in Miami and the Siege of Chicago (also 1968), his account for Harper’s Magazine of the tranquil Republican convention and the turbulent Democratic convention of August 1968. Irving Howe once observed that there were two Norman Mailers: a “reflective private Norman” and a “noisy public Norman.” True enough, and the noisy one often obscures the reflective one, but in his journalism the reflective one prevails. At Miami, where he always refers to himself as “the reporter,” he is admitted by mistake to a Republican Grand Gala from which the press has been excluded, and senses in the wealthy and powerful Republicans present an enduring faith in America as “the world’s ultimate reserve of rectitude, final garden of the Lord.” Following that he describes with intelligence and understanding the “New Nixon,” a Nixon chastened by recent political setbacks that could easily have ended his career. His take on Nixon at his only press conference, prior to his winning the nomination on the first ballot: still uneasy with the press, guarded and unspontaneous and devoid of charisma, but showing the kind of gentleness that ex-drunkards acquire after years in Alcoholics Anonymous, and fielding questions with a newfound dignity and modesty. And this from an observer who admittedly up till now had always been hostile to Nixon.

Nixon and supporters, 1968

Nixon and supporters, 1968Memorable as well is the reporter’s observations on Nixon’s reception for delegates, this again prior to the nominations. Here Nixon and his wife greet patiently the long line of followers eager for a few seconds with their revered candidate, who shakes the hand of each and gives them a few precious seconds of greeting. And who are these followers back in that distant pre-Tea Party time? Not the biggies present at the Gala, but the little Republicans: small-town druggists and bank tellers and high school principals, widows with a tidy income, retired doctors, minor executives, farmers who own their own farm, salesmen, librarians, and editors of the local newspaper – older Wasps from the Midwest and Far West who lead quiet, orderly lives and adore their candidate in a way to deep for applause. These are Nixon’s people and he knows it and is at ease with them, as he never quite is with the press. This is sensitive reporting from a reporter for whom these people have to be aliens, since he is the Brooklyn-raised son of a Jewish immigrant father and now hobnobs with (and sometimes head-butts and punches) literary lions and the elite of the urban intelligentsia.

(A personal aside: They are my people too, or were, since I grew up in a middle-class suburb of Chicago that was quietly but staunchly Republican, my father a corporation lawyer, and our neighbors Chicago businessmen, local merchants, university professors, the night editor of a Chicago newspaper, and a dentist -- good, solid, orderly folk for whom the name of Roosevelt was anathema and who surely voted for Nixon, as for Eisenhower and Dewey before him.)

A further surprising conclusion of the reporter: Too long a damned minority, perhaps it is time for the Wasp to come to power again. The Left, he opines, lacks a vision sufficiently complex to give life to America; it is too full of kicks and pot and orgy, the howls of electronics and LSD. And again, this from a man steeped in booze and drugs, ever ready for an altercation or a fight. As for Nixon, in his acceptance speech he pledged “to bring an honorable end to the war in Vietnam,” proving once again that, for all his faults, politically he was no fool.

What a contrast were these tranquil scenes in Miami with the riotous events of the Democratic convention in Chicago later that same month of August! There, in the wake of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy earlier in the year, all the furies of the war protest movement converged, joined by anarchists and Yippies and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and other groups, for a dramatic confrontation with Mayor Daley’s police and National Guardsmen. Bearded, balding, and spectacled, Allen Ginsberg showed up prepared to calm the Yippies’ Festival of Life with his meditative chant of OM. With him came Beat author and heroin addict William Boroughs, and French author and ex-thief Jean Genet, both of whom Esquire magazine had commissioned to cover the convention. Whatever their stated motives, in counterculture circles Chicago promised to be a rich stew of protest that no one wanted to miss out on.

To understand the two conventions in August 1968, one needs to understand the events preceding them in that eventful year. Here is a brief chronology:

· January 16. The first manifesto of the newly organized Youth International Party announces that the Yippies will be in Chicago in August for a Festival of Life, coinciding with the Democratic convention, which they label a Festival of Death. The threats of LBJ (President Johnson) and Mayor Daley will not stop them, they insist.· January 31. The North Vietnamese launch the surprise Tet Offensive throughout South Vietnam, catching the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces off guard; even the U.S. embassy in Saigon is briefly invaded. The attack is repulsed, but, contrary to statements by the Pentagon and the Johnson administration, it proves that North Vietnam is far from defeated in the war.· March 12. Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, an opponent of the war, wins 42% of the New Hampshire primary vote to President Johnson’s 49%, surprising everyone by the strength of his support. He is now the hope of the antiwar movement.· March 16. Senator Robert Kennedy of New York announces his candidacy, splitting the antiwar movement. McCarthy’s supporters denounce Kennedy as an opportunist and Johnny-come-lately for having entered the contest only after McCarthy showed the strength of that movement (an opinion that I at the time shared).· March 31. Aware of his growing unpopularity, Lyndon Johnson stuns the nation by announcing he will not seek reelection. The race to succeed him is now wide open.· April 4. Martin Luther King is assassinated in Memphis. Black ghettoes in many cities, including Mayor Richard Daley’s Chicago, erupt in riots. Daley, who rules Chicago with an iron hand, tells the police to shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand. Reported in the press, this order causes a sensation and becomes highly controversial.· April 23. To protest university administration policies, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and militant black students occupy buildings on the Columbia University campus and seven days later are violently evicted by police. These events are emblematic of campus unrest throughout the nation, as students rebel against authority, and young men threatened by the draft burn their draft cards and vow, “Hell no, we won’t go!”· April 27. An antiwar march in Chicago organized by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam ends with police beating many of the marchers. · April 27. Vice-President Hubert Humphrey, a longtime liberal, announces his candidacy. A supporter of Johnson’s policies, he gets the backing of the Democratic establishment.· June 5. Robert Kennedy is assassinated In Los Angeles. His supporters are in disarray, disliking both McCarthy and Humphrey.· August 8. The Republican convention in Miami Beach nominates Richard Nixon as their presidential candidate.· August 10. Urged on by many Kennedy supporters, after some hesitation Senator George McGovern of South Dakota announces his candidacy only two weeks before the Democratic convention. Long an opponent of the war, he is backed by many Kennedy followers.· August 26-29. The Democratic national convention in Mayor Daley’s Chicago, with antiwar demonstrators out in force. Daley has vowed that “No thousands will come to our city and take over our streets, our city, our convention.” The stage is set for a violent confrontation.

Robert Kennedy in 1963. He knew

Robert Kennedy in 1963. He knewhow to reach people. Mailer liked Chicago, quickly realized that Chicagoans resembled the people of Brooklyn he grew up among: simple, strong, warm-spirited, sly, rough, tricky, and good-natured. (With most of this I agree, having grown up in a Chicago suburb.) But he was there for other reasons. Like many, he mourned the loss of Robert Kennedy and for an antiwar candidate found himself stuck with Eugene McCarthy, whom he remembered from a cocktail party in Cambridge soon after Kennedy’s death. At the party McCarthy had looked weary beyond belief, his skin a used-up yellow, as he tried to answer the inevitable idiotic questions of others. McCarthy was not a mixer, Mailer concluded, and a man too private for the mixing required in politics, seeming less like a presidential candidate than the dean of the finest English department in the land. (I had reached a similar conclusion from the fact that he was also a poet. A poet in the White House? – no way! In some countries, perhaps, but in this one, never.)

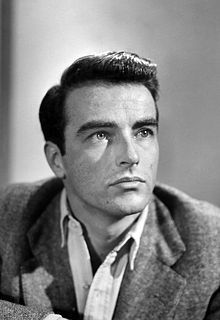

Eugene McCarthy. Too much of a thinker

Eugene McCarthy. Too much of a thinkerto be President?

When McCarthy arrived now at the airport in Chicago and was welcomed by five thousand enthusiastic supporters, he seemed full of energy and happy. But when he addressed the crowd for a few minutes, he spoke mildly with a certain detachment; they wanted fire, he gave them ice. When Mailer encountered McCarthy with some friends a few days later in a restaurant, the senator, no longer a serious candidate since Humphrey had been chosen, seemed relaxed and in good humor. Yet when Mailer looked across the table at the senator, he saw a toughness in his face. A complex man, probably too complex to be President.

Hubert Humphrey, with the famous smile

Hubert Humphrey, with the famous smile that helped win him the name of the

Happy Warrior. For Hubert Humphrey, Mailer has less to say. In sharp contrast to McCarthy, he arrived with almost no one to greet him at the airport, just a handful of his staff. He would then go against political common sense and forfeit any chance of winning by remaining Johnson’s boy, afraid to face the collective wrath of the President and the military-industrial establishment by coming out against the war.

But while a divided and turbulent Democratic convention was proceeding inside the International Amphitheatre, on the city’s south side near the stockyards, outside in the streets an even more turbulent drama was unfolding. Mayor Daley had decreed that no one would be allowed in the parks after 11p.m., so thousands of protesters decided to remain. And since Daley had decreed that the protesters would not be allowed to march, they vowed to march whenever and wherever they wished. Daley had massed thousands of police and National Guardsmen, but there were thousands of demonstrators, making violent clashes almost inevitable. And clashes there were, night after night. When not fighting the police, the young demonstrators shouted “Dump the Hump!” (meaning Humphrey), sang “We Shall Overcome,” and called out “Join us!” to bystanders, some of whom actually did.

Mayor Daley (left) with President Johnson.

Mayor Daley (left) with President Johnson.Witnessing some of these events and getting reports about others, Mailer provides vivid descriptions of many. He himself, being Mailer, manages to get arrested twice by the National Guard, but is released when brought before the officer in charge. Here are some of the highlights of his reporting, which he supplements with firsthand Village Voice accounts of events that he missed:

· Allen Ginsberg in Lincoln Park chanting OM and tinkling his finger cymbals peacefully, with William Boroughs and Jean Genet close by, when huge tear-gas canisters come crashing into the center of the gathering, sending people running and screaming in all directions, while a line of police advance, swatting at stragglers and crumpled figures on the ground, until angry fugitives swarm into the streets, blocking traffic, fighting plainclothesmen, setting fire to trash cans, and demolishing police patrol cars with a rain of missiles.

· The police tear-gassing protesters in Grant Park, with the wind blowing the gas across Michigan Boulevard into the Conrad Hilton, a huge looming structure housing the Humphrey and McCarthy headquarters, many delegates, and much of the press, who suffer smarting eyes and burning throats, and from their windows see the drama unfolding below.

· A delegate, addressing the kids in the park, calls up to the delegates and campaign workers in the Hilton (his voice presumably amplified), “If you are with us, blink your lights,” and lights begin to blink in the Hilton, ten, then twenty, then fifty, till whole banks of lights at the McCarthy headquarters on the 15thand 23rd floors flash on and off, and the crowd of bruised and bloodied kids, in spite of the sour vomit odor of the Mace that has been used on them, in spite of everything, cheer.

· While Mailer watches safely from his 19thfloor window in the Hilton (he admittedly has no appetite for tear gas or Mace), the police chase demonstrators, beat them, bloody them, only to find them reforming their ranks to taunt and challenge them again, till the police, in what becomes an out-and-out police riot, charge a crowd of bystanders watching quietly from behind barriers in front of the Hilton, crushing the bystanders against a plate glass window that shatters, tumbling the people into the hotel bar, where the police follow to beat the occupants, including some who had been quietly drinking at the bar.

Police attacking demonstrators outside the convention.· Demonstrators, reporters, and McCarthy workers, along with doctors beaten by the police when they tried to help wounded demonstrators, stagger into the Hilton lobby, blood streaming from their wounds, amid the stench of tear gas, and of stink bombs hurled outside by the Yippies.

Police attacking demonstrators outside the convention.· Demonstrators, reporters, and McCarthy workers, along with doctors beaten by the police when they tried to help wounded demonstrators, stagger into the Hilton lobby, blood streaming from their wounds, amid the stench of tear gas, and of stink bombs hurled outside by the Yippies. · In the convention hall Senator Ribicoff of Connecticut nominates George McGovern, saying that with him as President “we wouldn’t have those Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago,” at which point Mayor Daley leaps to his feet, shakes his fist at the podium, and shouts insults that most of those present can’t hear, but that TV lip-readers throughout the country interpret, rightly or wrongly, as “Fuck you, you Jew son of a bitch!” The incident provokes roars from the floor and a buzz from the gallery. (Ribicoff was indeed Jewish.)

George McGovern

George McGovernWhen the balloting began, there were no surprises, for Humphrey was nominated on the very first round; masterminding events from his ranch in Texas, where he was safe from the rowdy welcome his appearance in Chicago might have provoked, LBJ had managed things well. But thanks to the TV cameras, the world had witnessed what went on inside and outside the hall, and the bruised and bandaged protesters knew it, shouting “The whole world is watching,” and considered the whole riotous event a victory. There were excesses on both sides, but far more on the side of Daley and his goons. Mailer reflects on the thin line that divides the police from criminals, observing that the mass of policemen are a criminal force restrained by their guilt, and by a sprinkling of career men working earnestly for a balance between justice and authority.

Watching the televised events in Chicago, the nation decided, I suggest, that it needed someone safe and sane in the White House, someone speaking with a voice of moderation: Richard Nixon. And so it came to pass.

Note: This post has focused on Mailer the journalist in Chicago and leaves out much else that happened there; anyone unfamiliar with the story should read a comprehensive account, including the subsequent trial of the Chicago Seven, leaders of the antiwar demonstrations who were charged with conspiracy and inciting to riot. The next post will tell how Mailer stabbed his second wife, assaulted Gore Vidal twice, ran for mayor of New York, helped get parole for a convicted murderer still capable of murder, and managed to be legally married to three different women sequentially in the space of one week. Plus two Mailer-inspired personal asides: one on me and my brief career in boxing (Mailer fancied himself a boxer; I did not), and one naming which famous deceased writers I would want to avoid (Mailer being one of them) and which ones I would like to hang out with.

Coming soon: More Mailer, as indicated above. Then: Hell House, the Latest Form of Christian Terrorism.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on August 10, 2014 04:48

August 3, 2014

138. Gentrification and the West Village: Good or Bad?

Gentrification is a term that raises hackles. Usually it means trading one thing for another: gutsy for genteel, old neighborhoods with human-scale buildings for luxury high-rises; low rents for high rents; working class and bohemia for solid white-collar middle class; mom-and-pop stores for boutiques; charm for soulless modernity. But things aren’t always that simple. How about Greenwich Village, especially the West Village, where I have lived since the early 1960s? What has happened to it?

I have just finished John Strausbaugh’s epic 624-page chronicle The Village: 400 Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues: A History of Greenwich Village, which I highly recommend to anyone interested in the subject. It ends with an Epilogue where survivors of another time lament the recent gentrification of the Village and the loss of a wild, radical, anything-goes spirit, funky and creative, that pervaded it back in its low-rent days. Yes, that spirit is gone, along with the low rents that once attracted young writers, artists, and enterprising theater people who made, or tried to make, wild things happen. But even they represented a kind of gentrification, for the Village, as Strausbaugh demonstrates, has undergone a series of gentrifications.

When I came to the Village in the 1960s, another young writer I got to know, very WASP, told me how his Italian landlady was learning that she could rent safely to newly arrived non-Italians, who could be counted on to pay their rent. So the arrival of people like him and me – the very ones who diluted the working-class Italian population that Tammany boss Carmine DeSapio had counted on at election time (see post #135) – constituted a wave of gentrification, even though the streets and buildings of the Village didn’t change. And I recall a vignette in the neighborhood weekly The Villager, which was delivered free to everyone’s doorstep, briefly describing two girls, barefoot, eating ice cream cones, and observing, “Isn’t that what the Village is all about? Two barefoot girls eating ice cream cones.” Which said nothing about the influx of gay people, Off Off Broadway, the jazz scene, and the prevalence of drugs and booze. The Villager, of course, was where you went for news of the PTA and what the Girl Scouts were up to, and not much else. So back then, obviously, there were many Villages, perhaps as many as there were Villagers.

In the early 1900s political radicals and free lovers flocked to the low-rent Village. The Irish and Italian working-class residents, who considered the Village theirs, looked askance at men with long hair and even more at women with short hair who drank and smoked openly in the company of these outlandish males. (Generation after generation, the Village has always lured a fresh version of the New Woman, to the fascination of the press and public.) Wild politics and wild art followed. But by the early 1920s the radicals were lamenting the passing of the Golden Years, as bars and restaurants and boutiques opened to accommodate the weekend tourists who flocked to the Village via the recently extended IRT subway line, eager to see the Village’s weird bohemian denizens and be shocked and fascinated by its New Women, who necked freely at parties and wore bobbed hair. Locals complained that this wasn’t the Village they grew up in, and some artists moved out, unable to afford the rising rents. (Sound familiar?)

Prohibition brought speakeasies, and the Depression brought real and imitation proletarians and Communists, among the latter none other than a Harvard dropout named Pete Seeger, whose radicalism took the form of music. And the WPA kept many a Village artist and writer from foundering in poverty. No, this wasn’t the Village of the Roaring Twenties, least of all after the Mafia moved in. But it was still different: 14th Street was the dividing line between uptown and downtown. Uptown meant money, power, elegance, and class; downtown meant hip, artsy, scruffy, and wild. For all its changes, the Village was still the Village.

Which brings us to my time in New York. In the 1950s I was far uptown at Columbia University, but weekends meant subway trips to the Village and its gay bars, trips that left studies and a pretense of heterosexuality behind, and generated a kind of freedom, partial and temporary, but freedom even so. And friends of mine began moving down to the Village, which planted in my mind the notion of doing the same. And in 1959, I did, giving up a spacious two-room apartment near the campus for a crummy one-room apartment on West 14th Street with a teetering table, one dingy window with a view of nothing, and a ravaged ceiling with a bare light bulb and peeling paint.

But oh how that ceiling astonished me, becoming a cratered lunar landscape, then pocked skin whose blemishes were entrancingly beautiful, when I stared at it high on peyote! And how that bare light bulb overhead obsessed me, becoming the life-giving sun to whom I of all mortals was chosen to offer my seed in a consummation on which the fertility of the whole world depended. (A consummation that I had to fake, since being high gives visions but leaves your dingus limp; I did my best, not wanting to let the universe down. For the whole crazy story, see post #62, Abnormal and Paranormal Adventures.)

So there I was, indulging in my one and only experiment with drugs, and in less exalted moments sticking my middle-class nose into the Gaslight Café on MacDougal Street, to hear second-rate Beatniks spout their sometimes amusing but never brilliant stabs at poetry. All this because I had read Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and been transported by it. (I still am.) Yes indeed, a weekend tourist (I had a weekday job) having a go at playing bohemian, unaware that in so doing I was participating in an old Village tradition that went back decades at least. And this in the Village of barefoot girls gobbling ice cream cones!

In 1961 I returned from a year and a half in San Francisco and got an apartment on Jane Street, then in 1968 quit my teaching job and met my partner, Bob, also a Village resident. And in June 1970 we moved into the rent-stabilized apartment on West 11th Street where we still reside (once in a rent-stabilized apartment, one moves out only feet first). Which brings us to the threshold of the Golden Years (the Village has had many Golden Years) that the survivors in Strausbaugh’s Epilogue remember with nostalgia.

Yes, something of that time has been lost today, but let’s see what else gentrification has wrought besides high rents. The heart of the Village hasn’t changed outwardly, being an officially recognized Historical District, though the commercial fringes are fair game for developers, with resulting ugly glass boxes looming here and there, though distant enough to leave the human-scale old buildings and quiet side streets intact. So what has changed and what do I regret?

How about the Women’s House of Detention, that depressing twelve-story monolith of a prison looming smack against my local library where Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Avenue converge? Do I miss it, half Bastille and half Bedlam, and the stories it inspired of cockroach-ridden cells, wormy food, and abuse of inmates by other inmates and staff? Do I miss the volleys of obscenity issuing from it in the evening when inmates called down greetings to their friends, lovers, and pimps on the sidewalk, who shrieked answers laced with obscenities? No, not much. Least of all when the monstrous thing was torn down and replaced with a charming little park where I have often strolled. Score 1 for gentrification.

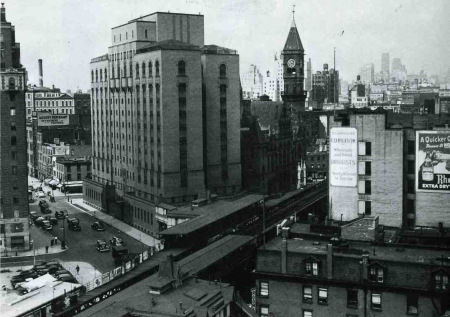

The Women's House of Detention in the 1930s, with the Sixth

The Women's House of Detention in the 1930s, with the SixthAvenue El in the foreground.

The Jefferson Market Garden Or do I miss the abandoned and crumbling Hudson River waterfront, where gay men went at night for quick anonymous sex, often with multiple partners, in smelly parked trucks, or in rat-infested, rubble-strewn sheds on the piers, in a darkness lit only by the glow of an occasional cigarette? Today the waterfront has been cleaned up, most of the moldering piers removed, a few of them turned into parks with trees and lawn, and the whole riverside converted into a long ribbon of greenery with a bike path and a walk for pedestrians, dog runs and tennis courts and other facilities. Yes, it’s middle-class and well scrubbed and respectable, but so what? People go there to cycle and walk, to sunbathe, to play ball with their kids, to read, even at times to dance. It’s safe, it’s healthy, it’s fun. Score 2 for gentrification.

The Jefferson Market Garden Or do I miss the abandoned and crumbling Hudson River waterfront, where gay men went at night for quick anonymous sex, often with multiple partners, in smelly parked trucks, or in rat-infested, rubble-strewn sheds on the piers, in a darkness lit only by the glow of an occasional cigarette? Today the waterfront has been cleaned up, most of the moldering piers removed, a few of them turned into parks with trees and lawn, and the whole riverside converted into a long ribbon of greenery with a bike path and a walk for pedestrians, dog runs and tennis courts and other facilities. Yes, it’s middle-class and well scrubbed and respectable, but so what? People go there to cycle and walk, to sunbathe, to play ball with their kids, to read, even at times to dance. It’s safe, it’s healthy, it’s fun. Score 2 for gentrification. The Hudson River Park, looking south from Christopher Street to Pier 40. I often walk here.

The Hudson River Park, looking south from Christopher Street to Pier 40. I often walk here.By the 1970s the Village had become a sexual playground, and gay men, far from hiding their sexuality, flaunted it. I recall the meatpacking district in the northwest corner of the Village near the Hudson when it was a sparsely populated commercial area with shabby streets given over to wholesale meatpacking; passing by, I often saw butchers and meat cutters in blood-stained aprons, graffiti-ridden walls, and rows of carcasses dangling from hooks outside the meatpacking establishments. But by the 1970s the neighborhood had become wild with gay sex clubs and leather bars with enticing names like the Mineshaft, the Anvil, the Ramrod, the Cock Pit, and (I’m not inventing this) the Toilet. At the Anvil at 14th Street and Tenth Avenue drag queens performed on a runway, and naked go-go boys pranced up and down the bars and did amazing gymnastics, and patrons resorted to the dim basement for sex. The Mineshaft at Washington and Little West 12th Street was even wilder: in a dim back room men had sex in cubicles, others submitted to anal fisting, and still others knelt in a bathtub for the fun of being urinated on. And to enjoy these delights, one had to adhere to a strict dress code: no colognes or perfumes; no suits or ties; no designer sweaters; no disco drag or dresses. Preferred dress included leather and Western gear, Levis, jocks, action ready wear, and uniforms. As for action, according to witnesses the nearby Toilet was even worse.

Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District, 2007. Still shabby in places.

Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District, 2007. Still shabby in places.Juliana Ng

This scene passed me by, for I wasn’t into leather or anonymous sex; being in a relationship, I didn’t need the joys of the Mineshaft or the Toilet. The most that Bob and I did was dance at the Goldbug, a Mafia-run disco with the traditional thug at the door, a male go-go dancer, and ear-splitting music – wild for us, but tame by the standards of the day. And when I read a letter in the press by a Village resident telling how, when she and her family walked the Village streets, “liberated” gay men eyed her twelve-year-old son brazenly, I shared her indignation and yearned for the good old days of clandestine gay life, when heterosexuals weren’t intentionally molested. If this was gay liberation, I wanted no part of it.

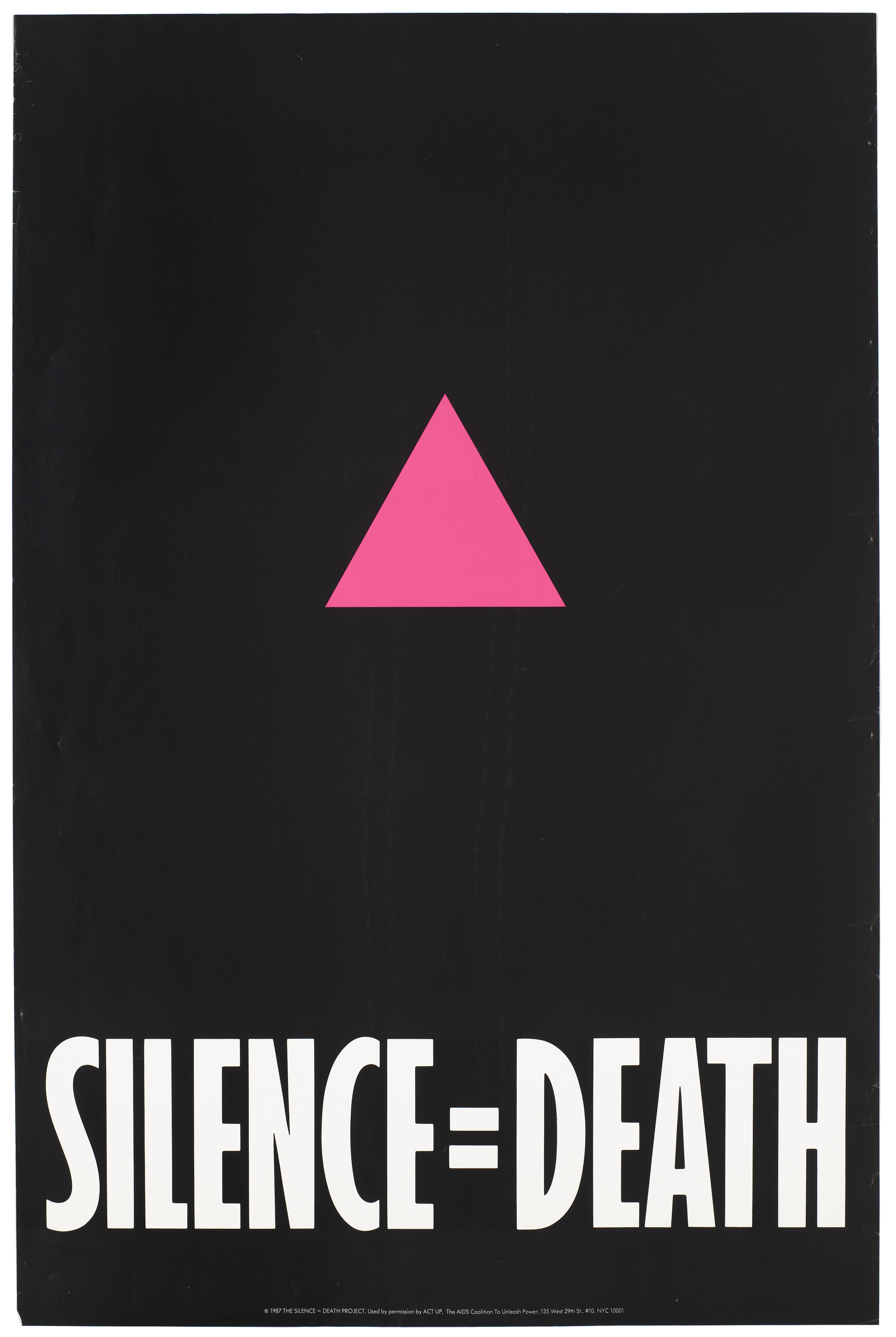

A new kind of spook house, thanks to the Christian fundamentalists.

A new kind of spook house, thanks to the Christian fundamentalists.In the 1980s the wild phase of gay liberation came to an end because of AIDS, which the Christian right hailed as God’s punishment on these sinful degenerates. A young man dying miserably of AIDS was a standard scene, along with Satanic rituals, bloody abortions, and teen-age murders, in the lurid Hell Houses sponsored by various churches in an effort to dramatize the wages of sin. But I saw, and still see, the AIDS epidemic as nature's way of rebalancing, its mysterious and often cruel way of curbing excesses.

Closed until further notice.

Closed until further notice.Today the meatpacking district is full of pricey restaurants and boutiques, gourmet food retailers, and nightclubs where on weekends trendy people sip overpriced drinks three-deep at the bar. The district is even promoted as “glamorous” and a “must-see,” and there are walking tours for the uninitiated.

The Meatpacking District today: a girl go-go dancer dances on the bar at the Hogs n' Heifers.

The Meatpacking District today: a girl go-go dancer dances on the bar at the Hogs n' Heifers.A scene for the well-scrubbed and young.

David Shankbone.

The Gansevoort Meatpacking NYC, a new luxury hotel at 18 Ninth Avenue, offers breathtaking panoramic views of the city and sunsets over the Hudson, and a rooftop swimming pool with underwater lights. And at Ninth Avenue and West 14th Street there is even a glass-walled Apple store where I have gone several times to have my computer looked at by a “genius.” The Toilet, I’m informed, is now a fancy restaurant, a transformation that I can’t regret. Score 3 – or maybe 3, 4, 5 – for gentrification. No need to keep score any more; my point is made.

My Apple store at Ninth Avenue and West 14th Street. No go-go dancers, just geniuses.

My Apple store at Ninth Avenue and West 14th Street. No go-go dancers, just geniuses.AchimH Of course the Village in those days was more than screaming women at the House of Detention and gay men having anonymous sex indoors and out. There was jazz, theater, and cabaret, all of them with a wild side at times. The funky creativity of the time seemed to involve self-destruction as well, and drugs and alcohol took their toll. But as the rents went up, the really wild side – Beats and hippies, artists and musicians -- moved to the East Village, leaving what became known as the West Village relatively quiet. I remember crossing Third Avenue into the East Village and sensing at once a different, shabbier, wilder atmosphere. Above all on Saint Mark’s Place there were head shops, often incense-ridden, stepping into which was like embarking on a drug-induced adventure. They offered everything but drugs themselves (though drugs were probably available close by): drug paraphernalia of every kind including pipes and water pipes, psychedelic posters with glaring colors and ornate lettering, and dim, weird lighting that reminded me of my peyote fantasies. I didn’t mind savoring this atmosphere briefly, but it always kindled in me a keen longing for the outdoors and normal air and light.

Saint Mark's place today: less shabby, less psychedelic, less wild.

Saint Mark's place today: less shabby, less psychedelic, less wild.Beyond My Ken

Today the 14th Street boundary between uptown and downtown seems to have vanished, and Village rents are often higher than on the Upper East Side. Bleecker Street near where I live is lined with designer clothing stores – Marc Jacobs, Brunello Cucinelli, Ralph Lauren – that I never enter, and right downstairs is the Magnolia Bakery of Sex and the City fame, sought out by busloads of tourists, and foreign visitors with guidebooks, who click photos of one another in front of the fabled bakery and sit on my doorstep gobbling delicious cupcakes that I, a good vegan, shun.

Even in winter they line up. I'm four flights above.joe goldberg

Do I hate the tourists and the cupcake gobblers and the patrons of the pricey stores? No, not at all. They don’t threaten me or anyone else, and if sometimes they leave a little litter – mostly crumb-filled cupcake wrappings and crumpled paper napkins – at least it isn’t used condoms or drug stuff. And they show that today’s Village, however gentrified, still has vitality, albeit a vitality different from that of the Golden Age of yore, whichever Golden Age one has in mind. And not all the restaurants are overpriced; when I go out with friends for lunch, within walking distance we can eat Irish, Indian, Chinese, or Mexican and stay within our budget. Nor is this a gated WASP-only community; running errands I may hear four or five foreign languages and see a sari, or even a burka veiling a Moslem woman from head to foot with only two thin slits for her eyes.

Someday a new batch of survivors will look back to a Golden Age when foreigners with their noses deep in guidebooks flocked to the Village, and people lined up in front of the storied Magnolia Bakery, mouth watering at the mere thought of the scrumptious little cupcakes within, and cyclists zoomed for miles along a riverside bike path with great views of the Hudson, and sunbathers baked their skin stretched out on the real or fake grass of a pier jutting out into the river. Ah, those were the days!

A note on the East Village: The New York Times of April 6 last announced that outlaw artist Clayton Patterson was finally leaving the Lower East Side where he has lived for 35 years, most of it in a storefront home at 161 Essex Street. A photo shows him as a stocky man with unkempt long gray hair topped by a baseball cap embroidered with a grinning skull, his beard in a double braid tumbling down his chest: the very image of the rebel artist, backed up by a phalanx of admiring musicians, sinister-looking types in leg-clinging jeans and dark jackets, all staring at the camera defiantly. And why is he leaving? Because the wildly creative East Village he knew and loved is being invaded by luxury apartments, corporate chain stores, overpriced parking meters, and pretentious restaurants – in short, gentrification.

“There’s nothing left for me here,” he told the Times reporter. “The energy is gone. My community is gone. I’m getting out. But the sad fact is: I didn’t really leave the Lower East Side. It left me.”

The moment the Canadian-born artist arrived in New York in 1979, his world had been the Lower East Side’s squatters, anarchists, tattoo artists, drug-ridden poets, and skinheads, the outcasts and the down-and-outers he photographed repeatedly, and whose brutal ousting from Tompkins Square Park by the police in 1988 he recorded on tape. One crucial event determining his departure was the eviction at age 88 of artist and actor Taylor Mead from his apartment on Ludlow Street (see post #91), following which Mead died within a month. “No one gave a damn about Taylor Mead,” he declared, and admitted that he feared the same fate here for himself.

Graffiti on an East Village telephone box advertising a 2012

Graffiti on an East Village telephone box advertising a 2012reunion of survivors of the 1988 Tompkins Square Park riot.

David Shankbone

So where is this last of the bohemians going? To a chalet in the Austrian village of Bad Ischl, in the Alps. Why there, of all places? Because a creative community of writers, artists, tattoo designers, and musicians is flourishing there, and because he is “big” as an underground photographer in Austria, far more so than back here. His friends see in his departure further evidence of the cultural decline of New York, which they insist is becoming a playground for money and sterilized housing. Yes, even the outlaw East Village is succumbing, and maybe the loss there far outweighs the gain.

Coming soon: In two parts: Norman Mailer, acclaimed author, womanizer, wife-stabber, drunk. His brilliant coverage of the 1967 Pentagon March and the chaotic 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, including a police riot and plenty of tear gas and Mace.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on August 03, 2014 04:49

July 27, 2014

137. Roy Cohn, Attack-Dog Lawyer and AIDS Denier, plus Outing

I first heard of him when, studying in France in 1953, it was reported that two twenty somethings, members of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s staff, had been sent to Europe to investigate waste and mismanagement in U.S. Army bases, embassies, and offices of the U.S. Information Service, and see if there was any – heaven forfend! -- Communist or left-leaning literature available there. This was, after all, the early days of the Cold War, and the rabidly anti-Communist senator from Wisconsin stretched his sinister shadow as far as Western Europe. The two peripatetic staff members were Roy Cohn and David Schine, though at the time their names barely impinged on my psyche. Their 18-day whirlwind tour, highly publicized, earned them the label “junketeering gumshoes” from a disgruntled U.S. employee in Germany whom they accused of having once signed a Communist Party petition, a charge that later cost him his job.

But this was mere prelude. I returned that year to the U.S. and began graduate studies in French at Columbia, which brought me to New York. By the summer of 1954 I was busy writing my master’s thesis, but not so preoccupied that I didn’t find time every evening to join a thong of students in the campus TV room watching the Army-McCarthy hearings. The hearings had been provoked by Roy Cohn’s excessive demands on the Army to give special privileges to his friend David Schine, who had been drafted into the Army but, in Cohn’s opinion, merited nightly passes while in basic training, exemption from onerous kitchen duties, and respect such as few draftees ever received. So oppressive had Cohn’s interference become, climaxed by a threat to “wreck the Army,” that Army Secretary Robert T. Stevens brought formal charges against McCarthy and Cohn. Extensive Senate hearings followed, and it was the daily evening summary of those hearings that I and twenty million others watched obsessively.

The hearings revealed to us and the public at large the heavyset McCarthy’s obnoxious manner, and Roy Cohn’s heavy-lidded eyes, deep tan, and knowing grin, and above all his aggressiveness; they were not people you would care to meet. Climaxing the hearings was Army counsel Joseph Welch’s passionate response, when McCarthy questioned the loyalty of one of Welch’s aides: “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” -- a query that provoked applause from the gallery. Indeed, it was a turning point in McCarthy’s career; from then on his support steadily eroded. In December 1954 he was formally censured by the Senate on a number of grounds.

McCarthy (left) and Cohn at the hearings.

McCarthy (left) and Cohn at the hearings.Among the students watching the hearings, and not just the gay contingent, it was commonly assumed that Cohn and Schine were lovers; how else could you explain Cohn’s fanatical insistence on special favors for his friend? And how else explain certain innuendoes that spectators elsewhere may not have caught, as for instance when McCarthy asked Welch for a definition of “pixie,” a word that Welch had used casually in a question, and Welch replied that a pixie was a close relative of a fairy. Or when Senator Flanders, Republican of Vermont, sauntered into the hearings one day to suggest that the relationships of those involved should be further explored.

The going Washington rumor of the time about McCarthy, as I knew indirectly from an uncle who was a PR man there, was that the senator had a babe stashed away in a hotel. And since McCarthy had an abundance of enemies, savvy Washingtonians wondered why no one had leaked this to the press. The explanation: everybody else probably had a babe stashed away also, and didn’t want to open that particular can of worms. But there were other rumors, too, as I told the cousin who had passed this on to me: McCarthy, still a bachelor in his early forties, was gay. But in 1953 he married a researcher in his office and four years later they adopted a baby girl. His homosexuality was never established, but what also went unreported was his alcoholism, which contributed to his death in 1957.

Cohn in 1964. Did he ever smile? Certainly not

Cohn in 1964. Did he ever smile? Certainly notin a courtroom. The hearings made Roy Cohn famous, but who was he? He was born in 1927 in New York City to a nonobservant Jewish family, his father a judge with considerable political clout in the Democratic Party. Raised in a Park Avenue apartment, he proved to be a bright student, attending local schools and then Columbia Law School, and was admitted to the bar as soon as he reached the age of 21. Appointed to the staff of the U.S. Attorney in Manhattan, he impressed others as precocious, brilliant, and arrogant, qualities that would characterize his whole career. He was soon making a name for himself prosecuting subversives, including Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1951, and was transferred to Washington to serve as special assistant to the Attorney General. In 1953 he went to work for Senator McCarthy, and got his friend David Schine, the son of a multimillionaire real estate mogul, a job as consultant; their 18-day junket to Europe soon followed.

Cohn’s work with McCarthy ended in 1954, but his career had barely begun. Returning to New York, he joined the New York law firm Saxe, Bacon & Bolan, brought it numerous high-paying clients, and moved into the East Side townhouse that housed the firm’s offices, which made for a minimal commute. His professional and private life were so intermixed that his colleagues were not surprised to see his doting mother wandering about the office, as she often did. An only child, he was close to her and, following his father’s death in 1959, moved into her seven-room Park Avenue apartment. After she died in 1969 he moved into a 33-room townhouse at 39 East 68th Street (presumably the same one already housing his law firm’s offices), though he also had a house in Greenwich, Connecticut, and in the summer went to Provincetown.

Combative by nature, he became known for his aggressive courtroom technique, intimidating prosecutors, flustering witnesses, and impressing jurors with his photographic memory, so that he rarely referred to notes. “My scare value is high,” he once boasted. “My area is controversy. My tough front is my biggest asset. I don’t write polite letters. I don’t like to plea-bargain. I like to fight.” No, not a fellow you’d care to know, but maybe just the attorney you need, if you’re involved in serious litigation and have a lot to lose. Esquire magazine called him “a legal executioner”; the National Law Journal, an “assault specialist.” His clients over the years included a juicy mix: real estate mogul Donald Trump; Mafia bosses Tony Salerno, Carmine Galante, and John Gotti; the owners of the popular New York nightclub Studio 54; the New York Yankees; Cardinal Spellman; and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York.

Short and light of weight, he was almost fragile in appearance (an impression well masked by his aggressive demeanor), with thinning hair and blue eyes often bloodshot from his late hours at fashionable discotheques. Socially active, he gave lavish parties where the guests included many celebrities. All his life he had a penchant for the rich and powerful, and given his legal ability and political connections, they had a penchant for him. Among his friends were President Ronald Reagan, Norman Mailer, Bianca Jagger, Barbara Walters, Rupert Murdock, William F. Buckley, Jr., William Safire, and numerous Democratic and Republican politicians at every level, from the obscure nether depths to the shining heights. Who, indeed, didn’t he know?

Logo of the IRS, his nemesis. Not that he was free of troubles. To keep his income tax to a minimum, he had his law firm pay him a modest salary of a mere $100,000 a year, while giving him all kinds of perks that wouldn’t be taxed: a rent-free apartment, partial payment of the rent on his Greenwich, Connecticut, home; a chauffeured Rolls Royce and other limousines; and his bills at chic restaurants – perks said to total a million dollars a year. From 1973 on he paid no income tax at all. But the IRS, no doubt mindful of his sumptuous life style, audited his tax returns for over twenty years and collected more than $300,000 in back taxes, a mere fraction of what he finally owed them. Their pursuit of him would continue even after his death.

Logo of the IRS, his nemesis. Not that he was free of troubles. To keep his income tax to a minimum, he had his law firm pay him a modest salary of a mere $100,000 a year, while giving him all kinds of perks that wouldn’t be taxed: a rent-free apartment, partial payment of the rent on his Greenwich, Connecticut, home; a chauffeured Rolls Royce and other limousines; and his bills at chic restaurants – perks said to total a million dollars a year. From 1973 on he paid no income tax at all. But the IRS, no doubt mindful of his sumptuous life style, audited his tax returns for over twenty years and collected more than $300,000 in back taxes, a mere fraction of what he finally owed them. Their pursuit of him would continue even after his death.Cohn’s courtroom tactics were condemned by many in his profession, and three times – in 1964, 1969, and 1971 -- he was tried in federal courts on charges ranging from conspiracy to bribery to fraud, but was acquitted each time. In 1976 a federal court determined that he had entered the hospital room of a dying client and, by misrepresenting the nature of the document, got him to sign a codicil to his will that would have made Cohn one of the man’s executors. Cohn’s reaction to these incidents? A smear: the authorities were out to “get” him. And get him they finally did: on June 23, 1986, when he didn’t have long to live, he was disbarred by the unanimous decision of a five-judge panel of the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court for unethical and unprofessional conduct, including misappropriation of clients’ funds, lying on a bar application, and the 1976 matter of pressuring a client to amend his will.

Cohn always claimed that his friendship with Schine involved nothing sexual, and some biographers have come to that conclusion. But by the 1980s he was obviously in poor health. A friend once asked him, “Roy, you don’t have AIDS, do you?” To which Cohn replied, “Oh God, no! If I had AIDS, I would have thrown myself out the window of the hospital. I have liver cancer. There would be no reason to stick around and live if I had AIDS.” And that was his story to the end: liver cancer, not AIDS.

But Roy Cohn was gay and he did have AIDS. In 1984 a routine visit to his doctor had discovered malignant growths on his body. His young lover Peter Fraser later said that Cohn cried only a tear or two and then dealt with the situation practically and began writing his memoir longhand on yellow legal pads. Peter and a law partner of Cohn’s were the only ones who knew for sure that Cohn had AIDS, and for as long as he could, Cohn tried to live normally, which for him involved lunching, partying, water skiing, traveling, and of course doing deals in politics and business. On December 31, 1985, he gave his traditional New Year’s Eve party in the second-floor foyer of his townhouse; among the hundred guests were Carmine DeSapio and Andy Warhol (a fascinating juxtaposition; see posts #135 and #108). Cohn received them in a white dinner jacket and red bow tie with sequins, said he looked forward to seeing them all again next year.

President and Mrs. Reagan, 1981. Being Cohn’s lover, however clandestinely, was fraught with adventure. Raised on a farm in New Zealand, Peter Fraser had left there at age nineteen with only a pack on his back to see the world. Blond and attractive with a sinewy body, he met Cohn at a party in Mexico and was immediately swept up into Cohn’s opulent life style: lavish parties with celebrity guests, visits to the rich and powerful, trips hither and yon to the most fashionable places; he never rode the New York subway until Cohn died. Once Peter went to the White House as Cohn’s “office manager,” the same label used for his predecessors. “Why don’t you come meet a friend of mine?” Cohn suggested. As Cohn led him across the crowded room, Peter scuffed his shoe and the sole came off, so he dragged his foot on the floor so he “wouldn’t go flop-flop.” Then Cohn said, “I want you to meet the President and Mrs. Reagan.” Peter reported that Reagan was very warm, probably thinking that this poor boy dragging his foot was handicapped.

President and Mrs. Reagan, 1981. Being Cohn’s lover, however clandestinely, was fraught with adventure. Raised on a farm in New Zealand, Peter Fraser had left there at age nineteen with only a pack on his back to see the world. Blond and attractive with a sinewy body, he met Cohn at a party in Mexico and was immediately swept up into Cohn’s opulent life style: lavish parties with celebrity guests, visits to the rich and powerful, trips hither and yon to the most fashionable places; he never rode the New York subway until Cohn died. Once Peter went to the White House as Cohn’s “office manager,” the same label used for his predecessors. “Why don’t you come meet a friend of mine?” Cohn suggested. As Cohn led him across the crowded room, Peter scuffed his shoe and the sole came off, so he dragged his foot on the floor so he “wouldn’t go flop-flop.” Then Cohn said, “I want you to meet the President and Mrs. Reagan.” Peter reported that Reagan was very warm, probably thinking that this poor boy dragging his foot was handicapped. On another occasion a New York socialite hosting a luncheon introduced Peter, to his astonishment, as Sir Peter Fraser. The next day a society columnist mentioned, among the luncheon guests, Peter Fraser, the Prime Minister of New Zealand. But when Americans, remembering the Army-McCarthy hearings, asked him how he could be associated with a man who did those awful things back in the 1950s, Peter, who was in his twenties, could reply honestly, “I don't know about any of that.”

While almost nothing is known of Cardinal Spellman’s final days and death (post #136), Roy Cohn’s ending is well documented. When diagnosed with AIDS, Cohn thought he had six months to live, but it turned out to be two years. He was taking shots of Interferon, which sapped his energy and disoriented him; becoming aware of this, he panicked and then became depressed, since he had always prided himself on his intellect. Troubled breathing and short-term memory loss followed, and he tried the experimental drug AZT, which many thought did more harm than good. Rumors circulated about Roy Cohn’s having AIDS, about his dying.

The dementia intensified. “The six senators who were here this afternoon,” he told Peter, “I’m going to talk to them, and you are all going to be sorry.” Or he would accuse Peter of trying to kill him, and only after much persuasion became convinced that Peter was his friend. When he got back from a stay in a hospital, telegrams came wishing him well, one of them from President Reagan. Looking gaunt and wasted, he was interviewed by Mike Wallace on TV, denied being homosexual or having AIDS. He flirted with the idea of suicide, tried one night to get his bottles of sleeping pills open, couldn’t cope with the childproof bottles, finally at Peter's insistence went back to bed.

When he invited other boyfriends to come for a last visit, Peter raged with jealousy.

“What’s he coming in for?” he would ask.

“I’m dying, goddamit!” Cohn would shout. “It may be the last time I see him.”

“You said that the last four times!”

When the New York State Bar Association began disbarment proceedings against him, he would go to the proceedings in his red convertible Cadillac, top down, and swagger into the closed hearing room. But in June 1986, when a reporter phoned with the news that he had at last been disbarred, he announced, “I couldn’t care less,” then went to his room and cried, and wouldn’t eat unless Peter forced him. His once fiercely resonant voice, the terror of witnesses, became a whisper, then fell silent. He died in a hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, on August 2, 1986, at age 59; Peter was there, holding his hand. The hospital announcement made it clear that he died not of cancer but AIDS. In his coffin he wore a tie bearing President Reagan’s name, though the Reagans did not come to the memorial service held in October. He was buried in Queens. Though he left his property to Peter and a longtime law partner, the IRS froze his assets; he still owed them millions.