Clifford Browder's Blog, page 42

February 22, 2015

168. Thomas E. Dewey, Gangbuster

In the suburb of Chicago where I grew up – a mostly white, very middle-class, very Republican community – the only crime wave was the depredations of a “phantom burglar” who for months eluded the police, becoming in the process both a bugbear and a legend. Real crime, and corruption too, existed just to the south of us in the wicked, corrupt, and very Democratic city of Chicago. But organized crime was almost unknown to us, something that reputedly flourished in that other, more distant big city, the wicked, corrupt, and very Democratic city of New York. (For white Midwestern suburbanites, all big cities were wicked and corrupt … and enticing.) But crime in New York, we understood, had been curbed by a stalwart defender of law and order, a special prosecutor and district attorney by the name of Thomas E. Dewey, a Republican who certainly deserved to be President.

So it was that I knew him as a twice unsuccessful candidate for the presidency, a master of platitudes and glowing vague phrases: in his photos an earnest-looking, gentlemanly type, slim and dapper, with a well-trimmed mustache, whose opponents called him the “little man on the wedding cake.” A hard-working, diligent public servant, to be sure, and undeniably honest, but a bit lacking in color and warmth, two qualities that Harry Truman, his 1948 nemesis, had plenty of. But there is much more to Thomas E. Dewey than this, and his story is intimately linked to the history of New York City and State.

Born in Michigan in 1902, the son of a small-town newspaper editor, Dewey studied law and came to New York, where he started a lucrative practice on Wall Street. New York City in the Depression years of the 1930s was governed by Fiorella La Guardia, arguably the best, most honest, and most energetic mayor in the city’s history. But even under the Little Flower’s rule, many aspects of the city’s life were controlled by organized crime, which prompted cries for reform. In 1930 Dewey was appointed Chief Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, to investigate corruption in the city. His first great success came in 1933 with the prosecution for tax evasion of racketeer and bootlegger Waxey Gordon, who was sentenced to ten years in prison. What may not have been known to the public was the fact that Gordon fell victim to a gang war; the evidence that did him in came from his rivals, the Sicilian-born gangster Charles “Lucky” Luciano and that supposed rarity, a Jewish mobster, Meyer Lansky: a first indication of the strange relationship between organized crime and the forces of law and order out to eradicate it.

In 1935 Governor Herbert H. Lehman, a Democrat, heeding a grand jury’s charge that the current D.A. was lax in investigating the mob and corruption, asked four prominent Republicans to serve as special prosecutor in New York; all refused and recommended Dewey. Appointed to this new position, Dewey recruited over 60 assistants, investigators, stenographers, and clerks, and proceeded vigorously, tapping telephones quite legally and employing his thoroughness and attention to detail to bring down organized crime.

And who exactly were his targets? The Commission, the governing body of the American Mafia, formed in 1931 to end the murderous wars between different factions for control of the Mafia. The Commission included the bosses of seven families: the five families of New York, the Chicago boss Al Capone, and the Buffalo boss Stefano Magaddino. The chairman of the Commission was one of the New York bosses, Lucky Luciano. Though the Commission was mostly Italian, and especially Sicilian, in origin, it allowed Jewish mobsters such as Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, and Dutch Schultz to work with them and attend some meetings. As a result, big-time crime in the U.S., and above all in New York City, was indeed truly organized and a force to be reckoned with, and Thomas E. Dewey was out to destroy it.

One of his chief targets was Dutch Schultz, whom J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI had labeled Public Enemy No. 1. A former bootlegger, at the end of Prohibition Schultz had switched to racketeering and extortion, using strong-arm tactics such as beatings and stink-bomb attacks to extract “dues” from terrified restaurant owners. Known for his brutality, when he suspected that an associate was cheating him, he confronted him angrily, whipped out a handgun, stuck it in the man’s mouth, pulled the trigger, and then apologized to another associate for killing someone in front of him. The victim’s body was later found in a snow bank with multiple stab wounds to the chest. When queried by the witness he’d apologized to, Schultz calmly replied, “I cut his heart out.”

One of his chief targets was Dutch Schultz, whom J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI had labeled Public Enemy No. 1. A former bootlegger, at the end of Prohibition Schultz had switched to racketeering and extortion, using strong-arm tactics such as beatings and stink-bomb attacks to extract “dues” from terrified restaurant owners. Known for his brutality, when he suspected that an associate was cheating him, he confronted him angrily, whipped out a handgun, stuck it in the man’s mouth, pulled the trigger, and then apologized to another associate for killing someone in front of him. The victim’s body was later found in a snow bank with multiple stab wounds to the chest. When queried by the witness he’d apologized to, Schultz calmly replied, “I cut his heart out.”It was not for these horrors that U.S. Attorney Dewey brought Schultz to trial, but for tax evasion – the same charge that would bring down Capone in Chicago. Schultz was convicted, but his lawyers got the case overturned and convinced the judge that their client could not get a fair trial in New York. So the trial was removed to the small town of Malone in rural upstate New York, where Schultz donated cash to local businesses, gave toys to sick children, and performed other charitable deeds, thus endearing himself to the locals. In 1935, to the astonishment of all, he was acquitted. Outraged, Mayor La Guardia ordered that Schultz be arrested on sight, should he return to the city, so Schultz relocated his operations to Newark, across the Hudson in New Jersey, where his mounting legal expenses forced him to reduce the pay of his underlings and thus undermined his authority.

Desperate, Schultz reportedly went to an emergency meeting of the Commission and asked permission to kill Dewey. The majority of the members voted against it, arguing that Dewey’s murder would stoke public fury and subject them to even more vigorous action by the authorities. Accusing the Commission of trying to steal his rackets and “feed him to the law,” Schultz left in a rage. Fearing that Schultz would act on his own, the Commission decided to eliminate not Dewey but Schultz. On the evening of October 23, 1935, two gunmen shot Schultz in the men’s room of a chophouse in Newark, and also killed two bodyguards and Schultz’s accountant. Gravely wounded, Schultz was taken to a hospital, where he lingered for 22 hours, delivering a rambling soliloquy while in and out of lucidity, before dying of peritonitis. Fearing conviction by Dewey, shortly before his death Schultz had had an airtight and waterproof safe built, into which he placed $7 million in cash and bonds. He and a bodyguard then transported the safe to an undisclosed site somewhere in upstate New York and buried it there. When Schultz and the bodyguard both died as a result of the Newark shooting, the location of the safe was lost. Gangland lore says that other mobsters searched for the safe over the years, and even today treasure hunters meet annually in the Catskills to hunt for it. So the legend of Schultz’s lost treasure has survived the memory of Schultz himself.

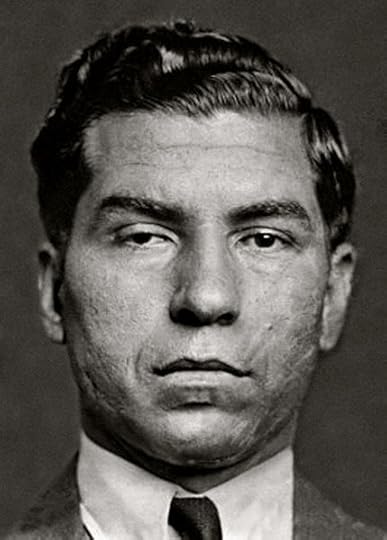

Only years later would Dewey learn of Schultz’s desire to murder him, but awareness of it would not have deterred him. Yet the threats to him were real, and La Guardia assigned a picked force of 63 policemen to guard his office. It was just as well, for his next target was none other than the mob’s kingpin, Lucky Luciano himself. Though born in Sicily, Luciano came to the U.S. at age 10 when his parents emigrated here and settled on the Lower East Side. As a teenager he got into crime and between 1916 and 1936 was arrested no less than 25 times for assault, illegal gambling, blackmail, and robbery, but spent no time in prison, which may explain how he got the nickname “Lucky.” Prohibition proved a windfall for him, and he and his partners were soon making millions through bootlegging. By the late 1920s he was involved in Mafia gang wars and survived an assault that was almost fatal, then in 1931 emerged as the chief organized crime boss in the U.S. and proceeded to modernize the Mafia, renouncing its strong-arm tactics for a corporate structure. His own crime family, one of five in New York City, controlled such rackets as illegal gambling, bookmaking, loan sharking, drug trafficking, prostitution, and extortion, and dominated waterfront activities, garbage collection, construction, the garment business, and trucking. Indeed, what did they not have a finger in? Luciano was now living high on the hog, with a suite (under another name) at the luxurious Waldorf Towers, and wearing custom-made suits, silk shirts, cashmere topcoats, and handmade shoes. He was often seen riding in a chauffeur-driven limousine or sporting about with a beautiful woman on his arm. Among his friends were George Raft and Frank Sinatra. But among his enemies was an energetic new U.S. Attorney out to destroy organized crime.

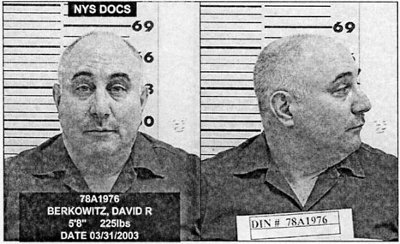

Luciano in 1936. Dewey decided to do it through Luciano’s involvement in prostitution. In February 1936 he conducted a massive raid on some 200 brothels in Brooklyn and Manhattan and arrested 10 men and 100 women. Instead of releasing those arrested, as was usual in vice raids, he took them to court, where the judge set bail at a figure too high for them to pay. Confinement and the threat of prison worked wonders: by March several defendants had implicated Luciano, who, being tipped off about his imminent arrest, decamped for Hot Springs, Arkansas, a favorite hangout for mobsters at the time. There in that healing environment his luck ran out, for a detective on another assignment recognized him and notified Dewey, who had him arrested and sent back under guard to New York, where he was held without bail and then tried on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution.

Luciano in 1936. Dewey decided to do it through Luciano’s involvement in prostitution. In February 1936 he conducted a massive raid on some 200 brothels in Brooklyn and Manhattan and arrested 10 men and 100 women. Instead of releasing those arrested, as was usual in vice raids, he took them to court, where the judge set bail at a figure too high for them to pay. Confinement and the threat of prison worked wonders: by March several defendants had implicated Luciano, who, being tipped off about his imminent arrest, decamped for Hot Springs, Arkansas, a favorite hangout for mobsters at the time. There in that healing environment his luck ran out, for a detective on another assignment recognized him and notified Dewey, who had him arrested and sent back under guard to New York, where he was held without bail and then tried on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution.The jury heard 68 witnesses, 40 of them prostitutes or madams. One told how Luciano had told her, “I’m gonna organize the cathouses like the A&P,” and quoted him as saying that “you got to put the screws on” to keep madams and pimps in line. Trusting to his proverbial luck and not knowing who he was up against, Luciano, against his lawyers’ advice, took the stand to proclaim his innocence and deny knowing the witnesses. It was a dramatic confrontation: the king of crime vs. the king of prosecutors. Dewey subjected him to a rigorous four-hour cross-examination and repeatedly exposed him as a liar. Nor could Luciano explain why he, a man obviously of great wealth, claimed to earn only $22,000 a year. In his seven-hour summation Dewey labeled Luciano’s testimony “a shocking, disgusting display of sanctimonious perjury” and called the defendant “the greatest gangster in America.” On June 7, 1936, Luciano was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to 30 to 50 years in state prison. It was U.S. Attorney Dewey’s greatest triumph.

Polly Adler, celebrated madam and

Polly Adler, celebrated madam and author. Maybe we'll see her again. Since then many have questioned whether there was adequate evidence to convict Luciano, since he, like most mob bosses, avoided any direct and obvious connection with his illegal activities. Society brothel madam Polly Adler, later the author of the bestseller A House Is Not a Home, opined that Luciano was not involved in prostitution, since otherwise, having operated under mob protection, she would have known of it. But Dewey was now hailed as a gangbuster – a neologism that soon become the name of a popular radio show – and as such a national hero. He got results – 72 convictions out of 73 prosecutions -- and Americans love results.

A Republican in a very Democratic town, in 1937 Dewey got himself elected District Attorney of New York County and as such continued to prosecute mobsters and other offenders. Among the latter were Richard Whitney, a former president of the New York Stock Exchange, who pleaded guilty to embezzlement, and Fritz Kuhn, leader of the pro-Nazi German-American Bund, who was convicted of the same charge. Cheered by the successes of so stalwart and effective a champion of justice, the state’s Republicans, long out of office in Albany, began urging him to run for governor. And so began the transition of Dewey the gangbuster to Dewey the politician.

Coming soon: Dewey the politician, and why he never became President. And then, the dumpy little lady who became a friend of Maria Callas and everyone else who mattered (or thought they did), and who allegedly used Marilyn Monroe to snub the Duchess of Windsor. A glance at the world of the rich, the famous, and the no doubt totally irrelevant. But if you ever went on a treasure hunt or a scavenger hunt, you’re indebted to her.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on February 22, 2015 05:35

February 15, 2015

167. Chief Medical Examiner: A Grim but Necessary Job

Protesting Eric Garner's death, August 2014.

Protesting Eric Garner's death, August 2014.Thomas Altfather Good Recently the refusal of a grand jury to indict a New York City policeman for the chokehold death on Staten Island of Eric Garner, an unarmed African American, unleashed a frenzy of protests in the African-American community, some of which turned violent. But before this case could even be brought to the grand jury, Garner’s death had to be investigated and declared a homicide by the office of the city’s chief medical examiner, an important official whom most New Yorkers know little or nothing about. So who is this official and what are his duties? (Usually it has been a man, but at this moment it’s a woman, Dr. Barbara Sampson.)

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century New York City had several county coroners who investigated violent, sudden, or suspicious deaths – in short, any deaths not obviously the result of natural causes. This was an elected office, and to become a coroner your political connections were far more important than your medical training, or lack of it. As a result, the office of coroner became notorious for corruption and incompetence, and an outcry arose for reform. In 1915 the state legislature abolished the office and replaced it with something new: the office of chief medical examiner (CME), an official with formal medical training and experience who was appointed by the mayor. This new office was meant to be nonpartisan, objective, and completely free from political influence – a goal that, as shall become apparent, has not always been easy to achieve.

So what does the chief medical examiner do? He (or she) investigates all deaths resulting from criminal violence, accident, or suicide, and all that occur suddenly when the person is in apparent good health, and all occurring in any unusual or suspicious manner. He takes possession of suicide notes and all objects useful in determining the cause of death, maintains records of all deaths investigated, and delivers to the appropriate district attorney copies of records relating to any death that may have resulted from criminal activity. In a city the size of New York, such an office will have plenty of business. It employs some 30 medical examiners – most of them women -- who perform an average of 5,500 autopsies a year.

Few New Yorkers know where the chief medical examiner’s facilities are located, and few, I suspect, would care to visit them. The six-story headquarters building at 520 First Avenue, on the corner of East 30th Street, houses executive offices, the mortuary, autopsy rooms, and x-ray and photography facilities. Another building at 421 East 26th Street has state-of-the-art forensic laboratories where technicians in white protective gear and purple gloves examine bloodstained clothing and half-smoked cigarettes from crime scenes; there is even a forensic garage to examine vehicles for evidence relating to a death or deaths.

The forensic lab on East 26th Street. On the outside, well-scrubbed and neat.

The forensic lab on East 26th Street. On the outside, well-scrubbed and neat.So what is it like to work in the medical examiner’s office? Judy Melinek’s memoir Working Stiff: Two Years, 262 Bodies, and the Making of a Medical Examiner (2014), coauthored with her husband, gives some juicy details. I’ll spare viewers her accounts of autopsies, but other reminiscences are colorful in the extreme. She laughs at TV presentations of female examiners in stiletto heels and lots of cleavage, for at murder sites she wore sensible shoes and a windbreaker. When considering where to launch her career as a medical examiner, she was told, “If you really want to learn forensic pathology, do a rotation in New York City. All kinds of great ways to die there.” Some of the weirdest deaths she investigated:

· A hipster struck by lightning during a rooftop party in Chinatown, his body intact but his shoes blown off.· A suicide who jumped onto the subway tracks and was so smashed by a train that no blood was visible, it all having been absorbed into the bone marrow.· A worker crushed to death when an enormous machine used to make egg rolls in Chinatown exploded.· A man who in a fight got thrown down an open manhole into a pool of boiling water from a broken main and screamed for help, but was literally cooked to death before rescuers could reach him.· A man who was shot in the chest, the bullet getting flushed into the circulatory system and ending up in his liver.

A trick she learned from the police: When recovering a body from an apartment building, ask every tenant to make coffee; it covers the smell.

And advice to those who live alone with a cat. While a dog may sit next to your body for days, starving, be advised that your hungry cat will eat you right away. “I’ve seen the result.”

A heart perforated by a bullet in New York, 1937.

A heart perforated by a bullet in New York, 1937.The sort of thing the CME's office deals with regularly. Which makes one wonder why anyone in their right mind would want to be a medical examiner, recover bodies, and perform autopsies. But someone has to do it, and human motivation is diverse and mysterious. I once heard a male hospital intern tell another intern, “When I saw my first surgery in medical school, I said to myself, ‘That’s what I want to do!’ ” From surgery to save a life to doing an autopsy is probably but one short step.

Few New Yorkers know the name of the chief medical examiner or notice when one retires. Especially averse to publicity was Dr. Charles S. Hirsch, the CME from 1989 to 2013, who retired quietly at age 75. Mayor Bloomberg hailed him as a visionary and dedicated public servant to be especially remembered for his work in the aftermath of 9/11. On that occasion he and six aides rushed immediately to establish an on-site temporary morgue. When the first tower collapsed, he was hurled to the ground, bruising his body and breaking his ribs. Covered with white dust, he returned to his office, a ghostlike figure, to oversee the immense task now facing them: to identify some 20,000 body parts of victims that were collected over the days, weeks, and months that followed. Of the 2,753 people killed or missing, as of 2013 only 59 percent had been identified. For years he kept on his desk a glass bowl containing dust retrieved from his pocket after he was knocked to the ground that day.

Dr. Hirsch was respected for his refusal to bend to public opinion or the influence of the police, emphasizing his commitment to independent autopsies, “the only kind of autopsy I know how to give, whoever I may be working for.” This was a sharp contrast to the behavior of a predecessor, Dr. Elliot M. Gross, the CME from 1979 to 1987. In 1985 the New York Times ran a series of articles accusing his office of mishandling several cases of people dying in police custody, always to produce results favorable to the police. Among the highly controversial cases involved were these:

· Eleanor Bumpurs, an emotionally disturbed 66-year-old African American woman who brandished a 12-inch kitchen knife and was shot to death in the Bronx 1984 by six police officers trying to evict her. When the medical examiner found that she was hit by two shotgun blasts, Gross had the cause of death reworded to suggest only one blast, as the police had reported. The officer who fired the shots was tried for manslaughter but was acquitted. The city later settled with Bumpurs’s family for $200,000.· Ralph Tarantino, a 29-year-old Brooklyn man high on angel dust who in 1980 was beaten to death by police officers summoned because of a dispute between him and his neighbors. When an autopsy attributed the death to a fractured skull, Gross changed the finding to make the cause of death a procedure performed by doctors treating his injuries. An independent pathologist called Gross’s finding “irresponsible.”· Mark Safdie, a 32-year-old Brooklyn storeowner, whose wife called the police in 1983 when he began acting irrationally. The police forced him to the floor, handcuffed him, punched him, and refused to let his wife come near him. Taken to a hospital, he was dead on arrival. Gross’s autopsy report didn’t link his injuries to his death, which he attributed to “manic depressive psychosis with acute violent behavior.” A lawyer for the Safdies called the report a “whitewash.” · Michael Stewart, a 25-year-old African American subway graffiti artist who was arrested by transit police in 1983 for spray-painting graffiti on a subway wall. When he resisted arrest, he was beaten unconscious. After being booked at police headquarters, he was transferred to Bellevue Hospital, where he arrived handcuffed and comatose and died without regaining consciousness. Gross’s preliminary autopsy report asserted that he died of heart failure following a heart attack that put him in a coma – a report challenged by a physician witnessing the autopsy on behalf of the family. Gross’s later report declined to state explicitly what caused Stewart’s death. Six of the 11 white officers involved were tried on manslaughter and homicide charges and acquitted by an all-white jury.

A panel appointed by Mayor Ed Koch to study Gross’s conduct absolved him of misconduct but criticized his management. In 1987, when a second mayoral panel reached similar conclusions and recommended that he be replaced, Koch fired him, citing a need for new leadership in the office. Gross then sued the Times for libel, but in 1992 the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court found in favor of the Times, declaring that the complained-of language did not constitute defamation of character.

It is generally thought that the CME’s office under Dr. Hirsch has undergone a vast improvement unless, of course, one believes the New York Post, a tabloid specializing in sensationalist headlines. In an article of July 20, 2014, it chronicled these problems:

· The office has received $19.6 million in federal Homeland Security grants since 2005, but refuses to explain how it has spent the funds.· One official has traveled at taxpayer expense to conferences in Las Vegas, the Hague, Hong Kong, and Israel, and another to Croatia and Thailand.· The number of investigators who examine bodies at death scenes has been cut from about 40 to 20, and the work is suffering.· Examiners have removed brains and other organs from bodies without informing the next of kin retrieving the bodies for burial.· A body had to be dug out of a grave in New Jersey because it had been delivered to the wrong funeral home.· A body was sent to the wrong crematorium not once but twice.· Another body was lost, causing the office to dig up 300 graves in a Bronx potter’s field in an unsuccessful attempt to recover the remains.· The body of an 85-year-old woman was sent by mistake to a medical school to be used in anatomy classes, even while her son was making funeral arrangements; it was returned with embalming devices attached, blood spatters, and stitches on her lips and neck, causing trauma for her grieving son.

The Post concludes that the office has a history of criminality, waste, and incompetence, while millions of dollars of taxpayers’ money have been spent on plans and equipment useful only in a mass disaster, even though medical examiners are not first responders. Serious charges, but charges requiring verification from a more reliable source. But the current CME, Dr. Sampson, acknowledges that mistakes have occurred and emphasizes steps taken to avoid similar mistakes in the future, while stressing that the science performed in the lab was never in question.

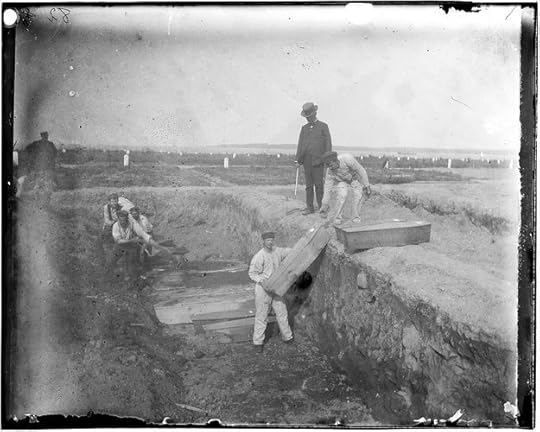

And what happens when the Office of Chief Medical Examiner receives an unidentified body? The body is fingerprinted and photographed, and the fingerprints are sent to state and federal law enforcement agencies for comparison with their records. If the body’s condition makes fingerprinting impossible, or no matching records are found, dental X-rays are taken and compared with X-rays from the decedent’s dentist, if available. If a skeleton is recovered, it is analyzed to determine age, race, sex, and other characteristics. And if the remains are still unclaimed or unidentified, they are interred in the city cemetery on Hart Island, a forbidden island where living visitors are most unwelcome, as described in a previous post (#49, New York Hodgepodge, March 3, 2013).

Burying coffins on Hart Island, circa 1890. A Jacob Riis photograph.

Burying coffins on Hart Island, circa 1890. A Jacob Riis photograph.The Chief Medical Examiner’s office also tries to locate missing persons. On November 8, 2014, it sponsored a first-ever Missing Persons Day, meeting with over a hundred families trying to locate a missing family member. Families provided information to relevant professionals, and volunteers were on hand to offer emotional and spiritual support. Big cities like New York are often viewed as bottomless dark holes into which individuals can vanish without trace. Using an array of state-of-the-art techniques, the CME’s office is trying hard to combat that impression.

But for all its efforts, many bodies remain unidentified. Yet a novel program is now under way to help cope with this problem. An article in the New York Times of January 21, 2015, tells how in room 501 of the New York Academy of Art in Manhattan a roomful of sculpture students are molding clay into faces that look almost alive. But the people represented in the sculptures aren’t just anyone; they are people who had met ugly deaths, usually by violence, and whose remains were found in desolate places throughout the city: on train tracks, in wooded areas, in dark basements. What’s going on?

These victims are all unidentified, and this is a workshop where fine art students are trying to recreate their faces so as to help the CME’s office identify them, comfort relatives, reopen cold cases, and in cases of homicide perhaps find the killers. Each student is given the replica of a skull and then, using any available information regarding age, sex, height, hair type or style, and clothing sizes, as well as a knowledge of anatomy, molds a block of clay into a lifelike face that, with marbles for eyeballs, slowly takes shape. Artistic license is not allowed, only accuracy. “I felt like he was talking to me,” said one student, “and that he’d be happy I was doing this for him.”

This is a unique and pioneering last-ditch effort, combining art and forensics, to identify these remains; if successful, it will be expanded to include more of the 1,200 bodies still unidentified by the CME’s office over the past 25 years. Photos of the sculptures will be turned over to New York police investigators and posted on an online public database of missing persons run by the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. Will identifications result? The class instructor, whose own sculptures of anonymous skulls for another organization in Virginia have yielded 30 hits, thinks so, but only time will tell.

Coming soon: Two posts on Thomas E. Dewey – one on him as a fearless gangbuster who brought Lucky Luciano, the Mafia kingpin, to trial (and then released him), and one on him as a politician who lacked one quality necessary to get into the White House. After that, a short, dumpy hostess who said she belonged to the world and used Marilyn Monroe to snub the Duchess of Windsor.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on February 15, 2015 04:34

February 11, 2015

166. Great Hotels of the Past and Present, part 2

Discussed in the last post, the Waldorf and Plaza are massive, hosting hundreds of guests every day. But there are smaller hotels of distinction as well. At the top of the list I would put the Algonquin at 59 West 44th Street, between Fifth and Sixth avenues. Built in 1902 with a red brick and limestone façade and named for the Indians who once lived in this area, it has a mere 181 rooms, small indeed compared to the Plaza and Waldorf. Frank Case, its longtime manager and owner, was fascinated by actors and writers and therefore welcomed them to his hotel and extended them credit. Among the habitués he snagged over the years were Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., John Barrymore, Sinclair Lewis, and William Faulkner, but he was a bit ahead of his time in welcoming women as well, including Gertrude Stein, Helen Hayes, and later Simone de Beauvoir. But what made the Algonquin famous was the Algonquin Round Table.

The Algonquin at night.

The Algonquin at night.Initiated in 1919, the Round Table was a select group of journalists, authors, critics, and actors who met daily for lunch in the main dining room, where they had their own table and waiter and exchanged opinions and witticisms and gossip. Prominent among them were humorist Robert Benchley, playwright and director George S. Kaufman, writer and critic Dorothy Parker, New Yorker editor Harold Ross, playwright Robert E. Sherwood, and critic Alexander Woollcott. Others who were in the group at times included actress Tallulah Bankhead, novelist Edna Ferber, and comedian Harpo Marx, always mute in his films but who in this select company presumably permitted himself to speak.

Members of the Round Table, circa 1919. Back row, from left:

Members of the Round Table, circa 1919. Back row, from left:Art Samuels, editor of Harper's Bazaar; Harpo Marx; Alexander

Woollcott. Front row, from left: playwright Charlie MacArthur;

Dorothy Parker. And how many of these names ring a bell today?

Besides exchanging chitchat, the Round Table members played poker and charades, staged a one-night revue, and acquired a reputation as wits when their quips and doings were reported widely in the press. But those quips could be mordant, and not for nothing had they named themselves “the Vicious Circle.” Critic H.L. Mencken, admired by them but emphatically not a part of the group, asserted that “their ideals were those of a vaudeville actor, one who is extremely ‘in the know’ and trashy.” And Groucho Marx observed, “The price of admission is a serpent’s tongue and a half-concealed stiletto.” It is true that they were probably more proficient in wisecracks than in meaningful insights, that they were arrogant and promoted themselves shamelessly, that in the last analysis most of them were not consistently and profoundly creative.

The Round Table flourished through the 1920s but then flaked away, it isn’t quite clear why. Edna Ferber knew the game was up when she arrived for lunch one day and found the group’s table occupied by a family from Kansas. Others in time realized that they had nothing more to say to one another and drifted off into other ventures. But they survived in the collective memory and ultimately helped win the Algonquin New York City Historic Landmark status in 1987.

It is hard to recreate the atmosphere of the Round Table, but here are a few quotes:· Alexander Woollcott: “All the things I like to do are either immoral, illegal, or fattening.”· Robert Benchley: “Behind every argument is someone’s ignorance.”· George S. Kaufman: “Epitaph for a dead waiter – God finally caught his eye.”· Dorothy Parker: “If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the people he gave it to.”· Dorothy Parker again: “I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.”

Yes, maybe the quips were rehearsed beforehand, and maybe they weren’t even uttered at the Algonquin. But they and the Round Table have become a cultural legend and as such merit a little respect … or at least a trace of a smile. Because what else of that cultural moment remains? Almost nothing.

Today the Algonquin promotes itself as a luxury hotel near the Theater District and just a block from the lights of Times Square, a boutique hotel rich in history and hospitality, with 37-inch TVs, backlit mirrors, and an iPod docking station in all the rooms. So even without Dorothy Parker and the Round Table, one can settle snugly in. I entered its hallowed precincts just once, years ago, before the addition of all these state-of-the-art amenities, when my uncle stayed there during a brief visit to the city and treated me to lunch in the restaurant. I can state without reservation that the vichyssoise soup that I had was, to put it mildly, out of this world; it vaulted me to the apex of joy.

A unique hotel – unique for many reasons – is the New York Palace Hotel, formerly the Helmsley Palace Hotel, at 455 Madison Avenue, in the very heart of midtown. It incorporates two very different structures that are linked by a two-story marble lobby: the landmark Italian Renaissance-style Villard Mansion, built by railroad magnate Henry Villard in 1884, and right smack against it, a 55-story tower built by real estate magnate Henry Helmsley in the 1970s; the resulting mishmash – or ingenious blend, if you prefer – opened as a luxury hotel in 1981.

The New York Palace Hotel (formerly the Helmsley Palace Hotel),

The New York Palace Hotel (formerly the Helmsley Palace Hotel), with the Villard Mansion in front.

Americasroof

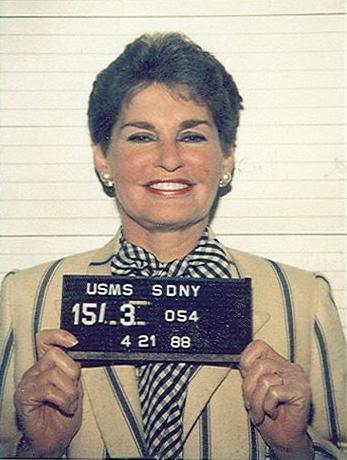

Leona Helmsley's mug shot. In spite of the glowing

Leona Helmsley's mug shot. In spite of the glowing smile, she ended badly. When you talk about the Waldorf Astoria, you end up discussing international relations. When you talk about the Algonquin, you end up discussing wit and witty people. And when you talk about the Helmsley Palace Hotel, you end up discussing Helmsley’s wife Leona, who managed the hotel from 1981 to 1992, and whose imperious presence has darkened these pages before (post #81, August 21, 2013). Since I have already chronicled her as the Queen of Mean, I shan’t honor her with further commentary. Suffice it to say that she terrorized the staff, but was finally undone by the federal government, which in 1989 convicted her on various charges including conspiracy, mail fraud, and tax evasion. What in my opinion doomed her irretrievably was testimony by her former housekeeper, who quoted her as saying, “Only the little people pay taxes.” That assertion the government simply couldn’t ignore, and didn’t. She served in prison from 1992 to 1994, when she was released with 750 hours of community service to perform, some of which she assigned to her servants, thus earning her another 150 hours of service.

When Leona died in 2007, she left $12 million to her beloved Maltese dog Trouble, who thus became the richest dog in the world and lived her last three years in security and comfort. They don’t make ’em like Leona anymore … at least, I hope they don’t. But the hotel, now rechristened the New York Palace Hotel, still flourishes, having been owned briefly by the Sultan of Brunei, and now by Northwood Investors, a New York-based real estate investment firm. Guest rooms start at $525 a night, and suites at $1,100. But I’m sure they’re comfortable.

And if you can’t afford such rates? You do what my mother did during a visit in the 1950s, you stay at the YWCA (or the WMCA), where she was quite comfortable. (It didn’t hurt that she’d once worked for the Y and was still in touch with friends she’d made there years before.) Or at some little budget hotel a bit off the beaten track, like the Larchmont at 27 West 11th Street in Greenwich Village, where single rooms range from $90 to $109 plus tax on weekdays – bargain rates indeed for Manhattan, and with a continental breakfast included. The neighborhood is residential and quiet, and the exterior of the hotel is modestly elegant. A friend once stayed there and I saw her room: small, with only basic furniture – a bed, a desk, a chair, little else. (The Larchmont now advertises a color TV in every room.) It was a place to lay your weary head at night, so you could rest up for forays into the city by day. Modest, but doable.

The Hilton Midtown with its soaring slabs. Clunky.

The Hilton Midtown with its soaring slabs. Clunky.Ingfbruno

And for those not interested in modest little budget hotels? How about the prestigious New York Hilton Midtown at the northwest edge of Rockefeller Center at Sixth Avenue and 53rd Street? A soaring 47-story building with 2,153 rooms in all, the biggest hotel in the city, it opened in 1963 and since then has hosted every U.S. president from John F. Kennedy on, as well as countless conferences and conventions. It has been called a microcosm of the city itself: vertical, crowded, diverse, and cash-driven. When it opened, New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable commented: “If the building has a look that suggests that one might put change in at the top and get something out at the bottom, this is only because today’s slickly designed commercial structures more and more frequently resemble a product, a machine, or a package.” Certainly it lacks the grandeur of the Waldorf or the Plaza, and has been said to mark a shift from the gracious and luxurious to the utterly functional. To my eye it looks like a big box surmounted by a slab; in short, it’s clunky. But guests don’t come there because of the looks of its exterior, and many an online review praises it (appropriately) to the skies.

Another bit of flashy modernity, the Marriott Marquis Hotel at Broadway and 45th Street soars above the hurly-burly of Times Square. It was born in controversy, for five historic theaters were demolished to make room for it – a demolition dubbed “the Great Theater Massacre of 1982.” Yet it has also been hailed as the first major project in the revitalization of Times Square, which, contaminated by nearby 42nd Street, was then undeniably seedy, with an abundance of go-go bars and “adult” theaters. If the Marriott, opening in 1985, turned its back on Times Square, focusing attention inward on its soaring atrium, it’s because it wanted no part of that seediness.

The Marriott Marquis, with the flashiness of Times Square in the foreground.

The Marriott Marquis, with the flashiness of Times Square in the foreground.Americasroof

The glass-walled elevators. No thanks.

The glass-walled elevators. No thanks.haitham alfalah Two features especially distinguish this state-of-the-art structure, and I have experienced both. The glass-enclosed “scenic elevators” crawl up the sides of a central column in the building’s atrium like big bugs, giving views of its soaring inner space. Visitors are said to flock from miles away and stand in line to access them, but when I rode in one years ago there was no wait at all. But even though I have no abnormal fear of heights, I was distinctly uncomfortable, having the feeling that this creeping creature with glass walls had no support under it and could easily plunge; when I got off and felt a solid floor beneath me, I was vastly relieved. On the other hand, the famous revolving bar and restaurant on the 48thfloor is a unique and wondrous rooftop experience, slowly making a complete turn each hour while giving breathtaking views of the city. I was once there with visiting relatives at night, and the views of the lights of Times Square were unforgettable.

A less publicized fact about the Marriott Marquis is its popularity for suicides. Those planning it probably think they will plummet gracefully and land with a dramatic thump in the lobby. Not so. One jumper leaped from the 43rdfloor, but his right arm and left leg were recovered on the 11thfloor, his other two limbs on the 7th floor, and part of his skull in the elevator shaft. And another suicide, leaping from the 23rd floor, ended up with one leg on the 10th floor and his torso on the 9th. Why this dispersion of remains? Because the falling body bounces off a variety of obtruding structures on the way, each breaking off a different part of the body. So would-be suicides should definitely keep away from the Marriott. (I would recommend the Palisades, except for the fact that there’s lots of poison ivy over there. Besides, that’s in New Jersey, and my focus here is on New York.)

So as not to end on a grisly note, here are some tidbits about the Waldorf Towers and its residents, courtesy of two young women who are the Waldorf’s luxury suite specialists:

· The most requested suite: the Presidential, where every President since Kennedy has stayed. When a President is there, they install bulletproof glass.· The largest suite: The Cole Porter, where the composer lived for 25 years. It rents at $150,000 a month and up. His piano is still there.· A rare bit of presidential trivia: when President Roosevelt came, he arrived via an underground railroad running from Grand Central Station to the fourth floor of the Waldorf basement. That way no one saw him arrive in a wheelchair.· The suite with the biggest and most exquisite bathtub: the Elizabeth Taylor, whose tub is big enough for three. (There’s no report of its ever having accommodated a threesome, however.)· The weirdest request ever: a VIP insisted that they raise the toilet height by one centimeter, which they did.· Objects that guests steal as souvenirs; teakettles, silverware, plates, ashtrays, and a candelabra.

So far as I know, there is no Lucky Luciano Suite. With this hodgepodge of trivia, I conclude.

Note on post 162.5, Big Bank, Big Real Estate: The feature page-one article of the Sunday New York Times of February 8, 2015, tells how foreign billionaires are secretly buying luxury condos in the soaring glass towers sprouting all over midtown Manhattan. The article focuses on the two dark glass towers of the Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle, where condo buyers include a Chinese businessman whose properties in Jersey City have been investigated for unsanitary conditions; a Scottish businessman the collapse of whose investment firm in the U.K. lost the savings of 30,000 people; an Indian CEO of a global mining conglomerate responsible for severe pollution in India and Zambia; and a Russian oligarch accused of dubious financial transactions in Angola. Just identifying these buyers took the Times a whole year, as they went from source to source to source, unpeeling layers of secrecy.

The Time Warner Center: more soaring slabs.

The Time Warner Center: more soaring slabs.Youngking11 These and other condo buyers obviously have good reason to desire anonymity, often buying condos in the name of a relative or a shell company such as an LLC (limited liability company), thus quite legally concealing their identity. Many of them are absentee owners who are here only sporadically, paying no city income tax and often receiving hefty property tax breaks as well. Our previous mayor, Michael Bloomberg, encouraged purchases by foreign billionaires, on the assumption that their lavish spending would trickle down to doormen, concierges, cleaners, drivers, construction workers, shopkeepers, and restaurants, but so many of the buyers are absentee owners that it hasn’t worked out that way. So some local politicians, noting that the city is spending money on services the absentees benefit from, have proposed an international residents tax.

Buyers pay millions for a condo – anywhere from $2 to $25 million and up -- but if they sell the condo a few years later, they make millions more. And as they snap up condos, they drive up real estate prices in the city generally. Which brings me back to the layman’s query posed by my post #162.5 on Big Real Estate: is this a real estate bubble, and if so, is it about to burst? During real estate busts in the past, I confess to having felt a certain grim satisfaction in seeing luxury residential high rises at night with a third or less of the windows lit up, suggesting that two-thirds or more of the units remained unsold, with resulting huge losses to the developers. Not the most generous of attitudes, I admit, but one gets tired of endless development, endless construction, endless greed. Will history repeat now, and soon? I have no idea. Let’s just wait and see.

Coming soon: The lady whose office performs 5,500 autopsies a year, and who wants to make sure that no more corpses get lost. And then: Prosecutor Dewey vs. Lucky Luciano, the kingpin of organized crime, and why did Dewey finally let him go? And then: the short, dumpy, homely little woman who said she belonged to the world, became famous, and feuded with the Duchess of Windsor.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on February 11, 2015 06:43

February 8, 2015

165. Great Hotels of the Past and Present, part 1

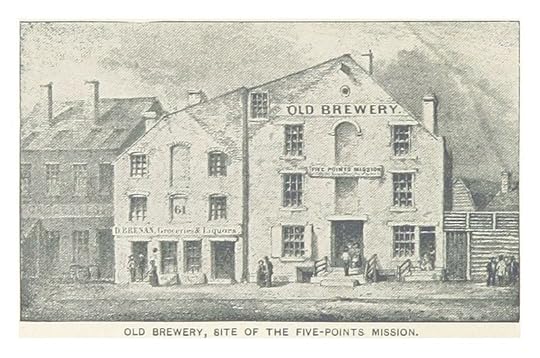

New York abounds in hotels – how could it not, given the constant influx of visitors? -- and some of them have become legendary. But it wasn’t always this way. Back in the eighteenth century there were no hotels in the sense that we use the term, only inns or taverns that were usually remodeled private houses. The first building erected specifically to serve as a hotel in the United States was probably the City Hotel, built in the 1790s on lower Broadway. Its large assembly room housed prestigious social functions and concerts, until it was demolished in 1849 to make room for shops.

The nineteenth century saw the appearance of palace hotels designed to offer Everyman the comfort and luxury enjoyed by the ruling classes of Europe, a glowing democratic concept that would also, if done right, line the pockets of architects and managers. The first of these was the Astor House, on lower Broadway opposite City Hall Park. A five-story granite Greek Revival structure, it was built in 1834-36 for John Jacob Astor, the fur trade king turned real-estate magnate. Hailed as the “grandest mass” in town, it had many fine public rooms, 309 rooms that would house up to 800 guests, and running water pumped by steam to the upper stories – an unprecedented luxury and engineering feat in a city that had yet to build a modern water supply system providing running water to public and private structures.

The Astor House also had gas lighting provided by its own plant, and a restaurant where guests and local merchants could choose from some thirty meat and fish dishes daily. Its ballroom hosted the well-attended balls of the elite, and its corridors were crowded daily with merchants and loafers whose manners, to judge by a contemporary sketch, left something to be desired, since many sprawled on their chairs and propped their feet up on whatever object – table or chair or wall– offered them a foot rest: the very sort of slovenly manners that Mrs. Trollope, the quintessential sharp-tongued English biddy, had skewered deliciously in her travel book Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832). Yet for decades this hotel was an internationally renowned meeting place for literati and the powerful, until the city’s expansion northward left it eclipsed by newer hotels farther uptown.

But even in those later years it was of note, for during the Civil War its vast Rotunda Bar was a popular meeting place for war contractors and the government officials they dealt with, and assorted wheeler-dealers looking to patriotically line their own pockets. In the gas-lit, smoke-filled atmosphere a minister without a congregation might be tracking down rumors of a supply of imported Enfield rifles held up for some reason by Customs, while a commission broker, having delivered to the Army five thousand overcoats of the best cheap shoddy on the market (which might, or might not, turn spongy if exposed to heavy rain), celebrated the deal with a toast to the “old flag, the true flag, the red, white, and blue flag,” clinking whisky glasses with a compliant Army inspector (a pal of his) and an assistant quartermaster general.

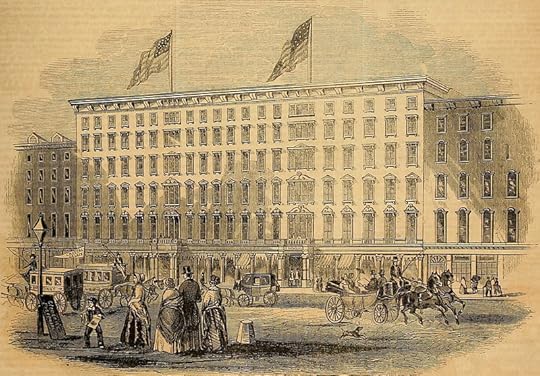

The St. Nicholas Hotel, 1853.

The St. Nicholas Hotel, 1853.Meanwhile, as the city surged uptown, the six-story, 600-room St. Nicholas Hotel opened on Broadway at Broome Street in 1853. A massive structure with a gleaming white marble façade, it offered the innovation of warm air circulating through registers to every room – a luxury that even the Astor House couldn’t offer. Other attractions included walnut wainscoting, frescoed ceilings, gas-lit chandeliers, hot running water, a telegraph in the lobby, a bridal room with four chandeliers and a canopied bed upholstered in white satin, and steam-powered washing machines in the basement. There were opulent parlors for ladies and gentlemen, a sumptuous reading room, and a stately second-floor dining room where liveried Irish servants escorted guests to their seats. And on Broadway right next to the hotel’s main entrance was Phalon’s Hair-Dressing Establishment where, under a frescoed ceiling with an ornate domed skylight, gentlemen could be trimmed, shaved, and groomed with fragrant oils and greases and pale rum in an atmosphere that observers likened to the palace of an Eastern potentate.

The St. Nicholas seemed the very last word in luxury and sumptuous technology, yet it too was destined to be eclipsed, for in 1859 the Fifth Avenue Hotel opened at Fifth Avenue between 23rdand 24th streets, opposite Madison Square. A magnificent six-story building of brick faced with white marble, it had the breathtaking novelty of a “vertical screw railway,” the first passenger elevator installed in a hotel in the United States, a cumbersome affair powered by a stationary steam engine that – to the astonishment and wonder of all – could carry passengers to the upper floors. The hotel’s sober Italianate exterior masked a number of ground-floor public rooms that were richly furnished with gilt wood, crimson or green curtains, and costly carpets. Four hundred servants looked after the guests, who enjoyed private bathrooms and a fireplace in every room.

The Fifth Avenue Hotel, 1859.

The Fifth Avenue Hotel, 1859.An instant success, the hotel’s reading room was soon filled with gentlemen scanning newspapers, its dining room was jammed with diners, and certain ground-floor rooms became the preferred evening gathering place for Wall Street brokers and speculators after the stock exchange had closed. Hotel guests marveled at the jabbering throng trading tips and rumors, and marveled even more when the throng suddenly fell silent and parted, making way for the august and towering presence of Cornelius Vanderbilt, endearingly known in the 1860s as “Old Sixty Millions,” the richest man in the country, whose prospering railroad empire would earn him, by the 1870s, the name of “Old Eighty Millions.”

It should now be clear that each of the nineteenth-century palace hotels endeavored to outdo its predecessors in offering guests the latest in comfort, luxury, and technological advances, and that they were more than just sanctuaries where weary travelers could lay their weary but dazzled heads. They were also social centers, dining establishments, and even, on occasion, political headquarters where party members or their bosses met to make significant decisions regarding upcoming elections.

New York then and now has had too many hotels of every rank, from the palatial to the most modest and budget-prone, for me to list them here. So I’ll focus on those that have something special going for them, something that gives them an aura of distinction and prestige.

The Plaza Hotel at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, at the southeastern corner of Central Park and overlooking Grand Army Plaza, is a massive 20-story French Renaissance chateau-style edifice built in 1907 and a National Historic Landmark since 1986. Kings, presidents, ambassadors, celebrities, CEOs, and world travelers have stayed there over the years, not to mention the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and the Beatles on their first trip to the U.S. in February 1964. The sedate Plaza was dismayed to learn that the rooms reserved for “four English gentlemen” were meant for the Beatles, and were further dismayed by the screaming fans, mostly teen-age females, who, once the Beatles had arrived, created pandemonium outside. The foursome’s return to England inspired in the hotel a deep sigh of relief, and they were glad to let other hotels host the rock band on their later visits to the city.

The Plaza Hotel today.

The Plaza Hotel today.Yarl

What the Plaza was unhappy about in 1964. When I came to New York I often heard mention of “the Oak Room at the Plaza” and finally, at a friend’s prompting, visited this storied restaurant and adjoining bar, which had been serving men-only lunches since the hotel’s opening, until Betty Friedan and the National Organization for Women staged a protest there in 1969. The Oak Room was a grand, opulent, and elegant space frequented by the rich and famous, even though my friend and I managed to get in. I vaguely recall it as having a rather warm and woody atmosphere, supremely stylish and tasteful. So it’s dismaying to learn that it was closed in 2011, because the brunch parties staged there had become noisy and rowdy, annoying the Plaza’s long-term tenants. The participants in these orgies were said to indulge in drugs and loud music and Lady Gaga, while spraying each other with champagne. Lady Gaga’s flamboyant presence, wearing a wild blond wig, fishnet tights, and a dress made of honey-colored hair, would be enough to demolish instantly the aura of taste and elegance of any once legendary hostelry. A sad comedown, perhaps, for a once elegant locale, and a reminder that in a city like New York things can change, and not always for the better.

What the Plaza was unhappy about in 1964. When I came to New York I often heard mention of “the Oak Room at the Plaza” and finally, at a friend’s prompting, visited this storied restaurant and adjoining bar, which had been serving men-only lunches since the hotel’s opening, until Betty Friedan and the National Organization for Women staged a protest there in 1969. The Oak Room was a grand, opulent, and elegant space frequented by the rich and famous, even though my friend and I managed to get in. I vaguely recall it as having a rather warm and woody atmosphere, supremely stylish and tasteful. So it’s dismaying to learn that it was closed in 2011, because the brunch parties staged there had become noisy and rowdy, annoying the Plaza’s long-term tenants. The participants in these orgies were said to indulge in drugs and loud music and Lady Gaga, while spraying each other with champagne. Lady Gaga’s flamboyant presence, wearing a wild blond wig, fishnet tights, and a dress made of honey-colored hair, would be enough to demolish instantly the aura of taste and elegance of any once legendary hostelry. A sad comedown, perhaps, for a once elegant locale, and a reminder that in a city like New York things can change, and not always for the better. The Plaza has had a series of owners and is now owned by Sahara India Pariwar, an Indian conglomerate that is currently trying to sell it. Though today it claims to strike a balance between a storied past and a limitless future, one wonders if its glory days are long since past. But there’s hope: it claims to be the first hotel in the world to offer iPads for all guests, allowing them, with the touch of a screen, to order in-room meals, communicate with the Concierge, request wake-up calls, and check airline schedules and print boarding passes. But it can’t get them into the legendary Oak Room, which has ceased to exist.

Only one other New York hotel enjoys the status of National Historic Landmark: the looming 47-story Waldorf Astoria, the second of that name, occupying the entire block between Lexington and Park avenues and between 49th and 50th streets, a massive limestone structure in what is described as “restrained Art Deco style” that opened in 1931. With twin towers topped by bronze-clad cupolas rising above the twenty floors of the main building, its great mass has a majesty all its own; it overwhelms. The 1413 guest rooms include 181 in the Waldorf Towers, a hotel within a hotel occupying floors 27 through 42, and of those 181 there are 121 luxury suites often named for eminent guests who once resided there: the Presidential Suite, the Elizabeth Taylor Suite, etc. Those guests have included ex-president Herbert Hoover, who lived there for over 30 years, Cole Porter, Douglas MacArthur, Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, society hostess and party-giver Elsa Maxwell (who got a rent-free suite, in hopes she would lure the affluent), and Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano.

The Waldorf Astoria as seen from the north, with St. Bartholomew's Church.

The Waldorf Astoria as seen from the north, with St. Bartholomew's Church.Reading Tom

Wait a minute – Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano, two notorious mobsters, at the Waldorf? Treading the same corridors as an ex-president and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor? Is this conceivable? Yes, it is. Thanks to prohibition and America’s craving for liquor, Bugsy Siegel by 1927, at the tender age of 21, was awash in cash and, to flaunt it, bought an apartment at the Waldorf. We’ll assume that management didn’t know who they were dealing with, and of course his money was good. The same goes for Charles “Lucky” Luciano, who in the early 1930s lived in room 39D in the luxurious Waldorf Towers under the name Charles Ross, and looked very much the affluent businessman, wearing custom-made suits and riding about in a chauffeur-driven limousine. He held meetings of the mob in his suite and was even photographed there with some of his cohorts. In 1936, when U.S. Attorney Thomas Dewey tried him for operating a massive prostitution ring, the testimony of Waldorf employees about him and his associates at the Waldorf was devastating to his defense and helped bring about his conviction. (More of this in a forthcoming post.) And in his later years yet another gangster, Frank Costello, got his haircut and manicure regularly at the hotel’s barber shop.

Another eminent guest was General Douglas MacArthur who, returning to this country in 1951, was lodged with his second wife and their only child in a suite in the Waldorf Towers. So it was from this exclusive address that his son Arthur MacArthur issued daily to attend classes at Columbia College, where he was in the second-year French class that I was teaching in 1957. A sensitive 19-year-old with an excellent accent in French that must have been acquired through private tutoring, he sat apart from the other male students. Remembering photos of him at a very young age with his mother and his Chinese amah in Australia, where they went following their escape with the General from the besieged Philippines in 1942, I sensed that, through no fault of his own, he had been too much in the company of women and needed more contact with boys his own age. His parents resided at the Waldorf from 1952 until 1964, the year of the General’s death, and his mother continued there until her death.

(A brief digression regarding Arthur MacArthur: With his father in charge of the war in the South Pacific, at age 4 his photo had appeared on the cover of the Life magazine of August 3, 1942, and prior to that he had been photographed repeatedly with his father. After the General’s death in 1964 he moved out of the Waldorf to another part of Manhattan and changed his name, so as to creep out from under the burden of an illustrious heritage. His father had wanted him to go to West Point, but he was drawn to music, literature, the arts, and theater. For decades he simply vanished from sight, probably glad to escape the publicity that, as a son and grandson of renowned generals, had so oppressed him and kept him from living a life of his own. Then, just last year, it was reported that Arthur MacArthur, who would now be 76, was one of four reclusive tenants in rent-controlled apartments in the Mayflower Hotel on Central Park West who were given lavish sums by a developer to move out. Arthur MacArthur is said to be living now in Greenwich Village, which, if true, makes him a neighbor of mine. I wish him well in his anonymity.)

Lavish dinners, business conferences, and fund-raising galas have been held at the Waldorf. Prominent among them was the annual April in Paris Ball (later moved to October), which, in the words of an organizer, catered to “very, very high-class people” and raffled off prizes like a chinchilla coat, a Ford Thunderbird car, 25 cases of expensive French wines, a pedigree poodle, and other goodies, with earnings going to French and American charities. Unique among hotels, it also became involved in world affairs, hosting international conferences and secret meetings of statesmen and other figures of prominence, and receiving controversial foreign leaders requiring the highest level of security.

Society hostess Elsa Maxwell whispering to Marilyn Monroe at the April in Paris Ball,

Society hostess Elsa Maxwell whispering to Marilyn Monroe at the April in Paris Ball, 1957. There's a story here; it will be told in a future post. A 1949 conference, held at the Waldorf to discuss the emerging the Cold War in hopes of promoting peace, was attended by Soviet Foreign Minister Andrey Vyshinsky, composer Dmitri Shostakovich, Albert Einstein, and others, but was climaxed by Shostakovich’s outburst in front of 800 people asserting that “a small clique of hatemongers are preparing world public opinion for the transition from cold war to outright aggression.” Anti-Stalinist activists picketed outside, flaunting signs saying NIET TOVARICH! (no comrade!) and SHOSTAKOVICH! JUMP THRU THE WINDOW, while prominent American literary figures denounced Stalinism inside. Needless to say, the Cold War continued unabated.

An international event of somewhat less significance was the stay there of the British rock band The Who in 1968, when a dispute with the hotel staff led to their being denied access to their room. What prompted the Waldorf to receive a band known for rowdy behavior and trashing hotel rooms is unclear, but the band’s response was forthright and immediate: they blew the locked door off its hinges with a cherry bomb and retrieved their luggage, following which they were banned from the hotel for life – a ban later revoked when The Who were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in a ceremony held at the Waldorf in 1990.

Though not a “very high-class people,” back in my freelance editing days I used to obtrude my plebeian presence on this storied edifice. Coming back from a publisher on Third Avenue, I would enter the Waldorf on Lexington Avenue and walk the length of the arcade, lined with pricey boutiques, that leads to the elegant Park Avenue lobby. There I would usually linger for a few moments, enjoying the music from the plucked strings of a harp on a mezzanine above. Most of the people traversing the lobby seemed totally unaware of the music and hurried on, but I and a few others savored it, grateful for the surprising presence of the woman harpist who sent these gentle sounds wafting down to us below. A harpist lodged above a hotel lobby: once again, the Waldorf was unique.

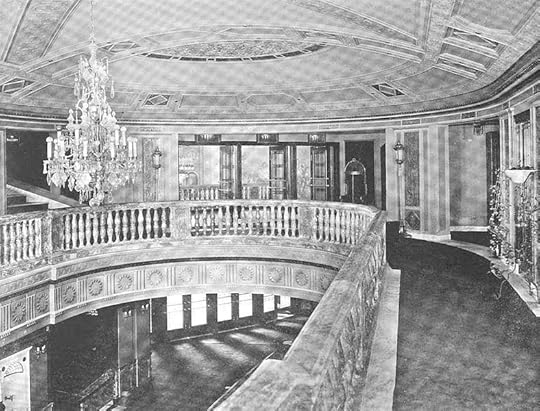

The Waldorf lobby. All this and harp music, too.

The Waldorf lobby. All this and harp music, too.Alan Light

And who owns the Waldorf today? From 1972 on, Conrad Hilton, but as of October 2014, the Anbang Insurance Group of China, who acquired it for $1.95 billion, the highest price ever paid for a hotel. So the legendary Waldorf Astoria, like the Plaza, is foreign-owned today.

Note on J.P. Morgan: Once again I must come to the defense of J.P. Morgan Chase, my beloved candy-dispensing bank, whom the government just won’t let alone. Targeted by an anti-trust lawsuit accusing 12 major banks of rigging prices in the foreign-exchange market, it has agreed to pay $99.5 million to settle its portion of the suit. And this on top of a $1 billion settlement to resolve claims by U.S. and European regulators last November! To top it off, the New York Times article reporting the latest settlement reads as follows:

JPMorganTo Pay Out$99 MillionOver Graft

Not only is this unsporting of the Times, to hit a man when he’s down, but referring to the matter as “graft” is worthy of the lowest, meanest, nastiest, most sensationalist tabloid. Let the Newspaper of Record take note: It wasn’t graft, it was profit enhancement.

Notes on Al Sharpton and friends:

1. A viewer of this blog informs me that Al Sharpton may have had surgery to reduce his girth. He denies it, but some medical sources confirm it. (See last week’s post #164 on Al Sharpton.)

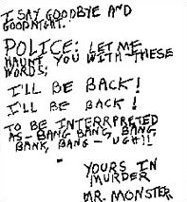

2. Another viewer of this blog informs me that, back during the Tawana Brawley controversy, he heard attorneys Alton H. Maddox and C. Vernon Mason tell a WNYC interviewer that Attorney Steven Pagones was in the habit of taking out photos of Tawana and “massabatin.” At first he wondered if he heard this remark right, but when the station did an end-of-the-year roundup of the big stories of the year, he heard the remark repeated. Both attorneys, he further informs me, have since been disbarred.

Coming soon: More on great hotels: the hotel that hosted the “Vicious Circle”; the hotel whose manager terrorized the staff; budget hotels; the super modern hotel that to my eye looks clunky; and the hotel where you shouldn’t attempt suicide, and why. Also: How did Franklin Delano Roosevelt get to his Waldorf suite without being seen by the public? And what is the weirdest request ever made by a guest at the Waldorf Towers, and what did the Waldorf do about it?

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on February 08, 2015 04:32

February 1, 2015

164. Al Sharpton: Rabble Rouser or Champion of His People?

New Yorkers have to face the dismaying fact that their mayor, Bill de Blasio, and their police force are at loggerheads. At the recent funerals of two policemen shot in their patrol car and killed by a black assailant who then committed suicide, many of New York’s Finest turned their backs on the Mayor when he spoke. And the president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association asserted at a press conference that the Mayor, having incited violence on the streets in the guise of protest over the recent police killing of an unarmed black man on Staten Island, had blood on his hands. The grievances of New York’s Finest against the Mayor are many, among them his warning to his biracial son to be careful during police encounters. But what they especially resent are his public appearances with the Reverend Al Sharpton, who is, and for many years has been, one of the most controversial public figures in the city. So who is Al Sharpton?

Al Sharpton is a Brooklyn-born African-American civil rights activist who has led many protest marches and demonstrations challenging the white power structure on behalf of African Americans. He is also a Baptist minister, a talk show host, and a White House adviser consulted by President Barack Obama, who has called him “the voice of the voiceless and a champion of the downtrodden.” But he has also been called an inflammatory black radical, a demagogue, a rabble rouser, a fraud, and much more, and his career has been marked by controversy.

Al Sharpton (center) leading a march in Bensonhurst in 1989.

Al Sharpton (center) leading a march in Bensonhurst in 1989.christian razukas

It was his eagerness to lead protest marches and demonstrations on behalf of African Americans, often with shouts of “No justice, no peace,” that first vaulted him into fame ... or notoriety. Indeed, what controversy involving race and racism in this city has he not been involved in, often in a track suit, obviously overweight, his dark hair down to his shoulders, with a thin black mustache curled snakelike over his upper lip. Examples of his activism include:

· Marches protesting the outcome of the trial of Bernhard Goetz, a white man who shot four young African Americans on a subway train in 1984 – a case that electrified and divided the crime-ridden city. Goetz was cleared of all charges except carrying an unlicensed firearm. A federal investigation concluded that the shooting was the result of an attempted robbery, not racism.· A march of 1200 demonstrators through Howard Beach, a mostly white neighborhood in Queens, following the assault there in 1986 of three African Americans by a mob of white men, resulting in the death of one of the victims who, when fleeing, was hit by a passing motorist. During the march the white residents screamed racial insults at the black marchers.· Marches through Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, to protest the attack on four African-American teenagers by a mob of white Italian-American youths in 1989, during which one of those attacked was shot and killed. Residents shouted “Niggers go home!” at the marching protesters and would have assaulted them, had the police not intervened. In 1991 the attackers received light sentences, and when Sharpton prepared to lead another protest march, a neighborhood resident stabbed him in the chest. Sharpton recovered and asked the judge for leniency when his assailant was sentenced, but sued the city, alleging that the police had failed to protect him, and got a settlement of $200,000.· A march in 1991 through Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where West Indians and African Americans live in perilous proximity with Hasidic Jews. Four days of race riots erupted following the accidental killing of a seven-year-old Guyanese boy, when a car driven by a Jew was struck by another vehicle and forced onto the sidewalk. Black youths looted stores and beat Jews in the street, and a visiting Jewish student from Australia was stabbed and killed, while rioters chanted “Kill the Jew!” and “Get the Jews out!” Sharpton’s march, on the third day of riots, had a distinctly anti-Semitic tone.· A 1999 protest over the death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed immigrant from Guinea shot to death by police officers who thought he was drawing a gun. Diallo’s family later got $3 million in a wrongful death suit filed against the city.· Peaceful protests in 2008 when three detectives were found not guilty in the shooting of Sean Bell in a hail of 50 bullets on the morning of his wedding in 2006. Bell had been accosted by detectives outside a strip club in Queens, and was allegedly trying to flee in his car when he was shot. The protests blocked traffic at bridges and tunnels giving access to the city, and Sharpton and 200 others were arrested.· Peaceful protests on Staten Island, the city’s whitest borough, in July and August 2014, following the death of Eric Garner when an officer put him in a chokehold, a strangling hold that is prohibited. Garner was evidently selling illegal cigarettes and may have resisted arrest. Captured on video, his repeated cry of “I can’t breathe!” became a rallying cry of protesters. His death was ruled a homicide, but on December 3, 2014, a grand jury decided not to indict the officer who had administered the chokehold, prompting protests nationwide. When two police officers were shot and killed in their patrol car on December 20, the assailant, who then committed suicide, was motivated by two recent police shootings: Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner on Staten Island.

Protesters at a rally called by Sharpton in August 2014 to protest the death of Eric Garner and others.

Protesters at a rally called by Sharpton in August 2014 to protest the death of Eric Garner and others.Thomas Altfather Good And these are only some of the protests Al Sharpton has been involved in. Former mayor Ed Koch, once a foe of Sharpton’s, has said that Sharpton deserves the respect he enjoys among African Americans: “He is willing to go to jail for them, and he is there when they need him.” So why is he so controversial? Recently, when I mentioned Sharpton by name to two friends with long memories, both immediately said, “Tawana Brawley.” Yes, Sharpton’s name is irrevocably linked to that of Tawana Brawley, and this explains much of the feeling against him. So who is – or was – Tawana Brawley?

Tawana Brawley at a press conference. Tawana Brawley was a 15-year-old African American who had been missing from her home in Wappinger Falls, New York, for four days when, on November 28, 1987, she was found lying in a garbage bag and smeared with feces, her clothing torn and burned, and with “KKK,” “nigger,” and “bitch” written on her body with charcoal. Interrogated at the hospital, she was verbally uncommunicative, but through gestures and writing claimed that she had been assaulted and raped by three white men, at least one of them a police officer. She gave no names or descriptions of her attackers, and forensic tests found no evidence of a sexual assault, nor was there any evidence of exposure to elements such as would have occurred in a victim held for several days in the woods.

Tawana Brawley at a press conference. Tawana Brawley was a 15-year-old African American who had been missing from her home in Wappinger Falls, New York, for four days when, on November 28, 1987, she was found lying in a garbage bag and smeared with feces, her clothing torn and burned, and with “KKK,” “nigger,” and “bitch” written on her body with charcoal. Interrogated at the hospital, she was verbally uncommunicative, but through gestures and writing claimed that she had been assaulted and raped by three white men, at least one of them a police officer. She gave no names or descriptions of her attackers, and forensic tests found no evidence of a sexual assault, nor was there any evidence of exposure to elements such as would have occurred in a victim held for several days in the woods.Tawana Brawley’s story captured headlines nationwide and aroused great shock and sympathy, and money was raised for a legal fund. Al Sharpton and black attorneys Alton H. Maddox and C. Vernon Mason joined forces to champion her cause, which became a media sensation. The trio of activists claimed that officials all the way up to the government in Albany were trying to protect the white attackers, and named Steven Pagones, an Assistant District Attorney in Dutchess County, as one of the rapists.

The case went to a grand jury that heard 180 witnesses and saw 250 exhibits, and then on October 6, 1988, released a 170-page report noting many discrepancies in her story and citing “overwhelming evidence” that Brawley had not been abducted, assaulted, and raped, and that the allegations against Pagones were false. But why would she have concocted such a story? Based on the testimony of witnesses, she might have done it to avoid violent punishment from her mother and stepfather, who had abused her in the past.

Steven Pagones sued Brawley’s three advisers for defamation of character and in 1998 was awarded $345,000. He also sued Brawley, who did not appear at the trial and was ordered to pay Pagones $186,000. Just where she was supposed to get such a sum wasn’t clear, but in 2013 – yes, the case’s aftermath lasted that long -- a court ordered her wages garnished. Sharpton failed to pay the sum required, claiming he lacked the funds, but his supporters paid it in 2001.

Sharpton never recanted, and to this day Brawley, her mother, and her stepfather insist that the attack did indeed take place. Brawley herself now lives in Virginia under an assumed name and works there as a nurse. White people doubted her story from the outset, but there are still blacks who believe it. My own take on the affair is this: a rebellious but frightened teenager, having been absent from home for four days and fearing more abuse at home, invented a wild story to bring her sympathy, having no idea what the consequences might be; having lied, she had to stick to her lies through thick and thin. As for Sharpton, his vigorous defense of her shows a grievous lack of judgment, one that his many critics will never fail to cite.

A curious twist in Sharpton’s story came to light when he admitted to having informed for the government in the 1980s, so as to stem the flow of crack cocaine into black neighborhoods. But he denied having ever informed on black civil rights leaders. More detailed reports have since emerged of Sharpton’s working as a paid informant for the FBI, helping the government bring charges against the mobsters flooding the ghettos with drugs.

In 2009 Sharpton became an honorary member of Phi Beta Sigma, an African American Greek-letter fraternity whose mission is to promote brotherhood, scholarship, and service. Members have included foreign heads of state, scientists, musicians, athletes, and activists, a feisty mix of notables ranging from George Washington Carver, Harry Belafonte, and ex-President Bill Clinton to Black Panther Party founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale.