Clifford Browder's Blog, page 38

November 22, 2015

207. The Rich Today

A previous post (#205) looked at the rich of nineteenth-century New York, most of whom earned their fortune themselves and provided some useful product or service to society. So what about the rich of today? I know of no compilation of the richest New Yorkers comparable to Moses Beach’s tabulation of 1845, but Forbes magazine’s annual list of the 400 richest Americans is a good place to start. Among the top 100 names listed are 16 New Yorkers, with the source of their income as follows:

Investments, 4Hedge funds, 2Real estate, 2Media, 2Private equity, 1Leveraged buyouts, 1Financial services and news, 1Cosmetics, 1Luxury clothing and housewares, 1Television and real estate, 1

Since investments, hedge funds, private equity, and leveraged buyouts can be combined under the term “finance,” it’s obvious that finance, for a total of 8 (or maybe 8½, including financial services and news), is tops, and “finance” of course means Wall Street. Real estate is second with 2, or maybe 2½, if one adds the “real estate” half of “television and real estate.” Tying real estate with 2, or surpassing it with 2½, if the television part of “television and real estate” is included, is media. Finally come luxury clothing and cosmetics, which can be lumped together as “retail.” What is conspicuous by its absence is technology, since that is more of a West Coast phenomenon.

Finance and real estate were biggies in the nineteenth century also, but the Wall Street of today is not the Wall Street of then, for hedge funds and leveraged buyouts are recent creations, and very different creatures indeed. How many of us even know what a leveraged buyout is, or what a hedge fund or private equity firm does? In the nineteenth century the public was surely baffled by short sales, puts and calls, and straddles, but those devices never by themselves precipitated a worldwide financial crisis, which is more than can be said for the financial gimmicks of today. How reassuring it is to find cosmetics and luxury clothing included in the first 100 – real stuff that you can see and smell and touch. Even if you can’t afford it, you can understand such products and wish their creators well.

Who is the richest New Yorker? Michael Bloomberg, whose firm Bloomberg LP is the “financial services and news” provider listed above. A business magnate credited by Forbes with $38.6 billion, he is also the eighth richest man in America. And oh yes, he was the 108th mayor of our fair city, serving no less than three consecutive terms. A successful business magnate, independent politician, and philanthropist, he is not to be dismissed lightly. By serving as mayor he continued a tradition of New York merchants who in the first half of the nineteenth century – before the advent of the professional politician and the dominance of Tammany Hall -- took two years or more out of their business career to govern, or try to govern, the unruly city of New York. For them, it was a matter of public service, even though their heart was in their business.

For Michael Bloomberg, a phenomenally successful businessman, politics was probably the only place to go for the thrill of further achievement. The results? Both negatives and positives. But the negatives – a stop-and-frisk policy that abused minority communities, homelessness, and cozy relations with banks and real estate – were surpassed by the positives: restrictions on smoking in public, pedestrian plazas, 850 more acres of parkland, 470 miles of bike lanes, and a safer, cleaner city. Not a bad public record for the city’s biggest moneybags, far surpassing that of Cornelius “Old Eighty Millions” Vanderbilt, the richest New Yorker in the 1870s. And I haven’t even looked at Bloomberg Philanthropies Foundation and what it’s up to. Nor have I mentioned his living with a lady friend, which bothers New Yorkers not a bit. His appearance? Dignified, mayoral, but with a winsome smile.

Hizzoner.

Hizzoner.David Shankbone

The next richest New Yorker, according to Forbes, is Carl Icahn, a Far Rockaway native and Princeton graduate turned hedge fund manager and activist shareholder whose wealth is pegged at $20.5 billion. His involvement in risk arbitrage and options trading is enough to baffle the uninitiated (of which I am one), and his reputation as a ruthless corporate raider is not likely to endear him to multitudes. In 1985 he staged a hostile takeover of TWA, then sold TWA’s assets to repay the debt he used to acquire the company – a procedure known as asset stripping. Then in 1988 he took TWA private, reaping a profit of $469 million, while leaving the company saddled with $540 million in debt. So if Bloomberg is the big fish in the pond, Icahn is a shark. Labeled a financial parasite by some, he insists that he is always acting in the company’s best interest by ousting incompetent management; also he tends to hold stock for over three years, which makes him something of an investor. Hostile takeovers, proxy fights, stock buybacks, chairman of this and acquirer of that – no layman could follow his career or grasp his motivation, but it all explains why he has the second biggest New York fortune. A sober-looking, well-dressed business type whose features have graced the cover of Forbes and Time, he manages to work in some philanthropy, too.

The third richest New Yorker, with $12.5 billion, is investor and philanthropist Ronald Perelman, whom I confess I had not heard of, but whose photos show a chubby, balding fellow, rather jolly-looking with a hearty smile. Forbes describes the source of his wealth as “leveraged buyouts,” so I’m suspicious already. His modus operandi is to buy a company, strip it of superfluous divisions so as to reduce debt and generate profit, then focus on the company’s core business and either sell it or hang on to it for its cash flow. So is all this good or bad? I haven’t the slightest idea, but I gather that Perelman, like Icahn, is a corporate raider, which makes him shark no. 2. One of his favorite operations is greenmail: he buys a big chunk of a company’s stock, then threatens a takeover unless they buy his stock back at a much higher price; if they do, he reaps a phenomenal profit. The mere acquisition of shares by such a raider precipitates panic in management and a buying frenzy in the public. But like Icahn, he finds time for philanthropy, and for five marriages as well. He does get around.

Shark no. 2. A great smile.

Shark no. 2. A great smile.David Shankbone

The fourth richest New Yorker is none other than Rupert Murdoch, with $11.6 billion made in media. We’ve all heard of the gentleman, and “media” barely suggest his amazing career. Australian-born, he first acquired newspapers in Australia and New Zealand, then expanded his acquisitive talents to Great Britain, and for further conquests moved to New York City in 1974, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1985 for the soundest of reasons: to be able to expand into U.S. television, which can’t be owned by foreigners. Expanding comes naturally to him; by 2000 his News Corporation owned over 800 companies in some 50 countries, including such U.S. gems as Twentieth Century Fox, HarperCollins (a publisher I used to work for), and The Wall Street Journal. Indeed, one wonders what he doesn’t own.

Mr. Murdoch and wife no. 3, before divorce proceedings.

Mr. Murdoch and wife no. 3, before divorce proceedings.David Shankbone Not that all is well in the Murdoch empire, for in 2011 his newspapers were accused of hacking the phones of celebrities, including the British royal family, no-no’s that provoked criminal investigations on both sides of the pond. Photos reveal a smiling, wrinkled gentleman of 84 with a very receding hairline and glasses, which hasn’t prevented him from going through three wives, the last of whom (if “last” there is) he is divorcing. His urgent need to expand his media empire, like the force driving corporate raiders and hedge fund honchos, puzzles and intrigues me; I would like to know what makes this man tick, and wonder if he himself knows. As for hedge fund honchos, perhaps relevant is the fact they make much more money than CEO’s of corporations – annually, sometimes a billion or more.

Compared to these other richies, not to mention Donald Trump – no. 121 on the Forbes list, with a paltry $4.5 billion – Michael Bloomberg comes off looking good. He isn’t a pirate or an egomaniac, gave us bike lanes and greenery, made it possible for us to stroll in Times Square, and cleansed our indoor public spaces of nicotine. Not bad, Mike, not bad.

So what do these folks do in their spare time (if they have any)? For one thing, they give. The New York Times ran a recent article on The Big Ask, on philanthropies hoping to nudge fat cats toward a Big Give. New York is full of big-name cultural institutions that gobble up big money so as to realize their big dreams, and big donors are in their sites. In 2008 Leonard Lauder, the cosmetics magnate, gave $131 million to the Whitney Museum of American Art – the biggest gift the Whitney has ever received. And in 2013 he gave the Metropolitan Museum of Art 79 Cubist works, a collection of Picassos, Braques, and Légers valued at more than $1 billion, to be housed in a projected new wing for contemporary art. Lauder is seen as embodying an old money model of largesse, concentrating on one or two institutions and in so doing making a big splash.

Contrasting with Lauder is Bruce Kovner, a hedge fund manager who in 2012 gave $20 million to the Juilliard School of Music for its early music program. Never heard of him? That’s the way he likes it. He shuns publicity, doesn’t want his name on a building, avoids interviews and black-tie fundraising galas that would love to feature him and lure more donors. A bit of a surprise: a hedge fund manager in love with music and who believes that “the arts … are what make humans what we are.”

But today’s moneybags don’t give just to the arts, far from it; with their eye on the 2016 election, they give big money to the candidates of their choice. Mostly Republicans, of course. According to a lead article in a recent New York Times, only 158 U.S. families have given almost half the cash -- $176 million – raised to date for the election. So who are these donors? White, wealthy, older males clustered in a handful of communities throughout the nation, the biggest of these being New York. So right away I smell hedge funds, leveraged buyouts, private equity. And theTimes confirms my hunch, for these donors aren’t from old big money, haven’t inherited their wealth; they’re newbies who launched their own businesses, took risks, and reaped huge gains, prominent among them the hedge fund managers of New York. And they support Republican wannabes who promise lower taxes, fewer regulations, stingier entitlements. Not that it’s easy to sniff these donors out. They hide behind business addresses, post office boxes, and limited liability corporations and trusts.

One hedge fund manager named in the Times article is Robert Mercer, whose Renaissance Technologies, founded in 1982, is one of the world’s biggest hedge funds, with some $27 billion in assets. Closed to outsiders and open only to employees and their families (minimum investment $1 million), Renaissance is said to be run by and for scientists, with an emphasis on quantitative finance research done by mathematicians, computer scientists, physicists, astrophysicists, and statisticians; Wall Street experience is frowned on. Mercer loves computers, calls himself “simply a computer programmer,” uses computers to guide his investing and avoid the herd mentality of Wall Street. His staff amass vast amounts of data and use secret computer-based models to predict prices.

Despite the fund’s obsessive secrecy, one example of their novel approach to investing has come to light: they obtained data on clouds indicating that markets are less likely to rise on cloudy days, which was then confirmed by more data from Paris, Milan, Tokyo, Sao Paulo, and New York. With even the weather behind them, no wonder they are billionaires and the rest of us are poor. So if you must invest, check out the cloud patterns first.

As for donating, the Washington Post has called Mercer one of the ten most influential billionaires in politics, labeling him a “Tea Party conservative.” Well, he’s got a lot to protect, and the IRS has been sniffing around his hedge fund for years. His money-backed choice for the White House: Ted Cruz.

Mercer’s firm is based on Long Island, but its administrative offices are in Manhattan. He lives with his wife (believe it or not, he’s had only one) in Head of the Harbor, New York, a quiet little village in Suffolk County on the North Shore of Long Island. I confess that until now I’d never heard of Robert Mercer or Head of the Harbor, New York. As to how he commutes from there to Manhattan – private jet, limousine, whatever – I haven’t a clue, but I’ll bet he does it, however discreetly, in style.

The nerd of nerds, Mercer is reclusive, avoids photographers, rarely speaks in public. Described as “an icy cold poker player,” he appears in rare photos of him as a clean-shaven older man with thinning hair, appropriately tense when playing poker at a tournament. All that clout, and most of us have never heard of him. Which says a lot about the rich of today; they aren’t all attention-grabbing fiends like The Donald.

This last Halloween hedge fund billionaires left their mark on Manhattan, bedecking their townhouses with goblins, crones, witches, zombies, skeletons, ghouls, ghosts, spiders, and bats leering from balconies, peering through railings, or guarding entrances. Outside the East 74th Street residence of Marc Lasry, a cofounder of Avenue Capital, bloodied life-size dummies dangled from a balcony, while a chaste neo-classical entrance on East 67th Street featured an effigy of a two-headed girl standing in a multitude of rats. But it could have been worse: a year before, the façade of hedge-fund billionaire Philip Falcone’s residence on East 67thStreet, a street that seems to lure spooks, was graced with a crone cradling a dead infant, while inside a hearse parked at the curb the Grim Reaper was seen beheading a corpse – a display spooky enough to provoke protests by the neighbors. All of which shows where some of the millions – a tiny portion -- reaped by fat cats goes.

The rich are served by an army of maids, nannies, janitors, doormen, chauffeurs, shop clerks, and the staff of elite restaurants, but not all of the army is enchanted with those they serve. Another Times article (the Times seems to feast on stories of the rich) tells of the service of a young captain of waiters in a Michelin three-star restaurant. When the doors open and the first guests are seated at 5:31 p.m., he scans a digital dossier listing every guest’s water preference, food allergies, likes and dislikes, and whether or not they spend big on wine. The captain greets the table, asks for water preferences, signals with his hand behind his back to an assistant: wiggling fingers means bubbles; a slashing motion, still; a twist of the fist, ice water. Minutes later the captain takes orders, memorizes each one, then passes them on to the server.

They also serve who only stand and wait.

They also serve who only stand and wait.Michael Plutchok

“Make it nice” says a sign in the kitchen, reminding employees that everything in the restaurant, from the placement of candles to the part in your hair, must seem perfect. Captains, servers, and sommeliers know they are playing a part, and they do it with a touch of irony. They project warmth while keeping emotional distance: the thrill of the con. The guests want to believe that all is perfect, and the staff are trained to sustain the illusion. A smudged glass, a fingerprint on a fork would shatter the illusion, must not be allowed to happen. The guests eat ravenously, attempt sex in a restroom; one woman tries to leave her baby at the coat check counter, and grown men at the bar chant, “We are the one percent.”

When a regular has a stroke and topples to the floor, the staff are visibly shaken, but the manager quickly pushes a champagne cart in front of the body on the floor, hoping to hide it, and turns the music up. Ten minutes later the paramedics arrive to cart the victim off, and the charade resumes. Finally, after months of “make it nice,” the young captain felt empty and tired, and quit the job to become a graduate student at the New School for Social Research. The superrich would have to do without his service, and he could certainly do without them. They look best from a distance.

It must mean something when the ultra rich get ribbed in advertising. The New York Lottery has launched a humorous ad campaign showing richies wasting their money in oddball ways. One TV commercial shows a man soaking in a bathtub of pinot noir; when his butler lets a bit of cork fall in the tub, he gets angry. The viewer, suggests the ad, would make a much better rich person than this fool in a tub, and Lotto is the way to do it. Advertisers know you can’t make fun of the poor, but today the wealthy are fair game. So the Lottery satirizes the truly rich so as to encourage the not-so-rich to get a little less rich.

The year 2015 has not been kind to the rich; their investments have languished. “I’ve failed to protect your capital,” one hedge fund manager, Larry Robbins of Glenview Capital Management, told his investors, acknowledging a 15% loss of their capital this year to date. But this hasn’t kept him from buying the top four floors of the Charles condominium, a soaring 31-story glass box at 1355 First Avenue between 72nd and 73rd Streets; the price of his multi-storied penthouse, its huge floor-to-ceiling windows offering sweeping views of the Hudson and East Rivers, is $37.9 million, a record for that part of Manhattan. In fairness to Mr. Robbins, it should be noted that the market has not been kind to most investors this year, though not all are down 15%. And his purchase of a luxury penthouse, a mere pied-à-terre, since his primary residence is a sprawling mansion on a four-acre estate in Alpine, New Jersey, shows that the New York real estate market is still ablaze and booming. On this happy note, I’ll end; the rich have worn me out.

The Charles. Want to live there? Sorry, the top four floors are taken.

The Charles. Want to live there? Sorry, the top four floors are taken.Paris: A sign in a ground-floor window of a building on my street: J’adore Paris.

The book: The second and final Goodreads giveaway for the collection of posts from this blog has ended; 598 people signed up, of whom one will receive a free copy. Both a print version and an e-book are available online. See Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc.

Coming soon: The inevitable and inescapable Donald Trump, who for better and for worse is New York to the bone, and then some.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on November 22, 2015 04:42

November 15, 2015

206. Tiffany

A large, darkened room with 132 Tiffany lamps on display, each having its own space, each illuminated and casting a soft glow. Reddish or brown bronze bases topped by polychrome shades of glass, mosaics of small pieces of luminous red, yellow, blue, green, purple, and pink: miracles of glass, of color, of light. Looking closely at one lamp, one sees a ring of dragonflies with red bodies, their yellow wings extended horizontally, and above them on the shade, a band of green and blue that could be the water they are darting over, and at the very top of the shade, a patch of blue that might be sky. Another lamp suggests purple wisteria drooping languorously, and another, the wings of a peacock with eyespots of red and green. Other shades are geometrical, with triangles and squares and ovals of many colors, still others show daffodils or peonies or poppies, or spiders with webs, or butterflies: nature enhanced, transformed. This room is magic; to leave it is jolting, dispiriting, sad.

Cliff

CliffThe room just described exists only in my imagination, but it or something like it will exist on the fourth floor of the New York Historical Society in 2017, when their new installation is completed and opens to the public. In the meantime I have to settle for whatever my imagination can cook up.

A wisteria lamp.

A wisteria lamp.Fopseh

A dragonfly lamp, plus pigeons.

A dragonfly lamp, plus pigeons.Rickjpelleg

“Tiffany”: the name suggests luxury, quality, style. There are no Tiffany lamps in the West Village apartment shared by me and my partner Bob, but we do possess two genuine Tiffany products. One is a sterling silver letter opener that Bob once gave his mother and then repossessed after her death; he uses it daily to open mail.

Our other Tiffany possession is a small vase that was given to Bob by a friend who inherited it from his mother. Round-shaped with a narrow mouth, it is two and a half inches in diameter and serves no practical purpose, nor should it, given its exquisite fragility. To my eye it is silverish, and to Bob’s eye golden, but in either case it emits a soft luster to be marveled at. Bob keeps it on top of his dresser in a little glass case that he bought specifically to shelter it, and there it sits, asking only to be looked at and admired.

Our friend John, while serving as co-executor of the estate of a mutual friend, came into possession of a genuine Tiffany lamp lacking a few small pieces of glass. He and his fellow executor spent $2800 to have it repaired, so they could sell it through Christie’s. Christie’s estimated its value at $20,000 to $30,000, but at auction it drew not a single bidder. Undismayed, Christie’s decided to hold off for six months and offer it again. At the second auction it was sold for $18,000; after Christie’s fee and other expenses were subtracted, the two executors netted $12,000, which as heirs they split evenly. All of which shows the value of genuine Tiffany lamps today, for which there is an ongoing market. Because Tiffany’s, to put it bluntly, has class.

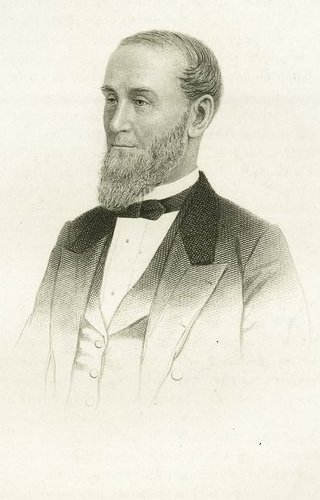

It also has a long and interesting history. Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder, and his partner John P. Young opened the first Tiffany’s as a “stationary and fancy goods emporium” in 1837, with the intention of selling not to the moneyed few, but to the masses. Located at 259 Broadway, opposite City Hall Park, it netted all of $4.98 on the first day, which hardly suggested success. But the partners persevered, offering umbrellas, Chinese carvings, portfolio cases, fans, gloves, and stationery, and on New Year’s Eve, the peak of the holiday shopping season, they rang up sales of $679.

Charles Lewis Tiffany in his store, circa 1887.

Charles Lewis Tiffany in his store, circa 1887.In the years that followed, Charles Lewis Tiffany roamed the docks for unusual imports, bargained with sea captains for exotic items, and acquired a reputation for selling such curiosities as dog whips, Venetian-glass writing implements, Native American artifacts, Chinese novelties, “seegar” boxes, and “ne plus ultras” (garters).

Jewelry was not at first a significant item, but that changed in 1848, when aristocrats fleeing the revolution in Paris dumped their diamonds on the market, and Tiffany’s partner Young, just arriving in the city, snapped them up. Arrested as a royalist conspirator, Young talked his way out of it and survived to forward his trove to Tiffany, who publicized his partner’s adventures; ironically, it was Tiffany himself whom the press then christened the “King of Diamonds.”

In 1850 Tiffany opened a Paris branch, thus acquiring access to European jewelry markets that no American competitor could match. Years later Charles Lewis Tiffany would acknowledge that the firm had also acquired the girdle of diamonds of Marie Antoinette, which had disappeared when the 1848 revolutionaries looted the Tuileries palace. Breaking the girdle up into pieces to sell, Tiffany claimed that its authenticity could not be proven, and thus avoided any awkward revelations about how the item had migrated from the royal vaults of the Tuileries into his own welcoming palms, a mystery that remains unsolved today.

His reputation for scrupulosity, his ready cash, and his swift judgment made Tiffany the city’s leading dealer in jewelry and Oriental pearls. Always on the lookout for rarities, in 1856 he bought a perfect pink pearl from a New Jersey farmer who had found it in his dinner mussels. He promptly sold it to the Empress Eugénie of France, news of which precipitated a mass combing of the waterways of America in hopes of finding another huge triple p: perfect pink pearl. (None was found.) And when a Montana prospector unearthed some sapphires and mailed them to him for appraisal, Tiffany appraised them and immediately sent him a check for $12,000. But in his store haggling over prices was not allowed; one paid the tagged price, however astronomical, and that was that.

Isabella II, before she lost her jewels. The tottering monarchies of Europe continued to transfer Old World wealth to the New via Tiffany & Co. In 1868, when a revolution deposed Queen Isabella II of Spain, the firm acquired her gems for $1.6 million and sold most of them to railroad tycoon Leland Stanford, so they could adorn his spouse. And in 1887, when the remaining French crown jewels were auctioned off by the very anti-monarchical Third Republic, Tiffany’s agent was of course on hand to acquire them; soon afterward, the necklace of the ex-Empress Eugénie (yes, that same Eugénie, now ousted), consisting of 222 diamonds in four rows, was seen at a ball gracing the neck and shoulders of Mrs. Joseph Pulitzer, the consort of the renowned newspaper publisher.

Isabella II, before she lost her jewels. The tottering monarchies of Europe continued to transfer Old World wealth to the New via Tiffany & Co. In 1868, when a revolution deposed Queen Isabella II of Spain, the firm acquired her gems for $1.6 million and sold most of them to railroad tycoon Leland Stanford, so they could adorn his spouse. And in 1887, when the remaining French crown jewels were auctioned off by the very anti-monarchical Third Republic, Tiffany’s agent was of course on hand to acquire them; soon afterward, the necklace of the ex-Empress Eugénie (yes, that same Eugénie, now ousted), consisting of 222 diamonds in four rows, was seen at a ball gracing the neck and shoulders of Mrs. Joseph Pulitzer, the consort of the renowned newspaper publisher. Not that Charles Lewis Tiffany was infallible. In 1872 word of a discovery of diamonds in a mine in Arizona reached New York, and a clutch of speculators, eager to buy stock in the mine, consulted him. Shown the diamonds in the rough, he announced, “They are worth at least $150,000.” The speculators then invested four times that in the mine, but subsequently a government geologist went to the site, which was in fact in Utah, and discovered that it had been “salted” with poor-quality stones from South Africa. Informed of the fraud, Tiffany confessed, “I had never seen a rough diamond before.” And he lost $80,000 in the swindle himself.

As the city spread northward and the affluent middle class migrated uptown to more fashionable districts, Tiffany & Co. migrated with them. By the 1860s the firm was at 552 Broadway, occupying an ornate five-story building with round-arched windows and, over the main entrance, a nine-foot carved-wood Atlas shouldering a huge clock that was said to have stopped at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865, the exact moment of Abraham Lincoln’s death. (Painted to look bronze, Atlas would accompany the firm on its migrations thereafter and overlooks the Tiffany entrance on Fifth Avenue today.)

And what did one see in Tiffany’s window in those days? A mishmash of cluttered objects, some made by Tiffany and some imported: bronze figurines, vases and cups and goblets, fancy lace fans, jeweled clocks and caskets, ornate silver picture frames, and draped over everything in profusion, strings of pearls. Such was the bric-a-brac that the Victorians used to clutter up themselves and their parlors; one can well imagine the smaller items clustered on the shelves of a whatnot, next to a daguerreotype of young Danny in his Civil War uniform and, in a fancy frame, a lock of Aunt Millie’s hair.

Tiffany's, circa 1887.

Tiffany's, circa 1887.Probably not on display was the famous Tiffany Diamond, weighing 287.42 carats, discovered in South Africa in 1877 and purchased by the firm for $18,000. The young gemologist whom Tiffany entrusted with cutting it down studied the diamond for a year before starting work. He then carefully cut it down to 128.54 carats, adding 32 facets for a total of 90, and thus created a dazzling multifaceted gem that, never sold, has highlighted Tiffany exhibits throughout the world ever since. Only two women have ever worn it: Mrs. Sheldon Whitehouse at a Tiffany ball in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1957, and Audrey Hepburn in 1961 publicity photographs for the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. The film helped refurbish Tiffany’s then sagging reputation, and for years afterward visitors coming to the store would ask where breakfast was served. Today the diamond is displayed on the main floor of Tiffany’s flagship store on Fifth Avenue at 57th Street.

The Tiffany diamond, topped by a bird.

The Tiffany diamond, topped by a bird.Shipguy

But Charles Lewis Tiffany marketed any rarity that he thought might sell. In 1858, when the Atlantic cable at last reached Ireland and established a transatlantic telegraph link, he acquired 20 miles of the cable salvaged from unsuccessful earlier attempts to lay it, and sold four-inch snippets for fifty cents apiece, as well cable-adorned canes, umbrellas, paperweights, watch fobs, and lapel pins that the public snapped up eagerly – so eagerly that the police had to restrain the crowds.

In the late nineteenth century Tiffany’s produced fine silverware that won international prizes, and in 1894 built a huge factory in Newark to make such luxury items as the silver plate favored by Delmonico’s, as well as exotic leather goods and engraved stationary. By now, obviously, the firm was catering to the rich and famous.

Tiffany no. 2, circa 1908. When Charles Lewis Tiffany died in 1902, his son, Louis Comfort Tiffany, became vice-president, but Tiffany no. 2 was more of a painter than a merchant. The major contribution of his Tiffany Studios was the Tiffany lamp, a costly handcrafted item marketed to the wealthy. Recent scholarship has revealed that it was not no. 2 but an artist named Clara Driscoll who designed many of the most famous lamps, which were turned out by her team of “Tiffany Girls.” Introduced to the public at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, the lamps became very popular on both sides of the Atlantic. The New York Historical Society’s collection of 132 Tiffany Lamps was the gift in 1984 of a single collector, Dr. Egon Neustadt, an Austrian-born New York City orthodontist and real estate developer who had been collecting them since 1935, when he and his wife bought their first lamp in a Greenwich Village antique store.

Tiffany no. 2, circa 1908. When Charles Lewis Tiffany died in 1902, his son, Louis Comfort Tiffany, became vice-president, but Tiffany no. 2 was more of a painter than a merchant. The major contribution of his Tiffany Studios was the Tiffany lamp, a costly handcrafted item marketed to the wealthy. Recent scholarship has revealed that it was not no. 2 but an artist named Clara Driscoll who designed many of the most famous lamps, which were turned out by her team of “Tiffany Girls.” Introduced to the public at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, the lamps became very popular on both sides of the Atlantic. The New York Historical Society’s collection of 132 Tiffany Lamps was the gift in 1984 of a single collector, Dr. Egon Neustadt, an Austrian-born New York City orthodontist and real estate developer who had been collecting them since 1935, when he and his wife bought their first lamp in a Greenwich Village antique store.The successors of the Tiffany family abhorred publicity, and under their direction the firm produced staid and predictable merchandise. By the 1950s sales had shrunk to half the level of the generation before, and the firm risked bankruptcy. Whether the general public was aware of this is uncertain, since when I came to New York in the 1950s the name “Tiffany’s” still had cachet, suggesting fine products for the elite who were willing to pay accordingly. Things changed for the better with the coming of Walter Hoving, the Swedish-born American businessman who became president of Tiffany & Co. in 1955 and held that post until 1980.

A tall and distinguished-looking man, impeccably tailored, Hoving began by getting rid of everything in the store that did not meet his standards, marking down silver matchbook covers to $6.75 and emerald brooches to a mere $29,700. Hoving has been called a snob, but under his guidance the quality of the merchandise improved and customers flocked. Among the shoppers on several occasions was President John F. Kennedy, whom Hoving dealt with personally in private, and who bought items for his wife. When Kennedy asked if the President got a discount, Hoving pointed to a portrait of Mary Lincoln wearing a strand of Tiffany pearls and replied, “Well, President Lincoln didn’t receive one.” So Kennedy paid full price.

The Trump Tower (the tall one, of course).

The Trump Tower (the tall one, of course).InSapphoWeTrust Hoving was a shrewd businessman, but Donald Trump was shrewder. Wanting the Bonwit Teller site at 727 Fifth Avenue, next door to Tiffany’s, to build his Trump Tower, The Donald also coveted Tiffany’s air rights, which would let him build a structure that would otherwise exceed regulations. So he presented to Hoving a sketch of a hideous building that he knew the fastidious Hoving would abhor, so that Trump could then offer to build a far more attractive building if Hoving sold him the air rights. Dreading the prospect of an ugly building right next door that would devalue his beloved Tiffany’s, Hoving agreed, and Trump got the air rights. The Bonwit Teller store was then carefully demolished – in this exclusive neighborhood, no wrecking balls or explosives allowed – and the 62-story Trump Tower went up.

Hoving left in 1980 because Tiffany’s had been acquired by Avon Products in 1979. A buyout by management followed, and in 1987 Tiffany’s became a public company and raised $103 million through the sale of its common stock. During the 1990-1991 recession it turned to mass merchandising, presented itself as affordable to all, and advertised diamond engagement rings starting at $850. A brochure entitled “How to Buy a Diamond” went out to 40,000 people who had dialed a toll-free number. The founder, Charles Lewis Tiffany, was adept at publicizing his wares, but what he would have thought of these modern expedients I leave to the viewers’ imagination.

One thing is clear today: genuine Tiffany lamps are still prized items that sell for tens of thousands. But plenty of imitations are on the market, since they are advertised online for as little as $64.78. So how does one tell the authentic lamp from the knockoffs? Some clues are very technical; here are several simpler things to look for:

· A bronze base. Not wood, plastic, brass, or zinc.· The color of the glass changes when the lamp is lit.· A Tiffany Studios stamp and a number on the base.· Signs of age; it won’t look brand new. (But some fakes mimic age on the base.)· A ring of grayish lead in the hollow base.· The glass shade, if knocked gently, should rattle.

Also, a buyer should ask for a money-back guarantee and beware of any shop that won’t give one. Not that there’s anything wrong with cheapie Tiffany lamps that don’t claim to be authentic; they have their place in the market. It’s the ones that are deliberately made to look like and sell as authentic ones that cause trouble.

One almost final note: in 2013 a former Tiffany vice-president was arrested and charged with stealing more than $1.3 million in jewelry. This development, for sure, would make founder Charles Lewis Tiffany turn over in his Green-Wood Cemetery grave in Brooklyn.

Tiffany's today.

Tiffany's today.David Shankbone

Since 1940 Tiffany & Co. has occupied a granite and limestone building on Fifth Avenue at 57th Street, with a grandiose stainless-steel entrance overlooked by the nine-foot near-naked Atlas that has been shouldering a clock for Tiffany’s since 1853. And what does Tiffany’s offer today? Their website promises free shipping on orders of $150 or more, and advertises gifts under $500. Clearly, they want to appeal, if not to the masses, at least to the modestly affluent. But modest they themselves aren’t, claiming to be “the world’s premier jeweler and America’s house of design since 1837.” Among their offerings is an item labeled “quintessential Tiffany,” a dazzling sixteen-stone ring in 18-karat gold with diamonds from Parisian designer Jean Schlumberger, a marvel whose “timeless perfection … deserves a place of honor in every stylish woman’s jewelry box.” The price? $9,000, which is reasonable indeed when compared to Schlumberger’s Croisillon bracelet in 18-karat gold for $30,000. And remember, no haggling.

Atlas still holds the clock today.

Atlas still holds the clock today.Meg Lessard

A bulletin from the health-care front. My eye doctor, a very no-nonsense type who wastes no time on small talk, wanted me to get an eye-drop refill immediately from the pharmacy on the ground-floor of the clinic. One of her assistants phoned the clinic to order the refill, then informed me, “The pharmacy needs a twenty-four notice to –” Hearing this, my doctor seized the phone, jabbered fiercely, then hung up and announced, “You can pick it up downstairs now.” Her two assistants who witnessed this were smiling already. “We all know where the power is,” I said softly to them, and they grinned from ear to ear.

End of story? No way. When I went down to the pharmacy, the pharmacist informed me that if I got the refill now, my insurance wouldn’t cover it, so it would cost $120. But if I waited two days, the refill would be covered and cost only $35. So I chose to wait. Moral of the story: In the health-care universe doctors are gods, but insurance companies are super gods. So it goes.

Coming soon: The rich of today, who make those rags-to-riches nineteenth-century types look absolutely quaint. We’ll get with it with hedge fund managers, corporate raiders, and the like. And guess who is the richest New Yorker? You may – or may not – be surprised. (Clue: it isn’t Donald Trump.)

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on November 15, 2015 12:52

November 8, 2015

205. The Rich

1845

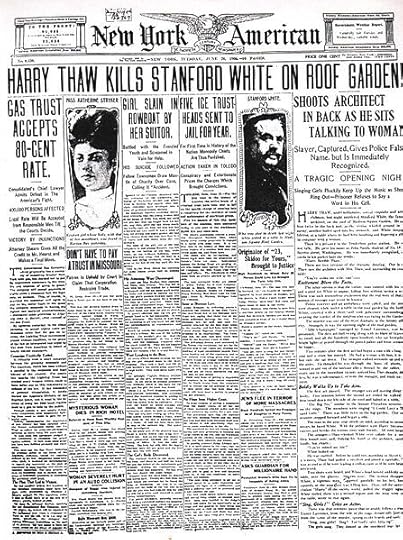

They are always there and we acknowledge the fact with our envy or our resentment. And they’ve always been especially conspicuous in New York City. So let’s have a look at who they are – or were – and how they got their money, starting in 1845. Why 1845? Because that year saw publication of the sixth edition of Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of New York City, offering an alphabetical list of all persons in the city believed to be worth $100,000 or more, with the sums appended to their name, along with, as the preface states, “interesting biographical and historical matter, as derived from the consultation of books and living authorities.”

All of which suggests a compendium of The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and People magazine, a formality worthy of Barron’s spiced up with some juicy tidbits like those featured in the gossip magazines prominently displayed in supermarket check-out lanes. But remember, this was 1845, not 2015. And the publication was answering a need, since in those days there was no official agency offering credit ratings of individuals or businesses, and this lack became obvious during the Panic of 1837 and its aftermath, when bankruptcies multiplied throughout the city and the nation. People wanted to know who was financial sound and who was not. So Moses Y. Beach, publisher of The Sun, a prominent New York daily, got busy and produced this publication. And if $100,000 sounds like a low entry level for admission to its pages, it’s worth remembering that an 1845 dollar would be worth $31.25 today, so multiply all the figures accordingly.

So who had the biggest fortunes in 1845? There’s no doubt about #1, John Jacob Astor, whose $25 million made in the fur trade and New York real estate established him as the richest man in the entire country and earned him two full columns of comment in tiny print, more than anyone else in the publication. He is hailed as a truly great man, a German immigrant who arrived on these shores as a common steerage passenger, a poor uneducated boy who didn’t speak English, but who through his own industry accumulated a fortune “scarcely second to that of any individual on the globe, and has executed projects that have become identified with the history of this country, and which will perpetuate his name to the latest age.” His princely house on Lower Broadway, furnished with “richest plate” and works of art, and staffed with an army of servants, including “some from the Empire of the Celestials,” is viewed with admiration and awe. Moses Beach estimates his income at $2 million a year ($62 million in today’s dollars), which for 1845 was an unprecedented sum. Also noted is Astor’s gift of $350,000 for the creation of a library in New York City that would bear his name, and that in time merged with two other libraries to create the New York Public Library of today. All in all, the career of John Jacob is presented to the reader as a classic but exceptional example of rags to riches, a theme that Beach's preface promised to celebrate. But his portraits suggest only riches and dignity, no hint of rags or steerage.

John Jacob Astor, an 1825 portrait. Dignity,

John Jacob Astor, an 1825 portrait. Dignity,plus a neck cloth (no ties as yet).

Sadly, the subject of this encomium, now 82 years old, was suffering from ill health. White-haired and portly, with an iron jaw under folds of loose flesh, he walked only with the help of attendants, took short carriage rides, struck others as dignified but tired. Yet he was still alert when it came to moneymaking and tight with his pennies, for in his mind he was still the penniless youth who came to this country in steerage. While dining with a friend once in a new hotel, he eyed the proprietor and announced to his friend, “This man will never succeed.” “Why not?” asked the friend. “Don’t you see what large lumps of sugar he puts in the sugar bowl?”

The second richest man in the city, with $10 million according to Moses Beach, was Stephen Whitney, another rags-to-riches story, who started out poor as a retail liquor merchant, went into the wholesale liquor business, speculated with great success in cotton, and also invested in real estate. Liquor, cotton, and real estate – three sure ways for a shrewd New Yorker to make money, and Beach assures us that Whitney was very shrewd, and also “very close in his dealings.” Is he remembered today? Hardly. Unlike old John Jay and his descendants, Whitney had little time for philanthropy.

Stephen van Rensselaer no. 3 The third largest New York City fortune, matching Whitney’s at $10 million, was not a living person but the estate of Stephen van Rensellaer (d. 1839) of Albany, who qualified for inclusion by virtue of his ownership of hundreds of lots in New York City. But city real estate, however substantial, was simply a shrewd side investment, since Stephen van Rensellaer (the third of that name) had been the fifth in a long line of Dutch patroons, lords of the huge semi-feudal estate of Rensellaerswyck, comprising vast lands on either side of the Hudson River both above and below Albany. Whether a vast feudal estate where a Rensellaer lorded it, however benevolently, over 3,000 tenants was appropriate in a modern, democratic age, Moses Beach never questions, though the tenants were beginning to do so in what would become the anti-rent movement and put an end to the anachronistic patroonship.

Stephen van Rensselaer no. 3 The third largest New York City fortune, matching Whitney’s at $10 million, was not a living person but the estate of Stephen van Rensellaer (d. 1839) of Albany, who qualified for inclusion by virtue of his ownership of hundreds of lots in New York City. But city real estate, however substantial, was simply a shrewd side investment, since Stephen van Rensellaer (the third of that name) had been the fifth in a long line of Dutch patroons, lords of the huge semi-feudal estate of Rensellaerswyck, comprising vast lands on either side of the Hudson River both above and below Albany. Whether a vast feudal estate where a Rensellaer lorded it, however benevolently, over 3,000 tenants was appropriate in a modern, democratic age, Moses Beach never questions, though the tenants were beginning to do so in what would become the anti-rent movement and put an end to the anachronistic patroonship.Other multimillionaires of 1845 include William B. Astor ($5 million), John Jacob’s son, another shrewd investor in Manhattan real estate; Peter G. Stuyvesant (($4 million), a descendant of the one-legged last Dutch governor of New Amsterdam, from whom Peter G., Beach informs us, has inherited and kept the silver spoon; and James Lenox ($3 million), who inherited from his father and, so Beach assures us, “devotes himself chiefly to pious objects.” Actually, he was acquiring rare manuscripts and books, including Bibles, and paintings, busts, engravings, and other art works for what would become the most valuable such collection in the hemisphere and be housed in the Lenox Library, which in time would be consolidated with two other libraries to create the New York Public Library. If with the Astors, father and son, one sees money-getting finding time for philanthropy, James Lenox shows inherited wealth devoting itself almost exclusively to cultural activities from which the whole community will benefit in time. Sooner or later, money begets culture.

A Gutenberg Bible, circa 1455, in the Rare Books Division of the New York Public Library.

A Gutenberg Bible, circa 1455, in the Rare Books Division of the New York Public Library. From the Lenox Library. One of James Lenox's "pious objects."

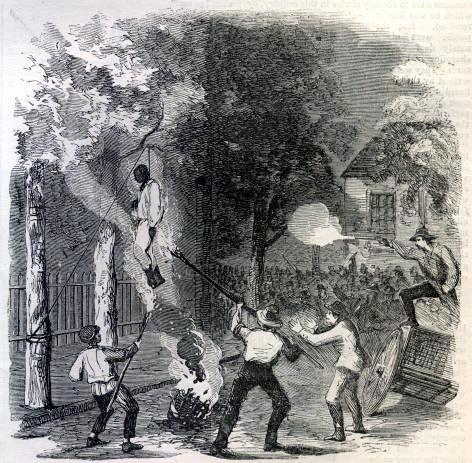

NYC Wanderer Of the eleven other millionaires, three names stand out, albeit for very different reasons. Peter Harmony is said to have come to the city as a poor cabin boy born in the West Indies, and to have lately retired from the shipping business with a princely fortune ($1.5 million). (He was in fact an immigrant from Spain.) “Some of his ships to Africa, it is said, have brought out cargoes that have paid a profit equal to the difference in price between negroes in Africa and Cuba.” Which is a pretty clear reference to the illegal but lucrative and still flourishing slave trade that brought Africans to the Spanish colony of Cuba, where sugar plantations still provided a market, and officials looked the other way.

Jonathan Thorne is described as “the very pink and glass of fashion in the Parisian circles,” and this despite his descent from old Quaker ancestors who would wonder at his “gorgeous private chapel at his imperial mansion in the French capital.” “What changes in the wheel of fortune,” Beach adds, “from an humble purser in the navy?” How a humble purser achieves a fortune of $1 million and a mansion in Paris, Beach fails to explain. But he is clearly on the side of hard work and business, and not on the side of fashion.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, credited with $1.2 million, rates only a short paragraph, since Moses Beach could not anticipate the future railroad king and titan of finance. But Beach recognizes energy when he sees it: “Of an old Dutch root. Cornelius has evinced more energy and ‘go aheadativeness’ in building and driving steamboats and other projects than ever one single Dutchman possessed.” It takes the American hot sun, he adds, to clear off the fogs of the Zuyder Zee and wake up the phlegm of a descendant of old Holland.

Though full of admiration for many, Moses Beach was at times ready to pronounce a moral judgment as well. Just hear him, no doubt with memories of the Panic of 1837 and its aftermath, praise a team of mechanics who became celebrated engravers of bank notes. By contrast, he asks, what utility is to be seen in “swindling stock operations … deemed more reputable than the walks of mechanic life.” No longer, he insists, can dreaming speculators and fancy operators sneer at the “brawny arms” and “russet palms” of the honest laborer. The false system of credit that once prevailed has been eliminated, he declares, “breaking up the nests of lounging, idle upstarts, that like mushrooms on a dung-hill sprouted up out of the masses of rag-paper and spurious capital.” And what would Mr. Beach say today, in the wake of our own recent financial convulsion, when such novel phenomena as collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps appeared, and still appear, to the bafflement of many and the enrichment of a few?

The first half of the nineteenth century in New York was the age of the merchants, when success in trade brought wealth. Most of Beach’s subjects dealt in things you could see, touch, taste, or smell: silks, cotton, tea, furs, chinaware, brandy, ships, and real estate. And in a few cases, slaves. Not that rich marriages and inherited wealth didn’t help.

Among the names that had yet to achieve their greatest success was Phineas T. Barnum, proprietor of the American Museum and guardian of the celebrated midget Tom Thumb. Reported to be currently in Europe exhibiting said Thumb, “by whom he is coining money,” the master of showmanship and humbug is said to be worth $150,000. Yet his sensational promotion of Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, lay five years in the future, and his traveling circuses had yet to be organized.

Another New Yorker just at the start of his career is Irish-born Alexander T. Stewart, worth $800,000, already a “celebrated Dry Good Merchant of Broadway whose shop is the grand resort of the fashionables.” Yet he rates only a mere six lines. Rest assured, we will hear of him again.

For an unusual name no one can match Preserved Fish, a sea captain turned shipping merchant worth $150,000, and president of the Tradesmen’s Bank. Beach presents him as “an example of an uneducated man, of strong mind, exercising great influence in his sphere.” But how he got his outlandish name Beach does not explain. Other sources state that Fish was of Huguenot stock, and that his father and grandfather bore the same first name, which they pronounced in three syllables, pre-SER-ved, meaning “preserved from sin” or “preserved in grace.”

Catharine Sedgwick, an illustration probably dating from the early 1800s.

Catharine Sedgwick, an illustration probably dating from the early 1800s.Women are far and few in Moses Beach’s compilation, and then almost always as widows or heirs of males. The one exception is Catharine Sedgewick, a “distinguished novelist” famous for her “New England Tales,” a “religious satire published some 20 years since.” Though she received a “snug” fortune by inheritance, she “has reaped a large income from her books, the circulation of which exceeded those of any American author.” Though she seems to have resided in Massachusetts, she gets a princely seventeen lines and is credited with $100,000. Here, then, is an early example of the “scribbling females” that Nathaniel Hawthorne would acknowledge with scorn, writers whose novels, not rated highly today, were widely read in their time, often bringing in income that the less pecunious male writers of the day envied and resented bitterly.

1863

No other source that I know of gives as comprehensive and colorful an account of New York’s wealthy as does Beach, but the income tax imposed by the federal government during the Civil War lets us know who then were the wealthiest citizens of New York, for in January 1865 the enterprising but often controversial New York Herald published the names of prominent citizens paying the tax, prompting protests at this invasion of privacy, and a New York Times editorial observing that “the most glaring and shameless frauds are practiced in the return of incomes, and in the assessment of taxes upon them.” Men living at the rate of anywhere from $10,000 to $30,000 a year, it insisted, were put down as having no income at all, an assertion that the New York Tribune echoed.

And that wasn’t the end of it, for later in that same year of 1865 the American News Company published The Income Record: A List Giving the Taxable Income for the Year 1863, of Every Resident of New York. The publisher’s stated goal was “to satisfy an imperious public curiosity, which thus far has been only partially gratified by the public journals”; to let citizens decide whether their neighbors had been honest in stating their income; and to provide trustworthy statistics to future legislators for revisions of the tax laws. Many a moneyed gentleman, one suspects, trembled in his ruffled shirtfront and shiny boots at the prospect of having his income revealed yet again, and so authoritatively, to the public.

So who, according to this tabulation, were the wealthiest citizens of 1863? The top three:

A.T. Stewart $1,843,637William B. Astor $838,525Cornelius Vanderbilt $680,728

All three appeared in Moses Beach’s tabulation of 1845, but times have changed and they now eclipse all others in wealth.

Alexander T. Stewart, circa 1860. Beards and

Alexander T. Stewart, circa 1860. Beards and neckties are in, neck cloths are out. Stewart’s income astonished the public and probably establishes him as the most honest of the lot. His new department store on Broadway at 10thStreet, a six-story cast-iron structure with a glass-dome skylight, built in 1862 and occupying most of a whole block, employed some 2,000 people, had hydraulic elevators, and offered fashionable society a wide range of fabrics, scarves, shawls, lamps, carpets, bric-a-brac, and toys. Hailed today as the father of the modern department store, this generously bearded gentleman prospered to the point of being considered – for a while – the richest man in the country.

Stewart's department store, the granddaddy of Bloomingdale's,

Stewart's department store, the granddaddy of Bloomingdale's,Macy's, and Marshall Fields.

William B. Astor circa 1850, looking just

William B. Astor circa 1850, looking justas formal, dignified, and (let's face it)

stodgy as his father. William B. Astor, the son of old John J. and his chief heir, was heavily invested in New York City real estate, earning him the name of “the landlord of New York.” He also gave money to the Astor Library founded by his father. Upon his father’s death in 1848, William was considered the richest man in America with a fortune of $14 million, which makes his 1863 declaration of annual income of $838,525 perhaps a bit suspect. Photographs reveal a rather full-faced man, clean-shaven with long sideburns and a hint of jowls, a competent heir who lived a profitable but uneventful life devoid of his father’s eccentricities and flair.

If Commodore Vanderbilt’s figure of $680,728 likewise seems to err on the side of modesty, it’s worth remembering that in 1863, having sold his ships, he was just beginning to acquire the railroad empire that would increase his fortune vastly and make him the richest man in the country, referred to endearingly in the late 1860s as Old Sixty Millions. In photographs Vanderbilt appears tall and erect, with a strong nose and a square jaw, his gray hair turning strikingly white. Beside such a figure the other two top moneybags of the day, Stewart and Astor, seem just a bit bland, but then, anyone compared to the vibrant and often ruthless Commodore would have come off bland indeed.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, dated by my source as "before 1877." I should think

Cornelius Vanderbilt, dated by my source as "before 1877." I should think so, since that's when he died. But to my eye, he comes across as more forceful

and energetic than the other moneybags pictured in this post.

This supremely pecunious trio – Stewart, Astor, and Vanderbilt – resembled the wealthy of 1845 in that they dealt in tangibles: a department store, real estate, and railroads. And if Astor’s making a fortune in real estate and being known as the landlord of New York didn’t necessarily benefit society at large (who loves a landlord anyway?), Vanderbilt’s New York Central line got people from New York to Chicago and back efficiently, and Stewart’s dry goods palace dazzled them with its offerings of this world’s goods.

The Gilded Age

Caroline Schermerhorn Astor -- the Mrs. Astor --

Caroline Schermerhorn Astor -- the Mrs. Astor --entertaining at one of her balls. The ladies'

gowns rustle on the floor but are decidedly

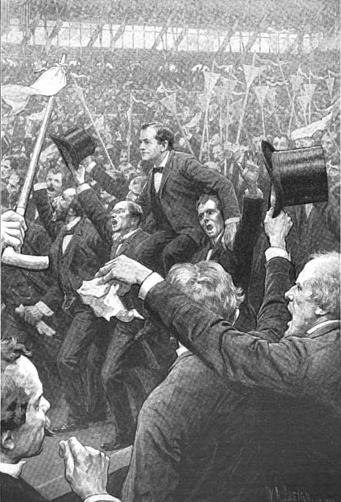

low-necked.The Civil War ended in 1865, following which came the so-called Gilded Age, when the rich dressed rich, paraded about in fancy turnouts, built palatial mansions, raced their yachts, hitched their moneyed daughters to impoverished European noblemen (most of them accomplished debauchees), and generally enjoyed the good life free from such annoyances as an income tax. On the Upper Fifth Avenue the Vanderbilts and Astors leapfrogged over one another, building ever more palatial mansions that made their rivals’ residences lower down on the avenue look opulently shabby, while Mrs. Astor – the Mrs. Astor, whose mail required no other designation to reach her – welcomed annually to her ballroom, which held just four hundred guests, the select four hundred persons deemed by her to be socially acceptable. Needless to say, the simplicity of an earlier age, when flaunting your wealth was frowned on, had vanished, and often as not the pampered descendants of those earlier moneymakers felt no need to smirch their hands with toil.

On this happy note I will end. The rich of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – a very different species -- will be looked at in a future post. As well as The Donald, who merits a post all his own.

The book: The selection of posts from this blog is available in print version at $14.95 (or cheaper), and as an e-book with Nook, Kindle, etc., for $3.99. One of the online come-ons describes it in a unique brand of English: "Stories excluding the Authorization Agitating Metropolitan area in the Copernican universe … art critic Clifford Browder leaves no wallpaper unturned … a invest that so muchness are worthy to caw home." One copy of the print version is offered free on a Goodreads giveaway through November 18.

Coming soon: Tiffany’s: The magic of their lamps (and how to tell a genuine one from a fake), the tiny lustrous vase in our apartment, a great fraud, and how The Donald bamboozled the Tiffany’s of today. Plus a mystery: How did Marie Antoinette’s diamonds end up over here?

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on November 08, 2015 05:23

November 1, 2015

204. People of New York

The marrying man

Gino Filippino, a trim-looking 53-year-old who favors tailored designer suits, has an unusual occupation: when not selling real estate, in his capacity as a justice of the peace he arranges and performs civil weddings for out-of-towners, many of them foreigners, who want to achieve their nuptials not in some quiet church, but amid the bustle and brouhaha of Manhattan. He and his staff handle the paperwork, flowers, cake, champagne, photographers, and musicians, if such are required, but above all he helps the couples pick the spot for the wedding. He has married both gay and straight couples in Central Park, dodging power lawnmowers and the blaring noise of tree pruners at work, and on the Brooklyn Bridge amid the roar of traffic, in busy Grand Central Station, and at the Top of the Rock, the observation deck of Rockefeller Center, with its breathtaking 360-degree views of the city.

Night view from the Top of the Rock. Okay for a wedding?

Night view from the Top of the Rock. Okay for a wedding?Daniel Schwen The unusual is his specialty. He has bribed employees to let him do a quickie in the Waldorf Astoria and other fancy hostelries, and once even married two hippies from California in bed at the elegant Plaza Hotel. While he has on occasion staged elaborate ceremonies on a yacht in the harbor, most of the weddings are what he calls “hitch-and-gos,” done in a matter of minutes and costing $500 and up. Often he has to shoo homeless people away from the marriage sites, but at other times he recruits them as witnesses to sign marriage licenses. And once he even had to read the vows for a bride who was too drunk to manage it herself.

Grand Central Station. Would you like to be married here?

Grand Central Station. Would you like to be married here? Or here? The Waldorf Astoria lobby, okay for quickies.

Or here? The Waldorf Astoria lobby, okay for quickies.Alan Light How many weddings has he done? Over 200 a year, and even 11 in a single day, most of them in Central Park. But he himself isn’t married, though in New York State he could be, since same-sex marriages are now legal. He lives with his partner on the Upper West Side and operates out of an office in Columbus Square. “I’m the marrying man,” he explains, his purpose in life to give visiting couples the “New York moment” they desire – a unique experience they won't soon forget.

There’s no place like home

Eleanor Murray, a plump, white-haired 93-year-old, has one claim to distinction: she has lived all her life in an unassuming five-floor walk-up at 531 West 135th Street in Manhattan. “And I mean my whole life,” she told an interviewer; “I was born in the basement.” Indeed she was, since her mother, a Hungarian immigrant, was the building’s super and lived in a basement apartment, rising daily at 4:00 a.m. to shovel coal into the boiler. There she gave birth to Eleanor – in the apartment, not the boiler -- with the help of a midwife and then probably went right back to work. Her family knew all the people in the building, “all good family people, no roomers.”

By the age of 13 Eleanor, the fourth of five children, was helping to clean the building and shoveling coal herself. Then, at 16, she and a sister moved into the two-bedroom apartment on the third floor where she still lives today. The rent then was $31 a month; today, being rent-regulated, it is a mere $500, which gives her yet another reason to stay. Not that she would move anyway. “I never wanted to move, because I love the neighborhood and I’d never leave my church.” Her church is the Church of the Annunciation on Convent Avenue, where she and her six children attended grammar school, and where she married her husband, John Murray, who managed a warehouse on the Hudson River waterfront, and who died in 2001.

Much has happened over the years. She remembers swimming across the Hudson to New Jersey with friends, and the time when a cosmetics factory went up in flames, and “the neighborhood smelled beautiful for months.” She worked as a buyer at Bloomingdale’s department store, and attended Baruch College, but never graduated because she left to have children; later, she worked in the registrar’s office at City College. In 1988 her mother, age 99, died on the very couch in her living room where she sat to be interviewed.

When she grew up, the neighborhood was all Irish working-class immigrants, but today they have disappeared, replaced by Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Mexicans, and others. “I’m the last of my gang left, but I still love the people in the neighborhood.” Robust and cheerful with a hearty laugh, on nice days she sits with friends on a bench on the Broadway median, ignoring the traffic roaring by on either side, and takes food to an incapacitated neighbor. When she visits a daughter in New Jersey she doesn’t stay long, missing the noise and excitement of the city. A committed New Yorker, she leans out her window and waves to the open-air tour buses passing by on 135thStreet, shouting, “Welcome to New York!” As for the future, she has no doubt: “I’m staying here till I die.” And she laughs.

A Broadway chorus boy

Ted was a Broadway chorus boy, young, short, and blond, more “cute” than stunningly good-looking, whom I knew in the 1950s and 1960s, when I was a graduate student at Columbia and subsequently began teaching French. We met in Ogunquit, Maine, where he was appearing in the musical Pajama Game, and reconnected in New York, where, through him and his friends, I got a glimpse into the life of Broadway chorus boys.

Broadway theaters at night.

Broadway theaters at night. UpstateNYer

Their world was a world within a world, small, exciting, self-contained. Ted lived in a cold-water flat in the West 40s, near the theaters, his agent, and the bars that the chorus kids frequented. Cold-water flats, being what they were, were low-rent apartments, and as such got passed along from one struggling young actor or dancer to another; Ted’s had once been the home of the veteran stage and film actress Jo Van Fleet, whom I especially remember from her role in the movie East of Eden. Ted’s apartment, as I dimly recall, was small and sparsely furnished, probably with running cold water in a sink; for baths and other bodily needs, he had to go down the hall to a communal facility. But this was how the chorus kids lived; they were glad to get such a place and thought no more about it. It was less a home than a base of operations; their real life was on the stage, whether in the city or on tour, and in the bars.

Ted had been in a number of big-time Broadway musicals, including Guys and Dolls, as commemorated by a number of photos on his wall. Among them was one showing him in a classical ballet pose with a female dancer, but it seemed all wrong for him, whereas Guys and Dolls and Pajama Game seemed right, and he knew it. His life was a matter of waiting for phone calls from his agent about a possible part in a musical. He had strange and hilarious stories to tell about try-outs and casting. On one occasion he was told, “Sorry, Ted. You’re just what we need, but we don’t want another blond in the chorus.” So he went out and got a dark-haired wig, hurried back, and tried out again. They laughed and said, “Okay, okay, you’re hired. But don’t wear that lousy wig; dye your hair.” And to me he explained, “Sometimes you have to do their thinking for them.”

“Don’t you ever just walk into a part and get hired immediately?” I asked.

“Just once. The male chorus in The Boyfriend is supposed to be English, but there’s one American. When they saw me, they said, ‘We hope you can sing and dance. You’re short and blond, just what we want for the American.’ ” Ted could sing and dance; he got the role.

Ted's world, not mine.

Ted's world, not mine.Ted had tales to tell about rehearsals as well, like the time they had the heaviest of the women dancers paired off with him, the smallest of the males. When, at one point, the girls were supposed leap up on their partner’s shoulders, Ted’s partner slid right down to the floor, taking his pants with her. “Embarrassing,” he told me. “There I was only in my dance belt,” meaning the jock worn by male dancers. But he was laughing as he told me.

At Ogunquit, on the last night of the performance there, he invited me into his dressing room, where I saw him and two other dancers, seated in their underwear, busily applying makeup. It was the last night of the tour, always a time of joyous celebration and hijinks, with jokes and banter flying about. Ted planned to black out some of his teeth and then, during the performance, flash a gap-toothed smile at a friend onstage, hoping to break him up. But one of the company’s staff, wise to the ways of dancers, made an announcement warning against such shenanigans. “Remember,” he said, “you may want to work for these folks again.” So Ted didn’t blacken his teeth.

When there were few shows in the offing, dancers had a recourse to industrials, lavish spectacles with dancers used by big corporations, especially automakers, to introduce a new product. Industrials went all over the country and they paid well, so dancers took them to bring in some cash, but their heart was in the theater. I recall seeing an industrial on a friend’s TV set, with dancers dancing around glistening new limousines lit with bright lights. Said my friend, who was in advertising and knowledgeable, “You wouldn’t believe what all of that costs!” Why dancers were needed to introduce a new model of car, I never quite grasped, but the automakers presumably knew what they were doing.

The social life of chorus boys was centered in a handful or more-or-less gay bars in the West 40s. I went to one once with Ted. The emphasis was less on cruising than socializing, and everybody seemed to know everybody. The latest bit of gossip was about a young dancer who had just broken up with his lover, the show’s dance captain, who had then got his ex fired. When the kid just fired showed up, all the others flocked around him to sympathize; the dance captain was vilified by one and all. As Ted observed to me, mixing your private life with your career was risky; he never did.

On another occasion a friend of Ted’s told him and some other dancers how he had got a part given up by a strikingly good-looking dancer. “I knew I couldn’t match him in looks, so I decided to strut like a stud, as if to say, ‘Honeys, what I’ve got going for me is right down there between my legs.’ ” All the other chorus kids agreed that, under the circumstances, this was the only thing to do.

Dancers were always socializing; they weren’t ones for quiet times at home with a good book, or for reflection. And when they went on tour, the socializing wasn’t diminished, for they were constantly being partied wherever they went. Once Ted met Tennessee Williams, who had invited the chorus boys to a private party. Williams scanned each as he arrived, and said to Ted, “Hmm, yes, you can stay.” Thanks a lot, Ted thought to himself, I thought I’d already been invited. But in Denver a wealthy young businessman was so taken with Ted that he offered to keep him in style. Ted politely declined the offer, which his admirer pressed repeatedly, sure that he could wear down Ted’s resistance. But Ted knew that in the long run such a relationship led nowhere; he stuck to his guns, said no.

Ted and I weren’t steady lovers, just on-and-off-again partners. Weeks, even months might pass, and then, on the spur of the moment, I would phone him and we would get together. We were of different worlds – me an academic, a teacher, and him a dancer steeped in the small, rich world of Broadway chorus boys. But at times he needed to come out of that world, even though he always went back into it. “It’s always good to see you,” he told me more than once. “Theater kids aren’t in the real world, they’re off in some fantasy world of their own.” At first I shrugged his remark off, but when he repeated it several times, I realized that it was for real, he was in that world but not altogether of it, he needed to come out and get a breath of fresh air. Seeing me was that breath of fresh air, and at the same time I could escape from my own world, the rich, small world of academics.

Ted knew that you can’t be a chorus boy forever – a problem explored decades later in the musical A Chorus Line. A few dancers end up teaching dance or becoming choreographers, but only a very few. Ted’s plan was to transition into acting. His acting teacher encouraged him, but his agent and others resisted; “Ted,” they said, “you’re a dancer.” Which didn’t leave much room for transitioning. Like all young actors in search of credits and experience, he took parts in what veteran actors laugh at and deride: children’s theater. In one, I recall, he played a mad physicist. I never saw him perform, but an acquaintance of mine did. “It’s fascinating how dancers get into a role,” he told me. “When I do it, I’m exploring the character’s emotions, finding out what the character feels. But dancers do it through movements; they dance themselves into the role.”

But what chance did a dancer have of getting into acting in New York, when he was competing with a host of young actors doing the same? Often as not, an aging dancer – and in that profession aging comes fast – goes back to his hometown, Pittsburgh or Cleveland or Denver, where family and friends are waiting, and a job in some mundane profession offers the security that theater can never provide. More than once Ted told me, “You may get a phone call that can change your life.” Now he was waiting, not for a call offering yet another job as a dancer, but for a call offering a serious role as an actor. But as long as I knew him, that call never came.

One day I finally suggested to Ted that we continue as friends minus sex, prompting his wistful reply, “I hate for things to change.” Soon after that I met my partner Bob, and from then on Ted was out of my life. With hindsight, I regret this; it wasn’t necessary. I suspect that Ted finally went back to Pittsburgh or wherever and the inevitable mundane job. Now that decades have passed, I wonder what became of him, but probably I’ll never know. So it goes, with time.

Epilogue: The story of Ted has a surprise ending. After writing the above, on the spur of the moment I googled him by both his real name and his stage name, expecting nothing, since he was only one of hundreds of young male dancers who have their moment of glory on Broadway and then disappear into the maw of oblivion. But to my astonishment, several obits in New Jersey newspapers came up, announcing the death last spring of an 87-year-old man with the same two names, an inhabitant of Bayonne. What a coincidence! I told myself, but soon became convinced that this was, indeed had to be, the Ted I knew. This Ted was a Broadway chorus boy back when the Ted I knew was appearing in Broadway musicals and, when he retired from dancing, began working in wardrobe, and finally retired from that with honors after 45 years on Broadway. So Ted found a way to stay in Broadway theater after he left dancing, and it wasn’t acting. But the obit told me things I didn’t know:

· He was the son of a Pennsylvania coal miner, so that his leap into a career in dancing anticipated the story of the Broadway musical Billy Elliot.· He was a year older than me, whereas I had always thought he was two or three years younger.· He had been briefly in the military at the end of World War II.· After I knew him he married a dancer and by her had a daughter.

He was quoted as saying, “I had a wonderful life. I have no regrets. Always follow your dreams.”

My reaction to this news was astonishment, then sadness, then joy. Astonishment for obvious reasons. Sadness because I just missed discovering him in time to reconnect, talk old times, say hello and good-bye. And joy because he solved the problem of what to do when he quit dancing: he followed his dream and stayed in the world of theater that he knew and loved. To be backstage in wardrobe and not out there performing must have been an adjustment, but he managed. He had a rich, full life; I wish I could have shared a little of it in the years after I knew him almost a half century ago on Broadway. Good-bye, Ted, and good luck! Have a dance with the angels.

Source note: For information about Gino Filippone and Eleanor Murray, I am indebted to articles by Corey Kilgannon in the Metropolitan section of the Sunday New York Times of July 19 and September 27, 2015, respectively.

The book: The selection of posts from this blog is now available as an e-book on Kindle and Nook for $3.99.

Coming soon: The Rich. No, I don’t mean Donald Trump – not yet, at least. I mean a young foreigner who arrived here in steerage speaking no English and became the richest man in America. Also a slave trader, a Paris-inhabiting “pink and glass of fashion,” a ship captain named (I invent not) Preserved Fish, a “scribbling female,” the father of the modern department store, and the man who became known as Old Sixty Millions. What did these nineteenth-century moneybags have in common that makes them different from the moneybags of today? As for those moneybags of today, I'll get around to them in time, including, no doubt, the Donald.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on November 01, 2015 04:55

October 25, 2015

203. The Next Big Thing

It bursts upon the scene. Fans want to attend it, consumers want to buy it, investors want to invest in it before word gets around. It excites, it maddens, it intoxicates. Above all, it is something startlingly new, astonishingly different. And it can make the world better … or worse.

No, don’t mean the entrepreneur-led charitable foundation of that name that seeks to empower young entrepreneurs to take on the world, admirable a goal as that is. Nor do I mean any number of novels and high-tech gadgets and other stuff marketed online as “the next big thing.” I mean a rich variety of break-through inventions, styles, fashions, and fads that swept New York and the nation, if not the world, changing, or seeming to change, the way we live. Let’s have a look at some of them.

Fulton’s steamboat, 1807

In 1807 Robert Fulton’s pioneer North River Steamboat, later rechristened the Clermont, made the round trip on the Hudson River from New York to Albany and back in an amazing 32 hours. Amazing because, prior to this, the Hudson River sloops, sailing upstream against the current and often against wind and tide as well, took as much as three days just to get to Albany. Steamboats revolutionized traffic on the waterways of America and the world, bringing distant places closer together and, in New York State, letting New York City legislators get to the state capital expeditiously, so they could pursue their legislative schemes and stratagems, and try to keep upstate lawmakers, whom they termed “hayseeds,” from neglecting or abusing their beloved Babylon on the Hudson.

Steamboats on the Hudson at the Highlands. A Currier & Ives print of 1874.

Steamboats on the Hudson at the Highlands. A Currier & Ives print of 1874.Jenny Lind, 1850