Clifford Browder's Blog, page 39

September 13, 2015

197. 14th Street: from pig ears to Macs, divorce $499, an Art Deco grotto, and Gandhi

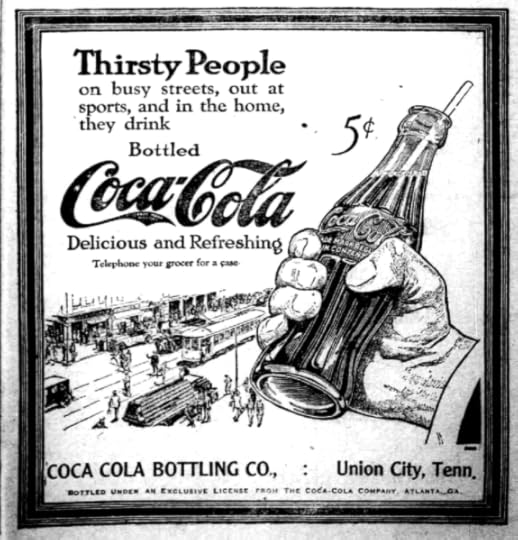

At first (and second) glance, 14thStreet in Manhattan has no beauty, no charm, no magic, no storied past, no architectural unity, no anything except two quintessential New York traits: energy and diversity. It is a hodgepodge of building styles, a jumble of noise, justifying itself simply as a useful crosstown artery that helps you get around. Forming a boundary between Chelsea on the north and Greenwich Village on the south, it partakes of neither. Its one redeeming quality is its rough-and-tumble character, its abundance of low-cost stores and restaurants, its appeal to the budget-minded. No gentrification here (not yet, at least); the street is down-to-earth, basic, and unashamedly out for a buck. As one store’s sign put it:

KEEP 14TH STREET GREENBRING MONEY

It’s not surprising, then, that the Greenwich Village Historic District stops just south of it, leaving it without landmark status; preservationists must have thought it a hopeless case, too commercial, too ugly, unworthy of protection.

But if one looks more closely, 14thStreet reveals pockets of beauty, chunks of history, slivers of charm. Let’s take a walk along the stretch I know best, ranging from Ninth Avenue on the west to Union Square on the east, and see what we can find.

On the northwest corner of Ninth Avenue and 14th Street the Apple store looms, a three-story edifice usually topped by a display of giant computer screens. I have trekked there several times, lugging my desktop on a cart, to consult computer "geniuses" about smoothing out computer kinks and exploring computer possibilities. Smiling young faces in blue T-shirts greet you at the entrance and direct you to the appropriate floor -- in my case, the top one, where the geniuses hold forth. Shunning the ultra-modern glass staircase, I take the elevator. Up there in a spacious area flooded with light from huge windows, I’m always the only customer with a cumbersome desktop; everyone else has a small, mobile laptop, so easy to carry about, but with far too small a screen for my purposes, which often require two full pages side by side on the screen.

AchimH

AchimHThe Apple store, the third in the city, opened at this location in 2007, but before that this was the gateway to the Meatpacking District, which stretched from here west to the river. The building itself was an outlet for Western Beef, where a former resident remembers seeing open barrels of pig ears and snouts in brine, jugs of pork bellies, and carpet-sized rolls of tripe. So here, right at the start of our trek, is a lesson about life in New York: for all its landmarking endeavors, the city is in constant flux. From pig ears to Macs – quite a change!

Going east from Ninth Avenue toward Eighth, you find mostly residential buildings on the north or uptown side of 14thStreet, some old and some new, their windows sprouting air-conditioners, and, for a sobering touch, a funeral home – all in all, rather dull. But the south side is anything but dull. In quick succession you encounter the following:

· Super Runners Shop· Keratinbar (a hair salon and not, as I at first thought, a karate school)· Centro Mexicano de Nueva York· Gourmet Deli, its doors wide open to the street· Best Chinese Qi Gong Tui Na, offering body work to heal almost anything· Perfect Brows Threading Salon· Chelsea Village Medical Building, where my partner’s doctor holes up, when not making house calls· Istanbul Grill, featuring Mediterranean cuisine· Insomnia Cookies· Rocky’s Brick Oven Pizza and Restaurant

Beyond My Ken But the dominant presence on the block is St. Bernard’s Roman Catholic Church, a towering neo-Gothic dark-stone structure at 330 West 14th Street, dating from 1875. Replete with pointed windows and twin towers topped with short, spiky spires, the church now announces itself bilingually as Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, or Our Lady of Guadalupe at St. Bernard’s, the two parishes having merged in 2003. (More of this anon.) Once patronized by the Irish in Chelsea, St. Bernard’s saw its attendance dwindle as the Irish moved out. The Archdiocese explained the merger with candor: St. Bernard’s had space but lacked bodies, while Our Lady had bodies but lacked space (and they both had debts). But access to the church is up a steep short flight of steps, since neo-Gothic had little awareness of the handicapped.

Beyond My Ken But the dominant presence on the block is St. Bernard’s Roman Catholic Church, a towering neo-Gothic dark-stone structure at 330 West 14th Street, dating from 1875. Replete with pointed windows and twin towers topped with short, spiky spires, the church now announces itself bilingually as Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, or Our Lady of Guadalupe at St. Bernard’s, the two parishes having merged in 2003. (More of this anon.) Once patronized by the Irish in Chelsea, St. Bernard’s saw its attendance dwindle as the Irish moved out. The Archdiocese explained the merger with candor: St. Bernard’s had space but lacked bodies, while Our Lady had bodies but lacked space (and they both had debts). But access to the church is up a steep short flight of steps, since neo-Gothic had little awareness of the handicapped. Beyond My Ken At Eighth Avenue and 14thStreet we find two monumental Greek temples whose classical features say “bank.” The copper-domed structure on the northwest corner has a white-marble façade with Corinthian columns. Built in 1897 as the New York Bank for Savings, over the years it underwent a number of changes; served me in one of my bank’s many incarnations; later housed Balducci’s, a legendary Italian grocery in the Village; and is now a CVS pharmacy. One can question whether majestic neoclassical features are appropriate for the intake and output of moneys, but to my mind a grocery or a pharmacy is definitely pushing it.

Beyond My Ken At Eighth Avenue and 14thStreet we find two monumental Greek temples whose classical features say “bank.” The copper-domed structure on the northwest corner has a white-marble façade with Corinthian columns. Built in 1897 as the New York Bank for Savings, over the years it underwent a number of changes; served me in one of my bank’s many incarnations; later housed Balducci’s, a legendary Italian grocery in the Village; and is now a CVS pharmacy. One can question whether majestic neoclassical features are appropriate for the intake and output of moneys, but to my mind a grocery or a pharmacy is definitely pushing it. Beyond My Ken Across 14th Street on the southwest corner of the intersection is another impressive Greek temple that likewise suggests a bank. Built in 1907 for the New York County National Bank, it too has suffered a series of incarnations over the years and recently housed a spa for men. If a grocery and a pharmacy are questionable, what can one say of a spa? Flanked by two soaring Corinthian columns, the façade is topped by a pediment with a spreadwinged eagle, presaging laser hair removal on the grand scale, epic pedicures. But that is in the past; the building is now available for lease, with more flux in the offing.

Beyond My Ken Across 14th Street on the southwest corner of the intersection is another impressive Greek temple that likewise suggests a bank. Built in 1907 for the New York County National Bank, it too has suffered a series of incarnations over the years and recently housed a spa for men. If a grocery and a pharmacy are questionable, what can one say of a spa? Flanked by two soaring Corinthian columns, the façade is topped by a pediment with a spreadwinged eagle, presaging laser hair removal on the grand scale, epic pedicures. But that is in the past; the building is now available for lease, with more flux in the offing.Moving east from Eighth Avenue, at no. 229 on the north side of the street, one sees a churchlike façade and, next to it, stairs rising to a parlor-floor entrance. Passing it many times on a bus, I got the impression that this was a nunnery, a religious house sealed off from the bustle of 14th Street and immersed in appropriate devotions. And of course I was wrong. This was, until 2003, the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe, an 1850 brownstone converted to a Catholic church in 1921 to serve the Spanish-speaking residents of the neighborhood (which had once been known as Little Spain). Its Spanish Baroque façade is rare, probably unique, in the city, and the church’s name commemorates the Virgin of Guadalupe, who appeared to a Mexican peasant in 1531 and has since been much venerated in Mexico.

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My KenBy the early 2000s the little church could no longer accommodate the growing population of Mexican immigrants, so in 2003 the parish merged with St. Bernard’s, a short block to the west. But that short block seemed long to many. While the Caribbean Hispanics who worshiped at the little church welcomed having a seat at Mass at St. Bernard’s, many knew they would miss Our Lady’s warmth and intimacy, its unique Latino “feel.” Just as, at St. Bernard’s, some of the elderly non-Hispanic parishioners were likewise grumbling about the necessary change, as the church was refurbished and “Hispanicized” to make the newcomers feel more at home. Bright colors were added, and a painting of the Blessed Virgin of Guadalupe was installed in front of a mosaic portrait of St. Bernard above and behind the main altar. Flux again, pleasing to some and disturbing to others. The abandoned little church is locked up tight now, with a bilingual sign, WE MOVED.

At no. 225, on the north side of West 14thStreet, one finds the 14th Street Framing Gallery, a custom framing shop that shows the works of artists in its window and thus doubles as a gallery. My friend John once took me there to see the paintings of an artist friend of his, Scott Rigelman, who is often displayed there. Though Rigelman also does bucolic scenes and still lifes, what I saw in the window were urban industrial scenes often devoid of people and with a hint of Edward Hopper’s haunting loneliness. Rigelman calls these works “industrial,” but don’t look for workers or machinery in action, just looming buildings, static scenes. John describes his friend’s work as “cool” and “analytic,” as opposed to “emotional” and “romantic,” an appraisal that strikes me as accurate.

Rigelman’s work finds its audience, for in the last several years he has sold some 45 paintings on 14th Street, many of them impulse purchases by patrons who just happened by, though many of them have then become repeat customers who seek his work out at the Framing Gallery. And when the set decorator for the film Learning to Drive walked past and by chance saw Rigelman’s work, he was so taken with it that he acquired two paintings to use in the film. Two of Rigelman’s paintings are currently displayed, both industrial, studies in brown and gray with a touch of dull red, their subdued quality contrasting sharply with paintings by other artists in the window who strive for warmth and color – something for every taste. But who would have thought? Art on West 14thStreet!

Just beyond the Framing Gallery, at no. 219, we leave religion and art behind as we encounter We the People, a self-styled debt-relief agency that proclaims in bold letters

DIVORCE $499INCORPORATIONS $399BANKRUPTCY $499WILLS $199

Bargains indeed. To which their card adds in fancy lettering, “Rest in Peace.”

Beyond My Ken On the southwest corner of 14thand Seventh Avenue is a five-story red-brick building built in 1888-89, its front entrance flanked by caryatids and topped by a balcony guarded by griffins. I confess that I have been by it often without noticing the entrance, much less the white stone statue above it, which stands out in sharp relief against the dark red brick and the brownstone trim. The statue, I now learn, is of Joan of Arc, for the building was once known as the Jeanne d’Arc and was favored by French visitors. Another 14th Street surprise.

Beyond My Ken On the southwest corner of 14thand Seventh Avenue is a five-story red-brick building built in 1888-89, its front entrance flanked by caryatids and topped by a balcony guarded by griffins. I confess that I have been by it often without noticing the entrance, much less the white stone statue above it, which stands out in sharp relief against the dark red brick and the brownstone trim. The statue, I now learn, is of Joan of Arc, for the building was once known as the Jeanne d’Arc and was favored by French visitors. Another 14th Street surprise.On the southeast corner of 14thand Seventh Avenue, at no. 154-160, is a 12-story loft building dating from 1912. I have been past that building hundreds of times, and into the second-floor J.P. Morgan Chase branch a dozen times, without ever noticing the lavish polychrome terra-cotta decoration by architect Herman Lee Meader adorning it on many levels, though masked now by scaffolding. Meader had visited Mayan sites in Yucatan (I know those sites), and some see a trace of Mayan influence in the scrolls and wiggles and curlicues of the decoration here. Only recently have I discovered terra cotta in New York and (better late than never) fallen in love with it. Again, who would have thought? Mayan art embellishing J.P. Morgan Chase on brash and bustling West 14th Street! Yet another 14th Street surprise.

Beyond My Ken

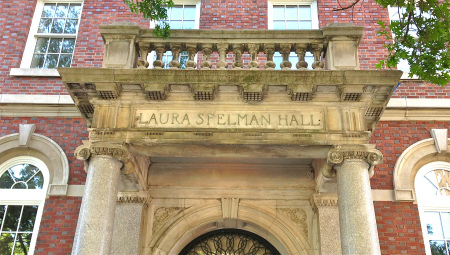

Beyond My KenThe imposing seven-story building at 138-146 West 14th Street, now housing the Manhattan campus of Pratt Institute, is a Renaissance Revival loft building dating from 1895-96. Eight monumental arches frame the windows of the lower floors, while the seventh floor features sixteen smaller arches under a crowning stone cornice. There is rich stone and terra-cotta ornamentation throughout, including palmettes, lion’s heads, and rosettes. This structure introduces a note of grandeur into our walk and definitely redeems 14th Street from the drab commercial hodgepodge it seemed at first to be.

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken Beyond My Ken More grandeur presents itself at 120-130 West 14th Street, where the Salvation Army’s Territorial Headquarters rises massively, a masterpiece of Art Deco style completed in 1930. I confess to having walked or ridden past it countless times without giving it a wisp of attention until, recently, my growing interest in New York architecture sparked an awareness of it as perhaps the most hugely magnificent structure on 14th Street. The most arresting feature of the asymmetrical three-building complex is the deep grotto-like entrance with a stepped concrete façade with curtain-like folds.

Beyond My Ken More grandeur presents itself at 120-130 West 14th Street, where the Salvation Army’s Territorial Headquarters rises massively, a masterpiece of Art Deco style completed in 1930. I confess to having walked or ridden past it countless times without giving it a wisp of attention until, recently, my growing interest in New York architecture sparked an awareness of it as perhaps the most hugely magnificent structure on 14th Street. The most arresting feature of the asymmetrical three-building complex is the deep grotto-like entrance with a stepped concrete façade with curtain-like folds. Guarding the entrance are great gilt metal gates that seem always to be locked tight shut, sometimes with several homeless people sprawled or huddled in front of them. Peering through the gates, one gets only a glimpse of monumental stairs mounting to the left and right, leading to a spacious interior. Clearly visible on the wall in back of the grotto are the words of the Army’s English founder, William Booth:

While women weep, as they do now, I’ll fight.While men go to prison, in and out,In and out, as they do now, I’ll fight.While there is a drunkard left,While there is a poor lost girl upon the streets,While there remains one dark soul without the light of God,I’ll fight – I’ll fight to the very end.

And on the wall high above those words is the Army’s crest, a circular rising-sun motif topped with a crown and containing the Army’s motto BLOOD AND FIRE, signifying the blood of Jesus and the fire of the Holy Spirit.

Just across West 14th Street from the Salvation Army complex, at no. 125, looms another massive building of unlovely brick and glass, housing the McBurney YMCA, which moved here from 23rd Street in 2002. Sharing the site above the Y is a residential complex known as Armory Place, its name commemorating the National Guard armory that formerly occupied the site. The McBurney Y prides itself on its famous members. The world of finance was changed forever when Merrill met Lynch in its swimming pool at another site in 1913, and author William Saroyan stayed in a guest room in 1928. Other members have included playwright Edward Albee, artist Andy Warhol, and actor Al Pacino, and the very thought of them all in the pool simultaneously – which probably never happened – thrills me to the quick. A virtual tour of today’s facility shows both sexes running or cycling in place, lying flat on mats lifting heavy weights, playing basketball, and executing slow-motion movements worthy of ballet; one feels sweaty and tired just from watching. Membership includes free towels and WiFi, and free supervised child watch. If the Salvation Army is a quaint and charming – and most necessary – throwback to another age, the McBurney is as tech-savvy and with-it as they come.

On the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 14th Street is a new building I love to hate: the New School University Center, a 16-story boxy monstrosity with a skin of horizontal brass bands artificially aged to acquire a “dark golden-brown hue” (they look gray to me), and an “innovative stair system” providing a “grand avenue,” glass-encased, that creeps up the sides of the building, its space meant to provide students with “informal interaction.” I don’t know which I hate more – those horizontal strips or the exposed staircases, the brass or the glass – but I’m sure that the students, without architectural stimulus, will manage plenty of informal interaction on their own. Granted, the building is innovative and eye-catching, and far from dull. But I still detest it, and it’s good to have something to detest; it keeps you from getting bland.

MusikAnimal

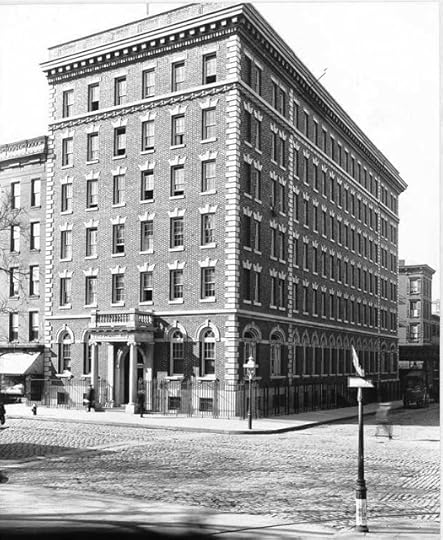

MusikAnimalFinally we come to Union Square, whose name, by the way, has nothing to do with the massive pro-Union rallies held there at the outbreak of the Civil War, or the countless labor-union rallies held there subsequently; it simply reflects the convergence there of the old Bloomingdale Road (now Broadway) and the Bowery Road (now Fourth Avenue). By the mid-nineteenth century the Square, once a potter’s field, had become an exclusive upper-middle-class residential neighborhood whose homes faced a nicely laid-out park with tree-lined walks and a fountain. By the 1870s, as was always the case in a fast-growing city, the neighborhood was being invaded by commercial enterprises – hotels and pharmacies and pianoforte showrooms – and gentility fled elsewhere.

George Washington in Union Square Park.

George Washington in Union Square Park.Aude

Then and now, Union Square has been the scene of labor-union rallies, and protests and demonstrations of every stripe and hue, including a May Day rally and several Occupy Wall Street demonstrations that I have chronicled in this blog. Also chronicled is the Union Square Greenmarket, the granddaddy of all greenmarkets, which I visit regularly on Wednesdays throughout the year. Frequenting the Square are artists displaying their works (some amusing, some garish); folk singers, some of them more screechy than harmonious; chess players looking for an opponent; a turbaned African-American woman displaying assorted wares on a sumptuous cloth by a fountain; and, newly arrived, a young Hare Krishna devotee with the requisite shaven head and orange robe. Witnessing all the to-do are four bronze statues dedicated to advocates of freedom: a mounted Washington, one arm outstretched, heroically surveying his surroundings since 1856; a nobly posed Abraham Lincoln, dedicated in 1870; a bigger-than-life Lafayette, installed for the 1876 Centennial; and a spectacled and skinny Mahatma Gandhi, who since 1986 has been seen walking with a staff in an enclosed little garden near the southwest corner of the park.

Then and now, Union Square has been the scene of labor-union rallies, and protests and demonstrations of every stripe and hue, including a May Day rally and several Occupy Wall Street demonstrations that I have chronicled in this blog. Also chronicled is the Union Square Greenmarket, the granddaddy of all greenmarkets, which I visit regularly on Wednesdays throughout the year. Frequenting the Square are artists displaying their works (some amusing, some garish); folk singers, some of them more screechy than harmonious; chess players looking for an opponent; a turbaned African-American woman displaying assorted wares on a sumptuous cloth by a fountain; and, newly arrived, a young Hare Krishna devotee with the requisite shaven head and orange robe. Witnessing all the to-do are four bronze statues dedicated to advocates of freedom: a mounted Washington, one arm outstretched, heroically surveying his surroundings since 1856; a nobly posed Abraham Lincoln, dedicated in 1870; a bigger-than-life Lafayette, installed for the 1876 Centennial; and a spectacled and skinny Mahatma Gandhi, who since 1986 has been seen walking with a staff in an enclosed little garden near the southwest corner of the park.Coming soon: New York Hustlers: Elmos and Minny Mice, topless cuties, CD hustlers, fake Buddhist monks, the Naked Cowboy and Cowgirls, and how a wiseguy teenager from the West Side made hundreds of dollars on weekends as an action bowler.

Available now: For a preview of my new book, a collection of posts from this blog, just google the title; the table of contents will give you an idea of what’s in it. Available online from the usual suspects: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc. The e-book, now in preparation, will also be available soon. If you go to Amazon and type in the title, you may not find the book, but typing my name will get you to it; Barnes & Noble poses no problem. If you have the preview on your screen, you'll see them both listed on the left; click on either and you'll also find the book. And if the book doesn't interest you, no problem; it will find its readers in time.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on September 13, 2015 04:40

September 6, 2015

196. New York and the Gauls

Officers and crew of an arriving French warship are showered at the dock with tricolor cockades and lusty renditions of the Marseillaise. When, some weeks later, the French ship exchanges gunfire with a British frigate off Sandy Hook, boatloads of watching New Yorkers hail the French victory, and when a whole French fleet then by chance appears, it is greeted at the Battery by thousands of New Yorkers, and women collect linen to make bandages for wounded French sailors. More parades follow, with workers in liberty caps marching arm-in-arm with French officers, coffee house toasts to the French army and navy, more lusty renditions of the Marseillaise, and spirited dancing of the carmagnole, a wild dance danced by Revolutionary mobs in the streets of Paris, including around the guillotine. And all this in a supposedly neutral U.S., while the French and British fight it out abroad.

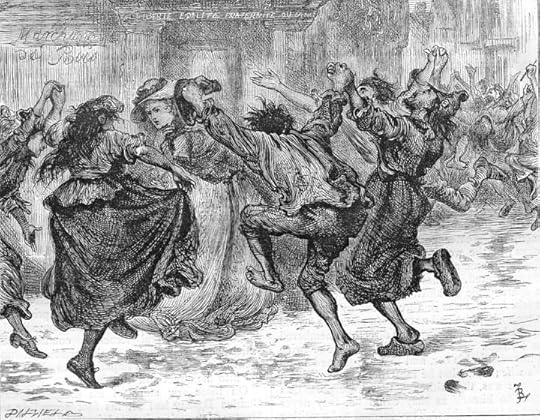

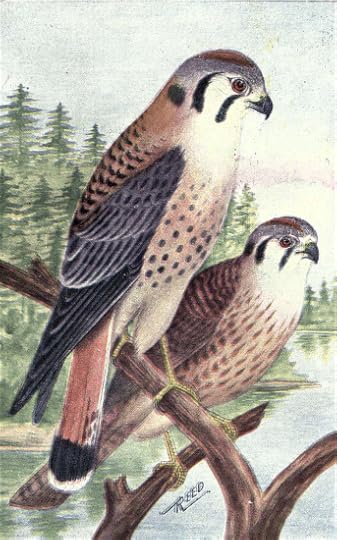

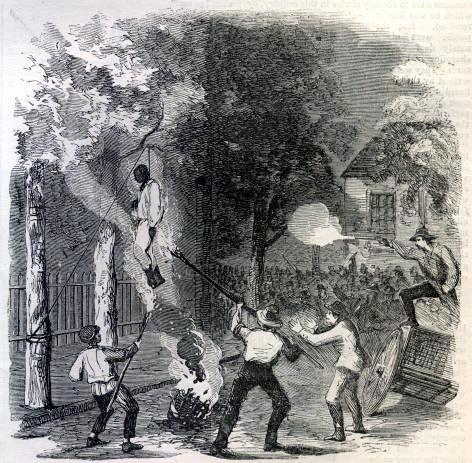

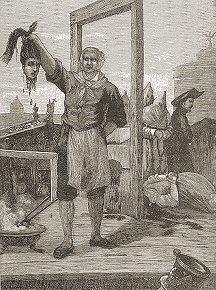

The carmagnole, as imagined by a Victorian illustrator of Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, 1870. A respectable English lady is surrounded by wild dancers embodying what Tennyson called "the red

The carmagnole, as imagined by a Victorian illustrator of Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, 1870. A respectable English lady is surrounded by wild dancers embodying what Tennyson called "the redfool fury of the Seine." Many Americans of the 1790s saw it differently.

Nor does fashionable society hold aloof. The most refined ladies and gentlemen bandy about French expressions and develop a taste for French food, French music, and French mattresses. (The latter bears looking into.) Boarding houses become pensions and fancy taverns restaurants (a new word imported from France), wives appear in low-cut gowns and gauzed coifs à la française, and husbands reject powdered wigs, knee britches, and shoe buckles – so old hat and deplorably ancien régime – for daringly revolutionary pantaloons. Regardless of official neutrality, in New York City liberty, equality, and fraternity are most definitely in.

Old style.

Old style. New style. Such was the Gallomania that raged in this city in 1793-95, when the newly hatched Democratic-Republican Party (now the Democratic Party) espoused the principles of the new French Republic, while the conservative Federalists – now on the defensive in New York – deplored the excesses of Robespierre & Co. and maneuvered to avoid another war with Great Britain.

New style. Such was the Gallomania that raged in this city in 1793-95, when the newly hatched Democratic-Republican Party (now the Democratic Party) espoused the principles of the new French Republic, while the conservative Federalists – now on the defensive in New York – deplored the excesses of Robespierre & Co. and maneuvered to avoid another war with Great Britain.Adding at the time to the French presence in New York were a stream of émigrés whom the turbulent events in France had driven to these more tranquil shores: Bourbon loyalists, constitutional monarchists, and republicans – a bit of a political hodgepodge, but all of them fearful of Madame la Guillotine. Among them were assorted aristocrats; Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, not yet the skillful diplomat who would serve so many regimes; the author Chateaubriand; and Prince Louis Philippe of the junior Bourbon line and a future king of France. A colorful bunch, many of whom, to earn their living in exile, were soon reduced to teaching French or dancing or music or fencing, or becoming jewelers, furniture makers, booksellers, watchmakers, and such, an experience that in the long run instilled in most of them a deep yearning for la patrie, no matter who governed it, as long as the guillotine no longer threatened.

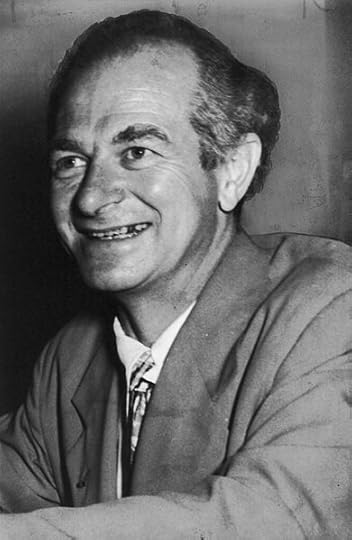

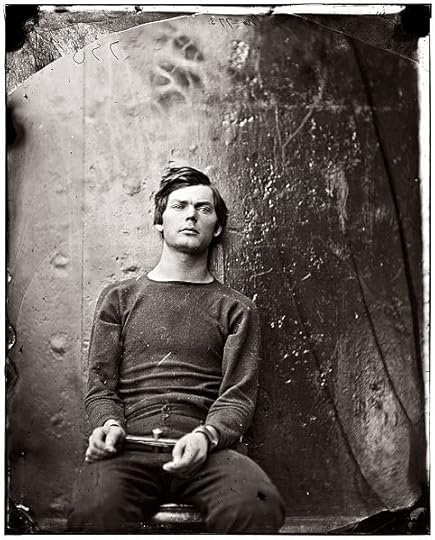

Citizen Genêt. He evidently liked

Citizen Genêt. He evidently likedbeing seen in profile. But one arriving Frenchman – just one – soon made himself less welcome: Edmond Charles Genêt, the Republic’s first ambassador to the U.S., who, having been wined and dined elsewhere, expected a hero’s welcome in the city. Unfortunately, Citizen Genêt had already flouted the nation’s policy of neutrality by commissioning American privateers to prey on British shipping and so prompted President Washington’s cabinet to ask the French government to recall him. He did garner some invitations in New York, but hardly the reception he had hoped for, and when the Jacobins took power in France, they were glad to invite Citizen Genêt back home. Fearing that complying might result in the parting of his head from the rest of him, he wisely applied for, and was granted, asylum here, where he remained for the rest of his republican life, marrying a New York governor’s daughter and becoming a gentleman farmer on an estate overlooking the Hudson River.

Such were Franco-American relations in the mid-1790s, but the French presence in New York went all the way back to the city’s beginnings. Being eager to found a settlement in North America and launch what they hoped would be a vastly profitable commercial enterprise (the New World always induced glowing visions of wealth), in 1624 the Dutch West India Company had managed to enlist for this risky undertaking a group of young French-speaking Walloons of both sexes who, being Huguenot exiles from the Spanish Netherlands (now Belgium), were uprooted and desperate enough to leave the comforts of Amsterdam for the rigors of a distant wilderness named Manhattan. So right here from the start, long before the Anglophones arrived in force, were the French. Or at least, French-speaking Walloons from just north of what was then, and now still is, la Belle France. Coming here as fugitives from religious persecution in another country, they established a pattern that would be repeated often in the city’s history.

(An aside: Should Belgium, or at least the half of it inhabited by French-speaking Walloons, be a part of la Belle France? Opinion has always been divided, nor would Belgium, I suspect, split though it is between Walloons and Flemings, care to lose its independence. But General de Gaulle, whose fondness for “les Anglo-Saxons” was well known, reportedly once remarked, “Belgium is a country invented by the British to annoy the French.”)

As New Amsterdam grew and flourished, more Huguenots came from various European countries until, by 1640, they constituted about a fifth of the population. When persecution in France intensified, climaxed by Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, more French Huguenots, many of them merchants and skilled craftsmen, arrived in New York and prospered, including refugees from the former Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle who then founded New Rochelle in what is now Westchester County. And if, by the eighteenth century, the French language was heard less and less in the city, it’s because the French Huguenots had assimilated so successfully that they ceased to exist as an ethnic group; many, in fact, became Anglicans. Score one—tentatively -- for the Brits.

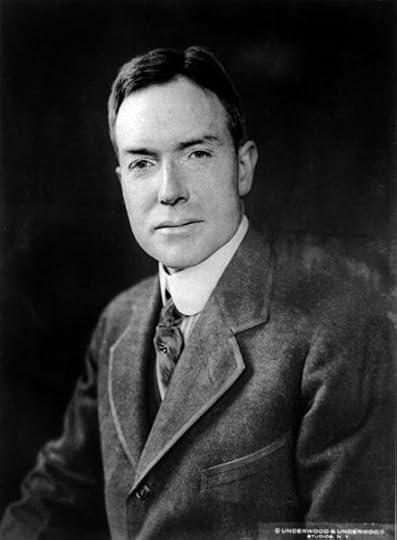

Lafayette, circa 1824. But the arrival of General Lafayette in New York in August 1824 sparked a revival of Gallomania, albeit focused on one individual, the ageing hero of the Revolution in whom many saw a last frail link to the heroic days of Washington and Valley Forge. Thousands of New Yorkers jammed the Battery to greet him as he arrived escorted by a flotilla of steamboats, and mounted buglers led the procession that took him up Broadway, amid cheers and a rain of flowers, to a reception at City Hall. Over the next few days state dinners, receptions, and a visit to the Navy Yard followed, as well as a magnificent reception at Castle Garden where six thousand guests danced until two in the morning. There were also meetings with clergy, militia officers, and delegates from the French Society and the New York Historical Society – this last especially appropriate, since the marquis (a title he had actually renounced) was a walking bit of history, albeit an elderly one and somewhat lame.

Lafayette, circa 1824. But the arrival of General Lafayette in New York in August 1824 sparked a revival of Gallomania, albeit focused on one individual, the ageing hero of the Revolution in whom many saw a last frail link to the heroic days of Washington and Valley Forge. Thousands of New Yorkers jammed the Battery to greet him as he arrived escorted by a flotilla of steamboats, and mounted buglers led the procession that took him up Broadway, amid cheers and a rain of flowers, to a reception at City Hall. Over the next few days state dinners, receptions, and a visit to the Navy Yard followed, as well as a magnificent reception at Castle Garden where six thousand guests danced until two in the morning. There were also meetings with clergy, militia officers, and delegates from the French Society and the New York Historical Society – this last especially appropriate, since the marquis (a title he had actually renounced) was a walking bit of history, albeit an elderly one and somewhat lame.

Indeed, one wonders how the frail sixty-seven-year-old survived the patriotic frenzy inspired by his visit – a celebratory frenzy such as he had never experienced in his own country, where monarchists and republicans alike viewed him, a moderate who had advocated a constitutional monarchy, with suspicion. Even more challenging was the thirteen-month tour by stagecoach, canal boat, horseback, and steamboat that took him to all twenty-four states of the Union, in each of which he was received tumultuously with a hero’s welcome. New Yorkers were as greedy as anyone for a piece of the old general, whose image appeared on sashes, badges, gloves, programs, vases, banners, and bowls. Busy with his exhaustive and exhausting tour, during which he met for the last time with white-haired veterans of the Revolution, he was back in New York in July 1825, and in a speech on Independence Day hailed the “prodigious progress of this city.” In September he wound up his tour with a last visit to the capital and left from there for France. He was surely the most popular Frenchman to ever tread these shores; not even Charles Boyer came close.

With the end of the second war with Great Britain in 1815, the port of New York resumed trading with all the major ports in the world, not the least of which was Le Havre. And what came from there? “Fancy goods,” meaning silks, ribbons, laces, gauze scarfs and tassels, pearl buckles, shawls, embroidered bead bags, embroidered silk stockings, and, rushed across the Atlantic by the speedy packet boats of the time, the latest hats and bonnets from the trend-setting modistes of Paris. Obviously, these were luxury items intended for the fashionable women of New York, who each year were the first to learn of, and adopt, the latest Parisian styles. From Britain came such plebeian but necessary items as hammers, nails, scissors, thimbles, pincers, shovels, fishhooks, dustpans, and spittoons, but from France came all the frills and adornments required by the queens of fashion. Serving them were milliners and dressmakers who subscribed to French fashion magazines and maintained correspondents in Paris who sent them dolls dressed in the latest styles; often, to mask their working-class and sometimes Irish origins, they even adopted the fanciest of French names. And so it went throughout the century.

A startling new innovation from France came in 1856, when the Empress Eugénie, the Spanish-born consort of the Emperor Napoleon III, adopted the latest marvel of contemporary technology, the hoopskirt. There were two stories – neither verifiable -- explaining her sudden infatuation with this new contraption: she wanted to hide (1) her bad legs or (2) her pregnancy. In either case she was the queen of contemporary fashion, her portrait displayed in shop windows throughout Europe and North America, and whatever style she adopted, female multitudes were quick to embrace.

The Empress in the new style, 1854.

The Empress in the new style, 1854.Other names for this new phenomenon were “steel skirts” and “skeleton skirts,” for the hoopskirt was made of flexible steel rings suspended from cloth tapes. Many women hailed its domed magnificence as freeing them from layers of hot and heavy petticoats, for it was lightweight and comfortable, even though its typical three-yard width made negotiating doorways difficult. It was caricatured and satirized at the time, but New York factories were soon producing up to four thousand hoops a day, and even servant girls were tempted to essay the new style, which they saw sumptuously displayed in the Journal des Demoiselles and Les Modes parisiennes. The style prevailed for a good ten years or so, until the Empress decided that it had had its day, and began transitioning to the next new style, the bustle. Eugénie’s influence in fashion persisted even after the collapse of the Second Empire in 1870, which sent her and the Emperor into exile, for when the Panic of 1873 hit New York and prices plunged, New York newspapers featured ads proclaiming “French Empress cloths reduced.”

Le Journal des Demoiselles, 1857. Mother, daughter, and doll, all hooped.

Le Journal des Demoiselles, 1857. Mother, daughter, and doll, all hooped.Not all the New York dressmakers were Americans flaunting fancy French names, for the real article flourished here as well, and not without criticism, as seen in the comments of one observer in 1864, quoted in Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, volume 9:

The city is full of harpies from the Rue du Bac and the Chausee [sic] d’Antin – shrivelled, snuffy, toothless old French milliners and dressmakers ‘played out’ in their own country, who have taken ship at Havre and crossed the Atlantic to prey on the credulous and prodigal daughters of the West. You shall rarely walk ten yards along Broadway in its ‘uptown’ section or turn into one of the streets branching from it into Fifth Avenue without coming on a glass full of French bonnets – without seeing those emblems of riotous luxury, perched on stands, in the parlor windows of private houses – or without being made aware through the medium of a flaunting show board, in French, that Madame Harpagon de la Cruchecassee, or Mademoiselle Sangsue [Miss Leech], or Fredegonde, Athalie, Jezebel et Compagnie, Modistes de Paris, dwell on the first or second floor. Beware of Harpagon, she will skin you alive. Avoid Sangsue, she will suck the life blood from you. But the belles of New York will not beware of, will not avoid these snares.

I suspect a bit of bias on the part of the commentator, and seriously doubt that the French milliners and dressmakers of New York were shriveled and toothless; on the contrary, they were probably stylish, attractive, and most accommodating.

It wasn’t just in female fashions that the Second Empire impinged on New Yorkers. In the 1860s the mansard roof became all the rage, causing Greek Revival houses and brownstones to crown themselves with sloping roofs and discreetly protruding dormer windows. The affluent residents of those homes dined often, and lavishly, at the Delmonico’s on 14th Street, where the menu was completely in French, and those deficient in the language of the Franks depended on the obligingness – and the mercy – of the waiters, who glided noiselessly over thick carpets without a hint of flurry or worry.

Meanwhile in the window of Tiffany & Co. on Broadway imports of a different kind had often been displayed: diamonds from the girdle of Marie Antoinette and, at a later date, gems obtained from titled French families fleeing the revolution of 1848. And as this loot came westward to the New World, the New World in exchange exported to Paris its miscreants, as for example Boss Tweed’s cronies in the wake of revelations of colossal fraud in the construction of the new county courthouse. For whenever a New Yorker found it expedient to decamp from Gotham, nothing so lured him as the fleshpots of Paris.

A French import of a different kind was the arrival, in 1876, of the hand and torch of a projected Statue of Liberty, to be seen in Madison Square prior to its display at the centennial of American independence in Philadelphia. This fragment was the forerunner of the whole giant neoclassical statue, the work of sculptor Auguste Bartholi, which a group of French republicans wanted to erect in the United States as a symbol of the ideal republic they hoped to establish in France. And why over here, rather than in France? Because in France the diehard monarchists might vandalize it. So it was destined for Bedloe’s Island, where it would be visible to every vessel arriving in New York harbor. Fundraising proceeded in both France and America, but here, in the wake of the Panic of 1873 and the depression that followed, it proved difficult. “No true patriot,” announced the New York Times, “can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances.” (She wasn’t bronze, by the way, but had copper skin with iron supports.) Finally an appeal to the American public brought in a vast number of small donations in the 1880s, and the statue, built in France, was shipped across the Atlantic in crates, and assembled on its pedestal on Bedloe’s Island. In 1886, amid much civic brouhaha, the completed statue was dedicated by President Grover Cleveland.

As she stands today.

As she stands today.Andrew Maiman

Now let’s zoom ahead to the twentieth century and a personal note. In 1919, soon after the end of World War I, my mother was sent to Paris by the YWCA to work in the Foyer, a YWCA center offering English classes and other services to young French women. “To be an American in Paris in 1919,” she often told me, “was to be a god.” Our entering the war in 1917, when the French and their British allies were exhausted after years of trench warfare, had brought energy and hope to the Allies, and for this and the victory that followed, the French were profoundly grateful. In her year and a half in Paris my mother, unencumbered by any solid grasp of the language, made many French friends and acquired a taste for France and things French that remained with her all her life. When, in 1940, Paris fell to the Germans and French resistance collapsed, I remember my mother’s dismay, and her concern for French friends living in Paris. When her younger son started grade school, she saw to it that he took French, thus instilling in him a similar taste for things French that in time would take him to France with a Fulbright scholarship, and cause him, an English major, to study French language and literature in graduate school and end up teaching French.

The love affair between the two republics was put to the test in the years following the end of World War II, for France no longer enjoyed the status of a world power, while the U.S. had become one of the two superpowers, confronting the Soviet Union. The result: wounded French pride vs. American arrogance – not the best formula for friendship. And American arrogance was a fact. In a youth hostel in Italy I remember a brash American telling a cultivated young French woman, “France is done, finished, kaput!” – an opinion that struck me then, and still strikes me now, as ignorant, stupid, and naïve. Of course, in the years that followed, General de Gaulle’s towering presence, with his deep distrust of “les Anglo-Saxons,” didn’t help. “I don’t like that guy,” my students often told me, to which I could only answer, “He doesn’t want you to.” But all was not lost: Marilyn Monroe was celebrated over there, just as Brigitte Bardot was hailed over here.

House of Representatives menu.

House of Representatives menu.leverhart And today? We have survived more ups and downs in the love affair. In 2003, when the French government declined to jump through Bush Junior’s hoop and join in the war in Iraq – a refusal that I cheered at the time – the cafeterias of the House of Representatives stopped serving French fries and served “freedom fries” instead. Just

when Congress seems to have exhausted all possibilities for silliness, it manages to outdo itself again.

In the years before 9/11 I remember hearing a French resident of the U.S. say how exciting it was to live in an adolescent country like this one, as opposed to the more mature nations of Europe. He liked the sense of adventure, the openness to change, the daring – for a cultivated Frenchman, a surprising point of view. What he would say today, in the wake of our response to 9/11 and all that followed, I’d just as soon not know.

Recent events show that, in spite of all, the love affair persists. Early last July a replica of the Hermione, the three-masted, 32-gun frigate that brought the twenty-two-year-old Lafayette to these shores in 1780 (his second visit) with news of French support for our Revolution, sailed into New York harbor, fired a round of cannon blasts by way of greeting, and docked at the South Street Seaport. The mission of the vessel and its volunteer costumed crew, including officers in cocked hats and gold-braided jackets, was to reinforce the somewhat shaky Franco-American friendship by a round of visits to East Coast ports. “There are two things the French and the Americans agree on totally,” the ship’s superintendent observed: “D-Day and Lafayette.” An exhibit at the New York Historical Society featured Lafayette and the Hermione, the reincarnation of which led a parade of vessels past the Statue of Liberty on July 4. On board the arriving vessel was a barrel of Hennessy cognac to be auctioned off in New York, the proceeds going to charity. And where is the Hermione today? Back in its home port of Rochefort, with return visits to the U.S. a possibility.

Recent events show that, in spite of all, the love affair persists. Early last July a replica of the Hermione, the three-masted, 32-gun frigate that brought the twenty-two-year-old Lafayette to these shores in 1780 (his second visit) with news of French support for our Revolution, sailed into New York harbor, fired a round of cannon blasts by way of greeting, and docked at the South Street Seaport. The mission of the vessel and its volunteer costumed crew, including officers in cocked hats and gold-braided jackets, was to reinforce the somewhat shaky Franco-American friendship by a round of visits to East Coast ports. “There are two things the French and the Americans agree on totally,” the ship’s superintendent observed: “D-Day and Lafayette.” An exhibit at the New York Historical Society featured Lafayette and the Hermione, the reincarnation of which led a parade of vessels past the Statue of Liberty on July 4. On board the arriving vessel was a barrel of Hennessy cognac to be auctioned off in New York, the proceeds going to charity. And where is the Hermione today? Back in its home port of Rochefort, with return visits to the U.S. a possibility.A further strain on the relationship came with revelations that the American embassy in Paris was packed with eavesdropping equipment focused on President François Hollande and, for a very French touch, his actress girlfriend who discreetly frequents the Élysée Palace but a few doors away from the Embassy. This keyhole peeping drew an outcry from the French press, though French officials, mindful perhaps of France’s own eavesdropping prowess, were inclined to shrug it off. Said a Foreign Ministry spokesman, “If we criticize the States, it’s because we love the States…. We love Lincoln. We love Kennedy. We love Roosevelt and the New Deal. We love the Founding Fathers. We love the creativity. We don’t like the rifle association.” A New Yorker couldn’t have put it any better.

When an American journalist visited the well-preserved trenches of World War I in northern France last year, he recognized that in that war the Germans had better weapons, better soldiers, better generals, better spies, better barbed wire, and vastly better trenches – in short, better everything – and yet, having repelled French attacks for four years, the Germans managed in the end to lose. How? When he asked elderly residents in the area, people whose memories went back to 1918, their answer was always the same: “Les Américains.”

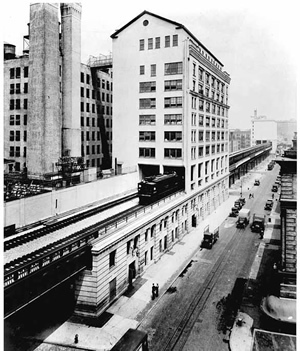

American troops embarked for France, 1917.And recently, when three Americans helped thwart a terrorist attack on a crowded Amsterdam-to-Paris train, thus saving the lives of countless passengers, they received from President Hollande himself France’s highest honor, the Legion of Honor.

American troops embarked for France, 1917.And recently, when three Americans helped thwart a terrorist attack on a crowded Amsterdam-to-Paris train, thus saving the lives of countless passengers, they received from President Hollande himself France’s highest honor, the Legion of Honor.Yes, come what may, the friendship will survive.

Coming soon: 14th Street: from pig ears to Macs, Our Lady of Guadalupe, heroic pedicures, Joan of Arc, Art Deco and terra cotta, how Merrill met Lynch, and a building I love to hate. And after that, New York hustlers.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on September 06, 2015 04:49

August 30, 2015

195. Religion in New York

“We have here Papists, Mennonites and Lutherans among the Dutch and also many Puritans or Independents and many atheists and various other servants of Baal.” So wrote a Dutch citizen of New Amsterdam to officials in Holland in 1655, complaining of the diversity of religious faiths in the colony. He supported Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s attempt to impose the Dutch Reformed faith on the colonists, but the population was too diverse both ethnically and religiously to be made to conform. When the British seized the colony in 1664, they in turn tried to impose the Anglican faith, but with the same result: the city simply could not be made to conform. Right from the start New Amsterdam, and subsequently New York, attracted such a mix of peoples that a policy of mutual tolerance was practiced, with occasional attempts at conformity that never had even a ghost of a chance. Many residents were too busy making money to find time for religion, and those who did find time went their separate ways.

And since then? As of 1990 – the latest comprehensive figures I have access to – the city’s places of worship ranged in number from 471 Baptist, 457 Jewish, 403 Roman Catholic, and 391 Pentecostal at the high end, to 69 Russian Orthodox, 60 Moslem, 40 Greek Orthodox, and finally, at the low end, 3 Quaker and 1 Baha’i. But in the quarter century since, those figures have surely changed, perhaps radically, because, as we shall see, religion in this city is in flux.

Precisely because New York was a place of many faiths – faiths that might squabble among themselves but that didn’t try to wipe each other out -- the city became a place of refuge for the persecuted. New Amsterdam had been founded in 1624 by a group of Huguenot Walloons sponsored by the Dutch West India Company. More Huguenots from the Netherlands and Germany followed, including Peter Minuit, famous for buying the island of Manhattan from the native peoples. By 1650 Huguenots were about a fifth of the settlement’s population, and when, in 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which guaranteed French Protestants certain protections, many more French Huguenots fled the Sun King’s radiating splendor to find sanctuary in New York. So welcoming was the city that the Huguenots assimilated readily; by the eighteenth century, Huguenot merchants numbered among the city’s leaders, and members of the Huguenot community gradually became affiliated with other denominations, especially the Anglican Church. Such is the price of acceptance: loss of identity.

Expulsion of Huguenots from La Rochelle, 1661.

Expulsion of Huguenots from La Rochelle, 1661.World Imaging

Peter Stuyvesant may have cast a sour glance at the Huguenots, but after all, they had long preceded him to New Amsterdam. But when, in 1654, a group of 23 Sephardic Jews arrived, some of them fleeing the fall of Dutch settlements in Brazil to the Portuguese, he put his gubernatorial foot down: the “deceitful race” were barred from buying land or participating in the citizens’ militia, and were invited to depart. But the Jews’ leaders, knowing their rights under the laws of the Dutch Republic, which guaranteed freedom of religion to all, appealed to authorities in Holland, and Stuyvesant’s superiors reminded him that “each person shall remain free in his religion.” He was further advised that certain influential Jews had invested heavily in the Dutch West India Company, which by itself must have settled the matter: the Governor was told to back off.

Peter Stuyvesant may have cast a sour glance at the Huguenots, but after all, they had long preceded him to New Amsterdam. But when, in 1654, a group of 23 Sephardic Jews arrived, some of them fleeing the fall of Dutch settlements in Brazil to the Portuguese, he put his gubernatorial foot down: the “deceitful race” were barred from buying land or participating in the citizens’ militia, and were invited to depart. But the Jews’ leaders, knowing their rights under the laws of the Dutch Republic, which guaranteed freedom of religion to all, appealed to authorities in Holland, and Stuyvesant’s superiors reminded him that “each person shall remain free in his religion.” He was further advised that certain influential Jews had invested heavily in the Dutch West India Company, which by itself must have settled the matter: the Governor was told to back off.But what really ticked Stuyvesant off was the arrival of English Quakers, likewise fleeing discrimination in their homeland. Their aggressive sermonizing and, when moved by the Holy Spirit, their fits of jiggling or quaking (hence their name), invited his disdain. These oddballs, he decided, were a threat to the peace and stability of the colony, and probably crazy as well. When they persisted despite his disapproval, he forbade the settlement of Vlissingen (today’s Flushing, in Queens) to allow their worship, whereupon the townsfolk, all English, signed a remonstrance to the Governor reminding him that Dutch tolerance extended even to Jews, Turks, and Egyptians, in consequence of which they must respectfully refuse to obey. This Flushing Remonstrance of 1657 is now celebrated as a forerunner of the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, but Stuyvesant, not being conversant with said Bill, arrested four of the remonstrating townsfolk and clapped two of them in jail for a month. Only the coming of the British in 1664 ended his antics of intolerance.

So much for religious diversity in New Amsterdam; it was there from the start, though not without fitful challenges. Now let’s fast-forward to the twenty-first century and a vast metropolis that has been fed over the centuries by wave after wave of immigrants. What kind of religions are here today? Using the terms loosely, at first glance I’m tempted to divide New York religion into three categories: High Church, Low Church, and No Church, meaning the more formal and traditional, the more informal and upstarty, and the Great Unwashed.

The people I have socialized and worked with in Manhattan are white middle-class professionals – writers, directors, editors, artists, bank employees, teachers, librarians, chefs, and attorneys – who for the most part fall into the category of No Church, or the Great Unwashed. Some of these No Churchers may never have been touched by religion, but most have fallen away, gently or not so gently, from the faith of their childhood. To really know them, you need to know where they’ve come from religiously, culturally, and geographically. Being No Churchers, they’re the ones who, no doubt, create the impression that New York is a secular city devoid of religion – a place, in fact, where people go to lose their religion, if they ever had any in the first place.

My friend Ed was raised a traditional Roman Catholic in Denver, where he served as an altar boy, and then attended a Jesuit university. When he first came to New York he was an observant Catholic who attended Mass and dutifully went to confession. But then, as the years passed, he became less dutiful, began questioning his faith, and finally fell away completely, even to the point of denigrating it with, I’m sure, no small amount of bitterness. If Catholicism left its mark upon him, it was visible, I think, in his courteous, soft-spoken manner, very reserved; he was not one to give himself emotionally, to yield to impulse. Which reminds me of a French friend whom I knew at Lyons when I was studying in France ; he had attended a Catholic collège, rather than the secular secondary school, the lycée, and showed the same well-mannered, soft-spoken reserve. We can leave our childhood faith, but it won’t necessarily leave us.

My friend John, who is proud of his Finnish descent, was raised a Laestadian Lutheran in Minneapolis and was taken by his mother to a church where the service was in Finnish, of which he understood barely a word. He describes Laestadianism as a freakish, fundamentalist branch of Lutheranism that flourished in northern Minnesota. Its aversion to sin and worldliness went so far as to consider going to movies a sin, as well as alcohol consumption, dancing, and women wearing makeup. When he attended the University of Minnesota, where he majored in English and philosophy, he lost his faith, and upon coming to New York he became a full-fledged atheist and remains one to this day. Religion for him is simply a distant and unpleasant memory from his childhood, something he can do quite easily without. But unlike Ed, he feels no biting resentment, no bitterness. As for me, as a child in Evanston I was exposed to a gentle Methodism, quite liberal, that imposed no catechism or ideology, no ban on movies or dancing, but instead inculcated a few basic concepts of morality, the need for understanding and compassion, as exemplified by the story of Jesus, retold every Easter by a talk with slides, and celebrated every Christmas with a well-attended Nativity pageant, superbly dramatic, in which the whole church participated. Even yours truly was involved, musical illiterate though I was, white-garbed and holding my electric candle high, as the triumphant strains of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus brought the whole attendance to their feet, and the high-school and adult choirs marched down the aisles singing lustily, till our resounding hallelujahs climaxed and closed the performance with a whopping big musical bang.

Because the Methodism I had known was, as I put it, gentle, even in my later – and inevitable – lapsed state, where I felt no immediate need of religion, I nursed no resentment, no bitterness, only warm memories of the Methodists I had known, their principles, their winning love, their faith. At times I ask myself if I have ever encountered anyone who impressed me as being truly spiritual, and always I recall my junior-year Sunday School teacher, Dr. Edmund D. Soper, white-haired and spectacled, soft-voiced, a teacher and scholar with a mellow wisdom. What it was about him that was spiritual I cannot define or describe; it was simply an intangible aura that you sensed. My partner Bob says the same of his mother’s Lutheran pastor in Jersey City, a truly spiritual man such as one rarely encounters today, or perhaps ever.

Only on one other occasion have I personally encountered a truly spiritual human being. While working in the library of the University of San Francisco, a Jesuit school, I heard a talk by Father Martin D’Arcy, the celebrated English Jesuit, a quirky little black-robed man, sharp-featured and ascetic, with a bright eye, a mischievous smile, and a superb sense of humor, and there again I sensed true spirituality. Not in the other priests whom I encountered there – some smooth and clever, some prickly and caustic, some diligent and businesslike – but only in him. His quirkiness was far removed from Dr. Soper’s mellowness, yet they both conveyed spirituality. A rare quality that even the No Churchers have to esteem. If it were less rare, maybe there would be fewer No Churchers. Maybe. And maybe not.

Even if I’m not myself a believer, I respect those who are. Whenever I’m in the Union Square subway station – a huge labyrinth of passageways giving access to any number of subway lines – I give a smile and a friendly wave to the women, often black or Latino, who have a table there with literature and invite people to learn what the Bible really says. They look so committed, and so ignored by the hurrying commuters, that I can’t resist this gesture, which always provokes a warm smile and a friendly wave back. Maybe someday I’ll stop and tell them that I still have the Bible I was given by my mother at age sixteen, a bit decrepit but still usable. (The Bible, not my mother.)

But things aren’t always so simple. When, some years back, I renewed contact by mail with a woman I had dated in junior high and high school, we exchanged several letters and seemed to be beginning a warm and cordial relationship. Living now in Nashville, she told me she attended a Bible-based church and some years ago had experienced a Damascus Road experience similar to that of the apostle Paul. Interested, I asked her to relate it, and finally she did, telling how she had fallen into the blackest of depressions and, desperate, finally surrendered herself to God, following which her depression lifted and she felt a joy like she had never known before.

Conversion of Paul on the road to Damascus, a painting by Hans Speckaert, 1570s. Never was

Conversion of Paul on the road to Damascus, a painting by Hans Speckaert, 1570s. Never was a conversion more dramatic or more crowded; no room for quiet contemplation here.

This account fascinated me then and still does now; not for anything would I dismiss lightly or demean in any way what is obviously the most important event in her life. So far, so good. But after that she urged me to give up being gay – as if it were something you could turn on and off at will – and finally she put the question, “What do you do about Jesus?” I replied honestly, “I leave him alone and he leaves me alone. This way we get along fine.” Which ended the relationship; no more letters, nothing, kaput. I truly regret it, but I’m leery of a faith that cuts you off from others; I know several Catholics who share their faith but don’t try to convert me, and we all have a rewarding relationship.

So much for the No Churchers. So what about the High and Low Churchers? In supposedly godless New York they’re all over the place. For instance:

In a former vaudeville theater in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, some six hundred worshipers leap to their feet to join a Latino band in song, shaking their tambourines. Then a preacher gives a fiery sermon and speaks in tongues, and parishioners with tear-streaked faces raise their arms heavenward, eyes shut, in collective rapture. Nothing quiet or meditative here. It is noisy, it is public, it is passionate. And it is definitely Low Church.

A Pentecostal service.

A Pentecostal service.Peter van der Sluijs

But what is it? It’s the Sunday morning service of the Pentecostal megachurch Aliento de Vida (Breath of Life), founded twelve years ago by the pastor, Victor Tiburcio, and his wife, immigrants from the Dominican Republic. Who are the worshipers? Immigrants from Ecuador and Argentina and El Salvador and Trinidad and Tobago and just about any country in Latin America, some of them legal and some not: ordinary people from the bottom of the social heap who want passion in their services, as well as help in learning English and navigating the complexities, legal and otherwise, of realizing the American dream. So great is the demand for Aliento de Vida’s services, simulcasts are offered by the church’s own TV network.

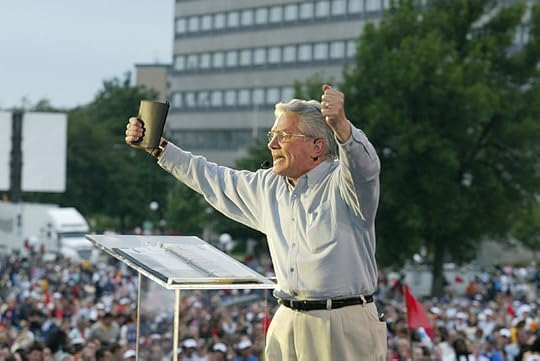

But this is nothing, compared to the Pentecostal festival in Central Park on July 11 featuring Luis Palau, the “Hispanic Billy Graham,” one of the world’s leading evangelical Christian figures, a gathering that drew 60,000 worshipers – the limit allowed on the Great Lawn -- for the largest evangelical Christian gathering in the city since Billy Graham’s crusade in Queens in 2005. Of the 1700 churches participating, 900 were Hispanic, reflecting the surging growth of immigrant-led churches in the boroughs outside Manhattan. Yet participants weren’t just Hispanic, but Korean-American and African-American as well. The mayor himself was present to offer a few welcoming words and get prayed for, and the crowd danced and cheered and leaped and prayed, and listened to white-haired Luis Palau preaching in shirtsleeves in both English and Spanish, as everyone present expressed the collective joy of being Christian and proud of it. And this in the heart of godless New York! Most definitely and exuberantly Low Church.

Luis Palau preaching.

Luis Palau preaching.Asociación Luis Palau

If Pentecostalism is sweeping New York and the nation and much of the Third World, gathering new converts by the thousands and tens of thousands, who is losing out? That most High Church of all High Churches, Roman Catholicism. Some years ago the Archdiocese of New York, faced with declining attendance, aging priests, and mounting maintenance costs, initiated a broad reorganization that led to the closing of dozens of churches in the metropolitan region. Thus Our Lady Queen of Angels parish in East Harlem closed in 2007, and its church on East 113th Street was boarded up. But that’s not the end of the story, for a handful of parishioners refused to accept this change, which some denounced as “betrayal” by the Church, and ever since have met on park benches in East Harlem housing projects to sing hymns and join hands in prayer. They do this every Sunday, despite raucous sounds of children playing and dogs yipping nearby, braving the scorching heat of summer and the icy rigors of winter. Yet the closing of this and other parishes in East Harlem is understandable, since the Puerto Ricans who once filled the pews have left for other parts of the city, replaced by Dominicans and Mexicans who are drawn to the storefront Pentecostal churches that have popped up in the area.

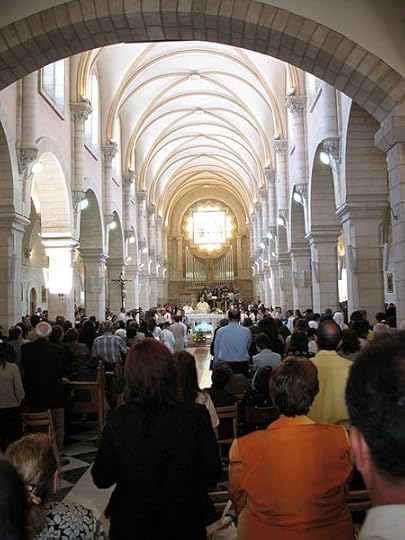

A Roman Catholic Mass. Very High Church, quiet, traditional, dignified.

A Roman Catholic Mass. Very High Church, quiet, traditional, dignified.James Emery And the closings go on. Just recently almost forty Catholic churches were closed in another wave of closings climaxing the biggest overhaul of the diocese in its entire history. At Our Lady of Peace on the Upper East Side, tearful parishioners gathered for a last Mass on Friday, July 31. “This is the beginning of our crucifixion,” said a lifelong member of the congregation, “our Good Friday, the nails driven into the coffin of Our Lady of Peace.” Parishioners of many of the closed parishes have appealed to the Vatican, which will decide their cases after September 1, but in the meantime the archdiocese has denied them any extension that would keep the churches open until the cases are resolved. The mood of gloom and doom contrasts vividly with the exuberant and joyful services of the Pentecostals.

Somewhere between Low Church and No Church are the pagans. Yes, there are pagans in New York City. I used to think of them as weirdos who emerge periodically to celebrate the vernal equinox or some such occasion, half naked or dressed in outlandish outfits, and who then disappear until the next celebration. But they are more organized than that. The Wiccan Family Temple Academy of Pagan Studies at 419 Lafayette Street (between East 4thStreet and Astor Place) offers an introduction to the modern pagan witchcraft religion known as Wicca, with classes in magic, the Greater and Lesser Sabbats, the history of witchcraft, god and goddess archetypes, Shamanism, divination, talismans and amulets, voodoo, the use of spells, and countless other topics. And yes, with the proper training, you can become a witch. But they don’t worship Satan, they simply want to be in tune with nature and its forces.

A pagan handfasting ceremony, celebrating a wedding or betrothal.

A pagan handfasting ceremony, celebrating a wedding or betrothal.ShahNai Network And yes, there are self-proclaimed Satanists too, though often they don’t really believe in Satan or worship him. The Satanic Temple, whose founders hail from Boston but through the Internet have proselytized throughout the country, has been called a sharp thorn in the brow of conservative Christianity. They mean to be a counterforce to President George W. Bush’s White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives, and they do this by launching a religion of Satanism that meets all the Bush administration’s criteria for receiving funds. Their Satanism is really science-based and atheistic, a way of celebrating outsider status, of looking where other people don’t want to look, to find the obscure, the bizarre, the anomalies. But it is often political. If a state allows voluntary prayer in public schools, they propose that Satanic children should be allowed to pray in school… to Satan. And it plans to use the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to oppose abortion waiting periods, arguing that it violates Satanic doctors’ belief in the sanctity of good science. A thorn in the brow of conservative Christianity indeed, but to avoid threats to their families the founders use pseudonyms. With great anticipation I await their intervention here in New York. But I leave it to others to decide whether they should be categorized as Low Church or No Church.

Saint Patrick's, as seen from Rockefeller Center.

Saint Patrick's, as seen from Rockefeller Center.J.M. Luijt

To do justice to my announced theme of religion in New York, I’d have to do a series of posts, a whole book. I haven’t even mentioned Saint Pat’s, the looming Fifth Avenue edifice whose slow beginning in the nineteenth century, with walls rising only as finances permitted, signaled the growing influence of Roman Catholicism in what had hitherto been a WASP city. A prime tourist attraction, it has a souvenir stand inside its sacred walls, which shocks me, a WASP who in his European travels absorbed the notion of the sacredness of Catholic churches, where God is literally present, and souvenir stands are not to be found (not inside, that is, for souvenirs are always to be had). A crypt under the main altar harbors the remains of numerous cardinals and other prominent Catholics, including Archbishop Francis (“Franny” to some) Spellman, whose presence there may or may not be a scandal. (See the much-visited post #136, July 20, 2014).

And if you google “places of worship in New York,” you’ll come up with pictures of the Episcopal Cathedral of Saint John the Divine on Amsterdam Avenue near Columbia University; the Islamic Cultural Center of New York at Third Avenue and East 96th Street, its domed mosque overtopped by a towering minaret; various synagogues; and with a little more poking about, the famous Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem; the Mahayana Buddhist Temple on Canal Street in Chinatown, with an outsized gold statue of a smiling Buddha, his right hand raised in blessing; and the Saint Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral on East 97th Street, its multiple cupolas topped by crosses. And these are only the biggies; there are smaller sites as well, each with a story to tell.

Dazzled by thoughts of minarets, Buddhas, and cross-topped cupolas, I now ask myself what I would most want to see, if visiting an unfamiliar place of worship. The answer comes immediately: I would most want to see something truly holy, something awe-inspiring, something to take me out of myself, something with a touch -- or a punch -- of mystery. And this from a No Churcher!

Coming soon: How New Yorkers spurned powdered wigs and knee britches and took to pantaloons, and the French language preceded English in Manhattan. How fifty thousand New Yorkers -- a third of the city -- turned out to greet a visiting Frenchman (and it wasn't General de Gaulle). Why did the Empress Eugénie adopt the hoopskirt -- what was she trying to hide? And what did Congress have against french fries? All this, and more, under the aegis of the tricolore.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on August 30, 2015 04:24

August 23, 2015

194. Wild New York

A marshy expanse of wetlands where plovers, sandpipers, dowitchers, and yellowlegs scurried across the damp sands at low tide, feeding, while bitterns stood like frozen sentinels, awaiting their prey, and mallard ducks and wild swans glided in the shallows, and eagles and osprey soared overhead, and the skies were darkened in season by migrating flocks of wigeons, oldsquaws, and mergansers. Estuaries teeming with mussels and clams and periwinkles, and oysters in great numbers, some large, some small and sweet, all of them inducing visions of tasty meals. And beyond the shoreline, low hills and towering forests of oak and chestnut and maple with strawberries in the spring, blackberries and raspberries in summer, and in the autumn apples and walnuts and wild grapes. Moving furtively in the brush were deer and wild turkeys, as well as raccoons and otter and quail and, lurking in dark wooded fastnesses, mountain lions and black bears and wolves. The air was clean, the land was lush and green.

Arturo de Frias Marques

Arturo de Frias MarquesA glossy ad luring visitors to some distant, unspoiled Eden, a travel agent’s spiel replete with cooked-up, frothy vistas no place on earth could match? No, simply a realistic description of Manhattan in the early 1600s, when the first European settlers arrived.

And today? I’ll spare you the obvious litany of cluttered urban woes, the cliché depiction of a cacophonous wilderness of asphalt, concrete, steel, and cement. But if you look about and look close, you’ll find that, miraculously persisting, there is still a wild New York. And I don’t mean teen-age gangs, madcap cyclists, screeching ambulances, or the naked cowboy or bare-breasted cuties exposing themselves to tourists in hopes of tips in Times Square. I don’t mean homo sapiens sapiens in any form, but real, wild, living creatures.

jeremy Seto Let’s start with a celebrity predator known to thousands. I mean, of course, Pale Male, a red-tailed hawk whose neck is unusually light in color, giving him his name. He first appeared in the Park in 1991, and since then has nested each spring with his mate of the moment in ornamental stonework high atop a residential building at Fifth Avenue at 74thStreet, just across from Central Park. Pale Male’s marital adventures have always been observed from far below by a throng of eager fans watching anxiously with binoculars and telescopes to see if the young will hatch and survive, as many have done, leaving the nest to reside in Central Park. Pale Male’s consorts have a way of disappearing, often as a result of eating a poisoned pigeon or rat, but Pale Male survives, always taking a new mate that his fans immediately christen: First Love was followed by Chocolate, who was followed by Blue, then Lola, then Lima, then Paula, then Zena, then Octavia, and so it goes.

jeremy Seto Let’s start with a celebrity predator known to thousands. I mean, of course, Pale Male, a red-tailed hawk whose neck is unusually light in color, giving him his name. He first appeared in the Park in 1991, and since then has nested each spring with his mate of the moment in ornamental stonework high atop a residential building at Fifth Avenue at 74thStreet, just across from Central Park. Pale Male’s marital adventures have always been observed from far below by a throng of eager fans watching anxiously with binoculars and telescopes to see if the young will hatch and survive, as many have done, leaving the nest to reside in Central Park. Pale Male’s consorts have a way of disappearing, often as a result of eating a poisoned pigeon or rat, but Pale Male survives, always taking a new mate that his fans immediately christen: First Love was followed by Chocolate, who was followed by Blue, then Lola, then Lima, then Paula, then Zena, then Octavia, and so it goes. Courtesy of PaleMale.com

Courtesy of PaleMale.comIf I say Pale Male is known to thousands, I’m not exaggerating, for he has been the subject of a one-hour documentary film and a book. An aging stud, he is the first hawk known to have nested in the city, and his fans are fiercely loyal. In December 2004, when the board of the co-op where he nested removed the hawks’ nest and the anti-pigeon spikes anchoring it, their action provoked an international outcry. The Audubon Society and the Central Park birdwatching community protested; TV celebrity Mary Tyler Moore, a resident of the building, joined the protest; the media reported the outrage; and passing automobiles, taxis, and even police cars sounded their horns in solidarity. A compromise was reached, a new cradle for the nest was installed, and the hawks began bringing twigs to the nesting site.

The red-tailed hawk, the common resident broad-winged hawk of this area, is a thick-set bird with a wide, rounded tail; it is often seen soaring in circles high above the city. Seen from below, the tail is dark gray, but if seen from above, it is red, giving the hawk its name. I have seen Pale Male only in film, perched with his mate on his nest, where the scrawny young squirmed and bustled, but I have spotted other red-tails perched in trees in Pelham Bay Park. Red-tails have been known to nest on other tall buildings in the city, though none can match Pale Male for persistence and longevity. That the species nests at all in New York is an amazing feat of adaptation, given the numerous threats to it posed by the urban environment: poisoned prey, aggressively hostile crows, and when the hawks swoop low, risk of collision with passing vehicles.

A red-tailed hawk.

A red-tailed hawk.Don DeBold Pale Male is the only creature in this area I know of that has attained celebrity status; other denizens of New York habitats creep, skulk, or soar in anonymity. All the big parks harbor a surprising number of species, and Central Park is second to none. Prowling there by day in the spring, I have seen migrating birds by the score and even occasionally by the hundred in a single day, as well as hordes of termites hatching from decaying logs – a sight welcome to birdwatchers, since it brings hungry warblers down to eye level, as they feast on their teeming prey.

Eastern screech owl. The screech is

Eastern screech owl. The screech is more of a mournful whinny or wail.

Wolfgang Wander But Central Park by night is another story. Years ago, crossing it at night at 72nd Street to attend a poetry workshop on the Upper East Side, I treaded with trepidation, for the city then was rife with crime, streetlamps along my way were few, and my footsteps clicked on the pavement, announcing my presence to any nearby malefactors; the one bit of reassurance was a squad car parked halfway cross the park, Today, however, crime has declined, and venturing into the park at night has become the preferred pastime of a number of hardy and inquisitive souls. A Russian lady in an electric cart comes there nightly to feed peanuts to a bunch of rambunctious raccoons (against park regulations, I’m sure). Owl watchers have a only a precious half hour to spot screech owls, somnolent by day but on the hunt by night, before the gathering darkness renders them invisible. And “mothers” (rhyming “authors”) gather at the Shakespeare Garden to attract moths with a special battery-powered light, so they can marvel at the weird and spectral beauty of these rarely seen nocturnal creatures. (Once, on a tree trunk at High Rock Park on Staten Island, I was privileged to see a sleeping luna moth by day and marveled at its lime-green wings with eyespots and, yes, its weird and spectral beauty.) For all these visitors Central Park by night has a magic all its own, and they revel in its sounds: hoots and rasps of owls, yips of raccoons, and in dead leaves the rustle of white-footed mice.

A luna moth.