Clifford Browder's Blog, page 55

January 6, 2013

41. Rubbing Elbows with the Great and the Famous

Some people are drawn to celebrities like moths to the proverbial flame. But I am not a moth; when informed that there is a celebrity in my immediate vicinity, I am inclined to run the other way. I simply can’t imagine what I could say to them, or what they could say to me. But if you live in Manhattan long enough, sooner or later you’re bound to encounter a celebrity. And if not you, then your friends and neighbors. Here are accounts of such encounters. My friend Ken grew up in South Carolina, but from an early age he was reading The New Yorker and acquiring a smattering of New York sophistication before ever setting foot in the city. Fascinated by Gypsy Rose Lee, who was then at the peak of her career as a stripper, he put together a scrapbook of clippings about her appearances and sent it to her. Flattered, she wrote back and invited him to look her up, should he ever come to the city. In time he did; I knew him as another graduate student in French at Columbia University. Unlike me, Ken adored celebrities and sought them out. By waiting patiently at a stage door for a glimpse of such luminaries, he was rewarded with a shared taxi ride with Gertrude Lawrence, and a rose from Margot Fonteyn. A devoted balletomane, he once asked Rudolph Nureyev for an autograph and was answered with a resounding “Nyet!” Which discouraged him not a bit; he recounted the incident with a dose of humor. Ken’s great experience among the famous came when Gypsy Rose Lee invited him to a cocktail party. Finding myself in Midtown with him, I went with him to her townhouse in the East Sixties and saw him to the door. He promised to give me an account of the party and did so the following day.

Gypsy Rose Lee, being her usual modest self.

Gypsy Rose Lee, being her usual modest self.Library of Congress She lived lavishly; on the walls of her residence were paintings by Picasso, Matisse, Miró, and Max Ernst, reportedly given to her by the artists. Among the guests were a showbiz mother and daughter from Hollywood; a representative of Harper, the publisher about to publish her memoir (which would inspire the musical Gypsy); Gypsy’s sister June Havoc; and the one and only Ethel Merman. Gypsy introduced him with enthusiasm as the young man from the provinces who had sent her a scrapbook of clippings and, nothing loth, he talked to each guest in turn. The mother and daughter told him of amassing a collection of paintings, explaining, “They’re all back in Hollywood, of course.” Where else? thought Ken, not too impressed; you wouldn’t tote them around on your travels. The Harper’s representative was obviously out of his element and glad to talk to Ken, who came with no aura of fame. In the middle of the affair Gypsy got a phone call from someone who claimed to be an old friend. “I have no old friends!” she declared and slammed down the receiver. “How do these people get my phone number?” she then wondered out loud. Later, Ken gave me the answer: “Because she gives it to them, that’s how.” Clearly a formidable presence, a bit intimidating, and very ego-driven. “They want me in Utica!” she announced with contempt, a theater there having invited her to perform. That she should get such an offer showed that she was long past the peak of her career and coasting on memories. “She’ll go,” Gypsy’s secretary told Ken on a later occasion; “she’ll do anything for money.” And go she did. Gypsy’s sister June Havoc was more approachable. When Ken told her that there were many histories of burlesque with fine illustrations, but none with a literate text, and said he would like to write such a history, she encouraged him warmly, as did Gypsy herself, when apprised of the project. Alas, it never got done. The climax of the occasion was his brief chat with Ethel Merman. “Miss Merman,” he said, “I’ve seen you many times on stage. You’re a marvelous success, a great performer at the height of your career. I don’t know what to say to you.” Merman then smiled and said quite simply and, I’m sure, sincerely, “You never get tired of hearing it.” A reminder that if fans need celebrities, celebrities likewise need their fans.

Even in her years at Viking and Doubleday,

Even in her years at Viking and Doubleday,she was a remarkably handsome woman. Another friend of mine, Ed, was an editor at Viking Press, where in 1975 he made the acquaintance of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who came to work there as an acquisitions editor following the death of her second husband, the shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis. New to the editing game, to which she brought stellar contacts and a famous name but no editing experience, she came more and more to depend on Ed as a mentor and they became good friends. At times she invited him to her fifteen-room Fifth Avenue apartment, where they quaffed Dom Perignon champagne. And whenever she wanted to go to a movie and needed an escort, she would phone Ed and ask if he was willing; he always was. He described walking down the street with her and seeing heads turn, as people realized who had just passed; one man even exclaimed, “Fabulous!” In the dark anonymity of the movie house she was offstage at last, no longer a celebrity , just a moviegoer. She would scrunch down in her seat, munch some goodies, and watch the film like any teenager. She seemed to need such moments, savored them. These encounters continued until she left Viking in 1977 for a job at Doubleday.

Opera singers were also in demand. My partner Bob’s mother, a veteran opera goer, once quite by chance encountered the famed Yugoslav singer Zinka Milanov in the ladies’ room at the Met, and took advantage of the situation to get her autograph. Bob himself met Zinka in more formal circumstances, after her retirement, at an autograph session at the Met. “I’ll never forget your singing,” he said, as she supplied the autograph. She smiled and said with a touch of accent, “It is good to remember.” Bob also snagged an interview with Marlene Dietrich in Washington, and Tennessee Williams's autograph on a paper napkin, now framed above his desk, when he heard that the renowned playwright was present in a back room of a gay bar here in the Village. Why on a paper napkin? Because it was the only thing handy for an autograph.

Pavarotti the celebrity in full bloom.

Pavarotti the celebrity in full bloom.But many said that -- alas! -- his voice

was not what it once had been.

Pirlouillit Our downstairs neighbor Hans worked for many years for Herbert Breslin, a publicist and manager who had dealings with many singers and is credited with propelling the tenor Luciano Pavarotti to celebrity status. Hans got to know many famous singers, and when Pavarotti went to China, Hans went along, as did Breslin and his wife. “He doesn’t really need me,” Hans explained. “He just wants to have a familiar face around.” Breslin himself somewhat soured on his protégé in later years; in a published memoir he described the tenor's youthful voice as so beautiful it gave him goosebumps, but said that in his later years as a superstar Pavarotti was vain and lazy, with an appetite for money, women, and food.

Other singers whom Hans came to know included the Brazilian singer Bidú Sayão, whom he visited in Maine for many years after her retirement; Renata Tebaldi, whom he often saw in Italy; the Italian tenor Carlo Bergonzi; and the Spanish soprano Pilar Lorengar. He has anecdotes about all of them, and also about the renowned Hungarian-born conductor Georg Solti and others, and knows of rare performances and rare recordings as well. I have urged him to initiate an opera blog and tell these highly entertaining stories, but I doubt if he ever will.

Jerome Robbins, a terror on Broadway

Jerome Robbins, a terror on Broadwaybut a cordial and timid partner at bridge. Our friend John tells how he terrorized a man who was known as the terror of Broadway. Invited over for bridge by a dancer friend and his partner, John was presented to another guest whose name he caught as Jerry Rubins, a smallish and very elegant man, very composed, with a trim white beard, who would be the fourth at bridge. The three others were novices at bridge, so John, though no expert, became the de facto authority of the occasion. Later in the evening Jerry Rubins, who at the time was John's partner, looked at his hand, didn't know what to do, and exclaimed, "I'm scared!" Then he giggled, as if savoring an emotion unknown to him; the others giggled too.

At the end of the evening John and Jerry were waiting for a taxi they would share uptown.

"Jerry," said John, "I gather from the conversation that you're in the theater."

"Oh yes," said Jerry, "director, choreographer, and stuff like that."

A creeping awareness began to take hold in John's mind. "What did you say your name was?"

"Jerome Robbins."

John screamed from shock. The mild-mannered and friendly "Jerry" was the brilliant but forbidding director and choreographer Jerome Robbins, a winner of multiple Academy and Tony Awards, who because of his demanding nature was known as the terror of Broadway. But it all ended well; after that the four of them often played bridge.

(A personal aside: I saw many of Robbins's ballets in New York, loved them all. But my favorite ballet of all time was his "Illuminations," inspired by the poetry of Rimbaud; he caught the spirit of Rimbaud beautifully, and the final scene haunts me to this day: Profane Love, with blood running down his forearm from a gunshot wound, stares in wonder and regret -- biting regret, I suspect -- as Sacred Love, a female dancer in white, does arabesques back and forth, back and forth, upstage, embodying all those supreme aspirations that we all have and rarely fulfill. Rimbaud, of course, had been shot by his enraged lover Verlaine in Brussels, during their adventurous wanderings together, after Verlaine had deserted his wife and infant daughter. How I wish I could have met Robbins and thanked him for this memorable theatrical experience!)

It wouldn't be easy, being the sensitive

It wouldn't be easy, being the sensitive young son of this man. My own fleeting contact with celebrities include no such luminosities as Gypsy Rose Lee or Jackie Kennedy. My first experience was at one remove from grandeur. When I was teaching French at Columbia College, Arthur MacArthur, the young son of the famous Douglas, turned up in one of my classes. He was a sensitive, intelligent kid whose near flawless French accent implied close work over time with a private tutor. One sensed about him that, through no fault of his own, he had been raised too much in the company of women (his mother, his amah in the Philippines), with little contact with boys his own age. Even at Columbia he stood apart, would never be one of the gang. Later on I learned how, under paternal pressure, he had tried on the uniform of a West Point cadet, but wisely knew it was all wrong for him. Still later he shed the burden of his famous name, which came to him from Douglas’s father Arthur MacArthur, another general who had served in the Philippines. I hope that, with his new persona, he has been able to at last be himself and find the fulfillment he needed.

The Actors' Studio, within whose walls theatrical

The Actors' Studio, within whose walls theatricalwonders and horrors have been perpetrated. My other celebrities are not internationally known figures, but gifted directors in the world of the theater. Long ago, during the folly of my attempts to be a playwright, I was invited to join the Playwrights Unit of the Actors Studio, the citadel of method acting, nested then as now in a former church on West 44th Street. In those once hallowed premises I attended writers’ classes where Harold Clurman presided, and directors’ classes where Lee Strasberg reigned supreme. The Studio was then a bit past its peak, having hatched any number of renowned actors who had gone on to fame and fortune: Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, Paul Newman, James Dean, Shelley Winters, and countless others.

Marilyn Monroe in The Prince and the Showgirl

Marilyn Monroe in The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), five years before her suicide. This photo,

with its touch of naiveté, conveys exactly what

the photo at the Studio demonstrated. On the wall was a photograph of members sitting scattered about the vast room where classes were held; one's eye went immediately to a young blond woman sitting apart from the others: Marilyn Monroe. Her radiant beauty was such that you simply could not not notice her. A veteran member of the Studio told a bunch of us just when the photograph had been taken. If you had any doubt about what is known as star quality, this photograph dispelled it. Some people simply exude a magnetic charm.

Lee Strasberg was a brilliant but savage teacher, quite willing to reduce to tears a young director whose work he relentlessly criticized, continuing with no notice of the tears till she dried them and listened to his critique. Nothing fueled his sadism more than to sense – or imagine – a young director’s presumption that he could reveal the values of some time-honored piece of theater that had already seen scores, if not hundreds, of productions; such presumption he delighted in chewing up. His taste for young women was also blunt and obvious.

Lee Strasberg, teaching. I recall in particular two comments Strasberg made in the course of a class. A very imaginative young director had presented a scene from Macbeth laden with special effects and symbolism. When those present were invited to comment, I said that everything I had seen was fascinating, but the story of Macbeth had gotten lost. When Strasberg critiqued the scene, he said that the Weird Sisters weren't weird enough, they were too human, too approachable. "Imagine this," he said. "A young man goes out on a cold winter day and sees a beautiful woman dancing naked in the snow and the cold. She has to be a witch."

Lee Strasberg, teaching. I recall in particular two comments Strasberg made in the course of a class. A very imaginative young director had presented a scene from Macbeth laden with special effects and symbolism. When those present were invited to comment, I said that everything I had seen was fascinating, but the story of Macbeth had gotten lost. When Strasberg critiqued the scene, he said that the Weird Sisters weren't weird enough, they were too human, too approachable. "Imagine this," he said. "A young man goes out on a cold winter day and sees a beautiful woman dancing naked in the snow and the cold. She has to be a witch."The other comment concerned Marilyn Monroe, who was going to appear in the movie Some Like It Hot. She would be playing with Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in drag, whose real identity in the story she wasn't at first supposed to know. She didn't know how to relate to them and therefore consulted her mentor, Strasberg.

"Marilyn," he said, "you've always told me that you'd like to have women friends, but you never have. Here's your chance. They can be the women friends you've always wanted."

She must have absorbed this advice, for she played with the two actors in drag beautifully. But if Marilyn Monroe lacked women friends, it's easy to see why. Her beauty was such that it would eclipse any other woman. When she committed suicide in 1962 at age thirty-six, Strasberg gave the eulogy at her funeral. Harold Clurman, unlike Strasberg, was not a true teacher. If someone seemed to disagree with him he simply pulled rank, declaring that he knew more about it than they did, rather than gently leading the offender to realize the error of his ways. In some of his comments there was a sense of a deep hurt; for all his professional success, something was lacking. When the subject of transmigration of souls surfaced once, he declared emphatically, “No thanks! Once is enough!” So unlike Strasberg, who seemed impervious to hurt. When the Studio got a grant, they mounted two memorable productions on Broadway. Strasberg did Chekhov’s Three Sisters, which I recall vividly, and Clurman did the French playwright Giraudoux’s Tiger at the Gates (La Guerre de Troye n’aura lieu), a witty and moving account of the beginning of the Trojan War. When the curtain first went up, there was a haunting tableau showing Hector’s wife Andromache and the doomed visionary Cassandra momentarily frozen in place. One knew at once that this was a story steeped in legend and myth. No question, these were brilliant directors.

Courtesy of The Villager Another director whom I had more contact with was Gene Frankel, a former pupil of Strasberg’s, whose school’s classes for writers I attended in an upstairs studio on MacDougal Street here in the West Village in the 1950s. The Gene Frankel of that time was not the bearded patriarch of later years, but a cleanshaven man in his forties with a high forehead, dark hair and heavy dark eyebrows over dark eyes, robust features that showed great character, and an expressive voice capable of many modulations. Attending writing classes there included the privilege of sitting in on Frankel’s directors’ classes, where he held forth from a thronelike central seat, smoking steadily in violation of the city’s fire regulations. An intensely serious man, he seemed rarely to smile. I marveled at his understanding of human nature, of the words and gestures that we use to express ourselves. Frankel saw my first one-act play and gave valuable criticism before letting it be done in his workshop theater; above all, it needed pruning. A young actor I met there told me that he had learned more in one month of Frankel’s classes than he had in a year or two elsewhere.

Courtesy of The Villager Another director whom I had more contact with was Gene Frankel, a former pupil of Strasberg’s, whose school’s classes for writers I attended in an upstairs studio on MacDougal Street here in the West Village in the 1950s. The Gene Frankel of that time was not the bearded patriarch of later years, but a cleanshaven man in his forties with a high forehead, dark hair and heavy dark eyebrows over dark eyes, robust features that showed great character, and an expressive voice capable of many modulations. Attending writing classes there included the privilege of sitting in on Frankel’s directors’ classes, where he held forth from a thronelike central seat, smoking steadily in violation of the city’s fire regulations. An intensely serious man, he seemed rarely to smile. I marveled at his understanding of human nature, of the words and gestures that we use to express ourselves. Frankel saw my first one-act play and gave valuable criticism before letting it be done in his workshop theater; above all, it needed pruning. A young actor I met there told me that he had learned more in one month of Frankel’s classes than he had in a year or two elsewhere. Although he was a brilliant teacher and director, Frankel was always a bit on the fringe of the theater world, preferring the greater freedom of Off Broadway. Among his directorial successes were Jean Genet's The Blacks, which ran for far longer than he had anticipated, and Arthur Kopit's Indians; I saw them both, they were memorable. But at times he could be ruthlessly candid, telling of being invited to go off somewhere in the Midwest to work with a director who was “very inexperienced and very stupid.” And he was quite capable of telling an unduly presumptuous young director in his class, "The theater has no place for you -- get out!"

At times he also exhibited a touch of homophobia. Telling of a attending a performance of a play whose "author" -- probably an adapter at best -- was young, inexperienced, and flustered, he asked, "Who is he? The director's lover? If we must have homosexuals in the theater, let them at least be like Oscar Wilde!" But what did this mean? A preference for polished brilliance over inexperience and fluster? He said this without seeming to be aware of a gay contingent in his classes. Unlike Strasberg at the Studio, who, though himself resolutely heterosexual, clearly knew that his classes included just such a contingent.

But despite these occasional outbursts, Frankel was usually quiet and contained. If one entered his office, one generally found him staring with great concentration at a chessboard; it took a few ahems and other subtle or not so subtle hints to indicate your humble presence and take counsel of his wisdom.

Asked in later years if he would like to retire, Frankel replied, "How can I retire? Directing is in my blood, and teaching is in my bones!" He died in 2005; a theater bearing his name has long existed on Bond Street and strives to keep his name and legacy alive. I wish them well in their endeavors.

Thought for the day: Silence, the undersong of life.

(c) 2012 Clifford Browder

Published on January 06, 2013 05:26

December 30, 2012

40. Mrs. Satan Locks Horns with the Mighty, part 2

What happened after Victoria Woodhull's threat of exposure to the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, minutes before she was to begin her lecture to a hall jammed with spectators lured there in hopes of a candid exposition of free love, was probably a surprise to all. When Victoria and her supporters, her sister Tennie included, marched out onto the platform, Theodore Tilton was at the head of the group. Stepping to the front of the platform, he raised his hands to quiet the crowd, then explained that he had come to hear what his friend had to say on a great question of much importance to her, and since various gentlemen had declined to introduce her because of objections to her character, he would do so himself. He then vouched warmly for her character and said that it was with great pride that he presented Victoria Woodhull, who would speak on the subject of social freedom.

What had prompted this sudden act by Tilton? Perhaps he wanted to deflect her threat to expose Beecher, which would also compromise his wife's reputation. Perhaps he was yielding to a generous quixotic impulse, as he was known to do. And perhaps it was out of gallantry. The tone of his words was that of a lover. He may well have been one of her many inamorati, which complicates even more the complexities of the Beecher-Tilton relationship.

Following the outlines of a speech prepared by one of her male associates, Victoria began with an account of changing attitudes toward the freedom of the individual. But when she got to the present, she registered more passion and emphasis, and excitement began to mount in the audience, then hissing countered by applause.

"Are you a free lover?"someone shouted.

"Yes!" she replied. "I am a free lover!" And as cheers, hoots, and howls redoubled, she persisted with fervor, ignoring her prepared text completely: "I have an inalienable, constitutional, and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as a short a period as I can, to change that love every day if I please!"

Pandemonium ensued. Some hissed and booed; others cheered and tossed their hats in the air. She continued speaking for another ten minutes, decrying the false modesty that silences discussions of sex, and the evils attending such modesty's abuses, while insisting that she would have her fellow beings think well of her, that she was telling them her vision of the future because she loved them well. No one present was likely to forget her impassioned finale.

The speech was fully reported in the Herald, and dire consequences followed. Victoria and her household were soon forced to leave their mansion for a boardinghouse on 23rd Street, and business fell off dramatically at their Broad Street office. Commodore Vanderbilt's family were doubtlessly thanking their lucky stars -- or perhaps the Beneficent Creator -- that he had long since severed ties with this wanton and her sister, whose names would now be inexorably linked to free love. But if Americans didn't share the firebrand's opinions, they were eager to hear about them; lecture invitations poured in from all over the country.

A cartoon by Thomas Nast, 1872. BE SAVED BY FREE LOVE offers Woodhull, in the garb of the Devil,as a respectable housewife toils in the opposite direction, burdened with children and an alcoholic spouse: "I'd rather follow the hardest path of matrimony than follow in your footsteps."

In December 1871 the undaunted sisters marched up Broadway in solidarity with the International Workingmen's Association, in memory of martyred Communards executed by the bourgeois government of France after the brutal repression of the French Commune. And at the annual winter convention of the National Suffrage Association in Washington, Victoria appeared on the platform with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton, who were not yet ready to break with the firebrand whom some were now calling Mrs. Satan. Rumors of scandal plagued her campaign for the presidency on the ticket of the newly formed Equal Rights Party, and lack of funds forced her from the Broad Street office and caused the Weekly to suspend publication. Things didn't look good for Mrs. Satan.

But Victoria wasn't done yet. In September, when a delegate to the National Spiritualists' Association in Boston accused her of obtaining money under false pretenses, she took the stand and, furious, gave the details of the Rev. Beecher's affair with Libby Tilton. How dare he preach the sanctity of marriage while practicing free love clandestinely? Impressed, the spiritualists reelected her president of the association. So the cat was out of the bag at last.

Back in New York, using funds from a still unknown source, she revived Woodhull & Claflin's Weeklywith a bang. The first new issue, dated November 2, 1872 (though published earlier), gave a lengthy account of the Beecher-Tilton scandal. She claimed to speak reluctantly, out of a sense of duty, so as to support her campaign against the outworn institution of marriage. She was nothing if not candid, mentioning Beecher's "demanding physical nature" and "immense physical potency." With the intimacy of Mrs. Tilton and the minister she had no quarrel, only with Beecher's hypocrisy. As for Tilton, his conduct had been no better than Beecher's; she deplored his displays of wounded feelings and pride. (Whatever intimacy they may once have shared by now had obviously soured.)

Word spread quickly; issues flew off the stands. By evening, they were said to be going for forty dollars a copy. The scandal of the century had finally burst into full view of the public.

On November 2, several days after the issue actually appeared, the sisters were arrested while riding in a carriage on Broad Street. Arraigned before a packed courtroom, they learned that they were charged with sending obscene matter through the mail, the matter involved being "an atrocious, abominable and untrue libel on a gentleman whom the whole country reveres." Who had brought the charges? None other than Anthony Comstock (see post #37), using a federal law of 1872, since the famous and infamous Comstock law had yet to be lobbied for and passed. The sisters were in full bloom, according to the press, which described Victoria as "sedate," and Tennie as "bright" and "animated," with sparkling blue eyes, and "splendid teeth" that she took care to display. And who was there to defend them? Another giant of the day whom we have seen already (post #29): William Howe, the bejeweled elephant. The sisters were a magnet for the eminences of the time.

Choosing not to put up bail, the sisters were confined to Ludlow Street Jail, where they vividly denounced the American Bastille to the journalists who flocked to interview them. (In point of fact, their durance was not so vile, since the staff there gave them courteous attention and by their own account never, during their sojourn, uttered a word unmentionable to ears polite.) Meanwhile Counselor Howe protested this attack on free speech, and insisted that the Bible, Lord Byron, and Shakespeare could be similarly suppressed. As the trial was endlessly delayed, the press made a good show of the lovely captives, their grim accuser, their diamond-bedecked defender, and others related to the case. Finally, after four weeks in the Bastille, the sisters consented to put up bail and were released. Their month's incarceration had won them sympathy, and garnered Comstock criticism and more than a touch of mockery.

Poster for a lecture by the sisters following their incarceration.

Poster for a lecture by the sisters following their incarceration.From the collections of the Museum of the City of New York.

The whole affair dragged on, with further legal complications, and ever fuller measures of mockery for Comstock from the ungodly, until a ruling came at last on June 27, 1873, when the presiding judge ruled that the 1872 law did not apply to newspapers. By then the stricter Comstock law had been passed, but for this case it was irrelevant. The sisters were gloriously free on a technicality, and their accuser must once again ponder the mysteries of the Master's will, before consoling himself by arresting a local bookdealer for the third time. Victoria meanwhile referred to the YMCA in the Weekly as the American Inquisition, but added that there was no more similarity between the inquisitor Torquemada and Comstock than between a dead lion and a living skunk.

The ensuing scandal took a heavy toll on all concerned. Plymouth Church was stricken, but at Beecher's urging held a board of inquiry that, in spite of the misgivings of some, exonerated Beecher; Tilton was then expelled from the church. Tilton's wife was badgered by Beecher into retracting her confession, and then badgered by Tilton into retracting the retraction; she finally left Tilton because of the publicity. Then in 1875 Tilton sued Beecher for "criminal intimacy" with his wife; the long trial riveted the nation's attention, but after six days of deliberation it ended in a hung jury. The troubled church held a second board of inquiry that also exonerated their beloved minister, but Libby Tilton confessed again to the affair and was also excommunicated. Unable to find employment in this country because of the scandal, Tilton moved to Paris and spent the rest of his life there. Beecher's popularity continued, but he never again enjoyed the uncritical adulation of before.

Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward BeecherA statue by John Quincy Ward, ca. 1888-89,

at Amherst College, Massachusetts,

the reverend's alma mater.

The heroic pose shows that, for some,

he is best remembered as a stalwart abolitionist.

Alex756

Life for Victoria and her sister was not triumphant either. They were shunned on Wall Street, no longer had the support of the leading suffragists of the time, and had mounting financial problems that made the continued publication of the Weekly difficult. Victoria now divorced her current husband, who had supplied many of the articles for their publication. In 1877, in a move that must have surprised all, the two sisters left this country for England, probably financed by William Vanderbilt, the Commodore's heir, so they wouldn't testify in court when some of the Commodore's offspring challenged his will. In England Victoria continued to give controversial lectures, but ended up marrying a wealthy banker. Tennie did even better, marrying a wealthy widower who became a baronet; so the rebel who had once scorned what squeamish people said of her, and who had graced the lap of the richest man in America, was now known as Lady Cook, Viscountess of Montserrat, and lived at times in her husband's castle in Portugal. Needless to say, a curious ending for two flaming female radicals. Their rise in English society may have inspired Henry James's delicious story "The Siege of London," in which an American woman with a shady past (multiple marriages) manages to hook a most respectable young baronet. Tennie died in 1923, and Victoria in 1927. Though the feminists of their time came to shun them, they have since been reclaimed with enthusiasm by the women's rights movement of today.

Historical footnote: When newly moneyed Americans began hitting Europe after the Civil War, in England the upper classes asked a crucial question: Does one marry Americans? When Lord Randolph Churchill of illustrious lineage married Jenny Jerome, the eldest daughter of Wall Street speculator Leonard Jerome, the answer was a resounding Yes! What was good enough for Lord Randolph had to be good enough for the rest of society. (The result, by the way, was Winston Churchill.) Usually these unions involved new American money bonding with impoverished foreign titles. In the case of the Claflin sisters, however, the money was all on the side of the husbands; the sisters provided spark and charm. After World War I impoverished foreign titles were much less enticing to American heiresses; they looked a bit shopworn (the titles, not the heiresses). Henry James treats this theme beautifully in many novels and short stories. He is my favorite American novelist; I highly recommend his works.

Thought for the day: Existence is ecstasy. (A Buddhist idea that has always intrigued me; it prompts reflection.)

(c) 2012 Clifford Browder

Published on December 30, 2012 05:20

December 23, 2012

39. Mrs. Satan Locks Horns with the Mighty, part 1

Victoria Woodhull

Victoria WoodhullLooking thoughtful, as appropriate for the serious one,

though no photograph of the period does full justice to

the "bewitching brokers" and their ability to

dazzle the all-male press corps of the day.

In January 1870 they popped up out of nowhere to appear on Wall Street, in the heart of the all-male bastion of finance: Victoria Woodhull (her married name, though no husband was visible) and her sister Tennie C. (or sometimes Tennessee) Claflin, who with remarkable knowledge and self-assurance began buying and selling stocks. That the two sisters were young and attractive, and always receptive to the press, meant that word of them at once spread far and wide. At a time when respectable women never wanted to be mentioned in the press, the appearance of these two young female speculators was itself unprecedented, and gossip immediately arose about where they got their knowledge of stocks, not to mention the funds to invest. The Herald, always attuned to the new and sensational, sent a reporter to their suite at the stylish Hoffman House, where, significantly, a portrait of Commodore Vanderbilt adorned the wall of the parlor, and near it, a framed religious motto: "To Thy Cross I Cling." That the richest man in the country was backing these two adventurers seemed obvious from the start. The reporter described the sisters and their suite respectfully, and a Herald editorial concluded, "Vive la frou frou!"

Tennie C. Claflin, the other half of the frou frou,

Tennie C. Claflin, the other half of the frou frou,presenting herself as a broker, her mirthful,

effervescent qualities well hidden.

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius VanderbiltHis handsome features and erect posture persisted even

in his later years, as did his taste for the old-fashioned

stock, in preference to the new-fangled necktie.The two sisters now opened a brokerage office at 44 Broad Street, and the entire financial district flocked there to see this phenomenon for themselves. So packed were the premises that the sisters soon posted a sign: "All gentlemen will state their business and then retire at once." The Herald now hailed them as "the bewitching brokers" and "queens of finance." Further speculation was fueled by the sisters' quiet admission that in the previous year they had realized $750,000 in profits -- a dazzling sum mentioned in all the papers of the time. Also noted were the daily visits to their office of Commodore Vanderbilt himself, between whom and Tennie a cheerful familiarity seemed to exist. Adding spice to the scandal -- if scandal there was -- was the fact that Old Sixty Millions, a widower, had recently married a young woman half his age; her husband's gallivanting on Broad Street was surely vexing to the new Mrs.Vanderbilt, who with great forbearance was trying to

tolerate -- for now -- her spouse's playful quirks and eccentricities and, ever so tactfully, nudge him toward her Methodist faith.

More and more rumors circulated: Victoria Woodhull was a divorced woman -- shocking! Furthermore, she claimed to have powers of clairvoyance and healing, and had come to New York at the bidding of her spirit guide, Demosthenes. Worse still, the sisters and their friends were said to believe in -- still more shocking! -- free love. Both sisters had evidently been married before at least once, and maybe more than once; they seemed to shed husbands with remarkable ease. Definitely not bruited in the press were the Vanderbilt clan's concern about the Commodore's prior relations with the duo. William Vanderbilt, the son and heir, had it from his father's servants that Victoria had tried her powers of magnetic healing on him, while Tennie's gauzy charms had often graced the old man's lap. She called him "Old Boy," and he called her "Little Sparrow"; there had even been talk of marriage. So if the Commodore's two sons and nine daughters -- an ennead that he claimed he could barely keep straight -- had been startled by his sudden eloping to Canada with a young Southern gentlewoman, at least he was safely and respectably married.

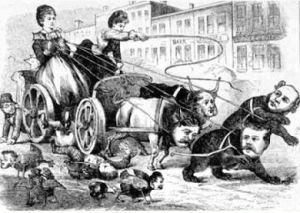

Victoria and Tennie driving the bulls and bears of Wall Street.

Victoria and Tennie driving the bulls and bears of Wall Street.An Evening Telegram cartoon of February 18, 1870.

The "bewitching brokers" shrugged off any rumors about their past. Victoria was always the leader, and Tennie the willing follower, but it was Tennie, mirthful and outspoken, who expressed herself with vehemence: "I despise what squeamy, crying girls or powdered, counter-jumping dandies say of me!" Always the earnest one, Victoria told a reporter, "All the talk about women's rights is moonshine. Women have every right. All they need do is exercise them. That's what we're doing." In post #22 I've already told how they coped with Delmonico's rule about admitting no women customers unless accompanied by a male escort.

If any doubts remained of the sisters' radical opinions, they vanished in May 1870 when a new publication burst upon the scene: Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, whose motto was "Progress! Free Thought! Untrammeled Lives!" In it readers could find articles advocating vocational training for girls, women's suffrage, and regulation of houses of prostitution, and articles on free love, birth control, and abortion, and in time, the first publication in the country of The Communist Manifesto. Behind these views were the ideas of several of the sisters' radical male friends. Every word printed in the Weekly was a challenge to Victorian notions of womanhood, which firmly planted Woman on a pedestal -- in the home, where she should stay. Forays for good works were of course allowed, but otherwise she should be preoccupied with supervising servants, looking after the nursery, and maintaining that revered inner sanctum of the Victorian home, the parlor (about which more in a future post).

The sisters were now getting national attention. In December 1870 Victoria presented a memorial to Congress advocating women's suffrage, The following month she addressed the House Judiciary Committee in a session attended by two prominent leaders of the women's rights movement, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton, whom this development had taken by surprise, and who wanted to get a look at this new advocate and seeming ally. Indeed, by all accounts Victoria Woodhull was a passionate and magnetic speaker. Impressed, Anthony and Stanton invited the sisters to attend their meetings, which let opponents of feminism insist that giving the vote to women would encourage free love and destroy the family.

The sisters were now getting national attention. In December 1870 Victoria presented a memorial to Congress advocating women's suffrage, The following month she addressed the House Judiciary Committee in a session attended by two prominent leaders of the women's rights movement, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton, whom this development had taken by surprise, and who wanted to get a look at this new advocate and seeming ally. Indeed, by all accounts Victoria Woodhull was a passionate and magnetic speaker. Impressed, Anthony and Stanton invited the sisters to attend their meetings, which let opponents of feminism insist that giving the vote to women would encourage free love and destroy the family.

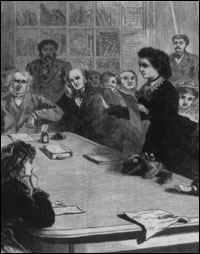

Victoria addressing the House committee.

Victoria addressing the House committee.Her sister may be visible in the lower left.

Publicity had obviously come at a cost. The Bewitching Brokers were now being labeled "humbugs," "public nuisances," and worse. Forced to leave their hotel, they had trouble finding living quarters and for a while slept on the floor of their Broad Street office, before moving into more suitable quarters. But they were in no way discouraged. The Weekly's issue of April 22, 1871, announced in bold lettering the candidacy of Victoria C. Woodhull for the presidency in 1872 on the ticket of the Cosmo-Political Party, an amalgam of radical reform groups. She was the first woman to aspire to the office, though her chances of being elected, or even being allowed to vote, were less than minimal. Yet in September 1871 she had the satisfaction of indeed being elected president -- of the National Association of Spiritualists -- at their annual convention in Troy, New York. (Besides growing apples, upstate New York in those days played host to many a new and radical idea.) But when the sisters tried to vote in the national election in November, they were of course rebuffed.

Collection of the New York Historical Society

Collection of the New York Historical SocietyBy now Victoria's home sheltered a curious assemblage of friends and refugees, stray family members, and assorted husbands (one ex- had turned up in deplorable condition and been granted asylum). All of which fueled the rumors about her most unvictorian life style. To tell the world exactly what her principles were -- as if they weren't apparent already -- soon after the election Victoria rented Steinway Hall for the evening of November 20, 1871, and announced in posters that she intended to silence the critics who had persistently misrepresented and vilified her. The influential editor Horace Greeley and conservative suffragists who were voicing doubts about her were invited to seats on the platform. "Freedom! Freedom! Freedom!" proclaimed banners outside the hall.

In a further act of daring, Victoria invited Henry Ward Beecher, the most renowned preacher of the day, to see her just before the lecture, and in so doing joined her destiny to another giant of the time. Beecher's sermons at the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights were so famous and so inspired that they drew multitudes of Manhattanites every Sunday to that distant borough, still a separate city and not yet connected by a bridge to the metropolis. His sermons were more than words, they were performances. An ardent abolitionist when it was most unfashionable to be one, before the war he had held mock auctions to raise money to free real slaves, and, having obtained the chains that had held John Brown before his execution, trampled those fetters dramatically in the pulpit. He also advocated women's suffrage and Darwinian evolution, and denounced bigotry in all its forms. Lincoln, Walt Whitman, and Mark Twain had all made the pilgrimage to Plymouth Church to witness this phenomenon in action. If Lincoln had freed the slaves, Beecher was said to have freed men's minds. So what did Victoria Woodhull want from the man? Justice, she said in her note, adding that what she would then say or do depended on the result of the interview. Which had the sound of a threat.

Victoria had learned from the feminist Elizabeth Stanton that all was not well in the realm of Beecher. Stanton had heard from Theodore Tilton, a reformist newspaper editor and Beecher's close associate, that Tilton's wife Libby had confessed to having an affair with the renowned clergyman, who was himself married and the father of ten grown children. Indeed, Beecher's muscular frame and long leonine locks, combined with his inspired oratory, made him vastly appealing to women. The affair, though now over, was known to a small circle of Plymouth worshippers, who kept it a snug, tight secret so as to avoid scandal. But word was spreading slowly, and Victoria was not inclined to discretion. She was smarting from criticism by Beecher's sister Catherine, who had urged decent citizens to avoid her recent lecture in Catherine's hometown, Hartford.

Aware of this and feeling vulnerable, the famous preacher came to Victoria when summoned. What she asked of him was simply to introduce her to the waiting audience, which need not imply acceptance of her opinions. While Beecher had endorsed women's suffrage, he most definitely did not approve of free love. Horrified, yet fearful of her reaction if he refused, he fell to his knees and begged her in tears, "Let me off! Let me off!" When she remained adamant, he consulted Tilton himself, who advised him to make the introduction and asked Victoria to join them. Beecher again pleaded for mercy and even threatened suicide, but he could not agree. "Mr. Beecher," said Victoria, "if I am compelled to go onto that platform alone, I shall begin by telling the audience why I am alone and why you are not with me." With this, she left. Beecher's famous emotionalism had been no match for her icy resolve. There is something disturbing, even repellent, in his crumbling before her, but her satisfaction in humiliating the nation's most celebrated clergyman hardly enhances her image. Victoria Woodhull, one has to conclude, was ruthlessly selfish and determined, regardless of the consequences to others. Not just one man's reputation was at stake, but a whole empire of faith.

What happened next was both startling and dramatic. The ongoing story of the sisters, and an account of this, perhaps the most sensational lecture of the century, will be told next week in part 2.

Thought for the day: Desire is holy.

(c) 2012 Clifford Browder

Published on December 23, 2012 04:38

December 16, 2012

38. A Walk Through Greenwich Village

To find respite from the horrors of nineteenth-century New York, I invite you to come with me on a casual walk through Greenwich Village. The West Village, of course, since the East Village is a whole different story. The West Village is well trekked, having loads of historic sites; whenever I go out, I see visitors with their nose in a guidebook, figuring where to go next.

joe goldberg Let's begin on Bleecker Street just downstairs, with the celebrated Magnolia Bakery. Yes, tourists still flock there, sometimes whole busloads, and take photos of one another in front of the bakery. I have yet to buy one of their famous cupcakes, good as they are said to be. A vegan, I'm not tempted to join the throngs gobbling gooey goodies. But I bear them no ill will (the gobblers, not the cupcakes), even when the line winds around the corner onto West 11th Street past our entrance, or the gobblers squat on our doorstep to devour their spoils, even though a small park beckons to them just across the street. Notice the mailbox, too; if anyone ever gets a letter from me, that's where it was mailed.

joe goldberg Let's begin on Bleecker Street just downstairs, with the celebrated Magnolia Bakery. Yes, tourists still flock there, sometimes whole busloads, and take photos of one another in front of the bakery. I have yet to buy one of their famous cupcakes, good as they are said to be. A vegan, I'm not tempted to join the throngs gobbling gooey goodies. But I bear them no ill will (the gobblers, not the cupcakes), even when the line winds around the corner onto West 11th Street past our entrance, or the gobblers squat on our doorstep to devour their spoils, even though a small park beckons to them just across the street. Notice the mailbox, too; if anyone ever gets a letter from me, that's where it was mailed.

For these tasty globs, some would sell their soul.

For these tasty globs, some would sell their soul.

Andy C

Walking east on West 11th Street, just before we come to Fifth Avenue we see, at 18 West 11th, a handsome townhouse whose jutting bay window seems out of place in this neighborhood of Greek Revival row houses. And no wonder: it's a replacement of a nineteenth-century townhouse demolished in 1970 when a bomb factory of the radical Weather Underground exploded, destroying the entire residence and shattering the genteel calm of the West Village. It took nine days to sift through the rubble to find body parts and determine how many had died there: three, though two others, one the daughter of the house, had been upstairs at the time of the explosion and managed to escape. My thought at the time: little children shouldn't play with bombs. A simplification, perhaps, but I thought the explosion was justified, in a sense, though it was rough on the neighbors, not to mention the absent parents, who had no idea what their little girl was up to in the basement. And where were the bombs to be used? At a dance for noncommissioned officers that evening at Fort Dix, New Jersey, to bring the horrors of the Vietnam War home to the dancers and the public, though maybe also to demolish the main library (where I used to study by the hour) of Columbia University. What they had against the library I can't imagine.

Aude Speaking of libraries, let's have a look at my local public library, the Jefferson Market Library on

Aude Speaking of libraries, let's have a look at my local public library, the Jefferson Market Library on

Sixth Avenue at West 10th Street: a marvelous renovation with Gothic windows and a lofty clock tower with a firewatchers' balcony, and inside, a handsome spiral staircase flanked by stained glass windows, and a spacious reference room with computers and yes, even books, in the basement. (I don't use the reference room much these days, since so much information is available online.) It too has a history. Built in the 1870s, it was originally a courthouse, and there, in 1879, the notorious abortionist Madame Restell was arraigned, following her arrest by Anthony Comstock. Long ago, there was a market next door, but in the early 1930s the Women's House of Detention was constructed next to the courthouse, a local Bastille none too popular with neighbors, since the inmates and their friends down below on the sidewalk would converse in shrill tones with a generous dose of expletives: another affront to West Village gentility. (These exchanges graced my ears many a time in the evening.) Also, there were stories of racial discrimination and abuse. Finally, in 1971, the prison was demolished (only WBAI, stalwart a foe of gentrification, lamented its passing), and the Jefferson Market Garden, a small but delightful park, replaced it. Which was fine by me: the more greenery in this city, the better!

Montrealais Of course no tour of the Village would be complete without a look at the Stonewall Inn, where it all began back in 1969. Yes, it's still there, having presumably had a series of owners since then, and I often walk past it. A simple two-story structure, the ground floor with a brick façade. Believe it or not, I've never been in there. But I do wonder who lives upstairs and how they like having a shrine beneath them, not to mention the brouhaha of the annual Gay Pride Parade passing below.

Montrealais Of course no tour of the Village would be complete without a look at the Stonewall Inn, where it all began back in 1969. Yes, it's still there, having presumably had a series of owners since then, and I often walk past it. A simple two-story structure, the ground floor with a brick façade. Believe it or not, I've never been in there. But I do wonder who lives upstairs and how they like having a shrine beneath them, not to mention the brouhaha of the annual Gay Pride Parade passing below.

Just across the street is Sheridan Square, once an open space available for community meetings and political rallies, and used as a drilling ground and playground; only since 1982 has it been a garden. Dominating it is a statue of Phil Sheridan, the Northern cavalry hero of the Civil War, first erected in 1936. Now, quite within his gaze, are four life-size statues, a man with a man, and a woman with a woman, each couple showing signs of affection. What the stern-faced general thinks of all this is hard to say.

Deirdre

Deirdre

Jean-Christophe Benoist

Jean-Christophe Benoist

When I first came to New York in the 1950s, I heard that there were renters who would give anything to have an address on Gay Street. Gay Street is a street just one block long between Christopher and Waverley Place, one of those charming little side streets so common in the Village. I always thought it was named for John Gay, one of the Founding Fathers, but now I learn that it takes its name from an early landowner. Why this address should be so coveted, I can't imagine.

Beyond My Ken Film crews are often busy on the Village streets, sometimes doing films with a historical background. And why not, when the row houses on many Village streets seem unchanged from an earlier period. Consider this photo of Washington Square North, between Fifth Avenue and University Place: a solid block of Greek Revival houses built in 1832-33. Take away the car, avoid the air conditioners if possible, and the looming buildings in the distance, and you could be back in nineteenth-century New York. Behind the preserved façades, some of these buildings have been gutted to make room for apartments, but from the outside you would never know it. And what was "Greek" about them? Chiefly the columns flanking the entrances. In congested New York there was hardly room for the spacious porticos fronting Monticello and many a prebellum Southern mansion.

Beyond My Ken Film crews are often busy on the Village streets, sometimes doing films with a historical background. And why not, when the row houses on many Village streets seem unchanged from an earlier period. Consider this photo of Washington Square North, between Fifth Avenue and University Place: a solid block of Greek Revival houses built in 1832-33. Take away the car, avoid the air conditioners if possible, and the looming buildings in the distance, and you could be back in nineteenth-century New York. Behind the preserved façades, some of these buildings have been gutted to make room for apartments, but from the outside you would never know it. And what was "Greek" about them? Chiefly the columns flanking the entrances. In congested New York there was hardly room for the spacious porticos fronting Monticello and many a prebellum Southern mansion.

Preceding the Greek Revival style was the Federal style row house, with roofs sloping toward the street and adorned with dormer windows, as seen in these King Street residences from the 1820s. They are fewer in the Village, where Greek Revival tends to dominate, but you will see them here and there. And brownstones? They came in in the 1850s and 1860s, and are found mostly farther uptown.

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken

When strolling through the Village, one should always be on the lookout for little side courts off the main streets that one could easily walk past without even noticing them Here, for example, seen through the grilled gate of the entrance, is Milligan Place, a private court off Sixth Avenue between West 10th and West 11th Streets. Four three-story brick houses built in 1855 open onto it. I've often walked past it, sometimes forget to have a look.

Earlier I mentioned the Greek Revival row houses facing Washington Square Park. That park too has quite a history. Once farmland, it was bought by the city in 1797 for a potter's field. When yellow fever epidemics plagued the city in the early nineteenth century, victims were buried here, well removed from the settled part of Manhattan. When the cemetery was closed in 1825, some twenty thousand bodies had been buried there; though few realize it, most are still there today. In 1826 the area became a parade ground for volunteer militia, and then, in the 1830s, a desirable residential area with handsome Greek Revival houses. Where gentility resides, can parkland fail to follow? In 1849/1850 the first park was laid out, and the first fountain installed in 1852. Even after gentility moved farther uptown, the park remained. Fifth Avenue, lined then with handsome private residences and hailed as the axis of elegance, ran northward from there, spiked at intervals by the spires of fashionable churches.

Petri Krohn In 1892, to celebrate the nation's first president, the Washington Square Arch, designed by the famous architect Stanford White, was erected, modeled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris; in the process, many graves were disturbed. One might think that such an imposing marble embellishment would have guaranteed the park's preservation, but no, in 1935 Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, without consulting the community, announced a plan to redesign the park. Local residents mobilized to resist the renovation and finally managed to block it. But Moses, a master builder whose grandiose schemes often disrupted or destroyed existing neighborhoods, wasn't done with the park. In 1952 he announced another plan to have two streets flank the arch and run on south through the park. This renewed assault again aroused the opposition of local residents, including Eleanor Roosevelt, who mounted a campaign not only to save the park but also to ban all vehicles from it. A David vs. Goliath fight followed, with many legal twists and turns, but David won: in 1963 the park was finally saved and vehicles were banned from it forever. (It doesn't hurt to have a former First Lady on your side, though the long struggle was led by other activists.)

Petri Krohn In 1892, to celebrate the nation's first president, the Washington Square Arch, designed by the famous architect Stanford White, was erected, modeled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris; in the process, many graves were disturbed. One might think that such an imposing marble embellishment would have guaranteed the park's preservation, but no, in 1935 Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, without consulting the community, announced a plan to redesign the park. Local residents mobilized to resist the renovation and finally managed to block it. But Moses, a master builder whose grandiose schemes often disrupted or destroyed existing neighborhoods, wasn't done with the park. In 1952 he announced another plan to have two streets flank the arch and run on south through the park. This renewed assault again aroused the opposition of local residents, including Eleanor Roosevelt, who mounted a campaign not only to save the park but also to ban all vehicles from it. A David vs. Goliath fight followed, with many legal twists and turns, but David won: in 1963 the park was finally saved and vehicles were banned from it forever. (It doesn't hurt to have a former First Lady on your side, though the long struggle was led by other activists.)

More struggles have followed, often pitting students, folksingers, drug dealers, and peaceful residents against New York's Finest, whose efforts to preserve the public peace sometimes disrupt it. Yes, drug dealers have at times been active in the park. But in a more innocent earlier era I recall one balmy Saturday evening when a police squad car drove through the sacred spaces of the park, forcing people off the paved path onto the lawn, following which the police yelled at the trespassers, "Get off the grass! Get off the grass!" Nothing had provoked this intervention; all had been peaceful. A wonderful example of how the guardians of order keep the unruly populace in order.

In 2007 the city began redesigning the park, including a realignment of the fountain with the arch. Just why such a realignment was necessary, I couldn't imagine; the lack of it didn't seem to bother anyone. More legal battles followed, but the realignment did take place, to the satisfaction of contractors and geometry freaks, if no one else. In New York City changes never come easy, nor are they always needed. So there you have it: from farmland to potter's field to parade ground to desirable residential area to treasured park defended vigorously by the local residents. Today the magnificent arch rises nobly above the graves of forgotten thousands, and the fountain bubbles joyously.

Finally, to end on a wild, weird note, let's have a glance at the Village Halloween Parade. Initiated in 1974, it used to come down Bleecker Street right under our windows; Bob and I often watched from our fire escape, but to get the full blast of it, you need to watch at ground level. Alas, in time it became too big for narrow Village streets, so in 1985 it was moved over to Sixth Avenue. We haven't watched it since then, because it is no longer "our" parade, but it surely reaches more people now. From the earlier parades I have vivid memories of costumes and masks galore, and more specifically, stilt walkers perilously poised on their stilts, a file of mustached nuns, and a samba band whose blaring rhythms made your blood and brain pulse.

Joe Shlabotnik

Joe Shlabotnik

Wendy R. Williams

Wendy R. Williams

Thought for the day: Energy is eternal delight. (Not my creation, though I don't recall where I encountered it. Still, I've often pondered it.)

(c) 2012 Clifford Browder

joe goldberg Let's begin on Bleecker Street just downstairs, with the celebrated Magnolia Bakery. Yes, tourists still flock there, sometimes whole busloads, and take photos of one another in front of the bakery. I have yet to buy one of their famous cupcakes, good as they are said to be. A vegan, I'm not tempted to join the throngs gobbling gooey goodies. But I bear them no ill will (the gobblers, not the cupcakes), even when the line winds around the corner onto West 11th Street past our entrance, or the gobblers squat on our doorstep to devour their spoils, even though a small park beckons to them just across the street. Notice the mailbox, too; if anyone ever gets a letter from me, that's where it was mailed.

joe goldberg Let's begin on Bleecker Street just downstairs, with the celebrated Magnolia Bakery. Yes, tourists still flock there, sometimes whole busloads, and take photos of one another in front of the bakery. I have yet to buy one of their famous cupcakes, good as they are said to be. A vegan, I'm not tempted to join the throngs gobbling gooey goodies. But I bear them no ill will (the gobblers, not the cupcakes), even when the line winds around the corner onto West 11th Street past our entrance, or the gobblers squat on our doorstep to devour their spoils, even though a small park beckons to them just across the street. Notice the mailbox, too; if anyone ever gets a letter from me, that's where it was mailed. For these tasty globs, some would sell their soul.

For these tasty globs, some would sell their soul.Andy C

Walking east on West 11th Street, just before we come to Fifth Avenue we see, at 18 West 11th, a handsome townhouse whose jutting bay window seems out of place in this neighborhood of Greek Revival row houses. And no wonder: it's a replacement of a nineteenth-century townhouse demolished in 1970 when a bomb factory of the radical Weather Underground exploded, destroying the entire residence and shattering the genteel calm of the West Village. It took nine days to sift through the rubble to find body parts and determine how many had died there: three, though two others, one the daughter of the house, had been upstairs at the time of the explosion and managed to escape. My thought at the time: little children shouldn't play with bombs. A simplification, perhaps, but I thought the explosion was justified, in a sense, though it was rough on the neighbors, not to mention the absent parents, who had no idea what their little girl was up to in the basement. And where were the bombs to be used? At a dance for noncommissioned officers that evening at Fort Dix, New Jersey, to bring the horrors of the Vietnam War home to the dancers and the public, though maybe also to demolish the main library (where I used to study by the hour) of Columbia University. What they had against the library I can't imagine.

Aude Speaking of libraries, let's have a look at my local public library, the Jefferson Market Library on

Aude Speaking of libraries, let's have a look at my local public library, the Jefferson Market Library onSixth Avenue at West 10th Street: a marvelous renovation with Gothic windows and a lofty clock tower with a firewatchers' balcony, and inside, a handsome spiral staircase flanked by stained glass windows, and a spacious reference room with computers and yes, even books, in the basement. (I don't use the reference room much these days, since so much information is available online.) It too has a history. Built in the 1870s, it was originally a courthouse, and there, in 1879, the notorious abortionist Madame Restell was arraigned, following her arrest by Anthony Comstock. Long ago, there was a market next door, but in the early 1930s the Women's House of Detention was constructed next to the courthouse, a local Bastille none too popular with neighbors, since the inmates and their friends down below on the sidewalk would converse in shrill tones with a generous dose of expletives: another affront to West Village gentility. (These exchanges graced my ears many a time in the evening.) Also, there were stories of racial discrimination and abuse. Finally, in 1971, the prison was demolished (only WBAI, stalwart a foe of gentrification, lamented its passing), and the Jefferson Market Garden, a small but delightful park, replaced it. Which was fine by me: the more greenery in this city, the better!

Montrealais Of course no tour of the Village would be complete without a look at the Stonewall Inn, where it all began back in 1969. Yes, it's still there, having presumably had a series of owners since then, and I often walk past it. A simple two-story structure, the ground floor with a brick façade. Believe it or not, I've never been in there. But I do wonder who lives upstairs and how they like having a shrine beneath them, not to mention the brouhaha of the annual Gay Pride Parade passing below.

Montrealais Of course no tour of the Village would be complete without a look at the Stonewall Inn, where it all began back in 1969. Yes, it's still there, having presumably had a series of owners since then, and I often walk past it. A simple two-story structure, the ground floor with a brick façade. Believe it or not, I've never been in there. But I do wonder who lives upstairs and how they like having a shrine beneath them, not to mention the brouhaha of the annual Gay Pride Parade passing below.Just across the street is Sheridan Square, once an open space available for community meetings and political rallies, and used as a drilling ground and playground; only since 1982 has it been a garden. Dominating it is a statue of Phil Sheridan, the Northern cavalry hero of the Civil War, first erected in 1936. Now, quite within his gaze, are four life-size statues, a man with a man, and a woman with a woman, each couple showing signs of affection. What the stern-faced general thinks of all this is hard to say.

Deirdre

Deirdre Jean-Christophe Benoist

Jean-Christophe Benoist When I first came to New York in the 1950s, I heard that there were renters who would give anything to have an address on Gay Street. Gay Street is a street just one block long between Christopher and Waverley Place, one of those charming little side streets so common in the Village. I always thought it was named for John Gay, one of the Founding Fathers, but now I learn that it takes its name from an early landowner. Why this address should be so coveted, I can't imagine.

Beyond My Ken Film crews are often busy on the Village streets, sometimes doing films with a historical background. And why not, when the row houses on many Village streets seem unchanged from an earlier period. Consider this photo of Washington Square North, between Fifth Avenue and University Place: a solid block of Greek Revival houses built in 1832-33. Take away the car, avoid the air conditioners if possible, and the looming buildings in the distance, and you could be back in nineteenth-century New York. Behind the preserved façades, some of these buildings have been gutted to make room for apartments, but from the outside you would never know it. And what was "Greek" about them? Chiefly the columns flanking the entrances. In congested New York there was hardly room for the spacious porticos fronting Monticello and many a prebellum Southern mansion.

Beyond My Ken Film crews are often busy on the Village streets, sometimes doing films with a historical background. And why not, when the row houses on many Village streets seem unchanged from an earlier period. Consider this photo of Washington Square North, between Fifth Avenue and University Place: a solid block of Greek Revival houses built in 1832-33. Take away the car, avoid the air conditioners if possible, and the looming buildings in the distance, and you could be back in nineteenth-century New York. Behind the preserved façades, some of these buildings have been gutted to make room for apartments, but from the outside you would never know it. And what was "Greek" about them? Chiefly the columns flanking the entrances. In congested New York there was hardly room for the spacious porticos fronting Monticello and many a prebellum Southern mansion.Preceding the Greek Revival style was the Federal style row house, with roofs sloping toward the street and adorned with dormer windows, as seen in these King Street residences from the 1820s. They are fewer in the Village, where Greek Revival tends to dominate, but you will see them here and there. And brownstones? They came in in the 1850s and 1860s, and are found mostly farther uptown.

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken

Beyond My Ken When strolling through the Village, one should always be on the lookout for little side courts off the main streets that one could easily walk past without even noticing them Here, for example, seen through the grilled gate of the entrance, is Milligan Place, a private court off Sixth Avenue between West 10th and West 11th Streets. Four three-story brick houses built in 1855 open onto it. I've often walked past it, sometimes forget to have a look.

Earlier I mentioned the Greek Revival row houses facing Washington Square Park. That park too has quite a history. Once farmland, it was bought by the city in 1797 for a potter's field. When yellow fever epidemics plagued the city in the early nineteenth century, victims were buried here, well removed from the settled part of Manhattan. When the cemetery was closed in 1825, some twenty thousand bodies had been buried there; though few realize it, most are still there today. In 1826 the area became a parade ground for volunteer militia, and then, in the 1830s, a desirable residential area with handsome Greek Revival houses. Where gentility resides, can parkland fail to follow? In 1849/1850 the first park was laid out, and the first fountain installed in 1852. Even after gentility moved farther uptown, the park remained. Fifth Avenue, lined then with handsome private residences and hailed as the axis of elegance, ran northward from there, spiked at intervals by the spires of fashionable churches.

Petri Krohn In 1892, to celebrate the nation's first president, the Washington Square Arch, designed by the famous architect Stanford White, was erected, modeled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris; in the process, many graves were disturbed. One might think that such an imposing marble embellishment would have guaranteed the park's preservation, but no, in 1935 Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, without consulting the community, announced a plan to redesign the park. Local residents mobilized to resist the renovation and finally managed to block it. But Moses, a master builder whose grandiose schemes often disrupted or destroyed existing neighborhoods, wasn't done with the park. In 1952 he announced another plan to have two streets flank the arch and run on south through the park. This renewed assault again aroused the opposition of local residents, including Eleanor Roosevelt, who mounted a campaign not only to save the park but also to ban all vehicles from it. A David vs. Goliath fight followed, with many legal twists and turns, but David won: in 1963 the park was finally saved and vehicles were banned from it forever. (It doesn't hurt to have a former First Lady on your side, though the long struggle was led by other activists.)

Petri Krohn In 1892, to celebrate the nation's first president, the Washington Square Arch, designed by the famous architect Stanford White, was erected, modeled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris; in the process, many graves were disturbed. One might think that such an imposing marble embellishment would have guaranteed the park's preservation, but no, in 1935 Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, without consulting the community, announced a plan to redesign the park. Local residents mobilized to resist the renovation and finally managed to block it. But Moses, a master builder whose grandiose schemes often disrupted or destroyed existing neighborhoods, wasn't done with the park. In 1952 he announced another plan to have two streets flank the arch and run on south through the park. This renewed assault again aroused the opposition of local residents, including Eleanor Roosevelt, who mounted a campaign not only to save the park but also to ban all vehicles from it. A David vs. Goliath fight followed, with many legal twists and turns, but David won: in 1963 the park was finally saved and vehicles were banned from it forever. (It doesn't hurt to have a former First Lady on your side, though the long struggle was led by other activists.) More struggles have followed, often pitting students, folksingers, drug dealers, and peaceful residents against New York's Finest, whose efforts to preserve the public peace sometimes disrupt it. Yes, drug dealers have at times been active in the park. But in a more innocent earlier era I recall one balmy Saturday evening when a police squad car drove through the sacred spaces of the park, forcing people off the paved path onto the lawn, following which the police yelled at the trespassers, "Get off the grass! Get off the grass!" Nothing had provoked this intervention; all had been peaceful. A wonderful example of how the guardians of order keep the unruly populace in order.

In 2007 the city began redesigning the park, including a realignment of the fountain with the arch. Just why such a realignment was necessary, I couldn't imagine; the lack of it didn't seem to bother anyone. More legal battles followed, but the realignment did take place, to the satisfaction of contractors and geometry freaks, if no one else. In New York City changes never come easy, nor are they always needed. So there you have it: from farmland to potter's field to parade ground to desirable residential area to treasured park defended vigorously by the local residents. Today the magnificent arch rises nobly above the graves of forgotten thousands, and the fountain bubbles joyously.

Finally, to end on a wild, weird note, let's have a glance at the Village Halloween Parade. Initiated in 1974, it used to come down Bleecker Street right under our windows; Bob and I often watched from our fire escape, but to get the full blast of it, you need to watch at ground level. Alas, in time it became too big for narrow Village streets, so in 1985 it was moved over to Sixth Avenue. We haven't watched it since then, because it is no longer "our" parade, but it surely reaches more people now. From the earlier parades I have vivid memories of costumes and masks galore, and more specifically, stilt walkers perilously poised on their stilts, a file of mustached nuns, and a samba band whose blaring rhythms made your blood and brain pulse.

Joe Shlabotnik

Joe Shlabotnik Wendy R. Williams

Wendy R. Williams

Thought for the day: Energy is eternal delight. (Not my creation, though I don't recall where I encountered it. Still, I've often pondered it.)

(c) 2012 Clifford Browder

Published on December 16, 2012 04:44

December 9, 2012

37. God's Agent and the Hydra-Headed Monster

New York City, mid-1870s:

BAM BAM BAM. His hard fist smote the door.

“Open up in the name of the Law!” he yelled.

From within, whispers, scurryings. CRACK. Smashed by his black boot, the door splintered, collapsed. Lunging through with warrants in one hand, a revolver in the other, his badge agleam on his breast, the Special Agent of the Post Office and the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice barked out: “Arrest those men! Impound all smut as evidence!”

From behind him, bluecoats rushed to obey. Within minutes the prisoners had been led out manacled, and a printing press and tons of print carted off: another smut den closed.

For a year the Special Agent, in drab black over stiff white over perennial red flannel underwear (his only dash of color), had crisscrossed the nation by rail, his pockets laden with handcuffs for miscreants, and cheap rubber toys for little children, whose innocence he treasured. Caned by an abortionist, pommeled by an ex-pugilist, and stabbed in the face by a smut dealer at his third arrest, he had clapped them all in jail.

In rare quiet moments, nursing bruises or a severed artery, he sat at his desk writing speeches for Purity Leagues, or letters to abortionists tempting them, in a small, neat script with flourishes and signed with a ladylike name, toward offenses by mail that if committed brought immediate arrest.

In January 1874 he read his first confidential report to the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, a distinguished assembly of merchants, doctors, lawyers, and judges, itemizing his seizures in the past year:

130,000 lbs. of bound books.194,000 bad pictures and photographs. 60,300 articles made of rubber for immoral purposes,

and used by both sexes. 5,500 indecent playing cards. 3,150 boxes of pills and powders used by abortionists.130,275 advertising circulars, catalogues, handbills,

and songs. 4,750 newspapers containing improper advertisements,

or other matter. 20,000 letters from various parts of the United States