Clifford Browder's Blog, page 54

March 13, 2013

51. New York and Water: The Hudson

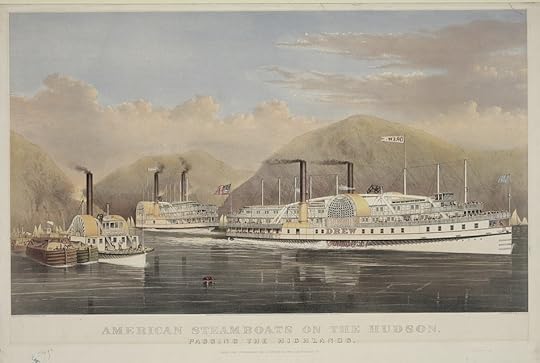

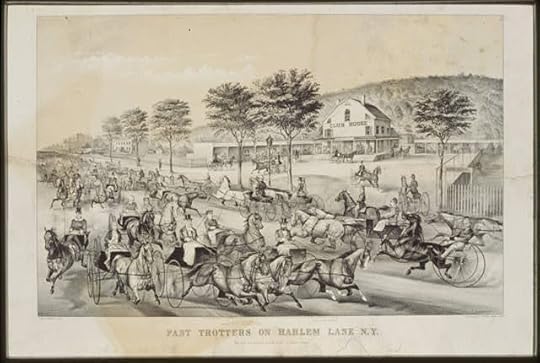

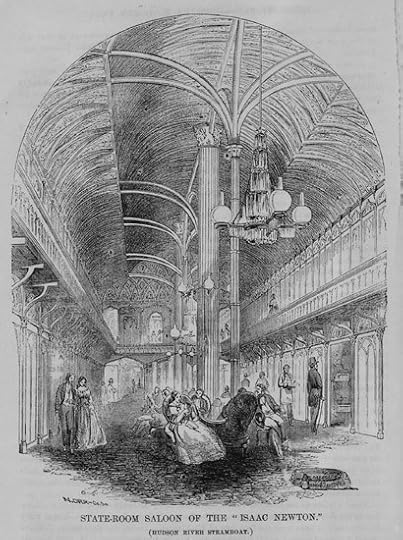

Another post on New York City's relation to water. In the mid-nineteenth century, before the proliferation of railroads, the city's life was intimately linked to the Hudson River. This post, adapted from my fiction, follows the river through the cycle of seasons.

Ice gripped the Hudson. In the far north among cloud-splitting mountains towering over cedar and spruce, it gripped Lake Tear of the Clouds, Feldspar Brook, and the Opalescent River. In snowy forests where bears slept and wolves prowled, it gripped the springs and sources, the streams and tributaries. Ice gripped the narrow channel at Glens Falls, and at Troy, the head of navigation, glinting green and gray-silver in the sun, and gripped the widening channel at Albany. Ice blocked the wharves at Rondout and Poughkeepsie, and sheathed the twisting channel through the Highlands, where Storm King, Breakneck Mountain, and Dunderberg humped their granite skyward. It locked the broad reaches of Haverstraw Bay and the Tappan Zee, and lay rigid under the sheer basalt cliffs of the Palisades, where through pronged branches of oak and beech, the wind whipped and whistled. Almost to the city of New York, ice gripped the river. Skaters skated on it, fishermen chopped holes in it, and as powdery white gusts whisked up from its surfaces, people trudged from one bank to the other.

Along the Erie Canal the canal men, their barges docked for the season, boozed and whored, and when their money ran out, drummed their fingers and waited. In the river towns the merchants, eyeing mountains of goods stacked on piers or in warehouses, muttered and dreamed of a railroad. Boatmen, their skiffs beached, idled. In New York City the steamboat men repaired and painted their vessels, schemed and made new combinations. While the fashionables went to their balls, the price of fuel wood soared, and the almshouse registers lengthened. All up and down the river, from the tiny mountain ponds of the sources to the steepening Palisades, winter hunched and tightened.

Then, toward March, icicles dripped. As the gray snows sank, V’s of geese honked northward. Buds split, streams gushed. In the city the steamboat men watched and waited. Warming rains came, the ice cracked. Warily the first boats churned upstream -- not sleek new racers but stout-nosed, sturdy crunchers, bumping through the ice to Poughkeepsie, nudging to Hudson, grinding amid cheers to Albany, and to the head of navigation at Troy.

But the river was not yet safe. Softened by sun and rain, the ice squeaked and grunted, loosened, thickened, gripped small boats, crushed them, loosened again, jostled, broke up. Slowly, with the tide or against it, in juts and jags the pack crunched down the river, snatched at piers, vessels, piles of lumber, slammed and sloshed its way past Manhattan through the inner harbor and the outer harbor to Sandy Hook and the Rockaways, where it spewed forth into the ocean its captive splintered boats, pier ends, sections of bridges, and the thawed bodies of the drowned.

The river was free.

Boatmen launched their skiffs and ferried passengers. In Troy, merchants schemed to steal business from Albany; in Albany, merchants schemed to steal business from Troy. Sloops, their white sails billowing in the breeze, brought Ulster County bluestone to the city, Poughkeepsie bricks, and Westchester butter. From the canal, steam tugs towed lashed barges sixty at a time with barrels of Rochester flour, Syracuse salt, and potash and pork from Ohio.

With gusto the steamboat men sped their swiftest boats to Albany and Troy, with connections for Canada and the West. Docks bustled, the river towns revived. From Ohio and Illinois, country merchants came to stock up for the season, pray in an elegant church, or visit a big-city whore; they went home replenished and depleted.

By midsummer a fleet of spume-treading vessels, belching pillars of smoke by day and showers of sparks by night, took artists and aesthetes to the Adirondacks. The city fashionables, having drawn the blinds in their parlors, departed for Saratoga, the husbands to drink and play cards, the wives to show off their bonnets, the sons to fall in love, and the daughters to make the right connections. (Back home their less affluent neighbors likewise pulled down the blinds and tried not to be seen on the street.) Weeks later they returned, the husbands sobered by their losses, the wives aglow at having been seen, the sons languid and moony, and the daughters pouting, having not made the right connections.

In autumn fewer day boats plied with thinning crowds. From Iowa and Indiana, country merchants came to order goods for the season, pray, or copulate; they went home graced and sated. In the Highlands the last excursionists oohed and aahed as the beeches yellowed and the oaks blotched brown and red. Soon the day boats stopped, geese honked southward, the night-boat schedules dwindled.

In the far north snow fell on cloud-splitting mountains towering over hemlock and pine. Ice formed on Lake Tear of the Clouds, Feldspar Brook, and the Opalescent River. Bears hibernated, wolves prowled. Ice gripped the upper Hudson, and in the middle Hudson wedged between Bear Mountain and Anthony’s Nose. Canal men docked their barges for the season, boatmen beached their skiffs. The last night boats bumped and scraped to Newburgh, then only to Peekskill, then hugged their piers in the city. From the snow-locked mountains of the north to the wind-scoured Palisades, winter hunched and tightened.

Coming next: New York Hodgepodge 2, in three sections: WBAI and how much truth can we take; getting into the Met at bargain prices (if you have the nerve); and turning a nightingale into a cash cow.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on March 13, 2013 05:29

March 10, 2013

50. WBAI -- again!

Last July in post #16 I communicated my love/hate affair with listener-sponsored WBAI. This is a further communication, a reaction to their latest and seemingly interminable fund drive, where they they ask, beg, implore listeners to donate money, so they can remain a truly independent radio station unbeholden to any corporate sponsors. (Are these drives longer and more numerous than ever, or am I just imagining it?) What's different about this drive is the note of desperation: if they don't raise a hefty sum immediately, they will lose their transmitter on top of the Empire State Building, in which case they will go off the air. As a result, they are appealing above all to prospective "angels" able to give a thousand dollars or more. (In this regard I don't even rate as a cherub.) The crisis is for real; I encourage all who listen to the station to donate in whatever amount they can; the station's continuing existence is in question.

To sweeten the pain of parting with one's bucks, WBAI offers premiums, and it is one of these that provokes this post. The premium is entitled "Great Lies in History" and comprises five DVDs available to anyone donating $250 to the station. (The DVDs were also available individually for pledges of $100.) The five DVDs:

The True History of Marijuana.Cancer: the Forbidden Cure.Who Killed RFK? UFOs and the Military (not the exact title, but close)The New American Century. Having already contributed to the cause, I didn't get any of these DVDs, but their claims -- highly controversial, and in the provocative tradition of the station -- prompted me to appraise my reaction to them. What follows is a poll of one, an effort to determine my rating on the Gullibility Index (an index that I just invented). I have allowed myself one of four reactions: YES (I agree heartily), NO (I disagree), YES/NO (a mixed reaction), and ??? (too uninformed to have an opinion). I'm simply recording here my gut reaction to these assertions, about which I have little or no special information; I am not trying to convert others to my opinion, or to "deconvert" them either. Here goes.

Friend or enemy? Boon or threat?1. The True History of Marijuana. The DVD insists that the hemp plant is beneficial for many reasons, but condemned as a dangerous drug because the medical establishment -- M.D.s and Big Pharma -- want no competition that might threaten their profits. I have little doubt that this last is true, but am mindful of the opinion of another WBAI host, Gary Null, whose pronouncements on health and nutrition I take seriously. Null has stated more than once that marijuana, if smoked regularly, is even more detrimental to health than nicotine. (Incidentally, I have never smoked pot. Ah, what I have surely missed!) So opinion about marijuana varies, and varies widely. My reaction to the DVD: NO.

Friend or enemy? Boon or threat?1. The True History of Marijuana. The DVD insists that the hemp plant is beneficial for many reasons, but condemned as a dangerous drug because the medical establishment -- M.D.s and Big Pharma -- want no competition that might threaten their profits. I have little doubt that this last is true, but am mindful of the opinion of another WBAI host, Gary Null, whose pronouncements on health and nutrition I take seriously. Null has stated more than once that marijuana, if smoked regularly, is even more detrimental to health than nicotine. (Incidentally, I have never smoked pot. Ah, what I have surely missed!) So opinion about marijuana varies, and varies widely. My reaction to the DVD: NO.2. Cancer: the Forbidden Cure. The DVD asserts that there are natural cures for cancer that the cancer industry does its best to suppress, so as to protect its vast profits. I don't know what specific natural cures the DVD espouses, but do know that there is indeed a huge cancer industry that derives immense profits from the current standard treatments, even though they can do harm and don't effect a definitive cure. A personal note: years ago I had surgery to remove a malignant tumor in my colon that was on the verge of metastasizing -- that is, spreading throughout my body. The doctors then urged chemotherapy to lessen the risk of recurrence, but, since I knew that chemo might involve nasty side effects and wouldn't cure me, I opted for a health and nutrition approach instead. I still follow that approach, including in my daily diet soy products, garlic, and cruciferous vegetables (kale, collards, cabbage) that are known to have anticancer properties. A good decision? Well, here I am today, years later, free of cancer. So my reaction to this DVD is YES.

This ...

This ...

... or this? SaletteAndrews

... or this? SaletteAndrews3. Who Killed RFK? As I said in my earlier post on WBAI, the station has never encountered a conspiracy theory that it didn't embrace with fervor and verve. This DVD announces that it can and does name Robert Kennedy's true killer, who isn't the convicted and long imprisoned Sirhan Sirhan. These theories provoke my inner skeptic. There have been so many over the years (we'll meet some more in the fifth DVD), so elaborate, so vehement, so convinced, with an array of impressive spokesmen (and women), but somehow for me they have never quite sounded convincing. If solid facts emerge regarding Kennedy, I might change my opinion, but for now my response is NO.

4. UFOs and the Military. The DVD insists that our military has for years covered up substantiated UFO sightings. Here I simply plead ignorance, so my reaction is ???

5. The New American Century. Here I may be crossing wires, confusing the content of this DVD with other information offered by the station in this fund drive. But WBAI has certainly presented the claim that our government, to get us into wars, has lied repeatedly, inventing or provoking incidents so that it can claim self-defense, as required by the Constitution. Let's have a look at the lengthy historical record and see my response to each claim. I'll mention only the wars where I recall clearly what the DVD asserts. Our history being chockfull of wars, there are plenty to consider. (Was there ever a time when peace-loving Americans weren't at war? If you include wars against the native peoples, never!)

The Mexican War. The DVD asserts that the Polk administration wanted the war and therefore provoked a Mexican attack by sending U.S. troops to what it claimed was the border, the Rio Grande. No argument; this is a matter of historical fact. And did the provocation pay off? You bet! We grabbed a third of Mexico. YES.

The Spanish-American War. Certainly the Hearst papers decried Spanish atrocities in Cuba and beat the drums for war, and Teddy Roosevelt announced, "What this country needs is a splendid little war." He got what he wanted when the battleship Maine, sent to Cuba to protect our interests there, was blown up in Havana harbor. It has long been admitted that the cause of the explosion was unclear, probably not the work of the Spaniards, possibly the result of an internal explosion, or the work of Cuban rebels eager to bring us into their struggle. Cuba today asserts that the U.S. itself blew the vessel up, so as to have a reason for going to war, but I'm not convinced. Instead, I see a heedless rush to war before all the facts were known. And what was the Maine doing down there anyway? So I'll say YES/NO. But did it all pay off? Well, we got Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines and so became a colonial power. The beginnings of empire, one might say, and world power status. If one wants to be an empire, a great big leap ahead. But a leap to what? We'll talk about that another time.

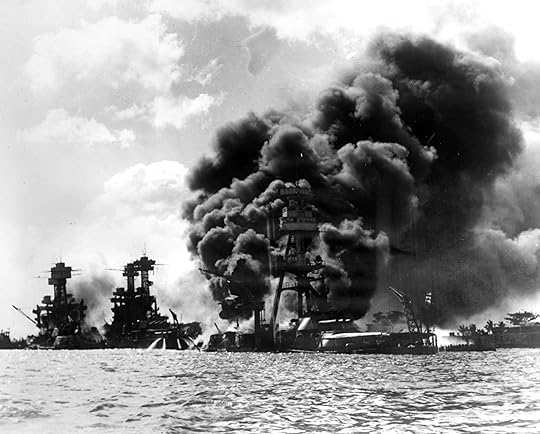

World War II. This is the lollapalooza of conspiracy theories. Because we had cracked the Japanese diplomatic and naval codes (which is true), the theory asserts, President Roosevelt knew in advance that the Japanese were going to attack Pearl Harbor and deliberately withheld this information from our commanders there, so as to get us into the war. It's true that those commanders were never told that war with Japan was likely or imminent, and that they became scapegoats and were summarily removed from command. But I don't buy the conspiracy theory. Why not? Because the war with Japan was going to be above all a naval war, and you can't fight a naval war if your fleet is on the bottom of the harbor. And so: NO.

Did he ...

Did he ...

... do this?

... do this?

The Vietnam War. Yes, it's a known fact, and now not the least bit controversial, that Lyndon Johnson's administration invented an attack on our ships by the North Vietnamese, so as to have a pretext for going to war with them. A resounding YES.

9/11. Here began our war on terrorism. The DVD insists that the neocons planned the attack so as to provoke a war that would let them initiate policies that only such a crisis could make possible. Yes, they did take advantage of the attack to initiate those policies, but I'm not at all convinced that they planned the whole shebang. Another lollapalooza. NO.

Iraq. Again, I think it's clear that the Bush administration lied about Saddam Hussein's weapons of mass destruction so as to get us into war. Also, it was suggested that he had a hand in 9/11, which he did not. Another resounding YES.

So there you have the claims and my response. My tally: YES: 3, NO: 2, YES/NO: 1. A balanced viewpoint, I hope, and not too high on the Gullibility Index. But these answers aren't writ in stone. If more solid facts -- as opposed to intriguing theories -- emerge, I might change my mind. I agree that we've been lied to a lot, and with fearful consequences, but my inner skeptic persists, a stubborn little character who, shunning Cloud Cuckoo Land, refuses to swallow everything that conspiracy buffs put out. History is a very mixed bag; its events are complex, often ugly and depressing, but not easily reduced to simple formulae.

A sobering aside: During the current fund drive WBAI has mentioned Operation Norwood, a proposed CIA operation drafted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1962, when Cuba had gone Communist under the leadership of Fidel Castro. The plan was to create an incident that could be blamed on Cuban terrorists and so justify a war with Cuba. Many incidents were suggested: fake terrorists could hijack a U.S. passenger plane, which would then be replaced by a pilotless plane that would crash, supposedly killing all aboard. (So what would become of the hijacked passengers? Indefinite detention?) Or a U.S. ship could be blown up in Guantanamo Bay, for which Cuba could be blamed. (Remember the Maine!) And so on. President Kennedy rejected the plan, which was never put into operation. But the fact that our military would propose such a project possibly involving loss of U.S. lives is disturbing enough. Score one for the conspiracy theorists! Only on WBAI have I heard about this proposal, which can be confirmed by googling it on the Internet. Need I say more?

So here I am, still a listener and -- modestly -- a financial supporter of WBAI, which I feel free to criticize roundly. WNYC can entertain and inform me, or repel me with its silly games and audience-participation shows, but it can never shock me. Other stations offend, annoy, or bore me with their blatant babble and trivia (WQXR is the exception), so that I avoid them like the plague. But WBAI is uniquely provocative and outrageous; it irks me, teases me, gladdens me. And it's the only station that on occasion makes me think.

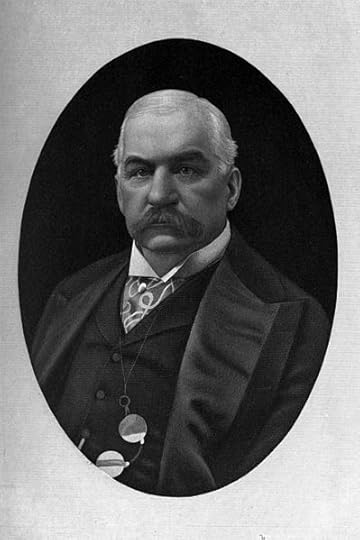

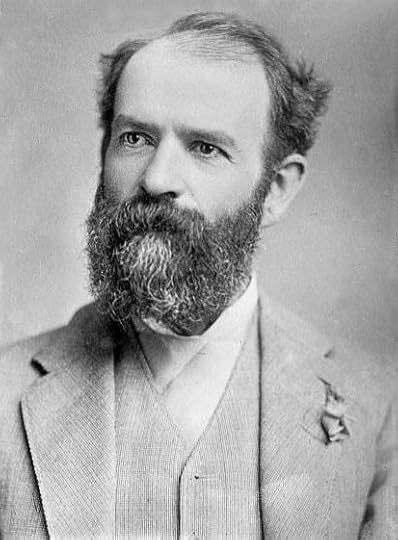

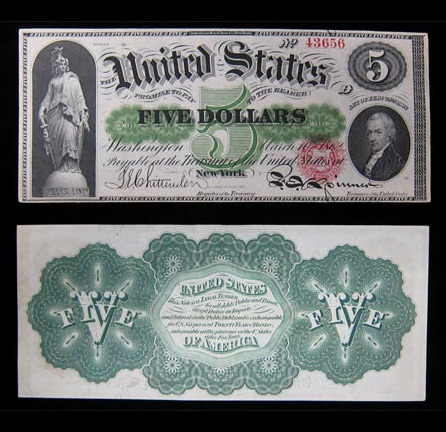

Bank note: My love affair with J.P. Morgan Chase continues. How could it not, when they offer me free candy and pens, and a hand sanitizer as well? Given these amenities and the nicest staff at my branch, who are so helpful in explaining the little fees that the bank has been charging me lately, how could I not overlook their recent $8 billion loss in trading, and now, so the press informs me, their policy of advising clients to make investments more to the bank's advantage than their own? I'm sure it's all a mistake that will be cleared up promptly. Still, I can't help wondering what old J.P. himself would have thought of these shenanigans. He was a tough old guy, impatient of incompetence and failure. But maybe that's irrelevant. After all, free candy and pens ...

Would he have tolerated an $8 billion loss?

Would he have tolerated an $8 billion loss?Or given away free candy?

Final note: I don't mean to use this blog for advocacy, but this is a special case. WBAI is desperately in need of funds; its survival is at stake. I urge anyone who listens frequently to make a donation of whatever size now. It is unique; its loss would be irreparable.

SAVE WBAI!

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on March 10, 2013 04:51

March 3, 2013

49. New York Hodgepodge

This is a hodgepodge of New York experiences, real and otherwise. Don’t look for a unifying theme; there isn’t any, except the wonders and horrors, the quirks and surprises of the city.

New York jokes

These aren’t meant to amuse you; you’ve probably heard them a dozen or a hundred times. But they say something about the New York mentality.

· Tourist: How do I get to Carnegie Hall? New Yorker: Practice, practice, practice.

· Tourist: Who’s buried in Grant’s Tomb? (No recorded response.)

· A young man from the provinces arrives in New York, sets his suitcase down, and announces, “Look out, New York! I’m here to conquer you!” Then he looks down: his suitcase is gone.

A New York myth: alligators in the sewers

Snowbirds returning north from Florida supposedly bring back cute little baby alligators as pets. Then, as the pets get bigger and bigger, they panic and flush them down the toilet. Result: Alligators ranging in the sewers. (But hard confirmation is lacking.)

Wildlife in the city

Speaking of alligators, there is plenty of confirmed wildlife in the city. No, I don’t mean roaches, mice, and rats, our ubiquitous fellow residents, or the wood ticks that show up in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Sanctuary and elsewhere in the spring, or even the magnificent peregrine falcons that nest on tall buildings and make precipitous plunges to seize their mammalian prey. I mean unexpected and surprising creatures, as for instance:

· The muskrats I’ve seen in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Sanctuary.

· The little brown bat that zipped past me once in the North End of Central Park.

· The red fox once reported in Van Cortland Park, though I myself never saw it.

· The raccoon I saw high in a tree in Central Park.

Has this guy been in your garbage lately?

Has this guy been in your garbage lately? In addition to the above, coyotes have been seen in the suburbs north of here and in the city as well, on the streets of Harlem, near Columbia University, and in Central Park, though I have yet to spot one. I thought coyotes were a Western critter, but it seems that there is an Eastern coyote who is common upstate but has adapted to urban settings, since in them he finds all his favorite foods: rabbits, squirrels, cats, small dogs, and garbage. People often mistake coyotes for dogs. Coyotes have long, thick fur, a bushy tail usually pointed down, and erect, pointed ears.

·

Of course I've saved the best till last: copperheads inhabit the Jersey Palisades, just across the river from New York. They and other creatures lurk in the hollows and crevices under the Giant Stairs, a jumble of huge fallen boulders on the Shore Path of the Palisades, a path that I have often walked, scrambling over the boulders, some of which teeter slightly as you scramble. A rough forty-five-minute trek through a unique landscape that you wouldn’t expect here in the East. Copperheads are poisonous, but like most snakes they keep away from humans, so in my noisy scrambles over the Giant Stairs I have never seen one. Also inhabiting the Palisades are raccoons, red foxes, skunks, chipmunks, shrews, moles, and rabbits – all this, just across from the cement and asphalt density, the traffic and the ruckus, of the city.

A copperhead: beautiful, if seen from a distance. Look close

A copperhead: beautiful, if seen from a distance. Look closeand you'll see a black snake as well. Tad Arensmeier

Street cries of long ago

Our streets are noisy with traffic sounds and jackhammer screeches, but street cries of vendors are rare, maybe because they wouldn’t be heard over all that racket. But the early 1800s were different. Here are some of the street cries from that period, uttered by wandering vendors, some with carts, some without:

Here’s your beauties of oysters, your fine fat briny oysters!

Butter mil-leck! Butter mil-leck!

Here’s white sand, choice sand, here’s your lily white sand, here’s your Rockaway beach sand! (Often strewn on floors of taverns.)

Glass put eeen! Glass put eeen!

Sweep ho! From the bottom to the top, without a ladder or a rope! Sweep ho! Sweep ho!

Morburre

MorburreChimney sweeps were common on the streets of nineteenth-century New York, as in Victorian England. Usually a master and his young apprentice roamed the streets together, the master calling out his cry to alert the householders in need of his services. The boy would climb up the chimney with a brush to loosen the soot, and then climb down again to bag and remove it. If he didn't climb properly, he might get stuck in there and not come out alive. (See the illustration below.) Only much later did machines replace climbing boys.

How they worked: the one on the left is in the

How they worked: the one on the left is in theproper position; the one on the right is jammed

and will have to be pulled out, or the chimney

broken into so as to retrieve the body.

Clem Rytter

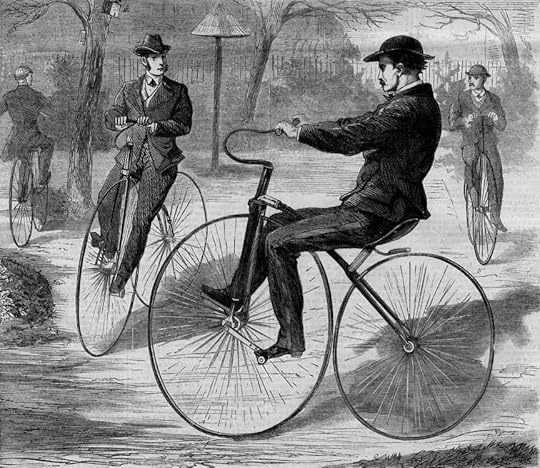

The velocipede craze

In 1869 a new craze from France suddenly swept New York: the velocipede. This was a crude forerunner of the bicycle, though at the time everyone thought it the very latest in personal transportation and amusement. Academies and rinks for teaching and riding the velocipede sprang up all over the city, and hardy young males flocked to them to master this new skill. The wheels were of iron and the saddle rigid, which discouraged long excursions, so most of the riding was done in indoor rinks. Accidents were frequent; the victims could display their wounds in much the same way that today's high school football players show their scars and bruises, heroic mementos of a noble sport.

The spite house

Years ago passersby were puzzled by a four-story row house at East 82nd Street and Lexington Avenue that was only five feet wide. There was of course a story behind it.

In 1882 a clothier named Hyman Sarner who owned several lots on East 82nd Street decided to build an apartment house on his property, which extended almost to Lexington Avenue. Along Lexington Avenue was a narrow strip of land, valueless, he thought, unless joined to the land he already owned, so he set out to acquire it.

Learning that the land belonged to one Joseph Richardson, he offered the gentleman a thousand dollars for the land. But Richardson demanded five thousand, which Sarner thought outrageous. When Sarner refused, Richardson called him a tightwad and showed him to the door. So Sarner built his four-story apartment house anyway, with side windows looking out on Lexington Avenue.

Now came Richardson’s revenge: he would build a narrow four-story building on his strip of land smack against Sarner’s building, thus cutting off the view from Sarner’s windows. A building only five feet wide? His wife and daughter thought he was crazy, but Richardson’s spite was not to be denied; he would live there himself – obesity was not his problem – and rent to skinny tenants.

Within a year the house was built, cutting off the view and light from Sarner’s windows. There were two suites to a floor, each with three rooms and a bath, and stairs between floors so narrow that only one person could use them at a time. To pass each other in the halls, one person had to duck into one of the rooms so as to let the other one pass. Richardson and his wife moved into a ground-floor suite and, amazingly, found narrow tenants who moved in with narrow furniture.

The house quickly became a local legend, inspiring articles and jokes. But when a journalist of pronounced rotundity came to interview Richardson and was told that the owner was up on the roof overseeing workmen doing repairs, he started up the stairs and at once got perilously stuck; alas, the more he wiggled to get free, the more he got wedged in. A tenant from the ground floor tried to help by pushing from below, and a tenant from above who wanted to reach the street began pushing in the opposite direction. Mauled simultaneously from above and below, the journalist finally got the two tenants to desist, then took off his outer clothes and wiggled free, and so proceeded up to the roof in his underwear to conduct an airy interview.

Don’t go to Lexington and East 82nd Street to see this anomaly; it and Sarner’s adjoining building were torn down in 1915 – long after Richardson had died – to make room for a much larger apartment building that could accommodate tenants of whatever proportions.

Footnote: As my partner Bob has reminded me, there is a house in Greenwich Village only nine and a half feet wide, now the narrowest in the city. It is a three-story red-brick house on Bedford Street off Seventh Avenue, built in 1873. Edna St. Vincent Millay lived there in 1923-24. It was evidently squeezed in between two adjoining buildings where there was once a carriage entranceway leading to stables in the rear; no spite was involved.

The offal boat

In the old days of horsepower, before the internal combustion engine, the city’s transportation was mostly horse-drawn, which meant that the city’s streets were often encumbered with dead horses, not to mention cows, and the pigs that ran about freely, scavenging the streets and thus saving their owners the cost of feed. So what happened to all those smelly carcasses, so offensive to eye and nostril? The answer: the offal boat.

Departing a dock at 34th Street in the North (Hudson) River regularly in the 1860s was a small sloop piled high with the carcasses of horses, cows, pigs, dogs, and cats, plus barrels, tubs, tanks, and hogsheads of blood and entrails. Its destination: a bone-boiling plant up the river that would receive this smelly cargo and use it to produce leather, bone (for buttons, etc.), manure, soap, fat, and other products. In one week the sloop disposed of 50 horses, 9 cows, 135 small animals, and 3,100 barrels of offal. The city’s butchers delivered blood and offal from the slaughterhouses; the rest was brought in ten carts by a contractor. In this way the streets were delivered of an odorous impediment that was actually turned into a variety of useful products.

Which prompts me to ask what happens today to all those junked cars and other abandoned contraptions that we would like to make disappear. Where are they, and what becomes of them? Will archeologists eons hence discover the remains of vast automobile graveyards and wonder what strange civilization could have produced such a huge array of junk? Or will all that have crumbled away, leaving only little plastic thingamabobs? I wonder.

Hart Island

Open graves covered with plywood.

Open graves covered with plywood.Photo courtesy of Ian Ference,

The Kingston Lounge.

And what becomes of humans -- the unclaimed bodies that turn up in every big city -- one may also ask. The answer in New York is that, since 1869, they are taken to Hart Island, a quiet, grassy island only about a mile long and a quarter mile wide in Long Island Sound near City Island in the Bronx. This now uninhabited island, at various times the site of a lunatic asylum, a sanatorium, a boys' workhouse, and a drug facility, is the city's potter's field, the final resting place of some 800,000 anonymous, indigent, and forgotten persons who are buried in closely packed pine coffins in common graves, three coffins deep for adults, and five for babies. Some 1500 bodies arrive yearly, about half of them stillbirths and infants who are interred in small pine coffins. "Baby Morales, age 5 minutes," says the paperwork on one; "Unknown male, white, found floating on the Hudson at 254th Street," says another. Burials are done quickly and routinely without funeral rites, unless some spontaneous prayer from a gravedigger.

Note: I have often wondered where the phrase "potter's field" comes from. It is Biblical, saying what the chief priests did with Judas's thirty pieces of silver when, repenting of his betrayal of Jesus, he flung them down on the floor of the temple and went and hanged himself: "And they took counsel, and bought the potter's field, to bury strangers in" (Matthew 27:7). A field used for extracting potter’s clay was useless for agriculture and so was available for burials.

And who are those gravediggers? Inmates from Riker's Island who arrive by boat handcuffed, but then climb down into the trenches to work unmanacled, most of them glad to be away from prison and out in the open air, working in the flat, calm solitude of the island. They are paid all of fifty cents an hour, as is typical of our prison/industrial complex. But they are not insensitive. "Respect, guys, respect!" they caution one another, as they lower the coffins into the graves and then cover them with dirt.

Hart Island is not open to the general public, most of whom have probably never even heard of it, and trespassers face a stiff fine. But family members able to prove their relatives are buried there can arrange visits. This is no easy task, since one has to navigate numerous city agencies to obtain the necessary information. The coffins have no individual markings, but each grave corresponds to an entry in a ledger. If successful, the family members can then arrange to have the remains disinterred and removed for burial elsewhere. But most of the remains are unclaimed.

Southern entrance to the Pavilion, once a

Southern entrance to the Pavilion, once a women's prison, later a drug rehab facility.

Photo courtesy of Ian Ference,

The Kingston Lounge.

What is it like on the island? The few who are allowed to visit have different impressions. One visitor, seeing the crumbling vestiges of earlier installations, called it a dilapidated ghost town; another found it surprisingly peaceful, surrounded on sunny days by an expanse of scintillating water, and serenaded by the distant clanging buoys of Long Island Sound. One hopes, for this last resting place of the unknown and forgotten, that the latter impression is more accurate. But those crumbling vestiges have a haunting beauty that photography reveals: the beauty of abandonment and desolation. I shall never be able to visit this forbidden island, but everything about it breathes mystery.

Second floor of the Pavilion.

Second floor of the Pavilion.Photo courtesy of Ian Ference,

The Kingston Lounge.

Interior of the asylum's hospital.

Interior of the asylum's hospital.Photo courtesy of Ian Ference,

The Kingston Lounge.

Unused pine coffins in the hospital.

Unused pine coffins in the hospital.Photo courtesy of Ian Ference,

The Kingston Lounge.

Source note and invitation: These photos of Hart Island are from Ian Ference’s website, The Kingston Lounge. I urge viewers to access that website and then, under NYC Waterfront, click on Hart Island to see all his haunting photos of the island's crumbling structures.

Next week: New York and Water, the Hudson. After that, Monumental New York. Then steamboats, another hodgepodge, and who knows what.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on March 03, 2013 04:57

February 24, 2013

48. New York City and Water: Sail

New York City has had a two-hundred-year romance with water. It needs it, uses it, loves it. It wouldn’t exist as it is, without water. But in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, one has to ask if this longstanding romance has ended with a kiss of death.

When the Dutch first came to the New World, they found in the southern tip of Manhattan the perfect site for a trading post: a vast harbor, and access to the sheltered waters of Long Island Sound and the river we now call Hudson, which stretched deep into the interior of the continent. They wanted to trade with the native peoples, and this was the ideal spot for a settlement. The result, in 1626, was New Amsterdam, which, unlike many of the Thirteen Colonies, was not founded with a vision of an ideal community, but strictly for down-to-earth, grubby commercial purposes; here, what counted was trade and money. (This of course has long since changed.) Peter Minuit is supposed to have bought the island of Manhattan from the local Indians for $24.00 in trinkets and beads, which has always been seen as a slick bit of fleecing, and an early indication of how white sharpers would diddle the native peoples out of their land. But this figure is a nineteenth-century miscalculation, endlessly repeated; what he really paid was 60 guilders’ worth of goods, a price in line with other such purchases of the time. No real estate bubble back in those days; land was cheap.

And who were the inhabitants of the settlement? The Dutch of course, but also, in time, refugees from Puritan England and the morally stricter New England colonies, plus Huguenots from France, Sephardic Jews, Germans, Italians, Africans (both slave and free), Bohemians, Walloons, Irish, Swedes, Danes, and a sprinkling of Mohawks and other native peoples -- in other words, a real mishmash. And among the mishmash, right from the start, were pirates, prostitutes, smugglers, and every kind of commercial hustler. (This too of course has long since changed.) Clearly, no tight immigration laws here. Eager to build up the population, the authorities let just about anyone in. So right from the start, the inhabitants of Manhattan were a free-wheeling community, trade-oriented, money-loving, enterprising, and above all diverse.

New York, 1671, seven years after the British conquest.

New York, 1671, seven years after the British conquest.How male elegance almost drove the beaver to extinction

What the Dutch were after was furs, and they established Fort Orange far to the north on the site of present-day Albany, where they had greater access to the tribes they traded with. Otter, mink, and even wildcat skins were traded, but above all beaver, the raw material for a durable, high-quality felt especially suited to hat making. A well-brushed beaver hat said elegance, wealth, status; everybody who was anybody wanted one. When the British seized New Netherlands in 1664 and New Amsterdam became New York, the beaver trade continued unabated. The cocked hats of the eighteenth century – those funny three-cornered hats that George Washington and all the Founding Fathers wore – were beaver, as were the top hats that replaced them in the nineteenth century, until, in the 1850s, beaver hats were supplanted by silk.

This is the guy they were after, seen here in

This is the guy they were after, seen here in his element. Cliff

French dandies of 1830 topped

French dandies of 1830 toppedby beaver hats. Which shows why all those beavers had to die. The fur trade could not have existed without the Hudson, which linked New Amsterdam to Fort Orange, and then New York to Albany, in a time when travel by land was tedious, jolting, and often dangerous. But navigating upstream on the Hudson was problematic, since the current flowed downstream, tides reversed regularly, and sudden gusts of wind could drive small craft off their course. The canny Dutch had tried a number of small craft, and after them the English went on to perfect the Hudson River sloop, a single-masted, shallow-draft, fore-and-aft-rigged craft ranging from 60 to 140 feet in length that was especially adapted to Hudson River commerce. Sloops carried both passengers and freight, but the trip upstream to Albany could take as long as three days. Upriver went manufactured goods and imports; downriver came furs, grains, farm produce, and even cattle. Only with the advent of steam did the sloops begin to fade from the scene, though they continued to handle local commerce well into the nineteenth century.

The Clearwater, sailing past Grant's Tomb and

The Clearwater, sailing past Grant's Tomb andRiverside Church. WorldIslandInfo.com So since steam came in long ago, sloops are a thing of the past, are they not? Wrong! The sloop Clearwater sails the Hudson today, advocating greater respect for the environment and a cleaner river. An inspiration of folk singer Pete Seeger and others, it was closely modeled on the sloops of the past, though to find a shipyard capable of building it meant going all the way to Maine. (Ah, those clever Yankees!) I have connected with it several times, sailed on it once for an hour or two, and support it with modest contributions.

How female fashion in the New World kept the textile mills humming in the Old

Decumanus Few New Yorkers are aware of Sandy Hook, the thin seven-mile spit of sandy land that juts out from the Jersey shore to form the southern limit of New York’s Outer Harbor (or Lower New York Bay). In fact, few New Yorkers today are aware of the existence of an Outer Harbor, though in the nineteenth century it was busy with pilot boats providing pilots to guide sailing vessels through the Outer Harbor’s treacherous maze of sandbars, and news boats eager, in those days before the telegraph, to get foreign newspapers and the latest word of happenings abroad. Only when incoming vessels were cleared by Quarantine, an installation on Staten Island, and passed through the Narrows to the busy Inner Harbor, could they tie up at one of the many piers jutting from the shore of Lower Manhattan.

Decumanus Few New Yorkers are aware of Sandy Hook, the thin seven-mile spit of sandy land that juts out from the Jersey shore to form the southern limit of New York’s Outer Harbor (or Lower New York Bay). In fact, few New Yorkers today are aware of the existence of an Outer Harbor, though in the nineteenth century it was busy with pilot boats providing pilots to guide sailing vessels through the Outer Harbor’s treacherous maze of sandbars, and news boats eager, in those days before the telegraph, to get foreign newspapers and the latest word of happenings abroad. Only when incoming vessels were cleared by Quarantine, an installation on Staten Island, and passed through the Narrows to the busy Inner Harbor, could they tie up at one of the many piers jutting from the shore of Lower Manhattan.And what did those incoming vessels bring to this busiest of ports? From Britain came iron pots and pans, steel knives and scissors, dog collars, compasses, thimbles, fencing foils, curtain rods, hammers and nails – just about any manufactured metal object you could name – and even more important, dry goods such as woolens, muslins, calicoes, broadcloth, and what was labeled sheetings and shirtings. And why such quantities of textiles? Because the fashionable lady of mid-century required some thirty yards of material for her dress, while the unmentionables underneath it brought the total close to a hundred yards. Never before or since have women been so abundantly garbed. Clearly, this was no place for Coco Chanel’s petite robe noire of the 1920s, with its emphasis on elegant simplicity, a style still in vogue today.

Godey's Lady's Book, 1850

Godey's Lady's Book, 1850

New York Fashion Week, spring 2007

New York Fashion Week, spring 2007Peter Duhon

But the ladies required more than this. From France came “fancy goods” such as silks, laces, ribbons, embroidered stockings, gold-embroidered bead bags, and the latest hats and bonnets whose price, even in New World imitations, could bust hubby’s budget for a month. So you see the pattern: from Britain, basics; from France, frills. But the ladies needed – demanded – those frills. And their needs kept the mills of Birmingham and Lyons busy.

And what was New York sending back to Europe in exchange? Furs, grain, naval stores, cattle, and above all cotton. Cotton? From New York? Why not from the ports of the South? Ah, because the Southern planters always needed a loan with their next crop as security, and hustling New York commission merchants were happy to supply those loans, but in the process lured all that cotton north to New York, where it would be transshipped for export to Europe, while all kinds of fees were being collected. So were the canny Yankees outwitting those poor planters? Not really. The Yankees lined their pockets, but the planters, freed from the grubby details of business, could sip their mint juleps at leisure, or do whatever, while the slaves looked after the cotton.

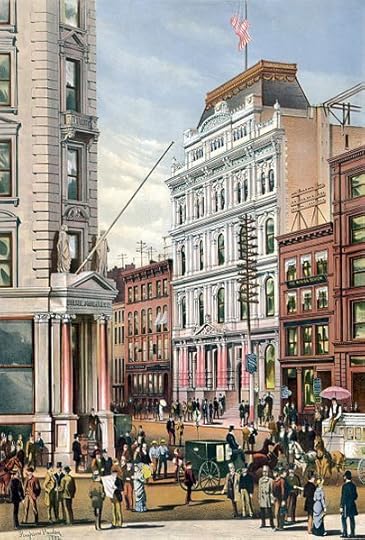

Given such shrewd dealings, is it any wonder that New York by mid-century was a roaring metropolis, its harbor crowded, its docks jammed, the biggest port in the hemisphere, doing business with every corner of the globe? To it, in addition to imports from Europe, came cigars from Cuba, hides from Rio, tea from Canton, Kentucky tobacco and Mexican silver from New Orleans, and buffalo robes from God knows where. And all of it on American ships.

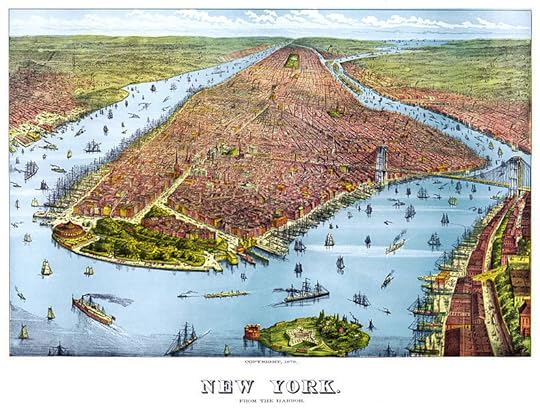

A bird's-eye view of Manhattan, 1879. Both steam and sailing vessels abound.

A bird's-eye view of Manhattan, 1879. Both steam and sailing vessels abound. But the Brooklyn Bridge was in fact still under construction.

Under the bowsprit of sailing ships there was always a figurehead that sailors believed would bring good luck. This tradition can be traced back to ancient Egypt, but by the nineteenth century such figures, always in a forward leaning position, might include patriotic figures, national heroes, and above all female figures, properly clothed or not, usually full-busted, sometimes representing the wife or daughter of the shipbuilder (definitely clothed), or perhaps a mythological figure like Venus or a Naiad (clothing optional). But in England Queen Victoria and Lord Nelson also appeared, appropriately garbed, and in this country, after her triumphant 1850 concert, even Jenny Lind.

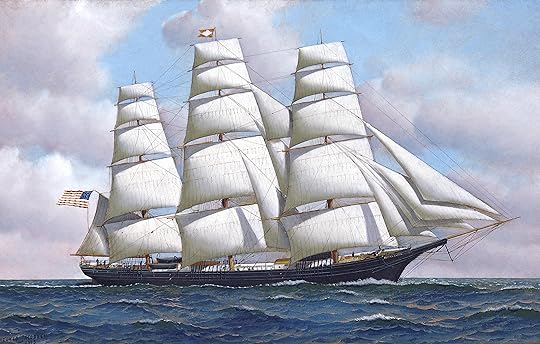

Spectacular among the ships in New York harbor in the 1850s were the clipper ships, with a sleek slender hull, sharp bow, raked masts, and vast expanse of sail, small, swift vessels especially suitable for carrying low-volume, highly profitable goods – tea, opium, spices, people, mail – over long distances. The departure of a clipper for California or Canton was a major event, watched by crowds at the Battery, eager to see the glistening sails catch the wind, while the crew sang sea chanteys -- the words often raucous -- as they went about their tasks. Averaging 250 miles a day – far more than the ordinary sailing vessel – and under favorable conditions even 400, the clippers in record time brought perishable tea from distant Canton to the thirsty palates of Gotham, and delivered eager prospectors to California so they could indulge their lust for gold with the least delay. (Few of them came back rich.) Both the China trade and the California trade meant rounding Cape Horn, which in summer involved making way against snow, sleet, high waves, and fierce, shrieking winds. But when one clipper caught a wind dead astern all the way across the less formidable Atlantic, it reached Europe in an amazing five days, the standard time for the transatlantic steamships of the twentieth century.

The Flying Cloud, which in 1851 made the run from New York to San Francisco via turbulent

The Flying Cloud, which in 1851 made the run from New York to San Francisco via turbulent Cape Horn in 89 days, 21 hours. Typical of clippers are the jet-black hull, towering masts,

and acres of sail.

After they had had their moment of glory, from the late 1850s on the clippers were doomed primarily by the advent of steam. The magnificent Flying Cloud, pictured above, ended up a New Haven scow tugged up Long Island Sound with a load of brick and concrete by a lowly tug, the vessel's faded beauty often buried in the tug's filthy smoke. (Moralists are free to make a short homily here.)

Another type of swift vessel in demand in the 1850s was the schooner, whose speed might let it outrun any British warship prowling off the coast of Africa. And why would this be necessary? Because New York in the late 1850s was the center of the illegal pre-Civil War slave trade, taking slaves from Africa to Cuba, a trade that the British Navy was trying to stop. Few New Yorkers today are even aware of this dark chapter in their city's history, but the records of the time leave little doubt. How the Lincoln administration finally ended this long tolerated trade will be told in a future post.

The splash of two great celebrations

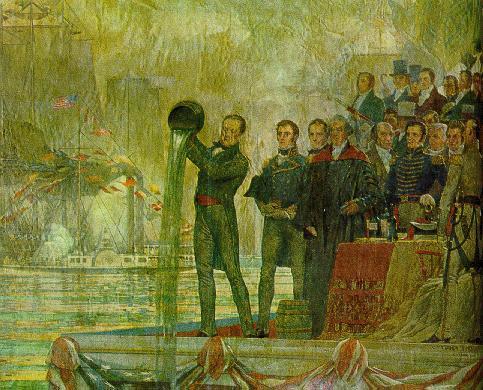

New Yorkers have always loved parties, including civic ones. Two great celebrations marked the city’s romance with water in the nineteenth century. On October 25, 1825, the whole state celebrated the opening of the Erie Canal, which linked Lake Erie to the Hudson, the Great Lakes to New York and the Atlantic. Immediately a cannonade by canons placed at intervals all along the canal and the Hudson resounded, booming all the way to New York City to announce the event. (Noise pollution was not an issue in those days.) Governor DeWitt Clinton, long a champion of the canal in the face of much opposition, led a flotilla of canal boats that traveled the length of the canal from Buffalo to Albany, and then, hauled by tugs, down the Hudson to New York. In New York, when he arrived ten days later, the governor ceremonially poured water from Lake Erie into the city’s harbor, symbolizing the Wedding of the Waters. Nor was the celebration premature or ill advised; this linking of the Middle West to the Atlantic coast greatly reduced the cost of transporting goods, and helped New York become the biggest and most prosperous port in the hemisphere.

The Wedding of the Waters, 1825

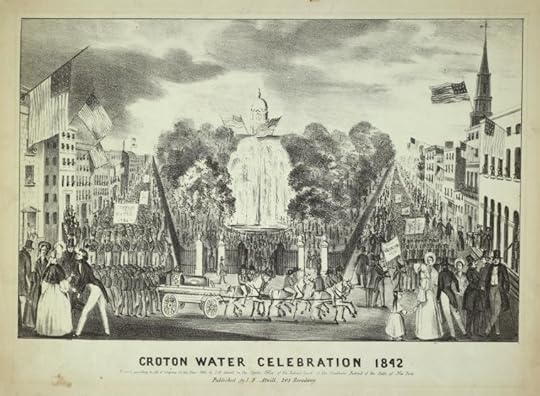

The Wedding of the Waters, 1825If you think that was quite a party, wait till you here about this one. Because commerce and prosperity are all very fine, but there's nothing like a flush toilet and a hot bath in your home. On October 14, 1842, the city celebrated the opening of a municipal water supply system that brought water from the Croton River, many miles to the north, into a reservoir on the site of the present public library on 42nd Street. The event was celebrated with a hundred-canon sunrise salute, tolling church bells, speeches, the singing of an ode, and a five-mile-long parade of dignitaries, soldiers, volunteer firemen, butchers, trade unions, college faculties, ladies’ auxiliaries, and blaring bands, all of them passing the fountain in City Hall Park that was spurting skyward a fifty-foot plume of water. Concluding the ceremonies was a cold buffet for invited guests at City Hall, where – astonishing for bibulous Gotham – the only lubricants were Croton Water and lemonade. Now at last New Yorkers – those willing to pay a water tax – could have running water in their homes and enjoy there the voluptuous pleasure of a bath. But the urge toward temperance proved momentary; by the next day New York had returned to its sodden ways.

On this happy note I'll end this first account of New York's love affair with water. Future posts will tell about the coming of steam and the marvels and follies that resulted; New York City's history is rarely dull. But before that there'll be a post offering a hodgepodge of New York anecdotes and lore, ending with a forbidden island with over 800,000 graves -- an island that most of us will never set foot on, unless we are taken there in handcuffs.

(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on February 24, 2013 05:26

February 17, 2013

47. Discovering New York: Three Stories

Here are three stories of people coming to New York City in the 1950s: their first impressions, their adjustments, their adventures and misadventures.

The magical city

My partner Bob grew up in Jersey City, which in those days was a blue-collar town and, in the sections he knew, predominantly white. He wasn’t unhappy there, but by the early 1950s he sensed in it a certain sameness, whereas just across the Hudson was something strikingly different: a magical city, New York. And so, at the tender age of thirteen, this inquisitive eighth grader embarked on a series of explorations. Sometimes he took his younger brother with him, but usually he went alone. He preferred going alone: more freedom. So off he went, wearing a blue-and-white terry shirt and chinos or dungarees.

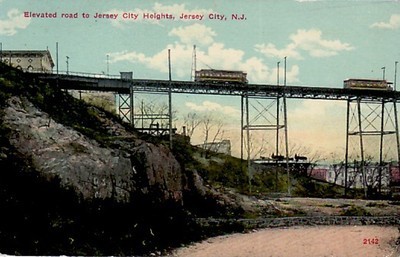

The adventure began in Jersey City itself, when he took the trolley to the Hoboken dock. The trolley, with its clanging bell, had an old-fashioned charm for him, and approached the terminal on a high trestle that was just a bit scary. But soon he was in midstream on the ferry, with New York’s skyscrapers looming in the distance. Landing at Barclay Street, he explored the Washington Market, a huge enclosed structure with hundreds of vendors, where carcasses of duck and pheasant and geese and venison and bear were strung up in the stalls, and buyers thronged, and stands in the corners of the market offered roast beef sandwiches and beer. (He was underage, so no beer!) Nothing like this in Jersey City!

Walking on through what is now the World Trade Center site, he passed dozens of little shops and came to Saint Paul’s Chapel on Broadway, the city’s oldest church (1766), its classical Georgian portico topped by an octagonal tower, and next to the church a cemetery with hundreds of worn gravestones. Inside he found a complete contrast with all that was happening outside: elegant architecture, chandeliers, space, quiet. Above all, in the heart of this bustling metropolis, quiet.

Jean-Christophe Benoist

Jean-Christophe BenoistGoing on from there, he would come to the old City Hall, a gem of Federal architecture, and its park, with the Brooklyn Bridge looming nearby. Often he would have coffee across the street at the Park Place automat, not noted for elegance but suited to his limited budget. After that he went to Foley Square, where at the top of steep steps the courthouses rose impressively, fronted by Corinthian columns.

TEAM TOM

TEAM TOM And then to Chinatown, the most congested section of his walk, where not only the people looked different, but he was baffled by signs in a strange language, indecipherable jabberings with weird intonations, and groceries displaying hunks and slices and heaps and sprouts of foods that were totally unfamiliar. This was his first immersion in another ethnic group, another culture. Once again, nothing like it in the Jersey City he knew.

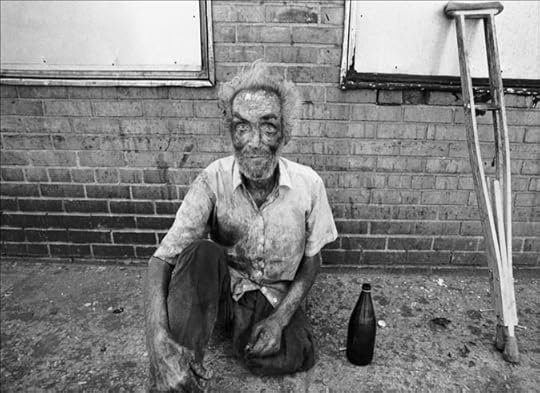

Along the Bowery there were pawnshops, flophouses, pushcarts, cheap restaurants with their bargain prices conspicuously displayed, bums sprawled on the sidewalk, and – an invitation that he would some years later accept – a cabaret advertising Sammy’s Bowery Follies. The Bowery was shabby and down-and-out – another stark contrast after the courthouses and City Hall -- but he didn’t feel threatened.

Gerhard Vormwald

Gerhard Vormwald

From there he walked to Cooper Union, or took the Third Avenue Elevated, which he came to love – to the point of riding on the very last train in 1955. The

used bookstores along Fourth Avenue between 9th and 14th streets he also loved, and Greenwich Village as well, which was less commercial then than today and mostly residential, quieter, with an atmosphere that he considered bohemian; artists and writers would be happy there.

For lunch he usually resorted again to an automat, probably one of the Horn & Hardarts found all over the city, self-service restaurants where you surveyed the array of foods offered in little glass-fronted compartments, made your choice, inserted coins in a slot, raised the hinged door, took the dish out, and carried it to a table. A bit impersonal, but convenient, quick, and cheap.

A New York automat.

(Surprisingly, the automat was not an American invention, but an import from Germany in 1902. There were forty Horn & Hardarts in New York at one time, but in the 1970s the automats were undermined by two developments: the coming of the fast-food restaurant, and inflation that raised prices to the point where it was no longer practical to insert coins in the slots; dollars were needed.)

Often he had another coffee in the Café Figaro at the corner of MacDougal and Bleecker. Or sometimes he would go to the Lower East Side to see Delancey Street with the busy stands selling clothing on the sidewalk, and have coffee and a snack at Katz’s Delicatessen, which still exists today, when so much from back then has vanished, much of it to make room for the ill-fated World Trade Center.

When he took a PATH train back to Jersey City, he was saturated with the excitement, bustle, and diversity of magical New York, though not unhappy to be going home, since he knew he would be coming back again many times.

Of bluey blues, bagels, and martinis

My own discovery of the city was very different. Growing up in a suburb of Chicago, I had often visited the Loop, so I had had many glimpses of a big city and its surging crowds. I came to New York after two years of study in Europe, so I was constantly comparing it to European cities. Returning by boat from France, I experienced the harbor as all new arrivals then did, and was dazzled by the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan, looming up like nothing I had seen in Europe, and, running between them, deep, deep canyons of streets. Clearly, this was a New World, bold, unsubtle, dynamic, unencumbered by the clutter of the past.

I came to New York for the most practical of reasons: a scholarship for graduate studies in French at Columbia University. So while Bob was exploring monuments and communities all jammed together at the lowest tip of Manhattan, I was experiencing the campus of a huge university and exploring a different way of life. I was lodged on the fifteenth (the topmost) floor of John Jay Dormitory, I ate in the ground-floor cafeteria and attended classes in nearby buildings. But I was learning a lot more than what my classes offered.

The Columbia campus today, little changed from the early 1950s. Looking north from Butler Library

The Columbia campus today, little changed from the early 1950s. Looking north from Butler Librarytoward the classical elegance of Lowe Library, which is now used for administrative purposes.

Getty Hall

Sartorial elegance – or at least conformity – was requisite. “Don’t wear any browny browns or bluey blues,” a new friend advised me, when I was shopping for a jacket or suit. “Don’t be one of those!” “Those,” presumably, were oafish rubes from the provinces who sported gaudy colors and thus proclaimed their lack of New York sophistication. And my friend Ken informed me imperiously, “When shopping for a shirt, you don’t go just anywhere; you go to a shirtmaker!” By way of demonstration he took me to a pricey men’s clothing store where the well-heeled shopped; admittedly, the shirts there reeked of elegance and taste. Ken himself, having a slight build, got most of his clothes from the boys’ department at Brooks Brothers, shrewdly combining elegance and a budget. No such stratagem was available to me, nor was I drawn to such esoteric realms; in Brooks Brothers I never set foot. But as a child of the Midwest whose wardrobe, after two years of student living in Europe, was, to put it mildly, shabby, I had a lot to learn, and mentors were not lacking. This was, of course, long before the peacock revolution of the 1960s, when men’s clothing erupted – briefly -- into a rainbow of colors, and Ken himself would sport rings on all his fingers; back in the 1950s when I first experienced New York, restrained taste was still the rule.

Friends of mine, fresh baked. But there are bagels

Friends of mine, fresh baked. But there are bagelsand bagels. Here, as everywhere, quality counts.

Ezra Wolfe Another thing that struck me was the prominence of Israel in the news. Many of my friends were Jewish, and I was soon absorbing and even using a host of phrases new to me: chutzpah, mishegosh, shicksa, goyim, and the names of all the Jewish holidays, while at the same time having my first taste of a bagel and a blintz. And Jewish jokes abounded: the Jewish lady in Miami Beach who shouted, “Help! Help! My son the doctor is drowning!” In fact, so many jokes opened with the phrase, “There was this Jewish lady whose son was a doctor,” that everyone but me would already be laughing. So it went. “I want to be Jewish!” I finally announced. “Because all my friends are Jewish.” (A slight exaggeration.) “In that case,” said a young woman friend with a knowing smile, “you’ll have to have a bris.” Smiles all around. But by then I had a good idea of what was involved and could explain that, being a hospital baby, I had already undergone the procedure, albeit with a shocking lack of ritual.

My enemy.

My enemy.Imbibing was another part of the New York way of life; every social occasion required it. Scotch and very dry martinis were in vogue and, not knowing better, I went along. One martini, I soon learned, relaxed me; two made me everyone’s friend and a brilliant wit; three meant immediate befuddlement and, the following day, a nasty hangover. There was simply no such thing as a single martini; they were by nature serial. As a result, one evening I had to leave a party early and go home, and on another occasion I saw the double bill of Tennessee Williams’s Garden District and Suddenly Last Summer float by me in a haze. In time – a very long time, alas -- I learned to shun martinis, a ban that continues to this day.

I was never completely a New Yorker; maybe my Midwestern roots ran too deep. My mother once, having met my friend Ken, promptly informed me, though without a hint of censure, “He’s very New York!” I doubt if anyone has ever said that of me.

How a naive Midwesterner was plunged into the New York art and design world

Our friend John (for another of his adventures, see post #41) tells how, an

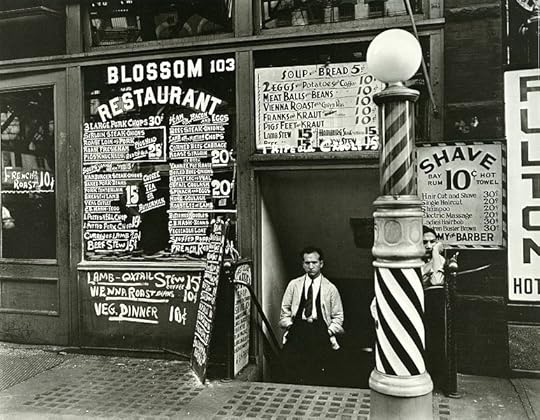

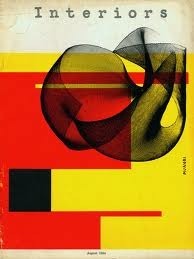

innocent in every way, he left his home town of Minneapolis and came to the city in June 1951, fresh out of college with a B.A. in English and vague hopes for a writing job. On the train he met a young woman whose sister was a designer in the city, and through the sister he heard of Interiors magazine and a possible job there. Arriving in the city, he stayed briefly at a YMCA and then, seeing an ad in the Times where "twelve Christian gentlemen" in Jackson Heights -- wherever that was -- were looking for another roommate, he answered the ad and ended up in distant Queens, with twelve guys who shared a big apartment and had a room to let. Then, having settled in, with the spunk of innocence and no knowledge of interior design, he rushed to apply for a job at Interiors.

It was a hot summer day and, having only one suit, a heavy wool one appropriate for the wintry rigors of Minnesota, he wore it and sweated profusely. Furthermore, his blond crewcut and tie with zigzags situated him, as he now realizes, at the antipodes of New York sophistication. Going to the magazine’s office on East 50th Street, just across from Saint Patrick's cathedral, he applied. The magazine’s managing editor, a woman named Magda, entered the waiting room – stomp, stomp, stomp – with a heavy tread and a look of being very, very busy. Her stomp and her appearance were, to put it mildly, formidable. Slightly overweight with red hair in severe braids wrapped tight around her head, and plainly dressed with no attention to fashion, she exuded a kind of Old World funkiness. With a look of having little time to waste on a lowly applicant, she led him into her office, confirmed that there was indeed an opening, gave him a book entitled Designing Tapestry, and told him, “Take this book and bring me a review in twenty-four hours!” That said, she waved him away. John rushed off eager to do as instructed, the only problem being that his mind was uncompromised by any knowledge of design or tapestries.

It was a hot summer day and, having only one suit, a heavy wool one appropriate for the wintry rigors of Minnesota, he wore it and sweated profusely. Furthermore, his blond crewcut and tie with zigzags situated him, as he now realizes, at the antipodes of New York sophistication. Going to the magazine’s office on East 50th Street, just across from Saint Patrick's cathedral, he applied. The magazine’s managing editor, a woman named Magda, entered the waiting room – stomp, stomp, stomp – with a heavy tread and a look of being very, very busy. Her stomp and her appearance were, to put it mildly, formidable. Slightly overweight with red hair in severe braids wrapped tight around her head, and plainly dressed with no attention to fashion, she exuded a kind of Old World funkiness. With a look of having little time to waste on a lowly applicant, she led him into her office, confirmed that there was indeed an opening, gave him a book entitled Designing Tapestry, and told him, “Take this book and bring me a review in twenty-four hours!” That said, she waved him away. John rushed off eager to do as instructed, the only problem being that his mind was uncompromised by any knowledge of design or tapestries.The next day he was back in her office with his review. Looking as busy as ever, Magda gave him a cursory look, then took the review and read it. Nervous, John waited in suspense for the verdict. To his surprise, her features softened. “You write very well,” she said. “I have others to interview, but you are definitely in the running.” Again, she dismissed him.

Over the next few days John was going to other interviews – none of them promising – or simply wandering about gaping at big buildings like the Minnesota naïf he was. Then, after a week had passed, she phoned him: “John, the job is yours. You lack experience, but we’ll train you. You can learn.”

John was elated: on his very first try, he’d landed a New York job that involved writing! If the pay – fifty dollars a week -- wasn’t princely, neither were his qualifications. His first assignment for the magazine was to write a three-or-four-page section presenting small news items from the rich and fascinating world of interior design.

A few weeks later he learned from someone in the office that, just when he was being interviewed, there had been another applicant for a job at the magazine: a journalist named Ada Louise Huxtable, who hoped for a somewhat more elevated position than the one John got. And why had he been hired, and not Ms. Huxtable? Because she was overqualified and he was underqualified, and underqualified was just what they wanted: someone new to the game whom they could train, while paying an appropriately measly salary, and not the substantial sum that Ms. Huxtable would have expected. The publisher, John learned, was stingy.

[image error] John worked for Interiors for five years, acquiring experience and writing reviews of interior design installations. His relations with the overbearing Magda ran smooth at first, and he noticed how, when an important visitor came calling, she could be a fountain of charm. But when the top editor died and Magda pressured the publisher into naming her as his successor, and John was promoted to managing editor, that relationship changed. A workaholic, Magda was desperate to keep her job, and now eyed John – and for that matter everyone else – warily, as if they were out to snatch that job away from her. Yet John, harboring little ambition, was perfectly satisfied with the job he had.

A byproduct of the magazine job was entry into the world of art. The magazine had connections with prominent artists and critics – Andy Warhol did covers for them – and John got to know a number of them; to this day he is knowledgeable about the New York art world and maintains contact with several artists or their widows. But when he got a hunk of money for an article on Playboy, he quit his job and set off to explore the Old World wonders of Europe. Happily, in those days the dollar went far. A hopefully relevant aside: Beginning as a journalist, Ada Louise Huxtable went on to become this country’s most noted critic of architecture and in 1970 won the first ever Pulitzer Prize for criticism. She loved cities and was a great preservationist, lamenting the demolition in 1964 of the old Penn Station, a Beaux-Arts masterpiece, to make way for the fourth incarnation of Madison Garden. “Not that Penn Station is the Parthenon,” she wrote, “but it might as well be, because we can never again afford a nine-acre structure of superbly detailed travertine [a kind of limestone], any more than we could build one of solid gold. It is a monument to the lost art of magnificent construction, other values aside.” I recall my own shock when, soon after the demolition, I saw a photograph of the station's imposing columns lying abandoned in a field in New Jersey, soon to be used in a landfill in the Meadowlands. But the loss of this architectural treasure, probably unappreciated by most commuters as they hurried through it, gave a hearty boost to the budding preservationist movement in the city.

The main waiting room of the old Penn Station:

The main waiting room of the old Penn Station: high-vaulted classical magnificence.

And then ...

nyc-architecture.com

nyc-architecture.com(c) 2013 Clifford Browder

Published on February 17, 2013 05:52

February 10, 2013

46. The Great Erie War, part 2.

2

Mr. Fisk again, properly posed and sedate.

Mr. Fisk again, properly posed and sedate.But the unwaxed mustache suggests that this

photo antedates his acquaintance with Miss

Mansfield. At Taylor’s Hotel in Jersey City, Jim Fisk experienced three glories tinged by one passionate longing. It was glorious when, piqued by news of the first absconding railroad in history, lawyers, messengers, brokers, confused Erie employees, and every ragtag and bobtail of Wall Street and the press swarmed across the river to New Jersey to be met in the downstairs lobby by Director James Fisk, Jr., aflash in a waffle-weave suit with rings and cuff links aglitter, who funneled reporters to the bar, then up to the Erie suite. Awaiting them there was a table stocked with goblets and prime Havanas.

“Gentlemen, we welcome that great lever of opinion, the press. They only who do deeds of darkness shun the light. In fighting the injustice of New York justice, we’ve vowed to show pluck to the backbone. Our battle is a crusade against monopoly and therefore” – he waved his gem-studded hand – “in the interest of the poor!”

It was glorious to run a railroad by telegraph, issue communiqués, and with reporters listening, to give orders, call councils of war. And it was glorious three times a day to banquet in a special dining room on Vanderbilt’s money, munching quail on toast and oysters with champagne amid quips, jokes, puns, bursts of song, and a cry of No Surrender. (Only Uncle Daniel sat apart.)

The passionate longing that tinged these roils and revels concerned the person of Miss Helen Josephine Mansfield, lately installed on Twenty-third Street, from whose eyes like wet stars, and purple-black and lustrous pink-plumed hair, Director Fisk had rarely till now been parted. Even while issuing orders, scanning telegrams, or downing woodcock and wine, he envisioned his soul and pillow mate corsaged in her carriage, promenading, bust to the breeze, or at home clad only in a crucifix, a plush-lipped, peachlike Eve. He itched, bristled with love.

Jay Gould, sunken-chested, with a pianissimo voice and large dark quiet eyes, either glazed and distant or fixed and piercing, betrayed no lusts or pangs as he sat through Erie’s councils, his countenance masked by the bush of an ink-black beard. His only gesture was the tapping of a pencil, as his wiry, fine-strung mind reckoned cannily each Erie director’s share in the Vanderbilt pie.

Daniel Drew nursed in his innards a fierce longing for comforts left behind: his slippers, his steak and potatoes, his Saint Paul’s pew, the snug back room at Groesbeck’s, and spattering over him, the scouring voice of his wife, who for forty-eight years had kept him to the mark. He was raveled out by the jibberjabber of endless councils of war, and by Jimmy’s champagne dinners, whose songs and blasts of mirth jarred him awake as he sat off hunched in a corner, trying to doze. (How could he join those feasts where spirits gushed and grace was never said?)

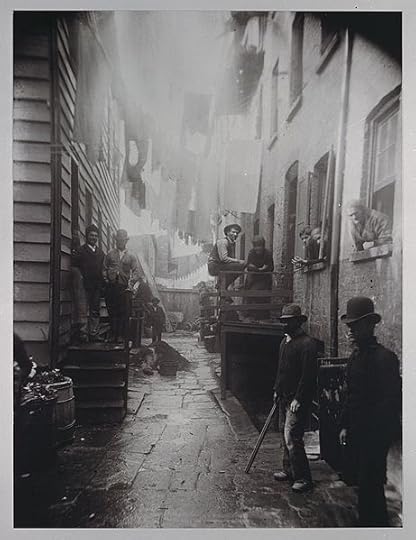

Here, at their home base in Manhattan, are the type of

Here, at their home base in Manhattan, are the type ofcharacters whose presence in Jersey City so terrified

Daniel Drew. Was his fear justified? On the fourth day of exile came dire news: forty man-crunching New York City roughs had arrived in Jersey City by ferry, straggled to the Erie depot, poked about. Finding themselves outnumbered by Erie detectives and clerks, they had departed, announcing that the raid had been organized in a notorious Eighth Ward gin mill, where certain parties had offered them fifty thousand dollars to kidnap Daniel Drew!

At Taylor’s Hotel these tidings disrupted the midday feast. Startled awake from his doze, Uncle Daniel felt a quick, hot jab of fear. Would Cornelius Vanderbilt – the wrastler, the thunderer of Harlem Lane – being pinched in purse and pride, stoop so low, play so foul? Vanderbilt, who had bellowed more than once that the law was too slow for him – who, when his wife resisted moving back to Manhattan from her beloved Staten Island, was said to have locked her up in an asylum until she changed her mind? Would that tyrant, that Samson of finance, resort to violence? Yes, Drew concluded, yes! The roughs, having scouted about, would return by night; he quaked for limb and life.

While Jay Gould paled at the news, his stomach churning, and the other directors sat befuddled, Jim Fisk leaped to the fore. “Inform the police chief! Call up the militia! Uncle Daniel, stand back from that window – don’t let yourself be seen from the street!”

Couriers ran, telegraphs clicked, a conference was called.

“Wait!” cried Fisk, dabbing his chin with a napkin. “Sudden emotions are dangerous! Gould’s stomach is delicate. Let him finish that quail. He’ll need it to sustain him in the perils before us. Vanderbilt must be desperate. There’s bloody work to do!” All this within the hearing of the press.

By nine that evening the entire Jersey City police force patrolled on the alert, under instructions to rush to the hotel, should rockets be fired from the windows. Under Fisk’s personal command, fifteen picked men armed with clubs and revolvers were presented to the object of the “grab.”

“Uncle Daniel,” said Fisk with a grin, “these men will take care of you. They look like they can do it.”

Drew, eyeing the weapons with a nervous smile, thanked them faintly; the men saluted smartly.

Backing them up, Fisk announced, were three twelve-pounders on the docks, the Hudson County Artillery in reserve, and -- unique in the annals of railroads! – a navy of four small boats on the river manned by crews with rifles. Before those bruisers could get to their prey, Erie would fight to the very last man!

Dazed, nodding feebly at vows of No Surrender, Uncle Daniel retired to his room, double-locked the door, and plugged the keyhole with cotton. All Fort Taylor and all Jersey City braced for the attack. Long hours passed. Uncle Daniel prayed, listened intently, and finally, fitfully slept. But no rockets burst in the sky, no rifles crackled, no cannon boomed; the night passed untroubled.

“A most ridiculous state of excitement!” pronounced the Times; “Stuff of romance,” said the World; “A desperate attack!” insisted the usually cynical Herald. For three days the police kept watch and Erie employees were marshaled as reserves, while Erie’s treasurer hugged the premises. Gradually, the kidnap scare abated. Heartened by letters of support from Erie friends and workers, on the fourth day the Old Bear ventured forth -- by daylight, well escorted -- for a short walk into town. Crossing his path came Miss Helen Josephine Mansfield, with servants carrying luggage, parasols, and a caged canary, summoned by Fisk from New York to be installed in a room of her own smack in the Erie suite.

In the Erie suite? Jay Gould and Uncle Daniel, both conventional married men, must have protested vehemently: a fancy woman planted in their midst, when they were up to their ears in a crucial struggle, with hordes of reporters nosing about! But Jim Fisk only winked and grinned.

Miss Mansfield, whose abundant charms

Miss Mansfield, whose abundant charmsenraptured James Fisk, Jr., even to the

point of importing her to Jersey City. Thereafter, from Miss Mansfield’s room by day came perfume and an avian descant, and by night, perhaps catching Uncle Daniel at prayer, delicate hints of carnal festivities. Thanks to Jim Fisk’s liberality with liquor, journalists confined themselves to veiled remarks in their articles about the home comforts with which the directors beguiled the weary hours, but the Old Bear was mortified. Never had he dreamed that for fleecing Cornele of eight millions he would be lodged cheek by jowl with a fancy woman and all but witness the grossest fornication. In the caverns of his mind the cry of No Surrender, never resonant, dwindled to a whisper.

Uncle Daniel's exile had come at the most awkward of times. He had yet to deed the grounds and convey his endowment to the seminary, a matter he had meant to see to soon at the first formal meeting of the seminary’s board of directors – a meeting he couldn’t possibly attend, without exposing his person to the direst threats. What must the gentle Methodists be thinking, having already thanked him abundantly for gifts that had yet to be gifted? He wallowed in chagrin.

The very next day came fresh warnings of an assault by New York roughs; stores closed and volunteers rushed from the suburbs, till a hundred men guarded Fort Taylor, with two companies of state militia in reserve. On Jim Fisk’s orders Uncle Daniel was locked in his room with six hulking whiskey-scented bruisers, black cigars planted in their teeth, lest the old gentleman be snatched out the window by stealth. All through the night, unnerved by ungodly talk and the taint of liquor and tobacco, Uncle Daniel watched, listened, quaked. But the long night passed unvexed.

Over the next few days, while seedy men in derbies slouched about, and Commander Fisk, strutting, barked orders, and to throngs of journalists vowed never to be taken alive, Uncle Daniel, guarded from thugs by thugs, began to suspicion a cruel and shameful hoax. Had Vanderbilt wanted to cop him, he would have done it quick and clean. Why then these alarms? Didn’t Jay and Jimmy trust him? Did they fear he might talk to Cornele? Talk to Cornele … Planted in his brain, the idea took quiet root.

The next Sunday -- informed by his lawyers that under New York law no civil summons could be served on the Sabbath -- he slipped over on the Weehawken ferry, took a cab to Washington Square, knocked, was shown to an upstairs room. There loomed the Commodore, his friend and enemy of almost forty years. The Commodore’s blue eye ran him through.

“Drew, you was a damn fool to skedaddle off to New Jersey!”

“I’ll allow as how I’m circumstanced somewhat awkurd.”

“I’ll keep my legal beagles at the lot o’ you, till you fork that money back.”

“Naow Cornele, mebbe we kin compromise this, old friends that we be.”

“You owe me eight million dollars!”

“Two, Cornele, jist two.”

So it went for an hour, the Commodore barbed and bristly, Uncle Daniel mitteny and soft. What exactly was said is unknown, but they parted having agreed to meet again. The Commodore was surely thinking, I'll worm little Erie secrets out of him, then big ones, then everything, and Uncle Daniel was perhaps reflecting, Them as grinds enough together ends up rubbin' smooth. In the Great Erie War, treachery leaved and bloomed to the first scrawny hatching of the dove of Peace.

3

After ploys and counterploys by thirty well-paid counsel in fine whack and kilter, followed through five courtrooms by clerks toting heaps of ever thickening documents tied with red tape;

After fulminations from Judge Barnard, white topper raked at an angle as he whittled at a pinewood stick on the bench, leaving little mounds of shavings on the floor, while presiding over a legal fandango where he himself got enjoined, and being spied upon by Erie, boasted of hiring spies of his own;