Clifford Browder's Blog, page 40

July 5, 2015

187. Apothecaries and the Charms of Belladonna

Big wide-mouthed apothecary jars of another time, with glass stoppers and bold labels reading

CARDAMOMCAMPHORBELLADONNAASAFOETIDABENZOIN

A host of smaller brown bottles with similar labels on a table, perhaps a medicine chest, that has seen better days. An outiszed mortar and pestle, and a number of glass tubes and receptacles probably used to distill medications. Metal canisters labeled ALUM and, intriguingly,

CHOICEBOTANIC DRUGSPRESSED

Apothecary jars

Apothecary jarsIn a protective glass case, antique scales. What looks to be an old radio, and another large object I can’t identify. And, as the centerpiece of the display, a huge prescription book, the edges of its pages not yellow but brown with age, open to scores of prescriptions scribbled in an indecipherable hand, but whose year, if you squint and look closely, can be made out: 1917. And in bold print at the top of each prescription, FRANK AVIGNONE & CO.

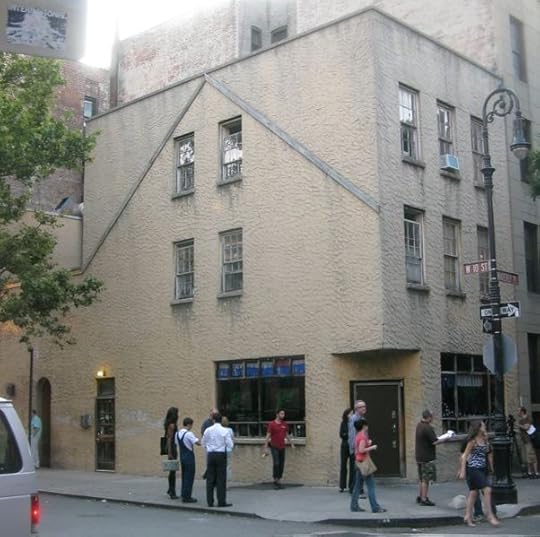

Such is the current window display at Grove Drugs at 302 West 12th Street, but a couple of blocks from my apartment, one of the few independent pharmacies left in the West Village, where chain stores dominate. Grove’s window displays are always of interest, but this one fascinated me at first glance, since it took me back to the apothecary shops of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. When I asked inside about the source of these relics from the past, I was told that they had belonged to a pharmacy at Bleecker Street and Sixth Avenue, now closed, that had gone back a century or more.

(Note: The word “apothecary” can designate either the shop or the medicine compounder working in the shop. To avoid confusion, I will use “apothecary shop” for the shop.)

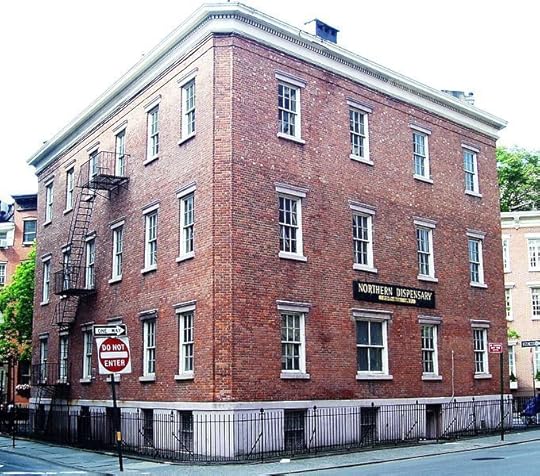

I soon identified the pharmacy in question as Avignone Chemists, formerly Avignone Pharmacy, which had been at Bleecker and Sixth Avenue since 1929. But the pharmacy traces its origins back to 1832, when its antecedent was founded as Stock Pharmacy at 59 MacDougal Street, at the corner of Houston, one of the oldest apothecary shops in the United States. In 1898 Stock Pharmacy was bought by Frank Avignone, an Italian immigrant, who changed the name to Avignone Pharmacy. When the building was demolished in 1929 for the widening of Houston Street, Frank and Horatio Avignone built a two-story brick structure at 281 Sixth Avenue/226 Bleecker Street and moved their pharmacy in. Frank Avignone’s son Carlo took over the business in 1956 and in 1974 sold it to the Grassi family, who were joined by Abe Lerner in 1991.

(A parenthesis to the above: Wikipedia calls Avignone the oldest apothecary shop in the U.S., but that honor is also claimed by another Village independent, C.O. Bigelow’s, at 414 Sixth Avenue, just above West 8th Street, which dates its founding to 1838. This assertion relies on affiliating Bigelow’s with its predecessor, the Village Apothecary Shop, which was indeed established at a nearby location in 1838 by Dr. Galen Hunter. Clarence Otis Bigelow, an employee of Dr. Hunter’s successor, bought the shop from his boss in 1880, renamed it after himself, then built the present building and moved into it in 1902. Which of these claims, if either, is valid, I leave to the viewer. I will only observe that an apothecary shop opened in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1759, a slightly earlier date than either date cited by these pharmacies.)

When Abe Lerner and his co-owners renovated the building in 2007, they changed the name to Avignone Chemists. The blond wood-frame exterior and double-door entrance, topped by a striped awning and an illuminated green cross indicating a pharmacy, gave it a welcoming warmth such as few chain pharmacies can boast. In the front window and on display inside were the very items of which I saw a selection in Grove Drug’s window: old apothecary jars, mortars and pestles, old clocks and radios and cameras, and several massive prescription books, all of which had been discovered in the basement during the 2007 renovation.

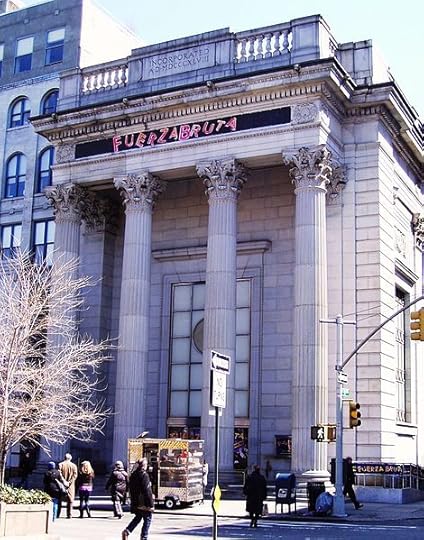

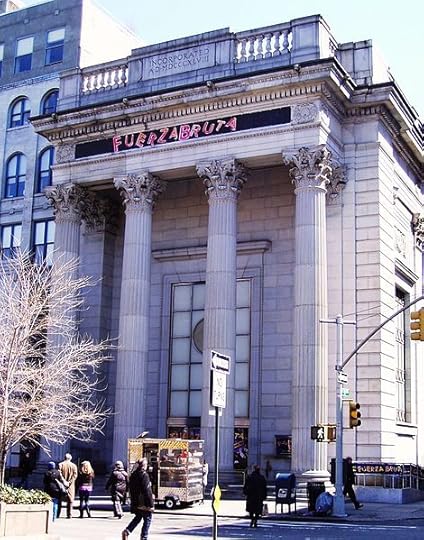

The end for Avignone came earlier this year, when the building was sold and the new owner, Force Capital Management, a New York-based hedge fund founded in 2002, tripled the pharmacy’s rent to $60,000, which Abe Lerner could not pay. Lerner, now 62, choked up at the thought of closing on April 30. “I’ve spent half my life here,” he told an interviewer. “I’ve known many of these people for thirty years; I’ve seen a lot of kids grow up. A lot of these people have become friends -- they’re not just customers, they’re friends.” The whole neighborhood mourns the pharmacy’s loss as well, for it had become a neighborhood hangout, a place to come and chat with friends. Yet another example of how soaring commercial rents, which are not controlled, can gut a neighborhood, driving out mom-and-pop stores that have been ˆn the neighborhood for years.

I walked by the old pharmacy at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Bleecker Street a couple of months after the closing, and there it was, a two-story building dwarfed by its neighbors, with “AVIGNONE CHEMISTS” above the striped awning, and on the awning “est. 1932,” which might be considered a bit of a stretch, since that date applies to a different pharmacy with a different name at a different address. The double door is padlocked, and in the window is a big sign, RETAIL AVAILABLE, indicating that no new tenant has as yet been found. And if one enters Winston Churchill Square, the small fenced park adjoining, high up on the building’s brick wall you can still see a faded sign probably dating from the 1950s:

AVIGNONE PHARMACYPRESCRIPTIONS

And what about Grove Drugs, whose display set me off on this investigation? It’s a small pharmacy whom an online Yelp reviewer describes as “a fine, friendly, old-fashioned neighborhood pharmacy.” True enough. Like Avignone Chemists, Grove relishes its status as an independent pharmacy competing with the chain stores: David against Goliath, the little guy against the multiple massive presence of CVS Pharmacy, Duane Reade, and Rite-Aid. Being small, it can offer only the basic basics, as compared with the Rite-Aid on Hudson Street, which has five times the floor space and offers a bewildering variety of products, including children’s toys, seasonal greeting cards, and junk-food snacks.

Not exactly a friendly neighborhood pharmacy.

Not exactly a friendly neighborhood pharmacy.Jim.henderson

Rite-Aid entices me with a so-called Wellness Card offering a 20% discount – not to be sniffed at -- on the first Wednesday of every month, but I can wander its many aisles without ever encountering an employee. If I go to Grove, at the counter in back there’s always someone to point me to whatever I need. Also, I like the plain-Jane simplicity of “Grove Drugs,” as opposed to “Village Apothecary,” another West Village independent, and yes, even “Avignone Chemists,” which to my mind hint of pretension. And there’s something charmingly quaint about Grove’s closing on Sunday and holidays (“Please anticipate your needs”), and at 7:30 p.m. on weekdays, while the chain stores are open 24/7. As for its seasonal window displays – an animated wintry panorama with a miniature toy factory, carolers, and skaters at Christmas, bunnies at Easter, and skulls and bats and huge spiders and their webs at Halloween – they are the most entertaining in the entire West Village.

And why does the pharmacy at 202 West 12thStreet bear the name “Grove Drugs”? Because for many years the owner, John Duffy, operated another West Village independent, Grove Pharmacy, at 261 Seventh Avenue, on the corner of Grove Street, until forced out by his landlord in 2006. And why did the artifacts of the Avignone Chemists come to Grove Drugs? Because John Duffy was part owner of Avignone as well. So Grove Drugs must be his last stand against greedy landlords and invasive chain stores. I wish him well.

But I’m not quite done with the fascinating relics in Grove’s window, for to fully grasp their significance you have to understand the role of the old-time apothecary, a profession dating back to antiquity and differing from that of today’s pharmacist. Pharmacies today are well stocked with over-the-counter products mass-produced by pharmaceutical companies; they come in standardized dosages formulated to meet the needs of the average user. But throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the apothecary, the predecessor of today’s pharmacist, created medications individually for each customer, who received a product that was, so to speak, tailor-made. In theory, the apothecary had some knowledge of chemistry, but at first there was little regulation.

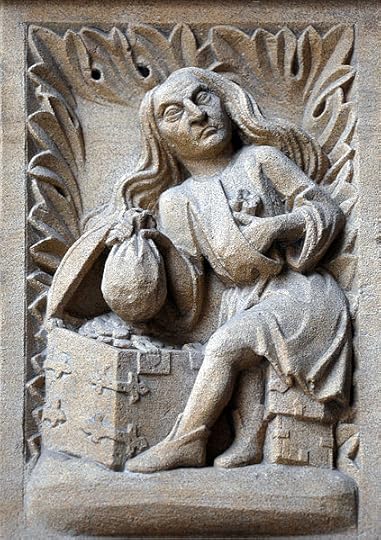

A 17th-century German apothecary.

A 17th-century German apothecary.Welcome Library

The objects on display in Grove’s window hearken back to this early period when the apothecary made compounds from ingredients like those in the bottles and jars displayed, grinding them to a powder with a mortar and pestle, weighing them with scales to get the right measure, or distilling them with the glass paraphernalia seen in the window to make a tincture, lotion, volatile oil, or perfume. The one thing typical of the old apothecary shops that the display can’t reproduce was the aroma, a strange mix of spices, perfumes, camphor, castor oil, and other soothing or astringent remedies. Mercifully absent as well is a jar with live leeches, since by the late nineteenth century the time-honored practice of bloodletting, which probably killed more patients than it benefited, had been discontinued.

The apothecary’s remedies were derived sometimes from folk medicine and sometimes from published compendiums. Chalk was used for heartburn, calamine for skin irritations, spearmint for stomachache, rose petals steeped in vinegar for headaches, and cinchona bark for fevers. Often serving as a physician, the apothecary applied garlic poultices to sores and wounds and rheumatic limbs. Laudanum, or opium tincture, was employed freely, with little regard to its addictiveness, to treat ulcers, bruises, and inflamed joints, and was taken internally to alleviate pain. Little wonder that well-bred ladies became addicted, like Eugene O’Neill’s mother, as memorably portrayed in his play A Long Day’s Journey into Night. But if some of these remedies seem fanciful or naïve or even dangerous, others are known to work even today, as for example witch hazel for hemorrhoids.

But medicines weren’t the only products of an apothecary shop. Rose petals, jasmine, and gardenias might be distilled to create perfumes, and lavender, honey, and beeswax were compounded to create face creams to enhance the milk-white complexion desired by ladies, in a time when the sun tan so prized today characterized a market woman or farmer’s wife, lower-caste females who had to work outdoors for a living. (The prime defense against the sun was, of course, the parasol, without which no lady ventured outdoors.) A fragrant pomade for the hair was made of soft beef fat, essence of violets, jasmine, and oil of bergamot, and cosmetic gloves rubbed on the inside with spermaceti, balsam of Peru, and oil of nutmeg and cassia were worn by ladies in bed at night, to soften and bleach the hands, and to prevent chapped hands and chilblains.

But the apothecary’s products were not without risks. Face powders might contain arsenic; belladonna, a known poison, was used to widen the pupils of the eyes; and bleaching agents included ammonia, quicksilver, spirits of turpentine, and tar. All of which suggests a less than comprehensive grasp of basic chemistry. And in the flavored syrups and sodas devised to mask the unpleasant medicinal taste of prescriptions, two common ingredients were cocaine and alcohol, which must have induced in the patients an unwonted buoyancy of spirits.

Marketed especially for children, no less.

Marketed especially for children, no less.Also available in an apothecary shop were cooking spices, candles, soap, salad oil, toothbrushes, combs, cigars, and tobacco, so that it in some ways approximated the general store of the time. And in the eighteenth century American apothecaries also made house calls, trained apprentices, performed surgery, and acted as male midwives.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, merits a mention of its own. The name means “beautiful lady” in Italian, for the juice of its berry was used by Italian women in the Renaissance to dilate the pupils of their eyes so as to appear more seductive. A sinister and risky beauty resulted, for this small shrub that grows in many parts of the world, including North America, produces leaves and berries that are extremely toxic, as indicated by its other common name, “deadly nightshade.” It has long been known as a medicine, poison, and cosmetic. Nineteenth-century medicine used it to alleviate pain, relax the muscles, and treat inflammation, and it is still in use today as a sedative to stop bronchial spasms, and also to treat Parkinson’s, rheumatism, and other ailments.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, merits a mention of its own. The name means “beautiful lady” in Italian, for the juice of its berry was used by Italian women in the Renaissance to dilate the pupils of their eyes so as to appear more seductive. A sinister and risky beauty resulted, for this small shrub that grows in many parts of the world, including North America, produces leaves and berries that are extremely toxic, as indicated by its other common name, “deadly nightshade.” It has long been known as a medicine, poison, and cosmetic. Nineteenth-century medicine used it to alleviate pain, relax the muscles, and treat inflammation, and it is still in use today as a sedative to stop bronchial spasms, and also to treat Parkinson’s, rheumatism, and other ailments.  A witches' sabbath, Goya version.

A witches' sabbath, Goya version. Satan often appeared as a goat. Belladonna figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to kill her husband. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

All in all, not a plant to mess with, although a staple in most apothecary shops of former times. If you think you’ve never gone near it, think again, for if you’ve ever had your eyes dilated, belladonna is in the eye drops. And I’ll admit that the name intrigues me: belladonna, the beautiful lady who poisons. Which brings us back to the Empress Livia; maybe she did do the old boy in.

Gradually, the professions of apothecary and pharmacist -- never quite distinct – became more organized, then regulated. In the nineteenth century patent medicines (which were not patented) became big business, thanks to advertising, but their mislabeling of ingredients and extravagant claims inspired a growing desire for regulation that finally resulted in the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This and subsequent legislation probably benefited apothecaries, since mass-produced patent medicines competed with their products.

An FDA exhibit of dangerous products that the 1906 act didn't cover, used to campaign for stricter legislation, which was enacted in 1938.

An FDA exhibit of dangerous products that the 1906 act didn't cover, used to campaign for stricter legislation, which was enacted in 1938.As late as the 1930s and 1940s, apothecaries still compounded some 60% of all U.S. medications. In the years following World War II, however, the growth of commercial drug manufacturers signaled the coming decline of the medicine-compounding apothecary, just as the use of the mortar and pestle diminished to the point of becoming a quaint and charming symbol of a bygone era. In 1951 new federal legislation introduced doctor-only legal status for most medicines, and from then on the modern pharmacist prevailed, dispensing pre-manufactured drugs.

By the 1980s large chain drugstores had come to dominate the pharmaceutical sales market, rendering the survival of the independent neighborhood pharmacy precarious. Yet some of them do survive, as we have seen, and when one closes, the whole neighborhood mourns. But in a final twist, the word “apothecary,” meaning a place of business rather than a medicine compounder, has become “hip” and “in,” appearing in names of businesses having nothing to do with medicines. It expresses a nostalgia for experience free from technology and characterized by creativity and a personal touch, a longing for Old World tradition and gentility. And as one observer has commented, “apothecary” is fun to say.

A note on poisonous plants: Though it grows in North America, I’ve never seen belladonna, nor is it listed in U.S. field guides. But other poisonous plants are common, and I’ve seen them in the field. Poison ivy is ubiquitous but too familiar to dwell on. Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) does indeed sting, as I know from experience, and cursed buttercup (Ranunculus sceleratus), which I’ve seen growing in shallow swamp water in Van Cortland Park, causes blisters if touched; yet neither is described as poisonous. Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), an umbrella-like plant with terminal clusters of tiny white flowers and finely divided fernlike leaves, grows in one shady spot in Van Cortland Park and lives up to its name, since its juices are highly toxic; in ancient Athens it was the means for putting Socrates to death.

Mick Talbot But the real surprise for me, in researching poisonous plants, was to learn that jimsonweed (Datura stramonium), which I’ve seen growing in dry soil in Pelham Bay Park in the summer, is both hallucinogenic and poisonous. I should have known, for it’s in the nightshade family, which includes belladonna. (And the potato and tomato, but that’s another matter.) An erect, foul-smelling plant with coarse-toothed leaves and big, trumpet-like flowers three to five inches long, it attracts attention because of its large, pale violet flowers, but there’s something about it that is brazen and coarse. The common name is a contraction of “Jamestown weed,” for it was first described in America in 1676 in Jamestown, Virginia. It has been used in folk medicine as an analgesic, and in sacred ceremonies among Native American tribes as a hallucinogen. But both the medicinal and hallucinogenic properties are fatally toxic if used in slightly higher amounts than the medicinal dosage, and many a would-be visionary and adventurous thrill-seeker has ended up in the hospital, if not in a coffin.

Mick Talbot But the real surprise for me, in researching poisonous plants, was to learn that jimsonweed (Datura stramonium), which I’ve seen growing in dry soil in Pelham Bay Park in the summer, is both hallucinogenic and poisonous. I should have known, for it’s in the nightshade family, which includes belladonna. (And the potato and tomato, but that’s another matter.) An erect, foul-smelling plant with coarse-toothed leaves and big, trumpet-like flowers three to five inches long, it attracts attention because of its large, pale violet flowers, but there’s something about it that is brazen and coarse. The common name is a contraction of “Jamestown weed,” for it was first described in America in 1676 in Jamestown, Virginia. It has been used in folk medicine as an analgesic, and in sacred ceremonies among Native American tribes as a hallucinogen. But both the medicinal and hallucinogenic properties are fatally toxic if used in slightly higher amounts than the medicinal dosage, and many a would-be visionary and adventurous thrill-seeker has ended up in the hospital, if not in a coffin.  H. Zell

H. ZellSo here am I, reveling in the exotic charms of belladonna, when right close to home, viewed every summer in a city park, is a native species every bit as dangerous, and fascinating, as the beautiful eye-dilating lady of the Renaissance. But no, I’m not even remotely tempted to taste of the hallucinatory joys of jimsonweed, whose other names include devil’s snare, devil’s trumpet, and hell’s bells. But it does make a hike in Pelham Bay Park more interesting.

Coming soon: West Village Wonders and Horrors. Including a civilized parlor and the most talked-about monstrosity in the Village.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on July 05, 2015 05:04

June 28, 2015

186. Catastrophes: 1832 and 1888

June 15, 1832: a steamboat from Albany brings word that cholera has leaped the Atlantic to bring devastation to Quebec and Montreal. Cholera: the very word spreads fear. The mayor immediately proclaims a quarantine; no ship is to come closer to the city than 300 yards, and no land-based vehicle within a mile and a half. Then, on the night of June 26, an Irish immigrant named Fitzgerald becomes violently ill with cramps; he recovers, but two of his children likewise get cramps and die. The city fathers pressure the Board of Health to declare them victims of diarrhea, a common summer complaint, but many physicians know better, and word spreads that, in spite of the quarantine and the prayers of the pious, cholera has come to New York. Other residents begin experiencing a sudden attack of diarrhea and vomiting, followed by abdominal cramps and then acute shock and the collapse of the circulating system. Panic ensues.

New York City was used to yellow fever epidemics in the summer months, but not this: it was sudden, it was messy, it was fatal. But not all New York was affected: the white middle-class neighborhoods suffered less, while the slums were stricken. Especially the notorious Five Points slum just east of City Hall, where Irish immigrants and African Americans were packed together in filthy tenements. Soon horse-drawn ambulances were rattling through the streets, hospitals were jammed, mortalities soared.

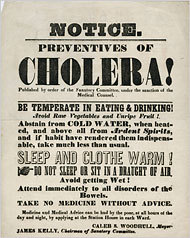

The city’s Sanitary Committee, under the sanction of medical counsel, published a pamphlet that was widely circulated.

Most of which was irrelevant. The science of the day had no accurate knowledge of the disease, didn't connect cholera with contaminated water. There was no modern water supply system, no adequate sewage disposal; even the finest homes lacked running water, got their water from wells or cisterns, or from carts that peddled “tea water” (water to use when making tea) from a spring deemed safe. Doctors didn’t think the disease was contagious, attributed it to “miasmas,” meaning noxious vapors from decaying organic matter. Recommended remedies included laudanum and calomel, and camphor as an anesthetic; high doses often did more harm than good. Other treatments included poultices combining mustard, cayenne pepper, and hot vinegar, and opium suppositories and tobacco enemas.

By early July the white middle class was fleeing the city. Roads in all directions were jammed with crowded stages, livery coaches, private vehicles, mounted fugitives, and trudging pedestrians with packs on their backs. Normal steamboat service was almost nonexistent, for other communities refused to let steamboats with passengers from New York approach the landings; travelers had to disembark far from their destination and trek long distances through fields with their luggage before even finding a road. Farms and country houses within thirty miles of the city were filled with lodgers.

Back in the city, business was suspended and Broadway was deserted. Even churches closed down, though doctors, undertakers, and coffin makers had plenty to do. Carts loaded with coffins rumbled through the streets to the Dead House, unburied bodies lay rotting in the gutters, and putrefying corpses were taken to the potters’ field and dumped in shallow graves to provide a feast to rats.

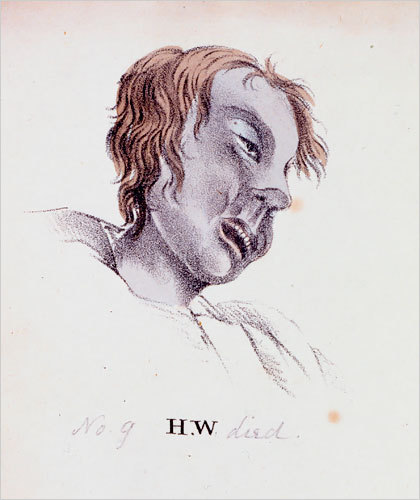

Many poor people blocked efforts to remove their sick to the hospitals, regarding them as charnel houses, and assaulted doctors or city officials who insisted. And of those who were admitted, many died within a day, which only stoked the public's fear. When private hospitals began turning away patients, the city established emergency public hospitals in schools and other buildings. One on Rivington Street was overwhelmed, and sketches made of patients there are haunting, their eyes wild, their faces contorted in the throes of death. The sketches appeared in a pamphlet published a year later by Horatio Bartley, an apothecary, with notes identifying the patients by initials only and tersely describing their suffering and the futile treatments attempted:

H.W. aged 56. Born in Barbados. Admitted 6th August, 6 o’clock P.M. Was attacked with purging and cramps in the night … prostration of strength … hands corrugated…. Ordered dry frictions, and afterward rubbed with a liniment…. Was put under medical treatment, until 6 P.M. and died after an illness of 4 hours.

Surprisingly, a few were deemed cured and sent to a convalescent hospital. But the ravaged features of the sketches are haunting, for they dramatize the victims and their suffering as printed words cannot; you are seeing the face of death.

Removing themselves from the reach of cholera didn't keep well-scrubbed middle-class citizens from evincing strong opinions about who got the disease, and why. John Pintard, a prominent citizen and founder of the New York Historical Society, remained in the city and wrote one of his daughters that the epidemic “is almost exclusively confined to the lower classes of intemperate dissolute & filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations.” And in another letter he declared, “Those sickened must be cured or die off, & being chiefly of the very scum of the city, the quicker [their] dispatch the sooner the malady will cease.” This opinion was common among the better off. Never was there a more blatant case of blame the victims. Contrasting with such attitudes was the devotion of the Catholic nuns and priests who stayed in the city to tend the victims, many of whom were Irish immigrants; the Sisters of Charity performed valiantly, and some of them died as a result. The Protestant majority took notice and grudgingly – for a while -- acknowledged their heroism.

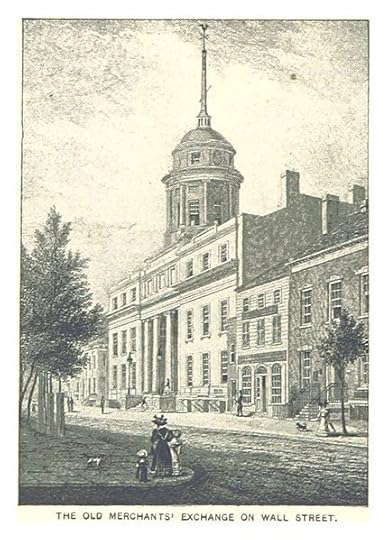

By August the number of victims was declining. On August 22 the Board of Health announced that the city could be visited safely. The streets began to come alive, stores reopened, the rattle of drays and wagons was heard again, and private carriages were seen. Normal service by steamboats and stages resumed, and the city was linked again to the outside world. But out of 250,000 residents, 3,515 had died, the equivalent, for today’s population of eight million, of over 100,000 victims. “The hand of God,” said some. Fearing a recurrence, middle-class residents continued to move north to Greenwich Village, where numerous Greek Revival houses dating from 1832-1836 reflect this exodus.

Even though the link between cholera and contaminated water was not yet understood, the epidemic determined the city to create a modern water-supply system. This was completed in 1842, prompting a great citywide celebration, and from then on the gush of running water and the splatter of showers brought joy to the houses of the affluent, who could afford to pay the water tax. But the tenements and shanties of the poor knew no such amenities, and their residents still depended on water from wells often contaminated with human and animal waste.

This is not the end of the story, for cholera returned to the city when a packet from France arrived on December 1, 1848; seven passengers had died on board, and the rest were quarantined on Staten Island. Within a month 60 had experienced symptoms of the disease and 30 died. Fearing to become victims themselves, the quarantined survivors escaped and entered the city, where more cases were soon reported. Dogs and pigs roaming the streets to scavenge garbage helped spread the disease, and the city soon underwent a dreary repetition of the calamity of 1832, with two to three hundred dying daily and an even higher toll: over 5,000 in all, some 40% of them Irish immigrants. The epidemic peaked in early August and then quickly subsided, business resumed, and middle-class fugitives returned.

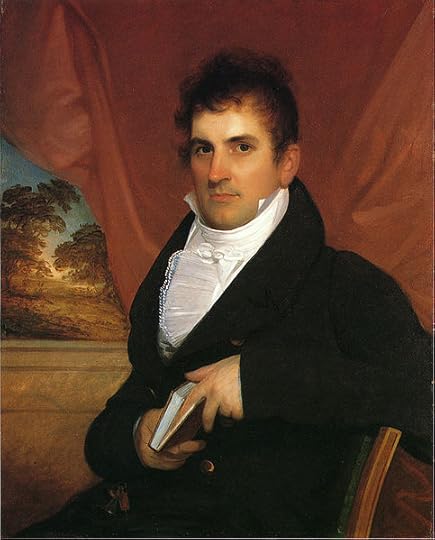

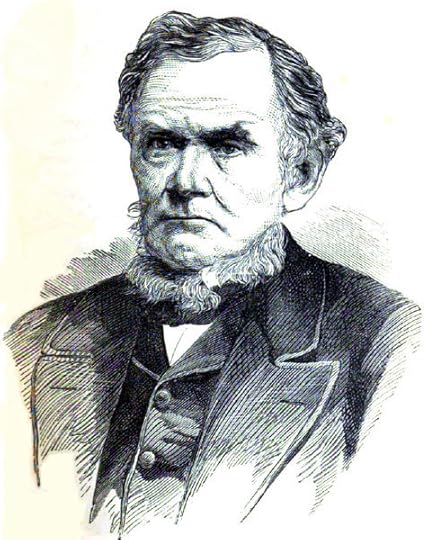

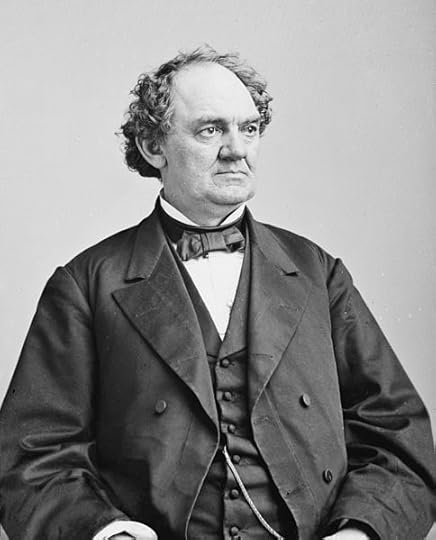

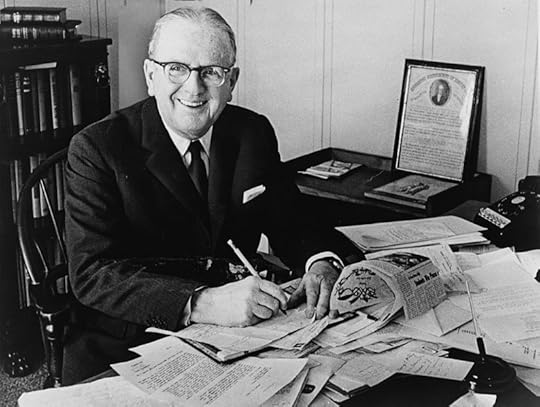

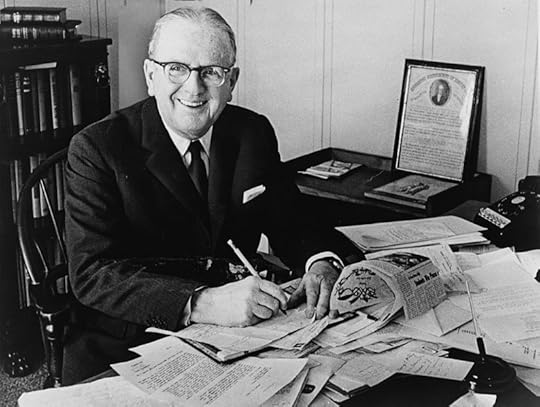

Philip Hone Not all the victims were Irish immigrants. The diary of Philip Hone, a successful retired auctioneer and former mayor, tells how on September 1, while working quietly in his office, he was seized with a violent diarrhea and ague. His son rushed him home by carriage and put him to bed with a severe chill. Nausea and vomiting followed, and his hands and face turned blue. A doctor came, looked, and diagnosed cholera. The family feared the worst, but “assiduous” treatment saved him and he recovered. Being treated at home, rather than in a hospital crammed with other victims, probably helped. But his contraction of the disease was proof enough that it was not confined to the Irish and German immigrants mentioned earlier in his diary as “filthy and intemperate.”

Philip Hone Not all the victims were Irish immigrants. The diary of Philip Hone, a successful retired auctioneer and former mayor, tells how on September 1, while working quietly in his office, he was seized with a violent diarrhea and ague. His son rushed him home by carriage and put him to bed with a severe chill. Nausea and vomiting followed, and his hands and face turned blue. A doctor came, looked, and diagnosed cholera. The family feared the worst, but “assiduous” treatment saved him and he recovered. Being treated at home, rather than in a hospital crammed with other victims, probably helped. But his contraction of the disease was proof enough that it was not confined to the Irish and German immigrants mentioned earlier in his diary as “filthy and intemperate.”By now there was increased awareness that cholera was more a social problem than a moral one, and an 1865 ward-by-ward survey of living conditions in the city led to the creation, in 1866, of the Manhattan Board of Health, which issued orders to clean up accumulated animal manure, rotting food, and dead animal carcasses at various sites around the city. While some business owners failed to comply, the city was the cleanest it had ever been when cholera struck for a third time that summer and took its usual toll of the poorer neighborhoods downtown. Still, the final toll of 1,137 victims, in a city of 1.2 million, was much less than in the outbreaks of 1832 and 1849. But middle-class prejudice dies hard. Pronounced the lawyer George Templeton Strong in his diary entry of August 6, “The epidemic is God’s judgment on the poor for neglecting His sanitary laws.” Not that he had to worry: his family were safe off on vacation in Vermont.

Science in time solved the mystery of cholera. In 1854 a London physician, Dr. John Snow, established the connection between the disease and contaminated water, when he discovered that most of the cholera victims of that year drew water from the same public well, and that a baby’s infected diapers had been dumped in a cesspool nearby. As for the discovery of the bacillus that caused cholera, it was at first attributed to the German physician Robert Koch in 1883. But we now know that the Italian physician Filippo Pacini had discovered and reported it in 1854, though his work was long ignored by the scientific community; finally, in 1965, the scientific name of the organism was officially changed to Vibrio cholera Pacini 1854. Better late than never.

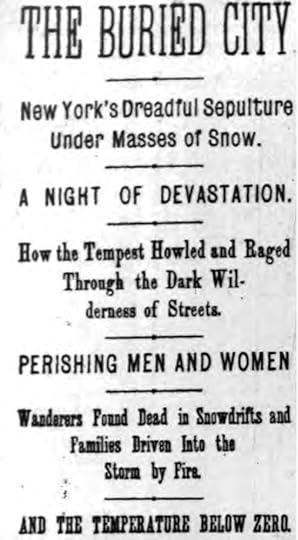

And now for a change of season, and catastrophe. New York has experienced severe snowstorms in recent years, but when people complain, history buffs smile knowingly and say, “This is nothing compared to ’88.” Meaning not 1988, of course, but 1888. And thereby hangs a tale.

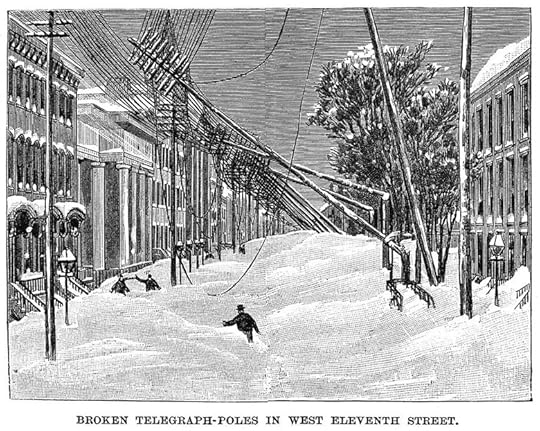

It seemed to come out of nowhere. On March 10, 1888, the temperature hovered in the mid-50s, and the weather forecast was for cooler weather but generally fair; New Yorkers thought spring was imminent. But the next day Arctic air from Canada collided with warm air from the south, and temperatures plunged. In no time rain turned to snow, and by midnight winds were blowing at 85 miles per hour. Overnight the snow -- tons of it -- kept falling, blanketing the whole Northeast and Canada, until by the morning of Monday, March 12, the city was buried under forty inches of snow, with drifts reaching the second story of some buildings.

Waking to this spectacle, New Yorkers were astonished: blizzards, they thought, were something that happened on the Great Plains and in the Far West, but now one was happening here; a “Dakota blizzard,” they called it. Householders who tried to leave the house often found the front door and even the ground-floor windows blocked by snow, had to fetch a coal shovel from the basement and exit by a side door that didn’t face the storm head on, so that, with stiffening fingers and wind-stung faces, they could dig a path to the street. But of those who then departed, many soon turned back.

Waking to this spectacle, New Yorkers were astonished: blizzards, they thought, were something that happened on the Great Plains and in the Far West, but now one was happening here; a “Dakota blizzard,” they called it. Householders who tried to leave the house often found the front door and even the ground-floor windows blocked by snow, had to fetch a coal shovel from the basement and exit by a side door that didn’t face the storm head on, so that, with stiffening fingers and wind-stung faces, they could dig a path to the street. But of those who then departed, many soon turned back.The municipal government was shut down, the stock exchange closed. A few trucks were seen on the streets, but they were soon stalled in drifts. Some valiant citizens managed to trudge out to take the elevated trains to work, only to find them soon blocked with snowdrifts; some 15,000 passengers were stranded on snowbound trains, prompting some enterprising fellow citizens to appear with ladders and offer to rescue them … for a fee.

By evening the streets were littered with blown-down signs, and abandoned horsecars lying on their sides, their horses having been unhitched and led away to shelter. Jammed with stranded commuters, hotels installed cots in their lobbies. That night well-dressed gentlemen who couldn’t get a hotel room were glad to apply at a station house, usually the refuge of tramps and street kids, and settle for an ill-smelling cot. Telegraph and telephone lines, water mains, and gas lines, being located above ground, were frozen, and violent winds prevented repair crews from reaching them. The electric streetlights were out, and lighting the gas lamps was impossible, so at night the city was plunged in darkness. Hospitals were overwhelmed with cases of frozen hands and feet, fractured limbs, broken skulls. Firemen, their teams trapped in heavy drifts, watched helplessly as fires raged in the distance. Transportation was at a standstill; cut off from the rest of the world, the city was paralyzed.

Walking the streets was perilous. The roaring, whistling wind stung your face, snow blinded you, exhaustion threatened. Policemen rubbed the numbed ears of pedestrians with snow to keep their ears from freezing, but at times encountered white, frozen hands protruding from giant wind-whipped drifts. A rigid corpse was discovered in Central Park, and another, that of a prominent merchant, on Seventh Avenue. Two Herald reporters wading through drifts on Broadway found an unconscious policeman half buried in snow at 23rdStreet and half-carried, half-dragged him to the Herald office, where he revived. Braving the wind and cold, Senator Roscoe Conkling, one of the most powerful Republicans of the time, tried to walk the three miles from his Wall Street law office to his home on 25thStreet near Madison Square, made it as far as Union Square, collapsed; contracting pneumonia, he died several weeks later.

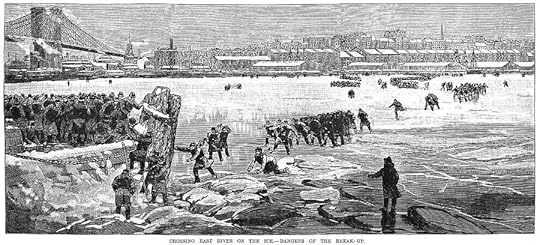

Brooklyn, then a separate city, was also isolated. Because of the howling wind, to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge was dangerous; the police advised against it. But a great ice floe was pushed into the East River, which was usually warmer than the Hudson and not frozen over; jammed there, the ice provided a bridge that let people walk from Brooklyn to New York. But not without risk, for hours later the tide changed and the ice began breaking up. Some of those attempting the crossing suddenly found themselves drifting downriver on cakes of ice and shouted and waved their hands wildly in a plea for help. All the vessels on the river gave the alarm by blowing their whistles, and crowds ran frantically along both riverfronts shouting and screaming. Fortunately, several steam tugs quickly pulled out into the river and rescued the castaways.

By dawn of March 13 the snow stopped falling, but the temperature was still below zero and the wind roared on for another two days, whipping the snow into weird, fantastic shapes. Huge mounds of snow blocked the streets, and between them were narrow paths where people crept along, sometimes seeing nothing but mountains of white and the sky above for half a block. People who went out on show shoes walked over the tops of trees. Their tracks covered, horsecars couldn’t operate, but sleighs with jingling bells appeared, and people hired them for $30 or $50 a day. Caps and thick woolen gloves were hawked on the streets, and newspapers sold for exorbitant prices that people gladly paid, partly out of sympathy for the half-frozen newsboys.

The price of coal doubled, and with their wives housebound and delivery of milk, bread, and other items suspended, many husbands embraced the unwonted task of lugging homeward whatever groceries they could buy in stores whose supplies were fast dwindling. A grocer on 8th Street who raised the price of a pail of coal from ten cents to a dollar found the wheels of his wagon stolen and replaced with shabby ones and a message in chalk: “Fair exchange is no robbery.” State legislators trapped in the city were consumed by worry at the thought of legislation that might be passed in Albany in their absence. Sounds of revelry issued from saloons, where men were downing whiskey to ward off the effects of the cold. Some of the imbibers then staggered out into the wilderness of snow, often as not collapsing in a drift and ending up with injuries in a hospital. And on the city’s outskirts exhausted survivors staggered in with tales of whole trainloads of passengers imprisoned in the snow without food or means of escape, following which rescue parties in sleighs were dispatched to rescue them.

When the wind at last subsided, travel on the streets was feasible, and the city tried to return to normal, but normal was still far off. Coal and foodstuffs were in short supply, and rail transportation remained suspended. For days there was no garbage collection, so people dumped their garbage in the streets. Huge piles of snow lined every sidewalk. Snow plows drawn by a dozen horses began clearing the streets, and gangs of workers shoveled snow onto carts that hauled it to the docks and dumped it in the river. The main thoroughfares were the first to be cleared, but in other neighborhoods the lingering snow turned black and stubbornly persisted until melted by the warm sun of spring; the last pile of it is said to have disappeared only in July. The bodies of more victims were found; in all, some two hundred New Yorkers had died in the storm. But something positive resulted: a renewed determination to move all elevated trains and power lines underground, so they would be less vulnerable.

Everyone who experienced the Great White Hurricane treasured the memory. Forty years later a club of aging veterans was formed that met annually on March 12 to share their experiences of the worst snowstorm to ever hit the city. Younger citizens scoffed, insisting that the old codgers’ tales were exaggerated and grew more so every year, but the old codgers knew better; the storm they had survived was unique.

Brooklyn redeemed: The Metropolitan section of the New York Times of Sunday, June 21, has two stories of redemption in Brooklyn. Congrats, Brooklyn.

First story: Ana Martinez de Luco, age 60, a Basque-born Catholic nun in an apron and sandals, runs a redemption center in East Williamsburg that she helped found in 2007. No, she's not redeeming people, for her redemption center, Sure We Can, is a depot for recyclables scavenged from trash by volunteers called canners who get a nickel per can or bottle. Crates, cartons, and cardboard boxes are piled everywhere, a stench of stale beer pervades the place, and chatter in English, Spanish, and Chinese is heard, as the canners bring their overloaded shopping carts to the stalls where staffers sort the items out. "It redeems people too," the "street nun" says of the center, for some of the canners have addiction or emotional problems or have done time in prison, and working there is therapeutic. Some of the Latino staffers have become her "sons" and bring her flowers on Mother's Day. And beyond the sheds that shelter the scavenged recyclables are gardens that, enriched with compost gathered from local businesses, yield lettuce, squash, beans, and tomatoes. Yes, a redemption center in every sense of the phrase.

Second story: Followers of this blog know that the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn has a special place in my heart as my favorite Superfund cleanup site, its waters long since hopelessly polluted. But perhaps not hopelessly after all. Things have now improved there to the point where canalside dining is feasible. Yes, by the waters of that once polluted Venice there are now wooden tables and benches where diners gobble turkey, pork, or beef and guzzle beer at Pig Beach, which is described as a "no-frills pop-out outdoor barbecue restaurant." And the diners seem happy, oblivious of a recent review on the website Gothamist that called Pig Beach "the Worst New BBQ Place in NYC." Not my kind of food, I grant you, but anything that helps redeem the Gowanus Canal deserves to be celebrated.

Coming soon: Apothecaries, and the Charms of Belladonna. A post about the old-time apothecary shops, inspired by the current window display at Grove Drugs, 302 West 12th Street (entrance on Eighth Avenue), but a couple of blocks from my apartment, with a host of jars, bottles, scales, a big mortar and pestle, and a huge faded book with prescriptions dated 1917. If you live in this part of town, by all means go look at the display, which will take you back a century to the apothecary shops of bygone days. As for belladonna, also known as deadly nightshade, you may wonder why a known poison figures among the items displayed. All will be explained. And don't think you've never been exposed to it; you almost certainly have, and many times, as will also be explained.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on June 28, 2015 04:27

June 21, 2015

185. Addictions

This post is about addictions: not drugs or alcohol or nicotine, but the stuff we get obsessed about, the stuff we think we can’t do without. Let’s begin with a quote from a prose poem of Baudelaire:

Il faut vous enivrer sans trêve. Mais de quoi? De vin, de poésie, ou de vertu à votre guise. Mais enivrez-vous.

You’ve got to be constantly drunk. But on what? On wine, on poetry, or on virtue, as you wish. But get drunk.

Avarice, cathedral of Metz. So what do we get drunk on? Here in New York, Wall Street is drunk on greed. In post #150, “Wall Street, Greed, and Addiction” (October 26, 2014), I discussed exactly this, citing the account of a former Wall Streeter who at age 25 had a salary of $1.75 million a year, but came to realize that he wasn’t doing anything useful or necessary to society, that he was addicted to money -- an addiction that he finally, with great effort, shook off.

Avarice, cathedral of Metz. So what do we get drunk on? Here in New York, Wall Street is drunk on greed. In post #150, “Wall Street, Greed, and Addiction” (October 26, 2014), I discussed exactly this, citing the account of a former Wall Streeter who at age 25 had a salary of $1.75 million a year, but came to realize that he wasn’t doing anything useful or necessary to society, that he was addicted to money -- an addiction that he finally, with great effort, shook off.And how are things on Wall Street today? For the last five years the beginning Wall Street salary for recent college graduates was a mere $70,000, but now times are so good that it has been raised to $85,000. So an article in the New York Times of May 14 states, while reporting on a new study giving the views of Wall Street professionals themselves on their industry. About a third of those interviewed said they had knowledge of wrongdoing in the workplace, and nearly one in five concedes that, to be successful today, a Wall Streeter must sometimes engage in unethical or illegal activity. Compensation structures or bonus plans encourage employees to compromise ethics or violate the law, and employees fear retaliation if they should ever report wrongdoing. All of which suggests that, in spite of penalties worth billions that Wall Street firms have paid to settle charges of misconduct, their addiction to greed still rages.

This reminds me of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s beloved classic The Little Prince, in which a little prince from another planet tells of his adventures exploring the cosmos and learning about grown-ups. On one asteroid he encounters a businessman who is totally involved in counting “those little golden things that make lazy people daydream,” which the little prince finally identifies as stars. The businessman claims to own the stars, but all he does is count them and put the numbers in a bank. When his visitor observes that such ownership serves no useful purpose, the businessman is left speechless, and the little prince departs, observing that grown-ups are truly “extraordinary.” I humbly suggest that the behavior of many denizens of Wall Street is likewise truly extraordinary.

But preoccupation with money may involve something other than greed. In the 1860s and early 1870s Daniel Drew, a drover turned financier and steamboat operator, reveled in perturbing Wall Street. Dressed drably, with a pinched face and a fringe of whiskers, he struck others as a rube from the provinces or a country parson, and was referred to as Ursa Major, the Old Bear, and the Deacon. As the most inside insider and its lender of last resort, he manipulated the stock of the Erie Railway, clipped Commodore Vanderbilt for several millions (no easy thing to do), and attempted a corner of greenbacks, on each occasion convulsing the stock market and sometimes disrupting international markets as well. Tight-lipped, his gray eyes agleam with cunning, he loved being importuned by journalists on Wall Street, but gave them mere scraps of information at most – just enough to tantalize them and make them beg for more -- before entering his broker’s office, where he escaped to a snug, small room in back and shut the door in their face. And from inside that snug little room, where in cold weather he sat with his feet propped up on a mantle in front of a blazing fire, could be heard his hen-cackle laugh, which earned him yet another nickname: the Merry Old Gentleman of Wall Street. And well might he laugh. A half-literate farm boy from Putnam County who couldn’t even spell “door” (he spelled it “doare”), he'd showed them yet again that he could outsmart the shrewdest of the Wall Street crowd, that he was still a big bug on the Street.

But preoccupation with money may involve something other than greed. In the 1860s and early 1870s Daniel Drew, a drover turned financier and steamboat operator, reveled in perturbing Wall Street. Dressed drably, with a pinched face and a fringe of whiskers, he struck others as a rube from the provinces or a country parson, and was referred to as Ursa Major, the Old Bear, and the Deacon. As the most inside insider and its lender of last resort, he manipulated the stock of the Erie Railway, clipped Commodore Vanderbilt for several millions (no easy thing to do), and attempted a corner of greenbacks, on each occasion convulsing the stock market and sometimes disrupting international markets as well. Tight-lipped, his gray eyes agleam with cunning, he loved being importuned by journalists on Wall Street, but gave them mere scraps of information at most – just enough to tantalize them and make them beg for more -- before entering his broker’s office, where he escaped to a snug, small room in back and shut the door in their face. And from inside that snug little room, where in cold weather he sat with his feet propped up on a mantle in front of a blazing fire, could be heard his hen-cackle laugh, which earned him yet another nickname: the Merry Old Gentleman of Wall Street. And well might he laugh. A half-literate farm boy from Putnam County who couldn’t even spell “door” (he spelled it “doare”), he'd showed them yet again that he could outsmart the shrewdest of the Wall Street crowd, that he was still a big bug on the Street.Was Dan Drew addicted to greed? Many thought so at the time but were mistaken. When a young Methodist minister with whom he had a close friendship urged him to retire from business with his millions and do God’s work, he replied, “People don’t understand me. They think I love money. I tell you, Brother Parker, it ain’t so. I must have excitement or I should die. And when I get among these money kings, I go in because I don’t want them fellows to feel that they can have everything their own way. And when I go in, I go in to win, for I love the fight!” There, expressed candidly for perhaps the only time in his life, is the secret of what made Dan Drew, a good church-going Methodist, tick. He had to have risk and adventure, the sheer fun of secret combinations, of greenhorns and old hands alike flocking to him with offers, schemes, and tips, the thrill of sending messengers racing to the Stock Exchange with orders to buy or sell millions, the Street bleeding and the press agog because once again the Old Bear had “taken a slice out ’em.” Was this addiction? Yes. Dan Drew was addicted to excitement.

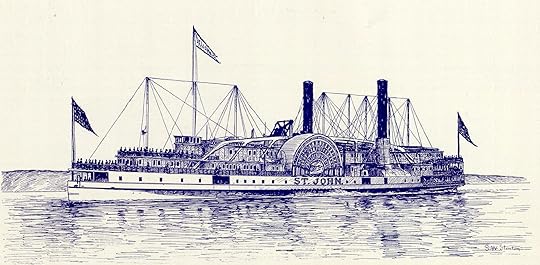

While Dan Drew was cavorting on Wall Street, his colleague Alanson P. St. John, a senior captain, superintendent, and treasurer of Drew’s People’s Line, was looking after Drew’s steamboats. Captain St. John had been a steamboat skipper on the Hudson River for over forty years, most of the time with the People’s Line. The rhythms of his life were married to the rhythms of the river, and to the palace steamboats, the finest in the world, that plied between New York and Albany. Every spring, when the packed ice of the Hudson began to squeak and crack and groan, and geese honked northward, and the first boats nudged their way upriver to Peekskill, then Poughkeepsie, and finally all the way to Albany, his heart beat fast, glad to shake off the long inactivity of winter. And when the great mass of ice broke loose and surged down the river, slammed and sloshed its way past Manhattan into the Inner Harbor and the Outer Harbor all the way out to Sandy Hook, and spewed forth into the ocean its captive splintered small craft, broken pier ends and bridges, and the thawed bodies of the drowned, then at last, with the river open to navigation, Captain St. John was truly and completely alive.

All spring and summer and autumn he ran the spume-treading People’s Line boats to Albany, skippering one and then another as they took merchants and politicians and westward bound travelers to Albany, fashionables to Saratoga, and aesthetes and artists to the Adirondacks. He knew and loved the sight of steamboat funnels belching pillars of smoke by day and showers of sparks by night, the sound of the splashing sidewheels, and in summer the aroma of fresh peaches and plums and grapes rising from the freight deck to intoxicate him. He knew the boats, their pistons plunging and their furnaces blazing as they sped silently and smoothly upriver, and he knew the passengers, who marveled at the paneling of rosewood and ebony, the grand saloons with glittering chandeliers, the marble tables and satin damask chairs. And if he especially prized the St. John, a $400,000 wonder of marine construction named for himself and hailed by the press, he could hardly be blamed; it was recognition of his lifelong devotion to the boats and the river. And if, late each autumn, geese honked southward, snow fell, and ice began to sheathe the Hudson, signaling the end of the season, he knew it was time to tie up the boats to the docks, repair and repaint them, and plan for the season to come.

So it went for years, but finally time caught up with him. In 1875, at age 77 and suffering from ill health, he was forcibly retired by the board of the People’s Line, following which he was at a loss, listless, depressed. Then, after a long winter, spring came. The Dean Richmond and the Drew had been overhauled, their brass polished, and new carpets and furniture installed, and were ready for the run to Albany, and the St. John would soon follow. With the river at last free for navigation, trucks were flocking to the docks to unload freight destined for all the river towns as far up as Albany and Troy. It was a new season with the whole river coming to life again, but he was not a part of it.

On the afternoon of April 23, 1875, the retired skipper came from his home in New Jersey to look over his favorite boat, the St. John, still undergoing repairs at the foot of West 19th Street, North River. Chatting with the mate on the deck, he seemed in good spirits and the best of health, following which he entered the steward’s room alone. Five minutes later a shot rang out. Rushing inside the cabin, the workmen found the captain sprawled dead in an easy chair, a smoking revolver in one hand, his features as composed as in sleep. Suicide, the coroner concluded, “while laboring under temporary aberration of mind.” Some attributed his depression to ill health, but his friends knew better: he couldn’t live away from the river. His addiction was benign, benefiting himself and many others for years, but in the end it killed him.

Yes, an addiction can be benign.

Captain St. John was addicted to steamboating and the river, but his addiction lacked the compulsive behavior of the true workaholic, which leads to neglect of family and friends and often undermines the subject’s health. A prime candidate for the label “workaholic” is Fiorello La Guardia, mayor of New York from 1934 to 1945, whom I have already discussed in post #102, “The Dynamo Mayor: La Guardia” (December 1, 2013). A workaholic? Consider:

· His feverish dictation of letters to three stenographers simultaneously: “Nuts! …Regrets! … Thanks!” while tossing letters at his secretary: “Say yes! … Say no! … Throw it away! … Tell him to go to hell!”· His whirlwind visits by car to verify the progress at a housing construction site, or to supervise snow removal or traffic flow, or query a patrolman or garbage collector, sometimes visiting all five boroughs in a single day.· His readiness, when angry, to knock a city employee’s hat off or dash a cigarette from a worker’s lips.· His delight in personally taking a sledge hammer to mobster Frank Costello’s confiscated slot machines and dumping the smashed machines from a police boat into Long Island Sound.· His rushing to the scene of a tenement roof’s collapse, a train wreck, or a fire to scream advice to police and firemen, even dashing into a burning building to inspect the refrigerator system to see if the building code had been violated.

Neil Estern's statue of La Guardia at La Guardia Place in Greenwich

Neil Estern's statue of La Guardia at La Guardia Place in GreenwichVillage. Better than any photo I know, it captures his intensity. Just an energetic little man who loved his job, you might say. Yes, he was all that, but anyone who saw his short, pudgy form in action, waving his arms wildly and raising his high-pitched, squeaky voice to a scream in order to make a point, sensed in his explosive personality a force that went beyond commitment to a job. He couldn’t not do these things, he was driven. Yes, I insist, a workaholic, but by general acclaim the best mayor – and certainly the most honest – that the city has ever had.

As La Guardia’s story demonstrates, zealous reformers risk becoming workaholics. Let’s look now at Henry Bergh (1813-1888), another reform-obsessed New Yorker but one whose name, unlike La Guardia’s, doesn’t resonate today. Tall, erect, and slender, with a droopy mustache considered stylish at the time, he had the appearance, in his frock coat and well-brushed topper, of a dapper gentleman of leisure who had no need to smirch his hands with toil. But if, on his treks through the city, he saw a cartman beating his horse, Bergh would approach the cartman and explain civilly that what he was doing was against the law. Then, if the offender evinced disbelief, Bergh would produce a copy of the law from his pocket and read it to him. So far, Bergh the gentleman. But if, as often happened, the cartman told him to go to hell and continued beating the animal, Bergh the gentleman was instantly transformed into Bergh the warrior, who would grab the offender by the collar and yank him down from his cart. And if a scuffle ensued, Bergh would summon the policeman he had posted nearby and have the man arrested.

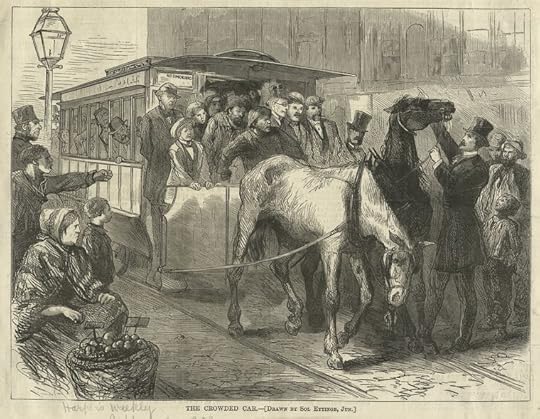

As La Guardia’s story demonstrates, zealous reformers risk becoming workaholics. Let’s look now at Henry Bergh (1813-1888), another reform-obsessed New Yorker but one whose name, unlike La Guardia’s, doesn’t resonate today. Tall, erect, and slender, with a droopy mustache considered stylish at the time, he had the appearance, in his frock coat and well-brushed topper, of a dapper gentleman of leisure who had no need to smirch his hands with toil. But if, on his treks through the city, he saw a cartman beating his horse, Bergh would approach the cartman and explain civilly that what he was doing was against the law. Then, if the offender evinced disbelief, Bergh would produce a copy of the law from his pocket and read it to him. So far, Bergh the gentleman. But if, as often happened, the cartman told him to go to hell and continued beating the animal, Bergh the gentleman was instantly transformed into Bergh the warrior, who would grab the offender by the collar and yank him down from his cart. And if a scuffle ensued, Bergh would summon the policeman he had posted nearby and have the man arrested. Henry Bergh stopping a crowded horsecar to see if the horses drawing it are well treated.

Henry Bergh stopping a crowded horsecar to see if the horses drawing it are well treated.Such was Henry Bergh’s daily routine in the city. He also targeted butchers who stacked live animals like cordwood on market-bound carts, organizers and patrons of dogfights and cockfights, trolley companies that overworked their horses, and sportsmen who practiced marksmanship by tossing live captive pigeons in the air. That he was mocked by some, denounced by others, and labeled “the Great Meddler” in the press bothered him not at all.

So who was this meddler and what was he up to? The son of a wealthy New York shipbuilder who left him a fortune, Henry Bergh indeed had no need to smirch his hands with toil. In his early years he was something of a dilettante, scribbling poetry and plays of no great value, enjoying the city’s social life, and traveling abroad with his young wife. Seeing a bull fight in Spain, he was appalled by the bloody spectacle, especially the crowd’s cheers when the horses were gored, and when the bulls were taunted and then killed.

Thanks to his social and political connections, Henry Bergh in 1862 was appointed secretary and acting vice consul to the American legation in St. Petersburg, Russia, and it was there, so the story goes, that the incident that would shape his life occurred. One day, while riding through the streets in a fancy carriage, he saw a Russian peasant beating his fallen cart horse. Shocked, he order his coachman to stop and to tell the peasant to stop beating the horse. How the incident ended isn’t clear, but it determined Bergh to launch a campaign in the U.S. against such wanton cruelty to animals. Returning to America, he stopped off in England, where he consulted the Earl of Harrowby, president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, following which he decided to found a similar society in New York.

Back in the city he urged friends and acquaintances to support his campaign, gave lectures to children and adults, got letters published in newspapers and magazines, and persuaded prominent citizens to sign a petition that he took to Albany, where he lobbied the state legislature to good effect. As a result, in 1866 the legislature granted a charter for the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), of which he became the president, with authorization to enforce the new law that it passed, making cruelty to animals illegal.

Armed with the new law, Bergh and his agents patrolled the streets and docks to enforce it, often risking physical assault. Seeing an overloaded wagon too heavy for the beast trying to haul it, they made the driver lighten his load. Sick and decrepit horses were taken from their drivers and sent to the Society’s animal hospital, and suffering horses were likewise rescued from stables. If an animal fell into a ditch or an excavation (of which there were plenty in the ever expanding city), the Society used a derrick to lift it out. They inspected slaughterhouses, looked everywhere for raw flesh under collars and saddles, protested when dairymen kept cows chained to their stalls, and created public fountains where animals could drink. And to replace the live pigeons used by sportsmen in shooting matches, Bergh himself invented the clay pigeon still in use today.

P.T. Barnum Early in his campaign he clashed with P.T. Barnum, the leading American showman of the time and self-proclaimed master of humbug. In December 1866 Bergh wrote a letter to the managers of Barnum’s new museum to protest the feeding of snakes with live animals, a practice that he called “semi-barbarian”; if they persisted, he threatened prosecution. Returning from a trip to the West, Barnum found the letter and answered it in March 1867, stating that the museum would continue to feed its animals in accordance with the laws of nature; enclosed was a letter Barnum had solicited from the noted biologist Louis Agassiz, confirming Barnum’s insistence that the only way snakes eat their food is in its natural state: alive.

P.T. Barnum Early in his campaign he clashed with P.T. Barnum, the leading American showman of the time and self-proclaimed master of humbug. In December 1866 Bergh wrote a letter to the managers of Barnum’s new museum to protest the feeding of snakes with live animals, a practice that he called “semi-barbarian”; if they persisted, he threatened prosecution. Returning from a trip to the West, Barnum found the letter and answered it in March 1867, stating that the museum would continue to feed its animals in accordance with the laws of nature; enclosed was a letter Barnum had solicited from the noted biologist Louis Agassiz, confirming Barnum’s insistence that the only way snakes eat their food is in its natural state: alive. Bergh answered at once, quoting at length the account of an anonymous museum visitor who described in detail the terror of a rabbit thrust into the cage of a boa constrictor, and deploring Agassiz’s condoning of such a cruel practice. This prompted a long and heated response from Barnum, who denounced Bergh’s “insulting epithets” and “ungentlemanly manner,” his “dictatorial air” and “thoughtless and absurd statements,” his “miserable pettifogging.” Clearly, Bergh had touched a raw nerve, prompting the showman to get the exchange of letters published in the New York World, which called the controversy “funny as well as instructive.” There is little doubt that Barnum meant to subject Bergh to public mockery.

In spite of Barnum’s hostility, Bergh and his agents persisted in the face of mockery, indifference, and even physical abuse, and gradually won the public over, thus creating a radical change in how New Yorkers viewed animals and treated them. “An angel in a top hat” was how Bergh’s supporters described him, though they might just as well have said “human dynamo.” His lecture tour in the West in 1873 prompted the formation of several societies similar to the one he had founded in New York. In 1879 Scribner’s Magazine declared that Bergh had invented “a new type of goodness.” By 1886, 39 states had adopted statutes protecting animals based on the original one in New York. When, worn out by his efforts, Bergh died in 1888, Barnum was a pallbearer at his funeral, for Bergh’s tireless efforts and obvious sincerity had finally won even the master showman over. For what good-hearted citizen could long resist Henry Bergh, a man addicted to benevolence?

Reformers rarely achieve their goals easily. The abolitionists campaigned for decades, but only the coming of the Civil War made possible the abolition of slavery. Similarly, the suffragettes fought long and hard before finally getting the vote for women. Why did Bergh obtain the desired New York State legislation so quickly? The abolitionists were stymied for years by the slaveholders, who held their own in the Senate and the Supreme Court, got proslavery men elected President, and intimidated well-meaning citizens with the threat of secession. And the suffragettes had to overcome the prevailing opinion, held by most men and many women, that the woman’s place was in the home, and that women were incapable of dealing with the issues of public life. Bergh, on the other hand, had to cope with mockery and disbelief, but no entrenched opposition. Who, after all, wanted to stand tall in the public arena as a defender of the brutal treatment of animals? His appeal to society’s better instincts triumphed, and victory came quickly.

Bergh’s Society was one of many operating in nineteenth-century New York, each reflecting someone’s intense concern with social betterment. As for instance:

· The Society for the Encouragement of Faithful Domestic Servants· The Society for the Prevention of Crime· The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children· The Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors· The Society for the Relief of Poor Widows· The Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents· The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Piety among the Poor· The Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females

And many more.

Clearly, benevolence was rampant in the city. But if these names strike us as quaint and condescending, and smack of excessive middle-class do-goodism, it’s worth remembering that nineteenth-century New York, like Dickens’s London, was rife with poverty, ignorance, and vice, to cope with which there as yet were few agencies of the city or state. But the good folk of the middle class couldn’t easily ignore these conditions, since rich and poor lived in close proximity. In post-Civil War New York, Fifth Avenue was the acclaimed axis of elegance, lined with imposing mansions and spiky spires of churches. But if in the evening one walked a mere block west to Sixth Avenue, one found oneself in the Tenderloin – the “Satan’s Circus” of many a sermon – with pretty-waiter-girl saloons, gambling dens, brothels, and cheap hotels with rooms available by the hour or the night, its sidewalks alive with streetwalkers, pimps, wisecracking loafers, and drunks. To eliminate these alleged disreputables was the goal of many a do-gooder, sometimes affiliated with a church and sometimes not – an addiction to benevolence with a cutting edge.

The Tenderloin, "Satan's Circus." At least they were having fun.

The Tenderloin, "Satan's Circus." At least they were having fun.A last word on addictions: benign or otherwise, we need them. They can destroy you or give your life a purpose; either way, they liven things up. If you have an addiction, you’ll never be bored.

Note on Goldman Sachs: Followers of this blog know how, second only to Monsanto, I love Goldman Sachs. (See post #158, “Goldman Sachs: Vampire Squid or Martyred Innocent?”) Having for 146 years been the bank of the powerful and privileged, it has now announced that, starting in 2016, it will offer loans of a paltry few thousand dollars to ordinary Americans, people like you and me, and (a new twist) it will do so online. This is unprecedented, and risky, too, since Goldman has no experience dealing with ordinary borrowers with limited financial means. Why then is it doing it? Make no mistake, it sniffs an opportunity, smells profit. So the vampire squid (not my image, though I love it) is reaching its tentacles into yet another realm of finance. Borrowers, beware. The squid does not enjoy a good reputation, has a genius for profiting from the woes and folly of others.

Coming soon: Catastrophes. Do the years 1832 and 1888 mean anything to you? If not, they will, for in those years New Yorkers had a lot to put up with. And after that, West Village Wonders and Horrors, with a look at a pink palazzo right down the street from me that maybe should never have been built.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

Published on June 21, 2015 05:12

June 14, 2015

184. Cast Iron and Terra Cotta: What I Discovered on 11th Street

Until recently my only personal association with cast iron was a skillet that I owned long ago and that served me well, as long as I dried it carefully so as to prevent rust. As for terra cotta (“baked earth” in Italian), for me it meant ceramic figurines of one ancient culture or another, and panels of sculpted figures by Luca della Robbia that I had once seen in distant Florence. Though vaguely aware of cast-iron buildings in Soho, I had never really looked at them closely, and had no idea that terra cotta had anything to do with New York City architecture. Until, that is, I heard of two nonprofits active in the city: Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture and Friends of Terra Cotta. At which point I decided that, if they each had friends organized in a nonprofit, cast iron and terra cotta bore looking into. A glance or two online convinced me that both were significant in the history of New York City architecture and deserved to be seen in the field, meaning, in buildings in this city.

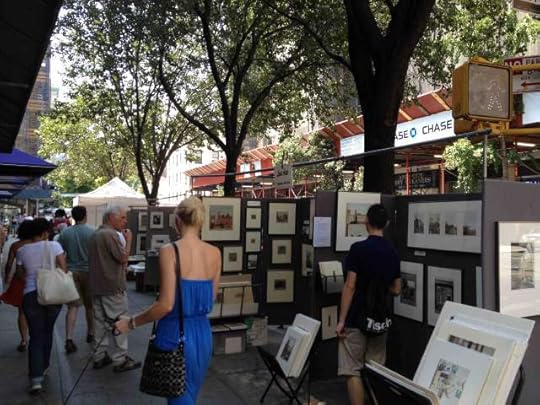

Cast iron first. Learning that there was a prime example of it at 67 East 11th Street – my street – right here in Greenwich Village, I made seeing it one of two goals for a walk in that direction, the other goal being the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit, where an artist friend of mine was exhibiting. So began yet another memorable walk in the city. (For other walks of mine, see post #180, “Walking in New York.”) This walk took me, with my friend John, across town on West 11th Street, passing a number of significant sites:

· At Seventh Avenue and West 11th Street, construction of a luxury tower on the site of St. Vincent’s Hospital, now demolished. Why the hospital, founded in 1849 and once one of the best in the city, went bankrupt in 2010 remains a mystery, and one well worth probing. As a Villager who was once treated there, and who mourns the loss of the only full-service hospital in the area, I resent the construction of still more luxury housing and can only view this coming monstrosity as an insult to the psyche. A sour note right at the start of the walk.

A Greek Revival house on West 11th Street.

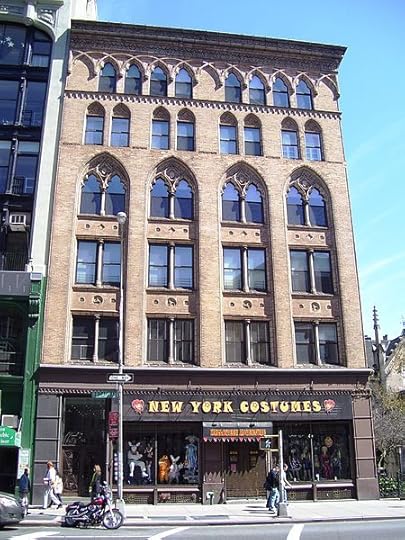

A Greek Revival house on West 11th Street.Beyond My Ken· Along West 11th Street between Seventh and Sixth Avenues, a number of well-preserved Greek Revival houses and brownstones – for me, always a source of delight, and welcome relief after the painful reminder of St. Vincent’s.· Just beyond Sixth Avenue, a triangular sliver of a Jewish cemetery established in 1805. The Jews of that time were Sephardic Jews whose ancestors had fled persecution in Christian Spain and Portugal and finally found refuge in New York. When the cemetery, the third Jewish cemetery in the city (though labeled the second), was first established, there were cow pastures nearby, and children would jump the fence to steal apples from apple trees growing among the graves. But in 1830 the city planned an extension of 11th Street right through the cemetery westward to Sixth Avenue. Faced with the loss of their cemetery, the Jews petitioned the city to preserve a small slice of it not needed for the street extension, and their request was granted. Blocked off now by a wall and overshadowed by the neighboring buildings, the cemetery is easy to miss, but when walking that way I never fail to glance at it through a grilled gate; some twenty worn headstones survive.· At 18 West 11th Street, a new row house whose jutting angular façade clashes with the older buildings on the block: a reminder that this modernist upstart is built on the site of an old Greek Revival townhouse built in 1845 and totally demolished on March 6, 1970, by an explosion. While the owners of the building, a radio-station executive and his wife, were vacationing in the Caribbean, their little girl and her Weather Underground friends were making bombs in the basement. Unfortunately – or maybe fortunately, given their intentions -- none of them had experience in handling explosives, with the obvious result. The blast killed three of them and reduced the building to rubble, but two others, stunned and bleeding, survived and escaped. That the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the jutting oddity now blemishing the site is, to put it mildly, shocking. It’s their job to prevent such anomalies.

The Conservative Synagogue of Fifth Avenue.

The Conservative Synagogue of Fifth Avenue.Beyond My Ken· Just across Fifth Avenue, the Conservative Synagogue of Fifth Avenue, a small two-story structure at 11 East 11th Street, its white façade with black trim set well back from the street and enjoying that rarity in Manhattan, a plot in front with benches and a bit of greenery. Hardly noticed by most passersby, the quaint little building has undergone many a change. Built in the 1830s as the carriage house for a Fifth Avenue residence, it was set well back from the street by the builder, a wealthy attorney, so his genteel neighbors wouldn’t be assailed by the smell of manure. In 1867 a police raid on the little building revealed, smack in the midst of one of the city’s most fashionable neighborhoods, a disorderly house with five women in residence. Converted to a garage and then to a one-family residence in the early twentieth century, the building survived, squeezed in between a hotel and an apartment building. In 1930, a year after the Great Crash, the occupant, a Wall Street broker, was so disheartened by stock-market losses that he committed suicide. Preserved over the years because of its unique charm, in 1960 no. 11 East 11th Street became a synagogue.· On a stoop of one of the old buildings in the block, a Nepalese mother with her young son, both fluent in English, selling lemonade as a benefit for the victims of the recent earthquakes in Nepal. John and I talked with her briefly, and we each bought a lemonade for a dollar.· Beyond University Place, at the corner of East 11thand Broadway, my first goal, the cast-iron building at 67 East 11th, an impressive structure indeed. More of that anon.· Along University Place from 11th Street down, bustling crowds visiting the Art Exhibit and, at a stand near West 9thStreet, the second goal of the walk, our friend Henry’s work on display, with a whole bunch of paintings in a new style for him, fantasy landscapes reflecting scenes of his imagination rather than re-creations of real scenes he had observed. I admired all the new works, and especially the one that had been awarded the Exhibit’s top prize for landscapes.

· At Sixth and Greenwich Avenues, as I came back alone along West 9th Street from the exhibit, the Jefferson Market Garden, open to the public and celebrating its fortieth anniversary, having been created in 1975 on the site of the demolished Women’s House of Detention, a West Village Bastille of ill repute. I took a brief stroll through the grounds, reveling in the flowers and foliage and regretting not one bit the prison that once loomed gloomily on the site, its inmates shrieking obscenities and calling down to friends on the street. There are times when gentrification, that bane of preservationists, pays off.

So ended my stroll through the Village.

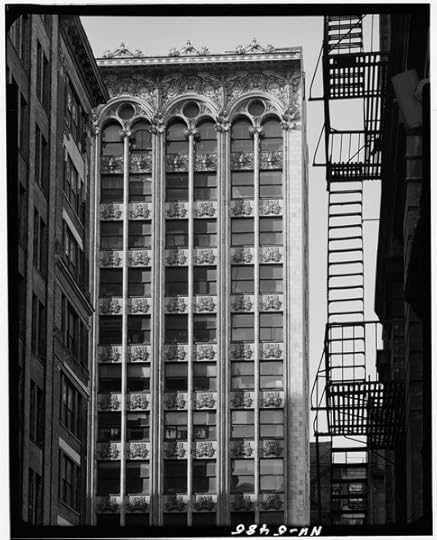

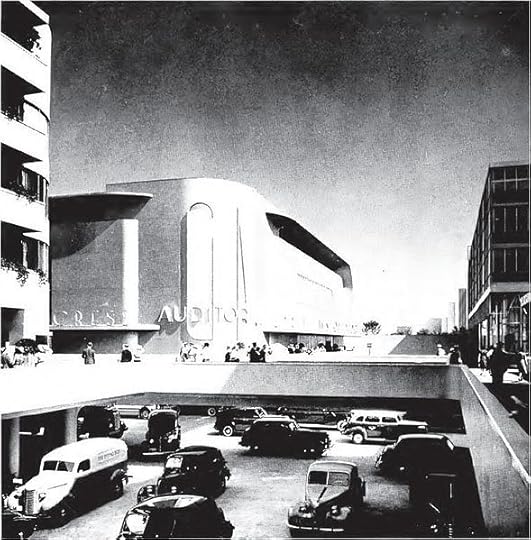

Now about 67 East 11th Street. Built in 1868, the huge seven-story structure (though I count only six) takes up much of the northern or uptown side of the block between University Place and Broadway. Four tiers of Corinthian columns, their capitals adorned with intricately molded foliage, stretch across the beige-tinted façade all the way to Broadway, framing the tall windows, each window topped by a rounded arch. The ground floor is occupied by shops: KidVille, the Bergino Baseball Clubhouse with baseball memorabilia, and Le Pain Quotidien (the Daily Pain, as I like to call it). Crowning the building above the tiers of columns, alas, is a top floor that looks like a drab substitute for the original mansard roof. Massive, the building lacks the charm of Greek Revival and brownstone houses standing in tight-packed rows like a baker’s loaves on a shelf, but it has a solitary epic grandeur, a magnificence that struck me at once and steadily grew as I continued to view it.

The structure served originally to house McCreery’s dry-goods store on Ladies’ Mile, a stretch of Broadway occupied in the Gilded Age by fashionable department stores catering to the wives of the affluent. Just across the avenue was (and still is) Grace Episcopal Church, a splendid Gothic edifice that served those same wives and their husbands, the source of all their wealth. In 1903 McCreery’s moved out, following the uptown migration of its clientele, and the building became a factory making ladies’ shoes and handbags. Having survived a fire in 1971, no. 67 was converted to a co-op with 144 apartments in 1973, the first such conversion of a loft building in the city. Known today as the Cast Iron Building, the structure has landmark status and is advertised as offering a renovated lobby; a doorman, concierge, and security guard; high ceilings, fabulous views, and an elevator; and for some units a sun-drenched terrace. Tempted to move in? Fine, but a one-bedroom apartment will cost you close to $1 million or more.