Clifford Browder's Blog, page 44

October 26, 2014

150. Wall Street, Greed, and Addiction

"Wall Street! Who shall fathom the depth and the rottenness of thy mysteries? Has Gorgon passed through thy winding labyrinth, turning with his smile every thing to stone – hearts as well as houses? Art thou not the valley of riches told of by the veracious Sinbad, where millions of diamonds lay glistening like fiery snow, but which was guarded on all sides by poisonous serpents, whose bite was death and whose contact was pollution?"

So spoke journalist George G. Foster in his book entitled New York in Slices, published in New York in 1849. Which goes to show that Wall Street – meaning not just the street itself but the whole financial community – has from an early date inspired a mix of fascination, puzzlement, and censure.

This post is not about the history of Wall Street, which was dealt with in posts #95, 96, 97; it’s about greed and addiction. Let’s continue where those posts left off, with a look at the façade of the New York Stock Exchange, in the heart, figuratively and literally, of Wall Street. Since 1903 the Exchange’s home has been a noble neoclassical edifice in white marble fronted by six massive Corinthian columns at 18 Broad Street, just south of Wall. It suggests a Greek temple, and its pediment crammed with statuary shows Integrity Protecting the Works of Man. An amply robed Integrity looms centrally, with figures representing Agriculture and Mining on the right, and Science, Industry, and Invention on the left. Who the infants near Integrity’s feet represent, I haven’t been able to determine. But Integrity rules over all … at least in the sculptor’s mind. A reassuring thought, is it not?

The Stock Exchange, guarded by security personnel and police with M16

The Stock Exchange, guarded by security personnel and police with M16

machine guns and police dogs, following the 9/11 attack.

Kowloonese Integrity in the center, stretching both arms out with clenched fists. Agriculture and Mining on the right, with Agriculture shown here as a man bending under the weight of a sack of grain, and a woman in a bonnet and pioneer dress leading a sheep. Science and Industry on the left, shown here as a man pushing a lever.

Integrity in the center, stretching both arms out with clenched fists. Agriculture and Mining on the right, with Agriculture shown here as a man bending under the weight of a sack of grain, and a woman in a bonnet and pioneer dress leading a sheep. Science and Industry on the left, shown here as a man pushing a lever.

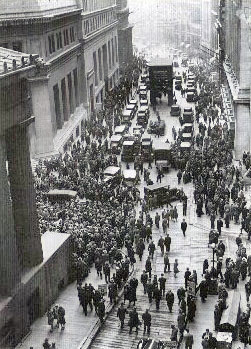

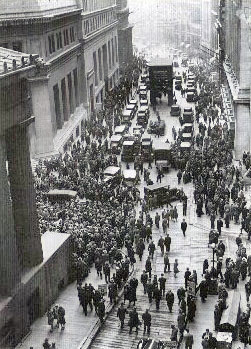

The crowd outside the Exchange

The crowd outside the Exchange

following the 1929 Crash. Now let’s flash back to Thursday, October 25, 1929, Black Thursday, when turmoil raged in the Stock Exchange as prices plummeted, margin calls went out, a crowd gathered outside in the street, and rumors of suicides circulated. That afternoon all eyes were on Richard Whitney, acting vice-president of the New York Stock Exchange in the absence of the Exchange’s president, who was off on an extended honeymoon in Hawaii. A tall, handsome, muscular man, at 1:30 p.m. Whitney walked confidently onto the trading floor and, stopping at Post No. 2, loudly announced, “I bid 205 for 10,000 Steel!” – a bid well above the current market price. Immediately a huge cry went up from the trading floor. Whitney then placed similar bids for AT&T, Anaconda Copper, General Electric, and other blue-chip stocks. Behind him were the combined resources of the leading bankers of the day, to the tune of $130 million, on whose behalf he was acting.

After this show of confidence by Whitney, the panic subsided and people took heart; maybe the dramatic slide was over. Suddenly famous, Whitney looked like a hero, the “Great White Knight” of Wall Street. In the following year the Exchange elected him their president, and in that capacity he made speeches around the country emphasizing the high character of the New York Stock Exchange and the companies that were traded there. “Business Honesty” was the name of one of his speeches, and he stressed an ethical corporate environment as the key to recovery. Above all, the Exchange was not to blame.

Alas, Whitney’s dramatic gesture on the trading floor, and the speeches that followed later, were not enough. On Monday, October 28, the plunge resumed, as the Dow dropped 13%, and on the following day, Black Tuesday, it lost another 12% in the heaviest trading ever. The Great Crash could not be stemmed; stocks recovered, fell again, recovered a bit, and fell once more, not reaching the bottom until 1932, by which time the Great Depression was well under way.

(Wall Street’s history abounds in Black Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Saturday seems to have been immune to financial disasters, maybe because, in recent times, the New York Stock Exchange is closed then for trading. And the Sabbath has of course been spared.)

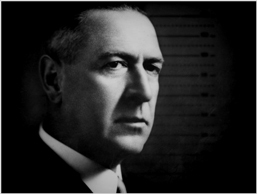

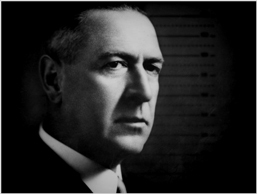

Who was Richard Whitney, this proponent of financial integrity? Born in 1888 to an old patrician family in Boston, he had attended Groton School and Harvard College, then migrated to New York in 1910 to establish his own bond brokerage business and purchase a seat on the prestigious New York Stock Exchange. A member of the city’s elite social clubs and treasurer of the New York Yacht Club, he lived lavishly with his family in a five-story red brick townhouse at 115 East 73rd Street. He also owned a 495-acre thoroughbred horse and cattle farm in Far Hills, New Jersey, was president of the Essex Fox Hounds, and rode elegantly to the hounds on one of his twenty horses. A quintessential Wasp, well groomed, arrogant, and snobbish, he quietly preventing Jewish applicants from attaining significant positions at the Exchange. But to most observers he was the epitome of the gentleman banker.

Everything about Richard Whitney said money; in fact, it almost screamed it. The trouble was, he didn’t have enough of it. His life style required an income that, even with all his connections, he simply didn’t have. He speculated, he suffered severe losses. So finally he went into debt and went in deep.

Flash forward to 1938, when the comptroller of the New York Stock Exchange reported to his superiors that he had absolute proof that Whitney, who had retired as the Exchange’s president in 1935, that Whitney’s company was insolvent and Whitney himself an embezzler. He and his company soon declared bankruptcy and on March 10 he was indicted for embezzlement by District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey. It soon came to light that he had stolen money from the Stock Exchange’s Gratuity Fund, the New York Yacht Club, and his father-in-law’s estate. The financial elite might have forgiven him almost anything, but stealing from the Yacht Club was unpardonable. Urbane and self-possessed, Whitney pleaded guilty to the charges and was sentenced to 5 to 10 years at Sing Sing. Thousands showed up at Grand Central Station to witness a former head of the Exchange being taken to prison handcuffed to two petty racketeers. Informed of his downfall, President Roosevelt, also a graduate of Groton and Harvard, shook his head sadly and murmured, “Poor Groton. Poor Harvard. Poor Dick.” (He might have added, "Poor Stock Exchange," or perhaps, "Poor Yacht Club.") Though Whitney symbolized the very interests that the President’s New Deal was fighting, Roosevelt refused to demonize Whitney, perhaps because they shared the same privileged background.

At first censorious, public opinion had turned sympathetic, seeing in him a stoic martyr who even in disgrace remained a gentleman. Respect for him extended even to Sing Sing, where other inmates as well as guards lifted their caps to him and asked for his autograph. Assigned at first to mop-and-broom duty, he was soon teaching in the prison school and playing on the baseball team. A model prisoner, he served 3 years and 4 months of his term, was released on parole in August 1941, and was reunited with his ever loyal wife. Banned from dealing in securities in New York State, he became manager of a dairy farm and, later, president of a textile company. Living quietly in Far Hills, he died there in 1974.

Richard Whitney was neither the first nor the last Wall Streeter to be caught cheating. Today, the wake of the 2008 panic and resulting Great Recession, the top executives of the biggest (“too big to fail”) U.S. banks have looked suspect to many. Jamie Dimon, top honcho of my own dear J.P. Morgan Chase, has been criticized for presiding over his bank’s six-billion-dollar loss in a 2012 trade in its London office, and its sale of risky mortgages to investors unaware of the risks, leading to an unprecedented $13 billion settlement with the U.S. Justice Department in 2013, with further investigations and resulting settlements pending. Like Whitney, Mr. Dimon is a handsome, well-tailored, clean-cut gentleman, but so far, one unsmirched by prosecution. When questioned by the Senate Banking Committee in 2012, he was treated deferentially like a visiting dignitary and a financial guru oozing deep wisdom, and not like an irresponsible operator who, so his critics assert, had endangered the whole financial system of the country. Immaculately groomed and urbane, though at times showing signs of nervousness, Dimon, like Whitney long before him, seems to elicit admiration, sympathy, and respect. (Dimon is of Greek American stock and not a WASP, which shows progress of a kind, I suppose.)

Jamie at Davos, Switzerland, in 2013, at the annual World Economic Forum. Immaculately

Jamie at Davos, Switzerland, in 2013, at the annual World Economic Forum. Immaculately

groomed, and looking like a Ruler of the World.

World Economic Forum

What drives these Wall Street people? The nineteenth-century speculator Daniel Drew confessed to a friend, in a rare moment of candor, that it wasn’t the money itself that he loved, but the wild excitement of the game: “I must have excitement, or I should die.” But I would suggest that it’s both the money and the excitement of the game, and that it’s a matter of addiction. I used to think that addiction involved only substance abuse -- alcohol, tobacco, and drugs. But then a friend confessed to me that he was addicted to sex – for me, an innocent when it comes to addiction, a novel and enigmatic idea. To explain, he said that, periodically, if he didn’t go out every night and have sex with another man, he felt totally unworthy and depressed. Hearing that, I had to accept the fact that sex too could be an addiction. So how about money? Can greed also be, in the full and literal sense of the word, addictive?

Relevant here is the article “For the Love of Money” by former hedge-fund trader Sam Polk, which appeared in the Sunday New York Times of January 19, 2014. Polk tells how his dreams of being rich had been nourished by his father, a salesman with huge dreams that never seemed to materialize, while the family lived from paycheck to paycheck off his mother’s salary. When, at age 22, Polk walked onto the trading floor at Credit Suisse First Boston to begin a summer internship, and saw an array of glowing TV screens, high-tech computer monitors, and phone turrets, he knew at once what he wanted to do with the rest of his life: play this video game to become rich and have power.

So began his career as a trader. Three weeks into his internship his girlfriend dumped him: “I don’t like who you’ve become.” Devastated, he consulted a counselor who showed him how he was using drugs and alcohol to blunt the powerlessness he had felt as a kid; his underlying trouble, she explained, was a “spiritual malady.”

A year or so later, having gotten off drugs and alcohol and graduated from Columbia College, he pestered a managing director at Bank of America until the manager took a chance and hired him. At the end of his first year he was thrilled to receive a $40,000 bonus. But a week later a trader only four years his senior was hired away by another outfit for a salary of $900,000 – 22 times the size of his bonus – and he was at once consumed by envy, and then excited by how much money was available.

So it went. He worked hard, moved up the Wall Street ladder, became a bond and credit default swap trader (whatever that is). After four years in his new job Citibank offered him $1.75 million a year. At age 25 he reveled in money and power. But when, at a meeting, he suggested that the new hedge-fun regulations that everyone on Wall Street was decrying might be better for the system as a whole, the room went quiet and his boss shot him a withering look and said emphatically that he couldn’t think about the system as a whole, only about his company. At which point Polk began to view Wall Street with new eyes.

Now Polk noticed how traders hurled vitriol at the government for limiting their bonuses after the crash, and were infuriated by any mention of higher taxes. Having always envied the men who earned more than he did, he now began to be embarrassed for them and himself. Though he made more money in a single year than his mother, a nurse practitioner, had made in her whole life, he realized that, unlike her, he wasn’t really doing anything, wasn’t useful or necessary to society. And having foreseen the 2008 crash and made money off of it, he himself now didn’t like who he’d become. So he decided to get out.

Polk now realized that he was an addict, craving more money just as an alcoholic craves alcohol. And like any addict, he had an incredibly difficult time shaking his habit. All too often he woke up in the middle of the night terrified at the thought of running out of money, of later feeling like an idiot for giving up his one chance to be really important. In time these feelings abated, and he realized that he had enough money and, if he needed more, he could earn it. But just as a recovered alcoholic still craves alcohol, so he still at times craves money and buys a lottery ticket.

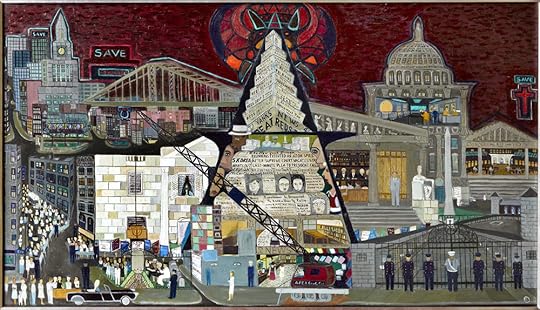

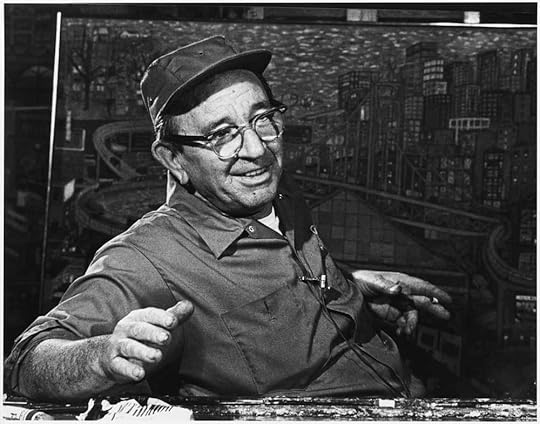

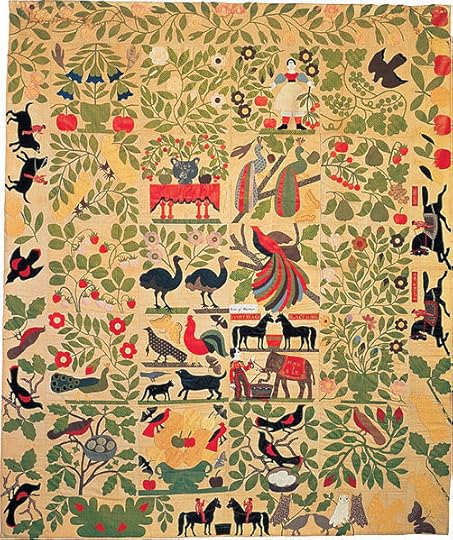

Avarice, an engraving by the Dutch artist Jacob Matham (1571-1631).

Avarice, an engraving by the Dutch artist Jacob Matham (1571-1631).

Now Polk speaks in jails and juvenile detention centers about getting sober, teaches a writing class for girls in the foster system, and manages a nonprofit called Groceryships to help poor families struggling with obesity and food addiction. Which reminds me of a recovered alcoholic I once knew who enlisted in Alcoholics Anonymous to help other alcoholics get free of their addiction. Yet there is no 12-step program for wealth addicts. Why not? he asks. Because our culture supports and even praises the addiction. The superrich appear on the magazine covers at every newsstand, have become our cultural gods. So we all bear some responsibility, Polk insists, for letting wealth addicts exert so much influence over our nation. To which I would add the suggestion that, in a capitalist society, this is close to inevitable. We have always adulated wealth and those who have it.

Sam Polk’s article – well worth reading in its entirety – provides a clear and emphatic answer to the question posed earlier. Can greed become an addiction? Yes!

Coming soon: I haven't the slightest idea. I just hope it happens.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

So spoke journalist George G. Foster in his book entitled New York in Slices, published in New York in 1849. Which goes to show that Wall Street – meaning not just the street itself but the whole financial community – has from an early date inspired a mix of fascination, puzzlement, and censure.

This post is not about the history of Wall Street, which was dealt with in posts #95, 96, 97; it’s about greed and addiction. Let’s continue where those posts left off, with a look at the façade of the New York Stock Exchange, in the heart, figuratively and literally, of Wall Street. Since 1903 the Exchange’s home has been a noble neoclassical edifice in white marble fronted by six massive Corinthian columns at 18 Broad Street, just south of Wall. It suggests a Greek temple, and its pediment crammed with statuary shows Integrity Protecting the Works of Man. An amply robed Integrity looms centrally, with figures representing Agriculture and Mining on the right, and Science, Industry, and Invention on the left. Who the infants near Integrity’s feet represent, I haven’t been able to determine. But Integrity rules over all … at least in the sculptor’s mind. A reassuring thought, is it not?

The Stock Exchange, guarded by security personnel and police with M16

The Stock Exchange, guarded by security personnel and police with M16machine guns and police dogs, following the 9/11 attack.

Kowloonese

Integrity in the center, stretching both arms out with clenched fists. Agriculture and Mining on the right, with Agriculture shown here as a man bending under the weight of a sack of grain, and a woman in a bonnet and pioneer dress leading a sheep. Science and Industry on the left, shown here as a man pushing a lever.

Integrity in the center, stretching both arms out with clenched fists. Agriculture and Mining on the right, with Agriculture shown here as a man bending under the weight of a sack of grain, and a woman in a bonnet and pioneer dress leading a sheep. Science and Industry on the left, shown here as a man pushing a lever. The crowd outside the Exchange

The crowd outside the Exchangefollowing the 1929 Crash. Now let’s flash back to Thursday, October 25, 1929, Black Thursday, when turmoil raged in the Stock Exchange as prices plummeted, margin calls went out, a crowd gathered outside in the street, and rumors of suicides circulated. That afternoon all eyes were on Richard Whitney, acting vice-president of the New York Stock Exchange in the absence of the Exchange’s president, who was off on an extended honeymoon in Hawaii. A tall, handsome, muscular man, at 1:30 p.m. Whitney walked confidently onto the trading floor and, stopping at Post No. 2, loudly announced, “I bid 205 for 10,000 Steel!” – a bid well above the current market price. Immediately a huge cry went up from the trading floor. Whitney then placed similar bids for AT&T, Anaconda Copper, General Electric, and other blue-chip stocks. Behind him were the combined resources of the leading bankers of the day, to the tune of $130 million, on whose behalf he was acting.

After this show of confidence by Whitney, the panic subsided and people took heart; maybe the dramatic slide was over. Suddenly famous, Whitney looked like a hero, the “Great White Knight” of Wall Street. In the following year the Exchange elected him their president, and in that capacity he made speeches around the country emphasizing the high character of the New York Stock Exchange and the companies that were traded there. “Business Honesty” was the name of one of his speeches, and he stressed an ethical corporate environment as the key to recovery. Above all, the Exchange was not to blame.

Alas, Whitney’s dramatic gesture on the trading floor, and the speeches that followed later, were not enough. On Monday, October 28, the plunge resumed, as the Dow dropped 13%, and on the following day, Black Tuesday, it lost another 12% in the heaviest trading ever. The Great Crash could not be stemmed; stocks recovered, fell again, recovered a bit, and fell once more, not reaching the bottom until 1932, by which time the Great Depression was well under way.

(Wall Street’s history abounds in Black Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Saturday seems to have been immune to financial disasters, maybe because, in recent times, the New York Stock Exchange is closed then for trading. And the Sabbath has of course been spared.)

Who was Richard Whitney, this proponent of financial integrity? Born in 1888 to an old patrician family in Boston, he had attended Groton School and Harvard College, then migrated to New York in 1910 to establish his own bond brokerage business and purchase a seat on the prestigious New York Stock Exchange. A member of the city’s elite social clubs and treasurer of the New York Yacht Club, he lived lavishly with his family in a five-story red brick townhouse at 115 East 73rd Street. He also owned a 495-acre thoroughbred horse and cattle farm in Far Hills, New Jersey, was president of the Essex Fox Hounds, and rode elegantly to the hounds on one of his twenty horses. A quintessential Wasp, well groomed, arrogant, and snobbish, he quietly preventing Jewish applicants from attaining significant positions at the Exchange. But to most observers he was the epitome of the gentleman banker.

Everything about Richard Whitney said money; in fact, it almost screamed it. The trouble was, he didn’t have enough of it. His life style required an income that, even with all his connections, he simply didn’t have. He speculated, he suffered severe losses. So finally he went into debt and went in deep.

Flash forward to 1938, when the comptroller of the New York Stock Exchange reported to his superiors that he had absolute proof that Whitney, who had retired as the Exchange’s president in 1935, that Whitney’s company was insolvent and Whitney himself an embezzler. He and his company soon declared bankruptcy and on March 10 he was indicted for embezzlement by District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey. It soon came to light that he had stolen money from the Stock Exchange’s Gratuity Fund, the New York Yacht Club, and his father-in-law’s estate. The financial elite might have forgiven him almost anything, but stealing from the Yacht Club was unpardonable. Urbane and self-possessed, Whitney pleaded guilty to the charges and was sentenced to 5 to 10 years at Sing Sing. Thousands showed up at Grand Central Station to witness a former head of the Exchange being taken to prison handcuffed to two petty racketeers. Informed of his downfall, President Roosevelt, also a graduate of Groton and Harvard, shook his head sadly and murmured, “Poor Groton. Poor Harvard. Poor Dick.” (He might have added, "Poor Stock Exchange," or perhaps, "Poor Yacht Club.") Though Whitney symbolized the very interests that the President’s New Deal was fighting, Roosevelt refused to demonize Whitney, perhaps because they shared the same privileged background.

At first censorious, public opinion had turned sympathetic, seeing in him a stoic martyr who even in disgrace remained a gentleman. Respect for him extended even to Sing Sing, where other inmates as well as guards lifted their caps to him and asked for his autograph. Assigned at first to mop-and-broom duty, he was soon teaching in the prison school and playing on the baseball team. A model prisoner, he served 3 years and 4 months of his term, was released on parole in August 1941, and was reunited with his ever loyal wife. Banned from dealing in securities in New York State, he became manager of a dairy farm and, later, president of a textile company. Living quietly in Far Hills, he died there in 1974.

Richard Whitney was neither the first nor the last Wall Streeter to be caught cheating. Today, the wake of the 2008 panic and resulting Great Recession, the top executives of the biggest (“too big to fail”) U.S. banks have looked suspect to many. Jamie Dimon, top honcho of my own dear J.P. Morgan Chase, has been criticized for presiding over his bank’s six-billion-dollar loss in a 2012 trade in its London office, and its sale of risky mortgages to investors unaware of the risks, leading to an unprecedented $13 billion settlement with the U.S. Justice Department in 2013, with further investigations and resulting settlements pending. Like Whitney, Mr. Dimon is a handsome, well-tailored, clean-cut gentleman, but so far, one unsmirched by prosecution. When questioned by the Senate Banking Committee in 2012, he was treated deferentially like a visiting dignitary and a financial guru oozing deep wisdom, and not like an irresponsible operator who, so his critics assert, had endangered the whole financial system of the country. Immaculately groomed and urbane, though at times showing signs of nervousness, Dimon, like Whitney long before him, seems to elicit admiration, sympathy, and respect. (Dimon is of Greek American stock and not a WASP, which shows progress of a kind, I suppose.)

Jamie at Davos, Switzerland, in 2013, at the annual World Economic Forum. Immaculately

Jamie at Davos, Switzerland, in 2013, at the annual World Economic Forum. Immaculately groomed, and looking like a Ruler of the World.

World Economic Forum

What drives these Wall Street people? The nineteenth-century speculator Daniel Drew confessed to a friend, in a rare moment of candor, that it wasn’t the money itself that he loved, but the wild excitement of the game: “I must have excitement, or I should die.” But I would suggest that it’s both the money and the excitement of the game, and that it’s a matter of addiction. I used to think that addiction involved only substance abuse -- alcohol, tobacco, and drugs. But then a friend confessed to me that he was addicted to sex – for me, an innocent when it comes to addiction, a novel and enigmatic idea. To explain, he said that, periodically, if he didn’t go out every night and have sex with another man, he felt totally unworthy and depressed. Hearing that, I had to accept the fact that sex too could be an addiction. So how about money? Can greed also be, in the full and literal sense of the word, addictive?

Relevant here is the article “For the Love of Money” by former hedge-fund trader Sam Polk, which appeared in the Sunday New York Times of January 19, 2014. Polk tells how his dreams of being rich had been nourished by his father, a salesman with huge dreams that never seemed to materialize, while the family lived from paycheck to paycheck off his mother’s salary. When, at age 22, Polk walked onto the trading floor at Credit Suisse First Boston to begin a summer internship, and saw an array of glowing TV screens, high-tech computer monitors, and phone turrets, he knew at once what he wanted to do with the rest of his life: play this video game to become rich and have power.

So began his career as a trader. Three weeks into his internship his girlfriend dumped him: “I don’t like who you’ve become.” Devastated, he consulted a counselor who showed him how he was using drugs and alcohol to blunt the powerlessness he had felt as a kid; his underlying trouble, she explained, was a “spiritual malady.”

A year or so later, having gotten off drugs and alcohol and graduated from Columbia College, he pestered a managing director at Bank of America until the manager took a chance and hired him. At the end of his first year he was thrilled to receive a $40,000 bonus. But a week later a trader only four years his senior was hired away by another outfit for a salary of $900,000 – 22 times the size of his bonus – and he was at once consumed by envy, and then excited by how much money was available.

So it went. He worked hard, moved up the Wall Street ladder, became a bond and credit default swap trader (whatever that is). After four years in his new job Citibank offered him $1.75 million a year. At age 25 he reveled in money and power. But when, at a meeting, he suggested that the new hedge-fun regulations that everyone on Wall Street was decrying might be better for the system as a whole, the room went quiet and his boss shot him a withering look and said emphatically that he couldn’t think about the system as a whole, only about his company. At which point Polk began to view Wall Street with new eyes.

Now Polk noticed how traders hurled vitriol at the government for limiting their bonuses after the crash, and were infuriated by any mention of higher taxes. Having always envied the men who earned more than he did, he now began to be embarrassed for them and himself. Though he made more money in a single year than his mother, a nurse practitioner, had made in her whole life, he realized that, unlike her, he wasn’t really doing anything, wasn’t useful or necessary to society. And having foreseen the 2008 crash and made money off of it, he himself now didn’t like who he’d become. So he decided to get out.

Polk now realized that he was an addict, craving more money just as an alcoholic craves alcohol. And like any addict, he had an incredibly difficult time shaking his habit. All too often he woke up in the middle of the night terrified at the thought of running out of money, of later feeling like an idiot for giving up his one chance to be really important. In time these feelings abated, and he realized that he had enough money and, if he needed more, he could earn it. But just as a recovered alcoholic still craves alcohol, so he still at times craves money and buys a lottery ticket.

Avarice, an engraving by the Dutch artist Jacob Matham (1571-1631).

Avarice, an engraving by the Dutch artist Jacob Matham (1571-1631).Now Polk speaks in jails and juvenile detention centers about getting sober, teaches a writing class for girls in the foster system, and manages a nonprofit called Groceryships to help poor families struggling with obesity and food addiction. Which reminds me of a recovered alcoholic I once knew who enlisted in Alcoholics Anonymous to help other alcoholics get free of their addiction. Yet there is no 12-step program for wealth addicts. Why not? he asks. Because our culture supports and even praises the addiction. The superrich appear on the magazine covers at every newsstand, have become our cultural gods. So we all bear some responsibility, Polk insists, for letting wealth addicts exert so much influence over our nation. To which I would add the suggestion that, in a capitalist society, this is close to inevitable. We have always adulated wealth and those who have it.

Sam Polk’s article – well worth reading in its entirety – provides a clear and emphatic answer to the question posed earlier. Can greed become an addiction? Yes!

Coming soon: I haven't the slightest idea. I just hope it happens.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on October 26, 2014 05:12

October 19, 2014

149. Fulton J. Sheen and Norman Vincent Peale

A superb showman, he appeared on television before a live audience on Tuesday nights at 8:00 p.m. in full episcopal regalia: a long purple cape over a black cassock, and on his chest a gleaming gold cross. Of medium height and slender build, he had graying wavy hair, deep-set, penetrating eyes with a hypnotic gaze, and the look of an ascetic – albeit a sumptuously garbed ascetic. His rich, cultivated voice caressed, compelled. Looking right at the camera, with graceful arm gestures and quick changes of facial expression he spoke of good and evil, marriage problems, prayer as a dialogue, the holy spirit, the commandments, sin and penance, the sacraments, but in such a way as to appeal not just to Catholics but to a nationwide audience. The set was a study with a desk, chairs, and in the background, shelves of books, perhaps a reminder of his solid Catholic scholarship. At times he drew simple diagrams or wrote significant phrases on a blackboard, his only prop; if the blackboard was full, an unseen stagehand whom he called his “angel” would erase it, so it could receive more simple diagrams and significant phrases.

[image error]Archbishop Fulton John Sheen Spiritual Centre

The bishop’s stage presence and sensitivity to the audience’s mood were remarkable, and he was, to use a newly current word of the time, supremely telegenic. Competing with comedian Milton Berle, “Mr. Television,” whose program was on at the same time as his, the bishop’s program “Life Is Worth Living” had an audience of some thirty million a week. In 1952 his face appeared on the cover of Time magazine – itself a consecration – and the magazine proclaimed him “perhaps the most famous preacher in the U.S., certainly America’s best-known Roman Catholic priest, and the newest star of U.S. television.”

Such were the unexpected fame and success of the Most Reverend Fulton J. Sheen, Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of New York, in the 1950s. The number of stations carrying his program, which was filmed at the Adelphi Theater on West 54thStreet in New York, went from three to fifteen in less than two months. The demand for tickets for the show was too overwhelming to be met, and fan mail came pouring in at the rate of 8,500 letters a week. For instance:

A Massachusetts nurse: “I looked to my minister for advice, but because the matter was so personal I resisted asking him outright. Therefore I am writing to you….”

A South Dakota housewife: “I feel worried….”

A Philadelphia professional woman: “Last year it was made clear to me that my husband had an affair with a married woman…. Please use some theme which you think might bear on the remorse and regret which will follow if homes are wrecked by such relationships.”

He had a good sense of humor, used jokes and memorable one-liners:

“I see you’ve come to have your faith lifted.”

“An atheist is a man without visible means of support.”

“Long time no Sheen.”

Once, imitating his friendly rival Milton Berle, known to viewers as “Uncle Miltie,” he began, “Good evening, this is Uncle Fultie.” And he gave credit to his writers, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Though inspirational, he was fun as well.

Uncle Miltie and friends.

Uncle Miltie and friends.“Hearing nuns’ confessions,” he confessed, “is like being stoned to death with popcorn.” “The big print giveth,” he observed, “and the fine print taketh away.” And perhaps his Irish American background inspired the comment, “Baloney is flattery laid on so thick it cannot be true, and blarney is flattery so thin we love it.” Being famous and acclaimed, he probably got a good bit of both.

Born in 1895 to a farming family near Peoria, Illinois, he was Irish on both sides, showed an early preference for books over farm work, and was ordained a priest in 1919. Subsequently he earned a doctorate in philosophy at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, and claimed to have earned another doctorate in Rome, though this has been challenged; he may have invented it so as to speed up his advancement. Be that as it may, he had a solid foundation in Catholic philosophy and theology before beginning his career in media with a weekly radio broadcast in 1930. Time magazine in 1946 referred to him as “the golden-voiced Monsignor Fulton J. Sheen, U.S. Catholicism’s famed proselytizer,” but his real career and fame began in 1952, when Sheen, lately made a bishop, began his program “Life Is Worth Living” on television, the medium in which his splendor of presence could at last be fully conveyed to an audience. And conveyed it was, magnificently, to millions. Soon hailed as the first televangelist, he was unpaid, and the commercials were kept to a minimum.

Especially memorable was a program in February 1953 when Sheen, a fierce anti-Communist but no follower of Senator Joe McCarthy, denounced Stalin’s regime in Russia and gave a reading of the burial scene in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, substituting the names of the most prominent Soviet leaders, with Stalin as the murdered Caesar. “Stalin must one day meet his judgment,” he concluded. Stalin suffered a stroke a few days later and died on March 5, 1953.

It is no surprise, then, that FBI director J. Edgar Hoover admired Sheen and kept a file on him, since he liked to keep track of friends as well as enemies. On June 12, 1953, at Hoover’s invitation, the man who some thought had foretold the death of the villainous Stalin addressed the graduation exercises of the FBI National Academy in Washington, following which J. Edgar wrote him to say that his address was one of the most inspirational talks he had ever heard. And from the FBI files on the bishop we can glean an array of interesting tidbits:

· Sheen likes ice cream and angel food cake.· He likes to play tennis and wears a white scarf and white flannel trousers when doing so.· At a dinner for a group of men, when asked if he got all he wanted for Christmas, he said no, he wanted some royal blue silk pajamas. The next day he received twenty pairs of the same, each of the men thinking he was acting alone.· For years he drove a light cream-colored convertible, wearing a camel hair coat, a white scarf, and dark glasses while driving, so as to avoid being recognized. (His announced appearances were always mobbed by fans.) If stopped by a motorcycle cop for speeding, he used all his powers of oratory to avoid a ticket.· He lives simply in New York, rising at 6:00 a.m., attends a private Mass, isn’t at his desk before nine.

As these items suggest, Sheen didn’t live the life of a saint; he dressed fashionably, lived luxuriously, and enjoyed the attention he got in the media and the applause of adoring crowds. Humility was not his thing.

Even so, he brought Catholicism into mainstream television and was responsible for some remarkable conversions: author and Congresswoman Clare Booth Luce, Henry Ford II of the automobile dynasty, violinist Fritz Kreisler and his wife, actress Virginia Mayo, and ex-Communist turned anti-Communist Louis F. Budenz, whose conversion must have especially delighted him.

Less elegant than Sheen, but more

Less elegant than Sheen, but morepowerful. The bishop was said to be at times difficult, if his authority was challenged. Why his TV program ended in October 1957, when he was at the height of his television fame, was at the time something of a mystery. It seems that he tangled with another man who could also be difficult, if challenged: his superior, Cardinal Francis J. Spellman of New York. (For more on Spellman, see post #136.) In 1950 Sheen had become director of the New York-based Society for the Propagation of the Faith, and in 1957 he and Spellman engaged in a bitter feud. When Spellman demanded that the Society pay his archdiocese millions for a large quantity of powdered milk that Spellman had given the Society to distribute to the poor, Sheen flat-out refused.

When two colossal egos, one a powerful cardinal archbishop and the other a beloved and charismatic television star, collide, clerical sparks fly. Spellman took the issue all the way to Pope Pius XII, a personal friend, and a private audience resulted where he and Sheen pleaded their respective cases. To get the facts straight, the Pope phoned President Eisenhower, who confirmed Sheen’s account that the U.S. government had given the food to the Church free of charge. His Holiness then sided gently with Sheen, urging reconciliation and dismissing them while giving both men his blessing. Infuriated, the Cardinal reportedly told Sheen afterward, “I will get even with you. It may take six months or ten years, but everyone will know what you’re like.” Spellman quickly got Sheen’s television program canceled and saw to it that his speaking invitations declined and his fund-raising became more difficult. Sheen was, in effect, hounded out of the archdiocese

That was not the end of Fulton J. Sheen. He hosted another TV series in the 1960s, wrote numerous books, and became Bishop of Rochester in 1966, and when, at age 74, he resigned the position in 1969, he was made Archbishop of the Titutular See of Newport, Wales, a ceremonial post that let him devote his time to writing. In 1977 he underwent surgeries that weakened him and made preaching difficult, and two years later he died of heart disease in New York and was interred in the white marble crypt of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, in close proximity to his nemesis, Cardinal Spellman. Reruns of his programs are still aired, his talks are available on DVDs, and a museum bearing his name houses a collection of his personal items in Peoria, Illinois, where he was first ordained and said his first Mass. In 2002 Bishop Daniel Jenky of the Diocese of Peoria launched a campaign for his canonization.

But that is still not the end of the story. In 2010 the canonization campaign was suspended, owing to a disagreement between the Archdiocese of New York, which possesses Sheen’s remains, and the Diocese of Peoria, which wants the remains returned to Peoria, so they can be examined and relics secured, as required prior to beatification and canonization. In 2012 the Vatican announced that it had recognized Sheen’s life as one of “heroic virtue,” a significant step toward canonization; as a consequence, Sheen is now to be referred to as a “Venerable Servant of God.” For the canonization process to continue, two miracles are necessary, and one was soon forthcoming: a stillborn infant who, thanks to Sheen’s prayers, is said to have lived to be healthy.

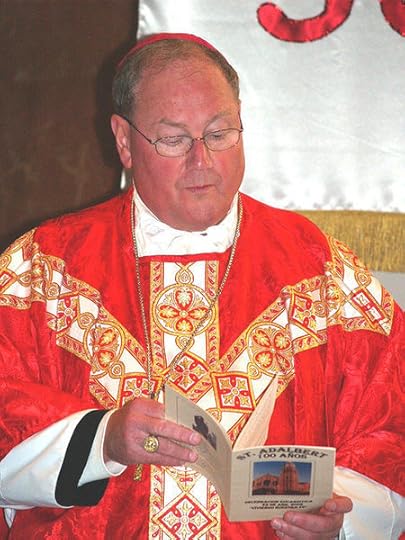

Meanwhile the fight continues. Peoria has drawn up blueprints for an elaborate shrine in its cathedral to house the tomb, but Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York refuses to part with the body, citing the wishes of Sheen’s family and Sheen himself, who spent only a few years in Peoria and many in New York, a city that he loved. Also, Sheen is a personal hero for Dolan, who knew the TV programs as a young boy. He has offered Peoria some bone fragments and other relics from the tomb, but not even a limb or two, much less the body itself. So last September Bishop Jenky announced “with immense sadness” that the campaign had been suspended yet again. There is lamentation in Peoria, but some Catholic observers applaud the delay, saying that canonization should not be rushed, that the old fifty-year rule should be restored, allowing time for a cult to grow organically and prove itself genuine or, in some cases, time for it to die out. And so matters stand to date. Meanwhile the archbishop has been inducted into the Irish American Hall of Fame, an award now proudly displayed in … Peoria.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who just can't let go.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who just can't let go.Cy White

Reliquary with a thorn

Reliquary with a thorn from Christ's crown of

thorns, in the Archbishop's

Museum in Cologne.

Raimond Spekking These events I have watched from afar, a Protestant pressing his stubby nose to a window – perhaps a stained-glass window – in amazement and disbelief at the goings-on within. Catholicism has always fascinated me, ever since, on my first trip to Europe long ago, I discovered the magnificent crumbling churches, always undergoing urgent repairs, with their marvelous statuary and windows, their flickering tapers, their venerable tombs and, displayed in glass cases, dimly visible bits of hair or bone, and once, on a trip to Mexico, the petrified heart of a bishop. These ancient remains, both architectural and human, have puzzled and mystified and intrigued me: this obsessed fixation on the physical is totally alien to Protestantism, yet essential to Catholicism and its cult of miracles.

Perhaps this fixation achieved the ultimate in the worship of the Holy Prepuce, which various churches in Europe have claimed to possess in the past, some even insisting it was a gift from Charlemagne. And if Jesus' foreskin is preserved and enshrined, why not some shorn locks (assuming he ever saw a barber) or some nail clippings? Where indeed does it end? (Incidentally, I have a number of Catholic friends quite firm in their faith, none of whom is concerned about relics.)

And the very idea of Sheen’s body being, as a compromise, divided between Peoria and New York – poor provincial Peoria, so often derided as the quintessential small Midwestern town, and huge, exciting, cosmopolitan New York – the very idea of it shocks and amuses and perplexes me.

Reliquary with the tooth of Saint Apollonia,

Reliquary with the tooth of Saint Apollonia,in the cathedral of Porto, Portugal. But there is a long history of dividing up sanctified remains. Saint Catherine of Siena’s body is enshrined in Rome, but Siena, allegedly after a bit of smuggling abetted by a miracle, has her head. (Legend has it that the people of Siena tried to sneak the head out of Rome in a bag. When the Roman guards inspected the bag, they found only rose petals, but back in Siena the head reappeared.) And Saint Francis Xavier’s body is in Goa, India, but his right forearm is enshrined in a reliquary in Rome.

Be that as it may, in the case of the Venerable Sheen I wish both dioceses well and hope the process of canonization can continue, so I can go on being shocked and mystified and fascinated, and the deceased archbishop can be properly and definitively entombed somewhere and venerated, bringing comfort and joy to many, as his presence on television did in life.

* * * *

Sheen was not without critics in his own time. He was called glib and superficial, an exponent of the “feel-good religion” of the time. “Americans like to feel good about themselves,” a young Russian acquaintance once said to me with a mischievous smirk, and I can’t deny the truth of his statement. We are an irrepressibly and incurably optimistic race, as witnessed by President Reagan’s cheery message, “It’s morning in America.” There is a whole industry devoted to making Americans feel good about themselves, and to make sure they do, there’s another industry devoted to their self-improvement. In 1923 the French psychologist Émile Coué toured the U.S., teaching audiences to recite, mantra-like, “Every day in every way I’m getting better and better.” In 1936 Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People was published and soon became a huge best seller still selling today, telling Americans that one could change how other people behave toward you by changing how you behave toward them. “Happiness doesn’t depend on any external conditions, it is governed by our mental attitude,” he asserted. To which he added, “Most of us have far more courage than we ever dreamed we possessed.” It cannot be denied that Sheen’s television program, “Life Is Worth Living,” for all its solid foundation in Catholic thinking, partook of this tradition. Which needn’t mean that it was glib and superficial, though it was certainly of its time.

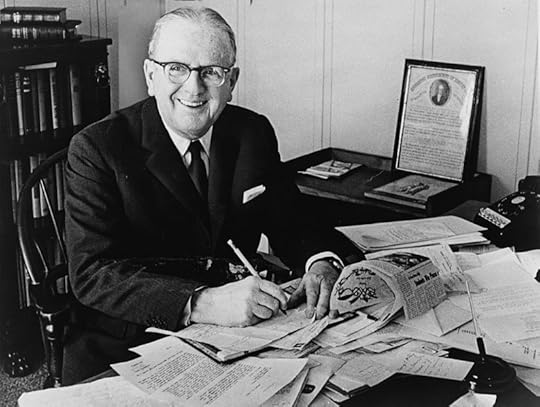

Also of its time and partaking of that tradition was Dr. Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking: A Practical Guide to Mastering the Problems of Everyday Living, published in 1952, whose introduction announced that “you do not need to be defeated by anything, that you can have peace of mind, improved health, and a never ceasing flow of energy.” The book stayed on the best seller list for 186 weeks, sold 5 million copies, and was translated into 15 languages.

No glamor, just a friendly smile. Born in Ohio in 1898 and ordained a Methodist minister in 1922, ten years later Peale switched to the Reformed Church in America so he could become pastor of the Marble Collegiate Church at 272 Fifth Avenue, on the corner of West 29th Street in Manhattan. (Protestants change sects as easily as they change a hat or a suit of clothes; for Catholics it’s a bit more complicated.) Walking down Fifth Avenue, many a time I passed the church’s marble façade, Romanesque with a dash of Gothic, and saw the reverend’s name emblazoned on a plaque, until one day his name was replaced by another. That would have been in 1984, when he ended his 52-year tenure as pastor, during which the membership grew from 600 to over 5,000, and he became one of the city’s most renowned preachers. He was also on radio for 54 years and later transitioned to television.

No glamor, just a friendly smile. Born in Ohio in 1898 and ordained a Methodist minister in 1922, ten years later Peale switched to the Reformed Church in America so he could become pastor of the Marble Collegiate Church at 272 Fifth Avenue, on the corner of West 29th Street in Manhattan. (Protestants change sects as easily as they change a hat or a suit of clothes; for Catholics it’s a bit more complicated.) Walking down Fifth Avenue, many a time I passed the church’s marble façade, Romanesque with a dash of Gothic, and saw the reverend’s name emblazoned on a plaque, until one day his name was replaced by another. That would have been in 1984, when he ended his 52-year tenure as pastor, during which the membership grew from 600 to over 5,000, and he became one of the city’s most renowned preachers. He was also on radio for 54 years and later transitioned to television.Here are some examples of Peale’s “applied religion”:

· Anybody can do just about anything with himself that he really wants to and makes up his mind to do. · Throw your heart over the fence and the rest will follow.· Don’t walk around with the world on your shoulders.· Believe it is possible to solve your problem. Tremendous things happen to the believer. So believe the answer will come. It will.· Start each day by affirming peaceful, contented and happy attitudes and your days will tend to be pleasant and successful.· Practice happy thinking every day. Cultivate the merry heart, develop the happiness habit, and life will become a continual feast.· It’s always too early to quit.· Fill your life with love. Scatter sunshine. Forget self, think of others.

For Peale, religion and psychology were fused to the point that you could hardly tell one from the other. His followers lapped it up, but not everyone was impressed. When I saw the 1964 film One Man’s Way, Hollywood’s version of his life to date, and his name was pronounced early in the story, there were groans throughout the theater; most of the audience had come for the other film being shown and had no idea what – or who – this one was about.

But there were serious criticisms of his book as well. Mental health experts didn’t hesitate to label him a con man and a fraud. The book was full of vague references to a “famous psychologist,” a “practicing physician,” and countless others, none of them identified. Critics called his understanding of the mind inaccurate, superficial, simplistic, false, and said his reliance on self-hypnosis was potentially dangerous. For him, they asserted, such unpleasant phenomena as murderous rage, suicidal despair, cruelty, lust, and greed don’t really exist; they are simply trivial mental processes that will evaporate if one’s thoughts become more cheerful. And on a lighter note, when Adlai Stevenson, running for the presidency in 1956, was told that Peale had endorsed the incumbent, Eisenhower, Stevenson replied, “Speaking as a Christian, I find the Apostle Paul appealing and the Apostle Peale appalling.”

These criticisms evidently stunned Peale, who later said he even considered resigning his post at the Marble Collegiate Church. What kept him there was the realization that, whatever his critics said, he was sure he was helping millions. On occasion he voiced a political opinion, as when he opposed the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960, insisting that Kennedy would serve the interests of the Catholic Church before those of the United States. This statement provoked condemnations by Harry Truman, the Board of Rabbis, and the leading Protestant theologians of the day, following which Peale seems to have gone into hiding and once again threatened to – but did not – resign from his church. (It’s always too early to quit.) After that he refrained from partisan political pronouncements. But did he ever read Dale Carnegie’s book?

When Richard Nixon was in the White House, Peale was persona most grata there and even officiated at the wedding of Julie Nixon and David Eisenhower. During the Watergate crisis that forced Nixon from office, he continued to frequent the White House, explaining that “Christ didn’t shy away from people in trouble.” One wonders if he told the besieged President to cultivate a merry heart, or advised him that it was always too early to quit.

Presidents simply couldn’t ignore the man, whether living or dead. In 1983 President Reagan awarded Peale the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the U.S., for his contributions to the field of theology (which must have been news to Protestant theologians of the time). And when Peale departed this earth in 1993 (scattering sunshine, one hopes), President Bill Clinton said that Peale’s name would always be associated “with the wondrously American values of optimism and service.” As regards optimism, who could argue?

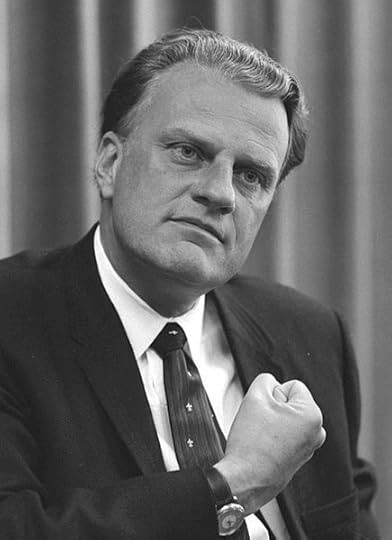

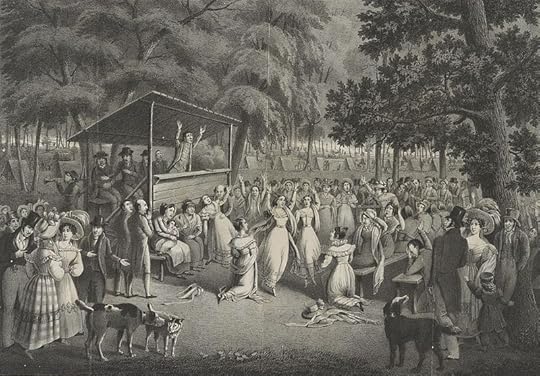

The 1950s are often dismissed as dull and conformist, when compared with the raging ’60s, but for spiritual sustenance they offered a range of options. For those not attuned to the splendor of Bishop Sheen’s Catholicism or the merry optimism of Dr. Peale’s Protestantism, there was always Billy Graham.

Square-jawed, and as clean-cut as they come.

Square-jawed, and as clean-cut as they come.A memorable Wednesday: At 1:00 a.m. I was wakened by a loud crash in the apartment. My flashlight revealed nothing out of order in the bedroom, but when I looked into the middle room I saw chaos. Four bookshelves attached to the wall had come loose and fallen down, heaping my partner Bob’s books on my computer, Bob’s wheelchair, and the floor. I have never seen such devastation in the apartment. Had I been sitting at my computer, I might well have received a concussion from the falling shelves. The books have now been removed to a bunch of cartons, and I shall see about restoring the shelves, which I installed when we moved in a mere 44 years ago. Bob has vowed to get rid of many books, which is music to my ears, since there are more shelves attached to a longer wall behind the computer, likewise installed 44 years ago. Nothing lasts forever.

Though neither of us had a full night’s sleep, I went to the Union Square greenmarket as usual, and there encountered the following:· A woman whose T-shirt proclaimed, GOD BELONGS IN MY CITY.· Little kids four feet tall with clipboards, making notes on what they experienced in the market.· A bearded drummer sitting shrouded in a long plastic bag, beating obsessively on a cardboard box and being photographed by tourists.· An Asian couple, each with a tiny infant suspended on their chest.· A six foot plus young black man being towed on a skateboard by his girlfriend.· An Asian and a Caucasian woman, surprised to see each other there and flashing smiles and greeting each other rapturously.· An older black woman in radiant blue, walking slowly, inch by inch, with a cane.· Little kids staring in wonder at pumpkins almost as big as they were.· A vendor at my organic bread stand whose T-shirt insisted, “Tibet sera libre.”· And a vast array of apples (maybe fifteen kinds), peaches, plums, root vegetables, a dozen kinds of winter squash, celeriac (“The frog prince of vegetables”), broccoli, kale, bison meat, cheeses, bread, preserves – you name it.

For a taste of the energy and diversity of New York, you can’t do better than the Union Square greenmarket.

Coming soon: Wall Street, greed, and addiction. And when a former president of the New York Stock Exchange pleaded guilty to grand larceny, what one offense did his colleagues find unforgivable?

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on October 19, 2014 04:51

October 12, 2014

148. Dorothy Norman and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Dorothy Norman, by Alfred Stieglitz.

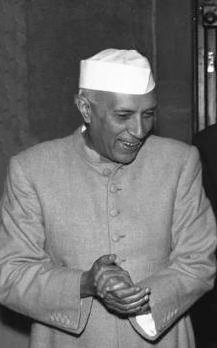

Dorothy Norman, by Alfred Stieglitz.Philadelphia Museum of Art Last week’s post was about Dorothy Norman, the woman who knew everyone, and her relationship with Alfred Stieglitz. This week’s post tells the story of her friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the prime minister of India. She had long been interested in Indian art and culture, had discussed Hinduism with the Ceylonese philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy, had advocated independence for India, and had come to know Madame Pandit, Nehru’s sister, who was India’s U.N. ambassador. Then, on October 11, 1949, two years after India achieved independence, Nehru himself came to the U.S., landing at Washington National Airport, where he and his sister, Madame Pandit, India’s U.N. ambassador, were received by President Truman. And when Nehru came to New York on the 15th, Dorothy Norman and her husband were among those who welcomed him at LaGuardia Airport and were briefly introduced; he struck her as elegant, handsome, bemused by the reception, radiant.

Nehru, Madame Pandit, and President Truman at Washington National Airport.

Nehru, Madame Pandit, and President Truman at Washington National Airport.At a reception at the Waldorf-Astoria that evening Nehru, now wearing Western clothes, seemed distant, yet unofficial, natural, and boyish. His baldness accentuated the noble cast of his face, with its high cheekbones and sharply sculptured nose; he had the bearing of a prince. Introduced again, she felt awkward, but her banal remarks provoked a smile from him, then laughter. Toward the end of the reception Madame Pandit asked her to remain after the others left, as her brother wished to speak to her. Nehru then explained, in his clipped British accent, that for a literary tea the following day the guest list included only familiar names and old fogies; could she include some younger, more progressive people? And if that was impossible, could she invite such people to a tea at her house the day after, when he would be available for no more than forty-five minutes, starting at 3:30 p.m.? His sister had assured him that she knew everyone, could arrange it. And would she please report to him at exactly 9:30 the following morning.

She admired his princely features,

She admired his princely features,his sharply sculptured nose.

Bundesarchiv This request astonished her. She had not been invited to the tea, whose hosts – author Pearl Buck and her husband – would resent her interference. She explained the awkwardness of her position, but Nehru and his sister reassured her: “Blame it on us. There will be no problem at all.” And since she knew Mayor O’Dwyer, could she ask him to cut the morning ceremonies the next day to a minimum? With that, he wished her good night, bowed, and joined the graceful, tapering fingers of both hands in an Indian salutation.

She was baffled, perplexed, and on the verge of laughter. But for this handsome, princely man she was determined to do what she could. Phoning Mayor O’Dwyer at 8:30 a.m. on October 16, she got him to shorten the ceremonies. A half hour later she phoned Pearl Buck, explained the situation, apologized; she and her husband agreed to add a few names, then invited her to the tea and asked her to help them take care of Nehru. She then phoned Nehru, who was grateful for the shortened ceremonies, though he would have to endure the traditional ticker-tape parade on Lower Broadway. Resigning himself to the tea, he repeated his request that she entertain him on the following afternoon. Who should she invite, and how many? “I leave everything to you.”

She and her husband were invited to most of the welcoming events of the day, but she managed to make out a list of guests for her reception and telegrammed invitations. Never before had she been asked to arrange and preside over a gathering if such significance, and on such short notice, but arrange it she did. The following afternoon the Norman living room on East 70th Street was crowded with writers, editors, publishers, intellectuals, and some of Nehru’s family and entourage. Nehru made no speech but answered questions. Cameras clicked, questions followed, and his answers often, to everyone’s surprise, provoked laughter. He stayed not forty-five minutes but an hour and a half, seemed relaxed and happy. When they saw him down to his limousine, he invited her to accompany him to Boston the next day. It would be her first flight and the thought of it terrified her, but she agreed.

She went on the plane with Madame Pandit and Nehru’s only daughter, Indira Gandhi (no relation to the Mahatma), a shy young woman burdened by her role as the prime minister’s daughter. Nehru had Norman sit next to him and they discussed Hinduism and Buddhism. In Boston, more ceremonies, more visits. Together they visited Boston’s two Indian spiritual centers, following which he said to her, “You should be glad, Dorothy, that we don’t have three spiritual centers in Boston.” Back in New York, he gave her a book of his, The Unity of India, drew her attention to a passage describing the beauty of Kashmir as resembling a supremely beautiful woman; their eyes met, and when his revealed a tenderness she hadn’t seen before, she burst into tears. Soon afterward, with his official visit to the city at an end, he left; she joined others at the airport to see him off.

Sukarno, a professed admirer of the U.S. That was hardly the end of the friendship. Nehru invited her to India for the January 1950 celebrations of the founding of the republic. With her children grown and her journal Twice a Year at an end, she was able to take a leave of absence from the New York Post and go. Arriving at Bombay airport, she was shocked by the two-thin dark bodies on the roads, and the contrast between street beggars and prosperous Indians in their fine cars. In New Delhi she stayed in the Prime Minister’s residence, attended by servants in sashes and turbans, and had breakfast and dinner daily with Nehru and his family. Ceremonies, vast crowds, pageantry. At a formal dinner she chatted with Nehru and President Sukarno of Indonesia, who told her of being raised on Whitman and Lincoln and announced with a superior air that, unlike the British-educated Nehru and other Indian leaders, he had been nurtured by the democratic American tradition. On one occasion Nehru, following behind his household, suddenly stopped and stood on his head. Those ahead of him didn't see it, but he cast an amused look at her to see if she had noticed. She had, their eyes met, and she forced herself not to laugh, while he walked on as if nothing had happened. Throughout her stay she accompanied Nehru on visits, talked with him, got to know his shy daughter Indira better. At times he looked at Norman with the eyes of a child; at times he seemed burdened, trapped in a cage, distant; at times he was relaxed, his charm devastating.

Sukarno, a professed admirer of the U.S. That was hardly the end of the friendship. Nehru invited her to India for the January 1950 celebrations of the founding of the republic. With her children grown and her journal Twice a Year at an end, she was able to take a leave of absence from the New York Post and go. Arriving at Bombay airport, she was shocked by the two-thin dark bodies on the roads, and the contrast between street beggars and prosperous Indians in their fine cars. In New Delhi she stayed in the Prime Minister’s residence, attended by servants in sashes and turbans, and had breakfast and dinner daily with Nehru and his family. Ceremonies, vast crowds, pageantry. At a formal dinner she chatted with Nehru and President Sukarno of Indonesia, who told her of being raised on Whitman and Lincoln and announced with a superior air that, unlike the British-educated Nehru and other Indian leaders, he had been nurtured by the democratic American tradition. On one occasion Nehru, following behind his household, suddenly stopped and stood on his head. Those ahead of him didn't see it, but he cast an amused look at her to see if she had noticed. She had, their eyes met, and she forced herself not to laugh, while he walked on as if nothing had happened. Throughout her stay she accompanied Nehru on visits, talked with him, got to know his shy daughter Indira better. At times he looked at Norman with the eyes of a child; at times he seemed burdened, trapped in a cage, distant; at times he was relaxed, his charm devastating. After a visit of three and a half months, she returned to New York, determined to lobby the government to send food to starving India. The amazing beauty of India, as well as its poverty, haunted her, but what haunted her most was the face of Nehru, its every feature and nuance. Yet when her husband greeted her at the airport, she was overjoyed. For all the wonder of India, she knew that he, her children, and New York were her reality; she still hoped their marriage would survive.

It didn’t. Edward became dictatorial, stern, forbidding, harsh with the children and her. His outbursts multiplied, followed by depression; she came to fear sudden violence on his part. Then, with the children grown, she urged him to find a more compatible woman and marry her; he tried, seemed to find one, but it didn’t work out. Though he pleaded with her not to, in 1953 she went to Reno and initiated divorce proceedings. After six weeks in Reno she obtained the divorce; both were heartsick.

And of course the inevitable question: Were she and Nehru lovers? The memoir certainly indicates a mutual attraction on their part, and the headstand antic, done expressly for her amusement, implies complicity. But to my knowledge she never acknowledged such an affair, and his life was so in view, with his relatives close at hand, and so relentlessly scheduled, that it is hard to imagine. Nehru, whose wife died in 1936, evidently had a protracted affair with Lady Mountbatten, the attractive wife of the last Viceroy of India. A photo of the Viceroy, his wife, and Nehru shows Lord Mountbatten, splendidly garbed in an immaculate white naval uniform, looking serious and official, while Nehru and Lady Mountbatten are convulsed with laughter over something that the Viceroy is unaware of or chooses to ignore. Certainly there was a bond between the Prime Minister and the Vicereine, embarrassing as it is today for the Indian government, so eager to preserve Nehru’s legendary status that it canceled a film being made in Delhi that would have told the story of the illustrious triangle. When Edwina Mountbatten died in 1960 and her body was given a sea burial off the coast of England, Nehru sent an Indian Navy frigate to cast a wreath into the waters on his behalf. So if her face didn’t launch a thousand ships like Helen of Troy, she at least launched one.

Lord and Lady Mountbatten with you-know-who. In his presence they were both

Lord and Lady Mountbatten with you-know-who. In his presence they were both on their best behavior.

But if Nehru and Dorothy Norman ever trysted and kept it secret, it was a miracle of amorous discretion. So perhaps their relationship was simply friendship. She had no official position, didn’t represent her country, didn’t criticize him for his nonaligned position in the Cold War, so in her presence he could be candid and relaxed, and even, as in the headstand stunt, a mischievous boy showing off for his girl. But his influence on her was deep, and in time she edited a collection of his writings, Nehru, the First Sixty Years, that was published in two volumes in 1965.

Dorothy Norman went on to more “encounters” – the artists Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich, the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson and his wife, others – and turned away from politics and social welfare concerns to develop a keen interest in myth and symbolism. Her memoir ends with a moving account of her mother telling her at last, and fervently, how much she loved her, and then dying in her arms.

Norman does not chronicle her later years, and the memoir, with a single exception, offers only photographs of her in her youth, several of them by Stieglitz. And afterward? She wrote, she edited, she gave her collection of Stieglitz photographs to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. As for her personal life, I know only what the in-house editor at Harcourt told me, how in her later years she surrounded herself with a circle of friends, all male homosexuals, among them the Japanese American artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi. (I have found no evidence online that Noguchi was gay, though his father was.) Once her youthful looks had faded, was this Norman’s refuge, among men who could offer, not romance or sex, but friendship? Even as she worked on her memoir, she told the editor it could never be published while Georgia O’Keeffe was alive. O’Keeffe died in 1986; the memoir was published in 1987 with a dedication “To Edward, my first love.” Dorothy Norman died in 1997 at age 92.

What is one to make of this woman who knew everyone? Limousine liberal, do-gooder, dilettante – she can be stuck with all these labels, but I think it would be unfair. She served the great – Stieglitz, Nehru, others -- without herself attaining greatness. She never worked a day in her life, in the sense of a salary-paying job, but she was constantly busy, never idle. A doer, she made things happen. What was it that let her bond so easily with others? Her beauty, her charm, her intelligence. And from that bonding came results: books, articles, exhibitions, food for a starving India, her biography of Stieglitz, her collection of Nehru’s writings, the Alfred Stieglitz Center in Philadelphia. And if her later turn toward myth and symbolism gets a bit vaporous and “New Agey,” that is probably the case with most Western followers of the great traditions, which for deep understanding require a focused lifelong commitment that few of us can offer.

Time and again Dorothy Norman was in just the right place at just the right time. When her friend the renowned photographer Edward Steichen was putting together a photographic exhibition, The Family of Man, to be presented at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955 -- an exhibition that would show the oneness of human hopes, fears, and preoccupations among all races, nations, and cultures throughout the world, and that would be the culmination of his career -- he found that the photos by themselves seemed lifeless, they needed captions; in desperation he appealed to her. Seeing a print of the first photo, showing a reflection of light on earth and water, she at once proposed a line from the opening of Genesis, “And God said, Let there be light.” Seeing another print of lovers in an intimate embrace, she suggested the closing lines of Joyce’s Ulysses, with Molly Bloom’s rapturous “Yes!” For other photos she drew on the Bible, Greek tragedy, Saint-John Perse, the Bhagavad Gita, other sources. When the exhibition opened, it was a great success, following which it toured the world for eight years and was seen by over nine million people. Decidedly, the right person in the right place at the right time. Her memoir too, evoking timeless myths, ends with an inspiring “Yes.”

Front page of the exhibition catalog.

Front page of the exhibition catalog.Dinales

Source note: The sources for this post are the same as those mentioned in the previous post: the 1977 interview and Norman’s Encounters: A Memoir (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987).

Are the Yahoos coming? I do not mean this blog to be political, but occasionally I feel compelled to voice an opinion. A New York Times article of September 29 reported that, among the Republican nominees likely to be elected to the House of Representatives in November, are some who have made these statements:

· Single parenthood should be reclassified as child abuse.· Four “blood moons” will herald world-changing events.· Islam is not a religion but a “complete geopolitical structure” unworthy of tax exemption.· Hillary Clinton is the Antichrist.· Equal-pay legislation should be opposed, because money is more important to men than to women.· Evolution is a lie from the pit of hell.

No further comment is necessary.

Coming soon: The bishop whose splendor of presence almost eclipsed comedian Milton Berle, who was known as Mr. Television. And to round things out, I’ll toss in merry optimism and the Power of Positive Thinking. Also: Peoria vs. New York or, Who will get the archiepiscopal remains?

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on October 12, 2014 04:28

October 5, 2014

147. Dorothy Norman and Alfred Stieglitz

She is 23, dark-haired, beautiful, with big brown eyes, and wants to know about art. He is 64 -- old enough to be her father and then some -- with deep-set, piercing eyes framed by glasses, his hair and mustache gray and bristling, and he knows all about art. She encounters him in a shabby little gallery on Park Avenue where he holds forth daily in a resonant voice, telling visitors that the world of our dreams is more real than the world that exists, and that art, like all love, is rooted in heartache. He makes the first satisfying statements about art she has ever heard and speaks with total conviction; she is entranced.

The young woman goes back to the little gallery again and again, listens to the man talk to others about art, learns his name, writes down afterward what he has said. The paintings shown there fascinate her, as does the man himself. Finally she speaks to him, talks with him about art. His words pour forth, don’t explain anything, but change something indefinable inside her. Though the paintings exhibited are available for purchase, he isn’t selling them, just talking about them, about art. He says the very things about art that she has been waiting to hear from someone knowledgeable and mature. Finally she writes him a breathless letter, says she can’t keep away from the gallery, loves what he is doing there, would like to help him do it. Answering her letter in bold black strokes of a pen that are almost chilling in their beauty, he tells her to feel free to come to the gallery and ask all the questions she likes. She does. She talks with him, looks at his photographs, feels his attraction like a great force of nature.

One day they find themselves alone in the gallery; a tense silence, as they look at each other intently.

“I want to say something to you,” she whispers.

“Say it,” he says. His voice is encouraging, but she holds back. “Say it.” “I can’t.”

“Say it.”

She makes a great effort. “I love you.”

His face softens. “I know – come here.”

He kisses her. Their lives are changed forever.

Dorothy Norman. Stieglitz encouraged

Dorothy Norman. Stieglitz encouragedher to become a photographer. She is Dorothy Norman, a young woman from an affluent Jewish family in Philadelphia who is now living in New York. He is Alfred Stieglitz, a renowned photographer and fervent advocate of contemporary American art. The year is 1928. She has met the man who, more than any other, will profoundly influence her life. There is just one problem: they are both married, but not to each other, and feel a loyalty to their respective spouses. And she has just given birth to her first child. So begins a long, fervent, but complicated relationship that could have happened only in New York.

Alfred Stieglitz, 1935.

Alfred Stieglitz, 1935.Born Dorothy Stecker to an affluent Jewish family in Philadelphia, she grew up surrounded by privileges that puzzled, then annoyed her. At a party in New York in 1924 she met Edward Norman, the son of a wealthy Sears Roebuck heir and they fell in love; overcoming opposition from both families, they married in 1925; she was 19, he was 25. On the wedding night he was dismayed, then angry, to learn that her parents had told her nothing about sex. When he entered her, she felt agonizing pain, bled, sobbed; in the morning, apologies on both sides, tenderness, assurances that all would be well.

They moved into an apartment on East 52ndStreet in New York, lived well but not lavishly, traveled abroad, became involved in progressive causes, advocated reform, not revolution. Though given at times to outbursts of anger, her husband was intelligent, knowledgeable, idealistic; she admired him greatly. She did volunteer work for the ACLU, visited art galleries and then, at the Intimate Gallery on Park Avenue, she met Alfred Stieglitz.

A strange but passionate relationship developed. Stieglitz was wise, informed, mature, yet possessed a youthful vigor and sense of fullness about life unlike anyone she had ever known. She didn’t see in him a father but a lover and mentor; they wrote, phoned, and saw each other daily, experienced physical love that she found breathtaking, almost frightening, in its intensity.

And the spouses? She still loved her husband, but in a different way, had no thought of divorcing him. They lived, vacationed, and traveled together, but the relationship must have been altered since he surely knew of her affair with Stieglitz almost from the start. How did he feel about a wife who, to be sexually and emotionally fulfilled, needed both a husband and a lover? Candid as her autobiography can be, of this she says almost nothing. She and Edward shared much, and yet …

Georgia O'Keeffe, circa 1920.

Georgia O'Keeffe, circa 1920.Stieglitz had good taste. As for Stieglitz, he was married to the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, 23 years his junior, and likewise had no thought of divorce. He had discovered her years before, a talented young artist who had yet to make a name for herself, and had divorced his first wife to marry her and promote her work. To judge from Dorothy Norman’s memoir, one might think that O’Keeffe and Stieglitz were by now estranged, but O’Keeffe’s biographer, Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, tells it differently: O’Keeffe was heartbroken by her husband’s open affair with Norman but endured it until 1933, when she suffered a nervous breakdown that hospitalized her for two months. After that there was indeed estrangement, as more and more she pursued her art in New Mexico, far from Stieglitz and Norman.

A personal note: I first heard of Dorothy Norman when, as a freelance editor in the early 1980s, I was hired by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich to edit the manuscript of her memoir, Encounters. I worked with an in-house editor from whom I learned certain things about Norman not mentioned in the memoir; I will introduce them when and if relevant.

With Stieglitz’s help, as well as her own beauty, intelligence, and charm, Dorothy Norman expanded her horizons and deepened her understanding of art. At a party she met the artist John Marin, whose work she particularly esteemed, and the sculptor Gaston Lachaise, and became good friends with both. She met Georgia O’Keeffe, a handsome woman strikingly dressed in black with a touch of white, though for obvious reasons the acquaintance could only go so far. In 1929, when Stieglitz learned that the Intimate Gallery must vacate the premises, she and O’Keefe and others helped finance a new and better gallery, An American Place, at 509 Madison Avenue. There Stieglitz, who disapproved of the recently founded Museum of Modern Art’s emphasis on “French Old Masters” (meaning Impressionists and Post-Impressionists), could continue to exhibit and promote American art. At his insistence the walls were painted white and gray and were unadorned, so as to convey an atmosphere of austerity, nor was it listed in the phone book. But right from the first – even in the wake of the Crash – people flocked to it.