Clifford Browder's Blog, page 46

June 8, 2014

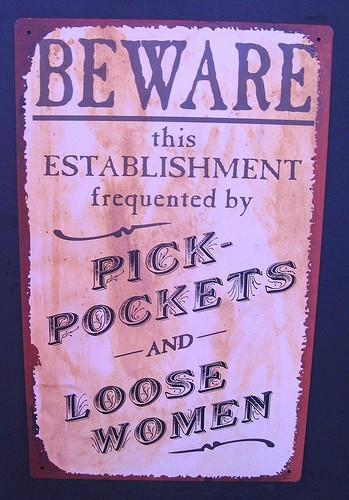

130. The Gentle Art of Pickpocketing: An Old New York Tradition

Pickpocketing is an old New York tradition. An urban phenomenon, it requires big crowds and lots of people with reams of cash, which aren’t to be found in quiet rural areas. It probably dates back to the very first cities. In his sonnet sequence Astrophel and Stella, Sir Philip Sidney declared, “I am no pick-purse of another’s wit,” which shows that the trade must have been flourishing in the streets of Elizabethan England. And the duc de Saint-Simon in his famous memoirs tells how Louis XIV, on horseback, saw a pickpocket emptying the pocket of the duc de Villars, one of the king’s greatest generals, at which point His Majesty rode up to the thief, hit him with his cane, and had him arrested; so even the royal presence did not deter this profession. In fact when, after much debate with his advisers, the king opened Versailles to the public, so as to dazzle his subjects and all the world, it meant opening the palace and its grounds to that same age-old profession. ATTENTION AUX PICKPOCKETS warn signs in Versailles even today.

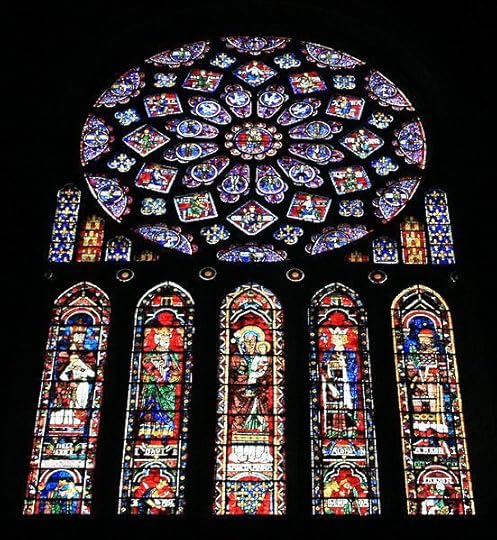

Pickpocketing is an old New York tradition. An urban phenomenon, it requires big crowds and lots of people with reams of cash, which aren’t to be found in quiet rural areas. It probably dates back to the very first cities. In his sonnet sequence Astrophel and Stella, Sir Philip Sidney declared, “I am no pick-purse of another’s wit,” which shows that the trade must have been flourishing in the streets of Elizabethan England. And the duc de Saint-Simon in his famous memoirs tells how Louis XIV, on horseback, saw a pickpocket emptying the pocket of the duc de Villars, one of the king’s greatest generals, at which point His Majesty rode up to the thief, hit him with his cane, and had him arrested; so even the royal presence did not deter this profession. In fact when, after much debate with his advisers, the king opened Versailles to the public, so as to dazzle his subjects and all the world, it meant opening the palace and its grounds to that same age-old profession. ATTENTION AUX PICKPOCKETS warn signs in Versailles even today. The Conjuror, by Hieronymus Bosch. But more than conjuring is going on here.

The Conjuror, by Hieronymus Bosch. But more than conjuring is going on here. Can you find the pickpocket?

So of course the gentle art has always been practiced in New York. In the years following the Civil War a host of Sunshine and Shadow books authored by journalists were published to satisfy the public’s appetite for information about the vast city on the Hudson, the Sunshine segment dealing with splendid buildings, parks, theaters, and the arts, while the Shadow segment dealt with crime and vice and corruption, including every kind of thievery.

These books catalog in detail what I call the Ladder of Thieves, a hierarchy acknowledged by the thieves themselves and rising from the ranks of the lowest to the highest. So let’s take a glance at the Ladder, before focusing on pickpockets. On the lowest rung were hat and coat and boot thieves, who took any loose object in sight; they were devoid of skill and ran few risks. Likewise the hog thieves, who grabbed a hog running loose on the street, tossed it in a cart, and dashed off. Those above these lowest of the low held them in the utmost scorn. (About those omnipresent hogs: they really did belong to someone, but the owners let them range freely about the streets so they could gat free eats gobbling up edible garbage.)

At the next level up were the pickpockets and shoplifters, whose trade required real skill, and above them the second-story sneaks who, while a family were all downstairs at dinner, scaled a pillar of the front stoop to enter a second-story window and help themselves to any valuables, jewels above all, to be found in the empty bedrooms.

On the next rung up were the bond thieves. Dressed respectably, a bond thief would pass through the railing in a broker’s crowded front office with a pen behind his ear and a paper in hand, and with a comment like “Permit me one moment” or “Excuse me, sir” would penetrate the back office with ease, the busy brokers thinking him one of their clerks. The intruder would then scoop up any cash, bags of coin, or negotiable bonds deposited on a desk or in a safe left carelessly open, and merrily depart. The chagrinned brokers often negotiated with the thief to get half the valuables back on condition that they not prosecute.

At the very top of the ladder were the safe busters, whose occupation required great daring and skill and much advance planning. Entering quietly at night, some blew the safe open, snatched the contents, and left within minutes. But subtler ones pried the safe open with special instruments, making no noise whatsoever. To these aristocrats of crime went the greatest spoils, and of course the envy and admiration of all the city’s other thieves, those denizens of the rungs below them.

The pickpockets had to learn their craft, were educated in schools by experienced professionals. They dressed well, had delicate hands with long, slender fingers. Pleasing in appearance and speech, they plied their trade in stages and horsecars, at crowded ferry docks and theater entrances, in churches, among throngs watching a parade or a fire or a street fight, or wherever crowds of people jostled together in confusion. The experienced pickpocket had a delicate touch, never searched for anything, knew exactly where the coveted object was and how to get it. He or she was observant, well aware that people entering or leaving a bank often feel their purse in a pocket, telling the thieves exactly what they needed to know. And their skill was such that they were rarely apprehended.

The female of the species might follow a lady into a shop, sit beside her, chat with her, waiting for the victim’s moment of distraction that would give the thief her opportunity. Or she might ride a Broadway stage, courteously ask a gentleman sitting next to her to raise or lower a window, and as he did so relieve him of his watch or wallet, thank him graciously, and promptly get off. But perhaps the crowning act of effrontery of a female thief was to attend a funeral all in black, veiled, perhaps weeping copious tears into a black silk handkerchief, so as to lift valuables from the mourners or even the dear departed. No doubt about it, the pickpockets of that era, male and female alike, were cunning, industrious, and daring.

A notorious New York pickpocket was Sophie Lyons (1848-1924), whose pedigree included a grandfather safe buster and a shoplifter mother who was also the “keeper of a disorderly house” on the East Side. Sophie’s first husband was a pickpocket who vanished into a state prison, following which she married a bank robber named Ned Lyons. A skilled pickpocket and consummate actress, if caught by a victim Sophie could register every shade of emotion and often persuaded the victim to let her go. Sent to Sing Sing in 1871, she was rescued the following year by Lyons, who got into the prison disguised and broke through the wall of her cell, following which they vacationed for a while in Paris, visiting their skills upon that cosmopolitan metropolis. Returning to New York, Sophie continued her colorful career, and in 1880 hauled her 14-year-old son George into court, requesting that he be sent to a juvenile facility because of his unruly behavior. A family shouting match followed, with George screaming that his mother was a thief and shoplifter who had two husbands and went all over the country stealing. The judge ruled that the son should be held in custody while the claims of mother and son could be investigated. How the matter was finally resolved is unclear, but one suspects that Sophie was not the ideal mother.

A notorious New York pickpocket was Sophie Lyons (1848-1924), whose pedigree included a grandfather safe buster and a shoplifter mother who was also the “keeper of a disorderly house” on the East Side. Sophie’s first husband was a pickpocket who vanished into a state prison, following which she married a bank robber named Ned Lyons. A skilled pickpocket and consummate actress, if caught by a victim Sophie could register every shade of emotion and often persuaded the victim to let her go. Sent to Sing Sing in 1871, she was rescued the following year by Lyons, who got into the prison disguised and broke through the wall of her cell, following which they vacationed for a while in Paris, visiting their skills upon that cosmopolitan metropolis. Returning to New York, Sophie continued her colorful career, and in 1880 hauled her 14-year-old son George into court, requesting that he be sent to a juvenile facility because of his unruly behavior. A family shouting match followed, with George screaming that his mother was a thief and shoplifter who had two husbands and went all over the country stealing. The judge ruled that the son should be held in custody while the claims of mother and son could be investigated. How the matter was finally resolved is unclear, but one suspects that Sophie was not the ideal mother.In 1913, at age 65, after many ups and downs in her career, Sophie Lyons retired from crime, wrote a memoir, Why Crime Does Not Pay, that was published, and became a philanthropist and prison reformer in Detroit. Honesty seems to have paid for her, since her real estate and business investments came to half a million dollars and she owned 40 houses. In 1922 she came home to find her house ransacked in her absence and bonds worth $7,000 and diamonds worth $13,000 missing. She died in Detroit in 1924.

Another pickpocket who achieved, for a while and at cost, considerable renown was George Appo (1858-1930), a street kid who slipped naturally into pickpocketing, and whose memoir has to date been published in part, with commentary. A pickpocket from an early age, he graduated into the green goods game, a swindle in which the victims paid good cash for a satchel of what they thought was counterfeit money, only to find, when they opened it later, sawdust or shredded paper or bricks. Those swindled could hardly complain to the police, being would-be circulators of counterfeit money, and the swindlers reveled in the thought that they had broken no law, since their operation involved no genuine counterfeit bills. And who were the victims? Appo chronicled Southerners embittered by the recent war and eager to defraud the federal government; debtors; farmers afraid of losing their farm; small businessmen trying to stave off bankruptcy; and even a black preacher from Florida who needed funds to build a church. Though aware of the game, the police did not interfere, since cheats were cheating cheats.

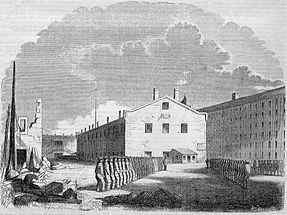

Another pickpocket who achieved, for a while and at cost, considerable renown was George Appo (1858-1930), a street kid who slipped naturally into pickpocketing, and whose memoir has to date been published in part, with commentary. A pickpocket from an early age, he graduated into the green goods game, a swindle in which the victims paid good cash for a satchel of what they thought was counterfeit money, only to find, when they opened it later, sawdust or shredded paper or bricks. Those swindled could hardly complain to the police, being would-be circulators of counterfeit money, and the swindlers reveled in the thought that they had broken no law, since their operation involved no genuine counterfeit bills. And who were the victims? Appo chronicled Southerners embittered by the recent war and eager to defraud the federal government; debtors; farmers afraid of losing their farm; small businessmen trying to stave off bankruptcy; and even a black preacher from Florida who needed funds to build a church. Though aware of the game, the police did not interfere, since cheats were cheating cheats.Less lucky than most pickpockets, in the course of his eventful career Appo achieved intimate familiarity with the Tombs, the penitentiary on Blackwell’s (now Roosevelt) Island, and the notorious state prison of Sing Sing, whose lockstep and rule of silence he detested, and whose torture in the form of the Paddle he has vividly described: a naked inmate was fastened to a board and beaten with a perforated paddle whose holes acted like suckers and raised blisters on his flesh, or even tore parts of his flesh off, following which he might be sent back to work or, if in a state of collapse, confined to the “Dungeon,” a tiny, dark cell where his only companion was a slop bucket.

Sing Sing in 1855, showing the lockstep that Appo so hated.

Sing Sing in 1855, showing the lockstep that Appo so hated.Fame came to Appo in 1894 when, eager to leave the crooked life, he appeared before a state senate committee investigating police corruption in New York City, where his testimony created a sensation. Further fame came later that same year when he appeared in a melodrama about crime, playing himself in one short scene, and his name was plastered on billboards all over the city. Here, long before the reality shows of TV today, fact and fantasy met, just as in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which for a season featured Sitting Bull and his braves, the future nemesis of Custer. But Appo was brutally wrenched back into the totally real when the police, angered by his testimony, assaulted him and framed him, and his lawyer, to preserve him from further retaliation in prison, had him declared insane and lodged for a while in a state hospital for the criminally insane, from which he was finally discharged in 1899. In his later years he lectured merchants about street crime, worked as an undercover agent for the Society for the Prevention of Crime, and started writing his autobiography. Having survived more than a dozen physical assaults, including bullets in the stomach and head, and scars from a knife attack on his throat, he died of old age in 1930.

Everyone needs a break from their work, and the New York thieves were no exception. Their balls were often held in a Fourth Ward dive kept by an old housebreaker, the proceeds going to hire a lawyer for a comrade who had been arrested. Thieves of every level attended, the distinctions between them momentarily forgotten. To the screechy music of a fiddle and a banjo, such luminosities of crime as Mother Roach and Big Nose Bunker might be seen cavorting together, or Scotch Jimmy with Wild Maggy, or Baboon Connelly with Sugar Nell, in a rapid succession of Virginia reels and round dances that toward the end of the evening achieved a climactic frenzy.

Now let’s fast-forward to the twentieth century. Was the trade flourishing in these more modern times? You bet. Pickpocketing was still a profession for which one had to be trained. A veteran thief would train five initiates who would then go on to acquire experience and each in turn train five more, and so the occupation continued. Initiates needed a steady hand, patience, and a light touch. One has told of entering one such school in 1969 and finding a room filled with half-dressed mannequins. A bell was installed on each mannequin, and the trainees had to lift a wallet without ringing it. As the teacher said, “You have to be a pianist.” The pickpocket who told this story worked the city streets in a suit or casual clothes and on a good day pulled in $2,000. He took great pride in lifting wallets from women in the revolving door at Macy’s; the victim would go on into the store, while he would exit onto the street and hail a taxi.

This would seem to indicate that pickpocketing is alive and well in New York City today, but in the twenty-first century this is not the case. Pickpocketing is, in fact, a dying art. If there were 23,000 cases of pickpocketing in the city in 1990, by 1995 the number had fallen by half, and by the year 2000 it was under 5,000. What accounts for this? The proliferation of surveillance cameras; longer sentences; among younger would-be thieves, a lack of the patience required, and a preference for robbing at gunpoint; and above all the widespread use of debit and credit cards, so that people carry much less cash on their person. Result: the old apprenticeship system has withered away.

Watch out for those sly geezers.

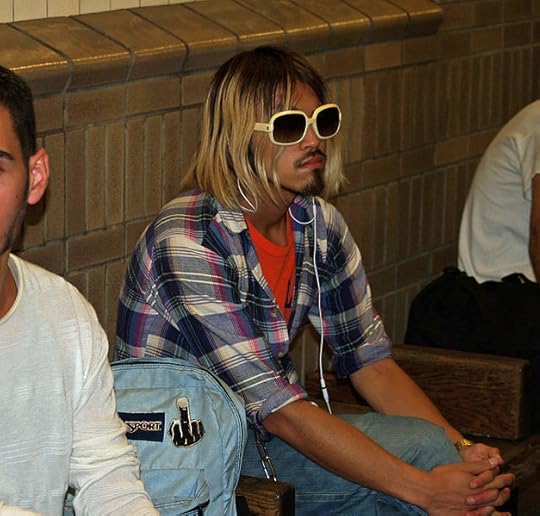

Watch out for those sly geezers.Not that pickpockets have vanished completely. There are still occasional reports: a woman in Queens whose purse was taken by a young man while two confederates chatted with her about her baby; a woman robbed in the East Village by a suspect whom a bank surveillance camera revealed to be a harmless-looking young woman in “hipster” glasses who, having swiped a wallet, then uses the ATM card in it to drain the victim’s bank account; a proliferation of pickpockets flocking to crowded stores in downtown Flushing, where the business community is working with the police to fight the invaders; and middle-aged male pickpockets of the old school who work the subways, using razor blades to deftly cut pockets and remove money and mobile phones without so much as scratching the victim, one thief being 80 years old, and some with over 30 arrests on their record. “Surgeons with a razor blade,” the police have termed this latter group with grudging admiration, while numbering them, as of November 2011, at exactly 109.

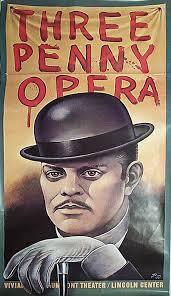

A pickpocket with a difference is Pierre Ginet, a Frenchman who gave up his law studies at the Sorbonne for sleight-of-hand performances. A veteran of the Cirque du Soleil, in 2013 he performed at the Big Apple Circus at Times Square, where he invited circusgoers onto the stage and robbed them while the crowd looked on. His preferred targets were men with a jacket, preferably with glasses or a tie as well, and with facial hair, since the hirsute are, in his opinion, more fragile. He sees the tourist crowds in Times Square, their wallets stuffed with money and their bags with valuables, as especially vulnerable, all the more so since their attention is focused elsewhere. And subway straphangers are a pickpocket’s dream, since they hold on to the high bars and thus leave their jackets hanging open and their bags exposed. So watch out, commuters. M. Ginet always returns what he steals, but other practitioners might not be so considerate.

Quite apart from magicians, the art of pickpocketing is in decline, but it still makes sense to be wary in crowds and keep your valuables deep in inside pockets. Not for nothing do the greenmarkets mount signs BEWARE OF PICKPOCKETS, but in noticing such signs avoid the instinctive gesture of patting your wallet reassuringly, since that tells pickpockets just what they need to know. And above all don’t pass out drunk or fall asleep while seated in the subway; you may wake up minus your wallet and five stops past your station – it happens all the time.

Source note: Selections from George Appo’s autobiography, accompanied by commentary, appear in Timothy J. Gilfoyle’s A Pickpocket’s Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York (2006). It is well worth a read.

Monsanto: Followers of this blog know that Monsanto is the company I love to hate. And I am not alone: on Saturday, May 24, there was a global demonstration against Monsanto in over 400 countries, with some 2 million people attending worldwide. Demonstrators called for a permanent boycott of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), food transparency (foods with GMOs to be labeled), and a transition to local, organic, and sustainable agriculture. In the U.S. there were demonstrations in 47 states; in New York, protesters marched from Union Square to Brooklyn. GMOs are now at least partially banned in many countries, though not – of course – in the U.S., where Monsanto people hold important positions in government. And what did the New York Times say of all this? To my knowledge, nothing. And WNYC, our local NPR station? Again to my knowledge, nothing. For them, I guess, this wasn’t worth reporting.

Demonstrators in Vancouver.

Demonstrators in Vancouver.Rosalee Yagihara

This is New York

InSapphoWeTrust

InSapphoWeTrustComing soon: Remarkable Women: Ayn Rand. Her books are still read today. Why?

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on June 08, 2014 04:30

June 1, 2014

129. Ethnic New York: Tibetans, Afghans, Mohawks

Here now are some more interesting ethnic groups to be found in and around New York. But for an unusual twist, I’ll begin by mentioning Gamal, who delivers take-out to us from a nearby restaurant. Though his English is quite good, I knew he was from Uzbekistan, but when I questioned him further, he explained that he was not an Uzbek but a Tatar, and graduated from the University of Tashkent. Tashkent … Uzbekistan … Tatar … These words speak to my uninformed Western mind, conjuring up visions of long westbound caravans on the Silk Road, the endless steppes of Central Asia, mysterious nomadic peoples, Genghis Khan and the Golden Horde. But Gamal presents a modern-day reality. He and his family came here a few years ago for better opportunities, and to get free of the corruption prevalent in Uzbekistan. Here they have launched a business supplying provisions to restaurants, and it is expanding now across several boroughs. Gamal delivers take-out in his spare time simply to earn a little extra cash. When he comes to us he invariably flashes the warmest smile and gives us the heartiest of greetings. But we may lose him, for he and his family may in time move to Boston because of the lower rents and shorter commutes there. But for now we are fortunate to enjoy the services of this friendly Tatar from Uzbekistan, the embodiment of the city’s ethnic diversity.

Tibetans

The Jackson Heights section of Queens is one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in New York. 74th Street between Roosevelt Avenue and 37th Avenue is the heart of Little India, where Indians and other South Asians have predominated, though more recently Latin Americans have settled there, too. Women in saris are seen on the streets with their children, retailers offer Indian music and Bollywood films, and Indian restaurants abound, but among the Indian jewelry and sari shops and Ecuadorean bakeries one often sees strings of brightly colored cloth rectangles fluttering in the breeze, and pictures of some revered figure. The rectangles are the prayer flags inscribed with symbols, mantras, and prayers that Tibetans install in front of their residence or place of spiritual practice so that, fluttering in the breeze, they can bring happiness, long life, and prosperity to the residents and neighbors. And the pictures are of His Holiness, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. For here in the midst of Little India is what amounts to a Little Tibet.

Tibetan prayer flags.

Tibetan prayer flags.Dennis Jarvis

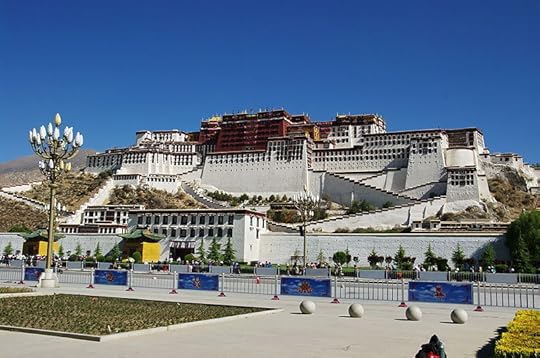

Tibet: a remote and mysterious land that Westerners have always thought of as the rooftop of the world, bordered by the towering snow-capped Himalayas, with Buddhist monasteries, shaggy beasts called yaks, a vast hilltop palace in Lhasa, the capital, and a culture going back thousands of years. The spiritual leader of Tibet, the much revered Dalai Lama, is believed to be the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama, and is found after the high lamas seeking him receive a vision in a sacred lake that guides them to one or several boys who must then pass a series of tests until the future Dalai Lama is found. This can take years – four in the case of the present Dalai Lama.

A yak.

A yak.Dennis Jarvis

The palace in Lhasa.

The palace in Lhasa.Balou46

Our view of this legendary land changed forever once the Communist Chinese took control of the country in 1950 and in 1959 crushed a Tibetan uprising, causing the Dalai Lama to flee over the towering Himalayas to India, soon followed by some 80,000 Tibetans. Granted sanctuary by the Indian government, the Dalai Lama established a government in exile, and every year more Tibetans emigrated to India, Nepal, or Bhutan, and small numbers of them began migrating from these countries to the West. By 1985 there were 524 Tibetans in the U.S. Then a section of the Immigration Act of 1990 authorized the issuing of a thousand immigrant visas to Tibetans living in Nepal and India, following which there has been a steady immigration to these shores.

There are now at least 10,000 Tibetans here, probably more, with about 4,000 in New York City, the largest Tibetan community in the U.S., mostly concentrated in Queens. Some came from India, Nepal, or Bhutan, but others were born here and have never set foot in the mysterious land of their family’s origin. But they feel welcome here, where the plight of Chinese-dominated Tibet arouses much interest and sympathy. And they can become citizens, whereas in India and Nepal they have only refugee status, with few rights as citizens. But many hope to earn enough money here so they can move on to Minnesota or Wisconsin, where there are large Tibetan communities and a less stressful environment for raising a family.

Many Tibetans here are undocumented, so the women work as nannies, housekeepers, and caregivers for the elderly, and are much in demand, having a reputation for being patient, diligent, soft-spoken, and caring. The men find work as interpreters or translators, or drive cabs or sell produce in greenmarkets or become construction workers, but some work in – O irony! – Chinese restaurants. Inevitably, many older Tibetans don’t know English and find it hard to adjust to American life. They may ride the subway a short distance to attend a Tibetan prayer session, but otherwise they depend on family for social life, and if that is limited because their relatives are away at work, their life here can be bleak: prayers at home and maybe a very short walk to a park.

Since many Tibetans came here from India, they feel comfortable in the Little India section of Jackson heights, where restaurants like the Himalayan Yak Restaurant on Roosevelt Avenue offer authentic Tibetan and Nepalese food, including the Tibetan dumplings known as momos, and noodles, soups, and sausage, as well as a Tibetan tea with yak butter and salt; being modern as well as traditional, the Yak Restaurant even has a blog. The yak meat offered in these restaurants is said to be juicier than beef and so delicious that one taste of it may lead to addiction. But in this country until recently yaks existed only in crossword puzzles, so where does yak meat come from? From Colorado and Wyoming and Idaho, where yaks are now being raised by American ranchers eager to accommodate a profitable and growing niche market.

Unlike many immigrant ethnic groups here, the Tibetans are highly political. Students for a Free Tibet was organized here in New York in 1994 to campaign for human rights and independence in Tibet. Whenever there is unrest or riots in Tibet, in fair or foul weather they and other groups picket the Chinese consulate at 520 Twelfth Avenue daily, even to the point of being fined for missing work. “This is not politics,” a young Tibetan insisted once, “this is human rights. I am for the rights of others as well as mine.” In 2012 three Tibetans staged a one-month hunger strike outside the U.N. building to demand that the U.N. establish a fact-finding delegation to assess the situation in Tibet. And they are organized, with a worldwide network. In New York alone there are at least five very active groups, all advocating for Tibetan interests and concerns, including a Free Tibet movement that, following the teachings of the Dalai Lama, is nonviolent. But the protesters are not immune to frustration and anger; during one protest in 2008 one of them shattered a window in the consulate.

[image error]A Students for a Free Tibet demonstration.

Medill DC

His Holiness, toes and all.

His Holiness, toes and all.Luca Galuzzi The Dalai Lama has often come to New York to give teachings on various aspects of Buddhism and to address huge gatherings of the general public. Spiritual and inspiring he certainly is, but he also has a sense of humor. I once heard him in a radio interview announce that there would be a discussion and lots of “blah, blah, blah.” He seems adept at managing a fine balance between taking himself very seriously and having a quiet chuckle at his own expense.

But His Holiness is aging; after he is gone, the Free Tibet movement, given the intransigence of the Chinese Communists, may find it hard to remain nonviolent. Nor is it clear how the next Dalai Lama will be chosen; the Chinese authorities are bound to try to manipulate the process to their own advantage. Be that as it may, even Tibetans born here feel a loyalty to the homeland they have never seen. Most become U.S. citizens, but deep inside they remain Tibetan. Some keep an altar in their apartment where they light incense and offer water daily to statues or pictures of various buddhas and gurus, but others insist that spirituality is cultivated internally and requires no outward observances. Being greatly concerned lest their children growing up here become too Americanized, they take pains to instruct them in Tibetan culture and have them learn the Tibetan language.

Afghans

One woman in Flushing, Queens, whose grandson is a doctoral candidate at the New School, tells how the FBI raided her home, rummaging through her closets while ignoring her protests that she had lived here for 25 years. Who called the FBI in? The intruders wouldn’t say, but she’s sure it was a downstairs neighbor. And the owner of a restaurant claims that he can spot the FBI on sight, and they him: “Yeah, we all know each other.” All this, of course, after 9/11. Such is the troubled life of the Afghan community in New York.

Afghanistan is a landlocked, mountainous country in Central Asia, historically almost as remote as Tibet, with towering snow-covered peaks, arid plains, and sandy or stony deserts. It is an impoverished and underdeveloped country with a hodgepodge of peoples and languages, and a harsh climate: a land ravaged in recent times by war and civil strife, terrorism, and a flourishing opium trade that defies all efforts to eradicate it. Clearly, a land that many might want to leave. Afghans may have started coming here as early as the 1920s. More came in the 1930s and 1940s, most of them educated and some with scholarships to study in American universities. Afghan immigration increased after the 1979 Soviet invasion, when asylum passports were granted freely by the U.S. government, and increased again after the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 1996, and yet again after the U.S. bombing began in 2001.

Unlike their predecessors, these later immigrants came not enamored of the dream of America, but out of sheer necessity, with little knowledge of English or of American society, and sometimes even illiterate in their own language. Though glad to be here, they were – and are -- strangers in an alien land, with the largest communities in California and the Northeast. Most are Sunni Muslims, but ethnically they may be Pashtun (the majority), Tajik, Uzbek, Hazara, Aimaq, Turkmen, Baloch, or various other ethnicities, including even a few Jews.

Today there are at least 9,000 Afghans – some sources say as many as 20,000 – in the New York City area, most of them in various locations in Queens, with the biggest concentration in Flushing. Here in Manhattan, without knowing them as Afghans, we encounter the men as cab drivers, restaurant workers, and coffee and bagel cart vendors. Many of the women are stay-at-home mothers with little exposure to American society, but others take jobs below their former status in Afghanistan and work as housekeepers or babysitters.

Soon after 9/11 a Tajik imam, the spiritual leader of a mosque in Flushing, accused the mosque’s Pashtun founders of supporting the Taliban and expelled them from the premises. The founders accused the imam in turn of inventing these charges so as to gain control of the mosque, sued, and regained control of the mosque by court order, following which the imam and his Tajik followers were forced to leave. Which goes to show the internal divisions that also afflict the Afghan community in New York.

When the U.S. intervened militarily in Afghanistan, some local Afghans were angry, feeling that Saudi Arabia, not Afghanistan, should be blamed for 9/11, since most of the hijackers were Saudis. But others celebrated the intervention, convinced that a defeat of the Taliban would be a blessing. Yet all of them are leery of FBI surveillance and aware of being suspect in the eyes of fellow New Yorkers, who have shouted “Terrorist!” at them only too frequently and called them a wild, barbaric people.

On September 14, 2009, with a visit to the city by the President coincidentally imminent, armed federal agents raided three apartments in Flushing at gunpoint, breaking in by force in the middle of the night to rummage through closets, drawers, and even purses, searching for explosive devices or their components that were allegedly to be used on targets in the New York area. No such devices were found, though the police removed computers, cellphones, and other material; the men detained were interrogated and then released. The whole neighborhood was upset, and those targeted, a cab driver and two pushcart vendors among them, protested their innocence, insisting that they worked hard six or seven days a week and had no time for, or interest in, politics.

Najibullah Zazi But the alleged plot was not mere fantasy. Those targeted had been visited recently by a casual acquaintance, Najibullah Zazi, who was soon arrested in Denver for planning suicide bombings in the New York subway system ordered by al-Qaeda; later he pled guilty and agreed to testify against his fellow conspirators. Because surveillance had revealed the plot, his case has been cited by the Obama administration to justify massive government monitoring of phone calls and e-mails. And the Afghan community in New York, even as it adjusts to American ways, continues to feel alien and besieged.

Najibullah Zazi But the alleged plot was not mere fantasy. Those targeted had been visited recently by a casual acquaintance, Najibullah Zazi, who was soon arrested in Denver for planning suicide bombings in the New York subway system ordered by al-Qaeda; later he pled guilty and agreed to testify against his fellow conspirators. Because surveillance had revealed the plot, his case has been cited by the Obama administration to justify massive government monitoring of phone calls and e-mails. And the Afghan community in New York, even as it adjusts to American ways, continues to feel alien and besieged.But change is coming. In traditional Afghan society, where family and tribal bonds are strong, and the sense of family honor fierce, most women wear headscarves and show no flesh below the neck, and must not make eye contact with a man in public. As for education, they have little or none, marry early as the family dictates, and are subservient to their husband for the rest of their life. These restrictions have been loosened to some extent in recent years, but still prevail.

Afghan women in a market.

Afghan women in a market.Imagine, then, the shock when a traditionally raised Afghan woman finds herself planted in American society, where no such rules apply. Yes, she is in a tight-knit Afghan community, but circumstances may force her to take a job outside. The contrast between the traditional life she has known and what she sees all around her is overwhelming. And yet, Afghan women are said to adjust even better than the men. They do find jobs outside the home, and they do want education.

Answering that need locally is Women for Afghan Women (WAW), a Queens-based human rights organization founded in April 2001, six months before 9/11, that advocates here and in Kabul for the rights of Afghan women. Funded by government and nongovernment agencies and private donations, it helps women here with immigration issues, parenting, family matters, and domestic violence. A Women’s Circle holds popular monthly meetings with lectures and discussions, and a chance for women to share experiences and provide mutual support. There is also a girls’ leadership program, and free classes in English, computer skills, driving, and applying for U.S. citizenship.

As for the organization’s work in Kabul, one story sums it all up. A girl named Somaya grew up in Herat, Afghanistan. Her father had two wives and abused her mother. One day, at age nine, she came home to find her mother in a pool of blood; her father had stabbed and killed her. The father went to prison, but Somaya’s stepbrothers tried to force her to marry a rich older man in exchange for a large dowry; when she refused, they beat her and locked her in a darkened room. Finally, when she was allowed to go home with her uncle for a brief stay, she went back to school and told her teacher everything. The teacher got the stepbrothers arrested, and arranged for Somaya to stay in a women’s shelter. Finally she was transferred to Women for Afghan Women’s halfway house in Kabul, where she was able to return to school. She dreams of becoming a lawyer so she can work for the rights of women.

Against the background of Afghan history and the role of women in traditional Muslim societies, Women for Afghan Women’s program is nothing short of revolutionary. Even today, in regions where Muslim extremists prevail, a girl or young woman who wants education risks kidnapping, acid in the face, or death. What do the extremists most fear? Drone strikes? No. Boots on the ground? No again. Free elections? Not even this. It's the education of women. An educated woman, even if she remains a good Muslim, is lost to them; she will begin to think and act for herself. She threatens all the repressive aspects of her traditional society; she is a symbol of hope for others. The extremists must eliminate her, or their own cause will in the long run be doomed. This conflict is under way now in Afghanistan and other Muslim countries; there is evidence of it in the news almost daily.

But even here in New York there are risks for the educated Afghan woman. Sometimes these young women seem too Westernized to be suitable mates for Afghan men, who prefer to find wives among communities still living in Afghanistan or Pakistan. Progress is slow and uneven; often it is three steps forward, two steps back. But it doesn’t stop, it continues. And it continues right here in New York.

Mohawks

There are many other immigrant groups in and around New York City that I could mention: Turks, Armenians, Ukrainians, Koreans, Croatians, Thai – the list is endless. Instead, I’ll end with a very special group who have contributed hugely to the city’s skyline, helping make it what it is today: the Mohawks. They aren’t immigrants at all, of course, since they were here long before the rest of us; by comparison, we are the immigrants.

Some of them once lived with their families in Brooklyn, but most of the two hundred working here now live during the week in boarding houses or apartments or motels scattered across the metropolitan region, and then on Friday afternoon begin the six-hour drive 400 miles north to the Kahnawake reserve on the south bank of the Saint Lawrence River about 20 miles from Montreal, to spend the weekend with their families. Then on Sunday night they begin the long trip back to New York, arriving at the job site just in time for work.

It all began in 1886, when the Canadian Pacific Railroad wanted to build a bridge over the Saint Lawrence River, one end of which would be on their property, and agreed to hire tribesmen. The railroad meant to use them simply to unload supplies, but at every chance they got, the young Mohawks would go out on the bridge and climb up high. Seeing that the Mohawks seemed to have no fear of heights, and needing riveters for dangerous work high up, the railroad began training them, and they worked on many jobs in Canada. Then in 1907, when the collapse of another bridge under construction killed 33 Mohawks, the Mohawk women insisted that, rather than all working on the same site, their men work in smaller groups on a variety of projects. So they began coming to New York, where such projects were plentiful. And thus a people with age-old traditions centered in the earth left that earth far behind to work here in high steel.

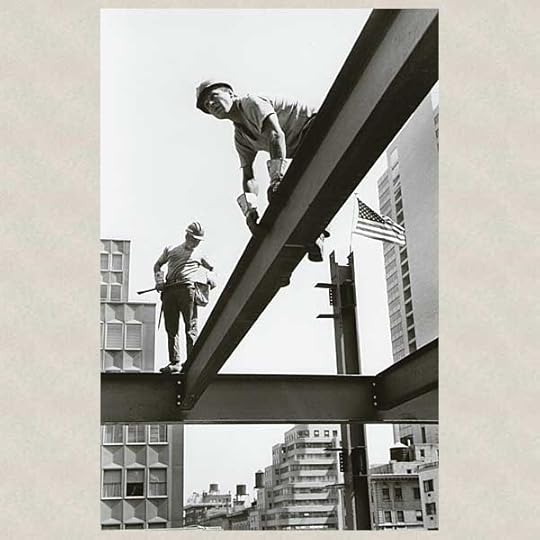

© 2014 David Grant Noble The Mohawks weren’t the only workers in high steel; many European immigrants worked there, too. But the fathers, grandfathers, and even great-grandfathers of today’s Mohawk workers guided bars of steel into the skeletons of the city’s skyscrapers and bridges, and now a fourth generation is helping rebuild the World Trade Center site. On 9/11 Mohawks working on other projects flocked to the Twin Towers to help people escape from the flaming buildings, and when the towers came crashing down, they helped look for victims and, over the months that followed, worked in the cleanup of what some of them had helped build years before. Recently they worked frantically to make One World Trade Center rise by one floor every week; scheduled to open in 2014, the 104-story structure is the tallest in the Western Hemisphere, and the fourth tallest in the world.

© 2014 David Grant Noble The Mohawks weren’t the only workers in high steel; many European immigrants worked there, too. But the fathers, grandfathers, and even great-grandfathers of today’s Mohawk workers guided bars of steel into the skeletons of the city’s skyscrapers and bridges, and now a fourth generation is helping rebuild the World Trade Center site. On 9/11 Mohawks working on other projects flocked to the Twin Towers to help people escape from the flaming buildings, and when the towers came crashing down, they helped look for victims and, over the months that followed, worked in the cleanup of what some of them had helped build years before. Recently they worked frantically to make One World Trade Center rise by one floor every week; scheduled to open in 2014, the 104-story structure is the tallest in the Western Hemisphere, and the fourth tallest in the world. Says one Mohawk ironworker, “One job I’ll always remember is working on the transit hub at the World Trade Center. Some of the iron was huge. I’ll never forget that feeling of seeing those pieces of iron, some thirteen feet high and sixty feet long, flying at you. Awesome.” And years ago another said, “It’s like you’re on top of the world. When you are up there you can see all over Manhattan. You’re like an eagle.”

© 2014 David Grant Noble

© 2014 David Grant NobleAnd recently another said, “A lot of people watch us and ask me if I’m crazy, but it’s fun. You got to love what you do.” And there he is, a fourth-generation Mohawk hardhat, 27 stories up, straddling an I-beam on top of a new skyscraper rising on 55th Street, with gloved hands grabbing a steel beam lifted high in the air by a crane and knocking it into a support column with a resonant gong.

© 2014 David Grant Noble

© 2014 David Grant NobleThe perilous work of steel workers perched on beams or clinging to cables high above the city without any safety apparatus visible, as they built the Empire State Building in the early 1930s, was captured by photographer Lewis Hine in photographs that, just to look at them, make you gasp and tremble and your legs go flimsy. Perhaps the most famous photo attributed to Hine shows eleven workers, some of them Mohawks, casually having lunch while sitting on a beam high in the air with no safety net below them, a photo that never fails to astonish me. Yet according to official records only five men died during the building’s construction, and only one by falling off a scaffold.

Are the Mohawks really fearless in such work? Some Mohawks say yes, but others insist that they’re just careful in following the rules: when walking on a girder, put one foot in front of the other and look ahead, never look down. Do they ever fall to their death? Yes, occasionally. Many graves on the reserve are marked with crosses made of steel girders.

(The photo of eleven workers having lunch has usually been attributed to Hine, and the construction site identified as the Empire State Building in 1932. But recently it has been revealed that the photo was taken on September 20, 1932, by an unknown photographer, and that it shows workers, two of them identified as Irish, working not on the Empire State Building but on Rockefeller Center.)

But the Mohawk “skywalkers” love what they do. And what have they and others done in the past? Rockefeller Center, the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Madison Square Garden, the U.N. building, the World Trade Center – you name it. And most of the city’s bridges as well. It’s a long six-hour commute from Canada, but it pays well and the benefits are good. But if there are 200 Mohawk ironworkers here now, in the 1950s there were 800. It’s hard work, and dangerous; now more young Mohawks are working in a tobacco industry flourishing on the reserve. And some ironworkers urge their sons to find other, less dangerous jobs. So maybe the tradition is dying: dying slowly, but dying. Time will tell.

Source note: Three of the photos in this post are from “Gallery 2: The Mohawk Steelworkers Series,” on photographer David Grant Noble’s website: davidgrantnoble.com. He took them of Mohawks at a building site on Park Avenue and 53rdStreet in 1970 and has generously allowed me to use them here.

This is New York

Coming soon: The Gentle Art of Pickpocketing: An Old New York Tradition. Have you ever had your pocket picked here in New York? If so, let me know. In the works: Ayn Rand, lean, hard, angular, and dry, yet her books are still selling. But did this ardent foe of government intervention sign up for Social Security and Medicare? Startling revelations to come.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on June 01, 2014 04:46

May 28, 2014

128b. More Eccentrics.

One of the followers of this blog sent this comment, after viewing post #128 on Village Eccentrics. It is too charming not to be included in a post, albeit a short one, a sort of postscript to #128.

In the mid-Sixties, I experienced an interesting period at WBAI that began when my secretary handed me an old-fashioned calling card introducing an imposing, smartly dressed septuagenarian who called himself Lord Rosti, and claimed to be the Grand Maître de la Cour for his Serene Highness, Prince Robert de Rohan Courtenay, Grand Duke Sebassto of the Byzantines. WBAI attracted many memorable people in those early years, but these two gentlemen—who played their roles to the fullest and had apparently been doing so since the 1920s—were the most interesting of the self-generated variety.

They came to me in 1966 for help in meeting certain requirements for a seriously overdue coronation. These included fifty Vestal Virgins and a rather large number of rare flamingoes from Japan's Imperial Gardens. We were unable to help meet those specific needs, but we did the next best thing by staging a coronation at Cheetah, New York's first discotheque. The year was 1966 and the actual crowning was performed by Andy Warhol, with incidental music by an obscure Tiny Tim, writhing by a barely clad lady and her boa constrictor, and the title ape from "Gorilla Queen: swinging from the rafters. I wish we had thought of taking photos, but we were a radio station and we didn't even broadcast it.

This brings to mind another eccentric whom I almost met back in the 1970s. His name was, I believe, Maurice, and he professed to be the founder and chief celebrant of the Old Catholic Church of Brooklyn. I never met him, but heard of him through friends, and once visited his apartment with mutual friends in his absence. My partner Bob recalls a grandiose painting of him in full ecclesiastical garb, a long robe that reached to the floor. What I myself distinctly recall is a framed letter on official Vatican stationery acknowledging with gratitude the receipt of a letter of consolation from the Old Catholic Church of Brooklyn following the death of Pope John XXIII in 1963. Was this concoction a joke, a sort of hobby, or a deep plunge into the misty realms of fantasy? I have no idea. I never met him, but Bob did, and he assures me that he was no nut, but a very sophisticated person. The Internet informs me that there is indeed an Old Catholic Church that has split off from Roman Catholicism, but I suspect that the Old Catholic Church of Brooklyn had nothing to do with it, being the private fantasy of its founder.

Coming soon: As announced, more ethnic groups, with prayer flags, burqas or the lack of them, and workers walking narrow girders at perilous heights. In the offing: The Gentle Art of Pickpocketing: An Old New York Tradition. And another remarkable woman: Ayn Rand.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on May 28, 2014 04:37

May 25, 2014

128. Village Eccentrics: Joe Gould and the Baroness

New York has always been a mecca for hustlers, and Greenwich Village, in its bohemian glory days before gentrification, was certainly a magnet for eccentrics. This post is about two Village eccentrics of yore. The high-rent West Village of today has an eccentric or two, but they pale in comparison with those of the early twentieth century, when the Village was still a low-rent district that attracted wannabe artists and writers and agitators, usually penniless, and the tourists who flocked there to live just a little bit dangerously by observing the scruffy inhabitants in their bars and cafés and getting just a little bit – or maybe more than a little bit – drunk. So here are two inhabitants who would not have disappointed the visitors.

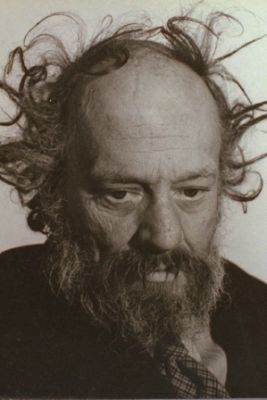

Joe Gould

He called himself Professor Sea Gull and Hot Shot Poet from Poetville, and the Village bartenders who served him, when he could cough up the price of a drink or, more likely, get someone else to pay for it, called him the Mongoose and other things as well. Only 5 foot 4 in height and weighing less than a hundred pounds, he knocked around the Village for decades with a wild, bushy beard and rumpled clothing, his balding pate topped by a beret or a yachting cap, his mouth graced with an ivory cigarette holder. Born to an old Boston family in 1889, he was a Harvard graduate who had come to New York in 1917 to work as a journalist, but soon learned that he could not or would not hold a steady job and succumbed to the charms of bohemia. Long before the Beatniks made dropping out fashionable, he professed to despise the automobile, the radio, zippers, money, and writers and reviewers, and dismissed skyscrapers and steamships as “needless bric-a-brac.”

Perennially penniless and sometimes homeless, Gould slept in flophouses or on benches in parks, and in diners wolfed down free ketchup by the spoonful. Turning up at Village parties to gobble snacks and gulp down cocktails, he would jump up on tables to give lectures with impossibly long titles, or deliver his poem “The Sea Gull” by leaping about, flapping his arms, and screaming, “Scree-eek! Scree-eek!” Or he recited his two-line “religious” poem: “In the winter I’m a Buddhist, / In the summer I’m a nudist.” He was charming, he was silly, he was close-lipped with the aura of a brooding genius, and he was always – or was always trying to be – entertaining.

But Joe Gould was more than just a clown and an eccentric; he was, the Villagers believed, a genius in the rough, a writer. Not just an ordinary, run-of-the-mill writer – the Village was full of them – but a very special kind of writer. Scribbling in longhand in dime-store composition books (he scorned the typewriter), he was writing a huge work-in-progress, “An Oral History of Our Time,” consisting of life histories told him by others that he had written down with the help of total recall, the chapters having titles like “The Good Men Are Dying like Flies” and “Why I Am Unable to Adjust to Civilization, Such As It Is.” He insisted that the nine-million-word Oral History weighed more than he did, and that later generations would hail him as the most brilliant historian of the twentieth century, his writing destined to last as long as the English language. Impressed, local poets, artists, shopkeepers, and restaurant owners gave him handouts of money or food to speed the project on its way. Starting in 1944 he was subsidized by a patron who worked through an intermediary and insisted on remaining anonymous, thanks to whose largesse he was lodged in a clean, comfortable room in a rooming house in Chelsea. Gould was obsessed at first with learning the identity of his benefactor, but never did. The subsidy was terminated abruptly in 1947, without explanation, and Gould soon ended up in yet another Bowery flophouse. The patron later turned out to be a Chicago heiress named Muriel Gardiner. Why she suddenly cut Gould off remains a mystery.

Not everyone, I suspect, treasured Joe Gould’s less than subtle sense of humor. Not everyone welcomed his barging into their party to gobble viands and make like a sea gull or recite – yet again! – his two-line poem. His repertoire was admittedly limited. And not everyone believed in his oral history, since its nine million words were nowhere in evidence, the manuscript being allegedly stashed for safekeeping at various sites in New York and New Jersey. Certainly he was a clown; was he a con man as well?

No, said journalist Joseph Mitchell, who met Gould in 1942, talked with him at length, and published a profile of him, “Professor Sea Gull,” in the New Yorker. Though he had never seen the manuscript, Mitchell believed in its existence, and his article made Gould a media event and tourist attraction. Reporters flocked to him, strangers bought poems from him, photographers found in him a willing subject, and there was even a Joe Gould Club in postwar Manila. Yet when Mitchell put Gould in touch with several New York publishers interested in publishing excerpts of his opus, nothing came of it. Gradually, Mitchell came to the belief that Gould was indeed a con man, and that the manuscript was a colossal hoax.

Meanwhile Gould’s health was fast deteriorating. He suffered dizzy spells, then confusion and disorientation, and collapsed on the street in 1952. Hospitalized in the psychiatric division of Bellevue Hospital, he was transferred to Pilgrim State Hospital in Brentwood, Long Island, where he died of arteriosclerosis and senility in 1957. He is buried in an unmarked grave in Ferncliff Cemetery in Westchester. In 1964 Mitchell published another profile in the New Yorker, “Joe Gould’s Secret,” revealing that the “Oral History” didn’t exist.

But that’s not quite the end of the story. In 2000 The Village Voice reported the discovery, in the archives of New York University, of eleven composition books constituting an 1100-page diary in Gould’s near-illegible scrawl, meticulously recording his daily life from 1943 to 1947, a work evidently unknown to Mitchell, who died in 1996. Gould had given them to an artist friend who, failing to find a publisher, later sold them to an archivist who sold them in turn to NYU. Was Gould then a literary genius after all? Alas, the diary simply recorded baths taken (for Gould, an event), meals eaten, dollars bummed, with the focus always on himself. His comment on V-J day and the end of the war? “There were a few bedbugs. So I slept poorly. Also there was a lot of noise.” Hardly material to enrich posterity. Yes, Joe Gould was a con man, but at least he was an interesting one, and the money he got by it was trivial; let’s not begrudge him that.

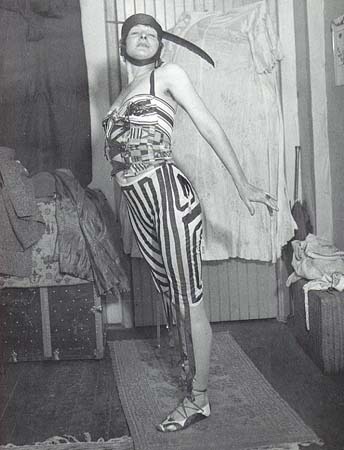

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

In all her glory. She burst into Greenwich Village in 1913, Dada incarnate with a bit of Surrealism thrown in, and was soon the most gossiped about, wondered about, photographed and sketched and painted, and praised and reviled character on the scene. Her outfits, like her art, consisted of objets trouvés (found objects) that she scavenged from trash on the city’s sidewalks. She showed up at the office of the avant-garde Little Review, which had published some of her incoherent poetry, in a bolero jacket, kilt, spats, and dime-store bracelets (she was definitely not in the chips), with tea balls hanging from her breasts. Her morals were as eccentric as her dress, for on that first visit the light-fingered visitor filched five dollars in stamps. And since she needed more than found objects for her art, she shoplifted art supplies from department stores and was arrested more than once, becoming intimately acquainted with the Jefferson Courthouse jail.

In all her glory. She burst into Greenwich Village in 1913, Dada incarnate with a bit of Surrealism thrown in, and was soon the most gossiped about, wondered about, photographed and sketched and painted, and praised and reviled character on the scene. Her outfits, like her art, consisted of objets trouvés (found objects) that she scavenged from trash on the city’s sidewalks. She showed up at the office of the avant-garde Little Review, which had published some of her incoherent poetry, in a bolero jacket, kilt, spats, and dime-store bracelets (she was definitely not in the chips), with tea balls hanging from her breasts. Her morals were as eccentric as her dress, for on that first visit the light-fingered visitor filched five dollars in stamps. And since she needed more than found objects for her art, she shoplifted art supplies from department stores and was arrested more than once, becoming intimately acquainted with the Jefferson Courthouse jail.

An instant legend, her startling presence became a fixture at Village romps and revels, where she appeared with teaspoons or matchboxes as earrings, a bra composed of tomato cans, a birdcage around her neck with a live canary inside, false eyelashes made of parrot feathers or porcupine quills, and hats made from peach baskets or wastepaper baskets. She marched into a reception for the British coloratura Marguerite d’Alvarez with a peacock fan, one side of her face adorned with a canceled U.S. postage stamp, her lips painted black, her face powder yellow, with the top of a coal scuttle for a hat. What the singer thought of this is hard to say.

She lived in a tenement on West 14thStreet amid squalor that visitors did not find picturesque, with stray cats and dogs poking about in the clutter of scavenged objects; by all accounts the place simply stank. On her forays from there she carried small dogs and large sculpted penises, these last a significant icon since she was aggressive in pursuit of men. When she made a pass at Wallace Stevens, he refused to set foot below 14th Street lest he encounter her again. And a Russian painter, when he turned on the light in his apartment one night, was startled to see her crawl out naked from under his bed. Alarmed, he fled to a neighbor across the hall, but the intruder refused to leave the premises until the painter agreed to follow her up to her own apartment.

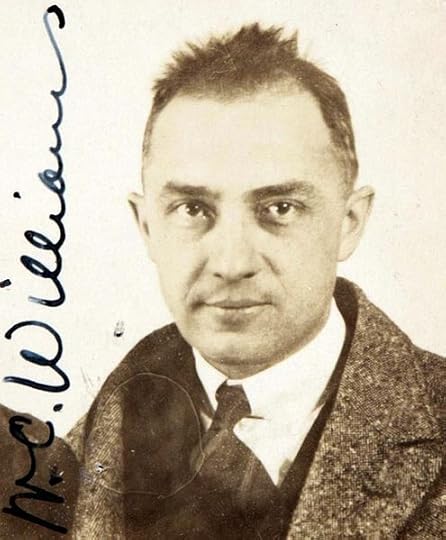

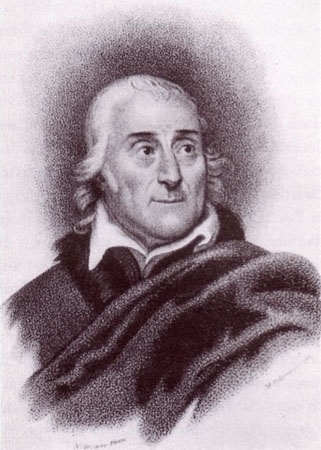

William Carlos Williams, a 1921 passport photo. In his autobiography William Carlos Williams tells of seeing a sculpture of hers that looked like chicken guts in wax and, hearing that she loved his poetry, decided to look her up – not easy, since she was in jail for stealing an umbrella. So he met her on her release, a fiftyish woman with a lean, masculine figure and a strong German accent, and took her to lunch. He was attracted to her, and on a later occasion she informed him that what he needed to make him great was to contract syphilis from her and thus free his mind for serious art – a suggestion that he chose to ignore. She pursued him for months, and when he proved to be uncooperative, hit him on the neck with all her strength. So Williams bought a small punching bag and began practicing his jabs. The result: when she attacked him again one evening on Park Avenue, he flattened her with a stiff punch to the mouth. He then had her arrested, and from behind bars she promised not to bother him again. Heartbroken by this rejection, she is said to have shaved her head and lacquered it vermilion, then stole the black crepe from the door of a house in mourning and made a dress of it. Always an artist, always unpredictable.

William Carlos Williams, a 1921 passport photo. In his autobiography William Carlos Williams tells of seeing a sculpture of hers that looked like chicken guts in wax and, hearing that she loved his poetry, decided to look her up – not easy, since she was in jail for stealing an umbrella. So he met her on her release, a fiftyish woman with a lean, masculine figure and a strong German accent, and took her to lunch. He was attracted to her, and on a later occasion she informed him that what he needed to make him great was to contract syphilis from her and thus free his mind for serious art – a suggestion that he chose to ignore. She pursued him for months, and when he proved to be uncooperative, hit him on the neck with all her strength. So Williams bought a small punching bag and began practicing his jabs. The result: when she attacked him again one evening on Park Avenue, he flattened her with a stiff punch to the mouth. He then had her arrested, and from behind bars she promised not to bother him again. Heartbroken by this rejection, she is said to have shaved her head and lacquered it vermilion, then stole the black crepe from the door of a house in mourning and made a dress of it. Always an artist, always unpredictable.As for her poetry, it bristled with phrases like “spinsterlollypops” and “Phalluspistol.” But what should one make of this?

Narin-----Tzarissamanili (He is dead) Ildrich mitzdonja-----astatootch Ninj-----iffe kniek----- Ninj-----iffe kniek! Arr-----karr----- Arrkarr-----barr

Or:

Neighing Stallion: HUEESSUEESSUEESSSOOO HYEEEEEE PRUSH HEE HEE HEEEEEEAAA OCHKZPNJRPRRRR

I leave it to equinophiles to decide to what extent this conveys the neighing of a horse.

When printed in The Little Review alongside chapters of James Joyce’s Ulysses, her effusions elicited two responses: some readers hailed her as an avant-garde genius, while others begged the Review to stop printing gibberish. The latter view has since prevailed, but feminist scholars have hailed her as a pioneering woman and neglected artist who exerted a significant influence on the Dada movement, and seen in her the first American performance artist. In 2011 her mostly unpublished poetry was published posthumously as Body Sweats, which caused the New York Times to salute her as a “furiously witty and aggressively erotic experimental writer,” though I haven’t had the courage to look into it.

Was she really a baroness? By marriage, yes. But who really was she? Recent scholarship has given us some clues. She was born Else Plötz in Swinemünde in Pomerania, Germany, in 1874, her father a mason who abused her in her childhood. Escaping young in 1892, she became an actress and vaudeville performer and, sexually hungry from an early age, mingled limbs and loins with artists in Berlin, Munich, and Italy. Tall, slender, and handsome, in 1901 she married August Endell, a renowned Berlin Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) architect, but soon became involved with a friend of his, poet and translator Felix Paul Greve, thus initiated a merry ménage à trois that for a while bounced around the continent together. She and Endell divorced in 1906. Greve meanwhile was convicted of fraud and served a year in prison, his reputation shattered, though he used his time inside to write a roman à clef recounting Elsa’s sexual escapades. After his release she and Greve lived in voluntary exile in Switzerland and then in France, and were married in Berlin in 1907.

Greve was soon in deep financial trouble again, so in 1909 with Elsa’s help he faked his own suicide and sailed for Canada, then relocated to Pittsburgh, where his wife joined him in 1910. The couple briefly ran a farm in Kentucky, though the idea of Elsa on a farm anywhere is both ludicrous and enigmatic, but she wasn’t there for long. Greve left her in 1911 and moved to Canada, where he remarried without bothering to divorce Elsa, and took the name Frederick Philip Grove and became a well-known Canadian novelist. Deserted in rural Kentucky and with only a limited command of English, to support herself Elsa modeled for artists in Cincinnati and finally ended up in New York where, in 1913, though technically still married to Greve, she married the impecunious German-born Baron von Freytag-Loringhoven, thus acquiring the title of baroness. Little is known of the Baron, but when World War I broke out in 1914, he set sail for Germany to join in the war effort, but was captured by the British en route and interned; later he committed suicide, leaving her nothing but her title.

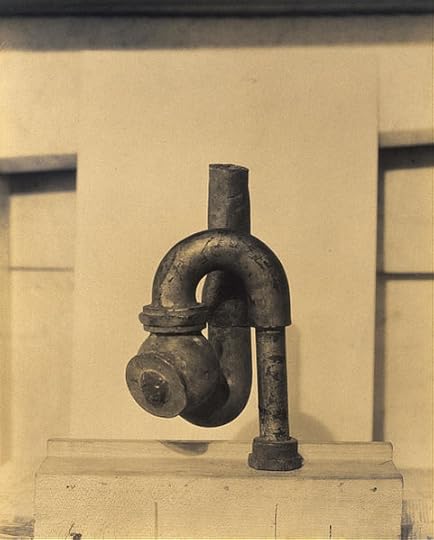

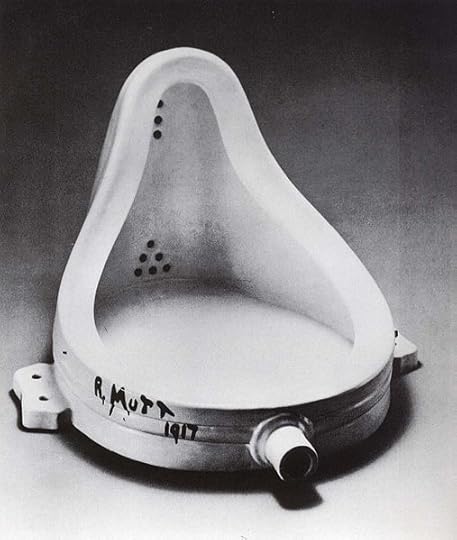

To support herself in New York, the Baroness worked in a cigarette factory and posed as a model for various artists, including Man Ray. When Dada reached these shores, she was celebrated as its epitome, as one who dressed it, loved it, lived it. One of her more memorable “ready made” sculptures, often attributed to another artist, was a plumbing pipe she titled “God.” She may also have helped inspire Marcel Duchamp’s controversial sculpture “Fountain,” an upturned urinal; her love for him was apparently obsessive. She even starred in a short film by Duchamp and Man Ray entitled “The Baroness Shaves Her Pubic Hair,” beside which Andy Warhol’s later efforts seem to verge on timidity.

"God." But does it really belong

"God." But does it really belongin a museum?

Duchamp's "Fontaine." It probably

Duchamp's "Fontaine." It probably upstaged "God."

When the war ended, many of her friends decamped for Paris, and she longed to follow them. With help from her Dadaist acquaintances, in 1923 she went back to Berlin, hoping for better opportunities there, but instead found an economy devastated by World War I. She remained there, impoverished and mentally unstable, immune to the decadent charm conveyed by Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, reduced to selling newspapers on the street. A letter to Djuna Barnes describes the ensemble she wore to the French consulate, hoping to get a visa that would let her go to Paris: ropes of dried figs around her neck, postage stamps as beauty spots on her emerald-painted cheeks, and topping her head a sugar-coated birthday cake with fifty flaming candles. The consulate officials probably decided that Paris had enough nuts already and didn’t need another; she didn’t get the visa. Meanwhile she was bombarding friends, acquaintances, and ex-lovers with letters and letter/poems pleading for money.

In 1926 an inheritance let her at last get to Paris, where Djuna Barnes paid the rent on her apartment, and she resumed modeling and tried to market her poetry to the few exile journals publishing in English. In 1927, at age 53, she died of asphyxiation in her apartment, when the gas was left on overnight. Suicide or an accident? It isn’t clear. She is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Artistic genius before her time, pioneer feminist, sexual adventuress, exhibitionist, obsessive narcissist, and nut – she has been called all these, and more. Certainly, when she came to New York, she crossed the vague line separating charming eccentricity and self-expression from out-and-out weirdness, but that was just what the Dadaists wanted. Dada raged for a few brief years in Paris and Germany, but to judge by photographs the Dadaists there dressed more or less normally and put weirdness into their art; she was unique. And yet, in her later years at least, she seems to have been mentally unstable. As for her death, maybe it really was suicide; being perpetually onstage and perpetually broke may have worn her out. And if she is celebrated by feminists today, I suggest that posthumous celebration from a safe remove is quite different from dealing with such a phenomenon in the flesh. Given her brazen advances and grotesque behavior, even in such an enlightened age as ours some people might be perversely tempted, taking inspiration from William Carlos Williams, to punch her in the mouth.

This is New York

Schuyler Shepherd

Schuyler Shepherd

Coming soon: More immigrants: yak meat and momos, and why prayer flags flutter in the breeze; getting free of the burqa in an alien land; and how a people who revere the earth came to work high in the sky.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on May 25, 2014 04:52

May 18, 2014

127. Ethnic New York: Sherpas, Basques, Gypsies, Sikhs

Immigrants are an integral part of New York City; we couldn’t do without them. My partner Bob’s doctor is Norwegian, his home-care aides are Haitian and Russian, his Visiting Nurse is Cambodian, and her most recent substitute was Filipino. And on Saturdays I buy bread, scones, and apples from Tibetans in the Abingdon Square Greenmarket.

This post is about certain groups of immigrants, often ignored by the rest of us, who live here and contribute to the city’s patchwork of diversity. Especially, it is about the most exotic, most alien groups, their customs and beliefs so different from mainstream America’s, and about how and why these peoples came to New York.

Sherpas

Sherpas in New York City? That very special ethnic group in Nepal who guide climbers to the top of Mount Everest, the highest mountain in the world, sixteen of whom perished in a killer avalanche, causing some Sherpa guides to quit for the season and many to protest the conditions of their work? Here, so far from the Himalayas? Yes, here, a mere handful first coming in the mid-1980s and more thereafter, so that there are now some 2,500 or more of them, mostly in the ethnically diverse Elmhurst section of Queens, the biggest Sherpa community in the country. And they are grieving for their comrades who died on the mountain.

A Sherpa guide. Wouldn't you rather drive a taxi?

A Sherpa guide. Wouldn't you rather drive a taxi?Pem Dorjee Sherpa

Why are they here? Because some of them realized the risks of their traditional profession of guiding wealthy foreigners to dangerous mountaintops, so those intrepid thrill-seekers could bask in the glory of accomplishment and see their names in newspapers, followed laconically by “and six Sherpa guides.” Because, if they renounced that profession, they could find no other work as lucrative in Nepal. Because a lengthy civil war in Nepal scared mountain-climbing tourists away, depriving the guides of a livelihood. Because they want to transition to another way of life. Because in New York they can make good money.

“Climbing was in my blood,” says one. But after getting married and starting a family, he stopped climbing for his own safety. And what does he do for a living here? What many of them do: he drives a cab. A “good, bad, ugly job,” he calls it, working twelve-hour shifts six nights a week. His chief complaint: people having sex in his car.

Are the Sherpas here, good Buddhists for the most part, adapting to life in hectic America? Perhaps it can best be summed up by two links posted on the United Sherpa Association website: “Nepal Sherpa Guide” and “Sherpa Computer Services.” So it goes when one comes down from the mountains and plunges into the canyons and labyrinths of New York City.

Basques

They first came to this country lured by the gold rush in California, taking the long trip by sea around the southern tip of South America into the Pacific and up to San Francisco, where so many dreams came to dust, though not the dust of the goldfields. But who were they, coming such a long distance from the homeland where they had lived since prehistoric times?

The Basques are a people living in north central Spain and southwestern France, straddling the Pyrenees. Their origins are a mystery, since their language is unrelated to Indo-European languages and probably predates the arrival in Europe of the Indo-European peoples. Basque tribes are mentioned by Roman writers and were probably remnants of early inhabitants of Western Europe. In recent times the Basques have been featured in the news because of their desire for greater autonomy in Spain, with the organization ETA advocating outright independence and committing acts of terrorism, but in 2010 the group declared a permanent ceasefire that is still in effect.

A Basque festival in Spain.

A Basque festival in Spain.dantzan Today, reflecting their initial influx in the mid-nineteenth century, there are large Basque communities in the Western states. In New York City the first Basques began arriving after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Departing from Bordeaux or Le Havre, some, having worked as dock workers, came to work in the harbor, whereas others planned to move on west by railroad, but ended up staying in New York, where they found work in the ports of New York and New Jersey. For those from rural areas the city was overwhelming, but others were energized by it. The first Basque community took hold at the foot of the Brooklyn bridge along Cherry and Water Streets in Manhattan. There were Basque groceries and restaurants, Basque delivery services, and Basque wine and beer distributors, and most of the Basques attended Mass at the nearby Catholic churches, one of which even had a Basque priest.

It was to this small but growing community that a young Basque named Valentín Aguirre came to work as a tugboat stoker in the harbor, and then on the city’s boats and ferries, before opening a Basque boardinghouse in 1917, the Casa Vizcaína on Cherry Street, that catered exclusively to Basques. He married here, and his Basque wife helped run the boardinghouse. When they were old enough to drive, he sent his young sons to meet incoming ships at the docks and call out, “Euskaldunak emen badira?” (“Are there any Basques here?”). Arriving Basques would shout back in relief and joy, “Bai, bai! Ni euskalduna naiz!” Of course they lodged at the boardinghouse, by then renamed the Santa Lucia Hotel and located at 82 Bank Street in Greenwich Village, which functioned as a travel agency as well, getting train tickets and information about jobs for those bound for the West, and seeing them off with bundles of food for the long train trip ahead.

A Basque magazine.

A Basque magazine.Joxerra

In 1913 Valentín Aquirre and other Basques formed the Centro Vasco-Americano, originally as a mutual-aid society to help members financially if in need. The organization continued through the years, and in 1973 it bought a building at 307 Eckford Street in Brooklyn, where, with the name in English of New York Basque Club, they are still located today, though the Basques in the city now are scattered throughout the five boroughs. In October 2013 they celebrated their centennial with lectures, concerts, dancing and singing, plus participation in the annual Columbus Day Parade. Among the many activities they offer are lessons in Euskara, the language of the Basques, the only one predating the Indo-Europeans that is still extant in Europe today: a reminder of the mysterious origins of this persisting people.

Romani or Gypsies

In France they have been accused of shocking living standards, exploitation of children for begging, criminal acts and rioting, and prostitution, and thousands have been expelled and their illegal camps dismantled; one camp was even set on fire by a mob. Greek and Irish authorities have suspected them of abducting children. Italy has announced a “nomad problem” and initiated forced evictions. A Czech town tried to build a wall between its wealthy neighborhood and their ghetto, and some schools in Eastern Europe have posted signs “WHITES ONLY.” Many of these people are unemployed, most live in poverty, and the temptation to crime is admittedly strong.

Such is the plight of the Gypsies, also called Romani or Rom or Roma, in Europe today. Is it any wonder that they want to come over here, where the prejudice against them, however strong, is less than in the Old World where they have lived for centuries? But just as with the Basques, one has to ask, Who are they?

A people presumably of Indian origin who arrived in Europe at least a thousand years ago, the Romani are widely dispersed, many living in various parts of Europe and, since the nineteenth century, in the Americas, with a million now in the U.S. The name “gypsy” derives from “Egyptian,” reflecting the common medieval belief that the Romani, with their swarthy complexion, had come from Egypt. Their language, Romani, is Indo-European, but variations of it are so different that seven of them are considered separate languages.

Croatian Gypsy women with their children, 1941. Just the kind of image that reinforced

Croatian Gypsy women with their children, 1941. Just the kind of image that reinforced European prejudice against them.

German Federal Archives

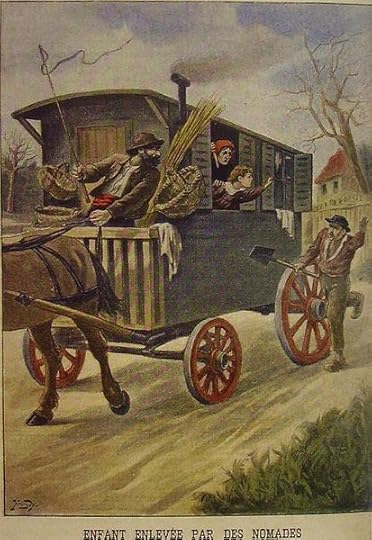

An old print showing Gypsies

An old print showing Gypsies kidnapping a child. Over the centuries the Romani have been persecuted in Europe as unassimilated, rootless nomads, allegedly ungodly, lazy, and given to petty theft and the kidnapping of children. Viewed by the Nazis as an inferior race, between 500,000 and 1.5 million died in the holocaust. Yet in literature and art they have often been romanticized as well, with supposed powers of fortunetelling, a passionate temperament, and a love of freedom. (Think of Bizet’s Carmen.)

Romani from Serbia, Austria-Hungary, and Russia began emigrating to the U.S. in the 1880s, until the outbreak of war in 1914 and the tightening of immigration restrictions in 1917 halted this early influx. Some were coppersmiths, others were fortunetellers. Musicians and singers from Russia settled in New York, and in 1904 a group recently arrived from England were living in a camp of wagons with curtained windows in a meadow near Broadway and 211thStreet in Manhattan, and making their living as horse traders and fortunetellers. Other Romani from Bosnia who worked as animal trainers and showmen settled in a village of homemade shacks in the Maspeth section of Queens from about 1925 to 1939, when their shacks were razed.

The collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 led to a renewed flow of Romani emigration to the U.S. Here in New York City they often live in small communities in Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens that keep to themselves. They are by no means homogeneous; those from Hungary may have little in common with those from Slovakia; some may be Christian and others Muslim; some speak one dialect of the Romani language, while others speak another. In the neighborhood north of Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, some 350 families of Macedonian Romani live in a tight-knit Muslim community content to be viewed by others as Italian or Greek. Why did they come here? To find work for themselves and educational opportunities for their children that they couldn’t find in Europe.