Clifford Browder's Blog, page 34

July 13, 2016

243. Dorothy Norman and Alfred Stieglitz

[This post is a reblog of post #147, another of the most visited posts of this blog.]

She is 23, dark-haired, beautiful, with big brown eyes, and wants to know about art. He is 64 -- old enough to be her father and then some -- with deep-set, piercing eyes framed by glasses, his hair and mustache gray and bristling, and he knows all about art. She encounters him in a shabby little gallery on Park Avenue where he holds forth daily in a resonant voice, telling visitors that the world of our dreams is more real than the world that exists, and that art, like all love, is rooted in heartache. He makes the first satisfying statements about art she has ever heard and speaks with total conviction; she is entranced.

The young woman goes back to the little gallery again and again, listens to the man talk to others about art, learns his name, writes down afterward what he has said. The paintings shown there fascinate her, as does the man himself. Finally she speaks to him, talks with him about art. His words pour forth, don’t explain anything, but change something indefinable inside her. Though the paintings exhibited are available for purchase, he isn’t selling them, just talking about them, about art. He says the very things about art that she has been waiting to hear from someone knowledgeable and mature. Finally she writes him a breathless letter, says she can’t keep away from the gallery, loves what he is doing there, would like to help him do it. Answering her letter in bold black strokes of a pen that are almost chilling in their beauty, he tells her to feel free to come to the gallery and ask all the questions she likes. She does. She talks with him, looks at his photographs, feels his attraction like a great force of nature.

One day they find themselves alone in the gallery; a tense silence, as they look at each other intently.

“I want to say something to you,” she whispers.

“Say it,” he says. His voice is encouraging, but she holds back. “Say it.” “I can’t.”

“Say it.”

She makes a great effort. “I love you.”

His face softens. “I know – come here.”

He kisses her. Their lives are changed forever.

She is Dorothy Norman, a young woman from an affluent Jewish family in Philadelphia who is now living in New York. He is Alfred Stieglitz, a renowned photographer and fervent advocate of contemporary American art. The year is 1928. She has met the man who, more than any other, will profoundly influence her life. There is just one problem: they are both married, but not to each other, and feel a loyalty to their respective spouses. And she has just given birth to her first child. So begins a long, fervent, but complicated relationship that could have happened only in New York.

Born Dorothy Stecker to an affluent Jewish family in Philadelphia, she grew up surrounded by privileges that puzzled, then annoyed her. At a party in New York in 1924 she met Edward Norman, the son of a wealthy Sears Roebuck heir and they fell in love; overcoming opposition from both families, they married in 1925; she was 19, he was 25. On the wedding night he was dismayed, then angry, to learn that her parents had told her nothing about sex. When he entered her, she felt agonizing pain, bled, sobbed; in the morning, apologies on both sides, tenderness, assurances that all would be well.

They moved into an apartment on East 52nd Street in New York, lived well but not lavishly, traveled abroad, became involved in progressive causes, advocated reform, not revolution. Though given at times to outbursts of anger, her husband was intelligent, knowledgeable, idealistic; she admired him greatly. She did volunteer work for the ACLU, visited art galleries and then, at the Intimate Gallery on Park Avenue, she met Alfred Stieglitz.

A strange but passionate relationship developed. Stieglitz was wise, informed, mature, yet possessed a youthful vigor and sense of fullness about life unlike anyone she had ever known. She didn’t see in him a father but a lover and mentor; they wrote, phoned, and saw each other daily, experienced physical love that she found breathtaking, almost frightening, in its intensity.

And the spouses? She still loved her husband, but in a different way, had no thought of divorcing him. They lived, vacationed, and traveled together, but the relationship must have been altered since he surely knew of her affair with Stieglitz almost from the start. How did he feel about a wife who, to be sexually and emotionally fulfilled, needed both a husband and a lover? Candid as her autobiography can be, of this she says almost nothing. She and Edward shared much, and yet …

As for Stieglitz, he was married to the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, 23 years his junior, and likewise had no thought of divorce. He had discovered her years before, a talented young artist who had yet to make a name for herself, and had divorced his first wife to marry her and promote her work. To judge from Dorothy Norman’s memoir, one might think that O’Keeffe and Stieglitz were by now estranged, but O’Keeffe’s biographer, Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, tells it differently: O’Keeffe was heartbroken by her husband’s open affair with Norman but endured it until 1933, when she suffered a nervous breakdown that hospitalized her for two months. After that there was indeed estrangement, as more and more she pursued her art in New Mexico, far from Stieglitz and Norman.

A personal note: I first heard of Dorothy Norman when, as a freelance editor in the early 1980s, I was hired by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich to edit the manuscript of her memoir, Encounters. I worked with an in-house editor from whom I learned certain things about Norman not mentioned in the memoir; I will introduce them when and if relevant.

With Stieglitz’s help, as well as her own beauty, intelligence, and charm, Dorothy Norman expanded her horizons and deepened her understanding of art. At a party she met the artist John Marin, whose work she particularly esteemed, and the sculptor Gaston Lachaise, and became good friends with both. She met Georgia O’Keeffe, a handsome woman strikingly dressed in black with a touch of white, though for obvious reasons the acquaintance could only go so far. In 1929, when Stieglitz learned that the Intimate Gallery must vacate the premises, she and O’Keefe and others helped finance a new and better gallery, An American Place, at 509 Madison Avenue. There Stieglitz, who disapproved of the recently founded Museum of Modern Art’s emphasis on “French Old Masters” (meaning Impressionists and Post-Impressionists), could continue to exhibit and promote American art. At his insistence the walls were painted white and gray and were unadorned, so as to convey an atmosphere of austerity, nor was it listed in the phone book. But right from the first – even in the wake of the Crash – people flocked to it.

Among those she came to know at this time, whether at An American Place or elsewhere, were the poet Hart Crane and the young theater director Harold Clurman. Clurman, who always enjoyed the company of attractive young women, took to her at once and expounded excitedly on the American theater’s need for direction, for a philosophy of life, and she helped raise funds so he and his colleagues could found the Group Theatre and put these ideas into practice. Through Stieglitz and her own social connections she was now well on her way to becoming the self-assured and knowledgeable young woman who knew everyone.

And her husband? She continued to admire his honesty, intelligence, and integrity, but realized with great regret that they were growing differently, and apart. Further endangering their relationship were his irrational outbursts of anger and her increased awareness that he was psychologically disturbed. Concern for their two children and a persistent devotion sustained their marriage, and every year they summered together in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. But their youthful hopes and dreams were fading fast.

Stieglitz photographed her repeatedly and taught her to become a photographer herself. And in 1932 he arranged the publication of her poetry, which she herself feared was too immature. In her memoir she tells how she sent the volume to her British friend Dorothy Brett, an artist and onetime associate of D.H. Lawrence living in Taos, New Mexico, and was amazed by Brett’s enthusiastic response, which proclaimed the poems “beautiful” and “incorruptible.” Yet in the manuscript I edited, as I recall, it went somewhat differently. Yes, Brett praised the poems, but only after Norman waited anxiously for a response and finally queried Brett about her reaction, thus putting Brett in an awkward position, torn between candor and the claims of friendship. Was Brett’s response the response of friendship or was she truly impressed? And wasn’t Norman a bit of a dabbler here? Serious poets work at their craft for years. Norman didn’t pursue her poetry, having other and stronger claims on her attention. Throughout her life she had so many interests, and went in so many directions, that she risked – perhaps unfairly -- the label of dilettante.

Indeed, she had so many commitments and knew so many people, only a few of her “encounters” can be chronicled here. She helped Henry Miller financially so he could return from Europe and, when she met him, was surprised to find, not the sensual, rather ferocious man she anticipated, but a modest and proper individual who resembled a preacher. Through him she met his inamorata the author Anaïs Nin, who struck her as almost nunlike in her simple gray coat and hat, though her small mouth was carefully painted, and her mascaraed eyes stared at Norman ecstatically. Norman soon realized that Nin was slowly drifting apart from her wealthy banker husband, just as she was drifting apart from Edward.

In 1937 she began publishing Twice a Year, a journal of literature and art, which she herself financed; well-known writers, including European expatriates soon displaced by the war, appeared on its pages: Sherwood Anderson, Richard Wright, Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, and later Sartre and Camus. Then in 1942 she began writing a column for the New York Post entitled “A World to Live In,” commenting on social welfare issues and politics. The column would continue for seven years, and she became involved in city and state politics, even to the point of being offered political positions and a chance to run for Congress, invitations that she always turned down, knowing that politics and the compromises it entailed were not for her.

Neither she nor her husband liked living ostentatiously. Their Park Avenue apartment building was designed to look imposing, with a gloomy and pretentious entrance hall, a uniformed doorman and elevator man, and an apartment with ugly windows, false moldings, and sconces with pointed light bulbs absurdly imitating candles. So the Normans engaged a large real estate firm to find them an unrenovated house no wider than twenty feet, with no tall buildings in front or back, the rear facing south, and not near an elevated or bus line, since they both slept badly. And it should not be above 79th Street or below 68thStreet on the East Side of Manhattan. Rather strict requirements for a couple in search of something simple, but they found it: a Victorian brownstone at 124 East 70th Street, nineteen feet wide with a high front stoop, in dire need of renovation. Months of work followed as the front of the building was moved forward, the rear slanted to admit the most daylight possible, and the interior reorganized imaginatively to create spare, clean lines throughout. Finally, in 1941, they moved in. The building was voted one of the two best new buildings of the time; photographs of it were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art; and architecture students gathered outside to sketch it and often asked to be shown through. Simplicity had been achieved.

Joining the newly established Liberal Party in 1944, she found herself involved in debates as to who the party should endorse for mayor. The feeling against William O’Dwyer, a former Brooklyn district attorney, was strong, since he had Tammany backing, but she decided to interview him for her column. Since he was off in seclusion in California planning his strategy, she made a long-distance call and, to her surprise, reached the man himself. A candid conversation followed, and an invitation to meet him in New York. He proved to be a ruddy-faced man, well built but hardly handsome, with an Irish sense of humor, and she urged him to run for mayor and be a great one. Leaving the Liberal Party, she supported O’Dwyer and was delighted when he won. From then on she called him daily at 8:30 a.m. on a private line and had talks with him that were often hilarious. He read passages from Yeats to her, then they talked politics; he listened to her suggestions about health and hospitals, day-care centers, delinquency, whatever. Knowing she was “in” with the mayor, people played up to her, hoped for an introduction. “Of course you’re having an affair,” a journalist friend told her. “Everyone knows it.” Which made her furious, since she never saw O’Dwyer alone, was most definitely not having an affair with Hizzoner, and had even declined positions that he and others offered her.

In July 1946, while summering in Woods Hole, she got a phone call from a friend informing her that Stieglitz had had a stroke and was in a hospital, and she must come at once; O’Keeffe was in the Southwest. Her husband was kind and understanding, had no objection to her going. She rushed back to New York, went to the hospital, found him in a coma but with a look of peace on his face; later she broke down, wept. O’Keeffe arrived the next day, their paths didn’t cross; Norman made no further attempt to see him, knew that he was dead. Harold Clurman phoned her in sympathy, found her a typewriter so she could do a brief obit for the Post, then accompanied her to a restaurant for dinner. They were sitting at a table outside when suddenly, quite by chance, Eleanor Roosevelt walked by with a companion and saw her. The former First Lady approached and greeted her graciously and in a warm and cordial voice asked what she was doing in New York in the miserable summer heat.

“I’m here because a great friend, Alfred Stieglitz, has died. I’ve come down for his funeral.”

Eleanor Roosevelt looked at her, perplexed, not having the slightest idea who Stieglitz was. Norman wept, uttered a perfunctory wish that Mrs. Roosevelt was well.

Did Norman and O’Keeffe encounter each other at the funeral? Her memoir doesn’t say, but one suspects that Norman maintained a discreet distance. Back in Woods Hole, having read again the last note Stieglitz had sent her the day before he died, she wrote a poem that she could show to no one.

Stieglitz’s death, however shattering, did not keep her from being Dorothy Norman, the woman who knew everyone. Her “encounters” continued: Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Richard Wright, D.T. Suzuki, Osbert Sitwell and his sister Edith, Saint-John Perse, Jawaharlal Nehru – the list is endless.

When her husband became stern, dictatorial, harsh with the children and her, Dorothy Norman, fearing sudden violence on his part, went to Reno in 1953 and got a divorce. They both were heartsick. She then went on to make more friends, develop an interest in myth and symbolism, and work on her memoir, which she told her in-house editor could never be published while Georgia O’Keeffe was alive. O’Keeffe died in 1986, and the memoir appeared in 1987 with a dedication “To Edward, my first love.” It does not chronicle her later years, and with a single exception includes only photographs of her in her youth. She died in 1997 at age 92.

What is one to make of this woman who knew everyone? Limousine liberal, do-gooder, dilettante – she can be stuck with all these labels, but I think it would be unfair. She served the great without herself attaining greatness. She never worked a day in her life, in the sense of a salary-paying job, but she was constantly busy, never idle. A doer, she made things happen. What was it that let her bond so easily with others? Her beauty, her charm, her intelligence. And from that bonding came results: books, articles, exhibitions, her biography of Stieglitz, her collection of Nehru’s writings, the Alfred Stieglitz Center in Philadelphia. And if her later turn toward myth and symbolism gets a bit vaporous and “New Agey,” that is probably the case with most Western followers of the great traditions, which for deep understanding require a focused lifelong commitment that few of us can offer. But Dorothy Norman lived intensely, lived meaningfully. May we all do as well.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received two awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction, and first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. (It also got an honorable mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards, but that hardly counts.) As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Coming soon: Tammany, the tiger whose claws got clipped.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on July 13, 2016 05:57

July 10, 2016

242. Willie Sutton

On February 15, 1933, a postman entered the Corn Exchange Bank and Trust Company of Philadelphia, but an alert passerby foiled the attempted robbery and the postman fled.

On another occasion a postal telegraph messenger entered a Broadway jewelry store in broad daylight, robbed it, and escaped.

On other occasions the thief disguised himself as a police officer, some kind of messenger, a window washer, a maintenance man, or a striped-pants diplomat. No wonder he was known as “Willie the Actor” and “Slick Willie.”

Prisons had trouble holding him. Captured in June 1931 and sentenced for assault and robbery to 30 years in Sing Sing, on December 11, 1932, he used a smuggled gun to take a prison guard hostage, then got hold of a ladder, scaled a 9-meter wall, and escaped.

Captured again on February 5, 1934, he got 25 to 50 years in the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, but on April 3, 1945, he and 11 other convicts escaped from there through a tunnel. Alas, he was recaptured that same day by a Philadelphia police officer.

Sentenced to life imprisonment as a fourth-time offender, he was transferred to the Philadelphia County Prison, but on February 10, 1947, he and some other prisoners disguised themselves as guards and after dark carried two ladders across the prison yard to the wall. When the prison searchlights spotted them, he yelled, “It’s okay!” And off they went to freedom.

On March 20, 1950, he was the eleventh criminal listed on the FBI’s newly created Ten Most Wanted List, replacing one of the original ten who had been captured.

When asked why he robbed banks, he allegedly – and famously – replied, “Because that’s where the money is.”

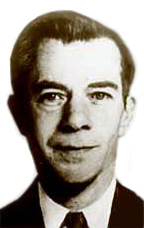

The gentleman in question – and by all accounts he was indeed a gentleman – was Willie Sutton (1901-1980), a Brooklyn-born desperado who preyed upon the banks of the eastern United States for some 40 years, and who, despite his three escapes, spent more than half his adult life in prison.

Slick Willie

Slick WillieBrooklyn-born to an Irish-American family, he was the fourth of five children but never went beyond the eighth grade in school, finding that his talents led him elsewhere. Willie was slight of build, just 5 feet 7, a gentleman by all accounts, a chain smoker, a constant talker whose witty talk entertained all within earshot, including the Mafiosi who befriended him and protected him from assaults when in prison.

In all his long career of robbing banks, Willie never committed an act of violence, and even insisted that the weapons he carried weren’t loaded. Because yes, although a gentleman, he did carry a revolver or a Thompson submachine gun, since, as he explained, “You can’t rob a bank on charm and personality.” But he claimed that he never robbed a bank if a woman screamed or a baby cried. Had the bankers known this at the time, they might well have hired some women to be on the scene, ready to emit ear-splitting screams of alarm.

His final capture came in Brooklyn on February 18, 1952, when a young clothing salesman named Arnold Schuster recognized Willie on the subway and followed him out onto the street, where he alerted two police officers on patrol. They found Willie hunched over his car, fixing a dead battery. Asked for his registration, he produced a document identifying him as Charles Gordon. The officers summoned a detective, and the three of them escorted their prisoner to the station house for questioning. Willie was amazingly calm and went along without protest. About to be fingerprinted, he admitted to being the famous Willie Sutton. The two arresting officers were immediately promoted three ranks to first-grade detective, and Police Commissioner George P. Monaghan called the arrest the culmination of “one of the greatest manhunts in the history of the department.” Willie, it turned out, had been living in a $6-dollar-a-week room only a few blocks from the police headquarters in Brooklyn. Reporters flocked to the station house, where Willie was paraded before them in the company of his nemesis of three.

Mr. Schuster went on television to recount how he had helped the police capture Willie. On March 9, 1952, he was killed on a Brooklyn street outside his home, shot once in each eye and twice in the groin. The murder was never solved, but it is said that Albert Anastasia, the much feared Mafia boss of the Gambino crime family, a veteran hit man known as “the Lord High Executioner,” concluded that Schuster was a “squealer” and ordered the murder. Anastasia himself met a similar fate on October 25, 1957, while sitting in a chair in the barber shop of the elegant Park Sheraton Hotel in Midtown Manhattan, his face swathed in white towels; two men with scarves covering their faces entered, pushed the barber out of the way, and shot him repeatedly until he fell to the floor, dead. Obviously a gangland killing, but no one was ever indicted.

Such violence was alien to mild-mannered Willie, who deplored Arnold Schuster's murder. After his 1952 arrest he was convicted of robbing a bank in Queens and given a sentence of 30 to 120 years in Attica State Prison. This time he didn’t escape. Always ready to give legal advice to other inmates, he was known by them as “a wise old head.” In December 1969 his good behavior and deteriorating health due to emphysema led a judge to commute his sentence to time served. “Thank you, your Honor,” said Willie. “God bless you.” He wept as he was led out of the courtroom. Released on parole, he gave lectures on prison reform, advised banks on how to prevent robberies, and starred in a TV commercial for a bank’s new credit card. He spent his last years with a sister in Florida, died there in 1980 at age 79, and was given a quiet burial in a family plot in Brooklyn. How the family felt about his professional career I haven’t discovered.

The famous quote about robbing banks "because that’s where the money is" has often been quoted and is known as “Sutton’s law." Yet Willie claimed he never said it and attributed it to some enterprising reporter in need of more copy. Why then did he rob banks? “Because I enjoyed it,” he says in his 1976 autobiography. “I loved it. I was more alive when I was inside a bank, robbing it, than at any other time in my life.”

Gangland killings: Such killings were once common in Brooklyn and elsewhere, but we like to think of them as bad memories from the distant past, inconceivable in our more enlightened age. But the Times of July 2 reported that Louis Barbati, the owner of a Brooklyn pizzeria, was shot five times and killed by an assassin, his face hidden in a hoodie, who was waiting for him as he came back from work to his house in Dyker Heights in southern Brooklyn. His flash jewelry, cash, and other valuables were not taken, which seems to refute the police’s initial assumption that the shooting involved a robbery gone wrong. Complicating matters was his feud with a former employee who stole the secret recipe for his sauce and opened a pizzeria on Staten Island. The police are investigating, as well they might. But in today’s somewhat gentrified Brooklyn, renowned for its hipster culture, this seems like a troubling throwback to the past.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received two awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction, and first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. (It also got an honorable mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards, but that hardly counts.) As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Coming soon: Tammany, the Tiger Whose Claws Got Clipped. But before that, in midweek, maybe reblog of another popular post.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on July 10, 2016 04:18

July 6, 2016

241. Francis J. Spellman, the Controversial Cardinal

Cuddly and cherubic? Appearances

Cuddly and cherubic? Appearancesdeceive.This post is a reblog of post #136, published on July 20, 2014. Of all the posts in this blog, it has the most views, surpassing even Man/Boy Love.

He was born to an Irish American family in Massachusetts in 1889, as a child served as an altar boy, graduated from Fordham in 1911, decided to study for the priesthood, and was sent to pursue those studies in Rome. Ordained in 1916, he returned to the U.S. and did pastoral work in Massachusetts, but was unable to become a military chaplain during World War I because he failed to meet the height requirement. Other posts followed, including U.S. attaché of the Vatican Secretariat of State in 1925. He was in Rome from 1925 to1931, where he made useful contacts in the Curia, and in 1927, during a trip to Germany, he began a lifelong friendship with Eugenio Pacelli, then the papal nuncio to Germany. Named Auxiliary Bishop of Boston in 1932, he had strained relations with his superior, Archbishop O’Connell of Boston, but did further pastoral work in Massachusetts, and in 1936 helped arrange a visit by Pacelli, now the Vatican’s Cardinal Secretary of State, to these shores, where he countered the influence of the Detroit-based Father Coughlin, whose popular nightly radio broadcasts were harshly critical of President Roosevelt. But the real reason for the visit was to meet secretly with the President and discuss establishing diplomatic relations between the U.S. and the Holy See; Spellman was present at the meeting, though no formal diplomatic ties resulted at this time. It should be clear by now that Francis J. Spellman had a genius for making the right connections almost from the start of his career.

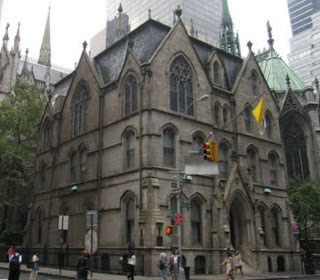

In 1939 Pope Pius XI died, to be succeeded by Pacelli as Pius XII. One of the new Pope’s first actions was to make Spellman Archbishop of New York and vicar of the U.S. armed forces, just in time for World War II. The new Archbishop moved into the archiepiscopal residence, a handsome neo-Gothic structure at 452 Madison Avenue, at the corner of 51st Street, adjacent to Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, where he would reside for the rest of his life amid oak paneling, thick red carpets, ornate furniture, priceless antiques, and a quiet almost unheard of in busy midtown Manhattan.

Spellman was soon exerting great influence in religious and political matters

and hosting prominent figures of the day like Joseph P. Kennedy, the Wall Street speculator turned Securities and Exchange Commission chairman turned Ambassador to Great Britain (and, incidentally, another Massachusetts-based Irish Catholic), and financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch. Clearly, he had a genius for relating to the rich and powerful. Once the U.S. entered the war, His Eminence supported the war effort vigorously. In 1943 President Roosevelt sent him as his agent to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, where the peripatetic Archbishop covered 16 countries in 4 months, rivaling the whirlwind tours of American tourists of the postwar era; he met with Franco in Spain, the Pope in Rome, and Churchill in London, and on his return to the U.S. helped arrange to have Rome declared an open city and thus spared further bombing. Roosevelt’s death in 1945 diminished his influence in higher circles, but after the war Pius XII made him a cardinal in 1946, just in time for the Cold War. As always, Spellman’s timing – or was it just dumb luck? – was flawless. And he was impressive to behold in his scarlet cardinal’s robes.

and hosting prominent figures of the day like Joseph P. Kennedy, the Wall Street speculator turned Securities and Exchange Commission chairman turned Ambassador to Great Britain (and, incidentally, another Massachusetts-based Irish Catholic), and financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch. Clearly, he had a genius for relating to the rich and powerful. Once the U.S. entered the war, His Eminence supported the war effort vigorously. In 1943 President Roosevelt sent him as his agent to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, where the peripatetic Archbishop covered 16 countries in 4 months, rivaling the whirlwind tours of American tourists of the postwar era; he met with Franco in Spain, the Pope in Rome, and Churchill in London, and on his return to the U.S. helped arrange to have Rome declared an open city and thus spared further bombing. Roosevelt’s death in 1945 diminished his influence in higher circles, but after the war Pius XII made him a cardinal in 1946, just in time for the Cold War. As always, Spellman’s timing – or was it just dumb luck? – was flawless. And he was impressive to behold in his scarlet cardinal’s robes.In the years that followed – the years when I first became aware of him – Cardinal Spellman showed that, much as he loved the red of the cardinal’s robe, he loved the red, white, and blue just as much. “A true American can neither be a Communist nor a Communist condoner,” he declared. “The first loyalty of every American is vigilantly to weed out and counteract Communism and convert American Communists to Americanism.” Needless to say, he was a fervent supporter of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who without offering hard evidence had the public believing that there were Communists in every nook and cranny of the government, and that -- as I heard the Wisconsin senator say once on television, ever so convincingly – the world was going up in flames. The politics of fear, always effective.

In 1949, when the gravediggers of Calvary Cemetery, a Catholic cemetery in Queens, went on strike for a pay raise, he called them Communists, labeled their action an immoral strike against the innocent dead, recruited seminarians as strikebreakers to dig graves, and set them a vigorous example in that worthy activity. In that same year he locked horns with former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, when in her newspaper column “My Day” she opposed federal funding to parochial schools. He accused her of anti-Catholicism and “discrimination unworthy of an American mother,” though in time he met with her and made peace. But peace was not his prime concern; he was too busy denouncing immoral Hollywood films and, in time, comedian Lenny Bruce, who had often satirized the Cardinal.

Arrested in 1961, one of his many arrests. The irreverent comedian, who was no stranger to obscenity, sometimes imagined Christ and Moses returning to earth to observe people in East Harlem crammed 25 to a room, and then notice the Cardinal’s ring, worth ten thousand dollars. Or the two visitors would enter Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, followed by lepers whose flesh was falling on the polished floors, causing His Eminence to phone Rome in a panic and tell the Pope to put the holy duo up, since he was up to his ass here in crutches and wheelchairs. Admittedly, Bruce was breaching the limits allowed to comedy in America; jibes at religion were risky, and out-and-out obscenity taboo. No wonder the Archbishop encouraged the D.A., another Irish Catholic, to charge Bruce with obscenity. Bruce was convicted after a controversial and widely publicized six-month trial in 1964 and sentenced to four months in a workhouse, but was set free on bail pending an appeal. He died of an overdose in 1966 before the appeal had been decided, and in 2003 received a posthumous pardon, the first in New York State, from Governor George Pataki.

Arrested in 1961, one of his many arrests. The irreverent comedian, who was no stranger to obscenity, sometimes imagined Christ and Moses returning to earth to observe people in East Harlem crammed 25 to a room, and then notice the Cardinal’s ring, worth ten thousand dollars. Or the two visitors would enter Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, followed by lepers whose flesh was falling on the polished floors, causing His Eminence to phone Rome in a panic and tell the Pope to put the holy duo up, since he was up to his ass here in crutches and wheelchairs. Admittedly, Bruce was breaching the limits allowed to comedy in America; jibes at religion were risky, and out-and-out obscenity taboo. No wonder the Archbishop encouraged the D.A., another Irish Catholic, to charge Bruce with obscenity. Bruce was convicted after a controversial and widely publicized six-month trial in 1964 and sentenced to four months in a workhouse, but was set free on bail pending an appeal. He died of an overdose in 1966 before the appeal had been decided, and in 2003 received a posthumous pardon, the first in New York State, from Governor George Pataki.The Cardinal that I knew from photos at the time showed a portly, spectacled, jowly prelate whom some thought cherubic and humble (I would have said a cuddly, well-fed little porker), a man with a ready smile but perhaps not too bright. But behind this façade was a shrewd, almost ruthless player on the world stage who had no qualms about fighting, and fighting hard, to get what he wanted. A longtime Jesuit friend and his official biographer described him as “fearless, tireless, and shrewd, but at the same time humble, whimsical, sentimental, incredibly thoughtful, supremely loyal, and, above all, a real priest.” A complex individual, then, a seeker and wielder of power whom others playing the same game had to take into account and respect. But also a tireless worker, a skillful administrator, a shrewd negotiator of real estate deals, and an excellent fund-raiser – in short, a first-rate businessman. And a poet and novelist, his novel The Foundling coming out in 1951. But not one to admit error or to give up an opinion, no matter now outdated or unpopular; prudence was unknown to him.

A participant in the 1958 papal conclave that elected Pope John XXIII, Spellman, though a conservative, was in some ways progressive, insisting on a declaration on religious liberty, yet in the long run he was critical of the new Pope’s liberal and reformist leanings. “He’s no Pope,” he reportedly said. “He should be selling bananas.” In the following year, during a visit to Central America, he disobeyed the Pope’s instructions by appearing in public with Anastasio Somoza Garcia, the right-wing dictator of Nicaragua, of whom President Roosevelt had once allegedly remarked, “He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.” (There is some doubt as to which Latin American dictator he was referring to.)

In the 1960s the escalation of the Vietnam War, and the eruption of antiwar protests on college campuses across the country, brought new opportunities for the zealously patriotic Cardinal and his critics. So outspoken was His Eminence’s support of the war that protesters labeled it “Spelly’s War.” He spent the Christmas of 1965 with the troops in South Vietnam, said Mass in Saigon, sprinkled holy water on B-52 bombers and blessed them just before they departed on a mission, and described the war as “Christ’s war” and a “war for civilization.” This did not go over too well with the Vatican, since Pope Paul VI had urged negotiations and an end to the war; sources made it clear that the Archbishop spoke only for himself, not for the Pope or the Church. Back home, where humorous buttons were now all the rage, one saying DRAFT CARDINAL SPELLMAN was popular, and in January 1967 war protesters disrupted a Mass in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral.

University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1965.

University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1965.uwdigitalcollections

In 1966, when Pope Paul initiated a policy whereby bishops would retire at age 75, Spellman, then 77, offered to resign, but the Pope asked him to remain at his post. He died in December 1967, of what has not been disclosed. His funeral was attended by President Lyndon Johnson, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, New York State Senators Robert Kennedy and Jacob Javits, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, Mayor John Lindsay, and others, and he was buried in the crypt under the main altar of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, alongside other deceased archbishops and cardinals. No question, he went out in style. His 28-year tenure as Archbishop is the longest to date in the history of the Archdiocese of New York. A New York City high school bears his name.

Cardinal Spellman's coat of arms.

Cardinal Spellman's coat of arms.Sequere deum = Follow God.

SajoR

And now we come to the crucial question: Was Cardinal Spellman gay? Rumors then and now have abounded. A friend informs me that in the standees line at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1950s gay jokes about “Franny” Spellman were rampant, especially among standees with a Catholic upbringing, though all the ones he remembered are too bawdy to bear repeating here. I’m always skeptical about such stories, until conclusive evidence appears. Some elements of the gay community commonly assert with conviction that this or that world leader or celebrity is or was screamingly gay, without offering any such evidence. Long ago a dapper Brooks Brothers-clad East Sider who had been in the military in the Pacific during World War II assured me that reports of General Douglas MacArthur’s homosexual escapades had constantly surfaced and of course had been vigorously suppressed. I didn’t believe him then and I don’t believe him now, since I know of no reliable confirmation of his story. But the case of Cardinal Spellman isn’t that simple.

One of Spellman’s biographers, John Cooney, whose workThe American Pope: The Life and Times of Francis Cardinal Spellman appeared in 1984, mentioned four interviewees who stated that Spellman was indeed homosexual; Cooney offered no direct proof but was convinced that the allegations were true. “I talked to many priests who worked for Spellman and they were incensed, dismayed, and angered by his conduct.” Not surprisingly, Monsignor Eugene V. Clark, Spellman’s personal secretary for fifteen years, promptly labeled Cooney’s accusations “utterly ridiculous and preposterous,” adding that "if you had any idea of [Spellman's] New England background and his Catholicism, you would know it was a foolish charge." (Interestingly enough, Clark, an arch-conservative who was notoriously anti-gay in his pronouncements, had to resign as rector of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in 2005 when, at age 79, he was named as the “other man” in a divorce case.)

Signorile

SignorileDavid Shankbone Reinforcing Cooney’s claim is gay author and journalist Michelangelo Signorile’s online article “Cardinal Spellman’s Dark Legacy” (2002), which labels Spellman “one of the most notorious, powerful, and sexually voracious homosexuals in the American Catholic Church’s history.” According to him, the closeted Cardinal was known as “Franny” to assorted Broadway chorus boys and others, but the Church pressured Cooney’s publisher, Times Books, to reduce the four pages on the Cardinal’s sexuality to a single paragraph that only mentioned “rumors.” Signorile also asserts that Spellman was involved in a relationship with a dancer in the Broadway revue One Touch of Venus, whose original production ran from 1943 to 1945; Spellman would have his limousine pick up the dancer several nights a week and bring him to the archiepiscopal residence. And if a portly prelate might seem lacking in sex appeal to a frisky chorus boy, his status as the Cardinal Archbishop of New York probably enhanced his image considerably. All of which prompts a titillating nocturnal fantasy: the young man exiting the limousine discreetly and slipping into the neo-Gothic mansion, with its ornate furnishings and uniformed servants, for a most clandestine tryst. When he asked Spellman how he could get away with it, His Eminence allegedly answered, “Who would believe that?” It should be noted that Signorile has made a name for himself by “outing” public figures whom he claims are closeted homosexuals, a practice that is highly controversial and will be discussed in the next post.

Further complicating the picture is Curt Gentry’s biography J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (1991), which alleges that Hoover’s files had “numerous allegations that Spellman was a very active homosexual” (p. 347). Still, these are only allegations. Surprisingly, thanks to a Freedom of Information Act request, the FBI’s declassified file on Spellman is available online and I have looked at it. Unsurprisingly, what are probably the most informative and juicy parts are blacked out. So what do we learn? Here is a sample from the 1940s:

· A letter of June 16, 1942 to Hoover (signature deleted) giving him the names of all those attending a luncheon at the Archbishop’s residence on June 11, 1942, with all those names blacked out.

· A letter of June 21, 1942, to Hoover from Spellman’s office (signature deleted) saying that the sender is glad he enjoyed the luncheon, and that the Archbishop has confirmed his standing invitation to Hoover to lunch at the Archbishop’s residence whenever he is in New York.

· A letter of November 30, 1942, from Spellman to Hoover congratulating him on “your twenty-five years of devoted, patriotic, successful service to the country in the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” and Hoover’s appreciative reply on December 10, 1942.

· A letter to Hoover from Rome (signature deleted) of February 7, 1946, noting that Spellman will arrive in Rome on February 14 to be consecrated a cardinal by Pope Pius XII. The writer believes it will be of interest to the Bureau to know that there is speculation in Vatican circles and the Roman public at large regarding Spellman’s perhaps being appointed Papal Secretary of State, a position giving the recipient a better than average chance of being elected Pope. Feeding the speculation is the fact that Pius XII is said to be tubercular and in poor health generally. [Spellman was indeed offered the position but turned it down.]

So what have we learned? About homosexuality, nothing; if there are any files mentioning it, they must still be classified. The letters show Spellman and Hoover exchanging cordialities, and His Eminence and others keeping the Director well informed about Spellman’s activities and a possible significant appointment. Spellman was careful to maintain friendly ties with Hoover, and Hoover was keeping track of Spellman’s career. Which shows how powerful people deal with one another, and that in itself is hardly surprising or shocking.

But does this exchange of cordialities mask another game? If Hoover reportedly had a file on President Kennedy's sexual escapades and was quite willing to use it as blackmail to get what he wanted from the Kennedys, he would surely have had a similar file on His Eminence's escapades, if such there were. If so, this unclassified file shows the Archbishop making nice with J. Edgar for the best of reasons: to flatter him and lessen the chance of any embarrassing revelations from that quarter. In 1972, when Hoover at last relinquished his position and power through death, many a public figure must have clandestinely sighed with relief.

Certainly it is in the Church’s interest to squelch, whenever possible, even rumors or allegations about His Eminence’s sexual proclivities. After all, what would happen if the charges turned out to be true? Would the Cardinal Spellman High School have to be rechristened? Would His Eminence’s remains have to be disinterred from under the main altar of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, and if so, where should they go? Messy, messy, messy. But if he made a full confession on his deathbed, probably it wouldn’t be necessary. Who among us has not sinned? Still, messy in the extreme.

So what do I conclude? Was Cardinal Spellman gay? Possibly. Monsignor Clark's argument citing Spellman's New England background and Catholicism doesn't impress me, since I have known, and known of, gay men raised in a very traditional Catholic environment who, but for their sexuality, would have been classic conservatives in life style, politics, and religion, and who sometimes, with great anguish but without success, tried to be so anyway.

Is Spellman's homosexuality absolutely certain? No. Is it probable? I haven’t quite decided. What would nudge me toward “probable”? If one or several ninety-year-old ex-chorus boys surfaced and announced, “Yes, I had sex with His Eminence back in the 1940s,” that might do the trick. In the meantime I’ll only say, Where there’s smoke, there’s fire. But given the specificity of the charges, the more I ponder, the more I edge toward “probable.” Yes, he probably was. [Today, upon further reflection, I would say almost certainly.]

So what is one to make of all this? I don't share the opinion of Michelangelo Signorile, who labels Spellman "the epitome of the self-loathing, closeted, evil queen," for no known facts substantiate the statement. We have no glimpse into the inner workings of the archbishop's mind. Perhaps his sex life was high drama or even tragedy, perhaps it was comedy laced with farce, perhaps it was something in between; we will probably never know.

Contact with the rich and famous, luncheons with J. Edgar, a confident of three presidents, a strike-breaking gravedigger, a white-hot patriot who went against papal pacifism to bless departing bombers, and posthumously the subject of a passionate controversy – what a career! They don’t come like that very often.

A Spellman quote: “There are three ages of man – youth, age, and ‘you’re looking wonderful.’ ” So he did have a sense of humor.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received two awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction, and first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. (It also got an honorable mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards, but that hardly counts.) As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Coming soon: As announced, a celebrated bank robber who often brandished a submachine gun but wouldn't hurt a flea.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on July 06, 2016 05:52

July 3, 2016

240. Gay Pride, Anaïs Nin, and Erotica

Though I always take out my rainbow flag (scavenged from a trash can last year) and wave it about the apartment, I hadn't planned to watch this year's parade, having seen it several times in the past. Instead, knowing the nearby restaurants would be crowded even while the parade was in progress, I planned to take refuge in a quiet Chinese restaurant on West 3rd Street, at a safe remove from the brouhaha. So I left the apartment at about 2 p.m. and went out into a mild, cloudless day – perfect for a parade. I planned to follow West 4thStreet east to Sixth Avenue and, depending on the volume of the crowds, find my way from there. Which, it turned out, was naïve.

Walking along West 11th Street toward 4th, I immediately encountered a group of girls, one of whom, with flaming pink hair, launched into a frenzied dance. As I passed them I applauded, and her companions cheered my applause. Which set the tone for the day: wild and joyous.

As I followed West 4th toward Sheridan Square, where West 4thintersects Christopher Street and the path of the parade, I soon saw a mass of people ahead of me blocking my way to Seventh Avenue and the Square, so I turned left onto West 10th Street (yes, West 4th crosses West 10th – this is the Village and even the streets are crazy) – and, with the help of police who were directing traffic and the flow of pedestrians, managed to cross Seventh Avenue, then Sixth, where I found the crowds still impossibly thick, then Fifth, still crowded, and ended up on University Place, far removed from the parade, where I found only the usual Sunday-afternoon crowd enjoying the Village on a sunny day, fewer rainbow flags, less frenzy. So what had I seen en route? Not just rainbow flags, but flaring rainbow skirts, rainbow boas, rainbow capes, rainbow necklaces and bracelets and shirts and caps and headdresses – in short, rainbow everything. And T-shirts blazoning a message:

IT’S ALL ABOUT LOVELOVE WINSMANILA – PHILIPPINES

And on a very straight-looking guy:

YOU’REABITCH

And the people? Policemen everywhere (in the wake of Orlando, no doubt), and firemen and their vehicles as well. As regards the celebrants, mostly young people waving rainbow flags, but also older ones, some of them same-sex couples holding hands. Muscled studs stripped to the waist, displaying the torso they’d worked so hard to achieve. And women with pink, purple, blue, or yellow hair. And, here and there, costumes wild and weird, as if from another planet, indescribable. But nothing negative; a joyous mood throughout, albeit with signs – I AM PULSE, WE ARE ORLANDO -- commemorating Orlando and the 49 victims.

As I approached my Chinese restaurant, I grew apprehensive, for even on West 3rd Street there were ground-floor bars and restaurants jammed to the gills, with occasional cheers and applause, probably sparked by watching the parade on television. But when I mounted the short flight of stairs to my restaurant, I left the hullabaloo behind and entered a sheltered space of calm with only a handful of other patrons present. I was soon at a table awaiting my scallion pancakes and tea, while perusing a book I had just bought at a sidewalk stand on West 4th Street and University Place: Delta of Venus: Erotica by Anaïs Nin (Bantam, 1978), which made available to the public some erotica that, needing money, she had done in 1940 for an anonymous male patron for a dollar a page. And who had put her up to this endeavor? Her friend and lover, Henry Miller, who had other projects in mind and so offered the job to her. (Note: In 1940, a dollar a page wasn’t a bad rate. Accounting for inflation, it is the equivalent of $16.89 today.)

Though I have read Ovid’s Ars Amatoria (Art of Love) in Latin and, in translation, a similar treatise in Arabic, I’m not much into erotica, whether gay or straight. I bought the book on an impulse, because I had met Anaïs Nin here in New York in 1968, at which time I sent her some poems (she pronounced them “subtle”), and she sent me A Spy in the House of Love, a title that I still find arresting. But what does this have to do with Gay Pride? Nothing, yet everything, for a candid celebration of female sexuality signals the same emancipation for women that the Stonewall riots of 1969 signaled for the gay community. What is the Gay Pride celebration all about, if not a celebration of sex? While at the restaurant I got through the first chapter, about a fictional Hungarian baron whose appetite for sexual adventures is satisfied – for a while – by a free-living Brazilian dancer name Anita whose narrowed, lascivious eyes resembled those of a tiger, puma, or leopard. (To my knowledge Anaïs Nin had no close acquaintance with feral felines, but her imagination was surely piqued by the thought of $16.89 a page.)

Yes, this is erotica, but today it lacks the shock value that it must have delivered when first published long ago. And the Anaïs Nin that I met back then had nothing loose or rakish about her; she was very much a lady, carefully got up, petite, soft-voiced, sensitive, articulate. Her preface tells how, when she was writing the erotica, her patron urged her to “leave out the poetry,” which she found that she couldn’t do. In addition, she realized that feminine erotica, unlike male, couldn’t focus on sex acts alone, but required a component of emotion and love as well – a realization that made her work more challenging, even difficult. Men and women, she saw, were put together differently and required different stimuli for arousal. Henry Miller’s accounts of sexual experience were explicit, hers were ambiguous; his were Rabelaisian and humorous, hers were poetic. As a woman writing erotica – a genre hitherto dominated by men – she was a pioneer. (For an account of my brief acquaintance with Anaïs Nin, see post #133, June 29, 2014.)

This account of my Gay Pride Day peregrinations left me at the restaurant with my nose deep in the delta of Venus, but having finished my digression on erotica, I’ll get back to me and my further adventures. What then happened was simply my attempt to brave the commotion and get back home in one piece. I followed West 4thback across Sixth Avenue (no problem), and then traversed the West 4thblock between Sixth and Seventh which I have already commemorated in a much-visited post for this blog (#154, November 23, 2014). When I reached Sheridan Square, the whole area was packed, and the parade was in progress on Christopher Street, passing the celebrated Stonewall Inn on its way to Seventh Avenue and beyond. From a distance I could see, over the heads of other bystanders, several floats pass by, blaring loud music to which a pack of young celebrants, some in fantastic outfits and some in almost nothing at all, vibrated frantically and joyously. Each time a float passed the crowd at or near the Square, a huge ovation erupted, while everyone waved their rainbow flags in a frenzy. And in the park itself the life-size statues of two couples, two men standing together and two seated women, were still heaped with flowers and cards and candles commemorating the victims of the Orlando massacre.

At intervals the police halted the parade and let people cross Christopher Street, so I was able to escape north from the crowd and reach West 10th again, which took me back to West 4thand so on to my apartment. The more space I put between me and the parade, the less frantic the crowd and the fewer the flags, until the crowd frayed into small groups here and there, including some, both old and young, content to sit on a stoop and watch the others go by. But right up to the entrance to my building, I sensed excitement in the air, something very special under way. So ended my witness of the celebration, except for sounds that night of fireworks.

Today the Times informs me that some 30,000 marched in the parade, and that Hillary Clinton made a surprise visit, popping out of a van near the Stonewall to march four blocks in the parade in the company of such notables as Governor Cuomo, Mayor de Blasio, and black activist Al Sharpton, who took care to position himself right next to the lady in question. Recognized and hailed all the way, and showered with confetti from a rooftop at Bleecker Street, she waved and smiled and shook hands with onlookers held back by police barricades. Then, just as suddenly and mysteriously as she arrived, she popped back into a vehicle and was whisked off to fly back to Indiana, where she is now campaigning. Mr. Trump, who claims he will do more than Hillary for gays, was not in evidence, having other fish to fry.

TheTimes also interviewed some bystanders. A young man from Bangkok had thought about dressing in drag but decided not to, heeding his mother’s advice, “Just don’t go crazy.” A 20-year-old transgender American said he felt proud of being who he was, but declined to give his surname because his family disapproved of his transition. And a 74-year-old American who has attended some 30 marches told of losing 75 friends to AIDS; when he informed the families, some of them immediately hung up, so he deposited their ashes in the Hudson River and the Grand Canyon: a sad note indeed on an otherwise joyous occasion.

Erotica vs. pornography: What is the difference? Off the top of my head I’m inclined to say that erotica deals candidly with the sexual, but pornography goes further, dishing out luscious adjectives and juicy descriptions in hopes of sexually arousing the reader or viewer. Ovid’s Ars Amatoria is certainly not pornography; rather, it’s a sex manual instructing male and female readers on how to “connect” and, once you’ve done it, how to keep connected. His advice is often simplistic, yet relevant: “To be loved, be lovable.” He arms his readers for sexual encounters, but he doesn’t whip them up into a frenzy of desire.

Throughout the book Ovid is urbane, sophisticated, witty. Which did him no good whatsoever: in 8 CE he was banished by the emperor Augustus to the farthest limits of the empire (to what is now Romania) because, as the poet puts it, he was guilty of a book and an error. The book was obviously the Ars Amatoria, which may have offended an emperor eager to restore the traditional polytheistic religion of Rome, and opposed to well-bred Roman women going out in public to “connect.” The error may have been political, related to rival factions intriguing to secure the aging emperor’s succession; possibly it involved the emperor’s granddaughter Julia, who was banished for adultery in the same year and subsequently bore a child that Augustus ordered put to death. Neither Julia nor Ovid ever got back to Rome.

The Ars Amatoria was burned in a bonfire of vanities by the fanatical Florentine monk Savonarola (who later himself got burned), and an English translation of it was seized by the U.S. Customs in 1930. One wonders what happened to the confiscated copy, and who got to read it.

Even more taboo in the U.S. was Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, recounting his sexual adventures and misadventures in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. It was first published in Paris in 1934 with financial help from Anaïs Nin. When I went to France on a Fulbright years later, a friend asked me to bring back a copy, since it was banned in the U.S. but available in France. I did as he requested and in the process stuck my nose into it and, far from being aroused sexually, roared with laughter. It was funny, funny, funny, at times uproariously so. A Supreme Court ruling in 1964 declared the book “non-obscene,” ending the longtime ban; I hope the justices enjoyed their reading.

Obviously, the line between erotica and pornography is hazy at best; one man’s erotica is another man’s porn. But I hold to my opinion that porn is different in that it is a no-holds-barred effort, not to entertain or enlighten the reader, but to stimulate him (almost always a “him”) sexually. And does it find its audience! Forbes estimates that in this country the porn industry grosses from $10 to $14 billion a year. Neither Henry Miller nor Anaïs Nin ever dreamed of realizing even a tiny fraction of such a sum, nor did Ovid either, I suspect; if they had, they might have done better financially, but we would be poorer literarily. So it goes.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received two awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction, and first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. (It also got an honorable mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards, but that hardly counts.) As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Coming soon: A reblog of post #136 on the very controversial cardinal Spellman (was he or wasn’t he?), the post with the most views of all in this blog, topping even Man/Boy Love. Then, as originally announced, a celebrated bank robber who preyed on the city’s banks for 40 years, escaping from prison three times. A rather charming, gentlemanly fellow who, even when brandishing a submachine gun, wouldn’t hurt a flea. Alas, they don’t make thieves like that any more.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on July 03, 2016 04:59

June 28, 2016

239. Man/Boy Love: The Great Taboo

[This post is a reblog of post #43, the most visited of all the posts in this blog, originally published on January 20, 2013. The comments that followed are included. It does not appear in my book (see below), because Mill City Press feared legal complications -- a concern that I think exaggerated, since I do not promote (or condemn) these relationships, but above all want to understand them. My friend Joe is now out of prison and doing well; he is on good terms with Allen, though they are now only friends.]

When our friend John came to visit Bob and me recently, he asked an interesting question: “Have you ever held a strong opinion about something and then, in the course of time, come to hold the opposite opinion? In other words, regarding something significant, have you ever changed your mind?” The three of us pondered but came up with nothing. But I had a sort of answer (“sort of” because my first opinion was not a firm, well-settled one): I once had a mild, rather passive opinion and later came to a distinctly strong opposite opinion. The subject: man/boy love. Which brings us to this post, a departure for three reasons: (1) it is not specific to New York; (2) it may seem like advocacy, though I mean only to relate my own change of opinion on the subject; (3) the subject being controversial, it may raise a few hackles.

I myself have never experienced man/boy love, neither as the younger partner nor the older one, or felt any urge to do so. When, long ago, I would at times encountered a gay teenager who was obviously eager to connect, he was always too immature to interest me. So my attitude toward such relationships was vague, casual, and rather orthodox: if the boy was under the age of consent and therefore "jail bait," such a relationship was dangerous, probably dubious, and best avoided. Yet man/boy love has been documented and even illustrated in many cultures, so graphically, in fact, that I wouldn't dare show some scenes from Pompeii, or certain Japanese and Chinese works, lest my blog be labeled a porn site. And in classical myth Zeus became so enamored of the beautiful young Trojan boy Ganymede that he whisked him off to Olympus to be the cupbearer of the gods. (How Hera felt about this is not recorded.) But for me such love was even more remote than Olympus, so I didn’t think much about it.

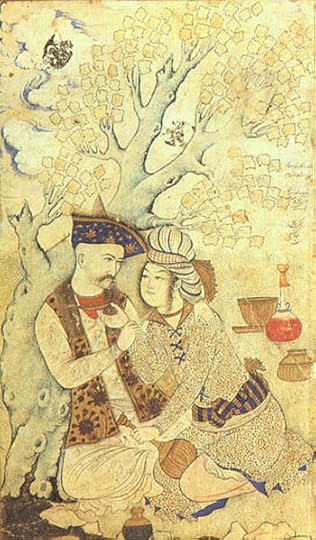

[image error] A sheikh and a youth partying in a garden: a Persian painting of 1530. Does this suggest man/boy love? Viewers can decide for themselves. What changed? In July 2000, having heard of his case on GrandpaAl Lewis’s WBAI program (see post #19), I wrote to an inmate in North Carolina named Joe and initiated a pen pal correspondence that continues to this day. Joe, I learned, was serving 25 years in prison on 25 counts each of indecent liberties with a child and crime against nature, and could hope to be released sometime in 2014. “Crime against nature” – the very term angered me. Against what nature, whose nature, etc.? But be that as it may, Joe at my request gave me a streamlined account of his consensual three-year relationship with a young teenager named Allen (a fictional name) and how it led to his arrest.

Another Persian work: Shah Abbas and a wine boy. Shah Abbas ruled Persia 1587-1629. This one is even more suggestive. What was going on in ancient Persia?

Another Persian work: Shah Abbas and a wine boy. Shah Abbas ruled Persia 1587-1629. This one is even more suggestive. What was going on in ancient Persia?Fascinated by Joe’s story, I urged him to write his memoir, telling in detail the entire story from beginning to end. (Not that it has an end; it is still ongoing.) Though he had never written anything before, with my help he set out and over many months, sending me periodic installments, told his story in three sections: My Life before Allen, My Life with Allen, Locked Up. Because of his remarkable memory for detail and his skill in description, it reads like a novel: a gripping and very moving novel. He will self-publish it when released, so as to give his version of the story, totally at odds with the statements of the prosecutor at his sentencing hearing. (With great effort I obtained the official court record of the proceedings, so I know exactly what misstatements and falsehoods were uttered.) Clearly, this three-year man/boy relationship was doing no harm to anyone until other parties interfered, and the heavy-handed criminal justice system brought trouble to all concerned.

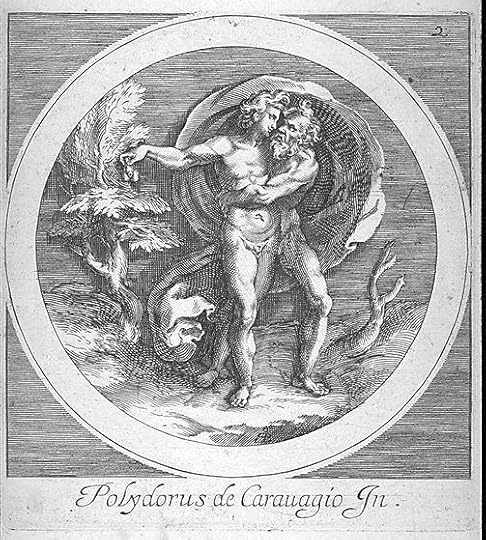

Zeus embracing Ganymede, an engraving by the Italian artist Cherubino Alberti (1553-1615), based on a work by Polidoro da Caravaggio (not to be confused with the famous Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio). Some versions describe what Ganymede is holding in his right hand as a purse, suggesting prostitution, but Ganymede didn't need money; closer inspection reveals it to be the male genitals!

A story within a story: In his memoir Joe tells how, when working as a counselor in a boys' camp, one of the boys -- we'll call him Jim -- told him an interesting story. A man moved into his neighborhood who started having consensual sex with the local underage boys. Word got around; the boys flocked. Jim himself had sex with the man, as did his younger brother. But one day the police came calling: word had reached them too, and they wanted Jim to testify against the man, so this predator could be locked up. Jim didn't want to, but under great pressure he agreed. In court he saw the man, now in custody, and realized that the whole case against him depended on Jim's testimony. But Jim reflected: he liked the man, liked the sex, and didn't think the man would harm anyone. So when he took the stand, he testified that he and the man had never had sex. Pandemonium erupted, as the prosecutor and a social worker upbraided him, and the judge pounded his gavel for order. The session was suspended, so the social worker could talk to Jim in private, with only his father present. The social worker again described the man as a monster and said it was Jim's duty to testify against him so he could be locked up. "Lady," said Jim, "right now I'm more scared of you than I am of him!" Her jar dropped, and Jim's father intervened: "If you don't mind, I'm taking my son home." For the next few days his father kept a close eye on Jim, lest he see the man again, but the man soon moved away. This story taught me something useful: It isn't enough to just tell the truth; you must tell it for the right reasons. Jim lied in his testimony, but to have told the truth would have gone counter to his own perceptions of the situation and betrayed a man who he felt had done him no harm. Few teenagers would have had the courage to do this; I applaud him.

Obviously, it was Joe’s story that caused me to reconsider my attitude toward man/boy relationships and the notion of the pedophile and pedophilia, terms that are used – and misused – much too freely. Webster’s New Collegiate defines pedophilia as “sexual perversion in which children are the preferred sexual object.” In this context I take “children” to mean young persons who have not yet reached puberty. In the recent scandals regarding priests in the Catholic Church, the perpetrators were invariably referred to as pedophiles, though most of the cases involved teenagers. We lack a term for sexual attraction to adolescents – “ephebophilia” exists but has

not passed into the general language – hence the misuse of “pedophile” and “pedophilia.” Joe was 26 and Allen was 13 when they met, but at 13 Allen was tall, rather broad-shouldered, and well past puberty, so for me this story does not involve pedophilia.

Man/boy love in ancient Greece. An Attic vase of the 5th

Century BCE, now in the Louvre. Ah, those Greeks! In

pre-Christian times they got away with a lot,

incorporating ephebophilia into their societies, on

condition that the partners in time marry and beget

offspring, so as to assure the future of the city state.

Marie-Lan Nguyen

My interest in Joe’s story led me to two books treating the subject of man/boy relationships, one studying the problem in Denmark and the other in Holland, but both now available in English. The Danish one, originally published in 1986, offers interviews with a defense attorney, a judge, admitted pedophiles, and above all a number of boys involved in consensual relationships. One boy, who says he isn’t exclusively gay, asserts that it would be boring to be purely heterosexual. A boy of ten (the youngest of those interviewed), when asked how old a person should be before having sex, replies, “Zero years”; his mother, aware of the relationship and her son’s love for his older friend, refuses to interfere, and regrets that the relationship has to be hidden from the outside world. Another boy describes himself as bisexual, deriving great pleasure from sex with girls, though he says his best experiences were with his stepfather, when he could just surrender and let the stepfather take the lead. Finally, a boy of 16, now interested in girls, says of the older friend whom he started having sex with at age 13, “He understands me better than my own mother”; he expects that, even without sex, they will remain friends indefinitely. The aim of the study, the authors say, is to induce parents, teachers, and the various authorities to listen to what the boys say, and to understand their joy in the relationships and their need of an older friend. Significantly, just as the boys reach 15 or 16, their older friends lose interest in them sexually, and the boys usually begin having sex with girls. Significantly too, the English translation’s title is Crime Without Victims.

First published in 1981, Theo Sandfort’s Dutch study was based on a government-funded report examining the stories of twenty-five boys currently involved in a consensual man/boy relationship, all but one of whom considered the relationship a decidedly positive experience. When, before the AIDS epidemic appeared, a limited English edition reached these enlightened shores, it was reviewed by a pediatric psychiatrist inContemporary Psychology (vol. 30, no. 1, 1985), who dismissed it as the rationalizing of a criminal activity, tainted both because it avoided the usual labels of "victims" and "perpetrators," and because it was sponsored in part by an organized group of pedophiles (which was news to the Dutch government!). Circulating here at the same time was the accusation (never substantiated) that a tidal wave of "kiddie porn" was flowing across the Atlantic from Amsterdam; those permissive Dutch were trying to corrupt our youth and undermine the moral fabric of the nation! There were other negative reviews of Sandfort’s work as well, all but dooming the boys and their partners to fire and brimstone, and Sandfort, the voyeuristic author, to a new persona as a pillar of salt. Obviously, even with an influx of porn, the relatively tolerant attitude toward sex that prevails in secular Holland has not corrupted our fair land. (A side thought: When it comes to fire and brimstone, wouldn't free-living San Francisco be Sodom, and turpitudinous New York Gomorrah? So maybe, by implication, this post does relate a bit to the Apple.)

And what of the 25 boys themselves, age 10 to 16, of whom 11 were clearly beyond puberty? When interviewed, they usually said that they met their older partner through family or friends; certainly they were not stalked. And after the first encounter, which rarely involved sex, it was the boys who sought to renew contact and develop a friendship. The ensuing friendship did involve pleasurable sex, but even more important were shared activities like swimming, movies, or visits to an amusement park. At their partner’s home the boys were more relaxed and enjoyed more freedom than at their own home, even when the boys had good relations with their parents. Trust and loyalty developed, and the ability to talk freely about anything: as an American teenager in a similar relationship once said to Oprah, "I can tell him anything and not feel judged!" While the parents usually knew about these friendships, they didn’t know about the sex, which they would think “really bad” or “not nice” or “dirty” – attitudes that the boys considered old-fashioned and stupid. A common thread in these stories was the boys’ determination to live their own lives, regardless of the opinions of others. The study concluded that, for boys in pedophile relationships, the present laws in Holland posed far more of a threat than a protection, and urged the passage of more enlightened legislation.

In the light of such studies, which reinforce the lessons of Joe’s story, I revised my attitude toward consensual man/boy relationships. Of course child molestation exists: three friends of mine were molested as children and bear the resulting emotional scars to this day, but these were nonconsensual encounters. I now view consensual man/boy relationships as legitimate and constructive, if the boy is past puberty and able to give knowing consent. This does not mean that I go along wholeheartedly with the arguments of the North American Man/Boy Love association (NAMBLA),

which beats the drums for complete tolerance of these friendships, regardless of the age of the boy. Certainly I agree with their plea for greater tolerance and understanding, and their wish to free all men imprisoned for having had consensual sexual relationships with minors. But they want no age of consent at all, which at this point I find questionable; arbitrary as it is, the age of consent -- 15 or 16 in most states, but 17 in New York -- should be lowered but not abolished. Yet even here I confess that NAMBLA's arguments against any age of consent at all are powerful, since such stipulations are not only arbitrary but subject to prosecutorial abuse. NAMBLA's is a lonely path, shunned and even condemned by mainstream gay organizations, who don’t want their campaign for gay rights to be contaminated with anything that might be construed as child molestation. Pedophiles are only a tiny minority of the gay population and suffer prejudice and misunderstanding accordingly. I am not of them, but I can sympathize. Which puts me in a strange middle place, tolerant, yet tolerant with a few reservations. But since when was life not complicated?

which beats the drums for complete tolerance of these friendships, regardless of the age of the boy. Certainly I agree with their plea for greater tolerance and understanding, and their wish to free all men imprisoned for having had consensual sexual relationships with minors. But they want no age of consent at all, which at this point I find questionable; arbitrary as it is, the age of consent -- 15 or 16 in most states, but 17 in New York -- should be lowered but not abolished. Yet even here I confess that NAMBLA's arguments against any age of consent at all are powerful, since such stipulations are not only arbitrary but subject to prosecutorial abuse. NAMBLA's is a lonely path, shunned and even condemned by mainstream gay organizations, who don’t want their campaign for gay rights to be contaminated with anything that might be construed as child molestation. Pedophiles are only a tiny minority of the gay population and suffer prejudice and misunderstanding accordingly. I am not of them, but I can sympathize. Which puts me in a strange middle place, tolerant, yet tolerant with a few reservations. But since when was life not complicated?Source note: The two books mentioned earlier are:

Crime Without Victims, ed. the "Trobriands" collective of authors, trans. E. Brongersma, Amsterdam: Global Academic Publishers, 1993.

Theo Sandfort, Boys on Their Contacts with Men, Elmhurst, NY: Global Academic Publishers, 1987.

I queried NAMBLA by e-mail, asking permission to use a photo from their home page, but got no response. So I've done without the photo and have included no link to their website. I would still welcome feedback from them on this issue.

Thought for the day #1: Desire is holy. (Yes, a repeat from earlier, but relevant. Please note: I didn't say "wise" or "prudent" or "legal," just "holy," which viewers will interpret as they wish.)

Thought for the day #2: Humankind cannot bear very much reality. -- T.S. Eliot. Indeed, we live immersed in illusions and surface only occasionally to glimpse what is really real.

P.S. I finally heard from NAMBLA; their e-mail follows. They also made an interesting comment: see Comments. I won't reproduce the photo of a painting, since by itself it could be misinterpreted.

Hello, Mr. Browder,

Thanks for your message, and for your interest in our organization. It has taken me too long to respond, and I must apologize.

The picture you asked about could be seen as too narrow a focus on younger boys, although it is a famous work by a first-rate American painter. And, while that simply wouldn't be an accurate portrait of NAMBLA, it was legally unobjectionable. I couldn't know the context, nor could I guess what use you might make of this image, so I asked for the opinions of our editorial crew. And, as usual, that is a slow process.