Clifford Browder's Blog, page 33

September 11, 2016

253. J.P. Morgan: Scheming Monopolist or Savior of the Nation?

When not rescuing corporations and governments or making the national character more Christlike (see the previous post), J.P. Morgan was traveling abroad and adding to his collections. Having little interest in art, his wife said he would buy anything from a pyramid to Mary Magdalene’s tooth. By now they had drifted apart, she preferring a quiet life and plain living, whereas he wanted an exciting life in the company of a host of friends. Nor did it help that both were subject to periodic depression. In his frequent travels he enjoyed the company of handsome, self-possessed younger women who shared his love of society and self-indulged pleasures – women, in other words, very unlike his wife, whom he usually lodged on the other side of the ocean, or in a spa in France while he hobnobbed with affluent friends on his yacht in the Mediterranean.

In another age divorce might have been an option, but not in this late Victorian era. There were those among the rich who did divorce, but disgrace and ostracism followed. For Morgan, a pillar of the Anglican Church and an esteemed member of countless boards and clubs, it was out of the question, but how far his friendships with other women went can be debated. Morgan’s attitude in such matters is well expressed by a story recounted by one of his biographers. A young partner of his having been caught in an adulterous affair, Morgan summoned him into his office and upbraided him. “But sir,” the young man protested, “you and the other partners do the same thing yourselves behind closed doors.” “Young man,” said Morgan, eyes ablaze, “that is what doors are for!” So Morgan endorsed the eleventh and supreme commandment: Thou shalt not be found out. But found out he may have been, for the gossip sheet Town Topics of July 1895 asked, “Why does the wife of a certain wealthy man always go to Europe about the same time he returns home, and vice versa?” Mentioned on the preceding page were Mr. and Mrs. Pierpont Morgan and, in a separate article, Edith Randolph, a widow whom Pierpont Morgan had been seeing a lot of at the time. The editor of Town Topics, Colonel William D’Alton Mann, was in the habit of reporting illicit behavior by an unnamed individual, while naming the transgressor in a paragraph nearby; alarmed, the offender was usually forthcoming with cash to buy Dalton’s silence. When Dalton was sued for libel in 1906, the names of his victims and the amounts they paid came out, including Pierpont Morgan, $2500. The defendant insisted that this and other such sums were simply unrepaid loans, but admitted approaching numerous men of wealth to ask them to “accommodate” him so as to avoid future criticism on his part. Still, $2500 was a modest bit of accommodation, compared to the $25,000 forked over by William K. Vanderbilt, a grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, for who knows what transgressions. As for the lady in question, Mrs. Randolph, in 1896 she remarried, thus removing herself from the purview of Pierpont Morgan, who found solace in the company of another younger woman encumbered with a husband and two children, but not with too strict a concept of propriety. As for Colonel Mann, he himself escaped prison, but his agent was convicted of extortion, and Dalton’s extortion business was thoroughly exposed.

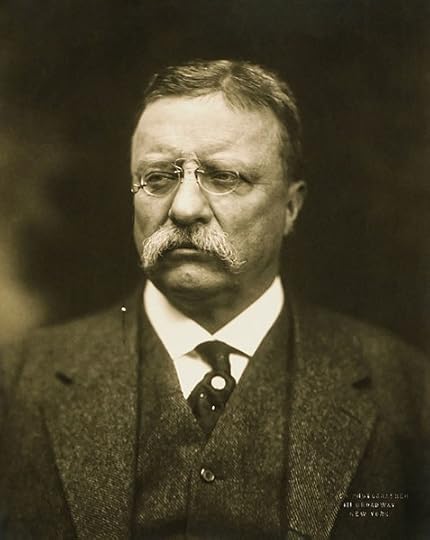

As long as business-friendly William McKinley was president, Morgan and the business community breathed easy, for they knew what to expect. But when McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist in 1901, he was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, a rough-riding cowboy with novel and alarmingly progressive ideas. Roosevelt had become a national hero by charging up San Juan Hill in the recent war with Spain, and now he had charged right into the White House, and for the business community this meant trouble.

Another moustached powerhouse, but this one was in the White House.

Another moustached powerhouse, but this one was in the White House.Sure enough, in 1902, making use of the rarely enforced Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the president filed suit against the Northern Securities Company, a railroad holding company organized a year earlier by Morgan and the presidents of three railroads so as to limit ruinous competition. The company was accused of illegal restraint of trade. Morgan was stunned. Why hadn’t the president consulted him? He hurried to Washington to have a talk with Roosevelt. “If we have done anything wrong,” he told the president, “send your man to my man and they can fix it up.” Replied Roosevelt, “That can’t be done.” Morgan was stunned again. This wasn’t how gentlemen did business. You didn’t make your differences public, you worked them out in private. But this Rough Rider in the White House, though from an old New York family, had different ideas on the matter – wild ideas, and dangerous. He wanted to subject businessmen – the very men who were making the country prosperous and a leader among nations – to the rule of government! The case against Northern Securities went all the way to the Supreme Court, which in 1904 ruled that the company was an illegal combination and would have to be dissolved, which it promptly was. Morgan had lost, Roosevelt had won. But this didn’t make them irreconcilable foes, for each found the other useful – yet another example of how power respects power. Roosevelt began distinguishing between “good” and “bad” trusts, put Morgan’s in the “good” category, and consulted the banker on matters of finance – the kind of behind-the-scenes conferring that old J.P. infinitely preferred.

But more trouble was coming. Seemingly out of nowhere, October 1907 brought a rude shock to Morgan and the nation, when a speculator’s misguided attempt to corner the stock of the United Copper Company failed, sending the company’s stock plunging. Then the speculator’s brokerage house failed, and runs began on banks associated with him and his confederates. Other banks tightened up on loans, interest rates on loans to brokers soared, stock prices plummeted, and more banks failed. Suddenly the whole financial system looked shaky, and the Panic of 1907 was well under way. All eyes turned to J.P. Morgan, the city’s most prestigious and most well-connected financier, who had squelched financial crises before. Out of the city attending an Episcopal convention in Richmond, Virginia, he received wires and messengers from his partners, who warned him not to rush back immediately, since that would only heighten the sense of panic. As soon as the convention ended, Morgan hurried back to the city and summoned a host of bank and trust company presidents to his library on 36th Street, where he and his associates scanned the books of endangered corporations and decided which ones could be saved. Secretary of the Treasury Cortelyou came from Washington to help, and John D. Rockefeller put up $10 million. From then on the Morgan Library, a high-ceilinged treasure house of Gutenberg Bibles and Renaissance bronzes, would be the scene of one emergency meeting after another. On October 24, when stock prices continued to plunge, and the Stock Exchange threatened to close early, Morgan, puffing on a cigar, sleep-deprived and fighting off a cold, summoned the presidents of the city’s banks to his office, and told them that as many as 50 brokerage houses would fail unless they raised $25 million in ten minutes. The money was raised, disaster was averted. When the panic resumed on the following day, Morgan got the banks to pledge more money to keep the exchange open, and brokers on the exchange floor cheered. This calmed the panic on Wall Street, but on October 28 the mayor of New York came to Morgan and informed him in confidence that the city was verging on bankruptcy, whereupon Morgan and two allies quietly agreed to buy $30 million of city bonds. And when yet another major brokerage house verged on failure, Morgan summoned a group of executives to yet another emergency meeting at his library and averted yet another collapse. But the crisis was far from over, for the financial system still looked shaky. When runs threatened two more trust companies whose failure could not be risked, Morgan summoned some 50 bank and trust company presidents to his library on Friday, November 2, locked them in his sumptuous study, pocketed the key, and in what turned out to be an all-night session, demanded that they pool their resources to make a loan of $25 million to save the companies. The financiers at first held back, but who could withstand Morgan’s imperious will and his piercing eyes, meeting whose gaze was said to be like looking into the lights of an oncoming express train? Glaring fiercely, he held out a pen, gestured toward the relevant document, and said to one of them, “There’s the place, and here’s a pen. Sign!” The banker did, and so did all the others, one by one. Only when he had obtained the last signature, did Morgan unlock the door at 4:45 a.m. on Sunday and let them wearily depart. But that was not the end of it. The approval of President Roosevelt was necessary, since part of the proposed solution involved U.S. Steel’s acquiring a troubled steel producer, so two bankers had rushed to Washington to see him. But would the trust-busting president approve a deal allowing the biggest corporation in the world to get even bigger – a transaction that would arouse public criticism and invite antitrust proceedings? Roosevelt heard them out, grasped the situation, and gave his assent. Minutes before the Stock Exchange opened on Monday morning, November 4, a phone call from Washington reported the president’s decision -- news that, when relayed to the exchange, immediately restored confidence. After two weeks of panic the crisis was finally resolved, and for the first time in days the exhausted old man got a good night’s sleep.

The panic had affected the whole nation. Throughout the country bankruptcies multiplied, production fell, unemployment rose, and immigration plunged. When my maternal grandfather, a respected judge in Indianapolis, Indiana, suffered financial reverses, he had his eldest child, my mother, become a schoolteacher so as to bring in more money. Barely eighteen, she taught in a little one-room rural schoolhouse for two years, a maturing experience made necessary by mysterious happenings on Wall Street in distant New York. But not all families coped as well; many were ruined.

In the wake of the panic J.P. Morgan was seen as a hero by many, but not by all, and suspicions arose at once. Had the panic been engineered by the banks so they could profit from it? Had Morgan (who in fact had lost $21 million in the panic) taken advantage of it? And should the safety of the entire financial system depend on one man, however well-intentioned, and what would happen when this aging benefactor – if benefactor he was – departed this earth for celestial climes? Debate raged. Finally, in 1912, a special House of Representatives subcommittee, chaired by Representative Pujo of Louisiana, set out to investigate the “money trust,” the alleged monopoly whereby Morgan and other city bankers controlled major corporations, railroads, insurance companies, securities markets, and banks. Morgan of course was subpoenaed, and his testimony would be the climax of the investigation. Politicians, lawyers, clerks, journalists, and visitors awaited his arrival with the keenest interest. It would be the kind of public event that the Napoleon of Wall Street loathed, and an abrupt change from quietly professing his love at age 75 to Lady Victoria Sackville earlier that year in England, and sailing with Kaiser Wilhelm in a five-hour race at the Kiel regatta – a race that they won by twenty seconds, filling the emperor with joy. Back home from these diversions, Morgan went to Washington with misgivings. On December 18, 1912, he showed up at the hearing in a dark velvet-collared topcoat and the inevitable silk hat, accompanied by his daughter Louisa and his son Jack, plus partners and lawyers. On that day and the next, in a room crammed with journalists, photographers, and spectators, the committee’s counsel, Samuel Untermyer, questioned him at length, establishing that officers of Morgan’s and four other banks held 341 directorships in 112 U.S. corporations, with the Morgan partners alone sitting on 72 boards. Some questions Morgan said he couldn’t answer, and some of his answers seemed enigmatic, for he and Untermyer were in different worlds, operating under different assumptions. Asked if he wanted to control everything, Morgan said clearly enough that he wanted to control nothing. And when asked if he was not a large shareholder in another major bank, he replied, “Oh no, only about a million dollars’ worth,” and was surprised when the spectators laughed. Finally, in an exchange that would become famous, Untermyer asked, “Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?” “No sir,” said Morgan. “The first thing is character.” “Before money or property?” “Before money or property or anything else. Money cannot buy it.” Saying this, Morgan was quite sincere. In the world of gentlemen bankers, one did business with people one knew and trusted; character – perceived character – did indeed count.

Morgan, his family, and friends all thought that he done quite well before the committee, and much of the press agreed. Two weeks later he left for Egypt with his daughter Louisa and several friends. He seemed fine while crossing the Atlantic, but then became agitated and depressed. On the Nile he fell into a delusional depression, had bad dreams, spoke of conspiracies and subpoenas and contempt of court, and told Louisa that the country was going to ruin, that his whole life work was going for naught. As the party retreated to Cairo and then to the Grand Hotel in Rome, word of his condition got out, and messages of concern came from the pope, the king of Italy, and the Kaiser. Flocking also to the hotel were art dealers and amateurs with bundles of items to sell to the great collector. Morgan rallied, made some jaunts into the city, but then declined, became delirious, and died in his sleep on March 31, 1913, just shy of his 76th birthday, the cause of death never ascertained. Flags on Wall Street immediately flew at half mast, and on April 14 the Stock Exchange closed for two hours while his body passed through New York City on its way to burial in Hartford. The funeral at St. George’s Church in Manhattan displayed flowers from the Kaiser, the government of France, and the king of Italy; 1500 attended, with thousands more outside. There were memorial services in London and Paris as well. The total value of his estate was about $80 million (well over $230 million in 2016 dollars); most of it went to his son, with generous bequests to family and friends. His son put most of his art collection on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and subsequently sold some of it to various collectors, but donated many works to the Met.

Was John Pierpont Morgan’s death hastened by the Pujo committee’s treatment of him, and public skepticism about the values he held dear? Probably. The world was changing, and Morgan was too old and too fixed in his ways to change. The era of the gentleman banker had passed. In 2013 Congress created the Federal Reserve System to provide central control of the monetary system, issue currency, and create a stable financial system, which, with its powers expanded, it does to this day. It took a complex system of twelve regional banks, each with branches and a board of directors, and a seven-member governing board appointed by the president, to fill the void left by the death of J.P. Morgan.

I confess I'm rather taken with old J.P. and his naiveté -- yes, naiveté! -- in thinking that gentlemen bankers of good character could still handle the affairs of the nation, and that in creating monopolies he had America's best interests at heart. Both eulogists and critics of the man were correct. John Pierpont Morgan was both a monopolist and a savior of the nation, an autocrat and a benefactor. He truly believed that the wealth he had accumulated should be used for the good of the nation

-- richesse oblige -- and acted accordingly. Luckily, he died before the outbreak of World War I. Having been a friend of both the king of England and the emperor of Germany, he could never have adjusted to a war-ravaged Europe and the catastrophic end of the world he had known. He believed in order; war brought chaos.

Source note: For information in this post, as in the preceding one, I am indebted to Jean Strouse’s magisterial biography, Morgan: American Financier (Random House, 1999).

* * * * * *

My poems: For five acceptable poems, click here and scroll down. To avoid five terrible poems, don't click here. For my poem "The Other," inspired by the Orlando massacre, click here.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: Katahdin: How, even with a governor against it, a nonprofit gets things done.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on September 11, 2016 04:53

September 4, 2016

252. J.P. Morgan: The Man and His Nose

For some, he was “the financial Moses of the New World” or “the Napoleon of Wall Street”; in conferring an honorary degree on him, a Yale professor had likened him to Alexander the Great, though one might just as well throw in Julius Caesar and Louis XIV. But for others he was “a beefy, red-faced, thick-necked financial bully, drunk with wealth and power,” or “the boss croupier of Wall Street … a bullnecked irascible man with small black magpie eyes,” or an “imperiously proud, rude and lonely, intensely undemocratic” robber baron. Obviously, in his own lifetime and since, a divisive figure, inspiring diametrically opposite reactions. His name comes to my mind daily, since my bank is J.P. Morgan Chase, the modern descendant of the J.P. Morgan & Company of his own time. As I grew up, I was only vaguely aware of him as a historical figure, until I saw a performance of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness, whose idealistic young protagonist, Richard Miller, wants to see old J.P. carted off to the guillotine for his crimes. A somewhat biased introduction to the nation’s greatest banker of the early 1900s, and an impression somewhat modified when, years later, I read about how, singlehanded, he stopped the Panic of 1907. No one would deny that, back in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, John Pierpont Morgan was a power to reckon with. A heavyset man dressed in a black silk topper and dark coat, well mustached, and carrying a silver-topped mahogany walking stick, he looked the very image of the plutocrat. But there was more to him than that. A woman who knew him said that, when he entered a room, you felt “something electric,” and a woman employee who greatly respected him called him the most exhausting person she had ever known. Similarly, his friend William Lawrence, the Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts, said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling as if a gale had blown through the house. And his accomplishments matched his image. He had “Morganized” (reorganized) the nation’s railroads, put together the world’s first billion-dollar corporation, U.S. Steel, and helped create such industrial behemoths as International Harvester and General Electric. He sat on the boards of the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art; gave substantial gifts to schools, hospitals, museums, and the Episcopal Church; and loved yachting, built a series of luxurious custom-made yachts, and was elected commodore of the New York Yacht Club. Yet in spite of all these activities, he found time – lots of it – for collecting rare books and illuminated manuscripts, paintings, sculpture, jewelry, portrait miniatures, tapestries, ivories, coins, armor, medieval reliquaries, Chinese porcelains, and Roman frescoes. Indeed, what didn’t he collect?

How does one become a financial Alexander the Great? It helps to have a moneyed father already well established in business. One thinks of John Pierpont Morgan as the financial Titan of later years, a man who could never have been young, but of course he had a youth, an apprenticeship to what he became. Born in 1837 in Hartford, Connecticut, he was the son of Junius Spencer Morgan, a successful American dry goods merchant who later became a banker based in London. Since his mother, Juliet Pierpont, of an old New England family, was self-absorbed, demanding, and often depressed, it was his father who monitored his childhood. From an early age Junius Morgan supervised his son’s every activity and groomed him for a career in international banking. He helped the boy with his homework, supervised his reading, and sent him to a boarding school in Switzerland so he could learn French, and then to a university in Germany to learn German. Returning to this country, young Pierpont did a two-year apprenticeship arranged by his father with a Wall Street firm, and then became the New York agent for his father’s London-based bank. In this capacity he made a trip to the South in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, to give his father a report on the railroads, banks, and cotton merchants with whom Junius Morgan was doing business. He talked with his father’s business connections in various cities and sent back the desired reports; surprisingly, he seems not to have said much about the looming threat of secession, and how Southerners viewed this young interloper from the North. War soon came, but young Pierpont didn’t rush to enlist; instead, he exercised his patriotism by buying substandard carbines from the Army in the East for $3.50 each, and then selling them to the Army in the West for $22.00, thus realizing a tidy profit at the cost of involvement in a deal that, when later investigated, became highly controversial. Right from the start he had a keen nose for moneymaking opportunities, and if the affair did him little credit, it was no worse than what many canny merchants in the North were doing to satisfy the nation’s sudden need for arms and supplies. At the same time young Morgan was seeing to his father’s affairs in this country, but also courting the delicate young woman who in October 1861 became his wife. The newlyweds honeymooned in Europe, but the trip was anything but idyllic, since the bride was diagnosed with tuberculosis and died in France in 1862, leaving Morgan stricken with grief. Returning to this country, he paid $300 to a substitute to avoid the draft, and succumbed to the fever of the time by speculating in gold, the price of which was fluctuating wildly, reaping censure from his conservative father while netting $66,000 in profits. Soon after the war ended, in May 1865 he married his second wife, Frances Louisa Tracy, by whom he would have a son and three daughters. Well schooled and well traveled, with smooth manners, European clothes, and a command of two foreign languages, Pierpont Morgan showed no trace of Commodore Vanderbilt’s unlettered roughness or the flamboyance of Jim Fisk, and was accepted at once by New York society. They knew a gentleman when they saw one, and young Morgan was fast becoming a gentleman banker, a species that he believed should rule the world of finance. Over the next two decades he and his firm, Drexel, Morgan & Company at 23 Wall Street, loomed ever larger in that world, as he and his junior partner Anthony Drexel, a Philadelphia banker, sold bonds, negotiated deals, and raked in a fortune. Working at the same time with his London-based father, Pierpont Morgan channeled British money into American enterprises, and by the 1890s had helped transform his nation and its agricultural economy into the greatest industrial power in the world. The twentieth century, he was sure, would be an American century, and he was doing all he could to bring it about. The Atlantic cable made communications between New York and London much easier, but the Morgans sent their messages in code, Pierpont being variously designated “Vienna,” “Charcoal,” “Flintlock,” or “Flitch.” One of his messages to his father read in part, “amber despise maliciously fawn whisper shank plainness,” which meant that he hoped to open negotiations with the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company. In his public as in his private life, he practiced discretion to the point of secrecy. This was the Gilded Age, and the wealthy dressed it and lived it. In 1872 Morgan bought Cragston, a 386-acre farm in Highlands Fall, New York, overlooking the Hudson, and turned it into an English country estate, filling the house with paintings, Chippendale furniture, potted palms, and Persian rugs, and creating tennis courts, stables, gardens, greenhouses, and a carriage house. And in 1880 he bought a brownstone at 219 Madison Avenue on the northeast corner of 36th Street and renovated the interior, installing Oriental rugs, ceramics, paintings, stained glass, and bric-a-brac. His library had wainscoting of Santo Domingo mahogany, and featured allegorical figures representing History and Poetry in octagonal panels on the ceiling, though his interest in those subjects was slight. In those days ornamental clutter prevailed, yet both house and country estate were modest by comparison with the grandiose residences of many of Morgan’s contemporaries, since he opted for patrician restraint. But restraint was not his way when it came to the latest in technology. His Manhattan home had an elevator, a two-story burglar-proof safe, and a private telegraph connecting it to his office at 23 Wall Street. And it became the first private residence in the city entirely illuminated by Thomas Edison’s newfangled invention, the light bulb, whose development Morgan encouraged, making his firm the young inventor’s banker on both sides of the Atlantic.

It was in the 1890s that Pierpont Morgan became, completely and definitively, the J.P. Morgan of legend. When his father died of a carriage accident in 1890, he mourned the man who had dominated his life for decades, an exacting monitor who had viewed his son at first with reproach and finally with pride. His estate was worth $23 million, and most of it went to Pierpont. The son now took his father’s place as head of J.S. Morgan & Company in London. And following the death of his longtime partner Anthony Drexel, in 1895 he renamed his Wall Street firm J.P. Morgan & Company, and became the head of a Drexel bank in Philadelphia as well, and another bank in Paris. He would soon be rivaling the Rothschilds in financial eminence. His subsequent accomplishments were impressive: he headed the corporation that would build the vast new Madison Square Garden in 1890; saved the Union Pacific Railroad from bankruptcy in 1891; in 1895 sold gold to the U.S. Treasury, which was almost out of it, thus preventing a government default; and in 1901 astonished Wall Street by organizing U.S. Steel, the biggest corporation in the world. U.S. presidents routinely consulted him, and when his friend the Prince of Wales became Edward VII of Great Britain, Morgan was an invited guest at the coronation. He also dined with King Leopold of Belgium and, to the dismay of his English friends, hobnobbed cordially with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany. John Pierpont Morgan had more royal connections than the president of the United States. Another accomplishment was the building of the Morgan Library on East 36th Street to house his growing collections and a study where he could meet with business colleagues, art dealers, and friends. For an architect he chose Charles Follen McKim, an eminent partner of Stanford White who today is less remembered than White because, unlike White, he was not so lucky as to be murdered in fashionable Madison Square Garden in front of hundreds of witnesses. Closely supervised by Morgan, whom the architect referred to as Lorenzo the Magnificent, McKim created a sober classical structure in Italian Renaissance style that expressed its owner’s sense of grandeur and patrician taste. Completed in 1906 with a private tunnel connecting it to Morgan’s nearby residence, the library’s vaulted rotunda, marble floors, and frescoed ceilings soon housed his vast collection of rare books and manuscripts, not to mention a sixteenth-century Brussels tapestry, The Triumph of Avarice, whose inclusion might imply a touch of irony, since its owner viewed himself as generous, not greedy. Morgan’s favorite spot in the library was his private study, where he spent part of each day at his custom-made desk, surrounded by stained-glass windows and, flanking the desk on either side on the red damask walls, two panels of a Hans Memling altarpiece of the fifteenth century. In such a setting he might well have thought himself, not a twentieth-century American banker, but a prince of the Renaissance.

Pierpont the Magnificent had clerical connections as well. He was active in the affairs of the Episcopal Church, even attending church conventions that most laymen would have found excruciatingly boring. He was generous with funds as well, donating hundreds of thousands of dollars for a new Episcopal cathedral to be located far north of the settled sections of the city in Morningside Heights, a cathedral to be named St. John the Divine. Just how cozy Morgan and the Church could be is evidenced by his friend William Lawrence, Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts, whose 1901 article “The Relation of Wealth to Morals” made these interesting observations:

· In the long run, it is only to the man of morality that wealth comes.· Godliness is in league with riches.· The search for material wealth is as natural and necessary to man as is the pushing out of its roots for more moisture and food to the oak.· Material prosperity is helping to make the national character sweeter, more joyous, more unselfish, more Christlike.

Having been Morgan’s guest in his palatial residence and on his yacht, and having sailed with him up the Nile, the good bishop surely knew whereof he spoke, and with all these statements his host would have heartily agreed.

Who exactly was this Titan of finance who advised presidents, socialized with monarchs, traveled widely, collected ravenously, and gave an abundance of time and money to his church? Photographs show a burly gentleman of many years (he weighed 200 pounds by age 30), inevitably topped by a black silk hat and walking with a tapered walking stick, white-haired, with a prominent nose over a drooping, grayish mustache, and dark eyebrows over eyes whose piercing gaze is rendered well in portraits – a gaze that, if angry, could cut you to the quick. No question, this man had the appearance not just of wealth and prosperity, but of willfulness and domination. And behind all that? A man of great reserve, opinionated, often intemperate, but capable of charm. A victim of periodic bouts of depression that he fought off with hard work, ocean voyages, spa cures, and frenzied socializing. No scholar and, in spite of his vast collection of rare books and manuscripts, no reader; a doer who had little time for reflection or contemplation. A man who never doubted his own convictions, who was sure that what benefited him would benefit the nation as well. A man who, surrounded on all sides by flattery and adulation, was not used to being challenged or contradicted. Seated in his glass-walled office with an open door at 23 Wall Street, he was quite capable of letting someone who wished to speak with him stand there quietly, unnoticed, for ten minutes or more, while he studied a sheet with a list of figures; should the intruder address him and jolt him out of his trance, a verbal explosion would follow. Decidedly, a man used to having things on his own terms, on routinely getting his way.

And a man with a nose. In his later years a nose that was bulbous and flagrantly purple, because of a skin condition called rhinophyma. Self-conscious about it, he hated being photographed, was known to lunge in fury, walking stick upraised, at any photographer who dared to point a camera at him in public. The story is told how the wife of a partner of his, wanting her daughter to meet the great man, invited Morgan for tea. For weeks she coached the daughter how to behave on the occasion: the daughter would enter the room, greet him courteously, not look at his nose or mention it, then tactfully depart. When the day came, the hostess and her guest were sitting on a sofa by the tea tray, when the daughter entered, greeted Mr. Morgan respectfully, did not look at or mention his nose, and after a few minutes left. The mother was vastly relieved: it had all gone so well. Turning to her guest, she asked, “Mr. Morgan, do you take one lump or two in your nose?” Yet women found him attractive, nose and all. The force of his personality overwhelmed them, and overwhelmed his male friends and colleagues as well, rendering his unsightly nose all but irrelevant. He may even have gloried in its grotesqueness, being delighted to impose it on others and get them to accept him regardless. His millions helped, but it was the force of character behind those savage eyes that overpowered others, subjecting them to his will.

How this man with an imperious will and a purple nose stopped a panic singlehanded and was hailed as either a savior of the nation or a villainous plutocrat will be told in the next post.

Source note: For information in this post I am indebted to Jean Strouse’s exhaustive and exhausting biography, Morgan: American Financier (Random House, 1999), a book that for most readers is too long by half, but that is based on thorough research, leaves very little out, and richly conveys the man and his times.

My poems: For five acceptable poems, click here and scroll down. To avoid five terrible poems, don't click here. For my poem "The Other," inspired by the Orlando massacre, click here.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: J.P. Morgan: Villainous Plutocrat or Savior of the Nation?

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on September 04, 2016 04:52

August 28, 2016

251. Sailors' Snug Harbor, Staten Island

Imagine five temple-like Greek Revival buildings set side by side, their façades perfectly aligned, with an eight-columned portico in the center, flanked on either side by another impressive classical façade and, at either end, a six-columned portico. Is this a college campus? A small-town square? Certainly the façades suggest college buildings or government administrative centers, or maybe Carnegie libraries of another era, or churches, but five of them in a row is impressive … and surprising. And these structures aren’t in an urban setting, having spacious grounds around them. When I first saw them it was a mild autumn day, and from where I stood, contemplating them, I could also see the broad lawn in front with a stand of oak trees that were gently shedding their leaves, and a view down the sloping grounds past a shoreline boulevard to the wide expanse of New York harbor and, somewhere off in the distance, the faint silhouette of the skyline of Manhattan. I was charmed and impressed, for never before had I seen such an alignment of handsome Greek Revival buildings – not row houses like you see in Greenwich Village and other older parts of Manhattan, but free-standing structures of magnitude.

So welcome to Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden, located on the north shore of Staten Island, which I was visiting with a friend who had piqued my interest by saying, “If you don’t know Snug Harbor, you don’t know Staten Island.” I had hiked for years in the Greenbelt, the chain of parks running through the center of Staten Island, but I had never seen anything like this. The two structures on the right constitute the Staten Island Museum; the magnificent central building with the eight-columned portico is the Visitor Center and Galleries; the building immediately to the left of the central building is the Noble Maritime Collection; and the last building on the left is at present not in use. Except for the latter, on that idyllic autumn day I and my friend visited all these buildings.

The central building has an impressive two-story main hall that serves as the Visitor Center, with stained-glass transoms by Tiffany and, topping the ceiling’s murals, a towering sky-lit dome. The Staten Island Museum offers art work from the past and present, and natural history collections that include fossils of prehistoric creatures -- the kind of thing that bores some people but fired up my imagination as a kid, letting me dream of raging Tyrannosaurs and spike-backed Stegosaurs, and lumbering Mastodons and lowly Trilobites, images that haunt me to this day. Also in the museum is a series of panoramic paintings showing the successive stages of Staten Island’s history, ranging from idyllic rural through industrialization (yes, once there was heavy industry on Staten Island), to the modern landscape with clusters of suburban homes that shelter good Republicans (this is the one Republican borough in the city), plus commuter bridges, high-rises, and shopping malls – an exhibit that instilled in me a deep yearning for the rural setting that once was, and never will be again. The Noble Maritime Collection focuses on the work of artist John A. Noble (1913-1983), who often sketched derelict ships in the harbor. Especially featured is his houseboat studio, originally the teak saloon of an abandoned yacht where he created his lithographs, paintings, and photographs: a unique exhibit that lets you play voyeur by peeking into the studio and its contents, which include an easel, a drawing table, a ship’s bed, and several jars crammed with paintbrushes.

So much for what’s inside these handsome Greek Revival buildings, and I haven’t covered it all by a long shot. But why is the whole shebang called “Snug Harbor”? Because it was originally founded through a bequest by merchant and ship master Robert Richard Randall, who when he died in 1801 left his 21-acre Manhattan farm, located in what is now Greenwich Village, to be the site of an institution, governed by eight trustees, to care for “aged, decrepit, and worn-out seamen.” His heirs contested the will, delaying the opening of the home for decades. By the time the matter was settled, his once rural Manhattan estate had been overtaken by development and acquired great value. So the trustees appointed by Randall’s will, wishing to maximize profits on the Manhattan estate, changed the site of the proposed institution to a 130-acre farm that they purchased on the north shore of Staten Island. The first U.S. home for retired merchant seamen, Sailors’ Snug Harbor opened at last in 1833, when Greek Revival architecture was all the rage, with the cost of its operation amply covered by revenue from the property in Manhattan.

At first the home consisted of a single building, the central building with the eight-columned portico, but in time other buildings were added. The five adjacent temple-like structures housed dormitories, the kitchen, the dining hall, a reading room, and other facilities; other buildings in Greek Revival, Beaux Arts, Italianate, and Victorian style were added elsewhere on the property, which became a completely self-sustaining operation, including a farm that let the residents provide their own food, and a cemetery. All were welcome there, except for alcoholics and those with a contagious disease or immoral character. The home began with 37 retired seamen, but over time it grew to house a thousand, including American, English, Irish, Scotch, Dutch, Prussian, and French residents, each of whom got a two suits a year from Brooks Brothers. And if a resident was too feeble to walk to a nearby brewery, he could have his grog delivered to the home. But neatness was the rule: each dormitory had a “captain” who kept things orderly.

All was well until the mid-twentieth century, when Social Security and Medicare diminished the need for accommodations for aging seamen, and declining revenues led to the structures’ falling into disrepair and even to the demolition of some of them. In the 1960s the trustees proposed to redevelop the site with high-rise buildings, but the city’s Landmarks Commission intervened to save the five Greek Revival buildings by declaring them landmarks. In 1976 the trustees moved the institution to North Carolina and sold the site to the city. In June of that year 30 seamen, a physician, a nurse, and three aides took a 14-hour bus ride to their new 8,000-acre home in North Carolina, joined later by 75 more seamen who got there by plane. The Snug Harbor Cultural Center opened that same year, and in 2008 it merged with the Staten Island Botanical Garden to become the nonprofit Snug Harbor Cultural Center and Botanical Garden. Meanwhile the Snug Harbor trustees, headquartered in Manhattan, continue to give financial aid to seamen throughout the country.

Since on my first visit my friend and I explored only the Greek Revival buildings and a bit of the nearby grounds, we vowed to return in another season and explore the outlying grounds, some of whose features were installed after Snug Harbor ceased being a home for seamen. Among them is the Connie Gretz Secret Garden with a labyrinth that she had never visited, which was financed by a stockbroker in memory of his deceased wife, and inspired by the garden in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s children’s book, The Secret Garden. Given my lifelong fascination with gardens, especially secret or forbidden ones (see chapter 42 in my book), at the mere mention of this one I was hooked at once.

But what enticed us even more was the one-acre Chinese Scholar’s Garden. Described as the only authentic classical Chinese garden in the U.S., it was built, without nails, by a team of forty Chinese craftsmen who spent a year in China assembling the components, and six months here installing them. It is said to include magnificent rockery suggesting the mountains that inspired ancient poetry and paintings; a bamboo forest path; Chinese calligraphy; and a waterfall and pond. Snug Harbor partnered with the city of New York, the Landscape Architecture Company of China, the local Chinese community, and volunteers to build the garden, which opened in 1999.

The thought of this attraction reminded me of a smaller Chinese scholar’s garden at the Metropolitan Museum that I love, and conjured up fantasies of poet scholars communing in a most civilized manner in a place of solitude and calm. My guide and I had hoped to visit this and other marvels in the spring, but schedule problems made us postpone our second trip until July, when we went on a fine, mild day, prepared to trek a bit and be enchanted by the secret garden as a prelude to the Chinese garden’s magic.

So what did we then see and do? A host of things:

· An herb garden where I saw lovage and other herbs· A picturesque gazebo that we couldn’t enter but could view from the outside· An esplanade that we walked the length of, enclosed by vegetation arching overhead· A rose garden, though it was past the time to see roses at their peak· A big lawn that we crossed as a shortcut, giving me the delicious experience of walking over an uneven grassy surface, which I hadn’t done in years· A plant called acanthus with a long name I couldn’t pronounce, but that my companion, a gardener, recognized· A plant called elephant ear, whose leaves, when fully grown, are the size and shape of an elephant’s ear· The Connie Gretz Secret Garden, which loomed in the distance like a castle.

The Secret Garden was meant above all as an attraction for children, but the inner child in both of us responded. We entered through a monumental entrance resembling the tower of a castle, and then made our way through a labyrinth formed by hedges that was designed to teach children patience and perseverance in pursuit of a goal. Patience and perseverance we showed plenty of, as we negotiated the maze, finally arriving at the center, where we sat for a few minutes on benches in a spot enclosed by boxwood, before making our way out. Some parts of the park were nicely kept up by gardeners whom we saw busily (and sometimes noisily) at work, but other parts looked uncared-for and weedy – the result of a shortage of funds, my companion explained, and the lack of a central authority, different features being managed by different organizations. And the supreme goal of our visit, the Chinese Scholar’s Garden, with a promise of “soothing waterfalls and quiet walkways”? After a long trek we got there keen with anticipation and found it … shut. Locked up, keep out, closed, and no date for reopening posted, probably because of a lack of funds. This might have spoiled the visit, but there was too much else to see, for us to be downcast. Maybe another time, if weather and funding permit, meaning the garden’s funding, not ours. Even so, this trip was an idyllic excursion into a vast parkland full of attractions, some of which even on this second visit we never got to, on a perfect summer day. And even if the Chinese Garden proved to be indeed forbidden, we did walk the esplanade, see elephant ear, and visit the Secret Garden and its labyrinth. I recommend Snug Harbor to anyone interested in New York City history, Greek Revival architecture, or a quiet stroll through a vast parkland full of unusual attractions. I got there by car, but it is readily accessible by a short bus ride from the ferry terminal at St. George.

My poems: For five acceptable poems, click here and scroll down. To avoid five terrible poems, don't click here. For my poem "The Other," inspired by the Orlando massacre, click here.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: Who knows?

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on August 28, 2016 04:43

August 21, 2016

250. Forbidden Zones: The Old Brewery, Trump Tower, and the Weeds

There have always been forbidden zones in New York City – places of danger or places where you aren’t supposed to go. Today they are ribboned off with yellow tape marked “caution … cuidado … caution …cuidado,” usually to keep us out of construction zones. Or they are blocked off by wooden barricades to protect the path of a parade, or by signs saying HARD HAT AREA, DANGER, NO TRESPASSING, or by orange cones in front of sidewalk stairs leading down into the dark confines of a basement. But these are a part of our daily existence as New Yorkers, and therefore not remarkable. There have been other forbidden zones, more mysterious, more dangerous.

In the mid-nineteenth century, when the gentile middle class lived in brownstones and Greek Revival homes not far removed from the slums where the “dangerous classes” wallowed in poverty and degradation, the Five Points district, named for the convergence of five streets in Lower Manhattan just a short walk east of Broadway, was considered the worst slum in the city, and in it, the Old Brewery was deemed the worst tenement. The neighborhood had a grog shop on every corner, while from the upstairs windows whores with painted faces called down to drunken sailors in the street. Pigs ranged, dogs snarled, gangs lurked, children screamed. Certainly it was no place for respectable citizens.

The chipped walls of the Old Brewery loomed up like a huge toad splotched with warts across from Paradise Square, a triangle with six stunted trees, bricks and rubble, corncobs and manure, broken glass. Running beside the building was a dark lane three feet wide known as Murderers’ Alley; another lane led to a large room known as the Den of Thieves, where some 75 men and women lived, crammed in together. The Brewery was thought to harbor drunks and harlots, real and fake crippled beggars, and thugs for hire. Into its maze of dark passageways burglars and their loot vanished, while the police feared to follow. Rumors abounded of nightly killings there, of tunnels and hidden rooms, buried treasures, buried bodies. If ever, for honest citizens, there was a forbidden zone, it was the Old Brewery.

Which was why, in the early 1850s, the Ladies Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church decided not just to visit this district, but to establish a sabbath school for its ragged and unruly children, and to hold weekly temperance meetings in a mission room. But this was not enough; a committee of visitation, composed of two respectable and very determined Methodist ladies, began visiting every house and family in the area, and even penetrated the Old Brewery, negotiating its creaky stairs to explore its dark cellars and passageways and attics, where they found prostitutes and drunks aplenty, and families living in squalor, but no nests of thieves, no murderers, no hints of buried bodies. This was a gutsy undertaking for respectable ladies of that time, for whom good works through a church were the one adventure allowed, and the Methodist ladies were heeding the Biblical command to "go out into the highways and hedges" (Luke14:23), which for them meant the Old Brewery.

And this was but a prelude to the ladies' real undertaking. In 1852 they managed to buy the building and demolish it, so they could replace it with the Five Points Mission, a five-story brick building with a chapel, a schoolroom, and low-rent rooms for deserving families -- an enterprise that would be expanded in time and continue until the 1890s. The Methodists had come to stay, and the forbidden zone was forbidden no more.

Or was it? When the demolition of the Old Brewery was under way in 1852, human bones were found in the cellars and within the walls, and some intruders managed to gain entrance into one cellar and dig up something buried there and make off with it. So maybe the rumors of dark doings in the Old Brewery were not without foundation.

And what forbidden zones are there today? What if one looks upward? That’s exactly what hundreds of passersby were doing on Wednesday afternoon, August 10, on Fifth Avenue in front of the 68-story Trump Tower at 56th Street, which contains luxury shops and apartments, including the Donald’s very own residence. And what were they straining their necks to see? The same thing that millions were watching on TV and in videos posted on Facebook and elsewhere: a young man in shorts and a T-shirt climbing up the façade of the towering edifice, evidently using suction cups and a harness to accomplish this amazing feat in broad daylight. Which is, of course, a no-no; one isn’t supposed to go climbing up towers in mid-Manhattan. But the climber was already up five stories before the police got a 911 call alerting them, and only when he had climbed 21 stories in all were two of New York’s Finest able to remove a glass panel and reach out, grab him, and pull him into the building, ending what had become a three-hour social media sensation.

And who was this intrepid climber? Stephen Rogata, age 19, of Great Falls, Virginia, who had driven all the way from Virginia, checked into a cheap hotel on the Bowery the night before, then walked into the tower’s atrium, sneaked into a fenced-off area, and began his climb. And why had he undertaken this stunt? To get a personal meeting with Mr. Trump. On Tuesday, August 9, he had explained his motives in a YouTube video in which he said he was an “independent researcher” willing to risk his life for a significant purpose; later he told police he wanted to give the Donald “secret information” relating to how he will govern, if elected. Once secured, he was charged with felony reckless endangerment and misdemeanor trespassing, and taken to Bellevue Hospital Center for psychological evaluation. He endangered not only himself but others, an assistant D.A. insisted at the time of his arraignment on August 17, since during his climb several items fell out of his backpack, including a laptop computer, which might have injured bystanders on the sidewalk below and emergency responders. At the arraignment Mr. Rogata appeared through a video link to Bellevue, where he is still under psychiatric care, and where his parents have visited him. The judge set his bail at $10,000 cash or $5,000 bond.

This stunt recalls the 25-year-old Frenchman Philippe Petit’s amazing high-wire walk with a balancing pole between the Twin Towers in 1974, when he did eight passes on the wire to the astonishment of the onlookers on the street a quarter of a mile below. This feat led to his immediate arrest and then his release in exchange for doing a free performance for children in Central Park, where he did a high-wire walk over the Turtle Pond. An overnight celebrity, M. Petit stuck around over the years to do other less astonishing performances; I saw him several times performing as a mime at Sheridan Square, where he competed for attention with a mixed-race tap-dancing couple, and a woman who sang opera to recorded music. Whether Mr. Rogata will likewise become a celebrity remains to be seen. My first impression is less of a death-defying performer than a young man harboring delusions, but time will tell.

As for the Donald, he was away campaigning to save the nation. Hearing of the incident, he tweeted, “Great job today by the NYPD in protecting the people and saving the climber.” But he is no stranger to lawsuits. Will he sue? One hopes not. Mr. Rogata seems like a rather trivial target, and harmless; he should be let alone.

A forbidden zone of a very different kind has emerged in the reed-choked interior of Spring Creek Park in Howard Beach, Queens, where Karina Vetrano, an attractive 30-year-old woman, went for an evening jog along a three-mile fire trail on Tuesday, August 2, and never came out. Her parents reported her missing, and her father and the police began searching the area. That evening her father found her body face down near the trail. She had been sexually assaulted, and strangled with such ferocity that the killer’s hand prints were visible on her neck.

The region is known to local residents as the Weeds, an isolated area where homeless people camp, and teen-agers ride illegal all-terrain vehicles and party. It has long been said in Howard Beach, “You don’t go in the Weeds by yourself.” The police have offered a $25,000 reward for information leading to the capture of the killer, and the victim’s family have made a novel offer to the killer himself: if he surrenders and confesses, the more than $250,000 they have raised through donations to a reward fund will go to anyone he chooses. Meanwhile the police have asked men frequenting the area to voluntarily provide oral DNA swabs, so they can compare them with DNA evidence left by the killer and eliminate suspects. They have received many tips and are following up on several, but so far no arrest has been made.

The fire trail is lined by tall invasive reeds known as phragmites, which I know well from the nearby Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, where it grows thick like a jungle and can attain a height of 16 feet. It is almost impenetrable; to clear it so as to create or maintain a fire trail, requires machetes. Until now, I thought phragmites posed a danger only if, in a dry season, it caught fire; at Jamaica Bay I have seen acres of blackened stubble, and once, in the distance, smoke from a spreading fire. I have seen phragmites also in a damp area at Van Cortland Park, where there are narrow paths leading deep into it – paths I would just as soon not follow.

Even before the recent murder, the Weeds at Howard Beach seemed dangerous, for last summer a local resident was found there hanging from a tree, a suicide. Dog walkers now avoid the area, not to mention runners. Truly, a forbidden zone, and for good reason.

My poems: For five acceptable poems, click here and scroll down. To avoid five terrible poems, don't click here. For my poem "The Other," inspired by the Orlando massacre, click here.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: Maybe Rose, the quintessential Brooklynite. Maybe Sailors' Snug Harbor, Staten Island. Maybe both, but separately, in time.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on August 21, 2016 05:14

August 14, 2016

249. Wall Street: A Roman Orgy, Greed, and "Bro Talk"

Wall Street, that citadel of wealth, has always had a bad press. Back in 1849 George G. Foster, a New York Tribune journalist, in his anonymously published New York in Slices, hailed it as the great purse-string of America, but went on to decry “the million deceits and degradations and hypocrisies played off there as in some ghostly farce.”

Wall Street! Who shall fathom the depth and the rottenness of thy mysteries? Has Gorgon passed through thy winding labyrinth, turning with his smile every thing to stone – hearts as well as houses? Art thou not the valley of riches told of by the veracious Sinbad, where millions of diamonds lay glistening like fiery snow, but which was guarded on all sides by poisonous serpents, whose bite was death and whose contact was pollution?

Foster knew his Greek mythology and Arabian Nights, but he also knew Wall Street. And this was in 1849, before the likes of Daniel Drew and Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jim Fisk and Jay Gould – remembered today as robber barons – had hit their manly stride, manipulating and convulsing markets in their lust for riches and their delight in turning Wall Street and foreign markets upside down.

Of course all that was back in the nineteenth century, before even a hint of government regulation, back when laissez-faire was played to the absolute limit. And today? Let’s have a look.

By “Wall Street,” as I explained in the previous post, I don’t mean just the street itself, but the whole financial community, whether headquartered literally on Wall Street or in some more remote location, including even—to the indignation of New Yorkers – the barrens of New Jersey, that decidedly unimperial hinterland across the Hudson that constantly schemes to entice businesses away from the Empire State, even while insidiously laying claim to the Statue of Liberty and sending us its hordes not of immigrants but mosquitoes.

So what about Wall Street, in this larger sense, today? Let’s begin with Tyco International, a security systems company whose CEO and CFO (chief financial officer) were found guilty here in 2005 of stealing more than $150 million from the firm. And what had Dennis Kozlowski, the CEO, done with these ill-gotten funds? Here’s a sampling that came to light at his trial:

· A $30 million Fifth Avenue apartment· A $6,000 gold-and-burgundy shower curtain· A $15,000 dog umbrella stand· Paintings by Renoir and Monet worth millions· A multimillion-dollar oceanfront estate on Nantucket· $1 million in 2001 to pay half the cost of the 40thbirthday party for the second Mrs. Kozlowski on the island of Sardinia, a party featuring helmeted gladiators to welcome arriving guests, toga-clad waiters crowned with fig wreaths, wine served in chalices, and an ice statue of Michelangelo’s David pissing vodka. (Mrs. Kozlowski later filed for divorce.)

Born in Newark, N.J., in 1946 to second-generation Polish-Americans who worked for the city, Mr. Kozlowski was a good example, if not of rags to riches, at least of a rise from modest beginnings to dazzling financial success. Photos of him show a man in his sixties with an oval-shaped head, quite bald, and a hearty grin. His lavish life style came to symbolize the decadent luxury of high-living Wall Street and hastened his downfall, since videos of the party were shown to jurors, who saw dancing women and near-naked male models cavorting with guests, and a beaming Kozlowski promising guests a “fun week” with “eating, drinking, whatever. All the things we’re best known for.”

Mr. Kozlowsi’s celebrated “Roman orgy” recalls impresario and financier Jim Fisk’s reputed revels with scantily clad Opera House dancers and free-flowing champagne in the late 1860s, except that those revels may never have happened, whereas Mr. Kozlowski’s are well documented. The famous shower curtain landed him on the cover of the New York Post under the headline “OINK, OINK.”

In a 2007 interview he maintained his innocence, arguing that jurors, hearing that he was making $100,000 a year, must have thought, “ ‘All that money? He must have done something wrong.’ I think it’s as simple as that.” After serving eight years, he was paroled in January 2014 and now lives modestly in a two-bedroom rental overlooking the East River with a nondescript white shower curtain and wife #3.

But there’s more to Wall Street than living high on the hog. Cliché though it is, how about greed? In our capitalist economy, it can take you very far. My post #150, “Wall Street Greed and Addiction” (October 26, 2014), draws on reminiscences of former hedge-fund trader Sam Polk, published as the article “For the Love of Money” in the New York Times of January 19, 2014. When, at 22, Polk first walked onto a trading floor in Boston to begin a summer internship, he was dazzled – not by a floor of screaming, frenzied traders, as it was not so long ago – but by the glowing TV screens, high-tech computer monitors, and phone turrets of today. Instantly he knew that this was what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

Three weeks after his internship ended, his girlfriend dumped him, saying, “I don’t like what you’ve become.” But when, now a trader, he got his first end-of-the-year bonus of $40,000, he was thrilled until, one week later, another trader only four years his senior was hired away by another outfit for $900,000 a year, 22 times the size of his bonus. Envy consumed him, and the thought of how much money was available. Four years later, at 25, he was making $1.75 million a year, but he began to notice the greed and selfishness of most traders, and realized that, for all his outsized salary, he wasn’t doing anything useful or necessary to society. So he got out.

But he was addicted to greed. He would wake up in the middle of the night, terrified by the thought of running out of money, of later regretting his giving up his one chance to be someone important. But in time he overcame his addiction and began speaking in jails and juvenile detention centers about getting sober, and doing other public services to help the underprivileged. The implied conclusion of his story: Can Wall Street greed become an addiction? The answer: yes!

And from the same reformed hedge-fund trader, Sam Polk, came a more recent article in the Times of July 10, 2016, entitled “How Wall Street Bro Talk Keeps Women Down.” If the previous post on the difficulties of women wanting a Wall Street career needs confirmation, here it is. Polk tells of going to dinner with a director and client when he was a bond trader at Bank of America, and hearing the client announce, once the waitress was out of earshot, “I’d like to bend her over the table and give her some meat.” Polk forced a smile, later fumed because he hadn’t said anything about the comment. Having heard men objectify women all his life, Polk asserts that this everyday sexism was nothing compared to the “bro talk” he witnessed on Wall Street. Women have written articles and challenged the norms, but the men have done little or nothing, preferring to be in the “in” crowd, to enjoy the camaraderie of like-minded males. Success on Wall Street depends on “fitting in,” on becoming one of the guys. For Polk, Wall Street is not a swashbuckling, take-no-prisoners culture, but a culture of brutal conformity; not to conform is to throw away millions of dollars in future earnings. Which means, I suspect, that the culture won’t change easily, or soon.

A personal aside: I have known since grade school that men talk differently among themselves, broaching matters not mentioned in mixed company. I learned this when my father took me to his gun club, where sportsmen gathered for trap shooting. Every once in a while my father would announce to some of his acquaintances there, "I heard a good one the other day." Then, in a lowered voice so I couldn't hear, he would tell his story to a circle of listeners, who would soon erupt in laughter. Yes, men at all ages talk differently among themselves. By my early teens I knew that I could talk books and theater with my mother, and crime, sex, and politics with my father. But what Sam Polk reports about the "bro talk" of Wall Street seems to cross some hidden line.

Does the Donald pay taxes? This is the question posed by the lead article of the Business Section of the New York Times of August 12, 2016. Of course we don't know, since he hasn't released his tax returns, but the article makes it clear that, as a big-time real estate operator, he could quite legally pay little or no taxes. Why? Because the tax code is full of overly generous tax breaks for developers, and he'd be a fool not to take advantage of them. Which simply supplements my post #157 of December 14, 2014, "Taxes: Who Pays Them and Who Doesn't." As for who doesn't (mentioned at the end of the post), you might be surprised.

My poems: For five acceptable poems, click here and scroll down. To avoid five terrible poems, don't click here. For my poem "The Other," inspired by the Orlando massacre, click here.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: Forbidden Zones. What places, past and present, have been denied to New Yorkers, and why.

© 2016 Clifford Browder

Published on August 14, 2016 05:04

August 7, 2016

248. Women of Wall Street

What I meant to be a single post on Wall Street (again!) got longer and longer, and finally split in two. So this post is about women on Wall Street. The next one will be about Wall Street otherwise – not a history, just a quick take on my impression of it today. It might be more logical to do them in reverse, but let’s face it, these girls kind of grabbed me. Have you heard of Abby Joseph Cohen? Or Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin (whom I’ve covered before)? Or Hetty Green, the “Witch of Wall Street”? Hang on, here they come.

Wall Street is thought to be mostly a male world where financial Titans, or would-be financial Titans, maneuver, scheme, or claw their way to success, “success” meaning a vast fortune, two or three beautiful wives (sequentially), and national or international repute. But there are women on Wall Street, too, as this post will make clear. But first, a word of caution: by “Wall Street” I don’t mean just that little street that begins on the west across Broadway from Trinity Church, whose pious chimes sound futilely on the financial brouhaha, and then runs east a few blocks to the East River, where sailing ships once thrust their prows over a busy waterfront jammed with carts and piles of merchandise being received from or shipped abroad. By “Wall Street” I mean the whole financial community, whether headquartered on Wall Street or not.

And the women of Wall Street? Years ago I used to read, in Barron’s, the self-proclaimed leading source for market news and analysis, the semiannual survey of a dozen or so leading analysts of the day, who gave their views on the current and future state of the markets, what securities to buy or sell, and so forth. To be among the dozen so chosen was certainly an honor, and usually there were two or three women at the top of their field, and often fairly young and attractive. But my favorite was Abby Joseph Cohen, who is now a partner and senior U.S. investment strategist at – of all places – Goldman Sachs, the vampire squid of my post Abby was no glamour puss; photos showed a woman in her early forties, New York-born and obviously Jewish, with short, curly hair and glasses, a Brooklyn mama (she was in fact from Queens), married, with two daughters. Nothing stylish about her; she seemed like one of us. Except, of course, for her Street smarts, meaning Wall Street smarts: her uncanny ability to predict the raging bull market of the 1990s, which won her national, if not international, acclaim. Alas she was a perennial optimist and bull, and as such failed to predict the disastrous bear market of 2000, and the even more disastrous crash of 2008.

Well, who’s perfect? I liked her anyway; she struck me as being for real, down-to-earth, a sort of Bella Abzug of finance. And Ladies Home Journal likes her, too; in 2001 it named her as one of the thirty most powerful women in America. And Abby’s advice today, at age 63? U.S. stocks are the best place to be; the S&P 500, widely seen as the best indicator of the general market, should end the year at 2100. That prediction was made in January 2016, with the S&P around 1800; the S&P 500 is now at 2166. Not bad, Abby; but the end of the year is still far off, and in an election year at that.

Wall Street has always been male-dominated, but even in Victorian times some women invested on their own. During the Civil War boom in the North, when the public flocked to Wall Street to speculate in stocks and gold, fancy carriages were seen there with affluent women reclining on cushions inside, while sending a servant to fetch the latest prices. (No Internet in those days, and no telephone either.) One wonders how their spouses felt, when they reported dramatic gains in the market. And one wonders how they fared when the boom, as all booms must, went bust.

Those women were only investors, but in 1870 Wall Street was astonished when Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin, two fiery feminist reformers of the day, opened a brokerage office and began trading stocks; gentlemen flocked to get a close look at what the press labeled “the bewitching brokers” (they were, in fact, young and attractive). But how, many wondered, could these two young women do so well on the Street, where so many males went bust? The answer came when a reporter interviewed them in their suite at the fashionable Hoffman House and noticed a portrait on the parlor wall of Commodore Vanderbilt, the richest man in the country, and under it a framed motto: “To Thy Cross I Cling.” Old Eighty Millions was obviously giving them tips and advice, until their shenanigans caused him to distance himself, at which point their income plunged, and they moved to less stylish quarters and ceased to be a wonder on Wall Street. (For the full story of the fiery twosome, see posts #39 and #40, December 23 and 30, 2012, or chapter 14 in my book.) Hardly an encouraging sign for the future of women on Wall Street.

But then came Hetty Green (1834-1916), the so-called “Witch of Wall Street,” who was born Henrietta Robinson of a wealthy Quaker whaling family in New Bedford, Massachusetts, from whom she inherited a large fortune. An only child, in her early years her father and grandfather taught her to invest shrewdly, reading her stock market prices the way other parents read their children bedtime stories. Suspicious of men eager to marry her because of her growing wealth, in 1867, at age 33, she married Edward Henry Green of a wealthy Vermont family, but only after making him sign a prenuptial agreement renouncing all rights to her money, which shows that she was one smart cookie. They would have a son and a daughter.

Moving into her husband’s home in Manhattan, Hetty began investing on her own, devising a strategy she stuck to all her life: conservative investments cash reserves to see her through market fluctuations a cool head during market turmoilThe result: she engaged in real estate deals, bought and sold railroads, in bad times made loans to banks and municipalities, raked in millions. Had our big banks followed her strategy, the financial convulsion of 2009 would have been much less severe, or maybe wouldn’t have happened at all.

But what kind of a woman was Hetty Green? Photographs show a hefty older woman, full-faced with a solemn look, no frills whatsoever (she was raised a Quaker), always dressed in black, which helps account for her name “the Witch of Wall Street.” She was stingy too, and it became legendary. Worth millions, she rode in an old carriage, wore a ragged old black dress and underclothes until they were worn out, lunched on graham crackers or dry oatmeal, never turned on the heat or hot water. It is said that she once spent half the night searching her carriage for a lost postage stamp worth two cents. But when, during the Panic of 1907, the city of New York appealed to her for a loan, she wrote a check for $1.1 million and took her payments in short-term bonds. A widow, in her later years she moved about from one small unheated apartment to another in Brooklyn Heights and Hoboken, New Jersey, hoping to escape the notice of the press and tax collectors. But in a rare interview she said,

But what kind of a woman was Hetty Green? Photographs show a hefty older woman, full-faced with a solemn look, no frills whatsoever (she was raised a Quaker), always dressed in black, which helps account for her name “the Witch of Wall Street.” She was stingy too, and it became legendary. Worth millions, she rode in an old carriage, wore a ragged old black dress and underclothes until they were worn out, lunched on graham crackers or dry oatmeal, never turned on the heat or hot water. It is said that she once spent half the night searching her carriage for a lost postage stamp worth two cents. But when, during the Panic of 1907, the city of New York appealed to her for a loan, she wrote a check for $1.1 million and took her payments in short-term bonds. A widow, in her later years she moved about from one small unheated apartment to another in Brooklyn Heights and Hoboken, New Jersey, hoping to escape the notice of the press and tax collectors. But in a rare interview she said,“I am not a hard woman. But because I do not have a secretary to announce every kind act I perform, I am called close and mean and stingy. I am a Quaker, and I am trying to live up to the tenets of my of my faith. That is why I dress plainly and live quietly. No other kind of life would please me.”

What kind acts she ever performed has escaped the scrutiny of historians.

In 1916, at age 81, Hetty Green died at her son’s home in New York, reputedly of apoplexy or stroke after arguing with a maid about the virtues of skimmed milk. Estimates of her wealth ranged from $100 to $200 million ($2.17 to $4.35 billion in 2016 dollars), making her the richest woman of the Gilded Age. She is buried with her husband in Vermont.

Yes, there have been women on Wall Street, and some of them, then and now, have done remarkably well. On July 29 of this year a financial thriller film entitled Equity opened, showing women not as demeaned assistants or hookers, but as female executives on Wall Street, including a heroine who announces early on, “I like money.” And who invested in the film, so that it could be made? Some 25 female investors, many of whom appeared in a photo in a New York Times article of July 24, some of them youngish and attractive, some of them older (it takes time to accumulate money); none of them an Abby Joseph Cohen, much less a Hetty Green, all of them well dressed and stylish.