Oxford University Press's Blog, page 9

February 19, 2025

Idiomatic pigs and hogs

According to an aphorism by Maxim Gorky, he who was born to crawl won’t fly. This is probably true of most other creatures. For instance, English speakers have great doubts about the ability of pigs to fly. Idiomatic sayings with pig are often amusing. See a few remarks on them in my posts for February 21, 2018, and for July 31, 2019 (and don’t neglect the comments). Some phrases cited below I have never seen except in dictionaries, for instance, to carry the wrong pig by the tail “to accuse a wrong person” (American slang) or to teach a pig to play on a flute “to do useless work.” As a lifelong educator, I have a fellow feeling for such music teachers.

A pig in clover is a very happy creature, but this should not surprise anyone, because from animals we borrowed the idea that to live in clover means “to live in luxury and be happy.” Living in bliss will resurface as an important theme below. Does anyone ever say: “He who scrubs every pig he sees will not long be clean” or “in less than a pig’s whistle” (that is, “at once”)? Is the second phrase the beginning of the enigmatic combination pigs and whistles? Anyway, idioms are like words: they are countless, and all of us know only a tiny fraction of them. For consolation, I do know what to put lipstick on a pig means, because I am adept at performing this task.

Anyway, I hope I am not milking a dead cow by repeating the same thing from one post to another. But few people realize that idioms are a relatively late dessert to our incredibly rich language. Words may be as old as the hills, but most phrases, like the ones cited above, were coined in the postmedieval period, that is, at an epoch we associate with the Renaissance. In the entire text of Beowulf, perhaps only one phrase has a figurative meaning. Chaucer is already half-modern, and Shakespeare is, in this respect, like us.

Medieval people could say and did say grass roots but would not have understood, let alone coined, a phrase like grassroots efforts. If they tried to sell a pig in a poke, they did exactly that. To put it differently, they were used to calling a spade a spade. A leap from putting a cat into a poke and palming it off as a pig to the feat of coining proverbial sayings with a figurative meaning took a good deal of time. This leap presupposed the new ability to speak in metaphors. As we now know, the last six centuries or so have been enough to flood us with idioms. The reward is that we can now kick the bucket and even beat about the bush while lying in bed.

The whole hog.

The whole hog. Photo by Ed van duijn on Unsplash.

Some of the most obscure phrases that inspired this post are connected with hog (that is why I began with pig). The origin of the phrases to go the whole hog and hog on ice have never been explained to everyone’s satisfaction, though some hypotheses sound reasonable. They are easy to find on the Internet and on this blog. The hardest question is whether hog in such idioms refers to the animal. Can we be dealing with some figurative meaning? For instance, cold pig used to mean “a suit of clothes returned to a tailor if it does not fit.” No explanation of this odd phrase exists. Why pig, and why cold? Perhaps one of the most obscure among such animal phrases is to live high off the hog, that is, in the lap of luxury.

I would like to return to the enigmatic phrase as independent as a hog on ice. Charles E. Funk spent years exploring the origin of this odd idiom. I would also like to note that quite a few of such phrases originated (or at least were first recorded) in American English, which means that they may go back to some obscure British words, once current only in dialects, later brought to the New World, and resuscitated almost by chance. In Joseph Wright’s multivolume The English Dialect Dictionary, two senses of hog (in addition to the main one) are given: “a heap of earth and straw used to store potatoes and turnips” and “a stone.” Stone in this context is also featured in the OED.

These are also hogs.

These are also hogs. Hay bales by Lluis Bazan via Unsplash; gray stone by Wolfgang Hasselmann via Unsplash.

The common denominator seems to be “a huge (unwieldy) object.” If hog ever meant “great property, accumulated wealth,” the odd phrase to live high off the hog would make sense. Hog is naturally associated with things huge and greedy, and the verb to hog means “to appropriate or take hold of something greedily” (as in “to hog the road.” The incalcitrant hog on ice may belong here too. I’ll quote the entry about hog, connected with hog “stone,” from the second (1914) edition of The Century Dictionary: “…by some identified with hog [animal name], as ‘laggard stones’ that manifest a pig-like indolence, or it might be thought, in allusion to the helplessness of a hog on ice, there being in the United States an ironical simile, ‘as independent as a hog on ice’. But neither this explanation nor that which brings Danish hok, a pen, kennel, sty, dock, is supported by any evidence. Perhaps first applied not to the stone, but to the long-score or line ‘cut on the ice. […] in the game of curling, the stone which does not go over the hog-score’…. [Scotch].”

Language historians know that words like bag, big, bog, bug, dig, dog, hug, lag, lug, rag, jig, jag, and so forth are usually obscure from an etymological point of view. Are they expressive coinages, baby words, or borrowings, changed beyond recognition? None of those hypotheses is improbable. Therefore, we need not assume that hog “animal name” and hog “stone” are related, even though they may be. People are probably apt to coin monosyllables like jig, bog, and hog many times. Some of those coinages stay, others lead a precarious existence in regional speech, and still others die without issue. The idiom to go the whole hog has not been explained either. I would like to suggest that hog here is, in principle, the same word as hog, applied to an unwieldy mass. The impulse for coining hog “swine” and hog “stone” must have been the same, but we are probably not witnessing two senses of the same word. Living high off the hog seems to belong with going the whole hog. There is nothing piggish about either.

As a final flourish, I may mention the fact that animal names should in general be treated with caution. I suspect that it is raining cats and dogs has nothing to do with animals (see my post for March 21, 2007), the objections in the comments, and the post for November 13, 2019, on the phrase to lie doggo. Everything is shaky in our world, and everything is in a state of flux. Knowing this, sleep well and let sleeping dogs lie.

Don’t buy a pig a poke unless you are a cat-lover.

Don’t buy a pig a poke unless you are a cat-lover. Left image: Schweinemarkt in Haarlem by Max Liebermann. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Right image: PGA – Currier & Ives – Letting the cat out of the bag. No known copyright restrictions. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

Featured image: Photo by Vaida Krau on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 16, 2025

The end of the “American Century”?

The end of the “American Century”?

“We Americans are unhappy,” is the opening line in a famous 1941 Life magazine article, in which Henry Luce called for Americans to harness the nation’s ingenuity as a benevolent force in the world. Partly aimed at the nation’s 1930s isolationism, his earnest exhortation to be imaginative and bold also spoke to a moment when decisive action might well turn the tide of the Second World War in Europe. The so-called American ideals that Luce identified include love of freedom, equality of opportunity, self-reliance, justice, truth and charity, among others. It is questionable whether Americans truly embodied all these values in 1941, but it mattered that they thought they did. That unshakeable confidence led to engagement with the wider world and a drive to create a better world.

It is hard to ignore the current dismantling of much of the moral rhetoric and internationalist sentiment that infuses Luce’s piece. American confidence is gone, and those ideals seem quaint and antiquated, begging the question: is the “American Century” at an end?

While our present government leadership may decry the ideals Luce identified, what is sometimes forgotten is the bipartisan agreement that led to this stance. Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points speech and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s wartime leadership are common knowledge, but few realize that Herbert Hoover, Republican president from 1929-1933, at one time embodied the birth of the American Century and the nation’s ambition to be a power abroad.

Hoover certainly was not a charismatic orator, nor was he an intellectual or a military leader. Born in Iowa in 1874 and orphaned as a small boy, he moved to live with Quaker relatives in Oregon, where he began work at 14. After passing the entrance exam for the new Stanford University, Hoover graduated with a geology degree, working to pay his way through college. This early habit of hard work continued in his engineering career and eventually led him to a personal fortune by the time he turned 40. This is when Hoover turned to public service.

The United States remained officially neutral in 1914 when war broke out, but that did not mean it was inactive. Americans intervened aggressively in wartime trade disputes, supplied armaments, and under Hoover’s watchful eye, fed nine million Belgian and French civilians. By the time Hoover’s multiple agencies—public, private, mixed—wound down a century ago, the United States had provided food, material relief, and medical aid to two dozen European countries. Hoover oversaw the massive American Relief Administration and European Children’s Fund, making him a household name, and along with Wilson, the face of the US abroad.

While relief workers pursued a mission to save and improve the world, millions of Americans started learning the fundamentals of “Western Civilization” in newly created, uniquely American university classes. US intervention abroad supplemented a new interest in collecting and teaching the cultural heritage of other nations, helping to construct a historical narrative in which Americans had reached the pinnacle of progress.

This was new. The 1917 American Expeditionary Force marked the first large-scale US intervention in a global conflict. Nearly simultaneously, the nation funded massive relief programs, leading to a need to redefine American identity. Did they have moral authority, and if so, on what was it based? Were they uniquely placed to bring efficiency and technological knowhow to an ailing world? Why should Americans act to ameliorate suffering of strangers? American loans, agricultural surpluses, and transport capacity all supported US claims for supervision of a return to normalcy after conflict. Postwar loans bankrolled the world, in the process creating wealth for many in the United States.

Propaganda campaigns broadly publicized US generosity and humane leadership, creating a sense of what it meant to be an American in a globalizing world. Domestic efforts to improve society in the Progressive era now found new fields of operation abroad, creating a kind of international classroom for Americans to rescue those in need of help. Modern advertisements made it clear to Americans that not only did food provide sustenance but it was a principled imperative for a democratic nation—wealth begat responsibility. This rhetoric echoed Americans’ own sense of their mission to save the “Old World,” so it resonated with both volunteers and ordinary donors to the cause.

By the 1920s, Americans conceived of their own nation’s citizens as modern, progressive, rational, neutral, and efficient. They juxtaposed these qualities with a Europe in tatters, one that had squandered its modernity and for whom the war served as proof of its moral and political bankruptcy. By making explicit the connection between US governmental relief and American expertise, aid workers echoed the increasingly coherent rationale of US moral responsibility to model democracy for others. Rescuing a grateful world had become central to an American global mission and self-identity and thus began the American Century.

As the current Trump administration moves speedily to defund and discontinue various aspects of foreign aid, the United States is sending a message that it no longer sees itself as a global power for good. Hoover’s organizations created a model that saved lives and created a market for surplus food that American farmers had produced, helping to bolster prices and to reduce stocks of army rations and grain. This coalition brought together missionaries, reformers, financial institutions, diplomats, and farmers for the purpose of aid and development. Hoover fervently believed that food aid encouraged global stability and created a positive image of the United States abroad, and this idea, echoed by later presidents such as Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower, was a central value of the “American Century.” In 2025, it appears the United States is ending that century-long commitment to foreign responsibility.

Featured image by Jakob Owens via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 15, 2025

Half a century with OUP: remembering Bill Leuchtenburg (1922-2025)

Half a century with OUP: remembering Bill Leuchtenburg (1922-2025)

In 2003, historian William E. Leuchtenburg signed a contract with OUP for a trade book on the executive branch. It was to be 60 to 80,000 words, 200 printed pages, due September 2005. Because he had two other large book projects underway, Bill did not make that date. A few years later, I attended the annual dinner of the Society of American Historians, one of those classic rubber chicken banquets held at the Century Association. During the cocktail hour, I chatted with Bill, who immediately brought up his undelivered project.

Bill noted dolefully that he no longer had an editor at OUP; Nancy Lane and Sheldon Meyer had both retired; Tim Bartlett, who signed the book, and Peter Ginna, who inherited it, had both left the Press; he was orphaned. “Bill,” I said, “I’d be honored to be your editor.” Like so many generations of history students, I’d read The Perils of Prosperity, 1914-1932 and the visage of William E. Leuchtenburg was carved into the Mount Rushmore of American historians. Now I would have the privilege of editing him.

When the manuscript arrived, I knew immediately what an accomplishment it was, albeit a hefty one: 325,000 words, in draft; it came out at 886 pages. Yet it was a joy to edit—polished, expansive, an insightful illumination of the executive office and those who occupied it. It was masterful and majestic.

“It has been said that no one writes big-picture history anymore,” Niko Pfund, OUP USA’s own president, wrote in the jacket copy. “But in The American President—the capstone of a storied career—Bill Leuchtenburg serves up popular history at its best. An exemplar of narrative history, it will stand as the definitive account of the twentieth-century American presidency.”

Capstone, perhaps, but Bill still had another book in him. Though he was nearing the century mark—perhaps because of it—he wanted to work his way backward in history and write the history of the presidency from the beginning. He would start with the first six chief executives, in what became Patriot Presidents (2024). As with Bill’s other books, the research behind it was deep, the writing elegant and witty, yet Bill, learned as he was, never condescended. He was, his UNC history colleagues once wrote in a tribute, “a model of public engagement.”

He remained throughout his life the kid from Queens. Nowhere is this more evident than in the essay on the borough that he contributed to American Places, the volume of essays he edited in honor of Oxford editor Sheldon Meyer’s retirement. Here we learn that, as the son of immigrants, Bill grew up in Queens but always focused his attention on Manhattan. Only later did he look at Queens as a historical subject, which he did with grace, humor, and hometown pride. Above all, it is a paean to American immigration, noting that his Elmhurst neighborhood had become the most ethnically diverse ZIP Code in the country. When he mentions spending an afternoon with Governor Mario Cuomo chatting about their shared hometown, he is matter of fact; there is not an iota of boastfulness.

After The American President came out in 2015, we invited Bill to talk to the OUP staff about his book. He chose to talk not about the Presidency but rather about his long association with OUP. (I should note that Bill, the avid baseball fan, pitched a double-header that day; he went across the street to deliver an evening lecture at the Morgan Library.)

The story began in Grand Central Station in 1973. Bill was standing in line to buy tickets for a family trip. Henry Steele Commager, his Columbia colleague, came running up. Commager was co-author, with Samuel Eliot Morison at Harvard, of the two-volume, 2,000-page The Growth of the American Republic (first edition, 1930), what Bill called “the most celebrated textbook ever written.” Commager and Morison, he said, had decided that the next edition would be their last. They needed a third historian to take it over, and they chose Bill. He had some apprehension about his working relationship with Morrison. In his words:

In fact, Admiral Morison was a thoroughgoing professional. He had read my writing and believed he could trust me. He was also extraordinarily conscientious. From his home in Northeast Harbor, he would send detailed comments on my revisions to my editor at Oxford, Nancy Lane, and I would receive an onion skin copy at my home in Westchester County the next day:

Page 876, line 14. Not “Therefore” but “Hence.”

One day Nancy phoned me and said Morison had raised an objection to a particular sentence. It alluded to one Madame Jumel “who used to boast that she was the only woman in the world who had been embraced by both Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte.” I understood why that might be too raunchy for Morison, a Boston patrician well on in years. And for the next twenty-four hours I awaited with some trepidation the arrival of the onion skin. When I opened the envelope the next day, I read his words: “Strike ‘embraced.’ Insert ‘slept with.’”

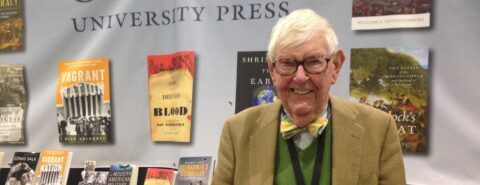

William Leuchtenburg visits the Oxford exhibition booth in 2016.

William Leuchtenburg visits the Oxford exhibition booth in 2016. Photo by Nancy Toff.

In addition to the work on the textbook, Bill became an advisor and then a “surrogate delegate” (as US delegates were known in those high-imperialist days). He credits OUP’s president at the time, Byron Hollinshead, with introducing him to the filmmaker Ken Burns. Bill served as consultant to Burns’s film on Huey Long and went on to work on The Roosevelts, Jackie Robinson, and several other films.

Another key figure in Bill’s relationship with OUP was the aforementioned Sheldon Meyer, with whom he published The Supreme Court Reborn. As he explained, “In these same years, I sent a stream of dissertations from students in my Columbia PhD seminar to Sheldon—and so Allan Brandt, Bill Chafe, Harvard Sitkoff, and a number more became Oxford authors. That was good for Oxford and very good for my students who started their careers with a first book under the imprint of a highly prestigious publisher.” Bill and Sheldon shared a love of baseball and jazz, and they partied well: “I remember especially Sheldon’s very keen eye for exceptional restaurants.”

When I inherited Bill, we were no longer in the fancy-dinner era, but we nevertheless became fast friends. He was both gracious and practical when it came to the nitty-gritty of the editorial process. He appreciated that second set of eyes (or in his case, third, since his wife, Jean Anne, had already taken her turn); he took advice gratefully, even when it meant cutting 30 pages from one chapter.

He considered his editors part of the family, and there were always long personal notes on Christmas cards and photos of his beloved Labradoodle Murphy, who accompanied the Leuchtenburgs as they delivered fresh vegetables to their neighbors during the pandemic. He observed that the children liked Murphy much more than the broccoli. When I called him to tell him I was retiring, he responded in character: He sang Cole Porter’s “You’re the Top”—all the verses, perfectly. He was then 102. Back at you, Bill!

Featured image by Nancy Toff.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 14, 2025

Nature’s landscape artists

Claude Monet, c. 1899. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Claude Monet, c. 1899. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Claude Monet once said, “I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers.” Perhaps he should have given bees equal credit for his occupation. Without them, the dialectical coevolutionary dance with flowers that has lasted 125 million years would not have produced the colorful landscapes he so cherished. For Darwin, it was an abominable mystery; for Monet, an endless inspiration.

Bees, like Monet, paint the landscape. Their tool kit, however, is not one of canvas, paint pigments, and brushes, but consists of special body parts and behavior. Their bodies, covered with branched hairs, trap pollen when they rub against floral anthers and transfer it to the stigma—pollination. Their visual spectrum is tuned to the color spectrum of flowers, not an adaptation of the bees to flowers but an adaptation of flowers to attract the pollinators. Insects evolved their color sensitivities long before flowering plants exploited them.

Monet’s ‘Le jardin de l’artiste à Giverny,’ 1900. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Monet’s ‘Le jardin de l’artiste à Giverny,’ 1900. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The behavioral toolkit of honey bees is expansive. Bees learn the diurnal nectar delivery rhythms of the flowers; they also learn their colors, shapes, odors, and where they are located. Honey bees are central-place foragers, meaning they have a stationary nest from which they explore their surroundings. They can travel more than 300 km2 in search of rewarding patches of flowers. To do this, they have a navigational tool kit. First, they need to know how far they have flown: an odometer. This they accomplish by measuring the optical flow that traverses the nearly 14,000 individual facets that make up their compound eyes, similar to us driving through a city and noting how much city flows by in our periphery. They calculate how far they have flown and the angle of their trajectory relative to the sun, requiring a knowledge of the sun’s location and a compass. Then they integrate the individual paths they took and determine a straight-line direction and distance from the nest. Equipped with this information, they return to the nest and tell their sisters the location of the bonanza they discovered.

Bee dance diagram. Emmanuel Boutet, CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bee dance diagram. Emmanuel Boutet, CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Communication among honey bees is not done with airborne sounds, as they have no organs for detecting them. Information is conveyed through a dance performed by returning foragers on the vertical surface of a comb in a dark nest. New recruits gather on the comb dance floor, attend the dances, and learn the direction and distance to the patch of flowers. How they perceive the information in the dance is not known, but to us as observers, we can decipher the direction by the orientation of the dance, and the distance by timing one part of it. Because the dance is done on a vertical comb inside a dark cavity, perhaps a hollow tree or a box hive provided by a beekeeper, the forager has two challenges. First, she must perform a bit of analytical geometry and translate the angle of the food source relative to the location of the sun from a horizontal to a vertical plane, then she must represent the direction of the sun at the top of comb. This is a constant like north at the top of our topographical maps.

Walker canyon wildflowers. Mike’s Birds, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Walker canyon wildflowers. Mike’s Birds, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Equipped with this information, recruits fly out of the nest in the direction of the resource for the distance indicated by the dance and seek the flowers. The flowers lure them in with attractive colors, shapes, odors, and sweet nectar that the bees imbibe and in the process transfer pollen onto the stigma, fertilizing the ova. The seeds develop, drop to the ground and wait until the following spring when the plants emerge and paint the fresh landscape with a kaleidoscope of colors that rivals Claude Monet.

Featured image by JLGutierrez on iStock.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 13, 2025

Thomas Wentworth Higginson and the freedom jubilee

Thomas Wentworth Higginson and the freedom jubilee

“Colonel Higginson was a man on fire,” read one obituary. “He had convictions and lived up to them in the fullest degree.” The obituary added that he had “led the first negro regiment, contributed to the literature of America, and left an imprint upon history too deep to be obliterated.” Thomas Wentworth Higginson would have been pleased to have been referred to as “colonel.” He was proud of his military service and happily used the title for many decades after the end of the Civil War and up to his death in May 1911 at the age of eighty-seven.

Nonetheless, his time in the army was just one of many things for which he hoped to be remembered. “I never shall have a biographer, I suppose,” he mused to his diary in 1881. Just in case somebody took up the challenge, however, he wished to provide a hint about his career. “If I do” find a chronicler, he wrote, “the key to my life is easily to be found in this, that what I longed for from childhood was not to be eminent in this or that way, but to lead a whole life, develop all my powers, & do well in whatever came in my way to do.”

Yet while it was a life marked by numerous struggles for social justice and progressive causes, from abolitionism to women’s rights, from religious tolerance to socialism, and from physical fitness for both genders to temperance, there was one moment from the days he served as colonel to the 1st South Carolina Infantry that meant so much to him that he wrote about it with great clarity in later years.

Higginson’s regiment was comprised solely of contraband troops, enslaved Americans who had fled toward Beaufort, South Carolina, which had been captured by the United States in November 1861, from northern Florida and coastal Carolina. When Higginson first arrived in Beaufort in December 1862 to take charge of the troubled regiment, the recruits and their families remained under military protection, but news of the Union disaster at Fredericksburg led him to fret about their fate should the Confederacy ultimately prevail.

The first of January 1863 arrived, and with it the promise of President Abraham Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation. To properly commemorate the day of jubilee, General Rufus Saxton, the military governor of the Department of the South, issued an order entitled “A Happy New Year’s Greeting to the Colored People” of South Carolina, together with an invitation to a celebration at the regiment’s camp. The steamers Flora and Boston ferried freedpeople from the liberated Sea Islands to Beaufort’s docks, and from there the band from the 8th Maine led the procession to the 1st’s drilling grounds in an oak grove behind an abandoned mansion. A low stage had been hastily erected. Saxton sat toward the rear with Dr. William Henry Brisbane, a federal tax commissioner, and Reverend Mansfield French, who had arrived on the coast as a teacher. Higginson stood on the edge of the stage, flanked by his two favorite Black officers, Sergeant Prince Rivers and Corporal Robert Sutton. Laura Towne, a Philadelphia teacher and abolitionist, found a seat amidst the “dense crowd.” Higginson, she thought, though “tall and large man as he is,” appeared “small” when standing between his two color bearers.

The ceremony began promptly at 11:30 with a prayer from Chaplain James Fowler. Brisbane next stepped forward to read the president’s proclamation. Higginson considered that especially appropriate, as the South Carolina-born Brisbane had converted to abolitionism and carried his slaves to freedom in the North. French then presented Higginson with a new regimental flag he had obtained in Manhattan, a fact he had “very conspicuously engraved on the standard.” Thinking the day should be for Black Carolinians, that act and French’s praise of white New Yorkers left “a bad taste” in Higginson’s mouth.

But then “followed an incident so simple, so touching, so utterly unexpected & startling” that he could scarcely believe it. Just as Higginson received the flag and began to speak, an “elderly male voice” from the front row began to sing, “into which two women’s voices immediately blended.” The first words of what Higginson thought almost hymnlike floated above the crowd: “My county ‘tis of thee, Sweet land of Liberty.” Those on the platform began to join in. Higginson turned, shushing: “Leave it to them.” The freedpeople in the audience finished the song, with Higginson gazing down at them. Dr. Seth Rogers remembered that Higginson was “so much inspired” that he “made one of his most effective speeches.” Higginson thought otherwise. The day marked the first moment “they had ever had a country, the first flag they had ever seen which promised anything to their people,” he marveled, and “here while others stood in silence, waiting for my stupid words, these simple souls burst out.” The “choked voice of a race [was] at last unloosed,” and nothing he might say could match that eloquence. But he thought both Rivers and Sutton spoke “very effectively,” and the entire regiment sang “Marching Along.” The day ended with a barbecue of twelve roasted oxen and, as the temperance-minded colonel approvingly noted, “numerous barrels of molasses and water.”

Higginson was mustered out in November 1864 after being badly wounded during an upriver raid designed to liberate Confederate lumber and enslaved Carolinians. “Emerson says no man can do anything well who did not feel that what he was doing was for the time the centre of the universe,” Higginson reflected as his days on the Carolina coast drew to a close. He devoutly believed that no “brigade or division in the army was so important a trust as [his] one regiment—at least until the problem of negro soldiers was conclusively solved before all men’s eyes.” And although he ever depreciated his courage in contrast with that of the Black men who risked everything to serve, Higginson did think himself forever united with his men, as he put it in “A Song From Camp”:

“And the hands were black that held the gun,

And white that held the sword,

But the difference was none and the color but one,

When the red, red blood was poured.”

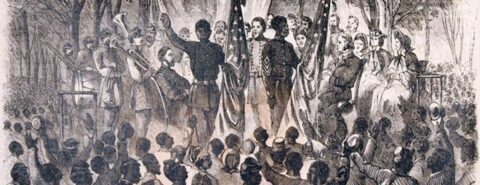

Featured image by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 12, 2025

Dwarf and its past

First, my thanks to those who wrote kind words about my most recent essays. Especially welcome was the comment that sounded approximately so: “I understand almost nothing in his posts but always enjoy them.” It has always been my aim not only to provide my readers, listeners, and students with information but also to be a source of pure, unmitigated joy. Also, last time, we could not find a better image of Fafnir for the heading, but Sigurth killed the dragon from the pit in which he (Sigurth) had hid himself. And of course, only a very silly man would attack a fire-breathing dragon naked.

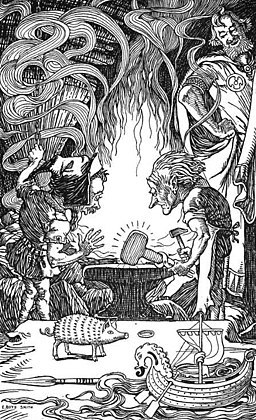

At work on Thor’s hammer.

At work on Thor’s hammer. Elmer Boyd Smith (1860-1943), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

And now to business. Someone who will take the trouble to follow the history of etymological research may come to the conclusion that as time goes by, we know less and less about the origin of some words. The earliest dictionary of English etymology, by John Minsheu, was published in 1617. The latest Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic by Guus Kroonen appeared in 2013, that is, roughly four centuries later. Both authors offered their suggestions on the origin of the word dwarf, and both, I am afraid, were wrong. Two years before Kroonen, Elmar Seebold, the reviser of Kluge’s German etymological dictionary (more about Kluge will be said below), summarized his opinion in the familiar terse sentence: “Origin unknown.” James A. H. Murray, the first editor of the OED, did offer a suggestion about dwarf. By contrast, the revised OED online gives a long entry on the word but refrains from conclusions. The revisers seem to be on the right path. Yet they treads it cautiously, perhaps because every statement in the OED is taken by the uninitiated as the ultimate truth and parroted. Better safe than sorry. But I can risk making a mistake and later apologize for it.

In my opinion, Friedrich Kluge discovered the origin of dwarf in 1883. Yet he soon gave up his hypothesis. I unearthed and defended it in a 2002 publication and later in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction (2008). Neither work can be found online, and nowadays, what does not appear on the Internet does not exist. Therefore, I am planning to advertise a few of my old suggestions in this blog and make them known to those who are ready to go beyond the information in Etymoline.

Dwarf is a Common Germanic word. It does not occur in the fourth-century Gothic Gospel, but in all probability, the Goths knew it, and it sounded as dwezgs in their language. Since generations of researchers have looked for the cognates of dwarf in what I believe was a wrong direction, they found nothing worth salvaging. To know the origin of a word, we, quite obviously, should know what the word means. It seemed obvious to many that the sought-for basic meaning is “something/somebody short (small).” This approach resulted in numerous fanciful hypotheses.

It so happens that all we know about the ancient Germanic dwarfs comes from Scandinavian sources. Dwarfs loom large in Old Norse myths and nowhere else until we encounter them in folklore, such as the Grimms’ tales. The age of such tales is impossible to determine: some may be echoes of ancient myths, others are probably late. The Old Scandinavian sources are not enlightening when it comes to the origin of dwarfs: dwarfs are said to have emerged like maggots from the flesh of the proto-giant. Why maggots? Because there were so many of them? Giants, whom the god Thor killed like flies, were also numerous, but relatively few of their names have been recorded, while a full catalog of Old Norse dwarfs contains, I think, 165 items! Most entries are just names, because their bearers don’t appear in any stories. Yet a few are famous. The most surprising thing is that all dwarfs are male, though a word for “female dwarf” existed.

“Dwarf Nose” by Wilhelm Hauff, a tale about a boy becoming a dwarf, and Nils Holgerson, the hero of another unforgettable boy-to-dwarf story, this time by the Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf.

“Dwarf Nose” by Wilhelm Hauff, a tale about a boy becoming a dwarf, and Nils Holgerson, the hero of another unforgettable boy-to-dwarf story, this time by the Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf. Image 1: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Image 2: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

A few facts are certain. Dwarfs were not small. Therefore, all attempts to find a clue to the origin of dwarf by looking for some related word meaning “little, short, tiny; midget” are doomed to failure. But a seemingly more appealing approach also ended up in a blind alley. Old Norse dwarfs were artisans and forged treasures for the gods. Yet words for this activity also fail to provide a convincing etymology of dwarf. And here I am coming to the culmination of my story.

The fourth sound of the old word dwerg– is r. Old Germanic r could go back to two sources: old r and old z from s. The change of z to r is called rhotacism (from the name of the Greek letter rho, that is, ρ), and the process seems to have occurred in the seventh or eighth century. A look at modern forms does not reveal the source of r, but compare English was and were. The forms are related, and r in were goes back z, from s. Or compare raise and rear. They are twins: raise is related to rear and to rise. Both mean “to make rise” (we raise our young and rear them). It is puzzling why raise does not have r at the end.

Elf Bow Arrow: Beware of elves and back pain.

Elf Bow Arrow: Beware of elves and back pain. Photo by Robin Parker, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

In 1883, Friedrich Kluge suggested that r in dverg– is the product of rhotacism and that the ancient root had been dwezg-, from dwesk-. Everything immediately became clear. The root dwes– appears in words like Dutch dwaas “foolish” and many others. The ancient dwerg– was once dwesg, an evil creature that made people insane, “dwaas,” and dizzy (the words are related). Elves had arrows and also gave human beings trouble (elf-shot means “lumbago”), while the gods made human beings giddy or “enthusiastic,” that is, “possessed” (the Greek for “god” is theós). The oldest myths advised people to stay away from the gods! Incidentally, dwarfs in folklore are also evil. How dwarfs became artisans and why they lacked female partners need not concern us here too much. In any case, they were not invented by the human imagination as midgets. Perhaps when, with time, they were associated with treasures and riches and when dverg– began to rhyme with berg “mountain,” popular imagination resettled them into the bowels of the earth, where space is at a premium. Then they began to be visualized as small (mere guesswork).

Most unfortunately, as early as in the second edition of his dictionary, Kluge gave up his idea, and it was forgotten. I pride myself on resurrecting it and hope that it will be accepted by those who care about such things. Therefore, when I read in the authoritative 2013 Germanic comparative dictionary: “I assume that the word was derived from the strong verb dwergan-, attested as Middle High German zwergen ‘to squeeze, press.’ The meaning ‘pillar’ and ‘staff’ in Nordic are believed by some to refer to the pagan belief that dwarfs carried the firmament,” I feel surprised and even saddened: zwergen, a rare and isolated verb, must have meant: “To be oppressed (as though) by dwarfs”: the German for “dwarf” is Zwerg. Show some enthusiasm for the medieval mentality and think of dwaas, dizzy, giddy, and elf-shot.

When all is said and done, four centuries of research have not been wasted, but the path to truth is never straight and narrow. The important thing is not to lose it.

Featured image: photo by jimmy desplanques on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 11, 2025

Frances Oldham Kelsey: fame, gender, and science

Frances Oldham Kelsey: fame, gender, and science

Frances Oldham Kelsey, pharmacologist, physician, and professor, found fame soon after she finally, well into her forties, landed a permanent position as medical reviewer for the Food and Drug Administration in 1961. One of the first files to cross her desk was for the sedative thalidomide (tradename Kevadon), which was very popular in Europe and other nations for treating morning sickness.

But Kelsey, along with the other pharmacologist and chemist on her team, found the New Drug Application (NDA) submitted by Merrill Pharmaceuticals to include incomplete, shoddy research, and she put off approving the drug until studies came out of Europe about thalidomide’s extreme toxicity to fetuses. Thousands of babies were born with no arms or legs, malformed hearts, and other defects.

By August 1962, Kelsey was feted in the national and international press for preventing the drug from general use in the United States, and added award dinners, interviews, speeches, and receptions to her already busy work schedule.

Yet behind the scenes, she had to gingerly negotiate around aggrieved colleagues who were overlooked for their efforts (as she was the first to admit). Worse yet, there were a series of FDA Commissioners and senior executives whose power and lofty titles didn’t translate to as much publicity as America’s Good Mother of Science. James (Go Go) Goddard, for instance, was highly miffed when the announcement of his nomination as FDA Commissioner was accompanied by a photo of Kelsey.

The fact that Kelsey was a woman certainly did not help. She had bumped her head on glass ceilings right through graduate school and beyond, when her fellow students attained university appointments and she did not. A career in science was a man’s game, as was the drug industry. A photograph of Kelsey and FDA colleagues explaining amended drug policies to pharmaceutical executives portrayed a sole woman facing down a sea of hostile men. But she persisted, confident in her training and knowledge, and true to her moral compass.

What was unique about Frances Kelsey in the 1960s was the seamless way she integrated all her roles. The stereotypical female physician or scientist of the time (and they were a minority) was unmarried, abrasive, and dispassionate. Dr. Kelsey was happily married to a fellow pharmacologist and was raising two teenaged girls.

She had lots of friends, entertained, played golf and tennis, gardened, and generally enjoyed life. Kelsey was also a resident physician at her daughters’ Girl Scout Camp in South Dakota. And she loved doing science—dissecting whale glands, studying rabbit embryos under the microscope, and reading up on all the latest research.

When she postponed approval of the Kevadon NDA, it was not based on her husband’s advice, or being too nitpicky, or even procrastination and the messiness of her desk, as some opponents and journalists charged, but due to her careful application of scientific methods.

Dr. Kelsey did not shy away from the Good Mother of Science label. She gave speeches to female students and interviews in women’s magazines about the potential dangers of using drugs in pregnancy, and also its necessity in some cases. She headed another FDA file relating to foetal health—the consequences of the administration of the estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES) to pregnant women in clinical trials, which resulted in serious injuries for many mothers and their children.

The American public appreciated all of these efforts, as they made evident in the thousands of pieces of fan mail they sent to Dr. Kelsey’s home and office. One theme ran throughout these letters, post cards, poems, and songs. It was not how can a woman be a scientist? It was why aren’t there more women in science doing great things for the benefit of all?

Featured image by National Cancer Institute via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 10, 2025

Discussing your research findings

Discussing your research findings

Most research articles in journals have a standard structure with sections entitled “Introduction,” “Methods,” “Results,” and “Discussion.” Each has a clear remit except for the Discussion, which, if you’re a less experienced writer, may seem a hopelessly vague description. The occasional alternative of “Conclusion” or “General Discussion” isn’t much better.

Uncertain what’s needed, some authors offer a summary of their results, or even of the whole work, though both are really covered by the abstract.

What, then, should you include?

Basic elementsThe following can all help the reader get more from your Discussion—and more from your article:

a reminder of the research probleman objective review of the resultsthe immediate implications of the resultsthe relevance to the field of the resultsthe limitations of the resultsa succinct conclusionBut not new results or methodological detail, which would be out of place here.

Research problemOpening with a reminder of the research problem sets the context for the Discussion and accommodates the different ways readers approach a research article, as explained shortly. But don’t repeat the wording from the Introduction. You’ve made progress since then, and it should be reflected in the way the problem is described.

Here’s an example from a civil-engineering article. First, in the Introduction, a simple statement:

Chloride-induced rebar corrosion is one of the major forms of environmental attack [on] reinforced concrete.

And then, in the Discussion (actually the Conclusion in this example), an elaboration:

Chloride ingress into concrete is a complex process, which in many environments is further complicated by the temperature cycles and wet-dry cycles experienced by the reinforced concrete structures. While there are numerous existing experimental or modeling studies …

This opening makes sense whether the reader works linearly through the report, jumps straight to the Discussion to decide if it’s worth reading the earlier sections, or moves from one section to another according to their interests at the time.

Review and implicationsExamine the Results section as if you were a neutral observer. Focus on the main findings, noting strengths and weaknesses, and any immediate implications. You don’t need to be exhaustive: some results will already have been routinely processed, for example, in control measurements; others may have been placed in an appendix or supplement, as required by the journal.

In considering the implications, strike a balance between claiming too much, which looks like boosterism (and alienates readers), and overprotecting what you do claim with too many instances of “may,” “might,” “can,” “could,” and so on, leaving readers with little sense of substance.

Depending on your research discipline, you may have applied statistical tests to decide the reliability of your results. If so, give the same prominence to the tests that didn’t reach statistical significance as those that did, not least to counter the historical bias in the literature.

You may also have listed specific research objectives in the Introduction. If so, identify those that were realized and explain any that weren’t. That knowledge could encourage others to build on your work.

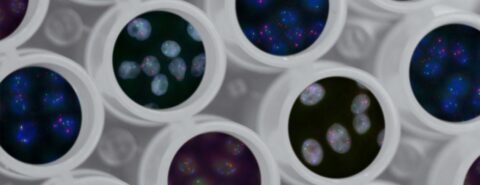

Relevance to the literatureAlong with any comparisons you’ve already made between your results and those of other researchers, it’s useful to stand back and relate your findings to the field as a whole. Here’s an example from a cell biology article published in 2012:

Regional clusters of mutations in cancer have occasionally been observed in experimental models, although not at the mutation density observed here (Wang et al., 2007). … Furthermore, they are closely associated with regions of rearrangement and occur on the same chromosome and chromosomal strand over long genomic distances, suggesting that they occur simultaneously or … over a short time span (Chen et al., 2011).

By making connections of this kind, you recognize the priority of other studies, albeit sometimes with caveats, but also show how your own work advances those studies in a coherent way.

LimitationsHaving pointed to the strengths of your work, you should also note its limitations and possible failings. Make it clear when the reader can safely apply your findings—and when they can’t. Being open about their applicability increases the authority of your work and its potential impact.

When deciding what limitations to mention, concentrate less on the obvious ones, the finite sample size, say, which the reader already knows from the Methods, and more on the subtle ones, for example factors you couldn’t control for some alternative explanation.

In practice, it may not be enough to state the limitations for the reader to appreciate their consequences. Here’s an example from a computer-science article, edited to reduce its identifiability:

We specified default values for the tools based on pretesting. It is possible that different values for these tools could affect the results.

It would help to know, for example, how representative the default values are and what happens when other values are used instead. In this way, your findings might be applied in areas you hadn’t considered.

Concluding statementThe closing paragraph of the Discussion—or a separate short Conclusion—should complement the opening of the Introduction. Keep it short, simple, and relevant. You could mention the new understanding that’s been achieved or the discovery of longer-term implications or new research directions.

There’s no need, however, to share your own research plans. They’re important to you but not necessarily to other researchers, who might misinterpret them as signalling your claim to the research area.

Finally, if you can, end with a brief take-home message, something to remember your findings by. But not “More research is needed”—which may have the opposite effect.

Photo by Unseen Studio on Unsplash

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 9, 2025

We are mythmaking creatures

Many of us feel disconnected, from ourselves, from others, from nature. We feel fragmented. But where are we to find a cure to our fragmentation? And how can we satisfy our longing for wholeness? The German and British romantics had a surprising answer: through mythology.

The romantics believed that in modern times we’ve forgotten something essential about ourselves. We’ve forgotten that we are mythmaking creatures, that the weaving of stories and the creation of symbols lies deep in our nature.

Today, we view myths as vestiges of a bygone era; products of a time when humanity lived in a state of childlike ignorance, lacking science and technology and the powers of rational reflection. William Blake (1757–1827) rejected this bias against mythology, as did Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), Friedrich von Hardenberg (1772–1801), and John Keats (1795–1821), among others. They claimed that the worldview we now inhabit is a mythology of its own.

Our challenge, the romantics argued, is not to liberate humanity from myths but to create new myths—new symbols and stories—that serve to awaken the human mind to its hidden potential. We are all mythmakers. We all use our powers of imagination to sustain the worldview we inhabit. Our task is to become aware of those powers, and with that awareness rewrite the narratives that have kept us trapped in feelings of separation from ourselves and the world at large.

The modern experience is one of alienation, incompleteness, and aloneness. We’ve fallen prey to the illusion that everything is divided. The new mythologies that the romantics set out to create turn on symbols and stories of a greater unity that connects all things. The romantics held that our path to wholeness lies in reawakening the imagination and experiencing the world poetically. They believed that myths can allow us to see ourselves as members of a larger family—a “world family”—that includes all living beings on Earth.

But how, you might ask, is this even possible? How can mythology serve a liberating function? Are myths not false and deceptive? And shouldn’t we try to escape myths entirely?

All good questions, and ones the romantics heard loudly in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Here are four ways the romantics worked to address them:

1. Reinterpretation. Ancient myths are complex, even confusing, and their meaning is always open to interpretation and reworking.Shelley’s play Prometheus Unbound is not a simple retelling of a classic myth. He reinvests the story with new meaning by positioning Prometheus as a symbol of humanity who struggles against Jupiter, a symbol of inhumanity. The old myth then acquires fresh significance; it becomes applicable to our modern yearning for community and connection with nature.

2. Reconciliation. The human mind abounds in dualities that can intensify feelings of separation; myths allow us to extend our minds beyond these dualities, thereby instilling feelings of unity.Blake writes about how the mind creates contraries, such as “reason” and “feeling,” “man” and “woman,” “heaven” and “hell.” His literary and visual work afford us the opportunity to see that these oppositions are not absolute; they are two sides of a whole. A new poetic mythology can allow us to intuit this; it can open the “doors of perception” in ways that allow us to see the unity of the spiritual and the sensual.

3. Reflexivity. When we become aware of our mythmaking powers, we can fashion symbols and stories that position ourselves as the authors or artists of our lives.In Heinrich von Ofterdingen by Hardenberg (known by his pen name Novalis), the protagonist discovers a book that reflects images from his own life. He has the uncanny realization that the book he is reading is a kind of mirror into his soul. The novel thereby displays a process of acquiring self-understanding through symbols, stories, images, and allegories—in short, through all the elements of mythology.

4. Participation. Because the romantics wanted to make us aware of our creative powers, the stories and symbols they fashion serve to invite us into the very process of mythmaking.Schlegel’s novel Lucinde is a story about a young man who discovers his artistic potential by falling in love. The novel is itself an invitation for readers to turn inward and discover their own ability to make their lives into a work of art. The novel is meant to be a stimulus for self-inquiry for the reader, who is called upon to see herself through the lens of mythology.

What then makes any given mythology “new” is that it isn’t trying to mask its origin in the human imagination. All the mythologies of romanticism share this feature in common. They are ongoing works in progress, as alive today as they were over two centuries ago. The mythologies of romanticism are like paintings left deliberately unfinished by a painter, with the hope that we will feel inspired to pick up the brush and contribute our own complex patterns of color.

Featured image by The Cleveland Museum of Art via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 7, 2025

Fact and fiction behind American Primeval

Fact and fiction behind American Primeval

A popular new Netflix series, American Primeval, is stirring up national interest in a long-forgotten but explosive episode in America’s past. Though the series is highly fictionalized, it is loosely based on events covered in my recent, nonfiction publication, Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath, co-written with Richard E. Turley Jr.

From 1857–58, Mormon settlers of Utah Territory waged a war of resistance against the federal government after the newly elected US president sent troops to occupy the Salt Lake Valley. Concerned about the Mormons’ expanding theocracy in the West—Brigham Young was not only the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints but also Utah’s governor—President James Buchanan’s advisors urged him to replace Young with a new governor, accompanied by an army contingent. The occupation of Utah by federal troops, the advisors insisted, was necessary to ensure that Mormons accepted their federally appointed leader.

Though tensions ran extremely hot, remarkably, no pitched battles broke out between the two sides in what became known as the Utah War. But the conflict was anything but bloodless. In the heat of the hysteria, Mormon militiamen in southwest Utah committed a war atrocity, slaughtering a California-bound wagon train of more than a hundred men, women, and children.

Mountain Meadows Massacre Site Mass Grave Monument near St. George, Utah

Mountain Meadows Massacre Site Mass Grave Monument near St. George, UtahTQSmith, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

Viewers have been asking what is fact and what is fiction in American Primeval’s depiction of the Utah War. Vengeance Is Mine answers those questions. Below are just a few of the answers:

Did the Mormons actually purchase and burn down Fort Bridger?Yes, though their motivations for doing both were different than those portrayed in the series. They purchased Fort Bridger in 1855—two years before any of the events depicted in the series took place. They bought it to be a trailside way station to supply thousands of immigrant converts making their way to Utah. Mormon militiamen burned down the fort in October 1857, along with the army’s supply wagons and grasses their draft animals needed to survive, all to thwart the advance of the approaching US troops and stall them on the plains of what is now Wyoming.

Did Mormon militiamen really wipe out a contingent of the US Army and a band of Shoshone people?No. The militiamen’s scorched-earth tactics successfully slowed the troops’ approach until winter snows set in, making trails into the Salt Lake Valley impassable and forcing the troops to spend a miserable winter in a tent city they created outside the burned-out remains of Fort Bridger. When Congress met in early 1858, it rejected President Buchanan’s proposal to raise additional troops to send to Utah and forced Buchanan to broker a peace settlement with Mormon leaders instead. A few years later, in 1863, a different US Army contingent stationed in Utah slaughtered a band of more than four hundred Shoshone people in the Bear River Massacre, in what is southern Idaho today.

Did the Mountain Meadows Massacre take place just outside of Fort Bridger, and did the Shoshone and Southern Paiute live nearby?No. The Mountain Meadows is in the desert climate of southwestern Utah, several hundred miles south of Fort Bridger. In the series, a band of Shoshone murder a group of Paiute men who had supposedly participated in the massacre in order to kidnap and rape white women. None of this was true. The traditional homelands of the Northwestern Shoshone are in what is today northern Utah and southern Idaho, and the Southern Paiute live in today’s southwestern Utah and Nevada, hundreds of miles apart. The Shoshone and Paiute weren’t at war and rarely, if ever, came in contact with each other. The Southern Paiute did not kidnap and rape women. The massacre was orchestrated by a group of 50-60 Mormon militiamen to cover up their involvement in a cattle raid of the wagon company that went awry. In the war hysteria of 1857, they thought that violence—murdering all the witnesses besides 17 young children—was the answer to protect themselves and their community.

Map of the Mountain Meadows region. Map created by Sheryl Dickert Smith and Tom Child for Mountain Meadows Massacre, OUP (2008) pg. 130.

Map of the Mountain Meadows region. Map created by Sheryl Dickert Smith and Tom Child for Mountain Meadows Massacre, OUP (2008) pg. 130.Tragically, the political wrangling and tensions over federal and local rule, separation of church and state, and religious zeal and bigotry, led to a deadly climax on 11 September 1857. Modern readers may recognize similar tensions today, not only in the West but throughout the United States.

Featured image by Олег Мороз on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers