Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1051

June 15, 2012

5 questions about Quantum Theory

In trying to understand the atom, physicists built quantum mechanics, the most successful theory in science. And then the trouble started. Experimental quantum facts and the quantum theory explaining them are undisputed. Interpreting what it all means, however, is heatedly controversial.

(1) How important to physics (and science) is quantum mechanics?

Quantum mechanics underlies all of physics, and therefore everything based on physics. That’s, arguably, everything. One-third of our economy depends on devices developed with quantum mechanics.

(2) Physics is about the physical world, not the mental. Right?

Wrong! That was once thought to be true. But quantum mechanics shows the physical and the mental mysteriously connected. That connection is increasingly explored today.

(3) What are Einstein’s “spooky actions”?

Einstein shocked the founders of quantum mechanics by pointing out that quantum theory said that what happened at one place could instantaneously affect what happened far away without any physical force being involved. He called this a “spooky action,” and thought it was impossible. It has now been demonstrated to exist. It is a basis of quantum computers.

(4) Is the quantum mystery controversial?

The New York Times reported a heated across-the-auditorium debate at a physics conference. One participant argued that because of its weirdness, quantum theory had a problem. Another vigorously denied that, accusing the first of “missing the point.” A third broke in saying we must wait and see. A fourth summarized the argument by saying, “The world is not as real as we think.” Three of these physicists have Nobel Prizes, and the fourth is a likely candidate for one.

(5) Can a non-physicist understand the problem?

Yes! Physics encounters the conscious observer in the simplest quantum experiment. The next-to-last sentence in Quantum Enigma is: “Non-experts can therefore come to their own conclusions.”

Bruce Rosenblum is currently Professor of Physics, emeritus, at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He has also consulted extensively for government and industry on technical and policy issues. His research has moved from molecular physics to condensed matter physics, and, after a foray into biophysics, has focused on fundamental issues in quantum mechanics. He is co-author of Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness, Second Edition with Fred Kuttner, a Lecturer in the Department of Physics at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

An Interview with Fredrick C. Harris

Dr. Fredrick C. Harris is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center on African-American Politics and Society (CAAPS) at Columbia University. He is the author of several books, including his latest, The Price of the Ticket: Barack Obama and the Rise and Decline of Black Politics. In it, he argues that the election of Obama exacted a heavy cost on black politics. In short, Harris argues that Obama became the first African American President by denying that he was the candidate of African Americans, thereby downplaying many of the social justice issues that have traditionally been a part of black political movements. In this interview, Harris discusses his findings with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: You write that President Obama’s campaign and subsequent victory helped to sap the civil rights movement of its militancy, and that social justice issues traditionally associated with black politics have been marginalized. This is the “price of the ticket.” Was it ever possible for a traditional civil rights leader to win the White House? Or was it inevitable that the first black President would be a so-called “post-racial” politician from Generation X or beyond?

Fredrick C. Harris: No, it was never possible for a traditional civil rights leader to win the White House, nor was it possible for any race-conscious black politician to build a broad coalition of voters to support their candidacies. Though Jesse Jackson’s run for the Democratic Party nomination in 1988 came closer than any other black person before Barack Obama’s rise as a presidential candidate. But the idea of a black president and the importance of black voters pushing an agenda that would include both universal policies and policies specific to black communities are two separate — though not necessarily exclusive — political goals. For instance, both Shirley Chisholm’s run for the Democratic nomination in 1972 and Jesse Jackson’s run in 1984 were efforts to place issues that were important to black voters on the electoral agenda. As a means to bring the concerns of black communities to the attention of the Democratic Party, both the Chisholm and Jackson campaigns altered the party so as to not take black voters for granted.

What we see with the election of Barack Obama as the nation’s first black president is the tension between the politics of symbolism and a substantive-focused, agenda-specific politics that includes both policies “that benefit everyone” as well as targeted public policies that focus on uprooting the persistence of racial inequality. These divisions in policy approaches to racial inequality and in the belief in the utility of race-neutral campaigning and governing have, I believe, less to do with generational differences in black Americas but more to do with ideological fissures in black politics about the best way for blacks as a group to attend to the ongoing problem of racial inequality.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: You make clear the relationship between Barack Obama’s rise to power as a “race-neutral” candidate, and the rise of what is known as the Prosperity Gospel among black voters. (By Prosperity Gospel, we are referring to the theology of financial and physical empowerment through spiritual exercise and self-reliance; this is a distinct departure from traditional black liberation theology, which places greater emphasis on attacking racist power structures.) Can you expand on the connection between the two? And is this a trend that you expect to grow stronger over the next generation?

Fredrick C. Harris: The concept of deracialized political campaigns, which emerged during the 1980s and 1990s when black politicians were trying to break the glass-ceiling by running for high-profile offices in majority white jurisdiction, supports a color-blind approach to politics. By downplaying race in campaigns — especially by avoiding discussions of race-specific policy issues — race-neutral black politicians become symbols showing that Americans have gotten beyond race. These symbols of black progress reinforce the widespread, false belief that few barriers prevent African-Americans from succeeding in American society.

Perhaps in subtle ways, adherence to the prosperity gospel provides a theological justification for the kind of color-blind black politics that is promoted by race-neutral black candidates. In many ways, the prosperity gospel is a color-blind theology. Unlike the long-standing social gospel tradition — that focuses on the duty of Christians to uplift individuals as well communities — and black liberation theology — a theology that emerged during the Black Power era and focused on the idea that a black God commands his followers to attend to the needs of the oppressed—the prosperity gospel is centered strictly on transforming individuals, not transforming communities. Only negative beliefs and thoughts about one’s station in life — not social barriers — prevent believers from receiving God’s material blessings. This implicit color-blind take on theology mends well with a politics that sees race having little or no effect on the ability of black people — particularly poor and working-class black people—to progress. Thus the growing popularity of a theology among black Americans where race does not matter and the acceptance of a style of politics that communicates the message that race does not matter as well, is, I would argue, weakening — if not the death — of a tradition of politics that confronts racial inequality head-on.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: You write, “The ‘slack’ that black voters gave Obama…meant that black voters put aside policy demands for the prize of electing one of their own to the White House.” Can you discuss a particular opportunity that Obama missed (or rejected) that would have specifically helped to alleviate the issue of black inequality?

Fredrick C. Harris: There are several, but at least one particular opportunity comes to mind during the 2008 campaign—specifically the Jena Six controversy. As you recall six black male teenagers were charged with attempted murder for fighting in a schoolyard brawl in Jena, Louisiana in 2007. What is curious about this moment is that Obama did rise to the occasion by giving an address on race and criminal justice reform during Howard University’s Convocation on September 28, 2007. The candidate seems to have been pressured to talk about the accident — as were all the major Democratic candidates for president — and outlined policies he would support to ameliorate racial disparities in the criminal justice system. One initiative Obama promised was to support a federal-level racial profiling act. That promise has yet to come to fruition, and Obama has not publically discussed the need for such an act since he’s been president. Two incidents — in theory — provided an opportunity for activists to press the president on racial justice reform, and for the president to follow through on his promise — your arrest in the summer of 2009 by Sergeant Crowley of the Cambridge, Massachusetts police force, which galvanized national attention, and the murder of Trayvon Martin earlier this year, which has again raised questions about the deadly consequences of racial profiling. Though the president expressed sympathy for the victims in both cases, Obama has yet to follow through on his campaign promise on reforming the criminal justice system.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: If, as you suggest, Obama’s presidency is in many ways a victory of the status quo (despite its appearance as a new era in racial politics), then why has the reaction to him among conservatives been so hyperbolic and hysterical, from questioning his citizenship and religion to accusing him of being a socialist?

Fredrick C. Harris: Yes, race still matters for black public officials in high-profile positions. One would expect no less for the nation’s first black president. But the attacks on Obama are also equally partisan in nature. Because Americans have such short memories about elections and presidential administrations, those who complain of Obama’s treatment by the Right forget that Bill Clinton was accused as a sitting president to be a rapist, a murderer, and a cheat. Clinton was dogged by the federal prosecutor Ken Starr and impeached by the Newt Gingrich-led House of Representatives. Indeed, Clinton’s treatment in office by the Right led Toni Morrison to declare that Clinton was the nation’s first black president. Since Republicans are so effective as an opposition party and so ineffective in governing, their nasty opposition to Obama (as well as former House speaker Nancy Pelosi) is merely a continuation of the “politics of destruction” during the Clinton years.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: Do you foresee a similar “Price of the Ticket” for other marginalized groups (women, GLBT, religious minorities) if and when they have a representative in the White House? Or is this problem you describe unique to the African American experience?

Fredrick C. Harris: That is an interesting question. Often one of the burdens of stigmatized minorities is to proclaim and to demonstrate to those in power that their stigmatized identities will not make a difference in how they view those in power as well as the levers of power. Such proclamations are required for entrance and acceptance into mainstream life. In 2009, there were echoes of the openly gay candidate for candidate for mayor of Houston — Annise Parker — deemphasizing her commitment to gay and lesbian issues and downplaying her long-time activism for gay and lesbian rights. She wanted Houston voters to know that she should be judged by her experience in maintaining the fiscal heath of Houston, as she had demonstrated as the city’s comptroller, not for her sexuality or he past commitments to gay and lesbian rights. When asked whether she would support a referendum to support same-sex benefits for city employees, which was rejected by voters in 2007, Parker responded that she did not have plans to endorse such a referendum. Parker won the election, becoming the first openly gay mayor of a major American city and, as a consequence, a symbol of gay pride. But she also has been of late — particularly since her re-election to the mayor’s seat this year — a strong voice in support of marriage equality. She also urged president Obama to evolve faster on that issue before Obama endorsed marriage equality. It is too early to see if GLBT public officials in the future will follow Parker’s “sexuality-neutral” campaign style she employed in her first election. However, Parker may have done a wink-and nod. She has become a strong voice of advocacy for the GLBT community’s causes, endorsing marriage equality and condemning right-wing homophobic elements in Houston. It will be interesting to see if Obama — like Parker has on GLBT issues — will become more vocal on racial equality issues if he is elected to a second term.

This interview originally appeared on the Oxford African American Studies Center.

Dr. Fredrick C. Harris is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center on African-American Politics and Society (CAAPS) at Columbia University. He is the author of most recently The Price of the Ticket: Barack Obama and the Rise and Decline of Black Politics. He is also the author of Something Within: Religion in African-American Political Activism, which was awarded the V.O. Key Prize for the best book on southern politics by the Southern Political Science Association, the Distinguished Book Award by the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, and the Best Book Award by the National Conference of Black Political Scientists. Dr. Harris is also the co-author (with R. Drew Smith) of Black Churches and Local Politics, and (with Valeria Sinclair-Chapman and Brian McKenzie) Countervailing Forces in African-American Civic Activism, 1973-1994, which won the 2006 W.E.B. DuBois Book Award from the National Conference of Black Political Scientists and the 2007 Ralph Bunche Award for best book in ethnic and racial pluralism from the American Political Science Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

In this ‘information age’, is privacy dead?

Privacy: A Very Short Introduction

By Raymond Wacks

Are celebrities entitled to privacy? Or do they forfeit their right? Is privacy possible online? Does the law adequately protect private lives? Should the media be more strictly controlled? What of your sensitive medical or financial data? Are they safe and secure? Has the Internet changed everything?

Newspapers are no longer the principal purveyors of news and information, and hence the publication of private facts has expanded exponentially. Blogs, Facebook, Twitter, and a myriad other outlets are available to all.

The pervasive mobile telephone fuels new privacy concerns: witness the current British hacking hullabaloo. The weapon is new, but the injury is the same. It is not, of course, technology itself that is the villain, but the mischief to which it is put. Nor has our appetite for gossip diminished. A sensationalist media continues to degrade the notion of a private domain to which individuals legitimately lay claim. Celebrity is frequently regarded as a licence to intrude.

Hardly a day passes without reports of yet another onslaught on our privacy. Most conspicuously, of course, is the fragility of personal information online. But other threats generated by the digital world abound: innovations in biometrics, CCTV surveillance, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) systems, smart identity cards, and the manifold anti-terrorist measures all pose threats to this fundamental value – even in democratic societies.

At the same time, however, the disturbing explosion of private data through the escalation of the numerous online contrivances of our Information Age renders simple generalities about the significance of privacy problematic. Is privacy dead?

The manner in which information is collected, stored, exchanged, and used has changed forever – and with it, the character of the threats to individual privacy. The electronic revolution touches almost every part of our lives. But is the price of the advances in technology too high? Do we remain a free society when we surrender our right to be unobserved - even when the ends are beneficial?

Although the law is a crucial instrument in the protection of privacy (and it is locked in a struggle to keep apace with the relentless advances in technology), the subject has many other dimensions: social, cultural, political, psychological, and philosophical. The concept of privacy is not easy to nail down, despite the attempts of many scholars and judges.

The courts have boldly sought to offer refuge from an increasingly intrusive media. Recent years have witnessed a deluge of civil suits by celebrities seeking to salvage what remains of their privacy. An extensive body of case law has appeared in many common law jurisdictions over the last decade. And it shows no sign of abating. For example the supermodel Naomi Campbell succeeded in the House of Lords in her claim against the Daily Mirror that published an article revealing her drug addiction, details of her treatment, and photographs of her outside a meeting of Narcotics Anonymous.

In Britain, the current Leveson Inquiry into the culture, practice, and ethics of the press, sparked by the alleged hacking of telephones by the News of the World, is likely to reveal a significantly greater degree of media intrusion than is now evident. It may well propose legislative protection to buttress – or even replace – those judicial remedies fashioned by the courts.

A comprehensive privacy statute may well be the most effective solution. Carefully drafted legislation, such as exists in four Canadian provinces, would provide a remedy for intrusion and gratuitous publicity. Key elements of any such legislation should include an objective standard of liability, as well as several defences (including consent, public interest, and privilege).

Freedom of speech is, of course, no less important, and any statute will inevitably ensure that it receives explicit recognition. The two rights are often thought to be in conflict, but they are frequently complementary. How, for example, can you exercise your right to free speech when your telephone is hacked or your email messages intercepted?

Privacy is accorded superior safeguards in Europe than in the United States which has still to acknowledge the inadequacy of its reliance on the Supreme Court to protect privacy against an escalating digital onslaught. Much of its common law privacy protection is based on the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution which protects the right of the people “to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.” It would be more effective if the government were to ratify the Council of Europe Privacy Convention. This would mark a significant step towards safeguarding this rapidly eroding right. The United States lags far behind the more than fifty countries with comprehensive data protection legislation. It surely cannot continue to seek eighteenth century remedies to twenty-first century challenges.

In the case of film stars, models, pop stars, and other public figures, it seems that our – frequently lurid – interest in their private lives spawns a thirst for intimate facts which many tabloids are more than willing to satisfy.

Raymond Wacks is Emeritus Professor of Law and Legal Theory. He has published widely on the subject of privacy for almost four decades, most recently Privacy: A Very Short Introduction. In 2013, Oxford University Press will publish his Privacy and Media Freedom.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 14, 2012

Verulamium, the Garden City!

In my last blog post, I looked at my research into the inter-war archaeologist Tessa Verney Wheeler (1898–1936) and the biography it led to. Today I’d like to present something she might have penned herself. Tessa and Rik Wheeler were both preoccupied with making the British past accessible, interesting, and even familiar on a local level. They used children’s activities, lectures, concerts, contests, newspaper articles, and even fiction on occasion to accomplish that.

This pastiche of an ad for a ‘new housing development’ at Verulamium (St Albans) around 275 AD when the great city gates were built plays on that idea. It reflects the view of Roman Britain the Wheelers wanted to present in the early 1930s: a modern-minded province, whose people (like the Londoners of the interwar period) commuted from outer towns into the greater metropolis. It also takes inspiration from the endless new housing development advertisements common in England today, particularly the new condos built along the old canal networks in modern bedroom communities like Oxford and Brentford.

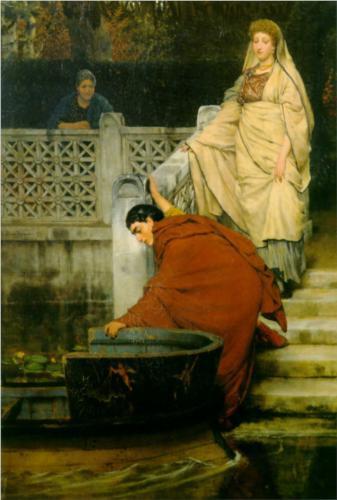

The illustrations (by Victorian artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who also wanted to depict the universality of some human experiences across time) show a nicer lifestyle than the Wheelers really imagined the inhabitants of Verulamium enjoying. The proximity to London is also a bit exaggerated, but that’s what the fine print at the end is for!

Verulam Garden Development Ltd is proud to present its latest offering:

Verulamium, the Garden City!

Londinium — wonderful, vibrant, and wealthy — has never held a better place economically in the Empire. But that growth has come at a price. It’s never been easy maintaining a comfortable household in the metropolis, perfect as it is for trade and business. What’s a paterfamilias to do, if he wants to ensure his family lives in the comfort they require as Romans, while still maintaining his links to Londinium networks?

Londinium — wonderful, vibrant, and wealthy — has never held a better place economically in the Empire. But that growth has come at a price. It’s never been easy maintaining a comfortable household in the metropolis, perfect as it is for trade and business. What’s a paterfamilias to do, if he wants to ensure his family lives in the comfort they require as Romans, while still maintaining his links to Londinium networks?

Now, there’s an easy answer. Verulamium has always been known as a pleasant provincial capital, well-built and attractively founded on the banks of the sparkling Ver.

Today, it’s something more. With the growth of exciting new living developments and the increasing ease of road and river trade, more and more households are settling permanently in Verulamium. Pater travels swiftly to Londinium for work when necessary, keeping an eye on those investments and trading opportunities only the Smoky City can offer. But we’re more concerned with his family. What of Mater, Julius, and little Soror?

At home, Mater rules a house equipped with every modern convenience for master and slave. Modern kitchens — freshly stocked with the latest designs in cooking braziers, under-floor tiled heating that rivals the best in Gaul, and well-proportioned triclinia — are a given. Add a wide choice of fresco and mosaic decoration, and it’s clear that Verulamium can provide the ideal domestic setting for those official dinners and parties that mean so much to a husband’s military or civilian career.

When not entertaining, Mater and Soror may be found enjoying the town’s wonderful bathing and worship facilities, taking in a show at the excellent local theatre, or perhaps browsing the charming shops of local craftsmen. The town’s

enameled jewelry is justly famous and residents enjoy a special discount that will enable every lady to become the envy of her friends. For more practical concerns or a change in service, why not visit the slave market or take in provisions drawn freshly from every corner of the Island at the daily food stalls? You may not see the sea at Verulamium, but you’re still able to dine on the freshest oysters Neptune can provide thanks to the town’s convenient river.

As for young Julius, he’s enjoying the most elite education in the town’s academies, well-built institutions boasting the most erudite Greek masters and the most pleasant playing fields. He’ll be ready to join Pater in a few years on those weekly trips into Londinium, where they’ll camp out uncomfortably in City lodgings and think enviously of Mater and Soror back home. Don’t worry, lads, thanks to the excellent Imperial road system that trip back is nothing to a good chariot! You can almost travel it daily, but who’d want to leave Verulamium more than they have to?

Disclaimers: All depictions of facilities are artists’ renderings and may not resemble final structures as completed in some or any respects. Road condition and commuting time not guaranteed. Residential jewelry discount not guaranteed. Frescos, mosaics, and kitchen equipment provided subject to a further financial payment over and above freehold cost. While the city of Verulamium has been subject to no major tribal attacks in recent memory, and is fully protected by the latest urban military technology, no financial or moral liability is assumed by Verulam Garden Development Ltd in the event of the settlement’s full or partial destruction by rebellion and/or any other aggressors including, but not limited to, Imperial conflict, fire, storm, plague, flood, local gods, harpies, Picts, Northern longships, and/or wrath proceeding from an undetermined or specific divine figure or figures.

Lydia Carr was born in New York City in 1980, and took her D.Phil at Oxford in 2008. She is the author of Tessa Verney Wheeler: Women and Archaeology Before World War Two. She is currently Assistant Editor at the Chicago History Museum and in her spare time, she writes light, bright mystery novels set in the 1920s.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Facebook is no picnic

Lately, loneliness has been attributed to our digital technologies, but its real, root cause is our mobile individualism. America’s mobility rates have declined over the last few decades, but we still move more than most other industrialized peoples. This longstanding pattern in American life means that our social networks are often disrupted, leaving us uprooted and alone. While Americans have long struggled to connect with each other, the contemporary generation faces particular challenges.

First, we have learned since childhood that we aren’t supposed to be too attached to particular places or people. We should be cosmopolitan citizens of the world, able to leave one place for another with no heartache. Consequently, when we feel isolated and lonely, we are loathe to discuss it for fear of appearing maladjusted and immature. That may make us feel even more alone, for our silence on the subject prevents us from realizing how pervasive — and normal — the emotion is. Another result of our collective silence is that we lack the social resources, institutions, and traditions that earlier generations (less tight-lipped about loneliness, used to cope with the emotion).

Today when we’re lonely, we often rely on screens: iPads, phones, or TVs. They comfort us, and simultaneously keep our loneliness hidden from those around us. Online, we connect with distant friends equally hungry for connection and have reunions of sort with people from across the country and across the years of our lives. We sit alone in our living rooms or offices, but feel some sort of link to those far from us. Or perhaps we turn to the TV screen, which offers what Robert Kubey and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi have termed “parasocial experiences.” TV offers comfort to the lonely because its “programs are well stocked with familiar faces and voices and viewing can help people maintain the illusion of being with others even when they are alone.”

Today when we’re lonely, we often rely on screens: iPads, phones, or TVs. They comfort us, and simultaneously keep our loneliness hidden from those around us. Online, we connect with distant friends equally hungry for connection and have reunions of sort with people from across the country and across the years of our lives. We sit alone in our living rooms or offices, but feel some sort of link to those far from us. Or perhaps we turn to the TV screen, which offers what Robert Kubey and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi have termed “parasocial experiences.” TV offers comfort to the lonely because its “programs are well stocked with familiar faces and voices and viewing can help people maintain the illusion of being with others even when they are alone.”

Earlier generations were more likely to turn to each other. In some ways, they had an easier time of maintaining connections than modern Americans do because they often moved en masse. Before the automobile and the airplane, wagon trails and railroad lines funneled traffic to particular locations. Families that knew each other in New England often migrated west together, settling near each other in new towns. African Americans leaving the South for the North in the early twentieth century did the same, traveling on trains from Hattiesburg, Mississippi to Chicago, for instance — and maintaining neighborly bonds in the process. Today, however, internal migrants are more likely to scatter when they move, following less predictable paths, ending up in new places with few old neighbors nearby. This makes it difficult to re-establish home ties.

Contemporary Americans also lack the organizational impulse of earlier generations who worked diligently to recreate social networks they had left behind. To fight off feelings of loneliness, Americans in the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century joined organizations, held picnics, dinners, parades, often with people from their hometowns or states. So, for instance, in the 1840s and 1850s, the Sons of Maine organized themselves in Boston, the Sons of New England gathered in Philadelphia and Sacramento, and the Sons of New York held annual festivals in Wisconsin and in Keokuk, Iowa. Although not terribly far from home, New Hampshire migrants to Boston held a “Festival of the Sons of New Hampshire,” over which native son Daniel Webster presided. The group, numbering over 1500, assembled 7 November 1849, marched through the streets of Boston, and then held a banquet in a hall above the Fitchburg train station. The evening concluded with the vow that the event would be repeated. In 1853, 2,000 “Sons of New Hampshire” marched through the streets of Boston and 1,700 dined at a banquet that followed.

Immigrants did much the same, creating thousands of organizations across the country. A Lithuanian language newspaper reported on one in 1905, “A branch of the Lovers of Fatherland Society was organized on Sunday, January 15, on the North Side of Chicago. The first meeting was held with songs and declamations…. Miss Aldona Narmunciute recited the poem, ‘I am a Lithuanian Child’ and sang ‘I am Reared in Lithuania.’ Miss Antigona Aukstakalniute recited the poems: ‘Wake up Brother Ancestor’ and ‘As Long as You are Young, Loving Brother, Sow the Seed’; she also sang two songs ‘Hello Brother Singers’ and the ‘Love of Lithuania.’

So great was the desire for connection that these gatherings could grow to enormous sizes. In the late nineteenth century, transplanted Easterners and Midwesterners in southern California eagerly formed state associations. Iowan C.H. Parsons, a driving force behind them claimed they “liquidated the blues.” Parsons was inspired to organize these groups because he “so frequently heard the expression, ‘If I could only run into some one I know,’ in the streets of Los Angeles.” The state associations met just such a need, holding social events where lonely men and women could meet others from their home states and sometimes even their hometowns. The Iowa association did this most successfully, holding Iowa picnics, which grew from 2,000 to 3,000 Hawkeyes in a park in 1900, to a gathering of 30,000 picnickers in 1917, to 45,000 in 1926, and to more than 100,000 in 1935. These picnics testified both to the vastness of the metropolis the migrants were joining, and the widely felt need for connection.

Today, hometown associations flourish among immigrants, who gather together for parties, dinners, holidays. But native-born Americans have largely abandoned such gatherings. We have become so accustomed to mobility and cosmopolitanism that many of us believe we shouldn’t be overly tied to home, to place, and are convinced our identities no longer derive from a state or a town. And yet, in reality, our identities are still profoundly local — on our Facebook pages are links to hometowns. There childhood friends mingle, and high school classes reassemble if only virtually. In our efforts to suppress our loneliness in public, we often appear as though we don’t care about the places and people we’ve left behind, but every day, when we go online in the privacy of our homes, we show that the opposite is true.

Susan J. Matt is Presidential Distinguished Professor of History at Weber State University, in Ogden, Utah. She is the author of Homesickness: An American History. Read her previous posts “Home for the holidays” and “How loneliness became taboo” on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Norway gives women partial suffrage

14 June 1907

Norway gives women partial suffrage

On 14 June 1907, Norway’s Storting (Stortinget) demonstrated the difficulty faced by women’s suffrage advocates around the world. On the one hand, the national legislature approved a bill that would allow some of Norway’s women to vote for lawmakers and even to win seats in the Storting. On the other hand, the male lawmakers limited national voting rights to women who had the right to vote in municipal elections.

First woman to cast her vote in the municipal election, Akershus slott, Norway, 1910. Oslo Museum collection (via DigitaltMuseum) under Creative Commons License.

Those limits meant that only women who were at least 25 years old and met certain tax-paying thresholds had the right to vote. The Storting voted by a 3-to-2 margin not to enact universal female suffrage.

From the 1300s to the 1800s, Norway was joined with its neighbors Denmark or Sweden. While reforms in the late 1800s created a powerful Norwegian legislature and considerable autonomy over domestic conditions, Norway did not gain full independence until 1905. Even then, the legislature accepted a king and put a constitutional monarchy into place.

Democratic reformers were among of the forces pushing for these changes in the late 1800s. Norwegian men gained the right to vote in 1898. A women’s suffrage movement had been active since 1885 but was unable to convince the Storting to extend the right to women. Norway’s women did enjoy some advances. In 1854, they gained the right to inherit property, and in the 1890s, they won the right to control their own property.

Nevertheless, it was another six years after the 1907 vote for the Storting to agree to full women’s suffrage. While the delay may have frustrated Norway’s women, they were still better off than the women in all but three other countries. Only New Zealand, Australia, and Finland allowed women to vote at that time.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

How not to infringe Olympic intellectual property rights

Since 2005, when London won the Host City contract for this year’s Olympics, there has been an intensity of interest in how the London Organising Committee (LOCOG) would go about the protection of the Olympic image and in the detail of the UK Government’s legislative attempts to exclude those who would attempt to take advantage of that image, without paying for the privilege.

The eventual economic climate in this Olympic year could not be more different to that prevailing when London edged past Paris to cross the winning line, that July day in Singapore. Yet even then, when in retrospect one perceives that funding was relatively easy to come by, the IOC and the London bidders did not lose sight of the interests of the existing Olympic partners or the creation of an attractive investment opportunity for potential sponsors. Part of London’s successful bid package was a draft of the strict legislative and regulatory regime proposed to protect the London Games from ambush marketing and thus protect these interests.

London2012 mascot Wenlock and Mandeville, courtesy of London 2012

The Olympic Games have enjoyed protection for some time, both in the UK and worldwide, via the Olympics association right (OAR): protecting against the associative use of Olympic words, mottos and symbols — so-called “controlled representations”. The OAR became part of the UK’s IP lexicon via the Olympic Symbol Protection Act 1995. Awkward and well publicised examples of ambush marketing at past Olympics highlighted the limitations of traditional intellectual property rights, such as trade marks or copyright, prompting the creation of the OAR, but even this new right was not always enough to prevent non-sponsors piggy-backing on the Olympic feel-good factor. Marketing and advertising executives are a creative bunch. Given one set of restrictions, they happily invent their way around them, as Nike’s approach to ambush marketing at the 1996 Atlanta Games illustrated (circumventing the restrictions through branded give-aways to spectators and the purchase of a building next to the Olympic village, which was then converted into a blatantly branded Nike centre).

Often contextual references to the Olympics can create associations as easily as the use of specific words or symbols. This is where the current temporary local Olympic right, the London Olympics association right (LOAR), steps in, providing for infringement by the creation of an association in any form. This extends protection, in an attempt to plug any gap in restrictions which non-sponsors may identify. The LOAR’s breadth and lack of specificity is an attempt to surmount the unpredictable nature of ambush marketing and cover every eventuality.

In its early drafts, the London Olympics Bill came down heavily on the side of the Olympic rights holders, proposing that the use of expressions such as “London 2012″ or “summer games” should be infringements of the LOAR. However, following a general outcry over the unworkability and apparent unfairness of such a stance, these phrases became, in the eventual London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Act 2006, merely indicative of infringement, to be taken into account by the courts when considering whether an association has been created with the London Games. Such a relaxation of the Olympic grip may have dismayed sponsors but it was necessary to maintain a more widespread goodwill in relation to the Games. The English press pack can quickly turn sour when it gets its teeth into restrictions it perceives as unwarranted or unfair to British business.

Despite this, the rights of association in place this summer to protect the London Olympics are some of the most generously drafted intellectual property rights available. Imagine a trade mark right which does not require confusion to be infringed (even with similar marks) combined with a passing off right for which you do not need to show goodwill (this is assumed) or damage and a generous interpretation of “misrepresentation” (that the infringer is connected to you in any sort of contractual or commercial fashion or may just be giving the impression they have provided you with some financial support) and you have got association rights. Context is all; combinations of images could trigger infringement of the LOAR even without the word Olympic featuring anywhere.

Olympic Torch Relay, courtesy of London 2012

Context does not just apply to the advertisement itself; an associative context can be achieved for an otherwise non-associative advertisement, by its proximity to the Games venues. Thus, the most recent restrictions to be issued cover advertising and trading within the “event zones” around the Olympic venues (or along them in the case of the marathon) and preclude advertising and trading within these areas immediately before and during events without LOCOG’s consent. Even as the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games (Advertising and Trading) Regulations 2011 (Regulations) were about to be published, new concerns were obviously arising, since one of the last amendments added ‘animals’ to the list of prohibited advertising vectors.

The courts can order erasure, seizure, destruction and make orders for damages in relation to infringement of the association rights. Those liable (which includes personal liability of anyone managing or responsible for a property on which there is a breach of the Regulations, or the director or manager of an entity that is in breach) could face an unlimited fine as well as the costs of police and ODA officials in enforcing the Regulations, with the latter’s powers of immediate seizure and entry to private land.

The Olympics appears to be seen internationally as a special case, an untouchable organisation where protection should not be questioned. Only in March this year, for example, the Generic Names Supporting Organisation Council classed the Olympics with the Red Cross in recommending that names relating to both organisations were accorded protected status and banned from the first round of gTLD applications, although not without a certain amount of dissent from within the GNSO. Certainly, without protection, sponsors would withdraw and the “greatest show on earth” would become unaffordable. Whether the vision of the world coming together to compete peacefully on the sporting stage, uplifting though it may be, is as significant to the well-being of humanity as the Red Cross’s contribution has been over the years, is a debatable question. Let’s hope the protection granted to the London Olympics is justified come July 27th. The Queen made do with much less legislative protection for her Diamond Jubilee, but that’s another editorial…

Rachel Montagnon is a Professional Support Consultant in the intellectual property group of international law firm Herbert Smith. Having completed degrees in both pre-clinical medicine and law, Rachel trained at Herbert Smith and qualified into the firm’s intellectual property group. Rachel is a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, where this article first appeared.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

June 13, 2012

Criticizing the OED

The literature on the history of the Oxford English Dictionary is extensive, but I am not sure that there is a book-length study of the reception of this great dictionary. When in 1884 the OED’s first fascicle reached the public, it was met with near universal admiration. I am aware of only two critics who went on record with their opinion that the venture was doomed to failure because it would take forever to complete, because all the words can not and should not be included in a dictionary, and because the slips at Murray’s disposal must contain numerous misspellings and mistakes. But supporters outnumbered denigrators (whose point, though grievously unfocused, was well taken) by a hundred to one. A similar thing happened when, also in 1884, Friedrich Kluge published the first edition of his German etymological dictionary. Two eminent philologists hastened to explain why the dictionary was no good. Their harsh voices were drowned in a chorus of enthusiastic reviewers.

However, some criticism of the OED was constructive, even if not always friendly or fair. Right after the appearance of the first installment, Notes and Queries began publishing letters with additions and antedatings. Once Murray responded in irritation (which, judging by his correspondence, happened to be his prevailing mood) that it would have been more profitable if lists of rare words had been sent to his office in advance (while they could still be made use of or rejected) rather than as an exhibit of the critic’s erudition and assiduity.

With regard to antedatings, an open season on earlier citations was declared at once and still continues, sometimes with negligible results (two or three years), sometimes with important consequences for a word’s history and etymology. Although Murray had well-informed readers and an excellent coordinator in the United States, discussion in The Nation invariably pointed to inaccuracies and mistakes in matters concerning American usage. For all these reasons and for many more, the revision of the OED, which is now underway, has great value. At Oxford, all the critical remarks, even the less substantive ones, must have been collected, studied, and taken into account. A book treating them would still be interesting to read.

Etymologies in the first edition of the OED were superb, mainly because Murray and Bradley happened to be great philologists. Every student of word origins begins by consulting their suggestions. Disagreement can be taken for granted, though it is remarkable how well those etymologies have withstood all attacks. Even when the hypotheses offered in the dictionary can be called into question, better ones have not been too numerous. But since credit should be given where credit is due, we need not ignore reasonable conjectures. I want to recount two episodes in the etymological criticism of the OED. The articles appeared in The Nation in 1910 and 1914 respectively. I ran into them last month, so that neither citation is in my bibliography.

ALFALFA (by Francis Philip Nash): “The etymology of alfalfa, the name of a well-known variety of lucern (Medicaga sativa) is, I believe, wrongly given in our dictionaries. The Century Dictionary states that it comes to us from the Spanish, and further says that ‘it is said to be from the Arabic alfaçfaç the best kind of fodder.’ This assumes that the first syllable is the Arabic article al, which begins so many Arabic words adopted into European languages. The Century Dictionary does not give its authority; but I find the same derivation in Roque-Barcia’s great Spanish encyclopædic dictionary, whence I presume Murray’s Dictionary also took it. Murray says ‘identified by Pedro de Alcalá with Arabic alfaçfaç, the best sort of fodder.” Nash goes on to say that this etymology is wrong from every point of view, especially because the older form of the plant name is alfalfez, which he explains as alf-al-Fez “the fodder of, or from, Fez.” “The Spaniards, or the Moors, doubtless introduced this kind of fodder from Morocco (Fez) and hence the designation.”

It is not for me to evaluate an Arabic etymology, and I am always wary of statements containing the word doubtless, but it seems that Nash made a good point, as those who will read the whole of his article will probably agree. English dictionaries contain words borrowed from multiple languages. Even the most versatile experts can have no firsthand knowledge of them. Thousands of fugitive notes like the one I have quoted above are extremely hard to hunt down. Tons of useful information lie buried in popular periodicals and may never be recovered. Perhaps this post will help lexicographers to deal with alfalfa.

A Bare-tailed Woolly Opossum (Caluromys philander), an opossum from South America, 2007. Photo by Ramon Campos. Creative Commons License.

PHILANDER. If philander makes you think only of love making, you are behind the times. Leo Wiener, a distinguished scholar, wrote an article in which he dealt with philander “a little animal in southeastern Asia and in Australia.” His piece is a furious attack on what he calls philological fallacies. Although his wrath is vented not only on the linguists ignorant of animal lore, we will stay with the philander. The Century Dictionary is mocked for deriving the word from Greek, “without entering into the reason for the philanthropic attitude of this bandicoot.”

Next comes the OED. “The Oxford Dictionary, quoting Morris, ‘Austral. Eng.,’ is more specific, for it says: ‘From the name of Philander de Bruyn, who saw in 1711 in the garden of the Dutch Governor of Batavia the species named after him being the first member known to Europeana.’ This circumstantial description suffers from two slight errors. In the first place, the discoverer of the animal was named Cornelius, not Philander, de Bruyn, and secondly, this Cornelius de Bruyn distinctly says that the Malay name of the animal was pelandoh.” Obviously, slight (slight errors) was used ironically, for everything in the etymological part of the OED’s entry appeared to be wrong.

Wiener should perhaps have restrained his ire, but his conclusion is, unfortunately, correct. He mentions two “fundamental errors,” of which the second is more important than the first. It is “that blind veneration of authority to which philologists are addicted more than any other class of mortals. The Oxford Dictionary quotes Morris; Morris, in all probability, had an authority before him and all the future dictionaries will quote the Oxford Dictionary, all unaware of the fact that they are only compounding a spiritual felony.” Plagiarism has been the principal method of lexicography since the beginning of time: dictionary makers keep copying from one another. This is no less true of etymology than of any other area of modern lexicography. With such splendid sources as Skeat, the OED, and The Century Dictionary, there seems to be no need for further research, let alone for checking their sources. Even repeating their mistakes looks like a worthy occupation. Frist, few people will detect the “fallacy.” Second, erring with the greatest authorities is almost an honor (isn’t it?). The result is indeed “compounding spiritual felony.” On the other hand, if one begins to explore the history of everything from alfalfa to philander, the dictionary will never be completed. You are damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How New York Beat Crime

For the past two decades New Yorkers have been the beneficiaries of the largest and longest sustained drop in street crime ever experienced by a big city in the developed world. In less than a generation, rates of several common crimes that inspire public fear — homicide, robbery and burglary — dropped by more than 80 percent. By 2009 the homicide rate was lower than it had been in 1961. The risk of being robbed was less than one sixth of its 1990 level, and the risk of car theft had declined to one sixteenth.

Twenty years ago most criminologists and sociologists would have doubted that a metropolis could reduce this kind of crime by so much. Although the scale of New York Citys success is now well known and documented, most people may not realize that the city’s experience showed many of modern America’s dominant assumptions concerning crime to be flat wrong, including that lowering crime requires first tackling poverty, unemployment and drug use and that it requires throwing many people in jail or moving minorities out of city centers. Instead New York made giant strides toward solving its crime problem without major changes in its racial and ethnic profile; it did so without lowering poverty and unemployment more than other cities; and it did so without either winning its war on drugs or participating in the mass incarceration that has taken place throughout the rest of the nation.

To be sure, the city would be even better off, not to mention safer, if it could solve its deeper social problems—improve its schools, reduce income inequalities and enhance living conditions in the worst neighborhoods. But a hopeful message from New York’s experience is that most crimes are largely a result of circumstances that can be changed without making expensive structural and social changes. People are not doomed to commit crimes, and communities are not hardwired by their ethnic, genetic or socioeconomic character to be at risk. Moreover, the systematic changes that the city has made in its effort to reduce crime are not extremely expensive and can be adapted to conditions in other metropolises.

A TRUE DECLINE

The first nine years of New York City’s crime decline were part of a much broader national trend, an overall drop of nearly 40 percent that started in the early 1990s and ended in 2000. It was the longest and largest nationwide crime drop in modern history. What sets New York apart from this general pattern is that its decline was twice as large as the national trend and lasted twice as long.

That extraordinary difference — between drops of 40 and 80 percent — can be seen in comparing homicide rates from 1990 and 2009 in the five largest cities in the US: New York, Houston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The great crime decline of the 1990s reduced homicide in all five cities, in four of those by a substantial amount. But New York went from being dead center in its homicide rates in 1990 to being the lowest of the five — more than 30 percent below the next best city and only 40 percent of the mean rate for the other four places.

Of course, official crime statistics are generated and verified by the same police departments that get credit when crime rates fall and blame when they increase. And indeed, allegations of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) fudging data to make the numbers look pretty have received much media attention. But anecdotal evidence of police misconduct arises frequently in other places as well, including many American cities where the official numbers are not as rosy. Still, how can we be confident that the spectacularly good news reflects the reality of street crime?

The best method to verify trends is with independent data. Fortunately, agencies apart from the police have kept track of two key crime indices, and their findings have corroborated the NYPD’s data. First, county health departments keep meticulous records of all deaths and provide specific reports of what the police classify as murder and ‘nonnegligent” manslaughter. Over the 9 years when the police reported the dramatic decline in most crimes, the agreement between the health and police reports each year was practically perfect. In the second case, auto theft (which went down by a spectacular 94 percent), insurance companies record claims by victims. I obtained reports of theft and loss by year from two separate industry data bureaus. The most complete statistics of insurance claims indicated a decline in theft rates of slightly more than 90 percent.

I also found independent evidence for the big drop in robbery. Whereas simple robberies are reported at the police precinct level, killings from robberies are reported independently by a citywide police office, which also provides data to the FBI—and they are harder to conceal. The rate of killings from robberies fell more than 84 percent in all robberies. Victim surveys also have confirmed the dip in both robberies and burglaries (which are break-ins, usually in which the crime victims are not around, whereas robberies involve a direct encounter with the victim) in the city.

By American standards, then, New York City has become a safe, low-crime urban environment. How did this happen?

GOTHAM CRIME MYTHS

The part of New York’s crime drop that paralleled the larger national downturn of the 1990s did not seem to have any distinctive local causes. The decline was not easy to tie to specific causes either at the national level or in the city, but the same mix of increased incarceration, higher prosperity, aging population and mysterious cyclical influences probably was responsible in both cases.

What caused the roughly half of New York City’s decline that was distinctively a local phenomenon may be easier to single out, as we will see. The answers, however, are not what many people would expect.

For example, very few drastic changes occurred in the ethnic makeup of the population, the economy, schools or housing in the city during the 20 years after 1990. The percentage of the population in the most arrest-prone age bracket, between 15 and 29, declined at essentially the same rate as it did nationally, and economic growth did not reduce either poverty or unemployment in New York significantly below the national average.

A common assumption is that the U.S.’s inner cities became safer because they were “cleaned up,” or gentrified — which is when formerly blighted neighborhoods begin to attract people of higher income, and lower-income populations are progressively pushed out by increases in rents and property taxes. During gentrification, so goes the thinking, all the poor people leave, driving down crime rates. And indeed, in Manhattan, the city’s wealthiest borough, crime rates dropped along with ethnic and economic diversity. But in the other three most populous boroughs (Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx), diversity did not drop; if anything, it increased. And yet crime went way down — and at comparable rates — in all four of those boroughs.

The momentous drop in street crime — especially certain kinds — is surprising in another respect. New York has been the illicit-drug-use capital of North America for at least seven decades. By all accounts, it continues to be. In the 1980s the widespread introduction of crack cocaine was associated with sharp increases in homicide. The perceived close link between drugs and violence was one of the animating theories for the War on Drugs that was declared in the decade after 1985. From the perspective of the late 1980s, a significant reduction in violence without massive reductions in the sale and use of illegal drugs would have been an impossible dream. But that is exactly what seems to have happened in New York.

Drug-related killings (such as dealers shooting one another) dropped 90 percent from peak rates. Meanwhile drug use appears to have stayed relatively stable in the city, whether the indicator is overdose deaths, hospital discharges for drug treatment, or urine tests of criminal suspects. New York seems to be winning the war on crime without winning the war on drugs.

Finally, and perhaps most remarkably, the city’s successful crime policies bucked the national trend toward locking up more and more people. The policy tactics that have dominated crime control in the U.S. assume that high-risk youth will become criminal offenders no matter what we do and that criminals will continue to commit crimes unless they are put away. In the mid-1990s proponents of the “supply side” theory of crime were warning that cities such as New York with high numbers of minority youth growing up in single-parent families would require massive new investments in prisons and juvenue facilities. Since 1972 these supply-side theories were the central justification of the sevenfold expansion of imprisonment in the U.S. In the 1980s New York participated in the trend. But in the 1990s, while the U.S. prison and jail population expanded by half, New York went its own way. In the first seven years of the decade its incarceration rate rose only 5 percent, and then it began to fall. By 2008 it was 28 percent below the 1990 rate; nationally, incarceration was up 65 percent.

So where have all the criminals gone?

Many of them just seem to have given up on breaking the law. The rate at which former prisoners from New York were reconvicted because of a felony three years after release — which had increased during the late 1980s — dropped by 64 percent over the years after 1990. The NYPD still catches criminals, and prosecutors and judges still send them to jail. But the city has reduced its most serious crimes by 80 percent without any net increase in prison populations. These numbers disprove the central tenets of supply-side crime control.

ESTIMATING POLICE EFFECTS

The one aspect of crime policy wherein the municipal government enacted big changes — and the only obvious candidate to take credit for the city’s crime decline — was policing. Beginning in 1990, the city added more than 7,000 new uniformed cops and made its police efforts much more aggressive and focused on high-crime settings.

The presence of more police on the street was originally thought to have caused most of the New York decline in the 1990s. But because at that time crime was abating everywhere in the nation, it is hard to know how much of New York’s success stemmed from its own policing changes as opposed to the same mysterious set of causes that operated nationally. Moreover, after 2000 the NYPD actually cut its force by more than 4,000 uniformed officers, and yet reported crime kept dropping and doing so faster than in other large cities.

Nevertheless, a close look at the data after 2000 does point to the importance of policing. In spite of the loss of 4,000 officers, the most recent period still has substantially more police on the street compared with 1990. And the number of police relative to the amount of crime kept growing because crime slowed faster than police rolls shrunk. It is also possible that the cumulative effects of increased manpower lasted into the decade when force levels went down. And the impact of cops is reflected in the fact that New York City experienced the largest drops in the crimes that happen on the street or require access from the street — burglary, robbery and auto theft — and thus are especially deterred by increased police presence.

The police department did not only add more cops on the streets, it also implemented a number of new strategies. It is difficult to determine how much credit, if any, each of the policing changes should get, but some clear indications have appeared.

Once again, the simple explanations are not of much help. Some of the authorities’ more prominent campaigns were, in fact, little more than slogans, including “zero tolerance” and the “broken windows” strategy — the theory that measures such as fixing windows, cleaning up graffiti and cracking down on petty crimes prevents a neighborhood from entering into a spiral of dilapidation and decay and ultimately results in fewer serious crimes. For instance, the NYPD did not increase arrests for prostitution and was not consistent over time in its enforcement of gambling or other vice crimes.

But other campaigns seem to have had a significant effect on crime. Had the city followed through on its broken-windows policing, it would have concentrated precious resources in marginal neighborhoods rather than in those with the highest crime. In fact, the police did the opposite: they emphasized ‘hotspots’ a strategy that had been proved effective in other cities and that almost certainly made a substantial contribution in New York. Starting in 1994, the city also adopted a management and data-mapping system called CompStat. At a central office in downtown Manhattan, analysts compile data on serious crimes, including their exact locations, and map them to identify significant concentrations of crime. Patrols then deploy in full force on-site — whether it is a sidewalk, a bar or any other public place — sometimes for weeks at a time, systematically stopping and frisking anyone who looks suspicious and staring down everyone else. Although one might expect that criminals would just move to another street and resume their business as usual, that is not what happened in New York. Thus, crimes prevented one day at a particular location do not ineluctably have to be cornmitted somewhere else the day after.

The biggest and most costly change in police tactics is the aggressive program of street stops and misdemeanor arrests that the police use in almost every patrol operation. In 2009 New York’s finest made more than half a million stops and nearly a quarter of a million misdemeanor arrests. The police believe these tactics help to prevent crime. Aggressive patrol, however, has a history almost as long as that of street policing itself and its effectiveness has not always been clear. Although it could in principle be more effective in New York than in other places, the evidence that it adds distinctive value to the hotspots and CompStat strategies is not strong.

LESSONS LEARNED

To establish conclusively what works and what does not will require scientific field tests measuring the effectiveness of additional manpower and of other techniques from the NYPD’s full kitchen sink of tactics. Then there should be trial-and-error adaptations to other urban settings. But even this early in the game, several lessons from New York City should have a significant influence on crime policy elsewhere.

First of all, cops matter. For at least a generation, the conventional wisdom in American criminal justice doubted the ability of urban police to make a significant or sustained dent in urban crime. The details on cost-effectiveness and best tactics have yet to be established, but investments in policing apparently carry at least as much promise as investments in other branches of crime control in the U.S.

Two other important lessons are that reducing crime does not require reducing the use of drugs or sending massive numbers of people to jail. Incidentally, the difference between New York’s incarceration trends and those of the rest of the nation—and the money that the city and state governments avoided pouring into the correctional business—has more than paid for the city’s expanded police force.

Unfortunately, New York’s successes in crime control have come at a cost, and that cost was spread unevenly over the city’s neighborhoods and ethnic populations. Police aggressiveness is a very regressive tax: the street stops, bullying and pretext-based arrests fall disproportionately on young men of color in their own neighborhoods, as well as in other parts of the city where they may venture. But the benefits of reduced crime also disproportionately favor the poor—ironically, the same largely dark-skinned young males who suffer most from police aggression now have lower death rates from violence and lower rates of going to prison than in other cities. We do not yet know whether or how much these benefits depend on extra police aggression.

If New York continues on the same path, it may be able to achieve even greater reductions in crime. After all, even after its vast improvements, its homicide rate is still much higher than those of most major European cities and six times higher than Tokyo’s. At some point, though, it is possible that rates could reach a hard bottom, beyond which further progress could require solving the deeper social problems, such as economic inequality, racial segregation, or lack of access to quality education.

Perhaps the most optimistic lesson to take from New York’s experience is that high rates of homicides and muggings are not hardwired into a city’s populations, cultures and institutions. The steady, significant and cumulatively overwhelming crime decline in New York is proof that cities as we know them need not be incubators of robbery, rape and mayhem. Moreover, it demonstrates that the environment in which people are raised does not doom them to a lifetime outside the law—and that neither do their genes. That result is a fundamental surprise to many students of the American city and is the most hopeful insight of criminological science in a century.

This article appears courtesy of Scientific American.

Franklin E. Zimring is the William G. Simon Professor of Law and chair of the Criminal Justice Research Program at the University of California, Berkeley. Since 2005, he has been the first Wolfen Distinguished Scholar at Boalt Hall School of Law. Professor Zimring’s recent books include The City that Became Safe: New York’s Lessons for Urban Crime and Its Control; The Great American Crime Decline (with David T. Johnson); and The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Boris Yeltsin elected Russia’s first President

13 June 1991

Boris Yeltsin elected Russia’s first President

On 13 June 1991, millions of Russians went to the polls for the first time in an open election to choose a president. Emerging as winner was 60-year-old Boris Yeltsin, a maverick with a reputation for alcohol abuse who had for some time advocated political and economic reforms.

Boris Yeltsin. Photo by Susan Biddle. Source: White House Photo Office.

In the 1980s, Yeltsin became acquainted with Mikhail Gorbachev, both on the rise in the Communist Party. In 1985, after Gorbachev became leader of the Soviet Union, he named Yeltsin to the top party post in Moscow and to the Politburo that ruled the nation. Within two years though, Yeltsin made himself unwelcome by pushing for more rapid reforms and criticizing Gorbachev’s leadership. He lost his leadership positions.Nevertheless, by 1989 he was back in prominence after winning election to a seat in the Congress of People’s Deputies, the national legislature. The following year, the legislature of the Russian Federation voted him as Russia’s president. Recognizing that the Communist leadership had little regard for him — and perhaps sensing the weakening hold of communism on national power — Yeltsin bolted from the party.

Just two months after his popular election as president in 1991, Yeltsin faced his first and most crucial challenge. In August, Communist hardliners attempted a coup aimed at ousting Gorbachev, and ending his and Yeltsin’s competing reform efforts. Yeltsin rallied the Russian people and encouraged Soviet troops to oppose the coup. In the face of Yeltsin’s and popular defiance, and the loss of military support that coup leaders had counted on, the takeover attempt failed.

Yeltsin’s rule as Russia’s president was tumultuous. He survived a coup attempt against him in 1993 and won a second election in 1996. Political fights marked his rule with a legislature unwilling to fully embrace his economic reforms, his tendency to rule by edict to bypass that legislature, and a bloody and costly war to defeat an independence movement in the province of Chechnya. In 1999, Yeltsin resigned and named Vladimir Putin as acting president.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers