Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1047

June 27, 2012

National HIV Testing Day: Take the Test, Take Control

Today is National HIV Testing Day in the US, where nearly 1.2 million people are living with HIV and almost 1 in 5 don’t know they’re infected. Here Martin S. Hirsch, MD, FIDSA, editor-in-chief of The Journal of Infectious Diseases, discusses the importance of HIV testing. Dr. Hirsch is also professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, professor of infectious diseases and immunology at the Harvard School of Public Health, and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital.

What role does HIV testing play in both the US and global response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Why is early diagnosis so important with this disease?

HIV testing is essential for effective control of the pandemic, both within the US and worldwide. Many persons who carry HIV are unaware of their infection and these individuals are a major source of virus transmission to others. Moreover, it is now clear that early antiretroviral drug therapy of infected individuals decreases long term morbidity and mortality. Since treatment is now recommended for nearly all HIV-infected individuals in the US, the earlier one knows he or she is infected, the better.

What recent research advances or findings have there been regarding HIV testing? What should we take away from these findings?

Diagnostic tests for HIV infection continue to improve, particularly with respect to being able to detect early infections, a time when the amount of virus in a person’s blood and secretions is high and the risk of transmission to others is greatest. Investigators have been able to reduce the “window period” where diagnostic tests cannot accurately detect virus from several weeks to 10-15 days, as a result of advances in diagnostic technology. Laboratories across the country are now implementing third and fourth generation tests to make reliable diagnoses early in the course of infection.

What do you see as the major barriers to implementing routine HIV testing in the US?

The major barriers to implementing routine HIV testing in the US are variations in health care infrastructures among our states, inadequate funding for such approaches, and the lack of knowledge regarding the benefits of routine HIV testing. It has been estimated that annual routine HIV testing worldwide, combined with antiretroviral treatment of those found to be infected, could reduce new HIV infections by over 90% within 10 years. However, inadequate health infrastructures and insufficient funding make this possibility unlikely.

What impact will greater access to HIV testing, such as the rapid at-home test now under regulatory review in the US for possible sale over the counter, have on HIV prevention and treatment efforts?

Over the counter, rapid, at-home tests will allow persons to test for HIV infection in the privacy of their homes. The sensitivity and specificity of some of these tests have improved considerably over the years. Although positive results on such at-home tests will still need confirmation by other tests at accredited laboratories, their increasing use will allow individuals to take their own first steps in determining whether or not they need medical attention.

To raise awareness of National HIV Testing Day, the Editors of the Journal of Infectious Diseases and the Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases have highlighted recent, topical articles, which are freely available for the next two weeks. Both journals are publications of the HIV Medicine Association and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

National HIV Testing Day and the history of HIV testing

National HIV Testing Day brings the past alive into the present. It was not until 2 March 1985 that the FDA approved the first antibody-screening test for use in donated blood and plasma. The test came three years after Luc Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute in Paris identified the suspect virus in 1983. Later that year Anthony Gallo at the National Cancer Institute in Washington cultivated the virus for further investigation and human testing. HIV testing arose in a culture of fear. The history of the test’s accuracy and efficiency is a story of dread.

No doubt about it, testing is crucial to protect and treat HIV. There is no free lunch. These benefits come at a great price. As a 77-year-old gay man who lived through the early crisis, I recall the shock surrounding early testing. A positive finding then came as a death sentence. Before death, there was the prolonged trial of dying, dying of a disease that added shame to affliction. Anxiety darkened every aspect of gay life. Anxiety is future-oriented. Young gay men, fit and talented, saw life through the lens of annihilation. We lived, as Paul Monette’s 1998 memoir expressed it, on Borrowed Time. A drop of blood in a tube could bring news of premature end. With their lives still before them, young men could no longer imagine a future. One measureless modern catastrophe was wiping out all youth and accolades, and almost the era itself.

Stigma and criminalization accompanied a positive result. It was illegal not to tell a partner that one was HIV positive. One wouldn’t be hired or, if employed, could lose the job. Predatory insurance companies hovered to profit from people with AIDS by buying out their life insurance at a small percentage of its value. Testing was private, but how anonymous was anonymous testing? How confidential was confidential testing? Heartache deepened the culture of fear into suspicion of people and science.

Many questioned (not unwisely) the test’s accuracy. The test went through stages to check for a false positive. There was the Western blot assay that added time to the final results. The test felt like a trap. Some men were so emotionally paralyzed that they believed they were HIV-negative. One false positive could send a person into terminal self-doubt. A false positive caused one friend to retake the test to ease anxiety so many times that his physician refused to do it for several months. Moreover, one had to wait up to six weeks for verified results. Waiting was part of the torment. As a result, there was a run on the New York Blood Center from gay men saying that they wanted to donate blood because they knew that the Blood Center got very quick results. Some sexually active gay men refused to take the test because there was neither treatment nor cure. AZT, the first line of treatment, wasn’t available until 1987.

Little by little, people came through. At the Gay and Lesbian Center on West 13 Street in New York, a nurse named Denise was there to help those too scared, too closeted, to trust official services. She had a legal way to get results, and get them quickly. The test was given on “the-need-to-know basis.” Denise’s professional concern was like a pebble dropped in water that rippled out with compassion. When she gave results, she wasn’t shy about receiving kisses from those who received the news, good or bad. This woman wasn’t afraid of tenderness. She told me how men broke down over getting a negative result. Yes and survival were hard to take. Also, she saw the courage of those who knew the bad news was coming. Denise was at hand. So was relentless anxiety, which to this day gnaws at my memory with the bite of a pit bull that won’t let go.

HIV testing now is routine, trustworthy, and rapid. They now test for genetic material through nucleic acid, but those scientific details are beside the point. Scientific numbers are impressive but soulless. Knowledge counts. There are take-home kits for the shy. A mouth swab will do it. Denise is now everywhere. The news is out. Free packages of condoms are all over the place bring with them a message from, say, from the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center on Allen Street. “HIV Testing Needle Exchange & Drop-In.” Stop by. The visit may lessen the fear, may reduce the anxiety. And better treatments are readily available.

Richard Giannone, emeritus professor at Fordham University, is the author of Hidden: Reflections on Gay Life, AIDS, and Spiritual Desire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the  and the Fordham University Press website.

and the Fordham University Press website.

AIDS and HIV in Africa

On HIV Testing Day, Gregory Barz and Judah M. Cohen, the American ethnomusicologists who edited The Culture of AIDS in Africa, reflect on the ways they came to their field research.

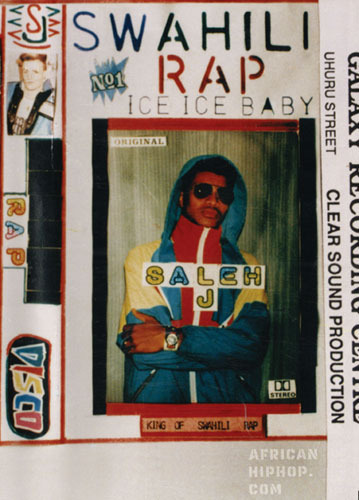

Saleh J’s 'Ice Ice Baby' Source: africanhiphop.com.

“Growing up as a musician in the arts community in and around New York City in the 70s and 80s, I had every opportunity to invest my scholarly energies in my own community, in my own world. In fact, I still have difficulty responding to students and colleagues when asked why my research on AIDS has always been ‘over there’ in Africa rather than ‘here’ at home. Wasn’t I, after all, part of the ‘AIDS generation’? The fact that I have lived, taught, and conducted research ‘over there’ in a variety of African locations for over 20 years, however, does not necessarily mean that I was initially more open to focusing on the scourge from a global perspective. I can still remember not paying attention (purposefully so?) to the earliest rap lyrics in East Africa about silimu (‘Slim,’ i.e., HIV, the ‘slimming’ disease), such as Saleh J’s 1991 cover of ‘Ice Ice Baby’ that dealt specifically with AIDS. For me, HIV/AIDS was not yet an ‘academic’ topic. At the time, AIDS for me was still a very personal and emotional topic.“In the late 90s I circumnavigated East Africa’s Lake Victoria to document drumming patterns in an effort to help prove historical migratory patterns in the area. Encountering a variety of women’s indemnity groups in Uganda who used music, dance, and drama to educate their peers about HIV/AIDS taught me not only to re-learn how to listen to music, but perhaps more importantly how to open my heart to possibilities that the West had much to learn from the response to HIV by African communities. Producing the first monograph on music and HIV/AIDS in Africa forced me to rethink academic boundaries as well as my own personal objectives.

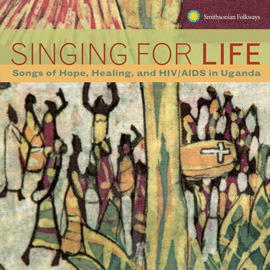

Singing for Life: Songs of Hope, Healing, and HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Source: Smithsonian Folkways.

“The world of AIDS scholarship, however, carries with it a certain degree of responsibility. Many scholars of disease in Africa (TB, malaria, HIV/AIDS) have one foot firmly planted in their academic studies while the other foot continuously steps into unfamiliar worlds of activism and advocacy. My own efforts to translate scholarship to a more popular medium resulted in an unexpected Grammy nomination in the ‘Best Traditional World Music’ category, confirming for me that there are much larger audiences available for our research on music and HIV/AIDS in Africa.“As an openly gay field researcher, I have experienced personal and academic challenges in regards to institutional and individual agendas held by countries and collaborators. Each encounter reinforces for me the unique power of our human identities. Who we are as individuals may not appear on the surface (and perhaps it shouldn’t) as transparent, but acknowledging such issues may underscore not only what we do, but why we do it and motivate us all to move beyond our setbacks and continue to work in the next decade of HIV/AIDS.”

– Gregory Barz, Vanderbilt University

“As with many Americans who grew up in the 1980s, I first faced HIV/AIDS before I could give the disease a name. It transfigured, and eventually took away, one of my first musical mentors. From third through fifth grade, Craig Jacobsen taught my music and violin classes at my suburban New Jersey public school. He provided a welcome contrast to my K-2 music teacher — male, young, energetic, and pedagogically innovative. Once, to teach us ‘improvisation,’ he spontaneously crumpled up pieces of paper and threw them into the air for several minutes, while we cluelessly tried to guess his motives.

“In fifth grade, he began to disappear. The substitutes for his classes mentioned only that he had fallen ill. My father, who taught in the school system, said that he had come down with a severe case of chicken pox — his second case, which defied everything I had known from my childhood experiences. It lasted for weeks, then months. Nobody knew why. One day in the winter of 1984, while running an errand for another teacher, I glanced Mr. Jacobsen hiding out in the school resource room. I went over to him, happy to see him. But he wasn’t himself: he had spots on his face and arms, and seemed deeply upset. With mixed emotions, he warned: ‘Don’t get near me. I’m contagious.’ I had not yet had chicken pox (I still haven’t) and confused I left.

“I would see him again, but rarely. Partway through middle school, his obituary appeared in the local paper. It stated (bravely for the time) that he had a male partner, but otherwise the account of his death remained characteristically ambiguous. Everything else had to be implied. He taught schoolchildren after all. My health classes had not yet added AIDS to the curriculum. It took me a while to bridge the gap in my understanding.

“I thought of Mr. Jacobsen twenty years later as I began to research HIV/AIDS and music formally. I finally made the conscious connection between my ten-year-old reality and the knowledge I had acquired since. I never saw my music teacher ‘sing his disease’ in the most literal sense. Yet the moment I faced him — scared, uncertain — stays with me. Through my work in Uganda and afterward, I learned to view that moment as desperate and also as vastly creative. I don’t know what Mr. Jacobsen did after I left, but he was a creative force to my young mind. His memory, now reconfigured, gave me a starting point for my journey into the ways people face, and express, what has since revealed itself as a global crisis.”

– Judah M. Cohen, Indiana University

Gregory Barz and Judah M. Cohen are the editors of The Culture of AIDS in Africa: Hope and Healing Through Music and the Arts. Gregory Barz is Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology, Graduate Dept. of Religion, and African American Studies at Vanderbilt University. His publications include Singing for Life: Music and HIV/AIDS in Uganda; Performing Religion: Negotiating Past and Present in Kwaya Music of Tanzania; and Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, Second Edition. Judah M. Cohen is the Lou and Sybil Mervis Professor of Jewish Culture and Assistant Professor of Jewish Studies and Folklore and Ethnomusicology at Indiana University. He is the author of Through the Sands of Time: A History of the Jewish Community of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Does Britain need Armed Forces Day?

Does Britain need Armed Forces Day? Years ago I was sleepless in Seattle having just flown in from Europe. I flicked on early morning TV and was greeted with a very American spectacle: an F-15 flying down the Grand Canyon against the ghostly backdrop of the stars and stripes and the US Army choir singing “Star-Spangled Banner”. It all seemed so, well, American and I could not for a moment imagine such on-yer-sleeve patriotism ever catching on in Britain.

On 30 June, Britain will celebrate Armed Forces Day, “…to raise public awareness of the contribution made to our country by those who serve and have served in Her Majesty’s Armed Forces…and to [give] the nation an opportunity to Show Your Support for the men and women who make up the Armed Forces community: from currently serving troops to Service families and from veterans to cadets.”

As someone who works closely with the British armed forces my allegiance is also perhaps on-my-sleeve. I have a huge respect for the Armed Forces community, the way they do their job, and the sacrifices they make, but I am not an unquestioning supporter. They could do an awful lot of things an awful lot better.

In fact Armed Forces Day is also about Britain today. When I watched that F-15 years ago, Britain had yet to face hyper-immigration, Scottish secession, loss of sovereignty to Brussels, and the profound loss of respect in national institutions and leaders consequent of all of the above. Back then, there was an unspoken belief that British society was still cohesive enough not to need the kind of ‘melting pot’ patriotism of the Americans. ‘God(s), Queen and Country’ albeit tattered was still seen as sufficient in and of itself. No longer.

Armed Forces Day and Help for Heroes thus represent a cri de coeur from a large segment of the British population who no longer believe political leaders listen to them or represent their concerns about change. The British military is perhaps the one institution of state in which people can still believe. They believe themselves to be denied patriotism by the politically-correct elite and here is one occasion when it can be expressed without the usual suspects citing xenophobia, a little Englander approach, or even racism.

However, Armed Forces Day must also be protected against such tendencies by remaining true to it is mission; to celebrate the work on behalf of all us by members of the British armed forces from all colours, creeds, and persuasions.

Britain today has its own society. There is no point in wallowing in nostalgia and Armed Forces Day must not become an excuse for that. There is still much to celebrate about Britain and I for one will be there on 30 June. Does Britain need Armed Forces Day? The answer is most definitely yes because the men and women of the armed forces have earned it.

Julian Lindley-French is Eisenhower Professor of Defence Strategy at the Netherlands Defence Academy, a member of the Strategic Advisors Group of the Atlantic Council of the United States in Washington, and a member of the Strategic Advisors Panel of the UK Chief of Defence Staff. Lindley-French is co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of War, which published this year.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 26, 2012

Democracy as concentration

Nietzche’s suggestion that “When the throne sits upon mud, mud sits upon the throne” is a powerful phrase that has much to offer the analysis of many political systems in the world today, but my sense is that it is too crude, too raw, and too blunt to help us understand the operation of modern forms of democratic governance. It is certainly not a phrase that enters my mind when I reflect upon the election and presidency of Barack Obama. American democracy is, just like American society, far from perfect. Yet to see democracy as some form of social distraction or to define elections as meaningless risks descending into nihilism.

All out for defense of democracy: Informed opinion counts. WPA Federal Art Project, 1935-1943. Source: Library of Congress.

Democracy generally succeeds in turning ‘fear societies’ into ‘free societies’. It provides a way of allowing our increasingly complex, fragmented and demanding societies to co-exist through compromise and co-operation rather than violence and intimidation (still the default approach to political rule in large parts of the world). To make such an argument is not to deny the existence of social challenges, or to suggest that all politicians are angels or that democratic politics in toto is perfect. It is to take inspiration from Bernard Crick’s In Defence of Politics (published exactly fifty years ago) and accept that democratic politics is inevitably messy, slow, and cumbersome due to the manner in which it works around squeezing simple decisions out of complex and frequently incompatible demands (Weber’s ‘slow boring through hard wood’). My message to all those ‘disaffected democrats’ who seem content to peddle ‘the politics of pessimism’ is simple. Democratic politics cannot ‘make all sad hearts glad’ (to use Crick’s words) but it remains a ‘quite beautiful and civilizing activity’.Democracy is therefore not a distraction because it ensures that public pressure actually matters. Elections matter because they allow arguments to be made and pressures to be vented. Elections inevitably produce ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ but at least the losers live to fight another day. If there is, however, a problem within American democracy it rests on the fact that some sections of society have arguably become what I call ‘democratically decadent’. Decadent in the sense that they seem to have forgotten that membership of any democratic society involves both rights and responsibilities; it involves listening and talking; giving and taking. No political system or politician can satisfy a world of ever greater public expectations. I am personally quite glad that Obama turned out not to be Superman as too many people look to politicians to solve their problems as if there were simple solutions to complex problems.

Let us not delude ourselves about the limits of politics or the role of politicians. Let us not engage in a form of self-denial by ignoring the fact that the United States has somehow managed to lose its capacity to engage in mature and balanced political debates. ‘Attack, attack, attack’ may have become the motto of American politics as seen in the political adverts and the toxic gutter-press sniping of shock-jocks, but we should not confuse democracy as it has been practiced in the past with how it might be practiced in the future. Let us be candid about the fault-lines within American society: its focus on material consumption, the isolating effects of the internet, the absence of intellectual nourishment, the destructive consequences of untrammeled free markets, and the existence of social conflict. But then use the great power and value of democratic politics to address these issues and through this forge a new politics of optimism. Let us concentrate hard on this thought and not be distracted!

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Politics at the University of Sheffield. His latest book, Defending Politics: Why Democracy Matters in the 21st Century, has just been published by Oxford University Press. His book Delegated Governance and the British State was awarded the W.J.M. Mackenzie Prize in 2009 for the best book in political science. He is also the author of Democratic Drift and co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of British Politics. Read his previous blog posts: “It’s just a joke!” on political satire and “Attack ads and American presidential politics.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Democracy as distraction

In our American republic, democracy is allegedly easy to recognize. We the people seek change and progress via regular presidential elections. Every four years, proclaims our national mantra, electoral politics offer us the best form of human governance. If only we can choose the right person, we will be alright. How could it be otherwise?

Democracy .. a challenge. Illinois WPA Art Project, 1940. Source: Library of Congress.

Yet, if this reasoning were actually correct, the state of our fractured and segmented union would be considerably more enviable. The undiagnosed fallacy in America’s quaintly democratic mythology lies in a core confusion of cause and effect. Here, elections and politics represent consequences or results, not causes. In the more formal language of philosophy and science, they are epiphenomenal.Democratic institutions are always reflections of a far deeper truth. This still-hidden truth lies in the society’s accumulating inventory of private agonies and collective discontents. No institutionalized pattern of democracy can ever rise above the severely limited ambitions, insights, and capacities of its citizens. In short, it is not for elections to cast light in dark places.

Let us be candid. We the people inhabit a withering national landscape of crass consumption, incessant imitativeness, and dreary profanity. Bored by the banality of everyday life and beaten down by the struggle to avoid despair in a nation of stark polarities, Americans will grasp apprehensively for any convenient lifeline of hope.

There is more. Intellectual life is taken seriously almost nowhere. Nowadays, the life of the mind in America is a very short book. Once upon a time, Ralph Waldo Emerson had written of an American democracy based on “high thinking and plain living.” Today, virtually every young person’s aspirations have far more to do with the accumulation of visible wealth than with the acquisition of wisdom. Already in 1776, Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, had observed that any society founded upon such a debased inversion of values could be shaped only by a desperately meager measure of citizen self-esteem.

Whatever happens every four years, we the people remain unaffected by any corollary feelings of gainful private thought. Instead, obsessed with social networks, reality television, and “fitting in,” our preferred preoccupation lies in a shamelessly voyeuristic ethos of indulgence in other people’s joys and sufferings.

Ideology, when it is expressed as an incantation, can replace rational judgment. We Americans still tend to think against history. In the end, we are presently rediscovering, even the most ardently democratic societies can be transformed into plutocracies.

We are taught that there will be tantalizing opportunity for wealth and advancement in the “free-market.” Only later, however, do some finally recognize this market for its most durable and injurious underpinnings. Inevitably, these are the interpenetrating but opaque expectations of war, sex, and narcissism.

Even the most affluent Americans now inhabit the loneliest of lonely crowds. Small wonder, too, that so many millions cling desperately to their cell phones and Facebook connections. Filled with a deepening horror of having to be alone with themselves, these virtually connected millions are frantic to claim recognizable membership in the “democratic” mass.

“I belong, therefore I am.” This is not what philosopher René Descartes had in mind when, back in the 17th century, he had urged skeptical thought and cultivated doubt. This is also a very sad credo. It essentially screams the demeaning cry that social acceptance can be as important as physical survival.

Our democracy is also making a machine out of Man and Woman. In an unforgivable inversion of Genesis, it now even seems plausible that we have been created in the image of the machine. Whatever happened to more elevated origins?

As the election hoopla continues to heat up, we Americans will remain grinning but hapless captives in a deliriously noisy and suffocating crowd. Proudly disclaiming any sort of interior life, we will proceed, very conspicuously, at the lowest common denominator. After all, erudition now markedly out of fashion is obviously beside the point.

To speak up for democracy, read up on democracy. WPA Federal Art Project, 1935-1943. Source: Library of Congress.

The American democracy’s real enemy remains a pervasively unphilosophical spirit, one that insistently demands to know nothing of truth.As a professor for more than forty years, it is easy to see that our colleges are now typically bereft of anything that might hint at an inquiring spirit. What matters presently is only that an “investment” in college proves “cost-effective.” As for the once-revered Western Canon of literature, art, and philosophy, it has been supplanted by an expanding “pragmatism.” It goes without saying that there can never be any American democratic redemption in a quest for learning or even beauty.

Though faced with genuine existential threats, millions of Americans insist upon diminishing themselves daily with assorted forms of morbid excitement, supersized bad foods, shallow entertainments, and the distracting blather of presidential politics. Not a day goes by that we don’t take note of some premonitory sign of impending catastrophe. Nonetheless, our exhausted democracy, still seeking its redemption in periodic elections, continues to impose upon its fragile and manipulated people, an open devaluation of critical thought.

Soon, even if we should somehow manage to avoid a nuclear war, further economic dislocation, and mega-terrorism, the swaying of the American ship will become so violent that even the hardiest lamps will be overturned. Then, the phantoms of great ships of state, once laden with silver and gold, may no longer lie forgotten. Instead, we will finally understand that the circumstances that could send the compositions of Homer, Goethe, Milton, and Shakespeare to join the disintegrating works of long-forgotten poets were neither unique nor transient.

In ancient Greece, the philosopher Plato had already understood the obligation of politics to make the “souls” of the citizens better. In these United States, presidential elections necessarily have more tangible objectives. At the same time, our citizens continue to place too many of their transformational bets on the next presidential contest. Oddly, they neglect to consider that an elected president can never rise above the self-imposed limitations of an exhausted American electorate.

It may not matter much which candidate is successful. This is not an imprudent or gratuitous argument against democracy and elections, but rather a well-reasoned plea for more penetrating forms of American political understanding. As recognized accoutrements of democracy, elections are perfectly fine, even commendable, but they can never hope to fix or transform what is truly important. For such deeper and indispensable forms of remediation, we will finally need to split open and cast away the false reassurance that certain political institutions can rescue us.

Ultimately, we must acknowledge that a viable American democracy requires a widening and inalienable inner sovereignty. No democratic society and polity can ever really be better than the qualitative total of its individual human underpinnings. In a crudely trenchant metaphor, Nietzsche reminds us that, “When the throne sits upon mud, mud sits upon the throne.”

Louis René Beres was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971) and is the author of many books and articles dealing with international relations and international law. A Professor of Political Science at Purdue, Dr. Beres was born in Switzerland, a tiny democracy tracing its own unique electoral origins all the way back to the 13th century. He is a frequent contributor to OUPblog.

To read more on this subject, check out Individuality and Mass Democracy: Mill, Emerson, and the Burdens of Citizenship by Alex M. Zakaras which argues that we must develop an ideal of citizenship suitable for mass society, based on the ideas of John Stuart Mill and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Also see author Matthew Flinders response coming up on the blog today.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about Individuality and Mass Democracy on the

Berlin Airlift begins

26 June 1948

Berlin Airlift begins

On 26 June 1948, after three months of Communist rulers blocking the delivery of supplies to the American, British, and French zones of West Berlin, the western powers struck back with a bold response. American and British planes stepped up their process of flying supplies to West Berlin to an around the clock operation and the Berlin Airlift was on.

At the end of World War II, Berlin was divided among the three western powers and the Soviet Union. The American, British, and French zones were in a difficult position, however, as Berlin sat deep within Communist East Germany. As a result, its people depended on long train lines and highways for supplies.

Relations between the three western powers and the Soviet Union soured in March of 1948 when the Americans, British, and French agreed to unite their three zones. The Soviets were angered by the move. It began to block access to West Berlin by road. On 24 June, it went further and announced that all railroad and highway traffic would cease. It also cut off electricity to the western areas of the city.

Berliners watching a C-54 land at Berlin Tempelhof Airport, 1948. Source: United States Air Force Historical Research Agency.

The Airlift was a bold response to the Soviet blockade. American and British planes had to bring 2,000 tons of food and supplies every day. In the winter, the need to cart coal into the city increased the demand to 5,000 tons a day. The mission dubbed “Operation Vittles” by American pilots had planes landing every three minutes to keep West Berlin’s two million fed.

The western powers also put pressure on the Soviets and their East German allies by blocking exports from leaving Eastern Europe. In 12 May 1949, the Soviets finally lifted the blockade. With land transportation once again permitted, the Airlift could end, having delivered more than 2.3 million tons of supplies in nearly a year of flights.

Operation Vittles had succeeded.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Why Auto-Tune is not ruining music

Originally made famous as a special effect on Cher’s “Believe,” Auto-Tune — the program that can fix the pitch of a singer — has received a lot of bad press. A recent piece in Time magazine blamed it as the central reason “why pop is in a pretty serious lull at the moment” and listed it in its “50 Worst Inventions.” There have been demonstrations at the Grammy’s against Auto-Tune as though it was to blame for the onslaught of formulaic pop (2009, Death Cab for Cutie). Jay-Z had a hit with the anti-Auto-Tune song “D.O.A (Death of Auto-Tune),” despite its widespread use by fellow rap artists from T-Pain to Kanye West.

The same technological determinism has condemned every new music technology from the player piano to multi-track tape recorders to synthesizers and drum machines. Many thought recording itself contained the seeds of destruction for live music.

As a recording professional, I see Auto-Tune primarily is a tool that allows for the occasional pitch fixing of a small part of a vocal performance. Before Auto-Tune I had numerous debates with singers about a particular phrase that I felt was especially emotional and effective but had one slightly sharp or flat element. I’d say “But the performance is great! No one is going to notice that tiny pitch issue.” Often the singer “just can’t live with that line” so we’d record it again. (We’ve been fixing pitch in vocal performances by re-recording for a long time.) However, when we’d re-record the line, invariably it wouldn’t be quite as emotional or expressive, but it would be more in tune. The singer would be satisfied and I’d be disappointed. Now, thanks to Auto-Tune, I can pitch fix the little problem and save that great performance.

Additionally, Auto-Tune is harangued as special effect or as an obvious effect on a vocal. From the robotic vocorder effect to flanged vocals, from “telephone” vocals to vocals with a lot of repeating echoes, we’ve been creating obvious effects on vocals for a long time. Vocal effects are fun. They can be creative and expressive, or they can be overdone and clichéd, but they are hardly new.

Auto-Tune is sometimes used to fix an entire vocal performance, rendering it more accurately in tune than is natural. This may indeed make for a slightly less emotional performance, but it may also make for a slightly more engaging performance. It doesn’t rob the vocal of most of its expressive qualities: dynamics, vibrato, timbre, etc. It’s just a slight refinement and often just a matter of taste — not a wholesale destruction of musical expression.

New technologies allow for new forms of creativity. They are essential to the process of renewal, to the seeds of inspiration. Abused, used poorly, tried as shortcuts rather than creative outlets — these faults lie with user. Nevertheless, McLuhan taught us that “the medium is the message.” If Auto-Tune is inherently bad then you have to argue that recording is inherently bad. One may argue that there have been negative effects of recording — the professionalization of music performance, for example — but I’d say the scale falls heavily in favor of recording as a cultural gift, and Auto-Tune as well.

Steve Savage is an expert in the art of digital audio technology and has been the primary engineer on seven records that received Grammy nominations (including Robert Cray, John Hammond Jr., The Gospel Hummingbirds and Elvin Bishop). He also teaches musicology at San Francisco State University. Savage holds a Ph.D. in music and has two current books that frame his work as a practitioner and as a researcher. The Art of Digital Audio Recording: A Practical Guide for Home and Studio from Oxford University Press is the result of 10 years of teaching music production and 20 years of making records. Bytes & Backbeats: Repurposing Music in the Digital Age from The University of Michigan Press uses his personal recording experiences to comment on the evolution of music in the computer age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 25, 2012

10 questions for Bradford Morrow

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selection while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 26 June, Bradford Morrow leads a discussion on My Antonia by Willa Cather.

Bradford Morrow. Photo by Michael Eastman.

Where do you do your best writing?At the kitchen table of my farmhouse in upstate New York.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

I have those “a-ha!” moments all the time, especially when the writing is going well, but I don’t remember having a very first epiphany moment.

Which author do you wish had been your seventh grade English teacher?

William H. Gass.

What is your secret talent?

I’m a pretty decent birder.

What is your favorite book?

I can never properly answer this question, because the minute I settle on one book, like say Nabokov’s Lolita, I think of another I like every bit as much, such as Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or Angela Carter’s Burning Your Boats. I’m afraid I have hundreds of favorite books!

Who reads your first draft?

Cara Schlesinger has been reading my first drafts for years and I’m very grateful. Incisive, insightful, and utterly unafraid.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

No.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

I used to write longhand first drafts but my handwriting has steadily deteriorated over the years and so I prefer the computer now.

What book are you currently reading? (Old school or e-Reader?)

Well, in fact, Willa Cather’s My Antonia.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

I have to watch it with dashes —- they have a way of appearing in the middle of sentences —- because they too often can interrupt the flow of thought.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

In trouble.

Bradford Morrow is author of the novels Come Sunday, The Almanac Branch, Trinity Fields, Giovanni’s Gift, Ariel’s Crossing (all available as e-books from Open Road Media) and The Diviner’s Tale, which was published in 2011 simultaneously by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in the United States and Grove Atlantic/Corvus in England. His anthology on the subject of death, The Inevitable: Contemporary Writers Confront Death, co-edited with David Shields, came out with W. W. Norton in 2011. And his first collection of short stories, The Uninnocent, was published by Pegasus Books, also in 2011. A fantasy-apocalyptic novella, Fall of the Birds, was published as a Kindle Single by Open Road Integrated Media that same year.

Recipient of numerous awards, among them the Academy Award in Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an O. Henry Prize (for his story, “Lush”), a Pushcart Prize (for his story “Amazing Grace”), and a Guggenheim Fellowship, he also founded and edits Bard College’s acclaimed literary journal, Conjunctions, for which he received the 2007 PEN/Nora Magid Award. Along with Conjunctions, which has now produced some 58 issues, publishing the work of over a thousand fiction writers, poets, essayists, and dramatists, Morrow edits the online Web Conjunctions, publishing new work each week.

He has edited a number of books, among them The New Gothic (with Patrick McGrath); The Selected Poems of Kenneth Rexroth; World Outside the Window: Selected Essays of Kenneth Rexroth; Classics Revisited; More Classics Revisited; and The Complete Poems of Kenneth Rexroth (with Sam Hamill). Morrow has also published several volumes of poetry, including Posthumes and A Bestiary (which was illustrated by 18 contemporary artists such as Richard Tuttle, Eric Fischl, Kiki Smith, and Joel Shapiro), as well as a children’s book, Didn’t Didn’t Do It, in collaboration with the legendary cartoonist Gahan Wilson. He is currently recording The Bestiary with collaborator Alex Skolnick.

His stories and essays have been widely anthologized—including, most recently, in Best American Noir of the Century, edited by James Ellroy and Otto Penzler, which featured his story “The Hoarder”—and his work has been translated into a dozen languages. He is completing work on a seventh novel, The Prague Sonatas, which takes place both in Prague, Czech Republic and Prague, Nebraska. Morrow is professor of literature and Bard Center Fellow at Bard College. He divides his time between New York City and an old farmhouse in upstate New York.

Previously in the 10 questions series: Lynn Neary and Wuthering Heights.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about My Antonia on the

Excluded, suspended, required to withdraw

When can social experiences cause as much suffering and hurt as physical pain? The answer is when they involve rejection and social exclusion. There are endless ways, both small and large, in which people can reject and exclude you and participate in making your life miserable.

Your mother cuts you off because she didn’t like the way you said something to her and refuses to talk to you for years.

Your friend — well used to be — invites all your other friends to a party s/he’s having and doesn’t invite you.

A classmate who tells the other kids that you’re mean and not to hang out with you. S/he ignores your friend request on Facebook or unfriends you.

Maybe s/he starts a conversation with someone else in the hallway when you pass them by at work and pretends not to notice you. S/he can stay quiet when other co-workers start to distance themselves from you. Later when they really start to gang up on you, s/he does their best to rain trouble down on your head.

These examples of social exclusion are person to person or, in the case of the groups of school kids and co-workers, a group to an individual person. Institutions and organizations can also formalize social exclusion through practices like indoor and outdoor school suspensions; forced leaves of absences and requirements to withdraw from universities; and demotions, firings, and layoffs in workplaces. Invariably, for the person excluded, the experience of rejection will be hurtful. Even the smallest slights and rejections cause emotional pain, if only fleetingly so. The degree of hurt and pain caused by rejection and exclusion is probably related to the degree of importance placed by the rejected person on the individual or group doing the rejecting.

These examples of social exclusion are person to person or, in the case of the groups of school kids and co-workers, a group to an individual person. Institutions and organizations can also formalize social exclusion through practices like indoor and outdoor school suspensions; forced leaves of absences and requirements to withdraw from universities; and demotions, firings, and layoffs in workplaces. Invariably, for the person excluded, the experience of rejection will be hurtful. Even the smallest slights and rejections cause emotional pain, if only fleetingly so. The degree of hurt and pain caused by rejection and exclusion is probably related to the degree of importance placed by the rejected person on the individual or group doing the rejecting.

Social rejection and exclusion impede or prevent full participation in social relationships that people regard as important and meaningful. Rejection and exclusion tear at the fabric of belonging and can call into question one’s worth and identity given that social relationships are so central to who we are and to how we make sense of our lives. We are, after all, social beings dependent on others and on membership in a group for our survival. So it isn’t actually a surprise that physical pain and social rejection and exclusion act similarly in the body; they signal pain that signals trouble.

The effects on a person of being rejected or excluded are by this point in time well researched and documented. Social rejection and exclusion are associated with emotional numbness, increased aggression, reduced prosocial behavior, increased anger and reduced impulse control, impaired performance on complex intellectual tasks, sadness, depression, anxiety, reduced immune response, and poorer sleep quality to name just some of the more common consequences. Ongoing social exclusion that is characteristic of workplace mobbing, for example, can be associated with even more severe physical and mental health consequences including cardiovascular disease, post-traumatic stress syndrome, complicated depression and anxiety, and suicide.

Why then, given all that we know about the damaging physical, psychological, and social consequences of rejection and exclusion, do schools and universities continue to formalize and use policies like suspension and “required to withdraw” as routine rather than extraordinary disciplinary practices? In schools, suspensions isolate and exclude kids for offenses ranging from poor academic performance to violation of school rules and regulations to showing symptoms of public health problems like substance misuse. School suspensions segregate and stigmatize kids and outdoor suspensions often leave them to their own devices with little supervision and no intervention to help them learn and grow from whatever they did that got them into trouble. Because they are forms of social exclusion, suspensions hurt children, literally, and there is no evidence that they help them. School suspensions are increasingly being talked about in the context of the “school to prison pipeline” in which the proliferation of zero-tolerance policies and the increasingly tough enforcement of school rules are regarded as criminalizing children at younger and younger ages, and ultimately as pushing them from school into prison.

Most zero-tolerance policies end up being good examples of member-class confusion. The class of behavior is what’s not supposed to be tolerated but it’s the person not the behavior that usually gets kicked out and excluded. For example, suspending or expelling bullies doesn’t stop bullying. Bullying is a complicated social process that is not going to stop by aiming interventions primarily at targeting perpetrators. Similarly, expelling kids for substance misuse is not going to get rid of the problem of drug abuse. Trying to get rid of the problem by getting rid of the person with the problem is a theoretical confusion of logical types that has unfortunate actual consequences and effects.

At the university level, forced leaves of absence and requirements to withdraw for behaviors and offenses similar to those generating suspension at the school level do not fare well under scrutiny either. These disciplinary practices probably have their origins in the archaic practice of “rustication” in which a university student was “sent down,” sent to the country, and banished from the university community for a year or two. The requirement to withdraw is just another form of social exclusion and carries with it the same painful and frequently damaging physical, psychological, and social consequences as any other form of social exclusion. It’s hard to see how the requirement to withdraw is going to help a student learn the proper procedures for constructing academic citations or better manage their relationships with their peers. It’s easy to see how the requirement to withdraw interferes with academic and career trajectories, family and friend relationships, and the sense of being supported and cared about in the world when one makes a mistake.

If we want to hurt young people in schools and universities we will continue to use forms of social exclusion like suspensions and requirements to withdraw as fairly routine punishments that banish them from their primary life-stage communities and stigmatize them in the process. If we want to help young people we will work a lot harder to develop more restorative responses to problematic behavior that help them to reintegrate into their life-stage communities when they become estranged from them.

Maureen Duffy is a family therapist, educator, and consultant about school and workplace issues, including mobbing and bullying, and is the co-author of Mobbing: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions. Read her previous blog post “Seven ways schools and parents can mishandle reports of bullying.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers