Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1046

June 29, 2012

Barry Landau and the grim decade of archives theft

Ten years ago, responding to $200,000 worth of thefts by curator Shawn Aubitz, United States Archivist John Carlin said he had “appointed a high-level management task force to review internal security measures” at the National Archives. “A preliminary set of recommendations are under review and a number of new measures are already in place.” Four years later, an unpaid summer intern smuggled 160 documents out of the very same Archives branch. His only tool was a yellow legal pad.

In the decade since the Aubitz crime was meant to alert us to the flow of documents stolen from American archives, our nation’s most important cultural heritage institutions have undergone something of a bloodletting. Pilfered, plundered, and looted by a series of men whose sole motivation was money, the institutions that were supposed to be locked down remained more akin to open air markets. For weighty evidence, look no further than this fact: the decennial anniversary of Aubitz’s sentence coincides almost exactly with the sentencing of an archives thief who out-stole him by a factor of ten.

That man — predator historian Barry Landau — was sentenced on Wednesday to a solid seven years in prison. The reason for this sentence is the one bright spot in an otherwise grim decade in archives history and it has absolutely nothing to do with improved security or the work of task forces.

Federal sentencing is basically a numbers game. The more numbers a prosecutor can add to the level of the crime, the greater the sentence. Thanks to the work of the United States Sentencing Commission, archives theft now has a lot more numbers than it did when Aubitz was caught. This mattered a great deal in the Landau sentence.

Because his thefts involved “objects of cultural heritage,” Landau’s calculation started at a level eight crime instead of a level six. He got an added two levels because he stole from a “museum” — an umbrella term under which archives fall in the United States Code. Another two was added for theft involving pecuniary gain and another two for “a pattern of misconduct involving cultural heritage resources.” In total, this is an eight level bump. Absent these added levels, his crime would put him instead — given the number of items he stole and his time off for cooperation and acceptance of responsibility — at a total level of 19. This would have given Judge Catherine Blake a range of between 30 and 37 months in jail from which to choose. Instead, the added eight levels brought Landau to a level 27 crime, giving Judge Blake a choice of between of 70 and 87 months. (She chose 84 months, at the high end of that range.) That is a remarkable difference, and it is thanks largely to the US Sentencing Commission decision to treat our cultural heritage seriously.

I say “largely” because Landau’s sentence is dependent upon more than just the guidelines. The Cultural Heritage Resources Guideline is a tool that is only as good as the federal prosecutor using it, and I’ve seen the work of the Sentencing Commission undone by poor prosecutorial performance before. But not here. The US Attorneys prosecuting this case basically got out of Landau’s sentence all they could. In fact, their reach exceeded their grasp a little bit, in an effort to get another two levels based on an idea never used in archives theft — that Landau was the “organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor” in the series of thefts. If this had been accepted by Judge Blake, there was the possibility that Landau could have been sentenced up to 108 months in jail (fully nine years). This is an indication that the prosecution took the case seriously, and knew how to use the guidelines in defense of our cultural heritage. This is very good news.

In the aftermath of the Landau crimes there was much talk — as after Aubitz, Daniel Lorello, Lester Weber, David Breithaupt, Denning McTague, Eugene Zollman, Howard Harner, Leslie Warren, Edward Renehan, etc. — that this time was the last. There was word of “thousands of hours and dollars” spent on security and new measures and training and, well, you get the point. But what caught Landau and the rest of these men was none of that stuff. It was a hearty mix of skepticism, luck and good old fashioned attention-paying. And what is going to keep him in jail until he’s 70 is a bit of federal law few people have heard of. Maybe if more potential thieves had heard of it, we’d have fewer items of cultural heritage for sale on eBay.

There are several interesting confluences roiling the waters of archives theft right about now, making for a strange moment. As I noted, we are only one month short of the tenth anniversary of the Shawn Aubitz sentence. Landau’s sentence, at 84 months, is exactly four times what Aubitz got. But it is also twice that of Lester Weber, the archives thief who, before Landau, was sentenced most strongly for his crimes. So when does Weber, this past decade’s second most prolific archives thief, get out of prison? Today.

That these two thieves, taken together, will spend a decade behind bars is a fact that bodes both good and ill. Good that these men are now looking at serious jail time for stealing our cultural heritage; ill that they keep stealing enough of it to qualify for these harsh sentences.

Travis McDade is Curator of Law Rare Books at the University of Illinois College of Law. He is the author of The Book Thief: The True Crimes of Daniel Spiegelman and a book on a Depression-era book theft ring operating out of Manhattan forthcoming from Oxford University Press in spring 2013. He teaches a class called “Rare Books, Crime & Punishment.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Jan Zalasiewicz and Mark Williams talk four billion years of climate change

Climate change is a major topic of concern today, scientifically, socially, and politically. But the Earth’s climate has continuously altered over its 4.5 billion-year history. Geologists are becoming ever more ingenious at interrogating this baffling, puzzling, infuriating, tantalizing, and seemingly contradictory evidence. The story of the Earth’s climate is now being reconstructed in ever-greater detail — maybe even providing us with clues to the future of contemporary climate change.

Below, you can listen to Dr Jan Zalasiewicz and Dr Mark Williams talk about the topics raised in their book The Goldilocks Planet: The four billion year story of Earths Climate. This podcast is recorded by the Oxfordshire Branch of the British Science Association, whose regular SciBars podcasts can be found here.

Listen to podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Jan Zalasiewicz is Senior Lecturer in Geology at Leicester University. He is the author of The Earth After Us and The Planet in a Pebble. Mark Williams is Reader in Geology at Leicester University. Both are established researchers into palaeoclimates and climate change. Together, they are the authors of The Goldilocks Planet: The 4 Billion Year Story of Earth’s Climate. Read their previous blog post “Time-travelling to distant climates.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life science articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Do we really need magnets?

Magnetism: A Very Short Introduction

By Stephen Blundell

Do you own any magnets? Most people, when asked this question, say no. Then they remember the plastic letters sticking to their refrigerator door, or the holiday souvenir that keeps takeaway menus pinned to a steel surface in their kitchen. Maybe I do own a few, they say.

A bit more thought reveals that many more magnets are lurking elsewhere in their home. They are installed in anything containing an electric motor, from the washing machine to the hair dryer, from the kitchen blender to any appliance containing a cooling fan. Most loudspeakers and microphones contain magnets. And if you own a modern car, it will almost certainly be packed full of magnets, inside sensors measuring liquid levels, monitoring wheel speed and seat-belt status, running motors for the wipers, windows, sun-roof and starter, the pump for windscreen washer, not to mention applications in the dashboard instrumentation and loudspeaker system.

Though some magnetic applications have had their day, such as old-fashioned cathode ray tube televisions (which contained electromagnets for guiding the electron beam to the screen) and audio and video cassette tape, new ones appear. The computer hard disk is a vast array of billions of tiny magnets, each one storing the precious ones and zeros that together assemble into your digital data. If your home contains at least one computer, then you are a magnetobillionaire.

Magnetism is also one of the oldest technologies to have transferred from pure science toy to a world-changing application. That application was, of course, the magnetic compass and its introduction into Europe from China at the end of the twelfth century had a dramatic effect on the development of European exploration and colonization.

Today, as we look for alternative sources of power, magnets come to our aid. Though magnets are located inside the generators and turbines inside oil, gas and nuclear power stations, they are also in those powered by wind and tide. Even at the heart of the experimental fusion reactor being constructed in Cadarache in France (ITER, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) there are enormous superconducting magnets being constructed to confine the fiery plasma in its doughnut-shaped orbit.

Since humanity finds magnets so useful we spend a lot of effort trying to improve them. The first magnets were lodestones, the mineral magnetite (an oxide of iron) that was simply dug out of the ground. Today we have been able to fabricate incredibly powerful magnets and one of the best ones is a compound based on the element neodymium. This is one of the so-called rare-earth elements, a group of rather obscure metals that inhabit a region towards the bottom of the periodic table.

In the early nineteenth century, the element cerium was isolated from its oxide, and named after the dwarf planet Ceres. Later, cerium oxide was found also to contain another element, lanthanum, whose name appropriately enough derives from the Greek ‘to lie hidden’’. By the 1840s it was realized that, mixed in with lanthanum, was another very similar element, didymium (the name connotes “twin’’). In 1885, the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach found that didymium itself was composed of two elements, praseodymium (green twin) and neodymium (new twin).

It took a further century for people to work out how to incorporate neodymium into a particular compound (also containing iron and boron) and make incredibly strong permanent magnets. Because neodymium magnets are extraordinarily powerful, they can be used sparingly in applications. In a wind-turbine application, the use of neodymium magnets makes the turbine considerably lighter and more compact than would be the case using ferrite magnets. This greatly improves their efficiency, which is what wind turbines are all about. You find neodymium magnets in iPhones (both for driving the vibrate feature and producing the sound in the ultra-light headphones) and in the motors of modern cars such as the Prius (there is about a kilogramme of the element in each car).

The bad news is that neodymium is not very common and mining it is not very environmentally friendly. As the world’s appetite for high-end consumer electronic products increases, so does its demand for neodymium. China is the dominant provider and it has been capping exports, choking off the supply and raising prices. For a largely unknown and rather obscure element, neodymium is rapidly becoming a highly valuable commodity.

Human beings have studied magnetism for three thousand years. We’ve been using magnets for many centuries. We certainly need magnets for an amazing number of applications and to produce the power that sustains our civilization. But we can’t let up on the quest to continually discover new magnetic materials with better properties and more environmentally sustainable constituents.

Stephen Blundell is Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Mansfield College. His research is focused on magnetism and superconductivity and he is the author of Superconductivity: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2009) and most recently Magnetism: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 28, 2012

Tyson vs. Holyfield and the infamous ear-biting incident

Today is the 15th anniversary of one of the oddest episodes in the annals of sports — Mike Tyson bit the ear of Evander Holyfield in the third round of a heavyweight rematch, which led to his being disqualified from the match.

I profiled Tyson in Bad Boys, Bad Men: Confronting Antisocial Personality Disorder in 1999, and pointed out that Tyson had long been known for temper outbursts and violent behavior outside the ring. Aggression is often a sign of the psychiatric disorder “antisocial personality disorder” or ASP (and as I have not examined him cannot know if he has the disorder or not). Some violent persons channel their anger and violent tendencies in directions that earn approval or success, and in Tyson’s case, this seemed true. His combative talents that would lead to fame and (fleeting) wealth as a boxer were nurtured on the streets of Brooklyn, NY where he grew up, having been apprehended several times before age 12 for mugging and robbery. Yet, the unpredictable and harmful side of his aggression continued. His former wife Robyn Givens complained that he was violent and hot tempered during an interview with media star Barbara Walters. In 1992 he was convicted of raping an 18-year-old beauty pageant contestant and spent three years behind bars. He returned to boxing after his 1995 release, but was suspended from the sport after the ear-biting incident.

Boxer Mike Tyson in the ring at Las Vegas, Nevada, ca. October 2006. Photo by Octal@Flickr. Creative Commons License.

If there is a lesson in all of this, it is that the key to understanding one’s behavior is to look to the past. One of the few truisms in the field of psychiatry is that history repeats itself. Violent behaviors are no exception and generally follow in a long pattern of misbehavior. This is true in general and is particularly true for those with a diagnosis of ASP, which is essentially a disorder of lifelong, serial misbehavior. Its onset is in early childhood and it continues for most throughout life, though may tend to “burnout” in adulthood for some. ASP is a “hidden” disorder because, though widespread and prevalent (3.5% of the adult population), it tends to receive very little attention and is mostly ignored except by the mental health professionals who deal with its effects daily in hospitals, clinics, or prisons. As a practicing psychiatrist, one of my goals is to help educate the public about this disorder.While updating Bad Boys, Bad Men, I took another look at Tyson, to see what had happened since the ear-biting incident. As one could predict, violence continued to dog him. In 1999, Tyson attempted to break both arms of boxer François Botha and he returned to prison later that year for having assaulted two motorists following a traffic accident the prior year. He retired from boxing in 2005, but continues to have highly publicized problems that include marital infidelity, illegal drug use, and traffic violations. He recently told talk show host Ellen DeGeneres that he has improved his life by becoming sober and adopting a vegan diet. Let’s hope that Tyson has learned important life lessons and is on the path to bettering himself.

Donald W. Black, M.D., is a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa. He has recently rewritten and retitled his book on ASP, which will be out later this year as Bad Boys, Bad Men: Confronting Antisocial Personality Disorder (Sociopathy), Revised and Updated. A graduate of Stanford University and the University of Utah School of Medicine, he has received numerous awards for teaching, research, and patient care, and is listed in “Best Doctors in America.” He also serves as a consultant to the Iowa Department of Corrections. His research has focused on impulsive and self-destructive behaviors. He writes extensively for professional audiences, and his work has been featured on 20/20, Dateline, and 48 Hours.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

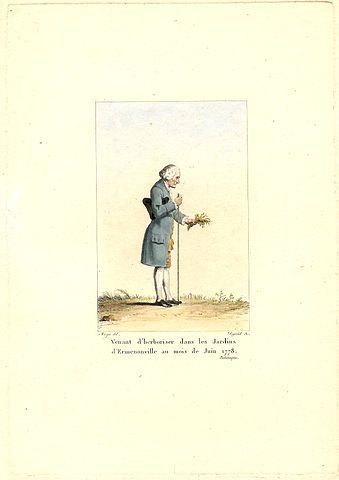

Jean-Jacques Rousseau at 300

Thursday 28 June 2012 marks the tercentenary of the birth of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the most important and influential philosophers of the European Enlightenment. The anniversary is being marked by a whole host of commemorative events, including an international conference at my own institution, the University of Leeds, which begins today. Rousseau arouses this kind of interest because his theories of the social contract, inequality, liberty, democracy, and education have an undeniably enduring significance and relevance. He is also remembered as a profoundly self-conscious thinker, author of the autobiographical Confessions and Reveries of the Solitary Walker.

Rousseau started writing his Confessions in 1764. He begins at the beginning: his birth, three hundred years ago today. His was not an auspicious entry into the world: “I was born almost dying; they despaired of saving me.” Little more a week after he was born, his mother, aged thirty-nine, died of puerperal fever: “I cost my mother her life, and my birth was the first of my misfortunes.” Rousseau felt that he had killed his mother, and this burden of guilt remained with him throughout his life. As a result, motherhood took on, for him, a quasi-sacred quality. In a letter of 22 July 1764 he warned the twenty-something marquis de Saint-Brisson that “a son who quarrels with his mother is always wrong” because “the right of mothers is the most sacred I know, and in no circumstances can it be violated without crime.” Two years earlier, in Emile, which Rousseau seems to have considered his most important work, he underlined what he saw as the crucial role mothers had in educating their children, going so far as to champion breastfeeding as the bedrock of sound society: “Let mothers deign to nurse their children, morals will reform themselves, nature’s sentiments will be awakened in every heart, the state will be re-peopled.”

Rousseau’s origins remained with him in another way too, as the opening of the Confessions also suggests: “I was born in 1712 in Geneva, the son of Isaac Rousseau and Suzanne Bernard, citizens.” Geneva at that time had three orders of citizens; the watchmaker Isaac Rousseau was one of the full citizens, who made up less than a tenth of the city’s population. As his father’s son, Jean-Jacques was immensely proud of that citizenship. While his contemporaries Voltaire and Diderot repeatedly tried in different ways to conceal their identity, for instance by publishing controversial works under the veil of anonymity, Rousseau, by contrast, followed a policy of openness and self-exposure. So, for instance, the first edition of the Social Contract, published by Marc-Michel Rey in Amsterdam in 1762, displays on the title page the name ‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva’. At a time of strict censorship, the proudly Genevan Rousseau embraced his public role as an author and what he published became a crucial part of his identity.

By the end of his life, however, we find Rousseau turning inwards. He begins his last work, the Reveries, by insisting that he is writing for himself alone, his aim being to acquire self-knowledge: “Alone for the rest of my life, since it is only in myself that I find solace, hope, and peace, it is now my duty and my desire to be concerned solely with myself. It is in this state of mind that I resume the painstaking and sincere self-examination that I formerly called my Confessions. I am devoting my last days to studying myself and to preparing the account of myself which I shall soon have to render.” Rousseau started writing the Reveries in September 1776; they were left unfinished when he died at Ermenonville on 2 July 1778, four days after his 66th birthday.

By the end of his life, however, we find Rousseau turning inwards. He begins his last work, the Reveries, by insisting that he is writing for himself alone, his aim being to acquire self-knowledge: “Alone for the rest of my life, since it is only in myself that I find solace, hope, and peace, it is now my duty and my desire to be concerned solely with myself. It is in this state of mind that I resume the painstaking and sincere self-examination that I formerly called my Confessions. I am devoting my last days to studying myself and to preparing the account of myself which I shall soon have to render.” Rousseau started writing the Reveries in September 1776; they were left unfinished when he died at Ermenonville on 2 July 1778, four days after his 66th birthday.

Rousseau had been staying at Ermenonville, some fifty kilometres north-east of Paris, as the guest of his pupil and friend the marquis de Girardin. He was buried on the little island known as the Isle of Poplars in the middle of the ornamental lake in the grounds of Girardin’s château. In October 1794, with great pomp and ceremony, his remains were transferred to the Panthéon in the centre of Paris. But his empty tomb remains on the island, although Girardin’s château is now a plush hotel. Two years after Rousseau’s death, Girardin replaced the temporary tomb with an elaborate one in the form of a Roman altar, designed by the painter Hubert Robert. Fittingly, on one side of it, a bas-relief by the sculptor Jacques-Philippe Lesueur shows a mother nursing her infant while reading Emile.

Russell Goulbourne is Professor of Early Modern French Literature at the University of Leeds. He has translated Diderot’s The Nun and Rousseau’s Reveries of the Solitary Walker for Oxford World Classics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

10 facts and conjectures about Edmund Spenser

A particular anxiety/curiosity of any author who undertakes a work of biography is whether they have discovered anything new about their subject. I’m not sure that I have any ‘smoking gun’ for Edmund Spenser (1554?-1599) that conclusively proves something that no one knew before, and there is no one single archival discovery that can be trumpeted as a particular triumph. But I think I have rearranged and rethought Spenser’s life and its relationship to his work in some new ways. Here is a list of my top ten favourite Spenser facts and conjectures, some known, some less well known.

His first wife, Machabyas Childe, is something of an enigma. She married Edmund Spenser on 27 October 1579 in St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster — a grand venue, which later witnessed the weddings of Samuel Pepys, Sir Winston Churchill, and Harold Macmillan. It is now the church of the House of Commons. Despite my best efforts I can find no other woman called Machabyas in early modern England and I have asked the Dutch and Huguenot Churches for help. She died at some point before 11 June 1594, when Edmund married Elizabeth Boyle.

Spenser was closely connected to Sir Henry Wallop, the under-treasurer in Ireland, and was involved in land deals with him. He briefly owned Enniscorthy Castle, which the Wallops held until the early twentieth century. Colm Tóibín’s family later lived there.

Spenser probably visited Wallop in Farleigh Wallop. John Aubrey interviewed someone who remembered Spenser being in the area, linking him to Alton, where a house proudly bears a plaque claiming that Spenser lived there. But Spenser surely went to Farleigh Wallop.

‘Spenser and Raleigh’, from H. E. Marshall, English Literature for Boys and Girls (London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1910). Reproduced with kind permission of Lebrecht Music and Arts.

Edmund Spenser was related to the Spencers of Althorp through his second wife, and so is related to Lady Diana Spencer (Diana, Princess of Wales). He may have had a more direct relationship too, but there is no evidence of this (probable) link.

Spenser’s writing career is very odd. He burst on to the scene at a relatively late age when he published The Shepheadres Calender in 1579, then published no more poetry until the first edition of The Faerie Queene in 1590, which appeared in a rather unimpressive form, a sign of how far his stock had fallen. However, a torrent of works followed, and by his death he had become the most celebrated poet writing in English. The hiatus is surely no accident as Edmund acquired his estate in 1589/90, just before he started to publish again.

Spenser is assumed to have been friendly with Sir Walter Raleigh and they are frequently depicted together. They clearly knew each other, but the evidence is all on Spenser’s side, not Raleigh’s. Raleigh’s widow, Elizabeth Throckmorton, annotated her son’s copy of The Faerie Queene, but seems not to have known much about Spenser and reads his poem in odd, self-serving ways.

Spenser is associated with Cork, but he probably spent far more time in Youghal, where his second wife lived. Transport was undertaken more often via waterways than roads, and the navigable rivers — the Blackwater and its tributary, the Awbeg — would have taken Spenser from his estate to Youghal rather than Cork.

Legend has it that when his Irish house, Kilcolman, was finally overrun by Hugh O’Neill’s forces in October 1598, Spenser escaped through a cave and that a child of his perished as the house burned. This is unlikely to be true. Unless he was very foolish he had probably already left for the safety of Cork city.

William Camden records that many poets threw poems and quills into Spenser’s grave at his funeral. His tomb was searched in the 1930s, but nothing was found.

There is no reliable image of Spenser or anyone connected to him. The Spenser portraits we have were discovered in the eighteenth century and are no more than dubious attributions. There is a tomb in Kilcredan Church which once contained the head of Elizabeth Boyle, but it has now been lost.

Andrew Hadfield is Professor of English at the University of Sussex and Visiting Professor at the University of Granada. He is the author of a number of works on early modern literature, including Edmund Spenser: A Life; Shakespeare and Republicanism; Literature, Travel and Colonialism in the English Renaissance, 1540-1625; Spenser’s Irish Experience: Wilde Fruyt and Salvage Soyl; and Literature, Politics and National Identity: Reformation to Renaissance. He was editor of Renaissance Studies (2006-11) and is a regular reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Treaty of Versailles signed

28 June 1919

Treaty of Versailles signed,

establishes peace after World War I

The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28 June 1919 by William Orpen. Source: Imperial War Museum Collections

On 28 June 1919, in the famous Hall of Mirrors of the French palace at Versailles, more than a thousand dignitaries and members of the press gathered to take part in and see the signing of the treaty that spelled out the peace terms after World War I. American President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister Lloyd George, and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau were the among the leaders in attendance.The treaty was the result of months of bitter negotiation, in which Wilson tried in vain to create a nonpunitive piece. Clemenceau, whose nation had suffered severely at the hands of the Germans, was disinclined to mercy. He insisted that Germany lose land (with some of it coming to France), be demilitarized, admit responsibility for the war, and pay reparations to the victors. The German delegates had no choice but to accept the terms; they were given no voice in the conditions.

On the day of the signing, two German officials walked slowly into the room, led in by military officers from the United States, Britain, France, and Italy. A member of the British government delegation described the scene: “They keep their eyes fixed away from those two thousand staring eyes, fixed upon the ceiling. They are deathly pale. They do not appear as representatives of a brutal militarism. The one is thin and pink-eyelidded. The other is moon-faced and suffering.”

After Clemenceau addressed the audience with some uncharitable remarks, the signing began. The Germans were first, followed by many others. The vast room was a buzz of conversation, as diplomats exchanged comments on the historic scene. Outside, cannons boomed in celebration, and crowds cheered.

The War to End All Wars was officially over. It would only take 20 years for the next one, caused in part by the punitive terms of the Versailles Treaty, to begin.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

To be Commander-in-Chief

On April 4, 1864, Abraham Lincoln made a shocking admission about his presidency during the Civil War. “I claim not to have controlled events,” he wrote in a letter, “but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” Lincoln’s words carry an invaluable lesson for wartime presidents.

Author Andrew J. Polsky believes when commanders-in-chief do try to control wartime events, more often than not they fail utterly. He examines Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, showing how each gravely overestimated his power as commander-in-chief.

On presidential wartime failures

Click here to view the embedded video.

On political leadership, military advice, and Afganistan

Click here to view the embedded video.

Andrew J. Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read his previous blog posts: “Obama v. Romney on Afganistan strategy,” “Mitt Romney as Commander in Chief: some troubling signs,” and “Muddling counterinsurgency’s impact.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 27, 2012

Health care reform and federalism’s tug of war within

This month, the Supreme Court will decide what some believe will be among the most important cases in the history of the institution.

In the “Obamacare” cases, the Court considers whether the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) exceeds the boundaries of federal authority under the various provisions of the Constitution that establish the relationship between local and national governance. Its response will determine the fate of Congress’s efforts to grapple with the nation’s health care crisis, and perhaps other legislative responses to wicked regulatory problems like climate governance or education policy. Whichever way the gavel falls, the decisions will likely impact the upcoming presidential and congressional elections, and some argue that they may significantly alter public faith in the Court itself. But from the constitutional perspective, they are important because they will speak directly to the interpretive problems of federalism that have ensnared the architects, practitioners, and scholars of American governance since the nation’s first days.

Federalism is the Constitution’s mechanism for dividing authority between the national and local levels. In a nutshell, it assesses which kinds of policy questions should be decided nationally — yielding the same answer throughout the country — and which should be decided locally — enabling different answers in different states. Accordingly, the basic inquiry in all federalism controversies is always the same: who should get to decide? Is it the state or federal government that should make these kinds of health policy choices? And just as important, especially in this case, is who gets to answer that question — the political branches or the judiciary? Should the Court defer to Congress’s choices in enacting the ACA, or is it the responsibility of the Court to substitute its own judgment for the legislature’s on such matters?

Here’s the thing. The reason federalism issues become so complicated — and so controversial — is that the Constitution itself, beautiful as we may think it, usually doesn’t resolve them. Indeed, the problem that pervades all federalism controversies is that the Constitution mandates but incompletely describes our federal system, in a way that forces those implementing it to rely on some external theory about what federalism is for and how it should operate when applying its vague directives to actual controversies. And unsurprisingly, there are multiple competing theories, all consistent with those directives but pushing us in different directions.

Two have especially influenced the Court’s notoriously vacillating federalism jurisprudence. The “dual federalism” approach prefers stricter separation between proper spheres of state and federal power, policed by judicially enforced constraints that trump legislative determinations. Dual federalism thinkers see federalism as a zero-sum game, in which any expansion of federal reach comes at the direct expense of state reach, and vice versa. “Cooperative federalism” rejects the zero-sum model and tolerates greater jurisdictional overlap. It urges judicial deference to federalism-sensitive policymaking because the elected branches know best, and because “political safeguards” for federalism are already embedded in constitutional design, given that national representatives are elected at the state level.

The battle between these classic contenders of federalism theory was on full display during the ACA oral arguments. For example, the question most vexing Justice Kennedy about the individual mandate was that of federal limits. If the federal government can do this, he asked, then what can’t it do? Does affirming a mandate like this one effectively eviscerate all determinable limits of federal power under the Commerce Clause, or any other? Could Congress next order us to eat broccoli, for all the same reasons it can require us to buy health insurance? In this respect, he voiced the dual federalism perspective, suggesting that judicial safeguards might be necessary to police the perilous boundaries of federal authority. (Begging the question: were it the state government ordering us to eat broccoli, would that be okay?)

Donald Verrilli, the Solicitor General defending the ACA, replied from the cooperative federalism perspective that the effective limits on federal power were located in the democratic process itself. He argued that nobody can seriously imagine a congressional mandate to eat broccoli, because to the extent Americans believe it unreasonable, they won’t elect representatives who would enact it (and they will replace any who do). He answered with the political-safeguards refrain that Congress reliably makes these difficult choices, which are more amenable to legislative deliberation than judicial review. (So as long as the Congress that orders us to eat broccoli is duly elected, federalism is satisfied?)

This moment of Supreme Court dialog, reiterating a conversation hallowed by centuries of repetition, reveals the rabbit-hole in which federalism debates have languished for too long — stuck between alternatives of jurisdictional separation or overlap, and judicial or legislative hegemony. But neither approach satisfactorily balances the roles of the different branches, and neither gives us the tools we really need to evaluate the broccoli law (or any other). A better approach to resolving federalism controversies like Obamacare frames the “who decides” question as an examination of how the challenged governance relates to the values that underlie American federalism in the first place, and who can best evaluate that in which circumstances.

Americans invented federalism to help us actualize a set of good-governance goals in operation of the new union. We created checks and balances between local and national power to protect individuals against governmental overreaching or abdication on either side. Federalism fosters local autonomy and interjurisdictional competition, and we hope it will promote governmental accountability to enhance democratic participation throughout the jurisdictional spectrum. Federalism also facilitates the problem-solving synergies that arise between the separate strengths of local and national governance for dealing with different parts of interjurisdictional problems. On balance, if governance advances these values, then it is consistent with the Constitution’s federalism directives. If it detracts from them, then we have a problem.

The trick, of course, is that while all of these values are independently good things, they are nevertheless suspended in tension with one another, such that you can’t always satisfy all of them at the same time. Sometimes local autonomy pulls in the opposite direction from checks-and-balances, which can alternatively frustrate problem-solving synergy. These tensions expose the values “tug of war” within federalism, highlighting the inevitable tradeoffs in interjurisdictional governance that makes it so difficult. Moreover, they suggest that the most robust approach for resolving federalism controversies should be tethered to consideration of how challenged governance fails or succeeds in advancing these fundamental values.

And that’s just what the Court should be doing in analyzing the ACA. Rather than asking whether the law violates some abstract limit on federal power, the Court should ask whether the trade-offs against some federalism values are justified in service to others.

The states submit that the law compromises local autonomy too much, and the federal government maintains that the need for collective-action problem-solving justifies any intrusion, which is limited by the flexibility the law confers on states to create alternative programs and to opt out entirely by declining federal funds. The plaintiffs argue that the individual mandate compromises the very individual rights that checks and balances are designed to protect, while the defendants protest that there is no recognized right to not buy health insurance, especially when the failure to do so externalizes harms to other individuals. They might further argue that both checks and synergy values are served by the use of a regulatory partnership approach to health reform rather than full federal preemption. And so on.

In a new book, Federalism and the Tug of War Within I offer a theory of Balanced Federalism to facilitate these foundational inquiries. Federalism analysis tethered to underlying constitutional values would help ensure governance that best advances them, and it would defuse the frequent constitutional grandstanding in which federalism is strategically deployed to mask substantive policy disagreements. In the end, the question should not be whether only the state or also the federal government can make us eat broccoli; it is whether there are constitutionally compelling reasons for either to do so. Either way, one thing remains clear: no matter what the Court decides this month, we are sure to be talking about it for a very long time.

This article originally appeared on the ACSblog.

Erin Ryan is currently a Fulbright Scholar in China. She is a professor of law at Lewis & Clark Law School, where she will return this summer. Ryan is also the author of Federalism and the Tug of War Within. This piece first appeared on RegBlog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Monthly etymology gleanings for June 2012

Many thanks to those who responded to the recent posts on adverbs, spelling, and cool dudes in Australia. I was also grateful for friendly remarks on the Pippi post and the German text of Lindgren Astrid’s book (in German, spunk, the Swedish name of the bug with green wings, as I now know, remained spunk).

Hopefully. With regard to hopefully, I will only add that before writing anything, I always explore the Internet resources. Therefore, I was well aware of the conflicting opinions about this word, but word columnists and bloggers receive the same questions year in, year out, and nowadays the use of hopefully is among the most common topics being discussed. The problem is not worth the passion expended on it. For whatever reason, thousands of people use this adverb sentence initially. If you don’t like it, stay away, but if you are a teacher or an editor, warn your students and authors of possible trouble and let her rip.

Little old lady in tennis shoes, its origin. This is another constantly asked question, but, unlike the previous one, it has never been answered. Many people have pointed out that the phrase, evidently an Americanism, once referred to conservative republican women and doesn’t seem to antedate the sixties of the twentieth century. I have read various explanations, most of which strike me as either inconclusive or fanciful. There indeed was an old woman who lived in a shoe and a famous song about a little old lady from Pasadena. Goody Two-shoes also deserves mention and praise. Women and shoes seem to coexist well in popular culture and folklore, but we need the immediate source of little old lady in tennis shoes and the source remains hidden.

I can only say that if, while in Europe, you meet a woman “doing” London, Paris, Rome, or any other town in her tennis shoes, you may be almost certain that she is an American. Perhaps it occurred to someone that the image of such a person symbolized the best in the indomitable American woman (under certain circumstances, indifference to style and focus on convenience: practical rather than fancy). The phrase might have been coined as a joke, tongue in cheek. If someone has more information, comments are welcome. (But comments are always welcome.) Non-specialists may not realize that the origin of some phrases is even harder to trace than the origin of individual words; yet this is how it is. Not long ago, I was asked about the phrase kick the can down the road. The image is obvious (much more so than in kick the bucket or sow one’s wild oats) and as children most of us did kick cans down the road. Yet who began to say so in politics is unknown. Probably some middle-aged Peter Pan.

Natural wine, the origin of the term. That wine is called natural which is produced without chemical and technological intervention, while organic wine, though made from organically grown grapes, does not preclude such manipulation.

Fair dinkum. Mr. Stephen Goranson sent an interesting message to his colleagues about the early use of fair dinkum. He wonders whether anything is known about this phrase. Of course, nothing is known, but I may perhaps venture a guess. Dink, a northern word, means “neat, nifty.” I suspect that it is related to dick in its multifarious senses (compare dicky bird) “something small.” Forms with “intrusive n” are common. Dinky also means “small, insignificant,” as in dinkey “small locomotive.” Dinkum looks like a pseudo-Latinism of the same type as conundrum and especially tantrum and is probably a close relative of thingum ~ thingumbob ~ thingummy and the rest. It sounds like a vulgar pronunciation of thing and means something like “the real thing,” though it may degenerate into a meaningless tag.

His or her. It is always amusing to discover that our very modern worries are as old as the hills. The hill I have recently climbed was erected in 1900. Mr. C.L.F. began his letter to The Nation (29 March 1900) so: “This is what we are coming to, now that women are taking an active part in all sorts of organizations, Municipal Art Leagues and the like: ‘The President shall have power to drop from the roll of membership the name of any member who may fail to pay …his or her dues, after he or she has, in his or her judgment, been properly notified,’ etc.” This is followed by the suggestion to introduce into English some pronoun that would spare the writer the necessity of using he or she.

By now articles and books have been written on the subject. Mr. (I assume Mr.) C.L.F. proposed the use of it. Several responses picked up where he left off. In the first of them, a point was made that in at least one German dialect jedermann “everyone” can be referred to as es, a neuter pronoun. Another correspondent cited the ingenious coinages going back to the sixties of the nineteenth century: heesh “he or she,” hizzer “his or her,” and himmer “him or her.” Mrs. C. Crozat Converse recommended the use of the neologism thon. The most interesting part of that letter is the writer’s name. In 1858 the young Charles Crozat Converse (1832-1918), an attorney and song writer, coined the word thon, which won the approval of some authorities but never caught on (sorry: the rhyme is unintentional). Converse must have delegated the writing of the letter to his wife.

On Promiscuity and Grammar: 'Scuse,' said the Elephant's Child most politely, 'but have you seen such a thing as a Crocodile in these promiscuous parts?'

Thon is a blend of that and one. Converse may not have known that in Scots thon means “that yonder.” Still later Mr. C. Alphonso Smith quoted A Midsummer Night’s Dream (II, 1, 170-172): “The juice of it on sleeping eyelids laid/ Will make or man or woman madly dote/ Upon the next live creature that it sees.” The occurrence of this epicene pronoun has been duly noted by the authors of books on Shakespeare’s grammar. What a pity that we did not follow that usage! Imagine: “When a student comes, I never make it wait: its time is precious,” “It who thinks that it is a journalist only because it has a camera and a tape recorder will soon change its views.” After all, don’t we call the leader in a game It?Water and unconscious humor. “Global leaders at the three-day U.N. Conference on Sustainable Development approved a plan to bring clean water, sanitation and energy to the world’s poor without further degrading the planet. The agreement was widely criticized for its watered-down ambitions….”

We the father. From the NYT (“New Paternity Tests Work Early in Pregnancy”): “Men who clearly know they are the father might be more willing to support the woman financially and emotionally during the pregnancy, which some studies suggest might lead to healthier babies.” The problem is that some women sleep with so many men that they have no way of finding out whose fetus they are carrying. The baby, it transpires, will be happy not to be an offspring of multiple fathers. Our writers on sociolinguistics seem to have missed a chapter with the provisional title “Grammar and Promiscuity.”

Read the next “gleanings” on August 29.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers