Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1043

July 9, 2012

The Arab Spring Needs a Season of Reconciliation

What is the meaning of justice in the wake of massive injustices? This question confronts the countries of the Arab Spring, just as it confronted tens of countries emerging from war and dictatorship over the past generation.

How the Arab Spring countries address the evils of yesterday affects their prospects for peace and democracy tomorrow. Today only Tunisia is reasonably stable. Egypt has just experienced a polarizing election and faces continued uncertainty whether its military will relinquish power. Libya’s national government does not yet control the entire country. Yemen faces a separatist south. Syrian is sundered by civil war. All are rent by the fissures that the past has bequeathed.

Thus far, most of these countries have faced the past via the international community’s dominant orthodoxy of human rights and judicial punishment. This orthodoxy received a boost this past March when the International Criminal Court, the body in which international lawyers and human rights activists have placed their greatest hopes for global justice, secured its first conviction in ten years of operation. In April, the Special Court for Sierra Leone convicted arch war criminal Charles Taylor. Turning to the Arab Spring, the ICC has indicted the late Muammar Qaddafi’s son, Seif, while Tunisia and Egypt have each tried their erstwhile heads of state and several high-level officials. Yemen has adopted a broad amnesty. Syria will surely face the question of trials at some point.

Accountability for arch war criminals is intrinsically just and can fortify the rule of law. But judicial prosecution is not enough. There is little evidence that international tribunals have contributed stability to countries like Rwanda and Yugoslavia whose perpetrators they have tried and sentenced in substantial numbers. The limitation of trials is that they leave untended a wide range of wounds which, like buried landmines, will explode in revenge and retribution if they are not disinterred and defused.

More promising for lasting peace is a different paradigm that has emerged though the fitful politics of past evil: reconciliation. The concept finds its oldest and deepest expression in religious traditions. It is religious leaders like Pope John Paul II and Archbishop Desmond Tutu who have done most to bring reconciliation into global politics. Relevant to the Arab Spring, reconciliation is commended by the Quran and is practiced in rich Middle Eastern tribal rituals known as musalaha.

In Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, reconciliation means the holistic restoration of right relationship. In the political realm reconciliation is advanced through a portfolio of practices that redress the wide range of wounds that political injustices inflict. These practices of reconciliation aim at wider transformative restorations than do rights or judicial punishment.

Truth commissions for instance — over 40 of which have taken place over the past three decades — confer far more than a right to truth but also acknowledgment of the suffering of victims on the part of public authorities, fellow onlookers, and even sometimes perpetrators. When truth commissions are at their best, victims are restored through recognition and often drop their demands for revenge.

Even punishment can be practiced restoratively. Following Timor Leste’s war of the final quarter of the twentieth century, village forums were held in which perpetrators of crimes, victims, and community members would gather before tribal elders, tell how the crimes affected them, and exchange apology and forgiveness, upon which elders would prescribe a reintegrative form of punishment like community service. Although such forums are inadequate to try perpetrators of the worst crimes, they can redress thousands of lesser crimes in restorative fashion.

The most distinct practice of reconciliation is forgiveness. It involves no right but is rather an act of good will on the part of a victim. In most religions forgiveness is no mere dismissal of charges but rather an act that constructs right relationship. Passages in the Quran teach that even in the case of murder, while a victim’s relative may demand death as retribution, it is even better for him to forgive the murderer while receiving diya, or compensation. In the wake of political injustices, forgiveness has been practiced widely in Uganda, South Africa, and Sierra Leone among other places.

Working together, practices of reconciliation can help overcome the divisions that endanger the Arab Spring. As of now, only Tunisia — where democratic stability is greatest — speaks of robust reconciliation. Its Ministry of Human Rights and Transitional Justice has proposed a holistic plan involving truth telling, apologies, and reparations. Even here, progress has been mixed, while other countries have proposed far less. Talk of forgiveness is altogether rare. But lest the Arab Spring revert to wintry bedlam, a politics of reconciliation is needed.

Daniel Philpott is Associate Professor of Political Science and Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame and author of Just and Unjust Peace: An Ethic of Political Reconciliation (Oxford, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on current affairs on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The Crowd in the Capuchin Church

Today in 1775, Matthew Lewis, author of The Monk, was born. Set in the sinister monastery of the Capuchins in Madrid, The Monk is a violent tale of ambition, murder, and incest. The great struggle between maintaining monastic vows and fulfilling personal ambitions leads its main character, the monk Ambrosio, to temptation and the breaking of his vows, then to sexual obsession and rape, and finally to murder in order to conceal his guilt. Here is an extract from the first chapter.

Scarcely had the Abbey-Bell tolled for five minutes, and already was the Church of the Capuchins’ thronged with Auditors. Do not encourage the idea that the Crowd was assembled either from motives of piety or thirst of information. But very few were influenced by those reasons; and in a city where superstition reigns with such despotic sway as in Madrid, to seek for true devotion would be a fruitless attempt. The Audience now assembled in the Capuchin Church was collected by various causes, but all of them were foreign to the ostensible motive. The Women came to show themselves, the Men to see the Women: Some were attracted by curiosity to hear an Orator so celebrated; Some came because they had no better means of employing their time till the play began; Some, from being assured that it would be impossible to find places in the Church; and one half of Madrid was brought thither by expecting to meet the other half. The only persons truly anxious to hear the Preacher were a few antiquated devotees, and half a dozen rival Orators, determined to find fault with and ridicule the discourse. As to the remainder of the Audience, the Sermon might have been emitted altogether, certainly without their being disappointed, and very probably without their perceiving the omission.

Whatever was the occasion, it is at least certain that the Capuchin Church had never witnessed a more numerous assembly. Every corner was filled, every seat was occupied. The very Statues which ornamented the long aisles were pressed into the service. Boys suspended themselves upon the wings of Cherubims; St. Francis and St. Mark bore each a spectator on his shoulders and St. Agatha found herself under the necessity of carrying double. The consequence was, that in spite of all their hurry and expedition, our two newcomers, on entering the Church, looked round in vain for places.

However, the old Woman continued to move forwards. In vain were exclamations of displeasure vented against her from all sides: In vain was She addressed with – ‘I assure you, Segnora, there are no places here.’ – ‘I beg, Segnora, that you will not crowd me so intolerably!’ – ‘Segnora, you cannot pass this way. Bless me! How can people be so troublesome!’ – The old Woman was obstinate, and on She went. By dint of perseverance and two brawny arms She made a passage through the Crowd , and managed to bustle herself into the very body of the Church, at no great distance from timidity and in silence, profiting by the exertions of her conductress.

‘Holy Virgin!’ exclaimed the old Woman in a tone of disappointment, while She threw a glance of enquiry round her; ‘Holy Virgin! What a heat! What a Crowd! I wonder what can be the meaning of all this. I believe we must return: There is no such thing as a seat to be had, and nobody seems kind enough to accommodate us with theirs.’

This broad hint attracted the notice of two Cavaliers, who occupied stools on the right hand and were leaning their backs against the seventh column from the Pulpit. Both were young, and richly habited. Hearing this appeal to their politeness pronounced in a female voice, they interrupted their conversation to look at the speaker. She had thrown up her veil in order to take a clearer look round the Cathedral. Her hair was red, and She squinted. The Cavaliers turned round , and renewed their conversation.

‘By all means,’ replied the old Woman’s companion; ‘By all means, Leonella, let us return home immediately; The heat is extensive, and I am terrified at such a crowd.’

These words were pronounced in a tone of unexampled sweetness. The Cavaliers again broke off their discourse, but for this time they were not contented with looking up: Both started involuntarily from their seats, and turned themselves towards the Speaker.

The voice came from a female, the delicacy and elegance of whose figure inspired the Youths with the most lively curiosity to view the face to which is belonged. This satisfaction was denied them. Her features were hidden by a thick veil; But struggling through the crowd had deranged it sufficiently to discover a neck which for symmetry and beauty might have vied with the Medicean Venus. It was of the most dazzling whiteness, and received additional charms from being shaded by the tresses of her long fair hair, which descended in ringlets to her waists. Her figure was rather below than above the middle size: It was light and airy as that of an Hamadryad. Her bosom was carefully veiled. Her dress was white; it was fastened by a blue sash, and just permitted to peep out from under it a little foot of the most delicate proportions. A chaplet of large grains hung upon her arm, and her face was covered with a veil of thick black gauze. Such was the female, to whom the youngest of the Cavaliers now offered, while the other thought it necessary to pay the same attention to her companion.

Matthew Lewis was an English novelist and dramatist. Inspired by German horror romanticism and the work of Ann Radcliffe, Lewis produced his masterpiece, The Monk, at the age of nineteen. It contains many typical Gothic elements: seduction in a monastery, lustful monks, evil Abbesses, bandits, and beautiful heroines. But, as the Introduction to this new edition by Emma McEvoy (Lecturer, Goldsmith’s College) shows, Lewis also played with convention, ranging from gruesome realism to social comedy, and even parodied the genre in which he was writing.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Ensuring a good death: a public health priority

The quality of dying, and maintaining quality of life for those who are dying and those caring for them, is an inherent aspect of public health. In developed and developing societies everyone is affected by death and dying (either directly or indirectly, for instance in case of a dying relative) and it affects several aspects of their health and wellbeing. Adequate health promotion can improve the circumstances in which these people need to cope with death and dying and is thus susceptible to improve several aspects of health. Sadly, though the manner in which people die and the quality of dying has blatantly been neglected as a priority of public health, partly because death and dying, in all its aspects, have rather been regarded as antonymous to health and a failure of health care.

The one health care discipline that has been concerned of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness is palliative care. However, to date it has usually applied a very individual approach to the issue with the needs of the dying person as the primary concern and responsibilities towards the family and the support network also considered. Such an individual approach to the end of life may be sufficient and in fact most appropriate to meet the needs of the dying person and all other actors involved, but it may be inadequate to address the problems on a population level.

Why we should talk more about death

There is an urgent need for public health to adopt dying and palliative care in all its aspects as a major public health priority, for instance in national health strategies, and for palliative care to adopt a public health perspective to improve circumstances of dying at a population level.

The sociological justification for this is straightforward; first of all, ageing of the population will result in a relatively large group of older people, many of which will face certain health problems or care needs, which will confront societies with the public health challenge of organizing long term and end-of-life care for older patients.

The 100 club

With the number of deaths also on the rise (and expected to increase in the coming decades) an increasing number of people are affected by death in terms of informal caregiving and grieving.

Protecting the health and wellbeing of the population directly or indirectly involved with death and dying is a huge public health challenge. Currently, high quality end of life care is not yet available in most parts of the world, and in those countries where it is available it is not accessible or not initiated timely for all in need, independent of their disease, age, gender, socioeconomic, or ethnic background. Largely as a result of that, a large majority receives overly aggressive treatment until death or shortly before death, has undertreated psychological and physical symptoms at the end of life, and is not able to die in a place or manner that accords with their personal preferences.

There are pervasive cultural, attitudinal, structural, and financial barriers to the optimal accessibility of palliative or end of life care. Public health researchers and policy makers must identify these barriers and come up with solutions to overcome them in order to ensure a good death. This can involve several public health strategies such as:

Societal monitoring of the quality of palliative care provision and its accessibility.

palliative care integration into acute and chronic care models

Implementation of end-of-life practice guidelines based on culturally-sensitive quality indicators

Improving communication and at and about the end of life and promoting models of advance care planning

Guaranteeing access to adequate drugs (e.g. opiates) and treatment

Development of good end-of-life care in long term care settings, in primary care, and in hospitals

A start can be made by developing a policy based on the premise that palliative care is a human right and hence all people have equal rights to access it. To be successful in this the current understandings of end of life care need to be expanded from a clinical to a public health perspective.

Joachim Cohen and Luc Deliens are the editors of A Public Health Perspective on End of Life Care.

Joachim Cohen, health scientist and medical sociologist, is a professor and senior researcher of the End-of-Life Care Research Group of Ghent University & Vrije Universiteit Brussel and a postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders. He has published 50 peer reviewed articles on end-of-life and palliative care and was awarded for his research with the Prix Elisabeth Kubler-Ross pour jeune chercheur and the Young Inverstigator Award of the European Association for Palliative Care.

Luc Deliens is a professor of public health and palliative care at the Department of Public and Occupational Health, EMGO Institute VU medical center and is chair of the End-of-Life Care Research Group of Ghent University & Vrije Universiteit Brussel. He has published over 150 peer reviewed articles on end-of-life and palliative care and has received several scientific awards. He is also Co-Chair of the Research Network of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

View more about this book on the

July 7, 2012

Alan Turing, Code-Breaker

Germany’s Army, Air Force, and Navy transmitted many thousands of coded messages each day during the Second World War. These ranged from top-level signals, such as detailed situation reports prepared by generals at the battle fronts and orders signed by Hitler himself, down to the important minutiae of war, such as weather reports and inventories of the contents of supply ships. Thanks to Alan Turing and his fellow codebreakers, much of this information ended up in allied hands — sometimes within an hour or two of its being transmitted. The faster the messages could be broken, the fresher the intelligence that they contained. On at least one occasion an intercepted Enigma message’s English translation was being read at the British Admiralty less than 15 minutes after the Germans had transmitted it.

On the first day of war, at the beginning of September 1939, Turing took up residence at Bletchley Park, the ugly Victorian Buckinghamshire mansion that served as the wartime HQ of Britain’s top codebreakers. There Turing was a key player in the battle to decrypt the coded messages generated by Enigma, the German military’s typewriter-like cipher machine. Turing pitted machine against machine. The prototype model of his anti-Enigma ‘bombe’, named simply Victory, was installed in the spring of 1940. His bombes turned Bletchley Park into a codebreaking factory. As early as 1943 Turing’s machines were cracking a staggering total of 84,000 Enigma messages each month — two messages every minute. Turing personally broke the form of Enigma that was used by the U-boats preying on the North Atlantic merchant convoys. It was a crucial contribution. Convoys set out from North America loaded with vast cargoes of essential supplies for Britain, but the U-boats’ torpedoes were sinking so many of the ships that Churchill’s analysts said Britain would soon be starving. “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril,” Churchill said later. Just in time, Turing and his group succeeded in cracking the U-boats’ communications to their controllers in Europe. With the U-boats revealing their positions, the convoys could dodge them in the vast Atlantic waste.

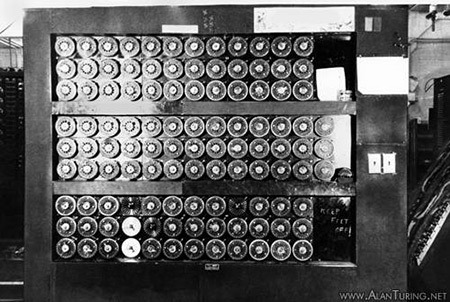

The Bombe. Turing's Bombes turned Bletchley Park into a codebreaking factory. Source: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, USA.

Turing also searched for a way to break into the torrent of messages suddenly emanating from a new, and much more sophisticated, German cipher machine. The British codenamed the new machine Tunny. The Tunny teleprinter communications network, a harbinger of today’s mobile phone networks, spanned Europe and North Africa, connecting Hitler and the Army High Command in Berlin to the front line generals. Turing’s breakthrough in 1942 yielded the first systematic method for cracking Tunny messages. His method was known at Bletchley Park simply as ‘Turingery,’ and the broken Tunny messages gave detailed knowledge of German strategy — information that changed the course of the war. “Turingery was our one and only weapon against Tunny during 1942-3,” explains ninety-one year old Captain Jerry Roberts, once Section Leader in the main Tunny-breaking unit known as the Testery. “We were using Turingery to read what Hitler and his generals were saying to each other over breakfast, so to speak.”

Turingery was the seed for the sophisticated Tunny-cracking algorithms that were incorporated in Tommy Flowers’ Colossus, the first large-scale electronic computer. With the installation of the Colossi — there were ten by the end of the war — Bletchley Park became the world’s first electronic computing facility. Turing’s work on Tunny was the third of the three strokes of genius that he contributed to the attack on Germany’s codes, along with designing the bombe and unravelling U-boat Enigma. Turing stands alongside Churchill, Eisenhower, and a short glory-list of other wartime principals as a leading figure in the Allied victory over Hitler. There should be a statue of him in London among Britain’s other leading war heroes.

Some historians estimate that Bletchley Park’s massive codebreaking operation (especially the breaking of U-boat Enigma) shortened the war in Europe by as many as two to four years. If Turing and his group had not weakened the U-boats’ hold on the North Atlantic, the 1944 Allied invasion of Europe (the D-Day landings) could have been delayed perhaps by about a year or even longer, since the North Atlantic was the route that ammunition, fuel, food, and troops had to travel in order to reach Britain from America. Harry Hinsley, a member of the small, tight-knit team that battled against Naval Enigma and who later became the official historian of British intelligence, underlined the significance of the U-boat defeat. Any delay in the timing of the invasion, even a delay of less than a year, would have put Hitler in a stronger position to withstand the Allied assault, Hinsley points out. The fortification of the French coastline would have been even more formidable, huge Panzer Armies would have been moved into place ready to push the invaders back into the sea — or, if that failed, then to prevent them from crossing the Rhine into Germany — and large numbers of rocket-propelled V2 missiles would have been raining down on southern England, wreaking havoc at the ports and airfields tasked to support the invading troops.

In the actual course of events, it took the Allied armies a year to fight their way from the French coast to Berlin; but in a scenario in which the invasion was delayed, giving Hitler more time to prepare his defences, the struggle to reach Berlin might have taken twice as long. At a conservative estimate, each year of the fighting in Europe brought on average about seven million deaths, so the significance of Turing’s contribution can be roughly quantified in terms of the number of additional lives that might have been lost if he had not achieved what he did. If U-boat Enigma had not been broken and the war had continued for another 2-3 years, a further 14-21 million people might have been killed. Of course, even in a counterfactual scenario in which Turing was not able to break U-boat Enigma, the war might still have ended in 1945 because of some other occurrence, also contrary-to-fact, such as the dropping of a nuclear weapon on Berlin. Nevertheless, these colossal numbers of lives do convey a sense of the magnitude of Turing’s contribution.

B. Jack Copeland is the Director of the Turing Archive for the History of Computing, and author of The Essential Turing, Alan Turing’s Electronic Brain, Colossus, and Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age. Read the new revelations about Turing’s death after Copeland’s investigation into the inquest.

Visit the Turing hub on the Oxford University Press UK website for the latest news in the Centenary year. Read our previous posts on Alan Turing including: “Maurice Wilkes on Alan Turing” by Peter J. Bentley, “Turing : the irruption of Materialism into thought” by Paul Cockshott, “Alan Turing’s Cryptographic Legacy” by Keith M. Martin, and “Turing’s Grand Unification” by Cristopher Moore and Stephan Mertens, and “Computers as authors and the Turing Test” by Kees van Deemter.

For more information about Turing’s codebreaking work, and to view digital facsimiles of declassified wartime ‘Ultra’ documents, visit The Turing Archive for the History of Computing. There is also an extensive photo gallery of Turing and his war at www.the-turing-web-book.com.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 6, 2012

The Meaning of the Codex Calixtinus, Then and Now

The temporary disappearance of the Codex Calixtinus was devastating to scholars and the general public alike because of its historical significance and special status as a symbolic object representing an important component of Spain´s national identity. This monumental collection of texts, images, and music relating to the cult of Saint James the greater in Santiago de Compostela is the most eloquent testimony (besides the Cathedral of Santiago itself) to the process by which James of Zebedee came to be revered as the Apostle of Spain. By the eleventh century, the belief that James had preached the Gospel in the Iberian peninsula had accrued onto the conviction that his body had been translated to Santiago.

The enduring appeal of Saint James’s continued presence in Galicia nourished a thriving pilgrimage to his tomb. The pilgrimage became a signal feature of European religious and cultural history; as such, it was crucial to the region´s economic and political development. Gradually, Santiago (both the saint and his resting place) became intimately linked with royal patronage and with the history of Spain.

Like the saint’s cult, the idea of Spain long remained a fluid entity that shifted with the political landscape.

The Codex Calixtinus is an important witness to the construction of the Santiago’s cult in the middle decades of the twelfth century, when the French influence in the Iberian peninsula was at a high point. Given the cultural and political environment in which the pilgrimage to Santiago developed, it comes as no surprise that the manuscript contains musical notation typical of central France. A section of the Codex added in the mid-twelfth century comprises a collection of polyphonic compositions and a complete mass and office for the feast of Santiago.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The unique set of chants for Santiago was apparently notated in the area around Nevers, and possibly connected to the church of the Madeleine at Vezelay. Although other texts in the Codex (such as the pilgrim’s guide to Santiago, the miracles of Saint James, and an account of the saint’s translation from the Holy Land to Compostela) are all of equal importance in the creation of the cult, the music for the veneration of the saint evokes most suggestively the expression of devotion to the saint in performance. This music also reveals the rich cross-fertilization that resulted from the contribution of French clergy.

It may seem ironic that a book so central to the idea of the Spanish nation should be so deeply imprinted by the involvement of French clerics, but this is a pattern in the history of Spain. In the eighteenth century, the accession of the Bourbon dynasty to the Spanish throne yielded new inroads for French culture in Spain and led to another phase in the formation of modern Spanish identity. One of the most significant projects under the Bourbons was the inventory of the ecclesiastical archives. Andrés Marcos Burriel, the Jesuit scholar entrusted with the inventory of holdings in Toledo Cathedral, the primatial see, apparently took a special interest in the Codex Calixtinus as had generations of historians before him. From the twelfth century onward, copies and partial copies of the codex were made for all kinds of reasons.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Around 1750, excerpts from the codex were compiled for Burriel, to assist him in his goal of writing a new ecclesiastical history of Spain. For Burriel, as for us, the contents of the Codex Calixtinus were both old and new. The texts, music, and images in the precious book now restored to the cathedral treasury are the traces of the process by which medieval saints’ cults were formed, and at the same time, they are the vestiges of a pilgrimage that continues to hold meaning today for countless thousands.

Susan Boynton, Professor of Historical Musicology at Columbia University, has published on medieval Western liturgy, chant, monasticism, prayer, the history of childhood, and troubadour song. She is the author of Silent Music: Medieval Song and the Construction of History in Eighteenth-Century Spain and Shaping a Monastic Identity: Liturgy and History at the Imperial Abbey of Farfa, 1000-1125 (Cornell University Press, 2006) for which she won the American Musicological Society’s Lewis Lockwood Award in 2007. She is also coeditor of volumes on music and childhood, on the Bible in the Middle Ages, and on the abbey of Cluny.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Hitting the trail while wearing red, white, and blue

This summer, nonfiction reading lists are replete with voices from the battlefield. On bestseller lists, accounts from World War II are only a few steps away from inside perspectives on today’s Seal Teams. And regardless of the theater of battle or the decade of conflict, one cannot turn the final pages of these books without a deep appreciation of the value of team for those in conflict. The fighting unit, the organizational basis by which men and women at war live their daily lives, inspires tremendous loyalty — appropriate to the life and death contingencies members of the team face together. In battle, being a strong team member can save your life as well as the lives of those around you.

Yet, when tours of duty end, and service men and women return to the embrace of their families, a sense of team membership may be lost. It is not as if the family unit is not of tremendous value, but a ready role within the family team may take months of adjustment to realize. And so many skills and coping strategies are left behind with this transition; what worked for the war team often will not work for the home team. Without a clear role for civilian life, many will hunker down, looking for solace from the isolated bunker of the couch. That isolation can leave men and women not only struggling with memories of the challenges, horrors, and losses of their service, but alone with darker thoughts and the inaction that can worsen depression and anxiety.

The effects of isolation are daunting for civilians as well. A decade ago, Robert Putnam detailed the challenges of isolation in his book, Bowling Alone, showing that Americans are becoming increasingly disconnected from one another, and that this disconnection — the declining memberships in clubs, PTAs, church groups, and bowling teams — has a real cost to both our moods and physical health. Connections save lives. I mention this because, this morning, with a flag emblem on my right shoulder, I showed up for my first team event in decades. I showed up for Team Red, White & Blue (Team RWB).

The event was a training run at 9:00 on a Sunday, and I wanted to meet the team — individuals who had joined Team RWB and its mission to transform the way wounded veterans are integrated into civilian life. Exercise and team membership are crucial components of the Team RWB approach. The team offers new relationships to veterans through both one-on-one interactions with community members as well as participating in athletic events. Exercise is used both as an organizing focus for team members and as a healing intervention in its own right. An abundance of research makes clear that exercise can have powerful effects on reducing depression and anxiety; those who exercise report better moods, less stress, less anger, and a better sense of social connection. More importantly, those depressed and anxious individuals who start exercise can achieve benefits equal to that offered by antidepressant medications or therapy.

But it is hard to start exercise, especially from the vantage point of the couch. This is the value of Team RWB, to have personal connections help to pull you off the couch and on to the walking or running trail. Team RWB makes use of its community and athletic members to provide information, training, and companionship to veterans who want to recharge want to recharge themselves both physically and mentally. It provides a team to veterans who may have left part of their sense of connection in the war zone. And it provides the same sort of team to those civilians who have been looking for a way to give back to the veterans who have served so loyally.

This morning, I ran in my red, white and blue team shirt, with similarly dressed team members to the left and right of me. It was a simple run, but with this first act, I had a sense of giving back, starting the process of trying to offer something to the veterans who bore the cost of war for me.

Michael Otto is a Professor of Psychology at Boston University and co-author of Exercise for Mood and Anxiety: Proven Strategies for Overcoming Depression and Enhancing Well-Being.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

A New ‘Modern Prometheus’?

Early in Ridley Scott’s science fiction (SF) film Prometheus, archaeologists discover a cave-painting of what seems to be a human figure pointing at a group of stars. Having gathered strikingly similar images from ancient and prehistoric cultures around the globe, the archaeologists take this most recent discovery as confirming their theory about the origin of humankind: we were placed here, created, by extraterrestrials. The archaeologists refer to those extraterrestrials as ‘Engineers’ (“What did they engineer?” asks another character. “They engineered us.”).

The Sacrificial Engineer. Prometheus. © 2011-2012 Prometheus-Movie.com.

But of course we viewers are encouraged to think of them as gods. One of the archaeologists, the film’s protagonist, is devoutly Christian, and when there is a mission to find any living ‘Engineers’ on a habitable planet at that group of stars, she is allowed to come along because the mission’s backer wanted it to include “a true believer.” It is therefore pointed when, later in the film after all has gone to hell, that same “true believer” gives voice to an evident truth: “We were so wrong.”

Prometheus thus raises a modern version of an ancient question: What if we are wrong about the gods? Have we been misled, or like those overeager archaeologists have we been misreading sacred texts, or treating as ‘sacred’ what is merely ancient?

Prometheus vividly exemplifies how modern science fiction is a rich site of classical reception. As we discuss in a recent essay in Oxford’s Classical Receptions Journal, this is evident as early as modern science fiction’s arguable point of origin, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). Shelley’s novel famously envisions what would happen if a human being acted like God by creating (human?) life. It is thanks in part to Shelley’s vision that modern SF frequently depicts the result of scientific inquiry as an object lesson in unintended consequences.

Importantly, this seminal modern science fiction text represents itself as an outgrowth of earlier literature. The epigraph on its title page [University of Glasgow, Special Collections] consists of haunting lines from Milton: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay / To mould me man? Did I solicit thee / From darkness to promote me … ?” (Paradise Lost 10. 743-45). Since the speaker is Adam, the epigraph suggests a layered sympathy with the creature, and thus the novel raises some question or doubt about the act of creation and the creator himself.

Such doubt or ambivalence is also suggested by Frankenstein’s subtitle: “The Modern Prometheus.” As we note in our essay in some detail, this allusion to Greco-Roman mythology highlights a different interplay between humankind, technology, and the divine. In outline, Prometheus took pity on mortals, stole fire from Zeus, and passed this technology to humans. He thus gave humankind the means to better its condition (heat, warmth, cooked food, metallurgy) as well as to communicate with the gods (via burnt offering). Depending on the ancient text, Prometheus is also said to have given other gifts, including writing, mathematics, and astronomy.

But Prometheus’ generosity also led to greater suffering for humankind. Again depending on the ancient text, this includes the first woman, Pandora, created as a bane for men, and a sense of shame (aidôs), albeit alongside justice (dikê) as a necessary basis for society. Prometheus himself was famously punished for his action, chained to a rock where his liver was eaten daily by an eagle. Prometheus thus figures deep ambivalence about the benefits and unintended consequences of technology.

So what might knowledge of ancient Prometheus tell us about Scott’s film, and vice versa? Prometheus is the name of the spaceship. The mission’s backer, Peter Weyland, tells the crew that “Prometheus wanted to give man equal footing with the gods.” In context of the ancient stories, Weyland’s version is curious. Nowhere in our ancient sources does Prometheus seek to make mortals equal to the gods, only to aid them in survival. Weyland’s vision of ‘equality’ is presumptuous, even hubristic. (Spoiler alert: late in the film we learn that Weyland’s true purpose is hubristic indeed, as he seeks the Engineers in the hope that they can save him from death.)

But to stop at identifying Weyland’s or Scott’s version as simply ‘mistaken’ would be to miss a deeper feature of the film as an example of classical reception in science fiction. Although Weyland’s version of the myth does not ‘follow’ any known ancient version, neither was there an ancient ‘consensus’: there is no single, ‘true’ version of the Prometheus myth. We would be hard-pressed, then, to find truly decisive reasons to prefer any ancient version over Scott’s. Any take on Prometheus, or for that matter any ancient story comes from a certain perspective or position. As Weyland’s cynical representative acknowledges, everyone has an agenda.

Ampule Room View. Prometheus. © 2011-2012 Prometheus-Movie.com

In our view Prometheus is so aware of this as to be centered around the problem of ‘misreading’, whether it is of archaeological evidence and ancient myth, more recent literature and modern film, or even scientific method and knowledge. (See an overview of many of the film’s source texts.) Both as a work of art and as a site for reception, Prometheus seems to suggest that, for better or worse, ‘misreading’ is a fundamental feature of human knowledge. From this perspective, at the very least we may see Prometheus in light of how it responds to its own mythic tradition, the Aliens film series. Perhaps more adventurously, misreadings may be understood not as failures to comprehend or to revere the past, but as creative acts of reception suggesting new, hybrid possibilities for the future of human knowledge and the humanities, perhaps even — in the case of science fiction as of Greco-Roman myth — humankind.

We return, then, to the question of whether we have mistaken our gods, in particular by misunderstanding ancient texts, be they the Greco-Roman Classics or, as in Prometheus, the base pairs constituting our DNA. Have we been wrong about a fundamental part of the human condition? Even more disorientingly, are we on the verge of discovering or experiencing things about which the Classics, and the humanistic tradition they inspired, can in fact say nothing? Whether or not we think it is represented by Scott’s film, are we therefore in need of a new ‘modern Prometheus’?

Benjamin Stevens and Brett M. Rogers are the authors of “Classical receptions in science fiction” in Classical Receptions Journal which you can read free for a limited time.

Benjamin Stevens [on Facebook; on Twitter] is assistant professor of Classical Studies at Bard College, where he also contributes to the Language and Thinking program, the concentration in Mind, Brain, and Behavior, and the Bard Prison Initiative. A specialist in Latin literature and classical reception, Professor Stevens has written about Lucretius, Ovid, Pliny, and other ancient authors in relation to fields like linguistics, philosophy of mind, and sensorial anthropology, and is helping to pioneer the study of classical reception in comics, science fiction, and fantasy. He has a book on Catullus’ poetics of silence forthcoming from the University of Wisconsin Press. Professor Stevens has also published poetry of his own and is director of education for the Contemporary A cappella Society.

Brett M. Rogers is Assistant Professor of Classics at the University of Puget Sound. A specialist in Greek literature and classical reception, he has written on Greek drama, Plato, performance, and classical reception in comics and science fiction. His recent theatrical credits including serving as dramaturg for a production of Euripides’ Trojan Women (2007) and chorêgos for Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (2009), and he is a National Program Scholar for the Ancient Greeks / Modern Lives program in the US. His current project is on troubling teachers in archaic Greek poetry and Athenian drama.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Why do humans talk?

Languages: A Very Short Introduction

By Stephen R. Anderson

Human languages are not biological organisms, despite the temptation to talk about them as “being born,” “dying,” “competing with one another,” and the like. Nonetheless, the parallels between languages and biological species are rich and wonderful. Sometimes, in fact, they are downright eerie. Recently, for example, it was shown that the areas of the world that are richest in their biodiversity are also among the most diverse in the number of languages spoken by their indigenous people. Absolutely no logical reason exists for such a correlation: there is only one species (Homo sapiens) that has language, but the members of that species that live in places they share with many other species tend to have similarly rich diversity of language.

We think we know reasonably well what makes a species in the biological sense, but the notion is surprisingly hard to make precise, as a vast and contentious literature attests. We ought to be able to identify members of different species by their characteristic appearance, patterns of behavior, etc. But if that is the case, it is hard to understand why we call chihuahuas, pit bulls, and Bernese mountain dogs all “dogs” and assign them to one species (Canis lupus familiaris, a subspecies of the grey wolf, Canis lupus), while leopards (Panthera pardus), snow leopards (Uncia uncia), and clouded leopards (Neofelis nebulosa) are assigned to three different species — indeed, in some taxonomies, to three different genera. Compare this with the fact that we think of the English spoken across North America, Britain, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India as all forms of the same language, despite considerable and quite obvious differences, while we treat the speech of Maastricht and Aachen as two distinct languages (‘Dutch’ and ‘German’ respectively).

Biological species change over time, members of a species differentiate from one another and new species come into existence, through the accumulation of small changes in their genetic constitution. Similarly, languages change over time, their local forms diverge and new ones appear through the accumulation of small changes (especially sound changes, but also changes in aspects of their grammar). Darwin was already struck by this parallel, and in The Descent of Man observed that “[t]he formation of different languages and of distinct species, and the proofs that both have been developed through a gradual process, are curiously the same.” The notion of ‘descent with modification’ is a fundamental explanatory concept in both evolutionary biology and historical linguistics.

One way biologists have tried to make the notion of ‘species’ more precise is by suggesting that organisms belong to the same or different species depending on whether they can produce (fertile) offspring. This approach does not get very far in the plant world, where hybridization between members of distinct species is extremely common, and even among animals it provides an imperfect definition. See the ability of mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) to virtually wipe out other Anas species through rampant inter-breeding. The linguistic parallel is the notion that two forms of speech constitute separate languages if they are not mutually comprehensible. Again the problems with this seemingly obvious criterion are clear. Speakers of Danish can largely understand Swedish and Norwegian (but not always vice versa), and speakers of Slavey, a Canadian Athabaskan language, are reported to have responded “they’re speaking our language!” upon seeing a television program about the Navajo (whose quite distinct language is historically related to theirs). On the other hand, speakers of ‘Italian’ from Venice and Naples are almost certain to have to resort to something other than their native language to make themselves understood to one another.

The notion of distinct species could surely be made precise in terms of distinct genetic makeup, of differences in the structure of the DNA of the organisms in question, but different individuals that we surely want to treat as members of the same species will also differ in significant ways in their DNA. Some such differences ‘count’ for species identity while others simply represent variation within the species; but the treatment of any particular difference as one way or the other cannot be decided in a non-arbitrary manner without knowing in advance how we want the answer to come out.

The linguistic analog here is the notion that different languages not only have different words, but also different grammars, so we ought to be able to identify distinct languages by looking for differences in grammatical structure. Again, though, we find very considerable differences among the grammars of people who would otherwise be seen as speaking the same language. In the American South, for example, many speakers can combine two modal verbs in the same sentence, saying something like “he might could do that, but he shouldn’t oughtta” (a construction which is quite impossible for most other speakers of ‘English’).

A particularly distressing parallel between biological species and languages that has attracted a good deal of attention in recent years is the fact that both are disappearing at alarming rates as a consequence of developments in modern society. A language is inexorably moribund when it ceases to be learned by children, and linguists estimate that as many as 50% or even 90% of the languages currently spoken, however we choose to enumerate these, will be in this situation by the end of the present century. This is a rate that is much greater than anything we find in the extinctions taking place in the plant and animal worlds. The situations are not exactly parallel, but the loss of diversity in both domains is deplorable and something that will leave our world much poorer if allowed to proceed unchecked.

Languages and biological species are much more nearly comparable concepts than their obviously different bases might suggest. Why this should be so is quite unclear. Perhaps it shows us something very profound about the categorizing faculty of the human mind, but in any case it surely contributes to the sense that human language is something deeply rooted in our biology.

Stephen R. Anderson is Professor of Linguistics at Yale University. His most recent book, Languages: A Very Short Introduction was published this month.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 5, 2012

“The picture was made for the apple”

Americans do not question the revolutionary character of the Declaration of Independence. Far fewer view the US Constitution in such terms. It is easy to identify many reasons for this duality. The Declaration speaks in the cadences of Shakespeare and the King James Bible. By comparison, the Constitution is a mechanics manual or lawyers brief. The Declaration offers a concise statement of first principles and goals; it created a nation, and it called for noble sacrifice for the sake of liberty. The Constitution is more procedural. Except for the Preamble, it has few memorable phrases and no peroration to greatness. Too often we see the Constitution as ending the Revolution, when in fact its adoption made it possible to continue the radical impulses that had stirred men and women in 1776.

Abraham Lincoln considered both documents to be the living legacy of the American Revolution. These foundational charters were inextricably linked sources of the nation’s freedom. The Declaration’s principle of equality, he wrote in 1861, was “the apple of gold,” and the Constitution — and the Union it created — was “the picture of silver.” The Constitution was made “not to conceal or destroy the apple but to adorn and preserve it. The picture was made for the apple — not the apple for the picture.” What he did not say but what later generations proven by their actions was that the Constitution was a flexible framework for government because it embodied revolutionary principles, chief among them the radical idea that men and women could rule themselves.

“We the People,” the Constitution’s opening phrase, was no literary conceit. Rather, it represented a fundamental re-scripting of assumptions about government that was embedded in the revolutionary generation’s invention of popular sovereignty, a conception of the people as both rulers and ruled who, in John Jay’s words, “had none to govern but themselves.” This concept allowed power to be divided and thus limited, constraints that were problematic if not impossible when the people only consented to government. Over two centuries, this notion of popular sovereignty has been central to the development of a more democratic and egalitarian nation, as once marginalized and excluded groups demanded to be counted among the people who ruled themselves. But as often happens with revolutionary legacies, there is a counter-narrative to this progressive story. The inventions of popular sovereignty also has produced great mischief. It has offered a veneer of legitimacy to a variety of “isms” — racism, nativism, separatism, and the like — that acted to deny liberty rather than advance it.

The Constitution also established a new but untested and controversial theory about the relationship between power and liberty, the two lodestars of the revolutionary struggle. Early republicanism treated power and liberty as implacable foes, and both the first state constitutions and Articles of Confederation sharply limited governmental power generally as the best way to protect liberty. They likewise elevated the legislature, the people’s representatives, over the executive in distributing power within government. But the emergence of majoritarian tyranny, as the French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville later labeled it, spurred a re-thinking of the calculus of liberty and power. The Constitution proposed a different relationship, one in which governmental power became the friend and promoter of liberty, a result made possible by dividing governmental power among the various branches of the central government and between the national government and the states. And because not all Americans were satisfied with this redefinition of republican ideas, a Bill of Rights placed some rights beyond the power of government. One consequence was that the Constitution came to embody a central tension of the revolutionary thought — government as the friend of liberty, government as the foe of liberty — that has shaped our constitutional politics from the early controversy over the necessary and proper clause to debates over the 2010 heath care reform act.

Above all, the framers of the Constitution aimed to save the great experiment in liberty that had begun in 1776. No one imagined that it had solved the problems that confronted the new nation. Instead, it offered a framework to allow future generations to work out what revolutionary ideas meant for their own circumstances. The founders invited us to struggle over constitutional meaning and in the process to renew the nation’s revolutionary heritage. Ultimately they trusted that we, the people, would answer for ourselves how best to protect and extend Declaration’s promise of liberty and equality.

David J. Bodenhamer is Founder and Executive Director of The Polis Center, Professor of History, and Adjunct Professor of Informatics at Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis. He is the author or editor of several books on American legal and constitutional history, including The Revolutionary Constitution, Fair Trial: Rights of the Accused in American History, and is co-editor of the International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

5 July 1962: Algerian Independence

On 5 July 1962, Algeria achieved independence from France after an eight-year-long war — one of the longest and bloodiest episodes in the whole decolonisation process. An undeclared war in the sense there was no formal beginning of hostilities, the intensity of this violence is partly explained by the fact that Algeria (invaded in 1830) was an integral part of France, but also by the presence of European settlers who in 1954, numbered one million as against the nine million Arabo-Berber population. Drawn from Italy, Malta and Spain, as well as France, these white colonials were for the most part very poor and this poverty lay at the root of their virulent racism. Feeling socially insecure, they found solace in prejudices that became the basis of a collective ‘we’ and ‘they.’ Bigotry towards the indigenous populations, whether they be Arab, Berber or Jew, peppered the daily conversation of Europeans. Even more crucially, it became the basis of a system that treated the Arabo-Berber population as second class citizens who had to be permanently shut out of colonial Algeria.

This racial inequality was the basic cause of the Algerian War, which began on 1 November 1954 when the Front de Libération National (FLN) launched a series of attacks throughout the country. The ensuing conflict produced enormous tensions that brought down four governments, ended the Fourth Republic in 1958, and mired the French Army in accusations of torture and mass summary executions. However, successive French governments could not countenance withdrawal because Algeria was seen to be the lynch-pin of the French-ruled bloc that stretched from Paris down to Brazzaville in the French Congo. Internationally this bloc — claimed by left-centre politicians like François Mitterrand and Guy Mollet — would allow France to stand up to the Soviet Union as well as British and US imperialisms.

Unable to win in Algeria, the Fourth Republic imploded in May 1958 and led to the return of the World War Two Resistance leader, Charles de Gaulle. Initially de Gaulle continued with the policy of repression and reform. Yet, by 1961 he had come to the conclusion that independence was inevitable. For him the depth of Algerian nationalism was too strong, but his decision was also a cold economic calculation. Simply speaking, Algeria was a drain of French resources. As he told a press conference on 11 April 1961 in Paris: “Algeria is costing us, this is the least one can say, much more than it brings into us.”

Thereafter the French government entered into a series of tortuous negotiations, further complicated by rebellions by dissident French army officers, who felt betrayed by de Gaulle. However, a peace agreement was brokered in March 1962 and on 1 July 1962 Algeria went to the polls with 91.5% saying ‘yes’ to independence. By this point most of the Europeans had left for France (one of the biggest population transfers of the twentieth century). On Tuesday 3 July at 10:30 a.m., de Gaulle officially recognised Algerian independence, and during the hours that followed other countries followed suit, including the USA and Great Britain. The Algerian nation state was a diplomatic reality and the Algerian Provisional Government proclaimed Thursday 5 July to be Algeria’s national Independence Day, exactly 132 years after the original French invasion.

Internationally, the end of the Algerian War was a major moment in global affairs. This significance was signalled by countless editorials across the globe marking the event, ranging from The Times and the Daily Telegraph in Britain, and The New York Times in the USA, to Il Popolo in Italy and Die Welt in West Germany. Algerian independence was history with a capital ‘H’ at the time, but it has remained so because the Algeria crisis was a pivotal event in the formal ending of European Empires.

Martin Evans is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Portsmouth. He is the author of Algeria: France’s Undeclared War, Memory of Resistance: French Opposition to the Algerian War (1997), co-author (with Emmanuel Godin) of France 1815 to 2003 (2004), and co-author (with John Phillips) of Algeria: Anger of the Dispossessed (2007). In 2008 Memory of Resistance was translated into French and serialised in the Algerian press. He has written for the Independent, the Times Higher Education Supplement, BBC History Magazine and the Guardian, and is a regular contributor to History Today. In 2007-08 he was a Leverhulme Senior Research Fellow at the British Academy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers