Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1040

July 19, 2012

The water problem

The dirty little secret about water in the West is that water conservation is a hoax.

Trip to New Mexico, D. & R.G. R.R., U.S.A. 1870?-1900? Source: NYPL Labs Stereogranimator

When we conserve water by using less, we don’t save it for the health of the watershed or put it aside in any way; we simply make it available for someone else to consume, if not today, then tomorrow in the next strip mall or housing development down the road.In this respect, water conservation is good for the short-term economy — it keeps the real estate industry, the building trades, and much else going — but it doesn’t work out well for the resilience of our communities because it leads to “hardened demand,” which means that the water we use is needed all the time, no matter what.

This is the big irony of water management: in dry times, waste is our friend. When water is used wastefully, it is easy to deal with drought. Everybody stops watering the lawn, washing the car, and making puddles of any kind. Current demand drops like a stone.

But when everybody conserves — puts in low-flow toilets, xeriscapes the yard, and does all that other good stuff in both public and private sectors — the demand for water “hardens.” The uses that remain are essential; you can’t turn them of, and sometimes you can barely pare them back.

Conservation enables a community with fixed water resources to continue growing. But the more it grows on the strength of conservation, the more vulnerable it becomes to drought. When dry times inevitably come, there’s no flex in the system.

One logical response is to limit growth, but I don’t know of a single community that has done this without lamentable consequences. Consider Bolinas, California. Because of limited water supplies, Bolinas put a cap on the number of water meters its utility would support. Early in 2010, one of those meters changed hands for a cool $300,000. The Bolinas example illustrates another demand phenomenon. Limit supply, and the price of a needed commodity soars. Outside of small, boutique communities like Bolinas, a major spike in the cost of access to water would be socially and politically unacceptable.

Environmentalists might respond by saying, “Communities will have to handle shortages the best they can. In the meantime, we enviros need to secure in-stream flows for rivers and place those water rights in a blast-proof public trust. That way we can prevent the collapse of the linear oases that sustain the non-human environment.”

The trouble is, anything can be raided. There is no such thing as a blast-proof public trust, not if whole cities face death by thirst. And that kind of threat may not be far away.

Most climate change models forecast declining stream flow and reduced water availability in the Southwest on the order of 10 percent to 30 percent, as well as in other areas of the West. Higher temperatures and faster evaporation guarantee that the region will become more arid even if precipitation stays constant. (But don’t bet on precipitation remaining “normal.”)

Our utilities tell us that conservation is the answer to future water scarcity. I think they tell us that because they don’t have another answer.

In a pinch, utilities will also talk about “augmentation” — desalination, interbasin transfers, and other big-ticket, high-tech lines of attack — which might keep the water-supply hamster wheel spinning for another generation or so, at considerable fiscal and environmental cost. But none of these strategies will stop the wheel of increasing need and hardening demand from spinning, or even slow it down.

And no one dares mention that, over the long term, water conservation paints us into a tighter and tighter corner. Optimists say that conservation at least buys us time by putting off the day of reckoning. This may be true, but what are we doing with the time we’ve bought?

Another argument holds that, when push comes to shove, we can always squeeze more water out of agriculture. Some water districts have already done this, partly by financing agricultural efficiencies, partly by moving the water out and dewatering valleys. Even this strategy has limits, however, and it raises other troubling issues, such as: How do we feed ourselves?

In the end we are back where we started, lacking the ability to set limits and live within them. I don’t have an answer to this conundrum, but it seems to me the sooner people start talking about it openly, the better our chances of solving it.

Meanwhile, our rivers, cities, and farms remain in peril.

William deBuys is the author of seven books, including the latest A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest. He is a contributor to Writers on the Range, an opinion syndicate of High Country News. This article originally appeared in High Country News.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Not a Euphemism

I write about euphemisms for Visual Thesaurus every month, and I love collecting and discussing evasions, dodges, lies, and straight-up malarkey, such as the terms sea kitten and strategic dynamism effort.

However, I am also a fan of words and phrases in the “not a euphemism” category: especially the phrase not a euphemism itself, which is used in speech and writing to both downplay and heighten the filthiness of dirty-sounding phrases.

This recent tweet by Steve Niles is a textbook example:

#bbpBox_222732694948282368 a { text-decoration:none; color:#2FC2EF; }#bbpBox_222732694948282368 a:hover { text-decoration:underline; }It's supposed to hit 106°. Already 90° at 10am. I think the tortoises stay inside today. No, that's not a euphemism.

July 10, 2012 12:43 pm via web

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

Steve Niles

July 10, 2012 12:43 pm via web

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

Steve NilesWhen a writer stumbles on a phrase that sounds sexual or scatological, saying it’s not a euphemism serves two purposes. First, it tells you to get your mind out of the gutter and take the writer literally. Additionally, the writer shows pride in making a joke and gives you permission to take the phrase as deep into the mental gutter as you like. Not a euphemism lets the writer have it both ways (no, that’s not a euphemism).

I searched my own tweets and found I’ve used the phrase a few times myself, always when something I ate sounded more illicit than nutritious:

This Korean barbecue is so good I don’t mind it’s not a euphemism.

I just had a Vietnamese sandwich. No, that’s not a euphemism.

I gave my friend a Chicago hot dog this week. No, that’s not a euphemism.

As far as I can tell, not a euphemism is used just about everywhere, but a selection of July tweets should show its usefulness and silliness. I hope you enjoy these phrases, even if you’ve never had rats in your bra or had something flower on your trellis.

View the story “”Not a Euphemism”" on Storify

Mark Peters is a lexicographer, humorist, rabid tweeter, language columnist for Visual Thesaurus, and the blogger behind The Rosa Parks of Blogs and The Pancake Proverbs.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only dictionary, language, lexicography, and word articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

July 18, 2012

Still in the fishbowl (2): ‘Mackerel’

Not that I can say anything quotable on the subject of the mackerel, but people keep writing about it and the attempts to understand how this fish got its name are so interesting that the story may be worth telling. Only one thing seems certain. Mackerel first appeared in a West-European text, in the French form makerels (plural) about 1140 (which means that it was known much earlier), and no one doubts that the English borrowed their word from Old or Anglo-French. From France it spread to other lands, sometimes through an intermediary. The question is why the French called the mackerel this.

Stream of mackerel 2008. Photo by Ed Bierman. Creative Commons License.

The fish has been known forever. The Greeks called it skombros and the Romans scomber, whence the scientific name Scomber scomber, sounding like a parody of Nabokov’s parody. (Nabokov, in introducing Humbert Humbert, was naturally aware of the allusion to this type of terminology.) The origin of the Greek word is unknown. The once popular idea that it means “red” has been abandoned long since, but Russian skumbriia and a few of its “relatives” remind us of the ancient word. Whoever coined mackerel was not influenced by the Mediterranean tradition.

The oldest suggestion about the word’s origin points to Latin macula “spot,” a noun familiar to English speakers from (im)maculate. Macula also meant “mesh of a net”; from this sense, via Old French, we have mail “armor.” The fish in question is indeed spotted and very probably that’s all there is to say about its name, but scholars tend to walk devious ways. Modern French has two words spelled and pronounced alike: maquereau “mackerel” and maquereau “pimp” or “matchmaker,” or (euphemistically) “broker.” In the middle of the nineteenth century, Carl A. F. Mahn advanced a bold hypothesis that happened to have a long life. However, before summarizing it, some information should be given about Mahn, an etymologist whose name is inextricably connected with that of Noah Webster.

The first edition of Webster’s dictionary appeared in 1828. Although its publication provoked fierce attacks, the book withstood them and became deservedly famous on both sides of the Atlantic. Unfortunately, it contained many absurd etymologies, which as time went on became a real embarrassment. New philology arose in Germany, but both England and the United States lagged sadly behind. Decades passed before people like Henry Sweet and William Dwight Whitney could speak like equals with their German peers and gain their recognition. Skeat belonged to the same generation. When in the eighteen-sixties the decision was made to overhaul Webster’s derivations, no one in the English speaking world could be entrusted with this task. Even Germany lacked a first-rate expert in the history of English.

Twenty years later the situation became different, but the publishers did not want to wait. The choice fell on Mahn (1802-1887), a German scholar who specialized in Romance historical linguistics and made his living as a foreign language teacher in Berlin. In retrospect, his readiness to undertake such a task looks like absolute madness. Yet he did the work so well that the 1864 edition of Webster’s dictionary is usually referred to as Webster-Mahn. Even Skeat, who expressed unconcealed disdain for his contemporaries’ dabbling in etymology, treated Mahn with a modicum of respect and sometimes agreed with him. Despite Mahn’s great achievement, he is almost forgotten. The two obituaries I have read list his publications and say almost nothing about his life. The same holds for the entries in several German dictionaries of biography. If some of our readers happen to know more about him, references will be most welcome. I cannot even say whether he went to America to work on etymologies or corresponded with his colleagues by mail. He certainly deserves greater visibility.

Long before his American adventure, Mahn offered a new etymology of mackerel; reproduced in the dictionary, it became widely known. He mentioned the popular tradition in France that the mackerel in spring follows the female shads, which are called vierges (or maids) and leads them to their mates. Thus, maquereau “mackerel” and maquereau “matchmaker; broker; pimp” turned out to be the same word. Skeat, in the first edition of his etymological dictionary, “made bold to reject” this derivation because “it is clear,” as he said, “that the story arose out of the coincidence of the name, and that the name was not derived from the story.” He was probably right, except that nothing is “clear” here.

If the superstition is old, it could have given rise to the fish name, but its age is beyond reconstruction. The fact that it was first recorded in the nineteenth century does not disprove its antiquity; not everything we call folklore has attested medieval roots. It is rather the fanciful nature of the story that makes it almost impossible to believe. In the post on herring, I referred to the linguist who believes that herring meant the sun with rays all around its “face.” He also has full trust in the brokerage hypothesis. Maquereau “pimp” goes back to Dutch makelaar or its Low (that is, northern) German cognate, literally “maker.” Some older etymologists pointed out that in Roman comedies matchmakers usually wore motley clothes, a circumstance that could, as they thought, bring forth an association between the fish with its spots and the actor’s apparel.

Then there are two French homonyms: mâcher “chew” and mâcher “crush, bruise,” considered to be unrelated. Those who trace French maquereau to mâcher “bruise” come to the same conclusion as those who begin with Latin macula. Allegedly, the spots (blotches) on the fish look like bruises. Given macula, we hardly need a competitor (mâcher) to clinch the etymology. (This is, of course, not a decisive argument, for Occam’s razor is not always a dependable tool in etymology, whether we are dealing with fish or any other subject.) Also, this verb surfaced considerably later than the fish name in Old French, while in the south of France (where it turned up at an earlier date,) the fish isn’t called maquereau. In Provence, its name was vairat. However, as with folklore, dates give an imperfect idea of when a word appeared in the language. Fish names had low frequency in old texts (glosses, treatises on animals, and recipes). For example, from the Old English period only twenty-five fish names have come down to us. If an exhaustive encyclopedia of ichthyology from the Middle Ages had existed, it would probably have been written in Latin.

Die Forelle by Franz Schubert, 1821. Source: Library of Congress.

Thus, as with herring, no final results reward our search, though once again we can say that certain suggestions are more realistic than the others. The French homonyms — maquereau “match maker” and maquereau “mackerel” — seem to be different words. Since they are indistinguishable in pronunciation, a legend must have arisen that this fish performs certain matrimonial services. Belief in such a strange phenomenon could result in the coinage of the fish name, but it most likely did not. Roman actors fade out of the picture along with brokering mackerels. With regard to spots, Latin macula (or simply maca) seems to be a more plausible source of Old French makerel than mâcher “bruise.” Vairat, mentioned above, apparently refers to the mackerel’s “variegated” appearance. Even those who don’t know German may have heard the German word Forelle “trout” from Schubert’s song. Forelle, as its etymology shows, also meant “spotted.” Examples of “spotted” fish abound. In a recent paper, William Sayers didn’t reject the origin of mackerel from a word for “spot” but suggested a Basque source of the Old French word. This is of course possible. As usual in such cases, solid evidence is wanting.Unlike -ing in herring, -rel in mackerel poses no problems. It is a diminutive or pejorative suffix, the same that occurs in pickerel (literally “little pike”), petrel (possibly from Peter), cockerel, mongrel, scoundrel, wastrel, and unexpectedly, doggerel, among others.

Fish are hard to catch. The origin of their names is often even more evasive. The result depends entirely on one’s fishing luck.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The Ties That Bind Ancient and Modern Sports

What do we share with the Ancient World? Thankfully, not too much. But we do share a love of sports and strangely enough we still approach sports in the same way. We complain about commercialization, but sponsors and marketing have existed since games began (although we’ve moved on from statues to cereal). And for the greatest games, the Olympics, we seek the best: the peak of human physical achievement and unique moments in time as records shatter.

As the world awaits the London 2012 Summer Olympics, we spoke with David Potter, author of The Victor’s Crown: A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium, about how sports unites us with our past.

Click here to view the embedded video.

David Potter is Francis W. Kelsey Collegiate Professor of Greek and Roman History and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Greek and Latin in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author of The Victor’s Crown: A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium, Ancient Rome: A New History and Emperors of Rome, and two forthcoming OUP titles, Constantine the Emperor and Theodora. Read his previous blog posts: “The Money Games” and “Sports fanaticism: Present and past.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Are One Direction redefining masculinity?

With One Direction topping the US music chart, and David Beckham to be the first man featured on Elle’s front cover, images of men have changed dramatically in recent years. The softening of masculinity is a good thing, and shows no sign of abating.

Born in the 1980s, I grew up during a period where the most macho of masculinities were esteemed. From Rambo to Rocky, Die Hard to Lethal Weapon, men were portrayed as all-action heroes whom neither bullets nor armies could vanquish. Professional wrestlers appeared almost understated in their gendered performances compared to the display of masculine bravado found in movies and revered in the wider culture.

This machismo was accompanied by a pervasive and enveloping homophobia. The rise of the so-called moral majority and the AIDS epidemic meant that homosexuality was incredibly stigmatized in the 1980s and 1990s. As a result, men went to great lengths to avoid being socially perceived as gay. The most effective way of doing this was to deploy homophobia. Accordingly, masculinity became not just a show of physical strength and emotional stoicism, but also of anti-gay animus. It is for this reason that leading sociologist Michael Kimmel argued that masculinity was effectively a performance of homophobia.

And yet things have changed beyond recognition. The British boy band One Direction, who recently topped the U.S. charts, are a pop sensation who have eschewed such forms of masculinity. These young men’s gentle tactility and open displays of emotion are part of what has made them so famous. As a Sunday Times journalist who interviewed them wrote, “They tousled each other’s hair and jostled and caressed one another like a bunch of frolicking puppies.” What’s more, homophobia couldn’t be further from their lips, as they thank their army of gay fans and perform at gay venues such as London’s G-A-Y.

One Direction are just one example of a vast number of famous men to embody this softer, more inclusive masculinity. Yet crucially, such behaviors are not limited to celebrity elites. Rather, these men both model and mirror the gendered behaviors of today’s youth. When researching for my latest book, I found that British youth are redefining masculinity for their generation. Undertaking ethnographies of three British high schools and hanging out with the male students, it was evident that the homophobia, violence and emotional illiteracy of the past have vanished for these young men. Toxic behaviors have been replaced with hugging, cuddling, and loving.

Perhaps the most startling change is the soft touch between boys. One day in an assembly, for example, I observed a popular student Steve seated behind Liam. Unsolicited, Steve leant forward and gave Liam a back rub. Liam turned around, smiling, and said, “That’s great, just go a bit lower.” Less popular boys did this too. Ben and Eli were standing in a corner of the common room, chatting. They were casually holding hands, with their fingers laced together. Ben then moved his head towards Eli’s ear, speaking to him for about a minute, his mouth so close that he could have been kissing Eli. If students in the busy common room noticed, they didn’t care. And these behaviors were not extraordinary—they are how young guys demonstrate their friendship and express their emotions.

It is my argument that the changes in behavior so evident among these young men are the result of a significant change in attitudes toward homosexuality. Put simply, young men are rejecting the homophobia of their fathers and are embracing gay rights instead. In my research, this was evident from the inclusion of gay peers, the explicit condemnation of homophobia and the support of gay marriage. While homophobic language was once rife in schools, these boys were complaining that they didn’t know any openly gay teachers.

It is likely that many of these changes are more advanced in the UK than in America. Yet progressive attitudes are undoubtedly developing in the United States as well. Much of this change has been documented by Professor Eric Anderson, and quantitative research demonstrates a similar story. For example, a recent survey of over 200,000 first time college undergraduates across 270 colleges in the United States found that 64.1% of male freshman support same-sex marriage; a statistic more startling when one considers that this does not account for those supporting civil partnerships. American culture might not have its own One Direction, for example, but it has been quick to embrace the British band.

These changes are profound and require us to rethink how we talk about masculinity and sexualities. We need a more holistic approach to sex education, where we recognize young people as mature enough to discuss issues of homosexuality in intelligent and informed ways. The social sciences tell us a great deal about sex and sexuality and we should ensure that this knowledge is included so that the more inclusive attitudes of young people can be nurtured and flourish.

This article originally appeared on Psychology Today’s Men 2.0.

Mark McCormack is a qualitative sociologist at Brunel University in England. His research focuses on the changing nature of masculinities among British youth. In this book, he examines how decreased homophobia has positively influenced the way in which young men bond emotionally and interact in school settings.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 17, 2012

After a “Referendum” Election

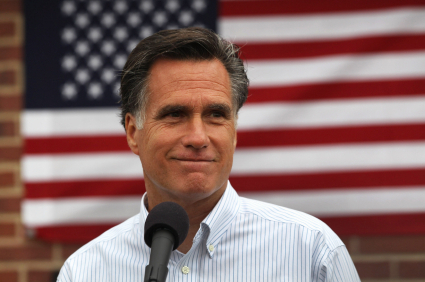

The 2012 presidential election has assumed the form of a popular referendum on Barack Obama’s four years in the White House. Put simply, neither the president nor his Republican opponent Mitt Romney has said much about what he would do if elected. Voters instead are being asked to render their verdict on the past. One consequence is that the winner, whether Obama or Romney, won’t be able to invoke a mandate for policy initiatives over the next four years.

President Barack Obama addresses Indiana residents during a town halll style meeting at Concord High School February 9, 2009 in Elkhart, Indiana.

At the moment, the two campaigns are pursuing very similar strategies — each tries to inspire the partisan base without antagonizing centrist, independent minded voters. There is a good deal of posturing to please those toward the extremes. Thus Republicans in the House weigh whether to cast a meaningless vote to repeal Obama’s signature health care measure, while the president declares himself in favoring of ending the Bush tax cuts for those earning over $250,000. For all the staging and fanfare, neither proposal stands the slightest chance of approval before or even after the election.

On the campaign trail, the president spends a good deal of time defending his record and blaming the Republicans for obstructing his efforts to do more. Since the 2010 mid-term election returned control of the House to the GOP, the country has been in a policy holding pattern, legislation stacked up like airliners waiting for their landing slots while the runways are solidly fogged in by campaign politics. The president makes showpiece announcements such as the new tax proposal to dramatize the contrast between his dedication to fairness for ordinary Americans and the Republicans’ solicitude for the wealthy. As to what Obama might actually do in a second term, however, we can really only guess and speculate. If he wins, it will be a triumph that sends no coherent signal, and he will struggle to fashion an agenda to which the Republicans must defer. (The GOP will retain control of the House; neither party will come close to the sixty votes needed in the Senate to move legislation.)

Romney seems ready to stake everything on voters’ disappointment with the halting economic recovery. At every turn, he declares himself to be the “not Obama.” Rather than identify a clear economic prescription, he has offered up his own personal history as a successful business leader, suggesting that his record alone should suffice to satisfy the electorate. For the Republican base, he endorses the general outlines of the Ryan budget, with its commitment to deeper federal tax cuts, though not some of the less popular particulars (such as the Medicare overhaul that would radically transform the program). But on the campaign trail he prefers to stick to the broader theme that the Obama stimulus approach has failed and the nation needs to turn in a different direction. In effect, he asks the electorate to change drivers without being very specific about the destination or the route.

As an electoral strategy, Romney’s approach may work. He has banked his campaign on the expectation that the economy would not recover sufficiently before the 2012 election to rescue the president. History is on Romney’s side; recent presidents facing high unemployment have fared poorly in their reelection bids. Obama’s approval rating, very much a reflection of how the public perceives his handling of the economy, hovers below fifty percent, and he fares especially poorly when respondents are asked about his handling of the economy. The poor numbers for new jobs in the past several months do not auger well for an incumbent.

But in terms of establishing a basis for governing, the former Massachusetts governor will find himself without any kind of a mandate for action if he wins. Running as the “not Obama” would remove from the table a few options that no Republican would be likely to support, such as another spending-oriented stimulus program. But a referendum election on a predecessor’s policy establishes no foundation for positive steps.

Unless the campaigns change their focus and adopt a forward-looking orientation, then, voters in November will declare no more than their level of satisfaction with where the country stands four years after its greatest financial collapse in two generations. The winner will earn no warrant to address the persistent aftereffects of the crisis. Nor will he be able to claim the people’s endorsement as he wrestles with challenges both expected (such as the draconian $1.2 trillion budget sequester) and unforeseen.

Americans look to elections for clarity, as a mechanism for sending unambiguous signals to their elected leaders. But leaders need to play their part, too. In 2012, their strategies, based on posturing and caution, point to an election with no decisive message.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The stigma of mental illness

When asked, many people with mental illness will say that the consequences of the stigma of mental illness are worse than the illness itself. Stigmatization affects the position that people have in their community, their employment, their housing, the size and functioning of their social network. An episode of mental illness which is well treated may leave no trace in the mental state or functional capacity of the individual. Yet the stigma related to the disease will last for the rest of a person’s life and even often have repercussions for descendants of the person who experienced a stigmatizing illness.

Despite the solid evidence about the nefarious consequences of stigmatization in all walks of life and the existence of effective ways of fighting it health authorities in most parts of the world invest very little or nothing into the fight against stigma. The remarkable advances of our knowledge about fighting stigma are neither properly taught in schools of health personnel nor used as essential evidence in planning health care for the future. Occasional campaigns against stigma in some countries are seen as being sufficient to deal with the problem and serve as a stand-in for the inclusion of anti-stigma activities of proven effectiveness into the routine of health services.

Despite the solid evidence about the nefarious consequences of stigmatization in all walks of life and the existence of effective ways of fighting it health authorities in most parts of the world invest very little or nothing into the fight against stigma. The remarkable advances of our knowledge about fighting stigma are neither properly taught in schools of health personnel nor used as essential evidence in planning health care for the future. Occasional campaigns against stigma in some countries are seen as being sufficient to deal with the problem and serve as a stand-in for the inclusion of anti-stigma activities of proven effectiveness into the routine of health services.

Much has been learnt about the effects of anti-stigma interventions in recent years and it is clear that what is recommended today differs from what has been done in the past. Thus we now know that:

Work against stigma focused on well-defined groups (judges, policemen, doctors and teachers for example) is considerably more effective than short-lasting nationwide campaigns involving the media.

Opportunities for direct contact with people who have or had a mental illness can reduce stigma and prejudice much better than any other form of education about mental illness, e.g. in schools.

The involvement of people with mental illness when choosing targets for anti-stigma work is much more useful than the selection of targets on the basis of research, e.g. on attitudes.

Health services can be a powerful source of stigma and should be tackled first in anti-stigma programs.

A useful tip for anyone interested in fighting stigma is to examine one’s own behavior and attitudes, which are often in strict contrast to what we are teaching and promoting. Even words that we use — saying a schizophrenic instead of saying a person with schizophrenia — can hurt and contribute to stigmatization but there are other things that we should learn to do better if we are keen to fight stigma.

If health services intended to help people with mental illness are to achieve their goals they must accept that the stigma of mental illness is today the chief obstacle to their success and that they must invest a good part of their resources into its prevention or reduction.

Professor Norman Sartorius, MD, PhD, FRCPsych is a co-author of Paradigms Lost: Fighting Stigma and the Lessons Learned. He is President of Association for the improvement of mental health programmes (MH), a previous Director of the World Health Organization’s Mental Health Program, and past President of the World Psychiatric Association and the European Psychiatric Associations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicines articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The Loudness War

In my last blog posting I wrote in defense of Auto-Tune. So if it’s not Auto-Tune, then what is wrong with pop? To the extent that technological capabilities have created a problem, it’s the loudness war that created it.

A brick wall limiter is the tool that makes digital audio files loud and in the process it can crush the dynamics and render the music lifeless. The effect is actually very powerful. When first hearing a piece of music with heavy brick wall limiting one is likely to say: “Wow!” It is powerful — heavy on the “wow factor” — but it’s not musical; it’s more like an assault. You may be impressed but you may not want to hear the music again or at least not very often.

Brick wall limiting is made possible by digital technology but the desire to make music louder has been around for much longer. The fact is (for complicated reasons and only up to a point) that louder always sounds better. Artists and record labels used to compete to make their vinyl LP’s louder than others. But with vinyl there is a technological limitation; if you make an LP too loud it skips, the needle can’t track the grooves. With digital music files we can push more and more of the sound up against the “wall” (digital zero, which is as loud as it can go). As we do so the music sounds louder and louder, and less and less musical.

Diagram showing the difference between Limiting, Hard Clipping and Soft Clipping by Iainf. Creative Commons License.

Metallica’s 2008 release Death Magnetic caused a furor because of the degree of brick wall limiting and over 13,000 fans signed a petition asking that the CD be remastered. Nonetheless, the album sold very well; “louder” does get your attention. Despite ongoing complaints from consumers and attempts to educate the public by concerned mastering engineers, there seems to be very little impetus to counter the continued trend toward massive brick wall limiting.

On a recent CD that I co-produced with the artist Bonnie Hayes, we put the following disclaimer on the jacket: “This record was mastered to sound good, not to be loud. It is up to you to turn it up!” Of course, I did apply some brick wall limiting, I just didn’t crush the life out of the music and you can play a record as loud as you want. But if a song with no brick wall limiting is in a playlist on an iPod, that recording will sound wimpy compared to the others.

So what’s the solution? Some people are saying that new consumer trends like Spotify will end the loudness war because the service compensates for variations in volume and removes the advantages of heavy brick wall limiting. It’s not clear if that’s true and services like Spotify aren’t yet dominant enough to change practices. In the meantime, popular music continues its losing battle with video games and other entertainments for the attention of the public. Even the mainstream press has taken note of the Loudness Wars, but no peace agreement is in sight.

Steve Savage is an expert in the art of digital audio technology and has been the primary engineer on seven records that received Grammy nominations (including Robert Cray, John Hammond Jr., The Gospel Hummingbirds and Elvin Bishop). He also teaches musicology at San Francisco State University. Savage holds a Ph.D. in music and has two current books that frame his work as a practitioner and as a researcher. The Art of Digital Audio Recording: A Practical Guide for Home and Studio from Oxford University Press is the result of 10 years of teaching music production and 20 years of making records. Bytes & Backbeats: Repurposing Music in the Digital Age from The University of Michigan Press uses his personal recording experiences to comment on the evolution of music in the computer age. Read Steve’s previous blog posts: “Why Auto-Tune is not ruining music” and “Is Lady Gaga an artist?”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 16, 2012

The Myths, Realities, and Futures of Child Soldiers

Imagine a child soldier. You probably think of a poor African boy, no older than ten, forced by ruthless commanders to take drugs and fire guns whenever and wherever directed. And this image completely contradicts the reality for the vast majority of child soldiers.

Washington and Lee School of Law interviewed Professor Mark Drumbl, author of Reimagining Child Soldiers in International Law and Policy, and discovered the myths and realities of child soldiering. What’s more, this distorted images inform the place of a child soldier in local and international justice systems — to the detriment of victims, communities, and the child soldiers themselves.

The Image and the Reality of Child Soldiers

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Facts About Child Soldiers

Click here to view the embedded video.

What Happens to Child Soldiers After Conflict

Click here to view the embedded video.

Mark A. Drumbl is the author of Reimagining Child Soldiers in International Law and Policy. He is the Class of 1975 Alumni Professor at Washington & Lee University, School of Law, where he also serves as Director of its Transnational Law Institute. He has held visiting appointments with a number of law faculties, including Oxford, Paris II (Pantheon-Assas), Trinity College-Dublin, Melbourne, and Ottawa. Drumbl has lectured and published extensively on public international law, international criminal law, and transitional justice. His first book Atrocity, Punishment, and International Law (CUP, 2007) has been widely reviewed and critically acclaimed. He initially became interested in international criminal justice through his work in the Rwandan genocide jails. Drumbl holds degrees in law and politics from McGill University, University of Toronto, and Columbia University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Replacing ILL with temporary leases of ebooks

One of the things that I love about being a librarian is that as a profession, we work together to share ideas and resources. Perhaps the most remarkable example of this collaborative spirit is interlibrary loan (ILL). We send each other books, DVDs, CDs, articles — whatever we can reasonably share. And we do this at considerable expense to our own institutions because we see a mutual benefit. When we lend something, we know that other libraries will lend things to us, for our students and faculty to use. ILL is amazing, a wonderful service, but as I’ve argued before, it doesn’t make much sense in a world of digital collections.

With physical objects (typically books), ILL is often the only way for my library to provide our users with the research material they need. For books that aren’t in our collection and are often out of print, the only place we can go is to another library. But ILL is a time-consuming and expensive practice. Consider the steps:

A student identifies a book that she needs for a research project.

She searches her library catalog and discovers that it’s not available locally.

She fills out a web form to request that her ILL department borrow that book from some other library.

The ILL staff do some searching, find another library that owns that book, and request it.

The other library receives that request.

Staff at the other library identify a location for that book, pull it from the shelf, check it out, pack it up, and mail it to my library.

Staff at the borrowing library unpack the book, check it in to the ILL system, and generate a notice to the student that her book has arrived.

The student comes to the library and checks the book out.

When she is done, she returns it.

The local ILL staff check it back in, pack it back up, and mail it.

The other library receives it.

Staff at that library unpack it, check it back in, and return it to the shelf.

All of those steps have costs involved — some of which are sunk into salary. In a recent study, Lars Leon and Nancy Kress estimated that it costs a library $9.62 on average to borrow a book and $3.93 to lend a book (and every transaction involves both sets of costs).

Imagine the same set of steps for an e-book:

A student identifies an e-book that she needs for a research project.

She searches her library catalog and discovers that it’s not available locally.

She fills out a web form to request that her ILL department borrow that e-book from some other library.

The ILL staff do some searching, find another library that owns that e-book, and request it.

The other library receives that request.

Staff at the other library check to make sure they have the right to loan that e-book.

They either send a PDF or a link (probably turning off access to the e-book locally).

Staff at the borrowing library receive the PDF or the URL, check it in to the ILL system, and generate a notice to the student that her e-book has arrived.

The student logs in to access the e-book.

There are fewer steps, but this is still an expensive and inefficient process, particularly when you consider that the student has to wait for something that could be available immediately in digital format.

Librarians need to stop trying to recreate ILL for e-books. Instead, we should work with publishers to develop a model to lease e-books temporarily. Imagine these steps:

A student identifies an e-book that she needs for a research project.

She searches her library catalog and discovers a link to a version that can be leased by the library temporarily.

She clicks the link to that e-book and begins reading, while behind the scenes her library is billed for that use.

If we could do this for less than the cost of a typical ILL transaction, we could save money and time, getting that book to the student instantly. The major e-book aggregators (EBL, ebrary, MyiLibrary) for academic libraries already do this, but they only have a small portion of the books we need. Publishers need to collaborate with libraries and the aggregators to make it possible for libraries to gain immediate and temporary access to e-books at the point of need.

Michael Levine-Clark is the Associate Dean for Scholarly Communication and Collections Services at the University of Denver’s Penrose Library. He is co-editor of the journal Collaborative Librarianship, co-editor of The ALA Glossary of Library and Information Science, 4th edition, and co-editor of the Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, 4th edition. He has been a member or chair of many committees within library organizations, and has served on a variety of national and international publisher and vendor library advisory boards. He writes and speaks regularly on strategies for improving academic library collection development practices, including the use of e-books in academic libraries and the development of demand-driven acquisition (DDA) models. Read his previous blog post: “An academic librarian without a library.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

If you’re interested in library topics, you may also be interested in The Oxford Guide to Library Research. With all of the new developments in information storage and retrieval, researchers today need a clear and comprehensive overview of the full range of their options, both online and offline, for finding the best information quickly. Thomas Mann, Ph.D., a former private investigator, is currently a Reference Librarian in the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress.

Find out more about the book on the

Photograph of Steacie Science and Engineering Library at York University by Raysonho@Open Grid Scheduler. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers