Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1050

June 18, 2012

Can a child with autism recover?

The symptoms of autism occur because of errors, mostly genetic, in final common pathways in the brain. These errors can either gradually become clinically apparent or they can precipitate a regression, often around 18 months of age, where the child loses previously acquired developmental skills.

Can a child harboring such a genetic error ever recover? The answer in each case depends upon a combination of educational and medical factors. Because there are so many different underlying disease entities, each of which has a subgroup of children with autistic features, there are a great variety of clinical patterns seen in autism. There are children who recover spontaneously, children with temporary reversibility of symptoms, children who have major recovery or improvement due to intervention, and children who do not respond to currently available treatments. If possible, it is relevant to identify the underlying disease entity; for example, there is spontaneous recovery seen in the dysmaturational/Tourette autism syndrome. New approaches are revealing the autistic features and underlying diagnosis in younger and younger children. However many children with autism have yet to receive an underlying diagnosis.

Can a child harboring such a genetic error ever recover? The answer in each case depends upon a combination of educational and medical factors. Because there are so many different underlying disease entities, each of which has a subgroup of children with autistic features, there are a great variety of clinical patterns seen in autism. There are children who recover spontaneously, children with temporary reversibility of symptoms, children who have major recovery or improvement due to intervention, and children who do not respond to currently available treatments. If possible, it is relevant to identify the underlying disease entity; for example, there is spontaneous recovery seen in the dysmaturational/Tourette autism syndrome. New approaches are revealing the autistic features and underlying diagnosis in younger and younger children. However many children with autism have yet to receive an underlying diagnosis.

Regarding education, there are several different educational approaches to teaching young children with autistic features. Since autism encompasses so many different genetic errors and disease entities, an instruction program needs to be created for each child individually, taking weaknesses and strengths into consideration. The successful ones share the following features: (1) Starting as young as possible as soon as the autism diagnosis is given and (2) Having a significant amount time spent by the child one-to-one with the teacher. The children need a basic emphasis on learning social and language skills. The majority of individuals with classic autism also suffer from intellectual disability, so many children need additional help with cognitive advancement. To supplement the educational program, control of anxiety and improving the ability to focus are often indicated yet not always achievable.

Regarding medical therapies, attempts to medically treat all individual with autistic features with one drug has generally been a failure. However therapy for some non-core symptoms of autism, such as seizures, can be efficacious. Currently under intensive study with some limited therapies available are sleep disorders, food and gastrointestinal problems, and self-injurious behavior.

There are a few, extremely rare, known etiologies of autistic behavior where established medical/neurosurgical therapies already exist. These include biotinidase deficiency, creatine deficiency syndromes, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, phenylketonuria, and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome.

Thanks to DNA/RNA studies, hope for future treatments is now on the horizon due to the creation of rodent models of the disease entities with autistic subgroups. Although mice are not humans, there is a chance that the effectiveness and possible side-effects of putative therapies in these animals may become relevant. Such models already exist for Angelman syndrome, deletion 22q13.3 syndrome, fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy type 1, neurofibromatosis type 1, PTEN disease entities, Rett syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis. Preliminary reports of therapeutic trials in some of these rodent models are promising and may extend to human clinical trials.

In the end, one of the most important interventional aspects in the field of autism and related disorders is the change of societal attitudes. Acceptance, understanding, and support for these children and adults with autism has been slow in coming, but largely thanks to a number of strong and amazing parents it’s underway.

Mary Coleman MD is Medical Director of the Foundation for Autism Research Inc. She is the author of 130 papers and 11 books, including six on autism. Her latest book is The Autisms, Fourth Edition co-authored with Christopher Gillberg MD. Read her previous blog post “Is there an epidemic of autism?”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Who opposed the War of 1812?

As North America begins to mark the bicentennial of the War of 1812, it is worth taking a brief moment to reflect on those who opposed the war altogether. Reasons for opposing the war were as diverse as justifications for it. Ideology, religious belief, opportunism, apathy, and pragmatism all played roles. Unlike Europeans caught up in the Napoleonic Wars ravaging that continent, the vast majority of free males in North America had — whether by right of law or the by the fact that military service was easy to avoid — choice of whether or not to participate. And, interestingly, most of them chose not to participate.

Like all wars, the War of 1812 is shrouded in myths and legends. One is the myth of American perseverance and bravery celebrated in the US national anthem (based on Francis Scott Key’s poem in the wake of the British naval bombardment of Fort McHenry at Baltimore in 1814). The reality is that the Americans lost most of their battles, and far more often than not they retreated or surrendered after suffering light casualties. At the start of the war, William Hull led a US invasion force into Canada. After meeting moderate resistance, which his force outnumbered, he quickly retreated back to a well-supplied fort at Detroit and then promptly surrendered it, the Michigan Territory, and all American troops and militia in the territory in a matter of days. A furious Thomas Jefferson remarked to President James Madison that “Hull will of course be shot for cowardice and treachery.”

Bombardment of Fort M'Henry. From An illuminated history of North America, from the earliest period to the present time by John Frost, 1856. Source: NYPL.

Another myth is that ordinary Canadians rallied around the British standard to heroically thwart a series of invasions from the US and gave birth to Canadian nationalism in the process. While the invasions were stifled, military historians have long credited this to the poor quality of the US forces and to the superior organization of the small force of British troops defending Canada. While there are numerous recorded actions of Canadian heroism, the truth is that the vast majority of eligible men avoided their legal obligation to serve in the militia. In fact, the Francophone population rioted when the militia was called up in Quebec. The largest turnout of the militia of Upper Canada (now largely Ontario) in the war came following the US capture of what is now Toronto. But they didn’t show up to fight. Instead, they appeared after the brief battle to accept the US Army’s offer of a parole to any militiaman who surrendered. A parole was a legally recognized document by which a combatant was released on his promise not to fight in the war (effectively a pass to sit out the remainder of the war).

The truth is that the War of 1812 was a conflict that few wanted. Not a single member of the Federalist party in Congress voted for a declaration of war. Governors and legislatures of New England states, where the Federalists were strong and anti-war sentiment even stronger, announced statewide days of fasting and prayer in mourning. In a public address sent to Congress in the response to the declaration of war, the Massachusetts House of Representatives declared that: “An offensive war against Great Britain, under the present circumstances of this country, would be in the highest degree, impolitic, unnecessary, and ruinous.” New England clergymen used their pulpits to rail against the war and discourage young men from service, with such ministers as Nathan Beman of Portland describing the army camps as “the head quarters of Satan.”

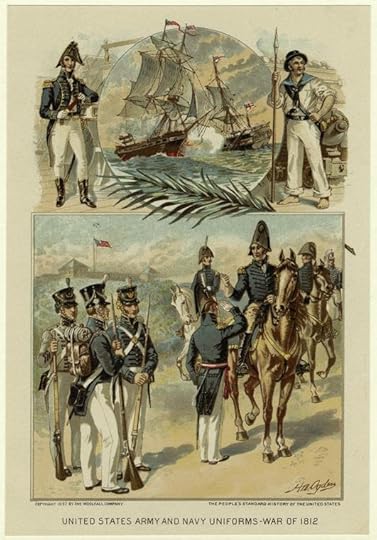

United States army and navy uniforms in the War of 1812 by Henry Alexander Ogden, 1897. Source NYPL.

Even amongst members of Madison’s own Republican party, sentiment regarding the war was lukewarm. Owing to the compromises which proved necessary to secure enough votes in Congress for a war declaration, Madison and the war hawks were unable to pass adequate financing bills to raise, equip, and train a decent army. The result, as historian John Latimer recently summarized, was that “defeat was practically guaranteed from the moment Madison and Congress stepped onto the warpath.” DeWitt Clinton, the popular Republican mayor of New York City and later state governor, ran against Madison in the presidential election that year on a largely anti-war platform. And while the South was predominately Republican, plenty of newspaper editors and politicians spoke out against the war.Few suffered more than the group that defended Alexander Contee Hanson’s right to publish the flamboyantly anti-war Federal Republican paper in Baltimore in June 1812. A heavily-armed group defended the publishing house against a riotous Baltimore crowd that boasted an artillery piece manned by none other than the editor of the rival Sun newspaper. When the affair ended, one of the defenders was dead and eleven more were physically broken following hours of physical torture. These were hardly anti-American radicals. Among the severely wounded was Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee: Revolutionary War hero, former governor of Virginia, and father to the Confederate army general, Robert E. Lee. The dead man was James Lingan, another Revolutionary War veteran and former senior officer of the Maryland State Militia. George Washington’s adopted son, George Washington Parke Custis, gave the funeral oration.

While the war was less divisive amongst the political elites of the British Empire, a number of politicians spoke out against the war. In open debate in the House of Commons, one member called the war “a great evil,” while another lamented that Britain’s mean-spirited “detestation of liberty” and jealousy of post-revolutionary America’s success drove Britain into an unjust war. In Upper Canada, the provincial assembly initially refused to grant the commanding British general emergency powers for fear, at least according to the general, that resisting an American invasion would only agitate the invaders. Some Canadian legislators actually joined the US forces, and then raised and led Canadian troops on the side of the US.

Most North Americans on either side of the Canadian border were far less vocal in their opposition to the war. They simply refused to participate. Despite adding tens of thousands of troops to its paper army each year, the US never met its pre-war recruitment goal of 30,000 men. Desertion was rife in the British Army, which ran short on supplies throughout the hard Canadian winter, just as it was in the US Army, particularly when the bankrupt US government could no longer afford to pay or feed its soldiers in the last year of the war. Often backed by their governors, state militia regularly refused to cross borders, particularly when it meant fighting the enemy on the other side. A furious Madison tried but failed to place them under federal authority. The militia in Canada was not substantially different. Most men refused calls into service and those who did typically deserted by the autumn harvest. In order to persuade the militia in his command to march on the invading Americans in the summer of 1812, the British commander of Upper Canada had to trick the men into thinking they were simply going on an exercise.

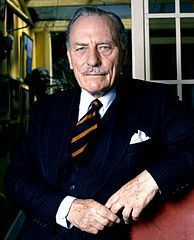

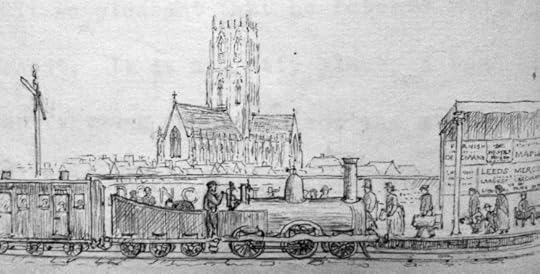

George Cruikshank, “State Physicians Bleeding John Bull to Death!!” In one of innumerable public complaints about high taxes in Britain, this image shows John Bull, the personification of the British people, is being bled, or taxed, to death in order to support the massive military establishment that surrounds him. The British taxpayer proved to be one of the most influential opponents of the war. Fed up with decades of unprecedented levels of taxation, they demanded that Britain’s war machine be dismantled. Fearing a backlash of angry taxpayers if it continued the war, the British government signed a quick status quo antebellum treaty with the US in late 1814 — despite that the fact that Britain had tens of thousands of veteran troops massing in Canada, complete control of the seas, and the US government was bankrupt and unable to pay its dwindling army.

So as guns fire, re-enactors march, and replica ships set sail, remember that what we are recollecting is an important but ultimately just a small slice of the story of the War of 1812. A better representation might be the inhabitants of Nantucket. After public deliberation, a delegation from the island approached the British in the summer of 1814 and signed their own separate peace agreement, whereby the islanders would no longer pay federal taxes or fight in the war and Britain would release any of the island’s men being held prisoner and no longer molest its ships.

Troy Bickham is an Associate Professor of History and a Ray A. Rothrock Fellow in the College of Liberal Arts at Texas A&M University. He is the author of The Weight of Vengeance: The United States, the British Empire, and the War of 1812, Making Headlines: The American Revolution as Seen Through the British Press, and Savages within the Empire: Representations of American Indians in Eighteenth-Century Britain.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Why are we rejecting parents?

Politicians love to say it. Child-welfare professionals work mightily to practice it. American laws and practices promote its essential truth: every boy and girl deserves to live in a permanent, loving family.

Yet tens of thousands of children in the U.S. spend their lives in temporary (i.e. foster) care, unable to return to their original families and without great prospects for being adopted into new ones. At the same time, the number of gays and lesbians becoming adoptive parents increases daily. This reality has raised hopes throughout our country among children’s advocates who see an underutilized supply of prospective mothers and fathers for so-called “waiting children.”

Across the United States, however, some conservative interest groups and politicians have worked in recent years to implement laws and policies that would prevent lesbians and gay men from providing homes for these boys and girls, and a few such efforts have been successful. The good news is that the research on this subject is almost unanimously one-sided–that is, it shows that non-heterosexuals make good parents, and their children do well (see the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute’s report on the subject, “Expanding Resources for Children“). And, in the legal realm, the latest news is positive, too: the Arkansas Supreme Court recently struck a blow for best practices in child welfare by striking down a 2008 referendum–which allowed only married couples to foster or adopt a child from state care–as unconstitutional.

The bad news is that proponents of such measures are continuing to formulate legal and procedural strategies to accomplish their goal. Some of the activists engaged in the gays-shouldn’t-be-parents campaign acknowledge that they believe non-heterosexuals are problematic simply because of who they are. But most maintain, at least publicly, that they are motivated primarily by a desire to do what’s best for the kids who need families.

It is not homophobia, they insist, to establish rules that promote the benefits of parenting by both a mother and a father who are married to each other. They frequently add that preventing gay men and lesbians from adopting protects children from being negatively influenced, or even physically harmed, by the adults who are supposed to protect them.

Such arguments are, at best, ill-informed and, in many cases, plainly disingenuous. If politicians and others who make those assertions truly believe their own words, they should act quickly to remove the millions of supposedly at-risk girls and boys who are already in families in which one or both parents are gay. More urgently, they should swoop children out of single-parent homes, since those families deprive far more children of two married, cohabitating, heterosexual parents than any other cultural phenomenon in history.

Those are silly suggestions, of course, and no one is going to follow them (though there probably are some people who want to).

The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, which I head, is not a gay/lesbian advocacy organization. We conduct independent, nonpartisan research and education projects on a broad range of subjects in order to improve the lives of everyone touched by adoption–especially children–through better laws, policies and practices.

Among the many reports we have published over the last several years are three about gay and lesbian adoption. They contain no shockers; in fact, they simply affirm what previous research has found: that children grow up healthier in loving families than in temporary care, including when the families are headed by qualified (training, vetting and oversight are all parts of the placement process) lesbians or gay men.

That is why a broad range of professional organizations–including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association of Family Physicians, the National Association of Social Workers and the Child Welfare League of America–has come to the same conclusion as we have at the Adoption Institute. These are not fringe groups that would put kids at risk, but just the opposite. The common threads among all of the organizations listed here is that we are in the mainstream and we all work, based on the best available information, for the welfare of children. And we all agree that allowing adoption by qualified gay men and lesbians furthers that objective.

Not incidentally, most adoption practitioners in our country have come to the same conclusion. Indeed, one study by the Adoption Institute showed that a growing majority of agencies nationwide accepts applications from gay and lesbian prospective parents, and at least 40 percent have placed children with them. Again, the social workers, therapists and other professionals at these agencies aren’t in business to hurt boys and girls but to improve their lives. And they’ve decided that that occurs when children stop shuttling between foster homes and are firmly ensconced in permanent ones.

The bottom line is simple: no state can effectively prevent lesbians or gay men from becoming mothers or fathers, because they can do so in other ways–such as surrogacy and insemination–or by moving somewhere that permits them to foster or adopt children. So all a state can accomplish if it imposes restrictions, as Arkansas tried to do and as Utah and Mississippi still do, is to shrink the pool of prospective parents and, as a result, decrease the odds that children in its custody will ever receive the benefits of living in permanent, successful families.

Adam Pertman is Executive Director of the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, a former Pulitzer-nominated journalist, Associate Editor of Adoption Quarterly, and the author of Adoption Nation: How the Adoption Revolution is Transforming Our Families.

A version of this post also appeared on Huffington Post.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Napoleon defeated at the Battle of Waterloo

18 June 1815

Napoleon defeated at the Battle of Waterloo

In a day-long battle near Brussels, Belgium, a coalition of British, Dutch, Belgian, and German forces defeated the French army led by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo led to his second and final fall from power, and ended more than two decades of wars across Europe that had begun with the French Revolution.

Napoleon had been defeated in 1814 and forced to give up his imperial throne. Exiled on the island of Elba, he plotted a return to power that he launched in March 1815 with his escape and return to France.

Reaching Paris and seizing power once more, Napoleon organized a new government and then quickly gathered an army about him. He marched northeast to meet a hastily-assembled coalition against him. With around 100,000 soldiers each, the two forces were nearly equal in size.

Battle of Waterloo 1815 by William Sadler, ~1839. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Napoleon had the advantage of facing armies that were separated from one another, and his forces won initial victories on June 16 against the Duke of Wellington’s British forces and Gebhard von Blücher’s Germans. However, the Prussian rear guard held French forces under Emmanuel de Grouchy in check far from the main battlefield while the rest of the German army conducted a forced march to join Wellington and the other allies there.

That failure — coupled with Napoleon’s decision to delay his attack until midday, to allow the ground to dry after a rain — doomed the French army. During a long afternoon of fighting, Blücher’s troops forced Napoleon to commit more of his army to one side of the battlefield, preventing him from exploiting advances against Wellington’s forces. When the final French attack was mounted, at eight in the evening, it was repulsed by stiff defense. Then the allies counterattacked and the French forces were overwhelmed, leaving the field in a panic.

Napoleon lost 25,000 men (killed and wounded) and had another 9,000 captured. Allied casualties numbered about 23,000. Within days, Napoleon was forced to abdicate once again. This time, he was exiled to far-off St. Helena, where he died nearly six years later.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Maurice Wilkes on Alan Turing

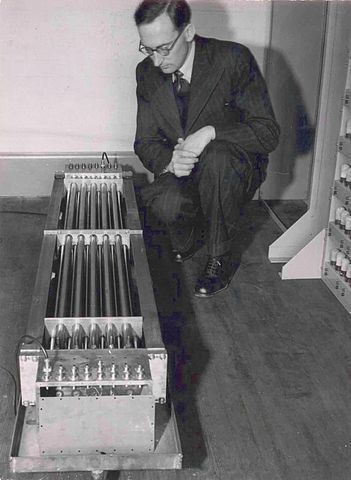

M.V. Wilkes, mercury delay line. Copyright Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge.

It is perhaps inevitable that on the anniversary of Alan Turing’s birth we should wax lyrical about Turing’s great achievements, and the loss to the world following his premature death. Turing was a pioneer of theoretical computing. His ideas are still used to this day in our attempts to understand what we can and cannot compute. His achievements are tremendous in many aspects of mathematics, computing, and the philosophy of Artificial Intelligence. But our digitized world was not created by one man alone. Turing’s work was one of many key pioneers of his era. If only we could listen to the views of a direct contemporary of Turing, we might learn a more complete picture.Perhaps surprisingly then, we are in luck. Sir Maurice Wilkes studied at Cambridge in the same course as Alan Turing, at the same time. Wilkes went on to become an enormously important pioneer in computing: building the first practical stored program computer in the world, and helping to create many designs for computer architecture and programming methods that are still used to this day. Unlike Turing, Wilkes lived 97 years. At an after-dinner speech at his old College in Cambridge in 1997 — 13 years before he died — Wilkes gave his typically honest views about Turing’s contribution. Today these views seem controversial, but they provide a fascinating insight into the history and rivalries within computer science.

Following his dinner Wilkes stood, notes in hand, looking at the dinner guests. He wasted no time, immediately talking about Turing:

“I found him reserved in manner, but the occasional encounters between Alan Turing and myself were entirely cordial. However on a technical level, of course I did not go along with his ideas about computer architecture, and I thought that the programming system that he introduced at Manchester University was bizarre in the extreme. I may have expressed my views rather strongly. Some admirers of Turing thought that perhaps I did not show the proper reverence for the great man. But why should I? We were exact contemporaries. We took the Tripos [a math degree in Cambridge] in the same year and as far as the class list was concerned we achieved exactly the same result. Jack Good [a colleague of Alan] said that Turing was a deep thinker rather than a fast thinker. His IQ was therefore not especially high. That description does I think apply very well to Turing. He was a colourful figure on the English computer scene in the early days of computing immediately after the Second World War. There are differing opinions about what his influence was.

“Turing’s work was of course a great contribution to the world of mathematics, but there is a question of exactly how it is related to the world of computing. There is no reference as far as I know that there might be a real machine as opposed to the one in the paper ["On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem"]. Suppose someone said to you, ‘In order to design an electronic digital computer, we must first explain and illustrate the working of the Turing Machine.’ What would you think? There’s no connection at all. At least to those of us who built them!

“It raises the question of the status of theoretical work in the computing field. One view is that such work is really mathematics – its value is to be judged by mathematical standards. I am inclined to that view. On the other hand it can be, and is maintained by some, that there is a subject called theoretical computer science, which has its own standards and its own criteria. It would have been interesting to have had Turing’s view on this question. He might have been severe on some of the computer science theory that gets published these days, but of course we do not know.

“There are subjects for which there is a mathematical basis, for example Maxwell’s equations provide a real basis for radio engineering. If you were going to design a radio antenna, then you better know something about Maxwell’s theory. The reason why it is a theory is because Maxwell’s equations encapsulate with them very neatly physical laws. They do tell you something about what the world is like. You can’t say that the automata theory [which describes theoretical computing machines such as the Turing Machine, used by theoretical computer scientists] forms the basis for computer science. In fact I myself do not find it helpful to regard it in that light. I would suggest there are two things in this world: automata theory and computer science. These things are level; one is not more important than the other. They exist side by side and there are interesting connections between them.

“Of course Turing also had a great interest in whether machines could think. I was thrilled by the paper he wrote in Mind ["Computing Machinery and Intelligence," which described the Turing Test to measure the intelligence of computers]. I have long felt that Turing, would, if he had lived, have come back to this question and I would have liked to have seen his views. A great deal has been written on Artificial Intelligence. Not all of it is nonsense. It could be that Turing with his prestige, his great insight, and his wit, it is possible that, had he lived, he might have restrained some of the excesses, which you see in that area. But alas he did not.”

Wilkes then sat down, with a quick thank you to his applauding and somewhat amused audience.

Was this speech just sour grapes by Wilkes, who even to this day still has not received the credit he deserved for his own pioneering work? Did it sting to be the second recipient of the prestigious Alan Turing award in 1967 – perhaps he thought a Maurice Wilkes award might be just a little more special? Or did Wilkes have a point?

And how would Alan Turing have responded to this speech, had he heard of it? Perhaps it would be similar to the response he made to the ‘strong comments’ of Wilkes some 50 years earlier, on the subject of Wilkes’ designs for his pioneering computer. Turing said the work was, “much more in the American tradition of solving one’s difficulties with much equipment rather than thought.”

Dr. Peter J. Bentley has been called a creative maverick computer scientist. He is an Honorary Reader at the Department of Computer Science, University College London (UCL), Collaborating Professor at the Korean Advanced Institute for Science and Technology (KAIST), a contributing editor for WIRED UK, a consultant and a freelance writer. He has published approximately 200 scientific papers and is author of Digitized: the science of computers and how it shapes our world, which published this month. Read Peter’s previous post on “Three conversations with computers” or watch an interview with him.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Exploring the Victorian brain, shorthand, and the Empire

In 1945 the British Medical Journal marked the centenary of the birth of Victorian neurologist William Richard Gowers (1845-1915), noting that his name was still a household word among neurologists everywhere and that ‘historical justice’ required that he should be remembered as one of the founders of modern British medicine.

Scott, Eadie, and Lees exploring the Gowers

I (Ann Scott) had just published a biography of my grandfather — Ernest Gowers: Plain Words and Forgotten Deeds (Palgrave, 2009) — when I met Professor Mervyn Eadie in a Brisbane coffee shop. He suggested I might fill the void by writing a ‘prequel’ — a biography of Ernest’s father, William Richard. I had academic qualifications in neither medicine nor medical history, but when Mervyn agreed to join me as a co-author I thought it might be viable. We then approached Professor Andrew Lees who, like Gowers, had spent most of his career at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, to see whether he might be interested in the project. He agreed to join us.

Exploring the Victorian brain

Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System

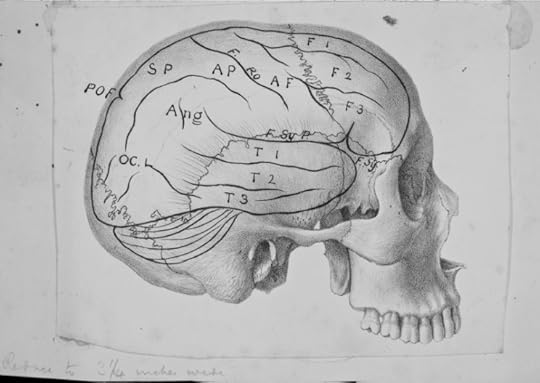

Gowers was a practising neurologist who also researched, wrote, and taught neurology and the working of the human brain. His greatest work was his two volume Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System (Churchill, 1886 & 1888).

Gowers’ own brain was worth exploring. He left a number of diaries and letters which shed new light on his struggle to succeed, his developing social attitudes, and scientific and artistic interests. His early diaries help to explain how he managed his ‘rags to riches’ rise from boot-maker’s son into the Victorian professional class.

During the twenty most productive years of his career he had little time for personal friendships. However, surviving letters written in his later years reveal the warmth of his friendships with men whose intelligence, sense of inquiry, and adventure he admired.

Exploring shorthand?

Gowers' hand-made shorthand bookplate: 'Constant occupation prevents temptation'

One of the secrets of his success was his mastery of Pitman’s shorthand. Long before the days of electronic databases, Gowers collected thousands of detailed case-notes, taken in shorthand at his patients’ bedsides. Gowers was an early convert to applying statistics to medical research. His shorthand case-notes formed his database.

He taught himself shorthand at the age of 15, driven by the hope that it would be useful for lecture notes if he managed to gain a place at University College London. He practised the skill when a medical apprentice in the village of Coggeshall, Essex, by keeping a daily diary in shorthand. Perhaps genetic memory drove me, also at the age of 15, to learn Pitman’s shorthand. Thus it transpired that my first task, just before writing our book, was to transcribe this 80,000-word diary contained in a notebook the size of an iPhone.

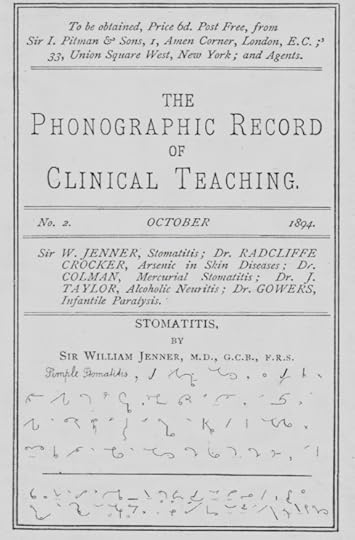

First page of Gowers' 1862 shorthand diary

When Gowers became a medical student he took all his lecture notes in shorthand, and was employed by the eminent physician, Sir William Jenner as his personal secretary. His early interest in shorthand developed into an obsession. When he got engaged, Gowers persuaded his fiancée to learn it so they could conduct their courtship via shorthand postcards. He insisted his four children learn shorthand as soon as they could read, and favoured those of his medical students and housemen who used shorthand. In later life Gowers also initiated and became first President of the Society of Medical Phonographers, dedicating much of his time to promoting medical shorthand. Still driven by this distant Gowers gene, I visited the British Library which houses one of the few surviving sets of the journal Gowers initiated and edited, the Phonographic Journal of Clinical Practice and Medical Science, and compiled a bibliography of all the articles (by Gowers and many others) that appeared in this journal.

Exploring the British Empire

In common with other Victorians, Gowers was fascinated by tales of adventure and the expanding British empire. He became a friend and medical advisor to Rudyard Kipling who, when Gowers was ordered to take a complete rest in 1898, encouraged him to visit South Africa. Gowers took with him his elder son, William Frederick, and ‘lost’ him to Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company, and then to the Colonial Civil Service.

Exploring Gowers

We re-examined Gowers’ original works, many of which have now been digitised, and we also managed to acquire a rare first edition of his Manual. We also trawled through the archives of BMJ, Lancet, and other medical journals to read his articles and also to follow the various assessments of Gowers over time: book reviews, obituaries, and 20th century histories of neurology. This enabled us to compare our own assessments with his achievements as they were perceived at the time, and to see how his theories have stood the test of time.

The family still held a “Children’s Diary” in which, during the 1880s, Gowers recorded and illustrated for his children, descriptions of their holidays in Britain and abroad. Some sketchbooks and other memorabilia included a holiday in Doncaster to visit his wife’s relatives (the Baines family, proprietors of the influential Leeds Mercury), local expeditions, and memories of nationally significant events.

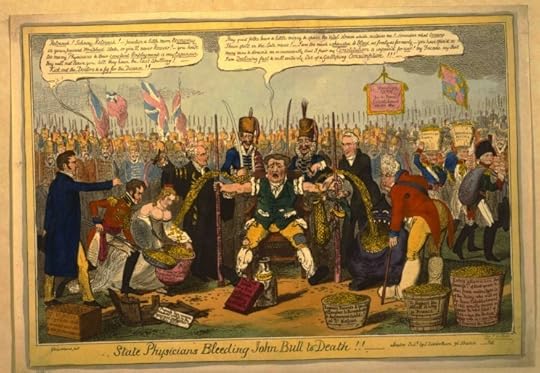

Boarding the train at Doncaster station, July 1885

The museum and archives at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, have only recently rediscovered and catalogued materials formerly held in cupboards outside the hospital wards. The treasures found during this cataloguing included original drawings by Gowers for the first edition of his Manual (1886 & 1888); an album of holiday sketches (one of which had been exhibited in the Royal Academy); two unpublished lectures; and corrections for a third edition of volume 2 of his Manual, also never published. These have been digitized and images will be published online in October 2012 to coincide with the launch of our book.

There were some other surprising finds. Gowers had initiated his friendship with Kipling. He also did so with the Australian adventurer George ‘Peking’ Morrison. Gowers, whose intervention led to Morrison’s appointment as a The Times correspondent in China, wrote many letters to Morrison when the young man was in Peking. Fortunately Morrison was a hoarder, and all the letters he received found their way to the Mitchell Library in Sydney. Through great good fortune we found these letters which, like Gowers’ diaries, give new insights into the attitudes of this pioneering Victorian neurologist.

Ann Scott, Mervyn Eadie, and Andrew Lees are the authors of William Richard Gowers 1845-1915: Exploring the Victorian Brain. Ann Scott is an Adjunct Professor, School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics at the University of Queensland, Australia. Mervyn Eadie is formerly Professor of Clinical Neurology and Neuropharmacology at the University of Queensland, Australia. Andrew Lees is Director of the Reta Lila Weston Institute of Neurological Studies, University College London, and Professor of Neurology at National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 17, 2012

The Beatles at EMI: The Contract, 18 June 1962

Perhaps the most significant unresolved controversy surrounding the recording of the Beatles first single “Love Me Do” rests on the question of whether or not EMI had finalized a contract with them. To wit: on 6 June 1962, were the Beatles auditioning or were they already under contract? Documentation and personal memories conflict such that no single answer can claim to be definitive, even as the evidence suggests a nuanced social interplay between Parlophone’s George Martin and Beatles manager Brian Epstein.

A contract signed by Thomas Humphrey Tilling for EMI and Brian Epstein on behalf of the Beatles suggests that an agreement existed on 4 June, two days before the Beatles arrived for their first session. But George Martin and others have asserted long and steadfastly that they auditioned the Beatles on 6 June, describing the contract date as either backdating or simply a clerical mistake. The question of whether or not this date represented an artist test, a recording test, or the first date of their recording contract rests in murky evidence, including a payment to the band members at the Musicians’ Union rate.

EMI’s Evelyn Harwood had questioned Martin in a 24 May 1962 memo about why the draft contract had not included language about the members of the band receiving Musicians’ Union payments. Martin responded the next day that he intended to pay them at the MU rate, suggested that this arrangement was routine, and that including it in the invoice seemed unnecessary. The payment at MU rates does not rule out the possibility that the Beatles had a recording contract, but session musicians received such fees.

The payment made to each of the Beatles of five pounds and five shillings — the equivalent of five guineas — holds some significance. Guineas represented the preferred form of payment to professionals such as arrangers and music directors, while pounds and pence were what union musicians found in their packets. A fee of £5/5 served as the regulation union fee for a two-hour session in 1962, which describes the amount of time that the Beatles officially spent in studio two. Had the Beatles been there for a standard three-hour recording session, they would have received a payment of £7/10. A two-hour session suggests a test, not a recording session.

Veteran EMI balance engineer, Malcolm Addey (whose career had seen him record some of EMI’s most successful hits to that date) confirms that the session probably constituted a recording test. “The comparison I make to the EMI test is the motion picture industry screen test. They want to know how you sound on mic!” In short, the 6 June session could have functioned as a review to help the production team appraise the strengths and weaknesses of the musicians, their equipment, and their material.

For the Beatles’ first visit to studio, the corporation engaged Norman Smith to serve as balance engineer. Smith hoped to climb the EMI ranks from tape operator to balance engineer and the corporation provided opportunities for on-the-job training by assigning him to such tests. If and when a recording he made proved successful, he would move up the studio food chain. Indicative of a test, Smith recorded the Beatles’ session live, the Beatles playing and singing as though they were on stage, rather than recording the instruments (guitar, bass, and drums) first and then overdubbing (or “superimposing” in EMI speak) the vocal and any other parts. Thus, Norman Smith’s presence on 6 June suggests a recording test, implying a nebulous status for the band: Martin had given the Beatles the opportunity to prove themselves.

A letter from 5 June (the day before the Beatles would arrive in the studio) suggests that George Martin may have already sent a contract signed by Epstein to Evelyn Harwood. The document doesn’t indicate who else has signed the document, but with Harwood in EMI’s Hayes facilities, Martin’s sending the document to her suggests that Tilling (EMI’s representative) had not yet signed. The date of 4 June, then, could well be the day that Martin received the contract from Epstein with the manager’s signature. It does not mean that Martin had signed it. Indeed if Martin had not already signed the contract, then the differences between Brian Epstein’s strategy and that of Martin couldn’t have been more marked. Earlier in the year, Epstein had left the Beatles’ contract with him unsigned as a symbolic gesture. In his mind, an unsigned contract allowed the band the option of dropping him if he failed as a manager. In contrast, an absent signature on the EMI contract suggests that George Martin saw no reason to commit to the Beatles just yet.

On 18 June, Evelyn Harwood returned a copy of the contract to Martin to forward to Epstein. The week between the audition and Martin mailing the contract to Epstein probably involved another layer of decision-making. Technical engineer, Ken Townsend recalls Smith having to send a copy of the 6 June tape to EMI’s Manchester Square offices about a week after the recording date. The likely scenario here would seem that Martin made his fateful decision in advance of one of the regular EMI recording manager staff meetings to consider potential artists on or about 15 June. Even if the other managers thought “The Beatles” might be another of his comedy records, Martin had concluded that they had potential, potential that he needed tweak in the studio if they were to be successful.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Helping children learn to accept defeat gracefully

This Father’s Day, I would like to share some thoughts on an important aspect of children’s emotional development and a source of distress in many father-child relationships — winning and losing at games.

Everyone who plays games with children quickly learns how important it is for them to win. For most children (and, to be honest, for many adults) these games matter. The child doesn’t want to win; s/he needs to win. Winning, by whatever means, evokes in young children a feeling of pride; losing evokes a feeling of failure and shame. It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of these emotions in the lives of our children, especially young boys.

When playing games, many young children take great pleasure in their victory — and in our defeat. To ensure their victory, they may cheat. They may make up their own rules, changing them for their purposes and to their advantage during the course of the game. And they may not be just content with winning. They could engage in some expression of gleeful triumph: boasting, bragging, and taunting. Or, if they lose, they may throw game pieces, insist on a “do-over,” or refuse to play.

When playing games, many young children take great pleasure in their victory — and in our defeat. To ensure their victory, they may cheat. They may make up their own rules, changing them for their purposes and to their advantage during the course of the game. And they may not be just content with winning. They could engage in some expression of gleeful triumph: boasting, bragging, and taunting. Or, if they lose, they may throw game pieces, insist on a “do-over,” or refuse to play.

Why do young children so often need to play with us in this way? Perhaps the answer is simply that this is what young boys are like. For young boys, the feeling of winning — the need to feel a sense of physical or intellectual dominance, to display their strength and skill, to feel strong in relation to other boys and men — seems essential to their self-esteem. Young children need to believe that they can and will do great things.

Developmental psychologist Susan Harter, based on her interviews with preschool children, reports this amusing, but important finding:

“In the very young child, one typically encounters a fantasied self possessing a staggering array of abilities, virtues, and talents. Our preschool subjects, for example, gave fantastic accounts of their running and climbing capabilities, their knowledge of words and numbers, as well as their virtuosity in winning friends and influencing others… fully 50% of them describe themselves as the fastest runner in their peer group.”

Many children who play in this way, both boys and girls, are temperamentally impulsive and strong willed. It has therefore been more difficult for them to learn to control their expressions of frustration and disappointment. For other children, who feel in some way defeated (often by difficulties in learning), winning and boasting offer them temporary relief from feelings of failure and envy. Some younger children have not yet emerged from the age of illusion, the age when children are not yet expected to fully understand the idea of rules. But, to be fair, we all get caught up in the game.

What can we do? How can we help children learn to accept defeat gracefully? Many parents believe that this essential aspect of emotional maturity can be instilled through lectures and strict enforcement. My experience teaches a different lesson. The ability to accept defeat gracefully is not learned from instruction; it is learned through practice and the emulation of admired adults.

In the course of playing a game, there will always be moments of excitement, anxiety, frustration, and disappointment. When you play with your children, play with enthusiasm and express some of your own excitement and disappointment. That way your child will also in some way acknowledge these feelings. These brief moments present an opportunity. You will observe how your child attempts to cope with frustration, and you can talk with him about it.

Most children also seem to benefit from talking about the disappointments and frustrations their heroes endure — baseball players, for example, who sometimes strike out. The goal of these discussions is to help a child learn that his disappointment is a disappointment, not a catastrophe, and that he will not always win or always lose.

We help children with the problem of cheating, with winning and losing, when we help them cope with the anxiety, frustration, and disappointment that are part of every game and everything we do.

Should you let your child win? I have arrived at a simple, although controversial, answer: I let young children win, but not every time. Letting a child win does not teach a lack of respect for authority or encourage a denial of reality. It is an empathic recognition that kids are kids, and being kids, they must learn to accept disappointment and the limitations of their own skills gradually through practice.

Above all, I recommend that parents play frequently and enthusiastically with their children. In these playful, competitive interactions, in innumerable small experiences of victory, followed by defeat, followed by victory, losing becomes tolerable.

It is also important for us to keep in mind that, from the point of view of child development, the philosophy of Vince Lombardi (“Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing”) is profoundly wrong and teaches exactly the wrong lesson.

It is much more than winning that makes competition an important socializing experience. Children should learn the importance of teamwork and cooperation, of commitment to others and respect for our opponents, and especially, learning to play by the rules. Although they may sometimes seem arbitrary to children, rules are there for a reason. We need to demonstrate these reasons to our children.

If winning is everything, children will cheat.

Kenneth Barish is the author of Pride and Joy: A Guide to Understanding Your Child’s Emotions and Solving Family Problems and Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology at Weill Medical College, Cornell University. He is also on the faculty of the Westchester Center for the Study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy and the William Alanson White Institute Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training Program.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

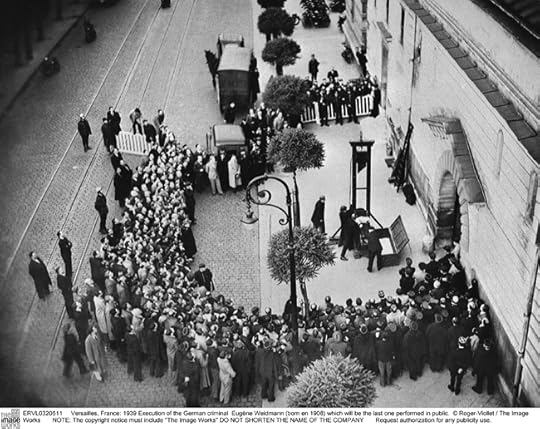

The Last Public Execution in France

Versailles, France: 1939 Execution of the German criminal Eugène Weidmann (born 1908) which will be the last one performed in public. Several hundred additional spectators were apparently gathered behind a second cordon, not visible in this photograph. © Roger-Viollet / The Image Works. Used with permission.

By Paul Friedland

73 years ago today, Eugène Weidmann became the last person to be executed before a crowd of spectators in France, marking the end of a tradition of public punishment that had existed for a thousand years. Weidmann had been convicted of having murdered, among others, a young American socialite whom he had lured to a deserted villa on the outskirts of Paris. Throughout his trial, pictures of the handsome “Teutonic Vampire” had been splashed across the pages of French tabloids, playing upon the fear of all things German in that tense summer of 1939. When it came time for Weidmann to face the guillotine, in the early morning hours of 17 June, several hundred spectators had gathered, eager to watch him die.

Why was this to become the last public execution in France? In the days following Weidmann’s death, the press expressed a growing indignation at the way the crowd had behaved. A report in Paris-Soir, published the day after the execution but seemingly drafted in the heat of the moment, characterized the spectators as a “disgusting” and “unruly” crowd which was “devouring sandwiches” and “jostling, clamoring, whistling.” Before long, the government decreed the end of public executions, expressing its regret that such spectacles, which were intended to have a “moralizing effect” instead seemed to produce “practically the opposite results.” From now on, executions would take place behind closed doors.

The exuberance of the sandwich-eating crowd — however “disgusting” — seems like a rather thin pretext on which to base a radical change in the execution of justice. After all, spectators had been expressing their enthusiasm for, and snacking in the middle of, executions for a very long time. What made this execution different was the fact that it had been delayed beyond the usual twilight hour of dawn and there had been sufficient light for several startlingly clear photographs to be taken. Photographs soon appeared in magazines across the world, including Match and Life. Worse still, from the authorities’ point of view, someone had managed to capture the entire event on film.

But wasn’t the whole point of public executions that people should be able to see them? In theory, yes — or at least in the theory of exemplary deterrence bequeathed to western society by Roman law: that future crimes could be prevented through the spectacular punishment of criminals, striking fear in the hearts of spectators. In practice, however, matters had never been quite so straightforward. Medieval audiences weren’t particularly terrified by executions, tending instead to experience them as quasi-religious ceremonies, singing and praying together with the condemned. Early modern audiences, by contrast, tended to view executions as a form of entertainment. In 1757, for example, hundreds of thousands of spectators massed in the Place de Grève outside the Hôtel de Ville, desperate to watch the would-be regicide Damiens suffer unimaginable punishments over a period of many hours. Very far from being terrified, they showed up with binoculars and a variety of drinks and snacks, the equivalent of today’s movie popcorn. In the coming years, exemplary deterrence would be further complicated by a revolution in sensibilities which took a very dim view of anyone who delighted in the sufferings of others, making the very act of watching executions problematic.

To be clear, these newer sensibilities didn’t oppose capital punishment so much as the spectacle of it. And so began a long period in which government officials and public opinion still subscribed in theory to the notion that public punishment served the goal of exemplary deterrence, while in practice believing that anyone who could actually bring themselves to watch was beyond moral redemption. Writer Jean-Baptiste Suard expressed this paradox: “Unfortunately, it’s not on the wicked people, but rather on the sensitive souls, that the spectacle of punishments leaves the strongest impressions. The man whom one should most fear meeting in the forest, he’s the one who likes attending executions of criminals.”

Not only in France, but throughout the West, exemplary deterrence remained a sacrosanct principle of justice even while contemporary sensibilities essentially forbade the act of watching. From the mid-nineteenth century onward, governments across the globe began to find this situation untenable and made the decision to move executions behind closed doors. Most German states did so in the 1850s, Britain in 1868, and most American states around the turn of the 20th century. France, by contrast, initiated a very long game of hide-and-seek, with officials desperately seeking to limit the visibility of executions on one side, and spectators equally desperate to see them on the other. Guillotines were exiled to the outskirts of town; raised platforms were outlawed in the hopes of limiting spectator visibility; executions were performed with little notice and at the crack of dawn. But still the crowds came — thinner, to be sure, but always present. Only when spectators photographed and filmed the execution of Weidmann, offering the prospect of an infinity of spectators witnessing the event far into the future, did government officials finally acknowledge the futility of trying to make public executions invisible.

And then began a new period in the history of capital punishment, arguably the one in which most countries that still practice it now find themselves. Executions performed behind closed doors are still believed (in some vague and dimly understood way) to serve the goal of exemplary deterrence. If a tree falls in the forest, and no one is around to hear, apparently it does make a sound.

Paul Friedland is an affiliate of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University, and currently a fellow at the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University (2011-2012). He is the author of Seeing Justice Done: The Age of Spectacular Punishment in France, which explores the history of public executions in France from the Middle Ages to the 20th century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 16, 2012

Enoch Powell

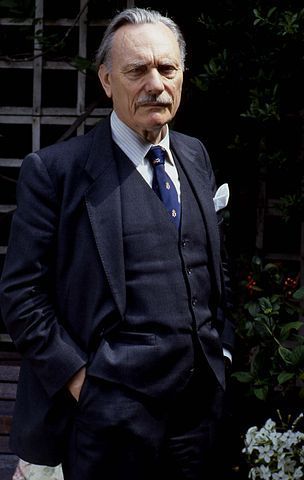

Enoch Powell in his garden, Belgravia, London. Photo by Allan Warren. Creative Commons License.

Enoch Powell was born one hundred years ago on 16 June 1912. His was a provincial, Birmingham family, his parents — both schoolteachers — still retaining a hint of Lloyd George radicalism. The young Enoch, nicknamed by his mother ‘The Professor’, was given to ferocious study. Gradually, as he grew into his teens, the family’s historic radicalism came to be increasingly attenuated as loyalty to King and Empire took on life as a moral absolute. This shift from radicalism to loyalism was not peculiar to the Powells; it signified a deeper political shift in the lived experience of Birmingham itself.However Powell, as we might expect, was not one to do things by half. In the late thirties, in letters to his parents, he expressed the hope that the Tory appeasers would be strung up by the right-thinking body of stalwart Englishmen, for whom reverence for monarchy and Empire was (he believed) simply the natural order of things. In 1939, when war was declared, he relished the prospect of donning the King’s uniform and, so he hoped, dying for the King. To the end of his days, he felt robbed that he had survived the slaughter. As a young man the sole virtue he could see in marriage was that it was a social institution which enabled new generations of soldiers to be born, ready to sacrifice themselves for the Empire.

When in 1947, after decades of popular mobilization, the politicians in Westminster awakened to the fact that the British hold on the Indian subcontinent had come to an end. Independence for India was granted; the enormity of this event induced in Powell a political collapse of the first order. For him, the Empire without India was unthinkable and he had much intellectual work to do in order to imagine how England could be an entity with no Empire to rule. Through the fifties he came to conclude that the Empire had merely been a protracted historical diversion and that the reversion to an England without Empire allowed a new affiliation to the tenets of English nationhood to be re-born. Powell the English nationalist was born.

One can see why Powell is often viewed as a singular, idiosyncratic, even narcissistic figure. Few embarked on the journey he did with the same fervour and power of self-conviction. Yet the extremity of his political evolution should not blind us to the fact that many others, in many different registers, made the same journey. Powell was not alone in having to craft his persona, and his politics, to a new post-imperial reality.

But what is most striking about Powell is that, even as he arrived intellectually at the conviction that Britain’s Empire was no more and eventually came to welcome this fact, he still remained committed to the sensibilities of a hard, proconsular social vision. The system of social difference which he carried into the 1960s had clearly been forged in colonial times. On matters of race and ethnicity, class, gender and sexuality, he continued to inhabit the present as if it were still the colonial past. Through the sixties, those social forces which, as he saw things, amounted to an ‘engine for the destruction of authority’ continued to mesmerize him. And for him, supreme in this respect were the forces of blackness, which through a quirk of historical fortune had come to reside in England itself, undoing the nation and unleashing untold grief amongst its white population.

Enoch Powell, 1987. Photo by Allan Warren. Creative Commons License.

As can be seen from the extent of the mass mobilization of the Powellites in the years between 1968 and 1972, he was not alone in harbouring such sentiments. Thousands upon thousands of white English people believed that Powell spoke for them, daring to say things which other political leaders were too cowardly, or supine, to speak.For all his narcissistic qualities, Powell was not the singular figure who was the mutant, crazed offspring of the society which nurtured him. In many respects, he came to embody its deepest unspoken fears and fantasies. And this explains, in part, the hold that Powell still exerts on English society long after his death. Powell still acts as a touchstone about race and nation. Just when you think that he has finally dispatched, back he comes. Like a traumatic memory he always returns.

Bill Schwarz is the author of The White Man’s World and a contributor to British Cultural Studies: Geography, Nationality, and Identity. He has taught Sociology, Cultural Studies, History, Communications and English. He draws from this varied intellectual background to tell his lively story of the idea of the white man in the British empire. He has been a member of the History Workshop Journal collective for more than twenty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers